You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Day in July: An Early 20th Century Timeline

- Thread starter Zulfurium

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 117 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Feature: The Strategic Posture Of Germany And The Zollverein In 1938 Informational Five: The Fate of American Presidents Informational Six: State of the Catholic Church Feature: Scandinavia - Denmark Feature: Scandinavia - Norway Feature: Scandinavia - Sweden Informational Seven: Estimating Germany's Population in 1938 Informational Eight: State of Germany's Colonies in Africa and QingdaoA very nice update.

I'm a huge fan of Scavenius, his pragmatism when it came to dealing with both world wars are criminally undervalued outside the history departments at the universities. Happy to see him enter the stage, although I don't know how plausible his anglophobia is to be honest.

And need I say anything about the awesomeness of Savinkov swearing his banners... eh.. his loyalty to the one true Grand Duchess? You're making it difficult to chose between them and Brusilov's clique.

I'm a huge fan of Scavenius, his pragmatism when it came to dealing with both world wars are criminally undervalued outside the history departments at the universities. Happy to see him enter the stage, although I don't know how plausible his anglophobia is to be honest.

And need I say anything about the awesomeness of Savinkov swearing his banners... eh.. his loyalty to the one true Grand Duchess? You're making it difficult to chose between them and Brusilov's clique.

What happened to Jack Reed and Emma Goldman ITTL?

(Just been thinking about the movie Reds, which is why I asked.)

Jack Reed follows most of his OTL motions, with being expelled from the Socialist Party and forming a Communist Party in response, before fleeing arrest in the US and making it to Moscow. He is much more amenable to the TTL communist party and as such he makes more friends. The result is he isn't placed in as exposed a position and doesn't get infected with typhus. Instead he is made a premier propagandist, writing english-language pamphlets, fliers and the like to use in Britain and America to urge on revolutionary action. He soured quite firmly on Trotsky after the Parsky Offensive, having initially written a less popular booklet on the Kornilov Coup and countercoup. He instead makes his deepest impression with his early 1920 book Moscow Red describing the aspirational nature of the Moscow Communist Party, in effect creating an english-language primer on what precisely the Communists believe and their cultural, economic and social initiatives.

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman are deported like IOTL and make their way to Russia where they find themselves made welcome in Moscow and become voices in the Anarchist wing of the Communist Party as well as propagandists for the Anglosphere. Much the same happens for a number of other leftists across Europe and America.

What going in the balkans?

That should be answered in the next update, as the region awaits resolution at the Copenhagen Conference. It is relatively quiet in anticipation of that, with the Austro-Hungarians having used the breathing room following the Budapest Rising and the end of the war to stabilize the situation somewhat - although things remain quite tense.

A very nice update.

I'm a huge fan of Scavenius, his pragmatism when it came to dealing with both world wars are criminally undervalued outside the history departments at the universities. Happy to see him enter the stage, although I don't know how plausible his anglophobia is to be honest.

And need I say anything about the awesomeness of Savinkov swearing his banners... eh.. his loyalty to the one true Grand Duchess? You're making it difficult to chose between them and Brusilov's clique.

I am actually pretty positively inclined towards Scavenius. I feel he is undoubtedly one of the most talented politicians Denmark had in the first half of the century, and when everything is taken into consideration Denmark is probably the country active in World War Two to get off the lightest of all combatants. Him taking up the foreign minister post after the occupation to help ease the transition makes a good deal of sense and probably benefited Denmark in the long run. I reserve my utmost contempt for Peter Munch who played an instrumental part in forcing the disarmament of the Danish military - but that has a lot to do with familial history (my great granduncle was Ebbe Gørtz and was Army Commander of the Danish Army when the Germans invaded. He was forced to order much of the Danish Army onto leave on the eve of the attack on Denmark by the government, and the government then turned around and tried to blame him for the occupation. Assholes, the bunch of 'em.) so isn't directly relevant here.

I probably overdid his anglophobia, but Scavenius was noted for not being particularly happy about how important the British links to Denmark were and prefered working with the Germans. Read it as more of a grumpy man who has had to deal with a lot of stupid shit earlier in the day and is pretty damn fed up with everyone else, leaving him in a less than charitable mood.

Savinkov and Anastasia are going to be fun. I have decided to find a couple of people to follow semi-regularly, the first of which is obviously Anastasia. I will be experimenting with a couple of other figures to join her to see if there are any that give me the same level of enjoyment.

Jack Reed follows most of his OTL motions, with being expelled from the Socialist Party and forming a Communist Party in response, before fleeing arrest in the US and making it to Moscow. He is much more amenable to the TTL communist party and as such he makes more friends. The result is he isn't placed in as exposed a position and doesn't get infected with typhus. Instead he is made a premier propagandist, writing english-language pamphlets, fliers and the like to use in Britain and America to urge on revolutionary action. He soured quite firmly on Trotsky after the Parsky Offensive, having initially written a less popular booklet on the Kornilov Coup and countercoup. He instead makes his deepest impression with his early 1920 book Moscow Red describing the aspirational nature of the Moscow Communist Party, in effect creating an english-language primer on what precisely the Communists believe and their cultural, economic and social initiatives.

Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman are deported like IOTL and make their way to Russia where they find themselves made welcome in Moscow and become voices in the Anarchist wing of the Communist Party as well as propagandists for the Anglosphere. Much the same happens for a number of other leftists across Europe and America.

Well, that's awesome! Glad to see this TL is working out for some people at least! I suppose with this Moscow party, communists fleeing repression get more positive options overall so the exile community within the party will probably grow over time and give it an international characteristic.

Update Sixteen: The Copenhagen Peace Conference

The Copenhagen Peace Conference

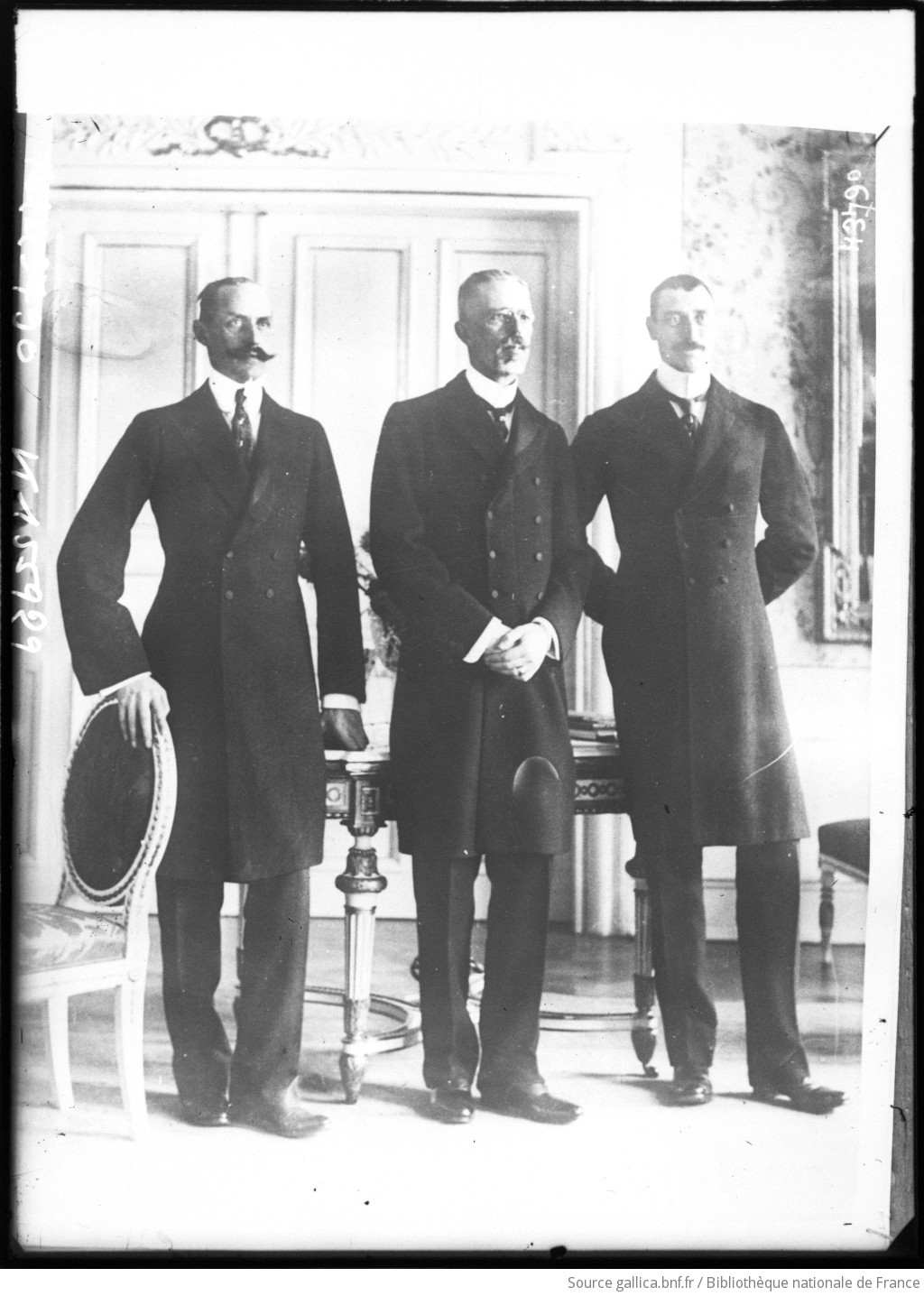

Kings of Scandinavia - Haakon VII of Norway, Gustav V of Sweden and Christian X of Denmark Meet Prior to The Copenhagen Conference

The Struggles of Accommodation

The prospect of hosting the conference to end the Great War was both an honour and a nuisance for the Danish state, which would have preferred to remain at a remove from the conflict where they would be able to continue profiting from their neutrality. However, now that they were hosting the conference, they would use the opportunity to secure whatever gains they could. The discussion over where to hold the negotiations consumed a week, eventually settling on the fittingly named Fredensborg Slot, translating as Peace's Palace, in north-eastern Zealand ,where the King of Denmark and his family would host the primary delegations. This would remove the delegates from the hustle and bustle of Copenhagen while allowing closer oversight by the Danes of the individual delegations, better ensuring their safety and removing distractions from the discussions. Not inconveniently, it also gave the Danish Foreign Ministry a greater ability to learn what each combatant was there to achieve. Kings of Scandinavia - Haakon VII of Norway, Gustav V of Sweden and Christian X of Denmark Meet Prior to The Copenhagen Conference

The Struggles of Accommodation

A discussion on who would attend the conference would consume most of the time leading up to the 1st of September, with considerable disagreements over colonial movements, national movement and particularly Russian factional representation. It was eventually settled that once the meat of the negotiations had been completed, the conference would grant these movements a voice at the conference should they so choose, a major concession on the part of the European combatants to an American request. This was not particularly welcomed by the European belligerents, who grew even more annoyed when the Danish delegation decided to call on their fellow neutral nations to provide representation as a counterweight to the two sides, and to serve as guarantors of the peace. In effect, this was meant to considerably strengthened Denmark's hand at the negotiations and prevented either the Allies nor the Central Powers from completely cutting them out of the negotiations.

During this period, the Danish government was in near constant deliberations over how to handle the negotiations and how to deal with the cost of such a major undertaking as the conference represented. In the end, the conference participants would be asked to provide three quarters of the cost of the conference, equally distributed between the two sides, while the Danish state absorbed the remainder. This was an issue which would cause some political infighting, but was eventually accepted by the Danish public and political establishment. On the warm and sunny morning of 1st of September 1919, King Christian X of Denmark welcomed the assembled delegations, numbering around a dozen major and more than sixty minor delegations from across the globe, to the royal Autumn Residence at Fredensborg and gave a rousing speech calling for the negotiations here to serve as the end of the horrific war which had gripped the world for so long and to keep in mind their duty to humankind to ensure that nothing like this ever happen again. With this done, the King turned over the conference to Foreign Minister Erik Scavenius, marking the start of the Copenhagen Conference.

Before the Conference began, the Central Powers had been through an intensive period of internal deliberation on how to approach the negotiations. At this series of meetings it quickly became clear that Germany remained the most powerful partner in the alliance by a great deal. Thus, there were a number of issues an prioritizations that needed to be clarified before the conference, often dominated by German decisions. The first issue, and likely among the most critical, was where to place the blame for the war other than one of the Central Powers. Discussion initially turned on whether to place any blame on the western Allies, but with the German wish to conclude the conflict as soon as possible there emerged a broad consensus in favour of placing the onus of the conflict primarily on Serbia. While blaming Russia was considered, it was felt that this would destabilise the Russian situation further and might well turn the Russian Whites against the Central Powers.

Another key area of discussion centred on the Balkan settlement, with a variety of options considered, while the contentious nature of the issue often left the three lesser parties at odds with each other over the issue. Central to this disagreement were the overlapping territorial ambitions of the Ottomans, Bulgarians and Austro-Hungarians. Eventually it would prove to be German mediation that resolved most of this issue, with Bulgaria abandoning its claims to eastern Thrace, having already secured the Dobruja. They would additionally participate in the partitioning of Serbia and Montenegro with Austria and the German puppet Principality of Albania. Under this agreement, northern Serbia was incorporated in the Austro-Hungarian Empire while Kosovo, a swathe of Albanian-speaking southern Serbia and Montenegro would be absorbed by Albania while the remainder of southern Serbia, including the important province of Macedonia, would fall under Bulgarian sovereignty. While the expansion of the Albanian Principality caused considerable tensions with the Austro-Hungarians and Bulgarians, the Germans were eventually able to convince the two that they would be unable to deal with the inclusion of these regions given the present instability both were experiencing. There were indications from Bulgarian side that they might want to push for complete control of Macedonia, including the parts under Greek control, but this proposal was eventually sidelined under German and Austro-Hungarian pressure.

Debates over the Middle East also consumed a great deal of time and effort as the discussions over what to do with the lands lost to the British and Arabs in the region , as well as what to do with Turkish claims in northern Persia and in the Aegean. After some back and forth, the Ottomans eventually agreed to accept the loss of their southern territories if necessary as long as they could secure control of the occupied sections of northern Persia (1). This turned the discussion to Italy, where a debate over how to handle that kingdom raged up until barely a couple days before the conference. The primary issue under discussion was whether the Austro-Hungarians wanted to annex any part of Italy, a prospect they considered for a while before it was discarded, given the already burdensome expansion they had agreed to in the south. With Germany the sole colonial power of the Central Powers, they were given broad leeway and support for any actions they might want to undertake in Africa and Asia. By the time the Central Powers met at the Copenhagen Conference, they were thus largely in alignment and ready to embark on a long struggle to secure their gains and reduce their losses.

While the Central Powers' pre-Conference deliberations had proceeded rather smoothly, with a single dominant power acting as adjudicator, the Allied efforts at coordination would prove considerably more challenging. Meeting in Paris, Lloyd George, Prime Minister Briand and President Marshall all arrived to determine the best way of approaching the coming conference. Over the course of August, with considerable support from their large teams of negotiators, the Allied leaders sought to find common ground for the negotiations to come. A few key points of agreement were established early on, including the continued independence of Belgium, or at the very least a refusal to accept German annexation of Belgium, no annexation of French lands by the Germans, the end of the Central Powers' occupation of Italy and a refusal to accept any Allied war guilt.

Having already conceded acceptance of the German Eastern settlement, the Allies next bandied about the potential of war guilt, or at least material compensation from the Central Powers for their losses. This was an issue of particular importance to the French, who would find it extremely difficult to rebuild their devastated country without recompense for the damage done to northern France and its peoples. It was eventually determined that this would prove a major point of the effort for the Allies, with fears that without some sort of financial compensation France might collapse economically and drag down the remaining Allied Powers with it. American and British goals centred primarily on reopening trade across the European continent and most importantly, some way of dealing with the immense costs accrued during the war.

At the same time, Briand sought to secure the continuation of the war-time alliance in some shape or form in order to secure their eastern border from German encroachment. While the British weren't particularly interested in such a major commitment to the continent, the threat of German aggression remained a constant worry, resulting in a preliminary agreement by Lloyd George to support a continuation of the alliance. The Americans were not nearly as sanguine. The United States had a strongly isolationist streak, and President Marshall had at times held to those ideals himself, with the prospect of entanglement in European affairs on the level of a formal post-war alliance seeming a high ask and something Marshall was uncertain he would be able to clear with the US Congress. However, he did accept a looser agreement to provide aid in France's time of need should it be asked of them and promised American economic cooperation to help rebuild the devastated French economy.

The issues of how to deal with Greece, Italy, the Middle East, Africa and the Pacific all posed considerably greater challenges than the Allies had initially thought it might, with fears of Greek territorial losses to Bulgaria or the Ottoman Empire prompting a promise to guarantee Greek territorial integrity. However, the most contentious issue to emerge prior to the conference came from the Sino-Japanese squabble over German territories in the Pacific region, eventually leading to Allied support of Japanese claims should it become a relevant issue, much to the outrage of the Chinese delegation. Importantly, President Wilson's conception of a League of Nations was not addressed in anything more than the broadest of terms, and when it occurred, it was as part of Briand's efforts to secure protection from Britain and the United States through a defensive league, rather than an international neutral body, as had been envisioned by President Wilson. With numerous issues still up in the air the Allies were forced to end their deliberations early in order to make it to Copenhagen on time for the Conference (2).

Footnotes:

(1) This is largely based on the OTL interests and focus of the CUP and Ottoman Empire during the war. They were far more concerned with securing their Pan-Turkic dreams than some Arab infested desert to the south. Outside of controlling the Holy Cities, or at least ensuring they remain in Muslim hands, there really isn't much of interest to them in the region, and as such they turn their focus firmly to the Caucasus and north-western Persia.

(2) IOTL the Paris Conference to negotiate the Versailles Treaty lasted from January to June for the first treaty with the Germans, and longer for the others. However, the important part to note is that all the negotiations and infighting at Versailles happened between the various Allies, and demonstrates the considerable disagreements they exhibited on a number of issues. In fact, IOTL the Allies were so exhausted by their internal deliberations in this period that they presented what had been meant to be the starting point for negotiations to the Germans as a take-it-or-leave-it deal, forcing their compliance alongside the other Central Powers, resulting in a far harsher treaty than anyone had really expected at the ceasefire. The fact is, all those disagreements are present ITTL as well, and here the Allies have barely a month to get things in order, with President Marshall arriving on the scene with next to no idea about what is going on, having been excluded from almost all war deliberations by Wilson as IOTL up till he was sworn in as President.

Delegates Meeting For The First Day of The Copenhagen Conference

Three Councils Meeting

The conference itself was constructed around a series of councils of five representatives from each side and a neutral mediator, primarily Danish, but there would also be Norwegian, Swedish, Spanish and Swiss negotiators in this position, each of whom brought a large number of aides and advisors to the negotiations, with each council occurring one after the other to address each issue under discussion one by one. Once a council had reached tentative agreement, the various representatives of smaller powers and movements would be allowed to present their individual cases on the issues under discussion in that council. At the conclusion of an individual council, the agreed on points would be laid out for inclusion in the final treaty while any major points of contention were set aside for the time being - to be resolved at the end of the conference as part of finalizing the treaty document. Throughout this period, the lead representatives at the negotiations for either side would continually debate and discuss individual issues internally in an effort at ensuring that a jointly acceptable message was conveyed.

With the Danish interest in ensuring that their neutrality remained inviolate in the negotiations, every draft, minutes of a meeting and other documents from the negotiations were copied and secured in an archive to ensure that every decision could be documented. The councils were aligned thus: first the issue of war guilt would be settled, to ensure that everyone was on the same page as to this issue. This would be followed by a council on the establishment of a League of Nations, a motion pushed forward by peace movements in many of the belligerent countries, and with a considerable degree of support amongst the neutral powers, with its charter to be examined in detail. The issues of the Benelux and Franco-German region would be discussed next, with all territorial as well as diplomatic and trade concessions to be cleared, whereafter the Italian situation would be dealt with. This would, in turn, be followed by a council on the Balkans, with the aim of ending the region's instability a primary goal, and after that the Middle East would become the focus of the next council. From there the councils would cover colonial affair, primarily in Africa and the Pacific, before turning to financial and trade relations, as well as the issues in order to ensure the reconstruction of Europe as swiftly as possible. Then a new council would turn its efforts to the Russian Civil War and how to respond to the growing revolutionary threat to the nations of the world. Once these nine separate councils had come to an end, the entirety of the agreement would be pieced together and reviewed with whatever issues which remained to be discussed being resolved as far as possible before the treaty was signed to end the Great War (3).

The issue of who was to blame for the eruption of the Great War would prove a provocative start to the negotiations. Despite the American promises of economic assistance, the likelihood of France surviving the economic calamity they had undergone remained extremely uncertain. As such, the Allies hoped to secure some form of monetary compensation from the Central Powers for the sheer scale of the devastation wrought to the French countryside from five years of uninterrupted warfare. The American and British fear was that if the French economy collapsed under the pressure of reconstruction, it could well trigger a wave of defaults, first in France, but then spreading to Britain and eventually America. If this were to happen, the Anglophone leaders feared that their own populations might well turn towards revolution, maybe even under German or Russian auspices, for it was not as though Germany had shown itself reluctant to use revolutionaries against their rivals so far. Their hope was thus that Germany might be made to pay a sum to help prop up the French economy long enough for it to recover, in return they thought themselves willing to accept considerable concessions.

However, for Germany to accept such a settlement would imply that the onus of the war lay with Germany or the wider Central Powers, a suggestion that met with immense resistance from all of the Central Powers. The subject matter grew increasingly heated over the course of early September, as the disagreements festered. It was under these circumstances that the Danish arbiter, Erik Scavenius, intervened with a suggestion that might bypass the entire matter. Based on knowledge of the Central Powers' wider aims, revealed by his friends in the German delegation, Scavenius was able to incorporate their hoped-for candidate for war guilt in a proposal that would allow for the propping up of the French economy. After all, neither the Danish nor the German governments had any interest in a revolutionary French state, or any other in Europe, particularly given the presence of revolutionary Russia already causing considerable instability across Europe.

This suggestion amounted to throwing Serbia under the bus in the name of peace. In effect, the Allies would agree to Serbia holding primary responsibility for the Great War. However, rather than characterise the major Allies as sharing in this war guilt, they were portrayed as a wronged party, dragged into a war against their better interests, and as such as deserving of compensation as any of the Central Powers. As the instigator of the calamity, Serbia would thus cease to exist, its territories split between the Central Powers. However, as part of the compensation owed to the western Allied powers, the Central Powers who participated in this annexation would pay Serbia's compensation on their behalf. Thus, it was not the Central Powers paying reparations, since they held no blame for the war, but was rather the Central Powers conveying the war reparations payed by Serbia to the Allied powers for dragging them into the war (4).

While the Allies had mixed opinions on the proposal, it would prove to be the best deal available. President Marshall initially protested that this was in breach with everything America had joined the war to prevent. However, Marshall was eventually talked around by the European leaders who, after playing on Marshall's relative inexperience with foreign affairs to secure his approval of the matter through obfuscation and diplomatic double-talk, eventually led Marshall to hand over leadership of the negotiations to his Secretary of State Robert Lansing in frustration. Marshall would remain at a remove from the negotiations, setting up base in London wherefrom he hoped to better deal with both domestic American affairs and the Copenhagen negotiations at a shorter remove (5).

The British were hesitant about accepting the deal as well, and for a time pushed for Germany to acknowledge their wrongdoing in the invasion of Belgium, but were eventually talked around by French pleas to stop anything that might prevent France securing this vital source of financing, Briand playing on Lloyd George's fear of a French collapse. The details of the reparations would take a while to work out, occurring while the rest of the conference pressed on, but in the end they would agree to a sum commensurate to five times Serbia's annual GDP spread between the Central Powers to be paid over the course of a decade, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria each undertaking to pay a third of the compensation. Thus, by the 24th of September 1919 the matter of war guilt had been resolved at the broadest level, debates over the specific language of the treaty on this particular issue continuing for several months more in the backrooms of Fredensborg.

Having already begun work on the Balkan settlement at the war guilt council, it was decided that with much of the Balkan issues at least partially addressed, that the Balkan Council might as well be the next topic for discussion, delaying the planned discussion of a League of Nations. With the dismemberment of Serbia already agreed upon, the focus turned to Greece and the Aegean. First of all, the Dodecanese Islands were returned to the Ottomans, a decision which would prove a minor point to the Italians by the end of the conference, who found themselves on the wrong side of either belligerent coalition. However, as the debate turned to Greece, the discussion came to hinge primarily on the recently overthrown Greek monarch Constantine I and the government of Prime Minister Venizelos.

At the heart of the matter lay the way in which Venizelos had secured ultimate power over Greece through a coup against his monarch, replacing him with the King's second son Alexander, who was left nearly powerless. The Greek delegation found itself defending their government against a Constantinian return to power with considerable ferocity, provoking a great deal of back and forth on the issue between the Great Powers. However, in this instance the British held firm, and were able to secure proper Allied backing for their position due to the perceived vital importance of not surrendering the Balkans entirely to the Central Powers. Under considerable pressure, the Central Powers eventually gave way on the issue, though they were able to secure the promise of monetary compensation for King Constantine and permission for him to return to Greece as a private figure on having signed a declaration of abdication. Additionally, Venizelos was forced to end the seclusion of Alexander, with the monarchical Central Powers wanting to ensure that Alexander was allowed to exercise his constitutional rights as Hellenic monarch. However, in return for these concessions, the Protocol of Corfu, which allowed autonomous rule for the Greek-speaking Northern Epirotes in Albania, was restored and guaranteed by the powers at the Copenhagen Conference.

It was at this point in time that news of the German diplomatic coup in Russia, securing the Don White abandonment of the Allies in favour of Central Power patronage, arrived in Copenhagen and sent shockwaves through the conference. The Allies found themselves suddenly on the run, despite recent successes in the Balkans. The loss of the Don Whites was an unmitigated disaster and left the Allies completely reliant on the successes of the Tsarist regime in Omsk for influence in Russia, although last word from Omsk indicated significant forward progress. With the Petrograd regime also collapsing before the eyes of the world, the delegates were suddenly reminded of the gravity of their situation. The Allies began pushing hard for the Russian council to be the next topic for discussion, as their factional allies in Omsk continued their offensive into late September. However, even as they were preparing a final push to secure an early Russian council, they received news that the Siberian positions were collapsing under Mikhail Frunze's offensive. With the situation in Russia suddenly turning firmly against them, the Allies decided to play for time in the hopes that they might be able to rebuild a better position once the situation in Omsk settled and ended their efforts to initiate the council on Russia, asking instead that the League of Nations be considered next. With this sudden reversal of course, the Central Powers and Neutrals were left to bemusedly agree to this request on the 5th of October 1919.

At the start of the Great War, the first schemes for an international organisation to prevent future wars began to gain considerable public support, particularly in Great Britain and the United States. Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, a British political scientist, coined the term "League of Nations" in 1914 and drafted a scheme for its organization. Together with Lord Bryce, he played a leading role in the founding of the group of internationalist pacifists known as the Bryce Group. The group became steadily more influential among the public and as a pressure group within the governing Liberal Party. In 1915, a similar body to the Bryce group proposals was set up in the United States by a group of like-minded individuals, including William Howard Taft. It was called the League to Enforce Peace and was substantially based on the proposals of the Bryce Group. It advocated the use of arbitration in conflict resolution and the imposition of sanctions on aggressive countries. None of these early organizations envisioned a continuously functioning body; with the exception of the Fabian Society in England, they maintained a legalistic approach that would limit the international body to a court of justice. The Fabians were the first to argue for a "Council" of states, necessarily the Great Powers, who would adjudicate world affairs, and for the creation of a permanent secretariat to enhance international co-operation across a range of activities.

By the end of the war, this peace movement had begun to have a profound impact the social, political and economic systems of Europe. Thus, this was viewed as an issue on which broad agreement could be ensured. However, while the idea of setting up a League of Nations was popular with all parties, the specifics of its mandate and remit were another matter entirely. On French side, there had been some initial suggestions that the League be limited to the Allies, with a common army, court to dispute differences and united economic and trade policies. All of which were fundamentally unacceptable to their American and British allies. While Wilson remained President, the British had been leery of his support for the extremely far-reaching League he envisioned. However, with Wilson's incapacitation and President Marshall's own worries over the implications to American sovereignty of the League of Nations, the British were soon able to find a degree of agreement by suggesting a far looser model, set forth by Lloyd George's representative at the council. Despite fierce criticism from the influential South African General Jan Smuts, the focus soon turned to a considerably looser and less powerful organisation. The Germans were themselves extremely uncertain about the prospect of League involvement in their Eastern vassal states and the prospect of having their military capabilities curtailed, and as such also pushed for a looser model.

However, at the League of Nations Council in Copenhagen there was one provision, inserted at Smuts' suggestion, that met with fierce resistance from the Neutral powers, to the considerable surprise of the belligerent powers. This was the idea of creating a Council of the Great Powers as permanent members and a non-permanent selection of the minor states to govern the League, a prospect that would vest power almost entirely in the Great Powers to the detriment of the lesser nations. With the Danes in uproar, loudly supported by many of the other Neutrals, under the implicit threat of biased mediators against those who opposed their suggestion, it was eventually agreed that every nation that wished to join the League and fulfilled the requirements for doing so, would join a permanent Congress of Nations where every state would have equal representation. Now granted, this formulation would eventually be amended to make the entry of non-white powers nearly impossible with the exception of China, Japan and the Ottoman Empire. The leadership of the League of Nations congress would be determined at random between all participating states every three years.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration, set up as part of the Hague Convention, would find itself subordinated to this new League of Nations and would find itself positioned as the most prominent arbitration court in the world, with its rulings made binding and its remits for arbitration expanded, although only at the instigation of both parties in a dispute. This would be accompanied by a General Secretariat to support the League's other activities, setting the groundwork for the League to expand into issues of international import, with permission to establish subsidiary organs through which to resolve urgent issues of the day following a simple majority vote in the Congress of Nations. The first of these subsidiary bodies would prove to be an attempt at implementing a refugee management system to cope with the massive number of refugees created by the war years, though it would be years before anything concrete saw the light of day.

One issue that would prove particularly contentious would be the Japanese and Ottoman hopes of including a paragraph bestowing equality of treatment on "all racial or national minorities" and providing guarantees against interference or discrimination against any creed or belief which was not actually inconsistent with public order or public morals. These proposals, however, met with considerable opposition, particularly amongst the Western Allies, on the grounds of violating state sovereignty and because of the practical problems of defining and enforcing a freedom-of-religion clause. Traditional attitudes and domestic purities also coloured the treatment of the Japanese recommendation in late October, that the Covenant be amended to include the recognition of "the principle of equality among nations and the just treatment of their nationals". A number of states, in particular Australia and the United States, fearing that this might affect their ability to control foreign immigration, vetoed the Japanese clause, given that for Americans, Australians, and South Africans, racial equality was a highly emotive issue. Liberal and internationally minded Japanese were deeply offended by the absence of the racial-equality clause, and would bear a grudge against their putative allies at their treatment at western hands for years to come. Thus, by the middle of November, the foundations of the League of Nation had been established, though the location of their headquarters remained in question, left for the end of the Conference (6).

Footnotes:

(3) I am trying to figure out how something like this would work and I don't think this is too bad of a way of approaching the negotiations under the circumstances. Potentially, all of these topic could be deliberated at the same time, but I think that given the circumstances this would be one of the better ways of approaching the challenge. This is far more organised and formalised than the OTL Paris Conference, where the vast majority of decisions were taken by the Big Three, Wilson, Lloyd George and Clemenceau from secretive hotel rooms, so everything here happens with a good deal more thought than IOTL. This also means it takes considerably longer.

(4) I really hope this isn't too confusing. In effect, the Central Powers are saying that the war wasn't their fault, but rather that the fault lays with Serbia, but that the Central Powers will pay the Allies on behalf of the Serbians, as they are absorbing their lands. This avoids assigning war guilt to the Central Powers or the Western Allies, leaving the Serbians to serve as scapegoats for the entire conflict, but still letting the allies, France in particular, get paid. The issue of Germany's Belgian invasion is largely viewed as an extension of the Serbian provocations and as such the Germans avoid liability for their violation of Belgian neutrality. Not a sparkling moment of British integrity, but in the end it serves their interests in bringing the war to a quick close, worries about domestic order and Ireland consuming the negotiators.

(5) This is an extremely important event which will have considerable consequences for the American performance during the negotiations. While President Marshall, lacking the time to familiarise himself with the situation and inexperienced in foreign affairs, was a weak negotiator, his very presence brought greater standing to the American delegation. By withdrawing to London, and eventually to Washington, he puts himself at a remove but tries to stay involved in the negotiations, micromanaging the effort from afar with predictable consequences. All of that is ignoring Congressional efforts to involve themselves in the negotiations, all of which combine to basically cripple Lansing's diplomatic efforts.

(6) ITTL the League of Nations takes on a considerably different shape from IOTL on the basis of some OTL proposals which I have mixed and matched. Perhaps the most important point is the lack of a Council of Great Powers, which leaves the smaller nations of the League considerably more influential than IOTL. However, this has also meant that the League doesn't secure anything close to the degree of power it was supposed to have IOTL. It is almost exclusively a deliberative body, set up to adjudicate disputes on a voluntary basis. This makes for a weaker League, but also one with considerably more legitimacy than IOTL given that no one is going to expect it to prevent the stuff people thought it would IOTL when or if something like it should happen ITTL.

Delegates Meeting At The Copenhagen Conference

That's Mine, That's Mine and That's Mine

However, the German leadership that had come to power with Ludendorff's fall from grace were willing to approach the issue from a variety of directions, with particularly Kühlmann believing that he might well be able to undermine Allied relations through certain specific concessions to the French, which might then leave them more open to a Belgian settlement. While the German delegation was largely understanding of the fact that they would be unable to secure any larger section of Belgium, there were smaller concessions that might resolve the issue. Thus, in a brazen move, the Germans proposed the partitioning of Belgium between its neighbours, to considerable uproar from the small Belgian delegation. Under the German proposition, Luxembourg and the eastern half of Liège Province, namely the two eastern Arrondissements of Liège and Verviers, would be annexed to Germany, while the Flemish-speaking Flanders would be incorporated into the Netherlands and the remainder of French-speaking Wallonia would go to France (7).

However, this proposal quickly began floundering under American opposition to supporting such annexationist policies, soon joined by British declarations that the Belgian border remained inviolate. The Belgian delegation caused constant disruptions and in general the proposal was viewed with considerable negativity. While the proposal seemed to be on death's doorstep, the French began jockeying for support. The primary focus of this effort would prove to be the pragmatic British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, who found himself under considerable pressure from his French allies. With much of the conference still to go, the French were able to promise considerable support for points later in the program, with the backing of Germany, as they sought to sweeten the pot for the British. Under this charm offensive and promises of later concessions, the British eventually gave way, but not before demanding significant minority protections and a major payment to the soon-to-be dispossessed Belgian Royal Family. Under internal pressure from Kühlmann, the Kaiser eventually gave way to a suggestion by the foreign minister which would see the Germans, French and Dutch pay out compensation to Albert and see him named Prince of Lüttich, in effect granting him a German peerage and allowing his annexed subjects to remain under Albert's rule.

While the Americans cried foul and there were considerable demonstrations by pro-peace movements and a national independence movement in Belgium, there was little these powers could do to prevent the decision without the Americans being forced to surrender major diplomatic capital. This would severely strain the relations between the European and American Allies, as had been hoped by Kühlmann, and Robert Lansing even went as far as threatening to abandon the promised economic support for France if action against American interests were to be undertaken again. The contentious nature of this council meant that it was only brought to a close on the 22nd of December 1919.

Rather than immediately throw themselves into the next council, the Copenhagen Conference was called to recess for two weeks. In this period, Fredensborg Slot was the centre of festivities, as diplomats from across the world mingled and relaxed from the stresses of the negotiations. The Royal family invited the delegates to participate in Christmas Dinner according to Danish traditions, on Christmas Eve, the 24th of December. The Danish hosts put forward their best foot and sought to charm the participants, both diplomats and media. Tours of Denmark were given, both to Copenhagen itself and to the majestic castle of Kronborg, of Shakespearian fame under the name of Elsinore, and the recently arrived former Russian Empress Consort Maria Feodorovna, once Princess Dagmar of Denmark, made her entrance clad in mourning black in an effort to remind all present of the grievous losses she had experienced and to urge them on to resolving the Russian tragedy.

After celebrating the New Year, the Italian Council was begun on the 5th of January 1920. First to be discussed was the current occupation of the Italian nation by both the Allies and Central Powers following the Italian defeat in late 1917 and how to deal with the Italians themselves, who had sent a delegation to the conference which was so internally divided, that they often provided three conflicting opinions on any single issue. At the heart of the divisions in the Italian delegation was the precipitous divisions within Italy itself which had emerged in the two years since their defeat.

This had begun with the sudden collapse of Prime Minister Orlando Vittorio's government in early 1918 over the Italian surrender. In the time since, Italy had experienced no less than five different governments, the third of which had seemed to be nearing stability under Francesco Saverio Nitti around the time the Armistice of 16th June 1919 was signed, only to collapse under the prospect of the conference. Since then, a brief interlude under a resurgent Paolo Boselli, prime minister at the time of the Caporetto and Second Asiago, had followed only for Vittorio Orlando to claw back to power in October. However, the Italian delegation consisted largely of Boselli's men, who hated and opposed Orlando for having ousted their patron. Rather than remove these men from the delegation, which would have brought attention to the issue and expended valuable domestic political capital, Orlando had instead simply appointed additional men to the delegation from amongst his own supporters. Thus, the Italian delegation was largely unable to do much to influence the Italian Council.

With the Italians divided and widely dismissed, the belligerent powers were left to impose their peace on Italy. The result saw Italy stripped of its colonial empire with France securing Libya, Britain taking Eritrea, the Ottomans the Dodecanese Isles while Germany took over the Italian protectorate on the Somali coast and saw the Japanese trade their southern concessions in Tianjin to Germany in return for the Italian concessions in northern Tianjin, this being in closer proximity to their other concessions in the city. Italy was further forced to accept the repayment of debts held by the Western Allies and Central Powers from before the war, but were able to avoid any direct annexations of Italian territory (8). The considerable gains of the Western Allies at Italy's expense were accepted by the Central Powers in return for promises surrounding later councils, where they had considerably greater interests at play. The feeding frenzy came to an end on the 12th of January, with the Italian delegation finally speaking in one horrified voice, seeing their careers going up in flames before them.

After a brief recess to secure Italian acceptance of the terms, which was accomplished after two days of intense pressure by all parties at the negotiations, the Council on Near- and Middle Eastern Affairs came under way on the 14th of January 1920. With the principal points of the Russian treaty already accepted prior to the start of the negotiations, the British were in a relatively weak position as regarded their claims in the region. With neither the French particularly concerned with the region and the Americans disinterested, it was left to the British alone to truly champion the Allied cause in the region and invest diplomatic capital in the effort, securing some additional support from the French in response for British acquiescence of the Belgian settlement. With most of the Central powers also relatively uninterested, the negotiations as this council would prove relatively sedate. The greatest disruptions experienced by the council in this period would stem from the Arab delegation's efforts to secure a voice in the deliberations. This was a key point which would see considerable debate prior to the council proper, as the Turks viewed the Arabs as rebels rather than a legitimate power. It was eventually determined that the Arabs would be given a voice at the council, but they would find themselves largely a pawn in the negotiations.

The Turks were largely focused on securing their Pan-Turkish ambitions, and as such proved surprisingly open to territorial exchanges with the British and their puppets in the region. Their focus was firmly on securing control of Persian Azerbaijan and Ardabil provinces from the disintegrating Qajar Persia, and they were more than willing to make concessions to the south if it would secure them those gains. Despite muted Persian protests, the British were more than willing to make such concessions, in return securing the Basra Vilayet for themselves as well as the Hejaz Vilayet for their Arab allies. Now the focus turned firmly to the Levant, where the issues grew a great deal more contentious.

At the heart of the issue was control of the Holy Sites in Palestine, which the British hoped to secure for themselves, while the Ottomans feared what consequences a loss of religious authority of this level might have on the Ottoman Empire. This issue, as well as the safety of Christians within the Ottoman Empire, brought the French back into the discussion in a big way, soon followed by the Americans. With Jewish Zionists urging on the British and American governments, the Allies soon found themselves united in their aim of forcing Palestine from the Turks. Under growing pressure, and with their allies reticent to burn support over the issue, the Turks were eventually forced to give way. However, the Turks would get one over on the British by proposing that instead of Britain taking direct control of the region, it should instead go to the incipient Hashemite state. A promise to end Christian persecutions and a quiet promise to reestablish the profitable trade relations with France in Syria eventually split the Allies on the issue once more. A further week of back and forth, with the Central Powers now backing their allies fully on the proposal and the Americans weighing in in favor of the proposal in a bid to restore some of their anti-colonial bona fides, finally brought the British around to the issue. The result was that Palestine would be joined with the lands south of the Sanjak of Acre, near the current frontlines in the Levant, as well as the Sanjaks of Ma'an and Hauran which would be joined to the growing Arab Kingdom. This council came to an end on the 8th of February 1920, as the focus moved further abroad to the colonial concessions in Africa and Asia.

The Colonial Council was initiated on the 10th of February 1920 and would be primarily characterised by German efforts to recoup as much of their colonial empire as possible from the various Allied forces that had occupied them over the course of the war, before slowly degenerating into an imperialistic feeding frenzy. In an effort to deal with the Allies separately, the Germans began negotiations with the Japanese in secret first, hoping to retake what they could of their Asian territories. Seeking to secure the return of at least their most important concessions, the Germans offered the Japanese the entirety of their Hankou concession, the entirety of German Papua New Guinea, a move that was sure get the Japanese and British Dominions at each other's throats, and their pacific colonies in return for reestablishing the German and Austro-Hungarian concessions at Qingdao and Tianjin. Though the Japanese initially balked at the former of the two concessions, they eventually agreed in return for diplomatic support against their British allies (9).

The British and Japanese had, predictably, erupted in fierce squabbling over the Pacific Isles and Papua New Guinea once word of the German-Japanese negotiations spread as the British dominions of Australia and New Zealand sought to secure the Papua New Guinean mainland, causing tensions to rise considerably in the Pacific. Spying an opportunity, the Americans jumped into the game as well with an effort to secure German Samoa. In the end, the British would find themselves the losers in these negotiations, with the Japanese accepting the transfer of Qingdao in return for German support in their Pacific dispute, securing the islands north of the Papua New Guinean mainland while the Americans secured Western Samoa. This left only the ownership of the German Papua New Guinea main island to be relegated to the final writing of the treaty, with the Chinese delegation protested vocally to their exclusion from the negotiations, having been relegated to the position of a minor power and only allowed to speak once most of the primary points had been established, and the Australians extremely angered at the British failure during these negotiations.

The discussion next turned to Africa where General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck had stunned the world by his incredible comeback after having been driven from German East Africa in 1917, only to conduct a continuous campaign through Allied territories in Portuguese East Africa, the Belgian Congo and Rhodesia by late 1918. As British troops were drained from the area to support the war effort in Europe, Lettow-Vorbeck had been able to exploit this weakness to wreak havoc on the Allies and recapture vast swathes of German East Africa around Lake Tanganyika, the Ruanda-Urundi region and into southern Uganga (10). Thus, the Germans were able to claim that German East Africa remained unoccupied at the negotiations, and should not be considered disputed. Furthermore, the dissolution of Belgium left their massive Congolese colony up for grabs, creating major opportunities for expansion to all the neighbours of the Congo. Under the circumstances, the Germans hoped to restore their control of Kamerun and East Africa, hopefully to be expanded at the expense of the Belgian Congo. With the Germans willing to trade both Togoland to the French and German South-West Africa to the British, the European Allies proved more willing to negotiate, accepting German demands for Kamerun and German East Africa in return for Germany providing further financing of the French reconstruction.

The focus now turned to how Belgian Congo would be divided between the colonial powers that bordered it. German East Africa saw itself expand to the Luapula River in the south, stretching all the way north to Aruwimi River in the north, covering a swathe of eastern Congo, including the major trading point at Stanleyville. The remainder of Katanga, stretching all the way across southern Congo to Angola, would be transferred to Britain alongside a broad section of north-eastern Congo. The German border of Neu-Kamerun found itself stretched to the Ubangi River, through French territory, but the Germans would otherwise have to contend themselves with what they had restored and taken in the east. The Portuguese would trade Cabinda Province with the French in order to secure the Belgian Congo from the southern bank of the Congo River Delta to the Kasai River confluence, east to the Sankuru River confluence and up the Sankuru River. The remainder of Belgian Congo would go the French. As part of the treaty, all of the powers promised to not impede traffic for any reason along the entirety of the Congo River (11). These deliberations finally came to an end on the 22nd of March 1920, to considerable American rumblings, extremely unhappy at the way in which the Copenhagen Conference had turned into a naked land grab by the European Powers and fearing the consequences in the coming Presidential Election.

Footnotes:

(7) I want to give props to @Rufus for mentioning this sort of division of Belgium earlier in the thread. I had originally considered just including the German annexation of Liege and Luxembourg, but this makes a lot more sense and works better with what I was imagining.

(8) Events in Italy have continued playing out since we left them in update five, and that time hasn't been particularly friendly to the Italians. IOTL Italy experienced considerable political chaos following the Great War, which I have decided to have happen a bit differently ITTL. With Orlando having only just come to power in time to surrender, he is initially tarnished with defeat but soon fights his way back to power. That said, after the settlement of the Italian Council it is unlikely that he can hold on much longer. The Italians are so concerned with political infighting that they shoot themselves in the foot during the negotiations and end up bearing the brunt of the peace.

(9) I know that the Germans retaking Qingdao is probably a bit of a stretch, but I think that it remains plausible if you think of the Japanese as requiring German support to secure the remainder of the German Pacific Empire, rather than seeing it go primarily to the British or Americans as happened IOTL. Control of Qingdao is extremely important if the Germans want to retain any major form of influence in China and as such they are willing to sacrifice a great deal to secure it. While the Japanese might have been able to hold onto it, they value the possibility of a more friendly Germany higher than immediate territorial gains in China. They have already secured considerable Chinese concessions elsewhere, so they are content to see the Chinese frustrated on the mainland.

(10) IOTL von Lettow-Vorbeck was actually making a comeback in the region when news of the armistice arrived in November 1918. ITTL he has much longer to secure success in the region, while the Allies are draining their support for the region to support the European struggle, allowing the Germans to hold onto significant parts of western German East Africa. I would strongly suggest reading up on the East African Theater of the Great War, it is absolutely incredible.

(11) I considered retaining Belgian Congo as a League of Nations mandate, but ITTL that concept never comes into play without Wilson to push for "no annexations" at the negotiations. Thus, the European powers prove more than willing to split the spoils. As such, Belgium's crown jewel finds itself partitioned between the Germans and the European Allies in a display of imperialism that will haunt the reputation of the Copenhagen Treaty for decades to come.

British Delegation Signs The Treaty of Copenhagen

Sign On The Dotted Line

In Copenhagen, Marshall had assembled an impressive group of financial and economic experts, including Norman Davis, the assistant secretary of the Treasury and his chief financial adviser, already in close contact with Keynes, Thomas Lamont from J. P. Morgan & Co., the largest American overseas investment house. However, it was to prove a far more difficult scenario to implement than the experts anticipated. At the heart of the issue were French fears that a return to normalcy would leave the devastated France unable to compete, having to expend vast sums of money to rebuild the tight bands of infrastructure and industry in northern France. As such, the prospect of the Germans returning immediately to the global markets posed the threat of completely undermining French efforts to resist economic domination by the other belligerent nations. Further, the American push to reduce trade barriers as much as possible opened the possibility of French industry might never be able to rebuild properly. The French were joined in opposition to the American demands by the British who, while supporting the reopening of trade with the Central Powers, feared that the Germans would monopolise Eastern European markets, and as such wanted American guarantees of economic support should such an event come to pass.

The Germans themselves were open to restarting trade with the Western Allies, but wished to keep control of their own trade policies, and those of their puppet states. Even more important for the Central Powers, was the unfreezing of funds in British and American markets which had been frozen at the outset of the conflict - as well as the release of all confiscated ships and the like. There would be a good deal of back and forth during the meetings that followed the initial proposals, with a host of normalization efforts coming into play, ranging from the free exchange of prisoners of war and debt forgiveness to trade arbitration councils and generalized rules of economic conduct. In the end, the European powers would resist American efforts to impose restraints on national trade barriers, but would agree to the steady reopening of international markets, the unfreezing of fund, a free exchange of prisoners of war and the establishment of a permanent Trade Arbitration Court under the auspices of the League of Nations, again lacking enforcement capabilities, but providing a venue for the resolution of trade disputes and negotiations. By the 4th of April 1920, the council had come to an end and excitement began to build for the end of the grueling negotiations. The Americans were once more left feeling that they had lost out in the negotiations, crowded out by the old European Powers who seemed to have joined together during the conference to ensure that they reaped as much reward from the process as possible, while excluding what they viewed as counter-productive American efforts at breaking into European markets.

The attentions of the conference now turned firmly eastward to Russia, where the twin ascendant Red powers of Yekaterinburg and Moscow seemed closer than ever to driving all other powers from the region. In the more than half a year since the start of the Copenhagen Conference, the situation in Russia had changed drastically. Not only had Germany abandoned their support of the Petrograd Whites, just as they collapsed, in favour of the sweeping the legs out from under the Allies by securing an alliance with the Don Whites, but the Siberian Whites had collapsed completely early in 1920 and the Allies had been struggling to find a successor to support in their stead. The current focus was on holding the line at Irkutsk while a new Russian government was slowly rebuilt in the Transbaikal around the figure of Ataman Grigory Semyonov. However, the murder of Tsar Mikhail II in Irkutsk would result in a major British drawdown in support for the Whites, leaving only the Americans and Japanese to support the successors to the Siberian Whites for the time being.

One thing that everyone could secure agreement on, however, was a condemnation of Trotsky for his role in the trial and execution of Tsar Nikolai II and his wife as well as the murder of the extended Romanov family, a proposal put forward personally by a grief-striken Maria Feodorovna at the invitation of the Danes. This was followed by another condemnation of the Communist regime in Moscow for its role in destabilising the world order and promoting revolutionary activities across the globe. With the collapse of the Siberian Whites, the Central Powers, particularly Germany, sought to gain recognition for the Don Whites as the legitimate successor state to the Russian Empire. At German invitation, Prince Lvov had travelled to Copenhagen on behalf of the Don Whites and provided a heartfelt plea for aid against the destabilising Red Russians, and for the recognition of the Don Whites.

This was met with glum anger by the Americans, who had hoped to buy time to build a proper successor state in eastern Siberia, while the British and French eventually gave way, on the condition that the Germans allow free trade with the Don Whites and secure passage through the Bosporus - enabling them to reduce Don White reliance on German support. The Americans, once again abandoned by their allies, were forced to acquiesce through gritted teeth, though they were able to ensure that no language in the treaty prevented them from continuing their Siberian Intervention - the matter now having become one of national pride in the face of European treachery and resistance to the encroachment of Red ideologies. With American dissatisfaction nearing a high point, the Russian Council was brought to an end on the 14th of April 1920, bringing the individual councils to an end and leaving only the final full treaty to deal with.

The last series of negotiations saw the last few remaining disputes resolved, with the British eventually securing mainland Papua New Guinea, to be placed under Australian management, while the Headquarters of the League of Nations was set to be located in Copenhagen on a preliminary basis, with the Permanent Court of Arbitration remaining in the Hague and the Trade Arbitration Court being set up in Zürich. However, the majority of the time was taken up by a great degree of back and forth on the specific wording of the treaty. As the month neared its end a sense of hope began to suffuse the participants and a push towards the end was undertaken. Finally, on the 30th of April 1920, delegation after delegation signed the Treaty of Copenhagen, ending the Great War nearly six years after it erupted in August 1914.

There was, however, one major hiccup in the negotiations, because the American delegation insisted on Congress signing off on the agreement before they would agree to sign the treaty. This caused considerable outrage, as all of the powers had been tasked with regularly securing acceptance from their own governments and legislatures after every council and the move was widely considered an attempt by the Americans to wriggle out of a treaty that had not gone their way, threatening world peace and order out of spite and political gain. This was not entirely inaccurate, as the Democratic party sought to delay the signing of the treaty long enough to either secure the coming elections or force the Republicans, should they win, to sign a treaty that was bound to be unpopular. Under considerable pressure from the various delegations and an increasingly hostile European press, Secretary Lansing would eventually sign the treaty on the 8th of May, and the Americans would consider the war at an end, but the legitimacy of the Treaty of Copenhagen would be continually questioned in America and became a point of contention in the election.

Word of the signing of the treaty would spread far and wide, prompting worldwide celebration, although this would quickly change once the specifics of the terms arrived in the countries who had been punished the most: Italy, Belgium and China. In China, the news from the Colonial Council had arrived already in late February, but there had remained some uncertainty surrounding these rumours. When this came to an end on the 8th of May, it prompted great public outcry, spiralling out of control with great speed and prompting immense internal turmoil. In Belgium, the news prompted mass protests and demonstrations, which proved most successful in Flanders, where they were able to secure religious autonomy, while in both Wallonia and Lüttich the demonstrations were put to an ignominious end with considerable harshness by French and German forces respectively. Italy itself reacted with horror to the treaty, having seen itself reduced to a deeply unstable secondary power without a colonial empire to speak of.

In America, news of the treaty was greeted with a deeply unsatisfied mien, as the populace was left questioning what they had sacrificed so much for. The clear revelation of the imperialistic natures of both Britain and France, who had participated in the frenzied savaging of their own allies during the negotiations in an effort to strengthen their own positions, left the Americans soured towards their European allies, while reactions to America's own actions in Samoa remained muted. How to respond to these issues would come to play a major role in the 1920 elections and would see President Marshall's already shaky popularity collapse entirely. While the British and French alliance remained strong moving forward, the Americans began distancing themselves almost immediately from the alliance structures, supporting the rebuilding of France solely for fear of a French default on their loans. At the same time, the massive expansion of the Central Powers into Eastern Europe and the Balkans left them glutted and satisfied, working to reestablish their war torn societies. The Great War had come to an end, and the powers of the world now turned their gazes to the future.

Summary:

Preparations are undertaken for the Copenhagen Conference as the various sides formulate a preliminary game plan for the Copenhagen Conference.

War Guilt, the Balkan Settlement and the establishment of a barebones League of Nations are all agreed to after considerable negotiations.

Imperialism comes to the fore, as the European powers exploit American weakness to participate in a frenzied spate of partitioning and annexations.

The last councils are concluded and the Treaty of Copenhagen is signed, but signs that not everyone is satisfied become immediately apparent.

End Note:

I really hope that this update doesn't disappoint or bore any of you, despite dealing with the intricacies of the diplomatic struggle surrounding the end of the Great War. I know that in a lot of TLs, much of this stuff is skipped and people tend to just go directly to the end product, but given that I am trying to be as detailed as I can with all of this and trying to keep things as plausible as I can, while still pushing things in the direction I want to explore, I think this is the best way to approach it. The struggle to secure a lasting peace is incredibly grueling and I wanted to convey some of the immense work that would have gone into it. To my knowledge this is quite unlike anything I have seen anyone else attempt, and I don't think that we have had anything like it IOTL since prior to the Vienna Peace Conference of 1815.

To be honest, I think the best parallel, and the treaty negotiations I am drawing most on to understand the dynamics, would probably be the complex negotiations surrounding the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 which ended the Thirty Years' War, or maybe some of the conferences of the 19th century, though those don't quite fit well either. In the case of the 30YW you had two alliances who were largely unable to completely defeat the other, having been fought to exhaustion and seeking to negotiate peace in a series of marathon negotiations. At Vienna in 1815, at Versailles in 1919 and at Potsdam in 1945 (as well as the other treaties ending World War One and Two) it was very much a matter of securing a victorious peace. While all of these were contentious, the participants almost all came from the victorious powers and in every case the treaty ending the war was largely dictated by the victorious powers. This is a completely different animal and would have played out very differently from Versailles IOTL. I don't think I would be doing it justice without putting all of this work into it.

In the end, this treaty will come to be seen as one of scapegoats, and as a successful effort by the European Great Powers to redirect the fury of the war onto already defeated powers, sparing the French, British, Germans and Austro-Hungarians from bearing the main burden of the war. That said, the Americans really come out of these negotiations with very little to show for it for a number of reasons. First of all, President Marshall, who sought to influence the negotiations early on, was an inexperienced diplomat who was outplayed by the European ministers, which was compounded when he left Copenhagen and tried to run the negotiations at a remove through Lansing. Second, the Americans really had very few clear ideas of what they actually wanted to accomplish once President Wilson was out of the way and his Fourteen Points lost support. Furthermore, the Americans had very little knowledge or understanding of any of the regions under discussion, being relative newcomers to almost all the primary fields of battle, allowing the European powers to exploit their lack of understanding. Third, the Americans lost most of their ability to influence the negotiations the moment their immense forces were no longer needed. In the end, the Treaty of Copenhagen is even more of a rout for the Americans than the Treaty of Versailles was IOTL, and this time around that fact is considerably clearer to the Americans. We will be exploring the consequences of this as we move forward.

Here are some maps of the Treaty of Copenhagen (They are rough estimates, so take them with a grain of salt) :

Division of the Balkans - (Orange = Austria-Hungary, Red = Romania, Green = Bulgaria, Grey = Albania

Last edited:

Very interesting. The map of Europe is redrawn and to be honest the only clear winner is Germany, but there are many losers. This feels relatively plausible, especially given the length you've taken in justifying these decisions. I'm a little shocked to see everyone just accept the annihilation of Belgium, but I can see the justification.

That said, of the "victorious powers" have bitten off way more than they can chew, I think. The next twenty years will be messy for everyone involved - especially as Germany tries their level best to assert dominion over a massive eastern empire that I really don't think they can maintain, Austria-Hungary tries to continue existing, and the Ottomans keep being sick. France came out with pretty much everything they could hope for - territorial expansion, reparations (even if less than they wanted), and an end to the bloodshed. I think this will be politically stabilizing to at least some degree. Britain is humiliated and deprived of continental allies, so that's rough.

If I have one objection, it would be to the American reactions to events. I think Marshall, even if unprepared, is rather more clever and savvy than he is portrayed here. I think he gets an unfair rap on account of his OTL decisions which here would have not been an issue (no one can say Marshall doesn't deserve the presidency), after all. I also think he would have pushed for a formal legal recognition of the Monroe Doctrine by the European powers, and that in general the American (delegation, not public) would have been satisfied with any outcome that ensured their debts got paid. The public and Congress are a totally different matter, of course.

Still, very fantastic - a cool end to the Great War and it will be wild to see how things develop from here. Somehow I doubt this is the War to end all wars. Even more than the OTL one, this feels like a formalized truce.

Last thought: no stab-in-the-back myth in Germany. Instead maybe the cultural trauma of having to maintain something of a forever war on the eastern front? And once Russia settles down a little bit, let me be the first to beg for some sort of European map.

That said, of the "victorious powers" have bitten off way more than they can chew, I think. The next twenty years will be messy for everyone involved - especially as Germany tries their level best to assert dominion over a massive eastern empire that I really don't think they can maintain, Austria-Hungary tries to continue existing, and the Ottomans keep being sick. France came out with pretty much everything they could hope for - territorial expansion, reparations (even if less than they wanted), and an end to the bloodshed. I think this will be politically stabilizing to at least some degree. Britain is humiliated and deprived of continental allies, so that's rough.

If I have one objection, it would be to the American reactions to events. I think Marshall, even if unprepared, is rather more clever and savvy than he is portrayed here. I think he gets an unfair rap on account of his OTL decisions which here would have not been an issue (no one can say Marshall doesn't deserve the presidency), after all. I also think he would have pushed for a formal legal recognition of the Monroe Doctrine by the European powers, and that in general the American (delegation, not public) would have been satisfied with any outcome that ensured their debts got paid. The public and Congress are a totally different matter, of course.

Still, very fantastic - a cool end to the Great War and it will be wild to see how things develop from here. Somehow I doubt this is the War to end all wars. Even more than the OTL one, this feels like a formalized truce.

Last thought: no stab-in-the-back myth in Germany. Instead maybe the cultural trauma of having to maintain something of a forever war on the eastern front? And once Russia settles down a little bit, let me be the first to beg for some sort of European map.

Very interesting. The map of Europe is redrawn and to be honest the only clear winner is Germany, but there are many losers. This feels relatively plausible, especially given the length you've taken in justifying these decisions. I'm a little shocked to see everyone just accept the annihilation of Belgium, but I can see the justification.

That said, of the "victorious powers" have bitten off way more than they can chew, I think. The next twenty years will be messy for everyone involved - especially as Germany tries their level best to assert dominion over a massive eastern empire that I really don't think they can maintain, Austria-Hungary tries to continue existing, and the Ottomans keep being sick. France came out with pretty much everything they could hope for - territorial expansion, reparations (even if less than they wanted), and an end to the bloodshed. I think this will be politically stabilizing to at least some degree. Britain is humiliated and deprived of continental allies, so that's rough.

If I have one objection, it would be to the American reactions to events. I think Marshall, even if unprepared, is rather more clever and savvy than he is portrayed here. I think he gets an unfair rap on account of his OTL decisions which here would have not been an issue (no one can say Marshall doesn't deserve the presidency), after all. I also think he would have pushed for a formal legal recognition of the Monroe Doctrine by the European powers, and that in general the American (delegation, not public) would have been satisfied with any outcome that ensured their debts got paid. The public and Congress are a totally different matter, of course.