Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword

At the end of 1864, the Confederacy had no hopes for a victory on the field. The Armies of the United States were now occupying large swathes of its territory, and the soldiers of Sherman marched at will through the Carolinas, the Southern forces utterly incapable to even slow him down. The institution of slavery, which they had seceded to protect, now laid in tatters, hundreds of thousands of enslaved people having been emancipated and settled in confiscated land. The triumphal re-election of Abraham Lincoln as President demonstrated that the Northern people possessed the strength of will to continue the fight, and the determination to destroy the old Southern order. The victory of the Union and the dismantlement of the Confederacy were at last here, after four years of struggle. But, tragically, as the authority and power of the Confederacy collapsed, the South descended into anarchy, riots, and famine. Just like how Breckinridge had predicted, continuing the fight against impossible odds had only turned the war into a bloody, catastrophic fiasco.

The most disastrous part of that fiasco was the start of the Southern Famine of 1864-1865, alongside several more localized but still deadly outbreaks of disease. The reasons for the famine are several, all of them related to the war and the policies of the Union and Confederacy. The chief one was the throughout devastation of Southern agriculture and its networks of transportation. Grant’s campaigns in Tennessee and the Mississippi Valley; Rosecrans’ in Arkansas and Louisiana; Sherman’s in Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina; all of these had laid waste to the rails and canals of the South, meaning that even when food could be raised it was almost impossible to get it to where it was needed. Moreover, the Union’s adoption of a policy of land redistribution and the continuous pressure of guerrilla warfare enormously disrupted the ordinary cycles of agriculture. Many plantations were razed, and the back and forth of destruction meant that they were unable to resume their activities until a firm Union grip was established.

Yet, the coming of Union rule did not solve the problem of food scarcity. Because Northerners were interested above all in the reestablishment of antebellum crop production, the Federal authorities primarily encouraged the cultivation of cotton, feeding the people through supplies brought from the North. Alongside the division of the previous large estates, this meant a drastic decline in the production of food throughout the liberated areas. Yet another factor was that the emancipation of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people deprived plantations of desperately needed labor. In peaceful areas, women and children initially retreated from the fields; in war-thorn regions, they worked, but it was the men who were kept away as soldiers in Home Farm regiments or Union paramilitaries. The pattern of slavery was kept, in that the people focused on raising cash crops, keeping livestock and vegetable patches as merely supplementary activities, and relying on the Federals for the bulk of maize, flour, and sugar that fed them. The situation was similar in the Confederacy, where enslavers, especially after the Junta repealed all of Breckinridge’s decrees, preferred to raise cotton, believing they could take the oath as soon as the Union arrived and sell it for immense profit.

The outlook was even worse in the areas that had been devastated by recent Union campaigns. In Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, the march of the bluecoats had resulted in plundered plantations and the consumption of food stores, as the hungry Yankees descended like locusts onto everything they found. This meant the destruction of a great amount of produce at the peak of the harvest, with the disorder than ensued assuring that no more food could be planted for a while. Even outside of the direct Federal path, poor Whites and freedmen forcibly took plantations, which too obstructed agriculture, and most of the time the food available was not enough. The Union did try to offer relief, but it severely underestimated the logistical challenge it was taking upon itself. With food stores depleted and rail networks destroyed, the Union just had no feasible way to transport enough food into the hunger-stricken counties.

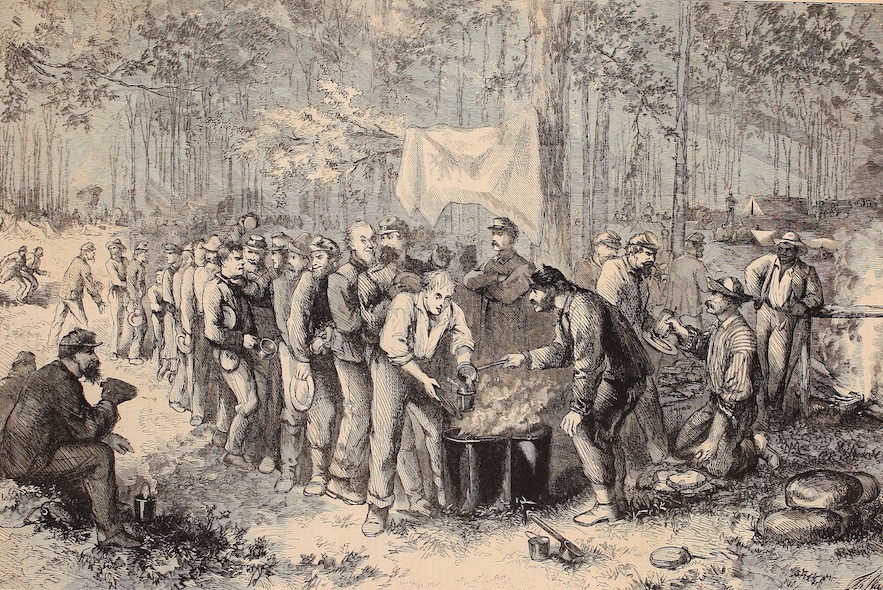

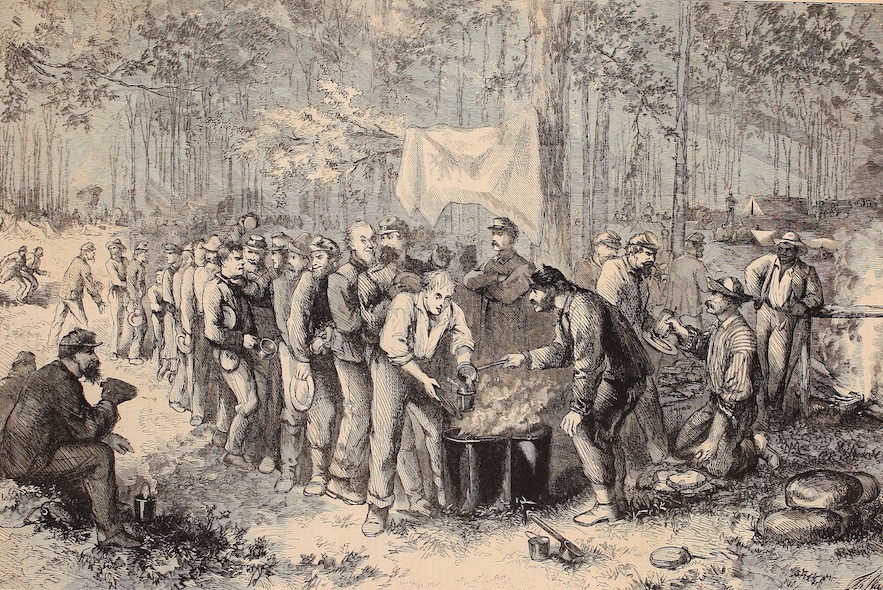

Federal food relief efforts

Still another factor was the severe dislocations the Southern countryside had suffered as a result of guerrilla warfare, Union expulsions, and the tide of refugees. All of these resulted in hundreds of thousands of people fleeing their homes and farms and gathering either in overcrowded Union camps or war-swollen Southern cities. Cities like Richmond and Columbia struggled to feed both armies and civilians, effectively meaning that soldiers competed with common people for dwindling supplies – and in this, a soldier with a gun had the upper hand over defenseless women and children. This created a situation where refugees would flood particular points for food, and then fan across the countryside, surviving meagerly in the meantime. This contributed to the spread of deadly diseases, as the emergency infrastructure erected just was unable to hold all the people in hygienic conditions. For example, the depot the Union established in Atlanta was expected to aid only 10,000 people – over 30,000 refugees crowded it instead.

Epidemics of yellow fever in the Mississippi Valley, Georgia, and the Carolinas; of scarlet fever in Pennsylvania and the Lower North; and of smallpox in Tennessee and the Border States, all claimed thousands of lives. When people gathered into hastily organized Army camps to try and stave off famine, they found, just like the soldiers who mustered in 1861-1862, that disease could be the greatest killer. The response of the Bureaus was ineffective, mostly because dismantling the camps would mean not feeding the hungry people. With winter coming and the crops still not ready to be harvested, this was not to be thought of. Instead, Bureau agents tried desperately to improve the camps, build more, and establish a presence in the countryside. But the Bureau was still entirely dependent upon the Army, which, still on a wartime footing, only established few supply depots and had most of its personal tied up in anti-guerrilla and supply guarding duties. Consequently, there were very few soldiers who could carry the sustenance into the countryside, and the Union struggled to get enough to feed all this people and its soldiers. For example, General Thomas received 45,000 pounds of meat per week for the Atlanta civilians, when in reality he needed 45,000 pounds per day.

The situation was even more critical in the Confederacy. Whereas Breckinridge had attempted an organized national response to widespread hunger through his food-relief corps and several decrees that forced the planting of foodstuffs, the Junta had repealed his programs. Instead, the task of averting famine fell upon the State governments. Georgia Governor Brown tried his hardest to help the poor, distributing salt and wheat to the hungry, but after Sherman’s march his State government was basically defunct. This meant that the civilians had to be fed by the Union, resulting in the problems already described, since the Federals had neither the infrastructure nor the men to establish an effective food supply for the thousands of refugees in cities like Savanah and Mobile. Those who remained under Confederate control fared even worse, for the Junta never established any mechanisms of food relief, and the State governments were powerless to intervene. Thus, while civilians in Union-held areas faced insufficient relief, civilians in Confederate areas had no relief at all.

The lack of resources could also be explained by the ever-tightening noose of the blockade, which by now was so effective that few ships could bypass it. Furthermore, the informal trade between lines had also largely stopped, partly because of a reluctance to trade with the Junta, partly because the rebels lacked the specie to pay for Northern products. Without the salt and foodstuffs that had been entering through the lines and the blockade, the situation was growing direr. Moreover, the disastrous inflation the Confederacy had been suffering had been only worsened by the Coup. Since the Confederate grayback had been effectively backed by public confidence in victory, the latest defeats had rendered it worthless. In the cities where food could still be found, the joke went, “shoppers took their money to the market in bushel baskets and returned with their purchases in their pocketbooks.” In other localities the graybacks replaced timber in fireplaces, in a desperate attempt to keep warm.

Even more disastrously, the rebel armies continued and intensified their policies of forced impressment and scorched earth. By then reduced by desertion and defeat to “little more than a band of marauders” in the words of one of them, the Confederate soldiers despoiled their own civilians of foodstuffs and destroyed plantations and resources before Sherman could do it. To bolster their ranks, they engaged in a strategy of forced recruitment, with entire towns remembering bands of “the worst cutthroats and savages” arriving and taking every male over thirteen years. This, too, disrupted agriculture, for the farms were left without men to reap the harvest or plant a new crop. Resistance could result in abominable reprisals, such as the summary execution of draft-dodgers or even massacres in localities that tried to resist them. A South Carolina deserter who tried to hide his grain, for example, was hung in front of his horrified wife and children. The Junta that had formed partly in reaction to Breckinridge’s so-called “monstrous” policies of impressment were now just engaging in an even more pitiless policy.

Refugee camps

In truth, it’s difficult to know how much of these actions were done under the orders or even with the knowledge of the Junta, given how the Coup just resulted in a breakdown of the centralized war-effort Breckinridge had instituted. With no real control from Richmond, Confederate armies became irregular forces that victimized vulnerable Southerners. Yet, the Junta never even tried to restrain its soldiers or formulate an organized response to these calamitous circumstances. Instead, the official orders and pronouncements that were there consistently called for greater and more ruthless terror against dissidents and “defeatists.” Senator Graham thus was executed after he was found hatching a second peace scheme, and Breckinridge’s Secretaries all were shot in the middle of the night after secret summary trials. Senator Wigfall, too, was never seen again after his arrest. In Western North Carolina, the greatest and most horrific consequence was the massacre of around 80 men, women, and children in the town of Hillsborough, Holden’s birthplace, after it tried to secede in imitation of Mississippi’s Free State of Jones. Appallingly, even as the manpower situation grew critical in several areas, the Junta also found men to spare to send them to “maintain order” in plantations, which often meant massacring and torturing Black people.

Seeing hunger and repression at home, desertions sharply increased in the Confederate Armed forces. A despairing wife for example wrote to her husband “Our son is lying at death’s door, his hunger unbearable, his earnest calls for Pa breaking my heart. John, come home!” Under Breckinridge the government had tried to use the carrot instead of the stick, distributing bounties and pardons. Breckinridge had even personally pardoned many deserters. But now the Junta tolerated no such weakness. “Thoughtless and imprudent letters” that “may lead to discontent, desertion,” were censored to avoid “defeatist” messages, and executions of deserters rose dramatically. So did the efforts to resist them – for example, a mutinous North Carolina company ended up shooting death their officers. Governor Vance described in despair how these men “now bring with them Government arms and ammunitions . . . the bands of deserters now outnumber the home guards.” Thousands of men were placed behind Confederate lines to shoot deserters instead of Yankees. But, Benjamin Justice testified, “The men on the picket line fire off their guns in the air & will not try to shoot down those who are in the act of deserting to the enemy.”

That enemy now seemed more merciful than their own government. Rebels were now “fast leaving the sinking ship” by the thousands, reported the New York Times, availing themselves of the Federals’ food and warmth in exchange of taking the oath. “We have the pleasure of greeting many of the prodigal sons of Father Abraham, who, having repented, are returning honorably to worship at the shrine of their former devotion,” reported the Black correspondent Thomas Morris Chester. Southerners were “disgusted with the rebel authorities for continuing a struggle in which no one has the sightless prospect of success . . . merely to save the most guilty from the impending penalties.” Toombs and his ilk, Chester predicted, were ready to flee the country and “leave their deluded followers to their fate.” “The last man in the Confederacy is now in the Army,” General Grant wrote. “They are becoming discouraged, their men deserting, dying and being killed and captured every day.”

The Union in this way reinforced its image as the magnanimous victor that would receive repenting rebels with fraternal compassion as soon as they abandoned their mistaken cause. The widely publicized reunion between Generals Grant and Longstreet was an example. Whereas Longstreet had feared Grant would hang him, the Union General received his old friend warmly, inviting him to smoke and play brag. “How my heart swells out to such a magnanimous touch of humanity!” Longstreet exclaimed. “Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?” The captured General Albert Sydney Johnston, who had spent years uncommunicated in a Kansas prison waiting for a war crimes trial, was given clemency in exchange of denouncing the Junta. Having genuinely admired both Davis and Breckinridge, Johnston proceeded to lambast the architects of the Coup as “the worst villains the world has ever known . . . never surpassed in their baseness and treachery.” Neither former Confederate accepted to give up military intelligence or any more substantial help, but their mere declarations helped to emphasize the point that the Union was better and more merciful than the Confederacy.

The Junta opposed this narrative and tried to emphasize the Union’s supposed vengeful tyranny. The “people who lately called us brethren” were “insatiable for our blood” they claimed. The re-election of Lincoln, “a vulgar buffoon” who was more despotic than “King, Emperor, Czar, Kaiser, or even Caesar himself” only proved that resistance to the last was their only alternative. They further reprinted resolutions that proclaimed that the soldiers, in view that “the enemy is still invading our soil with the original purpose of our subjugation or annihilation . . . are determined to follow whenever Robert Toombs directs or General Jackson leads.” Another boasted that the Army of Northern Virginia still had “60,000 of the best soldiers in the world and they have unbounded confidence in Jackson . . . we will storm Grant in his breastworks if they were twice as strong.” But whispered doubts kept multiplying. A soldier, before deserting, wrote that it was “better to eat side by side with a Negro than hang side by side with Toombs.” An officer too admitted that “the wolf is at the door . . . we dread starvation far more than we do Grant or Sherman. Famine – that is the word now.”

Junta repression

It was the word, indeed - the feared famine had at last come. The circumstances heretofore described had been present since at least late 1863, but as the unusually cold and wet winter of 1864-1865 arrived, Southerners found themselves with their food stores exhausted, their network of transportation devastated, and either insufficient relief efforts or no efforts at all. Unable to raise food quickly enough in plantations that had been cleaned and razed by guerrillas or marching soldiers, and with both Yankees and Rebels still seizing most sustenance, the Southern countryside started to starve. The Southern Famine of 1864-1865 claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and would not be controlled until after the war ended and the Union was able to establish large-scale relief efforts. The areas that were hit the hardest were the Mississippi interior, Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia, where Union offensives in 1864 or early 1865 all destroyed Confederate public authority but were unable to establish Federal power quickly enough. Sorry tales of suffering abounded, as desperate people tried to eat still green maize and potatoes, Yankees found towns populated only by skeletal women and children, and people dropped by the wayside while looking for anything to eat.

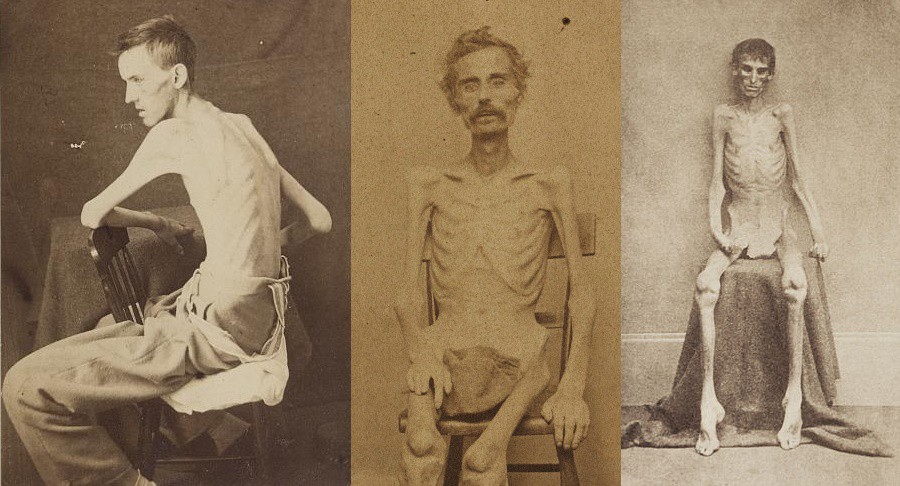

While the popular imagination has seen the famine as something that mostly affected poor rural Whites, in truth the situation grew just as desperate in cities. John Jones confessed that his wife and children were “emaciated” and that they had had no choice but to eat the rats they found in his home. When Union forces finally took Columbia, South Carolina, they found it a desolated town, full of the corpses of starved people. Likewise, the famine killed proportionally as many Black people, both freedmen who had seized plantations but were then unable to raise enough food, and enslaved people whose rations were the first to be cut in the face of hunger. Another victim of the famine were Yankee prisoners of war, who had already been receiving extremely meager rations and then received nothing as the food supply dried out. When Sherman’s soldiers liberated the infamous Andersonville, they were “sickened and infuriated” at seeing their comrades reduced to mere bones “in the midst of . . . barns bursting with grain and food to feed a dozen armies.” There, the Yankees learned a hard lesson when they hastily fed the prisoners, only to see them die due to the little understood at the time refeeding syndrome.

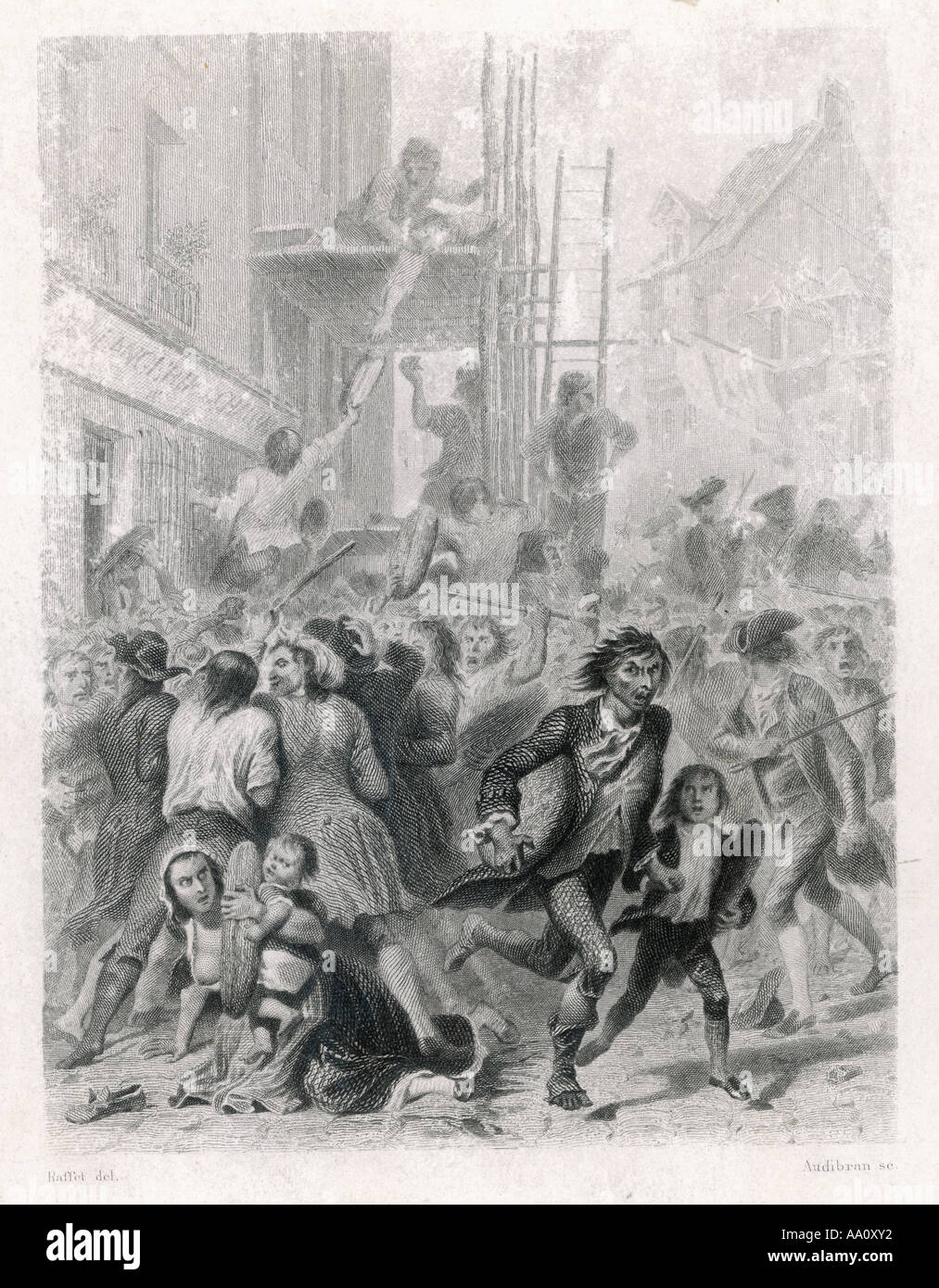

Abandoned, angered, hungry, and despairing, the Southern people started a series of “Jacqueries” that quickly eclipsed the violence of the 1863 Bread Riots. Throughout the South, poor Whites revolted against Confederate authority, seeking food and an end to repression. Like before, women were conspicuous as the leaders of these revolts. In Raleigh, women marched for “the right to live,” breaking into stores to seize bread and flour; in Lynchburg, the stores of “speculators” were sacked and burned. In Union-occupied Mobile, the women cried “bread or blood” and attacked the local Bureau office after the Federals were unable to bring in enough food. But, unlike the mostly urban outbreaks of 1863, now the insurrection had spread like wildfire to the starving countryside. Rumors of massacre by Confederate forces or Union soldiers added to the fear and panic felt by the rural people, as well as the hope that declaring for the Union would allow them to retain seized lands and obtain food. As hunger spread, so did dissent, and by the end of the year the rural South was burning.

This had now become a direct assault on the social order of the South, which secession had sought to preserve and which the rebel armies had imposed. As these armies retreated and public authority collapsed, the communities started to “impress” the food stores the wealthy had been hoarding, drove away or killed tax collectors and Army officers, and took plantations and Army depots for themselves. Wild rumors circulated, of rape, murder, and even cannibalism. A South Carolina teacher wrote that “we are submerged in the most horrible anxiety and dismay. The crops do not ripen, and all have heard of revolts and massacre.” Bitterly crying “down with the slaveholders’ war!” or “we can’t eat cotton!” they fully intended to destroy the planter aristocracy that they blamed for the famine. The particularly odious James H. Hammond, who had raped his nieces even as he boasted of Southern refinement and called Northerners mudsills, was even lynched by a mob. Sarah Espy, on the other hand, shuddered as she remembered how a friend had been decapitated by “brigands” who wanted her wheat, and Daniel Cobb wrote that a “bachelor was taken by his servants from his bead at Midnight. Carried out of the house and beat to death with an ax.”

Starved Andersonville prisoners

In popular memory, the Southern Jacquerie is remembered as the first event of widespread racial solidarity, for the poor Whites joined with the enslaved Blacks to oppose and drive away the planters. This was true, to a degree, for there are indeed reports of biracial mobs defying the Confederate authorities. Especially in areas where the Black population was a majority, the poor Whites had no choice but to join with them. However, in other communities the White insurrectionists had no interest in Black liberation and saw them just as competence for the scarce food. As a result, these are also reports of “race war” in many localities where Whites killed or drove away Black people too, or where the enslaved attacked all Whites, planter and peasant alike. It’s difficult to know which reports are true, since it was in the Confederate authorities' interest to portray the violence as merely Yankee-incited servile insurrection. Yet, as Black people too rose up to throw away their shackles and preempt the land, sometimes with White help, sometimes against them, the fears of slave revolt seemed to at last being fulfilled.

The Junta and the remaining Confederate authorities reacted with horror, outrage, and repression to this Jacquerie. Josiah Gorgas believed that the poor people’s “pretense was bread; but their motive really was license, robbery, and treason.” The Richmond Examiner for its part described all rioters as “prostitutes, professional thieves, Irish and Yankee hags and gallow birds from all lands.” Whenever they could be spared, troops were sent to areas that faced “disturbances” to quiet “servile insurrection” by shooting the rioters and hanging their leaders. Yet, the Confederate Armies were dissolving due to a combination of want and desertion, and many soldiers and militiamen could not be counted on to restore order when their wives, sisters, and mothers were part of the mobs. By 1865, the Junta had lost control of the South, only able to project power in the immediate vicinity of the armies of Northern Virginia and Georgia. Everywhere else, “anarchy” reigned, despaired a Confederate, “the social order utterly destroyed . . . the dregs of society robbing and murdering their betters with impunity.”

Even as the Confederacy collapsed around them, the members of the Confederate Junta, especially Toombs and Jackson, insisted that the war could still be won. But the military picture was still one of unending disaster. Having taken a pause due to the harsh weather conditions, Sherman resumed his Carolinas campaign in February, taking Columbia on February 27th. According to Sherman, the fires that would consume and destroy the city were started by the rebels themselves, who burned cotton bales as they retreated, starting fires that quickly spread to the liquor stores of the city. Southerners in turn blamed supposed mobs of “drunk Yankees and negroes” and their “terrible diabolism.” Whoever was to blame, Columbia was erased from the map, and Sherman’s march continued onto Goldsboro. There, Johnston finally made a desperate attempt to turn him back, suffering 70% more casualties and failing to make Sherman retreat. This threatened Jackson’s last lifeline at Raleigh, after Fort Fisher had been taken and Wilmington been closed as the last blockade-running port of the Confederacy.

With the possibility of peace completely closed off by the Coup and the repression that followed, most Southerners could only conclude that they would be, indeed, wiped off the earth as Mary Chesnut had predicted. Southern communities immersed in the bloody winter Jacquerie clamored for Federal occupation to bring food and order; politicians and soldiers continually escaped to Federal lines and begged for mercy. With Jackson still pinned in Richmond and Sherman advancing rapidly through the Carolinas, the jaws of death were closing. Or, as Lincoln said picturesquely, “Grant has the bear by the hind leg while Sherman takes off the hide.” “Disintegration is setting in rapidly,” a Colonel noted, observing how each month resulted in 8% of the Army of Northern Virginia deserting or dying. “Everything is falling to pieces.” These were “days of despondency, despair, and to all, of intense anxiety,” reported another officer. The catastrophe was even getting through to the most fanatical. In March, a young man found Toombs listlessly staring at a portrait of Washington. “Do you believe, sir, that victory is still coming?” he asked. “Victory?” Toombs scoffed. “My dear young man, victory was never a possibility. Ours was a choice between dishonorable surrender and honorable destruction. Do you not agree that dying with honor is better than living in disgrace?”

The Southern Jacquerie

This despair contrasted with the optimism and decision that characterized the Union and its leaders. Lincoln’s annual message to the Union Congress on December stroke a particularly triumphal note. “The purpose of the people . . . to maintain the integrity of the Union, was never more firm, nor more nearly unanimous, than now,” Lincoln declared. The Union’s resources “are unexhausted, and, as we believe, inexhaustible . . . We are gaining strength, and may, if need be, maintain the contest indefinitely.” Indeed, despite all privations and sacrifice, the North was producing more iron, coal, firearms, and ships than they had at the start of the war; its fields were producing more wheat, corn, pork, and beef than ever, “enough to feed our Southern brothers and all the workers of Europe,” boasted the president of an Agricultural society. Despite periods of economic uncertainty and inflation, the Northern economy actually grew, the war accelerating the mechanization of its industry and agriculture. Even as the Confederacy collapsed, the Union was just becoming stronger.

The resolve of the Northern people to see the war through was only increasing too. A British journalist was “astonished” by “the depth of determination . . . to fight to the last” that the Northern people possessed. This determination also extended to seeing the war completed by destroying the old South. To the December session of Congress, Lincoln proclaimed that the “will of the majority” had expressed in favor of a complete Reconstruction of the Union. The outlook there, too, seemed sunny. In the latter half of 1864, the military governor of Tennessee, William Brownlow, had managed to organize a loyal government under the terms of Lincoln’s Quarter Plan, getting a new Constitution approved by East Tennessee Unionists and enfranchised Black voters. In December, the new Reconstructed Tennessee ratified the 13th amendment, joining Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Reconstituted Government of Virginia. Furthermore, Lincoln announced happily, governments were being organized in Mississippi and Alabama along the same lines, which could be expected to submit constitutions to the voters and ratify the 13th amendment soon. As soon as they did, the amendment would become part of the Constitution.

With victory clearly in sight, when the December session opened Congressional Republicans reported several bills to try and establish a Reconstruction plan. The initial bill by Representative Ashley recognized Louisiana and Tennessee but required all other Southern States to use an “ironclad” standard of loyalty, and for the constitutions to be ratified by at least 50% of eligible voters. More importantly, the bill called for universal Black suffrage and equal access to juries and offices. The Radicals grumbled that the admission of Louisiana and Tennessee “ought not to be done,” but given that Black suffrage was “an immense political act,” they were willing to accept it at first. But Lincoln still wished to remain in control of the Reconstruction process, and as a result most of the Congressmen aligned with him rejected any bill that went farther than merely recognizing his State governments. The US government, Henry Winter Davis denounced, had become one of “personal will. Congress has dwindled from a power to dictate law and policy to a commission . . . to enable the Executive to execute his will and not ours.” Yet, having been just reelected by a great majority of the people, Lincoln seemed too powerful to oppose. “A.L. has just now all the great offices to give afresh and can’t be resisted,” a Congressman told Wendell Phillips. “He is dictator.”

Many men who had once opposed Lincoln, Senator Wade complained, had undergone “the most miraculous conversion . . . since St. Paul’s time” and were now supporting him wholeheartedly in pushing for Louisiana’s admission. But Radicals joined to filibuster the proposal as long as it did not include any measures for the Reconstruction of the other States that, at the very least, would guarantee “equality of civil rights before the law . . . to all persons.” Denouncing the “pretend State government in Louisiana” as a “seven months abortion, begotten by the bayonet in criminal conjunction with the spirit of caste, and born . . . rickety, unformed, unfinished,” Sumner kept the filibuster until the Moderates gave in and retook Ashley’s bill. Adopting wider civil protections to please the Radicals and dropping most provisions regarding Reconstruction to please the President, the bill was transformed into the Civil Rights Act of 1865. The most important provisions were the protections of Black people’s rights to serve in juries, hold office, sue in court, and above all to be considered equal before all laws, including suffrage qualifications. An attempt to amend it to include universal Black suffrage again failed, and, faced with the prospect of getting no bill at all, Radicals decided to accept. This was the final bill passed by the 38th US Congress.

Lincoln briefly considered pocket vetoing the bill since it had, after all, not included the admission of Louisiana and Tennessee as he had wanted. But it hadn’t infringed on his power over Reconstruction either, and Lincoln could be confident that the next Congress, with its even bigger Republican majority, would accept his governments. Moreover, he remarked, the bill merely executed the provisions of the amendment – never mind that it technically hadn’t been ratified yet. Lincoln signed the bill on March 3rd, showing yet again to both North and South his commitment to remaking the conquered South. The next day, he made the message even clearer at his Second Inaugural. Standing before a Black and White crowd, with prominent Black abolitionists like Douglass and Tubman as guests, and a company of the 54th Massachusetts as part of the Presidential Guard, Lincoln gave a remarkable speech, justly engraved in the national memory as one of the greatest in American history.

Lincoln's Second Inaugural

The war, Lincoln asserted unambiguously, had been started by the South to protect the “peculiar and powerful interest” that slavery constituted, an interest they sought to “strengthen, perpetuate, and extend.” “All dreaded” war, “all sought to avert it,” yet one party “would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let the nation perish.” Both sections had then invoked the same God, even if “it may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces.” But this was not a mere political conflict. “The Almighty has His own purposes,” Lincoln declared, giving “to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came.” In this way, Elizabeth R. Varon writes, Lincoln sought to “place the war effort on a moral plane that transcended electoral politics. He cast disunion as the chastisement and purification not just of the South but of the whole sin-soaked and guilt-ridden nation.” The war was then a glorious, necessary struggle, but also just punishment for the centuries of oppression Southerners had inflicted and Northerners had abetted. When, then, would it end? And what would happen once peace came? Answered Lincoln:

The address was “not immediately popular,” Lincoln recognized later with some amusement, for “Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them,” but it would “wear as well – perhaps better than – anything I have produced.” Frederick Douglass recognized the brilliance of the speech as soon as he heard it, calling it a “sacred effort.” Lincoln’s words, the Washington National Intelligencer said, were “equally distinguished for patriotism, statesmanship, and benevolence” and deserved to “be printed in gold, and engraved in the heart of every American.” In casting the war for the Union as one with divine, moral significance, as punishment for the nation’s sins and a struggle for its redemption, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural had firmly committed the United States to victory and Reconstruction no matter what, no matter if the ruin and destruction had to go on for many years more.

General Grant, however, was already working to end the war that same year. The siege of Peterburg and Richmond had been going on for months, and the rapid disintegration of the rebel Army induced Grant to hope he could obtain its surrender, or keep it trapped until Sherman appeared on its rear. But he feared that if Jackson could slip out of Richmond, “the war might be prolonged another year.” The leaders of the Confederacy were starting to realize that this was their last remaining possibility – to acknowledge yet again that Breckinridge had been right, when the deposed President had declared Richmond untenable and wanted to link up with the Army of Georgia. Now, a much weaker Army of Northern Virginia would have to make the move through a Southern countryside still rocked by famine and the Jacquerie. Yet Generals Jackson and Beauregard resisted this inexorable conclusion, believing that a grandiose counterattack could yet push Grant away from Richmond. To try and implement these plans, the Junta continued to impress boys as young as 12 to man the trenches and plundered the Virginia countryside to feed the Army.

Grant, however, recognized the weakness of the Southerners. A couple of weeks earlier he, General Sherman, Admiral Porter, and President Lincoln had met aboard the steamer River Queen. The encirclement of Petersburg was almost complete, Grant announced, and after it happened Richmond could not be held. Lincoln worried that Jackson would then escape to join Johnston, but Sherman assured him that Johnston’s own army was almost defeated and that, moreover, Jackson could easily be crushed between his hammer and Grant’s anvil. But Grant was decided to finish the work right there and then, believing the Army of the Susquehanna ought to “defeat their old foe” without Sherman’s help. On April 14th, Grant’s Army attacked the Confederate position at Five Forks, which was easily overtaken despite desperate rebel resistance. At first, Jackson absolutely refused to abandon Richmond, writing that doing so would be to abandon the memory of General Lee.

Battle of Five Forks

But the Junta finally had to acknowledge the inevitable after the Jacquerie found its climax in the riots that engulfed a starved Richmond. That day, just like during the first Bread Riots, emaciated women broke into stores and demanded food. In 1863, Breckinridge had appeared before the mob and empathized with their suffering, opening the food stores. In 1865, Toombs did not bother to make an appearance, and instead send in militia units to try and control the riot. Whether Toombs ordered them to shoot, or if like in other riots the shooting started due to scared civilians and soldiers firing, has never been settled. Yet, a massacre started, and soon Richmond was submerged in violence that took dozens of lives. Toombs and most members of the Confederate government immediately fled the city. Fannie Miller, a War Department worker, saw Robert G.H. Kean fleeing with documents, and asked if she, too, should leave. Kean answered sadly: “I cannot advise a lady to follow a fugitive government.” Despairing, she barricaded herself in home and observed as the Army of Northern Virginia evacuated and Richmond descended into anarchy.

“Hell itself had broken loose,” reported a civilian as abandoned ammunition magazines exploded and liquor went up in flames, while the people took to looting in a desperate search for food. “O, the horrors of that night!” wrote a terrified Miller. “The rolling of vehicles, excited cries of the men, women, and children as they passed loaded with such goods as they could snatch from the burning factories and stores that were being looted by the frenzied crowds.” “Richmond was ruled by the mob,” concluded Sallie Putnam in disgust and fear. But not for long – on April 18th, exactly four years after Confederate soldiers had entered Washington and set it on fire, Union soldiers entered Richmond and worked to put off the fires. At their head were some regiments of Doubleday’s Black corps, singing “John Brown’s Body” and being received by the exultant cheers of the enslaved, who cried “Lord Bless the Yankees! Babylon has fallen!”

Watching as the freedmen “danced and shouted, men hugged each other, and women kissed,” Mary Fontaine could not help but cry, “the bitter, bitter tears coming in a torrent.” It was like “the judgement day” of the planter class and their world, she reflected. The Confederacy, Union soldier Edward H. Ripley said, had died like a “wounded wolf . . . gnawing at its own body in insensate passion and fury.” But the Unionist Elizabeth Van Lew, who had worked as a spy in the last months despite great peril, instead saw the arrival of the Federals as long-awaited liberation, the fire and anarchy that had consumed Richmond raising to the sky “as incense from the land for its deliverance.” One of the men who entered Richmond that day, the chaplain Garland White, who had been separated from his mother and sold to Robert Toombs years ago, also marveled at the “shouts of ten thousand voices” that celebrated their freedom. An elderly woman then approached him and asked him several questions, such as his name, where he was born, and the name of his mother. After he answered, the woman exclaimed amidst tears of joy: “this is your mother, Garland, whom you are now talking to, who has spent twenty years of grief about her son.”

The news of Richmond’s fall was celebrated jubilantly throughout the North. “We have passed the Red Sea of its blood, and now the promised land is in view,” a War Department officer declared as a nine-hundred-gun salute resounded in Philadelphia. But even these were eclipsed by the joy shown by Richmond’s Unionists and freedmen. When Lincoln, who had stayed in Grant’s base in the James River, heard of Richmond’s fall he said with immense relief: “Thank God I have lived to see this. It seems to me that I have been dreaming a horrid dream for four years, and now the nightmare is gone. I want to see Richmond.” As soon as he stepped into the city, Richmond’s Black people came to see him, shouting “Glory to God! Glory! The great Messiah! He’s been in my heart four long years, come to free his children from bondage.” “Overwhelmed by rare emotions,” Lincoln helped up a man who had fallen to his knees, telling him “Don't kneel to me. That is not right. You must kneel to God only, and thank Him for the liberty you will enjoy hereafter.” "Richmond has never before presented such a spectacle of jubilee," wrote T. Morris Chester from the desk that Robert Toombs had occupied mere hours before. "What a wonderful change has come over the spirit of Southern dreams!”

As a gesture of mercy, Grant had refused to enter Richmond as a triumphal conqueror, instead riding in hot pursuit of Jackson’s rapidly melting force. As he retreated, Jackson again showed the same lack of compassion that he had during his Valley campaigns, observing impassively as “hundreds of men dropped from exhaustion, and thousands let fall their muskets from inability to carry them any farther.” Yet Jackson refused to offer the hungry, tired men any respite, knowing Grant was on their heels. “I felt we ought to find Jackson and strike him,” Grant recalled later. “The question was not the occupation of Richmond, but the destruction of the army.” On April 22nd, the Federal cavalry managed to shatter a corps of infantry at Sayler’s Creek, burning desperately needed supplies and destroying a quarter of the Army of Northern Virginia. By now panicking, Jackson ordered an advance towards Danville, realizing that reaching the North Carolina border and Johnston was their last hope.

The fall of Richmond

Grant regarded this last push as almost suicidal, believing that Jackson was all-but defeated. He sent a message to Jackson, pleading with him to realize “the hopelessness of further resistance” and to stop “any further effusion of blood” by surrendering his Army. Jackson threw away the message without reading it, and then consulted with his remaining generals. Beauregard had, too, fled to Danville with a small guard, supposedly to protect Toombs and what remained of the Treasury. Instead, he was surrounded by the fanatical Early and Wade Hampton, both of whom spoke against surrender, maybe because they were wanted for war crimes. With Grant so close, if they attacked and managed to drive him away, they could open the path to the Blue Ridge Mountains and continue the struggle as guerrillas. In the morning of April 24th, Jackson rose with the sun, prayed for a couple of hours, and then ordered an attack, riding at the front of the last great Confederate charge himself. The outnumbered, exhausted rebels were unable to cause any great damage, Jackson dying in the charge, and the remnants of the once great and feared Army of Northern Virginia were then encircled and captured by the Union counterattack, except for a small detachment under Hampton.

The Battle of Appomattox had consequently ended the Army of Northern Virginia as a fighting force. As he walked amidst rebel corpses, Grant confessed that he felt “sad and depressed at the downfall of a foe who had been through terror and delusion forced to endure and suffer so much for a cause, the worst for which a people ever fought.” Grant immediately ordered all captured prisoners fed and prohibited his own soldiers from gloating, while the cavalry was sent to pursue Hampton and capture Toombs. Facing the inevitable, both Beauregard and Toombs had decided to flee the country, taking different routes. Before leaving Danville, Toombs entrusted the last remaining Confederate gold to the town’s mayor, telling him to give it to Confederate soldiers returning home, and penned a testament where he asked that his land be given to “my people” – that is, the people he had enslaved. Stopping at a starving country town for supplies, Toombs was recognized and almost lynched, even receiving a whip strike on the shoulder by a former slave. Now fleeing for his life, Toombs stumbled into a detachment of Federal cavalry. Facing death by lynching or execution by the Yankees, he preferred to shoot himself. Beauregard, however, managed to successfully escape the country, a rumor falsely saying he did it by disguising himself as a woman.

The Confederacy, it was clear, was ending. Bowing to the inevitable, Georgia Governor Brown had tried to surrender himself to General Thomas, believing that as a fellow Southerner he would be more merciful than Sherman. Instead, Thomas informed him that “you, sir, are merely an ordinary citizen accused of the crime of treason, for Georgia has no government recognized by US authority,” and took him prisoner. The fleeing Governor Vance was also arrested by Union forces, as was Alexander Stephens, who put up no resistance as Federal soldiers arrived at his Georgia home. The only organized Confederate force in the East was now Joseph Johnston’s Army, which, he admitted, was “melting away like snow before the sun.” On May 10th, he asked Sherman for terms of surrender. Initially, Sherman offered inmunity for all Confederate officials and officers and to allow the soldiers to retain their arms, to be stacked at the Confederate capitols. But Philadelphia quickly rebuffed him, ordering Sherman to demand an unconditional surrender. Under no delusions, Johnston surrendered and was taken prisoner.

The destruction of the Army of Northern Virginia, the surrender of the Army of Georgia, and the capture or death of the Junta had virtually ended organized Confederate resistance, and the Northern people replied with a wild outpour of joy. In Philadelphia, a reporter wrote, “the air seemed to burn with the bright hues of the flag . . . Almost by magic the streets were crowded with hosts of people, talking, laughing, hurrahing and shouting in the fullness of their joy. Men embraced one another, 'treated' one another, made up old quarrels, renewed old friendships, marched arm-in-arm singing.” “Guns are firing, bells ringing, flags flying, men laughing, children cheering,” said Gideon Welles; “all, all jubilant.” Lincoln himself appeared in a balcony amidst the Philadelphia celebrations, being received by “cheers upon cheers, wave after wave of applause.” He asked the bands to play “Dixie,” a tune that is “now Federal property.” The President then expressed his hopes for a “righteous and speedy peace,” yet warned that Reconstruction would be “fraught with great difficulty,” for “we, the loyal people, differ among ourselves as to the mode, manner, and means of reconstruction.” He promised that soon he would “make some new announcement to the people of the South.”

Celebrations of Union victory

While Lincoln pondered this new announcement by conferring with his Cabinet, the last remaining Confederate armies were chased and forced to surrender. Wade Hampton’s irregular band was captured in North Carolina by Sherman after Johnston’s surrender. In Tennessee, finding a shred of honor at the last moment, Forrest offered to surrender himself in exchange for immunity for his soldiers. The Federal commander refused – they all would be trialed for their atrocities. Preferring suicide to execution, Forrest imitated Jackson and charged at the Union lines, dying alongside half his force, while the other half was captured. The last large rebel detachment, under E. Kirby Smith, also tried to negotiate a surrender, but when the Yankees rebuffed him, he prepared to fight. But, knowing the cause was hopeless, his men mutinied. Smith himself would flee to Mexico with a few thousand irreconcilables, while the rest surrendered to the Union. Thus, the last organized Confederate force was dissolved, and the American Civil War came to an end.

The most disastrous part of that fiasco was the start of the Southern Famine of 1864-1865, alongside several more localized but still deadly outbreaks of disease. The reasons for the famine are several, all of them related to the war and the policies of the Union and Confederacy. The chief one was the throughout devastation of Southern agriculture and its networks of transportation. Grant’s campaigns in Tennessee and the Mississippi Valley; Rosecrans’ in Arkansas and Louisiana; Sherman’s in Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina; all of these had laid waste to the rails and canals of the South, meaning that even when food could be raised it was almost impossible to get it to where it was needed. Moreover, the Union’s adoption of a policy of land redistribution and the continuous pressure of guerrilla warfare enormously disrupted the ordinary cycles of agriculture. Many plantations were razed, and the back and forth of destruction meant that they were unable to resume their activities until a firm Union grip was established.

Yet, the coming of Union rule did not solve the problem of food scarcity. Because Northerners were interested above all in the reestablishment of antebellum crop production, the Federal authorities primarily encouraged the cultivation of cotton, feeding the people through supplies brought from the North. Alongside the division of the previous large estates, this meant a drastic decline in the production of food throughout the liberated areas. Yet another factor was that the emancipation of hundreds of thousands of enslaved people deprived plantations of desperately needed labor. In peaceful areas, women and children initially retreated from the fields; in war-thorn regions, they worked, but it was the men who were kept away as soldiers in Home Farm regiments or Union paramilitaries. The pattern of slavery was kept, in that the people focused on raising cash crops, keeping livestock and vegetable patches as merely supplementary activities, and relying on the Federals for the bulk of maize, flour, and sugar that fed them. The situation was similar in the Confederacy, where enslavers, especially after the Junta repealed all of Breckinridge’s decrees, preferred to raise cotton, believing they could take the oath as soon as the Union arrived and sell it for immense profit.

The outlook was even worse in the areas that had been devastated by recent Union campaigns. In Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina, the march of the bluecoats had resulted in plundered plantations and the consumption of food stores, as the hungry Yankees descended like locusts onto everything they found. This meant the destruction of a great amount of produce at the peak of the harvest, with the disorder than ensued assuring that no more food could be planted for a while. Even outside of the direct Federal path, poor Whites and freedmen forcibly took plantations, which too obstructed agriculture, and most of the time the food available was not enough. The Union did try to offer relief, but it severely underestimated the logistical challenge it was taking upon itself. With food stores depleted and rail networks destroyed, the Union just had no feasible way to transport enough food into the hunger-stricken counties.

Federal food relief efforts

Still another factor was the severe dislocations the Southern countryside had suffered as a result of guerrilla warfare, Union expulsions, and the tide of refugees. All of these resulted in hundreds of thousands of people fleeing their homes and farms and gathering either in overcrowded Union camps or war-swollen Southern cities. Cities like Richmond and Columbia struggled to feed both armies and civilians, effectively meaning that soldiers competed with common people for dwindling supplies – and in this, a soldier with a gun had the upper hand over defenseless women and children. This created a situation where refugees would flood particular points for food, and then fan across the countryside, surviving meagerly in the meantime. This contributed to the spread of deadly diseases, as the emergency infrastructure erected just was unable to hold all the people in hygienic conditions. For example, the depot the Union established in Atlanta was expected to aid only 10,000 people – over 30,000 refugees crowded it instead.

Epidemics of yellow fever in the Mississippi Valley, Georgia, and the Carolinas; of scarlet fever in Pennsylvania and the Lower North; and of smallpox in Tennessee and the Border States, all claimed thousands of lives. When people gathered into hastily organized Army camps to try and stave off famine, they found, just like the soldiers who mustered in 1861-1862, that disease could be the greatest killer. The response of the Bureaus was ineffective, mostly because dismantling the camps would mean not feeding the hungry people. With winter coming and the crops still not ready to be harvested, this was not to be thought of. Instead, Bureau agents tried desperately to improve the camps, build more, and establish a presence in the countryside. But the Bureau was still entirely dependent upon the Army, which, still on a wartime footing, only established few supply depots and had most of its personal tied up in anti-guerrilla and supply guarding duties. Consequently, there were very few soldiers who could carry the sustenance into the countryside, and the Union struggled to get enough to feed all this people and its soldiers. For example, General Thomas received 45,000 pounds of meat per week for the Atlanta civilians, when in reality he needed 45,000 pounds per day.

The situation was even more critical in the Confederacy. Whereas Breckinridge had attempted an organized national response to widespread hunger through his food-relief corps and several decrees that forced the planting of foodstuffs, the Junta had repealed his programs. Instead, the task of averting famine fell upon the State governments. Georgia Governor Brown tried his hardest to help the poor, distributing salt and wheat to the hungry, but after Sherman’s march his State government was basically defunct. This meant that the civilians had to be fed by the Union, resulting in the problems already described, since the Federals had neither the infrastructure nor the men to establish an effective food supply for the thousands of refugees in cities like Savanah and Mobile. Those who remained under Confederate control fared even worse, for the Junta never established any mechanisms of food relief, and the State governments were powerless to intervene. Thus, while civilians in Union-held areas faced insufficient relief, civilians in Confederate areas had no relief at all.

The lack of resources could also be explained by the ever-tightening noose of the blockade, which by now was so effective that few ships could bypass it. Furthermore, the informal trade between lines had also largely stopped, partly because of a reluctance to trade with the Junta, partly because the rebels lacked the specie to pay for Northern products. Without the salt and foodstuffs that had been entering through the lines and the blockade, the situation was growing direr. Moreover, the disastrous inflation the Confederacy had been suffering had been only worsened by the Coup. Since the Confederate grayback had been effectively backed by public confidence in victory, the latest defeats had rendered it worthless. In the cities where food could still be found, the joke went, “shoppers took their money to the market in bushel baskets and returned with their purchases in their pocketbooks.” In other localities the graybacks replaced timber in fireplaces, in a desperate attempt to keep warm.

Even more disastrously, the rebel armies continued and intensified their policies of forced impressment and scorched earth. By then reduced by desertion and defeat to “little more than a band of marauders” in the words of one of them, the Confederate soldiers despoiled their own civilians of foodstuffs and destroyed plantations and resources before Sherman could do it. To bolster their ranks, they engaged in a strategy of forced recruitment, with entire towns remembering bands of “the worst cutthroats and savages” arriving and taking every male over thirteen years. This, too, disrupted agriculture, for the farms were left without men to reap the harvest or plant a new crop. Resistance could result in abominable reprisals, such as the summary execution of draft-dodgers or even massacres in localities that tried to resist them. A South Carolina deserter who tried to hide his grain, for example, was hung in front of his horrified wife and children. The Junta that had formed partly in reaction to Breckinridge’s so-called “monstrous” policies of impressment were now just engaging in an even more pitiless policy.

Refugee camps

In truth, it’s difficult to know how much of these actions were done under the orders or even with the knowledge of the Junta, given how the Coup just resulted in a breakdown of the centralized war-effort Breckinridge had instituted. With no real control from Richmond, Confederate armies became irregular forces that victimized vulnerable Southerners. Yet, the Junta never even tried to restrain its soldiers or formulate an organized response to these calamitous circumstances. Instead, the official orders and pronouncements that were there consistently called for greater and more ruthless terror against dissidents and “defeatists.” Senator Graham thus was executed after he was found hatching a second peace scheme, and Breckinridge’s Secretaries all were shot in the middle of the night after secret summary trials. Senator Wigfall, too, was never seen again after his arrest. In Western North Carolina, the greatest and most horrific consequence was the massacre of around 80 men, women, and children in the town of Hillsborough, Holden’s birthplace, after it tried to secede in imitation of Mississippi’s Free State of Jones. Appallingly, even as the manpower situation grew critical in several areas, the Junta also found men to spare to send them to “maintain order” in plantations, which often meant massacring and torturing Black people.

Seeing hunger and repression at home, desertions sharply increased in the Confederate Armed forces. A despairing wife for example wrote to her husband “Our son is lying at death’s door, his hunger unbearable, his earnest calls for Pa breaking my heart. John, come home!” Under Breckinridge the government had tried to use the carrot instead of the stick, distributing bounties and pardons. Breckinridge had even personally pardoned many deserters. But now the Junta tolerated no such weakness. “Thoughtless and imprudent letters” that “may lead to discontent, desertion,” were censored to avoid “defeatist” messages, and executions of deserters rose dramatically. So did the efforts to resist them – for example, a mutinous North Carolina company ended up shooting death their officers. Governor Vance described in despair how these men “now bring with them Government arms and ammunitions . . . the bands of deserters now outnumber the home guards.” Thousands of men were placed behind Confederate lines to shoot deserters instead of Yankees. But, Benjamin Justice testified, “The men on the picket line fire off their guns in the air & will not try to shoot down those who are in the act of deserting to the enemy.”

That enemy now seemed more merciful than their own government. Rebels were now “fast leaving the sinking ship” by the thousands, reported the New York Times, availing themselves of the Federals’ food and warmth in exchange of taking the oath. “We have the pleasure of greeting many of the prodigal sons of Father Abraham, who, having repented, are returning honorably to worship at the shrine of their former devotion,” reported the Black correspondent Thomas Morris Chester. Southerners were “disgusted with the rebel authorities for continuing a struggle in which no one has the sightless prospect of success . . . merely to save the most guilty from the impending penalties.” Toombs and his ilk, Chester predicted, were ready to flee the country and “leave their deluded followers to their fate.” “The last man in the Confederacy is now in the Army,” General Grant wrote. “They are becoming discouraged, their men deserting, dying and being killed and captured every day.”

The Union in this way reinforced its image as the magnanimous victor that would receive repenting rebels with fraternal compassion as soon as they abandoned their mistaken cause. The widely publicized reunion between Generals Grant and Longstreet was an example. Whereas Longstreet had feared Grant would hang him, the Union General received his old friend warmly, inviting him to smoke and play brag. “How my heart swells out to such a magnanimous touch of humanity!” Longstreet exclaimed. “Why do men fight who were born to be brothers?” The captured General Albert Sydney Johnston, who had spent years uncommunicated in a Kansas prison waiting for a war crimes trial, was given clemency in exchange of denouncing the Junta. Having genuinely admired both Davis and Breckinridge, Johnston proceeded to lambast the architects of the Coup as “the worst villains the world has ever known . . . never surpassed in their baseness and treachery.” Neither former Confederate accepted to give up military intelligence or any more substantial help, but their mere declarations helped to emphasize the point that the Union was better and more merciful than the Confederacy.

The Junta opposed this narrative and tried to emphasize the Union’s supposed vengeful tyranny. The “people who lately called us brethren” were “insatiable for our blood” they claimed. The re-election of Lincoln, “a vulgar buffoon” who was more despotic than “King, Emperor, Czar, Kaiser, or even Caesar himself” only proved that resistance to the last was their only alternative. They further reprinted resolutions that proclaimed that the soldiers, in view that “the enemy is still invading our soil with the original purpose of our subjugation or annihilation . . . are determined to follow whenever Robert Toombs directs or General Jackson leads.” Another boasted that the Army of Northern Virginia still had “60,000 of the best soldiers in the world and they have unbounded confidence in Jackson . . . we will storm Grant in his breastworks if they were twice as strong.” But whispered doubts kept multiplying. A soldier, before deserting, wrote that it was “better to eat side by side with a Negro than hang side by side with Toombs.” An officer too admitted that “the wolf is at the door . . . we dread starvation far more than we do Grant or Sherman. Famine – that is the word now.”

Junta repression

It was the word, indeed - the feared famine had at last come. The circumstances heretofore described had been present since at least late 1863, but as the unusually cold and wet winter of 1864-1865 arrived, Southerners found themselves with their food stores exhausted, their network of transportation devastated, and either insufficient relief efforts or no efforts at all. Unable to raise food quickly enough in plantations that had been cleaned and razed by guerrillas or marching soldiers, and with both Yankees and Rebels still seizing most sustenance, the Southern countryside started to starve. The Southern Famine of 1864-1865 claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and would not be controlled until after the war ended and the Union was able to establish large-scale relief efforts. The areas that were hit the hardest were the Mississippi interior, Alabama, Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia, where Union offensives in 1864 or early 1865 all destroyed Confederate public authority but were unable to establish Federal power quickly enough. Sorry tales of suffering abounded, as desperate people tried to eat still green maize and potatoes, Yankees found towns populated only by skeletal women and children, and people dropped by the wayside while looking for anything to eat.

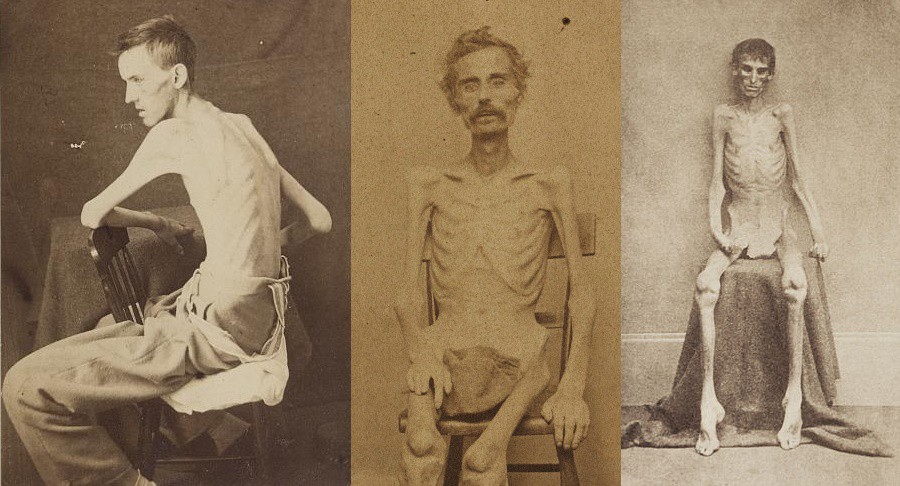

While the popular imagination has seen the famine as something that mostly affected poor rural Whites, in truth the situation grew just as desperate in cities. John Jones confessed that his wife and children were “emaciated” and that they had had no choice but to eat the rats they found in his home. When Union forces finally took Columbia, South Carolina, they found it a desolated town, full of the corpses of starved people. Likewise, the famine killed proportionally as many Black people, both freedmen who had seized plantations but were then unable to raise enough food, and enslaved people whose rations were the first to be cut in the face of hunger. Another victim of the famine were Yankee prisoners of war, who had already been receiving extremely meager rations and then received nothing as the food supply dried out. When Sherman’s soldiers liberated the infamous Andersonville, they were “sickened and infuriated” at seeing their comrades reduced to mere bones “in the midst of . . . barns bursting with grain and food to feed a dozen armies.” There, the Yankees learned a hard lesson when they hastily fed the prisoners, only to see them die due to the little understood at the time refeeding syndrome.

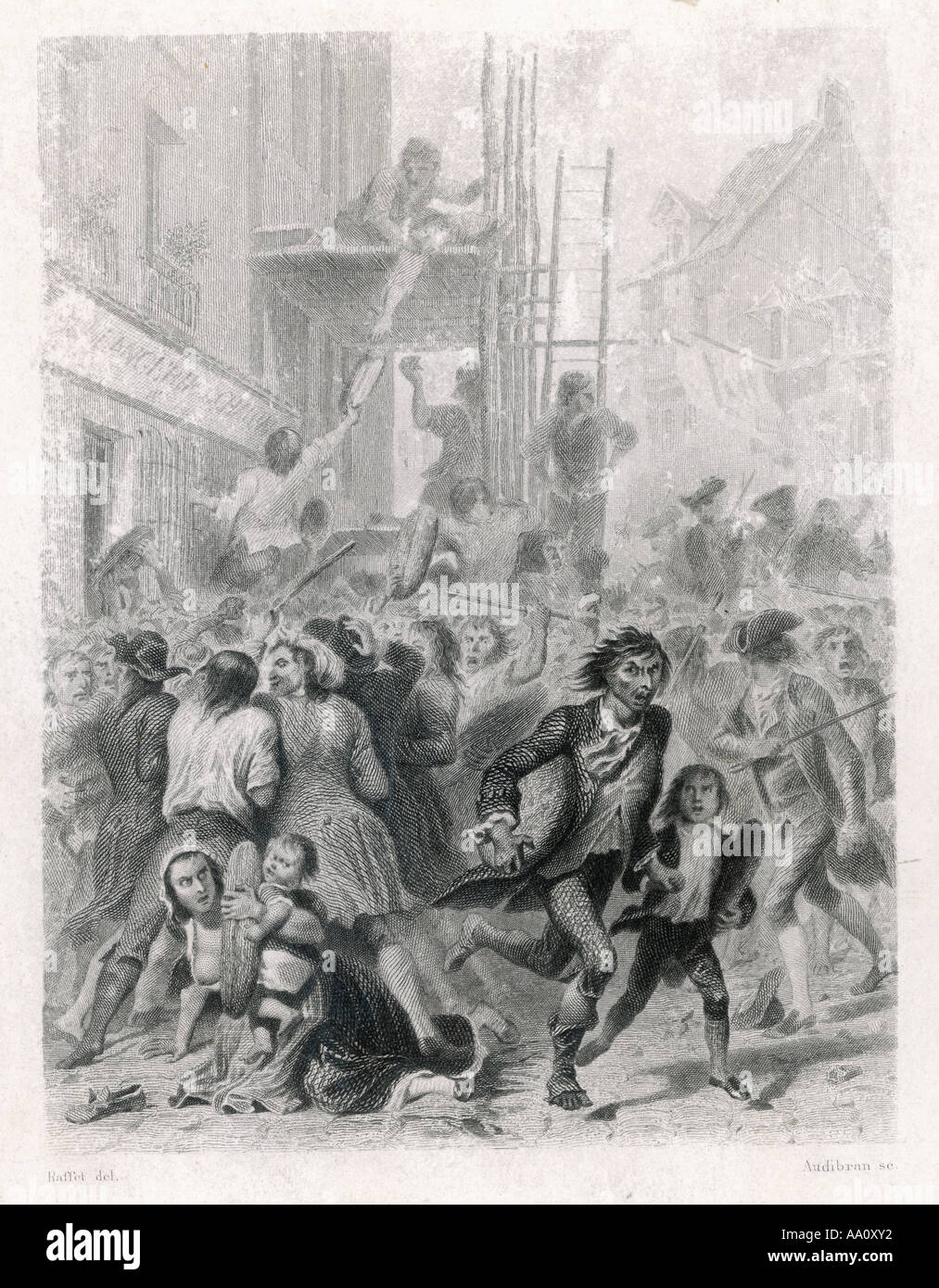

Abandoned, angered, hungry, and despairing, the Southern people started a series of “Jacqueries” that quickly eclipsed the violence of the 1863 Bread Riots. Throughout the South, poor Whites revolted against Confederate authority, seeking food and an end to repression. Like before, women were conspicuous as the leaders of these revolts. In Raleigh, women marched for “the right to live,” breaking into stores to seize bread and flour; in Lynchburg, the stores of “speculators” were sacked and burned. In Union-occupied Mobile, the women cried “bread or blood” and attacked the local Bureau office after the Federals were unable to bring in enough food. But, unlike the mostly urban outbreaks of 1863, now the insurrection had spread like wildfire to the starving countryside. Rumors of massacre by Confederate forces or Union soldiers added to the fear and panic felt by the rural people, as well as the hope that declaring for the Union would allow them to retain seized lands and obtain food. As hunger spread, so did dissent, and by the end of the year the rural South was burning.

This had now become a direct assault on the social order of the South, which secession had sought to preserve and which the rebel armies had imposed. As these armies retreated and public authority collapsed, the communities started to “impress” the food stores the wealthy had been hoarding, drove away or killed tax collectors and Army officers, and took plantations and Army depots for themselves. Wild rumors circulated, of rape, murder, and even cannibalism. A South Carolina teacher wrote that “we are submerged in the most horrible anxiety and dismay. The crops do not ripen, and all have heard of revolts and massacre.” Bitterly crying “down with the slaveholders’ war!” or “we can’t eat cotton!” they fully intended to destroy the planter aristocracy that they blamed for the famine. The particularly odious James H. Hammond, who had raped his nieces even as he boasted of Southern refinement and called Northerners mudsills, was even lynched by a mob. Sarah Espy, on the other hand, shuddered as she remembered how a friend had been decapitated by “brigands” who wanted her wheat, and Daniel Cobb wrote that a “bachelor was taken by his servants from his bead at Midnight. Carried out of the house and beat to death with an ax.”

Starved Andersonville prisoners

In popular memory, the Southern Jacquerie is remembered as the first event of widespread racial solidarity, for the poor Whites joined with the enslaved Blacks to oppose and drive away the planters. This was true, to a degree, for there are indeed reports of biracial mobs defying the Confederate authorities. Especially in areas where the Black population was a majority, the poor Whites had no choice but to join with them. However, in other communities the White insurrectionists had no interest in Black liberation and saw them just as competence for the scarce food. As a result, these are also reports of “race war” in many localities where Whites killed or drove away Black people too, or where the enslaved attacked all Whites, planter and peasant alike. It’s difficult to know which reports are true, since it was in the Confederate authorities' interest to portray the violence as merely Yankee-incited servile insurrection. Yet, as Black people too rose up to throw away their shackles and preempt the land, sometimes with White help, sometimes against them, the fears of slave revolt seemed to at last being fulfilled.

The Junta and the remaining Confederate authorities reacted with horror, outrage, and repression to this Jacquerie. Josiah Gorgas believed that the poor people’s “pretense was bread; but their motive really was license, robbery, and treason.” The Richmond Examiner for its part described all rioters as “prostitutes, professional thieves, Irish and Yankee hags and gallow birds from all lands.” Whenever they could be spared, troops were sent to areas that faced “disturbances” to quiet “servile insurrection” by shooting the rioters and hanging their leaders. Yet, the Confederate Armies were dissolving due to a combination of want and desertion, and many soldiers and militiamen could not be counted on to restore order when their wives, sisters, and mothers were part of the mobs. By 1865, the Junta had lost control of the South, only able to project power in the immediate vicinity of the armies of Northern Virginia and Georgia. Everywhere else, “anarchy” reigned, despaired a Confederate, “the social order utterly destroyed . . . the dregs of society robbing and murdering their betters with impunity.”

Even as the Confederacy collapsed around them, the members of the Confederate Junta, especially Toombs and Jackson, insisted that the war could still be won. But the military picture was still one of unending disaster. Having taken a pause due to the harsh weather conditions, Sherman resumed his Carolinas campaign in February, taking Columbia on February 27th. According to Sherman, the fires that would consume and destroy the city were started by the rebels themselves, who burned cotton bales as they retreated, starting fires that quickly spread to the liquor stores of the city. Southerners in turn blamed supposed mobs of “drunk Yankees and negroes” and their “terrible diabolism.” Whoever was to blame, Columbia was erased from the map, and Sherman’s march continued onto Goldsboro. There, Johnston finally made a desperate attempt to turn him back, suffering 70% more casualties and failing to make Sherman retreat. This threatened Jackson’s last lifeline at Raleigh, after Fort Fisher had been taken and Wilmington been closed as the last blockade-running port of the Confederacy.

With the possibility of peace completely closed off by the Coup and the repression that followed, most Southerners could only conclude that they would be, indeed, wiped off the earth as Mary Chesnut had predicted. Southern communities immersed in the bloody winter Jacquerie clamored for Federal occupation to bring food and order; politicians and soldiers continually escaped to Federal lines and begged for mercy. With Jackson still pinned in Richmond and Sherman advancing rapidly through the Carolinas, the jaws of death were closing. Or, as Lincoln said picturesquely, “Grant has the bear by the hind leg while Sherman takes off the hide.” “Disintegration is setting in rapidly,” a Colonel noted, observing how each month resulted in 8% of the Army of Northern Virginia deserting or dying. “Everything is falling to pieces.” These were “days of despondency, despair, and to all, of intense anxiety,” reported another officer. The catastrophe was even getting through to the most fanatical. In March, a young man found Toombs listlessly staring at a portrait of Washington. “Do you believe, sir, that victory is still coming?” he asked. “Victory?” Toombs scoffed. “My dear young man, victory was never a possibility. Ours was a choice between dishonorable surrender and honorable destruction. Do you not agree that dying with honor is better than living in disgrace?”

The Southern Jacquerie

This despair contrasted with the optimism and decision that characterized the Union and its leaders. Lincoln’s annual message to the Union Congress on December stroke a particularly triumphal note. “The purpose of the people . . . to maintain the integrity of the Union, was never more firm, nor more nearly unanimous, than now,” Lincoln declared. The Union’s resources “are unexhausted, and, as we believe, inexhaustible . . . We are gaining strength, and may, if need be, maintain the contest indefinitely.” Indeed, despite all privations and sacrifice, the North was producing more iron, coal, firearms, and ships than they had at the start of the war; its fields were producing more wheat, corn, pork, and beef than ever, “enough to feed our Southern brothers and all the workers of Europe,” boasted the president of an Agricultural society. Despite periods of economic uncertainty and inflation, the Northern economy actually grew, the war accelerating the mechanization of its industry and agriculture. Even as the Confederacy collapsed, the Union was just becoming stronger.

The resolve of the Northern people to see the war through was only increasing too. A British journalist was “astonished” by “the depth of determination . . . to fight to the last” that the Northern people possessed. This determination also extended to seeing the war completed by destroying the old South. To the December session of Congress, Lincoln proclaimed that the “will of the majority” had expressed in favor of a complete Reconstruction of the Union. The outlook there, too, seemed sunny. In the latter half of 1864, the military governor of Tennessee, William Brownlow, had managed to organize a loyal government under the terms of Lincoln’s Quarter Plan, getting a new Constitution approved by East Tennessee Unionists and enfranchised Black voters. In December, the new Reconstructed Tennessee ratified the 13th amendment, joining Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Reconstituted Government of Virginia. Furthermore, Lincoln announced happily, governments were being organized in Mississippi and Alabama along the same lines, which could be expected to submit constitutions to the voters and ratify the 13th amendment soon. As soon as they did, the amendment would become part of the Constitution.

With victory clearly in sight, when the December session opened Congressional Republicans reported several bills to try and establish a Reconstruction plan. The initial bill by Representative Ashley recognized Louisiana and Tennessee but required all other Southern States to use an “ironclad” standard of loyalty, and for the constitutions to be ratified by at least 50% of eligible voters. More importantly, the bill called for universal Black suffrage and equal access to juries and offices. The Radicals grumbled that the admission of Louisiana and Tennessee “ought not to be done,” but given that Black suffrage was “an immense political act,” they were willing to accept it at first. But Lincoln still wished to remain in control of the Reconstruction process, and as a result most of the Congressmen aligned with him rejected any bill that went farther than merely recognizing his State governments. The US government, Henry Winter Davis denounced, had become one of “personal will. Congress has dwindled from a power to dictate law and policy to a commission . . . to enable the Executive to execute his will and not ours.” Yet, having been just reelected by a great majority of the people, Lincoln seemed too powerful to oppose. “A.L. has just now all the great offices to give afresh and can’t be resisted,” a Congressman told Wendell Phillips. “He is dictator.”

Many men who had once opposed Lincoln, Senator Wade complained, had undergone “the most miraculous conversion . . . since St. Paul’s time” and were now supporting him wholeheartedly in pushing for Louisiana’s admission. But Radicals joined to filibuster the proposal as long as it did not include any measures for the Reconstruction of the other States that, at the very least, would guarantee “equality of civil rights before the law . . . to all persons.” Denouncing the “pretend State government in Louisiana” as a “seven months abortion, begotten by the bayonet in criminal conjunction with the spirit of caste, and born . . . rickety, unformed, unfinished,” Sumner kept the filibuster until the Moderates gave in and retook Ashley’s bill. Adopting wider civil protections to please the Radicals and dropping most provisions regarding Reconstruction to please the President, the bill was transformed into the Civil Rights Act of 1865. The most important provisions were the protections of Black people’s rights to serve in juries, hold office, sue in court, and above all to be considered equal before all laws, including suffrage qualifications. An attempt to amend it to include universal Black suffrage again failed, and, faced with the prospect of getting no bill at all, Radicals decided to accept. This was the final bill passed by the 38th US Congress.

Lincoln briefly considered pocket vetoing the bill since it had, after all, not included the admission of Louisiana and Tennessee as he had wanted. But it hadn’t infringed on his power over Reconstruction either, and Lincoln could be confident that the next Congress, with its even bigger Republican majority, would accept his governments. Moreover, he remarked, the bill merely executed the provisions of the amendment – never mind that it technically hadn’t been ratified yet. Lincoln signed the bill on March 3rd, showing yet again to both North and South his commitment to remaking the conquered South. The next day, he made the message even clearer at his Second Inaugural. Standing before a Black and White crowd, with prominent Black abolitionists like Douglass and Tubman as guests, and a company of the 54th Massachusetts as part of the Presidential Guard, Lincoln gave a remarkable speech, justly engraved in the national memory as one of the greatest in American history.

Lincoln's Second Inaugural

The war, Lincoln asserted unambiguously, had been started by the South to protect the “peculiar and powerful interest” that slavery constituted, an interest they sought to “strengthen, perpetuate, and extend.” “All dreaded” war, “all sought to avert it,” yet one party “would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let the nation perish.” Both sections had then invoked the same God, even if “it may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces.” But this was not a mere political conflict. “The Almighty has His own purposes,” Lincoln declared, giving “to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came.” In this way, Elizabeth R. Varon writes, Lincoln sought to “place the war effort on a moral plane that transcended electoral politics. He cast disunion as the chastisement and purification not just of the South but of the whole sin-soaked and guilt-ridden nation.” The war was then a glorious, necessary struggle, but also just punishment for the centuries of oppression Southerners had inflicted and Northerners had abetted. When, then, would it end? And what would happen once peace came? Answered Lincoln: