They honestly do when you think about it. Heck he even has Grant as his Scipio Africanus.His campaigns into the north do have a hannibal-esque feel to them, don't they?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"BWAHAHAHAHAJoe Johnston, reduced to an insignificant role as a military inspector, observed that the defenses were so weak that "No one but McClellan could have hesitated to attack.”

Good that the Peninsular Clusterfuck managed to be delayed until after the midterms. Still, it's clear that Lee's (EDIT: And Stonewall's) brilliance and Little Mac's incompetence are going to put the Union into a dark time in late '42. Best we can hope for is that Lee's subsequent invasion of the north will make people realize peace isn't an option.

Last edited:

So I know I replied already, but I suddenly had a comical idea.

There's a Hogan's Heroes episode where London gets its wires crossed between a Colonel Crittendon with a great plan for sabotage somewhere and the one they know who had this dreadful plan for planting flowers along runways to boost morale. Of course they break the latter out and take him along, only for Hogan to have to save the day.

And I was just thinking that President Lincoln must be thinking that somewhere, there's this brilliant McClellan who has a plan and skill that will win the war, and somehow things got confused and he's stuck with a McClellan whose brilliant plan consists of planting geraniums all around possible battlefield sites.

There's a Hogan's Heroes episode where London gets its wires crossed between a Colonel Crittendon with a great plan for sabotage somewhere and the one they know who had this dreadful plan for planting flowers along runways to boost morale. Of course they break the latter out and take him along, only for Hogan to have to save the day.

And I was just thinking that President Lincoln must be thinking that somewhere, there's this brilliant McClellan who has a plan and skill that will win the war, and somehow things got confused and he's stuck with a McClellan whose brilliant plan consists of planting geraniums all around possible battlefield sites.

Last edited:

One thing im kinda sad about is that the i don't see how the natives will come off better on this tl, from wiki most natives sided with the confederates as the least bad option, but a much more rough more means more hatred towards them and one thing americans (from that time period) can agree on is fuck the natives i can see both confederates and unionist agreeing to this. So instead of predominantly white people killing natives and taking their land it will be both white and black. Is there any way for them to better off?

McClellan is slow and ponderous. He would react obviously to attacks, so the best way is for Lee to anticipate this and use the initial attack as a feint while the real one waits to smash the reaction

I've got to say, the way you're building up the Peninsular battle is a fantastic example of how to grow tension. Even though we already know that the battle is going to be an unparalleled disaster for the North, and even though we already know that in the end the North is still going to win anyway, the repeated mentions of just how much of a cluster it's going to be has me twitching.

Eagerly awaiting more.

Eagerly awaiting more.

i bet the repubilcans will be glad recall elections aren't a thing.this is gonna suck for the north.

Lee is very similar to hannibal now that i think about it..expect hannibals cause is probably more morally defensible.

They honestly do when you think about it. Heck he even has Grant as his Scipio Africanus.

Lee is very similar to hannibal now that i think about it..expect hannibals cause is probably more morally defensible.

Lee is very similar to hannibal now that i think about it..expect hannibals cause is probably more morally defensible.

There are few times in history where "Get them before they get us" is actually justifiable, but I think I would hear Hannibal out in that one. Rome was a dangerous enemy to have. Nipping it in the bud would been a service for the

Does anyone know if there are any sources on Hannibal's perspective on the war in his later life?

I remember somewhere that he wrote a book or something, but I could just be making that up.

McClellan really is to military leadership what Buchanan was to public office.

Another spectacular update! I love the look at how a combination of factors leads to overwhelming pro-Lincoln election results!

Thank you!

Great job. McClellan perched and staying there while you went through all the election stuff gave me a feel just like the nation would feel. Anxious to get the battle over with, amazed how much goes on in the interim.

It's personally difficult to capture the fact that these events took place over several months. The wait must have been insufferable. I'm glad I managed to transmit it somewhat!

Great update. I might have missed it but did you say who was chosen as Speaker of the new House? I assume that Grow didn't loose his seat TTL but was he unseated or is he considered closely-enough aligned with the Radicals?

Also, what’s Frederick Douglass up to at this point TTL?

Well, I haven't talked about the Speaker of the House because he simply does not seem like a very important figure. At the very least, none of my sources even bother to name the speaker outside of legislative battles to elect them. So let's just assume that a more radical Grow was elected and maintained his seat as well.

Douglass is involved in much the same activism as in OTL, especially helping along with the recruitment of the Massachusetts 54th.

Just wanted to say, you're really good at putting a heart into the history.

If anyone's read anything I've written on this thread, they know I have very few soft spots for the Confederacy. But somehow, this scene of the humbled politician tending to wounded men sparked more sympathy than I feel like admitting.

It's a sweet moment, and I like it a lot.

Philosophical question: If a writer creates a coincidence does it still count as serendipity?

Jewels & Prison Cigarettes: Am I a Joke to You?

Also props on the economics section, I'm sure that was a mountain of research and I definitely understood a solid 85% of it.

I'm not too sympathetic to the Confederates myself, but I think it's important to portray them as humans. Even if their cause was tragically flawed, they still suffered a lot for it. It's simply such a shame that racism and white supremacy was so ingrained in them that they would undertake such sacrifices...

I guess that it does not count as serendipity if the writer is completely aware of the circumstances he's created. Since this was my plan from the start, I guess it's not serendipity. Think of the possibilities if the House is still so overwhelmingly Republican, especially in regards to possible amendments.

Full-disclosure: the main source for the economics part is McPherson's excellent synthesis of the topic within The Battle Cry of Freedom. Since the TL is not focused on the economic aspect, and because economics is not a subject I particularly enjoy or understand, I believed it was good enough.

So it looks like the Peninsula Campaign is going to end a lot worse then OTL with McClellan walking right into a trap. If this does end up being the Cannae Lee always wanted wonder how he'll react when the Union acts like Rome and doesn't give up.

He'll probably just believe that this victory was not crushing enough and try to inflict another.

Getting real tired of your shit McClellan

- Lincoln, probably.

Little Mac at his best, no doubt about it.

He must feel bitter that the only victory he actually accomplished is one for the Republicans in the elections.

I just wish someone would off Lee before he prolongs the war. Damned slaving bastard deserves it.

Good ol' Bobby Lee, who allowed his men to kidnap Northern blacks and inflicted punishments such as lashing his slaves and washing their backs with salt.

BWAHAHAHAHA

Good that the Peninsular Clusterfuck managed to be delayed until after the midterms. Still, it's clear that Lee's (EDIT: And Stonewall's) brilliance and Little Mac's incompetence are going to put the Union into a dark time in late '42. Best we can hope for is that Lee's subsequent invasion of the north will make people realize peace isn't an option.

Copperheads, unfortunately, are perfectly poised to reap the benefits of this failure..

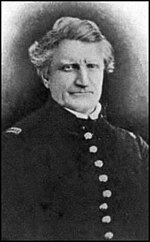

Really great update, just wanted to say that Francis Preston Blair looks like a goddamn nightmare and I resent that you made us look at him. Anyways keep up the great work, can't wait to see McClellan sent packing.

I guess being an evil old racist makes you disgusting on the outside as well. And thank you!

So I know I replied already, but I suddenly had a comical idea.

There's a Hogan's Heroes episode where London gets its wires crossed between a Colonel Crittendon with a great plan for sabotage somewhere and the one they know who had this dreadful plan for planting flowers along runways to boost morale. Of course they break the latter out and take him along, only for Hogan to have to save the day.

And I was just thinking that President Lincoln must be thinking that somewhere, there's this brilliant McClellan who has a plan and skill that will win the war, and somehow things got confused and he's stuck with a McClellan whose brilliant plan consists of planting geraniums all around possible battlefield sites.

Somewhere, a Lieutenant George MacClellan is watching helplessly as General George McClellan leads them to disaster...

One thing im kinda sad about is that the i don't see how the natives will come off better on this tl, from wiki most natives sided with the confederates as the least bad option, but a much more rough more means more hatred towards them and one thing americans (from that time period) can agree on is fuck the natives i can see both confederates and unionist agreeing to this. So instead of predominantly white people killing natives and taking their land it will be both white and black. Is there any way for them to better off?

Unfortunately, not even the Radical Republicans exhibited much sympathy towards the Indians. I do not see Lincoln, even a more radical one, doing much to help them along.

McClellan is slow and ponderous. He would react obviously to attacks, so the best way is for Lee to anticipate this and use the initial attack as a feint while the real one waits to smash the reaction

McClellan's two most obvious traits are his slowness and his cautiousness. Lee could probably exploit his willingness to retreat at the first sign of trouble and his unwillingness to committ at his reserves at any given battle.

I've got to say, the way you're building up the Peninsular battle is a fantastic example of how to grow tension. Even though we already know that the battle is going to be an unparalleled disaster for the North, and even though we already know that in the end the North is still going to win anyway, the repeated mentions of just how much of a cluster it's going to be has me twitching.

Eagerly awaiting more.

You know, I've often worried about that. I've made no secret that the war is ultimately going to end with an Union victory, or that the Peninsula Campaign will be a disaster for the Union. Under those circumstances, I've worried about how to grow tension. I'm glad to see I was able to do it despite the fact that you all know the outcome. Thanks!

i bet the repubilcans will be glad recall elections aren't a thing.this is gonna suck for the north.

Lee is very similar to hannibal now that i think about it..expect hannibals cause is probably more morally defensible.

The higher you go, the longest the fall. After reaching such a height of enthusiasm, the news that the war is going to continue is going to hurt a lot.

Chapter 32: Oft we've conquered and we'll conquer oft again

As December, 1862 started, George B. McClellan’s magnificent Army of the Susquehanna approached Richmond, close enough to hear its bells toll. Confederate clerks hurried to pack archives away, and the entire apparatus of government was making preparations to flee the city if necessary. President Breckenridge attempted to rally back his people by reminding them that that famous Virginian, George Washington, had also lost his capital only to retake it later. But the Yankees had also lost their capital, and panic took over the city as many Confederates feared that those Northern brigands would take revenge by burning Richmond to the ground. The Confederate War of Independence seemed about to end.

Confederate despair expressed itself through irate and often bitter attacks against their own leader. "The incredible incompetency of our Executive has brought us to the brink of ruin," said a South Carolina Congressman, while the Southern Literary Messenger denounced Breckenridge as “proud, unreasonable, inexperienced, incapable, even malignant. He is the cause of the very dark hour we have reached. While he lives, there is no hope." General Beauregard even self-servingly declared that Breckenridge was a “living specimen of gall & hatred . . . either demented or a traitor to his high trust. . . . If he were to die to-day, the whole country would rejoice at it, whereas, I believe, if the same thing were to happen to me, they would regret it.”

Breckenridge, though reportedly pained by these attacks, ignored them for the most part. It seems that Breckenridge increasingly came to blame them as fabrications by the opposition, which he denigrated as a Tory or Reconstructionist party. In any case, he was wise enough to not answer and thus alienate more men. Unfortunately for the embattled President, the actions of his government were more than enough to alienate large swathes of Southern public opinion. With Confederate prospects so bleak, new conscription laws and the establishment of martial law in several parts of the Confederacy were “justified by the needs of the hour.” This did not stop the critics, and even if Breckenridge vowed to "in forbearance and charity to turn away as well from the cats as the snakes”, the opposition continued to assail his policies.

The most common way was denouncing Breckenridge as “a terrible despot, who disregards our sacred liberties for the aggrandizement of his contemptible clique”, as a Richmond newspaper said. The establishment of military conscription, the main point of contention, was undoubtedly necessary, for otherwise the Armies of the Confederacy might have been depleted at a critical time, but this did not stop resistance to the draft. Even though the law had enjoyed high support within Congress, in the states there was considerable backlash. Politicians like Governors Zebulon Vance and Joseph Brown of North Carolina and Georgia respectively focused on the unconstitutionality of the measure. Aided by Davis, Breckenridge answered that the “necessary and proper” clause of the Confederate Constitution justified the draft, for the necessity was clear "when our very existence is threatened by armies vastly superior in numbers."

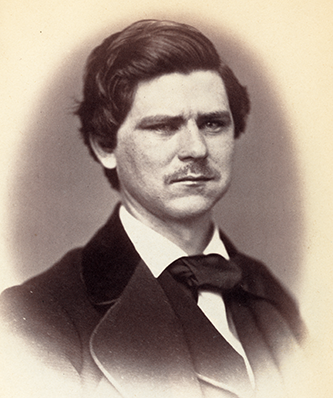

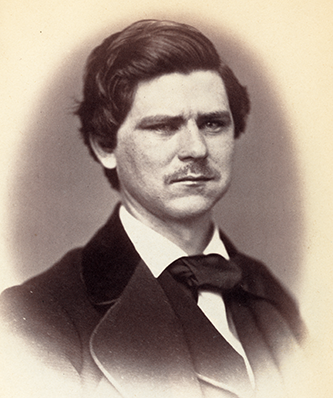

Zebulon Vance

Behind these constitutional debates, however, more concrete and harmful ways of opposing conscription took place. In many cases, this was because the draft was woefully unsuited to the necessities of a modern nation engaged in a war for its very survival. While in theory any man between eighteen and thirty-five could be called to serve the Confederacy, in practice there were ways of avoiding the draft. The most common was by paying for a substitute from those who were “not liable for duty”, which included immigrants and people outside the age group. Even though “the practice of buying substitutes had deep roots in European as well as American history”, being used in the American Revolution and the French levée en masse, it was, doubtlessly, an example of class legislation due to its very premise: that the people capable of hiring substitutes, that is, the wealthy, would be more valuable on the homefront.

This is not entirely illogical, since the organizational talents of planters and professionals would be necessary to keep the Confederate war machine going. A supplementary law was passed on April 21st, creating “several exempt categories: Confederate and state civil officials, railroad and river workers, telegraph operators, miners, several categories of industrial laborers, hospital personnel, clergymen, apothecaries, and teachers.” Despite the fact that neither planters nor overseers were excluded, to many poor men the conscription law seemed an unjust way of excepting the elites while the poor man was torn from home and sent marching to Yankee bayonets. The famous bitter saying “A rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight” demonstrated the widespread discontent that conscription created among the Southern poor.

The poor had several ways of expressing their opposition, most commonly “voting with their feet.” In several communities, farmers swore “they will be shot before they will fight for a country where the rich men's property is to be taken care of and those who have no overseers are to go and fight first." Fleeing to swamps or woods, these men resisted conscription at all costs, even sometimes violently repealing enrollment officers – James McPherson, for instance, comments that “armed bands of draft-dodgers and deserters ruled whole counties”. The situation was even more critical in regions where support for the Confederacy was low, such as the mountainous upcountry that leaned strongly towards Unionism. In those areas of independent farmers, the drafting of one or two members of a poor yeoman family could have devastating effects and lead to hardship and hunger because the labor of the entire family was needed for the cultivation of the soil. This helps explain their extreme opposition to conscription.

This discontentment naturally made enforcing the law a great challenge. In East Tennessee, a Unionist area that bitterly resented Confederate rule, "25,500 conscripts were enrolled, and yet only 6000 were added to the army," while Alabama’s governor had to admit that "the enforcement of the act in Alabama is a humbug and a farce." Others readily seized the opportunity afforded by the April 21st exemptions law, establishing new schools or opening apothecary shops with "a few empty jars, a cheap assortment of combs and brushes, a few bottles of 'hairdye' and Vizard oil' and other Yankee nostrums." A sullen War Department clerk commented that the Bureau of Conscription "ought to be called the Bureau of Exemptions."

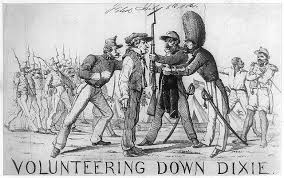

Conscription in the Confederacy

Tory governors, considering the draft an unconstitutional measure, helped along this resistance. The aforementioned Governors Brown and Vance, for example, appointed hundreds of militia officers and civil servants, who were exempted by the April 21st law. The result was that Georgia and North Carolina counted for 92% of state officials exempted from the draft, leading a Confederate general to say that a militia regiments from those states consisted of "3 field officers, 4 staff officers, 10 captains, 30 lieutenants, and 1 private with a misery in his bowels”. Similar lack of commitment to the Confederate cause was observed in other regards within many states. For example, North Carolina reserved all the cloth its forty textile mills produced for their militia, leaving nothing to the national army.

Internal divisions were not the only factors crippling the Confederate cause, for some aspects of the law also weakened Confederate industry and production at a critical time. Despite the fact that industrial workers had been exempted, some local officials did not obey the law and drafted them anyway, depriving factories of labor. This was all the more harmful when the draftees were skilled men that could not be easily replaced. Such was the case in a Richmond armory where “production fell off by at least 360 rifles per month after an expert barrel straightener was drafted” in defiance of the law. Foreign labor suffered a similar fate, and many skilled English and Germans workers of the pivotal Tredegar Iron Works fled to the North or Europe after conscription started. The disastrous consequence was that by the summer of 1863 “Tredegar had lost so many skilled puddlers . . . that only a third of the furnaces in the rolling mill were functioning.”

The obvious solution of using slaves as factory workers could not be fully implemented due to planter resistance. The Confederate government already impressed slaves and put them to work in army camps, building fortifications or in industrial factories, but planters loathed giving up their property, especially because Richmond was slow to pay. Moreover, many feared that using slave labor industrially would undermine the peculiar institution because being away from the plantation would give the slaves “a dangerous taste for independence” and infect them with “strange philosophies”. In the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, with the entire South alarmed at the prospect of slave insurrection, the idea of taking slaves away from the plantation and putting them near the Union Army was simply unacceptable.

Another factor that further weakened the Confederacy that sprung directly from conscription were new organized movements created to oppose the governments’ policies. For example, there was Choctaw County’s Loyal League, which sought to “break up the war by advising desertion, robbing the families of those who remained in the army and keeping the Federal authorities advised.” In western North Carolina, a similar effort was headed by the Heroes of America. Alexander H. Jones, one of them, explained that “this great national strife originated with men and measures that were . . . opposed to a democratic form of government . . . The fact is, these bombastic, highfalutin aristocratic fools have been in the habit of driving negroes and poor helpless white people until they think . . . that they themselves are superior; [and] hate, deride and suspicion the poor.”

The Tredegar Iron Works were essential to the Confederate war effort.

Despite all these factors, the conscription law did manage to fulfill its main objective of getting more men at arms and stimulating volunteering. Many men preferred to volunteers because then they could join new regiments alongside their neighbors and elect their own officers, while draftees were assigned to existing regiments. This allowed the Confederates to increase the size of their army from 375,000 to 500,000 men, an increase of some 250,000 soldiers if those who fell in the meantime are counted. Confederate nationalists, especially those in areas threatened by invasion, would pronounce the law a success. Even those who still doubted its constitutionality believed that "Our business now is to whip our enemies and save our homes . . . We can attend to questions of theory afterwards." The law was, furthermore, “upheld by every court in which it was tested.”

A similar belief that Northern invasion justified extreme measures led Breckenridge to decree martial law in Richmond towards the middle of 1862. Under the iron first of General John H. Winder, several measures were taken to curb “the rising crime and violence among the war-swollen population of the capital”. Along with pickpockets, thieves and drunkards, some Unionists were also jailed. Winder even went as far as threatening the Richmond Whig with closure after it compared these actions with Lincoln’s similar suppression of Confederate sentiment in Unionist Maryland. A diarist declared it “a reign of terror”, but others rejoiced in the law and order that Winder’s military police had brought to the city after it "arrested all loiterers, vagabonds, and suspicious-looking characters. . . . The consequences are peace, security, respect for life and property, and a thorough revival of patriotism."

At the same time that the Breckenridge administration was implementing these extreme measures, news tricked from the North that the Lincoln government, so often denounced as a tyranny, was softening its own methods. Nonetheless, with defeat so close, most Confederates welcomed Breckenridge’s decisiveness. "The Government must do all these things by military order”, declared the Richmond Examiner for instance, “To the dogs with Constitutional questions and moderation! What we want is an effectual resistance.” Unfortunately, this sometimes resulted in military overreach. Some commanders declared martial law on their authority, notably Van Dorn in Louisiana, and although Breckenridge forbid them from doing so, this kind of abuses continued. Louisiana’s governor would denounce it, declaring that "no free people can or ought to submit to [this] arbitrary and illegal usurpation of authority."

Martial law was an especially valuable tool when it came to enforcing conscription in several areas where judges issued writs of habeas corpus to free draftees. Breckenridge thus declared that suspending the writ was necessary so that “citizens of well-known disloyalty” would not “accomplish treason under the form of law” with “their advocacy of peace on the terms of submission and the abolition of slavery.” Bitter responses arose to this practice. A woman in Georgia wrote Breckenridge that the men in her area were "disgraceful, lawless, unfeeling and impolite men . . . They are running around over town and country insulting even weak unprotected women." Governor Vance too declared that suspension of the writ would shock “all worshippers of the Common law by hauling free men into sheriffless dungeons for opinions sake.”

As with conscription, Georgia was the cockpit of resistance to Breckenridge’s “despotism”. Governor Brown, Robert Toombs, and Breckenridge’s own Vice-President Alexander Stephens formed a powerful triumvirate that denounced conscription and martial law as unconstitutional despotism. "Away with the idea of getting independence first, and looking for liberty afterwards," Stephens asserted, "Our liberties, once lost, may be lost forever." Toombs joined him by denouncing the "infamous schemes of Breckenridge and his Jannissaries. . . . The road to liberty does not lie through slavery." Congress did attempt to limit Breckenridge’s war powers, but in a way remarkably similar to Lincoln’s, he simply ignored them and continued to suspend the writ of habeas corpus on his own authority.

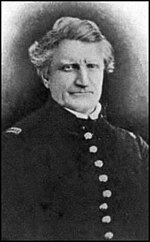

John H. Winder

Aside from fatal internal dissent, the Confederacy could add economic woes to its list of problems. The Cotton Kingdom had boasted of its economic wealth in the antebellum, but this meant that most Confederate capital was “tied up in the nonliquid form of land and slaves”. Breckenridge’s frantic efforts to sell as much cotton as possible before the Union blockade closed all ports had managed to add a little gold to the Confederacy’s coffers, but the fact was that the South desperately lacked specie. Yeoman farmers, mostly self-sustaining, had little need for it, while planters were for the most part in debt to Northern banks and firms and thus had little money to invest. Though the Confederacy had decreed that this debt should be paid to the Treasury in exchange for Confederate bonds, most planters preferred to conceal their debts. It was clear that revenue would have to be raised through other means.

However, attempts at establishing direct taxation floundered, mostly because the government lacked the bureaucracy necessary to enforce it and had to rely on states which previous to the war had collected few taxes and were rather opposed to them on principle. The result was that only South Carolina actually collected a 0.5% tax on real and personal property enacted in August 1861, while “all the other states paid their quotas not by collecting the tax, but by borrowing the money or printing it in the form of state notes.” Unfortunately for Richmond, this meant that little money was raised through taxes. Tariffs were also unsuccessful, due to a combination of Southern hostility to protectionism and the difficulties of trading through the blockade.

Efforts to finance the war through bonds also failed miserably because Southerners lacked money to invest. As McPherson says, Southerners “had to dip deeply into their reserves of patriotism to buy bonds at 8 percent when the rate of inflation had already reached 12 percent a month by the end of 1861.” Bleak Confederate prospects also eroded the trust of the people in eventual victory, which also lowered the sales of bonds. Treasury Secretary Memminger did create a “produce loan” that allowed farmers to buy bonds with their produce, but many preferred to sell it to Northerners who could pay in specie. Besides, even when that produce did reach government warehouses, the blockade meant that it couldn’t be sold. While in the North bonds sales were wildly successful, in the Confederacy they did not raise enough to sustain the armies of the fledging nation. In desperation, the Confederate government looked towards the printing press for salvation.

In this case, the remedy, if a remedy it was, was worse than the illness. Soon enough, millions of notes “that depreciated from the moment they came into existence” were printed. The government promised it would redeem them at specie after the end of the war, which meant that the notes were in effect “backed by the public's faith in the Confederacy's potential for survival”. The South’s weak economy and the bad course of the war thus meant that making them legal tender like the Union greenback would be inexpedient. Unable to coin its own money, the Confederacy allowed Union coins and even foreign currency to be circulated at fixed prices. To supplement this, small-denomination notes called “shinplasters” were also issued, though soon enough “individuals were cranking out unauthorized shinplasters by the thousands”.

A Confederate Grayback

All other “grayback” denominations were similarly affected by counterfeiting, chiefly because the quality of the notes was so low that sometimes counterfeit notes were superior to the genuine article. Southern state governments, cities, and even insurance companies issued their own notes, also contributing to the problem. Ruinous inflation and the lack of goods due to the blockade caused hardship in many families, and even those with comfortable salaries were hard pressed to maintain themselves with prices “rising at an almost constant rate of 10 per cent a month.” Alongside the discontentment already generated by the draft, this inflation caused a morale crisis that threatened to sink the Confederacy by fatally weakening popular support for it.

Mary Chesnut’s diary entries are proof of this. Towards the end of 1862 she wrote that "the Confederacy has been done to death by the politicians." Mary, the wife of the influential South Carolinian James Chesnut Jr., was certainly not poor, but a majority of poor Confederates probably shared her opinion and blamed the government for the hard times they had to endure. "There is now in this country much suffering amongst the poorer classes of Volunteers families," a Mississippi man reported “In the name of God, I ask is this to be tolerated? Is this war to be carried on and the Government upheld at the expense of the Starvation of the Women and children?" A supply officer would remark that "our battle against want and starvation is greater than against our enemies," while a woman wrote Breckinridge to declare that "If I and my little children suffer [and] die while there Father is in service I invoke God Almighty that our blood rest upon the South."

Dedicated to the cultivation of cash crops, the South had imported most of its food from Northern states. A patriotic effort to replace cotton and tobacco cultivation with corn and wheat started. Some states even forbid people from planting cotton, and to assure that grain would be used to feed the hungry they also prohibited the distillation of alcohol. Although Steven A. Channing claims that “unquestionably, the South managed to raise more than enough food to sustain the entire population”, the sad fact was that this food often rotted in far away barns while soldiers and civilians suffered from hunger due to the poor infrastructure and crumbling rail system of the Confederacy. Burdened with such impossible difficulties, the Confederate economy, and indeed the Confederacy itself, seemed ready to collapse unless some radical change managed to renew the people’s confidence.

In rode Robert E. Lee and his lean troopers to save the day. The Army of Northern Virginia, so dispirited after the defeats it had sustained under Beauregard and Johnston, had recuperated and was now ready to follow him on to victory. Most rebels were painfully aware that defeat meant the destruction of the Confederacy. They had to win, a soldier said, otherwise “we will lose everything we hold dear to the Lincolnite brigands . . . the very survival of our families hinges of this campaign.” “The protection of our homes from devastation and of our families from outrages depend on us,” a Virginia soldier declared, while an Alabama comrade added that if they failed “we will suffer the worst punishment ever inflicted on any people. We have to triumph.”

The Emancipation Proclamation stiffened their resolve, for they realized that defeat now meant the end of slavery and, they feared, the end of White Supremacy too. An Arkansas private wrote that if they were defeated then his "sister, wife, and mother are to be given up to the embraces of their present male servitors", and a Georgian feared Union victory because then they would be “irrevocably lost and not only will the negroes be free but . . . we will all be on a common level." Most soldiers probably agreed with a North Carolina soldier that boldly declared that he fought to show the Yankees “that a white man is better than a nigger.” Motivated by defense of hearth, family and slavery, Lee and his rebels went forward to face McClellan and the Union Army in November, 1862.

General Lee and his commanders. Secretary of War Davis was present for the battle, representing President Breckenridge.

In order to inflict a devastating defeat on the Federals, Lee had concentrated all available Confederate forces around Richmond. The canny Virginian was able to see that McClellan “will make this a battle of posts. He will take position from position, under cover of heavy guns, & we cannot get at him without storming his works, which with our new troops is extremely hazardous. . . . It will require 100,000 men to resist the regular siege of Richmond, which perhaps would only prolong not save it.” According to Ethan S. Rafuse, “Lee would enjoy numerical superiority with 112,220 men present for duty to McClellan’s 81,434”, but in the Confederate case this takes into account divisions that were, in fact, not present for duty. The most obvious example was that there were Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley and at Manassas, engaged in a tense standoff with Nathaniel Banks and John C. Frémont’s Union commands. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that, for perhaps the only time in the entire war, the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Susquehanna had roughly equal numbers.

McClellan could have easily surpassed Lee’s total numbers had he been able to bring the Union troops around Washington to the Peninsula. Some divisions had left Washington after it became apparent that almost the entire Confederate force was concentrated around Richmond. This gradually increased McClellan’s army’s size to 90,000 men, but the commander still believed himself outnumbered and clamored for more troops. In November 7th, he decided to lay siege on Richmond, justifying his decision by saying that he lacked enough numbers to directly assault the rebels. Lee, by that point, was already aware of McClellan’s timidity, and knew he would not act unless he was reinforced. Naturally, Lee decided that he could not allow any more troops to come from Washington, and to do so, he knew he had to threaten the city.

Lee may well have read Lincoln’s letter to McClellan explaining that Washington’s safety was a “question which the country will not allow me to evade”, for he proposed to send Stonewall Jackson to the Valley. A raid into Maryland and Pennsylvania, Lee hoped, “would call all the enemy from our Southern coast & liberate those states.” After relieving the pressure on Richmond through this attack, Jackson would be recalled to Richmond and would join Lee for an attack on the Union flank on the north side of the Chickahominy. This action was possible because part of McClellan’s army had crossed the river to prepare for the siege. While Lee prepared a line that could be held with only a fraction of the 60,000 actives he actually held at his disposal, Stonewall Jackson headed towards the Valley, about to pass into history.

In November 17th, 1862, Jackson and his “foot cavalry” marched across the blue ridge, misleading the Federals who believed he was pulling back to Richmond as well. But after reaching Charlottesville, they went back over the Blue Ridge to Staunton and inflicted a painful defeat on a smaller Union command that was part of Frémont’s force. Aided by rebel sympathizers such as Belle Boyd who informed them of Union movements and troops dispositions, Jackson managed to similarly mislead and divide the rest of the troops and overwhelm a Union force at Front Royal. This offensive had been very taxing on the poor soldiers, many of whom suffered immensely from privation and exhaustion. But Jackson spared them no sympathy. One soldier, for example, reported that "If a man's face was as white as cotton and his pulse so low you could scarcely feel it, he looked upon him merely as an inefficient soldier and rode off impatiently."

Their sacrifices, however, earned them great victories. They continued to push the disorganized Federals who were fleeing to Winchester and leaving behind “such a wealth of food and medical stores that Jackson's men labeled their opponent ‘Commissary Banks’”. A panicked Lincoln, knowing that he could not afford to lose Washington a second time, ordered Frémont to pursue Jackson and, more importantly, suspended the transfer of Hooker’s troops from Washington to the Peninsula, ordering him to send two divisions to the Valley and retain the 30,000 men he still had in order to defend Washington. Whether the events that followed were the fault of Lincoln for attempting to play military chess or the fault of the generals in command for failing to follow his orders is a point of contention, but the fact of the matter is that the offensives of Frémont, Banks and Hooker were chaotic and ineffective.

Stonewall Jackson's Way

The result was predictable: Union troops failed to attack the rebels when they had the opportunity, and they were in turn divided and overwhelmed by Jackson’s smaller force. Frémont failed to close Jackson’s southern escape route through Strasburg, and then failed to capture them as they reached Port Republic, the only intact bridge on the Shenandoah. When he finally faced Ewell’s division at Cross Keys, he didn’t commit his entire force even though he outnumbered Ewell, and then did nothing as one of the divisions sent by Hooker was defeated by Jackson. Jackson and Ewell then joined and together defeated Frémont, who also earned a nickname – “the Retreat-finder of the West.” After this victory, Jackson and his men returned to Richmond, where they finally could rest.

Jackson’s Valley campaign well earned its reputation as a brilliant offensive. With only 17,000 men, Stonewall Jackson defeated three different Union commands that far outnumbered him if put together. More importantly, he had diverted 60,000 men from the Peninsula and disrupted the reinforcement of McClellan’s army, thus playing a pivotal role in the victory that followed. Without Jackson, Hooker would have been able to completely reinforce McClellan, and though many doubt that the Union commander would have acted even if he had concentrated his entire force, Jackson’s actions still meant that the Confederates were not hopelessly outnumbered but could go toe to toe against the Yankees.

As the middle of December approached, the Chickahominy grew thanks to the rain of that unusually wet winter. Strong rains soon destroyed the bridges McClellan’s engineers had built, the only connection between the two wings of his army. The Northern wing, under the command of McClellan’s protégées, was expected to join with Hooker’s reinforcements, and consequently was smaller than the Southern wing. The Northern wing was, furthermore, “in the air”, that is, “unprotected by natural or man-made obstacles such as a river, right-angle fortifications, etc.”, a fact discovered by Jeb Stuart’s reconnaissance. This combination of factors may have seemed providential to Lee, who knew that men such as Porter would display timidity similar to McClellan’s instead of the initiative and ferocity needed to withstand an all-out attack. In December 21st, Lee started his attack against “those people”, the term he always used to refer to the Yankees.

As in the Valley, the attack was spearheaded by Jackson, who had been instructed to “sweep down between the Chickahominy and Pamunkey, cutting up the enemy’s communications.” This attack would entail an assault on the rear of Porter’s corps, which would then allow Lee to go forward and demolish his front. To make sure that McClellan would not intervene, a fake deserter was sent to tell the Union General that Lee actually planned to attack his southern flank. McClellan choose to believe this “very peculiar case of desertion”, in spite of the fact that some escaped contrabands had told him that Lee actually planned an attack by Jackson at Hanover Court House. Either McClellan’s arrogant contempt for Lee or his racism, amplified by the Emancipation Proclamation, has been blamed by this mistake; either way, the fact of the matter is that McClellan was nowhere to be found while Porter was assaulted at Mechanicsville.

The Battle of Mechanicsville

Though Porter counted with quality field fortifications, his infantry was badly demoralized. The destructive disarray within the Army of the Susquehanna meant that Porter and his commanders had trouble communicating, and at times political feuds, mainly over Emancipation, seemed more important than actually facing the enemy. Porter was surprised by Jackson’s attack, having assumed that McClellan and the Union left were ready to assault Richmond. Operating under this assumption, Porter turned and gave battle, and was caught unprepared when Lee swept forward. It seemed now that he would be crushed between two rebel pincers. Porter, however, refused to give in, believing that McClellan’s impending attack would force Lee back. Later, he declared that discussions with McClellan the previous day had made him believe that he was to oppose any offensive ‘‘even to my destruction.’’

That’s exactly what happened on December 22nd, when the rebel pincers closed and Porter’s corps finally broke. McClellan was finally roused from his slumber and had ordered him to retreat to Gaines’ Mill, a much stronger position, but it was too late, and instead of regrouping at Gaines’ Mill, Porter’s corps divided, with many soldiers fleeing northwards. Only some pitiful remains managed to cross the Chickahominy and reunite with the rest of the army. At this critical point, McClellan may have still seized victory from the jaws of defeat by going forward and attacking Richmond, thus stopping Lee’s attack and taking the rebel capital. The skeleton force he faced certainly would be unable to resist, but McClellan was still under the delusion that he actually faced an overwhelming force instead of 90,000. “I may be forced to give up my position”, he informed Stanton, “Had I twenty thousand fresh and good troops would be sure of a splendid victory tomorrow.”

At Mechanicsville, Porter had lost only 8,000 of the 30,000 men he had due to direct combat, but the rout at the very end of the battle meant that only 15,000 men remained on the North of the Chickahominy. Now Lee had 60,000 men in McClellan’s right, alongside some 30,000 in his front, the same 30,000 he had refused to assault earlier. McClellan was now, for the first time, actually outnumbered – 75,000 to Lee’s 90,000. His excellent defenses and superior artillery meant that he could have probably withstood Lee’s attacks long enough for reinforcements to come. Or he could do as General John Pope, recently brought from the West, suggested and retreat along the York River. McClellan, however, lost his nerve and decided to instead retreat to the James River. This decision would allow him to protect his army, his retreat route, and his supply lines, but it would move the Army of the Susquehanna away from the doorstep of Richmond. It was clear that McClellan’s priority was not taking Richmond, but saving his army, supposedly in mortal peril.

Declaring that he had suffered a “severe repulse to-day, having been attacked by greatly superior numbers”, he moved forward with his plans to evacuate to the James, ordering his supply depot at White House destroyed. Unfortunately for the Union, the indefatigable Stonewall Jackson managed to capture it before it was destroyed. McClellan, nonetheless, continued his retreat. As Rafuse points out, his other options were not much better: if he fled along the York as Lee hoped, he would leave his flanks open, while assaulting Richmond would strain his logistics. A bold general may well have made that attack, but McClellan prioritized having a clear escape route and a direct supply line, and thus could not do so. The day after the Mechanicsville disaster, he wired Philadelphia to say that "The rebel force is stated at 200,000, including Jackson . . . I shall have to contend against vastly superior odds. . . . If [the army] is destroyed by overwhelming numbers . . . the responsibility cannot be thrown on my shoulders; it must rest where it belongs."

The Army of the Susquehanna retreats

While McClellan panicked, “paralyzed by fear, delusion, and exhaustion”, Lee acted. Jackson once again attack the Federals, and the reputation he had earned at the Valley gave him such a psychological edge over his adversaries that they put up but little resistance as the rebels attacked the Union right. Meanwhile, A. P. Hill, aided by a feint made by Longstreet, assailed the Union center. The remnants of Porter’s corps were finally destroyed as McClellan refused to reinforce them, more preoccupied with securing his retreat to the James. The bluecoats lost another 8,000 to combat and 2,000 more were captured, including Porter. The north flank of the Army of the Susquehanna had now been completely destroyed, and now Lee could focus on the southern flank. On December 25th, a wide offensive started and hit the retreating McClellan on the flank.

As McClellan retreated, he sent a defiant telegraph to Washington. "I have lost this battle because my force was too small. . . . The Government has not sustained this army. . . . If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army." Stanton and Lincoln, waiting anxiously in the telegraph station of the War Department, could not believe their eyes as they read this unsubordinated message, yet they could not remove McClellan because to do so in the middle of such catastrophe would only create an even bigger disaster. Mentally whipped, his will broken by the events of the last few days, McClellan did not exhibit decision, initiative or valor as Lee scored a Cannae.

On December 26th, McClellan abandoned three Union divisions that were guarding some 7,000 wounded men, and although the Yankees offered stout resistance, at the end they had to surrender and Hill took some 12,000 captives. McClellan similarly abandoned several divisions at White Oak Swamp, where seven Confederate divisions converged on five Union divisions. Finally, the Army of the Susquehanna stopped at Malvern Hill, near their destination. The high ground was bound to protect them, but the will of the Yankees was completely destroyed. Stragglers fell by the thousands, wounded men were left behind, commanders were captured, and weapons and ordinance were abandoned – Lee and his men reaped some 50,000 small arms and almost 40 cannons.

The Battle of Malvern Hill

More importantly, most of the few men McClellan trusted were on the North side of the Chickahominy – and that part of the army had been destroyed. The men who were with McClellan were the “abolitionist” officers he often showed contempt for, and many of the men were fatally demoralized by defeat. Some have claimed that the Emancipation Proclamation also caused a morale crisis among the ranks, for a good part of the men refused to fight for emancipation, but this narrative has been questioned. In any case, on December 28th, rebel shells hit the Union defenses, and the Yankee response was feeble and disjointed even though its artillery was superior. Longstreet and Hill followed this with an assault that would have been murder under normal circumstances, but by then the enemy was so dispirited that they could not mount an effective defense.

A Union corps, under the command of Sumner, an anti-McClellan general, was surrounded by the rebels. Considering that to save the rest of his army he needed to abandon Sumner, McClellan refused to counterattack and continued his retreat to the James. Brigadier General Philip Kearny exploded at hearing the news, exclaiming that "Such an order can only be prompted by cowardice or treason. . . . We ought instead of retreating to follow up the enemy and rescue our comrades." Dark whispers abounded claiming that McClellan abandoned Sumner as a punishment for his “radicalism”; Lincoln himself said that McClellan’s behavior was “unpardonable” and that he “wanted Sumner to fail.” Finally, McClellan and what remained of his army arrived at Harrison’s Landing and departed. The besieged Sumner, his will broken by McClellan’s treachery, surrendered his command a week later.

Altogether, the Army of the Susquehanna had lost two of its corps, or a total of 50,000 men killed or captured. Of the 40,000 men who fled with McClellan, 10,000 were wounded. The rebels had lost just 20,000 men, which was a dear price indeed, but was more than justified taking into account just how disastrous the battle had been for the Union. Perhaps Lee was too sanguine in his pronouncement that “those people” had been destroyed. What cannot be denied is that at the end of the Nine Days' Battles Lee had achieved a gigantic success, not only defeating the Federal tactically at every encounter, but saving his capital and the Confederacy itself. This Cannae, however, was deeply ironical, for in assuring the prolongation of the war Lee also assured the eventual destruction of slavery and everything the South fought for. But as 1863 started and the news of this catastrophe reached the North, many Northerners started to fear that Confederate victory was inevitable.

Confederate despair expressed itself through irate and often bitter attacks against their own leader. "The incredible incompetency of our Executive has brought us to the brink of ruin," said a South Carolina Congressman, while the Southern Literary Messenger denounced Breckenridge as “proud, unreasonable, inexperienced, incapable, even malignant. He is the cause of the very dark hour we have reached. While he lives, there is no hope." General Beauregard even self-servingly declared that Breckenridge was a “living specimen of gall & hatred . . . either demented or a traitor to his high trust. . . . If he were to die to-day, the whole country would rejoice at it, whereas, I believe, if the same thing were to happen to me, they would regret it.”

Breckenridge, though reportedly pained by these attacks, ignored them for the most part. It seems that Breckenridge increasingly came to blame them as fabrications by the opposition, which he denigrated as a Tory or Reconstructionist party. In any case, he was wise enough to not answer and thus alienate more men. Unfortunately for the embattled President, the actions of his government were more than enough to alienate large swathes of Southern public opinion. With Confederate prospects so bleak, new conscription laws and the establishment of martial law in several parts of the Confederacy were “justified by the needs of the hour.” This did not stop the critics, and even if Breckenridge vowed to "in forbearance and charity to turn away as well from the cats as the snakes”, the opposition continued to assail his policies.

The most common way was denouncing Breckenridge as “a terrible despot, who disregards our sacred liberties for the aggrandizement of his contemptible clique”, as a Richmond newspaper said. The establishment of military conscription, the main point of contention, was undoubtedly necessary, for otherwise the Armies of the Confederacy might have been depleted at a critical time, but this did not stop resistance to the draft. Even though the law had enjoyed high support within Congress, in the states there was considerable backlash. Politicians like Governors Zebulon Vance and Joseph Brown of North Carolina and Georgia respectively focused on the unconstitutionality of the measure. Aided by Davis, Breckenridge answered that the “necessary and proper” clause of the Confederate Constitution justified the draft, for the necessity was clear "when our very existence is threatened by armies vastly superior in numbers."

Zebulon Vance

Behind these constitutional debates, however, more concrete and harmful ways of opposing conscription took place. In many cases, this was because the draft was woefully unsuited to the necessities of a modern nation engaged in a war for its very survival. While in theory any man between eighteen and thirty-five could be called to serve the Confederacy, in practice there were ways of avoiding the draft. The most common was by paying for a substitute from those who were “not liable for duty”, which included immigrants and people outside the age group. Even though “the practice of buying substitutes had deep roots in European as well as American history”, being used in the American Revolution and the French levée en masse, it was, doubtlessly, an example of class legislation due to its very premise: that the people capable of hiring substitutes, that is, the wealthy, would be more valuable on the homefront.

This is not entirely illogical, since the organizational talents of planters and professionals would be necessary to keep the Confederate war machine going. A supplementary law was passed on April 21st, creating “several exempt categories: Confederate and state civil officials, railroad and river workers, telegraph operators, miners, several categories of industrial laborers, hospital personnel, clergymen, apothecaries, and teachers.” Despite the fact that neither planters nor overseers were excluded, to many poor men the conscription law seemed an unjust way of excepting the elites while the poor man was torn from home and sent marching to Yankee bayonets. The famous bitter saying “A rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight” demonstrated the widespread discontent that conscription created among the Southern poor.

The poor had several ways of expressing their opposition, most commonly “voting with their feet.” In several communities, farmers swore “they will be shot before they will fight for a country where the rich men's property is to be taken care of and those who have no overseers are to go and fight first." Fleeing to swamps or woods, these men resisted conscription at all costs, even sometimes violently repealing enrollment officers – James McPherson, for instance, comments that “armed bands of draft-dodgers and deserters ruled whole counties”. The situation was even more critical in regions where support for the Confederacy was low, such as the mountainous upcountry that leaned strongly towards Unionism. In those areas of independent farmers, the drafting of one or two members of a poor yeoman family could have devastating effects and lead to hardship and hunger because the labor of the entire family was needed for the cultivation of the soil. This helps explain their extreme opposition to conscription.

This discontentment naturally made enforcing the law a great challenge. In East Tennessee, a Unionist area that bitterly resented Confederate rule, "25,500 conscripts were enrolled, and yet only 6000 were added to the army," while Alabama’s governor had to admit that "the enforcement of the act in Alabama is a humbug and a farce." Others readily seized the opportunity afforded by the April 21st exemptions law, establishing new schools or opening apothecary shops with "a few empty jars, a cheap assortment of combs and brushes, a few bottles of 'hairdye' and Vizard oil' and other Yankee nostrums." A sullen War Department clerk commented that the Bureau of Conscription "ought to be called the Bureau of Exemptions."

Conscription in the Confederacy

Tory governors, considering the draft an unconstitutional measure, helped along this resistance. The aforementioned Governors Brown and Vance, for example, appointed hundreds of militia officers and civil servants, who were exempted by the April 21st law. The result was that Georgia and North Carolina counted for 92% of state officials exempted from the draft, leading a Confederate general to say that a militia regiments from those states consisted of "3 field officers, 4 staff officers, 10 captains, 30 lieutenants, and 1 private with a misery in his bowels”. Similar lack of commitment to the Confederate cause was observed in other regards within many states. For example, North Carolina reserved all the cloth its forty textile mills produced for their militia, leaving nothing to the national army.

Internal divisions were not the only factors crippling the Confederate cause, for some aspects of the law also weakened Confederate industry and production at a critical time. Despite the fact that industrial workers had been exempted, some local officials did not obey the law and drafted them anyway, depriving factories of labor. This was all the more harmful when the draftees were skilled men that could not be easily replaced. Such was the case in a Richmond armory where “production fell off by at least 360 rifles per month after an expert barrel straightener was drafted” in defiance of the law. Foreign labor suffered a similar fate, and many skilled English and Germans workers of the pivotal Tredegar Iron Works fled to the North or Europe after conscription started. The disastrous consequence was that by the summer of 1863 “Tredegar had lost so many skilled puddlers . . . that only a third of the furnaces in the rolling mill were functioning.”

The obvious solution of using slaves as factory workers could not be fully implemented due to planter resistance. The Confederate government already impressed slaves and put them to work in army camps, building fortifications or in industrial factories, but planters loathed giving up their property, especially because Richmond was slow to pay. Moreover, many feared that using slave labor industrially would undermine the peculiar institution because being away from the plantation would give the slaves “a dangerous taste for independence” and infect them with “strange philosophies”. In the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, with the entire South alarmed at the prospect of slave insurrection, the idea of taking slaves away from the plantation and putting them near the Union Army was simply unacceptable.

Another factor that further weakened the Confederacy that sprung directly from conscription were new organized movements created to oppose the governments’ policies. For example, there was Choctaw County’s Loyal League, which sought to “break up the war by advising desertion, robbing the families of those who remained in the army and keeping the Federal authorities advised.” In western North Carolina, a similar effort was headed by the Heroes of America. Alexander H. Jones, one of them, explained that “this great national strife originated with men and measures that were . . . opposed to a democratic form of government . . . The fact is, these bombastic, highfalutin aristocratic fools have been in the habit of driving negroes and poor helpless white people until they think . . . that they themselves are superior; [and] hate, deride and suspicion the poor.”

The Tredegar Iron Works were essential to the Confederate war effort.

Despite all these factors, the conscription law did manage to fulfill its main objective of getting more men at arms and stimulating volunteering. Many men preferred to volunteers because then they could join new regiments alongside their neighbors and elect their own officers, while draftees were assigned to existing regiments. This allowed the Confederates to increase the size of their army from 375,000 to 500,000 men, an increase of some 250,000 soldiers if those who fell in the meantime are counted. Confederate nationalists, especially those in areas threatened by invasion, would pronounce the law a success. Even those who still doubted its constitutionality believed that "Our business now is to whip our enemies and save our homes . . . We can attend to questions of theory afterwards." The law was, furthermore, “upheld by every court in which it was tested.”

A similar belief that Northern invasion justified extreme measures led Breckenridge to decree martial law in Richmond towards the middle of 1862. Under the iron first of General John H. Winder, several measures were taken to curb “the rising crime and violence among the war-swollen population of the capital”. Along with pickpockets, thieves and drunkards, some Unionists were also jailed. Winder even went as far as threatening the Richmond Whig with closure after it compared these actions with Lincoln’s similar suppression of Confederate sentiment in Unionist Maryland. A diarist declared it “a reign of terror”, but others rejoiced in the law and order that Winder’s military police had brought to the city after it "arrested all loiterers, vagabonds, and suspicious-looking characters. . . . The consequences are peace, security, respect for life and property, and a thorough revival of patriotism."

At the same time that the Breckenridge administration was implementing these extreme measures, news tricked from the North that the Lincoln government, so often denounced as a tyranny, was softening its own methods. Nonetheless, with defeat so close, most Confederates welcomed Breckenridge’s decisiveness. "The Government must do all these things by military order”, declared the Richmond Examiner for instance, “To the dogs with Constitutional questions and moderation! What we want is an effectual resistance.” Unfortunately, this sometimes resulted in military overreach. Some commanders declared martial law on their authority, notably Van Dorn in Louisiana, and although Breckenridge forbid them from doing so, this kind of abuses continued. Louisiana’s governor would denounce it, declaring that "no free people can or ought to submit to [this] arbitrary and illegal usurpation of authority."

Martial law was an especially valuable tool when it came to enforcing conscription in several areas where judges issued writs of habeas corpus to free draftees. Breckenridge thus declared that suspending the writ was necessary so that “citizens of well-known disloyalty” would not “accomplish treason under the form of law” with “their advocacy of peace on the terms of submission and the abolition of slavery.” Bitter responses arose to this practice. A woman in Georgia wrote Breckenridge that the men in her area were "disgraceful, lawless, unfeeling and impolite men . . . They are running around over town and country insulting even weak unprotected women." Governor Vance too declared that suspension of the writ would shock “all worshippers of the Common law by hauling free men into sheriffless dungeons for opinions sake.”

As with conscription, Georgia was the cockpit of resistance to Breckenridge’s “despotism”. Governor Brown, Robert Toombs, and Breckenridge’s own Vice-President Alexander Stephens formed a powerful triumvirate that denounced conscription and martial law as unconstitutional despotism. "Away with the idea of getting independence first, and looking for liberty afterwards," Stephens asserted, "Our liberties, once lost, may be lost forever." Toombs joined him by denouncing the "infamous schemes of Breckenridge and his Jannissaries. . . . The road to liberty does not lie through slavery." Congress did attempt to limit Breckenridge’s war powers, but in a way remarkably similar to Lincoln’s, he simply ignored them and continued to suspend the writ of habeas corpus on his own authority.

John H. Winder

Aside from fatal internal dissent, the Confederacy could add economic woes to its list of problems. The Cotton Kingdom had boasted of its economic wealth in the antebellum, but this meant that most Confederate capital was “tied up in the nonliquid form of land and slaves”. Breckenridge’s frantic efforts to sell as much cotton as possible before the Union blockade closed all ports had managed to add a little gold to the Confederacy’s coffers, but the fact was that the South desperately lacked specie. Yeoman farmers, mostly self-sustaining, had little need for it, while planters were for the most part in debt to Northern banks and firms and thus had little money to invest. Though the Confederacy had decreed that this debt should be paid to the Treasury in exchange for Confederate bonds, most planters preferred to conceal their debts. It was clear that revenue would have to be raised through other means.

However, attempts at establishing direct taxation floundered, mostly because the government lacked the bureaucracy necessary to enforce it and had to rely on states which previous to the war had collected few taxes and were rather opposed to them on principle. The result was that only South Carolina actually collected a 0.5% tax on real and personal property enacted in August 1861, while “all the other states paid their quotas not by collecting the tax, but by borrowing the money or printing it in the form of state notes.” Unfortunately for Richmond, this meant that little money was raised through taxes. Tariffs were also unsuccessful, due to a combination of Southern hostility to protectionism and the difficulties of trading through the blockade.

Efforts to finance the war through bonds also failed miserably because Southerners lacked money to invest. As McPherson says, Southerners “had to dip deeply into their reserves of patriotism to buy bonds at 8 percent when the rate of inflation had already reached 12 percent a month by the end of 1861.” Bleak Confederate prospects also eroded the trust of the people in eventual victory, which also lowered the sales of bonds. Treasury Secretary Memminger did create a “produce loan” that allowed farmers to buy bonds with their produce, but many preferred to sell it to Northerners who could pay in specie. Besides, even when that produce did reach government warehouses, the blockade meant that it couldn’t be sold. While in the North bonds sales were wildly successful, in the Confederacy they did not raise enough to sustain the armies of the fledging nation. In desperation, the Confederate government looked towards the printing press for salvation.

In this case, the remedy, if a remedy it was, was worse than the illness. Soon enough, millions of notes “that depreciated from the moment they came into existence” were printed. The government promised it would redeem them at specie after the end of the war, which meant that the notes were in effect “backed by the public's faith in the Confederacy's potential for survival”. The South’s weak economy and the bad course of the war thus meant that making them legal tender like the Union greenback would be inexpedient. Unable to coin its own money, the Confederacy allowed Union coins and even foreign currency to be circulated at fixed prices. To supplement this, small-denomination notes called “shinplasters” were also issued, though soon enough “individuals were cranking out unauthorized shinplasters by the thousands”.

A Confederate Grayback

All other “grayback” denominations were similarly affected by counterfeiting, chiefly because the quality of the notes was so low that sometimes counterfeit notes were superior to the genuine article. Southern state governments, cities, and even insurance companies issued their own notes, also contributing to the problem. Ruinous inflation and the lack of goods due to the blockade caused hardship in many families, and even those with comfortable salaries were hard pressed to maintain themselves with prices “rising at an almost constant rate of 10 per cent a month.” Alongside the discontentment already generated by the draft, this inflation caused a morale crisis that threatened to sink the Confederacy by fatally weakening popular support for it.

Mary Chesnut’s diary entries are proof of this. Towards the end of 1862 she wrote that "the Confederacy has been done to death by the politicians." Mary, the wife of the influential South Carolinian James Chesnut Jr., was certainly not poor, but a majority of poor Confederates probably shared her opinion and blamed the government for the hard times they had to endure. "There is now in this country much suffering amongst the poorer classes of Volunteers families," a Mississippi man reported “In the name of God, I ask is this to be tolerated? Is this war to be carried on and the Government upheld at the expense of the Starvation of the Women and children?" A supply officer would remark that "our battle against want and starvation is greater than against our enemies," while a woman wrote Breckinridge to declare that "If I and my little children suffer [and] die while there Father is in service I invoke God Almighty that our blood rest upon the South."

Dedicated to the cultivation of cash crops, the South had imported most of its food from Northern states. A patriotic effort to replace cotton and tobacco cultivation with corn and wheat started. Some states even forbid people from planting cotton, and to assure that grain would be used to feed the hungry they also prohibited the distillation of alcohol. Although Steven A. Channing claims that “unquestionably, the South managed to raise more than enough food to sustain the entire population”, the sad fact was that this food often rotted in far away barns while soldiers and civilians suffered from hunger due to the poor infrastructure and crumbling rail system of the Confederacy. Burdened with such impossible difficulties, the Confederate economy, and indeed the Confederacy itself, seemed ready to collapse unless some radical change managed to renew the people’s confidence.

In rode Robert E. Lee and his lean troopers to save the day. The Army of Northern Virginia, so dispirited after the defeats it had sustained under Beauregard and Johnston, had recuperated and was now ready to follow him on to victory. Most rebels were painfully aware that defeat meant the destruction of the Confederacy. They had to win, a soldier said, otherwise “we will lose everything we hold dear to the Lincolnite brigands . . . the very survival of our families hinges of this campaign.” “The protection of our homes from devastation and of our families from outrages depend on us,” a Virginia soldier declared, while an Alabama comrade added that if they failed “we will suffer the worst punishment ever inflicted on any people. We have to triumph.”

The Emancipation Proclamation stiffened their resolve, for they realized that defeat now meant the end of slavery and, they feared, the end of White Supremacy too. An Arkansas private wrote that if they were defeated then his "sister, wife, and mother are to be given up to the embraces of their present male servitors", and a Georgian feared Union victory because then they would be “irrevocably lost and not only will the negroes be free but . . . we will all be on a common level." Most soldiers probably agreed with a North Carolina soldier that boldly declared that he fought to show the Yankees “that a white man is better than a nigger.” Motivated by defense of hearth, family and slavery, Lee and his rebels went forward to face McClellan and the Union Army in November, 1862.

General Lee and his commanders. Secretary of War Davis was present for the battle, representing President Breckenridge.

In order to inflict a devastating defeat on the Federals, Lee had concentrated all available Confederate forces around Richmond. The canny Virginian was able to see that McClellan “will make this a battle of posts. He will take position from position, under cover of heavy guns, & we cannot get at him without storming his works, which with our new troops is extremely hazardous. . . . It will require 100,000 men to resist the regular siege of Richmond, which perhaps would only prolong not save it.” According to Ethan S. Rafuse, “Lee would enjoy numerical superiority with 112,220 men present for duty to McClellan’s 81,434”, but in the Confederate case this takes into account divisions that were, in fact, not present for duty. The most obvious example was that there were Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley and at Manassas, engaged in a tense standoff with Nathaniel Banks and John C. Frémont’s Union commands. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that, for perhaps the only time in the entire war, the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Susquehanna had roughly equal numbers.

McClellan could have easily surpassed Lee’s total numbers had he been able to bring the Union troops around Washington to the Peninsula. Some divisions had left Washington after it became apparent that almost the entire Confederate force was concentrated around Richmond. This gradually increased McClellan’s army’s size to 90,000 men, but the commander still believed himself outnumbered and clamored for more troops. In November 7th, he decided to lay siege on Richmond, justifying his decision by saying that he lacked enough numbers to directly assault the rebels. Lee, by that point, was already aware of McClellan’s timidity, and knew he would not act unless he was reinforced. Naturally, Lee decided that he could not allow any more troops to come from Washington, and to do so, he knew he had to threaten the city.

Lee may well have read Lincoln’s letter to McClellan explaining that Washington’s safety was a “question which the country will not allow me to evade”, for he proposed to send Stonewall Jackson to the Valley. A raid into Maryland and Pennsylvania, Lee hoped, “would call all the enemy from our Southern coast & liberate those states.” After relieving the pressure on Richmond through this attack, Jackson would be recalled to Richmond and would join Lee for an attack on the Union flank on the north side of the Chickahominy. This action was possible because part of McClellan’s army had crossed the river to prepare for the siege. While Lee prepared a line that could be held with only a fraction of the 60,000 actives he actually held at his disposal, Stonewall Jackson headed towards the Valley, about to pass into history.

In November 17th, 1862, Jackson and his “foot cavalry” marched across the blue ridge, misleading the Federals who believed he was pulling back to Richmond as well. But after reaching Charlottesville, they went back over the Blue Ridge to Staunton and inflicted a painful defeat on a smaller Union command that was part of Frémont’s force. Aided by rebel sympathizers such as Belle Boyd who informed them of Union movements and troops dispositions, Jackson managed to similarly mislead and divide the rest of the troops and overwhelm a Union force at Front Royal. This offensive had been very taxing on the poor soldiers, many of whom suffered immensely from privation and exhaustion. But Jackson spared them no sympathy. One soldier, for example, reported that "If a man's face was as white as cotton and his pulse so low you could scarcely feel it, he looked upon him merely as an inefficient soldier and rode off impatiently."

Their sacrifices, however, earned them great victories. They continued to push the disorganized Federals who were fleeing to Winchester and leaving behind “such a wealth of food and medical stores that Jackson's men labeled their opponent ‘Commissary Banks’”. A panicked Lincoln, knowing that he could not afford to lose Washington a second time, ordered Frémont to pursue Jackson and, more importantly, suspended the transfer of Hooker’s troops from Washington to the Peninsula, ordering him to send two divisions to the Valley and retain the 30,000 men he still had in order to defend Washington. Whether the events that followed were the fault of Lincoln for attempting to play military chess or the fault of the generals in command for failing to follow his orders is a point of contention, but the fact of the matter is that the offensives of Frémont, Banks and Hooker were chaotic and ineffective.

Stonewall Jackson's Way

The result was predictable: Union troops failed to attack the rebels when they had the opportunity, and they were in turn divided and overwhelmed by Jackson’s smaller force. Frémont failed to close Jackson’s southern escape route through Strasburg, and then failed to capture them as they reached Port Republic, the only intact bridge on the Shenandoah. When he finally faced Ewell’s division at Cross Keys, he didn’t commit his entire force even though he outnumbered Ewell, and then did nothing as one of the divisions sent by Hooker was defeated by Jackson. Jackson and Ewell then joined and together defeated Frémont, who also earned a nickname – “the Retreat-finder of the West.” After this victory, Jackson and his men returned to Richmond, where they finally could rest.