The Council of the Indies had spent years trying to organize the conquests of Spain into a proper hierarchy under the ultimate authority of the King. In this they were united in purpose with Charles. Cortes had been put on a leash in Mexico, Governors and Real Audiencias had been established to ensure Spanish law was firmly in place across the Atlantic. So upon receiving Mendoza's reports of Belalcázar backstabbing fellow Spaniards in favor of unruly natives they were very much inclined to side with Mendoza's position and declare Belalcázar an outlaw. Nonetheless they recognized the unique circumstances surrounding San Miguel and referred the matter to Charles.

By now in was March of 1547, at it was apparent to Charles that his finances were in dire straits. The mines of Mexico could not keep up with the demands of German warfare. As he consulted his generals regarding his strategies in Swabia and Bohemia he received word of Belalcázar's reported treasons, along with the verdict of the council. The council was of the opinion that a more efficient and loyal Governor of Nuevo Oaxaca would increase the revenue coming from the small outpost, even assuming that no further conquests were made. Charles was in agreement. But it was not just money that motivated. He was in the middle of a war that had Catholicism at its center. Charles was perhaps not always the perfect Christian, but Belalcázar's failure to adequately protect and expand the one true faith did not endear him to his King.

So the King agreed with the Council's conclusion, and formally concluded the matter by declaring Belalcázar deposed. He ruled that Carvajal did have rights to some form of compensation, though Carvajal would die before hearing of his good fortune. To replace Belalcázar Charles selected Cristóbal Vaca de Castro, a 55 year old veteran of the Iberian Audiencia system as Governor of Nuevo Oaxaca. Castro was also given the title of "juez pesquisidor", special investigator, giving him the authority to resolve claims until a proper Real Audiencia could be established.

The war prevented any troops from being provided immediately to Castro, however he given was authority over certain vessels in Panama to secure his passage to San Miguel. In addition he was given a latter to Atahualpa explaining the situation and demanding that all trade with Belalcázar cease. And so Castro set out, unknowingly changing the course of history.

Castro's time in Mexico was brief, meeting with Mendoza and learning the Carvajal was dead. Like Carvajal Castro found recruiting any sort of force in Mexico difficult. The King's seal opened a few doors, but most in the valley had already found themselves a plump Hacienda and were suspicious of royal authority. Castro found better luck as he went south, by chance his ship landed in the Yucatan and there he found quite a few able soldiers. The ancient cities of the Maya remained difficult to conquer, and many there believed that they would have better fortunes abroad. Castro took a slow route down the coast of Central America, picking up prospective allies along the way. By the time he reached Panama he had assembled a reasonably sized forced of veterans of Central American conquests, a trade that often involved fighting fellow Spaniards.

Like Carvajal before him Castro found his reception in Panama to be chilly. The Audiencia remained throughly tied to trade with San Miguel and news that Castro was establishing a new Audiencia that would limit their power was unappealing to them to say the least. That said he was a royally appointed Governor with a large force on hand, so funny business was avoided in general. Castro found little in the way of new soldiers in Panama, but he did find a fleet. His royal authority permitted him a few ships already, and some liberal application of gold and implications that as Governor he would allow stops other then San Miguel won him more. By the time he departed Panama Castro had assembled around 1,500 infantry men and 650 calvary, mainly from the Yucatan and Central America. Combined with the small fleet he assembled it was the largest force to sail to the Tawntinsuyu ever assembled.

By this point Belalcázar was aware of the incoming force and began fortifying San Miguel once again. This aroused further suspicion from Quisquis, who began demanding to know what was happening. Belalcázar became increasingly hostile and refused to grant audience to any messenger from Tumbez. He was hunkering down for a fight.

Castro sailed right by San Miguel when he arrived in September 1547, cutting straight towards Tumbez. He received a poor first impression of the Tawantinsuyu when he attempted to land and found his force attacked with cross-bow bolts. Once he had sorted out that he was there under a flag of truce Castro approached Quisquis with his credentials and demanded assistance in removing Belalcázar. Quisquis was suspicious, Castro was sounding suspiciously like Carvajal, and would not allow the Spaniard to enter Tumbez. Quisquis told Castro that he would need to consult with Belalcázar and Atahualpa. Castro demanded to see the Sapa Inka personally to present his case. Quisquis refused, sending messengers to Cusco for orders. Meanwhile the general was being bombarded with messages from Belalcázar declaring that Castro was lying and that it would be better to kill him right now. Quisquis held firm and awaited orders.

Atahualpa received the word of Castro's arrival with concern and hope. The Sapa Inka gravely feared the idea of another war with the Spanish, the Tawantinsuyu had not yet garnered the power of steel or gunpowder and the Spanish now knew far more about his empire then they had previously. On the other hand Atahualpa believed that having the Spanish governor in his debt would be greatly advantageous, and hearing of the forces Castro possessed made him more inclined to face Belalcázar in battle. Atahualpa sent his judgement, Quisquis was to escort Castro to San Miguel and gain him entrance to the city. The Tawantinsuyu had agreed to let Spanish law reign in San Miguel, so they could not just disregard Castro, but Atahualpa also refused to attack the city. Quisquis would get Castro to San Miguel but no further. Atahualpa thought he had found the perfect plan. The Spanish would fight, and the Tawantinsuyu would win, having not entered the fight.

By 1547 he had much grayer hair. Don't tell him that.

But the Sapa Inka had miscalculated, many Spaniards in San Miguel were tired of Belalcázar's failure to conquer more land. The church in the town condemned Belalcázar's failure to convert more souls. Many more simply did not want to lose their lives so that the old man could keep his fortune. So when word arrived in San Miguel that Cristóbal Vaca de Castro was marching on San Miguel many panicked. A group of conquistadores turned merchants attempted to sabotage to the defenses of San Miguel on October 17. Belalcázar rode out in an attempt to stop then. In the ensuing scuffle Belalcázar, not as agile as he once was, took a sword in the side and bled out on the spot. The old conquistador was dead aged 67, after a life that had earned a sterling place in history. Though he died in rebellion against the Crown of Spain, later generations would lionize him as a hero of the colonization and exploration of the Americas.

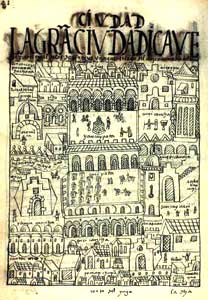

The death of the governor threw San Miguel into chaos, suddenly the prospect of Castro taking power and placing a firm hand on the reins seemed more appealing. By the time that Castro arrived in San Miguel, 12 hours after Belalcázar's death the murderers of Belalcázar had already been killed, but they were not the only ones sympathetic to Castro. A few former acquaintances of Carvajal allied with more disgruntled merchants to seize the town through violence and bribery. With the town still in shock from the murders opposition was nonexistent. Castro found a San Miguel that, while not united in his favor, allowed him to take command as Governor without further fighting. Known allies of Belalcázar were placed in custody and their property seized by the Crown. Castro delayed forming a Real Audiencia until the "situation could be calmed". Castro immediately ordered that all natives in San Miguel convert, leave the town or be branded as spies. He then turned towards the issue of compensation.

Every free man in San Miguel suddenly had a complaint about the "villainous" government of Belalcázar, and many of these complaints featured requests for compensation. Castro was now in a bind, distributing generous compensation to various citizens in San Miguel would help shore up support for any future actions that might prove controversial. That said one of Castro's primary goals was improving the revenue stream coming in from San Miguel and Castro did not want to cut into the pile of treasure. So he produced the famous "Bill of San Miguel", a list of the debts owed in the town. Anyone with a just complaint about arrests or seizures would be payed by the crown or the offender, however in any incidents that had occurred outside of San Miguel the debtor was listed as the Tawantinsuyu. Castro, hoping to skim a little off the top for both himself and the crown, set the price extremely high. Both Quipu and Spanish records show that Castro claimed that the Tawntinsuyu owed Spain some 200,000 pesos, just under a third of the total number of pesos produced by Mexico in a year. It was an incomprehensibly ridiculous total. Indeed Quisquis did not at first comprehend it.

The amount was so large that when the message asking for the gold and silver was received Quisquis assumed that the Spanish were asking him what the Tawantinsuyu would want in exchange for 200,000 pesos. He sent what he assumed to be a reasonable reply, saying that while such a large payment required the Sapa Inka's approval he thought that large numbers of guns, horses and steel would likely be what the empire needed. This response infuriated Castro, who sent a reply clarifying that this was a demand for gold not a purchase. Quisquis was appalled and sent word to Atahualpa about the thoroughly outrageous demand as well as requesting reinforcements should the Spanish get too aggressive. Atahualpa sent a request for Castro's reasoning and received a long list of grievances ranging from relatively reasonable (the Tawantinsuyu had indeed made Spaniards serve them against their will) to dubious (many areas of the empire were not welcoming to Christians, but the central government had never tried to purge them) to ludicrous (Atahualpa had never ripped out a mans heart and impaled it on a cross). Castro also demanded to meet with Atahualpa to "discus" the Treaty of Cajacamara.

Cusco was at the center of debates over what to do.

All of this was very concerning to Atahualpa and he faced conflicting advice from within his court. No one thought handing over a lump of gold was a good idea, but they differed on how to approach the issue. His generals favored refusing the offer out of hand and burning San Miguel should they fail to back down. The Quitians saw this as an opportunity to take revenge for Alavrado's pillaging during his invasion as well as a chance to take more power after saving the empire once again. The nobles of Cusco saw it differently. War would only bring influence to their enemies the Quitians. In addition Spanish trade ran close to Cusco, and occasionally into it. All profit went to the Sapa Inka, but the trade brought a focus and importance that Cusco felt had been waning in the years of rule from Quito. They urged negotiations, perhaps a smaller sum over a longer period of time. A small faction of Southerners had also sprung up at court, mainly to inform Manco Capac of what was happening. The Southerners mainly just reminded Atahualpa that the Iron mines in Qullasuyu needed protecting.

Illaquita sided with the Quitans, though he urged his father to send a formal declaration of war to Charles V before invading. He also opposed destroying San Miguel, Illaquita saw it as a valuable resource for modernization. Illaquita hoped for a quick war that would end for better terms for the Tawantinsuyu. Ninancoro sided with his younger brother, though had nothing unique to say on the matter. Quispe-Tupac meanwhile sided with the Cuscans, arguing that there was no need to disturb the current equilibrium. Atahualpa weighed the issue carefully, but ultimately proved predictable and sided with the Quitians. Atahualpa gathered an army in Cajacamara before sending his reply. It was a definitive no, though it reiterated Quisquis's offer to purchase large amounts of material. Castro replied with a harsher demand for the money, and again Atahualpa refused. He left Cusco and summoned any army to meet him at Cajacamara. Manco's concerned reports led to most of this army coming south from the Northern frontier, leaving an opening for various tribes to try and regain lost land.

News filtered down to Castro of Atahualpa's movements and he responded by violently repelling any Tawantinsuyu who attempted to enter San Miguel. A few fought back, and Castro openly began organizing a march on Tumbez. On November 24th he sent a letter to Charles V explaining his reasoning for attacking, claiming that pagan had rendered the Treaty of Cajacamara null and void. In the absence of any final message to Atahualpa his letter is considered to be the beginning of the 1st Hispano-Tawantinsuyu War[1].

_____

1: ITTL historians will note that the earlier conflicts were privately funded conquest efforts that by and large had no idea what they were getting into. Hence they are given the name "Southern Expeditions."