Chapter Sixteen: A Twist of Fate

Chapter XVI: A Twist of Fate

“Poland shall be the knife which your righteous empire will thrust into the heart of the Marxist savages.”

-Excerpt from a letter written by General Erich Ludendorff to Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm, circa April 1930.

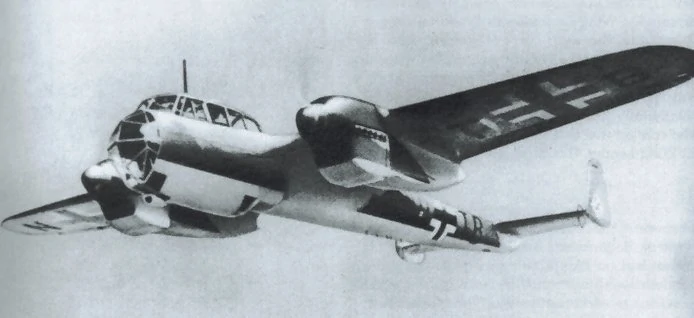

Dornier Do 13 light bomber flying over Poland, circa April 1930.

On April 12th, 1930, the tides of the Great War had shifted yet again when German forces won a decisive breakthrough against Red Army defense in Swiecko. The war of attrition along the banks of the Oder River that had more or less been the status quo along the Eastern Front since the aftermath of the Battle of Berlin was broken within the span of mere hours, forcing General Stalin in retreat as the rival General Ludendorff followed in pursuit. The Eastern Front was once again fluid, and for the first time in years, it was flowing in favor of the Central Powers. The springtime offensives into central Poland and Pomerania were, however, brief in their success. By the end of May 1930, the Red Army had reinforced its position along the Eastern Front, in large part thanks to reinforcements from the Indian Union, halting further German advances at the Battle of Schneidemuhl. Ludendorff had indeed made progress, and Stalin remained on the defensive, but the quick overrunning of Poland that August Wilhelm and his military’s high command had so desperately desired remained out of reach, at least for the time being.

Nonetheless, going into the summer of 1930, the relentless campaign of total war waged over Polish skies continued. Soviet aerial defenses prevented the Luftstreitkrafte from penetrating too far behind enemy lines, but for those unfortunate enough to live in the western reaches of the country, close to enemy lines, German air raids drenched the landscape in a vile mixture of bombs and poisonous chemicals. Under the philosophy of total war, there was frighteningly little discrimination between civilian and military infrastructure, and as such, thousands of civilians remaining in western Poland, an area already devastated by prior military campaigns jostling for the territory as a corridor between Germany and Russia over the past two decades, perished at the hands of the Heilsreich, whose leadership cared little for human life. After all, under the reign of national absolutism, mankind’s role was that of an asset of the German nation and her physical manifestation in the form of the Kaiser-Fuhrer. If this duty could not be fulfilled, death was viewed as acceptable.

To this end, as the summer of 1930 approached, August Wilhelm began to investigate new tactics to utilize against the Third International. Having already embraced scorched earth tactics, the Kaiser-Fuhrer took an interest in effectively starving off Soviet frontlines by waging a poisonbombing campaign that would target deploying mustard gas on agricultural lands in order to poison soil and decimate crop production. Nearly sixteen years of chemical warfare had already had a devastating impact on European agriculture, with millions of civilians across the continent perishing from famine related to the Great War by the beginning of Phase Three and entire villages annihilated as chemicals seeping into the ground made them incapable of supporting human habitation, let alone farming. Yet these “zones mortes” (dead zones), as the government of the French Commune deemed them, were not intentional weapons in and of themselves, rather a vile scar carved into the earth itself by well over a decade of industrialized warfare. As such, they tended to develop along the frontlines of wars of attrition, with ribbons of zones mortes being particularly infamous throughout northern and eastern France. Conversely, Poland, which had often been rapidly exchanged between the German and Russian war machines, had actually been spared many of the conditions that produced significant zones mortes.

The herbicidal warfare employed by the Heilsreich starting in June 1930 was different. For the first time in human history, a large scale chemical weapon operation would directly and overwhelmingly target farmland with the explicit intent to poison crops and the soil they were dependent upon in order to eliminate a critical source of food for western Poland and the Third International military forces fighting in the region depending on local agricultural production to keep their troops well-fed. This meant that the quantity of mustard gas deployed on Polish fields was far greater and more precisely concentrated than in previous campaigns, with long-term ecological collapse now being a goal of the Heilsreich’s military campaign rather than an unintended side effect. Indeed, the herbicidal warfare waged against farmland to the west of Warsaw had a permanent effect on the local environment, so thoroughly infecting the land with mustard gas that significant agricultural production in the region was guaranteed to be an impossibility for decades to come, and many areas became large zones mortes, with Germany’s herbicidal warfare contributing to desertification in Poland that would persist well beyond the conclusion of the Great War. In effect, the Kaiser-Fuhrer viewed the environment of Poland itself to be a weapon in the war against the Heilsreich, and he in turn deemed the annihilation of this environment in favor of an eastern European desert to be a necessary retaliation.

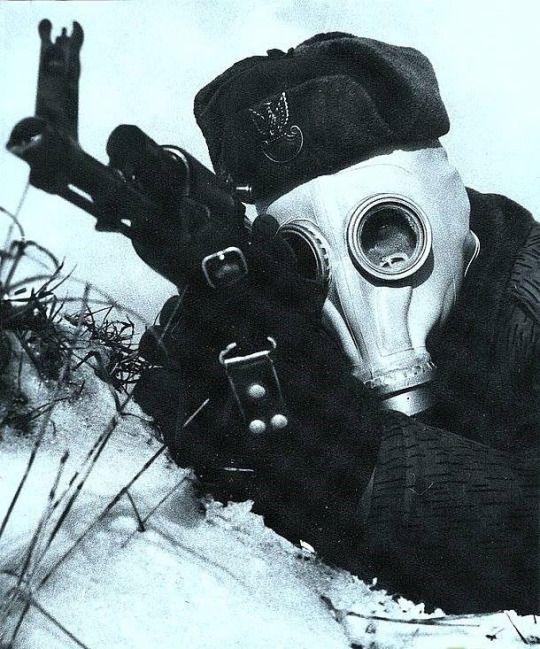

German soldiers charging through a cloud of mustard gas on the Eastern Front, circa July 1930.

The herbicidal warfare campaign waged against Poland starting in June 1930 was brutal, slow, and deeply cruel, however, this did not matter to August Wilhelm, at this point a man so deeply entrenched in the madness of national absolutism, did not care. In his eyes, all that mattered was decisive victory for his empire in the Great War, no matter the cost. In this sense, herbicidal warfare was a clear success. The tactic had caused widespread crop failure throughout western Poland by July 1930, and the unorthodox nature of the campaign caused farmland, barely defended given its perceived lack of tactical significance from the perspective of the Third International, to be an easy target for German bombers. Mass famine ravaged not Poland but much of the neighboring Soviet sphere of influence more generally, given the fact that Poland was a primarily agricultural economy that had exported products to its allies throughout much of Phase Two. And, of course, this food insecurity extended to Third International forces on the Eastern Front as well, causing both starvation and demoralization to creep into its ranks. Ironically, just as scorched earth policies had denied Napoleon’s forces needed crops in the campaign against the Russian Empire, so too were the Red Napoleon’s forces now denied needed crops through scorched earth tactics in their offensive extending out from the Russian Soviet Republic.

While far from turning the tides of the Great War in any meaningful war, the Yellow Famine of 1930 (named as such due to the yellow-ish color of mustard gas) was credited for chipping away at Red Army defenses, and throughout July and August 1930, the Heilsreich did make notable territorial gains. Third International supply lines were spread thin, and the Heilsreich took advantage of this situation to punch through overextended defenses at multiple points. General Rommel spearheaded the eastward campaign as Erich Ludendorff continued to chip away in Pomerania, intending to reach the de jure German-Polish border along the Warta river by October 1930, however, these estimates would ultimately prove to be conservative. As the fall harvest season began in September 1930, the true effects of the herbicidal war waged against Poland began to take hold. Widespread starvation, weakening supply lines, and declining morale amongst Soviet troops combined with Rommel’s utilization of armored infantry against Soviet LT tanks resulted in a far greater collapse of Third International defenses than anticipated circa early September 1930.

As such, after making gradual advances throughout July and August, the Warta Offensive rapidly accelerated after Erwin Rommel’s victory at the Battle of Festenberg circa September 2nd. A7V-U4 model tanks formed the blade of the German knife piercing into the Red Army, and after a series of impressive victories, the German Army laid siege to Sieradz, already the victim of months of relentless aerial bombings and poisoning alike, starting on September 17th, 1930. Sieradz had been fortified as Joseph Stalin’s last stand before retreating across the Warta to the east of the city, although at this point, it was undeniable that the Heilsreich’s capture of the city was seemingly inevitable. That being said, even if the Red Army’s control of Sieradz was living on borrowed time, the battle was a unique challenge for Rommel, who had been accustomed throughout the Warta Offensive to leading hasty charges through the countryside, an environment that favored his enthusiastic utilization of tanks. Attacking a relatively large and well-defended city like Sieradz was a far different beast, and while General Rommel quickly encircled the city (with the notable exception of its northeast, which bordered the banks of the Warta) upon the first day of combat, actually getting into the city itself had to wait for September 18th, at which point messy close-quarters combat ensued, a form of warfare that Rommel was certainly familiar with after the Battle of Berlin but was most certainly not his strong suit.

Nonetheless, after days of brutal combat with high casualties mounting on both sides, General Rommel finally expelled Joseph Stalin from Sieradz on September 20th, thus reaching the Warta river and concluding its namesake offensive. A poisoned landscape laid both behind and in front of him, products of the cruel war machine of German national absolutism that he loyally served. Entire villages had been wiped off the map due to the 1930 poisonbombing of Poland, and Rommel’s forces celebrated their victory at the Battle of Sieradz in a region that would become enveloped by a man-made desert by the conclusion of the Great War. In the meantime, however, German forces amassed themselves along the Warta river, biding their time for the moment when they’d have the capacity to launch another offensive, this time into the territory of the Republic of Poland itself, while Stalin frantically tried to recover from his losses while maintaining extensive defenses along the Warta in order to barricade the heart of Poland from the servants of fascism.

To the north, Erich Ludendorff likewise saw success going into the fall of 1930 in large part due to the Yellow Famine. Having reoriented his campaign away from pushing towards the well-defended Polish northwest, General Ludendorff sought to take advantage of Third International supply lines focusing on defending the Polish state by waging a campaign to recapture Soviet-occupied Pomerania, hoping that doing so would both boost morale amongst Germans by reclaiming the entirety of occupied territory in the east and serve as a means to assert the dominance of the Heilsreich in the Baltic Sea by capturing key port cities. Of particular focus, at least in the short term, were Gdnyia and Danzig, which the German high command came to regard as the gateways to the recapture of East Prussia. While Rommel was well-armed with tanks, technology that was still not particularly emphasized in German tactics amongst other generals, especially veteran officers of Phase One, such as Ludendorff, the Danzig Offensive was nonetheless more well-armed and received greater manpower than the Warta Offensive, with the expulsion of the Red Army from all German territory being seen as a greater priority than the conquest of Poland.

Despite being regarded as an integral component of German territory and Danzig in particular being a predominantly German-speaking city, the Heilsreich had little problem with waging total war in the Danzig Offensive, and poisonbombing campaigns of herbicidal warfare extended as far north as Pomerania. Under the reign of the Kaiser-Fuhrer, any notion that being considered a subject of the German nation exempted one from being treated as expendable by the national absolutist war machine had long since been abandoned, even if such bombing campaigns turned many ethnic Germans in Soviet-occupied territory away from supporting the Heilsreich’s war effort, with hundreds of young Germans behind enemy lines enlisting in volunteer forces on behalf of the Third International by the conclusion of 1930. In the eyes of the Heilsreich’s leadership, however, this was irrelevant. At this point, the infusion of almost two decades of relentless warfare with the ultranationalist anti-individualism of fascism had given way to an obsession with total victory in the Great War, by any means necessary. The ramifications of such a victory could be dealt with later, when the Kaiser-Fuhrer’s hegemony over Europe had been established.

Much like in the Warta Offensive, progress against the Third International by General Ludendorff was slow but steady throughout July and August 1930, followed by a sudden collapse of Red Army defenses circa September 1930 once the harvest season approached and the ramifications of the Yellow Famine became most harshly felt. Additionally, the Danzig Offensive benefited from focusing on the capture of coastal cities, which meant that the Imperial German Navy, now the largest naval force in Europe following the disintegration of the British Empire during Phase Two, could flex its muscles against the Red Navy and aid in Ludendorff’s victory on the ground. Russian naval defenses along the Pomeranian coast were gradually penetrated by the warships and aerial bombing campaigns of the Heilsreich upon the waves of the Baltic Sea, a domain where the mighty fleet of tanks of the Red Army could not save the Soviet forces. By early September, a series of quick naval victories had resulted in the Imperial German Navy being observable from the docks of Gdynia and Danzig, well before any German troops had arrived.

Nonetheless, the German Army was not far behind. On September 12th, 1930, Ludendorff’s men captured the village of Rewa, thus bringing the final coastal settlement to the north of Gdynia under German military occupation and leaving the Red Navy without any ports in the area. Only a day later, the Imperial German Navy entered the Bay of Puck, encircling several evacuating Soviet ships in the bay’s namesake battle and leaving Gdynia incapable of receiving any new reinforcements by sea. With the city effectively surrounded, General Ludendorff led his men in an offensive from Rewa on the morning of September 14th, while forces under the command of General Hermann Erhardt attacked Gdynia from the small village of Zbychowo to the west. All the while, LK bombers flew overhead, dominating the skies, while German naval vessels released a torrent of artillery fire from the Bay of Puck. By the afternoon, Ludendorff and Erhardt had linked up near the city’s port and made their final push into the southern half of the city, expelling the remaining Soviet forces in Gdynia within mere hours.

Erich Ludendorff spent little time celebrating his victory at the Battle of Gdynia. The greater prize, Danzig, laid just mere kilometers to the southeast, and Ludendorff was eager to continue his momentum, ordering German forces to continue their campaign along the Pomeranian coast before the crack of dawn on September 15th, less than twenty-four hours after German control over Gdynia had been consolidated. Sopot was captured before noon, and from there, the full onslaught of the German armed forces descended upon Danzig. Much like in Gdynia, the Battle of Danzig effectively consisted of four separate engagements. From the north, Ludendorff scaled down along the coast, while Erhardt was ordered to loop around from the west, moving through Oliwa and piercing the soft underbelly of the city. Meanwhile, the Imperial German Navy was to besiege the city from the sea, gradually decimating remaining Soviet naval forces trapped in Danzig’s shipyards, while the Luftstreitkrafte was to relentlessly bombard Danzig with fire and poison alike from above.

At around noon circa September 15th, 1930, the first of Ludendorff’s forces broke through Soviet defenses, beginning the Battle of Danzig. Red Army units under the command of General Yakov Sverdlov managed to put up a good fight, holding out for hours in a futile attempt to hold onto Danzig, but the barrage of destruction raining down upon them from all directions was ultimately too much to bear. While Ludendorff and Erhardt encroached upon the city from the north and west, eventually fighting street by street, the Imperial German Navy decimated whatever Soviet naval defenses remained, and, seeing an opening with the destruction of said defenses, General Ludendorff ordered a makeshift amphibious landing on the undefended northern coastline Danzig upon receiving word of this victory at sea. German warships hastily transported troops in reserve stationed in captured villages in the Bay of Puck, with an amphibious assault securing the Westerplatte peninsula with ease a little more than an hour before midnight. By the dawn of September 16th, all of Danzig to the north of the Dead Vistula had been captured.

German warships patrolling the waters by the Westerplatte peninsula during the Battle of Danzig, circa September 1930.

With General Sverdlov now facing ground invasions from three directions and casualties rapidly mounting, he saw little chance at holding onto the southern districts of Danzig, and as the sun rose over the city on September 16th, Sverdlov regretfully ordered a retreat of what remained of his army from Danzig, regrouping on its outskirts in order to hold back Ludendorff’s onslaught. In the meantime, General Erich Ludendorff claimed his prize, the ruins of Danzig, having won his battle for the city and now securing critical ports from which German naval efforts could be projected throughout the Baltic Sea, albeit with some repairs from the destruction inflicted during the Battle of Danzig being necessary. In the coming days, General Ludendorff advanced to the east of Danzig, progressing steadily against General Sverdlov. The Battle of Swibno circa September 22nd, 1930 expelled Third International forces across the Vistula River, thus bringing all German territory to the west of the river under the control of the Heilsreich and resulting in a decisive victory for Ludendorff in the Danzig Offensive.

For the time being, the Vistula River stood as a barrier against further German incursions on the Eastern Front. But Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm and his lapdogs in the German armed forces were, of course, not satisfied with this victory. East Prussia, the homeland for the Kingdom of Prussia that had unified and brought August’s family to the throne of Germany, remained under Russian occupation, and from both a perspective of tactics and pride, it was a far greater prize than Gdynia and Danzig. Indeed, with the conclusion of the Danzig Offensive, the reconquest of Prussia became the new priority of the German high command. This shift in German priorities became blatant to the world when, on October 1st, 1930, Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm made an address to the Reichstag, broadcasted throughout all of the Heilsreich, in which he declared that foreign forces would be completely expelled from eastern German territories by the conclusion of 1931 and Germany’s territorial integrity in the east would be restored. In other words, all of East Prussia was to be reclaimed within a little more than a year.

The call to reconquer East Prussia was a gambit by the Kaiser-Fuhrer. In the immediate term, it certainly bolstered morale, providing an increasingly war-weary German populace a timetable for when the Heilsreich would be capable to begin offensives into the Russian heartland itself, thus placing the end of the Great War on the horizon. But while momentum was in Germany’s favor on the Eastern Front for the time being, there was no guarantee such momentum would be maintained. Perhaps the German advance would slow, grind to a halt, or even begin to be reversed. And if all of these very plausible developments were to occur and August Wilhelm’s guarantee was unable to come into fruition, there was a very distinct possibility that whatever remaining legitimacy he had with the German people would be undermined beyond repair. While the Kaiser-Fuhrer was confident that the reclamation of the east was on the horizon, the reality more apparent to his military officers was that the Eastern Front had now turned into a race against the clock. The Prussian Offensive had begun, and if it were to succeed, the Heilsreich needed more fuel for its war machine.

The Bear and the Eagle

“...God has ordained the German nation to reign over the Earth, and to accomplish this most righteous and holy ambition, the most essential territorial integrity of the German Heilsreich must be restored. Therefore, in pursuance of fulfilling the word of God, I hereby pledge my armed forces to the noble goal of expelling the barbaric Marxist invaders from the entirety of eastern Germany within the coming year. By 1932, the banner of the Heilsreich shall wave over Konigsberg yet again, and no Russian, Indian, Indochinese, nor Madras soldier shall step foot on German soil!”

-Excerpt from Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm of the German Heilsreich’s “Konigsberg Pledge” address to the Reichstag, circa October 1st, 1930

Polish sniper fighting on the Eastern Front of the Great War, circa November 1930.

As the Kaiser-Fuhrer’s quest for East Prussia commenced in October 1930, the Russian Soviet Republic adapted to changing circumstances. With the conclusion of Phase Two and a slew of German victories forcing the Third International to suddenly go on the defensive, Soviet forces had to change their approach to the Great War as the environment of Europe itself was altered by almost two decades of mechanized warfare. Premier Leon Trotsky, the Red Napoleon, had indeed found his greatest rival in August Wilhelm, whose willingness to abandon both accepted military doctrines and basic morality in the pursuit of total victory had made him an opponent as formidable as he was unpredictable. But Premier Trotsky was no stranger to a good challenge. It was the Red Napoleon, after all, who had won the Russian Civil War for the Bolsheviks, had led the Red Army to victory on the Eastern Front upon the onset of Phase Two, and had navigated his way to authority not even Vladimir Lenin had exerted upon Russia. Surely, August Wilhelm was just one more obstacle to overcome on the road of Permanent Revolution?

The most critical vulnerability for the Russian Soviet Republic to overcome was its poorly-balanced military arsenal. Since 1923, the crux of Soviet military strategy had been its emphasis on tanks. Under the guidance of Trotsky, first as commander of the Soviet armed forces and later as Premier, the Russian Soviet Republic had pursued the mission of developing the largest quantity of and most advanced tanks in the world, believing that a strategy that leaned into the utilization of armored infantry could overrun German troops at a rapid speed while suffering minimal casualties. Indeed, this focus on tanks as the basis for Soviet warfare worked well throughout much of Phase Two. Leon Trotsky had been correct in his prediction that the Central Powers would be incapable of outpacing Russian tank development, and several Red Army victories were ultimately credited to the disproportionate usage of tanks. This armored infantry-centric military doctrine aptly referred to as the “Trotsky Doctrine” in many circles over time, even proved to be useful for western Third International forces, with the French Commune in particular relying on tanks to defend and later wage offensives against the Germans, in large part due to France’s need to compensate for critical manpower shortages. In fact, it was French adherence to the Trotsky Doctrine that ultimately led General Commander Boris Souvarine to develop foudreguerre tactics.

While the Russian Soviet Republic was leading the world in tank design and production, however, the German armed forces of mid-1920s placed a similar emphasis on aircraft development, believing that dominating the sky would give the Heilsreich’s war effort a clear advantage over the forces of both the Third International and the Entente. This ultimately resulted in the Eastern Front becoming a war of rivaling military philosophies as much as it was a war of ideology, with the Russians waging a war on the belief that tanks were the key to victory in 20th Century combat whereas the Germans believed the same for aircraft. This wasn’t to say that neither side invested in the other’s preferred technological field whatsoever, but the disproportionate utilization of tanks and planes by Russia and Germany respectively was obvious to even a lay observer of the Great War, and many battles of Phase Two often grinded down to stalemates because Soviet tanks could only get so far before German bombers decimated the, or because German aerial bombing runs could only get so far before Soviet anti-aerial defenses shot warplanes out of the sky.

Neither the Russian Soviet Republic nor the German Heilsreich really saw the need to change their strategies. In the case of the latter, tanks had never really been the strong suit of the German Army, even back in Phase One, and instead of trying to play catch-up with more sophisticated armored infantry, German high command simply continued to invest in anti-tank defenses and positioning the Luftsreitkrafte as the most powerful airforce in the world. For the Red Army, prioritizing tanks brought them to Berlin. Why would they change horses mid-stream, especially when that horse seemed to be doing its job exceptionally well? But then the Battle of Berlin played out, and, just as it had been a turning point in the Great War for a plethora of reasons, it was a turning point for German attitudes towards tanks. General Rommel’s utilization of A7V-U4 model tanks to repel Soviet incursions proved to be a successful strategy, and after the Red Army was sent running back across the Oder River, Rommel continued to use tanks to fight back against the forces of Joseph Stalin. In summary, under the guidance of Erwin Rommel, the German armed forces began to ever so slightly diversify its technological approaches and was becoming increasingly accustomed to the usage of tanks as a critical component of any mechanized military force.

Rommel’s victory in the Warta Offensive, brought about in large part due to his usage of tanks to spearhead his eastward campaign, was a wakeup call for the Soviet high command. German investment in tanks could easily turn the tides of the Eastern Front by turning the Heilsreich into a jack of all trades, and the 1930 poisonbombing of Poland and the subsequent Yellow Famine it brought about made the horrific ramifications of rendering the sky the domain of the Heilsreich painfully apparent. Therefore, starting in October 1930, Premier Leon Trotsky, in coordination with General Joseph Stalin, began to draft up plans to dramatically increase airplane production, ideally without simultaneously decreasing tank production too dramatically. Indeed, such a shift would also give the Soviet Republic an advantage in the war against the Turkish National State, where the battlefield upon the waves of the Black Sea obviously did not favor armored infantry whatsoever.

Since Leon Trotsky’s rise to power in the Russian Soviet Republic, the policy of War Communism had been the guiding doctrine of the Soviet economic system, with strict centralized ownership and management of industry, harsh disciplining of workers, obligatory labor duty, and the rationing of commodities to be distributed by central authorities describing the aggressively totalitarian structure of the Russian economy, where production, distribution, labor conditions, and who worked was all centrally controlled by the vanguard of the party-state. In effect, labor had essentially been militarized, with people being conscripted into the workforce and strictly following the orders of superior officers appointed from the top down. To make matters more extreme, Premier Trotsky had managed to pass constitutional reforms in 1925 that allowed for the premiership to unilaterally implement policy without consultation from either the Politburo or the upper echelons of the Bolshevik Party, thereby turning Trotsky’s de jure autocratic rule over the Soviet Republic into a de facto role and ceding total control over the Russian economy to the Red Napoleon.

Such an authoritarian system was often criticized by the more libertarian socialist parties of France, Britain, and Ireland, however, their governments, dependent on their alliance with Moscow for survival, didn’t dare follow suit in such condemnations. Even if Trotsky was controversial internationally, he remained deeply popular amongst the Russian people despite exercising the power to conscript them into forced labor, being viewed as a national hero of both the Russian Civil War and Great War whose vanguard was a necessity in order to industrialize the country and save all of Russia, neigh, the socialist world, from total annihilation at the hands of the fascist imperialist onslaught. The Russian Soviet Republic was in a war for national survival, and Leon Trotsky capitalized upon this situation to amass a pervasive cult of personality. His reign was unquestioned by the dawn of Phase Three. Indeed, it was the firm iron fist of Trotsky that guided the Soviet Republic through the Three Year Plan of 1924 to 1927, which oversaw the rapid and brutal industrialization of Russia with the goal of dramatically increasing wartime production, particularly with regards to the development of the Red Army’s armored infantry.

With the German Army marching west under the umbrella of death that was the LK, the time had come for yet another Three Year Plan in 1930. Presented to the Politburo of the Russian Soviet Republic by Premier Trotsky on November 1st, 1930 after a month of development with bureaucrats, Bolshevik Party elites, and military officers, the Second Three Year Plan called for yet another dramatic uptick in Russian industrialization, this time with a focus on conscripting forced labor to produce wartime equipment, particularly aircraft, with the goal of diversifying the Soviet armed forces. Additionally, while the First Three Year Plan had primarily industrialized the western urban centers of Russia, the Second Three Year Plan emphasized industrialization in Central Asia, newly-annexed territories in Ukraine and the Baltics, and the Autonomous Soviet Republics. Therefore, on top of ramping up air force production, the Second Three Year Plan served another, more political, purpose of industrializing the more rural territories of Russia, rebuilding and integrating the economies of regions annexed during Phase Two, and generally promoting a sense of national unity, primarily in areas that were not predominantly ethnically or linguistically Russian.

The Second Three Year Plan went into effect circa December 1930, and within the coming months, factories dedicated to the mass production of warplanes were propped up from Tallinn to Tashkent. Thousands of Soviet citizens, primarily from either pre-industrial rural communities or territories still recovering from the effects of the Great War, were conscripted to work in these new factories as though they were being enlisted to fight soldiers on the floors of industry rather than the battlefields of war. Central to the Second Three Year Plan was Yakov Alksnis, Chief of the Soviet Air Force (VVS), since 1929. A young veteran of the Russian Civil War and notoriously efficient disciplinarian who was known for personally inspecting flying officers and committed himself to attention to detail, Alksnis’ rise to power was the product of both merit and luck. Alksnis was an undeniably competent officer following his graduation from the Red Army Military Academy in 1922 and received a high-ranking position in the Soviet Air Force shortly thereafter, however, his rise to the top was only possible due to the quiet purging of VVS Chief Konstantin Akashev following the ascension of Leon Trotsky to the premiership of the Russian Soviet Republic in 1924 due to Akashev’s historical leanings towards anarcho-communist ideology.

Over the next five years, leadership of the VVS rotated around the Soviet high command, from political allies of Trotsky to more qualified officers with genuine experience in aerial combat. Nonetheless, for the remainder of Phase Two, the Soviet policy of largely ignoring aerial forces in favor of the prioritization of mechanized infantry meant that the Chief of the VVS was a largely underappreciated post, frequently treated as subordinate to the officers of the Red Army. After the Battle of Berlin, however, Leon Trotsky began to see the need for appointing a truly qualified and experienced officer to command the VVS for the long term and opted for none other than Yakov Alksnis, who had already made a name for himself as the leader of a number of secret aircraft design programs and the chief promoter of parachutes for Soviet aircraft.

Chief Yakov Alksnis of the Soviet Air Force.

Only a year later, Alksnis found himself positioned to be a leading advisor to Premier Trotsky regarding the development of the Second Three Year Plan, overseeing planning for the mass production of aircraft and the models of which aircraft specifically were to be built. Nikolai Polikarpov, the leading Soviet aeronautical engineer since the beginning of Russian involvement in Phase Two, spearheaded designs for production in the Second Three Year Plan under the instruction of Alksnis. By December 1930, the Polikarpov I-5 and I-6 models were by far the most common fighter planes within the VVS arsenal, and production on these models indeed increased under the Second Three Year Plan, however, both planes were simply outmatched by German aerial technology, and the Soviets required an upgrade if they were to compete with the Luftsreitkrafte. Thus, in response, the Polikarpov I-15 and I-16 models were designed by their namesake in late 1930, went into prototype testing in early 1931, and finally went into mass production by the spring, eventually replacing the I-5s and I-6s as the leading Soviet fighter model in production by the end of the year.

Polikarpov I-15 and I-16s were undeniably a welcome addition to the ranks of the Soviet Air Force, becoming a critical component for Soviet aerial defenses almost immediately after their introduction to combat, however, as fighter aircrafts, they failed to provide a Russian counterweight to German bombers, such as the infamous Dornier Do 11s that terrorized the sky above Poland with a torrent of bombardment. Yes, Polikarpov’s fighter planes worked well in air-to-air combat as a means to prevent the Heilsreich from securing air superiority and bombing enemy targets below, however, the Soviet Republic lacked the meaningful capabilities to wage bombing campaigns of its own. Under the leadership of aeronautical engineer Andrei Tupolev, the aptly-named Tupolev SB-1 fast bomber was developed throughout 1931, with the first SB-1s being introduced to the skies of eastern Europe circa the summer of that year. They soon proved themselves to be amongst the most formidable bombers of the Great War, and, while initially limited in numbers, SB-1s nonetheless proved to be an incredibly useful tool of the Soviet Air Force’s with regards to defensive operations targeting German artillery on the Eastern Front.

A Tupolev SB-1 fast bomber stationed nearby Minsk, circa September 1931.

I-15s, I-16s, and SB-1s were all undeniably welcome assets to the Soviet arsenal, noticeably slowing down German progress in the Pomeranian Offensive and shielding the heart of Poland from significant air raids for the time being, while also proving to inflict particularly devastating losses on Turkish naval forces in the Black Sea. Yet for all their utility, the simple fact of the matter was that building up the industrial capacity to produce these new models on a wide scale and dramatically increase the size of the Soviet Air Force while simultaneously developing the military organization necessary to train more conscripts for air combat would take time. The Second Three Year Plan showed promise throughout the entirety of 1931, however, its goal of fully diversifying the Soviet armed forces to the point of deterring German air superiority was a long-term objective.

In the meantime, the Russian Soviet Republic would need to devise a strategy to cling onto occupied territories in eastern Europe. The Yellow Famine started to especially take its toll on Poland going into the winter of 1931, and with Soviet agricultural output already strained by domestic demands, Moscow was unable to simply cover Polish needs via exports. This was not the case, however, for socialist states in southern Asia. With the conclusion of hostilities on the Indian and Indochinese fronts of the Great War, South Asia had more or less been capable of recovering from years of civil war, establishing stable sovereign republics from the ashes of European colonialism. This wasn’t, by any means, to say that the war effort of the South Asian socialist republics was winding down, for expeditionary forces of the Indian Union in particular were playing a significant role on the Eastern Front, but the Great War had become a more or less foreign conflict for these governments. Third International member states in Europe remained besieged by the forces of fascism, their entire domestic society and economy completely geared towards the war effort, but their South Asian counterparts had long since moved away from this bleak wartime mentality, and morale was higher than ever.

One industry that had received particular attention by the post-war South Asian socialist governments was agriculture. On the Indian Subcontinent, agricultural output had been remarkably inefficient under British colonial rule, and the destruction of agricultural infrastructure during the war on the South Asian Front had left the agricultural sectors of both the Indian Union and the People’s Republic of Madras with a declining annual growth rate upon the ratification of the Treaty of Karachi in 1927. To this end, President Subhas Chandra Bose prioritized a simultaneous increase in the agricultural and industrial capacity of the Indian Union under the country’s first Three-Year Plan, implemented starting in September 1927. Land reclamation for agricultural purposes, extensively funding the country’s nationalized farming industry, and the mass production of mechanized farming equipment were all priorities of the program, and by the conclusion of India’s first Three-Year Plan in 1930, the country’s food insecurities had largely been done away with, the agricultural sector of the Indian economy was steadily growing, and the Indian Union was ready to begin exporting agricultural products.

That being said, however, India’s agricultural exports were still fairly low, with the demands of one of the largest populations on the planet still recovering from a bloody civil war consuming the vast majority of products. This was not, however, the case for the Democratic Union of Indochina, which, upon securing its independence, was one of the largest producers of rice in the world and had plenty to export abroad. Safe from the frontlines of the Great War and well-positioned to become an international agricultural juggernaut, Indochina was well-positioned to be the breadbasket of the Third International by the beginning of 1931, and Premier Trotsky recognized this potential. On January 20th, 1931, the Treaty of Poltoratsk between the Russian Soviet Republic, Indian Union, People’s Republic of Madras, and Democratic Union of Indochina was ratified, which stipulated that the latter three agreed to sell agricultural products to Russia at a remarkably discounted price, with the intent being that the Soviet Republic would purchase agricultural goods from South Asia at little cost to then be distributed accordingly to Soviet allies and puppet regimes on the Eastern Front, particularly the famine-ridden Poland.

Of course, while the Treaty of Poltoratsk encompassed India and Madras, it was clear to the present delegations that the vast majority of agricultural exports would be arriving from Indochina given that the socialist republics of the Indian Subcontinent were still focusing on increasing domestic production before they could become leading agricultural exporters. Indeed, by the beginning of spring 1931, a consistent influx of rice flowed into Poland from Indochina and through Russia, and while continuous German bombardments made distribution to the westernmost reaches of the country at the frontlines of the Great War difficult, Indochinese rice soon became a staple of the diet of the average resident of Warsaw, and the rations of Polish and Soviet soldiers alike increasingly became rice packets. In the case of the latter, the allocation of rice to Red Army troops caused the increase in rice consumption in eastern Europe to not just be relegated to territories suffering the brunt of the Yellow Famine, for soldiers returning from service brought with them a heightened demand for rice amongst Russian civilians. By the time New Year’s Eve 1932 was celebrated in the Soviet Republic, Vietnamese fried rice was a common dish throughout the eastern bloc of the Third International, from Poland to Siberia.

Politically, Leon Trotsky sought to fend off the Pomerania Offensive by consolidating support in Soviet-occupied East Prussia, believing that the installation of an independent puppet regime would boost local support for remaining associated with the Third International. Starting in November 1930, Premier Trotsky initiated negotiations with exiled German communist revolutionaries, hoping to lay the groundwork for a Prussian Marxist-Leninist regime. Ironically, Trotsky’s regime at covertly spearheaded the quiet purging of many leading German communist figures throughout the late 1920s, most notably Rosa Luxemburg, for their more libertarian approach to socialism and criticisms of the authoritarian structure of the Bolshevik Party, and, as such, the list of potential puppet leaders for East Prussia had rapidly dwindled by fall 1930. Paul Levi, a founding member of the German Communist Party and a former associate of Vladimir Lenin during his exile in Switzerland, was ultimately selected to lead the Prussian puppet regime due to having gravitated towards Trotsky both ideologically and personally since being exiled to Russia in 1923, having publicly lauded the Bolshevik policy of “democratic centralism” as an efficient means of organizing revolutionary administration and declaring that a Russian invasion of Germany was necessary for the liberation of his homeland from fascist rule.

As such, Levi was appointed to lead the Free Socialist Republic of Prussia, officially formed on December 11th, 1930, as its chancellor and the chairman of its ruling German People’s Communist Party of Prussia (DVKP), reigning as the autocrat of the puppet state encompassing the entirety of East Prussia. A one-party Marxist-Leninist dictatorship modeled after Trotskyist Russia, Chancellor Levi had little room for internal dissent within his regime, and it was no secret the Konigsberg was taking orders from Moscow, yet the formation of an officially independent nonetheless attracted German socialist exiles from both Leninist and libertarian circles alike due to the promise of propagating the German revolution westward (indeed, the FSRP put effort into depicting itself as the first piece to spreading the Permanent Revolution to all of Germany and associating with any westward German socialist republics that may be formed in the process). Additionally, after years of rule by the foreign Red Army, the emergence of a German-led civilian government, even that of a puppet state, was welcomed by local residents, and surely enough, the Workers’ and Peasants Prussian Army swelled in numbers to confront the forces of the Kaiser-Fuhrer as morale bubbled throughout the Free Socialist Republic, now giving Germans in occupied territories a cause to rally behind in the form of liberating the Fatherland from fascism.

Flag of the Free Socialist Republic of Prussia.

Bassenheim

“I oversee the death of my nation, helpless to do anything but shout calls for help unheeded by the world.”

-Excerpt from the journal of Prime Minister Arvid Lindman of the Kingdom of Sweden, circa February 1931

Stockholm, Kingdom of Sweden, circa September 1930.

For the German Heilsreich, adaptations to changing circumstances on the Eastern Front were far less nuanced and political. Germany’s armed forces had already begun to diversify well before the beginning of the Pomeranian Offensive, and the inflexibility of national absolutism left little room for pragmatic decisions intended to boost civilian morale. Ultimately, the fact of the matter was that both strategic and political demands of the Eastern Front remained overshadowed by the Heilsreich’s greatest vulnerability, that being its dwindling resources. Italian investment in petroleum reserves in the Sahara Desert certainly helped alleviate the German oil crisis, however, these extractions were not enough to satisfy the intense hunger of the German war machine, which, beyond fuel needs being just barely supplied by a combination of Italian colonial extraction, captured oil fields in Bulgarian-occupied Romania, and trade with the neutral world, required an influx of raw materials, particularly iron, to remain satiated.

Throughout much of Phase Two, Germany’s iron ore needs had been met through trade with the Kingdom of Sweden, which, alongside the rest of Scandinavia, had carefully attempted to navigate neutrality throughout the entirety of the Great War. Lacking a strong standing army relative to the great powers of Europe, Sweden had maintained a careful policy of neutrality since the outbreak of the conflict, however, it was no secret that the sympathies of the Swedish monarchy and military layed with Germany upon the outbreak of hostilities in 1914. Indeed, throughout Phase One, the German Empire made repeated overtures towards Sweden with the goal of forming an alliance, and the trade of Swedish iron ore to Germany persisted during wartime, in large part due to the Entente’s naval blockade in the North Sea making exports to Entente member states only feasible through the Norwegian port of Narvik. Yet food shortages brought about by the Entente’s blockade ultimately pressured the Swedish government into entering into negotiations with the Entente in order to alleviate the effects of the North Sea blockade.

Since Phase One, circumstances in Sweden had changed significantly in the background of a radically altered continent. The outbreak of communist revolutions in Russia and France had put the pressure on the Swedish government to finally complete the process of reforming the country into a parliamentary democracy, with universal suffrage being implemented in 1921 while the Swedish monarchy accepted its role in political affairs as having become largely ceremonial in function. The outbreak of the British Civil War only a year later brought with it the beginning of the end of the North Sea blockade, however, by this point, the prominence of the center-left Swedish Social Democratic Workers’ Party under Prime Minister Hjalmar Branting and pressure from the pro-Third International Communist Party of Sweden caused voices for heightened neutrality to prevail against calls from conservatives and the nobility to cozy up to Berlin yet again. The Heilungscoup was the final nail in the coffin for Swedish association with Germany, as the country’s parliamentary left was repulsed by the emergence of a fascist regime to their south while, despite sympathizing with the anti-communist positions of the German Fatherland Party, the conservative King Gustav V was unsettled by the violent expulsion of Kaiser Wilhelm II from his throne, particularly given that his wife was in fact a cousin of the exiled emperor.

As a consequence of political pressures from multiple sides to move away from the Central Powers, Swedish iron exports to Germany throughout Phase Two steadily declined. They undeniably remained a notable aspect of the Swedish economy, however, it was increasingly apparent that Stockholm was in no mood to be uniquely friendly with the Heilsreich and, at times, was even poised as a potential adversary open to diplomacy with the Entente and Third International. Nonetheless, the Kingdom of Sweden was keen on playing a careful game of realpolitik, playing the Heilsreich and Soviet Republic off of each other while evading the wrath of either power. Iron ore was exported to both the Central Powers and Third International, with Stockholm being careful to not show preference towards either faction in trade relations. Meanwhile, Sweden continued to maintain a respectable navy and laid minefields along its coastline to deter invasion, although Sweden’s unavoidable population disparity compared to either Germany or Russia meant that, no matter how painful it could make any attempt at conquest, it could never win a defensive conflict against its fearsome neighbors. All it could do was avoid provoking either the eagle or the bear as much as possible and hope that neither would decide to turn Sweden into their next prey.

For factors outside of Swedish control, however, their time was up come early 1931. Always yearning for more resources to feed his war effort, Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm determined that a rapid takeover of Sweden in order to both assume direct control of the country’s iron supply and acquire new ports to wage naval warfare against the Red Navy from would be worth briefly diverting resources away from the Eastern Front. Critically, the Kingdom of Sweden, while well-defended navally, lacked significant aerial defenses, which meant that a complete bombardment of the country followed by a barrage of paratroopers landing in the country’s south while the German navy distracted its tough but nonetheless much smaller Swedish counterpart would likely be enough to force the entirety of Sweden under the control of the Heilsreich within a handful of months at most. Thus, by quietly diverting LK forces from the war of attrition on the Western Front and the dogfights over the waters of the North Sea, August Wilhelm amassed the forces for a pre-emptive strike on Sweden, codenamed Operation Bassenheim. Named after the first grandmaster of the Teutonic Order, this airborne assault of Sweden was to be overseen by Major General Manfred von Richthofen of the Luftsreitkrafte. A veteran of Phase One of the Great War who had risen through the LK ranks on the Western Front before being transferred to command forces in the east upon the beginning of Operation Ascania, Richthofen had long been regarded as one of the greatest fighter pilots in the Great War, earning the nickname of the “Red Baron” in his youth.

Major General Manfried von Richthofen of the Luftsreitkrafte, circa March 1930.

By 1931, Richthofen’s infamous days as an ace-of-aces feared by the pilots of the Entente were well behind him, but in their place, the Red Baron had become a respected commanding officer of LK forces on the Eastern Front, having coordinated the 1930 herbicidal warfare campaign against Poland alongside Hermann Goering and the Kaiser-Fuhrer themselves in some capacity, Additionally, while obviously not as influential in military policy as superiors in the LK, nor as front and center in aerial combat as he was during Phase One, Richthofen had remained a national hero in Germany, oftentimes sent out on nationwide tours to boost morale, an especially useful tool for Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm due to Richthofen’s Prussian aristocratic heritage rendering the Red Baron an early supporter of national absolutism, given that he stood to gain power under a political arrangement that favored the rule of the traditional nobility. But with almost two decades of aerial warfare experience under his belt, Major General Richthofen’s primary qualifications for presiding over Operation Bassenheim were obvious, and the fact that the beloved Red Baron spearheading the conquest of Sweden would make for an easy propaganda win for the national absolutist regime was simply a nice bonus.

On the morning of February 1st, 1931, Major General Richthofen’s Operation Bassenheim began with a strategic bombing campaign by the Luftsreitkrafte that targeted cities and naval ports along the southern Swedish coastline. With Sweden not expecting a surprise attack, its armed forces were caught completely off guard, and the damage of even the opening hours of Operation Bassenheim was devastating. Within the span of only a handful of hours, an indiscriminate strategic bombing campaign had decimated cities as far north as Gothenburg, and, while not a primary target in the opening pre-emptive strike of Operation Bassenheim, Stockholm was not spared a few bombs by Dornier Do 11s. For the next few weeks, Major General Richthofen would continue to lead a furious strategic bombing campaign across southern Sweden, hoping to accomplish the decimation of the country’s infrastructure and defenses prior to staging an airborne assault and subsequent rapid ground offensive. With Sweden itself lacking a large air force, this was an easy task. The Swedish Air Force’s less than seven hundred combat-ready aircraft were dwarfed by even a fraction of the LK arsenal, and air supremacy was accomplished by the Heilsreich in Operation Bassenheim within a little over a week following the initial bombing run on February 1st.

After only a little more than two weeks, the meager Swedish Air Force had been all but annihilated and much of the Swedish Navy, while still desperately fighting against its German enemy, lay ruined at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, largely thanks to the Red Baron’s bombers. Impressively, all of this had been done with relatively minimal German casualties. Since the dawn of the 1920s, the Kingdom of Sweden had prepared for deterring an invasion by sea, a task that, by all accounts, it would’ve performed decently. But in a world where aircraft were a fundamental component of any military force, not to mention a field that Germany in particular excelled at, these defenses were more or less bypassed altogether in favor of simply landing paratroopers of the Heilsreich on Swedish soil. Simply put, Stockholm had prepared for a war that never was, leaving it almost defenseless against the true invasion that Berlin had concocted. On February 16th, 1931, the first aerial assaults of Operation Bassenheim were conducted, with German units being deployed outside of Malmo, Helsingborg, Karlshamm, Karlskrona, and Kalmar within minutes of each other. It was hoped that all five cities could be secured within days, followed by the airborne assaults linking up with each other and establishing a foothold in the Swedish south from which an offensive towards Stockholm could be waged, while capture of the Karlskrona naval base, the largest in Sweden, would lay a crippling blow on the already severely weakened Swedish Navy.

German air assault during the opening stages of the Battle of Malmo, circa February 1931.

The response to the airborne invasions of Operation Bassenheim would technically be the first engagements of the Great War where the Swedish Army, previously on the sidelines during the LK strategic bombing campaign, played a predominant role, however, Richthofen’s bombardment of and aerial superiority over southern Sweden, as well as the destruction of key supply lines via strategic bombing, put the fighting force at a significant disadvantage from the get-go. Swedish troops hid within the ruins of their country’s cities and fought admirably, however, the Imperial German Army was protected by the umbrella of the Luftsreitkrafte, whose bombing runs often eliminated Swedish platoons before they even had a chance to fight. Despite their larger sizes relative to the three other targets, Malmo and Helsingborg both fell relatively quickly due to their distance away from both the Karlskrona naval base and the capital city of Stockholm not making their defense as high of a priority as targets to their east. In the case of both cities, German Army forces landed on their outskirts, consolidating their control over towns and rural territories, thus encircling both cities, and then proceeding to rapidly push inwards to win their respective battles. Casualties were high (more generally, the February 16th air assaults of southern Sweden were easily the bloodiest engagements for German forces during the entirety of Operation Bassenheim), and Swedes stuck behind enemy lines fiercely waged isolated guerrilla attacks for days after falling under the occupation of the Heilsreich, but both Malmo and Helsingborg had been conquered by dusk, and the German Army moved on to conducting a campaign to link up occupying forces in both cities.

The situation further east was far more intense. Located in strategically critical areas, both Karlshamn and Kalmar were much more well-defended than either Malmo or Helsingborg, and Kalmar’s relative distance from Germany in particular meant that paratroopers landing outside of the city did not have as many LK aircraft protecting them than counterparts to their southwest, even if German air supremacy had nonetheless been established over Kalmar. But in Karlskrona, where the true prize of the city’s naval port stood, defenses were predictably much more extensive. To make matters even more complicated, Karlskrona itself was spread out across the Blekinge Archipelago, including the heart of the city, which meant that the German Army would have to make its way from the landing point to Karlskrona’s north on the Swedish mainland across an archipelago of islands. Unsurprisingly, despite being the largest of the five assault forces and receiving the most aerial support from the Luftsreitkrafte, the infantry divisions deployed to engage at the Battle of Karlskrona failed to step foot on the island of Trosso within the first day of combat.

Swedish soldiers manning a machine gun at the Battle of Karlskrona, circa February 1931.

Further north, the Battle of Kalmar moved slower than Heilsreich officials had hoped, however, the German Army nonetheless dislodged Swedish forces from the city by the midnight of February 17th, after several hours of exhausting combat. The real problem faced by the occupying divisions of Kalmar came after the battle, when the Swedish Army laid siege to the city in an attempt to liberate it. Relatively isolated from reinforcements and protection by Dornier Do 11 strategic bombing, the success of the German forces at Kalmar in the long term was dependent upon a victory at Karlskrona fast enough for Richthofen to turn his attention northwards and reinforce Kalmar in preparation for an offensive towards Stockholm. In the meantime, the most that the conquerors of Kalmar could do was wait, attempt to survive each day, and hope that Operation Bassenheim would succeed.

In Karlshamn, combat, while still more fearsome than in the southwest due to its strategic position, ultimately went by much more quickly than the battles in either Karlskrona or Kalmar, in large part thanks to the city’s small size and easily traversable geography making it a straightforward target for the German Army. Within a handful of hours after paratroopers landed to Karlshamn’s northeast, the city had been secured by the Heilsreich, defenses were consolidated along the banks of the Miean River to its west, and German Army forces began their eastward push to link up with divisions fighting at Karlskrona. For the next four days, German forces pushed eastward from Karlshamn, while the LK deployed additional paratroopers and equipment in in order to secure their control over the city and surrounding area, anticipating that said equipment would soon both flow into the Battle of Karlskrona and lay the foundation for a launching pad of a subsequent northward offensive. Surely enough, after a series of minor engagements within the approximately fifty kilometer stretch of coastal land between Karlshamn and Karlskrona, forces from the former linked up with the latter just to the northwest of Karlskrona on February 21st, thereby providing the German Army with the capacity necessary to finish off the battle for Sweden’s most pivotal naval base.

Surely enough, German forces broke through Swedish defenses and stepped foot onto Trosso, where the heart of Karlskrona and its naval base were located, on the morning of February 22nd thanks to the influx of reinforcements from the west. Fighting was fierce, with Karlskrona being painfully seized street by street, however, it nonetheless soon became apparent that the Swedish Army could no longer hold back the Heilsreich’s onslaught. Yes, messy close quarters combat and high casualties persisted throughout the day, but the German Army was nonetheless progressing at an efficient rate, pushing the defending Swedes to their last stand on the island of Stumholmen by the late afternoon. With a fleet of bombers assisting in uprooting the Swedish Army from above, German forces ultimately captured Stumholmen, and, by extension, a critical component of the Karlskrona naval base, within a span of less than two hours after taking over the entirety of Trosso. Swedish Army forces continued to hunker down on islands scattered throughout the Blekinge Archipelago, however, these troops were completely isolated from aid, and those that did not capitulate were largely bombed by the Luftsreitkrafte. Within hours, remaining holdouts of resistance within the Archipelago surrendered, thus securing a German victory at the Battle of Karlskrona by the end of February 22nd, 1931, and placing Sweden’s most important naval base decisively under the jackboot of fascist imperialism.

Warships of the Imperial Navy of the German Heilsreich occupying the Blekinge Archipelago, circa February 1931.

With Karlskrona and its famed naval base under German control, whatever remained of Swedish defenses against Operation Bassenheim suffered a crippling blow. On top of Sweden losing a critical component to its naval war effort, the Heilsreich had won an admittedly ruined yet nonetheless reasonably operational and exceptionally well-positioned naval port from which to project power throughout the Baltic Sea. Furthermore, with the capture of Karlskrona, alongside several other Swedish port cities, air assaults were no longer the sole means from which German manpower and resources could be deployed on Swedish territory. Within the coming days, the Imperial Navy docked within the harbors of Karlskrona, deploying units and tanks alike in preparation for the concluding offensives of Operation Bassenheim. Sweden would valiantly struggle to fight on beyond the Battle of Karlskrona, but for all intents and purposes it was apparent that the Swedes had lost in all but name, and it was only a matter of time until an official capitulation acknowledged this grim reality.

Over the coming days, Sweden would die. With Karlskrona captured, forces occupying the city, placed under the command of General Theodore Duesterberg by Manfried von Richthofen, who continued to lead the aerial element of Operation Bassenheim and oversee the general logistics of the entire campaign, began a rapid northward push towards German forces still clinging onto Kalmar, hoping to utilize the city as a launching pad towards Stockholm. Surely enough, with the Swedish Army decimated after the Battle of Karlskrona, Duesterberg faced minimal resistance in his northward push and stepped foot in a ruined Kalmar on February 28th, 1931, delivering yet another harsh blow to Swedish defenses in the process by allowing for German troops at Kalmar to go on the offensive for the first time since the initial victory on February 16th. Meanwhile, in the west, Malmo and Helsingborg had long since linked up while Sweden focused on defending Karlskrona, having since turned their attention towards connecting with Duesterberg’s forces via an offensive to their northeast. This strategy did leave cities to their northwest in Swedish hands, however, the area’s relative strategic insignificance combined with any northwestern offensive being risky due to the area in question being blocked off by Danish waters meant that it was ignored for the time being, not to mention that many undefended settlements in the region simply capitulated without a fight. Sweden couldn’t spare troops beyond the bulk of the German offensive, so Richthofen could effectively choose his preferred battlefield.

A rapid offensive was launched from Malmo towards Karlshamn on February 20th, with minimal resistance faced by German forces. After the span of only three days, troops from Malmo linked up with their counterparts from Karlshamn following a victory at the Battle of Nymolla on February 23rd. Forces from Malmo and Helsingborg were primarily tasked with eliminating remaining Swedish holdouts in the country’s south whilst Duesterberg invaded Kalmar and were therefore largely not present at the battle for said city, however, by the time that Kalmar had been reached, the southern Swedish coastline was entirely in German hands, and all Army forces of the Heilsreich present in Sweden were now unified under Duesterberg’s command, ready for a final northwards offensive towards Stockholm. With the Swedish armed forces in ruin, German air superiority over the country solidified, and a steady influx of supplies to Duesterberg’s forces arriving by sea, defeat for the Kingdom of Sweden was now inevitable.

Surely enough, starting on February 28th, the entire German apparatus fighting in Operation Bassenheim began a rapid charge towards Stockholm. Day after day, new cities fell under the banner of the Heilsreich and the German advance accelerated. The Swedish strategy was to make a final stand in their capital city, but in reality, their only real chance at survival was to hold out on the desperate hope that reinforcements from anti-German powers throughout Europe could arrive at some point. Ultimately, this hope was futile. The Third International had indeed thrown away exclusively allying itself with fellow socialist revolutionaries in favor of a more pragmatic foreign policy in Phase Three, as was exemplified with its cooperation with the right-wing Kingdom of Romania, however, regardless of Third International willingness to aid Sweden, the reality on the ground was that supplying the country was near-impossible. German naval warfare in the Baltic Sea prevented Russia from establishing any supply line to the Swedes, Berlin’s air superiority over the country rendered deploying any troops or material aid in Sweden incredibly difficult, and the Third International was spread increasingly thin regardless. The most Sweden received in terms of foreign aid during the entirety of Operation Bassenheim was a small influx of munitions and Phase One tanks from the Workers’ Commonwealth and Ireland. Otherwise, Sweden was alone.

After over a week of combat and rapid advances, Theodore Duesterberg’s army besieged Stockholm on March 8th, 1931. Without Third International support on its way, the fate of this battle had long since been predetermined. It was reported from the frontlines that whatever remained of the Swedish Army fought valiantly at the Battle of Stockholm, knowing very well that this could be the final chapter in their nation’s long history, but it was ultimately for nought. With the entirety of Operation Bassenheim’s invasion force converging upon Stockholm, Duesterberg secured decisive control of the city just a little more than an hour before March 8th’s midnight. Swedish defenses had been obliterated, and the government of the Kingdom of Sweden, which had fled northwards to the city of Gavle days prior, unconditionally surrendered to the German Heilsreich less than twenty-four hours later, recognizing that the fight was over. August Wilhem’s gambit to secure more iron had paid off at an efficient pace, and while casualties had been notably higher than desired, the cost to Germany was deemed to have been outweighed by the material benefits. Operation Bassenheim had succeeded.

The Treaty of Gothenburg would solidify Sweden’s role under German rule. Citing pan-Germanic ideology pervasive within the ranks of the German Fatherland Party that viewed Scandinavia as a component of the wider German nation as a justification, Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm pushed for the direct annexation of Sweden into the Heilsreich. In reality, the policy of the direct rule of Sweden from Berlin was more of a practical consideration than an ideological one, as August Wilhelm sought to maintain total German control over Swedish iron ore to fuel his war effort and believed that Sweden’s relatively small population of a little over six million (only approximately ten percent the size of the population of Germany at the time) would make a permanent military occupation easy enough to justify maintaining. To this end, all Swedish iron ore reserves and mines were declared a private holding of the German crown itself, thereby placing the Kaiser-Fuhrer into total control over his ultimate spoil of the war against Sweden.

Politically, Sweden was partitioned into the margraviates of Götland, Svealand, and Norrland, hoping that breaking up the nation into its three historical regions would reduce nationalistic sentiments and ease the process of assimilation into Germany. Furthermore, the leadership of these respective fiefs was selected in relation to the unique strategic benefits provided by each, with Götland, the center of Swedish naval capacity, being ruled over by head of the German Maritime Wartime Command, Admiral Adolf von Trotha, Svealand, the political and cultural center of Sweden that laid particularly close to the Russian-controlled Baltics, being placed under the command of the aristocratic General Hans Jürgen Graf von Blumenthal, an officer capable of implementing the ideology of national absolutism and coordinating military efforts in Scandinavia against Russia while not being despised by Swedes for participating in the destructive Operation Bassenheim (like Richthofen and Duesterberg), and Norrland, where the bulk of Swedish ore deposits were located, being the domain of August von Mackensen, an elderly monarchist and close ally of the Kaiser-Fuhrer who could be trusted to oversee a steady extraction operation and command defenses against any local resistance.

Throughout all three margraviates, however, some common policies were implemented. As a Germanic people, ethnic Swedes were considered equal to Germans under the Heilsreich’s racial policies, and while cultural assimilation was promoted through mandatory education in German language, history, and culture, emphasizing a pan-Germanic national identity and lineage in propaganda, and rebuilding Swedish cities with German-influenced architecture, among other strategies, speaking Swedish in public was acceptable throughout the margraviates, excluding in any work for the state or military. Additionally, while the Heilsreich was careful not to conscript any Swedes immediately following the annexation of their country, Swedish men were free to enlist, and with military service promising high pay and the opportunity to socially advance under the new order, many opted to fight for their conqueror.

Most interestingly, however, was the Heilsreich’s economic policy in the Swedish margraviates. Having abstained from the bloodshed of the Great War aside from the two months Operation Bassenheim was waged, much of Sweden’s industrial capacity was intact relative to German-occupied territories much closer to the frontlines, even after Richthofen’s bombing campaign. As such, the Heilsreich could not afford to deindustrialize Swedish’s largest urban centers, which were rebuilt into the domains of factories owned by German corporations, nobles, and the armed forces itself, all contributing production to the war effort. In these areas, locals who lost their homes in Operation Bassenheim were often pushed out in favor of new German bourgeois residents, while the enslaved labor of those deemed “inferior” by the DVP became the backbone of production in Swedish factories.

For the bulk of Sweden, however, the Heilsreich feared armed resistance and, to this end, the margraves were directed to deindustrialize their territories under the belief that a rural peasant society could not wage any effective insurrection against one of the most mechanized armies in human history. In the Swedish countryside, the Industrial Revolution was gradually reversed, and lands were divided up into rural manors operated by either Germans or Swedish collaborators in the shadows of ruined towns where electricity had once powered each building and automobiles were a common sight on the streets. The Swedish populace was offered the opportunity to work on these manors as peasants and provide subsistence for themselves or, in more rare instances, were offered small plots of land for them to privately own, with many taking up this opportunity for no other reason than their livelihoods being obliterated by the German total war over Sweden. By 1932, hundreds of thousands of urban Swedes had already moved to manors to become the base of a 20th Century rural peasantry, which in turn alleviated food shortages within Germany by turning Sweden into the breadbasket of the Heilsreich. In Sweden, far more so than anywhere else ruled by the Heilsreich, national absolutism had resurrected feudalism under the fascist jackboot.

Peasants laboring on a manor in the Margraviate of Svealand, April 1931.

Via Operation Bassenheim, Germany had won new industrial centers, new farmland, and, most crucially, its prize of iron ore, now fueling its war machine against the Russian Soviet Republic. All the while, the race for East Prussia continued to Sweden’s southeast, and even if Germany bought itself more supplies and time to hold out in the constant war of attrition it had trapped itself within, it still remained to be seen if General Erich Ludendorff would reach Konigsberg by the end of the year, and if the invasion of Sweden would meaningfully help accelerate the German push on the Eastern Front in time. Yet further south, politics, religion, and warfare would soon converge to the benefit of the Central Powers. Benito Mussolini, the founder of fascist ideology, was carefully making moves to gather more nations to the cause of the Central Powers, but not with ideology. Rather, theology was to be their calling under his strategy.

It was time for the beginning of the Tenth Crusade.

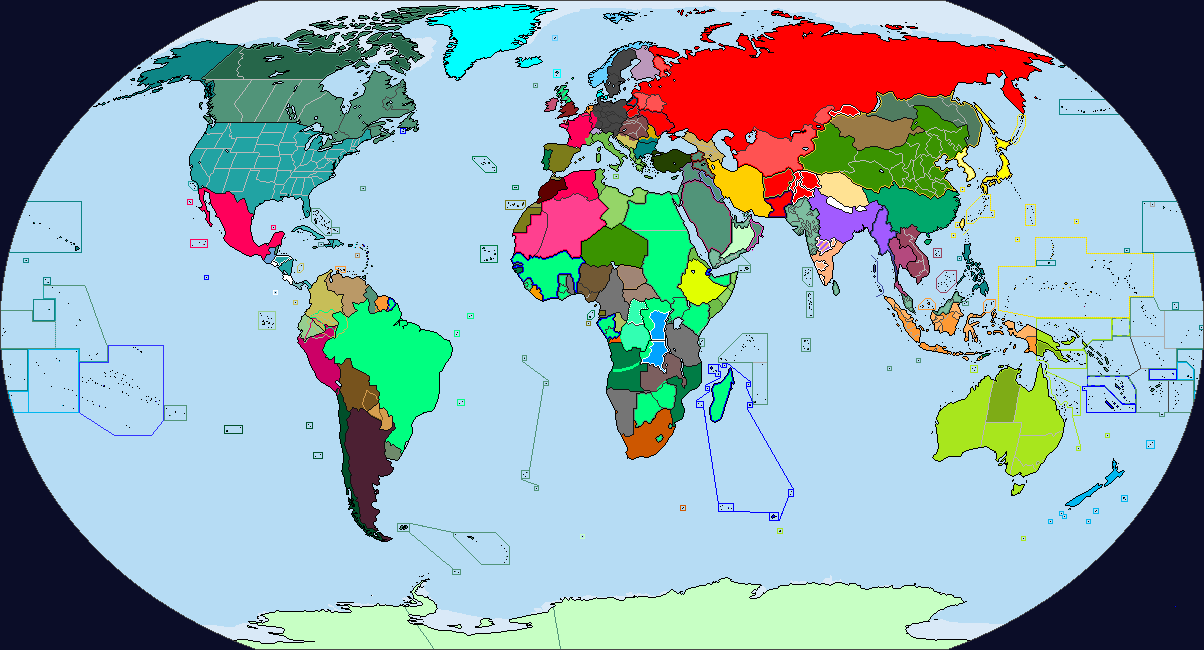

Map of the World, circa March 1931.

“Poland shall be the knife which your righteous empire will thrust into the heart of the Marxist savages.”

-Excerpt from a letter written by General Erich Ludendorff to Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm, circa April 1930.

Dornier Do 13 light bomber flying over Poland, circa April 1930.

On April 12th, 1930, the tides of the Great War had shifted yet again when German forces won a decisive breakthrough against Red Army defense in Swiecko. The war of attrition along the banks of the Oder River that had more or less been the status quo along the Eastern Front since the aftermath of the Battle of Berlin was broken within the span of mere hours, forcing General Stalin in retreat as the rival General Ludendorff followed in pursuit. The Eastern Front was once again fluid, and for the first time in years, it was flowing in favor of the Central Powers. The springtime offensives into central Poland and Pomerania were, however, brief in their success. By the end of May 1930, the Red Army had reinforced its position along the Eastern Front, in large part thanks to reinforcements from the Indian Union, halting further German advances at the Battle of Schneidemuhl. Ludendorff had indeed made progress, and Stalin remained on the defensive, but the quick overrunning of Poland that August Wilhelm and his military’s high command had so desperately desired remained out of reach, at least for the time being.

Nonetheless, going into the summer of 1930, the relentless campaign of total war waged over Polish skies continued. Soviet aerial defenses prevented the Luftstreitkrafte from penetrating too far behind enemy lines, but for those unfortunate enough to live in the western reaches of the country, close to enemy lines, German air raids drenched the landscape in a vile mixture of bombs and poisonous chemicals. Under the philosophy of total war, there was frighteningly little discrimination between civilian and military infrastructure, and as such, thousands of civilians remaining in western Poland, an area already devastated by prior military campaigns jostling for the territory as a corridor between Germany and Russia over the past two decades, perished at the hands of the Heilsreich, whose leadership cared little for human life. After all, under the reign of national absolutism, mankind’s role was that of an asset of the German nation and her physical manifestation in the form of the Kaiser-Fuhrer. If this duty could not be fulfilled, death was viewed as acceptable.

To this end, as the summer of 1930 approached, August Wilhelm began to investigate new tactics to utilize against the Third International. Having already embraced scorched earth tactics, the Kaiser-Fuhrer took an interest in effectively starving off Soviet frontlines by waging a poisonbombing campaign that would target deploying mustard gas on agricultural lands in order to poison soil and decimate crop production. Nearly sixteen years of chemical warfare had already had a devastating impact on European agriculture, with millions of civilians across the continent perishing from famine related to the Great War by the beginning of Phase Three and entire villages annihilated as chemicals seeping into the ground made them incapable of supporting human habitation, let alone farming. Yet these “zones mortes” (dead zones), as the government of the French Commune deemed them, were not intentional weapons in and of themselves, rather a vile scar carved into the earth itself by well over a decade of industrialized warfare. As such, they tended to develop along the frontlines of wars of attrition, with ribbons of zones mortes being particularly infamous throughout northern and eastern France. Conversely, Poland, which had often been rapidly exchanged between the German and Russian war machines, had actually been spared many of the conditions that produced significant zones mortes.