Interview with Alf

The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, 3-532, September 19th, 1986

Interior – Studio

Host Johnny Carson sits at a small table. A fuzzy, big nosed puppet (Alf) “sits” in a chair next to him. On the couch beside him are David Letterman[1] and Ed McMahon.

JC: Welcome back, everyone, my next guest has travelled to us all the way from the planet Melmac to star in NBC’s newest comedy. Everyone, I’d like to introduce you to Alf.

Audience applauds.

Alf: Thank you, thank you, Mr. Carson it is such an honor to be here.

Not Exactly this Interview (Image source “noiselesschatter.com”)

JC: So, Alf, your new show, simply titled “Alf”, is playing Monday nights at 8 Eastern right here on NBC, starting this coming Monday.

Alf: That’s right, big guy!

JC: So, Alf…may I call you Alf?

Alf: Sure thing, Johnny! May I call you Johnny?

JC: Ah, no.

Audience laughs.

Alf: (obnoxious laugh) Ha, the classics! Slays ‘em every time!

JC: Now Alf, tell us a little about yourself.

Alf: Well, Johnny, I’m just a simple guy from the planet Melmac looking to make my way in entertainment. You see, television on Melmac is terrible. We’re talking “Leave it to Bleergmarrl” and “All my Saucers”. So, I left. I wanted to visit somewhere with class. Somewhere with culture. Somewhere with that (gestures) je ne cais quoi. So…Burbank!

Audience laughs.

JC: And how has Burbank treated you so far?

Alf: Well, the food could be better.

JC: How so?

Alf: Not a decent cat grill in the city!

Uncomfortable mix of laughs and groans.

JC: You eat cats?!?

Alf: Yea. Don’t you?

JC: Um, not quite.

David Letterman (interrupting): I’d make a pointed comment here, but I’m sure the, um, censors would have me thrown out.

Audience laughs.

Alf: Ok, so. I get to the cosmopolitan jewel that is Burbank where I’m introduced to Producer Bernie Brillstein with MGM Studios. It was my big break!

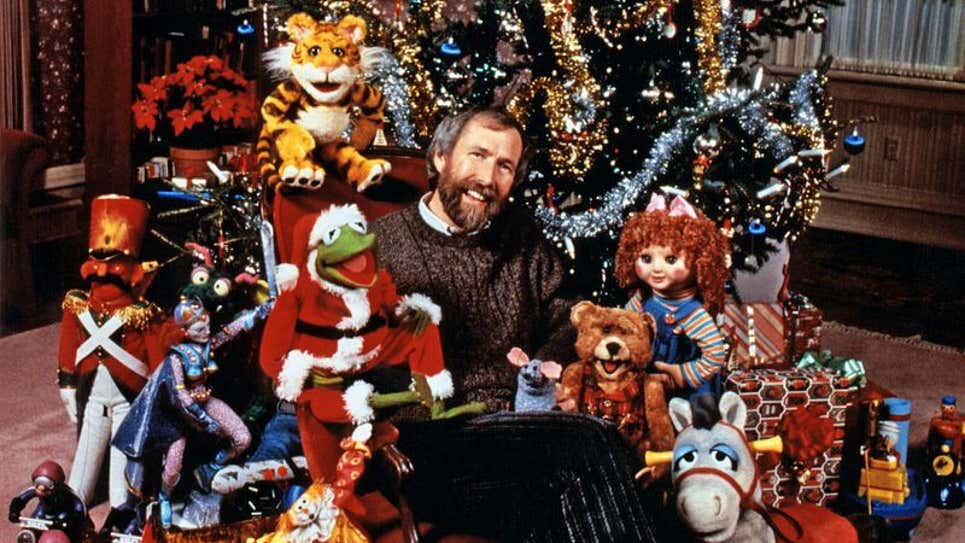

JC: He was the man who discovered Jim Henson and the Muppets, if I remember correctly.

Alf: Yes. I met Jim, actually.

JC: Really? How did that go?

Alf: At first, he didn’t want to hire me. He thought I was too much like the Muppets[2]. I mean, come on! Muppets are from Earth. I’m from Melmac! Whole different planet!

JC: What about Gonzo…any relation?

Audience laughs.

Alf: Are you kidding? With that schnozz?

Audience laughs.

Alf: (laughing at own joke, slapping knee) Ha! I kill me! Look, Jim and I get along great now. I even met Kermit. I’m a big fan. He was a real inspiration. He was a little frog from a swamp with a big dream to make millions of people happy. I was a little Melmacian with a big dream too: to make millions…

Audience laughs.

JC: …of people happy?

Alf: Just “millions”.

Audience laughs.

JC: Now, Alf, tell us about your new series.

Alf: Ok, it’s kind of autobiographical. It’s about an alien named Alf played by me, only “A-L-F” in this case stands for “Alien Life Form”, so it’s like a joke since Alf is my given name[3].

JC: Is Alf short for anything? Alfonso? Alfredo?

DL: Al Fresco?

Audience laughs.

Alf: Yea, it’s short for (long gesture with hand) “Aaaallllllffffffff”.

Audience laughs haltingly.

Alf: Ha! I kill me! So, in the show I get adopted by the suburban Tanner family, and they keep me hidden from the authorities who would want to run experiments on me.

JC: That sounds horrifying.

Alf: Well, it’s a SITCOM, so really, it’s funny stuff. Alien dissection. Great for the kids!

Audience laughs.

JC: But in reality, you, the real Alf, are out in the open, not hiding.

DL: (interrupting) Out of the closet.

Audience laughs. Johnny and Alf laugh too.

Alf: Yea, after all that controversy with E.T. the government decided that alien testing wasn’t publicly acceptable. Good friend of mine, E.T. He really needs to lay off the candy, though.

Audience laughs.

JC: I guess cats would be better?

Alf: More protein!

Audience groans.

Alf: (pretending to pull at a non-existent collar) Yeesh…tough audience.

JC: So, are you romantically involved at the moment?

Alf: Well, I was hoping to ask out Janet of the Muppets band, but she’s totally involved with Floyd Pepper. And I’m not going to cross a man whose best friend is Animal!

Audience and Johnny laugh.

JC: And with that, we need to take a commercial break. Alf, thank you for visiting us tonight!

Alf: It was my pleasure, Johnny!

JC: That’s “Mr. Carson.”

Audience laughs. Alf laughs and slaps knee.

JC: Make sure to see “Alf”, Monday nights at 8 Eastern, 7 Central, here on NBC!

[The Tonight Show theme plays as they cut to commercial]

[1] Strangely enough, David Letterman was on this episode in our timeline too!

[2] Brillstein recounts Henson being initially upset about him taking on Alf creator Paul Fusco as a client, afraid that there’d be brand confusion with the Muppets.

[3] Alf’s “real name” name “Gordon Shumway” doesn’t appear until later in the series.

The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, 3-532, September 19th, 1986

Interior – Studio

Host Johnny Carson sits at a small table. A fuzzy, big nosed puppet (Alf) “sits” in a chair next to him. On the couch beside him are David Letterman[1] and Ed McMahon.

JC: Welcome back, everyone, my next guest has travelled to us all the way from the planet Melmac to star in NBC’s newest comedy. Everyone, I’d like to introduce you to Alf.

Audience applauds.

Alf: Thank you, thank you, Mr. Carson it is such an honor to be here.

Not Exactly this Interview (Image source “noiselesschatter.com”)

JC: So, Alf, your new show, simply titled “Alf”, is playing Monday nights at 8 Eastern right here on NBC, starting this coming Monday.

Alf: That’s right, big guy!

JC: So, Alf…may I call you Alf?

Alf: Sure thing, Johnny! May I call you Johnny?

JC: Ah, no.

Audience laughs.

Alf: (obnoxious laugh) Ha, the classics! Slays ‘em every time!

JC: Now Alf, tell us a little about yourself.

Alf: Well, Johnny, I’m just a simple guy from the planet Melmac looking to make my way in entertainment. You see, television on Melmac is terrible. We’re talking “Leave it to Bleergmarrl” and “All my Saucers”. So, I left. I wanted to visit somewhere with class. Somewhere with culture. Somewhere with that (gestures) je ne cais quoi. So…Burbank!

Audience laughs.

JC: And how has Burbank treated you so far?

Alf: Well, the food could be better.

JC: How so?

Alf: Not a decent cat grill in the city!

Uncomfortable mix of laughs and groans.

JC: You eat cats?!?

Alf: Yea. Don’t you?

JC: Um, not quite.

David Letterman (interrupting): I’d make a pointed comment here, but I’m sure the, um, censors would have me thrown out.

Audience laughs.

Alf: Ok, so. I get to the cosmopolitan jewel that is Burbank where I’m introduced to Producer Bernie Brillstein with MGM Studios. It was my big break!

JC: He was the man who discovered Jim Henson and the Muppets, if I remember correctly.

Alf: Yes. I met Jim, actually.

JC: Really? How did that go?

Alf: At first, he didn’t want to hire me. He thought I was too much like the Muppets[2]. I mean, come on! Muppets are from Earth. I’m from Melmac! Whole different planet!

JC: What about Gonzo…any relation?

Audience laughs.

Alf: Are you kidding? With that schnozz?

Audience laughs.

Alf: (laughing at own joke, slapping knee) Ha! I kill me! Look, Jim and I get along great now. I even met Kermit. I’m a big fan. He was a real inspiration. He was a little frog from a swamp with a big dream to make millions of people happy. I was a little Melmacian with a big dream too: to make millions…

Audience laughs.

JC: …of people happy?

Alf: Just “millions”.

Audience laughs.

JC: Now, Alf, tell us about your new series.

Alf: Ok, it’s kind of autobiographical. It’s about an alien named Alf played by me, only “A-L-F” in this case stands for “Alien Life Form”, so it’s like a joke since Alf is my given name[3].

JC: Is Alf short for anything? Alfonso? Alfredo?

DL: Al Fresco?

Audience laughs.

Alf: Yea, it’s short for (long gesture with hand) “Aaaallllllffffffff”.

Audience laughs haltingly.

Alf: Ha! I kill me! So, in the show I get adopted by the suburban Tanner family, and they keep me hidden from the authorities who would want to run experiments on me.

JC: That sounds horrifying.

Alf: Well, it’s a SITCOM, so really, it’s funny stuff. Alien dissection. Great for the kids!

Audience laughs.

JC: But in reality, you, the real Alf, are out in the open, not hiding.

DL: (interrupting) Out of the closet.

Audience laughs. Johnny and Alf laugh too.

Alf: Yea, after all that controversy with E.T. the government decided that alien testing wasn’t publicly acceptable. Good friend of mine, E.T. He really needs to lay off the candy, though.

Audience laughs.

JC: I guess cats would be better?

Alf: More protein!

Audience groans.

Alf: (pretending to pull at a non-existent collar) Yeesh…tough audience.

JC: So, are you romantically involved at the moment?

Alf: Well, I was hoping to ask out Janet of the Muppets band, but she’s totally involved with Floyd Pepper. And I’m not going to cross a man whose best friend is Animal!

Audience and Johnny laugh.

JC: And with that, we need to take a commercial break. Alf, thank you for visiting us tonight!

Alf: It was my pleasure, Johnny!

JC: That’s “Mr. Carson.”

Audience laughs. Alf laughs and slaps knee.

JC: Make sure to see “Alf”, Monday nights at 8 Eastern, 7 Central, here on NBC!

[The Tonight Show theme plays as they cut to commercial]

[1] Strangely enough, David Letterman was on this episode in our timeline too!

[2] Brillstein recounts Henson being initially upset about him taking on Alf creator Paul Fusco as a client, afraid that there’d be brand confusion with the Muppets.

[3] Alf’s “real name” name “Gordon Shumway” doesn’t appear until later in the series.