The eastern theater of the American Civil War has usually received the lion’s share of attention and press, both during the war itself and even many years after the conflict. But in truth, even if the Union came close to losing the war in the East, at the end the Confederacy lost it in the West. This did not mean that the Union did not suffer severe seatbacks in that theater of war as well. The failures of 1862-1863 in both East and West combined to make these months the nadir of the Union cause and high-water mark of the Confederacy.

After taking Corinth on June, 1862, Grant settled down on his new headquarters at Memphis. A “secesh town” that bitterly resented Union rule, Memphis was in a state of constant upheaval. Corinth, too, was in a bad shape, as the horrors of a prolonged siege and deadly illnesses had left it “a town of burning houses, shattered windows, and rotting food dumped into the streets”. “Soldiers who fight battles do not experience half their horrors,” mused Grant to his wife. “All the hardships come upon the weak . . . women and children.” Grant was, altogether, a rather magnanimous conqueror, doing his best to listen to the grievances of the Southerners and protect them from being “rough handled” by his soldiers. One famous anecdote even has Grant personally striking a soldier who was assaulting a woman.

The Southern people, however, did not repay Grant’s kindness with the same token, but instead showed enormous support to the Confederate army and ruthless Southern partisans who were doing their best to impair Grant’s military operations. Cutting telegraph wires, destroying bridges and railroads, and attacking Union supply depots, these partisans were a constant danger. They were bolstered by their support among Southern civilians, who informed them of Union movement, smuggled contraband to sustain them, and provided them with homes to rest and regroup whenever Union cavalry forced them to disappear into the mountains. Grant’s situation was aggravated by the needs of other commanders, as several of his divisions were sent east to Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio in order to aid in the invasion of East Tennessee.

Grant recognized the simple fact that, unlike what some Northerners believed, the Confederacy actually enjoyed enormous popular support. And although he had been able to take the fighting to the very heart of the Confederacy, this meant that his supply lines were longer and many more soldiers were needed to protect them from rebel attacks. By contrast, retreating Southerners were able to concentrate their forces and even increase them as patrols guarding supply lines or garrisoning cities joined the main commands. Determined to engage in “a vigorous prosecution of the war by all the means known to civilized warfare” as Washburne said the administration intended to, Grant made Southern cities responsible for rebel raids and even threatened to “desolate their country for forty miles around every place” that Southern partisans attacked.

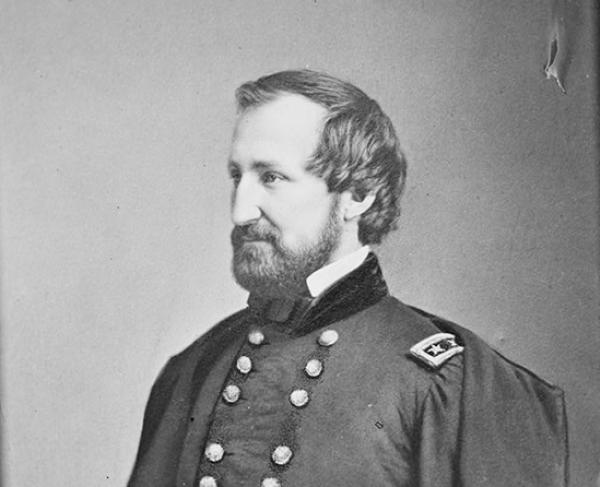

John Hunt Morgan was one of the more talented rebel raiders

Grant marched in lockstep with the administration not only in the turn towards a hard war but also in the policies regarding the contrabands. An apolitical man who in later years admitted with some shame that he had voted for Buchanan in 1856 and had supported Lincoln only reluctantly, Grant had nonetheless undergone a political transformation. Whereas he had once believed that Northern radicals deserved as much blame for the start of the war as Southern fire-eaters, he now expressed strong anti-slavery views and great compassion for the contrabands. Accordingly, he received all the contrabands that came within his lines, giving them clothes, food and even tobacco. “I don’t know what is to become of these poor people in the end”, he admitted, but despite this Grant took decisive steps to aid the contrabands in their journey from slavery to freedom.

Grant’s most decisive action was probably appointing John Eaton as superintendent of contrabands in the Mississippi Valley in August, 1862, just a few weeks after the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued. A native of New Hampshire who had been educated in Dartmouth College before joining the army as the chaplain of an Ohio regiment, Eaton was a man of great compassion and ability. He would need both, for he faced a daunting task. Even before the Emancipation Proclamation, contrabands flocked to Union camps by the thousands; afterwards, their number increased dramatically. The army, “ill-equipped to function as a welfare agency”, had been unable to take adequate care of the former slaves, who huddled in makeshift shantytowns built around army camps, suffering from disease and exposure. Eaton recognized that he was trusted with “an enterprise beyond the possibility of human achievement”, yet he threw himself wholeheartedly behind it, doing his best to provide medicine, employment and education to the freedmen.

Eaton reported that Grant even envisioned a future where, after the Negro proved his worth as a soldier, it would be possible to “put the ballot in his hand and make him a citizen”, He went on to declare that “Obviously I was dealing with no incompetent, but a man capable of handling large issues. Never before in those early and bewildering days had I heard the problem of the future of the Negro attacked so vigorously and with such humanity combined with practical good sense.” Grant worked closely with his aides “to feed and clothe all, old and young, male and female,” and “to build them comfortable cabins, hospitals for the sick, and to supply them with many comforts they had never known before.” Grant was in many ways one of the commanders who did the most for the Freedmen. Frederick Douglass would forever warmly remember how Grant “was always up with, or in advance of authority furnished from Washington in regard to the treatment of those of our color then slaves.”

Grant also readily cooperated with Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. Sent West by the War Department to help along in the recruitment of Black troops, Thomas was engaged in a tireless crusade against prejudice within the army, for many Yankee soldiers still bitterly opposed the enlistment of Black soldiers. Grant and Thomas quickly forged a good partnership, Thomas even declaring himself “a Grant man all over.” Soon enough, some twenty-thousand Black men were taken from the contraband camps around the Army of the Tennessee and organized into a corps of U.S. Colored Infantry. Grant wired to Philadelphia that “At least three of my Army Corps Commanders take hold of the new policy of arming the negroes and using them against the rebels with a will”, adding too that the administration “may rely on my carrying out any policy ordered by proper authority to the best of my ability.” This willingness to faithfully execute the government’s policies instead of challenging them like other Generals did helps explain Grant’s success.

The new Black regiments were a welcome addition, for Grant desperately needed the manpower. In the middle of an enormous territory, Grant’s 50,000 bluecoats were but a “pittance” as Ron Chernow says. During most of this period Grant had no option but to play defense, even as he itched to start a general offensive against Vicksburg. At least Grant was safe from counterattacks, since A. S. Johnston too lacked the manpower to take the initiative. Both main armies simply warily watched each other, the only action taken during these months being a few skirmishes that, although hardly fought were rather inconsequential. Breckenridge was at that moment almost completely focused on the east, where it seemed like McClellan’s army was about to take Richmond. Believing that it was not the time for fruitless attacks, he ordered all commanders to simply hold their territory. Johnston was not completely happy with this decision, but he followed it nonetheless with soldierly good-faith.

However, the order did not exactly mean that no action whatsoever was allowed, and Johnston decided to start a series of “hit and run” attacks that would weaken Grant and stave off any campaign against Vicksburg. To simply sit and do nothing, Johnston argued, would not only fatally demoralize his command, but would also cede the initiative to the Union and allow them to concentrate their “abolitionist hordes and Negro soldiers” for an overwhelming attack. Quick and decisive engagements would, on the other hand, disorganize and delay Grant. Breckenridge was convinced by these arguments and allowed Johnston to proceed on the condition that no “permanent occupation” was sought. “It is of no use to liberate Tennessee if we lose Vicksburg”, the President reasoned. “As much as it pains me to admit it, our present resources forbid any attempt at invading the Yankee nation . . . The day shall come when Lincoln’s abolitionist hirelings are expulsed from our soil – for now, let us focus on defending the lands still under our control.”

Consequently, in September 1862, Johnston had hatched a plan to draw Grant into open battle, where he could possible suffer a defeat. Sterling Price was tasked with attacking the small town of Iuka, a “critical supply depot and railroad junction near Corinth in northeast Mississippi.” Price’s objective was to fool Grant into thinking that the Confederates were about to invade Tennessee. Having seized his rival, Johnston knew Grant would not remain on the defense but immediately seize the opportunity to destroy Price. To assure his success, Johnston also ordered Van Dorn to move against Corinth, whose great importance meant that Grant could not neglect its defense. Indeed, as soon as he heard of Iuka’s capture and that Corinth was being threatened, Grant sent Generals Ord and Rosecrans to face Price and Van Dorn respectively, Rosecrans, naturally, commanding the bigger force.

Price's raid was mostly cavalry bolstered by blood-thirsty partisans. Recruited to the call of "Come boys! Who wants to kill some Yankees?", these partisans had been sowing terror and devastation throughout Mississippi and Tennessee for many months. Their targets were not simply military anymore. Believing their very existence to be threatened by their foe, they engaged in a bloody campaign of destruction that murdered not only Union soldiers, but routinely razed the farms of Unionists or other people who didn't show, in their estimation, enough resistance to the Yankees. Their common modus operandi was to enter a city, murder all Union soldiers or militia, and then gather the people. Anybody who didn't pledge loyalty to the Confederacy and hate of the Union would be murdered in cold blood with spikes, so as to save ammunition. Lies were not a guarantee of safety, for the rebels oftentimes returned to punish those who had broken their pledges to resist the Union at all costs. Sometimes, the raiders would show the Confederate conscription law and kidnap youths to serve with them - anybody that refused, of course, "had his heart pierced like the abolitionist dog he was".

Negroes suffered the most, for they were presumed to be Unionist by default. Even those who had remained enslaved were sometimes whipped as a reminder; those who had acquired their freedom were enslaved again and punished severely, or simply massacred - "ain't no use for a nigger who likes freedom", the raiders would declare. During the course of the campaign, some of the contraband camps Eaton had established were burned to the ground, all of the freedmen massacred. One soldier would later testify to an appalling scene of carnage, where one such camp was attacked: The militia protecting the camp was driven in pursuit of these marauders, but then suddenly a much larger group appeared and gave no quarter. The men who surrendered had their throats slit. They then entered the camp and engaged in their vilest instincts, ravishing several Black women and even girls, burning alive or cutting the tongues or extremities of many contrabands, and then fleeing with at least twenty captives when a Union force finally approached.

Rosecrans would have to face these kind of murderers, while Ord's secondary force was sent to Corinth. Rebel cavalrymen quickly advised Johnston, who had his reserved ready. While Rosecrans deflected Van Dorn's attacks with some ease, Johnston and his reserved quickly advanced, boolstering Price's force to 21,000, double the 10,000 bluecoats Ord had brought. The Union commander was surprised by the sudden arrival of another rebel command, which immediately advanced with murderous fury. Unfortunately for the rebels, lack of communications and coordination allowed Ord to escape destruction through a small gap in the Southern line, but his force had been badly bloodied, losing 4,000 men. At Corinth, Van Dorn simply left as soon as a courier told him of the results of the struggle, and an attempt to pursue them was called off by Grant, who wanted to keep Rosecrans around Corinth should Iuka just be the prelude of a larger assault.

In the great scheme, the Battle of Iuka was not of great importance. Grant convinced himself that Price was preparing for an invasion of Tennessee, which he believed would be disastrous, and that the Battle of Iuka was thus a victory. The rebels too failed in their goal of destroying part of the Union Army, but they at least inflicted a painful and humiliating defeat on their adversaries. Perhaps the most important consequence of Iuka was that it sowed seeds of discontent between Rosecrans and Grant. Grant considered Rosecrans, a fellow West Pointer nicknamed “Old Rosy” by troops who appreciated his jovial behavior, a “fine fellow”, but was disappointed by what he saw as lack of initiative.

Rosecrans for his part bitterly resented what he saw as unjust treatment, though events in the future would show that he indeed was slow to prepare and reluctant to fight despite at the same time possessing an enormous courage. McPherson aptly describes him as “a study in paradox”, though in the case of Iuka it seems that Old Rosy was not to fault, for he had performed well. Rosecrans, too, believed that calling off his pursuit was a mistake, and the press freely criticised Grant for it. Seizing on this, Rosecrans and his allies quickly exploited the press for his benefit, secretly planting malicious articles that depicted himself as a hero and Grant as a failure, especially magnifying the importance of Van Dorn's distraction (it's worth noting that whether Rosecrans himself also participated is contested). Rosecrans achieved greater success in the second rebel “hit and run.”

Price had not been satisfied by Iuka, believing that such tactics were simple cowardice and that the Confederates ought to invade Tennessee. Breckenridge still forbid an invasion, so Price settled for attacking Corinth in the hopes of retaking it. Johnston allowed him to proceed, secretly hoping that failure would allow him to get rid of Price who was more of a hindrance than anything. Johnston did admire Price’s will and courage, but he thought of him as reckless and insubordinate, and that although Price had the right offensive mindset, he needed to be more responsible and practical. In October, Price and Van Dorn joined for an attack on Corinth, in a day with a blazing sun. This battle “of short duration but unusual savagery” featured Rosecrans at his best, as he rallied back the men with courage and decisiveness. By the end of the day, Rosecrans’ “clothing was sprinkled with blood and pocked with bullet holes”. The following day, he led a counterattack that sent the rebels fleeing, having lost 5,000 men, double the Federal casualties.

It’s a shame that Rosecrans did not show the same capacity in the aftermath of the battle, where, instead of pursuing Price, he dithered for some fifteen hours before finally settling on a half-hearted pursuit that saw him take the wrong road. Grant was by then completely disillusioned with Rosecrans, whom he believed to lack assertiveness and decision. Rosecrans, a man who “didn’t take well to direction and always fancied himself in command”, was also against Grant. Rosecrans felt that Grant had not praised him enough for his heroic performance, and resented having to serve under him instead of commanding his own army. As almost all of Grant’s enemies did, Rosecrans levied accusations of drunkenness against Grant, claiming that he was “beastly intoxicated” after an afternoon of “drinking fine whisky and puffing on cigars” while Rosecrans saved the day at Corinth.

The Second Battle of Corinth is occasionally known as the Third Battle, if the siege of Corinth is taken into account. However, since Johnston abandoned Corinth and only gave battle at Kings Creek, the siege is not usually considered a battle.

Grant was usually not a man to conspire, but he was so annoyed by Rosecrans’ behavior that he consulted with Lyon to see if it was possible to send Rosecrans elsewhere. Lyon, of course, sided with Grant, but he had no power to simply remove Rosecrans from command. An attempt to send him to East Tennessee was apparently blocked by Halleck, though the General in-chief would later disclaim any responsibility and say that events in East Tennessee were the main reasons the transfer was not possible. For better or worse, Rosecrans was to remain in the Army of the Tennessee. Johnston was more successful when it came to getting rid of his troublesome officers, as Price was exiled to the trans-Mississippi after Breckenridge found out about the Second Battle of Corinth. Van Dorn was similarly disgraced, one Southern politician saying of him that “He is regarded as the source of all our woes . . . The atmosphere is dense with horrid narratives of his negligence, whoring, and drunkenness.” The battle thus confirmed Johnston as the supreme Confederate commander in the West.

After Second Corinth, Grant started his first campaign against Vicksburg, marching down the Mississippi Railroad Central to Grenada and then to Holly Springs, finally arriving at Oxford on December. At that point, news of Lee’s victory over the Army of the Susquehanna were reaching the West, putting pressure on Grant’s Yankees and increasing the morale of Johnston’s rebels. After getting rid of Price and Van Dorn, Johnston had reorganized his army with the intend of keeping Vicksburg at all costs. John Pemberton, a Yankee who sided with the South after marrying a Georgia lady, would be placed in command at Vicksburg, while Johnston and the rest of the Army camped outside. The rebels were ready to resist Grant’s new advance, knowing that losing Vicksburg would be a defeat from which the Confederacy may not recover.

However, if Grant already faced difficulties at Memphis and Corinth, he was now deep in the heart of the Confederacy in “an island surrounded by a sea of fire, the enemy in front and rear, opposing progress,” as Rawlins described it. The Army of the Tennessee’s logistical situation worsened as they were forced to subsist on supplies brought by railroads continuously attacked by rebel partisans. Sherman would denounce railroads as “the weakest things in war”, for "a single man with a match can destroy and cut off communications." The Ohioan predicted that any "railroad running through a country where every house is a nest of secret, bitter enemies" would suffer "bridges and water-tanks burned, trains fired into, track torn up". That’s exactly what happened to the railroads on which the Federals depended, thanks to the talents of Forrest.

With only 2,000 cavalrymen, Forrest “outfought, outmaneuvered, or outbluffed several Union garrisons and cavalry detachments while tearing up fifty miles of railroad and telegraph line, capturing or destroying great quantities of equipment, and inflicting 2,000 Union casualties.” For good measure, he engaged in much the same kind of depravity as other Confederates, murdering Blacks, Union troops and officers, and Unionists. These events put in peril Grant’s plans for an attack on Vicksburg, which entailed Sherman assaulting the citadel from Chickasaw Bayou to the north while Grant marched to Jackson and Potter bombarded the city from the river. Sherman was so confident that he even boasted that he would be at Vicksburg before Christmas. But Grant’s advance was delayed by Forrest’s campaign, and also by reports that Van Dorn was about to attack their supply base at Holly Springs. These reports were false, for Van Dorn had been shot death by a jealous husband, but they still made Grant pause. When Forrest seized this chance and cut the telegraph wires that had allowed Grant and Sherman to communicate, both commanders ended up isolated from each other, neither knowing the result of their respective engagements.

Sherman paid dearly for this. When he reached Chickasaw Bayou, he confronted the enemy as ordered, but without reinforcements or adequate supply his frontal assault failed quite easily as the rebels simply shot down from the high bluffs of Vicksburg. The Yankee soldiers, tired after wandering through a pestilential swamp to reach the Bayou, were unable to put up much of a resistance. The Union Army, “mowed down by a storm of shells, grape and canister, and minié-balls which swept our front like a hurricane of fire”, finally retreating after receiving 2,500 casualties to the Confederates’ 300. “Our lost has been heavy, and we accomplished nothing”, admitted a sullen Sherman, at the same time that Grant was wiring Philadelphia “that news from the South that Vicksburg has fallen is correct.” Thanks to Forrest, he had no way of communicating with Sherman and learning of this reverse, so he continued his march to Jackson.

This was exactly the opportunity Johnston had been waiting for. Patrick Cleburne, one of the finest Confederate officers on the West, would spearhead the attack with his division. On January 2nd, two days after Sherman had failed at Chickasaw Bayou, Grant was attacked at Canton. A marshy area of forests with small lagoons, Canton served as an important supply depot. By that time, Grant’s perilous supply lines had been cut and he was running low on food and water. The attack at Canton could not come at a worst time. Grant was not surprised by the attack, though he did wonder how Johnston had been able to concentrate such a large force when Sherman was supposedly about to take Vicksburg. In any case, Grant, true to form, decided to give battle, though his tired troops could not equal the elan of Cleburne’s screaming rebels.

By that point both Grant and Johnston had developed enormous respect for each other. Having battled constantly since Dover, Grant recognized Johnston as a fine soldier, while Johnston saw Grant as a commander of great capacity. Neither was intimidated by the other, but a sense of mutual respect between rivals of equal standing had been forged. The Battle of Canton showed this, as both commanders personally went to the front to rally their troops and direct counterattacks. By the end of the day, “only a direct act of Providence could explain the survival of the General”, commented one Confederate who observed how “a hellish whirlwind of bullets” grazed Johnston without him paying any attention. Grant was similarly brave, but unlike Johnston he paid the price as he had a horse shot down from under him and fell, injuring his leg. Paying no mind to this injury, Grant continued to direct his men for one day more, despite the numerical superiority of the rebels (Pemberton commanded just a skeleton force at Vicksburg) and his supply problems.

The troops that showed their greatest bravery at Canton were Grant’s new Black recruits. Though at first Grant judged that were unprepared to actually face the rebels on the field of battle, instead simply wanting to use them to protect his rear and build fortifications. But the furious rebel assault forced Grant to put all men, including his Black men, into battle. Inadequately trained and equipped, the men nonetheless fought desperately. The First Kansas Infantry, the only unit with actual combat experience, even managed to beat back a Confederate attack, allowing their White comrades to escape. This even though they well knew that the Southerners “were perfectly exasperated at the idea of negroes opposed to them & rushed at them like so many devils”, like a North Carolinian described. Indeed, the U.S. Colored Infantry would have many of its men butchered by Confederates who thought "that slaves have no right to surrender". The intervention of the Black troops at Canton helped to prevent a complete defeat, and in the aftermath Grant and his White troops avowed admiration at their manly sacrifice. Unfortunately, it was not enough to turn the tide of battle, and Grant had to retreat on the second day.

More timid Southerners may have been willing to let their enemies escape, but Johnston was anything but timid. He immediately rallied his men to pursue Grant, who “despite my lame status”, still had fight in him. Johnston caught up with Grant at Vaughan Creek, and started a series of fiery assaults. Aside from many soldiers on both sides, these assaults also resulted in the lost of General William J. Hardee, a casualty that allowed “the gallant Cleburne” to be promoted to Lieutenant General following the battle. Grant’s bluecoats did their best to throw back this attack, but they were tired and thirsty, and, moreover, their aggressive commander felt out of place in the defense. Grant still performed admirably, and at the end both Canton and Vaughan Creek are considered tactical draws. But they certainly were strategic losses, and Grant and his army would have to flee back to Oxford, where he and Sherman finally reunited after a couple of weeks without any communications at all.

Grant would forever regret his First Vicksburg Campaign, terming it “the most disgraceful affair” in his department, and saying that among all his military campaigns, that was the only one he saw as an embarrassment. This failure was not without its lessons, as Grant’s hungry Federals learned, like Napoleon’s soldiers had decades ago, to live off the land. Grant was "amazed at the quantity of supplies the country afforded. It showed that we could have subsisted off the country for two months.” This was no exaggeration, for the Union soldiers returned from their forays with entire wagons “loaded with ham, corn, peas, beans, potatoes, and poultry.” This valuable lesson would be important for future military movements, but it did little to soothe the humiliation the Army of the Tennessee felt. He also made good of his threats, and in his way back many Confederate sympathizers would be arrested, including many wives, and caught partisans were hanged immediately. Secesh farms from which these partisans derived their livehood would be sacked for food, and then torched. For their part, Johnston and his soldiers celebrated jubilantly, having lost only 9,500 men to Grant’s 13,000 in the entire campaign. One Southern journalist described the scene in Grant’s captured campgrounds at Canton: “tents burning, torches flaming, Confederates shouting, guns popping, sabres clanking, abolitionists and niggers begging for mercy.”

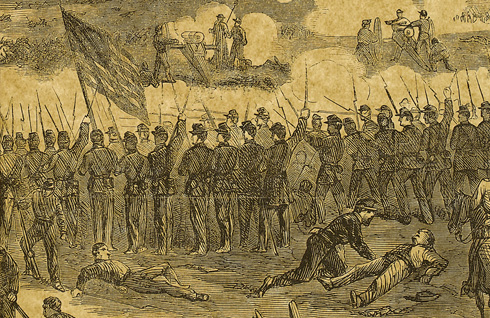

The Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

Grant was not the only Western Union commander to meet with bitter failure in those tragic months that one Northern justly pronounced “the Valley Forge of the present war.” General Buell, tasked with liberating East Tennessee, advanced at a “glacial pace” that did much to strain Lincoln’s nerves and patience. Despite Halleck’s continuous demands to make haste and take Chattanooga, Buell took no action. Just like how Grant’s campaign was stopped by Forrest, Buell had to deal with his own rebel raider, the Kentucky John Hunt Morgan. However, Buell is also to blame for his "apparent want of energy and activity”, for the General was not conciliated to a war for Emancipation that sought to destroy the enemy’s resources and will. Widely denounced as a “McClellanite”, Buell did not have the standing or the influence to protect himself from the administration’s ire.

By October, 1862, Lincoln’s patience had finally run out. Newspapers kept criticizing him for his “weakness, irresolution, and want of moral courage,” that made him retain “traitors such as Buell” in position of command. By that point Lincoln’s political position seemed assured, as McClellan seemed about to take Richmond and Republicans were scoring overwhelming victories in state elections. Halleck did attempt to convince Lincoln to give Buell another chance, but Lincoln paid no heed to his advice. “The Government seems determined to apply the guillotine to all unsuccessful generals”, observed Halleck of the event. “Perhaps with us now, as in the French Revolution, some harsh measures are required.” In October 15th, 1862, the President made Buell the first casualty of this military guillotine, appointing George H. Thomas as the new commander of this Army of the Ohio. McClellan and Halleck himself would also fall prey to the guillotine, but that laid in the future.

Though the fact that Thomas was more capable of Buell cannot be denied, he was not the adequate choice if Lincoln wanted a general that would readily jump into action. His nickname of “Old Slow-Trot”, gained because of a “spinal injury that forced him to gallop slowly”, described his generalship as well. Ron Chernow says that “thorough in preparation for battle, dogged on defense, Thomas swung into action reluctantly.” In later years, Grant succinctly described him as “too slow to move, and too brave to run away.” In the two months after he took command of the Army of the Ohio, Thomas spent most of his time preparing meticulously for an all-out assault in Chattanooga. Fortunately for the loyal Virginian, the rebels took action that shed light on Thomas’ virtues. This unintentional help came from Braxton Bragg.

Bragg had been one of Johnston’s aggressive commanders, and he had insisted on going on the offensive in Kentucky. He believed that “Kentuckians were ready to throw out the iron boot of the Lincolnite minions”, especially now that the “abolitionist proclamation” had made the objective of the war clear. Secretary of War Davis supported the movement, but Breckenridge was cautious. He knew the temperament of the people of his state, and a hasty invasion had already caused much damage. Military men and politicians knew how touchy the subject was to the President – he had almost exiled Leonidas Polk to the trans-Mississippi for his mistake of invading Kentucky, thus, in Breckenridge’s mind, ceding his home state to the Union. Polk had narrowly avoided this fate, but the fact remained that the President did not like him and was unlikely to aid generals with similar foolhardly ideas. The farthest Breckenridge was willing to go was allowing Bragg to take some reinforcements to Tennessee, where he also took command of the troops under General Kirby Smith.

Breckenridge changed his opinion after Lee’s victory over McClellan at the Nine Days. Now euphoric and desirous of more victories, he allowed Bragg to go forward with his plan of invading Kentucky. Davis was charged with putting this into execution, and he faithfully obliged by instructing Bragg to cooperate with Kirby Smith and “march rapidly on Nashville”, so that “Grant will be compelled to retire to the [Mississippi] river, abandoning Middle and [West] Tennessee. . . . You may have a complete conquest over the enemy, involving the liberation of Tennessee and Kentucky.” Confederate prospects seemed especially high after Johnston had achieved victories over Grant at Canton and Vaugh’s Creek. Bragg was so optimist that he went into Kentucky with 15,000 additional rifles, to equip the Kentuckians who would supposedly flock to his banners.

Bragg was probably not the most inspired choice for this winter campaign. A “short-tempered and quarrelsome” man who suffered from migraines and ulcers that did nothing to help his temper, Bragg was heartily disliked by his own troops and officers. His ruthless enforcement of discipline did much to whip his soldiers up to combat readiness, and although it was enough to earn their obedience, "not a single soldier in the whole army ever loved or respected him” according to one of his men. His relationship with his own government was also a problem. “I would make any sacrifice to support you and your gallant command”, Breckenridge assured Bragg at first, but as the war developed and Bragg’s bad attributes came to the forefront, their relationship soured. Bragg, whose “psychological instability made him mortally afraid of error, and of blame for error”, would too readily criticize Breckenridge for all that went wrong, saying that Breckenridge’s failure “to carry out his part of my program has seriously embarrassed me, and moreover the whole campaign."

Despite these problems, Bragg’s campaign got off to an auspicious start. In December 15th, Kirby Smith captured Richmond, Kentucky, just 75 miles South of Cincinnati “whose residents were startled into near panic by the approach of the rebels”, brushing aside a small Union force. Lexington was next, and the Confederates were prepared to inaugurate a Confederate governor. Both Bragg and Breckenridge issued their own declarations, Bragg telling the Kentuckians that he came “to restore to you the liberties of which you have been deprived by a cruel and relentless foe” and inviting them to “cheer us with the smiles of your women and lend your willing hands to secure you in your heritage of liberty”. Breckenridge was more sober, simply declaring that the Confederacy “has no design of conquest or any other purpose than to secure peace and the abandonment by the United States of its pretensions to govern [our] people” and inviting Kentucky to “secure immunity from the desolating effects of warfare on the soil of the State by a separate treaty of peace.”

Some 7,000 Kentuckians answered to the Southern call. Apparently, this was a direct reaction to the late Confederate successes and the Emancipation Proclamation, for Kentucky, although excepted, were now terrified by the prospect of slave emancipation and Negro equality. The number was somewhat disappointing, for Bragg had expected double the men, but it was still a welcome addition to his 30,000 rebels, bringing Bragg’s total strength to 37,000, Thomas had some 50,000 with him, his request for reinforcements from Grant unfulfilled thanks to the failure of the first Vicksburg campaign. Moreover, almost a third of his numbers were raw recruits. Though Bragg elatedly boasted to his wife that "We have made the most extraordinary campaign in military history”, he had not defeated Thomas’ bluecoats yet.

The stoic Federal was not going down easily, though there was a lot of criticism coming from Philadelphia. Secretary of War Stanton complained that “Thomas seems unwilling to attack because it is ‘hazardous,’ as if all war was anything but hazardous. If he cedes the initiative to Bragg, Gabriel will be blowing his last horn.” But if Thomas’ preparations took long, the results were worth it, and in January 23rd, Thomas hit Bragg and Kirby Smith at Lexington with the force of a sledgehammer. A titanic struggle resulted, as the cool Thomas attacked relentlessly while Bragg and his men floundered under disagreements. On the Confederate side, the insubordinate and egocentric Felix Zollicoffer was particularly conspicuous, and the rebels also suffered by the animosity between Kirby Smith and Bragg. On the Union side, Philipp Sheridan, a man who had quickly raised through the ranks thanks to his innate talent, achieved distinction in the battle. Before long, Bragg was forced to retreat, having suffered some 5,000 casualties to Thomas’ 3,000.

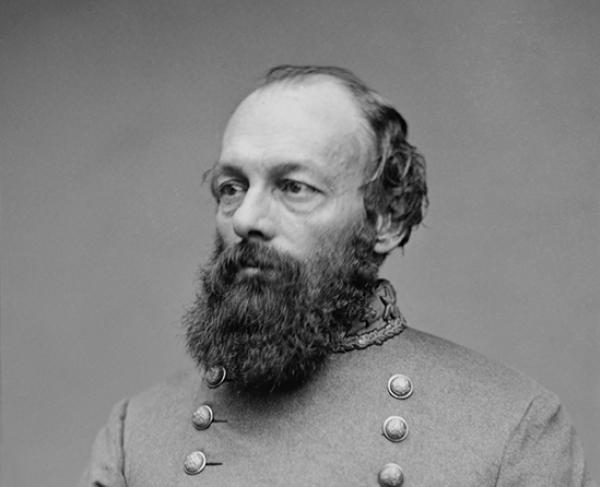

George "Sledgehammer" Thomas leading his troops

As he retreated, the Kentuckians Bragg had recruited simply melted away, unwilling to fight for a loser and even more unwilling to leave the Bluegrass state. Bragg almost immediately gave in to extreme bitterness towards the Kentuckians, whom he characterized as ungrateful men who “have too many fat cattle and are too well off to fight”, and saying that the lack of support forced him to “abandon the garden spot of Kentucky to its own cupidity.” Unfortunately for Bragg, Thomas was not one to rest on his laurels and he followed his victory at Lexington with another devastating attack at White Lily near the Laurel River. Bragg this time put up more stout resistance, and the winter weather that had forced Thomas to abandon his East Tennessee campaign in 1861 once again delayed him. A desperate two-day battle left both armies thirsty and exhausted, the Confederates having lost an additional 5,000 while the Yankees suffered just 4,000 men.

Finally, on February 17th, Bragg returned to Tennessee, all his officers bickering and throwing the blame for the failure around. Unfortunately for them, this took them into the very heart of Unionism in the state, to the midst of a population that resented the Confederacy and cheered the recent Federal triumph. The oppression of the pro-Union population by the Confederate authorities had been swift and ruthless, the Breckinridge regime, either by action or inaction, allowing soldiers and guerrillas to freely terrorize those who resisted the government. But harsh methods were rather unsuccessful, and incidents of bridge burning, sabotage and even murder continued. "The whole country is now in a state of rebellion", a Confederate colonel reported, while a member of Bragg's staff said in despair that East Tennessee was "more difficult to operate in than the country of an acknowledged enemy." Historian Bruce Levine estimates that the East Tennessee dissidents forced Richmond to keep four to five thousand men in the area just to prevent open insurrection.

These were the temperament and loyalty of the people of East Tennessee when Bragg's battered army arrived following its shellacking at Lexington and White Lilly around March. The Unionist population of Knoxville received the weary Confederates with hisses and glares, and when Bragg called on them to give his men food and rest no one came forward. Worse than mere rudeness, there were reports that several Unionists planned an insurrection to deliver the city to Thomas' pursuing bluejackets. An irate Bragg, true to character, reacted by requisitioning goods from the struggling civilians and cracking down on all suspected Unionism, actions that could hardly have won the hearts and minds of the city's population. When in just a few days news came of Thomas' imminent arrival, Bragg ordered everything of military value torched and fled to Chattanooga.

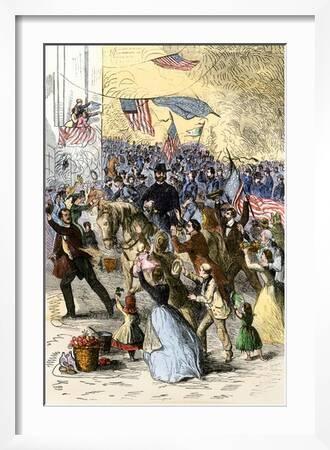

On April, Union forces entered the city, the dashing bluejackets putting down the fires and offering food and blankets, and, more importantly, deliverance from rebel rule. Colonel Foster reported from Knoxville that “Men, women, and children rushed to the streets". The women “shouting, ‘Glory! Glory!’ ‘The Lord be praised!’ ‘Our Savior’s come!’", the men "huzzahed and yelled like madmen, and in their profusion of greetings I was almost pulled from my horse", and throughout the city "the streets resounded with yells, and cheers for the ‘Union’ and ‘Lincoln.’" General Joseph J. Reynolds was amazed when a group of Unionists, hidden in the mountains from the rebel authorities, saw his forces and “joined our column, expressing the greatest delight at our coming, and at beholding again what they emphatically called ‘our flag.’"

The Union Army liberating Knoxville

By the end of the month, Chattanooga was also in peril of falling into Yankee hands. Union cavalry units had raided behind Bragg's position, threatening to cut him off from his lifeline to Atlanta, and the in-fighting had gotten even worse. Confessing the campaign "a great disaster", Bragg nonetheless focused more on his struggle against his commanders. Rumors of his imminent removal circulated freely, and in Richmond only the influence of Secretary of War Davis managed to convince Breckinridge to keep Bragg for the moment, if only just until a suitable replacement had been found. The President hoped that Bragg could hold onto Chattanooga until the new commander arrived, but a panicky Bragg decided to evacuate the city. "What does he fight battles for?", questioned a furious Forrest, while a Confederate official asked in despair "When will the calamities end!"

Shortly after the hasty and chaotic evacuation, Thomas moved into Chattanooga, thus liberating East Tennessee. But this city had also been devastated by the Southerners themselves . Afraid of suffering vengeance at the hands of the Union, the residents of these two cities fled through the snow, resulting in the lamentable "Winter Exile" that saw many perish to the elements, Bragg and his troops unable to provide any shelter or food, because they themselves were hungry and cold. There are also tales of slaveholders who preferred to murder their slaves rather than allow the Union army to liberate them. Thomas' victories had taken place between the failure at Vicksburg and the disastrous defeat at Manassas, and since the Virginian had achieved one of Lincoln's most important goals, he was showered with praise by the Northern press and government. Bragg, on the other hand, received no mercy. Summoned to Richmond to explain his failure, Bragg was dismissed by an irate Breckenridge, who lamented Bragg's invasion of his own home state and how he had lost almost all of Tennessee.

Secretary of War Davis tried to defend Bragg, who had been a personal friend since their days as comrades in the Mexican War. “You have the misfortune of being regarded as my personal friend,” Davis wrote to Bragg, “and are pursued therefore with malignant censure, by men incapable of conceiving that you are trusted because of your known fitness for command.” But Breckenridge did not buy these arguments. Furthermore, the President was lobbied by Kentuckians at Richmond and Bragg’s own commanders, all of whom placed the blame squarely on him. In any case, Breckenridge had decided to reorganize the army departments in order to better resist the Yankee advance.

Virginia would obviously go to Lee, while A. S. Johnston’s Department of the Mississippi was fused with the Trans-Mississippi, so that Vicksburg could be defended more easily. In the middle, a new Department of the Midwest was created to resist Union incursions into Tennessee. But who was to command this department? Breckenridge was not impressed by Kirby Smith either, and he faced a political risk in the form of Joe Johnston, who was growing increasingly bitter after being removed from command. Beauregard had already formed a powerful anti-administration faction around himself, and it would not do to antagonize Johnston needlessly. Even if “Uncle Joe” did not really want this command, at least it would get him far from Richmond.

The Battle of White Lily

Despite the Kentucky fiasco, the winter of 1862-1863 was definitely the high-water mark of the Confederacy, with one arguable draw, one clear-cut victory, and one enormous triumph over the Union forces. Breckenridge in Richmond was said to be rejuvenated, and the Confederate cause as a whole was strengthened tenfold, as jubilant rebels saw their prospects raise. Foreign recognition, outright military victory, and other possibilities now seemed open. February gave way to March and Lee set forth in a daring invasion of the North, the Confederates expecting it to be the final and most decisive strike for their independence.