Chapter 11, An EGOT Case

Excerpt from Where Did I Go Right? (or: You’re No One in Hollywood Unless Someone Wants You Dead), by Bernie Brillstein (with Cheryl Henson)

People inevitably accuse me on getting into the music production game just so that I could complete my EGOT[1]. Guess what? They’re right! I make no excuses. I now have the full collector’s set of gaudy golden dust catchers in a glass case on my shelf. And like my friend and fellow EGOT Mel Brooks, I prefer to use the French pronunciation for my EGOT, with the silent T.

Yes, I’m shameless. Sue me. But damn if I didn’t have fun! Not only did I produce albums through Disney Music for all the kid’s stuff (1987’s Waggle Rockin’ won me the Grammy for Best Children’s Album and satisfied my EGOT), but I convinced Tom Wilhite to launch a Hyperion Music label to produce more adult fare. In addition to scores and soundtracks for Hyperion productions, we signed original artists. My first sign was Thelonious Monster, a weird Jazz/Rock/Rap fusion group that I can’t even begin to understand. The name sounded to me like a Sesame Street Muppet. But Jim loved them, and as always, I trust Jim’s judgement. They never sold Gold or breached the Top 100, but got some Grammy noms, found a good and mildly profitable niche audience, and inspired a lot of later bands. Thelonious Monster T-shirts are apparently one of those things (along with Misfits shirts) that even today kids wear to show that they’re “cultured but rebellious”. It’s amazing how profitable rebellion can be for big corporations like Disney.

Hyperion Music was never going to compete with the big boys like Geffen, Virgin, or EMI, but it would make its mark. We signed some real talent over the next couple of years, like Jane's Addiction (at the suggestion of Thelonious Monster), They Might Be Giants (David Lazer saw them in New York and figured correctly that Jim would like them), Stone Temple Pilots (a San Diego band one of the Imagineers suggested), and The Liquid Drifters[2] (another of those weird things).

Movies kept going well. My partnerships with my old SNL friends continued. Steve Martin had his passion project Roxanne, a retelling of Cyrano De Bergerac. Danny Ackroyd and Tom Hanks starred in the comedic retelling of the old radio/TV drama Dragnet[3] in partnership with Universal. Miracle, the story about the Japan Airlines Flight 123 that somehow made a crazy emergency landing in the bay, made a modest profit thanks to being a hit in Japan despite under-performing in the US. And sure, it wasn’t all perfect. Weird Al Yankovic’s The Vidiots barely broke even, though it would go on to become a cult classic. The Fred Savage and Judge Reinhold helmed Vice Versa, a Freaky Friday type thing, broke even when marketing and distribution were considered. And Ron Miller launched a Jim Thorpe biopic that underperformed.

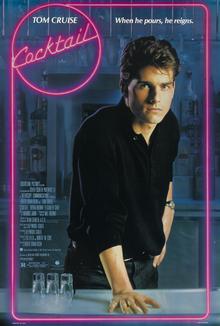

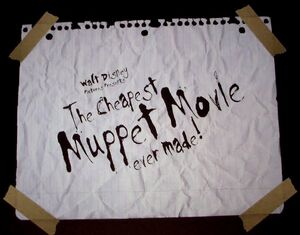

But for the most part there were more hits than misses. Jim brought me a script for Fantasia called Alien Nation, a Sci-Fi story about racism that he loved and which did pretty good (but far from great) at the box office, and later became a cult classic. And we also launched The Cheapest Muppet Movie Ever Made, which it literally was, all but guaranteeing a great profit by simply being too cheap to fail. Frank Oz had moved on to other things, so we brought back Ken Kwapis, who directed Follow that Bird. Finally, Diana took over a script from Universal called Cocktail[4], a dark take on the seemingly glamourous life of a bartender in New York. Author Heywood Gould was annoyed with the changes that Universal wanted, and remarked how we were more willing to work with our creative artists than most studios.

Steve and Lisa even approached me with a script Steve’s sister Anne and her neighbor Gary Ross had written about a teenage boy who gets transformed into an adult. Michael Richards and Jim Carrey both lobbied hard for the lead role, but Anne and Gary wanted Tom Hanks and wanted Penny Marshall to direct. Damned if we didn’t get them. Big released in the early fall hoping to capitalize on back-to-school angst and would go on to gross $152 million. It earned Gary and Anne and Penny and Tom Oscar nominations, and proved to the world what I knew all along, that Tom Hanks had dramatic chops[5].

Meanwhile, I got to have my own wish come true when I found out that Terry Gilliam’s next movie in his sort-of-trilogy was The Adventures of Baron von Munchhausen. As you’re probably sick of hearing me tell you, my Uncle Jack Pearl, the man who inspired me to go into The Business, used to play the Baron on the radio. Not only did I jump at the chance to produce it, but I made sure that it was dedicated to the memory of Uncle Jack, who passed in 1982. I still consider it “his movie”. It would go on to make $115 million that Christmas season against a $35 million budget[6].

Meanwhile, Robin Williams, who was playing the King of the Moon in Munchausen, approached me with another idea: Good Morning, Vietnam[7]. He’d been itching to greenlight the project since ‘79 when he and his agent, Larry Brezner, first optioned Adrian Cronauer's original pitch for a TV show. Williams had seen Red Ball Express and saw it as proof that you could do a war comedy. I greenlit it on the spot and we filmed it simultaneously with Baron von Munchausen. It reached $124 million.

TV was going strong. We launched Roger Rabbit’s Radical Revue, Alf Tales, and Max and the Wild Things on Saturday Mornings, all to great success. Duck, Duck, Goof spawned the spinoff Mickey in the City where Mickey Mouse moves to Big Cheese City and struggles with keeping a job, dating Minnie, and doing the right thing[8]. The Rescuers series was doing very well, so we followed up with a series of The Aristocats, which had a fun, jazzy soundtrack and a musical educational purpose and did OK. We also launched the new Muppet-based shows Mickey’s Clubhouse and Farmyard Follies[9].

Live TV was going great overall. We pushed a new Golden Girls spinoff Empty Nest. For Hyperion we launched the new Mel Brooks series The Nutt House with Harvey Korman and Chloris Leachman, first on NBC (where it did poorly) and then moved it to the Hyperion Channel, where it had a three-season run with a small but dedicated audience[10]. Hyperion TV was starting to become known as “NBC’s junkyard”, but we didn’t care. An underperforming show on Network TV was a breakout hit by basic cable standards, so why waste a good concept? I thought of it like sending the kid that couldn’t cut it in the Majors down to the Minors, and watching him become the home run king there.

We also launched Jim’s next big idea: Inner-Tube, a crazy variety show where we sent our guest stars inside the television for wacky adventures and variety content (the Betty White episode is legendary). It got nominated for a Best Variety Series Emmy, but had high costs and mixed ratings, so it died on the vine. One of those “ahead of its time” things. It’s best remembered today as the place where Tom Whedon’s son Joss cut his writing teeth. We’d relaunch it a decade later when the computer effects costs were far less, where it became a small hit.

But it was Broadway where I began to make my biggest mark. I got a call from my soon-to-be-fellow EGOTist Mel Brooks to talk The Nutt House, but then Broadway came up. We got to talking and soon he said “we should do a show. Maybe something based on Young Frankenstein or, better yet, The Producers.”

“The Producers,” I said without hesitation. A Broadway show based on the movie about a Broadway show? It was either the most ingenious or the most idiotic idea ever. Either way, I was in.

Mel acted incredulous at first. “First you told me it had no legs, and now you want to make a musical about it,” he said to me.

“You’re still going to hold that one against me?” I told him.

“Absolutely,” he said. “So, which of us is Bialystok and which is Blum?”

“I’m the fat one,” I told him. “You figure it out.”

Anyway, we started it Off Broadway in ’88, but soon enough we grabbed a spot at the St. James theater when we got good reviews and started selling out. Mel wrote the script and the song lyrics and we got Menken to arrange and compose the music. We got Buddy Hackett and Ben Stiller to play Bialystok and Blum, the great Robert Preston as De Bris, young but talented Alec Baldwin as LSD[11], Werner Klemperer as the Nazi (naturally), and the fabulous (and gorgeous) Donna King for Ulla. We practically swept the Tonys in ’89, giving Mel his EGOT. It was going so well that I contacted Lord Lew Grade and he called up some colleagues and set us up on the West End with Michael Palin producing and the main characters now Londoners Barrymore and Brown. It did OK.

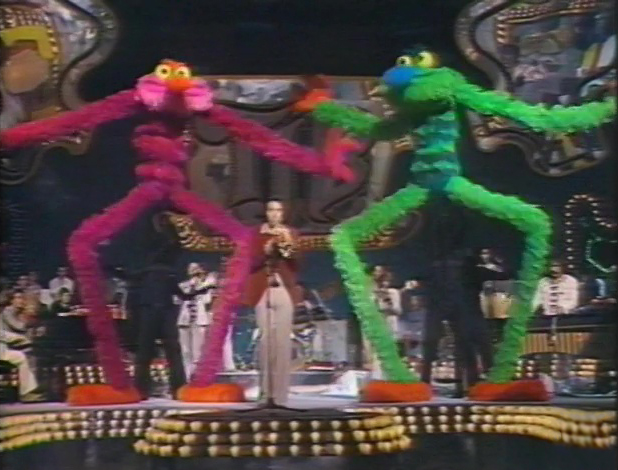

But that wasn’t the end of my burgeoning Broadway run. For decades Jim had wanted to do a Broadway showcase of his amazing experimental puppetry work: Big Boss Man, Limbo, and the rest. David Lazer and I had a surprise for him. We arranged a deal with the City of New York: a public-private partnership to restore the Palace Theater and in exchange the newly renovated theater would debut Muppetational!, a musical directed by the great Julie Taymor featuring a whole array of strange and wacky Muppet characters from the familiar (Kermit and the like) to the experimental, animatronic, digital, new, and bizarre.

I swear that Jim had a tear in his eye when we told him.

[1] EGOT = Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony, for those who don’t know the acronym.

[2] Fictional. Think of it as one of those genre-bending early ‘90s things; the type of band that has a Dobro, a sax, a sitar, a synth, an electric bass, and a 20-piece drum set.

[3] Which Bernie produced in our timeline.

[4] Went to Touchstone in our timeline where Eisner and Katzenberg continued to make it lighter and simpler, creating a breakout hit that critics hated but audiences loved. The book itself is more like Anthony Bourdin’s Kitchen Confidential in fictional format.

[5] Produced by James L. Brooks’ Gracie Films and distributed by 20th Century Fox in our timeline. Here Lisa Henson convinced Anne Spielberg to go to Bernie.

[6] In our timeline Gilliam went to Columbia, who tried and failed to constrain him to a $25 million budget. Reports say the film cost as much as $46.63 million, though Gilliam swears he spent only the $35 million he originally asked for. Furthermore, a change in leadership at Columbia (David Puttnam out, Dawn Steel in) led to a deliberate sabotage of the film by the new management. It received a very limited distribution and earned a mere $8 million. To quote Gilliam, “the problem was that David Puttnam got fired, and all these deals were oral deals. ... Columbia's new CEO, Dawn Steel, said ‘Whatever David Puttnam [has] said before doesn't interest me’”. Robin Williams said of this decision, “[Puttnam's] regime was leaving, the new one was going through this, and they said, ‘This was their movies, now let's do our movies!’ It was a bit like the new lion that comes in and kills all the cubs from the previous man.”

[7] Produced by Touchstone in our timeline.

[8] In our timeline Mickey increasingly became a flat corporate mascot throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s to the point where your average person, if asked what Mickey’s personality was like, would draw a blank. Jim and Roy are deliberately attempting to remind audiences why they love the Mouse. They are going for a sincere but slightly befuddled Everyman type, “a Frank Capra character”.

[9] The former is somewhat self-explanatory. The latter is a Vaudevillesque song-and-dance show with Muppet Farm Animals that teaches music and music history.

[10] Cancelled quickly in our timeline.

[11] A character from the movie cut from the 2001 show, I guess because hippies were too far out of public memory??? LSD (his initials) plays Hitler in the Show within a Show.

Excerpt from Where Did I Go Right? (or: You’re No One in Hollywood Unless Someone Wants You Dead), by Bernie Brillstein (with Cheryl Henson)

People inevitably accuse me on getting into the music production game just so that I could complete my EGOT[1]. Guess what? They’re right! I make no excuses. I now have the full collector’s set of gaudy golden dust catchers in a glass case on my shelf. And like my friend and fellow EGOT Mel Brooks, I prefer to use the French pronunciation for my EGOT, with the silent T.

Yes, I’m shameless. Sue me. But damn if I didn’t have fun! Not only did I produce albums through Disney Music for all the kid’s stuff (1987’s Waggle Rockin’ won me the Grammy for Best Children’s Album and satisfied my EGOT), but I convinced Tom Wilhite to launch a Hyperion Music label to produce more adult fare. In addition to scores and soundtracks for Hyperion productions, we signed original artists. My first sign was Thelonious Monster, a weird Jazz/Rock/Rap fusion group that I can’t even begin to understand. The name sounded to me like a Sesame Street Muppet. But Jim loved them, and as always, I trust Jim’s judgement. They never sold Gold or breached the Top 100, but got some Grammy noms, found a good and mildly profitable niche audience, and inspired a lot of later bands. Thelonious Monster T-shirts are apparently one of those things (along with Misfits shirts) that even today kids wear to show that they’re “cultured but rebellious”. It’s amazing how profitable rebellion can be for big corporations like Disney.

Hyperion Music was never going to compete with the big boys like Geffen, Virgin, or EMI, but it would make its mark. We signed some real talent over the next couple of years, like Jane's Addiction (at the suggestion of Thelonious Monster), They Might Be Giants (David Lazer saw them in New York and figured correctly that Jim would like them), Stone Temple Pilots (a San Diego band one of the Imagineers suggested), and The Liquid Drifters[2] (another of those weird things).

Movies kept going well. My partnerships with my old SNL friends continued. Steve Martin had his passion project Roxanne, a retelling of Cyrano De Bergerac. Danny Ackroyd and Tom Hanks starred in the comedic retelling of the old radio/TV drama Dragnet[3] in partnership with Universal. Miracle, the story about the Japan Airlines Flight 123 that somehow made a crazy emergency landing in the bay, made a modest profit thanks to being a hit in Japan despite under-performing in the US. And sure, it wasn’t all perfect. Weird Al Yankovic’s The Vidiots barely broke even, though it would go on to become a cult classic. The Fred Savage and Judge Reinhold helmed Vice Versa, a Freaky Friday type thing, broke even when marketing and distribution were considered. And Ron Miller launched a Jim Thorpe biopic that underperformed.

But for the most part there were more hits than misses. Jim brought me a script for Fantasia called Alien Nation, a Sci-Fi story about racism that he loved and which did pretty good (but far from great) at the box office, and later became a cult classic. And we also launched The Cheapest Muppet Movie Ever Made, which it literally was, all but guaranteeing a great profit by simply being too cheap to fail. Frank Oz had moved on to other things, so we brought back Ken Kwapis, who directed Follow that Bird. Finally, Diana took over a script from Universal called Cocktail[4], a dark take on the seemingly glamourous life of a bartender in New York. Author Heywood Gould was annoyed with the changes that Universal wanted, and remarked how we were more willing to work with our creative artists than most studios.

Steve and Lisa even approached me with a script Steve’s sister Anne and her neighbor Gary Ross had written about a teenage boy who gets transformed into an adult. Michael Richards and Jim Carrey both lobbied hard for the lead role, but Anne and Gary wanted Tom Hanks and wanted Penny Marshall to direct. Damned if we didn’t get them. Big released in the early fall hoping to capitalize on back-to-school angst and would go on to gross $152 million. It earned Gary and Anne and Penny and Tom Oscar nominations, and proved to the world what I knew all along, that Tom Hanks had dramatic chops[5].

Meanwhile, I got to have my own wish come true when I found out that Terry Gilliam’s next movie in his sort-of-trilogy was The Adventures of Baron von Munchhausen. As you’re probably sick of hearing me tell you, my Uncle Jack Pearl, the man who inspired me to go into The Business, used to play the Baron on the radio. Not only did I jump at the chance to produce it, but I made sure that it was dedicated to the memory of Uncle Jack, who passed in 1982. I still consider it “his movie”. It would go on to make $115 million that Christmas season against a $35 million budget[6].

Meanwhile, Robin Williams, who was playing the King of the Moon in Munchausen, approached me with another idea: Good Morning, Vietnam[7]. He’d been itching to greenlight the project since ‘79 when he and his agent, Larry Brezner, first optioned Adrian Cronauer's original pitch for a TV show. Williams had seen Red Ball Express and saw it as proof that you could do a war comedy. I greenlit it on the spot and we filmed it simultaneously with Baron von Munchausen. It reached $124 million.

TV was going strong. We launched Roger Rabbit’s Radical Revue, Alf Tales, and Max and the Wild Things on Saturday Mornings, all to great success. Duck, Duck, Goof spawned the spinoff Mickey in the City where Mickey Mouse moves to Big Cheese City and struggles with keeping a job, dating Minnie, and doing the right thing[8]. The Rescuers series was doing very well, so we followed up with a series of The Aristocats, which had a fun, jazzy soundtrack and a musical educational purpose and did OK. We also launched the new Muppet-based shows Mickey’s Clubhouse and Farmyard Follies[9].

Live TV was going great overall. We pushed a new Golden Girls spinoff Empty Nest. For Hyperion we launched the new Mel Brooks series The Nutt House with Harvey Korman and Chloris Leachman, first on NBC (where it did poorly) and then moved it to the Hyperion Channel, where it had a three-season run with a small but dedicated audience[10]. Hyperion TV was starting to become known as “NBC’s junkyard”, but we didn’t care. An underperforming show on Network TV was a breakout hit by basic cable standards, so why waste a good concept? I thought of it like sending the kid that couldn’t cut it in the Majors down to the Minors, and watching him become the home run king there.

We also launched Jim’s next big idea: Inner-Tube, a crazy variety show where we sent our guest stars inside the television for wacky adventures and variety content (the Betty White episode is legendary). It got nominated for a Best Variety Series Emmy, but had high costs and mixed ratings, so it died on the vine. One of those “ahead of its time” things. It’s best remembered today as the place where Tom Whedon’s son Joss cut his writing teeth. We’d relaunch it a decade later when the computer effects costs were far less, where it became a small hit.

But it was Broadway where I began to make my biggest mark. I got a call from my soon-to-be-fellow EGOTist Mel Brooks to talk The Nutt House, but then Broadway came up. We got to talking and soon he said “we should do a show. Maybe something based on Young Frankenstein or, better yet, The Producers.”

“The Producers,” I said without hesitation. A Broadway show based on the movie about a Broadway show? It was either the most ingenious or the most idiotic idea ever. Either way, I was in.

Mel acted incredulous at first. “First you told me it had no legs, and now you want to make a musical about it,” he said to me.

“You’re still going to hold that one against me?” I told him.

“Absolutely,” he said. “So, which of us is Bialystok and which is Blum?”

“I’m the fat one,” I told him. “You figure it out.”

Anyway, we started it Off Broadway in ’88, but soon enough we grabbed a spot at the St. James theater when we got good reviews and started selling out. Mel wrote the script and the song lyrics and we got Menken to arrange and compose the music. We got Buddy Hackett and Ben Stiller to play Bialystok and Blum, the great Robert Preston as De Bris, young but talented Alec Baldwin as LSD[11], Werner Klemperer as the Nazi (naturally), and the fabulous (and gorgeous) Donna King for Ulla. We practically swept the Tonys in ’89, giving Mel his EGOT. It was going so well that I contacted Lord Lew Grade and he called up some colleagues and set us up on the West End with Michael Palin producing and the main characters now Londoners Barrymore and Brown. It did OK.

But that wasn’t the end of my burgeoning Broadway run. For decades Jim had wanted to do a Broadway showcase of his amazing experimental puppetry work: Big Boss Man, Limbo, and the rest. David Lazer and I had a surprise for him. We arranged a deal with the City of New York: a public-private partnership to restore the Palace Theater and in exchange the newly renovated theater would debut Muppetational!, a musical directed by the great Julie Taymor featuring a whole array of strange and wacky Muppet characters from the familiar (Kermit and the like) to the experimental, animatronic, digital, new, and bizarre.

I swear that Jim had a tear in his eye when we told him.

[1] EGOT = Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony, for those who don’t know the acronym.

[2] Fictional. Think of it as one of those genre-bending early ‘90s things; the type of band that has a Dobro, a sax, a sitar, a synth, an electric bass, and a 20-piece drum set.

[3] Which Bernie produced in our timeline.

[4] Went to Touchstone in our timeline where Eisner and Katzenberg continued to make it lighter and simpler, creating a breakout hit that critics hated but audiences loved. The book itself is more like Anthony Bourdin’s Kitchen Confidential in fictional format.

[5] Produced by James L. Brooks’ Gracie Films and distributed by 20th Century Fox in our timeline. Here Lisa Henson convinced Anne Spielberg to go to Bernie.

[6] In our timeline Gilliam went to Columbia, who tried and failed to constrain him to a $25 million budget. Reports say the film cost as much as $46.63 million, though Gilliam swears he spent only the $35 million he originally asked for. Furthermore, a change in leadership at Columbia (David Puttnam out, Dawn Steel in) led to a deliberate sabotage of the film by the new management. It received a very limited distribution and earned a mere $8 million. To quote Gilliam, “the problem was that David Puttnam got fired, and all these deals were oral deals. ... Columbia's new CEO, Dawn Steel, said ‘Whatever David Puttnam [has] said before doesn't interest me’”. Robin Williams said of this decision, “[Puttnam's] regime was leaving, the new one was going through this, and they said, ‘This was their movies, now let's do our movies!’ It was a bit like the new lion that comes in and kills all the cubs from the previous man.”

[7] Produced by Touchstone in our timeline.

[8] In our timeline Mickey increasingly became a flat corporate mascot throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s to the point where your average person, if asked what Mickey’s personality was like, would draw a blank. Jim and Roy are deliberately attempting to remind audiences why they love the Mouse. They are going for a sincere but slightly befuddled Everyman type, “a Frank Capra character”.

[9] The former is somewhat self-explanatory. The latter is a Vaudevillesque song-and-dance show with Muppet Farm Animals that teaches music and music history.

[10] Cancelled quickly in our timeline.

[11] A character from the movie cut from the 2001 show, I guess because hippies were too far out of public memory??? LSD (his initials) plays Hitler in the Show within a Show.

Last edited:

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-tronc.s3.amazonaws.com/public/36WOK5WAWBAB5HIOP43QC6D3WU.jpg)