That would imply he’s the same person he was in OTL and it’s likely the different experiences have made a bit different.Much as I love the idea of Cisneros as President, I wonder if he’s going to be taken down ITTL the same way he was OTL: payments to a mistress.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Al Grito de Guerra: the Second Mexican Revolution

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special AnnouncementEarlier on in this TL he has a near death experience that makes him change his ways.Much as I love the idea of Cisneros as President, I wonder if he’s going to be taken down ITTL the same way he was OTL: payments to a mistress.

Great update!

You've been laying the seeds for President Cisneros for so long that it's almost cathartic to see it bear fruit. He's a really good choice for this TL, too: beyond the aspect of his heritage, his rise ITTL is a great example of how bit players IOTL could have had their lives and careers go very differently with only a few differences. Not sure I've seen Cisneros used in any TL at all, actually, even list or infobox ones.

And down in Mexico, I love the fracturing of the PAN. It was certainly inevitable, as for the reasons you said: the tent got too big. But alternate party systems are always fun to see, and here it goes a long way in showing just how much Mexico has diverged and changed— not just from the POD but also vis-a-vis its position IOTL. Second revolution indeed!

You've been laying the seeds for President Cisneros for so long that it's almost cathartic to see it bear fruit. He's a really good choice for this TL, too: beyond the aspect of his heritage, his rise ITTL is a great example of how bit players IOTL could have had their lives and careers go very differently with only a few differences. Not sure I've seen Cisneros used in any TL at all, actually, even list or infobox ones.

And down in Mexico, I love the fracturing of the PAN. It was certainly inevitable, as for the reasons you said: the tent got too big. But alternate party systems are always fun to see, and here it goes a long way in showing just how much Mexico has diverged and changed— not just from the POD but also vis-a-vis its position IOTL. Second revolution indeed!

Much as I love the idea of Cisneros as President, I wonder if he’s going to be taken down ITTL the same way he was OTL: payments to a mistress.

Also, it's mentioned in the update that he publicly confessed to his infidelity in 1989, so not only is it a thing of the past but being a "reformed adulterer" is actually part of his image and appeal.Earlier on in this TL he has a near death experience that makes him change his ways.

What is the reaction from Latin America regarding the new democratic regime in Mexico and a Hispanic President in the US?

Bookmark1995

Banned

What is the reaction from Latin America regarding the new democratic regime in Mexico and a Hispanic President in the US?

I'd figure it would be the same reaction Africans had to President Obama: many Latin Americans would be jumping for joy at the election of a Hispanic President.

That would imply he’s the same person he was in OTL and it’s likely the different experiences have made a bit different.

If he presides over an era of calm and economic prosperity like Bill Clinton did, few people would actually care. While most people did believe Clinton was wrong to indulge in his affair, few actually were upset with how he was actually doing as President, and Gore lost because he tried to push Clinton away.

I chalk it up to the different context created by the TL.

ITTL, Salinas' legitimacy is even weaker than it was IOTL because Cardenas has not gone along with the fraud, which has resulted in an agitated and restless populace that has lead protests and strikes against the regime (which have turned violent), as well as garnered international notice and condemnation. Placed in a situation much more precarious than OTL, I don't think it's a stretch to imagine Salinas acting differently.

The reasoning that Roberto gives in the TL makes sense to me: an attempt to keep Raul out of trouble by bringing him into a place where he can't act without impunity. Better to have him inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in, as they say. That it is, perhaps, "too clever by half" I think can be justified either as a desperate effort that Carlos didn't fully think through (it is a stressful time), or an attempt by Carlos to give himself a staunch ally in order to reinforce his legitimacy within the PRI itself, or possibly a combination of the two.

Plus I doubt Salinas thought he'd get assassinated. Raul's biggest perfidies ITTL were only doable because Manuel Bartlett used him as a pawn to control the government before he could be President himself. Carlos basically gave him a position where he couldn't really screw up in, while Bartlett threw him into a position where he could do everything wrong.

These are all good possible reasons as to why Salinas gave his brother a political role ITTL.

So, in general:

He was more desperate and wanted to obtain as much control as possible of the situation that he inherited. Therefore, he couldn't risk allowing Raul Salinas to do whatever he wanted in the alternate circumstances of TTL's 1988.

[3] In OTL, such an explosion did happen. On April 22, 1992, a large amount of gasoline leaked into the Guadalajara sewers and ignited, destroying five miles’ worth of streets, killing over 200 people and gravely wounding a thousand more (Xanic von Bertrab, who was working for a local rag at the time, found out about the leak the day before the explosion, but the authorities didn’t listen to her in time to stop the tragedy). In TTL, the explosion itself has been butterflied away, but the abhorrent safety standards which let it happen have metastasized to Pemex installations in other parts of the country due to the lack of federal oversight.

When you say that the OTL 1992 Guadalajara explosions were butterflied away ITTL, I know it means that it didn't happen.

However, what's your in-universe explanation for it?

Based on what I could find, the pipes were built too close to a gasoline pipeline before the P.O.D. and were poorly designed, including the addition of an inverted siphon that prevented volatile gases from being disposed of properly. Unless someone (like maybe Xanic von Bertrab) notices it and is taken seriously by the authorities (not very likely), the OTL explosions seem to be inevitable due to incompetency.

Source: https://www.aria.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/wp-content/files_mf/FD_3543_guadalajara_1992_ang.pdf

The United States presidential election of 1996 was a foregone conclusion. After sixteen straight years in power, the Republican Party had long overstayed its welcome. The previous eight years had undermined all of the party’s traditional selling points: prudent economic stewardship? Not likely after three years of middling growth rates. Law and order? Not while the drug epidemic raged and inner cities from Harlem to Crenshaw convulsed with crime. Strong international leadership? Not from the party that had fumbled the Gulf War and stood idly by as Mexico slid into dictatorship. President Bush, for his part, did little to help things—the statesmanlike stoicism which had helped him win in 1988 now made him appear out of touch and indifferent, and his whiny insistence that the economy was already recovering rang especially hollow to the many people who were scrounging for jobs or struggling to revive their businesses. The American public showed their antipathy toward the GOP in the 1994 midterms, which saw the Democrats expand their majorities in the House and Senate.

As election year drew closer, Republican voters and politicians alike were tired and demoralized. Just finding a nominee would be a challenge in and of itself, as potential heavy-hitters like Dan Quayle, Dick Lugar, John McCain, and Colin Powell all announced within months of the midterms that they would be sitting out the race. By New Year’s Eve 1995, the Republican field consisted almost entirely of oddballs and misfits: Pat Buchanan, the arch-conservative culture warrior who had harried President Bush in the primaries in 1992; Steve Forbes, businessman and editor of the magazine that bore his name; Bob Dornan, the California congressman best known for loudly accusing his adversaries of homosexuality; and Alan Keyes, a former U.N. official whose two previous attempts at elected office had both ended in landslide defeat. For much of the race, the only halfway “normal” candidate was former Congressman Jack Kemp, who, as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, had taken much of the blame for the dismal situation plaguing American cities. The Republican voter base was thoroughly relieved in early 1996 when the party leadership finally managed to recruit Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, who reluctantly entered the race in January, swept the primaries, and was formally nominated at the convention in Phoenix, choosing Education Secretary-turned-Drug Czar Bill Bennett as his running mate.

The Democratic field grew predictably crowded as various high-profile figures launched their campaigns. Former vice presidential nominee Bob Kerrey threw his hat into the ring, as did senators Al Gore and Tom Harkin and governors Jim Blanchard and Bill Clinton. But deep down, most of the party rank-and-file knew who the nominee would be before he even declared his candidacy. Ever since his election to the Senate in 1990, Henry Cisneros had seemed to speak for America’s voiceless: Hispanic immigrants, inner-city kids, drug addicts, and those who had been left behind by the rising tide of globalization. His legislative work showed that his interest in these groups went beyond empty rhetoric—the Weldon-Cisneros Act, passed in mid-1995, had created a raft of new incentives to dissuade U.S. firms from outsourcing production, saving tens of thousands of industrial jobs and turning the freshman Texas senator into a darling of organized labor. Cisneros had also profited immensely from his opposition to the PRI regime in Mexico. From the very beginning, he had been Manuel Bartlett’s fiercest enemy in Washington, suffering the condescending scorn of those who insisted on supporting the despot as a lesser evil to anarchy or communism. So when the true extent of Bartlett’s corruption was revealed, Cisneros gained a reputation not only as a paragon of moral courage, but also an astute judge of character with a sharp mind for diplomacy. On May 14, 1995, when Cisneros officially launched his presidential campaign before a throng of 40,000 cheering supporters in HemisFair Park in his hometown of San Antonio, one devout listener claimed to the Texas Tribune that the former mayor’s candidacy was divinely ordained.

View attachment 659869

Though Texas state law permitted him to run simultaneously for the Senate and the presidency, Senator Cisneros chose not to run for re-election, instead passing his seat on to another public atoner: Lena Guerrero, whose career had seemingly ended in 1991 when it was revealed she had lied on her resumé, but who made a stunning comeback by riding Cisneros’s coattails to victory over businessman Robert Mosbacher, Jr.

Cisneros’s path to the nomination was not without its obstacles. His opponents criticized him for his relative inexperience, political missteps (such as voting for the ROGUE STATES Act just days after lambasting it), and his personal failings, particularly the extramarital affair to which he had publicly confessed in 1989. But none of the critiques seemed to weigh him down. Years later, David McCullough would write that the youthful senator’s open, unqualified remorse proved an asset, rather than a liability, on the campaign trail—after four years of collective anxiety and insecurities, and with a national ego bruised and battered, the American people hungered not for the picture-perfect candidate with a model family and squeaky-clean past, but for the man who had forsaken his honor, won it back, and carried on through adversity. Henry Cisneros—a reformed adulterer, a father to a son with a horrible heart condition, and a Hispanic who had overcome the stigma of his race to reach high political office—fit the bill just perfectly.

Beyond the candidate’s past, the Cisneros campaign embodied a distinct theme of hope, renewal and change. In contrast to his opponents, most of whom were spouting off the same dry, fiscally-conservative talking points which had kneecapped Paul Tsongas in 1992, Cisneros touted a unique blend of public-sector development and private-sector empowerment dubbed by columnists both friendly and hostile as “business populism”. Pledging to solve America’s many problems by partnering the broad powers of government with the rugged efficiency of business, Cisneros’s platform seemed to resonate with the fickle, suburban moderates who had blocked Democrats’ path to the White House time after time. And unlike Tsongas, whose aggressive appeals to those voters had turned off urban minorities and working-class whites, Cisneros could point to his work in San Antonio, which he’d transformed from a sleepy, decaying city to a vibrant center of growth and culture, as well as his efforts in the Senate to protect industrial jobs, to prove that he was an ally of the blue as well as the white-collar voter. Cisneros clinched a majority of delegates within the first month of the primaries and was crowned to plentiful fanfare at the convention in Louisville. His choice of running mate, House Speaker Dick Gephardt, drew concerns about his lack of charisma, but Gephardt’s solid support from organized labor, as well as Cisneros’s own vast personal charms, put paid to those fears.

As the conventions gave way to full-on campaign season, some Democratic analysts worried Cisneros would look inexperienced next to the accomplished statesman Dole. But these fears were unfounded. In the debates, the septuagenarian Republican seemed tired and supercilious while the scion of San Antonio was enthusiastic and passionate. Nor were Cisneros’s strengths solely cosmetic: When Senator Dole attacked Cisneros’s plan to forgive most of Mexico’s debt, Senator Cisneros made a persuasive case that debt amnesty was necessary to restore stability and prosperity to Mexico and cut down on illegal immigration. While a lethargic Dole invoked high urban crime rates to frighten rural and suburban whites (a Nixonesque strategy which may indeed have helped him win a state or two), Cisneros placed himself above petty racial rivalries and promised to fundamentally reconstruct the American city while delivering solutions for all Americans. While Dole defended the tough-on-crime laws which had put hundreds of thousands of nonviolent offenders behind bars while utterly failing to solve the drug crisis, Cisneros expressed compassion for drug addicts and pledged to treat them not as criminals, but as victims. Vice presidential nominee Bill Bennett, whom Dole had chosen to add credibility on the drug issue, instead drew strident criticism for his part in allowing the crisis to spiral out of control.

On election day, the question was not whether or not Cisneros would win but how big of a margin he would win by. The answer, as it turned out, was pretty big: 402 votes in the electoral college and an eleven-point margin of the popular vote. Cisneros’s campaign not only won back all of the traditional Democratic strongholds, but also narrowly flipped several states which hadn’t voted blue in decades: Louisiana, Kentucky, as well as (thanks to high turnout among Latino voters, over 80% of whom cast their ballots for Cisneros) Arizona, Florida, and the senator’s own home state of Texas. History had been made—for the first time since its founding, the United States of America had elected a non-white President.

South of the border, reactions to the victory were ecstatic—not just because of the new President’s heritage, but also because of his promise to significantly reduce Mexican debt. For the moment, though, most Mexicans were far more preoccupied with political developments in their own country, particularly as the post-PRI party system began to take shape ahead of the hotly-anticipated Congressional elections of 1997.

For three years, the PAN had held a commanding presence in Mexican politics. As the only opposition party in the election of 1994, the PAN had reaped almost all of the benefits from the PRI’s landslide defeat, capturing 413 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 112 in the Senate. But the following years would show just how disorganized and incoherent the party had become. Over the course of the 61st Congress, as the PAN’s social democratic left wing clashed with the conservative old guard over everything from labor reform, foreign policy, the Zapatistas and the welfare state, the burgeoning community of political columnists began to predict that a split of some kind was inevitable. It came sooner than expected. On April 13, 1996, more than a year out from the elections of 1997, several prominent panista progressives, including Mexico City Mayor Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, Senate President Pablo Gómez and Chamber of Deputies President Sergio Aguayo, announced the formation of a new political party: Esperanza Democrática, or Democratic Hope. Pledging to stand for the “rights of all workers and farmers” and the “principles of Cárdenas and Madero,” ED, as it soon became known, was instantly endorsed by all the major labor unions, and President Muñoz Ledo lent the new party his tacit support (though he stopped short of joining, determined as he was to rule as an independent).

Within two weeks, 136 panista deputies—one-third of the entire PAN caucus—had joined the new, left-wing party, as had 57 of the 72 remaining priístas. In the Senate, the picture was even worse, as 43 of the PAN’s 112 senators announced their defection. Aguayo and Gómez instantly lost their leadership positions in the Chamber and the Senate and were replaced, respectively, by conservative panistas Carlos Medina Plascencia and Ernesto Ruffo Appel. But the new party had left its mark: though it had kept its majorities in both chambers, the PAN presence was greatly reduced, and its credibility as a governing party had taken a serious hit.

Perhaps more damaging, however, was the response of the party leaders. Within weeks of the split, PAN godfather Diego Fernández de Cevallos called a conclave of the most prominent panistas at his home in the Bosque de Chapultepec, where it became clear that, even without the breakaway left, the PAN’s remaining faithfuls did not agree on how the party should face the future. Fernández de Cevallos, Luis Álvarez, and other old-liners demanded that the PAN become the “conscience of Mexico” by returning to its traditional, Catholic roots. But younger, more technocratic members insisted that the party should work to capture the liberal-minded, white-collar middle class by modernizing and moving to the center. Press correspondents noted the suspicion with which senators, deputies and activists needled each other over their partisan loyalties, with deputy Carlos María Abascal declaring that there were “traitors still in our midst”. In a column in the left-leaning newspaper Nuevo Siglo, PAN-turned-ED deputy Julio Scherer sneered that the PAN’s attitude toward dissent was little more tolerant than that of the PRI under Bartlett.

For several months, the PAN’s two remaining factions battled over policy, messaging, and control over the Congressional legislative calendar. The repeated recriminations cost the party a further eighteen seats in the Chamber of Deputies and six in the Senate. Through most of the fall 1996 session, ortodoxo and modernista legislators squabbled over votes and committee assignments, culminating in a dramatic attempt in October to unseat Carlos Medina Plascencia and Ernesto Ruffo Appel from their leadership positions. The bid failed, and some overly optimistic technocrats declared that their camp had triumphed. Three days later, Fernández de Cevallos, Carlos María Abascal and several other prominent ortodoxos declared the birth of yet another breakaway group: the Christian Democratic Party. Twenty-four of the PAN’s 277 remaining deputies jumped ship, as did nine of its 63 remaining senators—not quite the massacre some had expected, but enough to cut down the PAN majority in the Chamber to a measly eight seats and remove it entirely in the Senate (where Ruffo Appel survived as president only by making a deal with the ED caucus to advance legislation creating a permanent envoy from Los Pinos to the State of Zapata). The resulting ideological chaos would consume the PAN for most of 1997.

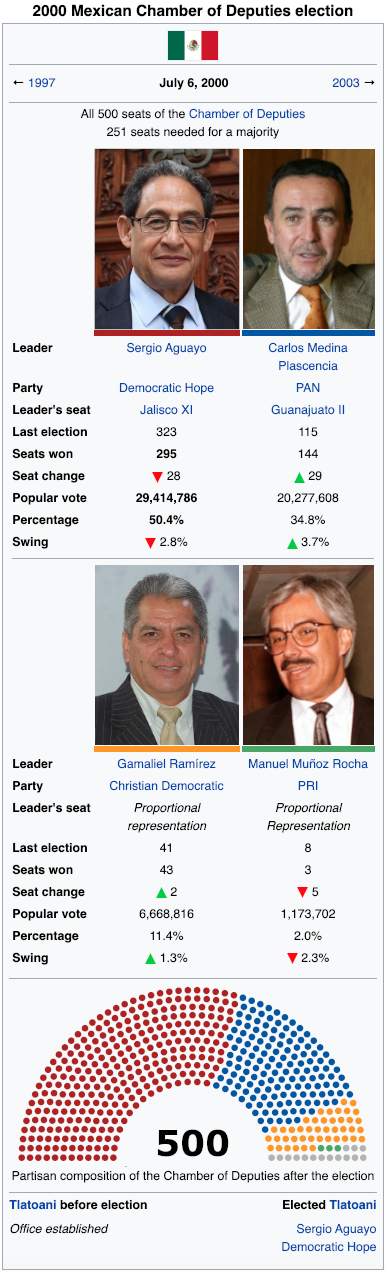

Meanwhile, as the PAN convulsed, Democratic Hope was busy rediscovering the time-aged art of electioneering. Elections to the Chamber of Deputies were scheduled for July 6, 1997, and the fledgling party’s leadership set to work rebuilding and refining the well-oiled electoral machine which had delivered Muñoz Ledo’s staggering landslide three years earlier. ED was well-equipped for election season: the activist labor unions, whose strident campaigning efforts on Muñoz Ledo’s behalf had delivered millions of votes back in 1994, had all announced their support. Many of the party’s new deputies hailed from rural districts where they had extensive contacts with local power brokers, allowing them to access isolated communities which would otherwise have been politically inaccessible. In addition, many of post-PRI Mexico’s most popular political figures, including President Muñoz Ledo, Sergio Aguayo and Mexico City Mayor Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, had either joined the party or lent it their unspoken support. And the momentum was showing. By March of 1997, ED legislators had taken control of the state legislatures of Coahuila and Morelos and had nominated a full slate of candidates for the federal elections.

While ED prepared itself, President Muñoz Ledo worked to make the elections of 1997 the most free and fair in Mexican history. In 1995, Muñoz Ledo’s administration had formed the Institute of Electoral Security under the leadership of political scientist José Woldenberg. Armed with a $1.2 billion budget, the Institute had trained nearly half a million people, chosen at random from the voter registration rolls, to man the polls, backed up by opposition poll-watchers in almost every voting place from Tijuana to Cancun. The Institute had also designed a special, narrow voting booth wide enough to fit only one person, allowing every voter to cast their ballot without fear of being watched. When election day came on July 6, the polling went very smoothly. TV Azteca reported a few “irregularities”—a sudden power outage at one polling place in Tonatico, ballot boxes pre-stuffed for the PAN at a few stations in suburban Monterrey, and one quixotic, pistol-brandishing PRI holdover in rural Campeche who made off with a few boxes—but overall, the vote was cleaner and more orderly than it had ever been in Mexican history. President Muñoz Ledo would later write about how proud he had been to turn down Defense Secretary Gutiérrez Rebollo’s offer to have the Army watch over the polls as it had done in 1994, a decision which drew praise from international observers (although some have since pointed out that the Army only felt comfortable with Muñoz Ledo’s refusal because it feared no threat to its drug-trafficking activities from any of the competing parties).

To this day, the election results remain a matter of debate. Many panistas still grumble that they might have done better if the PDC hadn’t split the right-wing vote, but subsequent analyses have shown that the Christian Democrats did not run candidates in enough seats to cause a large-scale defeat. Edecos have found other explanations: that ED had a more solid lock over its key constituencies than the PAN did over its own, or that voters had grown tired with the PAN’s dysfunctionality and factionalism. But among supporters, the most popular narrative is that ED’s message simply resonated better with the electorate. Since mid-1996, when key elements of his agenda stalled in the increasingly fractious Congress, President Muñoz Ledo had been advocating for an entirely new constitution, claiming that the Constitution of 1917 was too limited and too easily-abused to allow for the kind of sweeping changes Mexico demanded. Democratic Hope had made this the central plank of their platform, calling for a constitutional convention which they hoped would allow for deep, fundamental reforms to the welfare state, the ejido system, and the balance of power between the states and the federal government. In contrast to the PAN, which (during the short interludes between its intraparty squabbles) offered a more restrained, liberal platform involving a lowering of barriers to international trade, deregulation of business and privatization of some state-owned enterprises, ED promised to strive boldly ahead to forge the institutional structure of post-PRI Mexico and continue the work of what Octavio Paz had already dubbed “the Second Mexican Revolution”. Democratic Hope won, supporters say, because it embodied just that: hope.

Whatever the reason, ED’s victory was decisive. With 53% of the popular vote, the party captured 323 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, just shy of the two-thirds needed to amend the Constitution but still more than enough to pass crucial legislation. The Senate, which was not due for re-election until 2000, remained under split control, but a partnership with the Christian Democrats soon gave ED the leadership of the upper chamber. In the concurrent state elections, things were less bleak for the PAN, which captured the governorships of Querérato, Nuevo León and San Luis Potosí and retaining control of the state legislatures in Guanajuato and Baja California. But ED held its own both outside the capital city (where edecos were elected governor in Colima and Campeche) and inside it (where Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas won the first-ever election for Mayor of Mexico City).

But while the winners and losers were clear, the elections of 1997 were a triumph for everyone in Mexico. By far the freest and the most pluralistic in Mexican history, they proved that the country could function and thrive without PRI leadership, and the PAN’s and PDC’s genuine, if begrudging, concessions showed that the leaders of opposing parties could be trusted to win and lose with grace. Perhaps the only true losers were the PRI: having lost most of its remaining legislators to the opposition over the course of the 61st Congress, the former party of power was left dazed and rudderless without a clear national leader, message, organization, or fundraising strategy. Utterly annihilated on the grassroots level, not one of the PRI’s candidates won his district, and “the party of crooks, thieves and narcotraficantes” (as dubbed by newly-elected ED deputy Carlos Monsiváis) was reduced to a pitiful eight seats, all awarded by proportional representation. The old regime was well and truly dead.

To mark the occasion, on July 15, 1997, U.S. President Henry Cisneros signed a piece of legislation which reduced Mexico’s foreign debt from $31 billion to $10 billion. The following week, President Cisneros made his first state visit south of the Rio Grande, where he stood side-by-side with President Muñoz Ledo on the front steps of Los Pinos and declared in fluent Spanish that a new beginning had been reached in Mexican-American relations. Another beginning dawned soon after: on September 1, 1997, the 62nd Congress of the Union was sworn in at the newly-rebuilt Palace of San Lázaro, and the new President of the Chamber of Deputies, Ifigenia Martínez, declared that “the new Mexico has just been born”.

The following three years would lay the foundation for how exactly the new Mexico would look.

Wow.

The PAN experiencing political schisms? That's very interesting.

I love your choice of the political parties. However, it would probably make more sense if the ED was the successor of the Frente Democrático Nacional than as a derivative of the PAN, since the FDN and TTL's ED resemble similar political ideology.

President Cisneros?

Although not impossible, I'm still surprised to read about someone who isn't a 100% WASP becoming President of the United States 13 years earlier!

I'm not saying it's an ASB idea (I'd argue it's not) but... it seems a bit too soon. I know in real-life Jesse Jackson ran to be chosen as the Democratic candidate during the 80's, but TTL's Cisneros must have been really popular for the Democrats to have chosen him. Given all that has occurred between Cisneros and Bartlett's Mexico, It is enough to convince me that it's plausible for Cisneros to run for president AND win, but it may not convince everyone else.

Besides that, you are doing an excellent job, Roberto El Rey! Keep up the good work!

When will we see the Pope visit Mexico?

Last edited:

Bookmark1995

Banned

There's something I've been wondering.

OTL, Texas was effectively a Republican stronghold by the early 2000s, when Democrats lost all control of statewide offices and legislative power.

I wonder how Texas remaining a Democratic state TTL, and even electing a Hispanic American, will change American politics. If Cisneros can keep Texas a Democratic stronghold, how would the GOP adapt if they could no longer rely on it to win races? Would you see a more centrist Republican Party emerge in time?

OTL, Texas was effectively a Republican stronghold by the early 2000s, when Democrats lost all control of statewide offices and legislative power.

I wonder how Texas remaining a Democratic state TTL, and even electing a Hispanic American, will change American politics. If Cisneros can keep Texas a Democratic stronghold, how would the GOP adapt if they could no longer rely on it to win races? Would you see a more centrist Republican Party emerge in time?

IOTL the Tribune wasn't founded until 2009 - I do wonder how an earlier statewide paper more like the New York Times than The Atlantic would have affected Texan politics, even though I suspect the answer is "not much". Maybe it muscles in on the Quorum Report's niche during the Lege's sessions.one devout listener claimed to the Texas Tribune that the former mayor’s candidacy was divinely ordained.

L E N ALena Guerrero, whose career had seemingly ended in 1991 when it was revealed she had lied on her resumé, but who made a stunning comeback by riding Cisneros’s coattails to victory over businessman Robert Mosbacher, Jr.

I do wonder - if things go south, no pun intended, either with regard to Mexico or otherwise, I can't help but be afraid that Cisneros' ethnic background might play an Obama-like role in energizing American nativists.While a lethargic Dole invoked high urban crime rates to frighten rural and suburban whites (a Nixonesque strategy which may indeed have helped him win a state or two), Cisneros placed himself above petty racial rivalries and promised to fundamentally reconstruct the American city while delivering solutions for all Americans.

Love the Nahuatl titles there, even if Aztec revivalism sends a... weird... message.

Fantastic facial hair on Sr. Madero there. Darned if that ain't a face made for Catholic traditionalism.

Last edited:

On the other hand, given how much he made his career on sinning and learning his lesson, I don't think it's something he could get away with twice.If he presides over an era of calm and economic prosperity like Bill Clinton did, few people would actually care. While most people did believe Clinton was wrong to indulge in his affair, few actually were upset with how he was actually doing as President, and Gore lost because he tried to push Clinton away.

Of course, that's assuming it stays a Democratic stronghold - as late as 1994 it was electing Democratic statewide officials. One point in the Texas Dems' favor is that OTL, even before 2020, Hispanic voters in Texas were a lot more Republican than in most states - not that the Democrats didn't tend to win majorities, but IIRC Bush won more than 40% of Hispanic votes in both his runs for Governor, and Perry didn't do much worse. I don't know that this happens the same way here, though I also don't think that the mere fact of Cisneros' presidency is enough to make Hispanic Texans vote like Hispanic Californians.There's something I've been wondering.

OTL, Texas was effectively a Republican stronghold by the early 2000s, when Democrats lost all control of statewide offices and legislative power.

I wonder how Texas remaining a Democratic state TTL, and even electing a Hispanic American, will change American politics. If Cisneros can keep Texas a Democratic stronghold, how would the GOP adapt if they could no longer rely on it to win races? Would you see a more centrist Republican Party emerge in time?

It might also make the Democratic Party more conservative - Texas Democrats of that era tended to be disproportionately Blue Dogs, and anything that gives them more influence probably drags the party to the right, especially on environmental/energy issues. Let a thousand Henry Cuellars bloom...

Bookmark1995

Banned

Of course, that's assuming it stays a Democratic stronghold - as late as 1994 it was electing Democratic statewide officials. One point in the Texas Dems' favor is that OTL, even before 2020, Hispanic voters in Texas were a lot more Republican than in most states - not that the Democrats didn't tend to win majorities, but IIRC Bush won more than 40% of Hispanic votes in both his runs for Governor, and Perry didn't do much worse. I don't know that this happens the same way here, though I also don't think that the mere fact of Cisneros' presidency is enough to make Hispanic Texans vote like Hispanic Californians.

Unlike Pete Wilson, who launched Proposition 187 to stir up white voters, George W. Bush didn't try and alienate the Hispanic community. This is one of the reasons why Texas has remained red while California went blue.

If Texas Republicans TTL avoid dogwhistles, they could still remain a prominent force.

It might also make the Democratic Party more conservative - Texas Democrats of that era tended to be disproportionately Blue Dogs, and anything that gives them more influence probably drags the party to the right, especially on environmental/energy issues. Let a thousand Henry Cuellars bloom...

The Texas Democrats of the 1990s were a pretty conservative bunch. Ann Richards, as governor, actually signed laws criminalizing homesexuality.

Bob Bullock, the last Democratic Lieutenant Governor, worked well with George W. and was functionally a Republican.

So presume that like OTL, TTL Democrats will gradually lose the American heartland, than Cisneros isn't really the long term trend, since the party could continue to shift to the left on crucial social issues once he leaves office.

The OTL Arkansas Democrats remained prominent well into the 2010s, but today, Bill Clinton acknowleges that even he couldn't win the state if he ran again.

After 16 years of Republican presidency and how much of an utter gutterball the last few years were, I'm pretty sure even a good chunk of the Blue Dogs are likely gonna remain passive lest the new firebrands begin outing them in the primaies.On the other hand, given how much he made his career on sinning and learning his lesson, I don't think it's something he could get away with twice.

Of course, that's assuming it stays a Democratic stronghold - as late as 1994 it was electing Democratic statewide officials. One point in the Texas Dems' favor is that OTL, even before 2020, Hispanic voters in Texas were a lot more Republican than in most states - not that the Democrats didn't tend to win majorities, but IIRC Bush won more than 40% of Hispanic votes in both his runs for Governor, and Perry didn't do much worse. I don't know that this happens the same way here, though I also don't think that the mere fact of Cisneros' presidency is enough to make Hispanic Texans vote like Hispanic Californians.

It might also make the Democratic Party more conservative - Texas Democrats of that era tended to be disproportionately Blue Dogs, and anything that gives them more influence probably drags the party to the right, especially on environmental/energy issues. Let a thousand Henry Cuellars bloom...

Wasn't that already dealt with?Much as I love the idea of Cisneros as President, I wonder if he’s going to be taken down ITTL the same way he was OTL: payments to a mistress.

Bookmark1995

Banned

After 16 years of Republican presidency and how much of an utter gutterball the last few years were, I'm pretty sure even a good chunk of the Blue Dogs are likely gonna remain passive lest the new firebrands begin outing them in the primaies.

Depends on what kind of policies Cisneros supports.

It will certainly try, though it won't achieve every one of its aims. More on this in the next update!Would the new congress push for new military reforms and clear up the bureaucracy?

So happy to hear you say that! One of the great pleasures of writing this has been the chance to do some in-depth research into a country all Americans should know a hell of a lot more about.I discovered this timeline yesterday and have finished reading all the chapters just now. All I can say is you've done a great job, Roberto! You've shown a deep knowledge and understanding of Mexico. Even as a Mexican myself, I have discovered plenty of stuff in this timeline that I didn't know about before and I am now reading about. Looking forward to the next update, I'm really curious on what shape will the country take in the following years.

Just a small niptick: in the wikibox of the CDP, the Spanish name should be Partido Demócrata Cristiano.

And thanks for the correction! I'll fix that.

Much as I love the idea of Cisneros as President, I wonder if he’s going to be taken down ITTL the same way he was OTL: payments to a mistress.

As @Indicus points out, Cisneros goes down a more virtuous path in OTL. I actually mentioned in the update how the whole reformed-adulterer shtick actually becomes an asset to his campaign.Earlier on in this TL he has a near death experience that makes him change his ways.

Yeah, it felt pretty good to finally write that update. I conceived of the idea of President Cisneros years ago and it's so gratifying to get to the point where I can actually put the words on the page!Great update!

You've been laying the seeds for President Cisneros for so long that it's almost cathartic to see it bear fruit. He's a really good choice for this TL, too: beyond the aspect of his heritage, his rise ITTL is a great example of how bit players IOTL could have had their lives and careers go very differently with only a few differences. Not sure I've seen Cisneros used in any TL at all, actually, even list or infobox ones.

And I definitely lucked out when I found him. I've seen him in a few lists before, but overall he's a blindingly obvious candidate for mid-90s/early 2000s president and I'm surprised more people don't use him!

What is the reaction from Latin America regarding the new democratic regime in Mexico and a Hispanic President in the US?

Most Latin Americans ITTL aren't that clued in to the inner machinations of U.S. politics, but when Cisneros is sworn in, they are excited at the prospect of a President who speaks Spanish and has Hispanic roots.I'd figure it would be the same reaction Africans had to President Obama: many Latin Americans would be jumping for joy at the election of a Hispanic President.

I defer to the estimable @Wolfram re: the Texas stuff. As for the stuff about the GOP, you're right in speculating that the party will end up tethered a bit closer to the center line, though for more than one reason (I believe I hinted at President Jon Huntsman a few updates ago—that should give you a vague idea).There's something I've been wondering.

OTL, Texas was effectively a Republican stronghold by the early 2000s, when Democrats lost all control of statewide offices and legislative power.

I wonder how Texas remaining a Democratic state TTL, and even electing a Hispanic American, will change American politics. If Cisneros can keep Texas a Democratic stronghold, how would the GOP adapt if they could no longer rely on it to win races? Would you see a more centrist Republican Party emerge in time?

More on this in the next chapter!Love the Nahuatl titles there, even if Aztec revivalism sends a... weird... message.

Yeah, I tried to look for a more polished image but in the end I just decided hey, why not go with Christian fundamentalist Santa Claus.Fantastic facial hair on Sr. Madero there. Darned if that ain't a face made for Catholic traditionalism.

Also, important announcement: the next update will be the LAST UPDATE OF THE STORY! There will be an epilogue afterward to round things out a bit, but we are nearing the end of this timeline. Thank you all so much for sticking with it for this long, I can't wait to serve up the big finale!

Hey @Roberto El Rey, I have a question about something I read in this timeline. You wrote that the Mexican Congress did not have any protocol in regards to a PRI loss? Could you point me to sources about that specifically? Because it sounds like a really fascinating procedural issue, especially due to the PRI's similarity with Golkar, the ruling party in my own home country for much of the same period as in this TL.

Holy tamales! This gonna be good, senor!Also, important announcement: the next update will be the LAST UPDATE OF THE STORY! There will be an epilogue afterward to round things out a bit, but we are nearing the end of this timeline. Thank you all so much for sticking with it for this long, I can't wait to serve up the big finale!

Also, important announcement: the next update will be the LAST UPDATE OF THE STORY! There will be an epilogue afterward to round things out a bit, but we are nearing the end of this timeline. Thank you all so much for sticking with it for this long, I can't wait to serve up the big finale!

Oh, wow.

I can’t believe it’s almost over.

Use as much time as you need to prepare your grand finale.

Good luck!

Yeah, I tried to look for a more polished image but in the end I just decided hey, why not go with Christian fundamentalist Santa Claus.

Eh, I’d argue that Catholic traditionalism is NOT fundamentalism.

Or at the very least, they’re not creationists in the same way that some Protestants are in the United States.

I've caught up on TTL and I've got to say it's amazing. I don't know anything about Mexican history but TTL made me want to do research on the country, specifically PRI, the PRD, PAN, and the political history. I'm glad TTL was written just for making me want to and actively research Mexican history which is probably the best thing IMO an alternate history can do, make you want to learn about history that you never would.

Otherwise you took an obscure POD and used it to craft a world, just eight years out has made the world radically different outside of Mexico with President Cisneros and the Progressive Conservatives winning in '92. Not to mention Bush winning in '92 also. That's a great thing to see in any TL and combined with frankly great writing makes this a great read. In addition to that I can tell you did a lot of research and know what you're writing about despite me not knowing much on Mexican history. It was also great how you portrayed the first Salinas. I thought his actions would lead to the revolution but I was wrong. In fact Salinas in comparison to Salinas the second and Bartlett was the man who could've prevented the revolution ITTL. His assassination was shocking to read as things looked like they were getting better despite the authoritarian grasp of PRI. The Selva Rebellion felt like a great payoff ITTL story wise. Finally the Zapata election was masterfully written IMO. You first made what looked like blatant rigging and a massive win for PRI with no resistance to the election a powerful moment that was genius. Revolutionaries infiltrating a party and going along with the criminal rule only to take control and use the rigging against them was an excellent twist that I wasn't expecting. Henry Cisneros was a great choice for president within the context of the TL and seems plausible.

Overall it was a very creative TL and I want to do learn more about Mexican history thanks to TTL. Considering it borders the USA it seems important and fascinating. I applaud you for the masterful writing of TTL and amazing POD. A very fine TL.

Otherwise you took an obscure POD and used it to craft a world, just eight years out has made the world radically different outside of Mexico with President Cisneros and the Progressive Conservatives winning in '92. Not to mention Bush winning in '92 also. That's a great thing to see in any TL and combined with frankly great writing makes this a great read. In addition to that I can tell you did a lot of research and know what you're writing about despite me not knowing much on Mexican history. It was also great how you portrayed the first Salinas. I thought his actions would lead to the revolution but I was wrong. In fact Salinas in comparison to Salinas the second and Bartlett was the man who could've prevented the revolution ITTL. His assassination was shocking to read as things looked like they were getting better despite the authoritarian grasp of PRI. The Selva Rebellion felt like a great payoff ITTL story wise. Finally the Zapata election was masterfully written IMO. You first made what looked like blatant rigging and a massive win for PRI with no resistance to the election a powerful moment that was genius. Revolutionaries infiltrating a party and going along with the criminal rule only to take control and use the rigging against them was an excellent twist that I wasn't expecting. Henry Cisneros was a great choice for president within the context of the TL and seems plausible.

Overall it was a very creative TL and I want to do learn more about Mexican history thanks to TTL. Considering it borders the USA it seems important and fascinating. I applaud you for the masterful writing of TTL and amazing POD. A very fine TL.

Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election

When the 62nd Congress of the Mexican Union was gaveled into session in 1997, the assembled legislators had one thing on their minds: change. The various factions of Mexico’s blossoming, multi-party system disagreed on what exactly should be changed, but everyone could see that the system needed reform, and needed it now. And while only Democratic Hope had openly campaigned on the promise of a new constitution, by the time the new legislators congregated in the rebuilt Palace of San Lázaro, most of them had more or less accepted that the changes they sought would require nothing less than a full-on rebirth of Mexican political thought.

The problem was how to organize one. The Political Constitution of 1917 included no provision for a constitutional convention. It would be simple enough on paper to just amend the constitution and provide for one, but finding the requisite two-thirds majority in the Chamber and the Senate proved challenging. ED proposed a national convention made up of elected delegates, but the PDC and the PAN, still reeling from their landslide defeat, pushed back in fear that such a convention would be stacked against them. Instead, the Congressional right jointly proposed another model: a committee of prominent members of the civil society, half appointed by the majority in Congress and half by the opposition, which would draft a new constitution and then submit it to a national referendum for approval. ED and its allies lambasted this plan as elitist and undemocratic, but they had little choice but to take it seriously as the opposition pledged to block any other plan. Eventually, after a month of back-and-forth, the two sides agreed to a hybrid plan. The new constitution would be drafted over a twelve-month period by a constitutional convention consisting of two separate bodies—a Popular Assembly with 300 delegates elected by the people and a Council of Deliberation with 72 members appointed by the Congress—which would split up into various Committees, each equally divided between left- and right-leaning members. These Committees would investigate their respective policy areas and issue reports, which the wider Convention would then compile into a single document. Each body of the Convention would have to endorse the final draft by a majority of at least three-quarters, and the final document would have to be approved in a national referendum.

Though the Popular Assembly were officially non-partisan, it was clear that most of the 300 delegates who were elected to the Convention in mid-January at least sympathized with ED and its principles. But that didn’t stop a substantial number of eclectic independents from being elected. Delegates like activist Marco Rascón Cordova (who showed up to the convention’s first session in character as the poverty-fighting superhero Superbarrio Gómez) and the cowboy hat-wearing Jalisco rancher José González Rosas (whose death nine years later at the hands of drug-trafficking soldiers would help ignite a fiery, public rage at the unholy union between the narcos and the Army). Characters such as these turned the Convention floor into a lively hall of raucous, often expletive-laden debate, and neither Televisa nor TV Azteca had to worry about their ratings while the Convention was in session. The Council of Deliberation, by contrast, was considerably more stodgy and sedate, as the slate of trustees approved by the Congress included such even-keeled characters as the poet laureate Octavio Paz and the matronly, ex-priísta elder stateswoman María de los Ángeles Moreno.

Despite the stark contrast between the two deliberative bodies, they quickly became the beating heart of Mexican political life. Held in multiple different sessions at the UNAM campus over a year-long period from March 1998 to January 1999, the Constitutional Convention became the linchpin of Mexico's national renewal. Nearly all the major newspapers assigned full-time correspondents to cover the proceedings, and all major debates and hearings were broadcast live on cable news networks. Within weeks, members of Congress were complaining about how little attention they were getting from the press, as the Convention proceedings sucked up all the limelight.

To a nation unaccustomed to open discussion of political and social problems, the Constitutional Convention became a source of fascination. Many of Mexico’s most prominent political pundits made their bones reporting on the Convention’s many testimonies, committee hearings and tribunals, and some of modern-day Mexico's brightest political stars were involved in the Convention as delegates or council members.

First on the agenda was civil and human rights. The most obvious ones, like assembly, speech, religion, press, and protest, had been officially enshrined since 1917, but successive PRI governments had ignored these rights whenever it suited them. Other rights, like that of citizens to access government records, had never even existed, allowing the state to maintain an impenetrable veil of secrecy over its more sinister activities. Pulitzer laureates Lydia Cacho and Xanic von Bertrab, though not delegates themselves, were very public in calling on the Convention to right those wrongs, and Council member Jorge Zepeda Patterson was swift in answering the call. As the founder and publisher of the newspaper Nuevo Siglo, Zepeda grasped how the PRI machine had been able to manipulate the press through its dominance of the paper and advertising trades. The resolution he introduced in April, which explicitly banned the state from withholding resources from a news outlet on the basis of its editorial stance, was adopted with zeal. Delegate Rosario Ibarra’s resolution that the state immediately disclose all files regarding torture, forced disappearance, the Dirty War, and other human rights abuses was approved without a single abstention. To give these provisions teeth, delegate and human rights lawyer Jorge López Vergara proposed the creation of an independent Ombudsman for Human Rights empowered to investigate government abuses, charge military and civilian officials with crimes, and refer certain cases directly to the Supreme Court of Justice. López’s plan also stated that when the high Court ruled on such questions, its decisions would be binding not just for the parties that had filed the case but also, in a reversal of the centuries-old Otero principle, for the entire country.

Though there was broad consensus on these issues, some questions were fractious and controversial, such as the future of the welfare state. From the very beginning, Mexico’s social security system had been deeply flawed: government-funded health insurance, work injury compensation, and retirement pensions had only ever been available to members of oficialista labor unions, and the most powerful syndicates had hogged all of the best benefits while the rest offered only piecemeal coverage. Mexicans who did not belong to any union (meaning almost everyone outside the cities) had no safety net at all. The task of laying the groundwork for a new system fell to the 24-member Joint Committee on Solidarity and Social Welfare, which, in accordance with Convention rules, was equally split between left and right. The two sides disagreed profoundly on how exactly the changes should look and how far they should go—the left-leaning Committee members advocated a universal, crade-to-grave system of entitlements, while the right-leaning caucus, led by PAN economist Josefina Vázquez Mota, pushed for a much more conservative system designed only to provide the truly indigent with the minimum skills necessary to enter the workforce.

It quickly became apparent that on this issue, the conservatives had the upper hand. The leftists were split between pro-worker delegates led by former Acuña labor leader Juan Tovar, and pro-farmer delegates led by former Guerrero Congressmen Jorge Eloy Martínez. This split allowed the conservatives to dominate the Committee proceedings, calling up a cavalcade of economists and businessmen to give favorable testimony and drafting reports and recommendations with zero involvement from the left. However, once they realized that the Committee’s final recommendation would be a right-wing wishlist, the leftist delegates came together to stonewall all Committee business and demand rewrites of all major reports. Conservative media pundits, particularly at TV Azteca, tore the delegates apart for obstructionism and immaturity, but there was little Vázquez and her team could do as long as they lacked a working majority. The leftists, meanwhile, could do little else but obstruct, since they still lacked the cohesion to put together counter-proposals of their own. The Committee eventually decided to kick the can down the road, providing the basic skeleton of a welfare state and leaving it up to future administrations to hang meat on the bones. The Committee’s final report consisted mainly of broad principles, including that all communities, whether rural or urban, must have equal access to social programs, and that employee contributions to any work-based insurance funds should never exceed employer or government contributions.

Somewhat less acrimonious was the question of agricultural reform. Since the days of Lázaro Cárdenas, millions of Mexican farmers had been wringing their bread out of small, communal plots of state-owned land called ejidos. By 1998, this system was in crisis. Because communal farmers did not own the land they cultivated, they could not sell it or borrow money against it. The only sure source of capital was the federal government, which doled out funds only when it was politically convenient. Many ejidos lacked not just modern farming equipment but also electricity and running water, and after Carlos Salinas loosened import restrictions in 1989, millions of ejidatarios had been run out of business by foreign grain, feeding a vicious cycle of falling food production and growing import dependence. Many farmers had already been forced to leave their homes and flee into the cities, where they faced the blight of urban poverty, or to the United States, where conditions were little better. On April 6, one ejidatario delegate from Michoacán gave a moving speech to the convention, in which he described the sorrow he felt while watching his wife and children grow emaciated on a bare-bones diet of corn and beans, and begged the Convention to turn things around before it was too late.

For years, the farming community had been ignored by PRI governments intent on promoting industrialization and urbanization. To millions of ejidatarios, the Constitutional Convention represented the first chance in 65 years to petition the government to make genuine improvements in their lives.

Despite the Convention’s rules on equal apportionment, the Committee on Agricultural Reform was far less partisan than most of its counterparts. Nearly all the members were from rural, ejido-heavy regions and had a visceral understanding of the problems facing rural Mexico. Within three months, the Committee had put together a detailed, ambitious set of proposals, including a program of joint state-farmer ownership to give the farmers a stake in their own production, a pledge from the federal government to provide all ejidos with electricity and running water by 2014, authorizing individual ejidos to merge with each other in order to increase production and reap economies of scale, and requiring every state to establish an agricultural college with free tuition for local farmers. Perhaps the most extraordinary proposal would have bound the federal government to set aside 3% of its total annual revenue to invest in agricultural production and “the general welfare of the ejidatarios”. While this constraint was eventually whittled down to 1.8%, the rest of the Committee’s recommendations were adopted with little modification in what was seen as a major triumph for the farmers.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment of the Convention concerned the matter of the Zapatistas. Since Subcomandante Marcos’ march on Mexico City in 1995, little had changed between Mexico City and San Cristóbal. President Muñoz Ledo had continued his benign neglect of the State of Zapata, which continued to exist as an autarkic confederation of self-sufficient communes, and which was growing increasingly isolated from the rest of the country. No attempts had been made to negotiate, as the federal government did not recognize the authority of Bishop Samuel Ruiz, the State’s nominal governor. The Mayan delegation to the Constitutional Convention, consisting of 12 delegates from majority-Indian constituencies in the south, pressed hard for the recognition of Zapata as a full-fledged state with special constitutional status, and for the adoption of the Indigenous Bill of Rights, which had failed in the Senate two years earlier. But these efforts led nowhere. Recognizing Zapata was a bridge too far even for many of the more left-leaning delegates, and the Bill of Rights seemed equally unpalatable.

Then, on June 8, 1998, Mayan caucus leader and human rights activist María de Patricio Martínez read out to the Convention a letter from Subcomandante Marcos, pledging that the ELM would launch a renewed military offensive within week unless the Convention showed “the faintest interest in the well-being of the people of the State of Zapata”. Within hours, stock prices were dropping, and within days, President Muñoz Ledo was pressuring delegates to give in to the Mayans’ less outrageous demands. By June 13, the Convention’s joint committee had reached a compromise: the State of Zapata would not be officially recognized, but Mayan sovereignty over the area would be, meaning that the Zapatistas would be able to carry on in all but name. A separate legislature for the indigenous people was off the table, but legislators from Mayan-heavy districts would be permitted to form a caucus during every session of the Congress of the Union to block or approve matters affecting indigenous communities. Many indigenous rights, including the right to communal land ownership and the right of Mayan children to attend public school in their native language, would also be incorporated into the new Constitution. Critics raged in the press, accusing President Muñoz Ledo of “capitulating to the rebels”, but that didn’t stop the resolutions from being adopted by both bodies of the mildly-perturbed Convention.

María de Jesús Patricio Martínez, affectionately known as Marichuy, emerged as the Zapatistas’ champion in Mexico City. Her role in securing multiple key concessions at the Constitutional Convention helped pave the way for her to become one of the Mayan people’s most dedicated advocates under the new political system.

Despite all these major, far-reaching changes, perhaps the most noticeable result of the Constitutional Convention was the fundamental restructuring of Mexico’s political system. Since the dawn of the Mexican republic, the President had always exercised an inordinate amount of power over the country. After the excesses of the Bartlett years, it was clear that such a “hyper-presidentialist” regime, as Enrique Krauze called it, could not be allowed to continue. So, at the outset of the Convention, the Committee on Political Institutions was given the formidable task of designing an entirely new political structure for 21st-century Mexico. Unlike most of the Convention’s other Committees, which were proportionally distributed between members of the Popular Assembly and the Council of Deliberation, the Committee on Political Institutions was stacked with learned academics drawn from the upper chamber. The Committee’s two vice-chairmen, Juan Molinar Horcasitas and Jorge Castañeda (both renowned political scientists who had played key roles in the downfall of the PRI), enjoyed a warm relationship, developing ideas over cordial coffee chats and hashing them out on paper with the collaborative consent of their colleagues.

The system they eventually came up with was influenced by everything from American constitutional law to Irish naming conventions, and was approved with gusto by the Committee in November of 1998. The fundamental change was to move Mexico from a presidential to a semi-presidential regime, with a president tasked largely with ceremonial duties and political arbitration, and a prime ministerial figure charged with governing the country and implementing policies. The latter figure would take on the title of tlatoani, from the Nahuatl word for “leader”, and would be appointed by the Chamber of Deputies at the outset of every Congress. The tlatoani would be accountable to the Chamber of Deputies, which could remove him or her from office with a majority vote (although, in order to effect such a removal, the chamber would need to simultaneously appoint a new tlatoani to fill the void). The tlatoani would nominate most cabinet secretaries, all of whom would be subject to confirmation by both the Chamber and the Senate. The president would give up most administrative duties to the tlatoani, though he would still reserve some powers including the right to issue calls for new elections once per term, the right to appoint ambassadors and cabinet ministers charged with defense and foreign policy, and the right to negotiate international treaties.

Other major changes involved elections to the Congress. In addition to proportional representation, which had already been a feature of Mexican elections since the 1970s, future Congresses would be elected by ranked-choice voting in mixed-member constituencies. This, it was hoped, would make future dictatorships unlikely by preventing any single party from acquiring sole power. The ban on consecutive re-election was lifted for deputies, who were now permitted to serve up to three terms, and for senators, who could serve up to two. Senators would serve staggered terms, and elections to the Senate would be held every three rather than every six years to make the upper chamber more sensitive to swings in the national political mood. Also changed was the process of amending the Constitution itself, which had been so easy in years past that PRI Presidents had done it whenever it suited them without a second thought. Now, in addition to a two-thirds vote in both chambers of the Congress, constitutional amendments would require the consent of at least 17 state legislatures and popular approval in a nationwide referendum. These reforms were highly popular with the rest of the delegates (many were already sizing up future Congressional runs, and they liked any plan which gave more power to the legislative branch), and the Committee’s plan was adopted by the wider Convention with almost no modifications.

Because of their prominent role in crafting the new constitution’s political institutions, Juan Molinar Horcasitas (left) and Jorge Castañeda (right) were hailed as Mexico’s newest founding fathers. Both men would later hold positions of leadership in the system they helped design.

Not every aspect of the Convention was a triumph. Aside from the acrimonies gripping the welfare committee, the difficulties faced by delegate Samuel del Villar would foreshadow future political crises. As a vice-chairman of the Committee on Corruption Reform, del Villar hoped he could muscle through some measures to increase oversight over corrupt military officials. But when he tried to demand that all high-ranking Army officers submit twice a year to an audit by an independent, anti-corruption commission, he found it strangely impossible to get the rest of the Committee on his side. His proposal for a permanent prosecutor’s office to investigate civilian corruption was accepted unanimously, but when he tried to establish a similar office for the Army, several of his colleagues (particularly delegate Juan Galvan, an associate of former Defense Secretary Juan Gutiérrez Rebollo), insisted that the Army should have the right to investigate its own affairs, claiming that civilian prosecution would caused the Army to become politicized. del Villar’s many counterarguments proved inexplicably useless, as a sizable majority of the Committee’s members voted to make the Constitution almost entirely toothless regarding the issue of Army corruption. By 2008, an investigation by El Universal would reveal that over half of the members of the Committee on Corruption Reform had accepted bribes from cartel-affiliated Army officers (which would form just one piece of the massive wave of scandals that would rattle the foundations of the new republic just a few years after its inception).

Despite these difficulties, by late 1998, the Convention had pieced together all of the various Committees’ reports and recommendations into vast, sprawling document that touched every policy area from health care to press freedom to minority rights. The result was wildly imperfect, and no one side was entirely pleased with it, but in a system built for compromise, there could hardly have been a better outcome. The final document was approved near-unanimously by both Chambers of the Convention on January 13, 1999, two months ahead of schedule. Within two weeks, both chambers of the Congress had approved the new Constitution. The public referendum was scheduled for May, with the intention that the new system, if approved, would enter into force on the first day of the new millennium.

Though the people had three months to consider the new Constitution, three days would have been just as good. Nearly every day of the Convention had been broadcast live on cable TV, and every aspect of the writing process had been carefully analyzed by every pundit and politician in Mexico. By the time it the Convention was over, most of the people had already made up their minds about the new Constitution. And with all of the major political parties backing it to the hilt, there was little doubt as to the outcome of the referendum.

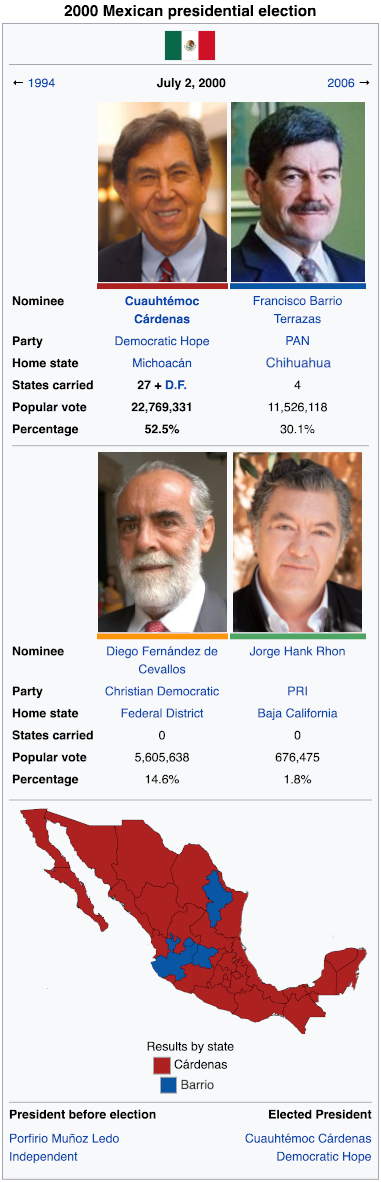

With over 80% of the vote, the Millennial Constitution received a resounding endorsement from the Mexican people and went into effect on January 1, 2000. That year would see the first federal elections under the new system, and Democratic Hope knew exactly whom to pick as their standard-bearers. For the new position of tlatoani, there was perhaps no man better suited than Sergio Aguayo. For years under the PRI, the human rights activist from Guadalajara had been one of the most passionate advocates for political change. As President of the Chamber of Deputies following the crucial election of 1994, Aguayo had pioneered the art of parliamentary wrangling while setting many important precedents, and as one of ED’s founding members, he could be trusted to govern responsibly while advancing the party’s core priorities.

The PAN did its best to oppose ED at the polls. By this point, the party leadership had managed to paper over most of the factional divisions, and tlatoani candidate Carlos Medina Plascencia forced the appearance of unity by demanding iron adherence to the party line. There were some rumblings of discontent (most conspicuously from Conchalupe Garza, a PAN Congressional candidate from suburban Monterrey, who was recorded on a hot mic comparing Medina and his staff to the Gestapo), but on the surface, the party held together well enough to increase its presence in the chamber by 22 seats and stave off a widely-expected threat from the Christian Democrats. But it just wasn’t enough. For all the PAN’s ideological coherence, Sergio Aguayo was simply too popular and ED had a lock on too many rural and urban districts to lose control. While ED won an outright majority in the Senate, allowing Senate President Adolfo Aguilar Zínser taking office as the first cuauhtlatoani, or vice-leader, the party would maintain control of the Chamber of Deputies with a reduced, but still commanding majority, and Sergio Aguayo would take office as the first tlatoani of 21st-century Mexico.

As for the Presidency, ED was represented by one of the most popular men in Mexico. Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas had always been reluctant to re-enter politics after his wife’s assassination. He had agreed to serve as Mayor of Mexico City only because he was assured that he would not be asked to run for a full term once direct elections were instituted. But, as he worked to cleanse the city government of corruption and graft, Cárdenas had slowly rediscovered the zeal for change that had first attracted him to seek public office in the 1970s. ED officials had approached Cárdenas about a presidential run as early 1997, and he had initially been skeptical about committing to such a responsibility. But once he realized that the new Constitution would turn the presidency into more of a ceremonial arbiter than the administrative and political epicenter of the country, he could barely declare his candidacy fast enough.

His victory wasn’t quite a 1994-style landslide, but it was still a resounding mandate. He captured an outright majority of the vote and won all but four states, surpassing ED’s share of the Congressional vote by two percentage points. It wasn’t the first time Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas had won a presidential election, but it was the first time he would be allowed to take office. The general’s son was on his way to Los Pinos, where he would set many precedents that would help define the presidency in post-PRI Mexico as a dignified figure above the political fray.

As per the provisions of the Millennial Constitution, Cárdenas was to be inaugurated not in December but in September, two weeks after the installation of the new Congress. In contrast to 1994, when Muñoz Ledo and his allies in the Congress had been too busy to stage even the most paltry of inauguration ceremonies, Cárdenas was determined to make his investiture one for the history books. Dignitaries from all over the Western Hemisphere were invited, including Prime Minister Tobin from Ottawa, President Cisneros from Washington, and President Arías Cárdenas from Caracas. The swearing-in was to take place not within the Chamber of Deputies, as was customary, but in the center of Mexico City, where the masses could gather together and watch it for themselves. As 250,000 Mexicans gathered in the Zócalo to watch a man they had elected get duly sworn in as head of state, the air was imbued with a distinct sense of optimism and hope. Mothers and fathers lifted their children up onto their shoulders so that they could watch the new president take the oath of office. After decades of struggling and striving, democracy had well and truly arrived in Mexico. But if the hard-won achievements of millions of activists and protesters were to survive, then the younger generation would have to understand the value of the gift they had been given, and they would have to work even harder than their parents had to preserve it.

The problem was how to organize one. The Political Constitution of 1917 included no provision for a constitutional convention. It would be simple enough on paper to just amend the constitution and provide for one, but finding the requisite two-thirds majority in the Chamber and the Senate proved challenging. ED proposed a national convention made up of elected delegates, but the PDC and the PAN, still reeling from their landslide defeat, pushed back in fear that such a convention would be stacked against them. Instead, the Congressional right jointly proposed another model: a committee of prominent members of the civil society, half appointed by the majority in Congress and half by the opposition, which would draft a new constitution and then submit it to a national referendum for approval. ED and its allies lambasted this plan as elitist and undemocratic, but they had little choice but to take it seriously as the opposition pledged to block any other plan. Eventually, after a month of back-and-forth, the two sides agreed to a hybrid plan. The new constitution would be drafted over a twelve-month period by a constitutional convention consisting of two separate bodies—a Popular Assembly with 300 delegates elected by the people and a Council of Deliberation with 72 members appointed by the Congress—which would split up into various Committees, each equally divided between left- and right-leaning members. These Committees would investigate their respective policy areas and issue reports, which the wider Convention would then compile into a single document. Each body of the Convention would have to endorse the final draft by a majority of at least three-quarters, and the final document would have to be approved in a national referendum.

Though the Popular Assembly were officially non-partisan, it was clear that most of the 300 delegates who were elected to the Convention in mid-January at least sympathized with ED and its principles. But that didn’t stop a substantial number of eclectic independents from being elected. Delegates like activist Marco Rascón Cordova (who showed up to the convention’s first session in character as the poverty-fighting superhero Superbarrio Gómez) and the cowboy hat-wearing Jalisco rancher José González Rosas (whose death nine years later at the hands of drug-trafficking soldiers would help ignite a fiery, public rage at the unholy union between the narcos and the Army). Characters such as these turned the Convention floor into a lively hall of raucous, often expletive-laden debate, and neither Televisa nor TV Azteca had to worry about their ratings while the Convention was in session. The Council of Deliberation, by contrast, was considerably more stodgy and sedate, as the slate of trustees approved by the Congress included such even-keeled characters as the poet laureate Octavio Paz and the matronly, ex-priísta elder stateswoman María de los Ángeles Moreno.

Despite the stark contrast between the two deliberative bodies, they quickly became the beating heart of Mexican political life. Held in multiple different sessions at the UNAM campus over a year-long period from March 1998 to January 1999, the Constitutional Convention became the linchpin of Mexico's national renewal. Nearly all the major newspapers assigned full-time correspondents to cover the proceedings, and all major debates and hearings were broadcast live on cable news networks. Within weeks, members of Congress were complaining about how little attention they were getting from the press, as the Convention proceedings sucked up all the limelight.

To a nation unaccustomed to open discussion of political and social problems, the Constitutional Convention became a source of fascination. Many of Mexico’s most prominent political pundits made their bones reporting on the Convention’s many testimonies, committee hearings and tribunals, and some of modern-day Mexico's brightest political stars were involved in the Convention as delegates or council members.