A Theory of Great Men

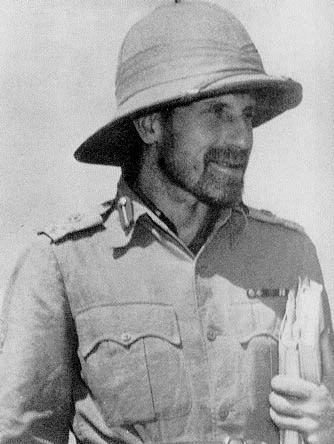

Leon Trotsky and Leonid Serebryakov Attending The Congress of Soviets

The Rise of Trotsky

The Fall of Siberia and formal unification of the Russian Communists under the banner of the Soviet Republic of Russia were to augur a time of peace and prosperity for the youthful Russian state. The horrific devastation of the Great War and the bitter Civil War had left their marks, but a renewed dedication to the revolution and ability of the government to finally turn its attentions fully towards creating a revolutionary state were to dominate the period to follow. At the very heart of the growing prosperity of Red Russia sat Grigori Sokolnikov, Member of the Central Committee, Commissar for Finance, Economic Development and Industrialization and Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy.

Under Sokolnikov's leadership, a syndicalist economy initially structured around managing the transfer of goods between the countryside and urban industry had become a sprawling system of communally- and state-owned corporations in a closely regulated market complemented by small private shops and enterprises, which were permitted as long as they remained of limited size, but were forcibly communalised amongst their workers and local governments if they grew too large, with the original owner maintaining a larger stake than others in the community and often continuing as managers of the enterprise. Industries judged as vital to the state, such as raw resource extraction, military production, utilities, healthcare, communications and public transportation were nationalised, Sokolnikov viewing them as either too important or too inelastic to permit private involvement. However, the vast majority of sectors were opened up to communal enterprise - with villages, neighborhoods, towns and workers' collectives being permitted to enter into a closely regulated market economy, in effect creating a decentralised mixed-economy. Limited foreign investments were permitted - although never exceeding 33% ownership, as was investment by the Commissariat of Economic Development, but profits collected by the Commissariat through such investments were split with half going to the state budget and the other half being used to finance further investments. Sokolnikov put a strong emphasis on the improvement of agriculture, to the point that he had his close political ally Valerian Oboloensky-Osinsky appointed as Commissar for Agriculture and implemented an incentive system through that Commissariat whereby agricultural production was incentivised with the provision of consumer goods (1).

Although the economic policies of Sokolnikov proved largely successful, and saw the development of a rapidly growing economy, these policies also met with considerable critique in government circles. When Trotsky entered the Central Committee he soon found himself at loggerheads with Sokolnikov, dismissing the economic policies as "Capitalism Painted Red", and drumming up an opposition to the policies both in the Central Committee and amongst the lower rungs of the Communist Party, claiming that a directed economy, which would ensure equal prosperity for all, would better fit the goals of the Soviet Republic. However, it was here that Sokolnikov's efforts to incorporate Syndicalist and Anarchist approaches to the economy proved beneficial. Having worked in close coordination with Makhno as Russian farms were bound together into collectives, which functioned as communal economic entities in Sokolnikov's economy, and having thereby been able to ease the on-going collectivization process, the pair had developed a good working relationship and a degree of mutual respect which made Trotsky's efforts to insert himself into these matters more challenging. However, the inclusion of Lev Kamenev and Lazar Kaganovich, the latter of whom had demonstrated an impressive capacity for industrial development, to the Central Committee following the Fall of Siberia was to present a major challenge to Sokolnikov's power and authority over the economy.

Under Trotsky's constant and relentless attacks, Sokolnikov gradually found himself pressed into a position of having to choose what parts of his authority he was willing to surrender to Kaganovich, Trotsky having argued successfully that the industrial development of the Yekaterinburg region had outstripped that of Moscow under Kaganovich's leadership. While Sokolnikov was able to coordinate with Osinsky and Makhno to ward off attacks on control of Commissariat of Agriculture, even succeeding in extending their authority to include the massive state-run and owned forcibly collectivized farms in the Yekaterinburg region, he was unable to maintain his control over the Commissariat of Industry, which managed the state-controlled sections of the economy, and was pressed to surrender three out of eight seats on the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy to Kaganovich, Trotsky and another Trotsky-ally, Gleb Krzhizhanovsky in early 1931. It was only with a great deal of effort, and the backing of Bukharin, that Sokolnikov was able to secure the transfer of regulatory oversight of both the privatized and public economy from the Commissariat of Industry to the Commissariat of Finance, allowing him to maintain control of that aspect of the economy. While control of the economy remained beyond Trotsky's grip, he had succeeded in significantly weakening Sokolnikov, his most vocal opponent on the Central Committee, and had weakened the once hegemonic power he had exerted over the economy in the process (2).

While Trotsky's conflict with Sokolnikov was to prove significant, it would be his bitter and extended conflict with the ideological leader of the Muscovite Revolution, Nikolai Bukharin, which defined the period following the Fall of Siberia. While Yakov Sverdlov had been the administrative leader of the Muscovite, and later Soviet, State he had distanced himself from the work of formulating the ideological underpinnings on which the state was built and instead allowed the more ideologically-inclined Bukharin to take the lead on these matters. To accomplish this Bukharin was named Editor-in-Chief of Pravda, the Communist Party's newspaper, and Izvetia, the official state newspaper, was made the Commissar of Communications as well as the Chairman of the Congress of Soviets and Chairman for the State Planning Committee - which directed the ideological underpinning of the state and the determined the authority and responsibilities of every department, commissariat, committee and council in the sprawling Soviet state. This placed Bukharin in control of the voice of the government and party, through his control of the newspapers, in command of the legislature and in control of what remit each state institutions was provided with. With this control, Bukharin and his supporters, most prominently Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, Vladimir Smirnov, Timofei Sparonov and Georgy Pyatkov, would formulate the Muscovite line of Communist thought which emerged as the dominant Communist ideology in the years preceding the Fall of Siberia. Muscovite Communism as developed under Bukharin placed an emphasis on collective leadership, the inclusion of divergent strains of leftist thought in ideological development and government, sought to justify the social-market economic policies of Sokolnikov, placed an emphasis on cultural promotion which under the guidance of Anatoly Lunacharsky saw Proletkult emerge as a major cultural movement on a global scale, laid a focus on the development of a truly Communist state as a precondition to the international revolution and emphasized support for the peaceful development of Communism on an international level alongside engagement with the international community on an equal footing (3).

Trotsky, with his militaristic command Communism, perpetual revolution theory and goal of spreading revolution on a global scale in any way possible, clashed openly with the strain of thought Bukharin had formulated. While initially unwilling to make too great waves, Trotsky soon began to push elements of his own beliefs, seeking to not only convince elements of the government of the feasibility and necessity of spurring on revolutionary zeal around the world but also pressing for a harder line against the imperialist powers and for unity of purpose in a government riven by factionalism. In spite of his persuasiveness, Trotsky was initially unable to make much headway in the face of Bukharin's control of the ideological organs of the state, frequently seeing his articles cut down in the editing process and placed in inopportune parts of the newspapers and magazines of the Muscovite press, but this was to change with the Fall of Siberia.

By taking actions circumventing the authority of the Central Committee and forcing them to acquiesce with his goals afterwards, he was able to secure a chance at glory, to prove that his ideas were right and those of Bukharin were wrong, and he could not have experienced greater success from such efforts. The bloody conquest of Siberia was the single greatest accomplishment of the Soviet Republic since the defeat of the Petrograd Whites and catapulted Trotsky to immense popularity both amongst the general populace and within the party and government structures themselves. His assertive personality and successful leadership of the Yekaterinburg Reds, as well as his domineering ideological beliefs and successful demonstration of a perpetually spreading constant state of revolution proved a winning combination, drawing many into support of the renegade Central Committee member.

Beginning in 1929, Trotsky would increasingly muscle his way into Bukharin's sphere of influence. In June he supported the launch of Trud, Labour, as a national newspaper, it having previously been the party newspaper of the Yekaterinburg Reds, of which he served as Editor-in-Chief and presented his views on ideological matters through this medium. Trud proved an immediate hit, soon reaching a circulation comparable to Pravda and exceeding that of Izvetia. He next used his seat in the Congress of Soviets to agitate in favor of his pet projects, whipping up the delegates in numerous displays of his incredible talent for speechifying and rallying people to his cause, turning what had previously been a relatively sedate and weak institution into the center of Russian politics in a campaign to raise the political influence of the chamber, campaigning to secure oversight responsibilities for the various committees of the Congress in order to, as Trotsky put it, "Provide a backstop on the Tyranny of the Few", although this campaign would meet with considerable opposition and while it eventually saw the Congress' authority expanded to allow the congress to sign off on the governmental budgets, he was unable to accomplish the more structural shifts he had been hoping for. While he tried to secure a seat on the State Planning Committee, he would find himself firmly rebuffed, as the collective Central Committee moved in opposition to his attempts at securing power over this vitally important state organ(4).

The person most put out by Trotsky's glory hogging in the aftermath of the Fall of Siberia was Mikhail Tukhachevsky. As a Central Committee Member, Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Militaries, Lead Army Reformer and director of the actual military campaign in Siberia, Tukhachevsky had fully expected to reap a considerable boost to his already significant popularity with the successful conquest of Siberia. However, while he was obliquely praised for his leadership, in the eyes of the populace the genius behind the campaign was not Tukhachevsky but rather Trotsky, who himself enjoyed a decent military reputation. Even within the military, Tukhachevsky found himself outshone by his subordinates. It was not the sweeping grand strategy which made its mark on the populace and dominated media and propaganda, but rather the daring North Siberian March of Blyukher, the heroic charge of Zhukov and his armored columns at Kansk and the grueling pursuit led by Rokossovsky. It was the bravery of the Communist cavalry under August Kork and the steadfast implacable courage of the infantry soldier in the face of the enigmatic genius of Kutepov.

As other benefitted from his hard work, Tukhachevsky could do little but bitterly complain and lament his mistaken trust in Trotsky, who he had viewed as a useful counterpart with whom he could work in concert. However, Tukhachevsky took his dissatisfaction and channeled it into ensuring that the military learned all that it could on the basis of the Siberian Campaign. There had been numerous mistakes and miscalculations, as well as a failure to integrate the different military doctrines which had emerged in the years following the end of the Civil War. These failures were to reflect poorly upon Tukhachevsky, and would result in the strengthening of other voices in the military to serve as a counterpoint to the once all-powerful military leader. While he had worked with Mikhail Frunze in the past, it had always been from a position of superiority, but following the end of the campaign, there would follow a major reshuffling of responsibilities within the military which was to severely constrain Tukhachevsky's power and influence.

The Military Reforms of 1930 saw the military placed under the authority of the Supreme Military Soviet, under which the Commissariats of the Army, Marine, Air, Strategy and Security & Intelligence were to be placed. Tukhachevsky saw his position raised to Chairman of the Supreme Military Council and Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Armed Forces, but in effect lost direct control over the armed forces, finding himself forced to rely upon the various Commissars who took up effective leadership of their individual branches and who had their own factional allegiances. Vasily Blyukher was named as Commissar of the Red Army for his accomplishments in the Siberian Campaign, in effect securing managerial control over the entirety of the Soviet Red Army, while Aleksandr Vladimirovich Razvozov was named as Commissar of the Red Marine, having been amongst the most prominent naval commanders in Muscovite service since the start of the Russian Civil War and having held command of the Baltic Fleet for nearly a decade, and Andrei Vasilievich Sergeev, an early organizer of Muscovite air forces during the Civil War, was named as Commissar of the Red Air Fleet. As head of the Commissariat of Military Security and Intelligence Sergey Ivanovich Gusev was appointed, having long been involved in both intelligence work around the world as a diplomat, most significantly in the United States, however while his qualifications were unquestionable more than a few would whisper about the fact that Gusev's daughter happened to serve as Sverdlov's long-time personal secretary and through that connection had developed a close relationship with the august head of state. However, while Tukhachevsky might have been able to accept the development of these Commissariats, it would be the Commissariat of Strategy which truly stuck in his craw. Under the new reorganization, Tukhachevsky's pet-project of military reform was passed over to this new Commissariat which was charged with not only developing military strategy and doctrine, as well as planning and managing the implementation of military reforms, it was also put in charge of the development of military technologies, procurement and military education, with Tukhachevsky's greatest rival, Mikhail Frunze, placed as Commissar with the charge of unifying Soviet military doctrine (5).

While Trotsky had proven himself willing to interfere in the power and authority exercised by most of the Central Committee's members, there was one person who Trotsky would maintain a constant fearful respect of - Yakov Sverdlov. Sverdlov was without a doubt the most powerful man in Russia, even if he rarely exercised that power and authority in public, preferring to maintain an air of impartiality which made him an ideal arbitrator in the often fierce factional conflicts of the Central Committee. However, appearances rarely matched reality in the case of Sverdlov, whose carefully selected positions provided him a position from which he could remove any threat to the Soviet Republic. A man of scholarly mien and few words in public, he was a superb organizer with an often astonishing knowledge of the work conducted by even the smallest of provincial committees and departments. He was a dedicated proponent of systemic and regularized solutions to party and state problems, creating a comprehensive organizational network atop which Bukharin painted his ideology. He served as confidante to many prominent political figures, most assuming that he already knew most of their secrets, and was willing to provide advice on numerous different topics, thereby exerting an often astonishing level of influence over the state.

As General Secretary of the Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Sverdlov held a level of power and authority over the party proper that not even Bukharin could match, even if Sverdlov preferred to pass off such tasks to Bukharin and simply inserted himself into the party processes when he felt a need to, maintaining a seat on the State Planning Committee and the State Finance Committee most significantly. As Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Republic, he sat at the head of the executive branch of government while as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars he held authority over and the ability to interfere in any Commissariat should he wish to, although once again this was a relatively rare occurrence. It was this unwillingness to interfere to any significant degree in the plans of other members of the Central Committee which allowed him to maintain this incredible level of power and authority, and led to him being viewed with great trust even by the rivalling Trotskyite, Militarist and Anarchist factions of the Central Committee. However, where Sverdlov truly exercised his power and control was as Commissar of Internal Affairs a position which granted him control over the vast security apparatus which maintained the safety of the state internally and held a toehold in every other part of the state, and as General Secretary of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, a position which allowed him total oversight over foreign affairs while leaving the actual diplomatic work to others.

While the Cheka had held sway as the chosen secret police force under Dzerzhinsky, with the appointment of Moisei Uritsky to head the organization, Sverdlov used the opportunity to secure effective control of the organization while splitting it into two directorates. The first, The State Security Directorate, abbreviated as the GBU, was headed by the careful and capable Uritsky and was charged with matters of general state security, including control of the Militsiya police forces, which had emerged to replace the Tsarist police force, controlled emergency services, managed the general prison population and provided for border security and internal security - providing guards to various state institutions, bodyguards to Commissars and other important government officials and protection for various state secrets. The more secretive elements of the work previously done by the Cheka were to be found in the second of these directorates, The State Political Directorate, abbreviated as the GPU, which served as a secret police force and counter-intelligence organization in charge secret political and state security matters, primarily consisting of surveillance, detention, interrogation and execution work while operating a network of secret prisons. Beyond that the GPU was also placed in charge of safeguarding state secrecy and investigative work requiring discretion. As Director of the GPU, Sverdlov turned to his old, trusted ally Filipp Goloshchyokin, who had proven himself utterly loyal to Sverdlov and the revolutionary cause, without any moral compunctions in pursuing the bloody secretive work done by the Directorate, and intelligent enough to maintain order amongst some of the psychopaths who gravitated towards work in the directorate. Beyond these two directorates, Sverdlov was able to ensure influence over the Commissariat of Military Security and Intelligence as well as the Foreign Intelligence Directorate of the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs by having them collectively answer to Sverdlov in his post as Chairman of the Committee on State Intelligence in addition to their ordinary chains of command (6).

The ascension of Anatoly Lunacharsky to the Central Committee, while strengthening the Governing Clique, also brought what was known as the Vpered Group to the center of Soviet politics. Named for the Vpered magazine which they had once published together, the group included not only Lunacharsky but also Alexander Bodganov, Mikhail Pokrovsky, Aleksandr Voronsky and Maxim Gorky. As men exceedingly interested in culture and education, the Vpered Group had secured nearly complete control over the educational and cultural state organs in Soviet Russia, using the opportunity to catapult Proletkult to ever greater heights, even as the movement was splintering along Futurist and Traditionalist lines.

The Futurists, who had been around since the pre-revolutionary days, believed in the total fragmenting of all that came before, with a heavy emphasis on the modernist and futuristic, on the speed and power of revolution, while the Traditionalists held that the emphasis should be upon the realistic depiction of life in a revolutionary state. They rejected the complex and distorted reality portrayed by the Futurists, instead aiming towards the production of proletarian art which showed realistic representations of the joys of revolutionary Russia through the everyday life of the people, dismissively portraying the Futurists as lacking in class-consciousness, party loyalty and truthfulness. This divide was to equally divide the Vpered Group, with Maxim Gorky as a vocal proponent of the Traditionalists and Voronsky as an ardent defender of the Futurists, describing the Traditionalist approach as artificial, lacking the deeper understanding of humanity which was made possible in Futurist works. While ordinarily, these two movements might have ended up seeking to destroy the other, the other members of the Vpered Group were able to maintain a balance between the two wings of Proletkult, allowing the movements to develop in dialogue and opposition to each other, enriching both movements in the process and further strengthening the popularity of Proletkult as a cultural movement.

The cultural freedoms enjoyed by Russian writers and artists of all sorts, which had drawn thinkers, writers and artists from across the globe, came under scrutiny following the Siberian Campaign and Trotsky's resultant rise in power and authority. While largely supportive of the relatively free press and art, Trotsky also came to discover that there was a path forward for him to establish a foothold in cultural affairs which led him to begin lobbying the Central Committee in 1931 on the issue of censorship, pointing out the way in which the reorganisation of the Cheka had failed to pass on censorship duties to a proper superseding authority, having allowed for the spread of capitalist and imperialist works, primarily from Germany and France, without any control or oversight on the part of the government. This was highlighted by the showing of an anti-communist documentary film by Eduard Stadtler, a fervently anti-Communist German journalist and Reichstag member for the DNVP, in cinemas in both Moscow and Petrograd, which Trotsky presented at a meeting of the Central Committee - the movie drawing shouts of outrage at the wild claims asserted in the documentary. Having enflamed the passions of his fellow committee members, Trotsky moved to establish a Directorate for the Protection of State Secrets with charge of censorship in writing, press and art, with the new Director to be Trotsky's closest political ally and brother-in-law, Lev Kamenev. While there was some grumbling on the part of Lunacharsky, the Vpered's relationship with Kamenev was decent and they were soon able to iron out most of their immediate differences (7).

That being stated, where Lunacharsky was to make his great impact was in the sphere of education and scientific research. As Commissar of Education, Lunacharsky was responsible for the establishment of a vast network of public schooling which not only served to prepare the next generation for the future revolutionary struggle, but also provided widespread access to night-schooling for the general public which had the effect of increasing schooling drastically from the doldrums of the Great War period, when schooling had fallen to under 20% of children and horrific literacy rates, to crossing 80% in 1932 for the entire population - women only lagging behind by 4.3 percent. In 1924 a new school statute and curricula was adopted structured around a four-year school, a seven-year school which granted access to further technical schooling and nine-year schools which led directly to university-level education. Independent subjects were initially abolished in favor of more complex themes - in which multidisciplinary course studies were emphasized, but the immediate failure of this radical new approach saw swift backlash resulting in the re-adoption of individual subjects and the implementation of standardized school classes with co-education of boys and girls. Schooling was split into a Primary level, covering the four, seven and nine year elementary schools, while vocational and other schooling following the seven-year level were judged as being at the Secondary level with Tertiary or Higher education including degree-level facilities such as universities, institutes and military academies.

Determined to improve the resources available to the revolutionary state, officials within the Commissariat for Education would prove amongst the most hard working and fanatical in their duties. Research and scientific development was led at the highest level by the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Republic, an institution which had begun its life as the Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences. The conflict between the Academy and the Commissariat of Education was to prove one of the most significant challenges faced by Lunacharsky, who struggled mightily to secure control of the institution from its president Alexander Karpinsky. For years, the two were stuck in a constant struggle with more than a dozen proposed Communist Party appointees being rejected by the Academy, until finally in 1926 the Academy was formally subordinated to the Commissariat of Education and Karpinsky was removed from his post in 1928. After a great deal of back and forth with the members of the Academy, Lunacharsky was able to secure the appointment of Mikhail Pokrovsky as Chairman of a newly established Committee for the Academy of Sciences which replaced the post of President of the Academy. However, perhaps Lunacharsky's most influential contribution to the course of Soviet life would come in 1929 when he proposed the adoption of the Latin Alphabet in place of Cyrillic. After a good deal of back and forth discussion on the matter in both the Central Committee and Congress the measure was initially rejected, only to be taken up for consideration once again in 1931. After nearly a year of debate, the matter finally turned in Lunacharsky's favor with Sverdlov and Bukharin's backing, resulting in the official transitioning from the Cyrillic to a Latin alphabet by the Soviet Republic over the course of the remainder of the 1930s (8).

While Trotsky had his own supporters in the form of Kamenev and Kaganovich on the Central Committee, they were insufficient if he were to try to exercise the level of power that Trotsky hoped to. With Tukhachevsky firmly alienated and the Governing Clique having been his primary target in his extension of power, Trotsky could only turn towards the Anarchist Clique for further support. It is important at this point to clarify the nature of the Anarchist Clique in greater detail, for while its four primary members often acted in concert this was less due to them sharing a common cause and more to do with their united skepticism and distrust of the Governing Clique.

Lev Chernyi was an ideologically-motivated Individualist Anarchist, an ideology with exceedingly limited following in Russia, who had emerged as a uniting force amongst the Russian Anarchists and used his alliance with the other members of the Clique to take up a significantly greater political position than he would have ever had a chance to under other circumstances. He would also prove the figure most open to cooperation with Trotsky, having been amongst the first members of the Central Committee to deal with the Yekaterinburg leadership due to his position as Commissar for the Nationalities, dealing with the large and brutally oppressed tartar nations which had been subjugated by Kaganovich during the famine years. He soon found an intellectually stimulating conversation partner in Trotsky, even when they disagreed, and they were able to further each others political ambitions in the years that followed. This proved particularly significant when Chernyi came under assault by Bukharin in 1931 for what the latter perceived as the former's failure to incorporate the nationalities into the Soviet Republic properly, instead allowing them significant leeway on the basis of Chernyi's own beliefs, creating autonomous self-governing sub-republics wherein local traditions and power structures were allowed to remain in place, even when breaking with general Soviet policy. Trotsky's ardent defence of Chernyi was able to stave off a censure, and allowed for a continuation of the status quo, although from that day on Chernyi fell ever more directly into the Trotskyite Clique.

Maria Spiridonova was a different matter entirely. As a former Left-SR, Spiridnova was as, if not more, dedicated to the cause of revolution as anyone, having risen to fame even in the pre-war years as a revolutionary heroine. Ever worried about the excesses of the revolutionary government, Spiridonova had secured appointment as Commissar of Peasant Affairs, in effect charging her with managing the transition from semi-feudal oppression to revolutionary communes in the rural countryside, a task which would consume immense amounts of time and resources and led her to being in constant conflict with both the Agricultural Commissariat and the Cheka, as their repressive methodologies wreaked havoc on her attempts at improving support for the revolutionary cause across Russia's millions of farmsteads, villages and other rural outposts. With the incorporation of Yekaterinburg and Siberia into the Soviet Republic, Spiridonova got a front row seat to the incredibly horrific persecutions of the peasantry which had been undertaken in both regions, in the process developing a seething hatred for Trotsky, who she viewed as little better than a bloody-handed tyrant out to play Bonaparte to their revolution, a view which soon extended to Chernyi when it became clear that he had left the peasantry of the minority nationalities to rot under their ancient oppressors. As a result, while she remained wary of the Governing Clique, she came to view Trotsky and his followers as fundamentally unsuited to leadership, campaigning openly at Committee meetings for their expulsion.

The second woman on the Central Committee, Alexandra Kollontai, would prove herself the member of the clique least dedicated to their mission of checking the power of the Governing Clique. As Commissar for Welfare and Commissar of Women's Affairs, Kollontai had proven herself amongst the most talented of the new governing class. Exceedingly intelligent, fluent in numerous languages and conversant in just about any topic of intellectual weight, Kollontai had been a central figure of the RSDLP nearly from its inception, but had been a vocal opponent of the Muscovite government before the formation of the Communist Party, being particularly critical of their economic policies which she feared would disillusion the working classes as they created a new class of bourgeoise. While her husband Pavel Dybenko had grown into a prominent military leader during the years of civil war, and was viewed as a firm supporter of the Governing Clique, Kollontai remained skeptical. As leader of welfare efforts, she would coordinate closely with the Finance Commissariat and Education Commissariat, developing friendly relations with both Lunacharsky and Sokolnikov, even as she continued to disapprove of the latter's economic policies. Once she joined the Central Committee she proved a moderate, wavering between Anarchist and Governing cliques based on her convictions on any particular issue.

Finally there was the enigmatic Nestor Makhno. Despite being the undisputedly most popular figure amongst the Anarchist clique, he was also by far the least interested in the political intrigues of the Central Committee, largely holding himself as neutral on most matters and sporadically attended meetings, only really acting when it seemed as though either Sverdlov or Trotsky were becoming too influential in any one political arena. Instead, Makhno dedicated his full attentions to the rapid development of local institutions across Russia. From the formation of self-defense forces to serve as protectors against bandits and criminals as well as a ready source of manpower in case of war, to the development of equitable village communes freed from the strictures of the pre-revolutionary years and the development of village utilities and services - from schools, policing and micro-loan schemes by state-run banks to electrification, clean water and the development of employment opportunities - Makhno's constant drive and efforts for the betterment of local communities saw him become the most well loved of all the Soviet leaders, and as a result developed a capacity nearly equal to that of Sverdlov to overturn the applecart should the need arise (9).

Footnotes:

(1) The Soviet Union of TTL does not end up following the OTL planned-economy and command economy approaches which they fell into, instead we see a bit of an unholy mix of the OTL New Economic Policies coupled with anarcho-syndicalist elements of a decentralised communal economy and a command economy in select sectors of industry. While there are various troubles which consistently emerge, Sokolnikov IOTL proved himself incredibly adept at finessing the economy and predicting major issues beforehand. ITTL he has the power and authority to resolve those issues before they get out of hand, whereas IOTL his hands were often tied by figures higher up in the party hierarchy. It is worth noting here that despite significant efforts at improving agricultural production, it remains an ever-present challenge to the Soviet government, particularly when it comes to bringing proper food stock into the rapidly growing and industrializing cities. While this update won't deal with the issue, we will be addressing it at a later point.

Just adding a note here about who the various Central Committee members are at this point in time: Yakov Sverdlov, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Nikolai Bukharin and Grigori Sokolnikov; Lev Chernyi, Nestor Makhno, Maria Spiridonova and Alexandra Kollontai; Mikhail Tukhachevsky; Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Lazar Kaganovich.

Just to clarify how the Soviet system is set up, you have the Central Committee at the top, with the Chairman Sverdlov serving as its executive head. Each Commissariat has a Commissar heading it and a variety of bureaus, directorates and ministries below themselves. Then there are the State Committees which often correspond to a single Commissariat, but where there are also larger Committees which include multiple Commissariats below them. The various authorities and rights of any individual committee or commissariat vary from organ to organ, but in most cases when you have a one-to-one Committee and Commissariat, the Commissars will also serve as Chairmen of the committee. It is a complicated and byzantine system, but I hope this short explanation helps clarify any confusion.

(2) The entry of Trotsky into governmental affairs is predictably confrontational. Trotsky has gotten used to being the man in charge, and now suddenly finds himself constrained by collective decision-making. He is quick to act, and immediately begins trying to split the Central Committee, so as to secure greater authority for himself, and the obvious first target is Sokolnikov whose economic policies are not quite what many believe a socialist economy should look like. Following Siberia, the increase in Trotsky's personal prestige, hogging the glory of the achievement for himself, to the great annoyance of Tukhachevsky in particular as we will see, allows him to begin putting more pressure on members of the Central Committee, which is what leads to Sokolnikov losing control of a significant part of the economy. His success in retaining oversight is extremely important, as it ensures that he will continue to have a say in the economic decision making of the Commissariat of Industry even without controlling it, and thereby maintaining influence over the economy as a whole, but there is no way around how significant a loss this is for Sokolnikov.

(3) Unsurprisingly, the ideological framework created by Bukharin matches the attitude taken by the Muscovite Reds. Bukharin plays an extraordinarily important role through the State Planning Committee - which is a very different institution compared to the OTL Gosplan which it shares a name with. This is an organizing committee which establishes the rights and responsibilities of various institutions, not an economic planning committee as it was IOTL. Also worth noting here that the Commissariat of Communications has control over not only the postal system and telegraphs and regulations of all media - although responsibilities on some of this is shared with the Commissariat of Culture under Lunacharsky.

(4) Trotsky really wants to hold the positions held by Bukharin and Sverdlov - which would be similar to the level of power and authority exercised by Lenin and Stalin IOTL - but views the positions held by Bukharin as the most important. Even IOTL Bukharin and Trotsky were regularly at loggerheads with each other, and IOTL Bukharin was the one to formulate the ideological response to Trotsky's Left Opposition. It is worth noting here that Trotskyite ideology is pretty far from that of OTL because he retains his belief in War Communism, which he ended up abandoning IOTL. While he seeks to strengthen the Congress of Soviets, this is not so much to do with democratic accountability as because it is a vehicle for power which he is more adept at directing than Bukharin, who prefers his positions as Editor-in-Chief and Chairman of the State Planning Committee to parliamentary processes. It should also be noted here that the Trud newspaper mentioned here is not the same as that of OTL, but rather the government paper which Trotsky used as leader of the Yekaterinburg Reds - here he is taking that paper nation-wide, in the process challenging the central position held by Pravda and Izvetia.

(5) Tukhachevsky is not a happy sailor. Honestly, the entire Siberian Campaign ends up being a colossal disaster politically for Tukhachevsky, who ends up being held responsible for the various failures early in the campaign and none of the glory which comes later. I hope that the military reforms and restructuring makes sense to people and helps give a clearer understanding of the situation. I am well aware of the sort of weird position that the Strategy Commissariat ends up holding, but I think it is important to bear in mind that Tukhachevsky alienated much of the governing clique when he lobbied for Trotsky's entry, and they end up viewing the reorganisation as a great way of both increasing their own power in the military, which Tukhachevsky has been jealously guarding up to this point, while driving a wedge between him and Trotsky. It is worth noting that the Military Security and Intelligence Commissariat ends up in charge of a lot of the more secretive technological development and authority over the Commissariat is split between the Supreme Military Soviet and the Commissariat of Internal Affairs which Sverdlov personally heads (we will get into all of that in the next section), so military policing, dispatched political commissars, security forces and intelligence gathering are only partially under the control of the military, Sverdlov seeking to insert himself into that sphere of government to the detriment of Tukhachevsky. Specifically it is the GRU - The Main Intelligence Directorate of the Military - which answers to the Commissariat for Military Intelligence and Security which ends up partially under Sverdlov's thumb. Also worth reiterating here that Frunze is an old Trotskyite ITTL, so his appointment is widely viewed as an extension of Trotsky's authority into the military.

(6) Sverdlov holds an immensely important position in the Soviet state, and has the capacity, should he wish it, to remove anyone from any position given his control over the security and intelligence forces. Sverdlov was one of the most intellectually inclined of the early Bolsheviks - to the point that when Stalin was asking for shipments of milk while they were in exile together in arctic Siberia, Sverdlov was lamenting the lack of good books. He was a man who made friends easily and from my read disliked getting involved in the political infighting of the party, while he was General Secretary of the RSDLP (prior to it becoming the Communist Party) he largely remained impartial in the political infighting, which is in sharp contrast to Stalin who used the position for intense political combat. However, while Sverdlov might have been reluctant to get bogged down in the infighting, that does not mean he was or ITTL is a pushover. I think this is a good place to mention that when I have ordinarily used the Central Committee ITTL, I have been referring to an amalgamation of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Central Executive Committee, the membership of the two bodies is identical and meetings of the CC shift regularly between the two, the CEC serving as the head of the executive branch and the CCCP serving as the leading organ of the Communist Party. The Council of People's Commissars is a much larger body including all of the commissars, and functions as the ministerial cabinet of the Soviet Republic.

I also hope that the division between the GBU and GPU makes sense, basically the GBU maintains all the aspects of the security apparatus which people run into on a general basis, while the GPU is in charge of all the secretive affairs of the state. This division has the effect of removing the horror of the Cheka regime from public view, allowing the Commissariat of Internal Affairs to present a welcome face to the public in the GBU, while maintaining the power of a totalitarian state in the shadows through the GPU. I hope that this helps make clear exactly how different Sverdlov's approach to rulership is from that of Stalin or any of the other Soviet leaders of state from OTL. Sverdlov has a quiet scholarly air to him and rarely raises his voice or gets into arguments with others, but if you cross the lines he has set you could disappear one night as though you never existed in the first place. This is to mention nothing on the immense treasury of blackmail material that he collects through the various intelligence directorates. A final note - while the Commissariat of Military Security and Intelligence is ostensibly of a higher position than the other intelligence directorates, it's intelligence section the GRU is placed on an equal footing within the Committee on State Intelligence and is firmly under the control and authority of Sverdlov.

(7) As some might have noticed the Traditionalist branch of Proletkult described are the early developments of OTL's Socialist Realism movement which Stalin proved a great supporter of and which eventually subsumed all other artistic movements in Russia. Without the interference of Lenin and Stalin, both of whom constantly meddled in cultural affairs, often to the detriment of all, Lunacharsky is able to maintain his benign non-interference approach, simply allowing both the Futurists and Traditionalists to keep developing in competition to each other, forcing both movements to constantly seek to better themselves in contrast to their rivals. Thus, instead of the OTL cultural stagnation which resulted from over-censorship and blind support of Socialist Realism, we instead get a dynamic cultural scene which draws great interest both at home and abroad. While the Cheka maintained some censorship duties, their reorganization led to censorship falling through the cracks until Trotsky noticed an opportunity to interfere. I should also mention that Kamenev proves a far lighter hand than the OTL censorship, a precedent of supporting relatively free artistic expression having already developed in the more than a decade-long life of Muscovite Communism which serves as the foundations on which the Soviet Republic has been built.

(8) The school structures outlined here are largely based on OTL, as they were implemented by Lunacharsky during his time as Commissar of Education. The conflict with the Academy of Sciences plays out differently, culminating in the adoption of a committee-structure in order to secure the appointment of Pokrovsky where IOTL Karpinsky retained his post. One really important thing to note is that education continues to follow the relatively laisse faire approach of Lunacharsky, without the political interference of OTL to a large degree. The adoption of the Latin Alphabet is based on the fact that Lunacharsky proposed such a measure IOTL. ITTL he is a lot more powerful and influential, and the committee is a lot more open to adopting new ideas than the stolid Stalinist regime which was coming to power at this time IOTL, which results in the measure eventually being adopted. It is worth noting that Lunacharsky placed a particular emphasis on including teaching in both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets in the various schools, so most people are literate in both alphabets. The increases in literacy are pretty close to OTL as well - the first decade under the Soviet Union honestly saw some pretty miraculous accomplishments despite the bitter partisanship and political infighting, to mention nothing of the constant terror and bloodletting, when compared to the decades which followed.

(9) And here we see the gradual disintegration of the Anarchist Clique as the primary opposition to the Governing Clique, with the Trotskyites stepping into their place. It is worth reiterating once again how diverse the Anarchist Clique actually is - Chernyi was an individualist anarchist ideologue, Spiridonova was a near-on worshipped SR hero and one-time terrorist, Kollontai was actually a part of the RSDLP before it fragmented totally during the chaotic year which followed the deaths of Stalin and Lenin while Makhno was an anarchist turned peasant-leader. And that is just the top layer of those associated with the clique. In effect, the Anarchist Clique became a catch-all for anyone opposed to the Governing Clique's approaches, spanning numerous different leftist affiliations, with their own disagreements and independent points of view. With Chernyi, Trotsky has four of the twelve seats on Central Committee, with the potential to bring over more under the right circumstance - particularly if he presents himself as a counterpoint to the Governing Clique. We are effectively seeing the Anarchist Clique falling to the wayside as the main opposition to the Governing Clique, with the Trotskyites stepping into their place.

Leon Trotsky

The Russian Bonaparte

While Trotsky made plenty of waves within the legitimate confines of the Soviet state, it would be his actions beyond that state which truly defined his swift rise to power and authority, much as happened with the Siberian Campaign. His successful usage of covert activities, martialing resources squirrelled away in the lands of Yekaterinburg, convinced Trotsky that this was the best way forward for him if he truly wanted to secure a dominant position within the Soviet Republic to bring about the World Revolution. While Trotsky had focused his attentions on extending his power within the state, as international Communism began to make major strides in Persia, China, India, Japan, Latin America and Europe, Trotsky sponsored the training and education of not only revolutionary leaders but also their militant supporters. While relations to the Communist state of Italy were troubled, with Trotsky in particular viewing the renegade regime with considerable aversion for their support of the abominable Revolutionary Catholic Church, and saw the Khivan regime as an intransigent break-away state dominated by a leadership consumed more by greed than revolutionary zeal, Trotsky maintained a strong relationship to the Iranian government.

While the Jiaxing Communists would receive some covert aid from the Soviet Republic, it would be with the Two Rivers Crisis that Trotsky truly became convinced that the time for action had come. While the Tudeh leadership in Iran had already begun to act against Pessian Persia, Trotsky was swift to press the Central Committee to back the effort while also dispatching Yekaterinburg partisans to aid in the Iranian advance without the knowledge of the rest of the Russian leadership. While Persia fell swiftly to the advancing Iranians, word soon reached the Central Committee of a considerable number of Russian advisors in the Iranian forces - advisors who had not been dispatched by the Supreme Military Soviet. When it emerged that Trotsky was behind this initiative it caused considerable anger and distrust amongst the leadership towards Trotsky, with Kollontai openly accused Trotsky of Bonapartist ambitions. Nevertheless, Kollontai and the lesser members of the Governing Clique could do little but grumble when Trotsky's gamble once again proved successful as Persia crumbled under the twin pressures of internal collapse and external pressure.

While Trotsky angrily denounced the subsequent signing of a naval treaty prohibiting Russian naval bases on the Persian Gulf coast, he was immensely pleased to see his gamble pay off once more, his belief that the future of the revolution was to be found in Asia having proven true once more. It was not solely sore feelings at Trotsky acting independently of the Central Committee which caused aggravation, but also the way in which his aggressive support for the revolutionary effort internationally greatly inconvenienced the committee members who had spent years working to improve the international standing and trust of the Soviet Republic. As part of the negotiations which ended conflict with the European Powers, the Muscovite state had agreed to ending sponsorship of revolutionary movements internationally, and in the years since those domains had enjoyed a beneficial relationship with particularly the German Empire.

However, with the Conquest of Siberia wariness amongst the Germans had been increased considerably, and with the fall of Pessian Persia worries about the rise of Communism took firm hold in Europe - even if trade and dialogue with the Germans continued. Trotsky's successes in Persia served to spur him on, and he soon began campaigning openly on the Central Committee and in the Congress of Soviets for support of the aspiring Communist movements around the world, arguing that as the first to throw off the yoke of oppression, Russia should take a leading role in perpetuating the world revolution. He was persuasive, weaving into his rhetoric references to Marxist dogma and appealing to the same instincts which had once spurred on the abolitionists, revolutionary bourgeoisie, the suffragettes and the Jacobins, the cause must be pressed forward, those in bondage must be liberated (10).

Through hook and by crook, Trotsky was able to convince the Congress of Soviets to issue a Declaration of Brotherhood with both the leadership of the Indochinese Revolt and the South China Revolt, inviting the Jiaxing and Indochinese Communist Party to enter the Third International. Trotsky, emboldened by success in Persia, pushed onward aggressively, arranging a secret meeting with Ikki Kita in August of 1933 at Vladivostok wherein Kita, with permission from other members of the Nippon Kyosanto, signed a memorandum secretly joining the Third International while M.N. Roy publicly participated in joining the Communist Party of India to the Third International. However when Italian representatives hoping to join their Communist Party to the Third International arrived, Trotsky led a public campaign to reject their approaches which so offended the leader of the delegation, Amadeo Bordiga, who had been the person arguing incessantly for the party to join the Third International despite Gramsci's personal concerns about such a measure in the first place, that he left the country a week after arrival without having joined the organisation, loudly and publicly denouncing the Soviet State as an anti-Revolutionary rightist conspiracy meant to lead the international communist movement down the wrong path. This was the first of many disagreements which would come to characterize the Communist Russo-Italian relationship and their respective branches of Communism in the years to come.

Nevertheless, simply recruiting new branches to the International would not prove sufficient to Trotsky, who hankered for further success to push forward the revolution, theorising that the rotten edifices of the imperialist powers in Asia were on the verge of collapse, and that a few good blows would throw the entire continent into open revolt. However, Trotsky felt that before this push could really be undertaken the final divergent strain of Russian Communism had to be brought fully into line with the wider movement. It was time to deal with Khiva. Beginning in November of 1933, Trotsky began a series of concerted attacks on the independence of Khiva, viciously attacking the Caucasian Clique as rightist profiteers using the cause of the revolution to mask their self-aggrandisement and kleptocratic government which placed a stain upon all revolutionary governments alike. Only by purging the rot from the revolutionary cause could the world revolution be undertaken in the eyes of the Trotskyites.

In the Congress of Soviets, Trotsky and his supporters held one grand speech after another condemning the Khivan government and calling for its restoration to the Soviet Republic, so that there would be no internal divisions to weaken the International as it moved on to the critical period of revolutionary surge. Meanwhile, Trotsky continued a constant barrage of anti-Khivan rhetoric in writing through the newspaper Trud, while calling upon all fellow revolutionary luminaries to speak up in support of his motion. In the Central Committee, the topic of discussion for weeks on end were on the Khivan issue, with Trotsky swiftly backed by Chernyi, Kamenev, Kaganovich and, less fervently, Tukhachevsky. However, Maria Spiridonova was quick to pick up Kollontai's warnings of Trotsky's ambitions, beginning to openly question whether Trotsky actually wanted to further the revolutionary cause or was simply looking for another success to bolster his popularity in preparations for ascension to total power.

What had previously been whispers about Trotsky's Bonapartist ambitions were becoming key talking points during committee meetings and soon spread when Bukharin published a joint editorial in both Pravda and Izvetia warning of the dangers of one-man rule and Bonapartism to the dynamism and legitimacy of a revolutionary movement. Although Trotsky was not mentioned in this editorial, there was little doubt as to who Bukharin was calling out - and others soon took up this call. In the Congress of Soviets, Trotsky's speech on the 18th of December was met with calls of Comrade Bonaparte and cries of Tyrant! When Sverdlov finally spoke up in opposition to breaking the solidarity of the Third International on the 4th of January 1934, Trotsky's movement came to a sudden and dramatic halt, now facing an insurmountable challenge. Thus, on the 9th of January the Central Committee voted firmly in opposition to Trotsky's proposal, Tukhachevsky jumping ship to join Kollontai, Spiridonova and the Governing Clique to oppose the measure. Trotsky was left rejected and angry. However, this was not the first time that Trotsky had seen his ambitious plans for the furtherance of the revolution stymied by the Central Committee, only for success to see him forgiven, and on the basis of the considerable support he had been able to muster during his public campaign against the Khivans, he was certain that this time would be no different (11).

Trotsky would turn to Isaak Zelensky, the General Secretary of the Kirghiz Autonomous Region which dominated the borderlands with the Khivan Khanate. A longtime ally of Trotsky's, Zelensky had served in a variety of posts along the border with the Khivans and Siberian Whites since early in the Civil War with distinction, and had maintained such a role even after the unification. In coordination with others, most prominently Ivan Nikitich Smirnov, another long-term Trotskyite who had previously played a central role in managing the dispatch of forces to Iran, and Vitaliy Markovich Primakov, the Komkor commander of those forces, would begin to shift forces into the Kirghiz Autonomous Region over the course of February and March of 1934. However, fearful of discovery, Trotsky and his supporters were forced to move against the local GBU and particularly the local GPU units to maintain secrecy.

While no one was harmed, the entirety of the local GPU office was secured and placed under temporary arrest while the GBU commander, Yakov Agranov, a former Chekist who bitterly resented his exclusion from GPU services during the reorganisation, was convinced to support the Trotskyite plans. However, the efforts at maintaining secrecy would force the conspirators to act with dangerous sluggishness, slowly moving more and more forces into the region over the course of several months while praying that the continued silence from the local GPU office would not alert the security forces. While at first glance an extremely unlikely feat, it was determined worthwhile due to how small the local office was and how irregularly their contact with superiors occurred. However, by the end of March the number of forces in the region had surged to nearly 150,000 in bases stretching along the Khivan border and plans were gotten under way for the coming campaign, scheduled for the middle of the month.

It was at this point that these troop transfers, facilitated by Trotskyites in the Commissariat of Strategy, came to the attention of Commissar Frunze during a spot check on his subordinates. Unable to figure out what exactly was occurring, Frunze, who had been excluded from the plans due to worries of his willingness to participate in such an endeavor, began to query both his own subordinates and the other Commissariats of the Supreme Military Soviet, which led to the matter being brought up at the Committee on State Intelligence. From here, queries to the GBU office returned a suspiciously un-detailed all-clear from Agranov while the response from the Kirghiz GPU office failed to match protocol, sending alarms through the entire intelligence community. As the Trotskyites began to realise that they were on the verge of being discovered, they kicked preparations into high gear, bringing forward the date of the invasion by a week, while it became increasingly clear what was going on.

GPU agents under one of Goloshchyokin's rivals for leadership of the GPU and Dzerzhinsky's former second-in-command, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky, were rushed to the region to determine what was actually going on, bringing a heavily armed contingent of GBU security forces from the capital with them to act as their armed fist, while Tukhachevsky issued orders to forces in the Kirghiz Autonomous Region to halt all operations until further notice. As Menzhisky descended on Orenburg, terror began to grip the Trotskyites. A man of considerable learning, speaking more than a dozen languages, including Turkish, which would prove of vital importance to the investigation, Menzhinsky had experienced a precipitous loss of position with the death of Dzerzhinsky, losing out in the struggle to succeed him to Uritsky before securing the position of GPU Investigative Department Head. In this role, Menzhinsky had conducted a number of important but secretive investigations and, more publicly, been in charge of hunting down the remaining White sympathizers in Siberia following the conquest. A sickly man suffering from acute angina since the end of his service in Siberia, Menzhinsky relied heavily on his deputy Artur Artuzov, a one-time Yekaterinburg Trotskyite who had directed the initial covert actions which provoked the Siberian Campaign, but who had since turned his back on them when it became clear that such allegiances would scupper any hope of a long-term career in Sverdlov's intelligence organisation, to conduct the investigation.

Zelensky, realising that they were on the verge of discovery, fled - eventually making his way to Japan where other spooked Trotskyites would gather in time. The flight of the General Secretary of the Autonomous Region on the 4th of March sent alarm bells ringing, and soon saw the GPU agents held by Agranov's GBU men discovered and released, with the entire GBU department placed under arrest. Arrests soon picked up pace as more and more information on the Trotskyites' plans came to light. As word of all this made its way back to Moscow, an emergency session of the Central Committee was called in which Trotsky was called upon to answer for his actions, which he refused, and was followed, on the 7th of March 1934, by a vote to suspend Trotsky from the Central Committee until the truth of the situation could be ascertained. While Chernyi, Kaganovich and Kamenev voted in opposition, the rest of the committee members voted in favor, whereupon Trotsky was removed from the room and placed under temporary house arrest by a discreet guard of GPU officers while the scope of Trotsky's actions were taken under examination and a proper determination of his punishment could be ascertained. Trotsky had gambled and failed. The question everyone was left asking was, what would the consequences be (12)?

News of Trotsky's house arrest and removal from the Central Committee spread with incredible speed through Moscow, although the reasons for this action and whether or not he had been expelled from the party or the Central Committee remained a topic of discussion and uncertainty, with rumours claiming everything from a failed coup on Trotsky's part, a military coup on the part of Tukhachevsky or treachery on the part of the Governing Clique, out to remove any opposition to their grip on power, to claims that Trotsky had been found in bed with Bukharin's scandalously young wife Anna Larina and that this was revenge on the part of an angry cuckold being floated. However, one thing remained clear, Trotsky was in danger and that only drastic action could save him. Having spent the last eight or so years in Moscow, and having gone out of his way to interact with the public, Trotsky had succeeded in building a significant following in the city, particularly amongst the younger sections of the population who saw his renegade act as a source of inspiration. Therefore, it was not long before groups of young men and women took to the streets, bearing placards and chanting for Trotsky to be restored to his post. Thus, the Trotskyites found themselves in a troubled positions as their benefactor and leader was reaching a crisis point. When word of the public protests began to spread, a core group of followers including Kamenev, Karl Radek and the young Chairman of the Moscow City Committee, Nikolai Bulganin, began to plot to secure Trotsky's release, by force if need by. While Kamenev was hesitant, he found himself spurred on by the much more dynamic Radek and ambitious Bulganin, who saw this as an opportunity to catapult himself to power in Trotsky's time of trouble.

In the meanwhile, the GPU was conducting an extensive investigation under the direction of Mikhail Pavlovich Schreider, an immensely talented investigator and protégé of Menzhinsky, and Joseph Ostrovsky, the head of the Financial Crimes section of the Investigative Department under whom Schreider had worked for years. Schreider had made a name for himself by his willingness to go after even his own colleagues when they went against regulations or engaged in corrupt activities. In fact, Schreider was hand-picked by Sverdlov for the investigation, having been immensely impressed by the young GPU agent's dedication to his work and unflinching reserve. Schreider, with unlimited manpower resources, was swiftly able to comb through the documents of Trotsky, many of which would have been more than enough to establish Trotsky's disregard for the Central Committee and involvement in the Zelensky Case, the name given to the investigation on the basis of the important role played initially by the former Secretary General, which soon saw the investigation grow. Before long, Trotsky's long-time allies were seeing their homes torn apart as an ever growing mountain of evidence of wrongdoings of all sorts were unearthed.

It was under these circumstances, and with public protests still growing larger, that Radek was able to convince Kamenev to support his plans for action a week after Trotsky was first placed under house arrest, the 14th of March. It was here that Komdiv Boris Feldman, commander of the 32nd Rifle Division based out of Naro-Fominsk, not far from Moscow, came into play. A later Trotskyite adherent, Feldman had originally been a Tukhachevsky acolyte, but had turned against his former patron over the Commander-in-Chief's failure to provide him with a field command during the Siberian Campaign, placing him far behind those of his peers who had participated in the campaign and likely ending any hope of a major command down the line. Trotsky had been swift to learn of this enmity, and worked to befriend the embittered division commander, as he did so many others during his years in Moscow. When Feldman was contacted by Radek about using his forces to free Trotsky, who, it was becoming increasingly clear, was unlikely to make it out of the current crisis without aid, he moved swiftly, calling up the active troops in his division under the claim that he had received orders to enter Moscow and restore order.

Within the day the Division was ready for action, setting out for Moscow early on the 15th. Simultaneously, Trotskyite figures joined the public protests, working to enflame the crowds further with wild claims that Trotsky was being tortured and that Kaganovich, Chernyi and Kamenev were all facing arrest as the Governing Clique set out to conclude their coup. Within hours, the crowds had swelled to the tens of thousands, leading Uritsky to order the deployment of many thousands of GBU men, from the Militsiya, Security Forces and more, while the Central Committee was consumed with talk of whether to call up the military. Eventually, the order was given for August Kork, who had been promoted to Military Governor of the Moscow District for his actions in Siberia, to mobilize nearby divisions to potentially aid in bringing the unrest to an end. It was around an hour after this order was given that word came back that the 32nd Rifle Division had set out for Moscow before any orders had been dispatched, a message relayed by an unwitting secretary from the division headquarters. Even as the protests began to turn violent, GBU forces clashing with the protesters, word that a division was marching on the city without permission raced through government ranks provoking great worry and consternation (13).

Trotsky remained largely unaware of all of these events, as he was forbidden from meeting with anyone not involved in the GPU investigation, preventing him from having any influence on how the events that followed played out. As word that the 32nd Rifle Division was approaching Moscow proper reached Uritsky, he began to redirect the available security forces, augmenting them with the two regiments who were part of the Moscow City Garrison, amounting to some 5,000 men in all, rushing them across the Moskva River to the Moscow State University on the southern bank and blocking off Leninsky Prospekt, renamed in honor of the martyred party leader, the road leading from Naro-Fominsk to the heart of Moscow. Barricades were swiftly constructed as the defenders dug in, even as the protests in the northern parts of the city descended into riots as security forces fell back, their numbers reduced to respond to the forces approaching from the south-west. This weakening of security forces, as well as the associated denuding of guards watching many of the Trotskyite figures in the city allowed the conspirators to act swiftly. Using a unit of hardened Yekaterinburg veterans secreted away in the capital, the Trotskyite conspirators launched an attack on Trotsky's home in hopes of freeing him. GPU and GBU guards were caught by surprise, more than a dozen getting killed in the first minutes of fighting as the guards were forced into retreat. Trotsky was secured by his supporters, if utterly confused at the sudden violence which had allowed his release, but quickly began to gain a picture of what was going on.

At nearly the same time, the advance forces of the 32nd Rifle Division slammed into the defensive line constructed along Leninsky Prospekt. Initially unclear about the identity of who was blocking their path, the advance forces under the command of Colonel Nikolai Ibansky launched an attack on the barricades, exchanging fire for a couple minutes before they were repelled. Surprised at the ferocity of the resistance, having initially believed the barricade to be held by the rioters they had been dispatched to crush, Ibansky sent up a white flag, hoping to get a clearer understanding of the situation. When Ibansky met with the GBU and regimental commanders, he soon discovered to his horror that his men had been attacking government forces. By this time the following troops of the Rifle Division were catching up to the advanced guard, surprised to find it halted and negotiations under way. Increasingly thrown into confusion as to what exactly was going on, matters took a turn when Ibansky returned to his men with GBU agents in tow, who began to place the divisional commanders under arrest until things could be further clarified while the soldiers of the division were swiftly placed under the command of Kork, who took personal command of the division, lacking trusted commanders to take on the task at hand. At the same time, the riots were getting truly out of hand, as looting exploded, government buildings were attacked and Trotskyites under house arrest were released with their guards driven off or killed.

Trotsky sought refuge in a recently built housing complex, seeking to bring some level of order to affairs in order to get a proper picture of what was going on. However, by this point security forces were streaming back across the Moskva River, strengthened by an additional division worth of men. The sudden appearance of tens of thousands of heavily armed soldiers and security forces saw the riots and protests quelled with shocking violence - permission having been given to open fire upon any who resisted orders while an immediate curfew was announced, requiring everyone to hunker down. Thousands were arrested and hundreds more killed as the security forces swept through Moscow and the Trotskyite leadership began to bail out.

Coming to the realisation that events had turned against him, Trotsky directed his closest allies to make their escape from the city, aiming to return to their stronghold in Yekaterinburg until matters could be properly resolved. Kaganovich was directed to bring Trotsky's family in Moscow with him, Trotsky himself fearing that they would get caught up with him should they remain together, while Kamenev was asked to bring Adolph Joffe's family with his own as they made their escape. Trotsky himself was accompanied by Radek and Martov, while Bulganin remained behind, his involvement in the conspiracy not having been revealed to anyone outside the Trotskyite inner circle. However, things were not to go as planned. While Kaganovich was able to make his escape with Trotsky's family, his own and his protégé Nikita Khrushchev, Trotsky's group were caught out. Radek was killed in the resultant pursuit while Trotsky himself was captured with Martov. Kamenev initially made it out of the city, but was discovered by the military forces responding to August Kork's initial call to rally to Moscow and captured alongside his group. Kalinin was able to make his escape as well, bringing with him a collection of younger Trotskyite loyalists, and was soon on the road to Yekaterinburg with his ducklings in tow.

Over the course of the following week, the remnants of the uprising were crushed as further thousands were imprisoned in preparation for what was to come. Anyone with known Trotskyite affiliations were placed under arrest while Schreider's investigative team worked to tease out those Trotskyites who remained hidden. It was as part of this effort that Bulganin was discovered and taken into custody by forces commanded by the talented Colonel Andrey Vlasov, who had been leading his regiment from Nizhny Novgorod towards Moscow. At the same time, troops were rushed into the Yekaterinburg Military District, with Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko appointed Military Governor, and further mass arrests were undertaken as the Trotskyite following was removed from power. By the end of April most of these efforts had come to a successful close, as Kaganovich, Khrushchev, Kalinin and their various wards made their way to Japan, where they joined Zelensky and numerous other Trotskyites in exile (14).

The Trotskyite Affair, as the wider crisis and its aftermath was to be known, had fundamentally shattered the pre-crisis status quo. Central Committee Members had sought to provoke war with an allied nation against Central Committee directives, had instigated popular unrest in the capital which had seen numerous comrades killed or wounded in addition to considerable damage to the city itself, illegally called up military forces for what could only be assumed to be an attempted military coup, and several had broken house arrest orders with violence and sought to flee the city in preparation for unleashing a renewed civil war. Of the Central Committee Members a full third had been involved in the affair to one degree or another and had either fled the country or been placed under arrest while sympathisers and followers of these four individuals had spread throughout the massive Soviet state bureaucracy. Numerous Commissars had been arrested, alongside even more department heads and seconds, while a good section of the military had proven itself unreliable, to the point that some commanders would even be willing to march on the capital as a hostile force. It was a crisis like no other, of a scale and seriousness not faced by the Soviet Republic since the early days of the revolution, and it would require radical actions to resolve. To make matters worse, the already ill Committee Member Anatoly Lunacharsky had passed away in mid-March of 1934, creating even more gaping holes in the state bureaucracy which would need swift resolution.

Fearful that leaving the matter of Trotsky himself unresolved for long might provoke more chaos, bloodshed and violence, the Central Committee rushed to put him on trial, turning over the matter to Nikolai Krylenko, who had served as Prosecutor General since the death of Dzerzhinsky. Krylenko, a former central figure in the RSDLP who had lost out when the Moscow Bolsheviks took up leadership of the party, had been involved in running show trials for the Cheka before the reorganization, but since then had mainly been left to deal with more mundane trials resulting from GBU investigations. A strong proponent of what he called Socialist Legalism, a school of law which held that rather than whether or not criminality had occurred, it was rather the impact on party and state which should be emphasized, Krylenko hoped to use Trotsky's trial as his ticket to entering the Central Committee and as such set out to make it as great of a spectacle as he could. He invited numerous reporters, both foreign and domestic, to attend the trial and gathered together a massive portfolio of charges to level against Trotsky, both proven and presumed.

When the trial finally began, in early April, Krylenko soon discovered that he had bitten off more than he could chew. While the case against Trotsky was exceedingly strong, the public nature of the trial allowed Trotsky to use his greatest weapon, his mouth. Trotsky, taking his defence into his own hands, portrayed himself as an outraged party stalwart betrayed by a collection of grubby, corrupt and ambitious bureaucrats, persuasively arguing that he had only ever worked to further the Revolutionary Cause. On and on he spoke, drawing laughs and cries of outrage from the onlooking reporters, who faithfully noted down his words, while Krylenko sunk deeper and deeper into his seat. As the trial dragged on, day by day, over the course of a week and the situation worsened, Krylenko found himself the target of considerable anger and disdain in leadership circles, culminating with his replacement by his predecessor as Prosecutor General, Pyotr Stuchka an elderly former lawyer who had helped lay down much of the Soviet legal framework during the Civil War.