A prayer before entering enemy territory

Soon after dispatching his letter to Charles V Castro led his assembled men out of San Miguel. It was a bold move, it left the town with barely a skeleton force of defenders. But it did bring his manpower up to over 1,000, the largest such army ever brought forth against the Tawantinsuyu. Castro led no army of soldiers of the Crown, but they were experienced fighters. Many had fought in the long, grinding war in the Yucatan and knew just how dangerous "savages" could be. They were joined by a small collection of translators and Christian converts who had remained San Miguel rather then return to the Tawantinsuyu. Their goal was the same as every Spaniard since Pizzaro, the city has been a moderately sized one before contact but Spain's unwavering obsession with it had ballooned its importance. The Tawantinsuyu could boast natural defenses in the Andes, but the fortress that Tumbez had become was made only by man. Besting it would be a major victory for Castro. He easily swept aside a force sent to intercept him along the road to Tumbez and soon found himself standing before Tumbez. Quisquis had evacuated himself south by this point, leaving the defense of the city to his soldiers. These soldiers were among the most familiar with Spanish fighting but they also happened to be the most familiar with European diseases. This created a general lack of cohesion and meant that while many soldiers were experienced most weren't able to pass on said knowledge before falling ill. While the preparation for war was the highest in the empire it had also stagnated due to plagues, at the moment it was a sweep of Tuberculosis, in contrast to the smallpox that was ravaging the valley of Cusco concurrently.

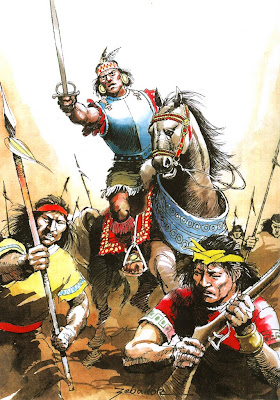

The 7th Battle of Tumbez[1] was divided into three parts. The first and longest was the assault on the city walls. Castro had been anticipating a fight with Spaniards to take San Miguel and so had dragged along fairly decent cannon. So he quickly began to attack the walls backed by a skilled bombardment. The Tawantinsuyu did have some powder, as well as their usual crossbows, but proved less efficient then the Spanish. Tumbez had relied on purchases from the Spanish to stock gunpowder, and now saw that supply be plugged. Normally their stockpiles would have supplied them until some could be procured, but improper storage combined with heavy rain just before the battle left their stores severely dwindled. So while the first day of attacks failed to pierce Tumbez on December 7th they found more success. The Spanish fought their way into the city with a combination of wall scaling and bombardment. They managed to enter the city with minimal casualties, specifically to their crucial calvary. Their entrance into the city marked the second part of the battle, the street fight. This in turn was divided into two parts. The first was a bloody fight to expel the Tawantinsuyu forces from the city. Here the better understanding of horses gave the Spanish an advantage, their greater control enabling them to out fight their opponents. The street fighting was the bloodiest part of the battle for the Spanish, though their casualties remained low. The Tawantinsuyu faced higher rates of death in the battle, all while a wholesale slaughter of Tumbez was getting underway. Anything "Pagan" was attacked and for the most part everything that was attacked was destroyed. Civilians were killed and raped in large numbers, despite the occasional halfhearted requests by Castro to "exemplify Christian virtues". The slaughter finally ended when the Spanish exited the city to the south. A segment of Tawantinsuyu soldiers had fled the city and were now trying to organize either a counterattack or an orderly retreat. Neither option was preferable to the Spanish, so Castro ordered his men to pour out of the city. The still disorganized Tawantinsuyu never stood a chance and were scattered quickly. Retreat turned to rout and soon the entire army of Tumbez was running south to rendezvous with Quisquis.

The defeat at Tumbez was a blow to the Tawantinsuyu cause, but not an unexpected one. Tumbez had fallen to Pizzaro, Almagro, Andagoya and Belalcázar. The defeat was not the end all be all of the fight. Quisquis found his army battered, and so rather then opposing Castro immediately he retreated towards Saña. Under previous circumstances this was intelligent move. Previous attempts at conquest has featured the Spanish going straight for the Tawantinsuyu army, and if pressed Quisquis could have retreated into the easily defensible mountains. But Castro was not headed for Saña just yet. Instead he kept heading south, making a beeline to Chan Chan, the old capital city of the Chimu Empire before the Tawantinsuyu conquered it in 1470. Castro had an advantage no other Spaniard had possessed before him, knowledge of the various groups in the empire, mainly from Spanish captains. Castro had heard (correctly) that Chan Chan still held great wealth but wasn't defended by the mountains. In addition he knew from Spanish sailors that, despite the best efforts of the Tawantinsuyu, Chimu culture was not eradicated and some still resented foreign rule. Castro saw a chance to gain allies against the Tawantinsuyu and began south as quickly as possible once he realized Quisquis would not be blocking him.

The Tawantinsuyu quickly seized any Spaniards outside of Castro's domain when they heard what had happened at Tumbez. The way stations had never really developed any stockpiles of gunpowder and traveling Spaniards had nowhere near enough supplies to fill the stores of the Empire. So the Tawantinsuyu's gunpowder reserves were not going to be filled up anytime soon.

The realities of the Empire's situation meant that the Tawantinsuyu Navy had not received the attention the army had since contact with Eurpeans had begun. As a consequence when open fighting began Spanish ships, of which Castro had many, were the undisputed rulers of the sea. They were a critical part of Castro's bombardment of Tumbez and would remain an important piece of his campaigns along the coast.

The north saw an increase in fighting as the tribes of the northeastern Andes began to encroach on Tawantinsuyu lands. For the sake of the dream of Iron production substantial forces had been left with Manco Capac in the south to protect against any possible raids. This in turn drained the defenses of the northern Empire, as the vast majority of troops moved to fight Castro ended up being from the Chinchasuyu. So the northern tribes began to press south again, looking for their old lands, and maybe some revenge along the way.

Large numbers of solders remained in the south, and Manco Capac was generally well regarded among the locals so despite an increase in raids coming from the Mapuche very little changed for now in the desert.

But despite these other battles the war would be decided by the armies along the coast. Castro had forgone fighting Quisquis, leaving the general sitting in Saña unsure of what to do. His army was still disorganized, and valuable time was spent reorganizing it cohesively. It was quickly apparent that he was not going to have time to do even that, the Tawantinsuyu had to act quickly if they were to stop the Spanish from gaining allies and beginning to negate the Tawantinsuyu numbers advantage. In mid-December his army received reinforcements in the form of an army descending from the mountains, headed by Atahualpa. The presence of the Sapa Inka inspired his troops greatly, but inspiration could only go so far and the army departed Saña in a still somewhat ramshackle state, a state not helped by the tuberculosis epidemic that was now spreading through the ranks of both armies.

Atahualpa had a plan. It was not a grand plan with lots of intricate parts, but it was a plan. His goal was to fight Castro until the Spaniard bled dry, Atahualpa would do his best to fight as many bloody battles as he could. The Tawantinsuyu had men to spare, and the Spanish (for the moment) did not. Enough casualties and Castro would have to either flee or come to terms like Belalcázar had. The prospect of Castro gaining allies was concerning, but Atahualpa was confident a heavy hand could bring enough of his subjects back in line to make his strategy work.

It was a plausible plan, right up until about 3 days after when the Tawantinsuyu Army left Saña, racing to catch up with Castro. That night the Sapa Inka began to sweat profusely. This in it of itself was not especially concerning, the climate in the region was warmer then the mountain air he was used to. But the next morning he began to complain of chills and became very tired, very quickly. His appetite was greatly reduced. Soon he was coughing persistently. Those around him knew the signs well, they had plagued the army for weeks by this point. The Sapa Inka had Tuberculosis. Some held out hope, none of the great European diseases had touched the Son of the Sun before, and it seemed possible that his divine blood would protect him. But as said divine blood began to spit out of his lungs, it became apparent that the Sapa Inka was in for a long, possibly fatal, spell of the disease. Atahualpa began to lose weight rapidly, and grew weaker by the day. At first he tried to press on, but soon his march ground to a halt as Atahualpa became bedridden. Quisquis did not dare abandon the Sapa Inka, and so the offensive stalked, barely outside of Saña. The army hoped and prayed for a recovery, all while Castro slipped from their grasp. But Atahualpa was rapidly losing weight, and the end was rapidly approaching. Atahualpa began to prepare for the inevitable. He openly declared his desire for Illaquita to succeed him as Sapa Inka, a declaration most had seen coming. Atahualpa reiterated his opposition to any sort of conversion to Catholicism, not that any priests are allowed near his camp. With no more rebellions to quell, no more regions to balance, he did what he had always wanted to and declared Quito a capital of the Tawantinsuyu, the heart of the world to Cusco's naval. On December 20th, 1547 Atahualpa, known more formally as Tikki Capac, Sapa Inka, Inka Qhapaq, Apu, King of Quito and Son of the Sun breathed his last. Atahualpa had never been meant to be Sapa Inka, and only by the hand of smallpox had he risen so far, but he had done well. He was 45 years old, had led the Tawantinsuyu for two decades, and for 14 years he had stood stalwart against Spain[2].

Before his passing Atahualpa had secured promises from Quisquis that the general would support Illaquita in any succession crisis and Quisquis was true to his word. Sensing, probably correctly, that ensuring a stable succession was more important then stopping Castro from reaching Chan Chan Quisquis retraced his steps back to Saña. Setting a large segment of his force to defend the town he climbed the Chancay Road, hoping to link up with an army of last resort that had been placed where the road entered the mountains. However when he arrived at the top the army was gone. Illaquita had beaten him to it.

The second son of Atahualpa had been headed north, hoping to mediate a minor dispute just north of Cajacamara. But when he received news that was father was ill he headed straight for the army. He announced to the men that, in the interest of stability during Atahualpa's incapacitation, they would be moving towards Cusco. With little time for debate they departed. Illaquita blocked every messenger he could find, shielding Cusco from news of his father's illness. He sent forth his own proclamations, claiming that the army was just passing through on its way to reinforce his uncle in the south. Rumors still spread of course, and many nobles of Cusco reaffirmed to each other that they would support Quispe-Tupac in the case of a succession crisis, but none dared move, for fear of Atahualpa crushing them for good. By the time word of his fathers death reached him Illaquita was just a few days fast march from Cusco. He was unable to prevent word from reaching Cusco, but by the time enough nobles met to plot rebellion it was too late. Illaquita was upon them, there was not time to organize an army in opposition. The Quitians in the capital all favored Illaquita. Priests found efforts to muddle the succession stymied from an unlikely source. Ninancoro may have been an uninspired thinker, but he enjoyed his position as High Priest of the Sun and recognized he would have no viable chance to become Sapa Inka. So he sided with the brother who looked sure to win, keeping religious figures from rebelling against Illaquita.

Illaquita our new Sapa Inka

To the European calendar it was New Year's Eve when Illaquita entered Cusco. His army has entered the day before and quelled what little resistance emerged. He was greeted by Ninancoro, who affirmed that the priesthood supported his "divine brother's" ascension. Cusco seethed, particularly when world of Atahualpa's dying declaration was received. But even Illaquita's small force out weighed anything they could muster. So Quispe-Tupac reluctantly bowed before his brother. Illaquita arranged to marry his sister Cura Huarcay to shore up his royal bloodline, but did not immediately preform the ceremony.. He then turned his army and headed north once again, leaving only a small garrison to secure Quito.

The Spanish were rampaging the lowlands. The far north was practically under siege. Cusco was a spark away from rebellion. Plague was decimating the Empire. Manco Capac hadn't even heard his brother was dead yet, let alone weighed in on the decision.

But Illaquita wasn't worried. He had dreams for his new empire. Big ones…

_____

1: Far across the multiverse the Italians and the Austro-Hungarians scoff.

2: Raise a glass my

atillcha-kuna, raise a glass to the Sapa Inka.