The extent of the Peninsula disaster cannot be understated. At the start of November, it had seemed like the Army of the Susquehanna was about to capture Richmond and end the rebellion. Two months later, and the Union had suffered a terrible and disgraceful defeat, its shattered army ingloriously fleeing Lee’s pursuing rebels. As consternation gave way to cheerful celebration in the South, the North and the Lincoln administration, fresh from a victory in the 1862 midterms, suddenly saw its fortunes reserved and fell into the depths of despair and melancholy. The President, more than anybody else, recognized just how tremendous this defeat had been, shown from his exclamation when he received a telegraph informing him that half of the Army had been destroyed: “My God! My God! What will the country say!”

As McPherson succinctly puts it, the country “said plenty, all of it bad.” “This year shall always be known as the DARKEST YEAR of American history,” despaired George Templeton Strong. "We are utterly and disgracefully routed, beaten, whipped.” "On every brow sits sullen, scorching, black despair,” wrote Horace Greeley to Lincoln, while Charles Sumner, upon receiving the news, is said to have cried “Lost, lost, all is lost!” Quartermaster General Meigs lamented that “Confidence and hope are dying…. I see greater peril to our nationality in the present condition of affairs than I have seen at any time during the struggle.” The President, his personal friend Noah Brooks said, appeared “so broken, so dispirited, and so ghostlike” by the state of affairs. Was the Union cause lost?

Joyous Confederates believed so, as they celebrated their glorious Cannae. Thomas R. R. Cobb said that Lee’s campaign “has secured our independence,” and the veteran Fire-eater Edmund Ruffin agreed, declaring that “this hard-fought battle is virtually the close of the war”. Newspapers urged Lee to follow-up his victory by "a dash upon Philadelphia, & the laying it in ashes . . . as full settlement & acquittance for the past northern outrages”. The

Richmond Whig declared that "The breakdown of the Yankee race, their unfitness for empire, forces dominion on the South. We are compelled to take the sceptre of power. We must adapt ourselves to our new destiny.” "The fatal blow has been dealt this 'grand army' of the North," wrote a Richmond diarist, “I shall not be surprised if we have a long career of successes.”

General Lee, naturally, received the effusive gratitude of his country. Lee, a Richmond newspaper said, had "amazed and confounded his detractors by the brilliancy of his genius . . . his energy and daring. He has established his reputation forever, and has entitled himself to the lasting gratitude of his country.” Secretary of War Davis congratulated Lee for his victory over a foe “vastly superior to you in numbers and in the material of war” and expressed confidence that he would go on to “drive the invader from our soil, and carry our standards beyond the outer bounds of the Confederacy.” Even Breckenridge let himself be carried away by the excitement, and the usually gloomy statesman soon issued a grandiose proclamation: “Soldiers, press onward! . . . Let the armies of our Confederacy continue with their monumental discipline, bravery, and activity, and our brethren of our sister States [Maryland and Kentucky] will soon be released from tyranny, and our independence be established on a sure and abiding basis.”

Just like Lee was the hero of the hour in the South, in the North General McClellan was demonized as the architect of the worst military disaster in American history. Northern Governors reported riots where he was hung and even burned in effigy, and several regiments quickly wrote proclamations accusing him of cowardice, and even treason for “leaving behind our brave comrades” to be captured “by traitors and slavers.” The fact that some contrabands had been left behind as well caused great moral outrage in the North among abolitionists, and even some people usually not concerned with the welfare of Negroes could not help by feel pity for the slaves and fury at the casual cruelty committed against them – after all, everybody well knew what their fate would be now that they were “trapped by the hateful clutches of bondage” again.

Even McClellan, for all his ego and vainglory, seemed taken aback by the extent of the disaster. He had not failed to win as in previous occasions, this time he had been

defeated, and knowing this was painful. “Several regrettable mistakes were committed during the campaign”, he confided to his wife, “and I must admit that anxiety and want of sleep caused me to not perform as I should have.” Even McClellan’s soldiers, who had been hitherto so loyal to their commander, turned on him. A visit to the army camps punctuated this, for instead of cheering and throwing their hats high on the air, the soldiers threw rocks and hissed at McClellan. “The terrible knowledge that he would abandon us if he judged it necessary to save himself”, a private wrote home, “has made the Army realize that we have not got a man on horseback but a

treasonous idiot in charge.”

For all that McClellan complained of political intrigue, in this case it was the self-serving politicians who came to the rescue. Or at least tried to. Seizing news from Jackson’s Valley Campaign, including some reports from the reckless and bitter Frémont, some National Unionists asserted that the failure in the Peninsula had been Lincoln’s fault, not McClellan. By diverting troops from the Peninsula to the Valley, they argued, Lincoln had “disastrously and irremediably” deprived McClellan of strength he needed right then. Some historians have also declared that this decision was a blunder, but Lincoln certainly can’t be blamed for McClellan’s numerous mistakes. In this case, it seems that the Chesnuts were simply grasping at straws, trying to find a way, any way, of protecting their champion and blaming the Lincoln administration for the failure. One even frankly admitted that McClellan’s conduct “could not and ought not to be defended or tolerated” and that in trying to defend him they were only “harming the national cause” in the name of rabid partisanship.

Thus, concluded several historians, National Unionist attempts at defending McClellan were not so much for the benefit of the General but a vain attempt to lay the blame on Lincoln, motivated by the “shocking and traumatizing” results of the 1862 midterms. Whether the midterms were in actuality an endorsement by the American people of Emancipation and the Lincoln administration is still contended, but it still was widely interpreted as such at the time. It’s clear that, had Lee expulsed McClellan from the Peninsula a few weeks earlier, the results would have been very different. The few War Unionists who were willing to defend McClellan clearly realized that this was a wildly unpopular move, and had to contend instead with incessant attacks and recriminations from the Copperhead half of the party, who loudly proclaimed that the Peninsula disaster demonstrated, once and for all, that it was impossible to subdue the South by force of arms and to try would only bring bloodshed and suffering.

The Peninsula Disaster destroyed McClellan's reputation. Though he continued to claim, till the end of his life, that Lee had outnumbered him and that the defeat was Lincoln's fault, he was cashiered from the Army and later convicted by a Court Martial of insubordination and cowardice.

The fact that the Republicans had won big, and a few weeks later, McClellan, a National Unionist who had indiscreetly expressed his hate for emancipation and radicalism, had been soundly defeated inspired dark rumors in Philadelphia. Had McClellan not thrown away chances to defeat the rebels decisively at Annapolis and Anacostia? Why hadn’t he attacked Lee when he was distracted and vulnerable? Why had he abandoned Sumner and Potter? Stanton, already an irascible man, was completely furious at the news, especially due to McClellan’s provocative and insubordinate last telegram that attempted to lay the blame on the administration. Congressional Republicans shared his ire, with Senator Wade going as far as asking permission to “guillotine the traitor General”, one hopes in a figurative sense. President Lincoln, however, felt that he had to deal with McClellan personally.

Normally a calm man, Lincoln was incensed by the cowardice McClellan had shown, and even more so by McClellan’s self-serving attempts to defend himself. In response to a wildly inaccurate report released by McClellan claiming that he was greatly outnumbered and the Administration had set him up for failure, Lincoln released documents contesting Lee’s numbers. The documents also proved that McClellan’s only substantial success, the Battle of Anacostia, had been thanks to Lincoln, for McClellan originally had intended to employ a strategy similarly to the one that had brought unmitigated disaster on the Peninsula. Lincoln, it was clear, had no more time for McClellan’s insubordination or his lack of commitment to the Union cause. Two weeks after he had returned from Virginia, McClellan was dishonorably discharged from the Army and the Committee on the Conduct of War was given permission to investigate whether formal charges were to be levied against him.

Able politician he was, Lincoln could recognize how delicate the situation was. Most of the opposition had decided that defending McClellan was not beneficial to their cause, but even if they had forsaken the former General they were still bitterly opposed to Lincoln and the Republicans. Chesnuts were thus able to find an ingenious third way that allowed them to blame both Lincoln

and McClellan for the defeat, usually by saying that the whole disaster had been Lincoln’s fault for appointing and keeping such an incapable commander in the first place. It was a very cynical move, especially taking into account that these same Chesnuts were proclaiming their loyalty to Little Mac and defending him against Radical critics just a few weeks earlier. Moreover, they claimed that in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln had caused such a serious moral crisis that it was no wonder that the Dixie boys had whipped them.

The siren song of the Copperheads was especially powerful when it came to enticing men who had been willing to accept emancipation if it meant military victory. Now they believed Chesnut propaganda that the contrary was true, and that emancipation actually resulted in military disaster. Calls for the Proclamation to be repealed and the war returned to “its true and wise constitutional principles” abounded, but Lincoln held firm, claiming that the Emancipation Proclamation constituted a promise that must be kept and that to repeal it would go against the honor of the nation. Copperheads then turned to saying that the Peninsula defeat was brought by emancipation, and that further disaster would be brought by it again in the future, and consequently the war could only be ended by negotiation instead of the “bloody and despotic” prosecution of an emancipation war.

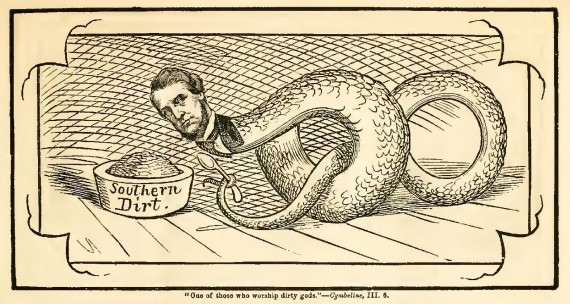

The Copperheads were widely reviled as supporters of the rebellion and disunion

Veritable legions of people joined the Copperheads in the immediate aftermath of the Peninsula Campaign, mostly fueled by bitterness against an Administration “that has fed vile lies to the people” in an effort “to continue a war for the benefit of niggers”. The War Unionists, who had rallied against the Copperheads as unpatriotic, now were completely discredited. Many considered them to be misguided fools at best and “tools of the Black Republicans and their objectives of massacre and rapine” at worst. The National Union consequently became a completely Copperhead party, that worked not only to undermine Lincoln’s ideological objectives but the very prosecution of the war, doing all they could to subvert the authority of the government and lower the moral of the people.

Even some Republicans were more willing to assign the blame to Lincoln, like a New York man who wrote that “Things look disastrous. . . . I find it hard to maintain my lively faith in the triumph of the nation and the law.” The more conservative Republicans, already fatally alienated due to the Emancipation Proclamation, now completely deserted the Republican Party, an event marked by the Blair family’s proposal to “dispense with the support of the Radicals and the slave question” and create “a party consecrated to Constitutional peace and reunion”. As usual, strong racism characterized this opposition, for they proclaimed that continuing the war would place the South under the rule of “a semibarbarous race of blacks who are worshippers of fetishes and poligamists,” and wanted to “subject the white women to their unbridled lust.”

This incendiary rhetoric resulted in major outbreaks of violence throughout the North, as mobs took to the streets to attack symbols of government authority and lynch Negroes. For example, and despite the great need for manpower, Southern Illinois yeomen violently drove away contrabands the War Department had brought to help along with the harvest. Angry multitudes even demanded for new elections, claiming that the 1862 midterms were invalid because the “whole pernicious results” of the Proclamation hadn’t been clear yet when the balloting took place. Lincoln, Seward, Stanton, and other Republicans were burned in effigies as mobs howled for the blood “of every single damn radical and the niggers they so love.” “The ascendancy is with the Blairs,” wrote Charles Sumner sadly.

Just like how Lee’s victory was deeply ironical in how it assured the future destruction of the South, this bitter and violent opposition ironically contributed to the further radicalization of the Republican Party, Lincoln and the Union cause as a whole. Undoubtedly, some Republicans followed the Blairs and became Copperheads, but the great majority of Republicans, both politicians and voters, remained loyal to the Lincoln administration and faulted McClellan and the National Unionists completely for the disaster. The Republican victory in 1862, detailed analysis has shown, was not due to National Unionists voting for them. Instead, Republican turnout remained as high as 1860 while it greatly fell in Chesnut areas. These rioters, consequently, were not alienated Republicans but Chesnut who had never and would never support the administration anyway – there was no reason to try and mollify them.

Copperhead propaganda made effective use of racism in order to arose the opponents of the Lincoln government

Lincoln, of course, could not know this due to a lack of precise statistical models, but he and the great majority of Republicans considered the election results a vote of confidence and were right in believing that the people who opposed them did not represent a majority but a loud and violent minority. Their turnabout regarding McClellan and their insistence that the Peninsula had been the fault of both McClellan and Lincoln did much to turn ambivalent citizens against them. Some War Unionists even joined the Republicans, horrified by the pro-peace message of the Copperheads, and anti-Negro violence converted a few lukewarm supporters into full-fledged abolitionists. “The depths of depravity shown by these men,” a Maryland Unionist said, “have only convinced me that the government must be more decisive in its protection of the rights of all citizens, without regard to color.”

“The great mass of the people,” Secretary Seward assured the President, “stand loyally with the Union against traitors

both North and South.” Indeed, the Copperheads were widely seen as disloyal elements that sided with the Confederacy and slavery against the government. If the opposition was only a disloyal minority and true Union men supported the administration and emancipation, then Lincoln was free to continue moving to the left in varied issues such as Black civil rights and the future of Reconstruction. Since, as McPherson explains, “in Republican eyes, opposition to Republican war aims became opposition to the war itself” and opposing the war was treason, the Republicans were free to dismiss their adversaries and press on with a war for Union and Liberty. Lincoln still occupied the moderate center of the party, but the Republicans as a whole had moved radically to the left since the start of the war, and violent Copperhead opposition did nothing to arrest this movement and instead stiffened their resolve to see the war through. Thus boldly declared Lincoln his intention to “maintain this contest until successful, or till I die, or am conquered . . . or Congress or the country forsakes me.”

While the Copperheads actively worked on making the country forsake Lincoln, Breckenridge and Lee were preparing to conquer the Union armies once again. Ever aggressive, Lee was already making plans to follow up on his victory by attacking the Federals at Manassas. From there, he could then invade Maryland and reestablish the Confederate government. Lee also had plans to destroy the remains of “those people”, that is, the two corps that remained of the Army of the Susquehanna plus the troops under Hooker. Secretary of War Davis was delighted by this, claiming that the Confederacy had not invaded the North simply due to a lack of arms but that now Lee “is fully alive to the advantage of the present opportunity, and will, I am sure, cordially sustain and boldly execute the President’s wishes to the full extent of his power.”

At first, it wasn’t clear whether such an offensive indeed reflected the wishes of the President, but Lee’s splendid victory had done much to convert Breckenridge from a defensive doctrine to the gospel of the offensive-defensive, and he was now ready to “seize the hour and strike for our liberty . . . I’ve never felt more like fighting.” With the army of the Susquehanna so utterly beaten and demoralized that it would take weeks, perhaps months to reconstruct it, there was a golden chance to assault Hooker’s force. The elan of this command was also affected after seeing the Peninsula disaster and being bested by Stonewall Jackson, so Lee expected a rather easy victory. He quickly prepared to go forward in an all-out attack before the remnants of the Army of the Susquehanna could come and bolster Hooker’s army.

Lincoln was painfully aware of this critical weakness. Fortunately, the logistical and material superiority of the Union remained intact, allowing for the troops to be quickly taken to Washington and for new armies to be organized. The fact that the Nine Days had taken place towards the end of December also helped, for the winter of 1862-1863 was cold and wet. Whereas that kind of weather had helped Lee by washing away McClellan’s bridges, it now complicated communications, resupply and transportation. No matter, Lee and his hardened rebels, some of them without shoes and surviving on little more than hardtack and wild onions, were determined to attack. For yes, it was true that the Union kept the material superiority, but Lee now had a psychological edge that was not easy to overcome.

Military failure lent strength to the Copperheads

The Peninsula Campaign, for both Northerners and Southerners, had confirmed the old adage that a Southron could lick four Yankees, never mind past battles. It imbued the rebels with a strong espirit de corps that “did much to overcome the material superiority of the Union” and also caused “a gnawing, half-acknowledged sense of martial inferiority among northern officers in the Virginia theater”. It cannot be denied that the Peninsula Campaign was a disaster in material terms, but the greatest damage it did was to the Northern psyche – for many months afterward, and with the exception of a single half-victory, the Union was unable to take the initiative in the East, its soldiers and officers fearing another such defeat.

Lincoln had this demoralization in mind when he decided to renew the call for volunteers after the Nine Days. He feared, however, that "a general panic and stampede would follow” if he wasn’t careful. Seward engineered a clever scheme whereby the North’s governors would ask Lincoln to call new volunteers to “reinforce the Federals arms” and “speedily crush the rebellion”. The Secretary then proceeded to backdate the document to avoid the impression of it being a panicked response, but it’s doubtful whether anyone truly fell for this ruse. In any case, it allowed the administration to save some face, and in January 18th, 1863, Lincoln called for 300,000 men to “bring this unnecessary and injurious civil war to a speedy and satisfactory conclusion.” Among the men mustered into service in this time of crisis there were several black regiments.

Amid calls for volunteers to fight for “the old flag, for our country, Union, and Liberty” and stirring war songs like “We are coming Father Abraham! Three hundred thousand more!”, the Northern war machine geared up for another fight. Reform within the army was evidently needed. In January 28th, Lincoln dismissed Halleck, believing him ineffective and weak, and brough General Lyon from the West to be the new commander in-chief. Having proven himself an able man, aggressive yet practical, capable of both spurning subordinates into action or giving them necessary liberty, Lyon was definitely a step-up from Halleck, who had been little more than a glorified clerk. Grant, a man Lyon respected and admired, then became the highest-ranking Union commander in the West. Some “malcontents” were also exiled to distant posts, such as General Franklin, who disclaimed any loyalty for McClellan but had formed part of his clique previously.

The choice of who was to command the Army of the Susquehanna was more difficult. Burnside was considered, but the General was in charge of New Orleans, and though his rather heavy-hand was causing some tensions within the city, it would not do to remove him so soon. Besides, Burnside was considered a protégé of McClellan, even though their friendship had significantly cooled, and he even diffidently declared that he was not the right choice for the Army of the Susquehanna. Pope hadn’t been tested in battle, and was furthermore rather inept, earning the ire of his Eastern troops with a condescending proclamation: "I come to you out of the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies . . . I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you . . . certain phrases [like] . . . 'lines of retreat,' and 'bases of supplies.' . . . Let us look before us and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.” No wonder, then, that Pope failed to endear himself to the Eastern commanders, who almost unanimously opposed his appointment.

That left Fighting Joe Hooker as the only real candidate. It wasn’t an easy choice, and Lincoln only took it reluctantly. A tall and muscular man with clear blue eyes, Hooker was extremely confident, but also extremely arrogant and prone to reckless criticism against his superiors, having denounced both McDowell and McClellan non-stop in the hopes of obtaining the command for himself. Despite having the appearance of a soldier, Hooker was a hard-drinker with headquarters that seemed “a combination of barroom and brothel,” to the point that some have incorrectly claimed that “hooker” became a synonym of “prostitute” thanks to him. Hooker had even irresponsibly told a reporter that “Nothing would go right until we had a dictator, and the sooner the better”. But he was still a senior commander who had had performed admirably in previous engagements. Lincoln decided to take a chance on him.

Fighting Joe Hooker obtained his sobriquet by his hard fighting at Anacostia, where he was practically abandoned by McClellan.

Despite his moral defects, Hooker proved to be an inspirational and able commander, doing the best he could to instill moral and discipline back into a beaten command. Corrupt quartermasters were cashiered on the spot, while a much-needed emphasis on hygiene and alimentation improved the health of an army that had floundered under disease in the Peninsula. The disastrous desertions that for a while threatened to melt the army away declined, and administrative reforms such as making the cavalry a separate corps or creating insignias for each unit in order to instill pride helped along to revitalize the Army of the Susquehanna. Even an officer who heartily disliked Hooker had to admit that "I have never known men to change from a condition of the lowest depression to that of a healthy fighting state in so short a time."

This officer was overstating his point, for the month and a half that has lapsed since the Nine Days hadn’t been enough to completely restore the Army of the Susquehanna to its former glory. Morale remained low, and Hooker’s arrogant declaration that “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none” did not inspire any confidence on him achieving any actual victory. Lincoln himself was rather perturbed by this bravado, telling a friend that “That is the most depressing thing about Hooker. It seems to me that he is overconfident.” Nonetheless, he sent Hooker a fatherly letter. “There are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you,” Lincoln admitted, pointing out his bad relationship with his previous commanders. The President also signaled how Hooker had said that the country needed a dictator, stating that “it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.”

Lincoln then discussed the morale of the Army, warning that “the spirit which has overcome the Army, of doubting their capacities and criticizing their Commander, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you, as far as I can, to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army, while such a spirit prevails in it.” Despite these difficulties, Lincoln still expressed his confidence on Hooker, ending his missive by advising him to “Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.” Whether Hooker was up to the task was to be tested in a trial by fire on February 22nd, when Virginia’s muddy roads finally dried up enough for Lee and his rebels to swept forward and face their enemies once again.

Unfortunately for Hooker, Lee’s Army had also used those two months on winter quarters to rest and regroup. Morale was high as most rebels now expected a second glorious victory. Their first success had improved dramatically the morale at home, which translated into a better situation at the Homefront with Breckenridge’s government and the Confederate grayback strengthened. A new system of food transportation had resulted in better and bigger rations, and most men had replaced their rags with decent uniforms. Most even had shoes. Breckenridge so trusted Lee that veteran regiments guarding Richmond were allowed to go with him, leaving only some green troops to protect the Confederate capital. The dramatic losses the Army of the Susquehanna had suffered in the Peninsula allowed the Army of Northern Virginia to more or less match its numbers, having 80,000 men to the 100,000 Hooker could bring into battle – The Army of the Susquehanna hadn’t been reinforced to its full strength yet.

This was partly the result of dwindling war enthusiasm among the Northern public. Understandably, after such a terrible disaster and many bloody battles, few still believed in war as a glorious endeavor. The North still had an enormous pool of manpower, having mobilized only a third of its full potential, but actually getting them into the army was a challenge. The War Department soon enough started to offer bounties in order to entice men to volunteer, a process that later degenerated into “a mercenary bidding contest for warm bodies to fill district quotas.” But by far the most important measure was a Conscription Act that allowed the government to graft men into the Army through a red of provost marshals. Stanton, true to form, enforced the act with ruthless efficiency in spite of a violent Copperhead response that ended with at least five enrollment officials dead and required troops to be sent to enforce the draft in several states.

In due time conscription was able to bring hundreds of thousands of soldiers into the Armies of the Republic, but for the moment the messy and disorganized process was unable to muster more than a handful of regiments. Hooker would have to do with the men he had at the moment. On February 22nd, his scouts reported that the rebel regiments at Manassas junction had started to advance. It was none other than the feared Stonewall Jackson, doubtlessly ready to spearhead Lee’s offensive. Vowing that he would come no closer than that, Hooker decided to attack first, hoping to surprise and overcome Lee near a small stream called Bull Run. "Our enemy must ingloriously fly," boasted Hooker, "or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him."

The cruelty of war meant many men were reluctant to join the Army. As McPherson says, "the 300,000 more came with painful slowness."

Hooker’s attack was marred by its complexity. Most of the Army was divided into two parts, a couple of titanic pincers that was ready to crush Lee between them. His cavalry also advanced, intending to avenge previous embarrassments by sweeping to Lee’s rear and cutting his supply lines. Yet as the actual decisive hour approached, Fighting Joe hesitated and lost his nerve. After the battle, an officer declared that in hindsight this should have been expected, for "Hooker could play the best game of poker I ever saw until it came to the point where he should go a thousand better, and then he would flunk.” Troubling signals were already apparent, as Hooker talked not of defeating Lee on the field of battle, but just distracting him before starting a mad dash for Richmond. A dismayed Lincoln quickly told him that “Lee’s Army, and not Richmond, is your true objective point”, but it’s clear that Hooker had been invaded by a secret fear that Lee would destroy him like he had destroyed McClellan. Afraid of defeat, he did not even try to win.

On February 23rd, Jeb Stuart’s able troopers intercepted their Yankee rivals who had been able to tore up some railroads but had achieved little otherwise. The Federal cavalry was still far outmatched by the rebels, who taunted them as “pasty faced” and weak city boys who still felt uncomfortable on the saddle. With grim determination, the Union soldiers resisted for a while until Stonewall Jackson himself appeared on the scene and broke them with a charge of his foot cavalry. Amid calls of how the rebels were so superior that they did not even need horses to best the Federal cavalry, the Union retreated. Hooker then inexplicably decided to not continue his attack, and instead pulled back to a defensive position behind the Bull Run. The rebel troops then grouped in Henry House Hill, planning a daring counterattack. Lee’s plans called for Jackson to go “on a long clockwise flanking march to cut Union rail communications” in Hooker’s rear. It was practically the same maneuver Hooker had attempted, but Lee trusted Stuart and Jackson to do it successfully.

As night fell over Manassas, the screaming rebels went forth and captured Hooker’s supply depot, eating everything they could before burning the railroad tracks that Herman Haupt had worked so hard to maintain. Taking no time to rest, Jackson then attacked the Union right, commanded by his old foe "Commissary" Banks. In his haste to avenge his humiliating defeat at the Valley, Banks attacked without waiting for his entire force to gather. The result was that Jackson outnumbered him and easily crushed Banks a second time, while the terrified Hooker did nothing despite having two corps virtually idle nearby. The next day, Hooker was finally shocked from his trance when Lee and the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia broke through a gap in the Bull Run Mountains that Hooker had not defended adequately, believing that he was going on the offensive. An all-western brigade, mostly formed out of Indiana and Wisconsin regiments, resisted the rebel onslaught admirably, earning the name of the “Iron Brigade”. A Maine regiment under the command of a Maine university professor named Joshua Chamberlain also achieved moderate success, holding the rebels back for a while.

No matter the bravery of individual regiments, it wasn’t enough if the overall commander didn’t have enough courage and decisiveness to lead the entire Army onto victory. Instead of bravely rallying his troops into a general counterattack, Hooker sent them in in chaotic, piecemeal attacks. Although his bluecoats “came on with fatalistic fury and almost broke Jackson's line several times”, it wasn’t enough, and at the end of the day the Union had nothing to show except “mountains of corpses and rivers of blood”. All the while, the other half of both armies just stood to the side doing nothing, because Longstreet preferred to be on the defensive and had convinced Lee to allow him to wait until Hooker attacked him. But Hooker, at the same time, was so afraid of attacking that he also waited on the defensive. The entire battle thus retroactively gained the reputation of a bloody fiasco, for neither commander really brought his full strength to bear.

The third day, February 25th, Hooker refused to counterattack, afraid that it would allow Lee to destroy him. His officers protested, with General Darius Couch declaring that “I retired from his presence with the belief that my commanding general was a whipped man.” Hooker was indeed whipped, only continuing his ineffective piecemeal resistance while Stonewall Jackson’s screaming rebels continued to fight with high spirits. As in other occasions, the bravery of the Union troops surpassed that of their commanders, for the Federals almost managed to threw Jackson back. At one moment, after “one of the war's few genuine bayonet charges”, Chamberlain’s troops even managed to overrun the Southern position and plant the star and stripes high in the air. But then Longstreet suddenly went on the offensive, and a stampede followed as many blue regiments fled to the rear in panic. Completely defeated by now, Hooker ordered a retreat on February 26th, ending the Battle of Bull Run.

For the second time in less than four months, Lee had achieved a titanic success against the Union Army, which once again ingloriously fled. It could be said that the defeat was “not so much of the Army of the Susquehanna as of Hooker”, who went from arrogant bragging to an ineffective and quite cowardly performance. Nonetheless, this defeat only reinforced the fears of many Yankees and the ego of many rebels, who started to see Lee as something of an invincible juggernaut. Even past triumphs such as Baltimore, Second Maryland and Anacostia were retroactively seen as flukes, only achieved because Lee wasn’t on the field. This defeatist spirit would continue for many months, causing further disasters for the Union. With Lee and his celebrating rebels pursuing Hooker and the Copperheads gaining strength, it seemed like the Lincoln Administration would go down in defeat and slavery and treason would triumph.