You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"Here is a bad joke of mine, a bit outdated, but what the hell:Allowed. Here's a good one:

The wall between Heaven and Hell has crumbled. As a result, God and the Devil hold a meeting, to see who has to pay for it, but they can't agree. So, they decide to reunite later now with their lawyer. The Devil arrives with the best lawyers, but God tells him the meeting is cancelled and that he will pay for the wall. "Why?" asks the Devil. "Because there are no lawyers in Heaven!"

What is lawyer’s favorite sweet? A: Nose candy.

I present to you, carbon-based lifeforms of AH.com, the Kirby-Smithdom National Anthem:

yeah if i had to go with a guiding song, i'd pick a song from crazy ex gf too, that show has a song for a lot of scenariosAlso, my guiding song

My sister got me a cool book for Christmas by Brian Kilmeade, who wrote a book you might enjoy for your research, @Red_Galiray , "The President and the Freedom Fighter," about the relationship between Lincoln and Douglass. You might already have it but I thought I'd let you know.

so in our timeline George Thomas’ family disowned him, refused money he sent to help him post war. If they survive the war /famine are the going to be desperate enough to at least acknowledge him?

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing!

The common wisdom amongst historians of the Civil War is that, if the falls of Atlanta and Mobile secured the continuance of the Lincoln government and the end of the Breckinridge regime, the October Coup secured he destruction of both the Southern Secessionists and the Northern Copperheads. For the latter group, it was because the Coup demolished all possibilities of a negotiated peace, making Lincoln’s platform of unconditional victory the only possible choice. Prospects for defeating Lincoln had seemed so bright before; after the victories, with the Chesnuts fatally and permanently fracturing, they were bleak; and after the Coup, opposition was hopeless. Consequently, what could have been a hard-fought campaign that would force Lincoln back to the center, became a crushing victory for an increasingly radical Party, which saw the results as a thorough endorsement of their program. The 1864 US elections thus confirmed the ascendancy of the Republicans, the Northern people’s desire for victory and Reconstruction, and gave the Union leaders’ the political capital and confidence to follow the course of the Second Revolution.

As detailed previously, that Revolution had already been underway, and it was just picking up steam as the Confederacy continued its collapse and the United States reasserted its authority. By then Reconstruction had gone beyond a mere project to place Loyalists in positions of power, for the Northern people had started to envision a thorough remaking of the social and economic fabric of Southern society. Given that the coup and the latest Union victories had convinced the Northern people that victory was at last at hand, the campaign quickly became one focused more on the future peace than the still raging war. Were rebels to be completely excluded from the Reconstruction governments? Conversely, were Black men to be included in them? How should loyalty be defined? Was the expanded National State, with its national police force and Bureaus managing labor and land, to become a permanent fixture of the American government? Or were those war-time expedients that had to give way to a retreat from centralization as soon as peace came? It was around these issues that the Republican Party and its three Chesnut opponents waged the campaign.

Far from a campaign based solely on the opinions and sensibilities of White people, the 1864 campaign for the first time in the history of the Republic allowed Black people to take a central role. Even though the small Black population in the Northern states for the most part could not vote, Black men were able to take part in elections in many of the Reconstructed states, albeit in a limited basis. More importantly, Black communities mobilized to afford essential support to the Lincoln government, fight against the racist and reactionary attacks of the Northern conservatives, and convince White people of both the justice and viability of Reconstruction. In this regard, this election was the Black community’s first opportunity to seize a space within the body politic. Whereas slavery had by design alienated the enslaved from the public sphere and State authority, now the freedmen showed their capacity and willingness to keep fighting for their rights and to influence the post-war world. This was, effectively, a rehearsal for Reconstruction, demonstrating the aims, foundations, and methods of Black activism for the incoming new era.

Before the reconstruction of the Southern states, the first step contemplated by the freedmen was the reconstruction of Black communities. What historian Steven Hahn has described as the “threads of slave politics,” that is, the social, familial, and community ties that helped Black people endure and resist slavery, were being both reconstituted and reinforced now that the chains were struck off. These fragile threads had been easily broken by the violent structures of slavery, the clearest and perhaps cruelest example being how slave families were routinely broken by enslavers. For many, the chief blessing of freedom was legal protection for their family units, because as the child Charlie Barbour said, emancipation meant that “I won’t wake up some mornin’ ter fin’ dat my mammy or some ob de rest of my family am done sold.” Military chaplains, Northern missionaries, and Bureau agents all helped in the work of legally consecrating Black marriages. In Tennessee, for example, John Fisk conducted a mass wedding that united 119 couples, and Bureau agents all over the occupied South could remember a continuous stream of Black people seeking to register their marriages, become the legal guardians of the children of relatives or friends, and pleading for help in finding their loved ones.

Bureau organized weddings in Vicksburg

Northern agents bore witness to both heart-warming and heart-breaking scenes, observing either joyful reunions or deep sorrow when someone couldn’t be found. “I wish you could see this people as they step from slavery into freedom,” wrote a Union officer to his wife. “Men are taking their wives and children, families which had been for a long time broken up are united and oh! such happiness. I am glad I am here.” But the same agent then testified of a Black man who had walked all the way from Tennessee to Louisiana to try and find relatives that had been sold over 20 years prior to the war. Such a sight “reduced me to weeping,” the officer admitted. Often, it was necessary to use force to reunite families. Union Army units, mostly the Home Farm regiments, or even Unionist guerrillas helped to emancipate family members who were still living under slavery. One such event took place in Lynchburg, Virginia, where a detachment of Federal cavalry arrived at the farm of B.E. Harrison, the former owner of one of the troopers. Though this cavalryman had escaped to and joined the Union Army, he had had to leave his wife and child behind. But now the father had returned, “with a cavalry saber in his hand,” to demand the return of his family, pledging to torch the place when Harrison said that he had already “refugeed” both of them.

Once their families had obtained legal recognition, most Black people then turned to education as another great priority. Already by the fall of 1861, the American Missionary Association (AMA), had sent missionaries into the contraband camps to educate the former slaves, and soon it was joined by several more such organizations. In 1863, the newly minted Freedman’s Bureau took over the education of the freedmen, but it maintained its collaboration with these Northern missionaries, with the explicit objective of socially transforming the South. Freedmen almost immediately embraced education as a way to better themselves and their communities. “They are anxious to have their children well educated,” noted a Yankee. A Louisiana freedman demonstrated when he declared that “Leaving learning to your children was better than leaving them a fortune; because if you left them even five hundred dollars, some man having more education . . . would come along and cheat them out of it all.” Black people, it was evident, realized that being educated was key to their future success, and as a result threw themselves wholeheartedly into founding schools with the help of the Freedman’s Bureau and recruiting teachers from the ranks of the Northern missionaries.

By late 1864, Bureau schools dotted the South, the seeds of a larger process that built the first public education system in the region after the war. During it, most schools were instead temporary ones set up in Union-occupied cities and in redistributed plantations. But these still provided the opportunity for learning, and the enthusiasm of the freedmen quickly surpassed even the most optimistic predictions. Black children “can learn to read and write as readily as white children,” reported Union officers. They “are smart, bright and quick to learn, and one can scarcely observe any difference in the rate of progress.” Black adults were just as eager to learn as their children, Lucy Chase stated, saying she had never seen “such greedy people for study . . . they are all very anxious to learn and full of ambition.” Black laborers would attend schools after their workdays were done, often learning alongside their children, and a salient point in most labor disputes mediated by the Labor Bureau was demands for the establishment of schools and allowance of time for learning. In a report a Union General included a comment by a Black child summarizing this progress: “Massa, tell ‘em we is rising!”

Black soldiers were also noted for trying to achieve literacy, establishing regimental schools, and seizing all available opportunities for education. "So ardent were they," a colonel exclaimed, "that they formed squads and hired teachers, paying them out of their paltry means.” “The colored troops carried [lesson] books with them when the army marched,” said a chaplain, their “cartridge box and spelling book attached to the same belt.” Altogether, as the commander of a USCT Mississippi regiment said with evident pride, the progress of the freedmen in “acquiring the rudiments of a common education,” was “under the circumstances truly wonderful.” But Black soldiers were not merely learning to read and write – they were also receiving an education on political issues and took their place in the work of building a Black consciousness and carving a place within the Nation. The effect of a few months of “soldiering” left a White missionary “astonished,” for the “cringing, dumpish, slow . . . are now here . . . wide awake and active.” Thomas Wentworth Higginson similarly observed how “the general aim and probable consequences of this war are better understood in [a USCT] regiment than in any white regiment.”

This political education and mobilization wouldn’t have been possible without the aid of the organizations that became the pillars of the Reconstruction-era Black community: the Union League, the Church, and Charitable Associations. Although all of these would fully flourish only after the end of the war, while it raged the seeds were already being sown. Several Home Farms and Federally occupied cities organized different associations bearing names like “Loyal League,” “Equal Rights Association,” or “Club of the Colored Union People,” that have all been gathered under the umbrella of the Union League. Organized with the approval or even the assistance of Federal commanders and Bureau agents, the Union Leagues were meant to educate the freedmen in the responsibilities of a citizen, facilitate the establishment of the Republican Party in the Reconstructed South, and mobilize the support of Loyalists to grant both legitimacy and stability to the new order. The first wave of Union League activity then came in the Border States, Louisiana, and Tennessee, the areas where the revolution had achieved the deepest inroads, as the limited number of Black voters marshaled to bring support to Lincoln, not only through their own ballots but also by actively fighting the opposition tickets.

Bureau schools in the South

The Union League, however, was merely one vehicle of Black organization, for emancipation also allowed Black communities to take charge of their community affairs, chiefly, religious practice. Under slavery, Black people had worshipped in Churches under White control, often being indoctrinated to believe slavery was ordained by God. The enslavers were never truly successful, for Black people still gathered in secret to hold their own religious meetings, incorporating West African spiritualism and a millennialist outlook that predicted future liberation. The coming of the war was then seen by Black people as a “fulfillment of the prophecies.” Emancipation allowed Black people to build and consolidate their own Churches, which besides places of worship also became places of learning and community organization. Black ministers especially took on an important role as leaders, not only spiritual, but political and social, settling disputes, representing their communities before the Federal authorities, and later organizing the Republican Party and Union Leagues and even running for office. This was a politicization of Black religion that would continue and intensify during Reconstruction.

It was not only men that participated in the building of Black communities and consciousness, for women also readily took to politics and social organization – even over the objections of Black men. Under slavery, Black men had been deprived of the role expected of males in the midcentury United States as heads of households, breadwinners, protectors, and disciplinarians. The advent of Union rule not only brought freedom, but also “northern gender norms” for the Union granted Black men a patriarchal role, designating them as “heads of households” for the redistribution of lands, the signing of labor contracts, and Federal service. The fact that the freedom of Black wives, mothers, and children depended on the service of their Black male relatives further contributed to subordinating Black women to Black men. Yet, women refused to retreat to a purely domestic sphere. With the men off to fight or organized in Army units or paramilitary groups, women took over the responsibility of managing Home Farms and redistributed plantations. But Black women were also present in Churches, Union Leagues, and Party conventions; and marched together with the men to demand land, improved working conditions, or make their voices heard before the Federal authorities.

The questions regarding the organization of land and labor were also far from settled. While the progress of land redistribution was nothing short of astounding, many lands remained under the control of Unionist planters who, nonetheless, still struggled to adapt to the new order. These men, General John P. Hawkins complained, “cared nothing how much flesh they worked off of the negro provided it was converted into good cotton.” General Eaton likewise denounced how their motives “involved patriotism or humanity only as secondary and incidental considerations,” making money being their primary objective “whether the Union cause – not to mention the Negro – suffered.” Tensions especially flared up in Louisiana, where relative early Federal occupation, strong conservative Unionism, and the desire of the Hahn-Banks regime to court planters resulted in many pro-planter measures contrasting sharply with developments elsewhere. Even in those areas where the freedmen were acquiring greater rights by the hands of sympathetic Federals and progressive Philadelphia policies, planters still resisted bitterly. “It is disheartening,” a Bureau agent observed, “to see those who call themselves Union men asking for whips and overseers.”

The new militancy of the Black population, however, meant they continued to resist these arrangements. A provost marshal reported how the freedmen would “not endure the same treatment, the same customs, and rules – the same language – that they have heretofore quietly submitted to.” Wherever they had to work under White authority, “the negroes band together, and lay down their own rules, as to when, and how long they will work etc. etc. and the Overseer loses all control over them.” Even freedmen who had received redistributed land often resisted the continuous interference of Federal authorities, defying their pretensions to make them cultivate cotton or limit the size of their parcels. The nascent structures of the Black community helped in this resistance, for Churches and Union Leagues doubled as cooperatives for the acquisition and management of land or helped organize strikes or coordinate demands.

Towards the end of the war the increased organization and militancy of the Black community allowed them to affect State and even National politics. This was clearest in Louisiana, where Lincoln’s experiment of Reconstruction found itself assailed by Black citizens and Radicals that found it lacking. Lincoln had issued by Proclamations new guidelines and signed bills expanding the powers of the Bureaus to conciliate the Radicals, but he was still unwilling to change the fundamentally conservative Louisiana regime. Some “acquiescence” to planter interests would make “the deeply afflicted people in those States . . . more ready” to rejoin the Union, Lincoln hoped. But, as the New Orleans Tribune questioned, “given the hostility of these people to republican liberty . . . what is to become of the poor colored man if the Federal government removes its hand?” Lincoln still upheld his government, saying that if “the new government of Louisiana is only to what it should be as the egg is to the fowl, we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it.” Moreover, not admitting Louisiana would also mean rejecting “one vote in favor of the proposed amendment to the national constitution.”

Freedmen's meeting in Louisiana

A similar ambivalence was evident in the question of universal Black suffrage. While Lincoln maintained that those of “good conduct, meritorious services or exemplary character” should be allowed to vote, he expressed qualms about the idea of extending the franchise to all Black men without distinction. The government, assistant secretary of war Charles A. Dana said frankly, had no intention to create “a great negro democracy” in the rebel states. Acknowledging the presence of a few “worthy colored men,” Dana nonetheless believed that most Black people were “docile and easily led,” making it necessary to adopt “certain qualifications.” But qualified suffrage would leave the few Black voters hopelessly outnumbered by White voters that, even if loyal, would be unlikely to be friendly to Black aspirations. This could be observed, again, in Louisiana, where the reconstructed state government under Banks and Hanh had showed little regard or interest in Black aspirations. This was a bitter pill for the gens de couleur that had at first expected to assume a new leading position. They had neither been granted offices, nor influence. They could not “understand why former rebels are treated with friendliness” while they “are ignored, debased and humiliated,” in the words of one of them.

Notwithstanding this hesitation on the part of the Union leaders, Black people continued to organize politically to push for changes. On the 4th of July 1864, a massive convention of Black men met in New Orleans to celebrate the second anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and demand the extension of the vote to all Black citizens. Though dominated by the creole elite, to the point that “every question might be put to the house in English and French,” the convention was a truly radical one that embodied the “new political experiences and sensibilities” created by the revolution. The former slave and current Union Army captain James Ingraham, “the Mirabeau of the men of color in Louisiana,” stalwartly insisted that Black men “take a bold and general position” to “ask our rights as men.” Although “elected and sustained by Black votes,” the Legislature “has treated with contempt every bill which was in favor of us,” Ingraham declared. In consequence, they should demand universal suffrage from the national Congress, a resolution that carried an overwhelming majority.

A couple months later, in October 1864, the “most truly national black convention” opened in Syracuse, New York. Nine years after the last National Convention of Colored Men, which had closed amidst fighting and despair, this new convention extended a “hand of fellowship to the freedmen of the South” and demanded they be given their “fair share” of lands; praised the “unquestioned patriotism and loyalty of colored men” but demanded that they be accordingly granted the “full measure of citizenship;” and pushed for universal Black suffrage as merely their ”just claims.” The organization and militancy of the Convention so impressed Lincoln that he received a Black delegation in Philadelphia. Leading the delegation, Frederick Douglass denounced how the Republican Party remained “under the influence of the prevailing contempt for the character and rights of the colored man,” and asked Lincoln to both protect the few Black men who could already vote and seek to enfranchise more. Douglass was pleased by how Lincoln “showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him,” yet he resolved that pressure ought to continue until he fully embraced complete equality in all regards.

Nonetheless, a shift in the opinions of the Administration and the Northern States was already evident. Several Northern States eliminated at last their discriminatory laws, extended public education to Black children, and submitted referendums on the question of Black suffrage to the voters. Despite bitter complains by the planters, Lincoln refused to go back on land redistribution or the new prerogatives of the Bureaus, writing that “I wish the material prosperity of the already free which I feel sure the extinction of slavery in all its forms would bring.” At the same time the Administration adopted new measures to show its support for liberty and equality, sending a Black consul to Haiti; appointing Martin Delany a colonel and putting him in charge of the Bureaus in South Carolina; and releasing guidelines to assure “equal and respectful” treatment to “the colored citizens” by the Armed Forces and Bureaus. Teachers, for example, were prohibited from using “the vulgar and hurtful word nigger.”

But this progress resulted in an inevitable conservative reaction. The tide of the Revolution, hopeful and astounding as it was, could be reversed if Lincoln was defeated and a Conservative government took office. Black people could be despoiler of their farms and rights; plantation discipline could be reasserted; and the advance in aptitudes towards race and equality could be arrested. While the victories had been a hard coup against the Opposition, it was still entirely possible that the Northern people might decide that someone else other than Lincoln would be better at bringing the war to a conclusion or building a peace. The Administration and its allies could not rest on their laurels, especially if they expected the election to result in approval of its most radical departures in policy. Consequently, as the advocates of White supremacy and Restoration gathered to fight Lincoln, the supporters of Liberty, Equality, and a complete Reconstruction mustered to reelect Lincoln.

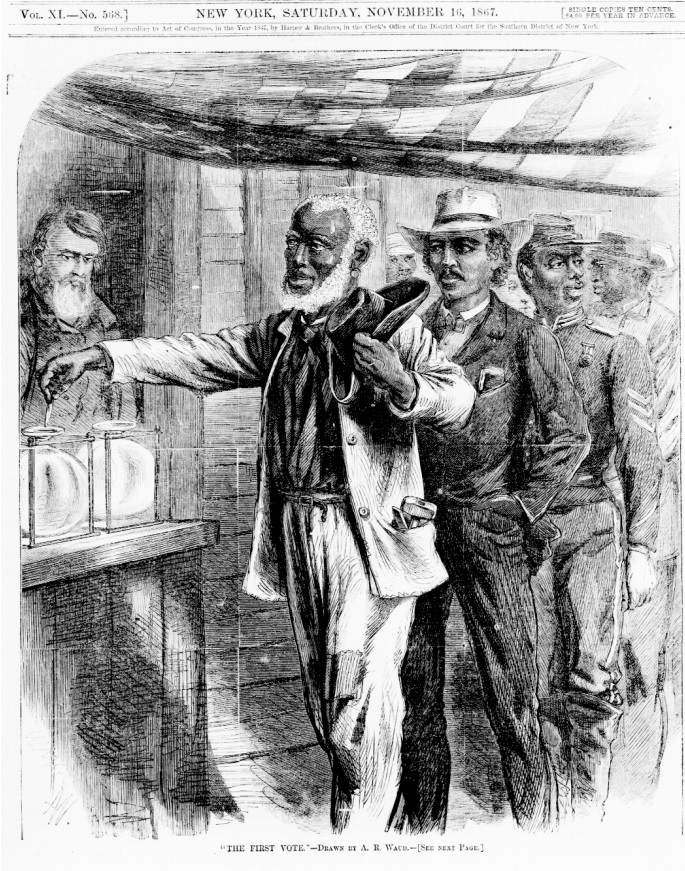

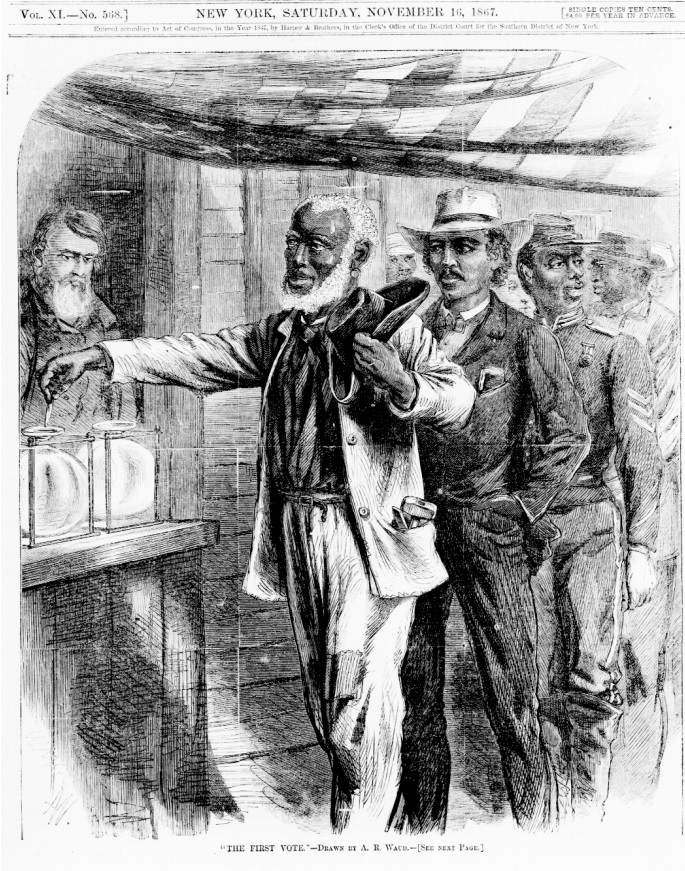

"The First Vote," depicting the prosperous farmer, educated mulatto, and brave soldier as examples of worthy voters of color

At the head of one of the opposition columns was Andrew Johnson. At first glance, Johnson had lived a life remarkably like that of Lincoln, being born in poverty in a Slave State and achieving prosperity and political success only later. Johnson, in fact, never attended even a frontier school, being taught to read as an adult by his wife. Known as the “Tennessee Tailor,” Johnson showed his talents in the rough world of the Tennessee stump, being elected to several offices including Governor before ultimately reaching the United States Senate. There he achieved initial distinction by being the only Southern Senator to remain loyal to the Union. At first, Johnson even gained a reputation for radicalism, emancipating his own slaves and working for emancipation in Tennessee, and denouncing the slavocrats. But Johnson’s inherent conservatism, inability to compromise, and inflexibility made Lincoln pass him over for the position of Tennessee’s Military Governor, a slight that Johnson never forgot and which he attributed to a vast conspiracy out to get him personally. Selected as the candidate of the National Union due to his unimpeachable loyalty, Johnson would soon grow bitterly reactionary and stubbornly uncompromising.

The head of the other opposition column was Samuel J. Tilden. A New Yorker who grew up in a world of influential politicians and merchants, Tilden obtained great wealth by shrewdly defending railroad and business interests. Initially a “Barnburner” that opposed the expansion of slavery, Tilden was disquieted by the Republican Party’s radicalism and strongly opposed Lincoln. Initially, Tilden had hoped to strike a moderate tone of reform, uniting Conservative Republicans and Moderate Chesnuts, but all his schemes had come to naught. Now forced to wage the campaign on his own, Tilden’s former political acumen suddenly disappeared. He now proved “hesitant, timid, and for the most part ineffective,” merging into the background instead of taking charge. Even his confidant John Bigelow had to sullenly admit that “Tilden took an inordinate amount of time to do things, complained childishly, and engaged in petty faultfinding,” making Bigelow “begin to have some misgivings whether he will prove equal to the labors of the Presidency.”

The last Chesnut faction could not even be truly considered a column, its numbers and strength so depleted by the latest events that it could serve as little more than a spoiler. These Copperheads gathered now under George H. Pendleton, a man with close Southern ties and sympathy for slavery. In fact, after the 13th amendment passed, Pendleton assured himself that “when the historian shall go back to discover where the original infraction of the Constitution was, he may find the sin lies at the door of others than the people now in arms,” all but stating that the Confederate rebellion was justified. Though one of the most prominent Copperheads, Pendleton now he found himself “without a platform to stand on,” for virtually no one believed that a negotiated peace could be concluded with the Confederate Junta. Instead, Pendleton swung to new issues of economic populism focused on the Midwestern States, where he promised to pay bonds in greenbacks and end the “system of financial robbery and rapine” that subordinated them to Eastern interests. This seeming disinterest in the current issues led a confused voter to ask: “does Pendleton know there is a war going on?” But they offered a glimpse into the future.

Pendleton’s mere presence resulted uncomfortable for both Tilden and Johnson, who spent a lot of energy and time distancing themselves from him and even denouncing him, time that could have been better spent attacking Lincoln. Johnson especially sought to portray himself as the War Candidate, asserting that he and his men “gloried in the victories of the Union while at the same time rejecting the Lincoln administration’s stewardship of the war effort.” The Johnson campaign maintained that winning the war had taken so long due to Lincoln’s “ignorance, incompetency, and corruption.” Lincoln and his Radicals were the “disunionists of the North” who had provoked the war in the first place, all his policies “calculated to extinguish every spark of Union sentiment in the Southern states.” Johnson, they said, represented on the other hand victory “without the disgrace of Negro aggrandizement.” Those “who believe that this is a white man’s government – that white men shall rule it, and that a white man, no matter how poor or low his condition . . . is as good as any negro in the land, will vote for Johnson and Franklin on the white man’s ticket.”

To bring this message to the masses Johnson in October went in a series of speeches throughout the Western and Border States, which has been called the Swing Around the Circle. Johnson denounced that land redistribution and Black suffrage could only result in “a tyranny such as this continent has never yet witnessed,” and a “relapse into barbarism.” Though he again called for “treason to be made odious and traitors punished,” in an angry harangue Johnson exclaimed that surely Thad Stevens and Wendell Philipps deserved to be hanged too, for they were just as “opposed to the fundamental principles of this government.” Responding to hecklers who called him a traitor Johnson with sour self-pity said that “I have been traduced, I have been slandered, I have been maligned. I have been called Judas Iscariot . . . Who has been my Christ that I have played the Judas with? Was it Abe Lincoln?" Asked about Reconstruction, Johnson snapped that Restoration would happen automatically without need for Congress, which had no power to impose anything on the Southern States anyway; intimated that proposing an amendment with States unrepresented was unconstitutional and revolutionary; and insinuated that if the Opposition gained enough seats, he’d recognize a “Counter-Congress” including Southern claimants.

George Hunt Pendleton

These speeches horrified even some of Johnson’s supporters, who called it “a tour it were better had never been made,” for it depicted Johnson at his worst, as undignified, erratic, and without a clear vision for Reconstruction. It also provided fodder to Tilden, who through the allied paper the New York Journal of Commerce pronounced Johnson’s tour “thoroughly reprehensible.” This was part of Tilden’s strategy to portray himself as a more moderate candidate, someone who’d defeat the Confederacy but would then inaugurate “a wise, conciliatory, healing policy.” Tilden spoke softly, accepting emancipation as a fait accompli but hinting at “necessary regulations,” and saying that the confiscation was right, but only if redistribution then benefitted Whites only. Adopting a tone centered on economics, Tilden’s men insisted that the “revival of agriculture, the safety of credit, and the restoration of commerce,” all required his victory. Tilden also charged that Lincoln supported the Bureaus and Black suffrage only as a massive scheme of patronage, whereby the government would maintain “lazy Negroes” on the taxpayer’s dime, and in exchange they would provide the ballots to keep in power the “shoddyocracy,” that is, Republican contractors and war profiteers who had artificially maintained the conflict to plunder the State coffers.

But as the campaign advanced, Tilden’s strategists started to believe that their fortunes depended on their capacity to invoke “the aversion with which the masses contemplate equality with the negro.” In effect, Tilden and Johnson started to compete to see which campaign could be more racist, with Tilden’s running mate Frank Blair taking the stump to denounce Reconstruction as military tyranny, warn that “the Negroes’ rape of government will lead to their rape of white women,” and declare that Radicalism made even “copperheadism” respectable. Even Tilden’s organ, the New York World, declared Blair’s tour “disastrous.” The attempt to portray himself as conciliatory had gone too far, and instead made it seem like Tilden was willing to restore the rebels to their properties and power, practically rewarding them for their rebellion. To try and repair damages Tilden refocused his campaign on economic issues, but in this regard the most marked differences were with Pendleton, whose platform Tilden denounced as a form of “repudiation” – a move that certainly did not endear him to Western farmers whose support he might otherwise have obtained.

Instead of successfully shaving off conservatives and moderates from the Lincoln coalition, then, Tilden ended up just competing with Johnson for the same demographic of reactionary racists, while at the same time appearing wobblier on the questions of the prosecution of the war and Reconstruction. Johnson, on the other hand, appeared like an unsatisfactory choice on all fronts. Due to the latest successes Lincoln’s prosecution of the war could not be called a failure, so Johnson’s pitch that he would be somehow a better commander in chief fell flat. As for Reconstruction, Johnson’s racist tirades went too far as well, for they seemed to promise that in the name of prejudice Johnson would prefer to see unpunished White rebels back in power than acknowledge any Black rights. A vote for Johnson or Tilden, Republicans declared, was a vote for “giving Toombs a seat in the Senate and a Georgia plantation.” By contrast, Lincoln seemed surer on the Reconstruction issue, not conceding to “vindictive and bloody plans,” but punishing the truly guilty while at the time seeking “conciliation for the brave, misguided democracy of the South who do not own a pound of human flesh.”

The in-fighting between Lincoln’s enemies also had catastrophic consequences for them at the local level, where they were unable to present a strong challenge to Republican officeholders and candidates. Whereas the old Democratic Party had had an established system of Party conventions and local machines, tensions between Buchaneers and Douglasites, and then War Chesnuts and Copperheads, had left most of these in tatters. Consequently, the Opposition often struggled to find candidates, and those candidates they found sometimes spent more time attacking each other than the united Republican ticket. Attempts to conclude fusion tickets were thus rather unsuccessful, and even when they succeeded the result could be just even more in-fighting, with Johnsonites and Tildenites throwing around accusations of being reactionary traitors or spineless cowards. These divisions, a conservative claimed later, “were the main cause of our defeat. They sacrificed the real men of the party, because neither had the magnanimity to yield and join his rival: rather than do this they put up men who had not the confidence of the party or the people.”

The Swing around the Circle

But if the Opposition remained divided on questions of war and Reconstruction, they were united by their racism. Charging that Lincoln’s Reconstruction was just a scheme to force “the equality of the black and white races,” conservatives from all three Chesnut movements appealed to Northern racism and fears of Black equality to obtain votes. A New York World pamphlet, Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, especially accused Republicans of being in favor of race mixing, illustrated through vulgar caricatures of Black men kissing White girls. In Philadelphia, they denounced, “Filthy black niggers, greasy, sweaty, and disgusting, now jostle white people and even ladies everywhere, even at the President's levees.” Even as they remained officially at odds, Johnson’s and Tilden’s men marched arm in arm through Northern cities carrying banners proclaiming “abolition philosophy: handcuffs for white men and shoulder-straps for negroes,” or depicting a “black man with a whip in his hand; before him a white man in a suppliant position.” Lincoln’s party, a Tilden speaker said, would not “be satisfied till they have the black man in the jury box, on the bench, in Congress, and in the State Legislature.” During these marches they intoned:

The widow-maker soon must cave,

Hurrah, Hurrah,

We'll plant him in some nigger's grave,

Hurrah, Hurrah.

Torn from your farm, your ship, your raft,

Conscript. How do you like the draft,

And we'll stop that too,

When old Abe leaves the helm.

In order to assure White Supremacy, all three Chesnut campaigns promised to stop land redistribution, Black suffrage, and Black equality. Johnson declared that all the “lazy, worthless vagrants,” would be forcibly rounded up and sent to plantations; while Tilden, despite his moderate front, still agreed that all “idlers and vagrants” had to be put to work or bound to “apprenticeships.” Chesnut speakers again and again denounced land redistribution as a “war on property” that would sooner or later result in confiscation in the North, where Republicans would “rob the white man of his property and bestow it on the negro.” To Johnson’s declaration that “negroes are incapable of self-government,” Blair answered that “only the white race has shown a capacity for building up governments.” Consequently, enfranchising them was not to be thought of. They dismissed Lincoln’s pretensions of moderation as “false pretenses . . . by the obscurities of the much-talked-of constitutional amendment, they concealed the real objects of the government,” which were the “centralization of powers,” and the “elevation of the Negro.”

In the face of these attacks, Republicans defended land redistribution as the necessary creation of “a new class of landholders who shall be interested in the permanent establishment of a new and truly republican system – the prize for which we are now fighting.” James A. Garfield similarly proclaimed that to “put down this rebellion so that it shall forever be put down . . . we must take away . . . the great landed estates of the armed rebels of the South.” But they also were not above appealing to racism, plainly stating that land redistribution was good because it would keep Black people in the South, whereas reversing it would cause a “vagabondage towards the north.” “If you want the Negro to stay where he belongs,” Republicans intoned, Northerners had to vote for Lincoln. The other angle of their appeal was that land redistribution was a just punishment for the planters who “started and sustained” the war, and that to stop the policy as Johnson and Tilden wanted would mean “restoring their power and influence and we shall have the Slave Power again lording over our people.”

Republicans proved far more ambivalent on the issues of Black suffrage and equality. Some Radicals completely pushed in favor of them, seeing the campaign as an opportunity to “educate the public mind up to the standard of universal suffrage.” But most Republicans remained equivocal, some insisting that equality was to be only civil but never political or social, and others outright declared that the Lincoln campaign meant “not negro suffrage—not confiscation—not harsh vindictive penalties; but the plan of conciliation of the President designed to be a final adjustment of our national difficulties.” The message could vary depending on the area, an Ohio Republican writing of how “In the [Western] Reserve counties, some of our speakers have openly advocated impartial suffrage, while in other places it was thought necessary . . . to oppose it.” This alienated some Radicals, notably Wendell Philipps who was never completely conciliated to Lincoln’s candidacy. “Mr. Lincoln’s offer of amnesty has been accepted by men with wealth in their hands and treason in their hearts,” Phillips denounced. “This is the class which rebelled to break the union, and their purpose is unchanged. Military defeat has not converted these men; the soreness of defeat is only added to the bitterness of their old hate.”

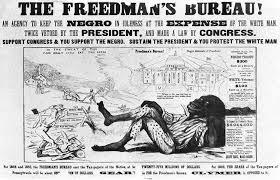

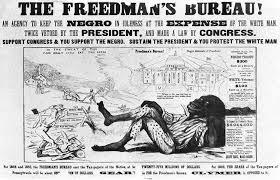

Conservative Propaganda against the Freedmen's Bureau

Frederick Douglass too complained of how the Republicans seemed “ashamed of the Negro” and preferred to talk of how their victory meant first and foremost the deliverance of White Southerners. But although he’d have preferred someone “of more decided antislavery convictions,” he believed “all hesitation ought to cease” when the choice was between Lincoln and those who would “restore slavery to all its ancient power . . . and make this government just what it was before the rebellion – an instrument of the slave-power.” Garrison acknowledged that the “whole of justice has not yet been done to the negro,” but Lincoln had still “struck the chains from the limbs of three millions and granted homesteads and rights to thousands” putting the nation “on its way to the full recognition of the quality and manhood of the negro before the law.” Lincoln, some more reluctant supporters said, was a “half friend of freedom” and a “fickle-minded man” who had embraced their cause only slowly, but he was still infinitely preferrable to his opponents. “There are but two choices facing the country,” John S. Rock declared, “Lincoln, who is for Freedom and the Republic, and his opponents, of varied names but of single purpose: Despotism and Slavery.”

Grassroots Black communities offered much stronger support. Black voters in Maryland, Missouri, and Louisiana, protected by Federal troops and Union League units, all marched to the polls “shouting and blessing your name,” a supporter communicated. Sojourner Truth was also received with “kindness and cordiality” by the President, the old warrior almost overwhelmed at shaking “the same hand that signed the death-warrant of slavery . . . I now thank God from the bottom of my heart that I always advocated his cause.” This reflected the support of Northern men of religion and letters, who united behind Lincoln with unprecedented unanimity. The Bishop Gilbert Haven for example called on men of religion to “march to the ballot-box, an army of Christ, and deposit a million votes for the true representative of freedom who shall give the last blow to the reeling fiend.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, usually aloof from politics, observed how “seldom in history was so much staked on a popular vote – I suppose never.”

Even more crucial for Lincoln was his continued and deep support among the Armed Forces. Republicans emphasized to soldiers that the Copperheads had “stigmatized them as . . . vagabonds and thieving marauders,” and wanted them “to stack their arms and stand by and practically surrender every advantage we have so bloodily won during the war.” They made much hay of how Chesnuts had opposed laws allowing soldiers to vote and stoke sentiments of vengeance by declaring that neither Tilden nor Johnson would punish the rebels who “had slaughtered and starved your gallant comrades.” Particularly after the coup, Republicans denounced Southern atrocities, such as the continued repression of Unionism and the terrible conditions in Southern prisons. In a widely printed report, Secretary Stanton spoke of “The enormity of the crime committed by the rebels” which “cannot but fill with horror the civilized world. . . . There appears to have been a deliberate system of savage and barbarous treatment.” Circulating photos of skeletal Yankee prisoners, Republicans asked “are you willing to forgive the guilty parties and negotiate with them as Andy and Samuel propose?”

More than a simple desire for retribution was at work for the Army’s support for Lincoln, however. As James McPherson writes, the racist appeals of the Chesnuts failed to resonate in part because “many northern voters began to congratulate themselves on the selflessness of their sacrifices in this glorious war for Union and freedom.” The soldiers, an Ohio soldier and former Democrat said, believed “it would be more honorable to be buried by the side of a brave Negro who fell fighting for the glorious old banner than to be buried by the side of some cowardly Cur who proved himself recreant to the Boon of Liberty.” Convinced since the very start of the war that the cause of the Union was the cause of republican Liberty, Northern soldiers now took this to their natural conclusion and declared with pride that theirs was a fight to build a better nation. A Pennsylvania private thus wrote of how voting for Lincoln would preserve “this great asylum for the oppressed of all nations and destroy the slave oligarchy.” Another soldier declared he could “endure privations . . . for there is a big idea at stake . . . the principles of Liberty, Justice, and Righteousness.” Their comrades had “died fighting against cruelty and oppression,” said a New Yorker, proving “that our country is indeed the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

The North increasingly became convinced that the abolition of slavery was not a mere necessity, but a noble goal in and of itself

In this regard, the struggle to preserve the Union became inexorably linked with the struggle to free the Southern masses, Black and White, from the domination of the slaveholders. After the Coup, this view was only reinforced, as both Northern civilians and soldiers came to envision themselves as liberators, people who were righting the wrongs of their forefathers by at last building a Union “free of the blot of that blot upon our civilization,” as Lincoln said. This “Second Revolution,” a speaker declared, was even more glorious than the first, for now it would truly “result in the establishment of a perpetual republic of Liberty.” The previous generations had to compromise with the Slave Power, but now it had been “eternally overthrown,” and the “principle that all men are created equal,” had been vindicated at last, proclaimed a soldier. The Northern people thus came to decide that honorable victory and just peace entailed the destruction of the Southern slavocracy, the recognition of the bravery and service of Black people, and an effort to fulfill the national pledge of Liberty and Equality, balancing compassion for the deluded masses and justice against the guilty deluders. And the only candidate who could achieve that was Lincoln.

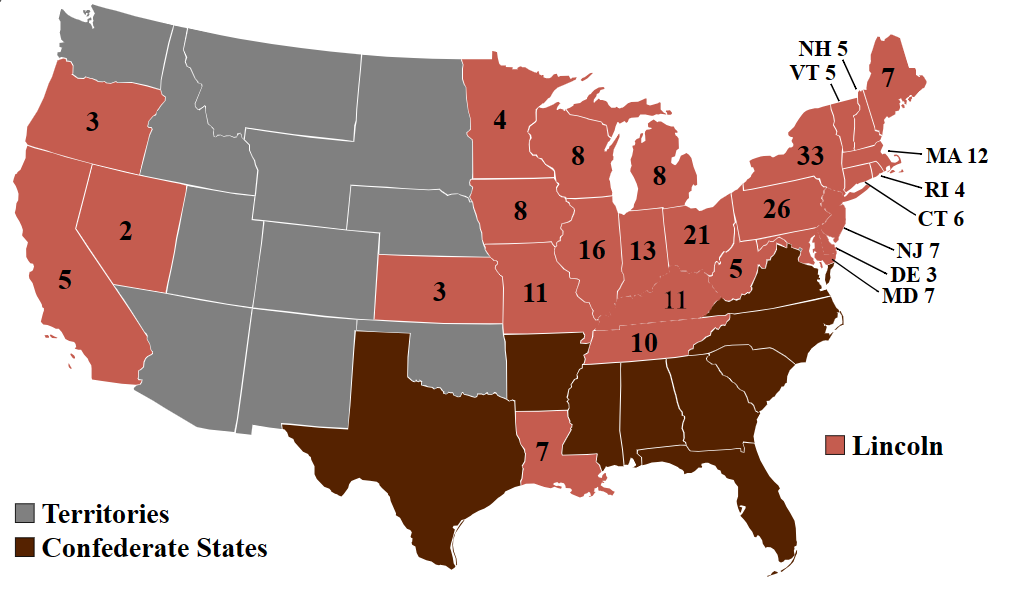

When the votes were counted, Lincoln had won 57% of the national popular vote, to Johnson’s 19%, Tilden’s 20%, and Pendleton’s 4%. This translated into a victory in every State of the Union. This included narrow pluralities in Kentucky and Delaware, where a combination of political chicanery and military fiat had suppressed the opposition’s divided votes, leading to unending debate over the legitimacy of the election. In all other States, however, Lincoln’s victory was complete, handily surpassing even the united total of the Opposition. In this he was helped by overwhelming support among the soldiers, who gave him almost 80% of their votes through absentee ballots and by being furloughed to go to their states and vote. While there is scattered evidence of intimidation by the Union League, in most States the results were a legitimate endorsement of the Administration and its policies. Lincoln celebrated the fact that the United States had been able to conduct a democratic election in the midst of war, nothing that “if the rebellion could force us to forego, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us.” In voting for him, Americans were voting “for the best interests of their country and the world, not only for the present, but for all future ages,” and vindicating the “great principles of liberty and republican government.”

“The crisis has been past, and the most momentous popular election ever held since ballots were invented has decided against treason and disunion,” celebrated George Templeton Strong. The country “has safely passed the turning-point in the revolutionary movement against slavery,” cheered Secretary Seward, who also took heart in Lincoln’s long coattails, which thanks to the enemy’s disorganization had carried Republicans to a 4/5ths majority in both Houses of Congress and control over every State of the Union, virtually obliterating the enemies of the administration. The referendums about Black suffrage also passed, albeit by narrower margins than Lincoln, enfranchising Black men in Connecticut, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Kansas, Ohio, and Iowa. "Isn't this just vindication after decades of opprobrium and degradation?" asked William Lloyd Garrison. Though Congress ultimately refused to count the votes in the Reconstructed States, Republicans still widely publicized the support Lincoln obtained with the Black voters there and in the Border States. Altogether, this was “the most decisive and emphatic victory ever seen in American politics,” The Nation declared, a triumphal endorsement of abolition and a complete Reconstruction of the Union.

Lincoln: 57% of the Popular Vote, and 212 (+17 invalidated) Electoral Votes

Tilden: 20% of the Popular Vote, and 0 Electoral Votes

Johnson: 19% of the Popular Vote, and 0 Electoral Votes

Pendleton: 4% of the Popular Vote, and 0 Electoral Votes

During the campaign the secessionists had insisted that the South could “depend upon no party at the North for the protection of their liberties and institutions,” and that the “old Democrats” were “united in the wicked and bloody policy of subjugation.” It did not truly matter who won the Northern election, hardliners insisted, to the point that some called Lincoln’s reelection preferable, for it would make Southerners realize that the choice was “between a perpetual resistance, and a condition of serfdom.” When she heard that “the vulgar, uncouth animal is again chosen to desecrate the office of Washington,” Emma Holmes likewise declared that “war there must be, until we conquer peace.” But these declarations were mere desperate grasping at straws. For most Southerners, Lincoln’s victory made a ripple of despair go through them. “Our subjugation is popular at the North,” sullenly declared Josiah Gorgas. With their enemy having proven both its willingness and power to defeat and destroy them, and their own government utterly incapable to defend them, most Southerners could only hopelessly conclude that the end was in sight, and that the disastrous farce Breckinridge had warned against had finally come.

As detailed previously, that Revolution had already been underway, and it was just picking up steam as the Confederacy continued its collapse and the United States reasserted its authority. By then Reconstruction had gone beyond a mere project to place Loyalists in positions of power, for the Northern people had started to envision a thorough remaking of the social and economic fabric of Southern society. Given that the coup and the latest Union victories had convinced the Northern people that victory was at last at hand, the campaign quickly became one focused more on the future peace than the still raging war. Were rebels to be completely excluded from the Reconstruction governments? Conversely, were Black men to be included in them? How should loyalty be defined? Was the expanded National State, with its national police force and Bureaus managing labor and land, to become a permanent fixture of the American government? Or were those war-time expedients that had to give way to a retreat from centralization as soon as peace came? It was around these issues that the Republican Party and its three Chesnut opponents waged the campaign.

Far from a campaign based solely on the opinions and sensibilities of White people, the 1864 campaign for the first time in the history of the Republic allowed Black people to take a central role. Even though the small Black population in the Northern states for the most part could not vote, Black men were able to take part in elections in many of the Reconstructed states, albeit in a limited basis. More importantly, Black communities mobilized to afford essential support to the Lincoln government, fight against the racist and reactionary attacks of the Northern conservatives, and convince White people of both the justice and viability of Reconstruction. In this regard, this election was the Black community’s first opportunity to seize a space within the body politic. Whereas slavery had by design alienated the enslaved from the public sphere and State authority, now the freedmen showed their capacity and willingness to keep fighting for their rights and to influence the post-war world. This was, effectively, a rehearsal for Reconstruction, demonstrating the aims, foundations, and methods of Black activism for the incoming new era.

Before the reconstruction of the Southern states, the first step contemplated by the freedmen was the reconstruction of Black communities. What historian Steven Hahn has described as the “threads of slave politics,” that is, the social, familial, and community ties that helped Black people endure and resist slavery, were being both reconstituted and reinforced now that the chains were struck off. These fragile threads had been easily broken by the violent structures of slavery, the clearest and perhaps cruelest example being how slave families were routinely broken by enslavers. For many, the chief blessing of freedom was legal protection for their family units, because as the child Charlie Barbour said, emancipation meant that “I won’t wake up some mornin’ ter fin’ dat my mammy or some ob de rest of my family am done sold.” Military chaplains, Northern missionaries, and Bureau agents all helped in the work of legally consecrating Black marriages. In Tennessee, for example, John Fisk conducted a mass wedding that united 119 couples, and Bureau agents all over the occupied South could remember a continuous stream of Black people seeking to register their marriages, become the legal guardians of the children of relatives or friends, and pleading for help in finding their loved ones.

Bureau organized weddings in Vicksburg

Northern agents bore witness to both heart-warming and heart-breaking scenes, observing either joyful reunions or deep sorrow when someone couldn’t be found. “I wish you could see this people as they step from slavery into freedom,” wrote a Union officer to his wife. “Men are taking their wives and children, families which had been for a long time broken up are united and oh! such happiness. I am glad I am here.” But the same agent then testified of a Black man who had walked all the way from Tennessee to Louisiana to try and find relatives that had been sold over 20 years prior to the war. Such a sight “reduced me to weeping,” the officer admitted. Often, it was necessary to use force to reunite families. Union Army units, mostly the Home Farm regiments, or even Unionist guerrillas helped to emancipate family members who were still living under slavery. One such event took place in Lynchburg, Virginia, where a detachment of Federal cavalry arrived at the farm of B.E. Harrison, the former owner of one of the troopers. Though this cavalryman had escaped to and joined the Union Army, he had had to leave his wife and child behind. But now the father had returned, “with a cavalry saber in his hand,” to demand the return of his family, pledging to torch the place when Harrison said that he had already “refugeed” both of them.

Once their families had obtained legal recognition, most Black people then turned to education as another great priority. Already by the fall of 1861, the American Missionary Association (AMA), had sent missionaries into the contraband camps to educate the former slaves, and soon it was joined by several more such organizations. In 1863, the newly minted Freedman’s Bureau took over the education of the freedmen, but it maintained its collaboration with these Northern missionaries, with the explicit objective of socially transforming the South. Freedmen almost immediately embraced education as a way to better themselves and their communities. “They are anxious to have their children well educated,” noted a Yankee. A Louisiana freedman demonstrated when he declared that “Leaving learning to your children was better than leaving them a fortune; because if you left them even five hundred dollars, some man having more education . . . would come along and cheat them out of it all.” Black people, it was evident, realized that being educated was key to their future success, and as a result threw themselves wholeheartedly into founding schools with the help of the Freedman’s Bureau and recruiting teachers from the ranks of the Northern missionaries.

By late 1864, Bureau schools dotted the South, the seeds of a larger process that built the first public education system in the region after the war. During it, most schools were instead temporary ones set up in Union-occupied cities and in redistributed plantations. But these still provided the opportunity for learning, and the enthusiasm of the freedmen quickly surpassed even the most optimistic predictions. Black children “can learn to read and write as readily as white children,” reported Union officers. They “are smart, bright and quick to learn, and one can scarcely observe any difference in the rate of progress.” Black adults were just as eager to learn as their children, Lucy Chase stated, saying she had never seen “such greedy people for study . . . they are all very anxious to learn and full of ambition.” Black laborers would attend schools after their workdays were done, often learning alongside their children, and a salient point in most labor disputes mediated by the Labor Bureau was demands for the establishment of schools and allowance of time for learning. In a report a Union General included a comment by a Black child summarizing this progress: “Massa, tell ‘em we is rising!”

Black soldiers were also noted for trying to achieve literacy, establishing regimental schools, and seizing all available opportunities for education. "So ardent were they," a colonel exclaimed, "that they formed squads and hired teachers, paying them out of their paltry means.” “The colored troops carried [lesson] books with them when the army marched,” said a chaplain, their “cartridge box and spelling book attached to the same belt.” Altogether, as the commander of a USCT Mississippi regiment said with evident pride, the progress of the freedmen in “acquiring the rudiments of a common education,” was “under the circumstances truly wonderful.” But Black soldiers were not merely learning to read and write – they were also receiving an education on political issues and took their place in the work of building a Black consciousness and carving a place within the Nation. The effect of a few months of “soldiering” left a White missionary “astonished,” for the “cringing, dumpish, slow . . . are now here . . . wide awake and active.” Thomas Wentworth Higginson similarly observed how “the general aim and probable consequences of this war are better understood in [a USCT] regiment than in any white regiment.”

This political education and mobilization wouldn’t have been possible without the aid of the organizations that became the pillars of the Reconstruction-era Black community: the Union League, the Church, and Charitable Associations. Although all of these would fully flourish only after the end of the war, while it raged the seeds were already being sown. Several Home Farms and Federally occupied cities organized different associations bearing names like “Loyal League,” “Equal Rights Association,” or “Club of the Colored Union People,” that have all been gathered under the umbrella of the Union League. Organized with the approval or even the assistance of Federal commanders and Bureau agents, the Union Leagues were meant to educate the freedmen in the responsibilities of a citizen, facilitate the establishment of the Republican Party in the Reconstructed South, and mobilize the support of Loyalists to grant both legitimacy and stability to the new order. The first wave of Union League activity then came in the Border States, Louisiana, and Tennessee, the areas where the revolution had achieved the deepest inroads, as the limited number of Black voters marshaled to bring support to Lincoln, not only through their own ballots but also by actively fighting the opposition tickets.

Bureau schools in the South

The Union League, however, was merely one vehicle of Black organization, for emancipation also allowed Black communities to take charge of their community affairs, chiefly, religious practice. Under slavery, Black people had worshipped in Churches under White control, often being indoctrinated to believe slavery was ordained by God. The enslavers were never truly successful, for Black people still gathered in secret to hold their own religious meetings, incorporating West African spiritualism and a millennialist outlook that predicted future liberation. The coming of the war was then seen by Black people as a “fulfillment of the prophecies.” Emancipation allowed Black people to build and consolidate their own Churches, which besides places of worship also became places of learning and community organization. Black ministers especially took on an important role as leaders, not only spiritual, but political and social, settling disputes, representing their communities before the Federal authorities, and later organizing the Republican Party and Union Leagues and even running for office. This was a politicization of Black religion that would continue and intensify during Reconstruction.

It was not only men that participated in the building of Black communities and consciousness, for women also readily took to politics and social organization – even over the objections of Black men. Under slavery, Black men had been deprived of the role expected of males in the midcentury United States as heads of households, breadwinners, protectors, and disciplinarians. The advent of Union rule not only brought freedom, but also “northern gender norms” for the Union granted Black men a patriarchal role, designating them as “heads of households” for the redistribution of lands, the signing of labor contracts, and Federal service. The fact that the freedom of Black wives, mothers, and children depended on the service of their Black male relatives further contributed to subordinating Black women to Black men. Yet, women refused to retreat to a purely domestic sphere. With the men off to fight or organized in Army units or paramilitary groups, women took over the responsibility of managing Home Farms and redistributed plantations. But Black women were also present in Churches, Union Leagues, and Party conventions; and marched together with the men to demand land, improved working conditions, or make their voices heard before the Federal authorities.

The questions regarding the organization of land and labor were also far from settled. While the progress of land redistribution was nothing short of astounding, many lands remained under the control of Unionist planters who, nonetheless, still struggled to adapt to the new order. These men, General John P. Hawkins complained, “cared nothing how much flesh they worked off of the negro provided it was converted into good cotton.” General Eaton likewise denounced how their motives “involved patriotism or humanity only as secondary and incidental considerations,” making money being their primary objective “whether the Union cause – not to mention the Negro – suffered.” Tensions especially flared up in Louisiana, where relative early Federal occupation, strong conservative Unionism, and the desire of the Hahn-Banks regime to court planters resulted in many pro-planter measures contrasting sharply with developments elsewhere. Even in those areas where the freedmen were acquiring greater rights by the hands of sympathetic Federals and progressive Philadelphia policies, planters still resisted bitterly. “It is disheartening,” a Bureau agent observed, “to see those who call themselves Union men asking for whips and overseers.”

The new militancy of the Black population, however, meant they continued to resist these arrangements. A provost marshal reported how the freedmen would “not endure the same treatment, the same customs, and rules – the same language – that they have heretofore quietly submitted to.” Wherever they had to work under White authority, “the negroes band together, and lay down their own rules, as to when, and how long they will work etc. etc. and the Overseer loses all control over them.” Even freedmen who had received redistributed land often resisted the continuous interference of Federal authorities, defying their pretensions to make them cultivate cotton or limit the size of their parcels. The nascent structures of the Black community helped in this resistance, for Churches and Union Leagues doubled as cooperatives for the acquisition and management of land or helped organize strikes or coordinate demands.

Towards the end of the war the increased organization and militancy of the Black community allowed them to affect State and even National politics. This was clearest in Louisiana, where Lincoln’s experiment of Reconstruction found itself assailed by Black citizens and Radicals that found it lacking. Lincoln had issued by Proclamations new guidelines and signed bills expanding the powers of the Bureaus to conciliate the Radicals, but he was still unwilling to change the fundamentally conservative Louisiana regime. Some “acquiescence” to planter interests would make “the deeply afflicted people in those States . . . more ready” to rejoin the Union, Lincoln hoped. But, as the New Orleans Tribune questioned, “given the hostility of these people to republican liberty . . . what is to become of the poor colored man if the Federal government removes its hand?” Lincoln still upheld his government, saying that if “the new government of Louisiana is only to what it should be as the egg is to the fowl, we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it.” Moreover, not admitting Louisiana would also mean rejecting “one vote in favor of the proposed amendment to the national constitution.”

Freedmen's meeting in Louisiana

A similar ambivalence was evident in the question of universal Black suffrage. While Lincoln maintained that those of “good conduct, meritorious services or exemplary character” should be allowed to vote, he expressed qualms about the idea of extending the franchise to all Black men without distinction. The government, assistant secretary of war Charles A. Dana said frankly, had no intention to create “a great negro democracy” in the rebel states. Acknowledging the presence of a few “worthy colored men,” Dana nonetheless believed that most Black people were “docile and easily led,” making it necessary to adopt “certain qualifications.” But qualified suffrage would leave the few Black voters hopelessly outnumbered by White voters that, even if loyal, would be unlikely to be friendly to Black aspirations. This could be observed, again, in Louisiana, where the reconstructed state government under Banks and Hanh had showed little regard or interest in Black aspirations. This was a bitter pill for the gens de couleur that had at first expected to assume a new leading position. They had neither been granted offices, nor influence. They could not “understand why former rebels are treated with friendliness” while they “are ignored, debased and humiliated,” in the words of one of them.

Notwithstanding this hesitation on the part of the Union leaders, Black people continued to organize politically to push for changes. On the 4th of July 1864, a massive convention of Black men met in New Orleans to celebrate the second anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and demand the extension of the vote to all Black citizens. Though dominated by the creole elite, to the point that “every question might be put to the house in English and French,” the convention was a truly radical one that embodied the “new political experiences and sensibilities” created by the revolution. The former slave and current Union Army captain James Ingraham, “the Mirabeau of the men of color in Louisiana,” stalwartly insisted that Black men “take a bold and general position” to “ask our rights as men.” Although “elected and sustained by Black votes,” the Legislature “has treated with contempt every bill which was in favor of us,” Ingraham declared. In consequence, they should demand universal suffrage from the national Congress, a resolution that carried an overwhelming majority.

A couple months later, in October 1864, the “most truly national black convention” opened in Syracuse, New York. Nine years after the last National Convention of Colored Men, which had closed amidst fighting and despair, this new convention extended a “hand of fellowship to the freedmen of the South” and demanded they be given their “fair share” of lands; praised the “unquestioned patriotism and loyalty of colored men” but demanded that they be accordingly granted the “full measure of citizenship;” and pushed for universal Black suffrage as merely their ”just claims.” The organization and militancy of the Convention so impressed Lincoln that he received a Black delegation in Philadelphia. Leading the delegation, Frederick Douglass denounced how the Republican Party remained “under the influence of the prevailing contempt for the character and rights of the colored man,” and asked Lincoln to both protect the few Black men who could already vote and seek to enfranchise more. Douglass was pleased by how Lincoln “showed a deeper moral conviction against slavery than I had ever seen before in anything spoken or written by him,” yet he resolved that pressure ought to continue until he fully embraced complete equality in all regards.

Nonetheless, a shift in the opinions of the Administration and the Northern States was already evident. Several Northern States eliminated at last their discriminatory laws, extended public education to Black children, and submitted referendums on the question of Black suffrage to the voters. Despite bitter complains by the planters, Lincoln refused to go back on land redistribution or the new prerogatives of the Bureaus, writing that “I wish the material prosperity of the already free which I feel sure the extinction of slavery in all its forms would bring.” At the same time the Administration adopted new measures to show its support for liberty and equality, sending a Black consul to Haiti; appointing Martin Delany a colonel and putting him in charge of the Bureaus in South Carolina; and releasing guidelines to assure “equal and respectful” treatment to “the colored citizens” by the Armed Forces and Bureaus. Teachers, for example, were prohibited from using “the vulgar and hurtful word nigger.”

But this progress resulted in an inevitable conservative reaction. The tide of the Revolution, hopeful and astounding as it was, could be reversed if Lincoln was defeated and a Conservative government took office. Black people could be despoiler of their farms and rights; plantation discipline could be reasserted; and the advance in aptitudes towards race and equality could be arrested. While the victories had been a hard coup against the Opposition, it was still entirely possible that the Northern people might decide that someone else other than Lincoln would be better at bringing the war to a conclusion or building a peace. The Administration and its allies could not rest on their laurels, especially if they expected the election to result in approval of its most radical departures in policy. Consequently, as the advocates of White supremacy and Restoration gathered to fight Lincoln, the supporters of Liberty, Equality, and a complete Reconstruction mustered to reelect Lincoln.

"The First Vote," depicting the prosperous farmer, educated mulatto, and brave soldier as examples of worthy voters of color

At the head of one of the opposition columns was Andrew Johnson. At first glance, Johnson had lived a life remarkably like that of Lincoln, being born in poverty in a Slave State and achieving prosperity and political success only later. Johnson, in fact, never attended even a frontier school, being taught to read as an adult by his wife. Known as the “Tennessee Tailor,” Johnson showed his talents in the rough world of the Tennessee stump, being elected to several offices including Governor before ultimately reaching the United States Senate. There he achieved initial distinction by being the only Southern Senator to remain loyal to the Union. At first, Johnson even gained a reputation for radicalism, emancipating his own slaves and working for emancipation in Tennessee, and denouncing the slavocrats. But Johnson’s inherent conservatism, inability to compromise, and inflexibility made Lincoln pass him over for the position of Tennessee’s Military Governor, a slight that Johnson never forgot and which he attributed to a vast conspiracy out to get him personally. Selected as the candidate of the National Union due to his unimpeachable loyalty, Johnson would soon grow bitterly reactionary and stubbornly uncompromising.

The head of the other opposition column was Samuel J. Tilden. A New Yorker who grew up in a world of influential politicians and merchants, Tilden obtained great wealth by shrewdly defending railroad and business interests. Initially a “Barnburner” that opposed the expansion of slavery, Tilden was disquieted by the Republican Party’s radicalism and strongly opposed Lincoln. Initially, Tilden had hoped to strike a moderate tone of reform, uniting Conservative Republicans and Moderate Chesnuts, but all his schemes had come to naught. Now forced to wage the campaign on his own, Tilden’s former political acumen suddenly disappeared. He now proved “hesitant, timid, and for the most part ineffective,” merging into the background instead of taking charge. Even his confidant John Bigelow had to sullenly admit that “Tilden took an inordinate amount of time to do things, complained childishly, and engaged in petty faultfinding,” making Bigelow “begin to have some misgivings whether he will prove equal to the labors of the Presidency.”

The last Chesnut faction could not even be truly considered a column, its numbers and strength so depleted by the latest events that it could serve as little more than a spoiler. These Copperheads gathered now under George H. Pendleton, a man with close Southern ties and sympathy for slavery. In fact, after the 13th amendment passed, Pendleton assured himself that “when the historian shall go back to discover where the original infraction of the Constitution was, he may find the sin lies at the door of others than the people now in arms,” all but stating that the Confederate rebellion was justified. Though one of the most prominent Copperheads, Pendleton now he found himself “without a platform to stand on,” for virtually no one believed that a negotiated peace could be concluded with the Confederate Junta. Instead, Pendleton swung to new issues of economic populism focused on the Midwestern States, where he promised to pay bonds in greenbacks and end the “system of financial robbery and rapine” that subordinated them to Eastern interests. This seeming disinterest in the current issues led a confused voter to ask: “does Pendleton know there is a war going on?” But they offered a glimpse into the future.

Pendleton’s mere presence resulted uncomfortable for both Tilden and Johnson, who spent a lot of energy and time distancing themselves from him and even denouncing him, time that could have been better spent attacking Lincoln. Johnson especially sought to portray himself as the War Candidate, asserting that he and his men “gloried in the victories of the Union while at the same time rejecting the Lincoln administration’s stewardship of the war effort.” The Johnson campaign maintained that winning the war had taken so long due to Lincoln’s “ignorance, incompetency, and corruption.” Lincoln and his Radicals were the “disunionists of the North” who had provoked the war in the first place, all his policies “calculated to extinguish every spark of Union sentiment in the Southern states.” Johnson, they said, represented on the other hand victory “without the disgrace of Negro aggrandizement.” Those “who believe that this is a white man’s government – that white men shall rule it, and that a white man, no matter how poor or low his condition . . . is as good as any negro in the land, will vote for Johnson and Franklin on the white man’s ticket.”

To bring this message to the masses Johnson in October went in a series of speeches throughout the Western and Border States, which has been called the Swing Around the Circle. Johnson denounced that land redistribution and Black suffrage could only result in “a tyranny such as this continent has never yet witnessed,” and a “relapse into barbarism.” Though he again called for “treason to be made odious and traitors punished,” in an angry harangue Johnson exclaimed that surely Thad Stevens and Wendell Philipps deserved to be hanged too, for they were just as “opposed to the fundamental principles of this government.” Responding to hecklers who called him a traitor Johnson with sour self-pity said that “I have been traduced, I have been slandered, I have been maligned. I have been called Judas Iscariot . . . Who has been my Christ that I have played the Judas with? Was it Abe Lincoln?" Asked about Reconstruction, Johnson snapped that Restoration would happen automatically without need for Congress, which had no power to impose anything on the Southern States anyway; intimated that proposing an amendment with States unrepresented was unconstitutional and revolutionary; and insinuated that if the Opposition gained enough seats, he’d recognize a “Counter-Congress” including Southern claimants.

George Hunt Pendleton