Given that I’ve already delved into Asian independence movements in previous chapters, the next chapter will shed some light on African independence movements. What I’ll say for now is that they definitely exist, but the fact that most of Africa’s been neutral throughout the Great War thus far has meant that armed rebellions aren’t as big of a deal as they were in OTL yet. As for the Empire-in-Exile, the fact that it’s both neutral and has a relatively effective military means that it’s actual pretty stable. The Kaiser’s obviously not in a great position, but what remains of his empire also isn’t on the brink of collapse.What are the various independence movements up to? I know that India broke free after a civil war and Canada and Algeria are playing the roles of hosting a Governments in Exile but what about the rest. Also how is Kaiser Wilhelm II doing following the Fascist Coup and establishment of the Heilsreich?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Man-Made Hell: The History of the Great War and Beyond

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 30 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twelve: Defend of Die - Part Two Interlude Eleven: Europe Circa November 1929 Interlude Twelve: Scrapped Content Chapter Thirteen: A Bold New World Chapter Fourteen: Growing Storm Clouds Chapter Fifteen: Those Who Escaped Chapter Sixteen: A Twist of Fate Man-Made Hell: The Modern Tragedy Novel ReleaseHow long can the red hordes keep throwing themselves at the Germans. Aren't they already scraping the barrel for all the bodies they can find.

Both sides are gradually reaching that point where new manpower is becoming a rare resource, but in the case of the Third International in particular, there are a few things keeping them afloat. Both the French and Russians have adopted tactics similar to Blitzkrieg that has, at least for the time being, allowed for them to substantially reduce casualties on their own side. The Eastern Front is in a particularly good situation due to recently independent socialist states in South Asia now sending troops and resources to Europe.How long can the red hordes keep throwing themselves at the Germans. Aren't they already scraping the barrel for all the bodies they can find.

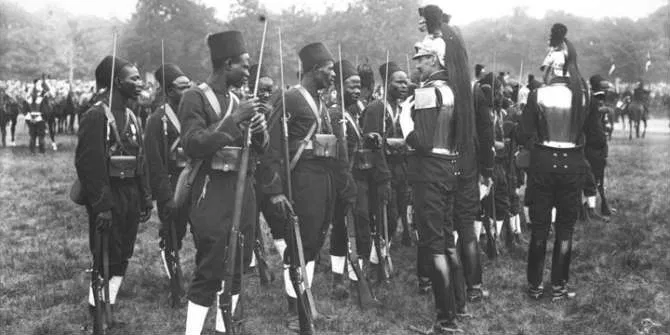

While there hasn't been fighting in Africa, IIRC the colonial empires HAD been recruiting colonial troops and using the colonies' resources to fuel the war effort, so I'd guess the natives would still get rather riled up. Will the chapter delve a bit into what the exiled empires' relations with the natives are?Given that I’ve already delved into Asian independence movements in previous chapters, the next chapter will shed some light on African independence movements. What I’ll say for now is that they definitely exist, but the fact that most of Africa’s been neutral throughout the Great War thus far has meant that armed rebellions aren’t as big of a deal as they were in OTL yet.

That's true. And yes, the next chapter will get into empires' relations with their colonies' natives.While there hasn't been fighting in Africa, IIRC the colonial empires HAD been recruiting colonial troops and using the colonies' resources to fuel the war effort, so I'd guess the natives would still get rather riled up. Will the chapter delve a bit into what the exiled empires' relations with the natives are?

I'm curious what sort of people will pop up- this is well before OTL's independence movements in the colonies, and you do have a talent for finding obscure figures to play significant roles.That's true. And yes, the next chapter will get into empires' relations with their colonies' natives.

I'll see who I can find. I remember writing a TL a few years ago where a handful of African countries became independent in the 1920s and 1930s, and it was definitely a bit of a challenge to dig up leaders for said countries.I'm curious what sort of people will pop up- this is well before OTL's independence movements in the colonies, and you do have a talent for finding obscure figures to play significant roles.

Just caught up, and my first thought was: what a crazy world to live in! @ETGalaxy, I admire your ability to write long, information-dense chapters which are still a treat to read. The Man-Made Hell-verse is rather bloody and dystopian (at least IMO) but it's also got a lot of creativity and originality behind it. Colour me impressed; I eagerly await more.....

Thank you so much! I really do appreciate the kind words, and it's comments like this that absolutely make my day.Just caught up, and my first thought was: what a crazy world to live in! @ETGalaxy, I admire your ability to write long, information-dense chapters which are still a treat to read. The Man-Made Hell-verse is rather bloody and dystopian (at least IMO) but it's also got a lot of creativity and originality behind it. Colour me impressed; I eagerly await more.....

Hello everyone! I want to apologize for the long wait for the latest update, as I know it's definitely been awhile. I decided to wrap up all of Phase Two in this update, and suffice to say that means the next update is very lengthy. Hopefully Chapter XI will be well worth the wait, but in the meantime, here's the introduction to the chapter in order to give people a bit of a sneak peak into what's coming up:

“It is here in Berlin that the fate of our empire will be determined. It is here that we will defend the city or die in the attempt.”

-General Erich Ludendorff of the Deutches Heilsreich, circa March 1928.

The Brandenburg Gate prior to the Battle of Berlin, circa February 1928.

“...Your Majesty?”

“What is it Anton?”

“The Fuhrer has called the Palace and would like to-”

“Tell Mr Hugenberg that I am unavailable at the moment.”

“...Of course, your Majesty.”

And with that, Kaiser August Wilhelm was left alone once again.

It was this solitude that the Kaiser had become so accustomed to in recent months, ever since he and the Fuhrer had transitioned from a close friendship to a bitter political rivalry. Their conflicting approaches to the Western Front had infuriated Hugenberg, who had more or less ruled as Germany’s unquestioned autocrat since the Heilungscoup. August Wilhelm’s total war strategy had certainly stalled the Third International’s offensive into the Rhineland, however, thousands of German civilians had died at the hands of the Luftsreitkrafte in the process. For many within the DVP elite, this apparently crossed a line. For Hugenberg, the line was crossed when August Wilhelm had the audacity to turn members of the German high command against him.

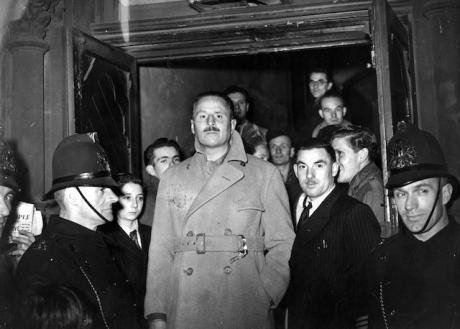

Since October, Hugenberg had been scolding the man who was officially his emperor but was in reality, at least within the framework of the German Fatherland Party, his subordinate for stepping out of line. Time and time again, the Fuhrer would call the Royal Palace to belittle the decisions of August Wilhelm, lambasting the Kaiser as “volatile,” “brash,” and “ignorant” more times than he could count. Eventually, August simply started ignoring Hugenberg’s calls when he could, and everytime the Fuhrer did get an audience with his aristocratic counterpart, it was becoming more and more clear to August that Hugenberg was becoming increasingly desperate. The fact of the matter was that the Great War was being lost under Alfred Hugenberg’s watch, and the knives within the Reichstag were beginning to tilt towards the Fuhrer. Someone needed to take the blame for the losses in both the east and the west, and Hugenberg was running out of military officers that he could throw under the bus.

Kaiser August Wilhelm simply fueled the flames of the DVP’s gradual turn on their leader. After all, as the head of state of Germany, August was the one who stood to benefit the most from Hugenberg’s deposition. With his rival out of the way, Germany could return to absolute monarchism yet again (this time, of course, mixed with the ultra-totalitarian chauvinism of fascism), an age that had preceded the days of even Otto von Bismarck. August’s game of political intrigue with Hugenberg was not, however, exclusively motivated by ideological differences. To the Kaiser, this was all personal. Hugenberg had once been more than a mere political ally of August, for he had been a mentor and a close friend. When the then-Prince August Wilhelm found himself at odds with his fellow Hohenzollerns, Hugenberg became the sole man of power in all of Berlin who he could trust.

And now Hugenberg dared to betray that sacred trust? Dared to betray the will of his Kaiser?

Such treason simply would not stand. Alfred Hugenberg may have committed himself to the supremacy of the Fatherland, but as the German Emperor, August Wilhelm was the Fatherland. By the grace of God, all who proclaimed their loyalty to the German nation were to live in his service. The allure of securing tyrannical power the likes of which had not been seen in centuries had overcome August in recent years, and no longer would he stand idly by as Hugenberg sat in a throne that was rightfully his. The puppet strings had been broken and the pawn had turned against his king.

It was a sunny day in Berlin. As August Wilhelm peered out of the vast window that stood before him, one could be forgiven for forgetting that the Great War was raging just mere kilometers away. For the last few weeks, however, distant explosions could occasionally be heard ringing from the east. And each and every day, the explosions were getting louder. No one in Berlin, not even August and his fellow elites, wanted to admit it, but the Heilsreich was losing the Great War and Joseph Stalin was getting slowly but surely making his way towards Berlin. Soon, the quiet streets of the Athens of the Spree would become a battlefield, as had been the fate of countless other cities before it.

As Kaiser August Wilhelm reached for his half-empty glass of whiskey, a faint “boom” washed through the air. The Red Army had recently crossed the Oder River, and for a second, the fear that the banks of the Spree River would be next crept through August’s mind. Such worries soon faded away, just as they had continuously been doing ever since the war leapt from the pages of newspapers and became a sound echoing from a not-so-distant land. August completed the act of picking up his glass and bringing it to his lips and taking a faint sip, but just after he set down his glass, the hum of airplanes could be heard. Perhaps Dornier bombers returning from the Eastern Front to refuel? Strange that they would have to fly over Berlin to do so. Soon, however, the hum was accompanied by gunshots.

Boom.

A plane had been hit by German defenses. This was not an aircraft of the Heilsreich.

As the hum of the airplanes got closer, German fighters shot into the sky from the west. More gunfire plagued the air. More explosions came with it. Anton swung open the door to August’s quarters and frantically began to speak.

“Your Majesty, I believe it would be best for you to evacuate to the lower levels of the Palace. The Soviets have just-”

BOOM.

The ground rattled and August’s glass fell to the ground, shattering into numerous shards.

BOOM.

The ground rattled again, much more so than before.

A fleet of planes entered the otherwise empty sky in front of August and dots of steel grey rained down from one aircraft.

The dots fell into the cityscape just outside the window.

Several bright lights flashed.

BOOM.

Berlin was consumed in fire as a man-made earthquake continuously shook the Royal Palace.

“...Yes,” the Kaiser responded. “I think an evacuation would be a good idea.”

Welcome to the Battle of Berlin.

-General Erich Ludendorff of the Deutches Heilsreich, circa March 1928.

The Brandenburg Gate prior to the Battle of Berlin, circa February 1928.

“...Your Majesty?”

“What is it Anton?”

“The Fuhrer has called the Palace and would like to-”

“Tell Mr Hugenberg that I am unavailable at the moment.”

“...Of course, your Majesty.”

And with that, Kaiser August Wilhelm was left alone once again.

It was this solitude that the Kaiser had become so accustomed to in recent months, ever since he and the Fuhrer had transitioned from a close friendship to a bitter political rivalry. Their conflicting approaches to the Western Front had infuriated Hugenberg, who had more or less ruled as Germany’s unquestioned autocrat since the Heilungscoup. August Wilhelm’s total war strategy had certainly stalled the Third International’s offensive into the Rhineland, however, thousands of German civilians had died at the hands of the Luftsreitkrafte in the process. For many within the DVP elite, this apparently crossed a line. For Hugenberg, the line was crossed when August Wilhelm had the audacity to turn members of the German high command against him.

Since October, Hugenberg had been scolding the man who was officially his emperor but was in reality, at least within the framework of the German Fatherland Party, his subordinate for stepping out of line. Time and time again, the Fuhrer would call the Royal Palace to belittle the decisions of August Wilhelm, lambasting the Kaiser as “volatile,” “brash,” and “ignorant” more times than he could count. Eventually, August simply started ignoring Hugenberg’s calls when he could, and everytime the Fuhrer did get an audience with his aristocratic counterpart, it was becoming more and more clear to August that Hugenberg was becoming increasingly desperate. The fact of the matter was that the Great War was being lost under Alfred Hugenberg’s watch, and the knives within the Reichstag were beginning to tilt towards the Fuhrer. Someone needed to take the blame for the losses in both the east and the west, and Hugenberg was running out of military officers that he could throw under the bus.

Kaiser August Wilhelm simply fueled the flames of the DVP’s gradual turn on their leader. After all, as the head of state of Germany, August was the one who stood to benefit the most from Hugenberg’s deposition. With his rival out of the way, Germany could return to absolute monarchism yet again (this time, of course, mixed with the ultra-totalitarian chauvinism of fascism), an age that had preceded the days of even Otto von Bismarck. August’s game of political intrigue with Hugenberg was not, however, exclusively motivated by ideological differences. To the Kaiser, this was all personal. Hugenberg had once been more than a mere political ally of August, for he had been a mentor and a close friend. When the then-Prince August Wilhelm found himself at odds with his fellow Hohenzollerns, Hugenberg became the sole man of power in all of Berlin who he could trust.

And now Hugenberg dared to betray that sacred trust? Dared to betray the will of his Kaiser?

Such treason simply would not stand. Alfred Hugenberg may have committed himself to the supremacy of the Fatherland, but as the German Emperor, August Wilhelm was the Fatherland. By the grace of God, all who proclaimed their loyalty to the German nation were to live in his service. The allure of securing tyrannical power the likes of which had not been seen in centuries had overcome August in recent years, and no longer would he stand idly by as Hugenberg sat in a throne that was rightfully his. The puppet strings had been broken and the pawn had turned against his king.

It was a sunny day in Berlin. As August Wilhelm peered out of the vast window that stood before him, one could be forgiven for forgetting that the Great War was raging just mere kilometers away. For the last few weeks, however, distant explosions could occasionally be heard ringing from the east. And each and every day, the explosions were getting louder. No one in Berlin, not even August and his fellow elites, wanted to admit it, but the Heilsreich was losing the Great War and Joseph Stalin was getting slowly but surely making his way towards Berlin. Soon, the quiet streets of the Athens of the Spree would become a battlefield, as had been the fate of countless other cities before it.

As Kaiser August Wilhelm reached for his half-empty glass of whiskey, a faint “boom” washed through the air. The Red Army had recently crossed the Oder River, and for a second, the fear that the banks of the Spree River would be next crept through August’s mind. Such worries soon faded away, just as they had continuously been doing ever since the war leapt from the pages of newspapers and became a sound echoing from a not-so-distant land. August completed the act of picking up his glass and bringing it to his lips and taking a faint sip, but just after he set down his glass, the hum of airplanes could be heard. Perhaps Dornier bombers returning from the Eastern Front to refuel? Strange that they would have to fly over Berlin to do so. Soon, however, the hum was accompanied by gunshots.

Boom.

A plane had been hit by German defenses. This was not an aircraft of the Heilsreich.

As the hum of the airplanes got closer, German fighters shot into the sky from the west. More gunfire plagued the air. More explosions came with it. Anton swung open the door to August’s quarters and frantically began to speak.

“Your Majesty, I believe it would be best for you to evacuate to the lower levels of the Palace. The Soviets have just-”

BOOM.

The ground rattled and August’s glass fell to the ground, shattering into numerous shards.

BOOM.

The ground rattled again, much more so than before.

A fleet of planes entered the otherwise empty sky in front of August and dots of steel grey rained down from one aircraft.

The dots fell into the cityscape just outside the window.

Several bright lights flashed.

BOOM.

Berlin was consumed in fire as a man-made earthquake continuously shook the Royal Palace.

“...Yes,” the Kaiser responded. “I think an evacuation would be a good idea.”

Welcome to the Battle of Berlin.

I'm quite confident it will be worth the weight, if all of Phase Two can be wrapped up.

Interesting to see how the relationship between the Fuhrer and the Kaiser has developped over the past years, Methinks August Wilhelm is a bit late with getting rid of Hugenberg though It seems pretty obvious the Reich is doomed, so I am curious what plots you have in mind that will make this "self-coup" matter in the long run.

I also wonder, just how much damage have the fascists done to German society with their ruthless purges, by the time Germany falls?

Interesting to see how the relationship between the Fuhrer and the Kaiser has developped over the past years, Methinks August Wilhelm is a bit late with getting rid of Hugenberg though It seems pretty obvious the Reich is doomed, so I am curious what plots you have in mind that will make this "self-coup" matter in the long run.

I also wonder, just how much damage have the fascists done to German society with their ruthless purges, by the time Germany falls?

I'm not entirely sure the Europeans will ever be able to be able to dominate the world again with the two decades long perpetual warfare changing their demographics, I think the Arabs probably have the greatest potential given the fighting on their side has been a skirmish by comparison.

Still the war is over when it's over, as long as leaders are wiling to keep up the last child soldier it won't end and given the rules of wars have been decaying all the time, I suspect the losers will unleash whatever WMDs they have out of spite.

Still the war is over when it's over, as long as leaders are wiling to keep up the last child soldier it won't end and given the rules of wars have been decaying all the time, I suspect the losers will unleash whatever WMDs they have out of spite.

Chapter Eleven: Defend or Die - Part One

Chapter XI: Defend or Die - Part One

“It is here in Berlin that the fate of our empire will be determined. It is here that we will defend the city or die in the attempt.”

-General Erich Ludendorff of the Deutches Heilsreich, circa March 1928.

The Brandenburg Gate prior to the Battle of Berlin, circa February 1928.

“...Your Majesty?”

“What is it Anton?”

“The Fuhrer has called the Palace and would like to-”

“Tell Mr Hugenberg that I am unavailable at the moment.”

“...Of course, your Majesty.”

And with that, Kaiser August Wilhelm was left alone once again.

It was this solitude that the Kaiser had become so accustomed to in recent months, ever since he and the Fuhrer had transitioned from a close friendship to a bitter political rivalry. Their conflicting approaches to the Western Front had infuriated Hugenberg, who had more or less ruled as Germany’s unquestioned autocrat since the Heilungscoup. August Wilhelm’s total war strategy had certainly stalled the Third International’s offensive into the Rhineland, however, thousands of German civilians had died at the hands of the Luftsreitkrafte in the process. For many within the DVP elite, this apparently crossed a line. For Hugenberg, the line was crossed when August Wilhelm had the audacity to turn members of the German high command against him.

Since October, Hugenberg had been scolding the man who was officially his emperor but was in reality, at least within the framework of the German Fatherland Party, his subordinate for stepping out of line. Time and time again, the Fuhrer would call the Royal Palace to belittle the decisions of August Wilhelm, lambasting the Kaiser as “volatile,” “brash,” and “ignorant” more times than he could count. Eventually, August simply started ignoring Hugenberg’s calls when he could, and everytime the Fuhrer did get an audience with his aristocratic counterpart, it was becoming more and more clear to August that Hugenberg was becoming increasingly desperate. The fact of the matter was that the Great War was being lost under Alfred Hugenberg’s watch, and the knives within the Reichstag were beginning to tilt towards the Fuhrer. Someone needed to take the blame for the losses in both the east and the west, and Hugenberg was running out of military officers that he could throw under the bus.

Kaiser August Wilhelm simply fueled the flames of the DVP’s gradual turn on their leader. After all, as the head of state of Germany, August was the one who stood to benefit the most from Hugenberg’s deposition. With his rival out of the way, Germany could return to absolute monarchism yet again (this time, of course, mixed with the ultra-totalitarian chauvinism of fascism), an age that had preceded the days of even Otto von Bismarck. August’s game of political intrigue with Hugenberg was not, however, exclusively motivated by ideological differences. To the Kaiser, this was all personal. Hugenberg had once been more than a mere political ally of August, for he had been a mentor and a close friend. When the then-Prince August Wilhelm found himself at odds with his fellow Hohenzollerns, Hugenberg became the sole man of power in all of Berlin who he could trust.

And now Hugenberg dared to betray that sacred trust? Dared to betray the will of his Kaiser?

Such treason simply would not stand. Alfred Hugenberg may have committed himself to the supremacy of the Fatherland, but as the German Emperor, August Wilhelm was the Fatherland. By the grace of God, all who proclaimed their loyalty to the German nation were to live in his service. The allure of securing tyrannical power the likes of which had not been seen in centuries had overcome August in recent years, and no longer would he stand idly by as Hugenberg sat in a throne that was rightfully his. The puppet strings had been broken and the pawn had turned against his king.

It was a sunny day in Berlin. As August Wilhelm peered out of the vast window that stood before him, one could be forgiven for forgetting that the Great War was raging just mere kilometers away. For the last few weeks, however, distant explosions could occasionally be heard ringing from the east. And each and every day, the explosions were getting louder. No one in Berlin, not even August and his fellow elites, wanted to admit it, but the Heilsreich was losing the Great War and Joseph Stalin was getting slowly but surely making his way towards Berlin. Soon, the quiet streets of the Athens of the Spree would become a battlefield, as had been the fate of countless other cities before it.

As Kaiser August Wilhelm reached for his half-empty glass of whiskey, a faint “boom” washed through the air. The Red Army had recently crossed the Oder River, and for a second, the fear that the banks of the Spree River would be next crept through August’s mind. Such worries soon faded away, just as they had continuously been doing ever since the war leapt from the pages of newspapers and became a sound echoing from a not-so-distant land. August completed the act of picking up his glass and bringing it to his lips and taking a faint sip, but just after he set down his glass, the hum of airplanes could be heard. Perhaps Dornier bombers returning from the Eastern Front to refuel? Strange that they would have to fly over Berlin to do so. Soon, however, the hum was accompanied by gunshots.

Boom.

A plane had been hit by German defenses. This was not an aircraft of the Heilsreich.

As the hum of the airplanes got closer, German fighters shot into the sky from the west. More gunfire plagued the air. More explosions came with it. Anton swung open the door to August’s quarters and frantically began to speak.

“Your Majesty, I believe it would be best for you to evacuate to the lower levels of the Palace. The Soviets have just-”

BOOM.

The ground rattled and August’s glass fell to the ground, shattering into numerous shards.

BOOM.

The ground rattled again, much more so than before.

A fleet of planes entered the otherwise empty sky in front of August and dots of steel grey rained down from one aircraft.

The dots fell into the cityscape just outside the window.

Several bright lights flashed.

BOOM.

Berlin was consumed in fire as a man-made earthquake continuously shook the Royal Palace.

“...Yes,” the Kaiser responded. “I think an evacuation would be a good idea.”

Welcome to the Battle of Berlin.

Varchavianka

“Forward, Warsaw!

To the bloody fight,

Sacred and righteous!

March, march, Warsaw!”

-Refrain of Varchavianka.

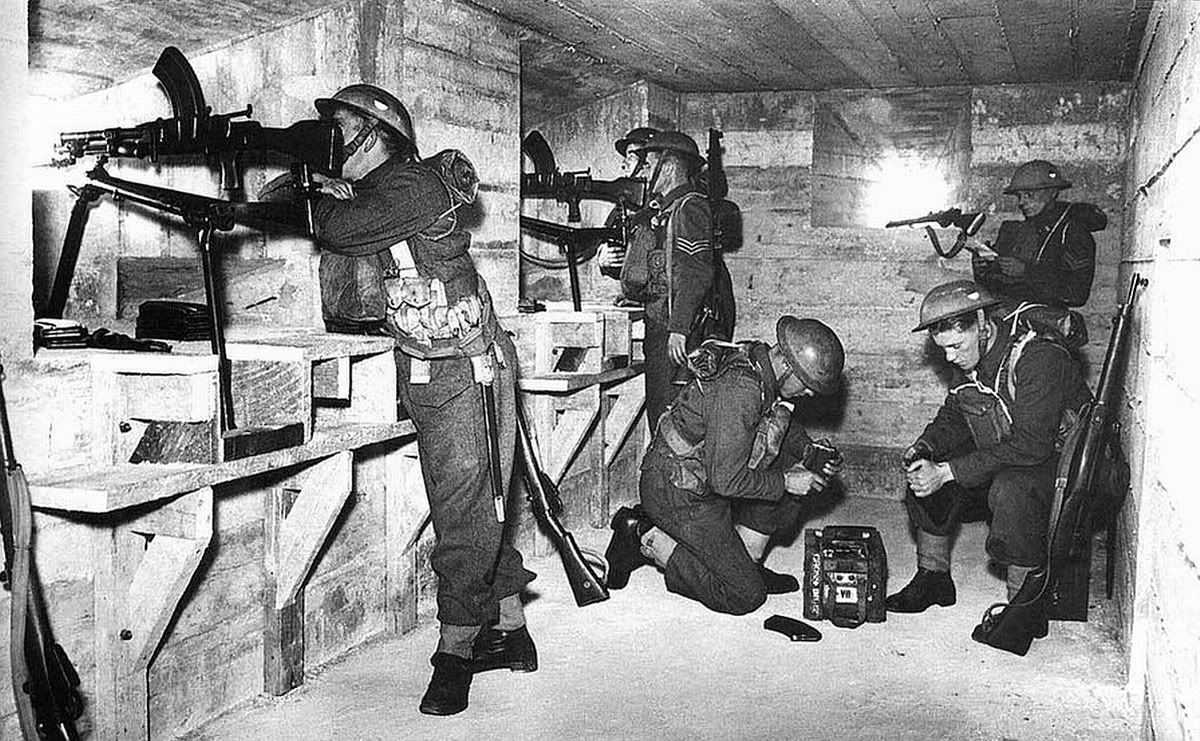

Red Army soldiers fighting on the Eastern Front of the Great War, circa January 1928.

Out of all military officers in the Great War, perhaps General Joseph Stalin was the happiest upon the start of 1928. The previous year had been a slew of victories on the Eastern Front for the Russian Soviet Republic, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had finally succumbed to its internal instabilities, and the Third International had emerged victorious in Asia, which in turn meant that the already mobilized armies of India, Indochina, and Madras were to be deployed in Europe. Generals and politicians alike of the socialist world optimistically anticipated that the Great War would conclude by the end of the new year and a Europe bathed in the crimson of radical socialism would emerge from the rubble. The war wagering on Wall Street had arrived at the same conclusion, as had many officials within the Heilsreich, even if state-run media in the fascist world obviously didn’t make these fears of defeat public information.

Stalin’s push towards Berlin was far from pleasant, however, it was clear that Operation Poniatowski was going according to plan. Mikhail Frunze, a veteran of the Soviet war against the Ukranian State, led the invasion of Pomerania, where the defeat of Germany was more or less a foregone conclusion by this point. German naval forces in the Baltic Sea were directed to supply ground troops in Pomerania, but the aid provided was far from enough to save the region from the fate of numerous other territories in eastern Europe. A vast legion of Russian soldiers and tanks charged towards the coastal city Kolberg as a target for where the Baltics would be cut off from German supply lines, and through the utilization of foudreguerre not even the relentless bombing campaigns of the LK could turn back General Frunze. The Battle of Kolberg would occur on February 1st, 1928, starting with the Red Army sieging the outermost reaches of the city with a slew of gunfire as the sun rose over a cold Europe, and ended by noon with a decisive victory for the Russians.

With Germany proper now severed from East Prussia and its Baltic puppet states, the Russian Soviet Republic made preparations for the next stage of Operation Poniatowski. The Red Fleet was directed to extend its blockade of the Baltics down to the recently-captured Kolberg, which was quickly transformed into one of the Soviet Republic’s most pivotal naval bases. The time had come to starve the Baltics into submission, and surely enough, the collapse of Germany’s naval supply lines would slowly crush Estonia, Lithuania, and the United Baltic Duchy without any gun actually being fired into their territory. German naval forces still managed to occasionally break through the Russian blockade and distribute resources to holdouts in eastern Pomerania, however, the Soviet encirclement of the Baltics was tightened more and more every single day while General Frunze’s forces turned east following their victory at Kolberg to wipe out Germany’s remaining presence in the Baltic Sea.

All the while, the Red Napoleon directed Soviet aerial forces to begin a bombing campaign of Baltic territories, with aircraft deployed from both land and sea obliterating what remained of Germany’s prizes from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Total war had effectively become routine in Europe by this point, so no one batted an eye when firebombing was deployed to obliterated Baltic cities. Konigsberg, which had been heavily fortified ever since the days of Kaiser Wilhelm I, was especially targeted by Soviet air campaigns. As a predominant target of Mikhail Frunze, Konigsberg was amongst the first major Baltic cities to fall into the hands of the Russian Soviet Republic, but this did not save it from the hellfire of the Soviet Air Force. Day and night, firebombing would decimate the last major concentration of German military forces in the Baltics. All the while, the Red Fleet cut off the substantial pocket of soldiers in East Prussia and General Frunze defeated units deployed in Pomerania. On February 14th, 1928, General Erich Ludendorff finally recognized that the forces defending East Prussia would soon be needed west of the Oder River, not to mention that the Soviet firebombing campaigns had made sure that there wasn’t much of an East Prussia to continue to defending anyway, and thus ordered an immediate withdrawal of German forces from the region.

German soldiers fleeing Konigsberg, circa February 1928.

Only two days later, Soviet soldiers arriving from Danzig reached the southern reaches of Konigsberg, therefore beginning the battle for the city. The evacuation of Konigsberg was far from complete at this point, and thousands of German soldiers were trapped in the city when Russian forces began to engage with the city's defenses. Demoralized and lacking sufficient supplies, there was no way that the forces of the Heilsreich would emerge victorious at the Battle of Konigsberg. As units were directed to fight in the southern reaches of the city, other units were evacuated to ships stationed in the Frisches Haff Bay. The Battle of Konigsberg was far from a cakewalk for the Red Army, however, the conflict was still won within the span of a day, and by the end of February 16th, the city was decisively in Soviet hands. The last great German holdout along the Baltic Sea had fallen.

While Mikhail Frunze led his campaign through Pomerania and East Prussia, other Soviet officers pushed into the Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and the United Baltic Duchy. All three nations had been spared during the rest of Phase Two due to Operation Ascania miscalculating a rapid victory that would force the Central Powers to sue for peace before war would have to be waged in the Baltics. This immediate end to the Great War in 1923, of course, never came to be and the Russo-Baltic border had been transformed into a line of fortifications, obstacles, and weapon installations to ensure that the Germans wouldn’t dare to use their puppet states in northeastern as the launching point for an offensive into Russia. In 1928, the time had finally come to bring the Baltic states to their knees, an affair that would take only a few weeks due to bombing campaigns and the Red Fleet’s blockade already having devastated the fledgling puppet states.

The Kingdom of Lithuania was the first of the Baltic states to fall, as it was the only nation in the region to have lost substantial territory in the Great War at this point due to its southernmost reaches standing in the way of Russia’s push into Poland. Without any military aid from the German Heilsreich to keep it afloat following the Battle of Konigsberg, Lithuania went out with a whimper after years of combat against the Russian Soviet Republic. The Battle of Vilnius would result in a decisive victory for the Red Army on February 21st, 1928, thus bringing the Lithuanian capital city under the control of the Soviets. Despite Berlin demanding that Lithuania continue fighting in the Great War, King Friedrich Christian I called for a ceasefire two days after the fall of Vilnius and offered peace negotiations with the Russians on the condition that he and his family would be able to flee into exile. Premier Trotsky agreed to the defeated king’s offer, and on February 27th, 1928, the Treaty of Grodno was signed, which annexed Lithuania into the Russian Soviet Republic as the Lithuanian Autonomous Soviet Republic.

The Principality of Estonia was the next state to fall. A small coastal nation, the only thing that kept Estonia afloat for more than mere days was the collection of fortresses and obstacles constructed along the nation’s border with the Russian Soviet Republic to slow down any invasion. A year prior, and Russian offensive into Estonia would have likely been stalled long enough for the Germans to arrive, thus igniting yet another war of attrition between the two titans of eastern Europe. But the situation on the Eastern Front had, of course, now changed and Estonia was left to die a painful death. The capture of the nation’s capital of Tallinn on February 28th, 1928 marked the ultimate defeat of the Principality of Estonia, and the small monarchy completely fell under the military occupation of the Red Army.

The United Baltic Duchy was a far larger nation than Estonia and had not been forced to fight for years on its own homefront like Lithuania, and thus held out for the longest. Duke Adolf Friedrich of the UBD anxiously resided in Riga, knowing that he would soon be forced to flee into exile. By the time of the Battle of Tallinn, the bulk of the Duchy had already fallen into Soviet hands (the village of Rauna had been lost to the Red Army on the same day as Tallinn), and only the cities of the coastline remained in the hands of Adolf Friedrich. With the entirety of the RSR’s Baltic forces now concentrated on the UBD, it would take less than a week for the flag of the Soviet Republic to be hoisted over Riga, for the battle for the city already decimated by firebombing occurred on March 5th, 1928, and obviously ended with the Red Army finally defeating the United Baltic Duchy and forcing Duke Adolf Friedrich to run away into exile.

As the dust of the Baltic Offensive settled, Premier Leon Trotsky arrived in the ruined city of Jurmala to sign a peace treaty that would reorganize Estonia and the United Baltic Duchy into territories of the Russian Soviet Republic. Rather than become autonomous regions like Lithuania, however, Trotsk viewed decisive Soviet control over the coastal regions of the occupied countries to be vital for Russian naval interests in the Baltic Sea, thus meaning that the Treaty of Jurmala imposed direct rule from Moscow over the lands of Estonia and the UBD. In the aftermath of the Baltic Offensive, Trotsky would initiate a number of infrastructure development projects throughout the recently-annexed lands in order to not only rebuild the region from a brutal war but to turn the Baltics into a useful asset for the Soviet war effort. The reconstruction of destroyed harbors was prioritized, while new shipyards and factories sprouted up around these bases of Russian naval power. The Baltics had returned to Russia, and the Red Napoleon was keen on ensuring that his undoing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk would be well worth the effort.

On March 12th, 1928, General Joseph Stalin initiated the Battle of Frankfurt an der Oder, and had captured the segment of the city to the east of the Oder River by the end of the day. At long last, the Red Army had reached the banks of the Oder River and thus stood at the gateway into the heart of Germany. As ground forces clashed day after day for control over the entirety of Frankfurt, the Luftsreitkrafte and the Soviet Air Force endlessly fought in the sky above. As the battle continued, however, it became increasingly apparent that Stalin’s forces were poised to emerge victorious. The expeditionary forces of South Asia had long since arrived on the Eastern Front and the Third International army engaged at Frankfurt was therefore one of largest ever seen in the Great War up to that point. The Oder River served as a barrier to stall the Soviets, but sooner or later this barrier would be broken and General Stalin made his way into western Frankfurt on March 16th. Two days later, the German Heilsreich had been completely pushed out of Frankfurt an der Oder, and the Red Army stood poised to make its way to Berlin.

Two Red Army soldiers following the Battle of Frankfurt an der Oder, circa March 1928.

With the Red Army across the Oder River, Berlin was just a few kilometers away. Russian airplanes would break through German aerial defenses on March 20th, 1928 and drop the first bombs upon a city that would soon be drenched in bloodshed the likes of which had yet to be seen in the Great War. Three days later, Joseph Stalin would link up with Indian Expeditionary Force troops led by Jawaharlal Nehru at the Battle of Steinhofel, and as aerial combat over Berlin became more frequent, Alfred Hugenberg and Kaiser August Wilhelm I were evacuated to Hanover. The seemingly endless legions of German forces that Stalin and Nehru faced more and more of the closer and closer they got to Berlin were unprecedented in the Great War, however, Third International officers were already gathering in tents at night to develop their plan of attack on the German capital.

On March 25th, Erich Ludendorff was defeated at the Battle of Furstenwalde after two days of house-to-house combat. A day later, Ludendorff was forced to flee westwards yet again when he lost the Battle of Rauen. By this point, the streets of Berlin, many of which were already filled with the rubble of air raids, were eerily quiet and it was becoming increasingly apparent that the German government had no plan to evacuate the city’s civilians despite the looming battle. On March 28th, the Third International won the Battle of Spreenhagen and Premier Leon Trotsky arrived in Frankfurt an der Oder to closely monitor the coming conflict. On March 29th, General Jawaharlal Nehru emerged victorious at the Battle of Friedersdorf. Unbeknownst to the Third International, on the very same day reports were privately brought to Kaiser August Wilhelm’s attention that some members of the fuhrer’s cabinet were, at least according to rumors circulating amongst the DVP elite, discussing potential terms of surrender.

Finally, on March 31st, 1928, the time had come for the Battle of Berlin to truly begin. In accordance with the plans drafted by Joseph Stalin days prior, the bulk of the Red Army was to make a grand offensive towards Kopenick while Jawaharlal Nehru would lead the Indian Union’s expeditionary force to southern Berlin. From here, both Stalin and Nehru would launch a joint foudreguerre offensive into Berlin from the east and south, and if everything went according to plan, the Great War was anticipated to be over in a matter of weeks. The nightmare that had engulfed the world for the past fourteen years could finally come to an end, and the fascist terror would be condemned to the dustbin of history. Early into the morning of March 31st, Leon Trotsky gave General Joseph Stalin the go-ahead to engage with German forces defending Berlin after alerting allied governments in London, Lumiere, Calcutta and Saigon of the coming battle, and soon enough hundreds of tanks were unleashed to flank the German capital city from its eastern and southern borders.

By noon, Stalin had occupied Kopenick with relative ease as forces under the command of Erich Ludendorff retreated across the Dahme River. General Nehru managed to cross the Dahme around the same time but was bogged down by reinforcements led by Lieutenant General Friedrich Paulus at Eichwalde, where the All-Indian Liberation Army would hold out through the night. The first day of the Battle of Berlin came to an end with good results for the Third International. General Stalin had secured the foothold in eastern Berlin that he had desired, and while Nehru had yet to step foot into the city of Berlin itself, it had been anticipated that such an goal would take longer for the southern flank to achieve anyway. Nonetheless, the Heilsreich remained determined to win the battle for its capital city, and LK forces were directed to heavily bomb Third International positions stationed within and outside of Berlin. Just after the midnight of March 31st, the first of the firebombing campaigns on General Stalin’s forces began, and due to anti-aircraft guns being limited in Kopenick due to such equipment still being delivered from Spreenhagen, casualties were heavy. By the time the sun began to rise over Europe in the morning, reinforcements had arrived with more anti-aircraft weapons to deter the Luftsreitkrafte, but the damage had already been done. Nonetheless, Stalin simply had to lick his wounds and linger on.

German bomber flying above eastern Berlin, circa April 1st, 1928.

The next few days of the Battle of Berlin were mostly stagnant. Seeing that the conflict for the city would not end anytime soon, both sides scrambled to rush reinforcements into Berlin, with the Third International consolidating its control over its supply lines in eastern Germany while the Heilsreich transferred troops from other frontlines. Stalin continued to attempt to push across the Lange Brucke bridge to enter Grunau, however, Ludendorff eventually concluded that Kopenick wasn’t returning to German hands anytime soon, which made Lange Brucke a liability, and thus ordered the destruction of the bridge on April 2nd. Nehru seemed to be having better luck than Stalin throughout early April, and slowly but surely pushed Paulus out of Eichwalde. On April 7th, German forces had been completely uprooted from Eichwalde and General Nehru stepped foot into Berlin itself for the first time. Meanwhile, a joint army of AILA, FII, and Madras forces under the command of Indian General Ram Prasad Bismil initiated a westward push to the south of Berlin, with the intent of reaching Potsdam and cutting Berlin off from southern reinforcements.

The advances of Nehru from the south were slow, however, they did gradually diminish Ludendorff’s manpower fighting against both Nehru himself and Stalin. Nonetheless, German defenses showed no sign of crumbling anytime soon, and the Battle of Berlin soon became a war of attrition. Days turned into weeks, and gaining control over a mere street became a grand accomplishment. Urban terrain meant that the Third International could not conduct the foudreguerre tactics that had won it so much territory in such a short amount of time in order to win over Berlin, and close quarters combat left even the most feared tanks at the Red Army’s disposal vulnerable to infantry attacks.

The land surrounding Berlin, which had more open spaces and was also focused on less by German officers anyway, was a different story. General Bismil’s army covered swathes of land with relative ease on his way to Potsdam, conquering Dahlewitz on April 22nd, whereas the Battle of Berlin had more or less remained stagnant during the past few weeks. These campaigns to the south forced Erich Ludendorff to dilute soldiers to fight Bismil, thus reducing the total German military presence in Berlin and weakening the defenses of the city. This led Joseph Stalin to conclude that a similar offensive to the north of Berlin would make things easier for the campaigns of himself and Nehru, therefore resulting in the development of Operation Mehmed to accomplish just that. The officer put in command of the army that would conduct Operation Mehmed was none other than Mikhail Frunze, who had long since arrived at the Battle of Berlin following the success of his campaign in Pomerania and East Prussia.

On April 26th, Operation Mehmed would begin when General Frunze successfully invaded Woltersdorf, thus giving him a launching point for his conquest of the territory to the north of Berlin. Schoeneiche would be the next city to fall and landed into the hands of the Red Army on May 1st. Realizing that Stalin was attempting to pull off flanking his men from both the north and south, Erich Ludendorff ordered Hermann Erhardt to launch a counter-offensive against Frunze, something that clearly stalled Operation Mehmed. Nonetheless, Mikhail Frunze continuously made progress in the face of Erhardt, who was given substantially less men to command than he had hoped for due to Ludendorff directing the bulk of forces in the Battle of Berlin to continue fighting against Stalin and Nehru. On May 11th, Neuenhagen fell in the north while Stahnsdorf simultaneously fell in the south. The effects of Bismil’s southern offensive were already starting to be felt on German forces in Berlin, who were facing the arrival of less and less reinforcements and fresh supplies every single day.

Determined to cut off one of the two flanks of Berlin, General Ludendorff finally gave into Erhardt’s requests for more soldiers in the north and placed hundreds of men under his command with the hope that Operation Mehmed could be brought to a swift end. This decision proved to be a crucial mistake on Ludendorff’s part, for defenses against Joseph Stalin were diminished in order to attack Mikhail Frunze. On May 17th, Stalin’s forces exploited an opening in Ludendorff’s defenses left by a diminished troop presence and slowly made their way across the Dahme River. Reinforcements would arrive by the afternoon to stall the Soviet offensive, however, these reinforcements were taken from Friedrich Paulus’ defenses in southern Berlin, which meant that Nehru was soon able to make advances of his own, and soon enough, Ludendorff’s position directly to the west of Kopenick was being flanked from both the south and east. Fighting over the Dahme River would carry out over the night, but as the sun began to rise on the subsequent day, the first Russian boots were beginning to step foot into Grunau, and hours later, as the Red Army was securing its position to the west of the Dahme, they were accompanied by Nehru’s AILA arriving from the south. Erich Ludendorff was forced to order a retreat to Johannisthal as the flag of the Russian Soviet Republic was raised over the position he had held for almost two months.

Of course, this retreat by the Germans could not last forever, and by the end of May 18th, the war of attrition for Berlin had resumed. Nonetheless, had concluded that the Battle of Berlin was not going to be won by the Heilsreich anytime soon unless substantial reinforcements arrived and the German strategy was altered. On May 20th, Alfred Hugenberg, August Wilhelm, Benito Mussolini, Oskar Potiorek, and Ivan Valkov arrived in Venice to discuss the allocation of aid from Central Power member states to Germany in order to win the Battle of Berlin. Prime Minister Valkov, who was not fighting on any of Bulgaria’s borders ever since Greece had been defeated, committed the most manpower and resources to the Eastern Front, followed by Mussolini, who was still concerned with the war in southeastern France and had already deployed substantial Italian expeditionary forces in the war over the Balkans and Austria but nonetheless was not currently facing an invasion by either the Entente or Third International, not to mention that Mussolini recognized that Italy could not hold out for long if Germany were to fall and the entire arsenal of both the Entente and Third International alike was concentrated on Rome.

Oskar Potiorek, whose Kingdom of Illyria was currently facing an invasion by the Federation of Transleithanian Council Republics, was less willing to provide aid to the Heilsreich. Despite this, pressure from the leadership of the Central Powers made sure that Potiorek sent some equipment to the Battle of Berlin, however, Illyria was notably the only member of the Central Powers to not deploy soldiers in the Battle of Berlin. After the Venice Conference, it would take a few days for reinforcements from the Central Powers to arrive in Berlin, and in the meantime Erich Ludendorff simply had to ensure that the city would not begin to rapidly fall into the hands of Third International forces. Mikhail Frunze’s offensive against Hermann Erhardt began to move in favor of the Russians yet again during this time period, with Honower Siedlung falling on May 23rd. Ludendorff continued to request the allocation of more aircraft to the skies of Berlin, however, even this advantage managed to be deterred by the Third International, which had installed anti-aircraft guns all throughout occupied Berlin.

Red Army soldiers manning an anti-aircraft gun during the Battle of Berlin, circa May 1928.

Bismil’s southern campaign, which had previously been the most successful front of the Battle of Berlin, was a different story. In late May 1928, Brigadier General Erwin Rommel arrived from the Eastern Front to partake in the defense of Potsdam from the Indian Expeditionary Force. A man who admired the potential of armored infantry, General Rommel would seek to defend Potsdam by mounting a stand at Babelsberg, where LT tanks were to face off against the German Heilsreich’s most advanced tanks, the most notable of which was the A7V-U4, which was a medium tank that had built upon the technology of prior A7V-U models and captured British tanks. The Battle of Babelsberg would occur on May 26th at the outskirts of its namesake city, where the more open space was preferential for tank combat, and after hours of combat, General Ram Prasad Bismil was forced to retreat for the first time in the conquest of Berlin due to Rommel’s tank defenses (something the Germans were not known for and therefore something that the Third International was prepared to combat) repelling Bismil’s advance towards Potsdam.

An A7V-U4 model tank stationed outside of Babelsberg, circa May 1928.

Shortly after the Battle of Babelsberg, the first reinforcements from the Central Powers began to arrive in Berlin. The Italian and Bulgarian expeditionary forces were dispersed throughout all frontlines of the battle, however, the bulk were deployed to defend against Stalin and Nehru’s joint offensive. These reinforcements managed to stop the Third International’s westward offensive, however, for the time being, the tides of the Battle of Berlin had yet to turn in favor of the Central Powers and a war of attrition emerged at Baumschulenweg circa early June 1928. The continued influx of soldiers from Italy and Bulgaria would also manage to hold back Mikhail Frunze’s offensive in the north by bringing the clash between the Red Army and Heinrich Erhardt to a standstill at Ahrensfelde on June 12th. In the south, where Erwin Rommel already seemed to be gaining the upper hand following his victory at Babelsberg, the arrival of the Italians and Bulgarians proved to be decisive in actually regaining ground from the Third International. The banner of the Heilsreich was hoisted above Guterfelde on June 9th, and over Ruhlsdorf a little over a week later on June 18th.

Eventually, however, Rommel would also be bogged down at Kleinbeeren on June 25th, and throughout the subsequent July the Battle of Berlin was more or less a stalemate on all fronts. Troops from the Central Powers and Third International alike continuously flowed into the German capital city, which became infamous throughout the world for its brutal and relentless combat. One American journalist visiting Soviet-occupied Berlin in mid-July 1928 would declare that the city had become “the Graveyard of All Eurasia” and made note of the fact that the Battle of Berlin was already by far the single bloodiest engagement in the entirety of the Great War. Whatever residents of Berlin either hadn’t fled the city or hadn’t been killed in the crossfire between the great powers found their lifestyles annihilated by the bombs of war, just as the lifestyles of millions before them had been destroyed throughout the world over the last fourteen years. Even in the parts of Berlin many kilometers away from the frontlines of the Great War, entire blocks had been replaced with piles of rubble and bombing campaigns had become so consistent that most parts of the city had simply given up on sounding air raid sirens.

Simply put, whoever was to win the Battle of Berlin would inherit smoldering ruins.

In early August, an increasingly desperate General Erich Ludendorff met with Hermann Goring to draft up plans for an air raid that the two men hoped would turn the tides of the Battle of Berlin in favor of the Deutches Heilsreich. Determined to emerge victorious, Ludendorff proposed that the Luftsreitkrafte would deploy countless bombs containing mustard gas over parts of Berlin held by the Third International in order to literally choke enemy forces out of the city. Civilians would inevitably suffer in the process, however, such cruelty was nothing fascists such as Ludendorff and Goring were unfamiliar with. Therefore, on August 8th, Red Army and AILA forces in eastern Berlin fell victim to a slew of mustard gas bombs raining from above, and soon enough the air of Berlin was filled with a poisonous yellow-brown mist, leaving many Third International soldiers incapacitated as German soldiers bearing gas masks made their way into enemy-occupied territory. In the fog of toxins, General Ludendorff retook Johannisthal, however, by this point the Third International’s forces had distributed gas masks throughout its ranks and the German Imperial Army was stopped between Johannisthal and Aldershof by the end of the day.

German “poisonbombing” continued well past August 8th and soon became a mainstay of the Battle of Berlin. It also opened Pandora’s Box by giving the Third International reason to utilize its own chemical weapons upon German positions, with both the Red Army and Soviet Air Force being directed by Joseph Stalin to launch mustard gas at the enemy. By the end of August 1928, the Athens of the Spree had become a city of poison. Civilians cowered in basements as the war above turned the air that swept through their homes into a lethal toxin while the boldest personalities of the Great War clashed on the surface, their faces hidden behind the ghastly gas masks that had been synonymous with the War to End All Wars for years.

In the nightmare that was the Battle of Berlin there was, however, a sliver of hope, at least amongst those fighting for the Third International. There was hope that, after all this time, all of this sacrifice, all of this bloodshed, all of this horror, the man-made hell would finally cease. There was hope that it would take only one last push for the Deutsches Heilsreich to surrender and for the Great War to come to an end. While those supportive of the Central Powers and the Entente hoped that the conflict would continue so that a decisive victory for their faction could emerge, the rest of the world, regardless of its allegiance to the ideals of socialism, was exhausted of the last fourteen years of endless industrialized warfare and simply wanted the endless barrage of suffering to end. Humanity was scarred by what was already the bloodiest war in its history, and while it would take decades to heal these wounds, a victory for the Third International was the key to a recovery within the coming years.

The question, therefore, was if the Heilsreich could snatch this key away.

Invading the Silent Continent

“The Great War Comes to Africa”

-New York Times headline, circa October 1928.

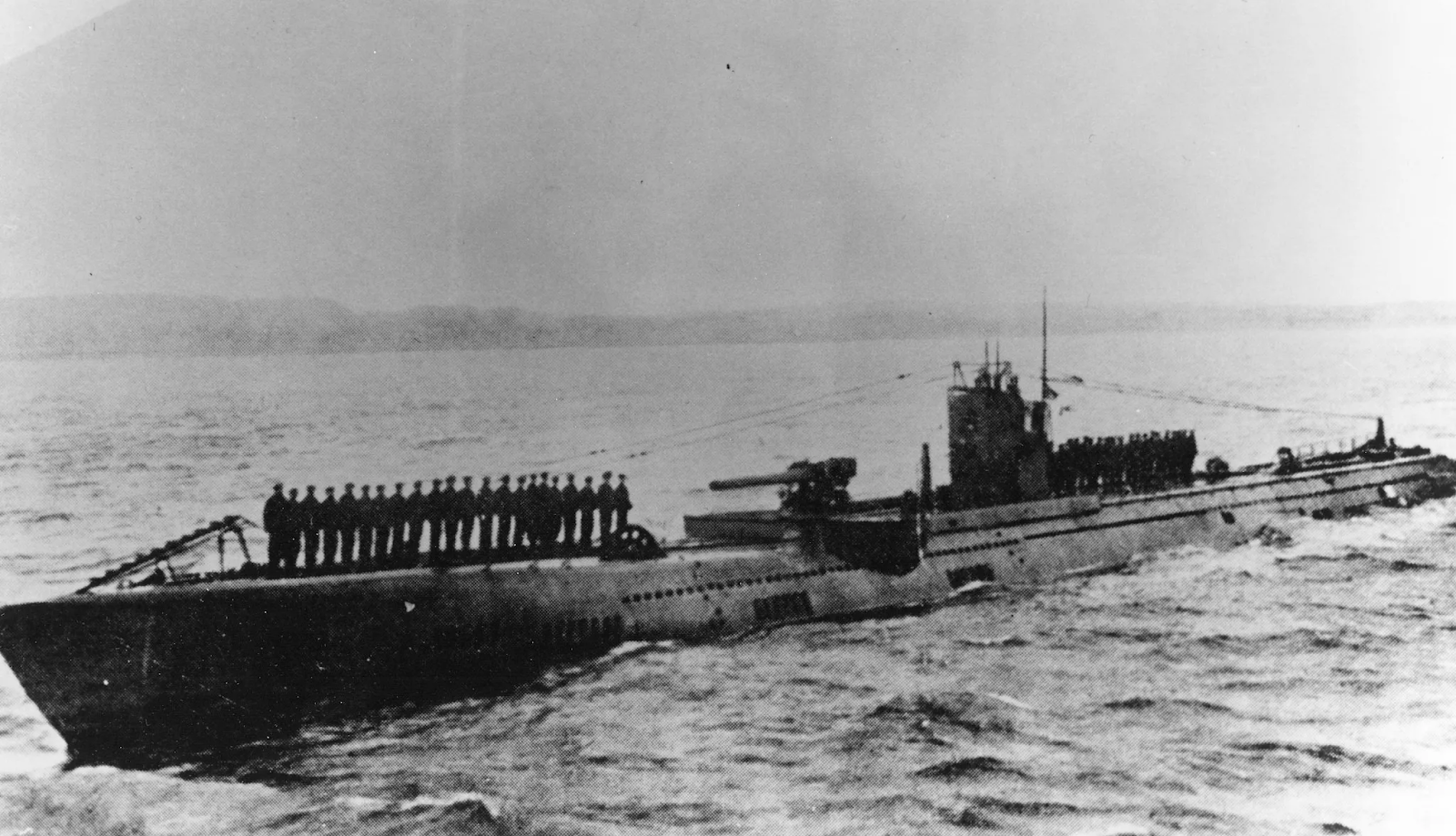

Warships of the French Fourth Republic during an engagement with Communard naval forces on the Mediterranean Sea, circa August 1928.

As the Russian Soviet Republic concentrated its war effort on the Battle of Berlin, the French Commune and its allies in western Europe remained engaged in a war that spanned multiple frontlines. To the east, the Central Powers fought on in the trenches as a coalition of the Third International forces poured into the Rhineland while airplanes bearing revolutionary symbols bombed Italian positions in southeastern France. To the south and west, the British, French, and Irish all faced the threat of the work over the past few years of breaking the chains of capitalism being undone via a naval invasion by the Entente. The House of Windsor continued to keenly watch the affairs of the Atlantic Front from Ottawa while the French Fourth Republic continued to hold the colonial empire constructed over the past century together, all under the jackboot of Ferdinand Foch.

At the center of all of these wars tied together by alliances and common enemies was the French Commune. Perhaps no nation was more scarred by the Great War than France, which had been engulfed in the flames of combat since the very beginning. Such gruesome and constant warfare had certainly taken its toll on France, with approximately 12.9% of the French population having perished in the Great War by the start of 1928. Combined with soldiers and civilians that had evacuated for the French Fourth Republic during the Communard victory in the nation’s civil war, metropolitan France’s population plummeted from 39.6 million in 1914 to 33 million in 1928. Out of France’s remaining population, only 8 million people were qualified for conscription by the time of the Battle of Berlin, and the majority were already fighting on behalf of the LGPF. Nonetheless, by little more than sheer luck, metropolitan France had evaded conquest by the Germans over the past fourteen years despite coming very close to the Kaiser’s men parading through Paris (and later Lumiere) on multiple occasions. Under the rule of the Commune, a combination of expanding conscription eligibility, banning emigration, the mechanization of infantry, and the deployment of forces from other Third International member states onto the Western Front, the French war machine just barely kept on churning.

As the first Russian bombs began to fall on Berlin, the main focus of the French Commune was the continued offensive into the Rhineland. The Burning of the Rhine had been a devastating blow for the Third International, but the tables of the Western Front were far from having been turned back in favor of the Central Powers. General Commander Boris Sourvarine simply continued his northward push, albeit at a much slower and more cautious pace as anti-aircraft guns were shipped en masse to the Rhineland while Albert Inkpin ordered the Workers’ Democratic Air Force to dramatically increase its presence on the European continent. Once the Battle of Berlin was in full swing, German defenses on the Western Front were weakened by their own government’s redistribution of manpower and equipment to the east, with the simple fact of the matter being that the defense of Berlin was far more tactically significant than the defense of the Rhineland.

Therefore, Third International soldiers on the ground slowly scaled along the Rhine River as their comrades clashed with German bombers in the sky. After Cologne fell on February 27th, 1928, the Third International pushed towards Grevenbroich, which was captured by the French on March 24th, thus making it the last German city to be conquered on the Western Front prior to the start of the Battle of Berlin. As the forces of Stalin and Nehru consumed the Heilsreich’s attention, officers in the west took advantage of the noticeable decline in German forces fighting for the Rhineland. The German presence in the west was large enough throughout April 1928 to keep the French, British, and Irish offensive at bay (bombing runs continued to exert a heavy toll on the Third International’s supply lines), however, there was nonetheless an accelerated fluidity in the frontlines of the Western Front in favor of the Third International during the first month of the Battle of Berlin. It should also be noted that the Indian Union and Madras both dispatched expeditionary forces on the Western Front circa mid-April 1928, which was crucial for adding new manpower in the west, not to mention that the arrival of said manpower resulted in a much-needed morale boost amongst the embittered British and French veterans of the Great War.

The Battle of Grevenbroich on April 17th resulted in a decisive French victory, leaving only the northernmost reaches of the Rhineland to be captured. Less than two weeks later, Mikahil Frunze’s offensive into the area north of Berlin was in full swing and Erich Ludendorff scrambled to reorganize German troop concentration, both amongst the forces already fighting in Berlin and on all frontlines of the Great War. Regiments fighting on the Western Front were called out east, which paved the way to a relatively quick Third International victory at the Battle of Viersen on May 7th. Eleven days later, Joseph Stalin stepped foot on the western banks of the Dahme River and Ludendorff reallocated the German presence on the Western Front to Berlin yet again. By this point, the once-fearsome German war machine that had terrorized western Europe for over a decade was on its last legs, and even the Burning of the Rhine had ceased in favor of a much more limited aerial bombing campaign in order to ensure that there were enough airplanes to wage constant total war over Berlin.

It was, therefore, not a surprise when the Rhenish Offensive concluded in early June 1928 with a decisive victory for the Third International. With only the northernmost reaches of the Rhineland left untouched by General Souvarine’s campaign following the Battle of Viersen, a foudreguerre offensive led by Armure Is would make quick work of what remained of Walther von Brauchitsch’s defenses of the region. The half of Dusseldorf to the west of the Rhine fell on May 20th, followed by the fall of Krefeld on May 24th, the fall of Moers on May 26th, and the fall of Xanten on June 2nd. The German Army made its final stand of the Rhenish Offensive at the Battle of Kalkar, which began on June 7th as LGPF tanks attacked the outskirts of the city. After three days of combat, the Germans were ultimately uprooted from the city and General Brauchitsch subsequently ordered a retreat of remaining German forces from the Rhineland in order to set up defenses on the eastern shoreline of the Rhine River.

The Third International’s decisive victory in the Rhenish Offensive was a shocking blow to the Heilsreich, however, for the time being, the forces of the revolution in the west would fail to progress any further east. Recognizing that the high command of the German government simply did not view the Western Front as their top priority while the Battle of Berlin was ongoing, Walther von Brauchitsch decided that his strategy could not depend on an influx of reinforcements going forward and instead opted to rapidly set up a collection of makeshift obstacles and fortifications along the Rhine in an attempt to deter any potential eastward offensive by the French Commune and her allies. This array of defenses was designed with the intent of preventing a foudreguerre offensive into central Germany, hence why obstacles intended to make tank movement extremely difficult and anti-tank guns were amongst the first installations put in place by General Brauchitsch. By the beginning of July 1928, what became known as the Brauchitsch Line had already proven its capability of stalling further Third International incursions into Germany, and as the Russians struggled to make their way through the ruins of Berlin in the east, the French found themselves stuck in yet another war of attrition in the west.

As the summer of 1928 dragged by, the Brauchitsch Line became more and more secure, thus resulting in a more or less completely stagnant Western Front for several months. The belligerent forces continued to deploy manpower and equipment along both sides of the Rhine, but the fact of the matter is that no progress was being made. But to the south of the Rhineland and the European mainland itself, General Commander Boris Souvarine was in reach of grasping another prize, one that was arguably even more valuable than the defeat of Germany, at least in the eyes of the French Commune. It was upon the waters of the western Mediterranean Sea where this prize began to appear on the horizon, for it was here that the navy of the French Fourth Republic was beginning to lose to its growing Communard counterpart. By the beginning of 1928, the French Navy was already clearly overshadowed by the socialist Navy of the French Proletariat (MPF). By the fall of the same year, the increasingly exposed Algerian was rife with vulnerabilities that could be exploited in the name of the Second French Revolution.

The time had finally come for the civil war that had engulfed the French people for over seven years to reach its end.

Still present on the Western Front for the time being, Souvarine began drafting plans for a naval operation to land in North Africa in late August 1928, eventually producing what would become known as Operation Delescluze. Under this plan, Algerian ports would be bombed by air raids in order to weaken Republican defenses prior to twin amphibious landings at Bougie in the east and Cherchell in the west, which would surround the Republican capital of Algiers. From that point, the LGPF was to conduct a campaign that would gradually bring the entirety of the French North African coastline under the control of the Communards and force the Fourth Republic to flee into the Sahara Desert, presumably never to see the waters of the Mediterranean ever again. After spending the latter half of September 1928 amassing naval and aerial forces for the French Commune to utilize in the coming conflict (many of which were forces from South Asia), General Commander Souvarine gave the go ahead to his subordinates to begin Operation Delescluze.

The campaign for North Africa began on October 9th, 1928 when a deluge of bombs rained down upon Algerian cities and naval defenses. A lack of domestic industry developed within France’s colonies had ultimately come back to haunt the imperialist rulers of the French Fourth Republic when their defenses of the Algerian coastline primarily consisted of weapons either evacuated from Europe years prior or exported from allies in the Entente, especially Brazil. Given its strategic importance, Field Marshal Philippe Petain concentrated French ground troops in Algiers with the expectation that the amphibious offensive that would follow the French Commune’s air raids would surely target the aforementioned city. Of course, Petain’s prediction proved to be wrong, and on October 13th LGPF forces simultaneously landed in both Bougie and Chernell, experiencing relatively little resistance due to Petain’s focus on Algiers. By the end of the day, Operation Delescluze had achieved the securing of two Communard beachheads in North Africa and Boris Souvarine stepped foot in Chernell, determined to end the civil war that he had presided over since it had begun all those years ago.

The tides of revolution had washed upon the shore of Africa.

LGPF soldiers landing in North Africa during the Battle of Bougie, circa October 1928.

Despite the best attempts of Philippe Petain to hold back the oncoming Communard onslaught, it was now only a matter of time until the LGPF would be marching through Algiers. The fact of the matter is that the Republicans were outnumbered, outgunned, and unprepared to fight one of the most mechanized armed forces in the Great War on their home turf. The arrival of Armure I model tanks on the North African Front occurred almost immediately after the landings at Chernell and Bougie, which meant that the French Commune would be able to employ foudreguerre, a tactic that the Fourth Republic had no experience with nor equipment to effectively counter against. It therefore goes without saying that the remainder of Operation Delescluze was a quick and decisive victory for the LGPF. Tipaza fell on October 16th, Azeffoun fell on October 18th, and Dellys fell on October 19th.

All the while, the Kingdom of Italy, which was engaged in combat against both the French Commune and the French Fourth Republic, launched an offensive into French Tunisia, which became increasingly poorly defended during Operation Delescluze. Italian soldiers would scale towards Tunis from colonial holdings in Libya while the Regia Marina would shell the Tunisian coastline from the sea. On October 21st, Italian forces secured a beach head at Kelibia and subsequently made an eastward push towards Tunis, and entered the outskirts of the city on October 26th. After no more than two days of fighting, the Battle of Tunis ended in a victory for the Kingdom of Italy and the government of the French protectorate had surrendered to the forces of Benito Mussolini. The Treaty of Bizerte was ratified four days later, and in an act of purely nationalistic fervor that was intended to harken back to the ancient days of Rome conquering Carthage, the French protectorate of Tunisia was annexed directly into the Kingdom of Italy, being afforded not even the limited degree of autonomy conceded to colonial regimes in Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia.

On October 20th, 1928 the Battle of Algiers would begin as General Commander Boris Souvarine started to siege the capital city from the west and the increasingly frail President Ferdinand Foch was evacuated to Dakar in anticipation of Petain’s inevitable defeat. Petain and his men put up a vicious fight, however, the fact of the matter was that the Republicans were in an unwinnable situation. By noontime on October 21st, Souvarine’s forces in the west had reached Baba Hassen while LGPF forces pushing from Bougie began their assault on Algiers from the east. A little over twenty-four hours later, Communard forces in both the east and west met up in the heart of Algiers, thus forcing Philippe Petain to the southern reaches of the city. Recognizing that he had lost the Battle of Algiers, Field Marshal Petain ordered a general retreat of the French Army from the battlefields of northern Algeria and fled into the Sahara Desert.

Operation Delescluze had succeeded, Boris Souvarine had won yet another decisive victory for the French Commune, and the former capital of the French Fourth Republic had finally been painted red. In order to celebrate this momentous victory for the Communard cause, the Central Revolutionary Congress went as far as to rename Algiers to Hilmi, in honor of the Turkish socialist journalist Huseyin Hilmi, in early November 1928. Of course, the North African Front was not over. The French Commune rapidly developed a line of defenses in eastern Algeria to deter any Italian offensive launched from Tunisia, however, this particular frontline was not a priority for either Lumiere or Rome. Boris Souvarine instead peered into the Sahara Desert, determined to make his way across the vast ocean of sand and finally vanquish the French Fourth Republic. Given that there were very few major settlements within the Sahara, the focus of the North African Front now shifted to securing control of regional supply lines.

Republican regiments therefore were scattered at points of importance throughout the seemingly endless sand dunes while Communard tanks were sent into the heart of the largest desert on Earth with the intent to hunt down these aforementioned regiments. Among the tanks deployed by the French Commune were the recently-developed Armure IIs, the successor to the less powerful but nonetheless prominent Armure I model tank, which had been a staple of French foudreguerre tactics for years. The Saharan Offensive was the first engagement that Armure IIs were deployed in, and they soon proved to be the deadliest light tank in the Communard arsenal, and the Sahara Desert proved to be an ideal location to wage foudreguerre due to its empty terrain making armored infantry incredibly effective. By the end of November 1928, El Golea had fallen into Communard hands. On January 4th, 1929, the new year was ushered in with Boris Souvarine emerging victorious at the Battle of In Salah, which put the French Commune in control of an oasis town vital to trans-Saharan commerce.

An LGPF convoy outside of In Salah, circa January 1929.

At this point, one would think that things couldn’t possibly get any worse for the French Fourth Republic. Petain’s forces were losing decisively in the Sahara, the bulk of Algeria had already fallen in a matter of months, and the Republicans had no hope of amassing either the manpower or equipment necessary to turn the tides. But, as the Great War had already proven time and time again, things can always get worse. Just beneath the surface of the Fourth Republic, internal instability was building up after over a decade of dormancy with regards to local revolts thanks to the Treaty of Bloemfontein. Now that French colonies were the frontline of the war between the Communards and the Republicans, Bloemfontein had effectively become null and void and as colonial governments diverted their attention to the North African Front, the tension between natives and imperialist regimes was about to reach a boiling point.

The African Spring was about to begin.

Springtime

“If there is one thing to be learned from the Great War, it is that no empire is immortal.”

-Winston Churchill, circa 1930.

African soldiers of the French Army, circa 1928.

The Great War killed the old empires of Europe. The exiled French and British imperialist regimes fought on throughout all of Phase Two, but in hindsight, the opportunity to restore the Victorian world order was lost when the flames of revolution engulfed Paris and London. The fact of the matter was that European colonialism had always been a tenuous house of cards whose foundation was dependent on the consistently effective suppression of local revolts. The Treaty of Bloemfontein, which had secured the neutrality for African colonies during the great War, had kept this foundation stable for a few years by allowing for colonial governments to concentrate their efforts on maintaining their grip on power, however, this foundation was shaken when the House of Windsor and French Republic were both forced into exile, with the latter ultimately setting up its base of operations in Africa. The Fourth Republic nonetheless maintained the Treaty of Bloemfontein (it should, however, be noted that said treaty still allowed for resources produced in African colonies to be used in the war effort), but as the French Commune gradually approached the coastline of North Africa, it was only a matter of time until previously neutral colonial possessions became a frontline of the Great War and the treaty that had narrowly guaranteed the survival of empires for so long would fail.

The foundation of France’s once-mighty colonial empire would finally be destroyed when, under blatant pressure from President Ferdinand Foch, the governments of French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa signed the Treaty of Dakar on March 6th, 1929, which stated that the two colonial federations would declare war on the French Commune and commit to conscripting men to fight on the North Afircan Front, including indigenous men. While Foch’s hope was that the additional manpower would allow for a quick retaliation against Boris Souvarine in the Sahara Desert, thus resulting in a Republican reconquest of Algeria or, at the very least, forcing the Communards to sue for a peace agreement that was favorable to the Fourth Republic, the ultimate consequence of the Treaty of Dakar would be the beginning of the end for the Entente war effort. This brings us to Kaocen Ag Geda, a Tuareg chief who resided in the northern reaches of the West African colony of Niger and was a member of the Senussi, a militant anti-colonial Muslim religious order that had fought against European incursions into the Sahara Desert for almost a century. Kaocen had participated in attacks on French forces since 1909, however, these clashes never escalated into a full-out revolt and the Treaty of Bloemfontein had made sure that French West Africa had enough manpower at its disposal to keep Kaocen down throughout the Great War.