You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"What happened to Governor Geary? has he returned to the usa to fight the good fight? or has he gone to kanas? or is he still in canada?

He's in Kansas, fighiting for the Union!

Out topic again, but I've been reading Eric Foner's Reconstruction book, and Carl Schurz bitterly disappoints me. I have read 1848 Year of Revolution, and the contrast between that young idealist and the politician who was advocating for a retreat from Reconstruction that would result in the reestablishement of White Supremacy is startling.

I do not think they expected slavery to exist in the 1860s. I read most of the Founding Fathers viewed slavery as a dying institution.I don’t think anyone expected the slave population to ever vote in 1787.

How about the War of Southern Treason.Too convoluted. It ought to be some thing simple like the War on treason or the civil war or the Southern rebellion

Is Alexander Randall still the governor of Wisconsin and what's he up to. In OTL he became the only governor to die while executing his duties as Commander in Chief of the state militia. He also was proposing the succession of Wisconsin if Lincoln hadn't won the election of 1860 - interesting dude

Apparently Winfield Scott was way too fat to sit on a horse at this time, which brings me an odd vision of Lincoln calling him, in private of course, "General-in-chief Too fat to sit a horse." and McClellan "General Stupid."*Happy gasp. My god an Overly simplified livestream about the american civil war! Some context for people that haven't read on history (if you haven't and are on this site, what fuck people how are existing?!)

I came across an excellent post Civil War story.

Let The Eagle Scream!

Chapter 1: The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson and "New Reconstruction" May 16th, 1868 The United States Senate has convened to convict President Andrew Johnson on "high crimes and misdemeanors." The vote will be close. The Democrats and several Republicans will not vote for impeachment. They...

www.alternatehistory.com

How about the War of Southern Treason.

The Slaveowners' Tantrum is what I'd call it

Indeed. To the point that Punch made two political cartoons where they compared Lincoln with Russian despotism and said that he and the Tsar were best friends. I find the poem they wrote "The President and the Tsar" particularly revealing about British views about the Civil War.

Out topic, but I finally watched Gone with the Wind. I'm rather conflicted, because the movie is obviously framed within the Lost Cause, especially with its negative stereotypes of Black people (Mammy is still awesome, especially for its time) and how it portrays the antebellum South as a land of chivalry and gallantry. How the movie sees promises such as Black voting and forty acres and a mule as horrifying is particularly though to swallow, especially in view of how, as TvTropes points out, everything the North does is good and the characters only see it as bad because they're a bunch of White supremacists. Overall, I liked the movie, and will probably watch Part I again in the future. I wonder if ITTL Gone with the Wind or its equivalent would be more egalitarian in virtue of how the war is seen as a struggle against a greedy aristocracy from the very beginning.

Genuinely fascinating to think about ITTL GWTW, which I've read several times (as well as seen the movie). I think that Rhett Butler, in the ITTL version, would be even more the voice of common sense and reason - his introduction, after all, showed him trying to point out to a disbelieving audience of plantation owners and their sons just how difficult a row the South would have to hoe in terms of manpower, resources and industry - the sinews of war - in the conflict to come; he didn't join the Confederate Army until after the fall of Atlanta, and then only because he was moved by the suffering of the ordinary Confederate soldiers he saw as he took Scarlett and Melanie back to Tara. His backstory has him being estranged from his wealthy family in Charleston due to a scandal; in the OTL version, this was due to an accusation of having "compromised" a local society girl which led to a duel with the girl's brother, but in TTL, it could be something involving slavery. I can see the TTL Rhett becoming first increasingly jaundiced about the planter aristocracy, then outright hostile to the point where he outright declares for the Union during Reconstruction, and talks Scarlett around to his point of view (with a little help from Mammy).

Maybe they even end up staying together this time!

Last edited:

My problem with Gone with the Wind was that I always found Scarlett so unlikeable that I couldn't sympathise with her, which undermines the narrative rather catastrophically.

I remember reading discussion in the TV Tropes entry on GWTW which speculated that Scarlett was a high-functioning sociopath or had some other sort of emotional/personality disorder. If anything, Scarlett is even more unlikable in the original novel than the movie; she wasn't particularly popular with the other local girls before the war due to her habit of flirting with their boyfriends, and seemed to make it a personal aim of hers to alienate everyone except Melanie and Mammy by the end of the novel/movie because she was so laser-focused on herself. Not to mention, of course, that she had totally ass-backward judgment about the sort of man who'd make a good life partner for her. There have been a couple of published attempts at sequels to fix that, though none of them really come off the way the original did.

“Frankly my dear I don’t give a damn “Maybe they even end up staying together this time!

ITTL Scarlett response to one of her Childhood friends asking what the southern belles will do without slaves.

I don't think Gone with the Wind will, if it gets written in the first place, have much of a success in this America if it glorifies the slaving traitors from the South in any way. No "Lost Cause" lies. No abandoned reconstruction. The 20th Century will be very different culturally, compared to OTL. Perhaps in its place, we'll see a book and movie depicting the plight of the slaves.

I don't think Gone with the Wind will, if it gets written in the first place, have much of a success in this America if it glorifies the slaving traitors from the South in any way. No "Lost Cause" lies. No abandoned reconstruction. The 20th Century will be very different culturally, compared to OTL. Perhaps in its place, we'll see a book and movie depicting the plight of the slaves.

Actually, IMO, the OTL novel was fairly, if quietly, subversive of the Lost Cause business, as viewed through its POV character, Scarlett (at one point, when someone produces a Confederate banknote with a piece of Lost Cause doggerel attached and reads it to the approval of the rest of the audience, Scarlett scornfully scoffs at it, remarking that she'd rather have a big wad of greenbacks - Federal banknotes, of course - to pass down to her children). I think the TTL Scarlett would be even more dismissive of the myth and more cynical/realistic about why the South went to war, probably putting her at direct odds with many of those in her circle (and ending up drawing her closer to the equally pragmatic Rhett). See @Ironshark above for the TTL context of the most famous quote from the book/movie.

I do not think they expected slavery to exist in the 1860s. I read most of the Founding Fathers viewed slavery as a dying institution.

It was dying until the cotton gin, which was invented to help slaves.

And that was when the South shifted from simply seeing slavery as something necessary for the economy, to seeing it as an essential part of their identity and culture, a political blessing to be defended no matter what.

How about the War of Southern Treason.

I'm partial to the "Great Southern Rebellion"

Is Alexander Randall still the governor of Wisconsin and what's he up to. In OTL he became the only governor to die while executing his duties as Commander in Chief of the state militia. He also was proposing the succession of Wisconsin if Lincoln hadn't won the election of 1860 - interesting dude

To be frank, I hadn't even thought of Randall. I remember reading his name on Foner's Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men, but I don't know much about his career during the civil war. Let's just assume he is indeed Wisconsin's governor.

*Happy gasp. My god an Overly simplified livestream about the american civil war! Some context for people that haven't read on history (if you haven't and are on this site, what fuck people how are existing?!)

Good ol' oversimplified. I really like his videos, though I will mention that I take issue with all the "Grant's a drunkard" jokes.

Apparently Winfield Scott was way too fat to sit on a horse at this time, which brings me an odd vision of Lincoln calling him, in private of course, "General-in-chief Too fat to sit a horse." and McClellan "General Stupid."

I don't think Lincoln would be that childish.

If I can ask, how's little William Lincoln doing? Does he still die around this time? His OTL death was pretty devastating for his parents, his mother especially.

He's doing fine, since the water of Philadelphia is of much better quality than that of Washington. His death will be butterflied away.

Genuinely fascinating to think about ITTL GWTW, which I've read several times (as well as seen the movie). I think that Rhett Butler, in the ITTL version, would be even more the voice of common sense and reason - his introduction, after all, showed him trying to point out to a disbelieving audience of plantation owners and their sons just how difficult a row the South would have to hoe in terms of manpower, resources and industry - the sinews of war - in the conflict to come; he didn't join the Confederate Army until after the fall of Atlanta, and then only because he was moved by the suffering of the ordinary Confederate soldiers he saw as he took Scarlett and Melanie back to Tara. His backstory has him being estranged from his wealthy family in Charleston due to a scandal; in the OTL version, this was due to an accusation of having "compromised" a local society girl which led to a duel with the girl's brother, but in TTL, it could be something involving slavery. I can see the TTL Rhett becoming first increasingly jaundiced about the planter aristocracy, then outright hostile to the point where he outright declares for the Union during Reconstruction, and talks Scarlett around to his point of view (with a little help from Mammy).Maybe they even end up staying together this time!

Rhett was my favorite character due to that. Rhett the scalawag would be an interesting position to take. Perhaps he could be portrayed as a Southern dazzled by the lies of the aristocracy, who came to see the war as something good and necessary following its end and cooperates with the new Reconstruction state.

I remember reading discussion in the TV Tropes entry on GWTW which speculated that Scarlett was a high-functioning sociopath or had some other sort of emotional/personality disorder. If anything, Scarlett is even more unlikable in the original novel than the movie; she wasn't particularly popular with the other local girls before the war due to her habit of flirting with their boyfriends, and seemed to make it a personal aim of hers to alienate everyone except Melanie and Mammy by the end of the novel/movie because she was so laser-focused on herself. Not to mention, of course, that she had totally ass-backward judgment about the sort of man who'd make a good life partner for her. There have been a couple of published attempts at sequels to fix that, though none of them really come off the way the original did.

Scarlett does seem very callous and selfish, though her more controversial acts only came after the war had taken everything from her. Sidenote, but I find it funny how everybody found it horrifying how she was willing to do business with carpetbaggers.

I don't think Gone with the Wind will, if it gets written in the first place, have much of a success in this America if it glorifies the slaving traitors from the South in any way. No "Lost Cause" lies. No abandoned reconstruction. The 20th Century will be very different culturally, compared to OTL. Perhaps in its place, we'll see a book and movie depicting the plight of the slaves.

Actually, IMO, the OTL novel was fairly, if quietly, subversive of the Lost Cause business, as viewed through its POV character, Scarlett (at one point, when someone produces a Confederate banknote with a piece of Lost Cause doggerel attached and reads it to the approval of the rest of the audience, Scarlett scornfully scoffs at it, remarking that she'd rather have a big wad of greenbacks - Federal banknotes, of course - to pass down to her children). I think the TTL Scarlett would be even more dismissive of the myth and more cynical/realistic about why the South went to war, probably putting her at direct odds with many of those in her circle (and ending up drawing her closer to the equally pragmatic Rhett). See @Ironshark above for the TTL context of the most famous quote from the book/movie.

An interesting alternate concept for Gone with the Wind.

Chapter 27: The Wounded and the Dying of Corinth's Hill

John C. Breckinridge had technically been serving as merely Provisional President until February 9th, 1861, when he was formally inaugurated as President of the Confederate States of America. That day was appropriately bleak, for the mood of the Southerners had sunk to its lowest level yet. Dressed in solemn dark suits, Breckinridge, Davis, and several Negro manservants attended the inauguration. A woman asked why everyone was dressed like that. “This, ma’am, is the way we always does in Richmond at funerals,” replied dryly the Negro coachman. Indeed, following the Second Maryland Campaign and the fall of Fort Donelson, it seemed like a funeral for the whole Confederate cause would soon be held.

But Breckinridge refused to surrender. He had pledged to achieve the independence of his country no matter what challenges he had to face. The President acknowledged that “after a series of successes and victories, which covered our arms with glory, we have recently met with serious disasters”. But their forebears in the American Revolution had suffered similar defeats before achieving ultimate victory. “Let us remember, that we are the inheritors of the heroic title of rebels, a name used by tyrants to denigrate those who struggle for the holy cause of Constitutional Liberty”, the President said. “For the sake of our country, and with the blessings of Providence, we must continue with patriotism and faith, and if need be part with our lives in the altar of freedom. Only then can be prove that we are truly worthy of this glorious inheritance.”

But the rebels still had many challenges before them, and many somber days would pass before victory once again revealed itself. Despite Breckinridge’s inspiring words, most Southerners remained sad and pessimistic. Mary Boykin Chesnut reported “nervous chills every day. Bad news is killing me”, while a soldier in Virginia talked of the “utter lack of patriotism that affects our men. Another disaster, and our perdition is assured.” Despite attempts by newspapers to argue that the twin defeats were for the good of the Southern people because “they have taught us the price of our freedom, and thus impel us to work with greater earnestness for it”, most Confederates felt anything but enthusiasm. Even Albert Sidney Johnston recognized that the loss of Fort Donelson “was most disastrous and almost without remedy”.

Having rejected Johnston’s resignation at the behest of Secretary of War Davis, now Breckinridge demanded action from the General. “I have defended you from attacks that have proved to be painful to the cause, and to me personally”, he wrote to Johnston, “the rule of war is that victory is the only thing that can earn respect and support.” “I think it’s a hard rule”, Johnston agreed, “but a fair one. In my profession, success is my only test of merit.” With that in mind, Johnston prepared for a new offensive. He had retreated towards Corinth, where soon the forces of Polk, who had abandoned Columbus, and Van Dorn, who had been recently beaten at Pea Ridge, joined him. These meager reinforcements could not replace the armies that had surrendered at Fort Donelson, but they did bolster Johnston’s command to around 40,000 men, who were joined by a further 15,000 rebels, taken from the defenses of New Orleans.

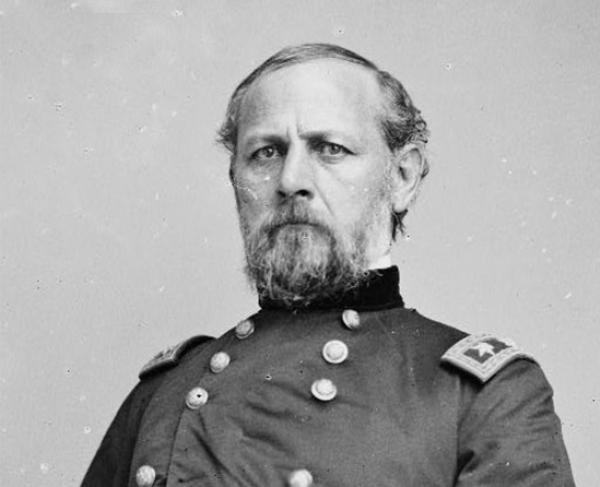

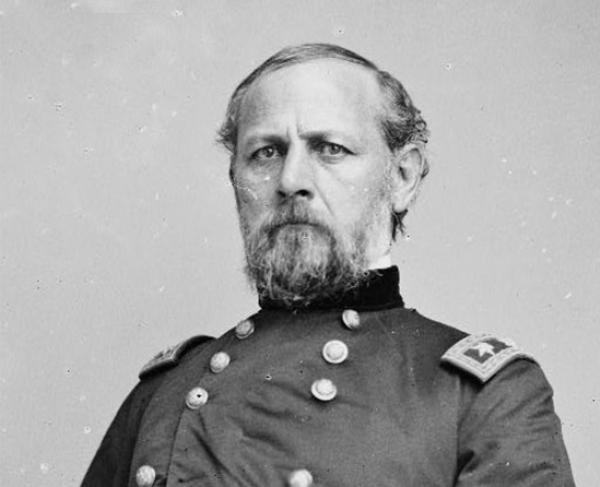

Johnston thus had 55,000 rebels to face the 80,000 Yankees in Grant and Buell’s united command. General Lyon, following President Lincoln’s wishes, wanted to cooperate with Buell to assault Corinth before Johnston was able to rebuild his army. Buell had been appointed to head the Department of the Ohio after Sherman had failed to advance fast enough to trap Johnston. A West Point graduate who had followed glory at Mexico with years at the Adjutant General’s department, Buell was a close ally of McClellan, and although he did not share McClellan’s charisma, Buell was his equal in administrative prowess and, unfortunately, slowness and timidity. Buell’s appointment is owned to the influence of Little Mac, who, expecting to be appointed General in-Chief, had worked to fill the departments with his supporters. Grant had accidentally offended the ambitious Buell by insisting on pursuing the Confederates and dismissing Buell’s fears of a Confederate counterattack to retake Nashville. This did not augur well for future cooperation.

Don Carlos Buell

Nonetheless, even if Buell couldn’t be counted as an ally, Grant had the confidence of General Lyon. Both had much in common – neither was particularly worried about military protocol, and both were aggressive and dynamic. Lyon never polished his boots, used a faded uniform, and often was found spreading a lot of mustard, a condiment he was very fond of, into slices of bread, even in the middle of battle. Grant similarly gave off a disheveled appearance, using a simple uniform, often caked with mud, and leading chaotic headquarters. These characteristics had earned them the scorn of many military men who were more preoccupied with playing the part of a modern general than winning the war. An example was Halleck, who had such contempt for Lyon and Grant that he often spread rumors of both being irresponsible drunkards.

Grant, always too trusting, was unable to see Halleck’s machinations and praised him as “a man of gigantic intellect, and well studied in the profession of arms.” Fortunately, Grant counted with a host of loyal allies. Aside from his loving wife Julia, Grant had the sincere friendship of John A. Rawlins, a young man who continuously defended Grant from sharp criticism and proved his best guardian against the allure of alcohol. Congressman Elihu Washburne, to whom Grant owned his appointment, served as his representative before the administration. Lincoln himself had come to appreciate Grant, reportedly saying that “I can’t spare this man – he fights”, when some people criticized the loss of life at the Battle of Dover. Lincoln had also provided Grant with another ally when he transferred William T. Sherman to his command.

An Ohioan like Grant, Sherman was a tall and lanky man, with reddish hair and a leathery face that showed his hardy nature. Cultured and capable, Sherman had a restive but passionate mind that never rested. Sherman’s upbringing in a respectable family that included his father, a Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court, and his brother, now a U.S. Senator, seemed to prepare Sherman for greatness. But he had floundered under stress, and was denounced as insane by a waspish press, despite his good performance at Baltimore. Disheartened by his dismissal as commander of the Ohio Department, Sherman fell into deep depression, even entertaining thoughts of suicide. But now he had a second chance, and meeting Grant would allow him to grow into one of the great heroes of the Union.

Both men would come to deeply respect each other. Sherman even remarked once that Grant “stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk, and now, sir, we stand by each other always.” Grant, for his part, praised Sherman as “not only a great soldier, but a great man.” Their mutual admiration was probably due to their shared outlook of the war, both being some bold officers who were not afraid of battle. Sherman was probably more literate when it came to the art of war, even saying that “I am a damned sight smarter man than Grant; I know a great deal more about war, military history, strategy, and grand tactics than he does.” But he admitted that Grant “knows, he divines, when the supreme hour has come in a campaign of battle, and always boldly seizes it.” Later, Sherman would pronounce Grant “the greatest soldier of our time if not all time”, a great tribute coming from a man who would eventually become a legend himself. The Battle of Corinth was where this great friendship was forged.

Albert Sydney Johnston was waiting at this critical rail junction, where two essential north-south and east-west railroads could be found. Breckinridge considered the defense of Corinth so vital that he approved the movement of troops from New Orleans to bolster Johnston’s force. But besides concentrating his forces, Johnston didn’t have a clear plan of action. The wounded Beauregard argued loudly in Richmond for a second offensive-defensive stroke, proposing to attack Grant’s men at Pittsburg’s Landing before Buell could join him. "We must do something," the former commander of the Army of Northern Virginia said, "or die in the attempt, otherwise, all will be shortly lost.” But Beauregard’s failure at the Second Maryland campaign had shattered Breckinridge’s faith on him, and neither Joe Johnston nor Davis were really predisposed to argue in his behalf.

Taking advantage of Beauregard’s injuries, Breckinridge stripped the General of his command and reduced him to an insignificant post as a military adviser. Adding insult to injury, Breckinridge refused to listen to the advice Beauregard provided. The Confederate President was shrewd enough to avoid insulting or humiliating Beauregard, and in fact took pains to praise him publicly, even asking the Confederate Congress to give Beauregard a promotion to a proposed rank of “Marshal of the Armies of the Confederacy”. However, Beauregard recognized that he had been reduced to little more than a clerk, and that his chances of retaking the reigns of the Army of Northern Virginia were slim. When Breckinridge trusted command of this army to Joe Johnston, who also remained General in-Chief, Beauregard definitely broke with the President, and would soon enough denounce him “the very essence of egotism, vanity, obstinacy, perversity, and vindictiveness.”

Elihu Washburne

In truth, Breckinridge wasn’t happy with Joe Johnston either, and would soon seek to replace him with Robert E. Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. The President was even considering James Longstreet for General in-chief. Since Longstreet was yet to forge his reputation in the battles for the North Carolina sound, and “Granny Lee” still hadn’t earned back the trust of the Southern people, Breckinridge for the moment was stuck with Johnston. But there is proof that he had already started to consider bringing both Virginians home for those important commands. It’s very noteworthy that Breckinridge was willing to ignore seniority and the usual chain of command, because Longstreet was outranked by Lee, Johnston and Beauregard, all of whom he would command if he were made General in-chief.

In the West, the practical result of these developments was that there was no one left to argue for an offensive against Grant, while both Johnstons argued for defense. Joe Johnston was being his usual cautious self, while Albert Sydney was chastised by the monumental failure of his attempt to attack Grant at Dover, and there was little reason to expect that an attack at Pittsburg’s Landing would go any different. On the other hand, the aggressive temperaments of both Grant and Lyon seemed to assure that an attack against Corinth would soon take place. Out of options, Johnston was forced to simply reinforce his position at Corinth and wait for Grant’s bluecoats.

Confederate prospects seemed bleak – many of Johnston’s reinforcements were green troops who “barely knew how to use a spade”, and his officers were inexperienced. Still, Johnston vowed to defend Corinth against all threats, vowing that the Yankees would never take the city “even if they were a million.” He soon issued a grandiose proclamation to his men, calling on then to defend “against agrarian mercenaries, sent to subjugate and despoil you of your liberties, property, and honor. . . . Remember the dependence of your mothers, your wives, your sisters, and your children on the result. . . . With such incentives to brave deeds . . . your generals will lead you confidently to the combat.”

The Union generals were also leading their men confidently. Believing the rebels shattered and afraid, Grant would even fall into overconfidence, telling Lyon that “the temper of the rebel troops is such that there is but little doubt but that Corinth will fall much more easily than Donelson did.” Preparations for the Battle of Corinth had taken a couple of months, and it would not be until March 10th that Grant had moved most of his troops to Savannah, Tennessee. Meanwhile, General Lyon conferred through telegram with President Lincoln to decide on a strategy. Lyon, who had come to trust and even admire Grant, believed that the Ohioan would be able to take Corinth himself, without Buell’s help. Besides probably saving months of effort and wait, this would allow Buell to focus on liberating East Tennessee. If Buell succeeded in this objective, the Reconstruction of Tennessee could start in earnest. A preview of it was given when Lincoln appointed the fiery Unionist William G. Brownlow as Military Governor of occupied Tennessee.

Brownlow was an “honest, fearless, vociferous man” that didn’t drink, smoke or dance. The editor of the Knoxville Whig, Brownlow had earned the nickname of Fighting Parson on account of his determination. Considered “the most dangerous enemy” by many Tennessee Confederates who feared his courage and rhetoric, Brownlow wasn’t limited to mere words, for he took part in a partisan attack that burned several bridges in East Tennessee, and when Confederate authorities showed up to arrest him, he managed a daring scape to the Federal lines of General Thomas. These events made him a celebrity in the North, and a leading figure of the new Southern Unionism that Lincoln was fostering in Maryland and Kansas – fiery, determined Unionists who didn’t just love the Union, but also hated the Confederacy and the Slavocrats that led it and were committed to a complete Reconstruction of the South.

William G. Brownlow

The personal shortcomings of Tennessee’s other prominent Unionist, Senator Andrew Johnson, made Lincoln decide to appoint Brownlow. On the surface, Johnson seemed like the better option, for he was established politician who had served as Governor of Tennessee already and also expressed contempt for slaveholders, who he believed were “not half as good as the man who earns his bread by the sweat of his brow.” But Johnson was self-absorbed, lonely and stubborn. As the only Southerner left in the Senate, he had presented resolutions to assure that the war was only for the maintenance of the Union, and though the Senate approved them at first, it later rejected them, which Johnson took as a personal insult.

The Radical actions of the Senate in following sessions further outraged Johnson, and soon enough he became a National Unionist who openly criticized the Lincoln administration and took failure to consider his more conservative measures as personal attacks. Johnson’s inherent racism also came to light, as he openly declared “Damn the Negroes, I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters,” on the Senate floor. These flaws soon became apparent to Lincoln, who finally settled on Brownlow. Partisanship also played a part, for the opposition of the National Union was hardening and the Republicans needed to stand together in response. Thus, Brownlow, a former Whig, seemed more promising that Johnson, a former Democrat and current National Unionist. However, the Brownlow regime would have to be secured by military success first.

Thus, even though East Tennessee was not a strategic priority, it became a political one, and Lyon and Grant were given the go ahead for an attack on Corinth. They would only have to wait for around 20,000 reinforcements from the Army of the Ohio, which would bolster their force to around 65,000. Grant would be leading the attack, and he proposed a bluff on the left and center of their lines before an all-out assault was launched, overrunning the Confederate right line and taking the railway hub. Sherman was trusted with the bluff, while General Charles F. Smith, who had once been Grant’s instructor at West Point but now was a trusted subordinate with a deep sense of respect for Grant, was to carry out the assault. In March 20th, Grant and his men marched forward to Corinth’s defenses, hoping for a glorious victory to follow their past successes and put an end to the rebellion in the West. But alas, as Grant was to declare later, “Providence ruled differently.”

The reason behind Providence’s change of opinion was that the stroke of genius that avoided Johnston at Dover finally arrived at Corinth. Instead of attacking Grant at Pittsburg Landing, or waiting for him like a sitting duck at Corinth, a strategy that offended his pride and his conception of the war, Johnston settled for a mixed strategy, allowing Grant to come to Corinth and attacking him after the initial Union attack had been repealed. That attack finally came in a rainy day on March 22nd, when, after a couple of days of skirmishes, Grant’s troops went forward. The idyllic forests near Corinth, which an Iowa soldier described as “delightful scenery, fit for a gigantic picnic”, soon became the scenery of one of the war’s most brutal battles, pitying 65,000 Yankees against 45,000 rebels.

As planned, Sherman buffed along the Confederacy’s left and center. But Johnston refused to take the bait, and instead engaged in much the same theatrics that had dazzled McClellan at Annapolis, such as dressing scarecrows in grey uniforms or using Quaker guns. It’s doubtful whether Sherman fell for such tricks, but since he had only been tasked with buffing and not with attacking, Sherman only launched a minor attack that Johnston’s defenses were able to withstand. Ultimately, most of the rebels remained in the Confederate right, where Smith led the attack. Soon enough, the battle degenerated into a “free-for-all of death in which brute force trumped tactical subtleties.” Yankee soldiers showed their pluck by fearless assaults upon the rebel positions, and in turn the Southerners answered with courage and endurance, resisting all attacks. When night fell, the Union Army had nothing to show for their attacks except thousands of deaths. Johnston now seized the initiative.

In the rainy night of March 23rd, Johnston’s rebel pickets advanced under the cover of the dark through a terrain they knew as well as the palms of their hands. The Federals had retreated to a small river called the Philipps Creek in March 21st, in order to gather their troops for an assault the next day. Grant did not believe a rebel counterattack possible, and indeed he decided not to build any kind of defenses or retrenchments, believing that the men “needed discipline and drill more than they did experience with the pick, shovel and axe.” Though he did warn his generals to be ready in response to reports of rebel maneuvers, he did not expect a general attack, and instead focused on what he planned to do the next day.

In respect to his breezy aptitude, historian Ron Chernow comments that “only a fine line separated immense self-confidence from egregious complacency and Grant had probably crossed it here.” Indeed, he wrote to his wife Julia saying that “in the morrow we will renew the attack on the defenses of Corinth, which I expect to be the greatest battle fought on the War. I do not feel that there is the slightest doubt about the result.” Grant was not caught completely by surprise as malicious newspapers later claimed, but Johnston and his screaming rebels did manage for once to get the drop on the Federals. When General Prentiss, legendary due to his defense of a salient at Dover, advanced as part of the renewed Union attack, he found rebel advance units near enough to hear the drums of Sherman’s men. Prentiss fell back as the rebels surged with a mighty battle cry.

Charles Fergunson Smith

Soon enough, they emerged into Sherman’s camp, where the General and his men were having a quick breakfast before launching their attack as planned. Sherman came forward with an orderly to see what was happening – and the orderly promptly fell, shot death by a rebel musket. “My God, we’re attacked!” cried Sherman. But instead of giving into panic as opponents expected due to his reputation as a madman, Sherman coolly rallied his troops into an effective defense line. “The next twelve hours proved to be the turning point of his life,” says historian James McPherson, “what he learned that day at Philipps Creek—about war and about himself— helped to make him one of the North's premier generals.” Soon enough, Johnston had committed all of his six divisions to the battle, while Grant in turn concentrated all his seven in a second bloody slog. By midafternoon, it seemed like the rebels would triumph, for they had managed to drive back the Union lines at least two miles.

But just like in Dover, Grant refused to retreat. Whereas a timid Easterner might have decided to flee after such a showing by the Confederates, Grant resolved to fight it out. The terrible casualties meant that night fell upon a horrible scene, of thousands of wounded men who suffered under the rain, unable to find any kind of solace for thunder and shells kept them awake. “This night of horrors will haunt me to my grave”, commented one of the Confederates who had to lay in mud and blood. Always cool under fire, Grant seemed insensible to the butchery around him, but in reality, he keenly felt the plight of his men. He was repealed by the sight of human suffering and the bloody carnage of the makeshift Union hospital, where amputated limbs were stacked in big stinking piles. A man who was so disgusted by blood that he could only eat meat burned to a crisp, Grant sought refuge from the rain in a hay bed under a tree.

Sherman joined him there, finding him wrapped in a greatcoat and chewing a cigar. “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”, Sherman said. “Yes,” replied Grant. “Lick’em tomorrow though”. Johnston, who once again shared his men’s discomfort by sleeping under a simple tent instead of Sherman’s comfortable headquarters, which he turned into a hospital, was decided to prevent his. A “vigorous, inspirational presence to his men”, Johnston itched for more battle and martial glory, but he recognized that in having driven Grant back from Corinth’s defenses and securing the important railway hub, he had already achieved a victory. But it was not the total victory he sought. Realizing how weary his soldiers were, Johnston decided to remain in the defensive the next day. By then he already knew Grant well enough to predict that he would attack at daybreak. And indeed, Grant ordered an attack at 4 a.m., remarking that “it is always a great advantage to be the attacking party. We must fire the first gun tomorrow morning.”

Consequently, in March 24th, at first light, Grant went forward. This time, the Federals gained the advantage, retaking the territory they had lost and driving the rebels back to their original defenses near the forests of Corinth, now covered by dense smoke. The rebels were unable to make a stand, but Johnston didn’t expect them to. Soon enough, he and his men retreated back to Corinth. After three days of battle, and with losses of 16,000 men in the Union side and 10,000 for the Confederacy, the result was status quo – Grant camped just outside Corinth, but the city still being in Confederate hands. Since Grant’s objective was taking Corinth, while Johnston’s was defending it, the battle can only be considered a Confederate victory. "After a fierce struggle of three days, thanks be to the Almighty, our troops have gained a complete victory, gloriously defending Corinth,” Johnston reported to Richmond.

The Battles of Corinth and Philipps’s Creek only continued the pattern of bloody fighting started by Dover and continued by the Second Maryland Campaign. They did much to give their final blow to the romantic innocence that characterized the first year of the war. While both Johnny Reb and Billy Yank had seen the war as a glorious and short endeavor, they were now cured of war, as Sherman remarked. Coming so soon after the Second Maryland Campaign, Corinth finally destroyed the conception of the war as a limited one and definitely set the country on the path towards a total war, one that sought the complete destruction of the enemy’s will and capacity to fight.

Both Grant and Sherman would be the main leaders of this new kind of war. Like a soldier who had said that the war would be over in just six more months but now prepared to “continue in my country's service until this rebellion is put down, should it be ten years”, Grant also realized that the war could not be ended with just a gigantic battle, but with “complete conquest.” Though newspapers begged to differ, for him Corinth had been a victory. “It would have set this war back six months to have failed and would have caused the necessity of raising . . . a new Army”, he declared, reflecting upon the consequences of complete Confederate success. But for most people, Corinth had been a failure, since the railway hub remained under Confederate control.

The Battle of Corinth

Another contemporary draw did little to improve the moral of the Union, when the iron behemoths CSS Virginia and USS Monitor faced each other at Hampton Roads. The CSS Virginia was built with the engines of the old USS Merrimack, captured by the Confederates soon after Virginia seceded. Those engines were old and had even been slated for replacement; nonetheless, they would have to do for the Confederacy was unable to build any engines herself. Covered with two layers of iron plate put at an angle so that enemy projectiles would ricochet, the Virginia was a formidable ship, even if it was slow and “so unmaneuverable that a 180-degree turn took half an hour”. The Virginia, also, was unable to operate in either shallow water or the open seas. But still, Southerners staked great hopes on their first Ironclad, as a secret weapon that would allow them to break the harmful blockade that so constricted them.

In response to reports of this rebel superweapon, Congress directed the construction of three proto-ironclads in August 3rd, 1861. Secretary of the Navy Welles, who at first was reluctant to experiment, set a board to examine several proposals. Jon Ericsson, the “irascible genius of marine engineering” known for several innovations, at first refused to submit a design, but he was finally convinced to by a friend. Aside from an iron plate that protected the vital machinery of the ship, Ericsson’s proposal, which resembled a giant raft, incorporated a revolving turret which “along with the shallow draft ( 1 1 feet), light displacement ( 1 , 2 0 0 tons, about onefourth of the Virginia's displacement), and eight-knot speed would give Ericsson's ship maneuverability and versatility”. Overcoming early skepticism, Ericsson managed to complete his Ironclad two weeks before the Confederates completed theirs, despite the fact that the development of the Virginia had started at least three months earlier. Christened the Monitor, the new ship would have no time for tests, for its help was urgently needed in Hampton Roads, where the Virginia was wreaking havoc.

On March 8th, the Virginia sailed for its test run, only to find the Union ships Minnesota, Roanoke, St. Lawrence, Congress, and Cumberland guarding the mouth of the James River at Hampton Roads. All those ships, totaling 219 guns and including two steam frigates and three sailing ships, had been alerted that the mighty Virginia was ready to sail, and they were decided to stop it. But the Virginia would soon enough show that Ironclads had made simple steam ships obsolete. Indeed, the guns of the Cumberland and Congress had “no more effect than peas from a pop-gun”, simply bouncing off the Virginia’s plating. In reality, the guns did manage to knock over at least two guns and damage the smokestack. But no gun managed to penetrate its armor, and the rebel iron beast managed to sink the Cumberland, blow the Congress up, and force the Minnesota to run aground. Thus ended “the worst day in the eighty-six-year history of the U. S. navy”, which took 2 ships and 240 Yankee sailors.

But the next day, and after fighting a storm on its way from Brooklyn, the Monitor arrived to face the Virginia. The Monitor, fast and easy to maneuver, was able to circle the Virgnia “like a fice dog”, hurling shots upon her all the while. A fierce battle developed:

The duel of the Ironclad was so impressive that the London Times would comment that “there is not now a ship in the English navy apart from these two [Britain’s experimental ironclads Warrior and Ironside] that it would not be madness to trust to an engagement with that little Monitor.” Both iron giants would warily eye each other, instead of fighting. But their legendary duel would also contribute to a further radicalization of the war effort in the seas as well as in land, and start a Revolution in terms of naval warfare – no longer the wooden ships of Nelson, but iron behemoths would patrol the seas and battle to control them. During the Civil War proper, this Revolution would be evident in the use of Ironclads by both sides, a total of 21 by the Confederacy and 58 by the Union, though for the most part wood warships remained the main enforcers of the blockade.

Battle of Hampton Roads

A couple of months later, the perception that wooden ships were obsolete was reinforced by the failure to capture New Orleans. Under the command of David G. Farragut, a sixty-year-old who had first gone to sea at the tender age of nine, a Union task force and around 15,000 men commanded by General Burnside approached New Orleans. By early April, Farragut had managed to reach the forts that protected that important city, and when that failed to subdue them completely, Farragut daringly ran the gauntlet and created an opening by cutting a chain. On April 24th, Farragut’s warships penetrated the river, but there they faced the Ironclad CSS Louisiana, which, fortunately for the rebels, had just been finished. President Breckinridge had pushed for its completition after seeing the success of the Virginia and being forced to remove troops from New Orleans to reinforce Johnston. He had also managed to kept this under wraps, so the appearance of a second rebel iron monster was indeed a surprise for the Union warships. Despite heavy bombardment, the Louisiana resisted, and finally the rebels managed to repulse the Union assault – for the time being.

Three draws that had accomplished nothing in the West joined inaction in the East to cause a downturn in Union morale. The great victory Lincoln had hoped for had not materialized at Corinth, Hampton Roads, or New Orleans, and the Emancipation Proclamation remained in his desk. These events did much to improve Southern morale, which had sagged extremely low after Second Maryland and Dover. The rebels would indeed need this morale boost, for it was in June, 1862, that McClellan and the Army of the Susquehanna finally marched forward, with the intention of giving the final blow to the rebellion.

But Breckinridge refused to surrender. He had pledged to achieve the independence of his country no matter what challenges he had to face. The President acknowledged that “after a series of successes and victories, which covered our arms with glory, we have recently met with serious disasters”. But their forebears in the American Revolution had suffered similar defeats before achieving ultimate victory. “Let us remember, that we are the inheritors of the heroic title of rebels, a name used by tyrants to denigrate those who struggle for the holy cause of Constitutional Liberty”, the President said. “For the sake of our country, and with the blessings of Providence, we must continue with patriotism and faith, and if need be part with our lives in the altar of freedom. Only then can be prove that we are truly worthy of this glorious inheritance.”

But the rebels still had many challenges before them, and many somber days would pass before victory once again revealed itself. Despite Breckinridge’s inspiring words, most Southerners remained sad and pessimistic. Mary Boykin Chesnut reported “nervous chills every day. Bad news is killing me”, while a soldier in Virginia talked of the “utter lack of patriotism that affects our men. Another disaster, and our perdition is assured.” Despite attempts by newspapers to argue that the twin defeats were for the good of the Southern people because “they have taught us the price of our freedom, and thus impel us to work with greater earnestness for it”, most Confederates felt anything but enthusiasm. Even Albert Sidney Johnston recognized that the loss of Fort Donelson “was most disastrous and almost without remedy”.

Having rejected Johnston’s resignation at the behest of Secretary of War Davis, now Breckinridge demanded action from the General. “I have defended you from attacks that have proved to be painful to the cause, and to me personally”, he wrote to Johnston, “the rule of war is that victory is the only thing that can earn respect and support.” “I think it’s a hard rule”, Johnston agreed, “but a fair one. In my profession, success is my only test of merit.” With that in mind, Johnston prepared for a new offensive. He had retreated towards Corinth, where soon the forces of Polk, who had abandoned Columbus, and Van Dorn, who had been recently beaten at Pea Ridge, joined him. These meager reinforcements could not replace the armies that had surrendered at Fort Donelson, but they did bolster Johnston’s command to around 40,000 men, who were joined by a further 15,000 rebels, taken from the defenses of New Orleans.

Johnston thus had 55,000 rebels to face the 80,000 Yankees in Grant and Buell’s united command. General Lyon, following President Lincoln’s wishes, wanted to cooperate with Buell to assault Corinth before Johnston was able to rebuild his army. Buell had been appointed to head the Department of the Ohio after Sherman had failed to advance fast enough to trap Johnston. A West Point graduate who had followed glory at Mexico with years at the Adjutant General’s department, Buell was a close ally of McClellan, and although he did not share McClellan’s charisma, Buell was his equal in administrative prowess and, unfortunately, slowness and timidity. Buell’s appointment is owned to the influence of Little Mac, who, expecting to be appointed General in-Chief, had worked to fill the departments with his supporters. Grant had accidentally offended the ambitious Buell by insisting on pursuing the Confederates and dismissing Buell’s fears of a Confederate counterattack to retake Nashville. This did not augur well for future cooperation.

Don Carlos Buell

Nonetheless, even if Buell couldn’t be counted as an ally, Grant had the confidence of General Lyon. Both had much in common – neither was particularly worried about military protocol, and both were aggressive and dynamic. Lyon never polished his boots, used a faded uniform, and often was found spreading a lot of mustard, a condiment he was very fond of, into slices of bread, even in the middle of battle. Grant similarly gave off a disheveled appearance, using a simple uniform, often caked with mud, and leading chaotic headquarters. These characteristics had earned them the scorn of many military men who were more preoccupied with playing the part of a modern general than winning the war. An example was Halleck, who had such contempt for Lyon and Grant that he often spread rumors of both being irresponsible drunkards.

Grant, always too trusting, was unable to see Halleck’s machinations and praised him as “a man of gigantic intellect, and well studied in the profession of arms.” Fortunately, Grant counted with a host of loyal allies. Aside from his loving wife Julia, Grant had the sincere friendship of John A. Rawlins, a young man who continuously defended Grant from sharp criticism and proved his best guardian against the allure of alcohol. Congressman Elihu Washburne, to whom Grant owned his appointment, served as his representative before the administration. Lincoln himself had come to appreciate Grant, reportedly saying that “I can’t spare this man – he fights”, when some people criticized the loss of life at the Battle of Dover. Lincoln had also provided Grant with another ally when he transferred William T. Sherman to his command.

An Ohioan like Grant, Sherman was a tall and lanky man, with reddish hair and a leathery face that showed his hardy nature. Cultured and capable, Sherman had a restive but passionate mind that never rested. Sherman’s upbringing in a respectable family that included his father, a Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court, and his brother, now a U.S. Senator, seemed to prepare Sherman for greatness. But he had floundered under stress, and was denounced as insane by a waspish press, despite his good performance at Baltimore. Disheartened by his dismissal as commander of the Ohio Department, Sherman fell into deep depression, even entertaining thoughts of suicide. But now he had a second chance, and meeting Grant would allow him to grow into one of the great heroes of the Union.

Both men would come to deeply respect each other. Sherman even remarked once that Grant “stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk, and now, sir, we stand by each other always.” Grant, for his part, praised Sherman as “not only a great soldier, but a great man.” Their mutual admiration was probably due to their shared outlook of the war, both being some bold officers who were not afraid of battle. Sherman was probably more literate when it came to the art of war, even saying that “I am a damned sight smarter man than Grant; I know a great deal more about war, military history, strategy, and grand tactics than he does.” But he admitted that Grant “knows, he divines, when the supreme hour has come in a campaign of battle, and always boldly seizes it.” Later, Sherman would pronounce Grant “the greatest soldier of our time if not all time”, a great tribute coming from a man who would eventually become a legend himself. The Battle of Corinth was where this great friendship was forged.

Albert Sydney Johnston was waiting at this critical rail junction, where two essential north-south and east-west railroads could be found. Breckinridge considered the defense of Corinth so vital that he approved the movement of troops from New Orleans to bolster Johnston’s force. But besides concentrating his forces, Johnston didn’t have a clear plan of action. The wounded Beauregard argued loudly in Richmond for a second offensive-defensive stroke, proposing to attack Grant’s men at Pittsburg’s Landing before Buell could join him. "We must do something," the former commander of the Army of Northern Virginia said, "or die in the attempt, otherwise, all will be shortly lost.” But Beauregard’s failure at the Second Maryland campaign had shattered Breckinridge’s faith on him, and neither Joe Johnston nor Davis were really predisposed to argue in his behalf.

Taking advantage of Beauregard’s injuries, Breckinridge stripped the General of his command and reduced him to an insignificant post as a military adviser. Adding insult to injury, Breckinridge refused to listen to the advice Beauregard provided. The Confederate President was shrewd enough to avoid insulting or humiliating Beauregard, and in fact took pains to praise him publicly, even asking the Confederate Congress to give Beauregard a promotion to a proposed rank of “Marshal of the Armies of the Confederacy”. However, Beauregard recognized that he had been reduced to little more than a clerk, and that his chances of retaking the reigns of the Army of Northern Virginia were slim. When Breckinridge trusted command of this army to Joe Johnston, who also remained General in-Chief, Beauregard definitely broke with the President, and would soon enough denounce him “the very essence of egotism, vanity, obstinacy, perversity, and vindictiveness.”

Elihu Washburne

In truth, Breckinridge wasn’t happy with Joe Johnston either, and would soon seek to replace him with Robert E. Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. The President was even considering James Longstreet for General in-chief. Since Longstreet was yet to forge his reputation in the battles for the North Carolina sound, and “Granny Lee” still hadn’t earned back the trust of the Southern people, Breckinridge for the moment was stuck with Johnston. But there is proof that he had already started to consider bringing both Virginians home for those important commands. It’s very noteworthy that Breckinridge was willing to ignore seniority and the usual chain of command, because Longstreet was outranked by Lee, Johnston and Beauregard, all of whom he would command if he were made General in-chief.

In the West, the practical result of these developments was that there was no one left to argue for an offensive against Grant, while both Johnstons argued for defense. Joe Johnston was being his usual cautious self, while Albert Sydney was chastised by the monumental failure of his attempt to attack Grant at Dover, and there was little reason to expect that an attack at Pittsburg’s Landing would go any different. On the other hand, the aggressive temperaments of both Grant and Lyon seemed to assure that an attack against Corinth would soon take place. Out of options, Johnston was forced to simply reinforce his position at Corinth and wait for Grant’s bluecoats.

Confederate prospects seemed bleak – many of Johnston’s reinforcements were green troops who “barely knew how to use a spade”, and his officers were inexperienced. Still, Johnston vowed to defend Corinth against all threats, vowing that the Yankees would never take the city “even if they were a million.” He soon issued a grandiose proclamation to his men, calling on then to defend “against agrarian mercenaries, sent to subjugate and despoil you of your liberties, property, and honor. . . . Remember the dependence of your mothers, your wives, your sisters, and your children on the result. . . . With such incentives to brave deeds . . . your generals will lead you confidently to the combat.”

The Union generals were also leading their men confidently. Believing the rebels shattered and afraid, Grant would even fall into overconfidence, telling Lyon that “the temper of the rebel troops is such that there is but little doubt but that Corinth will fall much more easily than Donelson did.” Preparations for the Battle of Corinth had taken a couple of months, and it would not be until March 10th that Grant had moved most of his troops to Savannah, Tennessee. Meanwhile, General Lyon conferred through telegram with President Lincoln to decide on a strategy. Lyon, who had come to trust and even admire Grant, believed that the Ohioan would be able to take Corinth himself, without Buell’s help. Besides probably saving months of effort and wait, this would allow Buell to focus on liberating East Tennessee. If Buell succeeded in this objective, the Reconstruction of Tennessee could start in earnest. A preview of it was given when Lincoln appointed the fiery Unionist William G. Brownlow as Military Governor of occupied Tennessee.

Brownlow was an “honest, fearless, vociferous man” that didn’t drink, smoke or dance. The editor of the Knoxville Whig, Brownlow had earned the nickname of Fighting Parson on account of his determination. Considered “the most dangerous enemy” by many Tennessee Confederates who feared his courage and rhetoric, Brownlow wasn’t limited to mere words, for he took part in a partisan attack that burned several bridges in East Tennessee, and when Confederate authorities showed up to arrest him, he managed a daring scape to the Federal lines of General Thomas. These events made him a celebrity in the North, and a leading figure of the new Southern Unionism that Lincoln was fostering in Maryland and Kansas – fiery, determined Unionists who didn’t just love the Union, but also hated the Confederacy and the Slavocrats that led it and were committed to a complete Reconstruction of the South.

William G. Brownlow

The personal shortcomings of Tennessee’s other prominent Unionist, Senator Andrew Johnson, made Lincoln decide to appoint Brownlow. On the surface, Johnson seemed like the better option, for he was established politician who had served as Governor of Tennessee already and also expressed contempt for slaveholders, who he believed were “not half as good as the man who earns his bread by the sweat of his brow.” But Johnson was self-absorbed, lonely and stubborn. As the only Southerner left in the Senate, he had presented resolutions to assure that the war was only for the maintenance of the Union, and though the Senate approved them at first, it later rejected them, which Johnson took as a personal insult.

The Radical actions of the Senate in following sessions further outraged Johnson, and soon enough he became a National Unionist who openly criticized the Lincoln administration and took failure to consider his more conservative measures as personal attacks. Johnson’s inherent racism also came to light, as he openly declared “Damn the Negroes, I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters,” on the Senate floor. These flaws soon became apparent to Lincoln, who finally settled on Brownlow. Partisanship also played a part, for the opposition of the National Union was hardening and the Republicans needed to stand together in response. Thus, Brownlow, a former Whig, seemed more promising that Johnson, a former Democrat and current National Unionist. However, the Brownlow regime would have to be secured by military success first.

Thus, even though East Tennessee was not a strategic priority, it became a political one, and Lyon and Grant were given the go ahead for an attack on Corinth. They would only have to wait for around 20,000 reinforcements from the Army of the Ohio, which would bolster their force to around 65,000. Grant would be leading the attack, and he proposed a bluff on the left and center of their lines before an all-out assault was launched, overrunning the Confederate right line and taking the railway hub. Sherman was trusted with the bluff, while General Charles F. Smith, who had once been Grant’s instructor at West Point but now was a trusted subordinate with a deep sense of respect for Grant, was to carry out the assault. In March 20th, Grant and his men marched forward to Corinth’s defenses, hoping for a glorious victory to follow their past successes and put an end to the rebellion in the West. But alas, as Grant was to declare later, “Providence ruled differently.”

The reason behind Providence’s change of opinion was that the stroke of genius that avoided Johnston at Dover finally arrived at Corinth. Instead of attacking Grant at Pittsburg Landing, or waiting for him like a sitting duck at Corinth, a strategy that offended his pride and his conception of the war, Johnston settled for a mixed strategy, allowing Grant to come to Corinth and attacking him after the initial Union attack had been repealed. That attack finally came in a rainy day on March 22nd, when, after a couple of days of skirmishes, Grant’s troops went forward. The idyllic forests near Corinth, which an Iowa soldier described as “delightful scenery, fit for a gigantic picnic”, soon became the scenery of one of the war’s most brutal battles, pitying 65,000 Yankees against 45,000 rebels.

As planned, Sherman buffed along the Confederacy’s left and center. But Johnston refused to take the bait, and instead engaged in much the same theatrics that had dazzled McClellan at Annapolis, such as dressing scarecrows in grey uniforms or using Quaker guns. It’s doubtful whether Sherman fell for such tricks, but since he had only been tasked with buffing and not with attacking, Sherman only launched a minor attack that Johnston’s defenses were able to withstand. Ultimately, most of the rebels remained in the Confederate right, where Smith led the attack. Soon enough, the battle degenerated into a “free-for-all of death in which brute force trumped tactical subtleties.” Yankee soldiers showed their pluck by fearless assaults upon the rebel positions, and in turn the Southerners answered with courage and endurance, resisting all attacks. When night fell, the Union Army had nothing to show for their attacks except thousands of deaths. Johnston now seized the initiative.

In the rainy night of March 23rd, Johnston’s rebel pickets advanced under the cover of the dark through a terrain they knew as well as the palms of their hands. The Federals had retreated to a small river called the Philipps Creek in March 21st, in order to gather their troops for an assault the next day. Grant did not believe a rebel counterattack possible, and indeed he decided not to build any kind of defenses or retrenchments, believing that the men “needed discipline and drill more than they did experience with the pick, shovel and axe.” Though he did warn his generals to be ready in response to reports of rebel maneuvers, he did not expect a general attack, and instead focused on what he planned to do the next day.

In respect to his breezy aptitude, historian Ron Chernow comments that “only a fine line separated immense self-confidence from egregious complacency and Grant had probably crossed it here.” Indeed, he wrote to his wife Julia saying that “in the morrow we will renew the attack on the defenses of Corinth, which I expect to be the greatest battle fought on the War. I do not feel that there is the slightest doubt about the result.” Grant was not caught completely by surprise as malicious newspapers later claimed, but Johnston and his screaming rebels did manage for once to get the drop on the Federals. When General Prentiss, legendary due to his defense of a salient at Dover, advanced as part of the renewed Union attack, he found rebel advance units near enough to hear the drums of Sherman’s men. Prentiss fell back as the rebels surged with a mighty battle cry.

Charles Fergunson Smith

Soon enough, they emerged into Sherman’s camp, where the General and his men were having a quick breakfast before launching their attack as planned. Sherman came forward with an orderly to see what was happening – and the orderly promptly fell, shot death by a rebel musket. “My God, we’re attacked!” cried Sherman. But instead of giving into panic as opponents expected due to his reputation as a madman, Sherman coolly rallied his troops into an effective defense line. “The next twelve hours proved to be the turning point of his life,” says historian James McPherson, “what he learned that day at Philipps Creek—about war and about himself— helped to make him one of the North's premier generals.” Soon enough, Johnston had committed all of his six divisions to the battle, while Grant in turn concentrated all his seven in a second bloody slog. By midafternoon, it seemed like the rebels would triumph, for they had managed to drive back the Union lines at least two miles.

But just like in Dover, Grant refused to retreat. Whereas a timid Easterner might have decided to flee after such a showing by the Confederates, Grant resolved to fight it out. The terrible casualties meant that night fell upon a horrible scene, of thousands of wounded men who suffered under the rain, unable to find any kind of solace for thunder and shells kept them awake. “This night of horrors will haunt me to my grave”, commented one of the Confederates who had to lay in mud and blood. Always cool under fire, Grant seemed insensible to the butchery around him, but in reality, he keenly felt the plight of his men. He was repealed by the sight of human suffering and the bloody carnage of the makeshift Union hospital, where amputated limbs were stacked in big stinking piles. A man who was so disgusted by blood that he could only eat meat burned to a crisp, Grant sought refuge from the rain in a hay bed under a tree.

Sherman joined him there, finding him wrapped in a greatcoat and chewing a cigar. “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”, Sherman said. “Yes,” replied Grant. “Lick’em tomorrow though”. Johnston, who once again shared his men’s discomfort by sleeping under a simple tent instead of Sherman’s comfortable headquarters, which he turned into a hospital, was decided to prevent his. A “vigorous, inspirational presence to his men”, Johnston itched for more battle and martial glory, but he recognized that in having driven Grant back from Corinth’s defenses and securing the important railway hub, he had already achieved a victory. But it was not the total victory he sought. Realizing how weary his soldiers were, Johnston decided to remain in the defensive the next day. By then he already knew Grant well enough to predict that he would attack at daybreak. And indeed, Grant ordered an attack at 4 a.m., remarking that “it is always a great advantage to be the attacking party. We must fire the first gun tomorrow morning.”

Consequently, in March 24th, at first light, Grant went forward. This time, the Federals gained the advantage, retaking the territory they had lost and driving the rebels back to their original defenses near the forests of Corinth, now covered by dense smoke. The rebels were unable to make a stand, but Johnston didn’t expect them to. Soon enough, he and his men retreated back to Corinth. After three days of battle, and with losses of 16,000 men in the Union side and 10,000 for the Confederacy, the result was status quo – Grant camped just outside Corinth, but the city still being in Confederate hands. Since Grant’s objective was taking Corinth, while Johnston’s was defending it, the battle can only be considered a Confederate victory. "After a fierce struggle of three days, thanks be to the Almighty, our troops have gained a complete victory, gloriously defending Corinth,” Johnston reported to Richmond.

The Battles of Corinth and Philipps’s Creek only continued the pattern of bloody fighting started by Dover and continued by the Second Maryland Campaign. They did much to give their final blow to the romantic innocence that characterized the first year of the war. While both Johnny Reb and Billy Yank had seen the war as a glorious and short endeavor, they were now cured of war, as Sherman remarked. Coming so soon after the Second Maryland Campaign, Corinth finally destroyed the conception of the war as a limited one and definitely set the country on the path towards a total war, one that sought the complete destruction of the enemy’s will and capacity to fight.

Both Grant and Sherman would be the main leaders of this new kind of war. Like a soldier who had said that the war would be over in just six more months but now prepared to “continue in my country's service until this rebellion is put down, should it be ten years”, Grant also realized that the war could not be ended with just a gigantic battle, but with “complete conquest.” Though newspapers begged to differ, for him Corinth had been a victory. “It would have set this war back six months to have failed and would have caused the necessity of raising . . . a new Army”, he declared, reflecting upon the consequences of complete Confederate success. But for most people, Corinth had been a failure, since the railway hub remained under Confederate control.

The Battle of Corinth

Another contemporary draw did little to improve the moral of the Union, when the iron behemoths CSS Virginia and USS Monitor faced each other at Hampton Roads. The CSS Virginia was built with the engines of the old USS Merrimack, captured by the Confederates soon after Virginia seceded. Those engines were old and had even been slated for replacement; nonetheless, they would have to do for the Confederacy was unable to build any engines herself. Covered with two layers of iron plate put at an angle so that enemy projectiles would ricochet, the Virginia was a formidable ship, even if it was slow and “so unmaneuverable that a 180-degree turn took half an hour”. The Virginia, also, was unable to operate in either shallow water or the open seas. But still, Southerners staked great hopes on their first Ironclad, as a secret weapon that would allow them to break the harmful blockade that so constricted them.

In response to reports of this rebel superweapon, Congress directed the construction of three proto-ironclads in August 3rd, 1861. Secretary of the Navy Welles, who at first was reluctant to experiment, set a board to examine several proposals. Jon Ericsson, the “irascible genius of marine engineering” known for several innovations, at first refused to submit a design, but he was finally convinced to by a friend. Aside from an iron plate that protected the vital machinery of the ship, Ericsson’s proposal, which resembled a giant raft, incorporated a revolving turret which “along with the shallow draft ( 1 1 feet), light displacement ( 1 , 2 0 0 tons, about onefourth of the Virginia's displacement), and eight-knot speed would give Ericsson's ship maneuverability and versatility”. Overcoming early skepticism, Ericsson managed to complete his Ironclad two weeks before the Confederates completed theirs, despite the fact that the development of the Virginia had started at least three months earlier. Christened the Monitor, the new ship would have no time for tests, for its help was urgently needed in Hampton Roads, where the Virginia was wreaking havoc.

On March 8th, the Virginia sailed for its test run, only to find the Union ships Minnesota, Roanoke, St. Lawrence, Congress, and Cumberland guarding the mouth of the James River at Hampton Roads. All those ships, totaling 219 guns and including two steam frigates and three sailing ships, had been alerted that the mighty Virginia was ready to sail, and they were decided to stop it. But the Virginia would soon enough show that Ironclads had made simple steam ships obsolete. Indeed, the guns of the Cumberland and Congress had “no more effect than peas from a pop-gun”, simply bouncing off the Virginia’s plating. In reality, the guns did manage to knock over at least two guns and damage the smokestack. But no gun managed to penetrate its armor, and the rebel iron beast managed to sink the Cumberland, blow the Congress up, and force the Minnesota to run aground. Thus ended “the worst day in the eighty-six-year history of the U. S. navy”, which took 2 ships and 240 Yankee sailors.

But the next day, and after fighting a storm on its way from Brooklyn, the Monitor arrived to face the Virginia. The Monitor, fast and easy to maneuver, was able to circle the Virgnia “like a fice dog”, hurling shots upon her all the while. A fierce battle developed:

For two hours the ironclads slugged it out. Neither could punch through the other's armor, though the Monitor's heavy shot cracked the Virginias outside plate at several places. At one point the southern ship grounded. As the shallower-draft Monitor closed in, many aboard the Virginia thought they were finished. But she broke loose and continued the fight, trying without success to ram the Monitor. By this time the Virginias wheezy engines were barely functioning, and one of her lieutenants found her "as unwieldly as Noah's Ark." The Monitor in turn tried to ram the Virginia's stern to disable her rudder or propeller, but just missed. Soon after this a shell from the Virginia struck the Monitors pilot house, wounding her captain. The Union ship stopped fighting briefly; the Virginia, in danger of running aground again, steamed back toward Norfolk. Each crew thought they had won the battle, but in truth it was a draw. The exhausted men on both sides ceased fighting—almost, it seemed, by mutual consent.

The duel of the Ironclad was so impressive that the London Times would comment that “there is not now a ship in the English navy apart from these two [Britain’s experimental ironclads Warrior and Ironside] that it would not be madness to trust to an engagement with that little Monitor.” Both iron giants would warily eye each other, instead of fighting. But their legendary duel would also contribute to a further radicalization of the war effort in the seas as well as in land, and start a Revolution in terms of naval warfare – no longer the wooden ships of Nelson, but iron behemoths would patrol the seas and battle to control them. During the Civil War proper, this Revolution would be evident in the use of Ironclads by both sides, a total of 21 by the Confederacy and 58 by the Union, though for the most part wood warships remained the main enforcers of the blockade.

Battle of Hampton Roads

A couple of months later, the perception that wooden ships were obsolete was reinforced by the failure to capture New Orleans. Under the command of David G. Farragut, a sixty-year-old who had first gone to sea at the tender age of nine, a Union task force and around 15,000 men commanded by General Burnside approached New Orleans. By early April, Farragut had managed to reach the forts that protected that important city, and when that failed to subdue them completely, Farragut daringly ran the gauntlet and created an opening by cutting a chain. On April 24th, Farragut’s warships penetrated the river, but there they faced the Ironclad CSS Louisiana, which, fortunately for the rebels, had just been finished. President Breckinridge had pushed for its completition after seeing the success of the Virginia and being forced to remove troops from New Orleans to reinforce Johnston. He had also managed to kept this under wraps, so the appearance of a second rebel iron monster was indeed a surprise for the Union warships. Despite heavy bombardment, the Louisiana resisted, and finally the rebels managed to repulse the Union assault – for the time being.

Three draws that had accomplished nothing in the West joined inaction in the East to cause a downturn in Union morale. The great victory Lincoln had hoped for had not materialized at Corinth, Hampton Roads, or New Orleans, and the Emancipation Proclamation remained in his desk. These events did much to improve Southern morale, which had sagged extremely low after Second Maryland and Dover. The rebels would indeed need this morale boost, for it was in June, 1862, that McClellan and the Army of the Susquehanna finally marched forward, with the intention of giving the final blow to the rebellion.

Last edited:

mclellan is about to be supressed isn't he?

well at least the rebels won't go down until a long fight..that means more of them dead and therefore reconstruction will be eaiser .(plus it makes a more fun story)

curious to see what grant and lyon are going to do now ..there in a tough stop unless they can get room to manvuer ..politlicaly and militarily.

well at least the rebels won't go down until a long fight..that means more of them dead and therefore reconstruction will be eaiser .(plus it makes a more fun story)

curious to see what grant and lyon are going to do now ..there in a tough stop unless they can get room to manvuer ..politlicaly and militarily.

If ironclads are going to be more of a thing for the south than OTL then i imagine that the navy will have a helluva time trying to take the Mississippi. Honestly designs like the monitor are pretty apt for river combat, more so than the open sea or even the littoral zones, if only because the weather there wont get bad enough to sink them.

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: