I don't think Sherman would sport an attitude like this in either OTL or this timeline, because even after all the divergences and experiences, Sherman still held sympathy for the southern states. While opposed to secession, historically he maintained friendships with at least one Confederate general post war (Joe Johnston). While Sherman could be callus at times, I feel like at times the site has people imagine Sherman a bit too gun-ho for Southern destruction than he actually was.Why can i see Sherman saying something on toombs similar to stalin when he heard hitler committed suicide.

”Now he's had it. Pity we couldn't take him alive.”

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"Well, be assured all of them will be explored in detail.A few things I would like to see in the post-war story:

- How the world is impacted by a different civil war and Reconstruction, as well as the US's better attitudes and treatment towards Black people

- How the labor/socialist/anti-capitalist/anti-authoritarian movements will be impacted ideologically and also in their struggles

- How Reconstruction will go, and how any attempts to roll back attempts to help Black people will be fought (*cough* KKK *cough*)

Oh, I see! Great movie!It's a reference to Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

I think investigations into "war madness" may at least provide some info that later people will look back on when the foundations of psychology are laid. And, yes, I could see a romanticization of Breckinridge as the leader of an "honorable" fight, saying all atrocities and problems were the fault of the Junta and their successors. Again, a "Clean Confederate" myth - yes, the war was over slavery but because those evil slaveholders used the common people for their evil ends!Psychology is another topic that might be worth discussing in Reconstruction. While I doubt we'll see major headways into PTSD research and post-wartime treatment, the gruesome aftermath of the ACW is bound to leave a large number of veterans deeply unwell (especially among the Confederate side), enough for doctors to notice even with limited means to document or treat them.

It's certainly possible. There are so many people from the poor or middle class who suffered so much that someone will grow up to write about their experiences in a novel. I'd imagine a book like that would look back and romanticize the Old South (and even the Confederacy under Breckinridge) only for the Civil War to rip that apart and leave them starving and broken thanks to the Slavocracy, with the end being incredibly bittersweet as they can never claim their old peaceful livelihoods back.

A movie about John Brown on the scale of Birth of a Nation sounds epic. Far more worthy of being shown in the White House than that piece of racist garbage.

Thank you! And yes, as I said I think it perfectly captures the themes I was going for. Especially, even if accidental, the end of a planter family is also symbolical of how they ended up destroying themselves through their actions. And I can totally see those opinions regarding John Brown - often in historiography it feels the tendency is for correction to be followed by overcorrection and then revisionism.I'm glad you liked it and honestly I'm over the moon about it being made canon. The Jacquerie is such a solid idea for this TL and does much to solidify the themes you've been playing with this whole time, really solidifying the ACW as a second American revolution and showing how the old southern way of life, that of the master and the slave is truly being shattered.

I'll also note that I didn't realize until just now that I accidentally wiped out an entire family line with this story. So make of that what you will. If you want to get metaphorical, you could argue that each character represents a different class in the old south and after that, the story takes its course.

I really like this idea, honestly, a movie about John Brown would make for an excellent action film so it feels fitting to give him and his story the honor of being the "first" action movie.

John Brown in general is going to cast a long long shadow over the American psyche with him becoming a proper folk hero far sooner and far more firmly in this world. Interestingly, it could be a reversal of what happened in our world. In OTL, he's getting a bit of a renaissance now as an American hero, but ITTL, he might see a bit of a reassessment as people confront that he was, for all intents and purposes, a terrorist. One on the side of angels, but a terrorist all the same.

I fully believe it's important for both parties to have Black blocs, because otherwise it becomes too easy to trace a "White line" and appeal to racism as a way to win elections. So we'll definitely see a split between prosperous Black people more aligned to the cities and conservative ideas, and the rural folk who'll be attracted to a Farmer-Labor Party.I've been thinking about the post-war settlement, and there's two things I'd like to note:

The first is regarding the composition of the eventual labor Republicans. If, as has been suggested, they end up absorbing the Populists, which is very likely - despite their extremely agrarian tendencies they, from the earliest proto-Populist movements in the 1870's (the Greenback Party, for example, merged with the Labor Reform Party to form the Greenback Labor Party) had always sought to attract labor to their cause. Absorbing the extremely agrarian Greenbacks/Populists could easily lead to a strong Farmer-Labor leaning for the eventual labor party, which could lead to a lot of interesting results (in particular, for something absent IOTL, you could see division between African-American farmers and more mercantile/machine oriented or conservative African-Americans like Booker T. Washington - depending on if Black settlement in the prairies is much higher than OTL, you could use it to give both parties substantial Black blocs that keep both of them interested in protecting Black rights).

Another thing is regarding civil service reform, which did not cut cleanly across economic or social lines but during the 1870's was the biggest political issue and a key divider inside of both the OTL Democrats and Republicans. I actually think the post-war GOP might have three factions post-war: in addition to the Labor Republicans and the Business Republicans, you could also see Civil Service Reform Republicans, with the three factions variably cooperating with each other, as I just don't see how fellow economic conservatives like Roscoe Conkling and Rutherford Hayes end up in the same faction given how much they hated each other on the civil service reform question that, IMO, is going to be an unavoidable part of the post-war question. A very interesting thing to explore here is how you thread the needle of how often civil service reform was use to screw Black people IOTL versus the fact that corruption is going to need to be dealt with - figuring out how to separate the reformism from its often racist elements (which is why early Black Republicans were so conservative early on) could be an integral part of the Republican Party's journey, and also possibly enables the laborites, who I suspect would be dismissed as dangerous radicals in their early years, to eventually become a major party - if the reformists/liberal Republicans decide to split from the party on the same cycle as a really bad economic recession, this split in the vote and good messaging from the laborites could be what enables them to actually win, before they eventually reunite in order to defeat the laborites.

Civil Service reform is going to be messy. It's especially difficult because, as you note, often the strongest advocates of Black rights were some of the most corrupt Party bosses, while some of the Reformers were also racists that believed any Black participation in government was inherently corrupt because Black people would, according to them, always vote for demagogues who abetted their lazyness. I wish to separate the issue of reform and Reconstruction as much as possible, but given the classism of the Liberal ideology, which is bound to look down on Black workers, it's a tall task indeed.

Btw I forgot to mention it, but I also threadmarked a vignette you wrote earlier. I really appreciate your contributions, thank you.Indeed, that's the whole idea behind doctor Dacosta in the pieces I've written. The fact that he is in Philadelphia and will have the ear of some leaders, especially now that the war ending makes them relatively less busy helps. In our timeline in the 1860s, you could see research being done in Philadelphia. And it wouldn't catch the eye of anyone in Washington unless it was really big news. Being in the same city has a major effect.

So, it won't be PTSD being understood clearly, as much as the field of psychology will very likely develop from this greater trauma and the idea of a peace and trauma spectrum might be the original basis versus what Froid developed.

Yeah it's insane that this is basically the prologue lol. But, thank you! I appreciate your words.Now the that prologue is over let this epic begin.

Edit: also congratulations @Red_Galiray on finishing this first part of the TL it has been a hell of a ride.

The rural people will be the key to Republican success. It's key for the Republicans to show that them being in power means land, food, opportunities, protection from debt seizures, and security to the rural folk. If they can't make them loyal and accepting of Black people and the new order at the point of a bayonet, at least they ought to prevent terrorist activity by making just living at peace at home a better option.It does also make for a split in party loyalties down South later on. Of course, the economic interests between agriculture and industry have usually clashed over taxation and tariffs, but the rural South could be fertile grown for a biracial political coalition for more pro-labour/populist policies. I also wonder how rural and urban Southerners would view the collapse of the Confederacy differently, especially since the rural South got the worst of it.

Yeah, Beauregard largely seemed to have swallowed the defeat of the South relatively well compared to Jubal Early. I doubt that he'll dare to come home if the trials do see generals hung for treason. As for where he could go, there's always Mexico or Egypt (Confederate general W.W. Loring did so). Now, what might the U.S. think? Well, it might not amount to much at first, especially if he's at far away Egypt. But then I thought about the idea of Lincoln visiting Jerusalem and *gasp* look Beauregard's right there with his mercenary army! He's up to no good! Even more so if a few hundred Southerners chose to follow him - clearly a bodyguard for his return to the South!

He was a cavalry division commander, and participated in several major battles. I could imagine him puffing up his credentials by claiming he led the cavalry charge at Sayler's Creek, ignoring his superior's and colleague's contributions to the fight. I remember there was a time when Custer was propped up for leading the "charge that saved the United States" at Gettysburg - for leading his brigade in action, ignoring the fact that Stuart was just there to draw some attention, and that his division commander was running the whole battle.

Oh, there will be hung generals. I don't think he could ever be seen as an active threat, but it would be certainly uncomfortable for the US to have him running around... especially if he goes somewhere like Brazil, where Beauregard did pursue a position he ultimately declined due to Johnson's policies. Another slaveholding country, a monarchy at that, with a big population of Confederate exiles, hosting a leader of the Junta as a military commander? May make more than a few Americans anxious.

Looking up my sources for mentions of Custer, it's likely that he was indeed present at Sayler's Creek ITTL.

Eh, Sherman, I've tried to emphasize, was never really for post-war punishment. He was implacable during the war, true, but he never wanted any punishment or social revolution after it ended. His OTL terms of peace to Johnston were ludicrously lenient: he offered to let all Confederate governments in power and allow them to make laws, for Southern soldiers to retain their arms and become a force to "maintain order" in the South, and made no mention whatsoever of slavery. He even assured Zebulon Vance that he'd retain his office!Why can i see Sherman saying something on toombs similar to stalin when he heard hitler committed suicide.

”Now he's had it. Pity we couldn't take him alive.”

I frankly didn't reply because I don't know much about the Mormons. My first instinct, I'll be frank, is to dislike them. I am really against any kind of religious fundamentalism and especially can't tolerate a group that claimed Black people bore the curse of Ham, and which oftentimes has been accused of abuse towards its members and especially Queer people. There are interesting possibilities, but I don't really have the inclination to delve deeply into how the Mormons would fare in TL since I want to keep the focus on Southern Reconstruction. I can, however, say that this US government is very unlikely to be friendly to Young.This kind of got lost in the shuffle of the last post, but I am still curious of your thoughts on Utah and the Mormons in this TL @Red_Galiray

Hello,

Wasn't there another person of note who needs to be accounted for, he did help the junta set up. I forget his last name, but he was called Rhett.

Yes, Rhett was one of the most prominent Fire Eaters and also helped set up the Junta. He was never a member himself, but did wield some power. He, as well as most Fire Eaters, won't fare well, I can say.Surprise, you did remember his last name!https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Barnwell_Rhett I remembered it was his last name when you typed that but couldn't remember anything else so I just Googled and Fire eater.

He may very well be someone we see in the next thread.

Precisely. Sherman, in fact, was at heart more sympathetic to the Southern elite than the freed slaves. For example, IOTL when he destroyed Atlanta he gave boxcars to the wealthy so they could get their stuff out safely, then during the march he gave no help whatsoever to the freedmen. If he could, I fully believe Sherman would have simply restored a Union with slavery, with the Southern elite untouched, and with White supremacy firmly in place. His only issue was disloyalty and secession. Hell, during the initial negotiations with Johnston he actually took Breckinridge aside and told him to flee the country. I'm sure Sherman ITTL would also prefer to see Toombs successfully fleeing the country, and would be willing to make a surrender cartel with wide concessions if he captured him alive.I don't think Sherman would sport an attitude like this in either OTL or this timeline, because even after all the divergences and experiences, Sherman still held sympathy for the southern states. While opposed to secession, historically he maintained friendships with at least one Confederate general post war (Joe Johnston). While Sherman could be callus at times, I feel like at times the site has people imagine Sherman a bit too gun-ho for Southern destruction than he actually was.

Would that mean then that instead of Scarlett's family being different from the plantation owners IOTL and her family instead being the "Common peopl?" If so then how would that change Scarletts characterization so you think? Along with Rhett's and well everybody?I think investigations into "war madness" may at least provide some info that later people will look back on when the foundations of psychology are laid. And, yes, I could see a romanticization of Breckinridge as the leader of an "honorable" fight, saying all atrocities and problems were the fault of the Junta and their successors. Again, a "Clean Confederate" myth - yes, the war was over slavery but because those evil slaveholders used the common people for their evil ends!

I mean, there wouldn't be a Scarlett and a Rhett as we know them. This would be an entirely different work, with entirely different characters. We may see some parallels, but it wouldn't be just a fanfic version of Gone With the Wind under different circumstances. But, if it were up to me (and I guess it is?) I would lean into it starting pretty much like the OTL version, with a Southern belle and a man skeptic of the South being followed as the South crumbles around them. But "Scarlett" and "Rhett" would probably then either become Scalawags supporting Reconstruction because they benefit from it, or just be unreconstructed villains. I would also like to see it following a family of actual common people and an enslaved family, as they also experience the war and Reconstruction. Basically an epic looking at three families of the three "main" Southern groups: the elite that fails into ruin, the poor people who bear the brunt, and the Black slaves who receive their freedom. Much darker than the romantic GWTW of OTL.Would that mean then that instead of Scarlett's family being different from the plantation owners IOTL and her family instead being the "Common peopl?" If so then how would that change Scarletts characterization so you think? Along with Rhett's and well everybody?

Then maybe it could be like this "Scarlett" and her family could be the elite, "Rhett" and his family could be the poor people and the man Scarlett falls in love with and causes her to see the South for what it is and cause s her to become a as you say it "Scalawag" Who favors reconstruction and "mammy" and her family could be the black save s who receive their freedom. Just an idea.I mean, there wouldn't be a Scarlett and a Rhett as we know them. This would be an entirely different work, with entirely different characters. We may see some parallels, but it wouldn't be just a fanfic version of Gone With the Wind under different circumstances. But, if it were up to me (and I guess it is?) I would lean into it starting pretty much like the OTL version, with a Southern belle and a man skeptic of the South being followed as the South crumbles around them. But "Scarlett" and "Rhett" would probably then either become Scalawags supporting Reconstruction because they benefit from it, or just be unreconstructed villains. I would also like to see it following a family of actual common people and an enslaved family, as they also experience the war and Reconstruction. Basically an epic looking at three families of the three "main" Southern groups: the elite that fails into ruin, the poor people who bear the brunt, and the Black slaves who receive their freedom. Much darker than the romantic GWTW of OTL.

Not sure if you wanted to take it this way, but tying this in with the earlier idea of a Confederado uprising in Brazil (and giving Isabel a chance to distinguish herself.) It could be interesting for the Confederados to convince themselves that part of the reason they need to filibuster Brazil is that they at one point had some (loose) hold in the Brazilian government. It was likely never that large and faded naturally/at US objection, but it was enough for them to convince themselves they were being pushed aside again, a feeling confirmed when abolition finally comes to Brazil. All this for a final very stupid uprising that devolves into guys in rotting gray uniforms hiding out in the Amazon trying to avoid Brazilian Army patrols.Oh, there will be hung generals. I don't think he could ever be seen as an active threat, but it would be certainly uncomfortable for the US to have him running around... especially if he goes somewhere like Brazil, where Beauregard did pursue a position he ultimately declined due to Johnson's policies. Another slaveholding country, a monarchy at that, with a big population of Confederate exiles, hosting a leader of the Junta as a military commander? May make more than a few Americans anxious.

Even if the answer for why Brazil recruits him ITTL would be more prosaic that the rumors and whispers that would abound of him being somehow the leader of a Confederate army-in-exile with the Paraguayan War and Brazil thinking that any competent officer is welcome aboard.Oh, there will be hung generals. I don't think he could ever be seen as an active threat, but it would be certainly uncomfortable for the US to have him running around... especially if he goes somewhere like Brazil, where Beauregard did pursue a position he ultimately declined due to Johnson's policies. Another slaveholding country, a monarchy at that, with a big population of Confederate exiles, hosting a leader of the Junta as a military commander? May make more than a few Americans anxious.

This alone virtually guarantees a vastly more powerful and developed central state compared to OTL late 19th century equivalents even before the full consequences of Reconstruction have played out. The amount of bureaucratic and institutional capacity that has to be developed for this alone is massive.The initial relief efforts will be one of the hardest tasks faced by an 18th century government, with the South starved and submerged in anarchy.

It was so, SO satisfying seeing the remnants of the Slaver's Rebellion finally come apart and slowly dissolve under the Union onslaught, after this 5 year wild ride! Now time for an even wilder ride as Lincoln tries to win the peace ^_^

Bit anticlimactic with Kirby Smith, it sounds like aside from the final mutiny that part of the CSA did not see major unrest. Texas could be the first 'flashpoint' of Reconstruction, as its blacks were still in chains at the end of the war instead of their freedom being in large parts fait accompli in the east by the time the local Confederate forces surrendered.

Bit anticlimactic with Kirby Smith, it sounds like aside from the final mutiny that part of the CSA did not see major unrest. Texas could be the first 'flashpoint' of Reconstruction, as its blacks were still in chains at the end of the war instead of their freedom being in large parts fait accompli in the east by the time the local Confederate forces surrendered.

That could be it.Then maybe it could be like this "Scarlett" and her family could be the elite, "Rhett" and his family could be the poor people and the man Scarlett falls in love with and causes her to see the South for what it is and cause s her to become a as you say it "Scalawag" Who favors reconstruction and "mammy" and her family could be the black save s who receive their freedom. Just an idea.

Not sure if you wanted to take it this way, but tying this in with the earlier idea of a Confederado uprising in Brazil (and giving Isabel a chance to distinguish herself.) It could be interesting for the Confederados to convince themselves that part of the reason they need to filibuster Brazil is that they at one point had some (loose) hold in the Brazilian government. It was likely never that large and faded naturally/at US objection, but it was enough for them to convince themselves they were being pushed aside again, a feeling confirmed when abolition finally comes to Brazil. All this for a final very stupid uprising that devolves into guys in rotting gray uniforms hiding out in the Amazon trying to avoid Brazilian Army patrols.

Indeed, I'm really attracted to the idea of a Confederado uprising scaring Republicans who would see it as a new wave of filibustering.Even if the answer for why Brazil recruits him ITTL would be more prosaic that the rumors and whispers that would abound of him being somehow the leader of a Confederate army-in-exile with the Paraguayan War and Brazil thinking that any competent officer is welcome aboard.

Precisely. The change is enormous, and will have great consequences.This alone virtually guarantees a vastly more powerful and developed central state compared to OTL late 19th century equivalents even before the full consequences of Reconstruction have played out. The amount of bureaucratic and institutional capacity that has to be developed for this alone is massive.

Thank you! I'm glad you enjoyed the chapter.It was so, SO satisfying seeing the remnants of the Slaver's Rebellion finally come apart and slowly dissolve under the Union onslaught, after this 5 year wild ride! Now time for an even wilder ride as Lincoln tries to win the peace ^_^

Bit anticlimactic with Kirby Smith, it sounds like aside from the final mutiny that part of the CSA did not see major unrest. Texas could be the first 'flashpoint' of Reconstruction, as its blacks were still in chains at the end of the war instead of their freedom being in large parts fait accompli in the east by the time the local Confederate forces surrendered.

Originally there was more about Smith, but I cut it due to lack of space. Instead I think I'll publish a series of mini-updates to tie up some loose ends, and one of them would be a look at the Kirby Smithdoom while all this was going on.

On that note, considering Beauregard was “Reconstructed” to some degree IOTL, maybe he could be notable for “going native” and settling down in wherever he flees into exile out of acceptance of both the reality the war is lost and the United States would hang him if he ever tries to return?Indeed, I'm really attracted to the idea of a Confederado uprising scaring Republicans who would see it as a new wave of filibustering.

Firdaus_Rifa

Banned

Which one of the radicals that are Lincoln ally ? Is it Sumner? since I read both of them are quite friendly.

I think he'd feel completely homesick, and frankly planned to write him and most rebels as so.On that note, considering Beauregard was “Reconstructed” to some degree IOTL, maybe he could be notable for “going native” and settling down in wherever he flees into exile out of acceptance of both the reality the war is lost and the United States would hang him if he ever tries to return?

Owen Lovejoy was the most prominent Radical who was actually loyal to Lincoln, but he has passed away. Sumner can be quite friendly on a personal level but he's not afraid to oppose Lincoln if he believes Lincoln isn't acting right - he filibustered the Louisiana bill for example. Lincoln, however, likes Sumner and lavishes attention upon him to keep him friendly. Stevens is neutral, while Wade and Winter Davis are outright hostile. Overall, Radicals believe Lincoln still ought to be "educated" and remain far more preoccupied with pushing forward their revolutionary agenda than personal loyalty to Lincoln. As such, their status as Lincoln's allies is highly contingent on Lincoln being willing to make concessions.Which one of the radicals that are Lincoln ally ? Is it Sumner? since I read both of them are quite friendly.

just for chuckles , I hope Dan Sickles ends up embezzling the money he raised for his own statue like he did IRL

I don't think Sickles was ever featured prominently here, which is a shame since he was an amusing character.just for chuckles , I hope Dan Sickles ends up embezzling the money he raised for his own statue like he did IRL

Btw, see what I learned today. One of Breckinridge’s descendants, his great-grandchild, was a drag queen known as Bunny Breckinridge who appeared in Planet 9 from Outer Space, the infamously so bad it's good movie of Ed Woods.

Now that's phenomenal!Btw, see what I learned today. One of Breckinridge’s descendants, his great-grandchild, was a drag queen known as Bunny Breckinridge who appeared in Planet 9 from Outer Space, the infamously so bad it's good movie of Ed Woods.

When awful film becomes Oscar worthyI don't think Sickles was ever featured prominently here, which is a shame since he was an amusing character.

Btw, see what I learned today. One of Breckinridge’s descendants, his great-grandchild, was a drag queen known as Bunny Breckinridge who appeared in Planet 9 from Outer Space, the infamously so bad it's good movie of Ed Woods.

Just don't bring up Karloff when you're next to Bela Lugosi.When awful film becomes Oscar worthy

I’m so curious as to what will become of Albert Sydney Johnston. He’s been spared the gallows but he doesn’t strike me as the live a quiet life type.

Longstreet seems like a bitter memoir kinda guy

Longstreet seems like a bitter memoir kinda guy

Epilogue: The Union Forever

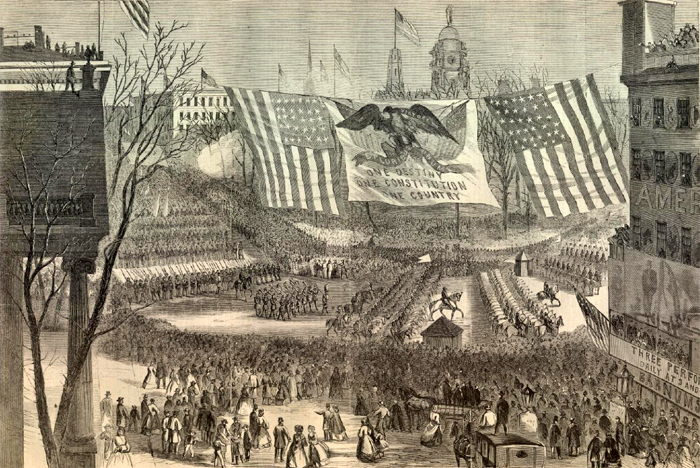

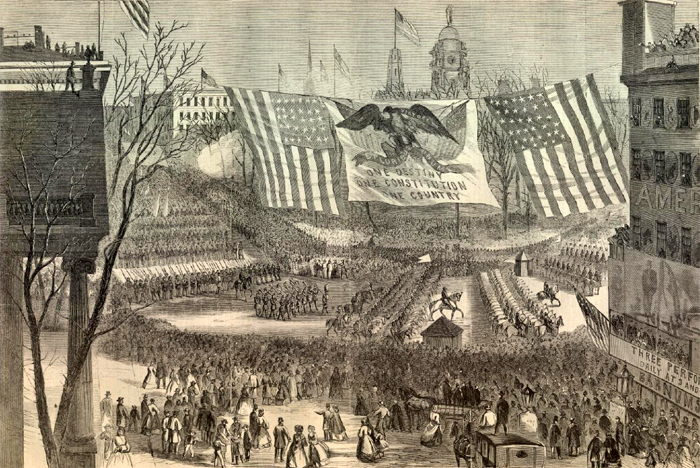

The American Civil War did not begin as a Revolution. While Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party promised in 1860 that their election would dislodge the Slave Power and place slavery on the path of ultimate extinction, they never advocated for revolutionary means to do so. Theirs was a gradual emancipation, one that would allow slavery to live for decades more, dying slowly but painlessly. This, the Slavocracy rejected. They wished for their peculiar institution to be perpetual, and to maintain their world, the one in which they lived as the unquestioned political, social, and economic leaders. Lincoln may not destroy slavery at once, but he dared to interfere with their prerogatives and speak of slavery as an evil that ought to be exterminated. Knowing that slavery would be for the first time on the defensive with the anti-slavery Republicans at the helm of the nation, Southerners tried to destroy that nation, unable to countenance even the slightest infringement on their power and honor.

The North accepted the war the South had started to maintain the integrity of the nation. For the Northern people, secession was chiefly a threat because a successful separation would eviscerate the unity and stability of the United States. What they believed to be the best government on earth, the source and guardian of their happiness and prosperity, would then collapse into several petty republics, and the American experiment would end. It was to prevent this that the soldiers of the Union Army fought. But everyone recognized the centrality of slavery to the conflict – both Union and Confederate soldiers knew that the South fought for slavery, and that the “way of life” Southerners claimed to defend would be one anchored in slavery and White supremacy. The average Northern soldier was not greatly concerned at first with overthrowing either, but they and their leaders soon realized that the Rebellion drew strength from the millions of people they forced to work for them. They, likewise, realized that the enslaved could be counted on as allies for the Union cause.

Yet, at this early stage, Northerners hesitated to turn the Civil War into a Revolution. Conservative men, opposed to secession but supporters of White supremacy, all dreamed of restoring the “Union as it was,” and insisting on prosecuting a war that disrupted slavery as little as possible. Lincoln was not one of these men. He and the Republican Party, from the first moment, predicted that Union victory meant the doom of slavery, for the Slave Power that had artificially protected it and guarded it from the natural march of progress, had been overthrown. As soon as the Southern States returned, the Republican policies of “Freedom National” would be implemented, and slavery put on the path of ultimate extinction. Free soil for the territories, abolition in the District of Columbia, the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, and Federal pressure on the Border States, all of these were adopted. But what would have been great anti-slavery achievements in the antebellum now proved insufficient, and the Union’s leaders had to recognize that the “inexorable logic of events” was now leading them towards Emancipation.

This momentous step couldn’t have been taken without the actions of the enslaved people themselves. Southern masters who had convinced themselves that the people whose liberty they robbed were happy and loyal, suffered a rude awakening as the war started. Far from what the enslavers had believed, Black people struggled mightily to obtain their freedom, offered their help to Federals that in many cases remained reluctant, and defied the power of the slaveholders. This did not, at first, happen through slave insurrection, for the enslaved recognized that the increasingly repressive Southern State had the necessary force to repress any violent uprising, making any such attempt nothing short of suicidal. Nonetheless, Black people opened a “second front” at the very heart of the Confederacy as they fled to the Union’s lines; offered their services as laborers, spies, and soldiers; and resisted the power of the slaveholders by refusing to work or demanding payment. As a State founded on slavery, the Confederacy had to resist this challenge, but it still sapped resources and manpower it could not afford.

The Victory of the Union

Thus, the Union accepted Emancipation chiefly as a military policy that would weaken the Confederacy while allowing it to gain greater strength by recruiting the formerly enslaved as allies in the struggle. But this should not be understood as merely a desperate policy Lincoln had no other option but to adopt. The administration had stricken back against slavery since the start, and at every crucible, at every choice between policies that weakened slavery and those that upheld it, Lincoln chose the option that furthered human freedom. Certainly, many Northern politicians and generals disagreed with the government’s interpretation of the war and believed that a conciliatory policy would be better. If it were up to men like Douglas and McClellan, the Union Army would have enforced the Fugitive Slave Act, would have never enlisted Black soldiers, would have never adopted the kind of policies that augured a Revolution in Southern life. Consequently, the gradual, painless, compensated emancipation all but the most Radical abolitionists had envisioned in 1860, had already given way to a complete, violent, and immediate destruction of slavery by military power in 1862.

The conservative dream of completely separating the war from slavery was over, and from then on, the United States Army fought not merely for Union, but also for Liberty. Again, this was not something incidental, for the war started a process of radicalization against slavery and then against White supremacy within the Northern people. Seeing the horrors of slavery up close, and identifying the Southern Slavocracy as the responsible for the conflict, Northerners started to feel a deeper moral revulsion against slavery than ever before. This wouldn’t have been possible without the efforts of Black people and their Radical allies, who continuously pushed forward for imbuing the war with a greater moral significance. These campaigns of anti-slavery slavery agitation, plus seeing the value of Black people and their commitment to the Union cause in such great events as the Battle of Union Mills, all helped to transform the nation’s conception of Black people. By the end of the war, Northerners had become fully convinced that the perpetuity of the Union, but also the aims of justice and the survival of the national ethos of Liberty, required the eternal overthrow of slavery and a true effort at Equality for all. The Civil War, then, had become the Second American Revolution.

This Revolution frightened Southerners. The Confederacy was a fundamentally counterrevolutionary effort, which sought to preserve the structure of antebellum Southern society, one dominated by the slaveholder elite, against the terrifying challenge Northern abolitionists presented. However, the South was not united in this effort. The question of the Confederacy’s legitimacy and its claim of democratic government is one that has been debated countless times. One must not forget that there were at least four million abolitionists that the Southern elite did not take into account when the secession movement started. Yet even beyond them, secession was not unanimously accepted by Southern Whites. Hundreds of thousands would resist the Confederacy, fighting in blue uniforms or as Unionist guerrillas, and defying the slaveholders’ pretensions to make them give up their properties and lives for a cause which seemed only to benefit the elite. Especially because that elite seemed unwilling to make the necessary sacrifices, resisting bitterly and shortsightedly every attempt to make them give up any of their “rights.” Deep cracks in Southern society were exposed and grew more pronounced as the war continued and the sacrifices asked of the poor increased.

The Southern masters responded to this challenge in the same way they responded to Black attempts to reclaim their freedom: with brutal repression. Throughout the war, the Confederacy and its Armed forces acted swiftly and ruthlessly against Unionists, persecuting, massacring, and attacking them. The sorry tales of repression in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina are examples. The Confederacy employed similar methods to stamp out defiance amongst the enslaved, who were used to being driven from their homes and murdered by White power structures. In this way, the continuous, aggressive State violence needed to maintain slavery and the power of the planter aristocracy was exerted, and the South answered to the North’s radicalization by radicalizing itself, taking increasingly appalling measures to maintain its power. And those great libertarians like Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens, who spoke so often and so bitterly against tyranny and for constitutional government, never challenged this repression. Because, to the leaders of the South, violence to enforce their “rights” was always good, whereas any challenge to their power, no matter where it came from, was completely unacceptable.

This meant that ultimately the government of John C. Breckinridge also became unacceptable to those who held power within the Confederacy. Committed to a successful prosecution of the war above all else, the Breckinridge regime employed all the methods thus described to enforce the power of the Confederate State, but also sought to lessen the burden upon the poor and push the wealthy to make the necessary sacrifices. The Administration thus faced planters that fought against impressment of goods and enslaved laborers, resisted his intromission in local government and obstructed the prosecution of the war, and above all believed that Breckinridge was not adequately protecting slavery. All because these measures attempted against the power they held to be sacred and untouchable. And thus, Breckinridge to them became the worst tyrant in history not because of what he did to Unionists or Black people, but because he dared to tell them what to do.

The Defeat of the Confederacy

This culminated in the so-called “Five Monstrous Decrees” and the attempt to recruit Black soldiers, both hard blows against slavery that nonetheless failed to save the Confederacy, which tottered in the brink of destruction after the Union victories in Atlanta and Mobile. Knowing that further resistance was hopeless, Breckinridge then tried to surrender, hoping that a negotiated peace may yet save White supremacy or even slavery. But even this the planter aristocracy could not countenance. Deciding that it was better to be utterly destroyed than to voluntarily give up their “rights,” they overthrew Breckinridge and then executed him, cleaving Southern society in two and alienating the poor Whites who had seen him as their protector. In this Southerners were merely repeating history, for it was this same pride and arrogance that had resulted in secession. And just like how secession had only brought about the very revolution they had wanted to avoid, more radical and immediate than it could have been otherwise, the coup against Breckinridge only assure that the war would go until it destroyed the Confederacy. The same suicidal instinct that had made them unable to accept Lincoln, made them reject Breckinridge, and thus assured their complete perdition.

The result was a bloody, horrifying fiasco, just as Breckinridge had predicted. The South’s collapse resulted in famine extending through the Southern countryside and a breakdown of order, leading to anarchic Jacqueries that claimed thousands of lives more. This assured that the Civil War would be the deadliest conflict in American history, and one of the bloodiest in the history of the world. Over 650,000 Union soldiers died in the struggle to maintain the nation, and a further 500,000 Confederate soldiers, most of disease. Famine, anarchy, and disease, extending beyond the end of the war, all claimed some 100,000 civilians in Union-areas, while over 500,000 thousand Confederate civilians died. The 1.8 million people that died in the war represented 5.8% of the US population, and, staggeringly, over 10% of the Confederate population and over 40% of its White males of military age. The war had further reduced the South to an “economic desert,” making the South go from 30% of the nation’s wealth to less than 10%. It also fundamentally changed the dynamics of power – never again would the South domineer over the Federal government as it once did, but instead the US entered a period of Northern, and more specifically Republican, dominance.

The most inescapable fact of Southern defeat was the destruction of slavery. Unlike what Northerners had believed, slavery proved to be a sturdy institution, requiring powerful military blows and a concerted effort until it was destroyed. The legal end of slavery throughout the nation did not come until June 1865, when the Reconstructed government of Mississippi ratified the 13th amendment, securing emancipation in the South and starting it in Kentucky and Delaware, both of whom clung to the institution. The actual end of slavery came on the ground, as Union soldiers started an occupation of the South and enforced emancipation at gunpoint. But the military and unconditional defeat of the Confederacy had already assured the outcome, granting their freedom to over four million of human beings and revolutionizing Southern life. “Society has been completely changed by the war,” observed a Louisiana planter. “The [French] revolution of '89 did not produce a greater change in the 'Ancien Régime' than this has in our social life.” And he was completely right – the American nation would never again be the same.

The “vaunted world of privilege and power” that the Southern elites had enjoyed and sought to protect now came crashing down around them as the victorious Union enforced emancipation, land redistribution, and justice against the leading rebels. “The props that held society up are broken,” said the daughter of a former planter, as she observed these changes. The once “rich, hospitable, powerful, are now poor, and like Samson of old shorn of their pride and strength,” grieved a Mississippian. Katherine Stone gasped in horror at the idea of “submission to the Union (how we hate the word!), confiscation, and Negro equality.” Sarah Morgan believed for her part that it would be best for Southerners to “leave our land and emigrate to any desert spot of the earth.” Some rebels followed her counsel and fled the country, never to return, the most prominent of them being General Beauregard. E. Kirby Smith and some of his lieutenants fled to Mexico; Judah P. Benjamin and others preferred Europe, while other communities tried to relocate to Brazil or Cuba. Some 50,000 rebels left the country, convinced by the fate of those who stayed that this was the right choice.

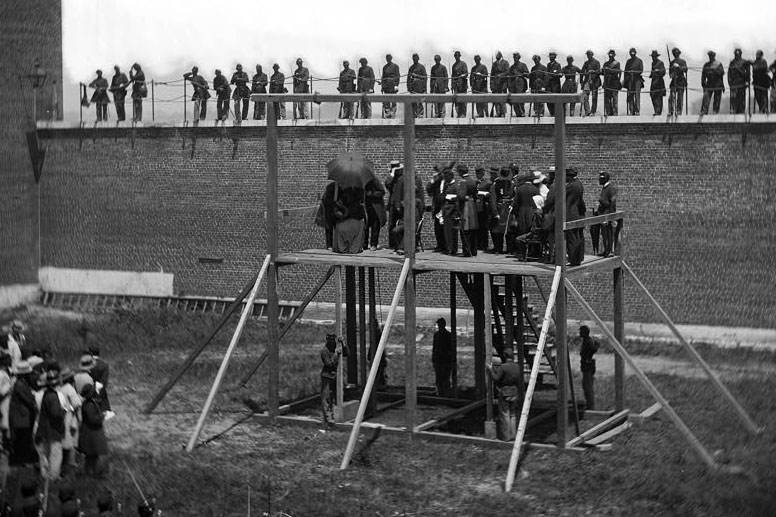

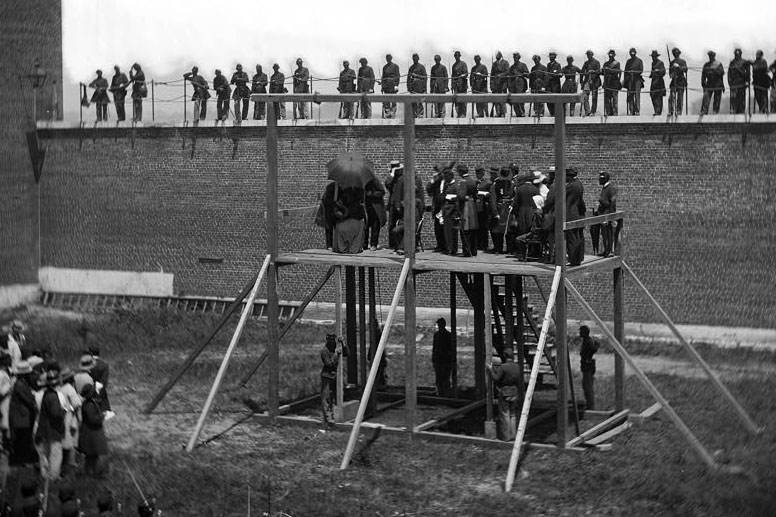

Several leading rebels ended up being trialed for war crimes and treason. Governor Vance was hanged for war crimes for his actions in Western North Carolina, a fate shared by Wade Hampton and Jeb Stuart, who was hanged in Harpers Ferry, the same place in which he had stood during John Brown’s execution. Howell Cobb and Robert Barnwell Rhett were hanged as traitors for having served in high positions in the US government and then joining the rebellion. Even some who obtained clemency because they had surrendered themselves received step penalties, such as Joseph Brown, condemned to 10 years of imprisonment, or Joseph E. Johnston, who was saved by the hangman only by Sherman’s intervention and then condemned to 20 years of imprisonment, having served only ten years when his health failed, and he died in 1875. Anticipating such a fate and seeing the “government overthrown & the whole property of myself and my family swept away,” Edmund Ruffin preferred to imitate his former chief and shoot himself. Other rebels received greater clemency if they had given up in time, such as General Longstreet, who received a full pardon, or Henry Wise, who merely had to suffer the confiscation of his properties, both because they surrendered themselves after the Coup.

Post-war trials

Execution, however, was reserved only for the worst rebels, being used almost entirely against the architects of secession, supporters of the Junta, or war criminals. Most often, the Union enforced exile against the losers of the war. Due to Lincoln’s personal intervention, for example, Alexander Stephens was “allowed” to flee to England, where he would scrape a meager existence by advertising cheap products and being regarded as a curiosity by Europeans. Albert Sydney Johnston had his own sentence commuted to exile for having denounced the Junta, but, he observed later, it would have been preferrable to “die in my own native land than even live as a King in a foreign land.” Beauregard also echoed the American loyalist Thomas Hutchinson, writing in a bout of homesickness that he would rather “die poor and forgotten in my country than amidst honor and glory in another nation.” But this was a possibility forever closed – none of them would see the US again.

Others decided to exile themselves after their relatives received the Union’s justice. Thus, Varina Davis settled in England, denouncing how Lincoln had by “a single dash of the pen” wanted to “disrupt the whole social structure of the South, and to pour over the country a flood of evils.” Mary Breckinridge and her sons, after a brief stay in Kentucky, also decided to leave for Canada, writing that “I cannot bear the sight of this land - it isn’t home without my dear martyred husband.” Mary Boykin Chesnut also spent many months grieving how “our world has gone to destruction,” and wondering whether her husband “would be hanged as a Senator or as a General.” James Chesnut would be hanged as a Senator, the properties of his father then being confiscated, and Mary being given a small amount of money which she used to leave the country for France, where she would survive by publishing her memories (the first edition being in French). As she embarked, penniless and bitter, she saw enslaved people celebrating their freedom. “It takes these half-Africans but a moment to go back to their naked savage animal nature,” she observed in hatred. Gertrude Thomas, who had gone from a wealthy mistress to a bankrupted poor woman, also wished for a “volley of musketry” to be “sent among the Negroes who were holding a jubilee” in Georgia.

For the ruined planter class, Katherine Stone said, the “future stands before us dark, forbidding, & stern,” full of “all the bitterness of death without the lively hope of Resurrection.” Stone’s plight was familiar to those who had once ruled the South, for when she returned to her plantation in Mississippi, she found it already redistributed to the people her family had enslaved. Granted a forty-acre homestead by the Federal commander, the girl who had once enjoyed a life of ease and pleasure for the first time had to work for her own bread - a situation many planters found themselves in. Even Unionist planters like William J. Britton felt themselves ruined by the end of slavery and the policies of the Union in favor of equal rights. He took dark pleasure in seeing “the political mad caps who have destroyed our once prosperous and happy people Swing at the end of hemp,” only regretting how “our great man Toombs was not among the number.” Although the full form of the post-war settlement was to be determined, most planters could already tell that the balance of power had changed and could only brace for worse.

That the Revolution was just starting was also recognized in the North. As the Congress closed its December session, a lame duck Chesnut could only declare apprehensively that “the anti-slavery party is in power. We know it. We feel it.” The Lincoln administration had won the election and then the war on a platform calling for the destruction of slavery, equal rights for all Americans, and a throughout Reconstruction of the Union. The victory of the Union, Frederick Douglass declared, had been a necessary and glorious one, for the future and soul of the nation and the progress of humanity. “The world has not seen a nobler and grander war” than this Second American Revolution. While costly and full of sacrifice, this struggle had written “the statutes of eternal justice and liberty in the blood of the worst tyrants . . . We should rejoice that there was normal life and health enough in us to stand in our appointed place, and do this great service for mankind.” A former slave named Uncle Stephen made the same point with less eloquence but just as deep a feeling. “It’s mighty distressin’ this war,” he told Yankee soldiers, “but it ’pears to me like the right thing couldn’t be done without it.”

The Ruins of Richmond

Nonetheless, the victory of the Union had not settled the issues of the war, but only opened new challenges. The issues of the war were certainly not settled in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, where the famine and the Jacquerie were raging on. They were not settled in the Mississippi Valley and other large swathes of the South, where roving bands of marauders still stole from starving civilians and where order hadn’t been reestablished. They were not settled in many plantations where former masters tried to maintain slavery and were preparing to fight for a system of labor and racial subordination, even if it required violence. They were not settled in the Black belt, where new Black landowners found themselves attacked by terrorists that wanted to reverse the tide of the Revolution. They were not settled in the Upper South, where a deadly riot started when Kentucky troops attacked a group of Tennesseans that had been singing “Stonewall Jackson’s Way.” They were not settled in the North either, where William Lloyd Garrison tried to dissolve the American Anti-Slavery Society by declaring that its work was completed, only for Frederick Douglass and Wendell Philipps to take over it and adopt a new motto: “No Reconstruction Without Negro Suffrage.”

The United States had successfully passed through its greatest trial, maintaining its unity and nationhood in the face of a powerful rebellion. But new and perhaps more difficult trials were now dawning. The American Civil War was over, but it remained to be seen whether the United States could win the peace in the new Reconstruction Era.

The North accepted the war the South had started to maintain the integrity of the nation. For the Northern people, secession was chiefly a threat because a successful separation would eviscerate the unity and stability of the United States. What they believed to be the best government on earth, the source and guardian of their happiness and prosperity, would then collapse into several petty republics, and the American experiment would end. It was to prevent this that the soldiers of the Union Army fought. But everyone recognized the centrality of slavery to the conflict – both Union and Confederate soldiers knew that the South fought for slavery, and that the “way of life” Southerners claimed to defend would be one anchored in slavery and White supremacy. The average Northern soldier was not greatly concerned at first with overthrowing either, but they and their leaders soon realized that the Rebellion drew strength from the millions of people they forced to work for them. They, likewise, realized that the enslaved could be counted on as allies for the Union cause.

Yet, at this early stage, Northerners hesitated to turn the Civil War into a Revolution. Conservative men, opposed to secession but supporters of White supremacy, all dreamed of restoring the “Union as it was,” and insisting on prosecuting a war that disrupted slavery as little as possible. Lincoln was not one of these men. He and the Republican Party, from the first moment, predicted that Union victory meant the doom of slavery, for the Slave Power that had artificially protected it and guarded it from the natural march of progress, had been overthrown. As soon as the Southern States returned, the Republican policies of “Freedom National” would be implemented, and slavery put on the path of ultimate extinction. Free soil for the territories, abolition in the District of Columbia, the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, and Federal pressure on the Border States, all of these were adopted. But what would have been great anti-slavery achievements in the antebellum now proved insufficient, and the Union’s leaders had to recognize that the “inexorable logic of events” was now leading them towards Emancipation.

This momentous step couldn’t have been taken without the actions of the enslaved people themselves. Southern masters who had convinced themselves that the people whose liberty they robbed were happy and loyal, suffered a rude awakening as the war started. Far from what the enslavers had believed, Black people struggled mightily to obtain their freedom, offered their help to Federals that in many cases remained reluctant, and defied the power of the slaveholders. This did not, at first, happen through slave insurrection, for the enslaved recognized that the increasingly repressive Southern State had the necessary force to repress any violent uprising, making any such attempt nothing short of suicidal. Nonetheless, Black people opened a “second front” at the very heart of the Confederacy as they fled to the Union’s lines; offered their services as laborers, spies, and soldiers; and resisted the power of the slaveholders by refusing to work or demanding payment. As a State founded on slavery, the Confederacy had to resist this challenge, but it still sapped resources and manpower it could not afford.

The Victory of the Union

Thus, the Union accepted Emancipation chiefly as a military policy that would weaken the Confederacy while allowing it to gain greater strength by recruiting the formerly enslaved as allies in the struggle. But this should not be understood as merely a desperate policy Lincoln had no other option but to adopt. The administration had stricken back against slavery since the start, and at every crucible, at every choice between policies that weakened slavery and those that upheld it, Lincoln chose the option that furthered human freedom. Certainly, many Northern politicians and generals disagreed with the government’s interpretation of the war and believed that a conciliatory policy would be better. If it were up to men like Douglas and McClellan, the Union Army would have enforced the Fugitive Slave Act, would have never enlisted Black soldiers, would have never adopted the kind of policies that augured a Revolution in Southern life. Consequently, the gradual, painless, compensated emancipation all but the most Radical abolitionists had envisioned in 1860, had already given way to a complete, violent, and immediate destruction of slavery by military power in 1862.

The conservative dream of completely separating the war from slavery was over, and from then on, the United States Army fought not merely for Union, but also for Liberty. Again, this was not something incidental, for the war started a process of radicalization against slavery and then against White supremacy within the Northern people. Seeing the horrors of slavery up close, and identifying the Southern Slavocracy as the responsible for the conflict, Northerners started to feel a deeper moral revulsion against slavery than ever before. This wouldn’t have been possible without the efforts of Black people and their Radical allies, who continuously pushed forward for imbuing the war with a greater moral significance. These campaigns of anti-slavery slavery agitation, plus seeing the value of Black people and their commitment to the Union cause in such great events as the Battle of Union Mills, all helped to transform the nation’s conception of Black people. By the end of the war, Northerners had become fully convinced that the perpetuity of the Union, but also the aims of justice and the survival of the national ethos of Liberty, required the eternal overthrow of slavery and a true effort at Equality for all. The Civil War, then, had become the Second American Revolution.

This Revolution frightened Southerners. The Confederacy was a fundamentally counterrevolutionary effort, which sought to preserve the structure of antebellum Southern society, one dominated by the slaveholder elite, against the terrifying challenge Northern abolitionists presented. However, the South was not united in this effort. The question of the Confederacy’s legitimacy and its claim of democratic government is one that has been debated countless times. One must not forget that there were at least four million abolitionists that the Southern elite did not take into account when the secession movement started. Yet even beyond them, secession was not unanimously accepted by Southern Whites. Hundreds of thousands would resist the Confederacy, fighting in blue uniforms or as Unionist guerrillas, and defying the slaveholders’ pretensions to make them give up their properties and lives for a cause which seemed only to benefit the elite. Especially because that elite seemed unwilling to make the necessary sacrifices, resisting bitterly and shortsightedly every attempt to make them give up any of their “rights.” Deep cracks in Southern society were exposed and grew more pronounced as the war continued and the sacrifices asked of the poor increased.

The Southern masters responded to this challenge in the same way they responded to Black attempts to reclaim their freedom: with brutal repression. Throughout the war, the Confederacy and its Armed forces acted swiftly and ruthlessly against Unionists, persecuting, massacring, and attacking them. The sorry tales of repression in East Tennessee and Western North Carolina are examples. The Confederacy employed similar methods to stamp out defiance amongst the enslaved, who were used to being driven from their homes and murdered by White power structures. In this way, the continuous, aggressive State violence needed to maintain slavery and the power of the planter aristocracy was exerted, and the South answered to the North’s radicalization by radicalizing itself, taking increasingly appalling measures to maintain its power. And those great libertarians like Robert Toombs and Alexander Stephens, who spoke so often and so bitterly against tyranny and for constitutional government, never challenged this repression. Because, to the leaders of the South, violence to enforce their “rights” was always good, whereas any challenge to their power, no matter where it came from, was completely unacceptable.

This meant that ultimately the government of John C. Breckinridge also became unacceptable to those who held power within the Confederacy. Committed to a successful prosecution of the war above all else, the Breckinridge regime employed all the methods thus described to enforce the power of the Confederate State, but also sought to lessen the burden upon the poor and push the wealthy to make the necessary sacrifices. The Administration thus faced planters that fought against impressment of goods and enslaved laborers, resisted his intromission in local government and obstructed the prosecution of the war, and above all believed that Breckinridge was not adequately protecting slavery. All because these measures attempted against the power they held to be sacred and untouchable. And thus, Breckinridge to them became the worst tyrant in history not because of what he did to Unionists or Black people, but because he dared to tell them what to do.

The Defeat of the Confederacy

This culminated in the so-called “Five Monstrous Decrees” and the attempt to recruit Black soldiers, both hard blows against slavery that nonetheless failed to save the Confederacy, which tottered in the brink of destruction after the Union victories in Atlanta and Mobile. Knowing that further resistance was hopeless, Breckinridge then tried to surrender, hoping that a negotiated peace may yet save White supremacy or even slavery. But even this the planter aristocracy could not countenance. Deciding that it was better to be utterly destroyed than to voluntarily give up their “rights,” they overthrew Breckinridge and then executed him, cleaving Southern society in two and alienating the poor Whites who had seen him as their protector. In this Southerners were merely repeating history, for it was this same pride and arrogance that had resulted in secession. And just like how secession had only brought about the very revolution they had wanted to avoid, more radical and immediate than it could have been otherwise, the coup against Breckinridge only assure that the war would go until it destroyed the Confederacy. The same suicidal instinct that had made them unable to accept Lincoln, made them reject Breckinridge, and thus assured their complete perdition.

The result was a bloody, horrifying fiasco, just as Breckinridge had predicted. The South’s collapse resulted in famine extending through the Southern countryside and a breakdown of order, leading to anarchic Jacqueries that claimed thousands of lives more. This assured that the Civil War would be the deadliest conflict in American history, and one of the bloodiest in the history of the world. Over 650,000 Union soldiers died in the struggle to maintain the nation, and a further 500,000 Confederate soldiers, most of disease. Famine, anarchy, and disease, extending beyond the end of the war, all claimed some 100,000 civilians in Union-areas, while over 500,000 thousand Confederate civilians died. The 1.8 million people that died in the war represented 5.8% of the US population, and, staggeringly, over 10% of the Confederate population and over 40% of its White males of military age. The war had further reduced the South to an “economic desert,” making the South go from 30% of the nation’s wealth to less than 10%. It also fundamentally changed the dynamics of power – never again would the South domineer over the Federal government as it once did, but instead the US entered a period of Northern, and more specifically Republican, dominance.

The most inescapable fact of Southern defeat was the destruction of slavery. Unlike what Northerners had believed, slavery proved to be a sturdy institution, requiring powerful military blows and a concerted effort until it was destroyed. The legal end of slavery throughout the nation did not come until June 1865, when the Reconstructed government of Mississippi ratified the 13th amendment, securing emancipation in the South and starting it in Kentucky and Delaware, both of whom clung to the institution. The actual end of slavery came on the ground, as Union soldiers started an occupation of the South and enforced emancipation at gunpoint. But the military and unconditional defeat of the Confederacy had already assured the outcome, granting their freedom to over four million of human beings and revolutionizing Southern life. “Society has been completely changed by the war,” observed a Louisiana planter. “The [French] revolution of '89 did not produce a greater change in the 'Ancien Régime' than this has in our social life.” And he was completely right – the American nation would never again be the same.

The “vaunted world of privilege and power” that the Southern elites had enjoyed and sought to protect now came crashing down around them as the victorious Union enforced emancipation, land redistribution, and justice against the leading rebels. “The props that held society up are broken,” said the daughter of a former planter, as she observed these changes. The once “rich, hospitable, powerful, are now poor, and like Samson of old shorn of their pride and strength,” grieved a Mississippian. Katherine Stone gasped in horror at the idea of “submission to the Union (how we hate the word!), confiscation, and Negro equality.” Sarah Morgan believed for her part that it would be best for Southerners to “leave our land and emigrate to any desert spot of the earth.” Some rebels followed her counsel and fled the country, never to return, the most prominent of them being General Beauregard. E. Kirby Smith and some of his lieutenants fled to Mexico; Judah P. Benjamin and others preferred Europe, while other communities tried to relocate to Brazil or Cuba. Some 50,000 rebels left the country, convinced by the fate of those who stayed that this was the right choice.

Several leading rebels ended up being trialed for war crimes and treason. Governor Vance was hanged for war crimes for his actions in Western North Carolina, a fate shared by Wade Hampton and Jeb Stuart, who was hanged in Harpers Ferry, the same place in which he had stood during John Brown’s execution. Howell Cobb and Robert Barnwell Rhett were hanged as traitors for having served in high positions in the US government and then joining the rebellion. Even some who obtained clemency because they had surrendered themselves received step penalties, such as Joseph Brown, condemned to 10 years of imprisonment, or Joseph E. Johnston, who was saved by the hangman only by Sherman’s intervention and then condemned to 20 years of imprisonment, having served only ten years when his health failed, and he died in 1875. Anticipating such a fate and seeing the “government overthrown & the whole property of myself and my family swept away,” Edmund Ruffin preferred to imitate his former chief and shoot himself. Other rebels received greater clemency if they had given up in time, such as General Longstreet, who received a full pardon, or Henry Wise, who merely had to suffer the confiscation of his properties, both because they surrendered themselves after the Coup.

Post-war trials

Execution, however, was reserved only for the worst rebels, being used almost entirely against the architects of secession, supporters of the Junta, or war criminals. Most often, the Union enforced exile against the losers of the war. Due to Lincoln’s personal intervention, for example, Alexander Stephens was “allowed” to flee to England, where he would scrape a meager existence by advertising cheap products and being regarded as a curiosity by Europeans. Albert Sydney Johnston had his own sentence commuted to exile for having denounced the Junta, but, he observed later, it would have been preferrable to “die in my own native land than even live as a King in a foreign land.” Beauregard also echoed the American loyalist Thomas Hutchinson, writing in a bout of homesickness that he would rather “die poor and forgotten in my country than amidst honor and glory in another nation.” But this was a possibility forever closed – none of them would see the US again.

Others decided to exile themselves after their relatives received the Union’s justice. Thus, Varina Davis settled in England, denouncing how Lincoln had by “a single dash of the pen” wanted to “disrupt the whole social structure of the South, and to pour over the country a flood of evils.” Mary Breckinridge and her sons, after a brief stay in Kentucky, also decided to leave for Canada, writing that “I cannot bear the sight of this land - it isn’t home without my dear martyred husband.” Mary Boykin Chesnut also spent many months grieving how “our world has gone to destruction,” and wondering whether her husband “would be hanged as a Senator or as a General.” James Chesnut would be hanged as a Senator, the properties of his father then being confiscated, and Mary being given a small amount of money which she used to leave the country for France, where she would survive by publishing her memories (the first edition being in French). As she embarked, penniless and bitter, she saw enslaved people celebrating their freedom. “It takes these half-Africans but a moment to go back to their naked savage animal nature,” she observed in hatred. Gertrude Thomas, who had gone from a wealthy mistress to a bankrupted poor woman, also wished for a “volley of musketry” to be “sent among the Negroes who were holding a jubilee” in Georgia.

For the ruined planter class, Katherine Stone said, the “future stands before us dark, forbidding, & stern,” full of “all the bitterness of death without the lively hope of Resurrection.” Stone’s plight was familiar to those who had once ruled the South, for when she returned to her plantation in Mississippi, she found it already redistributed to the people her family had enslaved. Granted a forty-acre homestead by the Federal commander, the girl who had once enjoyed a life of ease and pleasure for the first time had to work for her own bread - a situation many planters found themselves in. Even Unionist planters like William J. Britton felt themselves ruined by the end of slavery and the policies of the Union in favor of equal rights. He took dark pleasure in seeing “the political mad caps who have destroyed our once prosperous and happy people Swing at the end of hemp,” only regretting how “our great man Toombs was not among the number.” Although the full form of the post-war settlement was to be determined, most planters could already tell that the balance of power had changed and could only brace for worse.

That the Revolution was just starting was also recognized in the North. As the Congress closed its December session, a lame duck Chesnut could only declare apprehensively that “the anti-slavery party is in power. We know it. We feel it.” The Lincoln administration had won the election and then the war on a platform calling for the destruction of slavery, equal rights for all Americans, and a throughout Reconstruction of the Union. The victory of the Union, Frederick Douglass declared, had been a necessary and glorious one, for the future and soul of the nation and the progress of humanity. “The world has not seen a nobler and grander war” than this Second American Revolution. While costly and full of sacrifice, this struggle had written “the statutes of eternal justice and liberty in the blood of the worst tyrants . . . We should rejoice that there was normal life and health enough in us to stand in our appointed place, and do this great service for mankind.” A former slave named Uncle Stephen made the same point with less eloquence but just as deep a feeling. “It’s mighty distressin’ this war,” he told Yankee soldiers, “but it ’pears to me like the right thing couldn’t be done without it.”

The Ruins of Richmond

Nonetheless, the victory of the Union had not settled the issues of the war, but only opened new challenges. The issues of the war were certainly not settled in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia, where the famine and the Jacquerie were raging on. They were not settled in the Mississippi Valley and other large swathes of the South, where roving bands of marauders still stole from starving civilians and where order hadn’t been reestablished. They were not settled in many plantations where former masters tried to maintain slavery and were preparing to fight for a system of labor and racial subordination, even if it required violence. They were not settled in the Black belt, where new Black landowners found themselves attacked by terrorists that wanted to reverse the tide of the Revolution. They were not settled in the Upper South, where a deadly riot started when Kentucky troops attacked a group of Tennesseans that had been singing “Stonewall Jackson’s Way.” They were not settled in the North either, where William Lloyd Garrison tried to dissolve the American Anti-Slavery Society by declaring that its work was completed, only for Frederick Douglass and Wendell Philipps to take over it and adopt a new motto: “No Reconstruction Without Negro Suffrage.”

The United States had successfully passed through its greatest trial, maintaining its unity and nationhood in the face of a powerful rebellion. But new and perhaps more difficult trials were now dawning. The American Civil War was over, but it remained to be seen whether the United States could win the peace in the new Reconstruction Era.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: