Guys this isn't a TL about the 1988 election this is a TL about a collapse of Mexico in the late 20th century. @Roberto El Rey just tell us how the election goes so we can be done with this discussion.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Al Grito de Guerra: the Second Mexican Revolution

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special AnnouncementThis is for 1996, but the US Marine Corps Summary of Mexico, linked here has a lot of stuff you might find useful for your TL

1996 breakdown on Page 298 is 130,000 in Army, 8,000 in Air Force, 37,000 in Navy (inc. Marines) for 175,000 total. Army is 70,000 regulars, 60,000 conscripts. Supposedly they have 300,000 Reserves, but this is a Manpower pool and there is no info on training status, probably untrained and certainly not mobilizeable on short notice. Using the ratio of 1.9 Soldiers per 1000 people, that Mexico had been fairly constant in keeping since the 70's, extrapolating same ratio Army/Navy/AF, ~116,000, ~33,000, ~7,000

Eyeballing it, would say they could get 20,000 men in overnight, maybe. Moving troops takes time, if they had a plan and rehearsed it they could get rather more troops into the capital, but not sure if they did that

Thanks, this is a great help! I'll change the number accordingly: say 18,500 troops to start, but over the following couple of weeks, reservists will be called up and more troops will be mobilized to occupy the capital. I've assumed that there are no special contingency plans for occupying an entire city (there's no particular reason for them to exist, because in the twenty years between 1968 and 1988 the Mexican Army never had to occupy an entire city for extended amounts of time) which contributes heavily to the lack of discipline and coordination among the soldiers and officers.

Last edited:

RamscoopRaider

Donor

You'd be amazed what sort of contingency plans exist, the US has plans to deal with an uprising by the Girl Scouts. So the Mexican Army having a plan to rush a bunch of troops into Ciudad Mexico is not surprising, it's them practicing it that would beThanks, this is a great help! I'll change the number accordingly: say 18,500 troops to start, but over the following couple of weeks, reservists will be called up and more troops will be mobilized to occupy the capital. I've assumed that there are no special contingency plans for occupying an entire city (there's no particular reason for them to exist, because in the twenty years between they never had to occupy an entire city for extended amounts of time) which contributes heavily to the lack of discipline and coordination among the soldiers and officers.

Also just found out ~40% of the Mexican military is based near Ciudad Mexico, so having 40,000 troops show up overnight is not impossible. Given how the Reserves are mentioned as a manpower pool rather than extant formations, it might be more than a few weeks to get mobilized

Could you share your source for that tidbit too?Also just found out ~40% of the Mexican military is based near Ciudad Mexico, so having 40,000 troops show up overnight is not impossible. Given how the Reserves are mentioned as a manpower pool rather than extant formations, it might be more than a few weeks to get mobilized

As for the contingency plans, that does make some sense, but even if there are specific plans they probably wouldn't be quite as helpful in a situation that doesn't involve taking positions against a defined enemy. During the Mexico City earthquake of 1985, the soldiers that were called into affected areas were reasonably organized (if a bit kleptocratically-minded) but that was only for controlling a few neighborhoods. Even the best laid plans would have trouble creating an orderly occupation of an entire huge city. (Keep in mind that this intense reaction to Cárdenas's speech was not expected by the federal government, and the mobilization was done in such a rush that many divisions simply weren't given specific contingency plans.

Well, I don't want to reveal that publicly quite yet, but if anyone doesn't want to wait a week or two to hear about the results of the 1988 election, they can just PM me and I'll happily tell them how it goes.Guys this isn't a TL about the 1988 election this is a TL about a collapse of Mexico in the late 20th century. @Roberto El Rey just tell us how the election goes so we can be done with this discussion.

Last edited:

RamscoopRaider

Donor

That was just Wikipedia page for the Mexican ArmyCould you share your source for that tidbit too?Unless it's in the document you already linked, of course.

As for the contingency plans, that does make some sense, but even if there are specific plans they probably wouldn't be quite as helpful in a situation that doesn't involve taking positions against a defined enemy. During the Mexico City earthquake of 1985, the soldiers that were called into affected areas were reasonably organized (if a bit kleptocratically-minded) but that was only for controlling a few neighborhoods. Even the best laid plans would have trouble creating an orderly occupation of an entire huge city. (Keep in mind that this intense reaction to Cárdenas's speech was not expected by the federal government, and the mobilization was done in such a rush that many divisions simply weren't given specific contingency plans.

These sorts of plans are not really about combat per se, more how do we move so many people and so many tons of supplies in so many vehicles from here to there and in what order, in the least amount of time without causing traffics. It would not necessarily help once they got to Mexico city, but it would help in getting them there. Actually helping them occupy the city would require plans and actual training in occupation duty. Also Mexico does not operate divisional sized forces, they have Brigades and Corps and skip the Division level in terms of ground forces organization

Right, when I said a plan wouldn’t help much that’s what I had in mind.That was just Wikipedia page for the Mexican Army

These sorts of plans are not really about combat per se, more how do we move so many people and so many tons of supplies in so many vehicles from here to there and in what order, in the least amount of time without causing traffics. It would not necessarily help once they got to Mexico city, but it would help in getting them there. Actually helping them occupy the city would require plans and actual training in occupation duty.

Oh, I'll change that. Thanks!Also Mexico does not operate divisional sized forces, they have Brigades and Corps and skip the Division level in terms of ground forces organization

Bookmark1995

Banned

I am wondering if this would mean more refugees to Canada if the US is gonna be not nice about this

They'll have a hell of a way to get there, that's for sure.

They'll have a hell of a way to get there, that's for sure.

Well, they can always leave by planes and overstay via Visas

Bookmark1995

Banned

Well, they can always leave by planes and overstay via Visas

Oh yeah. Because the image of people sneaking through the border is burned into my mind by our current (ahem) political discourse, I forget most people come in by plane.

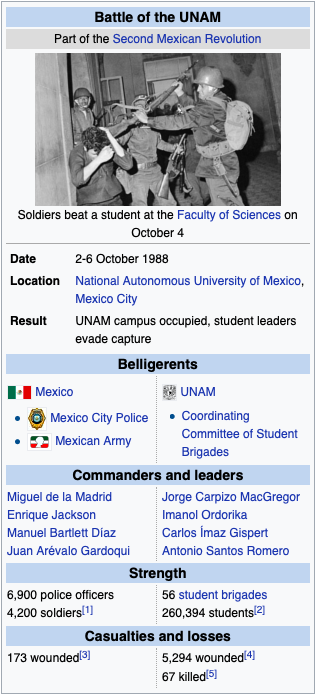

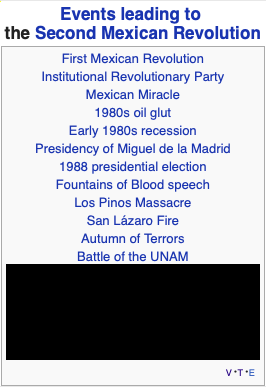

Part 5: The Battle of the UNAM

It has often been said that history repeats itself. It has been said so often, in fact, that the phrase has become one of the stalest clichés in the English language (almost as much as "it has often been said"). After decades of overuse, the expression has lost its edge, like a hatchet gone blunt after felling ten thousand trees. The most tragic effect of this overuse is that the phrase falls short on days when it really counts, when today and yesterday align so perfectly that one can't help but wonder where the one begins and the other ends. One such day was October 2, 1988, when President Miguel de la Madrid ordered military troops to occupy the National Autonomous University of Mexico and arrest over one thousand students—precisely twenty years to the day after the Tlatelolco Massacre of 1968, when President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz had ordered military troops to occupy the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco and murder almost four hundred students.

President Miguel de la Madrid already had an exceptionally troubled relationship with the UNAM (as the National Autonomous University of Mexico was often called). On September 19, 1985, Mexico City had been hit by a massive earthquake that had left 180,000 residents homeless. In response, the students had organized themselves into independent brigades and undertaken valiant rescue efforts, taking control of devastated neighborhoods and making de la Madrid’s government look pathetically incompetent by comparison. The leaders of this upstart, radically left-wing student movement—most prominent among them the President of the Student Council, Imanol Ordorika Sacristán—had stayed politically active over the following three years, serving on all kinds of Committees and Councils to drum up support for Cárdenas in the 1988 Presidential election. [1] And now, as the Autumn of Terrors began in earnest and reports of police brutality swept the city, the students’ civil instincts were triggered once again.

The first Brigada Estudiantil para la Protección Civil (Student Brigade for Civil Protection) was organized on September 19, the three-year anniversary of the Earthquake. It barely took a day for them to start causing trouble; on September 20, a brigada consisting of eleven students from the Faculdad de Ciencias confronted a pair of police officers who were busy shaking down a defenseless civilian. The officers, furious but outnumbered, were forced to let the man go. The next day, the same two policemen, accompanied by an entire platoon of officers, stormed the School of Sciences, arrested twenty-two students (only two of whom had actually taken part in that brigade), and held them without charge or access to legal counsel. On September 22, almost 40,000 students embarked on a disorganized eight-mile protest march from the UNAM campus to the Zócalo, demanding that the government release the abducted students, find Celeste Batel’s killer, and bring the officers responsible for the Los Pinos Massacre to trial. de la Madrid was unmoved and saw little reason to stop the marchers, who, after reaching the Zócalo, quickly realized that there was nothing for them to do and awkwardly dispersed. But, despite a general sense of aimlessness, the students were emboldened by the success of the march, assuming that the President had failed to stop it not because he was unfazed, but because he was too scared to confront them.

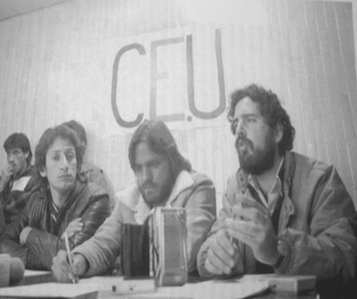

From left to right: Antonio Santos Romero, Carlos Ímaz Gispert, and Imanol Ordorika Sacristán, the most prominent leaders of the student movement at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, shown here chairing a meeting of the UNAM's University Student Council in 1987.

Learning from the disorganized nature of this protest march, the students set up a Coordinadora (Coordinating Committee) to guide the brigadas. Headed by preeminent student leader Imanol Ordorika, the Coordinadora quickly got to work dispatching brigades to certain streets and neighborhoods, establishing clear leadership and self-reliance in every brigade, and outfitting each one with non-deadly weapons and two-way radios. Under the leadership of the Coordinadora, the Brigadas Estudiantiles quickly became models of efficiency and coordination; by the last day of September, over fifty of them had been formed and were challenging the police for effective control of the City’s southern suburbs. Secretary Bartlett wanted to punish the students for defying the authority of the government, but de la Madrid feared that a crackdown would only lead to street battles that would further endanger Mexico’s economic standing. Undeterred, they patrolled the streets, rescuing hundreds of citizens from police abuse. By the end of the week, similar brigades were being set up in the National Polytechnic Institute (Politécnico), Mexico City's second-largest university. And as news of the brigades traveled through word of mouth, the students won public admiration for their bravery and willingness to challenge the government.

When Miguel de la Madrid was informed by moles within the student movement that another march to the Zócalo was being planned for Friday, September 30, he was unconcerned. Over the previous week, he and President-elect Salinas had been so fixated on containing capital flight that they failed to realize how well-organized the students had become. de la Madrid ignored Secretary Bartlett’s pleas to suppress the march, believing that the planned demonstration would just be another small, harmless affair like the previous week. It was only after 190,000 students—80% from the UNAM, 20% from the Politécnico—were joined in the streets by 230,000 citizens, who had been attracted to the protest by a highly successful student-led propaganda campaign, that the President realized his mistake. Army blockades were hastily assembled to block the path of the march, but when the crowds approached the officers simply let them pass through, knowing that attacking hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians with guns could only lead to disaster. Thus, on the last day of September, 420,000 citizens packed themselves into the Zócalo to vent their anger at two weeks of terror and dictatorship.

The Coordinadora had put much preparation into the march, setting up a speaking platform and inviting over a dozen speakers to address the crowd, including Jorge Carpizo MacGregor, Rector of the UNAM and respected jurist, who criticized the PRI's continuous breaking of the law to preserve power; Sergio Aguayo [2], Mexico’s foremost independent human rights activist, who recounted the horror of the Los Pinos Massacre and fired up the crowd with calls for justice; and Rosario Ibarra, a minor candidate in the 1988 presidential election and the mother of a boy who, after joining a communist guerrilla group in the 1970s, had become one of los desaparecidos: the thousands of people who had been arrested by the government and subsequently disappeared, never to been seen again. Ibarra’s speech proved by the far the most inflammatory, because a significant percentage of the protesters had close friends or family members who had been arrested that month. Ibarra’s stories of pain and anguish at the loss of her son terrified tens of thousands of citizens into thinking that they might never see their loved ones again, and her closing note that Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (who had not been seen in public since September 15) might himself become a desaparecido did little to help matters. The authorities looked on helplessly, unable to break up the rally for fear that it would flare up into yet another mass rebellion.

The Zócalo on the afternoon of September 30, 1988, in the midst of a protest rally which dwarfed that held by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas earlier in the month.

But, to the government’s surprise, the protest ended anticlimactically. The students slinked out of the Zócalo as quickly and as efficiently as they had entered, having intended for the protest to be show of civilian strength rather than a flashpoint for revolution. Nevertheless, severe damage had been done. The Coordinadora had had the good sense to invite television crews from NBC and ABC to film the protest, and when foreign investors turned on their television screens to see yet another massive rally in the Zócalo barely two weeks after Cárdenas’s frenzied speech on the 15th, the illusion of government control was shattered. Nearly half a billion dollars fled the country that afternoon, bringing the foreign reserves down to a dangerously low $2.1 billion. de la Madrid, President-elect Salinas, and Finance Secretary Gustavo Petriccioli tried to assure the executives at Bank of America and CitiCorp that the situation was more peaceful than it appeared, but found them impossible to convince. The banks anxiously informed the President that he had until Monday, October 3, to prove that he could keep the peace. If, by that point, Mexico still seemed to be on the brink of civil war, then nearly all foreign investments would stampede out of the country and the economy would almost certainly collapse.

de la Madrid wasted no time. Saturday, October 1 was a whirlwind of hasty military planning and conferencing with President-elect Salinas, Defense Secretary Juan Arévalo Gardoqui, and Government Secretary Bartlett (who exuded quite a bit of smugness after being proven right about the protest). As dawn broke on the twentieth anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre, the first police cars entered the UNAM, hoping to occupy the campus, arrest the leaders of the Coordinadora, and leave without causing much upheaval. What the President and Secretary Bartlett failed to realize was that, in the midst of equipping and organizing dozens of Brigadas, the students had developed a plan for exactly the situation they now found themselves in. The plan wasn’t terribly detailed, mainly consisting of a general call to fight against the occupation forces with whatever weapons were at hand. But in the hyper-alert UNAM of 1988, word traveled at lightning speed, and within an hour the entire student body was mobilized, ready to fight like wild dogs in defense of the cherished “autonomy” of their Autonomous University.

The most disciplined and organized of all the students were the brigadas. They were at the forefront of the defensive campaign, engaging wave after wave of policemen and soldiers in hand-to-hand combat at the outskirts of the campus while students further inside built barriers across the University’s main avenues. Eventually, the brigades were dealt with and the way finally cleared for police cars and Army trucks, only for them to find that many of the paths had been barricaded off, giving them little choice but to clamber around them on foot. The alleyways between residential buildings became gravitational booby traps, as students in fifth-story dormitories poured out garbage cans and pots of boiling water onto the heads of soldiers and policemen below. Police cars left alone for longer than half an hour were set on fire. After a day passed and the campus was still far from pacified, tanks and bulldozers were brought in to push through the barricades, which swiftly came under attack from students hurling Molotov cocktails. [3] Thousands of students sustained injuries, many of them serious, but de la Madrid had ordered that use of deadly force be kept to an absolute minimum, tying the hands of the officers and significantly slowing the progress of the military takeover (though not saving the 14 students who were killed by overly aggressive officers, nor the 53 who would eventually die of their wounds).

Finally, after four days of exhausting skirmishes between 12,000 well-armed officers and 260,000 poorly-armed but fiercely-motivated students, the authorities had essentially subdued the UNAM. They arrested over twelve thousand students, only to find that most of the Coordinadora was gone, having secretly fled the campus in the opening hours of the fight and left Mexico City to go into hiding. de la Madrid was apoplectic, ordering that the most prominent leaders—Ordorika, Santos, and Ímaz—be tracked down and apprehended. But he had little time to focus on his rage because, after it became evident that the student leaders had escaped, capital flight became a stampede as investors lost all their remaining faith in the government's ability to keep order. de la Madrid and Salinas, knowing that the last of the country’s meager foreign reserves would be gone within the week, now turned in desperation to the U.S. government, begging and pleading with President Reagan for a loan that would allow Mexico to partially shield itself from the oncoming financial maelstrom.

Though reviled by investors and the government, these students quickly became international heroes. Accounts of police corruption and Army brutality in Mexico City had spread everywhere from London to La Plata, attracting near-universal condemnation. And when news of the students’ resistance was publicized, the juveniles were celebrated throughout the democratic world as civic exemplars, fearlessly defending their fellow citizens from state tyranny. The question of when exactly the Second Mexican Revolution began remains a topic of fierce contention among historians and academics, but a significant fraction argues that the National Autonomous University of Mexico on October 2 became the first real battleground of the Revolution. The Battle of the UNAM, as many call it, is one of the most romanticized moments in the Mexican revolutionary mythos, and the simultaneous outpouring of rage and sympathy it inspired all across the country ensures that it will stay that way, no matter what verdict history eventually delivers on its significance to the Revolution as a whole.

__________

[1] This happened in OTL, before the POD of this work. Student brigades from the UNAM conducted some truly impressive rescue work of their own initiative in the aftermath of the Earthquake, putting their lives on the line to rescue newborn babies from collapsed maternity wards and maintaining order in areas of the city where law enforcement had broken down. For a detailed description of their heroism, see here.

[2] Remember him. He’ll be important later.

[3] In 1968, the UNAM was occupied by police and military to practically no resistance. But when the Politécnico was occupied days later, the skirmishes lasted three days, and the students used almost all of the outlined methods of fending off the occupiers.

President Miguel de la Madrid already had an exceptionally troubled relationship with the UNAM (as the National Autonomous University of Mexico was often called). On September 19, 1985, Mexico City had been hit by a massive earthquake that had left 180,000 residents homeless. In response, the students had organized themselves into independent brigades and undertaken valiant rescue efforts, taking control of devastated neighborhoods and making de la Madrid’s government look pathetically incompetent by comparison. The leaders of this upstart, radically left-wing student movement—most prominent among them the President of the Student Council, Imanol Ordorika Sacristán—had stayed politically active over the following three years, serving on all kinds of Committees and Councils to drum up support for Cárdenas in the 1988 Presidential election. [1] And now, as the Autumn of Terrors began in earnest and reports of police brutality swept the city, the students’ civil instincts were triggered once again.

The first Brigada Estudiantil para la Protección Civil (Student Brigade for Civil Protection) was organized on September 19, the three-year anniversary of the Earthquake. It barely took a day for them to start causing trouble; on September 20, a brigada consisting of eleven students from the Faculdad de Ciencias confronted a pair of police officers who were busy shaking down a defenseless civilian. The officers, furious but outnumbered, were forced to let the man go. The next day, the same two policemen, accompanied by an entire platoon of officers, stormed the School of Sciences, arrested twenty-two students (only two of whom had actually taken part in that brigade), and held them without charge or access to legal counsel. On September 22, almost 40,000 students embarked on a disorganized eight-mile protest march from the UNAM campus to the Zócalo, demanding that the government release the abducted students, find Celeste Batel’s killer, and bring the officers responsible for the Los Pinos Massacre to trial. de la Madrid was unmoved and saw little reason to stop the marchers, who, after reaching the Zócalo, quickly realized that there was nothing for them to do and awkwardly dispersed. But, despite a general sense of aimlessness, the students were emboldened by the success of the march, assuming that the President had failed to stop it not because he was unfazed, but because he was too scared to confront them.

From left to right: Antonio Santos Romero, Carlos Ímaz Gispert, and Imanol Ordorika Sacristán, the most prominent leaders of the student movement at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, shown here chairing a meeting of the UNAM's University Student Council in 1987.

Learning from the disorganized nature of this protest march, the students set up a Coordinadora (Coordinating Committee) to guide the brigadas. Headed by preeminent student leader Imanol Ordorika, the Coordinadora quickly got to work dispatching brigades to certain streets and neighborhoods, establishing clear leadership and self-reliance in every brigade, and outfitting each one with non-deadly weapons and two-way radios. Under the leadership of the Coordinadora, the Brigadas Estudiantiles quickly became models of efficiency and coordination; by the last day of September, over fifty of them had been formed and were challenging the police for effective control of the City’s southern suburbs. Secretary Bartlett wanted to punish the students for defying the authority of the government, but de la Madrid feared that a crackdown would only lead to street battles that would further endanger Mexico’s economic standing. Undeterred, they patrolled the streets, rescuing hundreds of citizens from police abuse. By the end of the week, similar brigades were being set up in the National Polytechnic Institute (Politécnico), Mexico City's second-largest university. And as news of the brigades traveled through word of mouth, the students won public admiration for their bravery and willingness to challenge the government.

When Miguel de la Madrid was informed by moles within the student movement that another march to the Zócalo was being planned for Friday, September 30, he was unconcerned. Over the previous week, he and President-elect Salinas had been so fixated on containing capital flight that they failed to realize how well-organized the students had become. de la Madrid ignored Secretary Bartlett’s pleas to suppress the march, believing that the planned demonstration would just be another small, harmless affair like the previous week. It was only after 190,000 students—80% from the UNAM, 20% from the Politécnico—were joined in the streets by 230,000 citizens, who had been attracted to the protest by a highly successful student-led propaganda campaign, that the President realized his mistake. Army blockades were hastily assembled to block the path of the march, but when the crowds approached the officers simply let them pass through, knowing that attacking hundreds of thousands of unarmed civilians with guns could only lead to disaster. Thus, on the last day of September, 420,000 citizens packed themselves into the Zócalo to vent their anger at two weeks of terror and dictatorship.

The Coordinadora had put much preparation into the march, setting up a speaking platform and inviting over a dozen speakers to address the crowd, including Jorge Carpizo MacGregor, Rector of the UNAM and respected jurist, who criticized the PRI's continuous breaking of the law to preserve power; Sergio Aguayo [2], Mexico’s foremost independent human rights activist, who recounted the horror of the Los Pinos Massacre and fired up the crowd with calls for justice; and Rosario Ibarra, a minor candidate in the 1988 presidential election and the mother of a boy who, after joining a communist guerrilla group in the 1970s, had become one of los desaparecidos: the thousands of people who had been arrested by the government and subsequently disappeared, never to been seen again. Ibarra’s speech proved by the far the most inflammatory, because a significant percentage of the protesters had close friends or family members who had been arrested that month. Ibarra’s stories of pain and anguish at the loss of her son terrified tens of thousands of citizens into thinking that they might never see their loved ones again, and her closing note that Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (who had not been seen in public since September 15) might himself become a desaparecido did little to help matters. The authorities looked on helplessly, unable to break up the rally for fear that it would flare up into yet another mass rebellion.

The Zócalo on the afternoon of September 30, 1988, in the midst of a protest rally which dwarfed that held by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas earlier in the month.

But, to the government’s surprise, the protest ended anticlimactically. The students slinked out of the Zócalo as quickly and as efficiently as they had entered, having intended for the protest to be show of civilian strength rather than a flashpoint for revolution. Nevertheless, severe damage had been done. The Coordinadora had had the good sense to invite television crews from NBC and ABC to film the protest, and when foreign investors turned on their television screens to see yet another massive rally in the Zócalo barely two weeks after Cárdenas’s frenzied speech on the 15th, the illusion of government control was shattered. Nearly half a billion dollars fled the country that afternoon, bringing the foreign reserves down to a dangerously low $2.1 billion. de la Madrid, President-elect Salinas, and Finance Secretary Gustavo Petriccioli tried to assure the executives at Bank of America and CitiCorp that the situation was more peaceful than it appeared, but found them impossible to convince. The banks anxiously informed the President that he had until Monday, October 3, to prove that he could keep the peace. If, by that point, Mexico still seemed to be on the brink of civil war, then nearly all foreign investments would stampede out of the country and the economy would almost certainly collapse.

de la Madrid wasted no time. Saturday, October 1 was a whirlwind of hasty military planning and conferencing with President-elect Salinas, Defense Secretary Juan Arévalo Gardoqui, and Government Secretary Bartlett (who exuded quite a bit of smugness after being proven right about the protest). As dawn broke on the twentieth anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre, the first police cars entered the UNAM, hoping to occupy the campus, arrest the leaders of the Coordinadora, and leave without causing much upheaval. What the President and Secretary Bartlett failed to realize was that, in the midst of equipping and organizing dozens of Brigadas, the students had developed a plan for exactly the situation they now found themselves in. The plan wasn’t terribly detailed, mainly consisting of a general call to fight against the occupation forces with whatever weapons were at hand. But in the hyper-alert UNAM of 1988, word traveled at lightning speed, and within an hour the entire student body was mobilized, ready to fight like wild dogs in defense of the cherished “autonomy” of their Autonomous University.

The most disciplined and organized of all the students were the brigadas. They were at the forefront of the defensive campaign, engaging wave after wave of policemen and soldiers in hand-to-hand combat at the outskirts of the campus while students further inside built barriers across the University’s main avenues. Eventually, the brigades were dealt with and the way finally cleared for police cars and Army trucks, only for them to find that many of the paths had been barricaded off, giving them little choice but to clamber around them on foot. The alleyways between residential buildings became gravitational booby traps, as students in fifth-story dormitories poured out garbage cans and pots of boiling water onto the heads of soldiers and policemen below. Police cars left alone for longer than half an hour were set on fire. After a day passed and the campus was still far from pacified, tanks and bulldozers were brought in to push through the barricades, which swiftly came under attack from students hurling Molotov cocktails. [3] Thousands of students sustained injuries, many of them serious, but de la Madrid had ordered that use of deadly force be kept to an absolute minimum, tying the hands of the officers and significantly slowing the progress of the military takeover (though not saving the 14 students who were killed by overly aggressive officers, nor the 53 who would eventually die of their wounds).

Finally, after four days of exhausting skirmishes between 12,000 well-armed officers and 260,000 poorly-armed but fiercely-motivated students, the authorities had essentially subdued the UNAM. They arrested over twelve thousand students, only to find that most of the Coordinadora was gone, having secretly fled the campus in the opening hours of the fight and left Mexico City to go into hiding. de la Madrid was apoplectic, ordering that the most prominent leaders—Ordorika, Santos, and Ímaz—be tracked down and apprehended. But he had little time to focus on his rage because, after it became evident that the student leaders had escaped, capital flight became a stampede as investors lost all their remaining faith in the government's ability to keep order. de la Madrid and Salinas, knowing that the last of the country’s meager foreign reserves would be gone within the week, now turned in desperation to the U.S. government, begging and pleading with President Reagan for a loan that would allow Mexico to partially shield itself from the oncoming financial maelstrom.

Though reviled by investors and the government, these students quickly became international heroes. Accounts of police corruption and Army brutality in Mexico City had spread everywhere from London to La Plata, attracting near-universal condemnation. And when news of the students’ resistance was publicized, the juveniles were celebrated throughout the democratic world as civic exemplars, fearlessly defending their fellow citizens from state tyranny. The question of when exactly the Second Mexican Revolution began remains a topic of fierce contention among historians and academics, but a significant fraction argues that the National Autonomous University of Mexico on October 2 became the first real battleground of the Revolution. The Battle of the UNAM, as many call it, is one of the most romanticized moments in the Mexican revolutionary mythos, and the simultaneous outpouring of rage and sympathy it inspired all across the country ensures that it will stay that way, no matter what verdict history eventually delivers on its significance to the Revolution as a whole.

__________

[1] This happened in OTL, before the POD of this work. Student brigades from the UNAM conducted some truly impressive rescue work of their own initiative in the aftermath of the Earthquake, putting their lives on the line to rescue newborn babies from collapsed maternity wards and maintaining order in areas of the city where law enforcement had broken down. For a detailed description of their heroism, see here.

[2] Remember him. He’ll be important later.

[3] In 1968, the UNAM was occupied by police and military to practically no resistance. But when the Politécnico was occupied days later, the skirmishes lasted three days, and the students used almost all of the outlined methods of fending off the occupiers.

Last edited:

I’m so happy to have piqued your intrigue! I’ve gained a huge admiration for Mexican culture and history while researching for this timeline, and I hope to honor that history with the struggle I’m about to portray. The next update should be up tonight with luck.

This is where in my imagination Pancho Villa claws himself out of his grave grabs a gun and does what Mexicans of character and real strength of that time did....and then proceed to burn Columbus New Mexico

I'm so incredibly glad you feel this way, and the more people with links to Mexico and its culture I impress with this TL, the more satisfying it will be to write, and the more vindicated I'll feel about the research I've put into it. While I am happy to say that I don't think Cárdenas is underused in alternate history (at least for a non-Anglosphere politician), I also feel like there isn't enough interesting stuff done with this period of Mexican history. Mexico's transition to democracy could have been thrown off course by so many little coin flips—like Donaldo's assassination, the success of the campaign finance reforms of 1997, and of course, Cárdenas's speech in the Zócalo. I was actually inspired to write this TL by the Krauze quote I cited in Part 2, and I'm surprised no one's tried this scenario on here before.

Mexican-American here too and really like this timeline. Also, a sudden war with Guatemala could also be one of those flipped coins......

You know, when I saw the election results last year and saw how pitiful the PRI did, I laughed. Would have laughed harder if AMLO wasn't an idiot with the capacity to do more harm than good. The PRI, in the end, got overthrown and their attempt to remain relevant has been given the response of becoming a minor irrelevant party. Here's looking to an earlier and harsher end to the PRI in TTL. It couldn't happen to a nicer party....okay there were worse parties out there but the PRI still grinds my gears possibly even more than the GOP here in the US.They may even ask what would have happened had Celeste Batel never even been assassinated in the first place...

Oh, you have no idea (yet)!

This song (link the song should start if not, it's at the times stamp of 32:10 called "Se Acabó") mentions communist/socialist revolutionaries. I can provide translated lyrics if you want. It predates the POD but only by a decade or so. It would fit well with the Zapatista rebels and other socialists who would want to get their grimmy hands on the title of Revolution in Mexico. The First Revolution effectively neutralized the communists ability to compete in Mexico, so I am in suspense if this one will do the same. In any event, Mexico did well after the first revolution, can it keep up the trend and do even better after this second one?

What happened to Cardenas? I assume he was arrested after his speech?

Second, was the university that big? 260,000 students?

Second, was the university that big? 260,000 students?

Mexico city is massive (either largest or second largest city in the americas) and so are its facilities.What happened to Cardenas? I assume he was arrested after his speech?

Second, was the university that big? 260,000 students?

Would have laughed harder if AMLO wasn't an idiot with the capacity to do more harm than good.

A Latin American populist doing more harm than good?! Pfffftttttt. You're speaking rubbish.

Latinoamerican populist is just an american whistle for politicians that *gasp* take desitions independently of the embassy! Is like this southern dogs think they are sovereign nations or something!A Latin American populist doing more harm than good?! Pfffftttttt. You're speaking rubbish.

Latinoamerican populist is just an american whistle for politicians that *gasp* take desitions independently of the embassy! Is like this southern dogs think they are sovereign nations or something!

Ummmm …. nope.

Bolsonaro counts as a Latin American populist btw. Don't think he's part of the list you had in mind.

Look at Juan Peron in Argentina, Castro in Cuba and Chavez and Maduro in Venezuela (plus what I predict for Bolsonaro in Brazil and AMLO in Mexico). Not good results. Also, look at Trump and Salvini in the western world, or Duterte in the Philippines. Not good. Populism does not have the best track record.

Bookmark1995

Banned

Ummmm …. nope.

Bolsonaro counts as a Latin American populist btw. Don't think he's part of the list you had in mind.

Look at Juan Peron in Argentina, Castro in Cuba and Chavez and Maduro in Venezuela (plus what I predict for Bolsonaro in Brazil and AMLO in Mexico). Not good results. Also, look at Trump and Salvini in the western world, or Duterte in the Philippines. Not good. Populism does not have the best track record.

Yes, but opposition to these regimes in America has often had little to do with human rights, and more to do with US interests.

Castro's wasn't despised for his human rights violations, but because he confiscated American property.

If Bolsonaro doesn't made noise about "imperialism" then he's OK to many American corporations.

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special Announcement

Share: