The 6 Best Non-Franchise (at the time) Action Films 1989

From Six in Violence Netsite, November 23th, 1999

Yea, we all remember Back to the Future 2 or Ghostbusters 2 or Willow 2 or Lethal Weapon 2 or Star Trek 5 or Indiana Jones 3. But what about those non-franchise films? So here we go again, another Six in Violence, this time for 1989.

#6 Farewell to the King: It has been called “Milius’ Apocalypse Now”, which is screamingly ironic given that Apocalypse Now was a Milius passion project to begin with. Farewell to the King underperformed at the box office where its dark tones alienated audiences and where it was ironically unfairly compared to Apocalypse Now by critics, but has become a beloved cult classic since, even as controversy surrounds it. Farewell to the King is the story of American WWII deserter Learoyd (Nick Nolte) who escapes a Japanese death squad and becomes the God King of a tribe of Bornean headhunters because his blue eyes are seen as divine. As their God King, Learoyd decides to fight the British rather than rejoin the war or western society. It’s a dark and moody film that addresses issues of civilization vs. savagery, freedom vs. servitude, and human nature. Some have called it a racist film that promotes white superiority with its use of some old 19th Century tropes[1], while others see it as a justified criticism of the hypocrisies of western “civilization”. Like other Milius films, it has become a darling of the political right. And it nearly didn’t come to be as we know it, for original distributors Orion got into an editing war with Milius[2]. Thankfully Universal stepped in and took over the production, allowing Milius to edit his own picture in exchange for doing the third Conan film. Despite its controversy and problematic tropes, Farewell to the King is a moody and atmospheric film and, in my opinion, truly is Milius’s Apocalypse Now.

#5 The Set Up: So, this movie did well at the theaters but mediocre with the critics. Audiences loved the buddy-cop chemistry between Patrick Swayze’s Ray Tango and Bruce Willis’s Gabe Cash[3], even if the script was crapped on by critics. But yea, Swayze’s slick charm as the fancy, wealthy Beverly Hills detective and Willis’s “everyman” charm as the blue collar LA cop meshed well, and that makes this amazingly violent buddy cop popcorn flick, well, pop. It follows the two mismatched cops as they get (you guessed it) set up for a murder, wrongly imprisoned, and then have to escape from prison and clear their names by defeating the evil crime lord Yves Perret (Jack Palance) who had set them up to begin with. It is violent as hell in the most ‘80s action movie way possible, pushing the bounds even for an R rating. It found a new life in VHS and VCD and remains a cult classic today.

#4 Honey, I Shrunk the Kids!: Sometimes a film that begins as one thing becomes another. Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, the sequel to 1986’s InnerSpace, began as a completely different script titled “Teeny Weenies” written by Stuart Gordon and produced by Brian Yuzna. And originally the main character was named Wayne Szalinski and was a freelance inventor who lived in Fresno, and was reportedly written with Chevy Chase in mind. However, once Gordon and Yuzna brought the film to Disney, the resemblance to the popular 1986 Disney film was unmistakable, so Wayne Szalinski was changed to be Jack Putter from the earlier film, a role reprised by Rick Moranis. And yes, technically this was already a franchise film when it released, but you didn’t know that now, did you? Anyway, Putter, now living in Fresno, is trying to reinvent the shrinking technology, which was seized by the government as “dangerous” after the events of the prior film. And while there is a brief cameo by Lt. Tuck Pendleton (Jeff Bridges), this film is all about Putter and his kids, whom he accidentally shrinks in a system test. The rest of the film follows the kids as they navigate the dangers of their own back yard and try to reunite with their dad so that he can re-enlarge them, with a small subplot involving Putter attempting to hide his shrinking technology from a snooping Government Agent. The effects are incredible for the era and the film has just the right mix of scary, fun, and exciting for a family audience, unlike the rest of the films on this literally bloody list. It was a big hit in theaters, spurred a reframing and update to the InnerSpace ride at the Living Body Pavilion in addition to other immersive “big backyard” attractions at the Disney parks. The film was a favorite on VHS and VCD and spawned two sequels, even if it has fallen a bit out of the public eye in recent years.

Similar to this, but as a Late '80s flick

#3 Manhattan Transfer[4]: Next is an ensemble heist action-comedy and modern-day Robin Hood story out of Paramount fronted by Eddie Murphy. The action follows a team of former employees of Franklin Toys who lost their jobs when their Brooklyn-based company was bought out and dismembered for a quick buck by corporate raider Jason Burnes (Michael Douglas[5], playing the in-universe “guy that Gordon Gekko was based on” in a double-meta-joke bit off stunt casting). Angry about it all and ready to “take back what’s ours”, Murphy’s Cedrick Lawrence, a former shipping manager, recruits charismatic shift foreman Lamar Kingman (Richard Pryor), genius accountant Schlomo Rosen (Gene Wilder, who also directed), snarky factory maintenance tech “Jersey” Jim Mattocks (Bruce Willis), and electronics prodigy Clarence Clay (a then largely unknown Don Cheadle) in a scheme to steal all of the money that Burnes made from the raid and redistribute it among the former Franklin workers. This ends up requiring the team to break into Burnes’s Manhattan penthouse suite past his extensive security systems and guards in order to hack his home office computer, all so that Rosen can institute a clandestine wire transfer of all of the millions in ill-gotten funds to a third-party account. The film is a pretty by the numbers heist film, but is also one hell of a lot of fun, with excellent comedy and chemistry between its ensemble actors. And thus, it did well both at the box office and on home media even. It’s been kind of forgotten following a spate of similar films in the 1990s and 2000s, but it remains one of the best in the genre and one of my personal favorites.

#2 Roadhouse: For second place we have a second so-over-the-top-it’s-good action flick, in this case the film that was marketed as a “Honky Tonk Cocktail” in reference to the hit Hyperion drama of the prior year. Like Cocktail it’s set in a bar (well, a roadhouse) and it features an old mentor (Sam Elliott) teaching an edgy young New Kid (Mickey Roarke) the rules of the road. Oh, and they’re bouncers, not bartenders. Bouncers that literally kick ass. Like The Set Up, it is violent as hell. And it’s not a gritty drama like Cocktail, it’s a full-on martial arts flick with leather-clad bikers instead of ninjas. High kicks, flying punches, and even a torn-out larynx ensue. This is quite possibly the manliest movie ever made. If it was any more hyper-masculine it would veer into Gay and I’d have to pass it along to Dirk and Donny. In fact, it’s so fucking over the top that you’d swear it was a parody of violent ‘80s action flicks if it wasn’t so obviously taking itself hyper-seriously. This film is loved, mocked, and loved and mocked at the same time, and deservedly so. In fact, make a double-feature of this and The Set Up and you will get to enjoy The Last of the Breed, two transition pieces that capture that quintessential ‘80s-ness at a time when that was already on the way out.

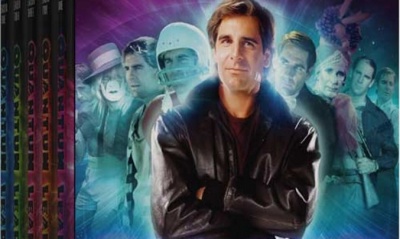

#1 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure: And finally, it’s the little movie that refused to not be made! Bill & Ted began as a most excellent stand-up sketch by comedians Ed Solomon and Chris Matheson, which the duo converted to a sweet screen play called “Bill & Ted’s Time Van” in, like, ’87, dudes. Director Steven Herek called it “laugh out loud” funny and noted that it was, like, “either going to be a huge hit or a huge flop.” Like, whoa! The bodacious screenplay was about to be taken up by Fantasia Films, but like instead got picked up by De Laurentiis Entertainment due to a bizarre set of circumstances like way too complex to explain here, bro. Then the time travelling van idea, later a ’66 Chevy, was deemed too much like the DeLorean from Back to the Future, so this got changed to a much more totally original idea of a time travelling phone booth. Um, did someone, like, call a Doctor? Hey, at least it wasn’t, like, blue and bigger on the inside, yea? And yea, I can totally already see the comments loading up with “but Bill & Ted isn’t an action movie!” It’s got action. It’s close enough. I like this movie. It’s righteous. Piss off. Anyway, after like totally auditioning literally hundreds of actors, Solomon and Matheson found Keanu Reeves and they knew immediately that they’d found their Ted. Reeves had been on the hook to star in Young Guns, but had to drop out due to an unexpected rescheduling of the principal photography date. Several more auditions found their Bill in Alex Winter, someone they’d totally dismissed the first time through but decided to give one more chance. After searching through the rolls of glamorous rock stars to play Rufus, they ended up discovering George Carlin. It was like fate; preordained. Or like if some sort of radical time traveler was, like, interfering to make it happen in just a certain way[6]. Fate even seemed to intervene when De Laurentiis Entertainment went bankrupt and was bought up by Hollywood Pictures/ABC. Michael Eisner at first wanted little to do with the puerile teen Sci-Fi comedy and was going to can it (bogus!), but the most righteous Jeffrey Katzenberg saw potential. His faith was rewarded when Bill & Ted became a hit, grossing $40.5 mill against a modest $6.5 mil budget. Fate can, like, have most strange but most excellent plans.

[1] Specifically, the one TVtropes.org calls “Mighty Whitey”.

[2] In our timeline Orion’s cut enraged Milius and “ruined” it in his opinion. Here another studio gives him the creative freedom he wants, but in return for another film. I’m assuming that his cut has better legs, but its hard to say given subjectivity and the blindness of creators for their own work.

[3] Yes, this is essentially this timeline’s Tango & Cash.

[4] Original to this timeline! With Harlem Nights done a year Pryor…err…prior and Beverly Hills Cop not really a “thing” in this timeline, Murphy and Pryor decided to have some fun in the gap in his schedule.

[5] Blame Ms. Khan again!

[6] “No way!” you say? Yes way! Unlike every other production in this timeline, which you can assume to have at least some minor changes to dialog, editing, or other aspects, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure is exactly the same, scene for scene, line for line, as the film we all know and presumably love. You can thank Mrs. Khan for this one too. She suggested “what if Bill & Ted was exactly the same movie?” Essentially, what if all the little butterflies piled up and seemingly conspired to result in the exact same film for all intents and purposes as we got in our timeline? And I’d never event talked about Second Order Butterflies with her! She framed it in Lebowskian terms, like the film just “abides” with the winds of allohistorical change. Consider this just a fun meta-humor bit and your ticket to not take all things in this timeline too seriously.

P.S.: RETCON ALERT. Taking a cue from @Mackon (thanks!), who made a good point about the BBC's public ownership at least insisting on a British Companion. So Lark Vorhees is out, and a different Companion is in.

From Six in Violence Netsite, November 23th, 1999

Yea, we all remember Back to the Future 2 or Ghostbusters 2 or Willow 2 or Lethal Weapon 2 or Star Trek 5 or Indiana Jones 3. But what about those non-franchise films? So here we go again, another Six in Violence, this time for 1989.

#6 Farewell to the King: It has been called “Milius’ Apocalypse Now”, which is screamingly ironic given that Apocalypse Now was a Milius passion project to begin with. Farewell to the King underperformed at the box office where its dark tones alienated audiences and where it was ironically unfairly compared to Apocalypse Now by critics, but has become a beloved cult classic since, even as controversy surrounds it. Farewell to the King is the story of American WWII deserter Learoyd (Nick Nolte) who escapes a Japanese death squad and becomes the God King of a tribe of Bornean headhunters because his blue eyes are seen as divine. As their God King, Learoyd decides to fight the British rather than rejoin the war or western society. It’s a dark and moody film that addresses issues of civilization vs. savagery, freedom vs. servitude, and human nature. Some have called it a racist film that promotes white superiority with its use of some old 19th Century tropes[1], while others see it as a justified criticism of the hypocrisies of western “civilization”. Like other Milius films, it has become a darling of the political right. And it nearly didn’t come to be as we know it, for original distributors Orion got into an editing war with Milius[2]. Thankfully Universal stepped in and took over the production, allowing Milius to edit his own picture in exchange for doing the third Conan film. Despite its controversy and problematic tropes, Farewell to the King is a moody and atmospheric film and, in my opinion, truly is Milius’s Apocalypse Now.

#5 The Set Up: So, this movie did well at the theaters but mediocre with the critics. Audiences loved the buddy-cop chemistry between Patrick Swayze’s Ray Tango and Bruce Willis’s Gabe Cash[3], even if the script was crapped on by critics. But yea, Swayze’s slick charm as the fancy, wealthy Beverly Hills detective and Willis’s “everyman” charm as the blue collar LA cop meshed well, and that makes this amazingly violent buddy cop popcorn flick, well, pop. It follows the two mismatched cops as they get (you guessed it) set up for a murder, wrongly imprisoned, and then have to escape from prison and clear their names by defeating the evil crime lord Yves Perret (Jack Palance) who had set them up to begin with. It is violent as hell in the most ‘80s action movie way possible, pushing the bounds even for an R rating. It found a new life in VHS and VCD and remains a cult classic today.

#4 Honey, I Shrunk the Kids!: Sometimes a film that begins as one thing becomes another. Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, the sequel to 1986’s InnerSpace, began as a completely different script titled “Teeny Weenies” written by Stuart Gordon and produced by Brian Yuzna. And originally the main character was named Wayne Szalinski and was a freelance inventor who lived in Fresno, and was reportedly written with Chevy Chase in mind. However, once Gordon and Yuzna brought the film to Disney, the resemblance to the popular 1986 Disney film was unmistakable, so Wayne Szalinski was changed to be Jack Putter from the earlier film, a role reprised by Rick Moranis. And yes, technically this was already a franchise film when it released, but you didn’t know that now, did you? Anyway, Putter, now living in Fresno, is trying to reinvent the shrinking technology, which was seized by the government as “dangerous” after the events of the prior film. And while there is a brief cameo by Lt. Tuck Pendleton (Jeff Bridges), this film is all about Putter and his kids, whom he accidentally shrinks in a system test. The rest of the film follows the kids as they navigate the dangers of their own back yard and try to reunite with their dad so that he can re-enlarge them, with a small subplot involving Putter attempting to hide his shrinking technology from a snooping Government Agent. The effects are incredible for the era and the film has just the right mix of scary, fun, and exciting for a family audience, unlike the rest of the films on this literally bloody list. It was a big hit in theaters, spurred a reframing and update to the InnerSpace ride at the Living Body Pavilion in addition to other immersive “big backyard” attractions at the Disney parks. The film was a favorite on VHS and VCD and spawned two sequels, even if it has fallen a bit out of the public eye in recent years.

Similar to this, but as a Late '80s flick

#3 Manhattan Transfer[4]: Next is an ensemble heist action-comedy and modern-day Robin Hood story out of Paramount fronted by Eddie Murphy. The action follows a team of former employees of Franklin Toys who lost their jobs when their Brooklyn-based company was bought out and dismembered for a quick buck by corporate raider Jason Burnes (Michael Douglas[5], playing the in-universe “guy that Gordon Gekko was based on” in a double-meta-joke bit off stunt casting). Angry about it all and ready to “take back what’s ours”, Murphy’s Cedrick Lawrence, a former shipping manager, recruits charismatic shift foreman Lamar Kingman (Richard Pryor), genius accountant Schlomo Rosen (Gene Wilder, who also directed), snarky factory maintenance tech “Jersey” Jim Mattocks (Bruce Willis), and electronics prodigy Clarence Clay (a then largely unknown Don Cheadle) in a scheme to steal all of the money that Burnes made from the raid and redistribute it among the former Franklin workers. This ends up requiring the team to break into Burnes’s Manhattan penthouse suite past his extensive security systems and guards in order to hack his home office computer, all so that Rosen can institute a clandestine wire transfer of all of the millions in ill-gotten funds to a third-party account. The film is a pretty by the numbers heist film, but is also one hell of a lot of fun, with excellent comedy and chemistry between its ensemble actors. And thus, it did well both at the box office and on home media even. It’s been kind of forgotten following a spate of similar films in the 1990s and 2000s, but it remains one of the best in the genre and one of my personal favorites.

#2 Roadhouse: For second place we have a second so-over-the-top-it’s-good action flick, in this case the film that was marketed as a “Honky Tonk Cocktail” in reference to the hit Hyperion drama of the prior year. Like Cocktail it’s set in a bar (well, a roadhouse) and it features an old mentor (Sam Elliott) teaching an edgy young New Kid (Mickey Roarke) the rules of the road. Oh, and they’re bouncers, not bartenders. Bouncers that literally kick ass. Like The Set Up, it is violent as hell. And it’s not a gritty drama like Cocktail, it’s a full-on martial arts flick with leather-clad bikers instead of ninjas. High kicks, flying punches, and even a torn-out larynx ensue. This is quite possibly the manliest movie ever made. If it was any more hyper-masculine it would veer into Gay and I’d have to pass it along to Dirk and Donny. In fact, it’s so fucking over the top that you’d swear it was a parody of violent ‘80s action flicks if it wasn’t so obviously taking itself hyper-seriously. This film is loved, mocked, and loved and mocked at the same time, and deservedly so. In fact, make a double-feature of this and The Set Up and you will get to enjoy The Last of the Breed, two transition pieces that capture that quintessential ‘80s-ness at a time when that was already on the way out.

#1 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure: And finally, it’s the little movie that refused to not be made! Bill & Ted began as a most excellent stand-up sketch by comedians Ed Solomon and Chris Matheson, which the duo converted to a sweet screen play called “Bill & Ted’s Time Van” in, like, ’87, dudes. Director Steven Herek called it “laugh out loud” funny and noted that it was, like, “either going to be a huge hit or a huge flop.” Like, whoa! The bodacious screenplay was about to be taken up by Fantasia Films, but like instead got picked up by De Laurentiis Entertainment due to a bizarre set of circumstances like way too complex to explain here, bro. Then the time travelling van idea, later a ’66 Chevy, was deemed too much like the DeLorean from Back to the Future, so this got changed to a much more totally original idea of a time travelling phone booth. Um, did someone, like, call a Doctor? Hey, at least it wasn’t, like, blue and bigger on the inside, yea? And yea, I can totally already see the comments loading up with “but Bill & Ted isn’t an action movie!” It’s got action. It’s close enough. I like this movie. It’s righteous. Piss off. Anyway, after like totally auditioning literally hundreds of actors, Solomon and Matheson found Keanu Reeves and they knew immediately that they’d found their Ted. Reeves had been on the hook to star in Young Guns, but had to drop out due to an unexpected rescheduling of the principal photography date. Several more auditions found their Bill in Alex Winter, someone they’d totally dismissed the first time through but decided to give one more chance. After searching through the rolls of glamorous rock stars to play Rufus, they ended up discovering George Carlin. It was like fate; preordained. Or like if some sort of radical time traveler was, like, interfering to make it happen in just a certain way[6]. Fate even seemed to intervene when De Laurentiis Entertainment went bankrupt and was bought up by Hollywood Pictures/ABC. Michael Eisner at first wanted little to do with the puerile teen Sci-Fi comedy and was going to can it (bogus!), but the most righteous Jeffrey Katzenberg saw potential. His faith was rewarded when Bill & Ted became a hit, grossing $40.5 mill against a modest $6.5 mil budget. Fate can, like, have most strange but most excellent plans.

[1] Specifically, the one TVtropes.org calls “Mighty Whitey”.

[2] In our timeline Orion’s cut enraged Milius and “ruined” it in his opinion. Here another studio gives him the creative freedom he wants, but in return for another film. I’m assuming that his cut has better legs, but its hard to say given subjectivity and the blindness of creators for their own work.

[3] Yes, this is essentially this timeline’s Tango & Cash.

[4] Original to this timeline! With Harlem Nights done a year Pryor…err…prior and Beverly Hills Cop not really a “thing” in this timeline, Murphy and Pryor decided to have some fun in the gap in his schedule.

[5] Blame Ms. Khan again!

[6] “No way!” you say? Yes way! Unlike every other production in this timeline, which you can assume to have at least some minor changes to dialog, editing, or other aspects, Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure is exactly the same, scene for scene, line for line, as the film we all know and presumably love. You can thank Mrs. Khan for this one too. She suggested “what if Bill & Ted was exactly the same movie?” Essentially, what if all the little butterflies piled up and seemingly conspired to result in the exact same film for all intents and purposes as we got in our timeline? And I’d never event talked about Second Order Butterflies with her! She framed it in Lebowskian terms, like the film just “abides” with the winds of allohistorical change. Consider this just a fun meta-humor bit and your ticket to not take all things in this timeline too seriously.

P.S.: RETCON ALERT. Taking a cue from @Mackon (thanks!), who made a good point about the BBC's public ownership at least insisting on a British Companion. So Lark Vorhees is out, and a different Companion is in.

A Hippie in the House of Mouse (Jim Henson at Disney, 1980)

And hire a more older actor to play Anakin in the first movie; a teen ager will make the idea that Padme and him fall in love and that the Jedi council has strong concern to train him more belieavable Christian Slater, maybe?

www.alternatehistory.com