The Summer Offensives

American Plan of Attack For The St Mihiel Offensive

Into the Cauldron

The American First Army was as green as it was possible to be on the eve of their first great offensive. Having taken up control of their sector of the front in early June, no more than a quarter of the divisions involved having even seen action on one of the quieter fronts, it had taken almost six weeks for everything to get into place, the American soldiers moving to find their positions and building up a sufficient store of munitions around the St Mihiel Salient to tackle the coming challenge. Pershing saw the attack on the salient as just the first phase of a deeper drive toward Metz, the opening gambit of the war-winning campaign as envisioned by the American leadership.

However, just two weeks before the massive attack was to begin, Foch asked Pershing to curtail or eliminate it, and to divide his American forces up between the French armies along the Champagne front in order to support the planned French offensive in that sector. After severe disagreement, Pershing and Foch were eventually able to come to a compromise. The Americans would destroy the St. Mihiel salient, and then immediately move the First Army forty-three miles to the northwest to take over a completely different portion of the front lines, between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River. There it would join the other Allied armies on the Western Front in conducting a simultaneous, general offensive along the entire Franco-American line from Soissons to Verdun.

The American army was constructed quite differently from any other army on the western front. First of all, their individual divisions numbered almost 28,000 men each - between three and four times as large as fully manned German divisions at this point in the war. Furthermore, the American artillery train was significantly smaller and less coordinated than any of the other combatants, having been deprioritised by Pershing in favour of a focus on the infantry as the fulcrum of military tactics, and lacked a lot of the support from their allies that might otherwise have been available as a result of the considerable British artillery losses in the Spring, and their resultant need for any and every competent artillerist, and the French occupation with the preparations for their own part in the Summer Offensives (1).

When the Americans thus took up their positions, they were far from prepared for the challenge before them. The St Mihiel Salient, located south of Verdun, was a heavily forested region dominated by the Heights of the Meuse to the west and a series of forests, streams and hills to the south. The area was undoubtedly among the best German defensive positions before the Moselle and since the German capture of the region in 1914 the salient had been densely fortified, becoming one of the strongest defensive points in the entire German line by the middle of 1918. While the forces in the salient had been greatly reduced during the Spring Offensives, German OHL had been swift to reinforce the region the moment troops became available once more.

Led by the indomitable General Max von Gallwitz, the German Fifth Army which was stationed in and around the salient numbered almost 350,000 men in some of the strongest defensive entrenchments anywhere in the world. Furthermore, the Germans were well aware of not only the general plans for an offensive against the Salient, they even knew specific details from the American operational plans, including where the weight of their assault would focus, the locations, length and duration of the initial bombardment planned and the specific date and time at which the assault would begin. All of this had been revealed in a Swiss newspaper and was brought to the attention of OHL and Gallwitz several weeks in advance of the American assault (2). The Americans could not be less prepared for their trial by fire, and the Germans not have been more ready for what was to come.

The Americans placed the vast bulk of their forces on the southern edge of the salient, compromising three Corps of the American First Army and a fourth on the western edge of the salient in the Allied sector of the Meuse Heights. Having foreknowledge of the American plans, Gallwitz had been able to redistribute forces for maximum effect. Thus, when the American bombardment began they found themselves targeting barely manned, heavily forested and strongly fortified positions with the hopes of cutting the massive bands of barbed wire that blocked their way. Beginning the extremely short 4-hour bombardment at 5 A.M. on the 13th of July 1918, Pershing having hoped to take the Germans by surprise, the Americans went over the top at 9 A.M in beautiful sunshine and to the trilling of birds.

Despite the artillery bombardment having little to no effect on the barbed wire, and French observers having deemed the heavy bands of barbed wire impassable until engineers, artillery, and tanks could remove them, impatient American troops simply walked over the barbed wire, to the astonishment of everyone but themselves, and into the barrels of the German machine-guns. Surprised by the speed of the American advance, particularly furthest to the east in the salient around Pont-a-Mousson, the Germans found themselves initially swept out of their forward trenches with surprising ease by the American I Corps (3). However, when the Americans began to run up against the second line of trenches south of Thiaucourt, where the Germans were far thicker on the ground and in much closer range to the German artillery, they were forced to a bloody halt. The German bombardment was like nothing any of the Americans had ever experienced, and every attempt to push forward quickly found itself targeted and blasted to pieces by the heavy German artillery. Push after push was attempted over the course of the first day, particularly south of the village of Thiaucourt, but there was nothing the Americans could do to press forward.

Over the course of the first day of assaults the I Corps would take in excess of 6,000 casualties. Further west, the situation was a lot grimmer. While the IV Corps had succeeded in pressing forward at the center and right of their line to almost the same depth as the I Corps, their left flank had run squarely into the German hardpoint atop Montsec and along the Rupt de Mad stream, which the Americans succeeded in crossing at four points during the first day only to be thrown back across it by fierce German counterattacks. From the heights of Montsec, the Germans were able to see exactly where the American positions were and directed their artillery closely therefrom. By the end of the first day the IV Corps had taken almost 9,000 casualties. Overhead German and American fighters clashed in some of the fiercest aerial combat of the war, almost fifteen hundred fighters in all.

The American II Corps had fared even worse than the other two, attacking the Meuse Heights and St Mihiel itself. With their right flank trying to secure Montsec with little success and direct attacks on the Heights quickly breaking down, it would only be the left wing of the American assault that saw any forward progress, inching forward towards St Mihiel out of a bend in the Meuse under Allied control. The bombardment faced by the II Corps dwarfed anything faced by the other corps and ground down the attacking divisions on a scale unimaginable to the Americans. During the first day, the II Corps took more than 15,000 casualties. This left only the V Corps' attack on the western side of the salient, which proved a bloody and grinding affair with a great deal of back and forth in the heavily wooded heights, with casualties at the end of the first day amounting to some 7,000 amongst the American troops. Thus, by the end of the first day the Americans had taken around 37,000 casualties, the vast majority of them to the German artillery, which sharply contrasted with the German losses of around 6,000 in total.

These casualty numbers were worse than anything predicted by the American commanders, who had estimated around 50,000 casualties in total by the end of the offensive (4).

The following two days saw the Americans renew their assault across the salient, with the II Corps reaching the outskirts of St Mihiel while the IV and I Corps took around 100 meters worth of ground towards Thiaucourt and the V Corps pressed further down the Meuse Heights. However, these minor successes were paid for dearly, with a combined 31,000 casualties by the third day in return for another 6,000 German losses. By the end of the third day, the American commanders called a halt to the attacks and decided to change their approach. Rather than commit to an attack across the line, they would focus their resources at select points along the salient that presented either a major opportunity or a significant threat (4).

The targets eventually chosen were St Mihiel town, Montsec and Thiaucourt, thus the tanks available to the Americans were shifted to the far eastern edge of the front in preparation for a push to Thiaucourt, while the vast majority of the artillery available to the Americans was concentrated around Montsec in preparations for a massive bombardment of the mount. At St Mihiel there was little more to do than just press on into the town. Thus, during the fourth and fifth days of the offensive there was little movement and much fewer casualties, the Americans losing a combined 6,000 to 2,000 Germans in this period. The following armored attack on the sixth day, launched by Liutenant Colonel George Patton with a single tank brigade numbering 50 Renault-FT tanks, hammered home against the Germans and pressed them back to the outskirts of Thiaucourt over the course of the first day. Despite the success of this assault, it eventually ground to a halt as a result of mechanical failures, attrition and harsh German resistance, leaving 20 tank carcasses behind and a further 15 unable to function for the next several weeks while repairs were undertaken.

This marked the first major American success since the initial crossing of the barbed wire on the first day and immediately made Patton a household name in America. Nonetheless, the assault would amount to another 12,000 for the I Corps, with the Germans taking a bit under 7,000 casualties and losing some 300 captives. From the eighth to the tenth day of the offensive the focus shifted to Montsec, where the heaviest American bombardment of the entire campaign was undertaken. Over the course of 48 hours the Americans would fire half a million shells, much of the stockpile available to them at the time, smashing the mount to pieces. The sheer weight of explosives would lead to parts of the mount collapsing in on itself while the Germans were forced off the top of the mount, taking refuge in its shadow and in their deep bunkers. Ultimately, this bombardment would result in around 1,000 casualties for the Germans combined.

At the same time, the American drive on St Mihiel ground on inexorably, day by day, meter by meter, as the Americans pressed into St Mihiel town under an incredibly heavy bombardment. The constant rain of gas shells and limited frontage meant that many of the men attacking at the apex of the salient were forced to wear full anti-gas gear 24 hours a day, causing intense discomfort and significantly reducing combat effectiveness. By the time the II and IV Corps attacked Montsec on the twelfth day of the offensive, the II Corps had already taken 33,000 casualties around St Mihiel, with the Germans losing 14,000 in the same span, and would accumulate an additional 18,000. This was matched by the IV Corps, who collected 27,000 dead and wounded in the push to secure Montsec - which they succeeded in on the 29th of July, leaving behind 24,000 German casualties by the sixteenth day of the offensive (5).

Footnotes:

(1) The only real difference from the OTL Allied forces is that the Americans receive even less support at St Mihiel than they did IOTL. The reason for this is that the St Mihiel attack is not viewed by the French as a particularly critical assault. Both Foch and Pétain believe that American hopes of taking the well defended salient are minimal and want to focus their attention on the main focus of the Summer Offensives. The Americans had grossly overestimated the importance of riflemen and underestimated the importance of artillery IOTL, a fact that was pointed out to them on multiple occasions to little response IOTL and ITTL. Bear in mind that this isn't particularly out of character for any of the larger powers when they first entered the war - the French, Germans, Austro-Hungarians and Russians all learned sharp lessons in 1914. The same happened for the Italians in 1915 and the British in 1916. Now it is the turn of the Americans to go through it.

(2) There are several very important differences here from the situation during the OTL Battle of St Mihiel. First of all, IOTL the German forces in the salient were outnumbered some 50,000 to around 650,000-700,000, with the Germans also greatly weakened from the Spring Offensives and severely demoralised. By contrast, ITTL it is a force of 350,000 Germans against some 550,000-600,000 with the Germans buoyant from one of the most successful offensives of the entire war. Furthermore, IOTL the Germans were actually already pulling out of the salient when the Americans attacked because they were so outnumbered and undermanned, whereas here they are much better off with plenty of men to fill the trenches and fortifications. The entire battle is taking place almost two months earlier than IOTL and under significantly more constrained conditions for the Americans than IOTL. In addition, as in OTL the Germans are completely aware of what the Americans are going to do - the whole leak of the war plans to a Swiss newspaper and the Germans learning of it from them is completely OTL. IOTL the Battle of St Mihiel was a cakewalk, not so much this time around.

(3) The American crossing of the barbed wire mentioned here is based on a stroke of luck IOTL which I decided to transfer. They are able to make good headway, but are about to run into fierce opposition. The whole 4-hour bombardment to secure surprise is based on OTL and proves as much of a failure as IOTL. I should mention that the Americans are about to enter the same sort of meat-grinder that the French experienced in the Battle of the Frontiers and the British experienced at the Somme. The Americans are not attacking a beaten and demoralised enemy, which will have immense consequences for the American experience of the Great War.

(4) This first day of the St Mihiel Offensive is not based on the course of events IOTL because the situation is very different from OTL. Here the Americans are attacking well prepared German defenders in some of the strongest defensive positions available along the front. The natural result is that it turns into an absolute bloodbath. I was a bit uncertain about casualty numbers, but the Americans actually take fewer losses than the British did at the Somme under similar circumstances. The extremely low German casualties are also based on an adaptation of the losses taken during the Somme offensive where the British attacked in much easier terrain. The casualties may seem shocking, but they are in line with what all the other powers experienced during their early offensives. The Americans are actually more receptive to changing approach than many of the other powers were under similar circumstances, ending the attack long enough to shift forces around to take into account the new situation.

(5) For those trying to keep track, since the start of the St Mihiel Offensive the Americans have taken around 220,000 casualties, around 25% of them killed - so 56,000 dead in the span of half a month, while the Germans take 60,000 casualties, of which around 15,000 are KIA or MIA. The reason these casualty rates are so lopsided is that the Americans are attacking strong positions by 1918 standards with 1914 methods. However, as can be seen the Americans are actually making important progress, incorporating tank tactics and improving their artillery bombardments quite a bit in a short time. Patton's thrust at Thiaucourt is also one of the major tank offensives of the war and leads to quite significant American interest in armored vehicles. The American casualties are going to be quite a shock to the American public once word starts to spread.

Charge of the Harlem Hellfighters at St Mihiel

A Hard Summer

By the beginning of the third week of the St Mihiel Offensive, both sides were starting to grow ragged under the intense pressure they faced. The Americans had been pushing forward through blood and mud and dirt for very little gain and had taken punishing casualties in return. Wave after wave had stormed forward only to be torn to shreds under the heavy German artillery which slammed down with barely any warning, the Germans having mapped out the entire salient in preparation for blind fire. In the air above, the German and American fighters had clashed in a thousand skirmishes and duels, with terrible losses on either side as neither could secure proper air superiority. While the Germans were experienced in this sort of fighting and were able to shelter in the countless well prepared bunkers and strongpoints that had been constructed across the salient, the Americans were left to press forward through the harsh terrain with little cover beyond what they could steal from the Germans.

Day and night the guns roared and men died. The bombardment and capture of Montsec had been a major success for the Americans, greatly strengthening their grip on the southern bank of the Rupt de Mad and allowing them to hold ground across the stream, however it cost them dearly in munitions. German counterattacks grew in scale and rapidity for two days, as they tried to recapture lost ground, but with the fall of St Mihiel and Montsec their positions on the Meuse heights were growing tenuous. Max Hoffmann and his staff at OHL wavered on whether to press forward to retake Montsec or to pull back from the heights and reduce the threat of German forces on the Heights being cut off. Since the end of the first week of the offensive, the Americans had seen little progress on the north-western section of the offensive atop the Meuse Heights. It was at this point, as OHL debated the merits of a retreat and the Americans prepared for an attempt at pinching off the Heights with a thrust by II and V Corps, that the call arrived from the Supreme Commander Ferdinand Foch demanding that the Americans take up their section for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive as Pershing had promised during the planning period in June (6).

During the planning of the Summer Offensives, when it was determined that the main focus of the offensives would center on the Champagne, The SWC had given Pershing the option of cancelling St-Mihiel but he went ahead with it in order to protect his flank, a trial by fire for his inexperienced army and as a morale booster. They also let him choose to attack west or east of the Argonne, whereof he chose the latter option because supplying his troops would be easier even though the terrain was harder. Indeed, the Wövre Plain behind the St Mihiel salient was much easier terrain than in the broken country of forests and ravines that characterised the lands between the unfordable Meuse and impenetrable woods of the Argonne Forest, and Pershing had initially held out hope for this to be the focus of the wider offensive. The plan had originally called for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive to begin in the first week of August concurrently with the French Champagne Offensive, but as the Battle of St Mihiel dragged on, this deadline seemed increasingly impossible amongst the Supreme Command.

Pressure mounted steadily for the Americans to either cut their losses or throw their last dice - but either way they would have to end the fighting in the salient as soon as possible and transfer their forces north to the coming battlefield. The AEF GHQ wavered back and forth over what to do, but in the end it would be Pershing's decision that decided the matter. The Americans would launch a final attack all-out assault. Drawing forces from around Thiaucourt and St Mihiel, the II and V Corps were reinforced and rejuvenated - all available reinforcements being pushed forward to these two corps - while artillery was moved forward to exploit the northern Meuse Heights and Montsec - which gave a great view of the lowlands along the Rupt de Mad towards the key towns of Nonsard and Vigneulles whose capture would cut off the Germans atop the Meuse Heights.

This final assault was launched on the 4th of August 1918 and made good progress on the first day. The Rupt de Mad was crossed almost everywhere and the American attackers moved forward under the cover of heavy artillery, though moving the American artillery forward had put them in range of the heavy guns atop the Meuse Heights, which now began performing counter-battery actions. The American assault from the north finally pushed the Germans off the northern Heights and led to a frenzied struggle over Vigneulles, with the Americans attacking in wave after wave. To the south the crossing of the stream forced German troops atop the Meuse Heights to turn their focus eastward, launching a counterassault on the Montsec position. Believing that holding the Meuse Heights was becoming too great of a challenge, Gallwitz began a staged retreat from the heights, transferring heavy artillery behind the frontlines in an incredibly risky operation, whereupon they were set up to the east of the fighting and began a harsh bombardment of the attackers. This was followed by medium artillery, before light artillery and men began slowly shifting across the front. The bitter fighting reached its climax on the fourth day of this attack, at the height of the evacuation of artillery, when Vigneulles fell to the Americans for the first time. Furious German counterattacks were launched to rebuild the German lines and the town switched occupiers six times in two days, while the line around Nonsard held firm.

Finally, the Americans brought the assault to an end a week after the renewed attack began on the 11th of August under strenuous objections as Foch demanded that Pershing end his attack. This week of fighting would cost both sides almost 100,000 casualties, the Germans having been forced to hold firm on the line and take the resultant punishment that resulted (7). This final bitter struggle had seen the Germans barely hold the road to the southern Meuse Heights open, and retained control of Nonsard, but they were in no position to defend the lands they now held in the long run. While the Americans rushed their forces northward to their section of the coming Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the Germans quietly pulled out of the Salient and into the section of the Hindenburg Line that had been constructed behind it in the 1916-1917 period, and transferred many of their units north along the line to Champagne where the French were about to begin their own offensive.

The French half of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was essentially a sideshow to the much larger Fourth Battle of Champagne that was undertaken across the long and flat piece of land under German occupation south of the Aisne, primarily held by forces from Army Group Deutscher Kronprinz. The battle stretched from the Aisne around Soissons, through Champagne around Reims and from there all the way to the upper Aisne where the river turned south through the front again. The French goal would be to press the Germans back through the lands of Champagne until they stood with their backs to the Aisne from Soissons to the Argonne, with Rethel as the objective of the attack, in order to secure the vital supply lines running through Soissons and Reims to the battlefields further east. The Americans in the meanwhile were to be locked between the two rivers of the upper Aisne and the Meuse. This was an exceptionally exposed sector of the front, where the Germans would enfilade them with artillery from both flanks once the Americans advanced, at least until the French took the lands along the Aisne. At the same time they would be attacking into well-built lines of defence in depth, most notably the Kriemhilde Stellung, part of the Hindenburg Line, on a ridge some ten miles from the American positions at the start of the offensive. Pershing was gambling on taking this position on the second day, before the Germans could reinforce it, by taking advantage of the ongoing struggle further west.

However the rushed transfer of the First Army from St Mihiel gave its Chief of Staff, Colonel George C. Marshall, little time to prepare. Starting the attack barely weeks after St Mihiel proved an incredible strain on both the soldiery and logistical framework. Only three rutted roads crossed the sixty miles between the two battlefields, over which 400,000 men had to be moved, all journeys taking place at night and against the sinister backdrop of the old Verdun killing grounds. In addition, and to save time, many poorly trained and completely inexperienced troops would participate, often rushed directly from their training camps due to the incredible manpower losses experienced at St Mihiel. Pershing hoped to prevail by weight of numbers, and he enjoyed a superiority of nearly four to one on the opening day; but although he committed 600,000 men on the opening day they had fewer tanks than at St-Mihiel and half the numbers of aircraft.

The delays caused by the American unwillingness to abandon the field at St Mihiel finally forced the French into action on the 14th of August, already a week behind schedule due to American delays at St Mihiel. Their assault rushed forward across the sector and was the largest French offensive of the war, using the most modern military tactics available to them and lessons learned from the German assault and burning through munitions like a madman. The Fourth Battle of Champagne was the fiercest and most intense struggle between French and German soldiery since the meatgrinder at Verdun and saw both sides throw everything into the struggle. The French launched major assaults with their heavy and light tanks, dwarfing Patton's assault at St Mihiel. while the sky was blackened with aerial vehicles of unprecedented numbers. The ground shook as far away as Paris from the intensity of the barrages and counter-barrages as everything was thrown into the struggle. In the two weeks before the Americans were able to launch their attack the Germans were forced slowly but inexorably backwards, leaving behind graveyards by the minute (8). The French would swiftly begin to experience munitions shortages, and as a result found themselves reduced to begging for British support, resulting in the redirection of considerable British munitions to support the French and American military efforts, now that their own forces were unable to participate in the fighting. This would ease the pressure, but both the French and American forces would deal with consistent shortages throughout the struggle.

The American First Army would attack on a 24-mile front, stretching from the west side of the Argonne Forest to the River Meuse. Next to the French Fourth Army, which was already advancing on their left along the Aisne, were the bloodied I and V Corps in the centre and the fresh III Corps on the right. The assault divisions would advance supported by a barrage fired by nearly 2,700 guns. Pershing was aware of the danger of rapid German reinforcements, so he planned for an advance of 10 miles to overwhelm the Kriemhilde Stellung within the first day; this was ambitious in the extreme and demanded the near-immediate capture of the imposing Montfaucon Hill position, which rose over 250 feet above the surrounding terrain. One further problem facing Pershing was that several of his most practised divisions, the 1st, 2nd, 42nd and 89th, had been ground down in in the bloody St Mihiel offensive and had to be left in the rear to recover. This meant that the initial Meuse-Argonne assault would have to be made by far less experienced troops.

Pershing was conscious of the inexperience of his divisions, and saw his role as driving them on, while monitoring the command performance of his generals to ensure that they demonstrated sufficient vigour. Of sophisticated tactics he knew little; all his divisions would advance forward at the same Zero Hour, 05.30 A.M. on the 30th of August, charged with overcoming whatever got in their way. There was no subtlety, just the vigorous application of brute force. The Argonne Forest was an obvious problem as it was a terrifying prospect for any troops. A wild, almost mountainous terrain, some 6 miles wide and 22 miles long, impenetrable by tanks and tailor-made for defence, with a jumble of high jagged ridges, deep ravines and swamp-lands, shrouded by forest and tangled undergrowth. The obstacles of nature were trumped by a lethal concoction of concealed trenches, concrete machine-gun posts and masses of barbed wire. Although the trees had been thinned out around the front-line trenches, further back, where the gun lines would be, the ridges were still heavily wooded. Tracks had to be hacked out to manhandle the guns into position and this was just the start of the hard labour. There was also the need to clear a field of fire for the guns themselves, which proved to be no easy matter. For two days, the sound of saws and axes rang through the woods. Every tree which in any way obstructed the passage of shells was cut through so far that a few more strokes would bring it down (9).

All along the ridge where the artillery was massed, the trees which furnished such perfect concealment before the battle were to be demolished. The racket this produced led to German scouting forces, already on edge from the fighting further to the west, moving forward steadily where they discovered the American preparations and sent back warnings to the headquarters of General Friedrich Sixt von Arnim, commander of the recently transfered Fourth Army, who sent the warning on to his neighbour to the east Georg von der Marwitz, who had recently been given command of the Fifth Army, and their Army Group Commander Max von Gallwitz. Having secured permission to engage, von Arnim's men snuck artillery forward into preprepared positions closer to the American lines and launched a hellish bombardment mid-day on the 28th aimed at the heights. The sudden heavy bombardment killed and wounded several hundred men amongst the artillerists and forced them to pull back behind the ridge for cover. Thus, as the American divisions moved into the line on the night of the 29th, many of them having been issued with totally unfamiliar grenades and pyrotechnics, a spirited debate engulfed the American GHQ. Concluding that a surprise assault was now off the table, they eventually decided to simply use their larger weight of numbers and massive artillery contingents to press forward (10). By 30th of August the Americans were finally ready to attack in the Meuse-Argonne region.

Footnotes:

(6) The Americans are very close to cutting off the Germans atop the southernmost parts of the Meuse Heights and have most of the northern heights under control. If they could push north from Montsec and south from the Meuse Heights, capturing Nonsard and Vigneulles, they would be able to trap upwards of 50,000 men. However, the French need American support in the Meuse-Argonne and can't wait much longer. They need to end the war as soon as possible if they are to keep their prominent position in the world and keep their country stable.

(7) The Americans finally succeed in putting the Germans into a position where they are forced to pull out of the St Mihiel Salient, but at what cost. Over the course of the slightly-less than month-long period that constitutes the Battle of St Mihiel the Americans suffer almost 320,000 casualties, 80,000 give or take dead. The exchange rate between American and German casualties improves immeasurably in this last attack, reaching near parity, because the Germans are forced to hold their ground and launch counterattack after counterattack rather than just bombarding the Americans from afar and then butchering them when they finally get into range, falling back when threatened and counterattacking with overwhelming force. This is something we see multiple times in other battles IOTL - when a force is forced to stand its ground it takes a lot more casualties. That said, there is no doubt that the Americans got more than they bargained for and that their combat effectiveness has been severely impacted for the time being.

(8) This is really the last, best toss of the dice on the part of the French. They are throwing everyone and their kitchen sink at the Germans and are finally making significant gains. However, the French and Americans are both draining the same pool of munitions from Paris which, as has been previously detailed, is a far more finite resource than it has previously been. The Germans are giving as good as they are getting, but they are outnumbered by quite a bit and are on the defensive. Luckily they aren't forced to fight for their positions to the bitter end as happened at St Mihiel at the end, but can pull back when needed. The question for them is whether, when the French begin to press them against the Aisne River, they can successfully cross over it without suffering catastrophic casualties or giving in to panic. The Fourth Battle of Champagne is actually happening in an area that has seen relatively little fighting previously ironically, with the vast majority of the fighting during the Great War having focused at the western edge of the battlefield around Soissons.

(9) This is based on OTL descriptions of the Argonne battlefield. It is quite literally one of the hardest places to attack along the entire front - far more so than the St Mihiel Salient. The complexities explained are also based entirely on OTL. Ever since I read up on the sort of battlefield the Americans were going to attack and the conditions under which they did so I have marvelled at how cheaply they ended up paying for it IOTL. IOTL they were attacking as part of a series of concentric assaults in Flanders and Champagne meant to cut off the massive salient that was formed by the German controlled areas. However, without Flanders this is not possible and the Allies are left to attack from one side only. That said, the Allies are making progress but it is at a far greater cost than IOTL, where they were fighting German soldiers who were convinced they had already lost the war. Here spirits remain high in the German camp and while the fighting in Champagne and in the Aisne region is putting immense pressure on them they are convinced that if they can just hold out long enough then the Allies will crack under the pressure.

(10) The Germans moved the Fourth Army south from Flanders and slotted it in where they thought the assault was most likely to hit in late-June and the men there have spent the period since acclimatising to their new positions and getting to know the lay of the land. This means that there are more troops on the ground when the Americans attack, though they are still outnumbered by quite a bit due to the great demands for manpower in the Aisne sector to the west. This means that there are more men moving about who could discover the hurried American preparations with relative ease. IOTL the Americans thought the fact they were able to clear the ridge uncontested a minor miracle, where ITTL they get just that bit more unlucky and their preferred artillery positions are bombarded before they can even begin. However, the most important effect on the discovery of the American preparations is that the Americans now fear that they will be forced through a meat-grinder like St Mihiel again and see little option than to just press on into it. There isn't much else they can do now that they are committed.

U.S. Marines in the Argonne Forest

Bloody Splinters

Having lost the element of surprise, the Americans proceeded with a massive 18-hour bombardment on the 30th of August, hampered by their inability to use the cleared ridge for the first half of the bombardment and their need to clear the hidden German artillery which conducted a counter-battery fire for the first third of the bombardment. The air grew alive with whistling shrieks while on the high ground in front of the American lines the shock of explosions merged into one deep concussion that rocked the walls of their dugouts. Everywhere the ground rose into bare pinnacles and ridges, or descended into bottomless chasms, half filled with rusted tangles of wire. Deep, half-ruined trenches appeared without system or sequence, usually impossible of crossing, bare splintered trees, occasional derelict skeletons of men, thickets of gorse, and everywhere the piles of rusted wire.

When the Americans finally went over the top on at mid-day on the 31st of August, having fired more than four time the amount of shells fired during the entire American Civil War, they entered a deserted hell-scape of bone-white, splintered trees and massive craters. They faced little resistance as they crossed the first German lines but encountered hard resistance as soon as they reached the outskirts of their own artillery's range, coming under intense German bombardment and running into fiercely contested defensive positions. The hardest fighting of the first day centered on the towns of Varennes and Malancourt, with the latter finding itself under artillery cover from atop the heights of the fortified hill at Montfaucon. As the Americans slowly moved their artillery forward to continue covering their men, the American infantry threw itself onto the German defenses with uncommon vigor. Hammering headlong against the defenses at Malancourt and Varrenes, the Americans were finally able to break through at the end of the first day at the former site - now facing the imposing heights of the increasingly reinforced Montfaucon hill which prevented any forward progress and allowed the Germans to pinpoint Allied movements for their artillery. At Varennes the Germans were able to hold the Americans back until the end of the day, losing possession of the town in fierce dawn attacks on the 1st of September.

However, while the capture of Varennes was a significant accomplishment, it would be the failure to take the high ground at Montfaucon that would dominate the minds of the American leadership. On the morning of 1st September, the III Corps threw itself forward against Montfaucon with as many bodies as they could muster. Assault after assault was undertaken, broken only by periods of heavy American bombardment of the hill, but no matter how often they attacked there was little the Americans could do to dislodge the defenders who fought back with incredible ferocity, burning through their machine-gun and rifle ammunition at an incredible pace while going toe-to-toe in close-quarters combat with the much larger and healthier Americans when the remnants of an attack reached their positions atop Montfaucon. Throughout this assault by the III Corps, it found itself under incredibly heavy bombardment by German artillery across the Meuse, firing from atop the infamous heights which the Americans had already fought for farther to the south at St Mihiel.

The III Corps eventually found itself forced to ask for aid from GHQ, who threw forward the newly formed VI Corps to strengthen the III's attack. The VI would arrive at Montfaucon on the 2nd and joined in the assault here, rushing forward again as they had the day before. However, it was at this point that the intense fighting of the previous day and the massive expenditure in ammunitions that defence had required finally caught up with the German defenders. Having fought off three attacks before noon, the German commander eventually determined that they would have to pull back and resupply, securing permission from Fourth Army GHQ to retreat after blowing up the defensive positions atop the hill with what explosive were at hand. Having taken Montfaucon, the Americans soon discovered that they had only just begun the struggle they faced. Behind Montfaucon were two hills just as formidable, at Nantillois and Cierges. The intense fighting of the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive would amount to casualties of around 4:1 for the Americans, who took around 40,000 casualties while inflicting some 10,000 on the Germans by the end of the 3rd of September (11).

Despite the intensity of the fighting in the Argonne Forest and its surroundings, everything paled in comparison to the titanic clashes occurring in Champagne where almost 3,000,000 men from ten separate armies clashed across a front almost 100 kilometres long. Overseen by both Ferdinand Foch and Phillip Pétain, actual command of the French Armies was split between Army Group North under General Louis Franchet d'Esperey, commanding the Tenth, Sixth and Ninth Armies, and Army Group Center under General Paul André Maistre, commanding the Fifth and Fourth Armies, while General Marie Émilie Fayolle remained in reserve with around 20 divisions. The Germans, on the other hand, were all grouped together in the massive Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz consisting of the Ninth, Seventh, First, Ninteenth and Third Armies under the official supreme command of Crown Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern, though in truth it was his Chief of Staff Fritz von Lossberg who actually directed the defensive efforts.

Lossberg had long been the German secret weapon on the Western Front, being shuttled from crisis point to crisis point in order to hold the line, and had already fought in the Champagne once, in 1915 during the Second Battle of Champagne. Throughout the intense fighting south of the Aisne, Lossberg kept his labor batallions busy expanding the already complex defenses behind the Aisne in order to ensure that even if the Germans were pushed across the river, they would have somewhere to shelter from the onslaught. The sheer scale of the fighting in Champagne stunned observers and drew the eyes of the world to the region. Having noticed the massive buildup in preparation to the French offensive, Lossberg and his subordinates had worked hard to prepare for the coming storm and were more than ready for the attack when it finally came, almost two weeks behind schedule.

The battle-lines of the Fourth Battle of Champagne spanned a distance not truly seen on the Western Front since 1914, including the battlefields of all previous Battles of Champagne, from around Soissons and the Chemins des Dames which had been the focus of the Nivelles Offensive and around Reims where the First Battle of Champagne had been fought, to the fields east of Reims where the Second Battle of Champagne had been fought. The French were thus moving through the detritus of their previous failures, the weight of which pressed down on the soldiers as they moved to the front (12).

When the French finally attacked on the 14th of August, they were able to make considerable progress by any standard other than that set by the Germans during the Spring. While major tank assaults at multiple points along the line were able to press through the first several lines, attrition remained extremely high. Artillery on both sides fired anything and everything they could get their hands on, raining deadly clouds of gas, shrapnel and high explosives in unprecedented measures. Tens of thousands died in countless assaults and desperate defenses. Attack was met with immediate counterattack, only to be swept back again, some positions changing hands as many as sixteen times in the span of a couple weeks. By the time the Americans finally got under way in the Argonne, both the French and German commanders were fighting across a desolate wasteland. The bloody cut and thrust continued as the Germans were slowly pressed backwards, selling every foot with an ocean of blood, both sides knowing that this was likely the most important action of their lives.

By the third week of fighting, on the 6th of September, the Frontline had shrunk to 60 kilometres and the soldiers fighting found themselves increasingly cheek-to-jowl. Lossberg, judging that the line behind the Aisne was nearing the point at which it would be able to hold the French, ordered the slow transfer of men back north, across the Aisne. Against expectations, this action had little negative impact on the German combat performance, as the increasing concentration of German troops on the ever-narrowing front had led to a rapid rise in artillery casualties on both sides, though the reduced number of Germans south of the river did allow the French to increase the pressure of their assault even further. However, as the French pressed further into the funnel of the Aisne's southern banks, the Germans were able to begin a mighty crossfire from behind the river's defences which served to put ever growing pressure on the French flanks, though this threat would be somewhat mitigated by the American Argonne Offensive, as it forced the redirection of German artillery power southward to counter them along the eastern end of the conflict in Champagne (13).

In the days since American troops of I Corps had taken Varennes, they had found themselves scrambling for control of the Apremont heights to its north. The incredibly harsh terrain, strong defensive positions and the difficulty of bringing forward sufficient artillery support turned this area into an unmitigated bloodbath. Tens of thousands of men threw themselves forward with wild abandon, slowly tearing down the German resistance in intense close quarters engagements that sapped American and German strength like nothing else. Finally, on the 8th of September 1918, the 77th Division of I Corps successfully overran the German positions at Apremont in spite of heavy casualties and close quarters, lines of sight often extending little farther than a couple meters in the heavy brush. However, the capture of Apremont would be the last major American success on the western edge of the Meuse-Argonne struggle for quite a while, the initiative returning to the III and V Corps in the east.

Here, the Americans threw everything they could at the defensive positions atop Nantillois and Cierges with scant regard for the cost. Assaults were launched day and night, sometimes as many as six times a day, with heavy casualties inn every attack. However, the constant assault would have much the same effect as at Montfaucon, grinding down German capabilities over several days, before finally capturing the heights after a week of constant charges, on the 13th of September. Behind Nantillois and Cierges, the Argonne opened up into a heavily forested valley all the way east to the Meuse, which greatly improved American progress but brought them even further under the guns of the German artillery atop the Meuse Heights. The bombardment was constant and grinding, greatly disrupting resupply of frontline troops, with many of the Americans having already been extremely low on food by the last day of attacks on Nantillois and Cierges. By the time the Americans were halted at Bayonville on the 20th of September, they had been completely ground down by extreme casualty levels, extremely lacking resupply, exhaustion, constant bombardment and minimal artillery support, which had been prevented from pushing forward with the forces of either corps into the valley by intense German counter-barrages from atop the Meuse Heights.

It would take another week before the much slower advance in the west came to a halt at Grandpré for similar reasons. In the three weeks following the capture of Montfaucon the Americans had taken more than 250,000 casualties in their continual rush forward, driving forward newly arrived recruits, who were thrown into battle with little preparation to keep the advance going. However, after four weeks of constant assault, preceded by barely more than a week of rushed redeployment and another month of near-constant fighting at St Mihiel, the Americans found themselves ground to a nub, exhaustion, supply shortages and casualty rates forcing them to a halt. In return the Germans had taken around 90,000 casualties, mostly due to their strong defensive positions, the availability of artillery on the Meuse Heights and American inexperience. Although desultory fighting would continue for another week, the Americans finally called an end to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on the 30th of September 1918 (14).

The Fourth Battle of Champagne reached its high point for the French in a crescendoing climax on the 17th of September, when the French Sixth Army finally broke through the German lines at Saint Loup following more than three days of intensive fighting, sending the German Ninth and Seventh Armies scrambling across the Aisne River and forcing General Lossberg to speed up the German retreat across the river, leaving them to abandon what supplies remained south of the river. While the French Tenth and Sixth thus pushed to the Aisne River by the 20th, it would take half a week longer before the three other armies were able to push their German counterparts across the Aisne. Particularly intense German defences at Sault-lès-Rethel, Seuil and Attigny allowed them to shield the crossing of the three laggard German armies, though casualties had by this point crossed a combined 800,000 between the two combatants and more than 40,000 Germans had been caught against the Aisne River and forced to surrender.

While both sides used a short break of a couple days to realign to their new positions, bring up more supplies and readying for the continuation of the Battle of Champagne, the Germans found themselves near the end of their rope, uncertain if they would be able to hold this new line. When the French assault restarted on the 26th of September they did so with a series of attempted crossing of the Aisne, mostly in the western and central portions of the front, though a single crossing was attempted against the rear of the German defenders in the Meuse-Argonne where they quickly floundered in the face of intense bombardments and the incredibly harsh terrain.

At the center of the fighting was the city of Rethel, which the genius of Lossberg had turned into a fortified nightmare for the attacking French. Despite harshly contested crossings on either side of the Rethel, it would be the direct assault on the city itself that would come to be remembered in history. More than 200,000 men were concentrated within the field of battle at Rethel, struggling across the Aisne River only to enter into a well prepared urban environment in which every building had been turned into a strongpoint and any window or doorway promised death to the attackers. Roads were blocked off while holes had been blown in buildings to remake the entire city map to the benefit of the defender. The sewers were turned into tunnels and bunkers for the defenders while mines were scattered in areas where the French would be forced to attack. While other thrusts over the river were either beaten back immediately or eventually contained and turned back by fierce counterattacks, the French would cling to what neighbourhoods of Rethel they could secure despite serious supply shortages, with most of their artillery batteries reduced to a tenth of their ordinary daily combat munitions usage, and several instances of batteries running out of munitions completely, this playing a key role in defeating most of the river crossings. More and more men had been sent into the nightmarish hell of Rethel's urban landscape, but the French attackers were eventually forced to a halt within the confines of the city on the 9th of October 1918. Efforts at sending further men forward met with localised resistance by the French soldiery, and Pétain, worried that any more pressure would result in a collapse, called a halt to the offensive.

Continual German bombardment of the French positions in Rethel would eventually forced the French to cross back over the Aisne on the 21st of October. The nearly two months of fighting would cost the French 700,000 casualties while the Germans would get away with 650,000 including those captured south of the river. Thus, by the middle of October neither side seemed any closer to winning the war than in previous years, but had been bled horribly. The incredible hope surrounding the American entry into the war, particularly in France, had been drowned in blood, and it was becoming increasingly clear to both the army leaderships and the people on the home front that the war might drag on for several years more. Despair gripped the peoples of the world and the once quiescent peace movements grew ever louder (15).

Footnotes:

(11) Much of the fighting outlined ITTL is actually pretty close to the OTL with the key difference that the Germans hold their positions slightly better and there aren't morale collapses as IOTL, again because of stronger German morale resulting from avoiding the many pointless follow-on offensives during the Spring and early Summer. IOTL the combined casualties of the two sides came out to around 200,000 (122,000 American) to 120,000 in German favour, however of the German casualties more than half were POWs, half of those surrendering to the French, and the weight of German losses coming to the French. With the French section of the fighting considered part of the wider Fourth Battle of Champagne, that leaves only the American contribution counted. Again, the Americans were attacking into some of the harshest terrain possible with what amounts to an army of raw recruits. It was never going to be pretty. It also bears comparing to the St Mihiel Offensive of TTL, where there were a lot more early casualties. This time around, the Americans have learned some lessons and their soldiery is better able to push forward while remaining under cover. It also helps that the terrain greatly reduces the effectiveness of the artillery bombardments of either side, making it a more survivable ordeal.

(12) IOTL Ferdinand Foch was a major proponent of the great offensive, where France would throw everything in a basket and press forward with everything they could - similar to the approach taken by Nivelle the year before. Now IOTL he was able to leverage multiple battlefields at diametrically opposite points along the line to put ever greater pressure on the Germans in a series of large battles that battered them down from all sides. However, ITTL the loss of Flanders and current incapacity of the British means that he is unable to do this and is left with his original idea, a single massive attack in the Champagne region. Pétain was extremely leery of launching such an assault IOTL, having had to deal with the aftermath of the Nivelle Offensive, but France needs a major victory to outweigh the loss of Flanders as soon as possible and as such they have little choice but to follow through. The two sides are able to martial around 1.5 million men each and go at it with wild abandon. The numbers are based on what the French were able to muster for the Hundred Days Offensive IOTL with the caveat that they also have other responsibilities in Italy, on the Oise and in Lorraine to contend with. The Germans have a lot of soldiers who died in the Spring Offensives IOTL alive, many of whom are among the best men they have available who help bolster the general fighting abilities of the others, as well as men from Flanders and the East. By the way, the armies listed as participating are mentioned according to their positions from west to east.

(13) By the 6th of September, the frontline runs from Évergnicourt to Falaise, both on the Aisne. The French are making good progress and are actually winning this struggle so far, though the Germans haven't collapsed or anything like that. With Lossberg in charge, there should be a pretty good chance of the Germans being able to make it across the Aisne River to their positions once the time comes for that. Right now the Germans are working to make the river as difficult to cross as possible and preparing for the destruction of any bridges and fords - blowing them up or otherwise crippling them as they pull back.

(14) For those keeping track, the Americans thus take 290,000 casualties in the Meuse-Argonne to 100,000 German casualties, which matches up pretty closely with the OTL loss ratios during the OTL Meuse-Argonne Offensive. However, the result is that in the first three months of fighting on the Western Front the Americans have taken 630,000 casualties - around 160,000 dead - to a combined 260,000 casualties for the Germans, around 65,000 dead. Furthermore, the Americans are unable to break out of the Argonne Forest, and as such the frontlines are now stuck in this harsh terrain, hard to supply but imminently defensible.

(15) By this point, 1918 has been the deadliest year of the war on the western front and there seems no end in sight. The Germans were able to greatly improve their positions in Flanders and knock the British out of the conflict for several months, but as we get closer to 1919 the British will begin to have a presence on the field of battle once more. The French gave their last, best gamble in Champagne and while it saw considerable success in pushing back the Germans to the Aisne, they were unable to defeat the Germans and can now expect their military capabilities to fall steadily as the conflict progresses, losing ever more influence to the British and Americans. The Americans, in the meanwhile, have gotten one hell of a wakeup call in the form of more than half a million casualties. They are already calling up more men by the hundreds of thousands for conscription, but the sheer scale of the fighting is finally beginning to make itself felt in America.

Allied Soldiers in a Hospital Ward Suffering From The Great Flu

The Aftermath

While the most obvious killer during the Great War was the brutality of iron, lead and gunpowder that reaped lives by the hundreds of thousands, it would be a series of deadly flu pandemics that tore across the world from late 1917 to 1919 which took the greatest number of lives. Emerging in American Army Camps in Kansas, the first instance of the flu was quickly spread across the world along the lines of supply stretching all the way to Europe. On 4th March 1918, company cook Albert Gitchell reported sick at Fort Riley, an American military facility in Kansas that at the time was training American troops in preparation for the Great War, making him the first recorded victim of the flu. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. By 11th March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York. On arriving alongside American troops, the disease quickly began to spread in the overcrowded camps and hospitals of western France. During this period, the disease jumped from person to person and was soon part of a deadly cargo carried by Allies soldiers and sailors wherever they went.

It was in this way that the disease would eventually reach the rest of the world, following the shipments of Latin American troops back over the Atlantic while joining the crews of ships sailing south towards the Cape of Good Hope. While the disease's first mutation was but a harsher than usual flu, with a relatively modest casualty rate, as the year moved forward and the weather grew warmer, the disease began to transform. During June and July, the Germans would experience considerable difficulties as tens of thousands went down with the flu - the disease having been transferred during the capture of Flanders. As the disease tore through the German lines, they saw their manpower shrink considerably, though this first wave of the flu would not prove particularly deadly, even when it spread amongst the weakened populace on the home front.

In August of 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France; in Freetown, Sierra Leone; and the United States in Boston, Massachusetts. While this strain tore through West Africa, South Africa and eventually India, it would take almost two months before it really got a grip on the soldiers at the front. When it did, it started amongst the hundreds of thousands of Allied Soldiers who were wounded between the middle of July and October. This second, deadly, strain of the disease saw the highest mortality rates amongst those ages between 15 and 35 and hit the Allied armies like a brick to the head as the French were trying to cross the Aisne and the Americans were preparing for another push in the Argonne. As reinforcements collapsed on the march to the battlefield and men were forced kicking and screaming in terror to their hospital beds, the Allies found themselves pressed to call a halt to the proceedings.

While the disease crossed the line in this period, German efforts at quarantining frontline soldiers would see considerable success, greatly reducing its spread outside the frontlines for much of 1918. Hospitalization would come to be viewed as a death sentence by many allied soldiers - a belief particularly rife amongst the American soldiers, who were dying by the tens of thousands in their hospital beds from the disease. The combination of mass casualties, close quarters and the murderous disease would have a horrific effect on the likelihood of recovery for many wounded soldiers. However, the sheer scale of the pandemic would not allow the Germans to hold it at bay forever, and by early-December it had begun to spread through the cities of western Germany (16).

While the American public and civilian government had done what they could to prepare for the realities of war, they were by no means prepared for the sheer scale of the cost and the sacrifice that would be required to bring the war to a close. As the American government had begun contemplating declaring war on Germany in 1915, officials had been mindful of the great cost to the state of pensions for sick and disabled veterans from the American Civil War. By 1915 virtually all Civil War veterans were receiving a federal pension. To avoid a similar burden on the U.S. Treasury, the War Department engaged in an unprecedented examination of 10 million recruits to screen out medical liabilities and build the strongest and most fit Army, Navy, and Marine Corps.

The medical toll was great nonetheless. American losses began before troops could even fight in France. As medical screening revealed men with serious problems requiring treatment, such as sexually transmitted diseases, malnourishment, respiratory diseases, or dental infections, trainees began to flood Army hospitals in the fall of 1917. Measles and mumps epidemics also appeared in several training camps, and some unfortunate men who developed lethal pneumonia from those diseases went home in caskets just weeks after enlistment. To care for these men and avoid a legacy of veterans’ pensions, Congress passed an unprecedented package of benefits for military personnel and their families.

The War Risk Insurance Act of 1917 provided family allotments of soldiers’ pay to replace the loss of the breadwinner; automatic compensation for death and disability; additional, optional, government subsidised life insurance of 10,000 dollars per soldier; and medical care in government hospitals. Congress authorised the American Red Cross to organise fifty base hospitals from leading universities and civilian hospitals and recruit nurses for the military while the American Medical Association helped recruit thousands of civilian physicians to serve, so that during the war almost 35% of American physicians were in the military (17). The Army Medical Department ultimately numbered 36,000 medical officers, 28,000 nurses, and 300,000 enlisted men. The Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery had some 35,000 medical officers, 2,000 nurses, and 15,000 enlisted men. By November 1918 the Army Medical Department had increased its hospital capacity from 9,500 beds to 120,000 beds in the United States and to 300,000 beds in Europe with the AEF. The AEF developed three levels of hospital care, with mobile medical units near the front lines for triage and treatment of minor injuries, fixed hospitals and convalescent camps in the rear for more serious wounds and illnesses, and a third tier of general hospitals in the United States for longer-term care. Both the home front and AEF systems included specialized hospitals for orthopedic injuries, shell shock, blinding injuries, gas victims, and soldiers who developed active tuberculosis (17).

However, even these preparations were nowhere near enough for what was needed. By early October, there were less than a third of the hospital beds required, a ratio that would only grow as the conflict went on. Additionally, the sheer cost of modern warfare was quickly becoming apparent, with over 720 million dollars worth of munitions having been used solely for the 48-hour bombardment that preceded the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Furthermore, at this point the government had already promised at a minimum 1.6 billion dollars in war risk insurance, with the number likely to grow even greater as the Flu took its toll. The sheer cost shook America to the core. However, rather than shy from the contest, they would react as so many other populaces on experiencing the initial shock of modern combat. They leaned in.

Although War Bonds and Liberty Bonds took a major hammering in August, as the first rumours of extremely high casualties began to make the rounds, and forced the Wilson Government to temporarily shut down the New York Stock Exchange, war fever would begin to grip the population as word of French and American successes during August began to make the rounds, and money flooded back into the bonds. Nationalist propaganda was pushed into high gear, with increasingly shrill denunciations of pacifists, anarchists and socialists, soon to be joined by communists, while the two major parties manoeuvred for control of the media narrative going into the mid-term elections. T

he Republicans in particular would use the reports of high casualty rates to reopen their efforts at establishing a Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Pressure mounted as the Republicans took an increasingly jingoistic tone, portraying Wilson as a bungling ivory tower intellectual with little understanding of the proper conduct of the war, most prominently in Theodore Roosevelt's numerous speeches during this period. Wilson's Democratic allies would find themselves constantly hounded through August and September, as news of greater and greater numbers of dead and wounded were blared from the headlines of Republican-aligned newspapers. In a quandry, and fearing that their resistance to the Joint Committee would undermine their hopes of reelection, the Democrats finally caved in early October. There was little Wilson could do, as the House and Senate appointed men to the committee, led by Democratic Senator George E. Chamberlain and Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, united in their efforts at reducing Wilson's control of the war in favour of the United States Congress (18).

Footnotes:

(16) The Spanish Flu finally enters the story and sets about wreaking havoc on the war plans of all sides. There are a couple of things to note here. IOTL Ludendorff began complaining about the morale effect on his offensives of the first wave of the flu in mid-late June, but ITTL the shortened Spring Offensive means that the first, and milder, wave of the flu hits the German lines during a period of consolidation and troop transfers rather than in the midst of an offensive. This allows the Germans to better treat the symptoms and spreads the first wave of the flu pretty far and wide into the German countryside. This is incredibly important because exposure to the first version of the flu helped reduce the lethality of the second wave, which was the one that hit the Germans IOTL just as the Hundred Days Offensive came under way. There are still plenty of soldiers incapacitated by the disease and a good number of dead, but Germany avoids getting hit on quite the same scale by the flu as IOTL. This plays into the second wave, which ITTL hits the Allies more than Germany (this is the opposite to what happened IOTL) for several key reasons. First of all, the second wave of the flu originates amongst the Allies as IOTL and hits them first, but importantly - the fact that you don't have anywhere close to as much movement in the open means that there is much less direct contact between German and Allied forces. Furthermore, the mass casualties taken by the Americans and the constant arrival of fresh troops from America means that there are a lot of people, highly susceptible to the disease, who get exposed to it. Having to treat the flu while also dealing with more than 600,000 battlefield casualties means that the medical staff is much more stretched than IOTL and as a result the disease reaps a much greater harvest. Perhaps most importantly, the German Army isn't demobilised in the middle of the pandemic, and as such don't bring it home with them - greatly reducing the spread of the disease in Germany and allowing for relatively effective quarantine methods. With the disease tearing through their armies and home fronts the Allies are forced to halt operations.

(17) The only real difference from OTL here is that the Americans end up with 35% rather than 30% of their civilian medical professionals in the army, for which the rest of the numbers have been adjusted. The American government really did all it could to try and resolve the issues they could expect to face before hand and IOTL mostly secured everything they would need. It is part of why the Great War had such a limited impact on the American psyche, they were able to resolve a lot of the issues they were facing with relative ease. However, that was predicated on their OTL casualty levels, which have already been dwarfed ITTL. As I outline in the next section, this is a scale at which the Americans simply weren't ready to act.

(18) This again is a pretty significant divergence from OTL which places Wilson's control of the American War and Peace efforts in question. As has been outlined earlier, Wilson's handling of the war was by no means popular IOTL and he faced considerable congressional opposition on a whole host of issues. IOTL he was able to push them aside and preside over affairs until Henry Cabot Lodge was able to torpedo the League of Nations, but ITTL events take a different course and Congress is able to encroach on the war effort. Whether this will turn out to be a positive or negative development you will have to wait to see.

Summary:

The United States First Army launches the St Mihiel Offensive, resulting in a bloodbath.

The Battle of St Mihiel comes to an end while the French prepare for an offensive in Champagne and the Americans prepare in the Meuse-Argonne.

The Allies make major headway in the Fourth Battle of Champagne and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, but are eventually fought to a halt by the Germans.

While a deadly flu pandemic tears through the world's population, America recons with the cost of its participation in the Great War and increases Congressional oversight in response to these failures and doubles down on the war effort.

End Note:

I am sorry to keep harping on about it, but I honestly can't imagine the American offensives in 1918, happening under the circumstances I have outlined, as being anything other than a disaster for the first year or so. These are their OTL battlefields and I have tried as much as possible to use numbers that match OTL with due consideration to the changes in morale, resources and training. The simple fact of the matter is that the Americans got through their parts of the Great War much easier than they would have against an enemy who thought they might win. The German armies were collapsing in on themselves, with mass desertions on an unprecedented scale accompanied by mutinies and a host of other issues. However, all of this ties back to Ludendorff's complete mismanagement of the Spring Offensives and his inability to bring them to a close before casualties reached critical levels. With a relatively swift victory in Flanders, and most of two months to recover afterwards and bask in their glory, the German soldiers are in a much better position to hold the line. Even then, they took casualties at a rate far higher than any of the other powers at the time.

One of the thing I haven’t been able to work into this update but which should be mentioned is that neither Manfred von Richthofen and his brother Lothar, nor Quentin Roosevelt, Teddy Roosevelt’s youngest son, are killed in the fighting in this period and all three will live to see the post-Great War era. They are thus in place to influence those events.

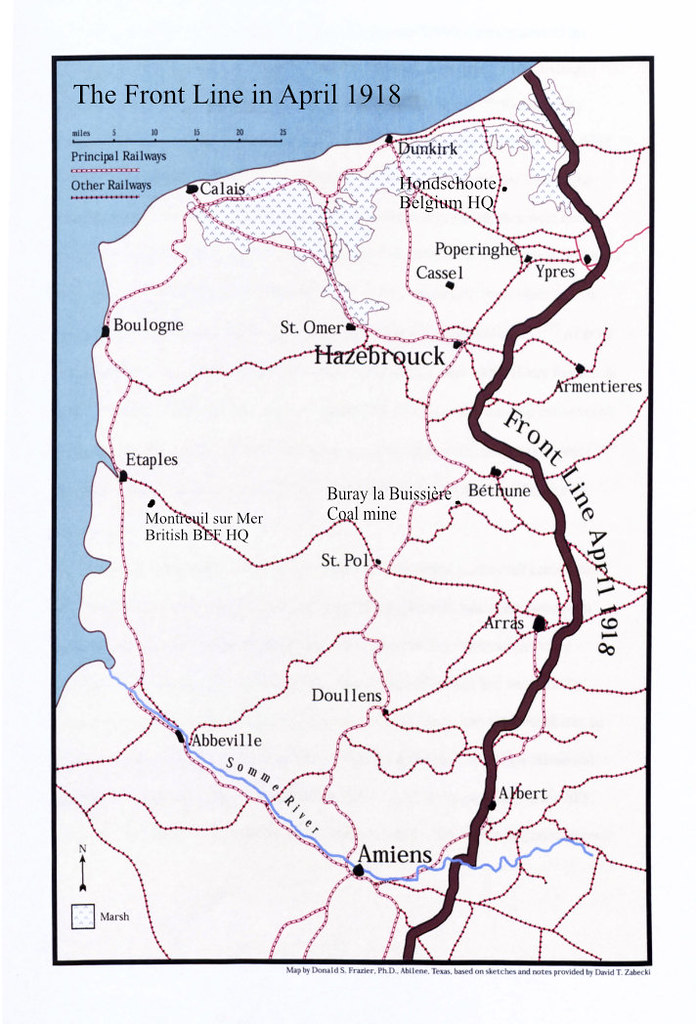

Here is a map of the OTL Meuse-Argonne Offensive. It includes most of the relevant map locations and should give an idea of the territory that is being fought over.