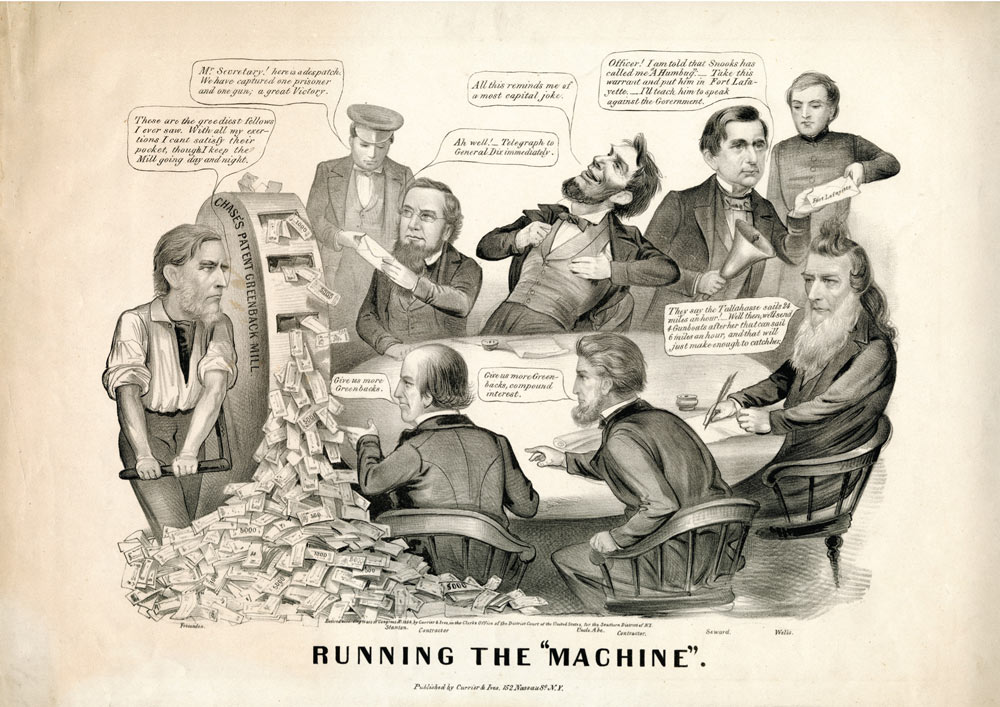

Chapter 19: And roll on the Liberty Ball!

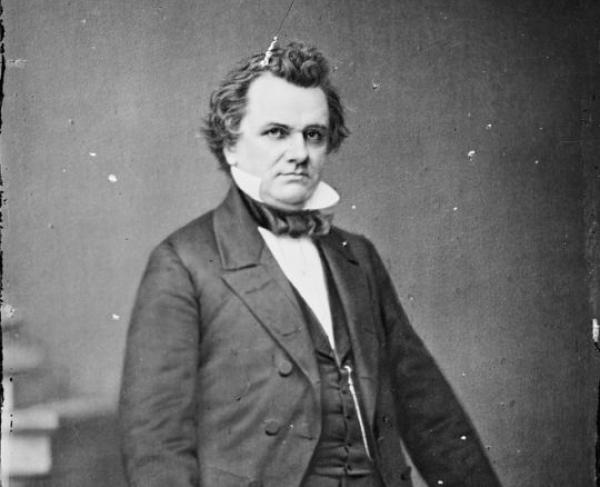

If Conservative Republicans put he Union over Emancipation, then Radicals put Liberty over Union. For them, the Union was a means to an end: The United States were meant to be the harbinger of liberty, not the protector of slavery. At times, this had resulted, weirdly enough, in pro-secession rhetoric, and some radicals had even supported state nullification of pro-slavery Federal laws. For example, they repeated Sumner's sentiment that if the Union’s existence depended on the so reviled Fugitive Slave Act, then it “should not exist”, and published articles claiming that Northern secession would create a stronger and more prosperous country, free from the Slave Power at last. However, now that war had come, Radicals took the mantle of fierce Unionism and Nationalism, insisting on granting broad powers to the Federal government. True to form, these Radicals wanted these powers to be used not to push forward any kind of Whiggish platform, but to enact emancipation. For example, one radical asserted that "We have entered upon a struggle which ought not to be allowed to end until the Slave Power is completely subjugated, and emancipation made certain."

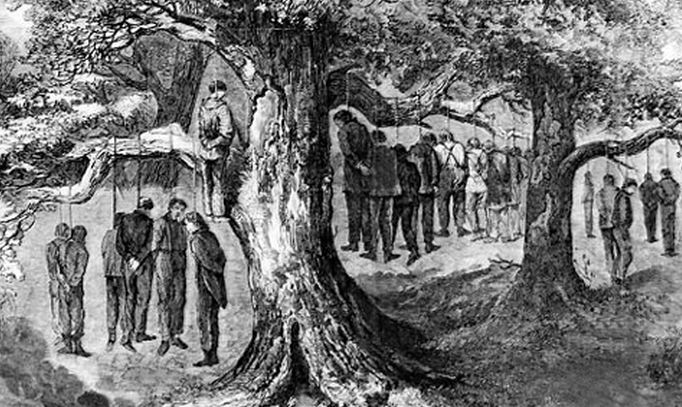

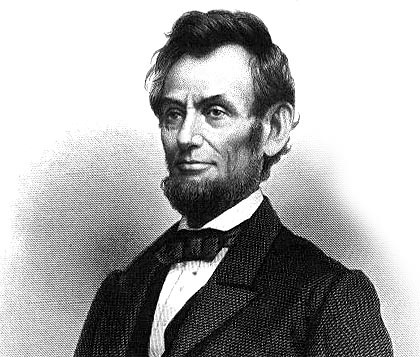

President Lincoln was, unfortunately for the radicals, a moderate who was unwilling to start a remorseless struggle. Thaddeus Stevens, the grim House radical who, per his own admission, was more progressive than his constituents, called for a radical war that would end not only the Slave Power but the South itself: "Free every slave—slay every traitor—burn every rebel mansion, if these things be necessary to preserve this temple of freedom." He concluded that the government should treat “this war as a radical revolution.”

But Lincoln wasn’t willing to go this far. Though Lincoln was criticized for his leniency towards the South during the war, before it some people thought he was too radical. His “House Divided” speech was similar to Seward’s “Irrepressible Conflict”, in that both advanced the idea that two different societies existed within the Union, and that one of them would eventually have to triumph and become the Union itself. Political observers often thought that Lincoln was closer to the radical wing that the conservative one, and event during the 1850’s and the war would indeed make the moderate faction he led come closer to the radicals. Conservatives like William T. Sherman distrusted him while radicals like Joshua R. Giddings supported him due to this perceived radicalism. A Chicago newspaper even when as far as saying that Lincoln was “intensely radical in fundamental principles.” It’s very telling that the Republican National Convention believed it necessary to pair him with the steady conservative John McLean.

The views of the Prairie Lawyer himself had started to change after his election to the Senate in 1854. He had run for Senate as a Whig, refusing to ally himself with the Republicans until 1856 – but in that year he quickly assumed a central position as a party leader, sparring with Douglas and ultimately allowing Frémont to carry the state. He often stressed that morality was at the center of the Party’s and his personal animosity towards slavery. And he had established close friendships with radicals like Owen Lovejoy (who was elected to the Senate in 1858 thanks to Lincoln) and the famous Frederick Douglass. In fact, Lincoln had invited Douglass to his debates with the Little Giant in 1858, and tried to invite him to his inauguration. Lovejoy and Douglass also convinced him to drop the idea of following emancipation with colonization. Lincoln had been a fervent supporter of the measure, but he turned against it following a reunion with many Black leaders who declared that the US was their home, and they wouldn’t leave it.

Likewise, he had started to talk of Black citizenship and the future of Black Americans after emancipation. If they were to stay within the United States, then an effort would have to be made to integrate them into American society. For the moment, he dodged the most explosive questions regarding social equality, but Lincoln had always insisted on legal equality. This was more than what most moderates were willing to go, for they often ignored these questions altogether. Lincoln, for his part, met them head on. Lincoln’s “radicalization” can also be seen in how he dealt with his cabinet. He appointed Seward, but was miffed by his attempts to take over and become the “premier”, and ignored his advice regarding his inaugural address, instead issuing his first and far more severe draft as part of his effort to not give an inch to the rebels. Likewise, he refused to appoint the very conservative Edward Bates, and only chose Montgomery Blair after he had come out as one of the strongest supporters of no compromise in the face of Southern coercion. All this points to growing Radical strength and waning Conservative influence.

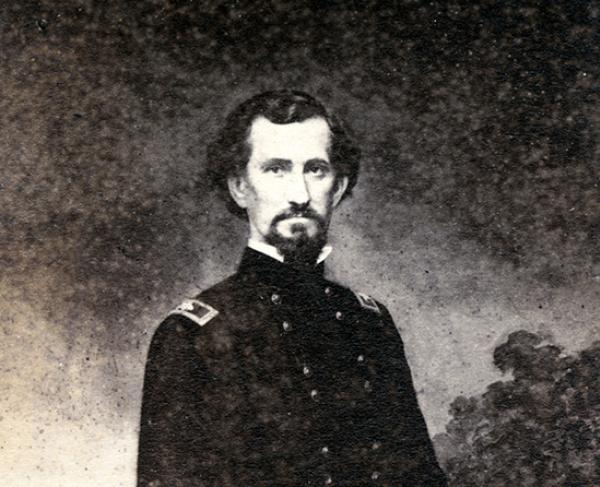

Owen Lovejoy became a fervent abolitionist after his brother Elijah was murdered for publishing an anti-slavery newspaper

But despite this, Lincoln wanted the war to be one for Union. Emancipation could come later, through constitutional means. Some people, including John Quincy Adams, insisted that as President Lincoln had the power to start emancipation in case of a civil conflict. But Lincoln didn’t want to do so, not yet at least. His careful strategy around the Border States required him to not use those war powers, whether they were Constitutional or not. But many events forced Lincoln to face the slavery question.

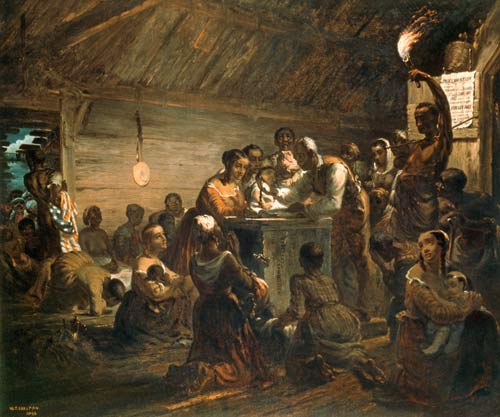

Maryland was the focal point of the controversy. Some slaves had already escaped to Federal forts in Florida, but they had been returned to their owners. For the moment, the administration intended to continue enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act, to assure the loyalty of the locals. A Unionist Maryland newspaper complained that Lincoln’s administration had returned more slaves than Buchanan had during his entire presidential term. Even if Lincoln had wanted to ignore the issue for the moment, the slavery question “was forced upon the administration by the negroes in the Maryland army camps.” Just as Orville Browning had predicted, “wherever our armies march into the Southern states, “the negroes will, of course, flock to our standards—They will rise in rebellion, and strike a blow for emancipation from servitude, and to avenge the wrongs of ages. This is inevitable.” Indeed, thousands of Maryland slaves escaped their plantation and sought refuge with the Army of the Susquehanna. Annapolis, under the command of Benjamin Butler, was a point of concentration, being close to the Chesapeake tobacco plantations.

Butler would become the unlikely hero of thousands of slaves, and perhaps millions more, when he first refused to return slaves by calling them “contrabands.” It happened this way: In July 15th, 1861, five fugitive slaves, who had been working building fortifications for the forces of Stonewall Jackson, escaped to Butler’s own defenses. Deciding that handing them back would augment the enemy’s strength, and that he himself needed more manpower, Butler put them to work. When a Confederate officer approached under flag of truce and asked for the slaves to be returned, Butler refused, saying that if Maryland was a foreign nation the Fugitive Slave Act didn’t apply. If the officer wanted his slaves, he would have to swear loyalty to the United States, something he refused. Butler justified his actions by calling the slaves “contraband of war”, a term used in international law but only for war-making goods seized from the enemy. The reasoning was that slaves would be used to make armaments, grow food-crops or build fortification, so taking them in and making them support the Union’s war-effort rather than the Confederate one was the rational choice.

The term “contraband” quickly spread as a way to refer to the fugitive slaves. The administration could not remain silent for long – it was clear that some kind of policy regarding the contrabands would be needed. Butler himself wrote to Lincoln, asking whether he could continue to receive fugitive slaves due to humanitarian or political reasons. “Of the humanitarian aspect I have no doubt. Of the political one, I have no right to judge,” the general wrote. Lincoln jokingly called the contraband policy “Butler’s Fugitive Slave Law”, but he realized that making emancipation a war goal would shake Kentucky’s and Missouri’s Unionist governments. Consequently, he refrained from settling upon a broad policy, instead merely “approving” Butler’s policy. Lincoln also made no reference to Butler taking in Black women, children and elders, despite the fact that the doctrine of them being war-resources was weaker there. For the time being, the administration intended to bypass the slavery question and allow each commander to decide what to do. But like the editors of the Harper’s Ferry commented, “The disposition of runaway slaves cannot be left to individual military commanders—the government must adopt a uniform policy.”

Orville Browning

Congress as a body complicated matters, since the lawmakers, many of whom thought themselves superior to Lincoln, aspired to take command of the war. Lincoln would later become convinced that as President he had the sole authority to deal with the slavery question, especially if emancipation was to be conducted under the contraband policy. This didn’t stop Congress, of course. The most dogged lawmakers were the Radicals, many of whom insisted that the Southern rebels had forfeited their constitutional rights – a position that directly contradicted Lincoln’s assertion that this was a rebellion of individuals and that the states themselves still remained in the Union, their rights intact. Though Lincoln wished to maintain a close and working relationship with Congress and put Party unity above factional disputes, the Radicals were committed to abolition above anything. Many times they had threatened to bolt the Party should it become too conservative. And the war had only stiffened their decision.

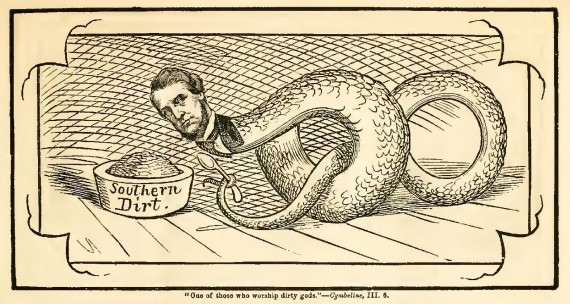

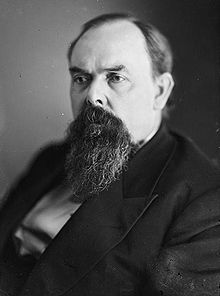

The clearest mark of this was the Radical crusade against the Johnson Resolutions. Presented by Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, the only Senator from a Slave State who had remained loyal to the Union, the resolution explicitly stated that the war was not for liberty, just for Union, declaring that the government would have no intention "of overthrowing or interfering with the rights or established institutions of [the seceded] States" but only "to defend and maintain the supremacy of the Constitution and to preserve the Union with all the dignity, equality, and rights of the several States unimpaired.” Radicals opposed the resolutions. Charles Sumner, for example, said that the Slavocracy had not respected the rights of Kansas, forcing slavery upon her. If the government could use its powers to uphold slavery, it naturally could also use them “in the noble fight against the corrupting harlot.” At the end, moderate and conservative Republicans were able to overcome the opposition of their radical colleagues, but only barely.

Owen Lovejoy gave Lincoln another headache when he introduced a resolution in the Senate in the wake of the contraband controversy. The resolution stated that it was “no part of the duty of the soldiers of the United States to capture and return fugitive slaves” and calling for repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act. It was expected to pass in the Senate, where Republican strength was the greatest. Thanks to the resignation or expulsion of most Southern Senators, only 4 Democrats remained – Johnson, the 2 Maryland Senators and 1 Kentucky Senator. One Senator from California, and the Senators of Missouri and Kansas would soon be expulsed, while the National Union only had two Senators. Republicans had a 33 to 11 majority (soon to become 36 to 8). The Resolution quickly passed, but it found greater trouble in the House where the National Union and Border State congressmen could put up stiffer resistance. However, Republicans still had an overwhelming majority of 134 of 181 House seats.

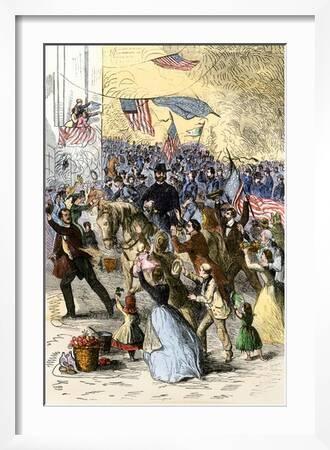

The resolution passed, in part thanks to the morale boost of the victory at Baltimore. Fortunately for Lincoln, Polk had already invaded Kentucky and turned most of the state towards fierce Unionism, while Lyon had stabilized the situation in Missouri. But it still constituted a direct contradiction of the Johnson Resolutions, and showed Republican dissatisfaction towards Lincoln’s contraband policy. It also showed that even if moderates were not willing to make emancipation a war goal, they were prepared to “let slavery perish” as another casualty of the war if necessary, as the otherwise moderate Senator Dixon said. More worryingly, Senator Garret of Kentucky said that despite being a “pro-slavery man” he was willing to give up slavery for the Union even if that meant that “another fibre of cotton should never grow in our country.”

Andrew Johnson

Decided to settle the contraband controversy and emboldened by success in Baltimore and at Congress, anti-slavery Republicans put a Confiscation act up for a vote in August, in the twilight days of the Congressional session. If confiscated property, including slaves, but only if they had even used to support the Confederate war effort. However, it was radical in one aspect – it proclaimed that slaves thus confiscated would be forever free. This was too much for moderates, who decided to instead leave the condition of the slaves ambiguous for the time being. The Harpers’ Weekly observed that the question of “the future relations of the government with slavery,” would be adjourned until December by “general consent.” But the Pathfinder of the West prevented Lincoln from settling aside the issue as well.

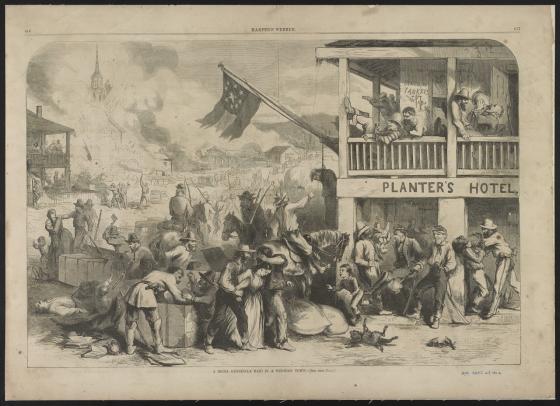

Frémont’s notable proclamation had declared all slaves free, which went much further than the Confiscation Act. Lincoln quickly revoked the edict, which proved controversial and even unpopular with most Republicans. "Permit me to say damn the border states. . . . A thousand Lincolns cannot stop the people from fighting slavery”, asserted a Connecticut Republican. Lincoln judged it necessary, however, for Frémont’s high-handed behavior had crippled the efforts of the Missouri Unionist government. John Howe even wrote to Postmaster Blair asking him to “save us, and remove Frémont.” Though Lincoln said that he wasn’t opposed in principle to emancipation or military measures to deal with the guerrillas, he definitely couldn’t support total military rule, writing to Browning that the government would cease to be one “of Constitution and laws” if “a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation?” Frémont could take in contrabands, but he was exceeding his functions by settling their future condition. Only Congress could do so by statute.

Lincoln asked Frémont to “modify” his proclamation. A more tactful general would have understood that Lincoln was trying to save him the embarrassment of having the order revoked directly, and would have acquiesced. But Frémont was anything but tactful or prudent. He arrogantly refused to modify the order, even sending his spirited wife Jessie Benton Frémont to speak with the President – an action that only offended Lincoln. Out of choices, Lincoln publicly ordered Frémont to revoke the order, and after his defeat by Sterling Pryce, Lincoln removed Frémont from command and appointed Lyon in his place instead.

But the political damage was done. Many letters reached Lincoln’s desk, all offering sharp criticism of his actions. “You can heardly imagine the thrill of pain that you have sent through many Christian hearts, by revoking that ritcheous proclamation of Gen. John C. Fremont. . . . The rebellion can never be put down till slavery is uprooted,” wrote a Michigander, while the blunt J. C. Woods limited himself to saying “either Fremonts proclamation or the South will win. Take your choice.” Ultimately, Lincoln’s preoccupation with Kentucky and Missouri made him stick to his course. Nonetheless, a rift was starting to grow between him and the radicals. Another point of contention soon arose, when Secretary of War Simon Cameron endorsed the enlistment of black soldiers.

Cameron’s position was endangered due to his incompetency and the corruption within his Department. Though a conservative, he sought to ally himself with the Radicals so as to protect himself. For that reason, his annual report included a suggestion that contrabands could be armed and serve as soldiers, a position that he knew would be incendiary. Many friends and colleagues advised him to not put that in the report – Blair even said that Cameron was running the “nigger hobby” for political gain. Yet at the end he did publish it, even sending some copies to newspapers before sending one to the President. He used the allegory Edwin M. Stanton had given him: that the government had the right to use seized slaves as soldiers as much as it had the right to use seized gunpowder. Whether Stanton endorsed the proposal because he genuinely believed in abolition (a plausible explanation, taking into account his friendship with radicals like Chase or Sumner) or because he hoped to be chosen after Cameron was fired, it’s not known yet. But if his objective was the latter, he succeeded.

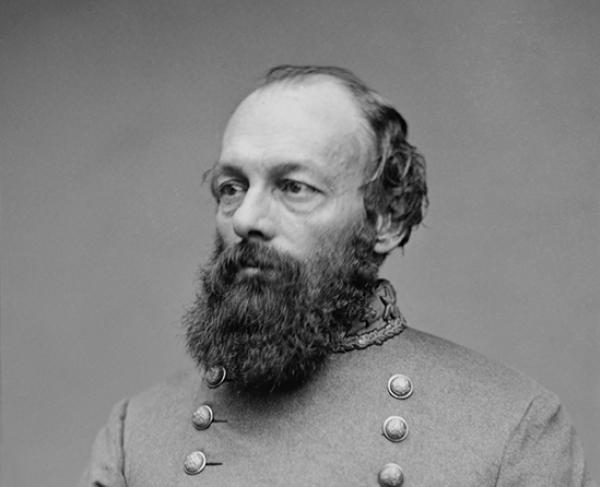

Edwin M. Stanton

An outraged Lincoln quickly ordered the suggestion deleted, exclaiming that “Gen. Cameron must take no such responsibility. That is a question which belongs exclusively to me!” Unhappily for the commander in chief, the debate had entered the public stage. “Let the sword make a nation of four millions of black men free, and then give them a sword of their own, so that their liberty will be protected”, said an abolition, while Frederick Douglass argued that “One black regiment alone would be, in such a war, the full equal of two white ones. The very fact of color in this case would be more terrible than powder and balls.” The astounding events that took place in Baltimore gave more fire to the debate, because Black civilians had formed militias and helped the Federals in taking the city. “Without the manly and brave sacrifice of the Baltimore negroes,” the Hoosier radical George Julian said, “the port city would have never been taken by our arms.” A Vermont radical also made the point that “the Baltimore negro population suffered terribly and fought bravely for the liberty of the city, and yet the administration refuses to give them the tools to continue that fight. A greater insult has never been dealt before.”

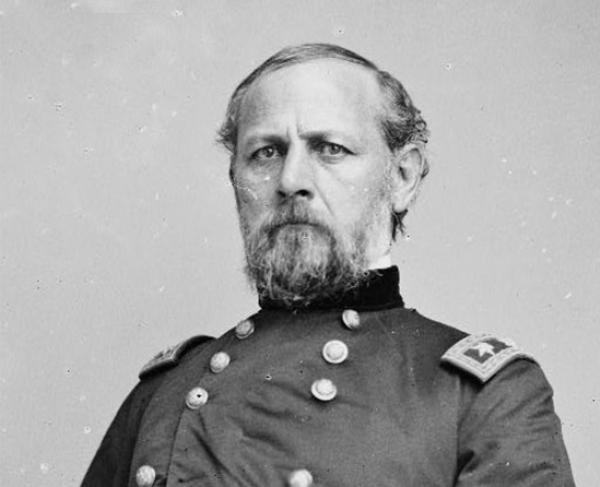

Another complication was Kansas. The Lecompton government had been driven off, and the triumphal Topeka Legislature quickly proclaimed its constitution, one which declared that slavery could not exist in Kansas. Yet, slavery did exist in Kansas as a matter of fact, for the years under the control of Lecompton had seen many slaveholders move into eastern Kansas, which had similar soil and climate to the slaveholding center of the Missouri river basin. Yet the continuing conflict and greater support by Republican lawmaker and New Englander immigration societies meant that the number of slaves remained low – only 10,000, a mere 6-7% of the 170,000 persons in Kansas, half the Missourian ratio. Those slaves now had to be liberated. As a legislator said, “the loathsome institution existed in this land as a contravention of the natural law – something that now must be corrected.” For that reason, the Topeka Legislature asked General David Hunter to carry out military emancipation of all slaves in the territory.

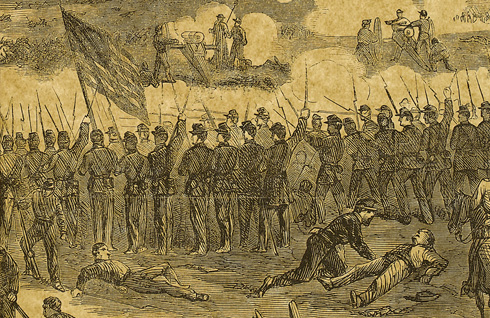

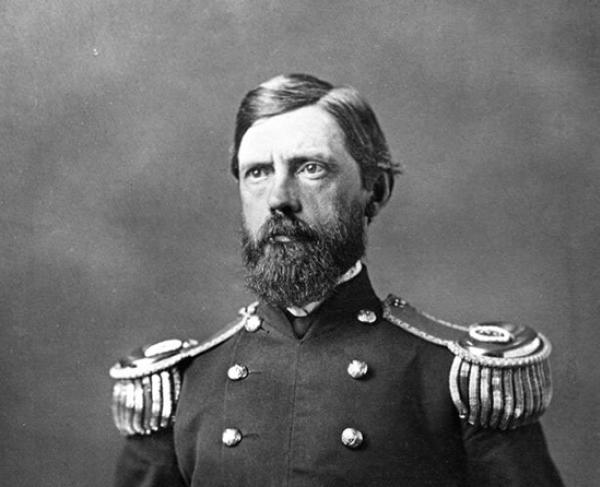

Hunter, the defiant abolitionist from Illinois who rose to prominence thanks to political connections and an admirable service at Baltimore, was a proponent of both abolition and black military service, and he found ready allies in Topeka. He quickly used the army to liberate slaves, and organize them into the First Kansas Colored Infantry. The Black soldiers pursued the rebels that remained in Kansas, and it was with their help that Hunter managed to drove them off the state and into the Indian Territory, whose tribes had aligned themselves with the Confederates. The success was applauded by the anti-slavery press, and even moderate Republicans had to recognize the admirable performance of the men, but the administration for the moment refused to recognize the existence of these regiments. Lincoln was dismayed when he heard that Congress planned to address the slavery question, including black service, in the next session in December.

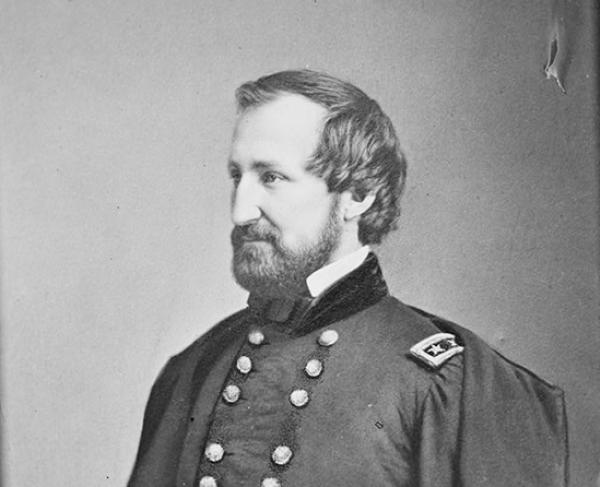

David Hunter

For the moment, the Lincoln administration wanted to ignore the wider questions regarding slavery, for the President did not feel ready to start a war with the expressed objective of achieving emancipation. Lincoln wanted to uphold the constitution as he saw it, and achieve the ultimately extinction of the monstrous injustice through legal means, but as the war took a more radical turn and events started to push in a different direction, Lincoln realized that the war was linked with slavery. As the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child said, “we are drifting somewhere… Where we are drifting, I cannot see, but we are drifting somewhere; and our fate, whatever it may be, is bound up with slavery.”

The most poignant expression of the fact that Lincoln couldn’t ignore slavery was given by John L. Scripps, his campaign biographer. “To you sir has been accorded a higher privilege than was ever before vouchsafed to man. The success of free institutions rests with you. The destiny not alone of four millions of enslaved men and women, but of the great American people…is committed to your keeping. You must either make yourself the great central figure of our American history for all time to come, or your name will go down to posterity as one who…proved himself unequal to the grand trust.”

Last edited:

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/capture-of-new-orleans-large-56a61c2f5f9b58b7d0dff6bf.jpg)