Chapter XV: Those Who Escaped

“It’s ironic, don’t you think? When the Treaty of Belfast was initially ratified, we were convinced that our nation had been dealt a crippling defeat. Yet now, when I look upon the fate of Europe and the rest of the world at large, it is clear to me that the armistice was the single greatest gift one could be offered during that wretched war. We were offered the gift to escape the inferno of the Great War, and if the Entente had not accepted this most precious gift, I fear that Western Civilization would’ve died on the battlefields all those years ago.”

-King Edward VIII of the Imperial Federation during a private conversation with Emperor Pedro Henrique of the Second Empire of Brazil, circa May 1950.

A Scottish couple walking on the former site of the Battle of Oban, circa June 1930.

On October 30th, 1929, the guns fell silent on the British Front. After nearly half a decade of combat over who would reign over the island of Great Britain, the Empire of America and the Workers’ Commonwealth had conceded that continued fighting was little more than a slow and painful suicide pact and thus reached an agreement under which the isle was partitioned between a still-socialist south and Entente-occupied north. The ratification of the Treaty of Belfast would mark the de facto conclusion to the Entente alliance’s participation in the Great War, and as thousands of troops from her member’s decaying empires returned home whilst the gunboats of the Empire of America and Brazil withdrew from their engagements against communists and fascists alike, a world completely unrecognizable from 1914 yet still condemned to the tragedy of the Great War was left to its War of Resources, all without Entente intervention.

Just like the wider world as a whole, so too had the Entente become unrecognizable since its initiation of the Great War with the Central Powers back in 1914. Once the great powers of the post-Napoleonic world order, the major founding members of the Entente had succumbed to the fires of revolution, either being completely destroyed at the end of a radical’s rifle or forced into exile in their once-mighty colonial empires. Whatever remained of these former superpowers had grown to become dependent on the Second Empire of Brazil, a later addition to the Entente whose neutrality throughout much of the Great War, vast quantity of natural resources, and rapid industrialization had turned a nation largely irrelevant on the world stage prior to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand into the lifeline of a coalition spanning the globe, even after its exile from much of the European continent. Now, as the Entente was tasked with picking up the pieces of its shattered authority, Brazil had gone from the tail wagging the dog to the emperor of fallen empires.

The question still, however, remained: could Brazil, with its newfound position as a great world power, stop the Entente from falling further into oblivion and humiliation?

The Great War had undeniably destabilized the colonial holdings of the Entente, oftentimes with disastrous consequences. French Indochina and the British Raj in particular erupted into revolution alongside their comrades in cosmopolitan France and Great Britain, and by the beginning of Phase Three, not only had these revolutionary conflicts been successful, but the newly independent states in southern Asia had become pivotal players in the war effort of the Third International in their own right. But this wave of self-determination would not arrive in Africa, arguably the greatest victim of 19th Century European imperialism, until 1929, in large part thanks to the neutrality of much of the continent’s colonial regimes throughout much of Phase One and Phase Two under the conditions of the Treaty of Bloemfontein. The centralization of the French Fourth Republic under the presidency of Philippe Petain proved to be the spark that ignited the fire that set the entirety of Africa ablaze, starting with a series of wars of independence in French Equatorial Africa against a rapidly collapsing government-in-exile.

Of course, what eventually became known as the African Spring was not to be reserved exclusively to what remained of the French Fourth Republic. Springtime had finally arrived in Africa, and the flowers of independence did not hesitate to seize this opportunity to blossom. Starting in June 1929, anti-colonial protests coordinated by the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), erupted throughout Lagos, with the hope of mobilizing public support to their side amidst the wars of independence to their east and a diminishing British military presence within colonial territories. Formed in 1923 by Nigerian nationalist Herbert Macaulay to compete in local elections, the NNDP was initially formed to promote the democratization of Nigeria and increased participation in the colony’s civil society by locals, however, the rise in instability throughout the British Empire due to the outbreak of a civil war in the United Kingdom a year prior eventually radicalized both the NNDP and Macaulay himself towards outright independence due to colonial authorities heightening taxation and resource extraction in Nigeria while simultaneously decreasing the military presence within the colony. In other words, the British were angering the Nigerian people while at the same time decreasing their capabilities to put down any revolt within the possession.

After the outbreak of the Indian War of Independence in 1924, the NNDP officially adopted the independence of Nigeria as a state completely sovereign from the reign of the House of Windsor as an element of its platform, having been galvanized by the outbreak of revolution within the Jewel of the British Empire. Colonial authorities predictably condemned this development, but Loyalist forces on the brink of defeat in Great Britain itself, there was little that they were willing to do. Macaulay and his compatriots continued to freely roam the streets of Lagos, and by the time of the Loyalist expulsion from Europe in April 1925, all elected positions within southern Nigeria had been filled by representatives of the NNDP. By 1929, the NNDP was undeniably the dominant force in Nigerian civil society, having evolved from being a mere thorn in the side of the Loyalists to a serious threat to the survival of colonial rule, a threat that the Loyalists now found themselves completely ill-equipped to combat. Only a spark was needed to ignite the flames of revolution, and there was little that the Loyalists could do to douse said flames.

This spark came in the form of protests against colonial taxation organized in large part by the Lagos Market Women’s Association (LMWA), a coalition of female market leaders led by Macaulay ally Alimotu Pelewura, in early June 1929. Protests against colonial policies were far from uncommon at this point, especially within the Nigerian capital city of Lagos, however, what made the LMWA’s protest, largely against a tax imposed by colonial authorities specifically on Nigerian women, a pivotal turning point was the timing. Just to the east of Nigeria, French Equatorial Africa was imploding into various uprisings in the name of self-determination, and this emboldened the Nigerian nationalist movement. Hundreds of thousands of Nigerians flocked to the streets, and the LMWA protest soon escalated into the single largest anti-colonial protest in Nigerian history, all endorsed by the NNDP, which passed a resolution on June 14th, 1929 declaring that it would not seize the current protests until Nigeria was granted independence.

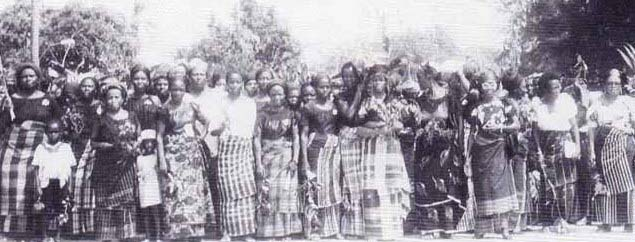

LMWA protesters of the Nigerian Revolution, circa June 1929.

In order to finally achieve the goal of sovereignty, the NNDP, LMWA, and various other organizations all committed to the cause of Nigerian liberation quickly set about coordinating a strategy of nationwide civil disobedience, hoping to effectively grind the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria to a standstill. Throughout the remainder of June 1929, general strikes, sit-ins, boycotts (particularly of goods produced by Britons or other Loyalist territories), and street occupations all became commonplace throughout Nigeria, albeit primarily concentrated in the southernmost cities, and surely enough, Nigeria began to reach a point where continued Loyalist control would cost more than simply granting independence. It was at this point that the colonial regime could not merely sit by and watch its grip on power dissolve, and as such, actions were undertaken to repress the NNDP’s revolution in its tracks, including mobilizing military forces to monitor and break up protests, subsidizing businesses collapsing due to the strikes and boycotts, and instating curfews in the cities with the highest concentrations of protests, most notably Lagos, however, in most instances, these activities only inflamed tensions, and by the end of June 1929, violent confrontations between military forces and protesters in the streets of Lagos were becoming increasingly common.

To make matters worse for colonial authorities, the nationwide resistance soon gained institutional support from various local traditional rulers, starting with a public endorsement of the NNDP protest efforts and the independence of Nigeria by the Oba of Lagos on June 26th, 1929. The Oba, while respected, had been relegated to a mostly ceremonial position, however, his support for the NNDP’s revolution soon proliferated to rulers with greater authority. In the southeast, several Igbo chiefs mainly pressured by the protesters of the LMWA gradually endorsed the push for independence and refused to enforce colonial laws, namely taxation, throughout early July 1929. While the NNDP protest movement was most prominent within southern Nigeria, it also won the open support of rulers of various northern emirates, who, like the Igbo chiefs, refused to enforce various colonial laws starting in July 1929. As the Nigerian independence expanded in both its scope and power, a colonial government more or less incapable of introducing greater reinforcements from Loyalist territories due to the ongoing invasion of Great Britain at the time fled its collapsing domain when Governor Hugh Clifford of Nigeria announced the provisional evacuation of himself and his cabinet to Cape Town on July 24th.

The retreat of Clifford’s government was seemingly the death knell of the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. Morale for remaining Loyalists plummeted while the morale of revolutionaries soared, and as colonial forces either defected to the NNDP, stood aside against the revolutionary tide sweeping the nation, or waged a futile war of suppression against the people, it was clear to foreign and international observers alike that Herbert Macaulay’s vision of a free Nigeria was on the horizon. On July 28th, 1929, militant NNDP revolutionaries occupied colonial government buildings throughout Lagos, facing little resistance in the process, followed by an announcement by Macaulay at a makeshift rally attended by thousands mere hours later that, in the absence of Henry Clifford, the NNDP and its allies would be seizing control of the Nigerian apparatus of state and declare independence. As similar uprisings against local colonial institutions occurred throughout the day and traditional rulers recognized Macaulay’s authority, the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria practically fell apart within the span of a day, and whatever few remaining Loyalist armed forces were left in the territory were ordered to evacuate on July 29th, 1929, the same day that the NNDP declared the Nigerian Provisional Government and appointed Herbert Macaulay as its president, tasked with overseeing the development of the constitution for a sovereign Nigerian state.

The Death of New Imperialism

“If our people are not cautious in the face of continental acts of sedition over the coming months, I fear that the light of Western Civilization may be extinguished on the African continent. In fact, it is possible that the light may have already been extinguished.”

-Prime Minister Barry Hertzog in an address to the House of Assembly, circa June 1929.

Flag of the Nigerian Confederation.

In the aftermath of the Nigerian Revolution, the Empire of America would enact a blockade of the Nigerian Provisional Government, however, much like the case with ground troops, the bulk of Loyalist naval forces were concentrated on the British Front, and the ships that could be spared to starving Macaulay’s newfound state into submission was limited. In the meantime, with an invasion of Nigeria unlikely for the time being, President Macaulay and his provisional coalition of NNDP leadership, civil society organizations, and traditional rulers set out in forging the constitution of a sovereign Nigerian state. Establishing a loose federal system, the Nigerian Constitutional Convention of August 1929 opted to give the national government, operating as a parliamentary republic, powers limited to foreign affairs, defense, commercial and fiscal policy, and public infrastructure development.

The bulk of political authority was diverted to the constituent states of Nigeria, mostly a continuation of the various local protectorates and colonial administrations, who were free to organize their own political structure so long as it included a democratically-elected legislature necessary to pass bills and upheld the national bill of rights, which, among other things, included the freedoms of speech, religion, and press, secured voting for both men and women, and prohibited legal discrimination on the basis of ethnicity or culture. As long as a state constitution met these requirements, any political structure was effectively permitted, and given the role of traditional rulers in the Nigerian revolution, this soon meant that the political structure of the various Nigerian administrative divisions was a tapestry of republics and constitutional monarchies. Upon the official ratification of the new constitution on August 30th, 1929, the decentralized Nigerian Confederation was born, and only a few days later, the hastily-elected unicameral Parliament of Nigeria, consisting of a NNDP supermajority collaborating with various regional parties, elected Herbert Macaulay to the premiership.

Prime Minister Herbert Macaulay of the Nigerian Confederation.

The creation of an entirely new nation all happened while her former colonial masters stood idly by, incapable of doing much beyond a meager blockade and collection of sanctions. Given the success of the Nigerian Revolution and various wars of independence led by Felix Eboue of Ubangi-Shari, the African Spring was sure to expand elsewhere, particularly into the especially vulnerable holdings of what remained of the British Empire. The Protectorate of Uganda was the next colony to enter springtime thanks to the Young Baganda Association (YBA), an association of young educated people from the Kingdom of Buganda that had originally been formed in 1919 in opposition to the power wielded by Indian migrants and traditional chiefs but had since radicalized into a Baganda nationalist movement pushing for the independence of a colony as East Africa was simultaneously cast aside as an interest of Loyalists and increasingly reliant on local forces for self-defense. By the time of the African Spring, the YBA had become such a strong force in Ugandan civil society that it had won the support of Kabaka Daudi Chwa, the figurehead ruler of Buganda.

News of struggles for independence in West Africa was met with enthusiasm by the YBA, which mobilized protests and rallies for self-determination within the streets of Buganda starting in June 1929, however, it was ultimately the Nigerian Revolution that really ignited the spark of independence within East Africa. The declaration of the Nigerian Provisional Government on July 29th was both a punch in the gut to local supporters of British rule, who came to realize that the Empire of America was neither capable of nor willing to maintain many of its holdings throughout Africa, and a grand boost of encouragement for the YBA and its allies, who were now convinced that colonial authorities were unable to significantly retaliate against independence efforts. Therefore, under mounting pressure from Baganda nationalists, Kabaka Daudi surprisingly declared the independence of his kingdom to a crowd of supporters in the capital city of Mengo on August 2nd, 1929. Despite lacking any serious political power, armed nationalists, the majority of which were defected members of the Uganda Rifles internal security force, subsequently overthrow the Lukiko, the governing council of customary chiefs, thus transforming the Kingdom of Buganda into a de facto sovereign absolute monarchy within only a few hours.

Over the coming days, the Kabaka of Buganda asserted his newfound power in collaboration with the YBA and the defectants of the Uganda Rifle, the latter of which now formed the basis for the Baganda Army, and developed a Parliament of Buganda modeled after that of the United Kingdom, albeit headed by a prime minister and cabinet appointed by the Kabaka who still wielded considerable power over the armed forces in particular, which was in reality the basis for a one-party regime, with all initial MPs in the Baganda parliament being appointed by the YBA to closely work with Daudi Chwa. This new regime would quickly bring about considerable changes to the society of Buganda by, among other things, redistributing land, deposing traditional rulers, and detaining Indian residents, a target of YBA bigotry. All the while, despite lacking significant support from the Empire of America or other Entente member states, the destabilized Protectorate of Uganda rallied what remained of local Loyalist forces together in a war against the Baganda Army, sparking what became referred to as the Ugandan Civil War on August 4th, 1929.

Baganda Army soldiers fighting in the Ugandan Civil War, circa September 1929.

To Uganda’s south, the African Spring took a much more politically revolutionary bent. It was in the Loyalist holdings of southern Africa that the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICWU) had been formed in 1919 as a syndicalist general union modeled off of the primarily American Industrial Workers of the World, uniting urban and agrarian laborers alike under the banner of radical socialism in a region of the world where white minority rule profited off of the exploitation of a black majority working class. The socialist revolutions in France, Great Britain, and Ireland in the early 1920s dramatically fueled left-libertarian movements throughout the world, and the ICWU was no exception, with the union winning over hundreds of thousands of workers. Interestingly enough, despite the ICWU’s origins in Cape Town, the relative stability of the Union of South Africa throughout Phase Two, thanks to its status as a self-governing dominion of the Windsor crown, and therefore greater capacity to crack down on dissident groups meant that ICWU’s base of support gradually transitioned to Northern and Southern Rhodesia, thus making the two colonies the heart of the fledgling African syndicalist and anarchist movement by 1929.

Just as the Nigerian Revolution had signaled vulnerabilities to the Young Baganda Movement, it indicated to the ICWU that the time for an anarcho-syndicalist (the dominant strain of socialist thought within the union’s ranks) uprising within the Rhodesias had arrived. ICWU miners in the Copperbelt Province of Northern Rhodesia voted to go on strike circa late June 1929, largely against poor conditions for native African mineworkers with the hope that events transpiring throughout Loyalist holdings would ensure that the strike would achieve more favorable conditions, however, as the settler colonial government of Northern Rhodesia, determined to maintain their strict political and economic dominance of the protectorate enforced through the policy of Direct Rule, made efforts to repress the Copperbelt strike, the ICWU branch of Northern Rhodesia opted to vote for a nationwide general strike on July 2nd, 1929, followed by a similar vote by the Southern Rhodesian branch on July 5th. Soon enough, the Rhodesia Strike encompassed workers of all occupations, who hoisted banners of crimson and black, a symbol of the revolutionary ambition of the ICWU.

As developments in Central Africa and the victory of the French Commune on the North African Front were watched with intrigue by the ranks of the ICWU, the Rhodesia Strike grew increasingly militant and ambitious as union chapters began to gauge a turning point in African history. Striking workers, especially within the Copperbelt Province, began to arm themselves out of self-defense, the ICWU journal, Black Man, proliferated essays promoting the vision of an anarchist society spanning the Rhodesias, and a handful of union chapters set up makeshift worker cooperatives with the hope of bringing about a self-managed industry administered by and for the native African working class of the region. All the while, the Rhodesian white ruling class grew increasingly wary of the general strike, fearing that they were about to be engulfed in the very same fate of the major European powers who now sported socialist iconography.

This all came to a head on July 30th, 1929, when peaceful, yet nonetheless armed, strikers at the Nkana mine of the Anglo-American Corporation within the Copperbelt Province began throwing stones and shouting stones at police officers. In a fit of panic, the officers fired into the crowd, and within seconds, the nonviolent strike transformed into an armed conflict between the forces of anarcho-syndicalism and imperialism, one which the more numerous strikers won with relative ease. The Nkana mine and surrounding community were completely occupied by ICWU, subsequently being collectivized into a mining cooperative and the Nkana Commune respectively. In their act of brutality, the police garrison at Nkana had ignited an anarcho-syndicalist revolution throughout the Rhodesias, with armed uprisings seizing control of mines throughout the Copperbelt Province over the coming days, culminating in the Northern and Southern Rhodesian wings of the ICWU both declaring a state of open rebellion against their colonial oppressors on August 4th, 1929.

The Zambezi War had begun.

ICWU forces would seize considerable territory within the coming days, fighting a guerrilla war in some places and uniting communities under an anarcho-syndicalist ideological arrangement in others, with the Copperbelt Province in particular being dominated by ICWU collectives by the end of the first week of combat. In territories like the Copperbelt, the ICWU became the de facto government, with the labor councils and regional communes alike serving as both constituent members of the general union and the governing entities of local economies and society respectively. The ICWU had therefore accomplished something that their libertarian socialist comrades in Europe had failed at in the face of statist socialism, that being the birth of an unprecedented large anarcho-syndicalist society, free from the chains of both the state and capital alike. Both regional and industrial administrations were managed through direct democracy, freely associated with each other to coordinate production, distribution, and defense, and strived towards replacing the market-based economics of liberalism with mutual aid networks. The patchwork of anarchist communities governed and defended by the ICWU, which established the Zambezi Liberation Army (ZLA) on August 8th as a means of collective defense, were colloquially nicknamed the Zambezia Free Territory by foreign observers, and quickly became a beacon of hope for a global anarchist movement struggling to stay afloat in a world increasingly dominated by the forces of authoritarianism.

Flag of the Zambezi Liberation Army, often regarded as the de facto flag of the Zambezia Free Territory as a whole.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the radical nature of Zambezia and the presence of ICWU chapters throughout southern Africa (many of which were banned), the Zambezi War triggered a much more aggressive response from Loyalist forces, with the Union of South Africa announcing a military intervention against the ZLA starting on August 13th, 1929 and the Bechuanaland Protectorate on August 16th, however, with the much of the Rhodesian working class on the side of the ICWU and the ZLA utilizing spontaneous guerrilla tactics that made its activities difficult to repress, the victory of an anarchist revolution in Rhodesia seemed imminent without backing from the wider Loyalist world. For now, however, the forces of the state and statelessness were to be bogged down in a war of attrition, yet another socialist revolution in an increasingly radicalized world. All the while, a steady trickle of anarchist and libertarian socialist volunteer forces left disappointed by the leftist revolutions in Europe arrived in ZLA-occupied territories, opting to fight for the freedom of Zambezia and a revolution that they could finally get behind.

Then, of course, there was the Belgian Congo. A colony infamous for its decades of brutality even compared to the horrors of other European regimes in Africa, the Belgian Colony quickly found itself in the position of being the sole holdout of the entirety of the Kingdom of Belgium following the outbreak of the Great War thanks to the rapid takeover of the small nation by the German Empire in accordance with the Schlieffen Plan. This left the Belgian Congo in a strenuous position, however, as France descended into civil war and the Belgian government was forced to flee from its exile in Sainte-Adresse to an exile in Leopoldville, the hope of a return of King Albert to Europe any time in the near future disintegrated alongside the French Third Republic. As limited support from the Entente to preserve the Belgian Congo began to dry up due to the alliance having bigger fish to fry on the frontlines of the Great War, the colony went on life support while its administration increasingly feared the potential retribution of a native populace mercilessly exploited for decades.

Enter Simon Kimbangu. The son of a traditional religious leader from the town of Nkamba, Kimbangu converted to Baptism in 1915 and went on to found his own ministry early 1921, where he amassed a large following and, according to his disciples, cured the sick, raised the dead back to life, and prophesied the liberation of black people. Kimbangu’s ministry ultimately evolved into its very own sect of Christianity, the Kimbanguist Church, whose members embraced Puritan ethics, including the rejection of violence, polygamy, withcraft, tobacco, alcohol, and dancing, and regarded Kimbangu himself to thre Holy Spirit. As Kimbanguism grew in support throughout the Belgian Congo and continued to advocate for the liberation of her inhabitants from the chains of imperialism, the church predictably earned the ire of colonial authorities, who saw the religious movement as a threat to their reign. Despite these fears, however, Belgian colonial administrators ultimately decided against arresting Kimbangu himself due to opposition from a handful of Protestant missionaries and the collapse of Entente authority in Europe at the time making more heavy-handed colonial practices increasingly risky.

While several Kimbanguists were arrested throughout the 1920s on the basis of sedition and a lack of recognition for the Kimbanguist Church as a legitimate religion gave the Belgian Congo the excuse to repress services and sermons by the sect by arguing that they were attacking a treasonous movement, Simon Kimbangu himself became untouchable as his followers grew in numbers and influence, thus meaning that any arrest of the religious leader would place the last holdout of the Kingdom of Belgium on the brink of insurrection. But by taking this more passive approach, Kimbanguism grew to a point where it undermined colonial rule anyway, with millions of Congolese civilians (primarily in the western reaches of the colony) adhering to the religion by 1929. If Kimbangu were to declare a holy war in the name of black liberation, there was little that could be done at this point. And with the African Spring raging throughout neighboring territories by this point, the opportunity for such a declaration was blatant.

At a service attended by hundreds of thousands of his supporters in Nkamba on June 23rd, 1929, Simon Kimbangu declared that the uprisings throughout French Equatorial Africa over the past two months indicated that his prophecy of the liberation of Africa originally made back in 1921 had finally come to pass, and therefore called on his supporters to wage a war against colonial oppression, starting with the elimination of the Belgian Congo. Almost immediately after Kimbangu’s declaration of war on the dying imperialists of Africa, his supporters took up arms against local police and military forces, bringing the town of Nkamba under the control of Kimbangu himself within a matter of minutes. From Nkamba, the disorganized and makeshift Kimbanguist army marched east, seizing Gombe Matande, then Kasangulu, and then finally the gates of Leopoldville itself, picking up more armed supporters in a crusade for liberation with every village that fell. By the time the sun had set over Africa on June 23rd, the capital of the Belgian Congo was under the control of Simon Kimbangu while King Albert and his government fled east to Luluabourg.

The following day, Simon Kimbangu would declare the Holy State of Zion (HSZ) with its capital situated in Leopoldville, now renamed to New Jerusalem, and called upon his supporters to rise up and fight to expand the Holy State throughout the entirety of the Congo and beyond. A Kimbanguist theocratic autocracy, Kimbangu was undeniably the absolute ruler, self-declaring himself the Spiritual Head of the Holy State, of what gradually evolved into a military junta over the coming days with the organization of the Holy Zionese Liberation Army (HZLA) under his guidance in the coming days. As the Belgian Congo hastily put together an army to counter the HZLA with whatever forces it had lying around in what became regarded as the Kimbanguist War, the stability of the colonial regime had finally been destroyed. By the end of June 1929, the Holy State of Zion occupied all Congolese territory to the west of New Jerusalem, and more territories were sure to fall in the coming days as Kimbangu’s crusade pushed eastward, thus rendering what remained of the Belgian Congo landlocked, and more and more Congolese answered his call for eliminating imperialist rule.

Soldiers of the Belgian Congo moving westward towards the Battle of Masi-Manimba, circa July 1929.

And so, by the end of the summer of 1929, the empires of the Entente were falling apart at the seams. Locally-run republics had asserted their sovereignty in Ubangi-Shari and Nigeria, the Protectorate of Uganda had descended into civil war, an anarcho-syndicalist revolution had consumed Rhodesia, the Belgian Congo was being overrun by a theocracy, and further protests for self-determination were bound to cause instability elsewhere throughout the African continent. In their hubris, the Entente member states had not only lost their homelands in Europe, but now stood to lose what remained of their vast colonial empires thanks to the revolutions of the African Spring. This significant threat was one of the driving factors for the Loyalists to ultimately sit down at the negotiation table with the Third International as authorities in Ottawa concluded that further engagements in Europe would result in further collapse in Africa. But the end of the reign of Western imperialism on the continent was not yet set in stone, for while the British and French exiles were incapable of preserving the chains of colonialism, one vanguard for the old order remained, one that had already proven its worth on the battlefields of Scotland.

The time to truly test the newfound great power status of the Second Empire of Brazil had arrived.

Pax Brasilia

“The sun has tragically set upon the British Empire, yet a new day emerges, and with it the sun now rises upon the Brazilian Empire.”

-General Getulio Vargas in a speech to the General Assembly of the Second Empire of Brazil, circa August 1929.

Warships of the Imperial Brazilian Navy on patrol in the southern Atlantic Ocean, circa September 1929.

The African Spring had made it blatantly apparent to the world that the empires of the exiled Entente were falling apart at the seams and would continue to do so without a rapid and heavy handed response. The simple fact of the matter, however, was that over a decade of combat in the Great War and the loss of their homelands had rendered these governments-in-exile incapable of bringing about this response individually. Without international support, the Entente’s grip on Africa was bound to collapse within a matter of months as murmurs of revolution proliferated throughout the continent’s repressed populace. It was this looming threat of total collapse that arguably forced the Empire of America to come to the negotiating table with the Workers’ Commonwealth and ratify the Treaty of Belfast, followed by a total Entente withdrawal from the Great War in the aftermath. In other words, continued engagement in the battlefields of Europe would result in the alliance’s destruction in the streets of Africa.

Perhaps nowhere was the threat of implosion more clear than in the Belgian Congo, where the Holy State of Zion waged a relentless crusade against one of the most brutal colonial regimes in pre-war history. By the time of the Entente’s withdrawal from the Great War in November 1929, the Holy Zionese Liberation Army had made considerable gains, having pushed along both the banks of the Congo River to the north while pushing along the Kasai River towards Luluabourg. A coalition of varying degrees of native support for the colonial regime, mainly stemming from a distaste for the Kimbanguist theocracy in the west, combined with the sheer size of the Belgian Congo kept the colonial state alive provisionally, but it was merely a matter of time until the entire region was under Simon Kimbangu’s thumb if the current circumstances of the conflict remained the same.

To make matters worse for the Belgian Congo, the colony began to descend into warlordism as its political institutions became increasingly unstable and the armed forces developed into the driving force in Congolese society in the fight against the HZLA. Armand De Ceuninck, who simultaneously served as the governor-general of the Belgian Congo, prime minister of the exiled Kingdom of Belgium, and Minister of Colonial Affairs in order to maintain an efficient apparatus of state, reigned largely without question over the Congo-Kasai province from Luluabourg and therefore maintained the traditional colonial hierarchy within the territory under martial law, however, the same could not be said of the other three Congolese provinces. It was in these territories that the vice-governor-generals, appointed by Ceuninck, reigned with little oversight and, over the months of the Kimbanguist War, evolved into de facto warlords.

Armand De Ceuninck, himself a veteran major-general of the Great War, had preferred the appointment of military officers to the vice-governor-generalships throughout the 1920s, and as a consequence, the civil bureaucracy of the Congolese provinces gradually became indistinguishable from military rule as the vice-governor-generals inserted themselves more actively into the affairs of local armed forces, which were likewise inserted into regional civil administration. Through kleptocracy, informal influence, and the cession of power by Ceuninck, the vice-governor-generals were effectively in charge of both their respective provincial battalions of the Force Publique and an assortment of local colonial militias, thus making them the ultimate military authority within their various provinces by the time of Simon Kimbangu’s declaration of the Holy State of Zion, albeit authorities who still remained loyal to Armand De Ceuninck and his government-in-exile. With the outbreak of the Kimbanguist War, the last illusions that the Belgian Congo had not succumbed to warlordism dissipated as Ceuninck directed the vast majority of what remained of the Force Publique under his command outside of Congo-Kasai to the frontlines in the fight against the HZLA, thus leaving the vice-governor-generals of the provinces of Equateur, Orientale, and Katanga in total control of their respective territories as military autocrats, only informally tied back to the edicts of Luluabourg.

It was this situation of chaotic warlordism that the Second Empire of Brazil confronted going into 1930 as its leadership debated intervention in Africa. For the people of most of the Entente’s member states, the ratification of the Treaty of Belfast was a bittersweet moment. On the one hand, the alliance’s exit from the Great War brought with it an end to the bloodshed, the trails of coffins, and the sheer tragedy of well over a decade of mechanized combat as those who managed to survive the horrors of the trenches at long last returned to civilian life. On the other hand, the Entente could not claim victory. At best, its members had fallen short of achieving their goals, and at worst (and more frequently) had been completely humiliated, destabilized, and confronted with the reality that their regimes would likely never step foot upon the European continent ever again. This was not, however, the situation faced by Brazil, whose soldiers returned home to celebrations of their empire’s newfound status as a global superpower capable of projecting strength throughout the world, a power whose armies had not only kept the Entente alive in the face of impossible odds but had participated in an invasion of Great Britain, something that had not been successful since the 11th Century.

Amongst the Brazilian high command, there was therefore both a capability and an interest in continuing military operations on behalf of Rio De Janeiro's allies, this time in Africa, as a means to preserve the Second Empire’s sphere of influence. Prime Minister Pedro Aurelio de Gois Montiero of Brazil, the stratocrat who had led his country into the fires of war out of nationalistic pride, predictably committed to involving the Imperial Brazilian Army in the preservation of exiled European empires, starting with the Loyalist holdings. The Treaty of Vancouver, ratified on December 3rd, 1929 officially brought Brazil into the Ugandan Civil War and the Zambezi War on behalf of Loyalist forces, placed all British colonies and protectorates in Africa under Brazilian military occupation, and committed Brazil to intervention in any future armed insurgencies against Loyalist rule in Africa. Gois Montiero’s junta signed a similar treaty with the French Fifth Republic in Abidjan only a few days later, thus bringing Petain’s rump state under Brazilian occupation and offering aid to the French in the Middle Congolese Civil War in the form of supplies, particularly aircraft.

Both of these actions were crucial pieces in the new Brazilian foreign policy, deemed the Gois Monteiro Doctrine. Unveiled to the world at a session of the General Assembly of the Second Empire of Brazil on December 12th, 1929, the Doctrine asserted that Brazil was to dedicate itself to the preservation of the remaining liberal regimes of the Entente and that the Southern Hemisphere was to be protected from socialist and fascist incursions alike, by force if necessary. In other words, much like how the Monroe Doctrine had unsuccessfully sought to secure the Americas as the United States’ exclusive sphere of influence over a century prior, the Gois Monteiro Doctrine effectively declared the South Hemisphere the exclusive sphere of influence of Brazil. Unlike the US of the early 19th Century, however, the Brazilians actually had the capabilities and military capacity to accomplish such a task, and as Gois Monteiro announced his new policy to the world, Brazilian warships were already on their way to the African coastline, carrying hundreds of thousands of soldiers with them.

Soldiers of the Imperial Brazilian Army stationed in the Protectorate of Bechuanland, circa January 1930.

The results of Brazilian deployments in Africa were mixed, at least at first. Getulio Vargas and Augusto Tasso Fragoso were put in charge of Brazilian efforts in Uganda and Rhodesia respectively, with both men expecting brief campaigns that would conclude by the end of the year. After all, Vargas and Fragoso had crossed the Atlantic Ocean to conquer Scotland, succeeding where few in history ever would. What were mere colonial insurrections compared to the might of the Imperial Brazilian Army? This hubris was soon found to be misplaced. Brazil’s armed forces had accustomed themselves to mechanized conventional combat during the Great War, and the simple fact of the matter was that suppressing rebellions and guerrilla warfare was the specialty of neither Vargas nor Fragoso. Within the initial stages of their engagements, both generals eventually found themselves bogged down in chaotic wars of attrition, failing to bring about the quick victory that Rio De Janeiro had anticipated.

Between the two Brazilian escapades in Africa, Getulio Vargas found the most success in his campaign against the Kingdom of Buganda. This was not necessarily due to General Vargas’ own merit, but rather because of the structure of the Baganda Army itself. Having largely spawned from defected local Loyalist forces, the Baganda armed forces were both rooted in and sought to emulate conventional military tactics, thus meaning that their organizational methods were familiar to the Brazilians. By the time a sufficient quantity of Brazilian forces had arrived in British East Africa in mid-January 1930, the Kingdom of Buganda had already conquered nearly all Ugandan subdivisions to the southwest of Lake Kyoga, now focusing on an invasion of Busoga to its east and Acholiland to its north. The initial offensive commanded by Vargas, even without large numbers on its side, managed to see quick success by uprooting the Baganda Army from the territory they occupied in the Kingdom of Busoga within a matter of mere days. The Battle of Bugembe on January 20th, 1930 saw Vargas secure a decisive victory over the severely outgunned Baganda Army within only a handful of hours, thus forcing the forces of Kabaka Daudi Chwa into a westward retreat that culminated in the complete expulsion of Baganda forces from territories to the east of the Victoria Nile at the Battle of Jinja on February 1st.

It was after this point that Vargas began to run into problems. The possibility of continuing the Busoga Offensive of January across the Victoria Nile soon fell apart as the Baganda destroyed any means of quick transport across the river while the size of the Baganda Army soon proved to be larger than expected and capable of fending off the relatively small Brazilian expeditionary force. A stalemate therefore emerged in the Ugandan Civil War, one that General Vargas sought to alleviate by requesting substantial reinforcements, however, even once these forces began to trickle into Uganda in late February 1930, the Brazilian war effort continued to face setbacks. The simple fact of the matter was that Kabaka Daudi’s war of liberation from the chains of colonialism became increasingly popular amongst Ugandans of all stripes as each day passed, and, ironically enough, Brazilian involvement in the Ugandan Civil War on behalf of the Loyalists only helped boost this growth in support. Even more so than the British, the IBA was viewed as a foreign occupying army, not to mention a sign that the Loyalists were particularly vulnerable due to their apparent reliance on a foreign military. As such, civilian disruptions to Loyalist supply lines became increasingly common going into March 1930, as did pro-Buganda acts of terror and insurgency behind enemy lines, all of which considerably hindered the efforts of Brazil.

Throughout March, the stagnation of the Ugandan Civil War continued. The Baganda Army held its ground despite the odds, and any beachheads secured by the IBA and allied Loyalist forces on the western banks of the Victorian Nile were quickly repelled. All the while, the Kingdom of Buganda attempted to make an offensive of its own by continuing its push into Acholiland, where it was believed that there were considerable sympathies to the Kabaka’s cause, however, this soon proved to be a miscalculation. Starting in early March 1930, the Acholi Offensive simply came too late into the Uganda Civil War to render any progress. With the exception of its western border with the Belgian Congo, all of Buganda was encircled with Loyalist territories, previously not much of a threat but now a brick wall due to the backing of the Imperial Brazilian Army. The Baganda Army made initial and relatively speedy advances into Acholiland, getting as far as Purongo when the town fell on March 15th, 1930, but this would prove to be the maximum extent of the Acholi Offensive. In the coming days, reinforcements from the Second Empire of Brazil completely undid Baganda progress on the Acholi Front, pushing the Kabaka’s forces back across the Victoria Nile by March 24th, 1930.

Therefore, going into April, the Kingdom of Buganda was a nation under siege on all sides. The Baganda Army had entrenched itself along all of its borders, turning the frontlines of the Ugandan Civil War into a scene ripped from the trenches of the Great War in Europe. All the while, General Getulio Vargas continued throwing men at the small African kingdom while suffering from consistent sabotage along his supply lines, declining Loyalist support, and a messy quagmire where boys a long way from their South American homes found themselves sitting in an encampment in the African savannah, a situation that was undeniably distinct, to say the least, from the supposed glory of Operation Poseidon. There was no question that the Kingdom of Buganda would eventually crack under the pressure of the Brazilian armed forces, but that didn’t mean that the process had to be pretty for the Brazilians, who had found out that the road to becoming a worldwide superpower entailed the unpleasant process of keeping the Entente empires on life support.

Neither Getulio Vargas nor Pedro Aurelio de Gois Monteiro would have any more of the war of attrition in Uganda at this point. After requesting the deployment of the Imperial Brazilian Air Force in the Ugandan Civil War for over a month, Prime Minister Gois Monteiro finally gave into General Vargas’ demand in early April, and by the middle of the month, bombers that had previously dropped paratroopers and bombs alike upon Scotland less than a year prior began to arrive en masse in East Africa. While Gois Montiero had initially been convinced that the Ugandan Civil War would be a quick engagement where aerial forces were unnecessary, March 1930 had proven this assumption to be incorrect, and now that Vargas was finally given the permission to reign hell down upon the Kingdom of Buganda, he would not waste the opportunity to bring upon a rapid and brutal end to the quagmire. The Baganda Army lacked any significant anti-aerial equipment, let alone an air force, which meant that General Vargas’ bombing campaign was remarkably devastating. Neither military positions, supply lines, nor cities were safe from an indiscriminate bombardment, and within less than a week, all of Buganda was burning as hundreds of firebombs descended upon the rebel state.

Bombers of the Imperial Brazilian Air Force during the Ugandan Civil War, circa April 1930.

Vargas’ bombing campaign, eventually nicknamed the Burning of Buganda, was as horrific as it was effective. The Baganda Army was excellent at fending off against larger and more well-armed ground forces through a combination of ingenuity, utilizing local geography to their advantage, and popular support throughout Uganda, however, the simple fact of the matter was that Buganda lacked any means of retaliating against the IBAF, thus leaving Kabaka Daudi’s rebellion at the mercy of the weapons that had expelled the finest of the Workers’ Commonwealth from Scotland. The Baganda defenses on both the Acholi and Bugosa fronts were decimated within a matter of days following the beginning of the Bombing of Buganda, thus allowing for the IBA to cross the Victoria Nile and deploy paratrooper forces where necessary relatively unopposed.

All the while, the destruction of Baganda supply lines and other key infrastructure left the Kingdom incapable of waging a significant war effort. Morale plummeted amongst soldiers and civilians alike, and while Kabaka Daudi Chwa pledged to never surrender to the imperialist brutes knocking at his doorstep, it was impossible to ignore the reality that he would soon not have much of a choice. Even Buganda’s already-strained agricultural production was a victim of the Burning of Buganda, and when the food your army is dependent on is on fire, hope for victory is nigh futile. On April 21st, 1930, the Imperial Brazilian Army, alongside a collection of smaller Loyalist forces, began to lay siege to Kampala, already the target of relentless bombardment for several days. What remained of the Buganda Army put up a good fight, but the outcome of the Battle of Kampala had been decided long before the first fighting in the Baganda capital began. After two days of street to street combat, the last of the Baganda forces were defeated on April 23rd, the flags of the Empire of America, United Kingdom, and Second Empire of Brazil were all hoisted above the ruined Kampala, and Kabaka Daudi and the leadership of the Young Baganda Association were captured. The Second Empire of Brazil had won the Ugandan Civil War for her loyalist allies.

General Augusto Tasso Fragoso’s involvement in the Zambezi Ware was far more complicated, to say the least. The Baganda Army largely mimicked the structure of a conventional military force, but the Zambezi Liberation Army was anything but. Decentralized in its institutions and stateless in its loyalties, the ZLA was a master of decentralized warfare to an extent that not even the Workers’ Model Army had succeeded at. Established by the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union to both defend and uphold the anarcho-syndicalist ideals of the Zambezia Free Territory, the ZLA operated along a federalist model where local regiments were directly managed by their respective communes, however, the governing committee of the ICWU could override local orders and communes could confederate with each other to coordinate military activities on a wider level. This gave the ZLA a very elastic means of organization, focusing on local defense but coordinating larger efforts when necessary, which in turn allowed for it to rapidly retaliate and organize against enemies with superior manpower numbers.

Even for the infamous Fragoso, this posed a serious challenge. While he expected the ZLA to be tactically similar to the Workers’ Model Army, the reality on the ground was far more chaotic. The inability of local colonial forces backed by South Africa to defeat the ZLA prior to Brazilian intervention had allowed for the Zambezia Free Territory to encompass the vast majority of Northern Rhodesia since its initial revolution in August 1929, with affiliated collectives of varying degrees of influence being scattered throughout Southern Rhodesia and the outskirts of Bechuanaland. One of the greatest victories of the ZLA was arguably the takeover of Salisbury, the capital of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia, by ICWU revolutionaries in December 1929 after a local general strike turned into an anarchist uprising under the banner of the Free Territory and the subsequent declaration of the Salisbury Commune on December 15th, 1929 as a constituent collective of the ICWU. While the militias of Salisbury faced a relentless siege by Loyalist forces, they nonetheless held out for weeks, barricading themselves into their city, before a ZLA offensive from the northwest managed to link with Salisbury on January 19th, 1930, just as the first Brazilian forces began to arrive in Rhodesia.

General Fragoso therefore faced a scene where his anarchist enemies were not just holding off colonial forces, but were arguably winning. Entering the frontlines of the Zambezi War via South Africa, the Brazilians initially focused on eliminating ZLA cells in Bechuanaland, and they proved to be successful in this regard, at least initially. While ZLA-occupied territory in Bechuanaland was quickly eliminated within the closing weeks of January 1930, local support in this previous anarchist fortresses remained on the side of the ICWU, which meant that civil disobedience and small-scale insurgencies posed a continuous setback to the IBA’s war effort. Yet the tenuous situation in Bechuanaland was ultimately both a victory for Brazil and little more than a mere taste for the quagmire that lay ahead. Upon arriving in Southern Rhodesia, Brazilian forces found themselves bogged down in a campaign to keep down ZLA militants, who continuously popped up throughout the country. To make matters even more challenging, the black Rhodesian majority was clearly on the side of the Zambezi Free Territory, far more so than in Bechuanaland, which meant that sabotage and civil disobedience proved to be relentless obstacles, even within Loyalist holdings.

Augusto Tasso Fragoso and his men therefore found themselves in an unfamiliar form of combat, where there were no frontlines, but rather a seemingly perpetual slew of uprisings that needed to be repressed before moving onto the next insurgency. Throughout February and March 1930, the Imperial Brazilian Army made an attempt at leading a conventional offensive towards retaking Salisbury and the collection of communities that linked it back to the ICWU’s base of power in Northern Rhodesia, however, this too was bogged down to forces necessarily being spread thin to deal with guerrilla insurgencies and spontaneous attacks on infrastructure, namely supply lines. In this sense, while General Fragoso made an attempt at waging a type of war he was familiar with, the nature of the Zambezi War effectively turned his men into a military police force throughout Southern Rhodesia, sieging ZLA encampments, patrolling occupied towns and cities, violently breaking up strikes, and even participating in raids alongside Southern Rhodesian authorities to arbitrarily arrest suspected anarchist sympathizers.

A soldier of the Imperial Brazilian Army during a raid on a Zambezi Liberation Army encampment in Southern Rhodesia, circa March 1930.

The Zambezi War therefore divulged into a war of attrition, where hundreds of young Brazilians anticipating a repetition of the glories of the British Front instead found themselves cowering in Rhodesian bushes or bursting into the homes of innocent families, all to uphold a foreign colonial regime. Even as their isolated communes in Southern Rhodesia were routed out, the ZLA maintained high morale and public support, confident that it was holding its own against the great imperialist powers of the Southern Hemisphere, while morale amongst Fragoso’s ranks dropped for the same reason. With the beginning of the Burning of Buganda, however, Fragoso sought to mimic Vargas’ success and ultimately persuaded Prime Minister Gois Monteiro to lease out IBAF aircraft to the war effort in Rhodesia in late April 1930. As the first planes arrived in early May, General Fragoso set out attempting to emulate the Burning of Buganda, unleashing a total war upon the Zambezi Free Territory, however, even this strategy found only limited success. Unlike the more conventional Baganda Army, the decentralized and guerrilla nature of the ZLA allowed for it to more easily evade bombing attacks, either by hiding in the Rhodesian flora or simply sprouting up spontaneously in a way that IBAF bombers could not predict.

Even so, the Zambezi War did begin to see some progress on the part of Brazil and her Loyalist allies. The more conventional tactics of the ZLA surrounding Salisbury and connecting the city back to Northern Zimbabwe were particularly vulnerable to bombardment campaigns, and as a hellfire of bombs fell upon the occupied Southern Rhodesian capital throughout May 1930, cracks in the armor surrounding Salisbury began to emerge, thus allowing for General Fragoso to launch the Mashonaland Offensive, starting with a swift victory at the Battle of Beatrice on May 10th, 1930. From here, Brazilian armored infantry began a quick push northwards towards Salisbury as bombers ensured from above that enemy territory was depleted of its manpower and critical infrastructure. After a series of victories, the Battle of Salisbury began when the Imperial Brazilian Army approached the already heavily-bombed city from the southwest on June 5th. After five days of vicious street to street urban warfare, the ZLA was uprooted from Salisbury on the morning of June 10th, 1930, therefore bringing the ruined city under the military occupation of the Imperial Brazilian Army.

The Battle of Salisbury had not, however, come without a gruesome cost for civilians. The capital city and the surrounding area had been bombed to a crisp, resembling a shattered city of the Great War’s European frontlines by the time the flags of Loyalist forces had been hoisted. Not only were hundreds of civilians executed by the indiscriminate bombing campaign of the Imperial Brazilian Air Force, but crucial civilian infrastructure had been obliterated in the process. Homes, hospitals, and schools had all been destroyed, leaving Southern Rhodesia in the midst of a humanitarian crisis well after the end of the Battle of Salisbury. Wealthy white Rhodesians, who had suffered relatively little during the Mashonaland Offensive, regarded Augusto Tasso Fragoso to be a hero of their country, however, the black majority became increasingly infuriated towards the IBA, and guerrilla insurgencies by the ZLA continued throughout Southern Rhodesia past the fall of the Salisbury Commune. But for the Brazilians, the focus had changed. Their guns turned towards Northern Rhodesia, where they faced yet another war of attrition against an embattled enemy that had mastered guerrilla warfare over the coming months. Nonetheless, one thing had become apparent; Pax Brasilia was a peace forged in the fires of war and repression.

Brazilians in the Congo

“How the mighty have fallen.”

-Private comment of Brazilian Prime Minister Pedro Aurelio de Gois Montiero, circa June 1930.

Soldiers of the Belgian Congo fighting in the Kimbanguist War, circa May 1930.

As the Second Empire of Brazil was embroiled in the conflicts of Uganda and Rhodesia, the Kimbanguist War raged on. The armies of increasingly autonomous warlords clung onto eastern Congo, only on paper in the name of the exiled Belgian monarchy, while Simon Kimbangu’s theocratic empire expanded its reach in the west. The Brazilians had recognized the threat posed by the Holy State of Zion from the get-go, however, aiding the Belgian Congo was a logistically difficult task. The HSZ’s control over the western Congo left the Belgian warlords landlocked, either bordering hostile states or rebel-held territories, with the notable exception of the Portuguese colony of Angola. The preservation of the Belgian Congo and the elimination of the Holy State were both goals of Rio de Janeiro, however, little could be done until the fallout of the African Spring in Loyalist holdings could be better contained, particularly in Uganda, which bordered the northeastern Congo and could therefore provide Brazil with secure access to her ally.

From the beginning of the Gois Monteiro Doctrine to the fall of the Kingdom of Buganda, Brazilian involvement in the Kimbanguist War was restricted to the funneling of arms and other supplies through Angola and the naval blockade of the Holy State’s Atlantic coastline, the latter of which bore similarity to the joint Brazilian-Loyalist blockade of the Nigerian Confederation, an invasion of which was deemed more trouble than it was worth for the time being. The conclusion of the Ugandan Civil War circa late April 1930 finally gave both the secure entry point into the Belgian Congo and reserve of military forces in Africa in the form of Getulio Vargas’ army needed to engage effectively in the Kimbanguist War. On May 20th, 1930, in agreement with Governor-General Armaund De Ceuninck, General Vargas was ordered to mobilize his forces against the Holy Zionese Liberation Army, entering the Orientale province on his way to the frontlines in Equateur.

The first chapter in the history of the Brazilian Congo had begun.

The Imperial Brazilian Army proved to be a much-needed crutch for the Belgian Congolese warlords. By the beginning of Brazil’s deployment into the Congo, the Holy State of Zion controlled all territory to the west of the Kasai River, had seized considerable territory along the Congo and Ubangi rivers, and was continuing to efficiently push into the Congo-Kasai and Equateur provinces at such a speed that Luluabourg risked Zionese occupation well before the end of 1930 without foreign aid. Hoping to launch a counteroffensive into the heart of Zionese-held territory and prevent the fall of Luluabourg, the bulk of Brazilian forces in the Kimbanguist War, including General Vargas himself, were initially deployed on the Kasai Front, with the Imperial Brazilian Army arriving in full front in the Congo-Kasai province by the beginning of June 1930. Once his army had fully assembled, Vargas was ready to start yet another military campaign. The general had learned from the errors of the Ugandan Civil War, becoming convinced that air raids were the key to quick and decisive victories against the insurrections of the African Spring and therefore utilized whatever IBAF forces he could be spared, an increasingly limited number as Augusto Tasso Fragoso continued to be bogged down in the Zambezi War, to bomb the Holy State of Zion to a crisp before ground forces were committed to attempting an actual offensive across the Kasai River.

The bombardment of the Holy State was as cruel as it was effective. Even when facing a limited aerial force relative to what had terrorized Uganda and the Rhodesias, the HZLA had little means of fending off against IBAF bombers, which inflicted devastating damage on the Zionese frontlines. A combination of utilizing firebombing and and poisonbombing tactics, both of which were intended to inflict the maximum amount of widespread decimation with as few aircraft as possible, not only stopped the HZLA offensive in its tracks, but demolished its frontlines, thus allowing for Vargas to initiate his offensive across the Kasai River. The so-called Kasai Offensive thus began circa mid-June 1930, with the IBA and allied Belgian Congolese forces breaking through HZLA defenses along the southern banks of its namesake river, just to the west of Luluabourg. Much like the Baganda and Zambezi before them, Zionese supporters waged guerrilla insurgencies in territory that fell under Brazilian occupation while Kimbanguist fifth column insurgencies and terrorist attacks behind the frontlines slowed down the war effort against the HZLA, however, the rapid progress made by Vargas in the onset of the Kasai Offensive nonetheless managed to cross the Loange River by the end of June.

Soldiers of the Imperial Brazilian Army utilizing a flamethrower to burn down flora along the Loange River, circa June 1930.

To the north of the Kasai Front, joint Brazilian-Belgian operations likewise saw fortunes turn for the HZLA. Waterways once held by Kimbanguist crusaders were besieged by enemy forces manned by the soldiers who had fought on some of the Great War’s most fearsome battlefields, and already tenuous-held positions along the northern reaches of the Congo and Ubangi rivers were quickly uprooted by the might of the Second Empire of Brazil. By the end of June 1930, the Holy State of Zion had lost its control over any foothold along the Ubangi River and was restricted to controlling the banks of the southern half of the Congo River, although guerrilla efforts by Kimbanguist sympathizers continued in Belgian-conquered northern territories. All the while, Brazilian aircraft carriers in the Atlantic Ocean and military bases in whatever remained of French Equatorial Africa, itself facing an insurgency in the form of the African People’s Liberation Army, were utilized as points from which to conduct firebombing campaigns of the heartland of Holy State-controlled territory in the western Congo. Such bombing runs didn’t serve the purpose of paving the way for anything as bold as an amphibious assault of Samuel Kimbangu’s Zion, however, they did serve the purpose of inflicting considerable damage on Zionese-controlled infrastructure, no matter the horrifying cost such campaigns had on civilian populations.

Both in terms of military activities and upholding the allied war effort, the Kimbanguist War soon spilled over into neighboring colonies. Spiritual Head Simon Kimbangu would order retaliatory attacks on military bases in the French colony of the Middle Congo, from which Brazilian airstrikes were carried out, starting in early July 1930, however, these early border crossings were very quickly undone by a combination of the forces of the Second Empire of Brazil, French Fourth Republic, and the local Congolese Protection Army, and after being occupied by the HZLA for no more than four days, Brazzaville returned to French hands on July 6th. Critically, the short-lived and unsuccessful Middle Congo Offensive brought the Philippe Petain’s French Republic into a state of war against the Holy State, thus expanding the anti-HZLA coalition to encompass a major regional power. While the French remained too embroiled in the Middle Congolese Civil War and keeping their sick empire alive to dedicate considerable forces to anything beyond fortifications along the Congo River, the entry of France-Dakar into the Kimbanguist War nonetheless played the crucial role of increasing Brazilian military operations in the western Congo, thereby effectively opening up a second front (a war of attrition for the time being) and turning the conflict into a regional affair rather than a civil war, with dedicated Kimbanguists and disgruntled African nationalists alike throughout central Africa rallying to the cause of the HZLA by joining the militia as volunteer forces.

To the south of the Holy State of Zion, the Brazilians likewise sought to utilize a neighboring colony to its advantage, albeit without opening up another frontline of the Kimbanguist War. The Province of Angola, a Portuguese colony since the 16th Century, held considerable strategic value should it enter the conflict given its lengthy border with Zionese territory, but what the Brazilians were most interested in was the Benguela Railway, a route spanning from the Atlantic port city of Lobito to the Angolan-Congolese border at Luau. Seeing an opportunity to bypass the movement of troops around the Cape of Good Hope and through East Africa to the frontlines of the Kimbanguist War, the Gois Monteiro ministry purchased the Benguela Railway Company, headquartered in Ottawa at the time after having been British in origin, on July 10th, 1930 and subsequently signed the Treaty of Lobito with Portugal only a few days later to permit the unrestrained transport of Brazilian military forces and resources along the Benguela Railway, as well as the patrolling of the railroad by the Imperial Brazilian Army, thus effectively placing the line under Brazilian military occupation.

The administration of the Benguela Railway was quickly placed under the private ownership of the Companhia de Estrada de Ferro Benguela (CEFB), a state-owned enterprise that nonetheless permitted considerable investment by private shareholders of the emerging Brazilian industrialist elite class so long as a majority of shares remained in the hands of the Brazilian state. Under the management of the CEFB, the Benguela Railway funneled thousands of troops and countless weapons to the Angolan-Congolese border, becoming the critical artery of the Brazilian war effort against Simon Kimbangu’s theocratic military junta. Construction on the railway to expand it westward into the Belgian Congo likewise began in August 1930, with Congolese peasants and Brazilian migrant workers alike arriving in the Congo-Kasai province to work under miserable conditions with little pay and poor sanitation, united in common exploitation by Brazil’s fledgling imperialism, although such efforts would take longer to complete than the Kimbanguist War itself.

All the while, even as the Holy State of Zion became increasingly encircled by Brazil and her sphere of influence of decaying empires, ever more condemned to decisive defeat by the day, Spiritual Head Simon Kimbangu refused to capitulate and insisted that his holy war against the foreign infidels must continue. Under the autocratic reign of Kimbangu, the Holy State was little more than an authoritarian military junta, with the spiritual head being vested with total authority over the apparatus of state, development of laws, and the armed forces. HZLA militias were directed by the supreme leader to serve as a theocratic military police, enforcing the edicts of the Kimbanguist religion upon occupied territories, while adjunct spiritual heads were appointed by Kimbangu himself to administer local military forces, govern controlled territories, and enforce theocratic rule. Under the strict reign of the Holy State’s military junta, the public practice of religions other than Kimbanguism, the consumption of intoxicating substances, and dancing in public were all deemed criminal offenses, religious education was made mandatory, and attendance to Kimbanguist religious services was promoted, or, in some occasions, enforced, by local authorities.

Spiritual Head Simon Kimbangu of the Holy State of Zion giving a speech to supporters in New Jerusalem, circa July 1930.

Perhaps in contradiction to its authoritarian theocratic regime, the Holy State of Zion was simultaneously an experiment in African anti-imperialism, with Simon Kimbangu himself repeatedly insisting that he foresaw the emancipation of the continent from the chains of Western colonial rule. The vata village system, an institution from the days of the Kingdom of the Kongo whereby land was collectively held by villages and its wealth was redistributed roughly equally amongst its inhabitants, was restored, albeit with village chiefs replaced by unaccountable and authoritarian administrators appointed within the Holy State’s hierarchy. Private property itself was uncommon within Zion, with only a handful of exception

s permitted by Kimbangu. The Holy State therefore operated along the lines of a centrally-planned economy, and one that tended to allocate resources amongst its civilians relatively equally, a refreshing economic system, to say the least, to a populace that had long been oppressed by the brutal jackboot of the imperialism and laissez-faire capitalism of the Belgian Congo. The Holy State may have been a deeply authoritarian society, but so too was the Belgian Congo, and at least the Holy State tried its best to ensure that you wouldn’t go hungry.

While the Holy State of Zion’s political institutions largely stayed intact, even on the brink of defeat, the institutions of the Belgian Congo were beginning to unravel, even on the brink of victory. Progress on the Kasai Front throughout the summer of 1930 did not mean that the warlord system developed in the Congo would suddenly vanish, and no amount of Brazilian military support alone could hold together the fundamentally unstable arrangement that was the structure of the Belgian government-in-exile, a chicken without its head. The increasingly tenuous warlord system of the Belgian Congo, once created by Armand De Ceuninck out of strategic necessity more than anything, now threatened to bring the whole colony crashing down as the governor-general began to make moves attempting to reconsolidate his rule over the colonial regime. In an effort to sustain the last push of the war effort against the HZLA and send a clear message to the Congolese warlords of who was in charge, Ceuninck levied a number of taxes and conscription measures on warlord-controlled provinces throughout August 1930. This predictably sparked considerable backlash from the vice-governor-generals of the Congolese provinces, yet no one was more vocal in their opposition than Louis-Napoleon Chaltin, the stratocrat of the Orientale province.

A veteran of the Congo-Arab War of the 1890s, Chaltin was now an elderly career soldier who had succeeded General Jules Jacques de Dixmude, an enthusiastic advocate for and enforcer of the colonial brutality of the Congo Free State, as the vice-governor-general of Orientale following his death in 1928 and largely continued the ideological legacy of his predecessor. Chaltin was nostalgic for the days of King Leopold II’s nightmarish regime, and restored many of its worst characteristics, including brutal retribution against natives for failing to meet strict quotas, such as burning villages and amputation. The atrocities in Orientale had largely been ignored by Armand De Ceuninck and his allies abroad, both out of a necessity to keep Chaltin on their side and a more cynical disinterest in what was going on under the warlord’s reign. Now, Ceuninck’s tolerance of Chaltin had come to bite him back when the latter publicly condemned the new taxes and conscriptions as a violation of provincial autonomy and placing a burden on the Congolese subdivisions, thus ceasing to pay forward either measure starting on August 20th, 1930. This was, in effect, Orientale’s complete rejection of the authority of the central Congolese government, and paramount to treason in the eyes of Armand De Ceuninck, who ordered the arrest of Louis-Napoleon Chaltin.

Having already turned Orientale into a polity de facto sovereign from the authority of the Belgian Congo, Vice-Governor-General Chaltin had little qualms with ordering his forces to resist his arrest, resulting in the massacre of the squad sent to apprehend Chaltin on August 22nd, 1930. With the blood of Congolese soldiers now on his hands, the time for Chaltin to act against Ceuninck had arrived, and only two days after his failed arrest, the vice-governor-general led a regiment of his forces into Congo-Kasai with the intent of marching on Luluabourg and staging a coup d’etat. Given Chaltin’s acts of defiance, however, Ceuninck had already anticipated an armed attack against his regime by Orientale forces, and the putschists were intercepted at Lunga, just to the west of the border between Congo-Kasai and Orientale. The Battle of Lunga concluded in a decisive victory for Ceuninck, but Louis-Napoleon Chaltin nonetheless led what remained of his men into a retreat back to Orientale, where he proclaimed the Ceuninck government to be illegitimate on August 25th, 1930 and declared a state of war against the regime of the Belgian Congo, thus beginning the Congolese Civil War.

Vice-Governor-General Louis-Napoleon Chaltin of the Orientale province.

While Chaltin framed his military campaign as one intended to depose a despot who had violated the autonomy of his constituent provinces, Chaltin himself was as much of, if not more so, an autocrat as Armand De Ceuninck, and it didn’t take a genius to figure out that Chaltin’s civil war was little more than a ploy to accumulate power and take control of the Belgian Congo for himself. In other words, the Congolese Civil War was not a clash of ideologies but rather a spat between competing warlords, with all other casus bellis being little more than formalities to present to the international community. It was easy to see why Chaltin was so confident that his gambit would succeed; putting aside the Brazilian reinforcements, Congo-Kasai’s actual military capacity was quite limited and realistically couldn’t divert its forces between the Holy State of Zion in the west and the “Chaltin Clique”, as forces loyal to the Orientale stratocrat came to be known as, in the east.

To further stack the deck in Chaltin’s favor, the warlord vice-governor-generals of Equateur and Katanga were similarly disgruntled with the taxation and conscription measures of August 1930, so there was reason to believe that they would rally to Chaltin’s cause. Surely enough, Vice-Governor-General Antonin de Selliers de Moranville of the Katanga province declared war on the “Ceuninck Clique” on August 27th, although Emile Dossin’s Equateur province, which still remained vulnerable to incursions by the Holy Zionese Liberation Army and therefore viewed aligning with the Chaltin Clique as more of a liability in terms of the affairs of the Kimbanguist War than anything, chose to stay loyal to Luluabourg. Decent progress was made early on by the Chaltin Clique, even if reinforcements deployed by Congo-Kasai and Equateur gradually began to slow down progress. But every regiment sent to fight in the Congolese Civil War by the Ceuninck Clique was a regiment diverted away from the war effort against the HZLA, and with the Chaltin Clique both withdrawing its forces from the conflict against the Holy State and closing routes through Orientale utilized by the Brazilians to supply the Belgian Congo, the forces of Simon Kimbangu began to retake ground, with the HZLA seizing control of the Loange River yet again circa early September 1930. At this rate, if the Chaltin Clique didn’t vanquish Armand De Ceuninck, surely the Holy State of Zion would.

The outbreak of the Congolese Civil War predictably heightened the strain placed on the Imperial Brazilian Army, which now found itself having to considerably concentrate for the loss of forces reallocated to the fight against the Chaltin Clique. The regime of Gois Montiero still viewed the Ceuninck Clique as its sole legitimate ally that it had obligations to preserve the territorial integrity of, thus shutting down any debates to start backing Louis-Napoleon Chaltin or withdraw from the Congo altogether, however, the fact of the matter was that the Congo Wars were becoming a logistical nightmare for the Brazilian high command to oversee. Seeing an opportunity in the otherwise perilous situation of the Congo Wars, Pedro Aurelio de Gois Montiero proposed a treaty to Armand De Ceuninck whereby the Belgian Congo would become a protectorate of the Second Empire of Brazil, thus ceding control over its armed forces and foreign affairs to Rio de Janeiro and allowing for the imposition of taxes by the Brazilian state upon its populace.