Chapter 11: A Literal Small World…and a Figurative One

Post from the Riding with the Mouse Net-log by animator Terrell Little

We all knew that Mistress Masham’s Repose was going to get renamed. If Basil of Baker Street is too esoteric a name for modern audiences then surely that weird old school title was dead on arrival. We had a pool going for what we expected the ultimate title to be. Many went with the one-word thing, “Lilliputians!” or whatever. Andreas Deja, the main art director, was the only one to take the long-shot bet that the name wouldn’t change. I guessed “Maria’s World” and got close. I forget who ultimately guessed “A Small World,” which was, of course, the title Jim chose for the meta-joke. Could have been worse, I guess.

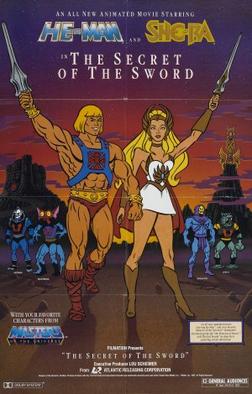

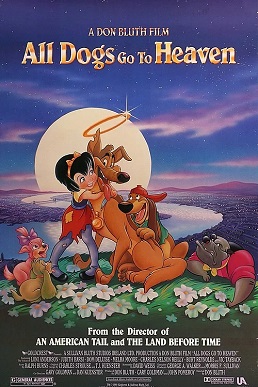

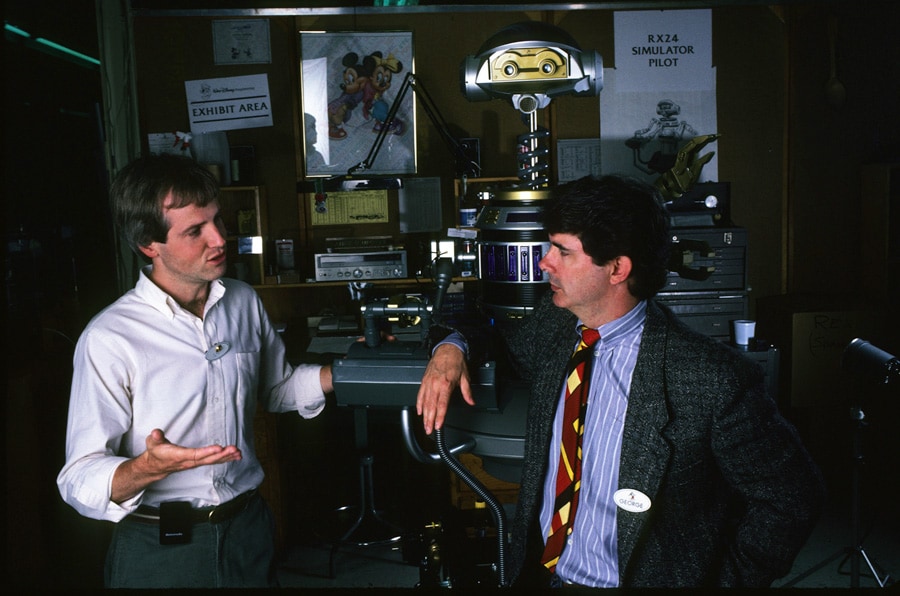

Original Andreas Deja concept art (source for all images in this post)

A Small World was a bit of a return to the Disney Classic Formula for us after The Black Cauldron’s terror, Elementary’s lack of original songs, and Where the Wild Things Are’s rock & roll stylings. We not only had Deja’s very classic art style as the guiding light, but we had original music by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, who’d done Little Shop of Horrors. Ron Clements and John Musker took the lead on direction while John and Howard did the production.

It was Alan and Howard’s first animated feature and a bit of a learning curve for them. As it turned out, the whole event would be a huge learning curve for me too, for reasons that I will elaborate on later. In the meantime, I got pulled into animating sequences for Maria’s big “I Want” song “A World of My Own”. It got awards. I’m proud that my animation could accompany it. What you didn’t know about it is that Howard in particular wryly admitted to us all just how much his earlier “Somewhere That’s Green” from Little Shop had influenced it. He and Alan jokingly called it “Somewhere That’s Small” in reference to the similarities[1].

Now, the big challenge for A Small World was that for a kid’s story it was actually pretty deep. Not only was it inspired by Jonathan Swift, it was going for that same kind of satire about colonialism. It all involved Maria, an orphaned heiress in the “care” of two awful caretakers that were conspiring to steal her fortune. And when she discovers a secret world of Lilliputians living on an island called Mistress Masham’s Repose on her family estate, well, that’s where things get crazy and deep.

So, Maria sets out to be the new lord and master of these small people and gets to be a bit of a petty tyrant. See what I mean about the colonialism thing? However, just as she’s learning about the limits and consequences of wielding power, she soon has to face not only her own sense of superiority, but has to stand up for what’s right and protect her newfound world from those who plan to exploit it in far more horrible ways.

Yea, it was a lesson I could get behind!

And yet it was ultimately a lesson that I had to learn myself. You see, well, there’s really no easy way to put this. I came from a strongly socially conservative place down in the Bible Belt, and while you’d think that being Black in Alabama would make you immediately open to seeing the humanity in others no matter what, the sad thing is that I grew up with plenty of prejudices of my own. And people who loved those of the same gender were, well, something that was not an easy thing for me and more than a few others at Disney to just accept. Now, it was foolish of me to think that no one I worked with was anything other than straight-as-an-arrow, but it was even more foolish to assume that they all shared my opinions, even if quite a few of them did.

I started talking with a few other artists who’d been working around Howard Ashman, who was openly gay, which was still controversial back then even in Hollywood. I ain’t proud of what we said and how we acted. I won’t share it here. I’ve done enough damage with those careless words. But Andreas overheard us. He’d never said anything up to that point that made me suspect anything, but when I saw the look on his face, I felt a knot in my stomach that wouldn’t go away. It was the exact same look I’d made a thousand times after overhearing the things some of the white folks I grew up around used to say.

Few people truly understand the bravery it can take just to be who you are in the face of a world that doesn’t value people like you. All my life I’d been an open opponent to such hate, and yet there I was failing to live up to my own standards. I worked hard to make amends, not just to Andreas, but in general. It wasn’t easy. You can’t unsay what was said and you don’t just shed twenty years of built-in bias overnight. But little by little I confronted and started to banish my own demons.

Who’s really the small person, the one who fails to meet others’ expectations on who to be and how to live, or the one who expects their own expectations to be universally met? If there’s one big lesson from Mistress Masham/A Small World that I want everyone to remember, it’s that the bravest, strongest, and indeed biggest people out there are sometimes the ones that everyone else looks down on.

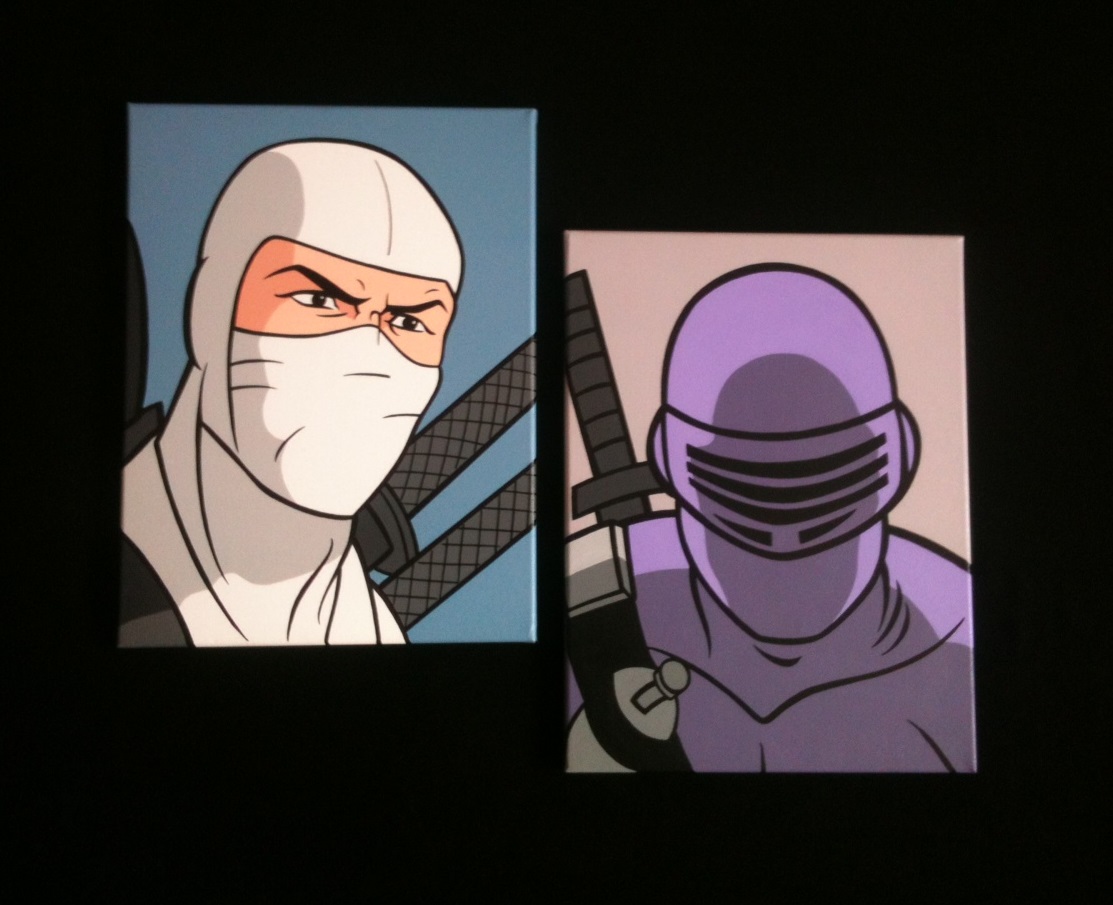

When I was ultimately asked to help design the movie poster, this was the lesson I took to heart. The image would not be from Maria’s perspective looking down on the Lilliputians, but from the perspective of the Lilliputians looking out at the great big glasses-framed eyes of Maria, in turn looking down on them through the hole in the wall.

[1] A similar thing happened in our timeline with “Part of Your World”, which Ashman jokingly called “Somewhere That’s Dry.”

Post from the Riding with the Mouse Net-log by animator Terrell Little

We all knew that Mistress Masham’s Repose was going to get renamed. If Basil of Baker Street is too esoteric a name for modern audiences then surely that weird old school title was dead on arrival. We had a pool going for what we expected the ultimate title to be. Many went with the one-word thing, “Lilliputians!” or whatever. Andreas Deja, the main art director, was the only one to take the long-shot bet that the name wouldn’t change. I guessed “Maria’s World” and got close. I forget who ultimately guessed “A Small World,” which was, of course, the title Jim chose for the meta-joke. Could have been worse, I guess.

Original Andreas Deja concept art (source for all images in this post)

A Small World was a bit of a return to the Disney Classic Formula for us after The Black Cauldron’s terror, Elementary’s lack of original songs, and Where the Wild Things Are’s rock & roll stylings. We not only had Deja’s very classic art style as the guiding light, but we had original music by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, who’d done Little Shop of Horrors. Ron Clements and John Musker took the lead on direction while John and Howard did the production.

It was Alan and Howard’s first animated feature and a bit of a learning curve for them. As it turned out, the whole event would be a huge learning curve for me too, for reasons that I will elaborate on later. In the meantime, I got pulled into animating sequences for Maria’s big “I Want” song “A World of My Own”. It got awards. I’m proud that my animation could accompany it. What you didn’t know about it is that Howard in particular wryly admitted to us all just how much his earlier “Somewhere That’s Green” from Little Shop had influenced it. He and Alan jokingly called it “Somewhere That’s Small” in reference to the similarities[1].

Now, the big challenge for A Small World was that for a kid’s story it was actually pretty deep. Not only was it inspired by Jonathan Swift, it was going for that same kind of satire about colonialism. It all involved Maria, an orphaned heiress in the “care” of two awful caretakers that were conspiring to steal her fortune. And when she discovers a secret world of Lilliputians living on an island called Mistress Masham’s Repose on her family estate, well, that’s where things get crazy and deep.

So, Maria sets out to be the new lord and master of these small people and gets to be a bit of a petty tyrant. See what I mean about the colonialism thing? However, just as she’s learning about the limits and consequences of wielding power, she soon has to face not only her own sense of superiority, but has to stand up for what’s right and protect her newfound world from those who plan to exploit it in far more horrible ways.

Yea, it was a lesson I could get behind!

And yet it was ultimately a lesson that I had to learn myself. You see, well, there’s really no easy way to put this. I came from a strongly socially conservative place down in the Bible Belt, and while you’d think that being Black in Alabama would make you immediately open to seeing the humanity in others no matter what, the sad thing is that I grew up with plenty of prejudices of my own. And people who loved those of the same gender were, well, something that was not an easy thing for me and more than a few others at Disney to just accept. Now, it was foolish of me to think that no one I worked with was anything other than straight-as-an-arrow, but it was even more foolish to assume that they all shared my opinions, even if quite a few of them did.

I started talking with a few other artists who’d been working around Howard Ashman, who was openly gay, which was still controversial back then even in Hollywood. I ain’t proud of what we said and how we acted. I won’t share it here. I’ve done enough damage with those careless words. But Andreas overheard us. He’d never said anything up to that point that made me suspect anything, but when I saw the look on his face, I felt a knot in my stomach that wouldn’t go away. It was the exact same look I’d made a thousand times after overhearing the things some of the white folks I grew up around used to say.

Few people truly understand the bravery it can take just to be who you are in the face of a world that doesn’t value people like you. All my life I’d been an open opponent to such hate, and yet there I was failing to live up to my own standards. I worked hard to make amends, not just to Andreas, but in general. It wasn’t easy. You can’t unsay what was said and you don’t just shed twenty years of built-in bias overnight. But little by little I confronted and started to banish my own demons.

Who’s really the small person, the one who fails to meet others’ expectations on who to be and how to live, or the one who expects their own expectations to be universally met? If there’s one big lesson from Mistress Masham/A Small World that I want everyone to remember, it’s that the bravest, strongest, and indeed biggest people out there are sometimes the ones that everyone else looks down on.

When I was ultimately asked to help design the movie poster, this was the lesson I took to heart. The image would not be from Maria’s perspective looking down on the Lilliputians, but from the perspective of the Lilliputians looking out at the great big glasses-framed eyes of Maria, in turn looking down on them through the hole in the wall.

[1] A similar thing happened in our timeline with “Part of Your World”, which Ashman jokingly called “Somewhere That’s Dry.”