Wrath of The Rhos

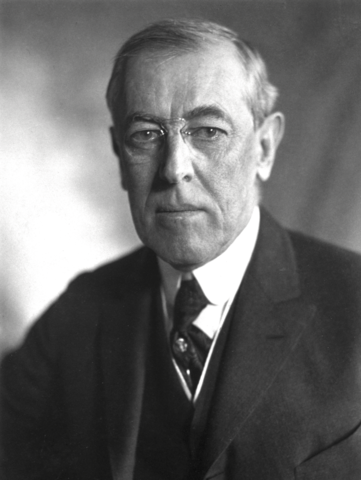

Nestor Makhno, Commander-in-Chief of the Black Army in Ukraine

Ukrainian Rumble

Nestor Makhno, Commander-in-Chief of the Black Army in Ukraine

Ukrainian Rumble

After securing control of the Don and Donbass, Brusilov and his Cossack allies had spent the month of September 1918 preparing for a major thrust into the Ukraine, the aim being to secure control of as much of the fertile if volatile region as possible, in order to strengthen the Don Whites in preparation for a renewed offensive on Tsaritsyn. However, a week before the planned thrust, Brusilov and Krasnov received representatives from the Kuban Army to the south, an insurgent Kuban Cossack force under the command of General Pokrovsky, which had fled Ekaterinodar following a socialist coup against the recently-established Kuban National Republic in early 1918 and had been fighting a losing battle for half a year. Pokrovsky begged for aid from the Don Whites and promised submission to their leadership if they would restore order to the region. After some deliberation, this prompted a reduction of the Ukrainian offensive while General Pyotr Wrangel, who increasingly found himself in Brusilov's good graces, serving as his right-hand man, was given command of the Kuban Expedition numbering some 8,000 men (1).

Brusilov set out with a force of some 80,000 men, half of which were Don Cossacks under Krasnov's leadership, and invaded the Yekatrinoslav Governate, which was held by a loosely affiliated faction of the Moscow-aligned Ukrainian Soviet Republic. This attack, coinciding with a renewed push by the Hetmanate to restore control of the eastern Ukraine, caught the Ukrainian Soviets from two sides and led to the collapse of Soviet control in the oblast, allowing the Don Whites to secure Luhansk three days into the offensive. On the 14th of October Brusilov marched into the town of Yuzovka and declared it liberated, only to find himself and his men clashing with the Hetmanates forces west of Yuzovka. The brief but sharp fight on the outskirts of Yuzovka would prove a major blow to the complex Don Cossack-Don White partnership when the Don Cossacks refused to fight against the German-aligned Hetmanate.

In the heated political conflict that ensued between Brusilov and Krasnov, it was revealed that the Germans were the main provider of arms for the Cossack Host, having been supplied with considerable grain shipments and a non-aggression agreement in return. As such, the Don Cossacks and Don Whites were ostensibly aligned on opposite sides of the Great War. With the Don Cossacks unwilling to jeopardise this relationship and the Don Whites too reliant on the Cossacks to risk a breach in relations, Brusilov found himself unable to press further westward, and instead turned his attentions north, towards the Muscovite-aligned city of Kharkhov. The march on Kharkhov would prove considerably harder than the preceding campaign, as Red sympathisers and Green forces caused havoc across the Yekatrinoslav region while Nestor Makhno's Moscow-aligned and rapidly growing Black Army turned eastward from their assault on the Hetmanate to push back the Don Whites. Intense clashes ensued north and north-west of Yuzovka and Luhansk which eventually forced Brusilov to call a halt to the offensive in mid-December 1918. It was around this time that news arrived from the Kuban that General Wrangel had successfully defeated the Kuban Soviet Republic and was marching north with 25,000 hardened veteran Kuban Cossacks to join Brusilov for his planned assault on Tsaritsyn in the new year.

While the Don Whites had thus inserted themselves into the wider conflict in the Ukraine, there was little doubt that the greater power in the region lay with the Germans under the command of General Alexander von Linsignen and their puppet government under Hetman Pavlo Skoropadskyi. The Hetmanate had experienced a troubled life since its establishment, with little support from the urban classes, nationalist intellectual or the wider peasantry, and was completely reliant on their patrons in Berlin and Vienna. Over the course the latter half of 1918, as the Hetman and his regime's extreme unpopularity became increasingly obvious and the Germans were forced to hand over ever greater parts of the occupation to Austro-Hungarian troops, the Hetmanate's position began to crumble.

This was the situation when Nestor Makhno, recently returned from pledging his allegiance to Moscow, launched his Black Army into occupied Northern Ukraine in September of 1918, his force having recently been armed with newly-produced arms from the foundries of Tula. Fighting a guerrilla war with the overstretched Hetmanate, Germans and Austro-Hungarians, he was able to push them back and spread his influence as far as the outskirts of Kiev by the time Brusilov and the Hetmanate launched their fateful blow into the Yekatrinoslav Governate Oblast. Abandoning what gains he had made in the region, Makhno rushed his forces eastward to halt the collapse of the Muscovite positions in eastern Ukraine. This bought Skoropadskyi another three months in power, during which time his regime found itself constantly dealing with Green rebels and an increasingly angry set of patrons, who felt that the Hetman's inability to restore order to the Ukraine left their support of him a questionable benefit. The Central Powers' thirst for resources seemed never ending and led to considerable food and heating shortages across the region, as it was stripped of anything and everything that Germany might need to repel the Allied offensives in the west. Once he had repelled the Don Whites' thrust against Kharkhov, Makhno and his army found themselves rushed back westward.

In the cold of early January 1919, Makhno and the Black Army launched an offensive against Kiev. This time there was little that the Central Powers or the Hetmanate could or would do to stop them. With the Germans having stripped the region of what forces they could while the Austro-Hungarians dealt with a massive influx of former prisoners of war and growing internal turmoil, the resistance to Makhno proved limited in nature. Thus, on the 18th of January 1919 Kiev fell to Makhno while Skoropadskyi fled to safety in Germany where he would spend the remainder of his life in exile. This prompted the collapse of the Ukrainian Hetmanate and spurred the entire region to rebellion as the Central Powers rushed troops back into the Ukraine to shore up their grip on power (2). Makhno pressed down the Dnieper in response and secured control of vast swathes of area in the process, in effect taking all of Ukraine east of the Dnieper and north of Yekatrinoslav. Not to be outdone, Brusilov dispatched General Wrangel and some 15,000 men westward as well, securing everything south of Yekatrinoslav and west of the Molochna River while preparations for the Tsaritsyn Campaign continued. The Germans were swift to consolidate their hold on Crimea and the lands between the Dnieper and Molochna Rivers, the Oddessa region and occupied much of the north-western and western Ukraine with the Austro-Hungarians.

General Wrangel and Makhno would clash in a series of significant battles across the region, most significantly around Alexandrovsk further south down the Dnieper. It was here, north of one of the great cities of the region, that Makhno and Wrangel met in the first of several major battles that would launch them to ever greater fame. Having rushed south along the rail lines, Makhno and his men were caught by surprise at Wrangel's sudden appearance along their route of advance. Attacked while still entrained, the Black Army took considerable casualties and were left in considerable disarray. Pressing forward, Wrangel's men found themselves under increasingly heavy fire as the Blacks pulled themselves together and began coordinating their resistance. Across a ten-mile line, from north to south, the Black Army found itself fighting with its back to the Dnieper. Over the course of a four hour long battle, Makhno was able to hold the line until enough reinforcements could arrive from further up the rail line to push Wrangel out of his positions through a push on his right flank. He would fall back on Alexandrovsk, which came under siege soon after as a result of the Black pursuit.

The Siege of Alexandrovsk would last for two months, into April, before being broken by a Cossack relief army under the personal command of Krasnov, whose approach forced Makhno to retreat for fear of encirclement. The Vienna's Red Week and the subsequent turmoil in Hungary caused considerable unrest in Austro-Hungarian ranks and led to a major spike in desertions, causing a collapse of what little order they had been maintaining in the Ukrainian interior. While Green, White, Red, Black and Nationalist groups popped up across the region, turning it into a five-sided bloody factional struggle, the Germans slowly began to release forces from the western front, as pressure in the region fell precipitously following their Moselle Counteroffensive. Over the course of April and May, the Germans were able to extend their control ever deeper into the lawless interior of the Ukraine, eventually bumping up against the Muscovites around Fastiv, south-west of Kiev.

Romanian agitation for a thrust into the region was quelled by their occupiers in mid-May, although a discussion of whether to transfer the Odessa Oblast to Romania did come under review, while the Germans pushed ever deeper into the Ukraine. It was around this time that events elsewhere in Russia fundamentally changed the Central Powers' approach to the Ukraine. After the defeat at Alexandrovsk, Makhno had found himself forced back north to Yekatrinoslav as the threat to Kiev grew greater. Throughout this period, the Ukraine was pillaged, ravaged and ruined by every contending faction in the region. Green peasants fought Whites, Reds fought Nationalists, Blacks fought Germans. Villages were pillaged and had their grain stocks looted, thousands were killed out of hand while disease and starvation made the rounds. By the middle of 1919, as major victories and defeats were fought on other fronts, the Ukraine remained a deeply divided cauldron of conflict.

Footnotes:

(1) Without the Ice March, the Kuban Cossacks are forced to fight a guerrilla war with the Soviet Republic that was established in early 1918. With the Don Cossacks having emerged from their crisis by August 1918, they send off representatives to get aid for their losing war. The Don Whites see this as a fantastic opportunity to strengthen their power in the region and they go for it.

(2) In contrast to OTL, where the Ukraine remained pretty definitively under German occupation until the end of the war, ITTL the great demands of the western front and the resultant German reliance on Austro-Hungarians for occupation duties comes back to bite them when their positions collapse completely around them. While they are slowly going to rebuild this position, it does cause considerable troubles and creates intermittent shortages from the region.

Recruitment Poster For The Petrograd Whites Urging Men To Enlist In The Army

Moscow In The Middle

In Moscow, the pressure from all sides played out in a variety of ways. A quiet hush would fall over the populace as they heard newspaper boys declare the latest news from the front, the members of the Central Committee in Moscow met on a daily basis to debate the continued course of the conflict, poems and other forms of art took on a fatalistic but hopeful outlook, claiming that even if Moscow should fall, the workers of the world would muster to continue the fight to free labor. With the terror of the Cheka subsiding, life in Moscow took on a surreal liberated feeling that anything was possible, particularly within the Proletkult movement which grew increasingly ambitious and took on bizarre tones as these pioneers of a 'psychic revolution' pursued diverse experimental forms.

There was no censorship of art at this time and it was an area of relative freedom. However, given the youthful exuberance with which the avant-garde embraced this spirit of experimentalism, many of their contributions were often bizarre. In music, for example, there were orchestras without conductors, both in rehearsal and performance, who claimed to be pioneering the socialist way of life based on equality and human fulfilment through free collective work. There was a movement of 'concerts in the factory' using the sirens, turbines and hooters as instruments, or creating new sounds by electronic means, which some people seemed to think would lead to a new musical aesthetic closer to the psyche of the workers. Shostakovich joined in the fun by adding the sound of factory whistles to the climax of his Second Symphony, titled 'To September'. Equally eccentric was the renaming of well-known operas and their refashioning with new librettos to make them 'socialist': so Tosca became The Battle for the Commune, with the action shifted to the Paris of 1871; Les Huguenots became The Decembrists and was set in Russia; while Glinka's Life for the Tsar was rewritten as The Hammer and the Sickle.

There was a similar attempt to bring theatre closer to the masses by taking it out of its usual bourgeois setting and putting it on in the streets, the factories and the barracks. Its aim was to break down the barriers between actors and spectators, to dissolve the line dividing theatre from reality. All this was taken from the techniques of the German experimental theatre pioneered by Max Reinhardt, which were later perfected by Brecht. By encouraging the audience to voice its reactions to the drama, Meyerhold and other Communist directors sought to engage its emotions in didactic allegories of the revolution. The new dramas highlighted the revolutionary struggle both on the national scale and on the scale of private human lives. The characters were crude cardboard symbols: greedy capitalists in bowler hats, devilish priests with Rasputin-type beards and honest simple workers (3).

By early February 1919 Bubnov found himself ready to go on the offensive against Trotsky's supporters. Thus, the Moscow Reds turned their arms eastward and launched their forces forward in a bid to crush this rival claimant to Red authority. The centre point of this offensive would be an assault on Samara. This attack would run headlong into the defences constructed around the approaches to the city, situated on the western bank of the Volga, and soon turned into a bloody slog as almost 200,000 men clashed in a series of major battles. The Muscovites would make considerable progress over the course of February, reaching the right bank of the Volga, opposite Samara, on the 4th of March 1919. Here, Bubnov tried to force a crossing in the face of intense oppositions at half a dozen points, only to find himself thrown back time after time. It would be a thrust commanded by Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the action which first truly brought his name to prominence in Moscow's cafés, at Volzhkiy which succeeded in securing a bridgehead. However, when Tukhachevsky tried to push down the river towards Samara he ran into the stubborn defences commanded by Mikhail Frunze, a man who had quickly grown in Trotsky's estimation and had been given command of the fields north of Samara. These two talented commanders would clash in a series of bitter raids and skirmishes before news from other fronts forced both sides to abandon their struggle, the Muscovites retreating back across the river Volga, giving up hopes on Samara, but were now able to control the traffic up and down the river, while Trotskyite and Muscovite forces rushed in opposite directions to counter White assaults.

Following the end of the Finnish Civil War in mid-1918, Kornilov and his followers had turned their attentions to consolidating their hold on the areas around the Muscovite-controlled city of Tver. This required the crushing of the Estonian Independence Movement in a series of bloody battles across Estonia, swiftly followed by brutal repression and the execution of hundreds of nationalist figures. The key to this victory was the support of the Vozhd provided by the Baltic Germans of Estonia, who constituted an important section of the population in the region's major cities, in return for which they would secure rights similar to those enjoyed by expatriate Germans under the White regime. These included their own courts with precedence over other courts in the region, greatly expanded mandates over their Estonian neighbours, tax incentives and much more. What resistance was present in the region was crushed by September of 1918.

During this same period, Finnish and the Petrograd Whites launched several expeditions into Karelia in order to bring it to order, though Petrograd's efforts would increasingly turn elsewhere, leaving the Finns to lead the struggle and to set up administrative structures in the region. The fighting in Karelia was primarily fought between various Red factions and the disparate Karelian Tribes who found support from the Finns. Further south, in the Pskov and Novgorod Oblasts, the Petrograd Whites experienced considerably greater resistance but were eventually able to enforce their control over the region, instigating intense bouts of White Terror in response to the slightest resistance. Dozens of villages were burned to the ground and several thousand were killed in the repression. Belarus at this time came under Petrograd control, with intense fighting between the Belarusian independence movement and the Petrograd Whites consuming much of the rest of the year. Particularly notable during this period was the sudden bloody spike in Jewish pogroms in the Belarus, in response to the General Jewish Bund's support for independence. Hundreds were killed and thousands more brutalised, prompting a considerable refugee stream south and west, most finding initial refuge in the Polish, Baltic and Lithuanian puppet states set up by the Germans. Thus, by the new year, the Petrograd Whites were finally firmly in control of their territories in north-western Russia and were able to expand mass conscription to their new subjects, relying heavily on ultranationalist propaganda for recruitment and indoctrination (4).

By March of 1919, Kornilov's Great Moscow Offensive could come under way as 300,000 men attacked on a wide front centring on Tver. The resultant Battle of Tver saw the weakly held city fall rapidly to White arms, before it was subjected to terror on a mass scale, captured Red soldiers being executed out of hand while the city was plundered for the second time in a year. The fall of Tver provoked panic in Moscow and played a key role in ending the Samara Campaign, with Mikhail Tukhachevsky rushed west to take up command of the resistance. As the front lines neared Klin, barely 60 kilometres from Moscow, the Communist Party declared their capital under martial law and began to arm the populace and throw up barricades. The Battle of Klin, fought between the 14th and 18th of April 1919, with the Muscovites under the recently arrived Tukhachevsky, finally saw the White advance brought to a halt.

However, as all other fronts were stripped of forces to halt Kornilov's assault, this presented an opportunity to the Don Whites who brought their Tsaritsyn Campaign under way in early May 1919. Advancing up the Don River, Brusilov swept all opposition aside. When they finally Tsimlyanskaya, the Muscovite resistance, led by Kilment Voroshilov, began to harden. Over the course of May 1919, the Muscovite defenders would fight a brave but hopeless defence, defending and counterattacking the significantly larger White force, eventually being forced back to Tsaritsyn itself. The struggle over Tsaritsyn swung back and forth, but in the end there was little that Voroshilov or any of the other military leaders in the city could do in the face of superior numbers and leadership. On the 18th of June 1919 Tsaritsyn fell to the Don Whites, inaugurating a new period of conflict in the south (5).

With the pressure on the Moscow Reds growing, and the Siberian Whites still building up their positions to the east, Trotsky felt this to be the best opportunity he would be presented with for the destruction of the Moscow Reds, an important objective for the RSDLP as it would leave them the sole Red faction in the conflict and hopefully result in a flood of support for the Reds in Yekaterinburg. While Vasily Bluykher was given command of the war effort against the Siberian Whites, Mikhail Frunze and Trotsky turned their attentions firmly westward. Launching several assaults across the Volga, they were able to drive back the Muscovites with the capture of Syzran. Considerable efforts were focused on the city of Simbirsk next which, as the birthplace of Vladimir Lenin, held considerable significance to the Communist Party of Moscow and amongst the old Bolsheviks of the RSDLP. A crossing by riverboats was undertaken in late April 1919, with intense fighting around the city over the next several weeks. However, with the pressure on Moscow to the west holding up most of the Muscovite forces, the city fell into RSDLP hands by early June.

At the same time, an effort at crushing the Idel-Ural State of Tartars, centred on Kazan, was undertaken in preparation for a thrust on Nizhny Novgorod. This was an important effort due to the considerable grain production of the region and the threat it posed to Trotsky's control of the Urals. Over the course of April and May, pacification efforts in the region grew ever more brutal as considerable peasant and tartar resistance forced the Yekaterinburg Reds to a halt. Trotsky, not at all pleased with this result, ordered the liquidation of any resistance by counter-revolutionary Kulaks and savages culminating in the defeat of the Idel-Ural State and the public execution of its president Sadri Maksudi Arsal. The murder of Arsal would have considerable consequences for the Yekaterineburg Reds in the long run, as it deeply alienated Tartar and Turkish peoples throughout Russia and its neighbouring states against them, but served to break the back of Tartar resistance in the region.

Over the course of the summer of 1919, as the Muscovites gained access to more forces and the threat of the Siberian Whites grew exponentially, Trotsky would delegate command of the region to the young Commissar Lazar Kaganovich with the aim of turning the region into a centre of food production for the cities of the Urals. Kaganovich would set about this task with gusto, exhibiting incredible efficiency and brutality. Any and all resistance was forcefully crushed while military order was imposed on the region through a series of political commissars with absolute authority over their sector. Kaganovich's actions, while incredibly brutal, would also secure the results Trotsky was looking for - ensuring a strong and steady food supply for his starving cities during the coming conflict, though the consequences of Lazar's harsh methods would make themselves felt in the period between 1921-1922 when the region was subjected to the Great Tartar Famine (6). However, while Kaganovich was working to secure Trotsky's northern and north-western front, it would be to the east that a great threat emerged as Tsar Mikhail, his subjects and his international backers initiated their great effort in the region.

With Tsar Mikhail as their putative head of state, the Siberian Whites were able to begin forming their state structures around his figure. While Mikhail took his duties seriously, and actively sought to participate in the war effort, his wife Natalia was left to establish a court in Omsk alongside her two nieces, Anastasia and Olga. Natalia would find herself at odds with the reactionary supporters of her husband on more than one occasion due to her own belief that Tsarist autocracy must give way to constitutional monarchism. The court at Omsk was a toxic place to grow up, with countless petty intrigues, murderous power-plays and constant factional infighting, which would mark the Romanov princesses deeply. Particularly Anastasia would be deeply impacted by her time in Omsk, growing to loathe and look down on the courtiers in Omsk while finding her position, as the daughter of a martyred tsar, greatly limited in direct power and influence, forcing her to learn to defend herself and her sister from the court. Both Olga and Anastasia would spend their time in Omsk on the outside, except for the few times anyone sought to use them as a pawn in one game or another.

While allied visitors to Omsk were horrified at the fractiousness and pettiness of the Omsk royalists, they would direct considerable resources into the fighting in Siberia. In the year between the ascension to power of Kolchak under British auspices and the launching of the Siberian Offensives, the Allies had come to believe that they might be able to secure victory through a proper investment of resources into the Siberian war effort, with the ultimate aim of reestablishing an eastern front to the Great War. Thus, the British and French asked the United States to furnish troops for the Siberian Campaign, which resulted in the dispatch of some 20,000 US troops in the form of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia in July of 1918 under Major General William S. Graves. In the same month, the Beiyang government of the Republic of China accepted an invitation by the Chinese community in Russia and sent 2,000 troops in August 1918 to occupy Outer Mongolia and Tuva. Over the next months, as the Allied offensives in the west failed and the importance of reopening the eastern front grew, more and more men and resources were dedicated to the effort, with particularly the Japanese and Americans leading the effort. By May of 1919, as the western front found itself gripped by failure and disorder, there were more than 60,000 American and 80,000 Japanese troops available to compliment the 200,000 that Kolchak, as commander-in-chief for Mikhail, had been able to amass in Siberia.

The first great clashes of the Siberian Offensives first came in the thrust towards Tyumen. In a series of major bloody clashes between Omsk and Tyumen, the Reds found their 250,000 men outmanned and outgunned by the vastly superior White forces. While Bluykher was able to hold back Kolchak's initial thrust long enough for reinforcements to arrive, the Yekaterinburg Reds faced their greatest threat yet in this advance. Major battles were fought at Krutinka and Ishim before the Siberian Whites closed on Tyumen itself. Trotsky would rush to the city to help in its defense - urging on the protectors of Tyumen, while Frunze and Blyukher held actual command. The Battle of Tyumen would last for more than two-and-a-half months, from May 19th to the 8th of August, with more than 80,000 casualties, 6,000 of them from amongst the international forces, spread between the two forces, before the Reds were forced from Tyumen and back into the Urals. This brought Yekaterinburg under direct threat and prompted major concerns in RSDLP ranks, though Trotsky was able to keep morale relatively high while fortification efforts in the Urals took on ever growing rapidity (7).

Footnotes:

(3) This is actually based largely on the OTL Proletkult movement. Before they were banned, in the heady days of the early civil war, there were actually pretty broad cultural freedoms which were allowed to run wild for a while. ITTL these cultural freedoms are largely preserved for the time being due to Gorky's close relationship with Sverdlov, with the result that Moscow becomes one of the places in the world with the greatest freedom of expression. This does bother some amongst the Communist Party, but Sverdlov has sufficient heft to shield the movement.

(4) The Petrograd Whites are really not a particularly loveable regime, but then again few of the Russian regimes are particularly pleasant in this period. The Finnish campaigns into Karelia will have some interesting consequences, given the relationships the Finns are able to construct in the region. It is important to note that the British have departed Murmansk with much of their supply depots by this point, meaning they don't play any major role in the region.

(5) With the Communists fighting a life-or-death struggle for Moscow, Tsaritsyn doesn't receive the support it needs to hold out against the Don Whites. This means that the Don Whites now bestride the lower Don and Volga Rivers, with the Dnieper near at hand. This would give them an immensely strong grip on the Russian logistical network. Furthermore, the fall of Tsaritsyn means that the lands of the lower Volga are cut off from Moscow's support and are now at the mercy of the Don Whites.

(6) Lazar Kaganovich, while a monster, was one of Stalin's more capable cronies, who played a key role in the industrial miracles of the 1930s. He was absolutely murderous and a harsh task master by any standard, and participated actively in both the Holodomor and Great Purge, but he made sure that whatever task he was given was done, and often done well. ITTL Kaganovich attaches himself to the RSDLP during the chaos of 1917 and swiftly rises through the ranks, coming to Trotsky's attention during the great march east for his willingness to do anything asked of him by his master, who ITTL happens to be Trotsky.

(7) Due to the much slower buildup of Siberian White power and the considerable amount of difficult they faced in organising and securing enough supplies for the war effort, they find their positions considerably worse when they start their 1919 offensives than IOTL. However, now that they have secured Tyumen it isn't all that far to Yekaterinburg. However, the political climate in Omsk is absolutely toxic and this has its effects on the wider war effort as feuding parties have a tendency to focus on their internal struggles rather than the external threat.

Executed White Soldier

The Fight to Survive

Kornilov arrived at the front in early June of 1919, hoping to secure victory against the Muscovites and establish the Petrograd Whites as the predominant faction in Russia. With the fighting around Klin stalemated, Kornilov chose to imitate Trotsky's swing north of Moscow, leaving Denikin in command of the front at Klin while personally commanding the northern thrust, aimed at capturing Yaroslav and threatening to take Moscow from the rear. The northern thrust began on the 8th of June 1919 and placed incredible pressure on the Muscovites. Rushing forward against these weakly held positions, Kornilov was able to sweep up considerable gains before running headlong into a counterattack by the 1st Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny, a man famous for his temper and aggression, near the town of Uglich. It was here, at the Battle of Uglich, that the Communist Party and its supporters were saved in a confused and bloody two-day struggle over more than thirty square kilometers between the 22nd and 24th of June. It would take the better half of the first day of the battle before Kornilov even realized he was under attack, at which point his efforts at coordinating a response to the counterattack were all for naught.

Defeated and in disarray, the northern flank of the Petrograd Whites' assault shattered, leaving the Klin front's flanks completely open. Budyonny descended on Denikin's men before he could properly coordinate a retreat, prompting Tukhachevsky to launch forward as well. Kornilov's Moscow Offensive had been decisively defeated and the Muscovites now set about a spirited pursuit under Tukhachevsky's overall command. Budyonny would be hailed as a Defender of Communism by the Moscow Soviet and was dispatched south against the Don Whites. The collapse of Kornilov's forces and the resultant retreat was a nightmarish affair, with nearly 200,000 men lost in the rout, and it would only be upon reaching Veliky Novgorod and Lake Ilmen that Denikin and Kornilov were able to restore some semblance of order and set about rebuilding their positions, Tukhachevsky and the Communists struggling to absorb the massive lands they had secured with the victory at Uglich (8).

While there were a variety of military reasons behind the failure of Kornilov's offensive, at its heart lay the regime's inability to win the support of its subordinate population. They had been unable to muster enough support to keep their conscript army fighting and had too few talented commanders who could deal with the chaos of a sudden counterattack. At the same time, while every army of the Russian Civil War dealt with mass desertions, it was worst in the Petrograd ranks. To mobilise the peasants Kornilov's army had always resorted to terror in their recruitment. There was no effective local administration to enforce the conscription in any other way, and in any case the Petrograders' world-view ruled out the need to persuade the peasants. It was taken for granted that it was the peasants place to serve in the White army, just as he had served in the ranks of the Tsar's, and that if he refused it was the army's right to punish him, even executing him if necessary as a warning to the others. Peasants were flogged and tortured, hostages were taken and shot, and whole villages were burned to the ground to force the conscripts into the army. Kornilov's cavalry would ride into towns on market day, round up the young men at gunpoint and take them off to the Front.

Thus, it should come as little surprise that as word spread of Kornilov's defeat, all the disparate forces so deeply opposed to Kornilov's regime rose up en masse. The Petrograd regime would find itself increasingly mired in a horrific internal war as protests erupted throughout the cities under their control and peasants burned their crops rather than see them requisitioned by the army, while Muscovite troops were greeted like liberators in one town and village after another.

With Kornilov's collapse and the considerable successes of the Don Whites, the German leadership began questioning the validity of supporting the Petrograd Whites. While they remained uncertain of how to proceed, they did make an initial approach towards the leadership in Rostov in the hopes of establishing a dialogue with the more successful Whites. It was in this period that Brusilov turned his attentions south towards the Caucasus and Caspian Sea, with the hope of securing control of the major city of Astrakhan. Astrakhan lay at the heart of the Caucasian Clique of the Communist Party, a near-independent coalition of Georgian, Armenian, Circassian, Tartar and Azeri Bolsheviks who exerted near-dictatorial control of Ciscaucasia with little say or input from the Central Committee in Moscow. At the heart of this clique was the trio of Sergei Kirov, Anastas Mikoyan and Sergo Ordzhonikidze, who led the way with an iron hand. Mixing communist and pan-Caucasian nationalism, they instigated a brutal conquest of the region and steadily came to dominate the Soviets of the region (9).

During this period, the Caucasian Clique established working relationships with the RSDLP, and were able to secure relatively peaceful relations with them and their supporting factions. Following Pyotr Wrangel's victory in the Kuban, the Caucasian Clique had steadily pieced together resistance to the ascendant Don Whites. The conflict to follow, for control of Astrakhan, would prove to be among the greatest challenges experienced by Brusilov and his compatriots at the time. With the White advance beginning in early July 1919, the Caucasian Clique found itself firmly on the defensive. With the weight of the White assault on the Volga, they were able to draw heavily on the steppes to their south and particularly from amongst the large Armenian population, which had grown positively massive following Turkish atrocities to the south, in order to construct a formidable defensive force. Major battles were fought along the river, while both sides relied heavily on large cavalry forces out on the steppes on either side of the river to raid and disrupt their enemies. These clashes would slowly turn in White favor, as the steady pressure of the much larger Don Whites allowed them to overwhelm the fanatical defenders. By mid-August, the Whites had successfully taken the village of Selitrennoe, some 100 kilometers upriver from Astrakhan, and were preparing for this final push when Semyon Budyonny erupted out of the north on a rampage down the Don.

This placed the Don Whites in a considerable conundrum, to continue pressing towards Astrakhan and risk getting cut off or turn back and lose all forward progress in the region. It was at this point that Krasnov, the great Ataman of All Cossacks, as he was increasingly styling himself, came to the rescue. With the Don Whites expanding out of the regions directly relevant to his rule, Krasnov had increasingly reduced the degree of Cossack investment in the White offensives, finding it a challenge to get his men to go beyond their own lands in a time of great turmoil. However, with Budyonny rushing southward he was able to martial a major Cossack force to repel the attack. Thus, Brusilov was able to continue his push southward, though he was forced to transfer forces north to help hold the line against Budyonny, and continued to make progress in the south. This culminated on the 29th of August in a White victory at the Battle of Astrakhan after several weeks of intense clashes - forcing the Caucasian Clique and the remnants of their forces to retreat into the area north of the Caucasus. Soon after, Budyonny won a major victory over Krasnov at the Battle of Obraszty on the 8th of September 1919 which sent the Cossacks scrambling south towards Tsaritsyn and turned the conflict firmly in Red favor around Tsaritsyn. This forced Brusilov to abandon any hope of chasing the Caucasian Clique, transferring major forces back north to Tsaritsyn to hold the line against Budyonny and allowing the Caucasian Clique to dig into the steppes of Ciscaucasia.

With the capture of Tyumen in August 1919, the Siberian Whites and their Allies were able to press forward into the Ural Mountains, aiming to secure control of Yekaterinburg from the RSDLP and Trotsky. This offensive would see attacks launched at three points along the frontlines: one directly out of Tyumen aimed at securing Yekaterinburg, one out of Kurgan aimed at securing Chelyabinsk to the south and finally a thrust by the Orenburg Cossack Host under Alexander Dutov aimed at cutting into the RSDLP's soft belly from the far south, while their focus was arrested further north against the other two assaults. By late-September Kolchak's forces had advanced more than 200 miles and had captured an area larger than Britain. While they had taken Chelyabinsk and threatened to overrun the southern districts all the way to the Volga, Trotsky had been able to muster a successful defence of Yekaterinburg itself, throwing tens of thousands of soldiers and party cadres into the fighting and personally joining the fighting on multiple occasions to spur on the defenders.

However, behind their own lines the Yekaterinburg Reds were struggling to deal with the largest peasant uprising to shake Russia yet, the so-called 'War of the Chapany', named after the local peasant term for a tunic, which engulfed whole districts of Simbirsk and Samara. Kolchak and Tsar Mikhail's prestige soared among the Allies and further credit was advanced to Omsk. It seemed that Western diplomatic recognition for the Siberian Whites was just around the corner. But on the 28th of September the Reds launched a long-prepared counter-offensive under Mikhail Frunze. Thousands of party members were mobilized and dispatched to the Front. The newly organized Komsomol, the Communist Youth League, sent 3,000 of its members. The Soviets were also ordered to recruit ten to twenty conscripts from each volost. Due to the resistance of the peasants, only 13,000 recruits actually appeared, but it still helped to tip the balance against the Whites. The Reds were also joined by the majority of the Bashkir units which defected from Kolchak's side in May. By mid-October, Frunze's forces had pushed Kolchak's armies back to where they had started from around Tyumen (10).

There were a number of military reasons for the collapse of the Kolchak offensive, but behind all of them lay politics. It was a case of military overstretch, where the regime in the rear lacked the political means to sustain the army at the Front. There were very few commanders of any caliber to be found in Kolchak's army, only 5 per cent of the 17,000 officers had been trained before the war and most were young wartime ensigns. General Lebedev, the de facto head of the army, was only thirty-six and had been a colonel in the tsarist General Staff. Like most of Kolchak's senior commanders, he was more expert in political intrigues than in the sciences of war. The army leaders thought of themselves not just as a military but also as a political corps. Political factions soon developed among the commanders' supporters, with the result that the army broke up into little more than a disunited collection of separate detachments, each pursuing its own little war. The more the army became politicized, the more its bureaucracy ballooned out of all proportion to the soldiers in the field. At the height of the offensive there were 2,000 officers in the staff at Omsk alone to administer 100,000 soldiers. Even in Semipalatinsk, some 1,500 miles from the fighting, there was a staff of over 1,000. Instead of serving at the Front, far too many commanders sat around in offices and cafes in the rear.

Then there was the problem of supplies. Kolchak's army, even more so than Trotsky's, suffered from shortages at the Front. It had to resort to feeding itself from the villages near the Front, which often meant violent requisitioning, leading to the alienation of the very population the Whites were supposed to be liberating. Nothing was done to resurrect the chronic state of Siberia's industries: they were simply written off as a bastion of Bolshevik influence while consumer goods and military supplies had to be brought in by rail from the Pacific, 4,000 miles away, much of which was held up by bandits east of Lake Baikal, or by peasant partisans. Whole trainloads were also diverted by the railway workers, many of whom were sympathetic to the Reds and all of whom were badly paid. In Omsk itself valuable supplies were often squandered by corrupt officials. The venality of White regime in Omsk was notorious, with the staff of Gajda's army drawing rations for 275,000 men, when there were only 30,000 in his combat units and the Embassy cigarettes imported from England for the soldiers being smoked by civilians in Omsk. English army uniforms and nurses' outfits were worn by civilians, while many soldiers dressed in rags. Even Allied munitions were sold on the black market. The British representative to Tsar Mikhail and Kolchak, Knox, was dubbed the Quartermaster General of the Red Army: Trotsky even sent him a joke letter thanking him for his help in equipping the Red troops (11).

The atmosphere of the Omsk regime was filled with moral decadence and seedy corruption, which the Tsar and his cohorts could do little to fix, Kolchak increasingly having sidelined his putative monarch to Mikhail's great despair. This was the beginning of the Tsar's slide into drugged and intoxicated paranoia as his closest and most loyal supporters, many of whom had followed him from Novocherkassk, seemed to either find their way quite suddenly to the frontlines or were killed in bizarre back alley robberies. Cocaine and vodka were consumed in prodigious quantities across Omsk. Cafes, casinos and brothels worked around the clock. Kolchak himself led by example, living with his mistress in luxury in Omsk while his wife and son were packed off to Paris. The Admiral had no talent for choosing subordinates and filled his ministries with third-rate hangers-on from the old regime. Baron Nikolai von Budberg-Bönningshausen was appalled by the situation he found as Minister of War: "In the army, decay; in the Staff, ignorance and incompetence; in the Government, moral rot, divisions and the intrigues of ambitious egotists; in the country, uprising and anarchy; in public life, panic, selfishness, bribes and scoundrelism of every sort." In such a climate little could be achieved. The offices responsible for supply were full of corrupt and indolent bureaucrats, who took months to draw up meaningless statistics, legislative projects and official reports that were then filed away and forgotten.

The worst weakness of this regime, and one shared with the Petrograd Regime, was their inability to muster the support of the peasantry. The Tsarist regime was associated with a restoration of the wider tsarist system. This was communicated by the epaulettes of the officers; and by the tsarist and feudal methods employed by his local officials, who often whipped the peasants when they disobeyed their orders - and most clearly by the fact that they had crowned a Tsar, no matter how powerless he had grown. This was bound to bring them into head-on conflict with the Siberian peasantry, whose ancestors had run away from serfdom in Russia and the Ukraine and whose identity revolved around freedom and independence. The whole ethos of the Kolchak regime was alien to the peasants, a feeling expressed in the peasant rhyming song: "English tunics, Russian epaulettes; Japanese tobacco, Omsk despots." The closer the Whites moved towards central Russia, the harder it became for them to mobilise the local peasantry.

In the crucial Volga region, the furthest point of Kolchak's advance in the south, the peasants had gained more of the gentry's land than anywhere else in Russia and so had most to fear from a counter-revolution. Here Kolchak dug his own grave by failing to sanction the peasant revolution on the land. Kolchak's government was quite incapable of anything more than a carefully guarded bureaucratic response to what was the vital issue of the civil war. It was a classic example of the outdated methods of the Siberian Whites. "Any future land law", Kolchak's land commission declared on 8th August, would "have to be based on the rights of private property". Only the 'unused land of the gentry' would be 'transferred to the toiling peasantry', which in the meantime could do no more than rent it from the government. With Kolchak's forces increasingly resorting to terror as a recruiting mechanism, they soon found themselves in trouble with their Allies. General Graves, the commander of the US troops, was well informed and was horrified by it. As he realized, the mass conscription of the peasantry "was a long step towards the end of Tsarist regime in Omsk". It soon destroyed the discipline and fighting morale of his army. Of every five peasants forcibly conscripted, four would desert, many of them ran off to the Reds, taking with them their supplies. Major General Knox was livid when he first saw the Red troops on the Eastern Front - they were wearing British uniforms.

From the start of its campaign, Kolchak's army was forced to deal with numerous peasant revolts in the rear, notably in Slavgorod, south-east of Omsk, and in Minusinsk on the Yenisei. The White requisitioning and mobilizations were their principal cause. Without its own structures of local government in the rural areas, Kolchak's regime could do very little, other than send in the Cossacks with their whips, to stop the peasants from reforming their Soviets to defend the local village revolution. By the height of the Kolchak offensive, whole areas of the Siberian rear were engulfed by peasant revolts. This partisan movement could not really be described as socialist or communist, although Bolshevik and RSDLP activists, usually in a united front with the Anarchists and Left SRs, often played a major role in it. It was rather a vast peasant war against the Omsk regime (11).

Footnotes:

(8) While Budyonny never quite got past his glory days during the Civil War IOTL and as such proved himself an absolute disaster in later conflicts, during the civil war he was one of the most aggressive cavalry commanders of the entire war and was able to win several major victories on the back of this aggression. Here he does exactly that, attacking suddenly against a distracted enemy and completely overrunning their positions. The collapse that follows is the logical conclusion to these events.

(9) This is the Clique that eventually became the foundation for Stalin's rise to power IOTL. They are still present and the clannish tendencies of the Caucasians in a Russian context means that they still band together. However, without Stalin to push their interests in the Central Committee, they are far less powerful and disconnected from the Centre. This means that while they hold an incredible grip on power in the region, they don't have much, if any, influence outside it and don't really play a major part in the Central Committee's deliberations.

(10) Kolchak's great offensives play out pretty closely to OTL, though here Trotsky is able to hold the line at Yekaterinburg with considerable success. The slower buildup also means that they never really secure control of the Ural Cities north of Yekaterinburg and the Reds are in a position to push the Whites back.

(11) This is basically based on what the Omsk regime was like IOTL. There are a couple key differences, such as the presence of an actual Tsar making it more difficult for them to not argue that they are tsarists in their propaganda. However, Mikhail does have some positive impact in the period leading up to the capture of Tyumen, after that point he rapidly loses actual power and authority as Kolchak and his cronies take up leadership. Mikhail and his family are placed under close guard and largely muffled, with Mikhail descending into despair and drug addiction as the war turns sour and he grows to regret staying in Russia.

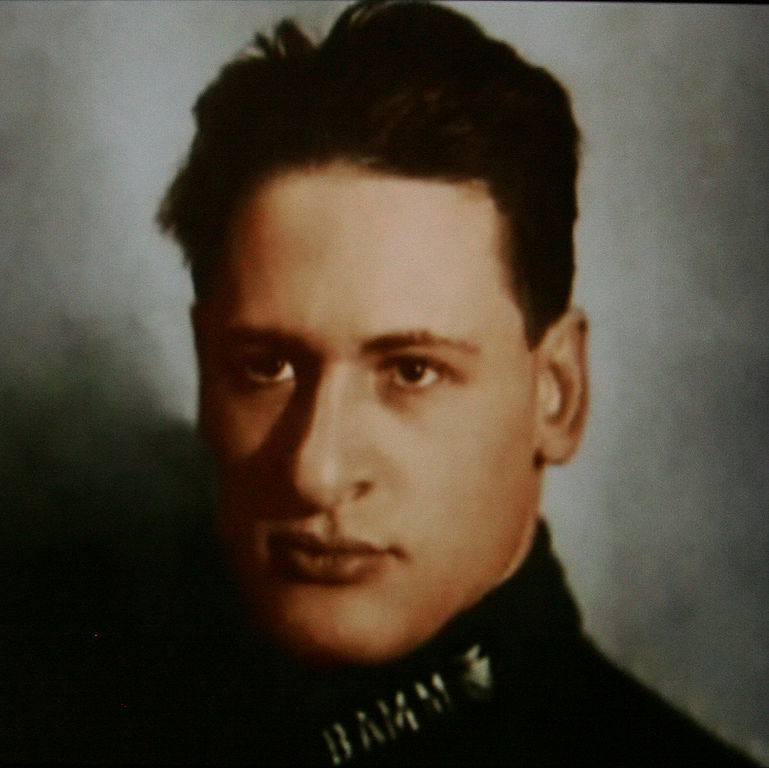

Mikhail Tukhachevsky Urging On His Men Outside Petrograd

A Crisis of Leadership

The collapse of Kornilov's offensive against Moscow and the resultant chaos caused considerable infighting in the Petrograd leadership group. Particularly Denikin was absolutely furious at Kornilov and blamed him squarely for the failed offensive, citing his own suggestions that once the assault on Klin failed it would be better to retreat to a more sustainable line at Tver to rebuild White strength before making another attempt on Moscow. Instead, Kornilov had gambled everything in an ambitious but ill thought-out thrust into the north which had left Denikin's forces weak and Kornilov's spread out and uncoordinated when Budyonny attacked. Krymov, having largely been charged with securing order behind the lines, was blamed by Kornilov for the failure, primarily stemming from the Vozhd's belief that his northern thrust had been betrayed by spies amongst the peasantry. Savinkov, ever more angered and frustrated at the incompetence of his fellows, looked increasingly for an escape and began siphoning huge sums out of Petrograd's treasury and banks to safety in secret German and Swiss bank accounts.

The collapse of the White army had also resulted in a flood of disaffected deserters who took to the forests and hid in villages across Petrograd-governed lands, making the lives of the loyalists to the Vozhd ever more difficult. The sheer savagery of the repression Kornilov unleashed in order to crush this resistance would shock even other White factions. Deserters were captured and shot by the thousands, anyone found to have aided them were either killed or mutilated and any hint of disloyalty was punished with death. Tens of thousands fled the cities for safety in the countryside where they joined the growing Green armies, which Kornilov's ever shrinking armies found themselves hard pressed to defeat. It was as Kornilov began this tailspin into mad tyranny, that the Germans decided to cut their losses. With considerably more men available following the quiet on the western Front, the Germans marched into Estonia and Belarus nearly unopposed, crushing what small resistance they encountered in Estonia, but running into considerably greater opposition in Belarus. This would ultimately result in the German decision to pull out of the region after two weeks of fighting insurgent Green and Red forces, redirecting them south to the Ukraine.

Panic gripped Petrograd, but there was little they could do against their former patrons nor against their putative Finn allies, who now claimed Karelia and the Kola Peninsula as their own alongside their Karelian allies. It was at this point that the Don Whites, following secret negotiations with the Germans, repudiated their ties to the Allies and declared formally in favor of a German alliance. The negotiations, largely completed in secret already, led to the signing of the Treaty of Odessa on the 13th of September 1919. This treaty would see the transfer of German and Austro-Hungarian occupied Ukraine to Don White control in return for Brusilov's acknowledgement of the border adjustments set forth by the Central Powers in the Treaty of the Tauride: reiterating Georgian independence and the Turkish conquests in the Caucasus, the independence of Poland and of the United Baltic Duchies, now to include Estonia, while the Central Powers promised to transfer the parts of Ukraine under their occupation to White control as soon as it became practical while promising considerable military aid in return for major trade concessions (12).

This shift in allegiances by the Don Whites to German patronage would prove to be one of the most important decisions taken by Brusilov during the Civil War. While it would take time for Pyotr Wrangel to extend sufficient control over Central Powers-occupied Ukraine, the sudden influx of arms, German military advisors, Freikorps volunteers, rapidly expanded trade networks throughout the Black Sea and much more would have a profound impact on the Don Whites. German forces advanced out of the Crimea to support Wrangel's pacification campaign across southern Ukraine while Brusilov received invaluable reinforcements at the height of the clash with Budyonny. The Second Battle of Tsaritsyn, fought over the course of three months, well into winter, would see major armed clashes in the lands between the Volga and Don. With Budyonny's assault slowed and the threat to Moscow largely ended, the Muscovites secured considerable growth in their available forces resulting in a major slugging match between these two factions of the civil war. Attack was met by counterattack, rapid movement and sudden cavalry charges dominated the fighting and the balance of power during the battle swung back and forth half a dozen times before the arrival of a shipment of light German tanks, 60 in total, took the Muscovites by surprise and sent them into retreat.

Don White control of Tsaritsyn had been firmly secured and so had the importance of the German alliance. Over the course of the winter, the positions of the Caucasian Clique would find themselves steadily degraded as Georgian, German, Cossack and Don White forces put pressure on them from all sides. By February 1920 the Clique fled across the Caspian Sea with what remnants of their supporters they could save and took up with the Basmachi movement in Kokand - providing all the aid they could to the movement in the region and creating connections to the exilic Armenian population across the region (13). While all this was occurring in the Caucasus, the main theatre of war shifted back west to the Ukraine as Brusilov returned to Rostov-on-Don. With German aid, General Wrangel was suddenly able to vastly strengthen his positions against Nestor Makhno, who was now forced to return to the sort of defensive guerrilla warfare that had first led resulted in his to fame, while the Muscovites desperately sought to end the Petrograd Whites. With the Don White's extension of power across much of southern Ukraine over the last months of 1919 and early 1920, these clashes would largely remain stalemated as both sides steadily grew in power, the Don Whites from their German alliance as well as the securing of most of the Ukraine and the Moscow Reds from their major successes further to the north towards Petrograd.

Having spent two months absorbing the gains from the victory at Uglich in late June, Mikhail Tukhachevsky was ready to begin what was believed to be the knock-out blow to the Petrograd Whites that they had been dreaming of for the last year. Advancing on a broad line along the rail lines leading to Petrograd, with plentiful Cavalry and even some armoured vehicle support, Tukhachevsky's force was the strongest yet fielded by the Moscow Reds. With the Petrograd Whites already in considerable disarray, this assault served a sledgehammer, slamming through their weak and confused defences with little difficulty. The press forward would see the Petrograd Whites begin to collapse in on themselves, their men deserting by the tens of thousands and seeking safety in the countryside, where they either joined the Green armies or became victims of them.

As panic gripped Petrograd, Savinkov grabbed what he could carry and abandoned the city, sailing for Stockholm, where he would stay until the shipping lanes to the United States opened up and he could set sail for New York. Savinkov's betrayal caught Kornilov by surprise and prompted a great deal of paranoia in the Vozhd, which quickly erupted when spies in Krymov's retinue revealed the general's plans to escape to German-held lands. Acting quickly, Kornilov surprised Krymov and had him arrested, tortured and summarily executed. With the frontlines growing ever closer to Petrograd, the rats rushed to abandon the ship and Kornilov with it. Kornilov was swift to respond, placing his own generals under guard by his bodyguards and cracking down harshly on Petrograd and the surroundings. In the meanwhile, Denikin, who had been given the thankless task of holding the line against Tukhachevsky, found himself under ever greater pressure as his men deserted in droves. Convinced that defeat was certain, Denikin martialed what forces he could and fought a last stand at Tarasovo. Despite two hours of heroic resistance, the Whites crumpled completely and Denikin was gravely wounded. He would be discovered amongst the wounded by Red Guards and was brought before Tukhachevsky, who ordered his execution. Anton Denikin, General in the Russian Tsar's army, Kornilov's second-in-command and his presumed successor, was shot dead at the age of 46 by a firing squad compromising seven Moscow workers on the 8th of September 1919.

With Denikin died any hope of Petrograd recovering from this blow and the Petrograd White army scattered to the winds. Tukhachevsky, on the verge of securing Petrograd, stopped for a day to give his men time to recover and to awaken their awareness to the magnitude of their victory before beginning the final march on Petrograd. In the meanwhile, Kornilov spun out over the course of the week between the Red arrival on the outskirts of Petrograd and Denikin's death. Executing anyone he suspected of treason, he instituted a reign of terror to mute all that had come before it, before his own paranoia turned him against members of his own bodyguard and retinue. Finally, as Tukhachevsky's men were entering Petrograd's suburbs, Kornilov's bodyguard turned on him. Having just awoken, Kornilov was taking his breakfast in the Winter Palace when a bodyguard stabbed him from behind. Crying out, Kornilov called for aid only to have the responding guards join in the assassination (14).

By the time Tukhachevsky arrived at the Winter Palace, it was abandoned, stripped of value by the former Vozdh's bodyguards and Kornilov left dead across his dining table. The capture of Petrograd was a moment of triumph for the Communist Party and the Central Committee was swift to vote numerous honours to the victorious general, including the singular honour of Defender of Communism he would share with Budyonny. Tukhachevsky would spend the rest of the year and the early months of the next skirmishing with the Germans, breaking or assimilating Green armies and securing control of north-western Russia and Belarus, though Petrograd itself remained under considerable threat from the Finns to the north and the Germans to the west, while his gaze turned slowly southward.

As the Siberian Whites struggled back under immense pressure, they began to steadily give way. The partisans' destruction of miles of track and their constant ambushes of trains virtually halted the transportation of vital supplies along the Trans-Siberian Railway to Kolchak's armies for much of the offensive. Thousands of his soldiers had to be withdrawn from the Front against the Reds to deal with the partisans. They waged a ruthless war of terror, shooting hundreds of hostages and setting fire to dozens of villages in the partisan strongholds of Kansk and Achinsk, where the wooded and hilly terrain was perfect for holding up trains. This partly succeeded in pushing the insurgents away from the railway, but since the terror was also unleashed on villages unconnected with the partisans, it merely fanned the flames of peasant war.

As Kolchak's army retreated eastwards, it found itself increasingly surrounded by hostile peasant partisans. Mutinies began to spread as the Whites came under fire from all sides as even the Cossacks joined them. Whole units of Kolchak's peasant conscripts deserted as the retreat brought them closer to their native regions. By January 1920, Kolchak's army was falling apart. Once again the Whites had been defeated by the gulf between themselves and the peasantry. On the 14th of January 1920, Omsk was abandoned by the Tsarist forces as the Reds, who now outnumbered them by two to one, advanced eastwards. It was a classic case of White incompetence, with the leading generals caught in two minds as to whether to defend the town or evacuate it, and in the end doing neither properly. Realising that their local allies were starting to fracture, General Graves gave the order for an American abandonment of Omsk, sheltering as many refugees as they could while they pulled back through the horrific cold of the Siberian winter.

In Omsk the situation was rapidly deteriorating, with the Tsarist court splintering and many fleeing alongside the Americans, while Tsar Mikhail began preparing for the trip eastward alongside his family as he sank ever further into the bottle, rarely appearing anything other than drunk and melancholy, waxing poetically on the doom of his family and the curse of God. The royal family finally made their escape on the 10th of January, with the Reds nipping at their heels. The Reds took the city without a fight, capturing vast stores of munitions that the Whites had not had time to destroy, along with 30,000 troops. Thousands of officers and their families, clerks and officials, merchants, cafe owners, bankers and prostitutes fled the White capital and headed east. The lucky ones travelled by train, the unlucky ones by horse or on foot. The bourgeoisie were on the run. The wounded and the sick, whose numbers were swollen by a typhus epidemic, had to be abandoned on the way. This was not just a military collapse; it was also a moral one.

The retreating Cossacks carried with them huge supplies of vodka and, as all authority disappeared, indulged themselves in mass rape and pillage of the villages and refugee caravans along their way. Kolchak headed towards his new intended capital in Irkutsk, 1,500 miles east of Omsk, while Mikhail aimed to quite simply escape Siberia alive with his family. However, on the route east, Kolchak's train came under attack by peasant forces, who overran the train and began butchering everyone they had captured out of hand. It was in this massacre that Kolchak was killed alongside his mistress and half a dozen retainers. The royal family had been a bit more successful, but on arriving in Irkutsk their train was mobbed by enraged refugees and soldiers, who broke into their train and captured Mikhail, his hated wife Natalia and their two sons, the Prince George and young prince Nikolai, a child born during the height of the fighting in late 1919. Over the course of several hours all four were beaten, humiliated and murdered by their one-time supporters, enraged at the Tsar's failure to provide victory. Anastasia, at a dinner with General Graves when the attack occurred, was able to secure shelter with the Americans, eventually securing transport to the United States, while Olga Romanova, who had been on the train when the mob attacked, disappeared in the chaos of Irkutsk, her whereabout and condition unknown (15).

Footnotes:

(12) The change in Don White allegiance will have considerable consequences but has hopefully been foreshadowed enough to not come as a complete surprise to people. The Don Cossacks were already in league with the Germans and the alliance with the Allies has proven an ever greater stumbling block for Don White success given the way it cuts them off to trade through the Black Sea. We will examine the implications of this sudden change in allegiances to the wider Great War at a later point, but suffice to say it causes considerable trouble particularly since it leaves the Allies with only one faction in play in the civil war.

(13) How important the Caucasian Clique will remain is something of a question, but they have succeeded in building a pretty important network of pan-Caucasian socialists, including amongst the Armenian exilic community, which will prove important as the Armenians spread further and begin to exert influence.

(14) The Petrograd regime ends as it started, a totalitarian military dictatorship made up of a bunch of opportunists. Savinkov escapes with considerable wealth and prestige, his handling of the governance in Petrograd largely being viewed as having been relatively successful, but is also hated by Whites of the Petrograd persuasions. Krymov had a thankless job and actually dies in a worse way than IOTL where he committed suicide following the failure of the Kornilov Affair. Denikin meanwhile gets the stubborn hero's farewell, half a dozen bullets, while Kornilov goes Mad King on Petrograd. Given what we know about all these people, is it really a surprise that it ends like this?

(15) Thus ends the Kolchak-aligned Siberian Whites. A lot of this is based on OTL, though the Siberian White positions crumble somewhat quicker than IOTL. While the Mikhail-oriented iteration of the Siberian Whites have been crushed and we are now left with just one major White faction and two Red factions, there is still plenty more to come in the region. The Americans and Japanese are investing considerable resources in securing the Transbaikal and the Yekaterinburg Reds have a lot of land to occupy, much of it held by fiercely independent peasants who aren't particularly pleased with the Reds.

Summary:

The Occupying Central Powers, Ukrainian Hetmanate, Moscow Red and Don Whites all contest control of the Ukraine in a massive and bloody free-for-all, growing particularly bitter following the defeat and collapse of the Hetmanate.

Moscow is threatened from multiple directions, but is able to hold the line until the Trotskyites find themselves distracted with the Siberian Whites.

Kornilov's offensive collapses, as does the Kolchak offensives, while the Don Whites make progress around the Volga.

The Don Whites secure an alliance with the Germans while the Petrograd and Siberian Whites both collapse, with their leaders killed and their supporters scattered.

End Note:

Thus we bring the first round of the Russian Civil War to an end with the destruction of the Petrograd and Siberian Whites, leaving only the Don Whites to represent their cause for the time being. That said, there are still plenty of counter-revolutionary forces scattered across Siberia and they could well rebuild their positions given sufficient time, but for now our initial grouping of five major factions have been reduced to three.

Last edited: