Chapter 14: Mortality and Mapuche

Rumiñavi had commanded Tumbez since the Treaty of Cajacamara, living as close to the Spanish as possible. He had managed to survive the initial plagues well enough, staying as a steady face to the Spanish as the population of Tumbez grew while simultaneously plummeting. However Typhus is a cruel disease and the general was no immortal. In April 1542, as the plague ravaged through Tumbez for the second time, Rumiñavi fell ill. It was soon apparent that he would not survive. Word was sent to Cusco as the general spent his last days in bed. In one final act of defiance a priest from San Miguel was barred from even entering Rumiñavi's residence, let alone giving a last minute baptism. On April 10 1542 Rumiñavi died.

This obviously left a bit of a power vacuum in Tumbez, and to a certain extent the empire as a whole. Rumiñavi had been the most trusted and feared of Atahualpa's generals. Rumiñavi's replacement in Tumbez, and thus the de facto ambassador to the Spanish colonists, was Quisquis, who had fought Andagoya along the coast. Well aquatinted with the Spanish, but not with the towering reputation of Rumiñavi. It seems Rumiñavi's death coincided with a sudden upsurge in Spanish raids and treaty violations, though bored conquistadors likely would have stepped up raiding anyway.

The death of Rumiñavi was a grim reminder to Atahualpa of the dangers of ruling and possibly brought succession to the forefront of the Sapa Inka's mind. His succession to the throne had been a Fait Accompli when his main competition dropped dead. Atahualpa's half formed dreams of a Quitan based empire had collapsed with the Spanish arrival and the Machu Pichu rebellion. But he still strived for his sons to succeed him. With that in mind he brought 3 sons south to him[1], in late 1542 and early 1543.

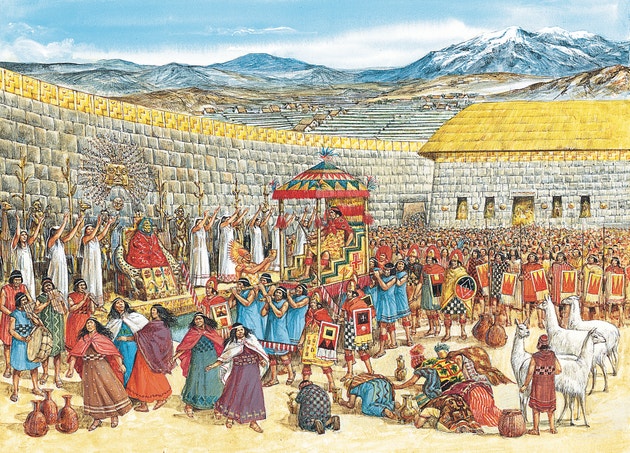

Atahualpa's eldest son Ninancoro was quickly thrust into the world of Cusco when his father entrusted him with the position of Willaq Umu, High Priest of the Sun. Sources differ as to his exact age at the time, but most agree that Ninancoro was no older then 20. This very clearly placed Ninancoro in a position of power, a direct religious link to previous Sapa Inkas. The role also naturally placed him in a position that directly opposed the Spanish, who were becoming more and more aggressive in their missionary efforts following the death of Rumiñavi. Upon his arrival Ninancoro apparently did not make a strong impression in Cusco, simply performing his duties and not seeming to do much that would make him notable to anyone relaying information to the Spanish.

Atahualpa's second son, Illaquita, was by all accounts just a few months younger then Ninancoro and by all accounts a more imposing personality. Illaquita was raised to the office of Inkap Rantin, an immensely powerful position whose holder helped run the empire. This position apparently fit Illaquita's personality well as the young royal quickly gained a reputation for energy that spread even to the ears of the Spanish. It is doubtful that Atahualpa entrusted much in the way of real power to his young son at first, likely seeking only to raise the profile Illaquita to give the prince legitimacy. However in time Illaquita would prove that his energy was not wasted as he proved adept at wrangling the complex relationships between the empire as a whole and individual Suyu. This skill set him apart from his half-brothers and made Illaquita a strong contender to succeed Atahualpa. He proved popular amongst the Northerners his father had brought into Cusco.

Atahualpa putting two of his sons into positions of power without favoring one is somewhat of a puzzle. The arrangement was rife with opportunities for a succession crisis at a time when the empire desperately needed to avoid internal conflict. Perhaps Atahualpa feared that one of his sons would die young, and wanted to have a replacement ready in case of death. Maybe he was simply not sure which of his sons would be best suited to become Sapa Inka and sought to see which one was more capable. It is also possible that Atahualpa has already selected his successor and sought to provide his heir with an experienced partner, after all both the Willaq Umu and the Inkap Rantin were traditionally held by the brothers of the Sapa Inka.

The third son Atahualpa brought south was a fair bit younger then his half-brothers, and so received no special duties from his father. Quispe-Tupac grew into adulthood without any real power. Even when he reached an age when he could be trusted with an influential position he remained frustratingly powerless. Why he was brought south only to be ignored is an oddity, but nonetheless he remained in Cusco. Little is known of what faults or skills he displayed when he was young, but it is known that he began to resent his position. Not so much his father or the empire, but the court and the influence his brothers wielded. Quispe-Tupac sought to heighten his power and remove those who he thought were stopping him from attaining higher status. So Quispe-Tupac began to fall into the orbit of the Cusco nobility, the old powers of the capital that felt shunned by the new, Quitian backed empire. Many of the powerful Cusco elites had backed the Machu Picchu rebellion and had died for it, but in a city as large as Cusco a few could slip the net. Their hatred of Atahualpa's new order neatly aligned with Quispe-Tupac's anger towards his exclusion from power. The Sapa Inka remained in good health, and for all his anger Quispe-Tupac did not hate his father, so no second Macchu Picchu arose. But plots still swirled around Cusco about raising young Quispe-Tupac above his half-brothers.

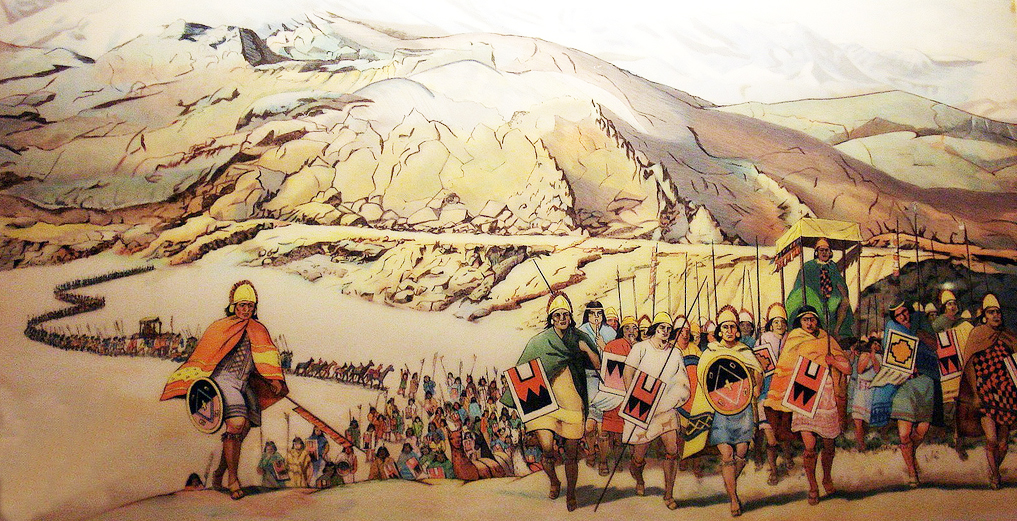

There was a fourth player in the delicate game surrounding Atahualpa's succession. Manco Capac. The half-brother of Atahualpa, Manco Capac was not exactly old himself, having still been a teenager when he rose to prominence. Like Quispe-Tupac Manco Capac had reason to resent the current situation in Cusco. He had been crucial to crushing the Machu Picchu rebellion, but had been rewarded by being sent far away from power. He'd been subordinated to Rumiñavi during the campaign against the Mapuche, a sting to the ego of a member of the royal family. Then he had remained far away from power even after demonstrating himself to be an able leader. To top it all off he saw young boys established into positions that by tradition should of been his. So yes, Manco Capac had reason to be a bit grumpy. Unlike Quispe-Tupac he could not turn to other dissatisfied groups in the empire, Cusco hated him following his betrayal of Agua Panti. But Manco Capac did have one huge advantage, he had tremendous influence across the south. He had run the Qullasuyu for several years prior to Rumiñavi's death and had a significant following across the province. So he waited in the South, a force into himself waiting to be moved.

The Spanish, of course, were very intrigued by all of this. As the years passed following Athualpa's sons arrival the Spanish grew bolder in their raiding. They took full advantage of what would prove to be the nadir of the epidemics in the heart of the empire. Unofficial missions cropped up around San Miguel and the way stations along La Carretera blossomed from desolate outposts to small but busy centers of trade. Tawantinsuyu parties bearing silver to pay for Spanish goods were often robbed, effectively forcing the empire to pay double what was owed. Tawantinsuyu Iron remained shoddy at its absolute best, so the Spanish controlled their rival's supply of that valuable metal. For gunpowder and new guns the Tawantinsuyu remained completely dependent on Spanish goods. Obtaining small amounts was easy, any colonial Spaniard had then and was easily persuaded to sell them for some silver, but the larger amounts needed to truly support a large army were still tightly controlled from San Miguel. The Spanish also began to nose around the internal affairs of the Empire, looking for possible allies against Atahualpa. They found some friends on the coast, particularly near Tumbez where ties to Spain were very high. Spanish ships that pressed to the far south told tales of the Mapuche, clinging to life to the south of the Empire. They were too far away to be of any help to the Spanish now, but were still useful to know about in the future. Far more immediately interesting to Spaniards interested in

reevaluating[2] the Treaty of Cajacamara were the previously mentioned Cusco nobles, eager to rid themselves of the hated Quitians. The Spanish informally began to snoop around, especially after they learned of the Macchu Picchu rebellion. They found a notable divide. Some Cuscans would have been glad to let the Spanish march into Cusco, depose Atahualpa and take the troublesome north off of their hands for good. But not all were so naive, most still rightly feared the Spanish. The latter group was not entirely useless to the Spanish however, their distrust of Spain extended to new weapons and they favored "the traditional ways of war". The Spanish in San Miguel never made any sort of arrangement with the internal enemies of Atahualpa, but enterprising individuals who wished to do what none before had watched the factions in Cusco with great interest.

Atahualpa's response to the aggression of Spain was aggression of his own. Spaniards who wandered off La Carretera without enough numbers found themselves pressed into the service in increasingly large numbers. Missionaries were generally left alone, so long as they remained in their place, but starting around 1545 native converts were often treated ruthlessly. Forced reconversions to sun worship were quite common, complaints from the Spanish were ignored. The chaos of plague had allowed trade with the Spanish to crop up that was not conducted by the central government, this trade still persisted along the coast but along La Carretera the Tawantinsuyu sought to stop it altogether, to varying degrees of success. This response increased tension between the Spanish and the Tawantinsuyu, and the two powers began to harass each other more and more.

Contact with the Spanish proved fruitful to the Mapuche

As the Spanish in San Miguel grappled with the Tawantinsuyu the Spanish on the Rio de la Plata grappled with the enemies of the Tawantinsuyu[3].

The City of Asunción was not even a year old when in 1538 its inhabitants first encountered the Mapuche who had fled across the desert fleeing the Tawantinsuyu conquest. First contact went very poorly. The Spanish demanded to know where the Mapuche had gotten the few horses they had, and then upon learning that the Mapuche came from a place far to the west demanded guides to this far off land. The Mapuche were of course suspicious of the strangers who bore similar weapons to those who had forced them from their homes and declined to make another deadly journey across the desert. Things escalated quickly and skirmishes broke out. The Spanish were better armed, better trained and (barely) in better health. The Mapuche were forced onwards. As they trekked deeper into the Pampas however, they found their position improved. European diseases had decimated them, but so to did they decimate local tribes. The few horses they had proved advantageous when stealing food from locals. And as they grew nearer to the sea a stroke of luck arrived.

The "Ciudad de Nuestra Señora Santa María del Buen Ayre" or simply "Buen Ayre" was the first Spanish colony on the Rio de la Plata, but was in tough waters. It had been established by Pedro de Mendoza in 1536 and had faced disease and hostile natives from the get go. Mendoza had become sick from syphilis and had returned to Spain in 1537 and despite his pleas the mother country had not been forth coming with aid. Many colonists had moved upriver to the safer settlement at Ansunción. Despite not even being 5 years old the colony seemed to be on a very short road to the dustbin of history. But fate had other ideas. As the Mapuche barreled down the the Rio de la Plata they fed themselves largely by raiding the food supplies of the locals or trading. The former option was employed when the Mapuche encountered the Querandí. The Querandí just so happened to be the group that was violently opposing the Spanish colony at Buen Ayre. The Querandí took offense at the raiding and skirmishes commenced. On November 28th 1538 a group of Mapuche raiders struck a band of Querandí in the rear while the Querandí were busy fighting another group. This group turned out to be Spanish.

This situation quickly proved awkward for the Mapuche, as the Spanish of Buen Ayre did not realize that they had fought the Spanish of Asunción. Nonetheless a tentative bond was form. Unlike Asunción Buen Ayre did not immediately demand explanations or wealth, being too focused if survival. Crucially once a vague understanding of the Mapuche was reached the Spanish realized that the Mapuche had not stolen them from Spaniards, easing any tensions. Reasonable trade was set up, though neither side had much to trade. This tentative relationships was bolstered when the Mapuche continued raiding the Querandí, and then started driving the Querandí out of the area altogether. Spanish weapons and Mapuche numbers and experience proved decisive in what proved to be the end of an independent Querandí culture. Still small and weakened the Spanish could do little when the Mapuche decided that this land was as good as any and settled down. Mapuches intermarried with surviving locals and established villages like the ones they remembered across the desert. Trade with the Spanish increased, as the vague Mapuche confederation became the colonists only ally in the region. Spanish expertise enabled the Mapuche to breed their horses into larger herds. The Mapuche proved better hunters then the Spanish, disease ridden though they were, and they soon began to pick up local farming techniques. Some even converted to Christianity. The Buen Ayre colony managed to smooth over difficulties with the Asunción colony over the earlier fighting. Word spread across the Atlantic that Buen Ayre was as safe as a colony could be. This was a complete fabrication, but Buen Ayre did indeed enjoy a massive turnaround in fortune and population. The political situation in the Rio de la Plata region shifted, by 1545 Mapuche influence was spreading and several smaller settlements had emerged surrounding Buen Ayre. But as they settled into the region they remained unsettled. Conversions were happening, but not at a fast enough rate for the liking of the Spanish. And the Spanish control was loose, and often dependent of Mapuche assistance. No Gold was being found, and no further progress was being made towards the fabled lands of the Tawantinsuyu from the south. So the equilibrium reached in the mid-1540s Rio de la Plata would break, it was just a matter of when.

To a purely cursory observer the situation for the Tawantinsuyu had not changed much from the Treaty of Cajacamara to 1545. But a closer examination revealed a different picture. Atahualpa bringing three of his sons south had dramatically altered the political situation in his empire. In addition the Spanish had improved their position. The Spanish empire was better informed on the workings of the Tawantinsuyu, had acquired more possible allies then before, and now possessed a foothold on the empire's southeastern end that the Sapa Inka knew nothing about.

_____

1: Atahualpa's sons have been my mortal enemies in writing this chapter. John Hemming's

The Conquest of the Incas has a family tree appendix that lists sons, all of whom have Spanish names, and some of whom lack native names. This certainly suggests that they were young children when they entered Spanish custody. But for the life of me I cannot find any other sources on the sons of our favorite emperor. Therefore I'm essentially taking the names and running with them, despite having no real knowledge of the sons. Any sources would be welcomed.

2: Wink Wink, Nudge Nudge, Say No More, etc etc.

3: I completely, utterly, entirely fucked up the dates of the Spanish colonization of the Rio de la Plata. When I wrote about the Mapuche entering the Pampas I forgot about how the Spanish had already arrived. But I think that the maps should still be accurate.