You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Man-Made Hell: The History of the Great War and Beyond

- Thread starter ETGalaxy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 30 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twelve: Defend of Die - Part Two Interlude Eleven: Europe Circa November 1929 Interlude Twelve: Scrapped Content Chapter Thirteen: A Bold New World Chapter Fourteen: Growing Storm Clouds Chapter Fifteen: Those Who Escaped Chapter Sixteen: A Twist of Fate Man-Made Hell: The Modern Tragedy Novel ReleaseWhat happened to the Republic of the Rif in TTL? I'm guessing that France helped Spain crush it as in OTL (not much else to use the army for) before the Commune invaded Algeria. I wonder if there's room for another rebellion in the future... perhaps one that would be supported openly by Morocco? Especially if Spain sees significant civil unrest.

Speaking of which, how well-developed is the Moroccan army and bureaucracy at this point? And what are their relationships with the Commune?

Speaking of which, how well-developed is the Moroccan army and bureaucracy at this point? And what are their relationships with the Commune?

The Republic of the Rif and its rebellion was more or less the same as OTL. Abd el-Krim led an uprising in 1921 and was subsequently defeated by the Spanish and Republicans come 1926. A future rebellion in Spanish territory isn't so much a concern at the moment, but rather potential Moroccan encroachment on Spanish colonies. The Kingdom of Morocco regards the Spanish protectorate of Morocco as occupied territory, thus meaning that war between the two countries is increasingly likely.What happened to the Republic of the Rif in TTL? I'm guessing that France helped Spain crush it as in OTL (not much else to use the army for) before the Commune invaded Algeria. I wonder if there's room for another rebellion in the future... perhaps one that would be supported openly by Morocco? Especially if Spain sees significant civil unrest.

The Moroccan bureaucracy currently consists of members of the Alaouite Dynasty and leaders of secessionist rebellions from colonial times, including Abd el-Krim. As for its armed forces, Morocco doesn't have a very large army upon independence and isn't particularly interested in entering the Great War anytime soon, however, territorial disputes with Spain have incentivized a military buildup in the months since the expulsion of the French. Morocco and the French Commune obviously have significant ideological differences that prevent them from being particularly close, but neither nation is interested in going to war with the other, so they maintain cordial relations with each other for the time being.Speaking of which, how well-developed is the Moroccan army and bureaucracy at this point? And what are their relationships with the Commune?

Interlude Eleven: Europe Circa November 1929

Here's two versions of the same map of Europe circa November 1929 (the end of Phase Two) that I quickly whipped up over the last few days:

Europe circa November 1929 (with film static)

Europe circa November 1929 (without film static)

Europe circa November 1929 (with film static)

Europe circa November 1929 (without film static)

Dang, Red Poland is small. Do the Soviets plan to give them more of their former land in the future, taken from germany, if/when they start advancing again?

EDIT: I suspect that Transcaucasia will get invaded for the Baku oil at some point.

EDIT: I suspect that Transcaucasia will get invaded for the Baku oil at some point.

The plan was originally to give Poland everything east of the Oder, with the exception of East Prussia, once the Soviets won the Battle of Berlin, however, now that the Germans are pushing towards Poland and this territory is at risk of invasion, the Russians don't view the integration of this territory into Poland as practical at the moment and are basically waiting for the Germans to be pushed back west before the map is redrawn again.Dang, Red Poland is small. Do the Soviets plan to give them more of their former land in the future, taken from germany, if/when they start advancing again?

Interlude Twelve: Scrapped Content

Hello everyone! Chapter Thirteen is coming along smoothly, so expect it to be released either in late July or early August. In the meantime, awhile back I mentioned that I'd be interested in posting some scrapped ideas for the TL, and I thought now would be a good time to post some of these ideas as a unique interlude.

- For starters, let's talk about stuff related to the British. Some of you may recall this line from chapter one:

"The Germans tried to prevent the United Kingdom, the global superpower of the 19th Century, from entering the Great War, however, it was just impossible to tame the great British lion. It would take Mosley to do that."

This was my first hint at Oswald Mosley being in the TL, and it also set up that he would have to do something related to taking control of and/or defeating Great Britain. When I first came up with the basic idea for the TL, the idea I had was that the Central Powers would back Oswald Mosley leading a fascist uprising in Great Britain, which would ultimately result in the establishment of a pro-CP fascist British state. Basically, Operation Sealion but with a degree of collaboration from British fascists. On top of being implausible and very cliche, this concept made my idea at the time for the British Loyalists to be the de facto leadership of the Entente (this was before I landed on Brazil becoming the dominant power within the alliance) less believable, given that I couldn't buy an exiled British Empire being an effective global power. This made me decide that Mosley would lead an invasion of Great Britain on behalf of the Loyalists, although the original plan was that he'd take over all of Great Britain and completely eliminate the Workers' Commonwealth. I eventually came around to really liking the WC as a country to explore (and in hindsight, I don't know how much I could justify the Western Front holding out without some degree of British support), so I decided to keep around a rump Commonwealth after Mosley's invasion. Only giving the Loyalists northern Great Britain also worked out better once I went for having the Entente be led by Brazil, thus meaning I didn't need a British superpower to exist.

- One weird idea I had early into creating MMH was having Austria-Hungary get taken over by a fascist regime led by Adolf Hitler. The basic premise behind this was that Hitler would've been accepted into the Austro-Hungarian army and would subsequently rise through the ranks of the armed forces before seizing away power from the empire's historical constitutional monarchy (I never got all that far into how exactly he'd seize power; IIRC I was going to have him stage a coup and install a fascist military junta). Hitler's regime was supposed to be built around German ethnonationalism, and would thus persecute the Hungarians and other non-German groups throughout Austria-Hungary in an attempt to create a "pure Austrian Empire" of some kind. This regime was supposed to eventually become too crazy for even Germany and Italy and would therefore be invaded and partitioned by its aforementioned allies at some point. I gradually lost interest in this idea, so it was scrapped in favor of Austria-Hungary collapsing into Transleithania, Illyria, and territories annexed by the Heilsreich, which I personally think makes for a more interesting scenario.

- Back in the "Glimpse Into the Future" interlude (the majority of content there has still yet to happen within the actual chapters, so don't check it out if you don't want to be spoiled), I mentioned how the German Empire-in-Exile would annex the Belgian Congo in 1925 and subsequently become referred to as Mittelafrika. The full extent of Germany-in-Exile's expansion was actually supposed to be a lot bigger than what the interlude promised, with an empire the size of the OTL Mittelafrika proposal being the initial plan. The reason this concept got cut wasn't so much that I didn't like the concept, but rather that taking time to focus on the Kaiser's empire-building in Africa didn't narratively fit into any of the updates. Since scrapping the idea for Mittelafrika, I haven't focused on the Belgian Congo at all, but I have plans for focusing on the region soon, and I personally like the current plan for the region more than what I had originally thought up.

- Leonard Wood was originally going to be the Republican nominee, and ultimately victor, in the 1920 US presidential election as opposed to Hiram Johnson. I had run with the assumption that Wood was going to be president up to when I was actually writing chapter three, however, while researching the 1920 RNC, I ultimately decided that Johnson made much more sense as the nominee, mainly because I couldn't see a military officer being the preferred candidate of the Roosevelt wing of the Republican Party in a TL where the United States never entered WWI. As for what the Wood administration was going to look like, aside from specific details, I was planning on it being very similar to the presidency of Hiram Johnson that was put into the final version, with Wood governing as a progressive Republican. I did have the idea of the Hoover Dam being called the Wood Dam ITTL though.

- Moving onto China, I originally planned on having a unified Chinese state as opposed to the North-South divide along the Yangtze River that I ultimately went with. This united China would've more or less served the same narrative role as the Chinese Federation in the final version by being Japan's number two within the East Asian Co-Prosperity. Having China in its entirety be a part of the EACPS felt like a bit too much of a Co-Prosperity-wank, hence why I divided the country in two. In the original draft of chapter three, Yuan Shikai's Empire of China was also supposed to survive and effectively play the role of the Chinese Federation, however, this idea was more born out of my lack of knowledge on 20th Century Chinese history at the time than anything else. Once I learned just how unstable the Empire of China was, how it wasn't likely to align itself with the Japanese, and was also already on its way out by the time Japan intervenes in the Chinese Civil War in MMH, I scrapped preserving the Empire of China in favor of keeping the Beiyang Government around as a Japanese ally instead.

- One of the weirder ideas I had going into writing MMH was having the Kingdom of Italy be the dominant power within the Central Powers. While coming up with the very early concept of the TL, for whatever reason I landed on a very powerful Italy, ultimately eclipsing even Germany, as a main point of the TL. This was definitely a unique concept (hence why I think I stuck with it for awhile), but once I started writing and doing research for MMH, the idea of Italy running the Central Powers gradually fell apart. Italy couldn't plausibly develop a military and industrial capacity greater than that of a German Empire in its prime, not to mention that it would have narratively been kind of awkward for de facto leadership of the Central Powers to swap from Germany to Italy, a country that wasn't even involved in the Great War for the vast majority of Phase One. I think the Heilsreich makes for a much more unique "main antagonist" than "fascist Italy but bigger" anyway, so scrapping the concept for Italy ultimately worked out in the end.

Always cool to get a peak behind the curtain of TL writing. Seems that your vision for the Entente in particular has shifted a lot as the TL developed.

Yeah, shoe-horning Hitler into power is very cliche. Beyond that, I think a lot of "was a soldier in WW1, became politically important in WW2 OTL" characters might not become prominent simply due to dying in the much more intense Great War.

The Kaiser being able to go empire-building in Africa was questionable anyway. I'm looking forwards to seeing what you're planning. Curious what's going on in Belgian Congo, since the Belgian government has been exiled there for over a decade now.

Italy being the leader of the central powers would be quite weird, the Heilsreich makes more sense for now. That said, since Italy did stay out of phase one and wasn't involved in the worst of the phase two fighting, by late phase 3 or going into phase 4 I think it would be believable for Italy to start to eclipse Germany in importance: Italy's less damaged state might allow it to keep fighting effectively after Germany's fighting strength starts running out from two+ decades of war.

Yeah, shoe-horning Hitler into power is very cliche. Beyond that, I think a lot of "was a soldier in WW1, became politically important in WW2 OTL" characters might not become prominent simply due to dying in the much more intense Great War.

The Kaiser being able to go empire-building in Africa was questionable anyway. I'm looking forwards to seeing what you're planning. Curious what's going on in Belgian Congo, since the Belgian government has been exiled there for over a decade now.

Italy being the leader of the central powers would be quite weird, the Heilsreich makes more sense for now. That said, since Italy did stay out of phase one and wasn't involved in the worst of the phase two fighting, by late phase 3 or going into phase 4 I think it would be believable for Italy to start to eclipse Germany in importance: Italy's less damaged state might allow it to keep fighting effectively after Germany's fighting strength starts running out from two+ decades of war.

Not sure the UK would allow a indepdent Kurdistan, if only to appease Iran to ensure their land, however I can see a kingdom ruled by a Kurdish monarchy that calls itself something different.

Syria looks far larger here with the Turkish and Iraq bits added, over all the middle east looks quite different.

Syria looks far larger here with the Turkish and Iraq bits added, over all the middle east looks quite different.

Iran is half-way to being a puppet of the British Empire anyway at this point in history. In OTL a large chunk of the country was outright occupied by the Brits during WW1.

By the way, you mentioned your plans for China changing a lot as you read more about the early warlord era, I would like to know what places you went to get this useful information?

Someone had already made a reference to the gamerwelt of TNO's "African Devastation" superevent. On topic of TNO, that mod has an easter egg in the files:

It's called "Punished Stalin". The last update did mention he got badly scarred from a plane crash after evacuating Berlin, and lost some of his tactical acumen. I wonder if he looks something like this?

Speaking of devastation, people have suggested that the late stage of the war gets rather warlord-y as the broken countries have trouble controlling their territory. The Worker's Commonwealth might have bigger problems with this than other, since the Communal Defense Act allowed regions to form their own independent militias, supplied with arms by the government. This was an effective emergency measure in the face of invasion, but in the long term if the central government loses its legitimacy and/or the national army gets utterly gutted, than unhappy towns could really easily rebel flout the government's authority.

EDIT: ALso, you mentioned that East Prussia was a bit of German territory not slaated to become part of Poland before the battle of berlin went sideways, but I think it would have made sense for Poland to try claiming the southern half of East Prussia, where the Masurian slavs are a large chunk of the population.

By the way, you mentioned your plans for China changing a lot as you read more about the early warlord era, I would like to know what places you went to get this useful information?

Someone had already made a reference to the gamerwelt of TNO's "African Devastation" superevent. On topic of TNO, that mod has an easter egg in the files:

It's called "Punished Stalin". The last update did mention he got badly scarred from a plane crash after evacuating Berlin, and lost some of his tactical acumen. I wonder if he looks something like this?

Speaking of devastation, people have suggested that the late stage of the war gets rather warlord-y as the broken countries have trouble controlling their territory. The Worker's Commonwealth might have bigger problems with this than other, since the Communal Defense Act allowed regions to form their own independent militias, supplied with arms by the government. This was an effective emergency measure in the face of invasion, but in the long term if the central government loses its legitimacy and/or the national army gets utterly gutted, than unhappy towns could really easily rebel flout the government's authority.

EDIT: ALso, you mentioned that East Prussia was a bit of German territory not slaated to become part of Poland before the battle of berlin went sideways, but I think it would have made sense for Poland to try claiming the southern half of East Prussia, where the Masurian slavs are a large chunk of the population.

Last edited:

As @generalurist pointed out, Iran isn't really in a position to pressure the British into not forming an independent Kurdistan in the 1920s.Not sure the UK would allow a indepdent Kurdistan, if only to appease Iran to ensure their land, however I can see a kingdom ruled by a Kurdish monarchy that calls itself something different.

Yep, this is a very different Middle East compared to what we got in OTL. This can all more or less be attributed to a different defeat of the Ottoman Empire ITTL and the absence of something akin to the Sykes-Picot Agreement to capitulate Arab lands to the French.Syria looks far larger here with the Turkish and Iraq bits added, over all the middle east looks quite different.

I primarily went to Wikipedia. I had a very limited understanding of early 20th Century Chinese history prior to writing MMH, so I didn't need to do much digging in order to find more information. Wikipedia also has a handful of maps of the various Chinese warlord states of the early 20th Century, which I found particularly useful.By the way, you mentioned your plans for China changing a lot as you read more about the early warlord era, I would like to know what places you went to get this useful information?

Heh, that's more or less what Stalin looks like, and I even imagined him needing an eyepatch. I was originally going to make my own version of what Stalin looks like after his plane crash, but my photo-editing skills aren't good enough to pull that off.Someone had already made a reference to the gamerwelt of TNO's "African Devastation" superevent. On topic of TNO, that mod has an easter egg in the files:

It's called "Punished Stalin". The last update did mention he got badly scarred from a plane crash after evacuating Berlin, and lost some of his tactical acumen. I wonder if he looks something like this?

The Workers' Commonwealth has been taking steps to centralize its military apparatus as of recently, which for the time being should prevent England from disintegrating into municipal warlordism, however, as you point out, the local militias pose a potential risk going forward. More importantly in the eyes of London for the time being, local militias are a bit of a logistical mess in a conventional war, especially now that the Commonwealth is fighting exclusively on the Western Front as opposed to engaging in a guerrilla conflict in Great Britain itself. This has proven to be a bit of an ethical issue within the WC, given that the British Revolution was very much a grassroots effort and many government officials are cautious about sacrificing this decentralized and more democratic structure for the armed forces in favor of something more top-down.Speaking of devastation, people have suggested that the late stage of the war gets rather warlord-y as the broken countries have trouble controlling their territory. The Worker's Commonwealth might have bigger problems with this than other, since the Communal Defense Act allowed regions to form their own independent militias, supplied with arms by the government. This was an effective emergency measure in the face of invasion, but in the long term if the central government loses its legitimacy and/or the national army gets utterly gutted, than unhappy towns could really easily rebel flout the government's authority.

So basically the territory that Poland annexed after WWII in OTL? That actually makes quite a bit of sense the more I think about, especially given that East Prussia is far enough away from the Eastern Front for the Russians to be comfortable with reorganizing the territory. I may or may not toy around with the region at some point.EDIT: ALso, you mentioned that East Prussia was a bit of German territory not slaated to become part of Poland before the battle of berlin went sideways, but I think it would have made sense for Poland to try claiming the southern half of East Prussia, where the Masurian slavs are a large chunk of the population.

What is the state of Morrocan-US relations?The Moroccan bureaucracy currently consists of members of the Alaouite Dynasty and leaders of secessionist rebellions from colonial times, including Abd el-Krim. As for its armed forces, Morocco doesn't have a very large army upon independence and isn't particularly interested in entering the Great War anytime soon, however, territorial disputes with Spain have incentivized a military buildup in the months since the expulsion of the French. Morocco and the French Commune obviously have significant ideological differences that prevent them from being particularly close, but neither nation is interested in going to war with the other, so they maintain cordial relations with each other for the time being.

This is really well written.

My only problem is that you are making real life figures seem way too competent or incompetent.

My only problem is that you are making real life figures seem way too competent or incompetent.

Could you please give some examples of the figures who's competency you think is badly off the mark?This is really well written.

My only problem is that you are making real life figures seem way too competent or incompetent.

The entire german military junta, Stalin, Trotsky, Roosevelt, Hiram Johnson, The Frebch generals, The Brazilian military Junta, Lenin himself, the Japanese Emperor, the European Holdings in Africa and everyone else.Could you please give some examples of the figures who's competency you think is badly off the mark?

They seem to simply easily have all the information and be able to make logical decisions that are good in defiance of nationalistic pride. That is just simply not how things were back then and today since it is so easy to get caught up in bias.

Hello everyone, as you may have noticed, the latest chapter has yet to be posted. This is largely because I started a new job in early July, which has meant that I have waaay less free time than I used to, not to mention that my shift is typically at the time I used to write. Chapter Thirteen should therefore hopefully be out sometime in September, but if something else comes up, I will be sure to keep everyone here posted.

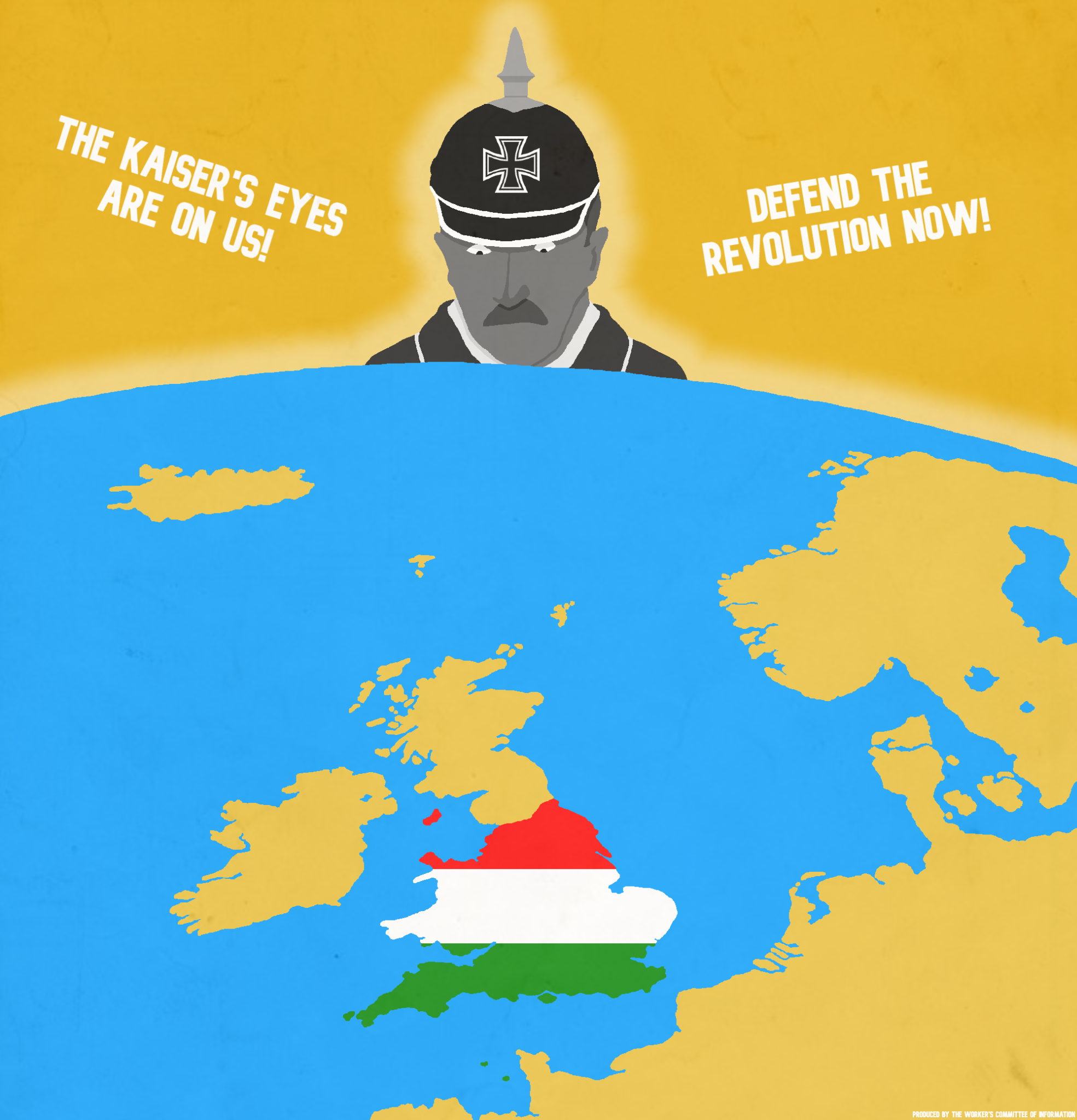

In the meantime, while I'm working on the next chapter of Man-Made Hell, I do have some artwork pieces I've made over the summer for the TL to serve as an interlude for now. If you're interested in more work like this as interludes in the future, please let me know!

First off, here's a poster I made for the TL as a whole, complete with some images of events ITTL and some previous graphics.

Here's a propaganda poster created by the Workers' Commonwealth ITTL shortly after the beginning of Phase Three in November 1929. As you can see, Kaiser August Wilhelm I has become the "main antagonist" of anti-Central Powers propaganda throughout the Third International, similar to Hitler in the bulk of WWII Allied propaganda from OTL.

In the meantime, while I'm working on the next chapter of Man-Made Hell, I do have some artwork pieces I've made over the summer for the TL to serve as an interlude for now. If you're interested in more work like this as interludes in the future, please let me know!

First off, here's a poster I made for the TL as a whole, complete with some images of events ITTL and some previous graphics.

Here's a propaganda poster created by the Workers' Commonwealth ITTL shortly after the beginning of Phase Three in November 1929. As you can see, Kaiser August Wilhelm I has become the "main antagonist" of anti-Central Powers propaganda throughout the Third International, similar to Hitler in the bulk of WWII Allied propaganda from OTL.

This final graphic is supposed to be a poster for the Russian Soviet Republic reminiscent of the original "World of Kaiserreich" posters, which is something I've always wanted to replicate the style of for my TLs. I'm still new to these kinds of posters, but I'm nonetheless pretty satisfied with the result for this one.

Last edited:

Work's a bitch huh? Hope you can find a new writing time to replace what your shift took. Also dang, those posters are really good! You've definitely got graphic design skills. What tools do you use to make them?

Yeah, work's been a real pain. The good news is that the start of the school year means that I won't be working as many days, which should hopefully give me more time to write.Work's a bitch huh? Hope you can find a new writing time to replace what your shift took.

Thanks, I'm happy to hear that they came out well! I mostly use Pixlr, which is fortunately a free website that anyone can use without making an account. It's especially really handy for WorldA maps.Also dang, those posters are really good! You've definitely got graphic design skills. What tools do you use to make them?

Best of luck! Nice art! Thank you for your hard work.snip

Chapter Thirteen: A Bold New World

Chapter XIII: A Bold New World

“The Battle of Berlin and subsequent engagements between the belligerent powers of Europe have made it clear that the Great War is far from over, and the people of the Old World are condemned to suffer many more years of the greatest tragedy of modern history.”

-Excerpt from United States President Hiram Johnson’s 1929 farewell address, urging for continued American neutrality in the Great War.

German soldiers fighting near Frankfurt an der Oder, circa November 1929.

Swiecko, Russian-occupied Germany, circa April 1930:

It was a bitter spring day. Snow was still melting from the preceding harsh winter, turning craters forged by aerial bombardment into grimy puddles of mud. The silence at Nowak’s Bar, a little establishment on the eastern outskirts of the Swiecko village (and therefore relatively safe from the LK bombing campaigns that so often ravaged countless settlements along the Oder River), was occasionally interrupted by the echoes of bombs further west. A few of the bar’s customers had their own discussions within enclosed circles of peers, however, the typical excitement that could be found in such establishments back in Moscow was nonexistent this far out west, this close to the Great War. No one came to the Oder to have a good time. You came to this dreary warzone to fight the Heilsreich.

Marina Raskova was one of the people who had come out west to fight this fascist terror. Having just recently turned eighteen, thus making her old enough to join the Red Army, Marina had dreamed of becoming an opera singer as a child. Of course, the achievement of the World Revolution through the decisive defeat of the fascist barbarians that sought to lay ruin to the states of the Third International was the duty of all Russians. Dreams could wait for a post-war world. For Marina, the Great War was also personal. Her father had joined the Red Army as the first Soviet forces marched west into the Principality of Belarus back in 1923 and was gunned down by Alfred Hugenberg’s lackeys at the First Battle of Vawkavysk. When the news of her father’s death on the Eastern Front reached the eleven year-old Marina, she became determined to continue her father’s patriotic fight for the Russian Soviet Republic as soon as she possibly could, eventually abandoning her dream for singing in favor of joining the second generation of Soviet soldiers fighting in the seemingly endless Great War.

Now, as Marina, now a newly-recruited private preparing for the first time she would ever experience combat, sat in Nowak’s Bar alongside her comrades that made up her squad, the fear of the looming chaos of the Eastern Front that was banished from bootcamps and recruitment centers began to creep over her. This cheap little bar, a locale that her lance sergeant had visited after fighting in the Battle of Berlin, was very likely the last civilian establishment that Marina would visit before arriving on the frontlines. There was no turning back, and the thought of marching towards a young death was chilling.

“I’m sure we’ll be returning home in no time,” Alexei, a fellow private sitting next to Marina who noticed the unease emerging over her, insisted. “I heard that some parts of Berlin are still toxic hellscapes. How much more of a fight could a country that can’t even breathe its capital’s own air have left in it?”

“That’s exactly my worry,” Marina replied. “Germans can’t even breathe the air in their own capital, yet they keep on fighting. What does that tell you about how far they are willing to go before they give up?”

Alexei remained silent, struggling to maintain a crooked smile that attempted to portray a confidence that his tired eyes proved was little more than a lie he told to himself.

“It tells me,” Marina continued, “that they won’t give up until either they’re all dead and their country is burned to a crisp or we’re all dead and Moscow is wiped off the map.”

Alexei let out a faint laugh, yet another lie.

“Comrade, you’re quite the optimist,” he sarcastically remarked.

“I’m just a realist. When I signed up to fight in the war, I knew I wouldn’t return to civilian life anytime soon. In two years, people who were born at the beginning of this nightmare will be fighting in it. We’ve already lost an entire generation of comrades to the imperialists and, as much as I hate to admit it, we’ll probably lose another. But it’s worth it, Alexei. It’s a sacrifice worth making. If our generation doesn’t fight, all generations that succeed us will be slaves of the Heilsreich.”

“A bit grim, but I guess you’re right, Marina. There can’t be a World Revolution without comrades like us willing to do the messy work. Still, you have to admit that it’s nice to have something more than not being Auggie’s slave to look forward to when this is all over, right? Do you still want to become a singer?”

“I suppose so.”

“See, I don’t know about you, but I think looking forward to that kind of stuff is a much better motivator than abstract idealism. It’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Marina smiled at her comrade and raised her whiskey to a toast.

“In that case, to the light at the end of the tunnel.”

Alexei laughed and lifted his own whiskey.

“To the light at the end of the tunnel, and to the end of this ugly war.”

Before either of the young soldiers could drink their beverages, an explosive sound was unleashed not far from the Nowak’s Bar, shattering all of its windows.

BOOM.

Everyone in the bar froze in complete panic. Alexei’s facade of confident fearlessness in the face of the bloodiest conflict in human history was shattered with the windows. A German bomber must’ve flown off course.

“Comrades, that’s our que,” announced Lance Sergeant Khruschev. “It’s off to the Oder.”

As Marina and Alexei left Nowak’s Bar, they stopped with the rest of their squad, staring with horror at what lay in front of them. Towers of smoke rose from Swiecko as Russian military vehicles rushed towards the village, gunshots ringing from its decimated streets.

The Heilsreich had crossed the Oder River.

A few seconds of shock passed for everyone present before Lance Sergeant Khruschev gave his order.

“Is this squad blind!? You are all soldiers! The enemy is in front of you! Fight for the Motherland!”

The New Order

“Following the tragic death of Alfred Hugenberg, I graciously accept the nomination brought forth by the delegates of the German Fatherland Party and shall assume the position of fuhrer of the German Heilsreich.”

-Kaiser August Wilhelm officially announcing his assumption of the fuhrership to the Reichstag, circa June 1929.

Feldgendarmerie forces patrolling Hamburg, circa May 1929.

On May 21st, 1929, Fuhrer Alfred Hugenberg of the German Heilsreich unexpectedly died. After having ruled Germany with an iron fist for over six years, one of the most important men in 20th Century history was gone, leaving behind a totalitarian regime with an uncertain future. Details surrounding Hugenberg’s death at the age of sixty-three were murky (an autopsy to uncover the cause of death was never conducted, nor did any of the most prominent individuals within the German elite, such as August Wilhelm, Erich Ludendorff, or Kurt von Schleicher, push for an investigation into the circumstances surrounding Hugenberg’s demise), but this was to be expected from the German apparatus of state by this point, which was becoming increasingly secretive as the DVP tightened its already firm grip on media. National newspapers simply reported on May 26th that Alfred Hugenberg had died of a heart attack five days prior whilst being driven back from a dinner with the Kaiser at the Royal Palace.

Unbeknownst to those outside of the tightly closed circles of the DVP elite, Hugenberg had not, in fact, died of a heart attack. He had been killed by Kaiser August Wilhelm I, a man who was in many ways his pupil, over a cyanide-infected glass of wine during a fateful dinner in Berlin. The execution of Hugenberg had been planned almost immediately in the aftermath of the battle for the German capital city, with the ideological differences between the Fuhrer and the Kaiser finally coming to a head as the success of August’s Operation Odoacer made the reigning monarch substantially more popular than the head of government amongst Germany’s military circles. August Wilhelm was viewed as more competent, more well-tuned to the machinations of wartime, and more dedicated to the complete repulsion to anything less than the unconditional annihilation of Germany’s enemies than Hugenberg had ever been.

Therefore, the pawns in the delicate game of chess between August and Hugenberg began to move into position for a checkmate as the first government officials returned to the ruined city of Berlin circa late March 1929. The Kaiser first contacted General Erich Ludendorff, the highest ranking officer in the Imperial German Army and a man whom he regarded as a relatively close friend (at least as close as anyone could be to someone as machiavellian as August Wilhelm), to ask him about his preference in terms of leadership between the Kaiser himself and Hugenberg, to which Ludendorff made it clear that he was firmly behind the friend that he had developed Operation Odoacer with. From here, once knowing that Ludendorff was to be trusted after weeks of correspondence on the subject of dispute within Germany’s executive branch, August suggested the secret assassination of the Fuhrer and subsequent election of himself to succeed his victim to the infamous general. Ludendorff agreed to collude with the Kaiser, providing support in the form of lending trusted soldiers to patrol the Royal Palace as aides to August’s plot during the murder itself, covering up loose ends via the utilization of the armed forces, and publicly endorsing August as the successor to Hugenberg in the aftermath.

Erich Ludendorff and his personally closest lackeys made for an invaluable asset in August Wilhelm’s scheme, however, one individual who was absolutely essential to get away with the murder of the Fuhrer was Gruppenfuhrer-FG Kurt von Schleicher, the leader of the German Heilsreich’s military police. Arguably the single most pivotal enforcer of the DVP’s totalitarian reign in the earliest days of the Heilsreich, Schleicher controlled everything relating to domestic law enforcement within Germany, monitoring each and every civilian regardless of their rank in the apparatus of state, purging any perceived enemy of the state without hesitation, and pulling the strings of the criminal justice system when necessary. In the context of August’s scheme, Schleicher was needed to ensure that no investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of the Fuhrer would be conducted at any level of the German government. The allegiance of Schleicher with regards to the rivalry between August and Hugenberg was unknown, but the Kaiser and Ludendorff nonetheless had to take their chances.

Given that Kurt von Schleicher was a former member of the Supreme Army Command’s General Staff and a descendant of the Prussian nobility, August and Ludendorff decided that it was best for the latter to contact him via private messages. The Supreme Army Commander would initially enquire the Gruppenfuhrer’s opinions with regards to the dispute between the Kaiser and the Fuhrer, to which Schleicher would reply that, while he had once strongly supported Hugenberg, had come to view the man as woefully incompetent during the Battle of Berlin and came around to admiring August Wilhelm’s advocacy for strengthening the power of the nobility. Over the span of the next few days, Ludendorff gradually shifted his correspondence with Schleicher towards the territory of deposing the Fuhrer. The Gruppenfuhrer was unsurprisingly reluctant at first, however, he ultimately endorsed the plan and agreed to cover up the murder of Alfred Hugenberg to the best of his ability.

And so, once August had arranged all of his pawns, the time had come to make his move. On May 21st, 1929, the corpse of Alfred Hugenberg was rushed from the Royal Palace to a hospital through the shattered city of Berlin by a German soldier directly employed for the job by Erich Ludendorff, where he was declared dead. No autopsy was conducted at the indirect behest of Kurt von Schleicher and Hugenberg’s personal chauffeur, who had driven the Fuhrer to the Royal Palace but had been ordered by the building’s soldiers to wait within the building and not drive Hugenberg home that fateful day, was killed by what authorities claimed was an unaccounted Russian mind left unaccounted for following the Battle of Berlin but was actually an act of terror by the FG. No one dared question the circumstances surrounding the death of Alfred Hugenberg, and on May 28th, no more than two days since the death of the Fuhrer was revealed, General Erich Ludendorff publicly declared his support for Kaiser August Wilhelm I as the successor to Hugenberg, a sentiment that was shared with state-managed press in the coming days by Kurt von Schleicher and various officials of both the DVP and armed forces alike.

In accordance with the constitution of the German Heilsreich, the fuhrership was to be decided by a vote in the Reichstag, and it soon became clear that August Wilhelm was the clear favorite. The election of Hugenberg’s successor occurred in a closed session of the Reichstag on June 2nd, 1929, and while this vote was by no means unanimous, the outcome was inevitable. Under pressure from the German elite, including those who were now the nation’s most powerful men in the absence of Hugenberg, Kaiser August Wilhelm would be elected to the fuhrership and subsequently assumed power on June 3rd, thus becoming both the head of state and head of government of the German Heilsreich. In other words, August was to become an unrivaled autocrat. The Kaiser had gotten away with murder, and in the span of less than two weeks, had effectively brought Germany back to the days of absolute monarchism. A man drunk on a wicked elixir of power, ambition, and fascism now controlled one of the largest armies on Earth, determined to bring hell down upon each and every one of his enemies.

The reign of the greatest villain in the history of the 20th Century, the Kaiser-Fuhrer, had begun.

Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm of the German Heilsreich following his election by the Reichstag, circa June 1929.

Now that August reigned as the undisputed tyrant of the dystopian police state that he and the man he had killed forged, it was time for his plans to be put into motion. On June 11th, 1929, the Kaiser-Fuhrer would give a speech to the entire Reichstag in which he narrated “The Divine Right and Fascism”, his personal manifesto that outlined the far-right ideology of Germany’s new autocrat. This manifesto argued in favor of the restoration of the divine right of kings in the context of fascism, effectively claiming that a monarch was the preordained ruler of a nation, thus meaning that the total dedication of an individual to a nation demanded by fascism extended to total dedication of an individual to said nation’s reigning monarch. In other words, August Wilhelm insisted that he was the physical embodiment of the German nation and that the bondage of people within a fascist society to their nation was therefore bondage to his whim. “The Divine Right and Fascism” further synthesized the ideology of the fascist DVP with pre-Enlightenment ideals by arguing that, in the same fashion that traditional fascism argued that there were superior ethnic groups, the Junker class was superior to masses, therefore calling for the transformation of Germany’s noble class into the vanguard of the Kaiser-Fuhrer’s absolute rule.

The ideals of “The Divine Right and Fascism”, which later became recognized as a sect of fascism deemed “national absolutism”, was reactionary even by the standards of traditional fascists. August Wilhelm was more or less advocating for completely undoing the progress of the Age of Enlightenment in favor of an ultranationalist totalitarian regime in which all power would be extended from his throne. Under the jackboot of national absolutism, the Kaiser-Fuhrer would become the German state. Some Reichstag MPs were concerned by the contents of “The Divine Right and Fascism”, however, it was too late to select a new Fuhrer and the position was a lifetime appointment. The manifesto was officially adopted as the DVP’s ideological platform a day after the Kaiser-Fuhrer gave his speech, thus obligating the party to implement the deranged fantasy of August Wilhelm I. There was no turning back, thus dooming the German Heilsreich to the horrors of national absolutist rule.

The first step towards implementing national absolutism would be taken on June 17th, 1929, when an amendment to the German constitution was made that handed over all executive power away from the fuhrership and to the Kaiser's office. Given that August held both positions, this was little more than an symbolic formality intended to shape the structure of the German apparatus of state after his death, however, it nonetheless marked the beginning of the Heilsreich’s slide into absolute monarchism. Three days later, the Reichstag narrowly approved a much more consequential amendment, which gave the Kaiser-Fuhrer to unilaterally conduct the responsibilities of the Reichstag, including single-handedly passing and repealing laws and amending the German constitution itself. The Reichstag therefore became little more than an advisory board and was no longer necessary to implement the vision of August Wilhelm, the first absolute monarch since the Russian Empire.

After absorbing such a vast quantity of political power, the Kaiser-Fuhrer sought to consolidate his grip on power by directing the FG to carry out a purge of potential opponents. Kurt von Schleicher would not, however, lead this round of purges. Despite having been an essential pawn in the murder of Alfred Hugenberg, Schleicher’s initial reluctance to participate in August’s plot and his historical preference for political power to be shared between the German monarchy and military elite made the Gruppenfuhrer a liability in the eyes of August Wilhelm. He was therefore removed from a position he had held since the inception of the Heilsreich and replaced by General Gerd von Rundstedt, a Junker monarchist who opted to remain uninvolved in politics and unquestioningly loyal to the German government, regardless of the regime type. In the private words of August, Rundstedt was “a lapdog who follows the orders of his master without hesitation”, which made him perfect for leading an organization whose loyalty was paramount for the secure implementation of national absolutism.

Gruppenfuhrer-FG Gerd von Rundstedt.

Upon being appointed to the leadership of the FG, Rundstedt immediately set out to enforce the Kaiser-Fuhrer’s bidding. Operation Hornet, the secretive mass purge of political opposition, would be executed throughout July 1929 in a series of private executions reminiscent of the Night of the Long Knives from six years prior. One by one, high-ranking German officials, including, ironically enough, Kurt von Schleicher himself, would go missing in the night. The bulk of Operation Hornet’s victims were Hugenberg loyalists, opponents of the national absolutist ideology (all Reichstag MPs who voted against August’s constitutional amendments were purged), and non-Junkers in both the German bureaucracy and private sector. While the assassinations of Operation Horsefly had been reported as murders and an assortment of accidents in state-owned media, the bloodshed of Operation Hornet was barred from being referenced to the public at all. For the most important victims, there was at most a mention in the daily obituary without any cause of death listed. The names of many more victims were eerily retroactively redacted from documents in an attempt to condemn those who stood in the way of national absolutism to the dustbin of history.

Operation Hornet was winding down by the start of August 1929, thus allowing August Wilhelm to take his next steps towards implementing national absolutism. The Junker Rights Act was put into effect on August 1st, thus stripping non-nobles of holding public office at any level within the Heilsreich. August Wilhelm’s push for restoring German aristocratic power only got more extreme from this point, with the Land Act of August 5th barring non-nobles from owning property and redistributing the assets of numerous non-noble businesses to both Junker magnates and the German armed forces itself. The Kaiser-Fuhrer ratified his first unilateral constitutional amendment on August 10th, which abolished Germany’s states in favor of unitary direct rule from Berlin. This amendment, of course, stripped the rulers of the internal German kingdoms of their domains, however, Operation Hornet had already purged political opponents on the local level, therefore ensuring a relatively smooth transition to direct rule, and those who did cause a fuss after losing their kingdoms would find themselves confronted by FG officers sooner or later.

In the place of the historical German administrative divisions, the Heilsreich was divided into a collection of territories leased by the Kaiser-Fuhrer to nobles, called fiefs in reference to the historical feudalistic property system, which would carry out the functions of regional administration not addressed on a national level. Given that Germany as a whole was perceived as the property of August Wilhelm, his throne could override the affairs of administration at all levels and the fiefs themselves were viewed as leases of land that could be dissolved, redesigned, or have their leadership replaced at any given time. Aside from total obedience to the demands of the Kaiser-Fuhrer, however, the lords of the Heilsreich’s fiefs were the undisputed rulers of their domains. The first lords of the fiefs of the German Heilsreich were an assortment of nobles, military officers, and Junker business magnates rewarded for their loyalty to August himself. Fiefs that bordered the Great War’s frontlines were ruled by the commanding officers of said frontlines, with Erich Ludendorff being appointed to reign over the Margraviate of Brandenburg as an example.

The fiefs of the Heilsreich formed by the Kaiser-Fuhrer (on this level, fiefs were awarded the title of “margaviate”) would in turn subdivide themselves into internal fiefs, oftentimes localizing administration down to the municipal level, thus restoring a system that bore a striking resemblance to the feudal monarchies of Medieval Europe within the span of a few months. Through the reforms of August Wilhelm, the German Heilsreich had burned away all progress made during the Age of Enlightenment, leaving behind a bizarre fusion of fascism, absolute monarchism, and classical feudalism in its place. Whatever little notion of human rights existed within the already totalitarian regime of Alfred Hugenberg was nonexistent under the iron fist of August Wilhelm I as the German masses were directed to work in the name of the war effort by either their fiefs or the powerful Junker corporations that closely collaborated with the German political and military elite.

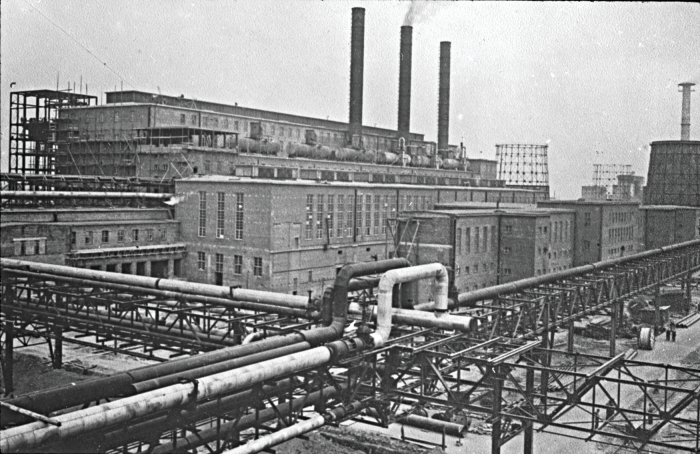

Factory owned by the Imperial German Army located in Frankfurt, circa November 1929.

Speaking of Junker corporations, the national absolutist counterrevolution saw the widespread consolidation of private industry into oftentimes monopolistic organizations that integrated themselves into the new political system. Friedrich Krupp AG, the leading producer of artillery since the start of the Great War and the company of the wealthy Krupp family, was one of the largest benefactors of August Wilhelm’s economic consolidation. Krupp was awarded with considerable non-Junker property, thus ceding the already immensely powerful corporation a de facto monopoly over Germany’s steel production industry. This was precisely the intent of August Wilhelm, who sought to transform Friedrich Krupp AG into the loyal managers of the German military-industrial complex, with the power handed to the Krupp family going as far as putting their corporation’s head, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, in control of the Margraviate of Westphalia, which by extension meant that Westphalia was treated like an asset of the Friedrich Krupp AG corporation.

While the German nobility (or at least those who remained loyal to August Wilhelm) accumulated significant power under national absolutism, the average German citizen was turned into little more than a resource of the ruling class to be used in the fight against the Third International. The loss of property for non-Junkers forced the vast majority of the German population into dependency on the rulers of their fiefs for basic needs to be met, and while a history of patronage with regards to socioeconomic power during the Hugenberg administration meant that the transition to national absolutism was less extreme than it would have been had the previous regime been democratic, millions of Germans were nonetheless thrust into unprecedentedly poor socioeconomic conditions. In the Third International, the Heilsreich’s descent into utter madness made for the perfect propaganda opportunity as posters and newsreels depicting “the new serf” proliferated throughout the socialist world, and the fact of the matter was that such propaganda wasn’t too far away from the truth. A total disregard for human rights within Germany allowed for rampant exploitation of the masses by appointed lords and the legalization of indentured servitude under the reign of the Kaiser-Fuhrer allowed for relations akin to serfdom to re-emerge going into the 1930s.

For those who were not ethnically German, conditions were even more abysmal. Such groups had already been stripped of their human rights in accordance with fascist philosophy under the reign of Alfred Hugenberg, having been interned in ghettos segregated from the rest of Germany, where their inhabitants were often conscripted into the German wartime industry. Under the iron fist of August Wilhelm, however, conditions for the victims of the DVP’s disgusting ideology of racial hierarchy managed to get even worse. The enslavement of those who were not ethnically German was legalized by the Subjugation Act of September 22nd, 1929, and under the coordination of the Kaiser-Fuhrer himself, ghettos were depopulated as their inhabitants were shipped off to work in the factories of the German military-industrial complex as slaves, becoming the property of corporate entities, the armed forces, and fiefs alike. In the eyes of the DVP, these millions of victims of the Heilsreich’s reign of terror were subhuman to the German nationality and were to be treated like little more than yet another disposable tool in the brutal war effort of the Central Powers.

It was this nightmare that Kaiser-Fuhrer August Wilhelm I sought to consume all of Europe. As Phase Three began with the withdrawal of the Entente from the Great War and the War of Ideology became the War of Resources, August Wilhelm transformed his domain and all of its people into his very own personal resource dedicated to the conquest of more territory for the Kaiser-Fuhrer to rule over. The man who had waited within the shadows of German politics for almost a decade, was the mastermind behind Erich Ludendorff’s victory at the Battle of Berlin, orchestrated the murder of his mentor, and rose to rule over an empire in his place had finally implemented the dastardly ideals of national absolutism, within the span of a handful of months no less. But the question of how long the national absolutist nightmare would last had yet to be answered, for the Great War still needed to be won.

If the Kaiser-Fuhrer were to accomplish such a task, he required new allies.

The Sick Man

“As the end of my life approaches, I fear that so too shall the Ottoman Caliphate follow suit.”

-Excerpt from the journal of Sultan Mehmed VI of the Ottoman Empire, circa June 1926.

The Hagia Sophia Holy Grand Mosque, circa November 1929.

There was a time when the Ottoman Empire was feared by the entire European continent. Mighty kingdoms were slain by the swords of many sultans, great cities crumbled under Ottoman cannonfire, and the domain of the House of Osman expanded into territory that not even the grandest caliphates of the Golden Age of Islam had reached. Well before the Great War began, however, those days were long gone. Despite various attempts at reform throughout the 19th and early 20th Century, a plethora of factors, including a lack of industrialization, rising regional nationalism, and slow modernization, doomed the Ottoman state to decades of decline as encroaching European nations picked off Constantinople’s holdings. By the time Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand on a fateful summer day, the Ottoman Empire had been expelled from both the Balkans and North Africa, just barely holding onto its territory in Arabia as unrest dominated the political situation in Anatolia. As the armed forces of the European titans lurched at each other’s throats, the Ottoman Empire, colloquially referred to as the “sick man of Europe”, was viewed as a source of new colonial possessions by the Entente rather than a serious threat.

Turkey’s allies within the Central Powers held out well throughout Phase One of the Great War, even coming close to decisive victory over their enemies on various occasions, however, this streak of success did not proliferate down to Anatolia. The Ottoman Empire was more or less single-handedly defeated by Entente forces during Phase One, with the outbreak of the British-supported Arab Revolt in 1916 and the subsequent invasion of Mesopotamia in 1917 spelling the beginning of the end for what had once been one of the most fearsome empires on Earth. The 1921 capitulation of the Turkish state to the Entente and subsequent ratification of the Treaty of Aleppo turned the Ottoman Empire to an empire in name only as the vast majority of Turkish possessions outside of Anatolia were ceded over to a plethora of British puppet regimes, which became the new sources of fuel for the Entente war effort.

The Treaty of Aleppo was, for all intents and purposes, the de facto death knell of the Ottoman Empire. The Entente’s engagements in the Balkans against Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria had prevented a total destruction of the empire by keeping the House of Osman’s grip on Anatolia intact, however, Turkey had been relegated to an irrelevant status in European politics and was completely humiliated in the process. The bulk of blame for this embarrassing defeat fell upon the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a Turkish nationalist and pro-modernization political organization that had ruled over the Ottoman Empire via a de facto one party regime since the 1913 Ottom coup d’etat. Much of the CUP’s leadership would flee into exile following the ratification of the Treaty of Aleppo as the organization’s position of power became increasingly untenable, and the CUP voted to dissolve itself during its final party congress on November 5th, 1921, thus resulting in the collapse of one party rule and the establishment of an unstable multiparty parliamentary democracy within the Ottoman Empire.

Held on January 9th, the 1922 Ottoman general would see the reformed Freedom and Accord Party (FAP), which advocated for liberalism, decentralization, and the rights of minorities, form a government via a coalition with a number of independent MPs who aligned with the party’s ideological tenets. FAP member Ali Kemal was elected Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, becoming the first Ottoman head of government to not align with the CUP in almost a decade. As grand vizier, Kemal would spend the earliest days of his administration prosecuting the former leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress that remained in Turkey for orchestrating the infamous Armenian genocide, the atrocious systemic murder of approximately one million ethnic Armenians from 1915 to 1917. Various CUP political and military officials were put on trial for their involvement in the systemic ethnic cleansing of Armenians, and many of those found guilty for massacres, including former Grand Vizier Said Halim Pasha, were subsequently hanged.

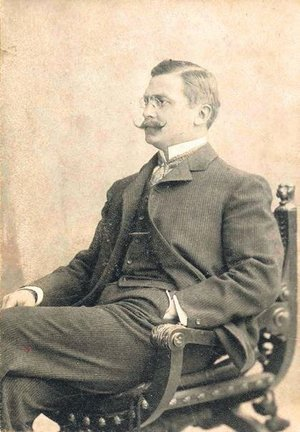

Grand Vizier Ali Kemal of the Ottoman Empire.

Of course, the ideals of the Committee of Union and Progress that had dominated Ottoman politics for years, wouldn’t simply just die off with the organization’s leadership. Many ex-CUP officials formed the Turanic Renewal Party (TRP), a right-wing movement that advocated for pan-Turkism, ethnic nationalism, and a centralized state, thus making the TRP a very blatant

successor to the ideology of the CUP. The Turanics managed to secure the second greatest number of seats in the 1922 general election, thus forming the opposition coalition against Grand Vizier Kemal. Perhaps predictably given the origins of the party, the TRP was highly critical of the prosecution of CUP officials for their involvement in the Armenian genocide, with the leadership of the TRP downplaying the extent of the genocide and arguing that Ali Kemal’s trials of officials the TRP deemed to be great public servants was tantamount to treason against the Turkish nation.

The Turanics could complain about the prosecution of the CUP all they wanted, however, at the end of the day, the public wanted to blame someone for the crushing defeat of the Ottoman Empire and the trials of the leadership that had held power during the Great War seemed to quench this demand for the time being, thus making the actions of the Kemal administration popular for the time being. But finding someone to blame for defeat in the Great War was not enough for the reign of the Freedom and Accord Party to succeed. The Kemal administration would need to implement policies to actually recover what remained of the Ottoman Empire, and it was here that the FAP-led coalition fell short. The Kemal administration sought to maintain the general policy of liberal free trade that had been implemented throughout much of the 19th Century rather than focus on the desperately-needed buildup of domestic industry. Turkey’s role in the economy of the Great War as a neutral state was that of an exporter of primarily agricultural goods by merchants to both the Central Powers and Entente, although steel and cheap armaments became also became significant exports from the Ottoman Empire, with many belligerents of the Great War (primarily the British Empire) setting up shop within Anatolia to profit from industries made particularly lucrative during wartime.

The bulk of industrial products used within the Ottoman Empire during the Kemal administration were imported from neutral industrialized states, primarily the United States of America and the Empire of Japan, thus preventing the development of a domestic manufacturing center after a period of deindustrialization during the 19th Century. A lack of domestic industry, combined with little regulation on the private sector, made economic recovery from the Great War a difficult feat for Turkey to accomplish and much of the Turkish working class was stuck in a low standard of living. Stagnant economic growth under the reign of Ali Kemal gave way to the rise of opposition parties on both the left and right. In the case of the former, the Turkish Communist Party (TKP), which had been founded by Mustafa Subhi in 1920, grew into a big tent party for the Ottoman Empire’s far-left, attracting disgruntled working class voters who saw the recent success of socialist revolutions throughout the great powers of the Entente as evidence that the installation of a similar radical economic structure within Turkey could solve the nation’s socio-economic woes. By amassing a coalition of various flavors of radical socialism, the TKP managed to perform decently on the local level and won support within the emerging Turkish labor movement, however, the party nonetheless faced accusations of being little more than a proxy of the Russian Soviet Republic, and Subhi’s historical participation within the Bolshevik Party meant that such accusations weren’t completely unfounded.

To their right, the Freedom and Accord Party continued to be flanked by the Turanic Renewal Party, which found support from the historical Ottoman establishment, many wealthy Turks, and even a notable chunk of the working class, which was attracted by the TRP’s populist rhetoric in a similar fashion to the popular support found by the fascist organizations of Europe. Throughout the mid-1920s, the Turanics continued to espouse nationalist ideals, advocating for centralization, protectionism and a mass remilitarization campaign as solutions to Turkey’s economic woes. The TRP blamed the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the Great War on Sultan Mehmed VI and minority groups, hoping to depict Kemal’s prosecution of CUP leadership as an unjust campaign conducted against patriotic Turks for little more than political gain, and this opposition against the ruling Ottoman monarchy in particular turned the TRP into an advocate for varying degrees of authoritarian republicanism. Under the leadership of Ahmet Ferit Tek, the Turanics were more or less a continuation of the policies of the CUP and served as a big tent organization for the Ottoman right-wing, however, as fascism reigned over the Central Powers, so too did a current of fascist ideals forged from Turkish ethnonationalism emerge within the ranks of the TRP.

By the time the 1927 Ottoman general election rolled around on January 9th of said year, the FAP, TRP, and TKP had emerged as the dominant parties in Turkish politics, although the absence of any general election over the past five years had allowed for the FAP-led coalition consisting of the party itself and likeminded independents to hold onto a majority of seats within the Chamber of Deputies despite only being supported by approximately a third of the population. It was, therefore, a predictable conclusion that Ali Kemal’s coalition would be ousted from its majority, and surely enough the 1927 general election saw the relatively even split of the Chamber of Deputies between the three major parties, therefore meaning that the FAP would now have to form a coalition with one of the two other major parties in order to remain in power. The Freedom and Accord Party nonetheless maintained a slim plurality within the Chamber of Deputies and enjoyed support from a majority of members of the Senate of the Ottoman Empire, which put the party in the strongest bargaining position.

The Turkish Communist Party was viewed as unacceptably extreme by the FAP, which meant that Grand Vizier Kemal would have to enter into negotiations to form a coalition with the Turanic Renewal Party if he sought to hold onto power. Despite the historical rivalry of the two parties over the past five years, the leadership of the FAP viewed a government with the TRP as the lesser of two evils and the leadership of the TRP accepted that forming a governing coalition served as a great opportunity to advance much of the party’s platform. Therefore, after numerous days of negotiations, the FAP and TRP announced that they had reached a coalition agreement on January 14th, 1927, with Ali Kemal remaining at the helm of the coalition government as grand vizier despite vocal opposition to such a prospect from the far-right wing of the Turanics. In the process of forming the FAP-TRP alliance, both parties made significant concessions in order to appease each other, as the FAP agreed to support military programs and an end to the pursuit of demilitarization whilst the TRP agreed to drop opposition to the monarchy, back laissez-faire economic legislation supported by their coalition partners, and not advance ethnonationalist policies through the Chamber of Deputies.

The FAP-TRP coalition was, perhaps understandably, controversial even amongst its own membership, much of which viewed the alliance as a capitulation on key principles of their parties. There was an unspoken recognition within Constantinople that the coalition was little more than a caretaker government, one that was doomed to collapse the very second one of its participant parties either could not reconcile with the policies of its partner or saw an opportunity to abandon the coalition in favor of unilateral partisan governance of the Ottoman Empire. The question, therefore, was not if the coalition would collapse, but rather when the coalition would collapse. Nonetheless, the leadership of both the FAP and TRP were determined to pass some legislation through their alliance, especially as the national unemployment rate continued to rise. The Defense Development Act, which moderately increased funding for the armed forces and invested in the mechanization of the Ottoman Army, was the first bill passed by the FAP-TRP coalition in accordance with the alliance’s agreement to support militarization programs, being put into effect on February 1st, 1927. Despite being criticized by the TKP opposition and a handful of more left-leaning FAP members of the Chamber of Deputies, the Defense Development Act was generally popular amongst the public, in large part due to the Turanics portraying the jobs created by mechanization programs as the beginning of a solution to unemployment.

The early success of the coalition soon proved to be short-lived, regardless of the popularity of the Defense Development Act. Months passed without the ratification of any significant legislation, and the Defense Development Act itself soon proved to be far from sufficient in terms of reducing unemployment. Neither governing party was able to advance anything even barely ambitious thanks to opposition from its coalition partner, thus resulting in the preservation of an unstable status quo where the only notable change was the occasional slight increase in military funding. All the while, the Ottoman Empire’s status as a neutral supplier of arms to both the Entente and Central Powers was thrown into doubt as the rapidly industrializing Second Empire of Brazil was increasingly capable of arming the vast majority of the Entente’s war effort whereas the Central Powers seemed to be living on borrowed time for the moment. Ironically enough, as the Ottoman economy became increasingly dependant on selling weapons to the Central Powers as a consequence of a policy of neutral free trade pursued by the Freedom and Accord Party, support for aligning Turkey with the Central Powers yet again, and by extension support for the far-right wing of the Turanics, grew amongst the Turkish populace.

As the dusk of 1927 approached, cracks within the FAP-TRP coalition were already beginning to emerge. The Kemal administration was clearly incapable of passing much in terms of meaningful legislation whilst in a coalition with a rival party, the bases of both the FAP and TRP grew increasingly disgruntled with the inability of their parties to advance pet issues that their partner opposed, and all the while unemployment remained high. This culminated in an internal power struggle within the Turanic Renewal Party brought on by the far-right wing of the party believing that the more moderate wing led by Ahmet Ferit Tek, the leader of the TRP within the Chamber of Deputies, was unwilling to advance the platform of their own organization. Former General Nuri Killigil, a veteran of the Arab Revolt-turned wealthy weapons manufacturer who also just so happened to serve within the Chamber of Deputies, led the far-right backlash against Tek, arguing that withdrawal from the coalition government and no compromise on the Turanic platform was paramount. Surely enough, Killigil managed to emerge victorious in a leadership challenge against Ahmet Ferit Tek, and would leave the FAP-TRP coalition on December 2nd, 1927, only two days after assuming control of the TRP.

Without the confidence of a majority of the Chamber of Deputies, Ali Kemal was left with a minority government that lacked the support necessary to effectively administer the Ottoman Empire. With the knives of the Freedom and Accord Party’s legislative rivals turning on a vulnerable ministry, a vote of no confidence was seemingly inevitable, and surely enough, such a motion was introduced by the Turanic Renewal Party on December 4th, successfully passing through the Chamber of Deputies thanks to support from both the TRP and TKP. The young Sultan Mehmed VII, who was no more than fifteen years of age when the vote of no confidence successfully passed and had only assumed power a year prior when his father passed away, lacked the political experience necessary to request the resignation of Kemal’s minority government (not to mention that the sultanate as an institution continued to decline in popularity and Mehmed’s advisors argued that staying out of the spotlight was the best course of action for the time being), however, the grand vizier and his cabinet took it upon themselves to resign on December 5th while a snap election was scheduled for December 18th. In the meantime, the FAP would continue to govern via a minority, with Riza Tevfik Bey, the Kemal administration’s former Minister of Education, being elected grand vizier.

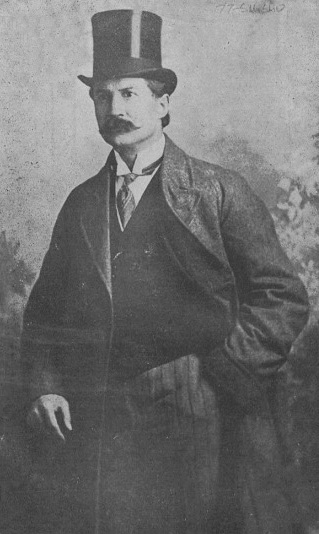

Grand Vizier Riza Tevfik Bey of the Ottoman Empire.

To make the political quagmire Turkey found itself in even more chaotic, Nuri Killigil soon took it upon himself to purge the moderate wing of the TRP from the party’s leadership almost immediately after assuming power, and on December 8th, 1927, the TRP officially announced the installation of a fascist republican regime as a core pillar of the party’s platform, with such a change of course being brought upon by Killigil and his fellow reactionaries that now made up the Turanic leadership. For the 1927 snap election, the TRP was to campaign on the notion that the Ottoman Empire’s experiment with liberalism had failed and the solution was no less than the replacement of the constitutional monarchy with a fascist stratocracy dedicated to reversing the humiliation of the Treaty of Aleppo and forging a pan-Turkish ethnonationalist state in the aftermath.

Perhaps predictably given its rhetoric, Killigil’s TRP found significant support within the ranks of the military elite and maintained significant support from the right-wing populist base built up over the past five years, however, the moderate wing of the party that had been removed from power was infuriated by a shift in Turanic platform that had not received any input whatsoever from said moderates. This resulted in the secession of moderate TRP members from the organization itself, with the Nationalist Party being officially declared on December 11th, 1927 under the leadership of Ahmet Ferit Tek after being hastily forged in time for the upcoming snap election. Running on a platform of protectionism, subsidized industrialization, social conservatism, and armed neutrality, the Nationalists sought to present themselves as an alternative for those turned away by the descent into fascism undertaken by the Turanics, however, this appeal was not enough to build up a base large enough to compete with the three major parties and instead simply cannibalized the right-wing vote.

The true extent to which the Nationalist Party had divided the right-wing of the Ottoman electorate would become apparent on December 18th, 1927, when millions of Turkish citizens voted in the second general election that year. The results were undeniably a mess, with no solution to the Ottoman Empire’s political gridlock nowhere in sight. The election day itself was plagued with violence as supporters from all parties clashed in cities throughout Turkey in an attempt to prevent their ideological opponents from voting. One foreign reporter from the New York Times declared that the chaotic sight of armed struggles in Constantinople marked “the death of Turkey’s short-lived democratic regime”. In terms of results, while the TRP had picked up seats in some places, it experienced a net loss in support thanks in large part to the Nationalists. Meanwhile, the ruling Freedom and Accord Party had seemingly been picked apart by all three opposition parties, further loosening the party’s grip on power. The only party that really seemed to experience a net benefit in the 1927 snap election was the Turkish Communist Party, which managed to just barely win a plurality of seats in the Chamber of Deputies by simultaneously evading the controversy that engulfed the parties to its right and amassing a dedicated base of working class support.

And so, rather than resolve the chaos that was the divided Chamber of Deputies, the snap election seemingly made things worse. No party was capable of forming a majority government, which condemned Turkey to a continuation of the ineffective and unpopular governance that had plagued the country for nearly a year, but now that the TKP held a plurality of seats, it was capable of forming a minority government should none of the other three parties agree to a coalition. Fearing that Mustafa Subhi would soon become grand vizier, the three parties to the right of the Communists scrambled in a panic to form a coalition with at least one other party in order to prevent the TKP from seizing power. After the collapse of their previous alliance, there was no way that the TRP and FAP would collaborate on forming a government yet again, even with the looming threat of a Communist government present.

This left the newly-formed Nationalist Party, which occupied a little over ten percent of the seats within the Chamber of Deputies, in a position as kingmaker between the TRP and FAP. While a coalition with the Nationalists and either the Turanics or the Freedom and Accord Party would not be large enough to secure a majority, either scenario would result in a coalition with more seats than the TKP and therefore enough support to form a minority government. While both the TRP and FAP did attempt to appeal to the Nationalist Party, it wasn’t much of a surprise to anyone when the uncompromising Killigil hesitated at making any offers to Tek that didn’t involve allowing for the Turanics to advance their entire fascist platform. A refusal on the part of the TRP to compromise, alongside bad blood between the Turanics and Nationalists due to the latter recently leaving the former, ultimately resulted in the formation of a minority coalition government between the FAP and Nationalists with Riza Tevfik Bey at the helm, under the condition that the Freedom and Accord Party would agree to support industrialization and militarization programs.

The FAP-Nationalist coalition was officially forged on December 27th, 1927. Many hoped that the new alliance would be much more capable of passing significant legislation than the Kemal administration due to the two member parties seeming to be more willing to work together, however, the fact of the matter was that was that the minority government only made up a little over forty percent of seats within the Chamber of Deputies, thus meaning that the TRP and TKP could gang up on initiatives they disagreed with and prevent the coalition from passing anything of importance. Surely enough, if there was one thing that Killigil and Subhi could agree on, it was that it was in their best interest to prevent the success of the Tevfik ministry, and much like the days of the FAP-TRP coalition, the only legislation that ever seemed to pass was moderate industrialization and militarization due to a chunk of Turanic MPs supporting such bills. To make matters worse, as the Ottoman government descended into incompetence, the TRP in particular turned to militancy as a means to accomplish its goals. The National Turkic Legion (NTL) was formed in January 1928 under the guidance of Nuri Killigil as the official paramilitary wing of the Turanic Renewal Party, and the party’s appeal to the armed forces meant that its ranks were quickly filled with many former soldiers, including experienced veterans of the Great War.

Members of the National Turkic Legion, circa March 1928.