Chapter 3: A Long and Winding Road

The Andes Mountains proved a large asset to the Tawantinsuyu

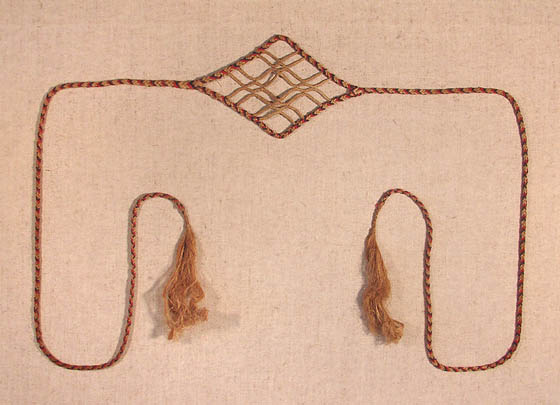

The Tawantinsuyu Road system was, in 1532, arguably the best that the world had seen since Rome had fallen into chaos. It stretched from the northern mountains to the souther desert. Storehouses were set up and runners staggered to ensure the fasted possible communications. Rope bridges of dizzying hight helped keep the Empire together. With no written language messages were either oral or on Quipu[1]. Watchtowers dotted the highways and each community donated portions of food and time to give runners good rest. With no wheels for commercial use all travel was done by foot, or liter for the powerful of the Tawantinsuyu Empire. The only other thing that crossed the roads were long trains of Llamas carrying goods or being traded.

This road system was good moving moving Tawantinsuyu troops about with ease and rapid responses. However the roads made it easy for the Spanish to travel along the coast with greater ease then the invaders had expected. But it was different now that they headed inland.

The Chancay is hardly even a river, more of a stream, but it flows from the mighty Andes down into the Pacific. A small road ran up its course into the steep hills, going through the town of Chongoyape. From there it turned onto the treeless alpine tundra. Forts dotted the landscape on the way to Cajamarca and narrow passes were often threaded by the road.

It was into this type of desolate country, the land where the Tawantinsuyu had originated, that Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish marched starting on December 2nd, when they departed Saña for their "meeting" with Atahualpa, bearing the imprisoned Rumiñavi. In doing so they unknowingly surrendered themselves to the Inka's will. At Saña the Spanish had possessed the advantages of being well positioned to exploit their advantages (such as their position being well suited for a calvary attack), surprise, and their weapons and horses striking fear into the unprepared army[2]. However the desolate passes were a completely different game.

The road system had been built for three things, people walking, people running and llamas. So the roads were more then paths but were not designed with ease of transport in mind. A human is relatively versatile on steep roads with many switchbacks and the llamas were bred for mountain living.

Horses were not.

On the smallest Tawantinsuyu roads, of which the one following the Chancay Stream was, the steep and narrow route made riding the horses dangerous enough that most Spanish chose to lead the horses along rather then ride. Fighting on the horses was out of the question, the horses could simply not get the traction needed to charge effectively. And so immediately one of the major advantages of Pizarro was defeated by nature. The narrow roads also forced the Spanish to march single file up the road, keeping their effectiveness further limited.

The roads were bad enough, but off the roads even foot-soldiers were useless to Pizarro. The terrain was rough and they had no experience with such land. They didn't know the area or where the cliffs were. But the locals did, and the Tawantinsuyu did.

For all their claims about the "subhuman" natives across the Americas the Spanish faced a very real biological fact entering the Andes. The Tawantinsuyu had lived in the mountains for centuries. Simple facts of Unequal Inheritance[3] caused them to have stronger lungs to breath the thin Mountain air. The Spanish did not have this and many soon came down with weakness likely resulting from this.

In summation the road leading towards Cajamarca singlehandedly annulled the advantages the Spanish had for almost everything[4].

Atahualpa did not know all of this at the time, he only had fragmented and panicked reports of their power. But he knew the land well and knew the Chancy road provided a good opportunity for an ambush and began to plan accordingly. He dispersed parts of his army, swelled with numbers from Rumiñavi's force, into the mountains. Watchtowers who spied the Spanish sent off runners like clock work. Locals the forcibly kept silent. At the end of the stream, where the road turns into the alpine tundra, Chalcuchima sat. Officially awaiting to escort the Spanish but in reality serving as a last line of defense. It is almost certain that some Spaniards expected an ambush, but most expected it to occur in the presence of the Emperor. Those who did fear an attack in the mountains still felt good about their odds.

The exact location of the Battle of Chancay Road is still unknown, as it was not near any specific town. But there are a few first hand accounts that serve as a guide and the date is recognized as December 9th. The ambush likely started with a massive army appearing on a high hillside into the view of the the Spanish. They did not realize the scale of the attack until the first volley of stones hit them. At the time the crossbows were few in number and the guns inaccurate and time consuming. This made the simple stone sling the most efficient projectile weapon in the Andes. A good Tawantinsuyu solider could strike with deadly accuracy with one. The stone volley killed a few Spanish but mostly sowed confusion amongst them. The Spaniards faced the problem of aiming up steep cliffs towards small targets with their bows and guns, a nearly impossible task. So they attempted to leave the road. Their horses became even more useless off road and the terrain was hard to traverse for inexperienced travelers. Soon Tawantinsuyu warriors were streaming out of the hills. The Spanish still had one crucial advantage however: Steel. Their swords were far, far better then anything then Tawantinsuyu possessed and the armor was effective against the clubs and bronze weapons. But the numbers were against the Spanish and the hills meant they were attacking the Tawantinsuyu up steep hills, and there was only a certain number of hits a Spanish man could take before an enemy solider got lucky. Stones continued to fly down on the the Spanish group, scattering attempts to organize as one hit to the face could kill a man.

All hope of a Spanish victory was lost when a small group of Tawantinsuyu freed the tied up Rumiñavi and brought him back to their lines. The Tawantinsuyu now had a general and a huge physiological victory over the Spanish. Soon the Spanish became bottled on the road, with enemy soldiers on both sides and quickly became surrounded. Pizarro was prepared to fight to the death, which he did, but after he bled out after a lucky cut from an axe the Spaniards fell apart. Those who kept fighting were isolated and killed while many others surrendered.

An unintentional side effect of the Tawantinsuyu's less advanced weapons was a relatively low casualty rate for the Spanish, some 84 men survived the massacre, and were to be brought before Atahualpa.

Some were determined to die for their faith and nation and would not yield to a "barbarian" king. But others lacked that conviction. And so the knowledge the Spaniards held began to leech into the New World.

+++

1: The Knot Things

2: And an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope

3: Evolution

4: IOTL Pizarro wrote "We were very lucky they did not set upon us" while passing the region.