I think it would have been better to claim that the guy killed himself, a lot of people would have believed that. But this, this is a cover up that involves killing someone in addition to the dear presidente. The fallout will be epic *Gets a bag of Cacahuates Japoneses and eats while watching thread with anticipation*

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Al Grito de Guerra: the Second Mexican Revolution

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special AnnouncementHeck, there would probably be a sizable number of people who would have supported him more for murdering Bartlett.I think it would have been better to claim that the guy killed himself, a lot of people would have believed that. But this, this is a cover up that involves killing someone in addition to the dear presidente. The fallout will be epic *Gets a bag of Cacahuates Japoneses and eats while watching thread with anticipation*

Bookmark1995

Banned

Heck, there would probably be a sizable number of people who would have supported him more for murdering Bartlett.

Killing a rival, no matter how odious, is not a good precedent to set if you're trying to rebuild Mexico from decades of corruption and one-party rule.

This is a textbook case of "too clever by half": faking a failed escape seems like a clever way to announce Bartlett's death without arousing suspicion, but there's enough people and planning involved that the ruse is bound to be discovered eventually, at which point the plot looks sinister and nobody is going to believe the innocent explanation that "actually, he had already killed himself, we just disposed of his body in a very outlandish way". It would have been more prudent to simply tell the truth, and then invite independent, international investigators to confirm it; I think most people would believe such a report, and even among those who doubt it, there would surely be (as Wolfram mentions above) a certain portion of people who simply wouldn't care if Bartlett had been murdered.

But telling the truth would mean Munoz Ledo would have to grapple with a controversy from the very start of his term, and the prospect of that hanging over him, defining his image, presidency and legacy would surely spook him… so I'm not surprised he'd go along with a desperate gambit. He's looking for some semblance of stability, but unfortunately what he's chosen will certainly lead to more instability in the future.

But telling the truth would mean Munoz Ledo would have to grapple with a controversy from the very start of his term, and the prospect of that hanging over him, defining his image, presidency and legacy would surely spook him… so I'm not surprised he'd go along with a desperate gambit. He's looking for some semblance of stability, but unfortunately what he's chosen will certainly lead to more instability in the future.

Last edited:

Oh, I’m not saying it would be a good thing. But there’s not much upside in saying “oh, he died” because anyone who would hold Bartlett’s death against PML already halfway believes he was murdered. If it were just about short-term political upside (which it’s not), it doesn’t seem that much worse than saying “oh, he *wink* died”.Killing a rival, no matter how odious, is not a good precedent to set if you're trying to rebuild Mexico from decades of corruption and one-party rule.

Which nobody would ever do, because this is an absurd galaxy-brain strategy and the best thing to do would be, as @Kermode said, bring in independent investigators. But compared to this...

Last edited:

This is a textbook case of "too clever by half": faking a failed escape seems like a clever way to announce Bartlett's death without arousing suspicion, but there's enough people and planning involved that the ruse is bound to be discovered eventually, at which point the plot looks sinister and nobody is going to believe the innocent explanation that "actually, he had already killed himself, we just disposed of his body in a very outlandish way". It would have been more prudent to simply tell the truth, and then invite independent, international investigators to confirm it; I think most people would believe such a report, and even among those who doubt it, there would surely be (as Wolfram mentions above) a certain portion of people who simply wouldn't care if Bartlett had been murdered.

Welcome to Mexican Politics.

There are so many examples of people in Mexico who have the mentality of the PRI/Government-did-it-and-there's-nothing-we-can-do-to-hold-them-accountable-oh-well-life-goes-on.

But telling the truth would mean Munoz Ledo would have to grapple with a controversy from the very start of his term, and the prospect of that hanging over him, defining his image, presidency and legacy would surely spook him… so I'm not surprised he'd go along with a desperate gambit. He's looking for some semblance of stability, but unfortunately what he's chosen will certainly lead to more instability in the future.

I must admit that I don't feel so enthusiastic about this part of the story.

It seems so... exaggeratedly incompetent?

I thought that Muñoz Ledo would break the news and begin a transparent investigation. To me, it would have been more interesting if the reader knows that while Muñoz Ledo and the government are actually innocent of Bartlett Díaz' death, the people don't believe it. This causes an ever-present cloud of suspicion on Muñoz Ledo no matter what he does. It's a more accurate reflection of how transfers of power occur in failed states and how it could feed into the idea of Meet the New Boss, Same as the Old Boss.

Then again, I'm not writing the story, so we'll see how it goes.

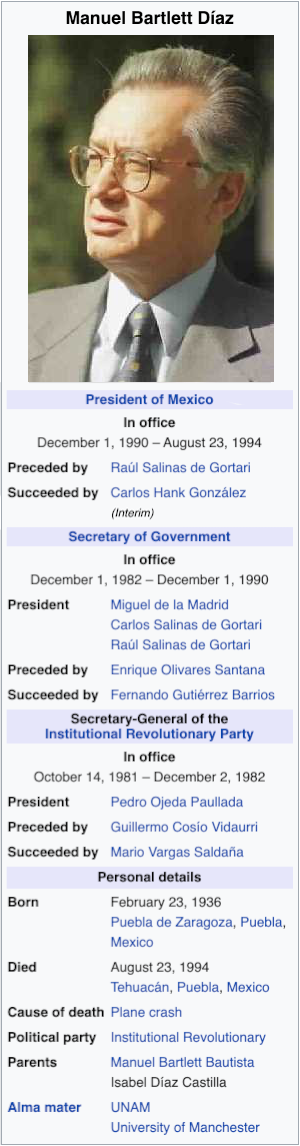

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González

In the early morning of August 23, 1994, the people of Tehuacán bore witness to one of the only high-speed chases in the history of Mexican aviation.

By then, residents of this mid-sized municipality in southwest Puebla had already heard that President Bartlett had mysteriously disappeared from Los Pinos. But no one could quite agree on where exactly he had gone. Many residents of Tehuacán had traveled to Mexico City to take part in the post-election celebrations, and when they returned, they brought back rumors ranging from the plausible to the preposterous: Bartlett had either fled the country, or he’d been executed by the Army, or he’d retreated into a secret, underground lair where he was currently scheming to take back power in a military coup, or he’d been ritually sacrificed by his reptilian overlords as punishment for his loss.

It had been a slow night at Tlaxcala Air Force Base. Really, every night was a slow night at Tlaxcala Air Force Base—it had started out as a civilian airport, but it had seen so little air traffic that in 1993 the state government had sold it to the Secretariat of National Defense. [1] During the cartels’ heyday, quite a few reconnaissance flights had taken off from Tlaxcala, but shipments along the Tabasco-Morelos route had slowed to a molasses grind since the eruption of the drug war up north, and these days, the base was seeing about as much action on a typical day as a fur coat shop in Cancun. Anything appearing on the radar screens after midnight would have been a notable occurrence, but when the Defense Secretariat ordered on August 22 that all flights be grounded until Manuel Bartlett had been apprehended, it would have been national news. The control staff at Tlaxcala’s tower were, therefore, quite surprised to see a tiny blip streaking through the middle of their radar screens around 4:41 AM, having just passed the great peak of Popocatépetl and now speeding east-by-south across the valley of central Puebla. The controllers promptly alerted their superiors, and within twenty minutes, a pair of Northrop F-5 fighter jets from Santa Lucía Air Force Base found themselves two miles above the city of Tehuacán, tailing a twin-engine Cessna 402, through the dim morning sky.

What exactly happened next is a matter of contention. According to half a dozen separate government reports, the Cessna ignored multiple clear orders from the Northrops to land at Tehuacán’s Airport, leaving the fighter pilots no other choice but to use their weapons. In his Congressional testimony, one pilot claimed to have warned the Cessna via radio as many as nine separate times before firing, a number which was eventually substantiated by Tlaxcala air traffic control staff (reportedly after a small bit of “confusion” with some higher-ranked officers). Some eyewitnesses disputed this claim, contending that the Northrops had trailed the Cessna for at most thirty or forty seconds, nowhere near long enough for the pilots to have issued so many warnings; Air Force spokesmen countered by claiming that the early morning sky was too dark for anyone on the ground to clearly make out which plane was where and for how long, and that the scene in the air likely wouldn’t have attracted much attention until just seconds before the shooting started.

What exactly happened next is a matter of contention. According to half a dozen separate government reports, the Cessna ignored multiple clear orders from the Northrops to land at Tehuacán’s Airport, leaving the fighter pilots no other choice but to use their weapons. In his Congressional testimony, one pilot claimed to have warned the Cessna via radio as many as nine separate times before firing, a number which was eventually substantiated by Tlaxcala air traffic control staff (reportedly after a small bit of “confusion” with some higher-ups in the Secretariat). Some eyewitnesses disputed this claim, contending that the Northrops had trailed the Cessna for at most thirty or forty seconds, nowhere near long enough for the pilots to have issued so many warnings; Air Force spokesmen countered by claiming that the early morning sky was too dark for anyone on the ground to clearly make out which plane was where and for how long, and that the scene in the air likely wouldn’t have attracted much attention until just seconds before the shooting started.

What no one disputes is that at approximately 5:03 AM, one of the Northrops let loose a volley from one of its M39 cannons. The shells missed, and the pilot of the Cessna started maneuvering around wildly, apparently to evade more gunfire. By 5:06, several hundred tehuacanenses awoken by the sound of explosions in the sky had rushed out onto the streets, just in time to watch the other Northrop fire upon the Cessna. This one found its target, and the bullets ripped apart the Cessna’s tail, tore through the left side of the fuselage, and destroyed the left engine. The pilot banked rightward in a desperate attempt to reach the Tehuacán airstrip, but his efforts were in vain: the small aircraft crashed on a dusty hillside almost three miles short of its goal. Paramedics arrived within half an hour, but found only the corpses of the pilot and the passenger—the latter of whom, despite considerable damage from the crash, was still clearly, unmistakably identifiable as Manuel Bartlett Díaz, the late President of Mexico.

Although President Bartlett’s plane was shot down, several other planes in the sky that night were intercepted by the Air Force and escorted to safe landings. For those who believe that Bartlett’s plane was not given adequate warning before being destroyed, this also means that the Air Force somehow knew that Bartlett would be on this particular plane, which is arguably an even scarier thought.

The crash was national news by midmorning. After enduring six years of iron-fisted authoritarianism, most Mexicans were so happy to hear Bartlett was dead that they didn’t care how exactly it had happened—in Mexico City, people took to the streets once again to chant “¡arriba, abajo, Bartlett se va al carajo!”, and actress Sherlyn González would later recall seeing her seventy-seven-year-old great-grandfather, who couldn’t walk without the help of a cane, do a celebratory handstand when Bartlett’s death was announced on the radio. But some Mexicans weren’t satisfied with the government’s version of things. The official line was that, fearing punishment for his many crimes against the Mexican people, Bartlett had called in one last favor with his trafficker buddies and tried to flee the country on one of Amado Carrillo’s old cocaine planes. When this scheme was foiled, the Army said, Bartlett had chosen to die on his own terms (and take some poor cartel schmuck with him) rather than surrender to the forces of opposition. But a vocal minority suspected that the Army establishment had killed Bartlett in order to prevent him from going on trial and implicating them in his conspiracies. Some even went so far as to claim that Porfirio Muñoz Ledo himself had approved of the scheme, either to hasten his accession to the presidency or to cover-up his own supposed involvement in Carrillogate.

Time seems to have shown that there is indeed something more to the story than was said at the time. In 2005, one of the fighter pilots claimed to the newspaper El Nuevo Siglo that he had issued only three verbal warnings to the Cessna, not nine. Five years after that, El Universal published an anonymous interview with a man claiming to be a retired Air Force officer, who stated that he had personally escorted then-President-elect Porfirio Muñoz Ledo into an interrogation room at Zumpango Air Force Base to speak with Bartlett the night before his death. Several conspiracy theories have also cropped up regarding the identity of the pilot—while the Army claims never to have identified the body, in 1999, the family of Luca Hernández Barragán, an Air Force lieutenant whom the Army claimed had been killed in an ambush by the Carrillo cartel in Sinaloa, publicly announced their belief that he, in fact, had been flying the plane, and that the Air Force top brass had killed him and covered up his involvement. To this day, the Army denies all such claims and theories, but its sordid record of conduct since 1994 has done little to shore up its credibility.

The popularity of such theories has grown in recent years with the rise of the internet and social media. In 2015, an anonymous, hour-long “documentary” alleging that General Gutiérrez, Muñoz Ledo and other figures had plotted Bartlett’s death amassed over 24 million views on CoffeeShop before being taken down on defamation claims. This documentary helped give rise to Yggdrasil, a conspiracy theory which accuses Muñoz Ledo, the Mercer, Slim, and Salinas families, former President Huntsman, and various other rich and powerful entities of colluding to kill Bartlett as part of an ongoing plot to assume monopolistic control of the world’s oil supplies. A 2018 poll by the market research firm GEA-ISA suggested that almost a third of adult Mexicans doubt or disbelieve the official account of Manuel Bartlett’s death, and a few state and federal politicians have been so bold as to express their doubts in their election campaigns. These controversies remain one of the few black spots on Porfirio Muñoz Ledo’s historical reputation—although no concrete evidence has emerged to implicate the former President in any kind of cover-up or subterfuge, many suspect him of at least a certain level of involvement. Even today, more than twenty years after his retirement, it seems the distinguished elder statesman, revered for all his other deeds and accomplishments, still can’t make a public appearance without being dogged by quiet whispers of “Bartlett didn’t kill himself”.

Still, for all the questions and controversies, one thing above all was certain: Manuel Bartlett—Mexico’s longest-serving Government Secretary, its most tyrannical President since Porfirio Díaz, the man who had destroyed his party in a quixotic crusade to save it—was dead.

Under the old Constitution, when the President died, the Secretary of Government would assume his powers until such time as the Congress of the Union could convene to name a permanent replacement. So when Bartlett’s corpse was identified amid the crumpled metal of his wrecked airplane, the acting presidency officially fell to the only priísta in Mexico who was more hardline and authoritarian than Bartlett himself: Carlos Hank González. After decades spend advising, influencing, brown-nosing and blackmailing president after president, el profesor finally (if briefly) had the title for himself. This news terrified the international community—just two days earlier, the world had been celebrating the PRI’s landslide defeat, and now they were panicking at the news that Bartlett was dead and Carlos Hank González, the Himmler to Bartlett’s Hitler, had somehow acquired the presidency for himself.

There was really no reason to worry—Hank would spend his week-and-a-half-long “presidency” under house arrest, and the Army kept such a tight watch on him that he later complained that he couldn’t even take a piss in his own bathroom without a soldier following him inside. Yet Porfirio Muñoz Ledo would later reveal that he was more anxious during this brief period than he had ever been in his life. He knew that he needed to legitimize his authority as soon as possible, but for that, he would have to wait until the new, opposition-controlled Congress convened on September 1 to formally appoint him President. This left Mexico in constitutional limbo, a ten-day window in which the legitimate president had no power and the powerful president had no legitimacy. It was the perfect moment for everything to go terribly, horribly wrong—a counter-revolution by shadowy elements of the PRI old guard, an armed rebellion by a resurrected ELM, popular demonstrations leading to full-scale riots in the streets as in 1988, or perhaps just a general descent into anarchy and madness. Muñoz Ledo was very aware of this danger, and yet he also understood that he couldn’t rely too heavily on the Army to maintain control in case things got bad, because any hint of authoritarianism would have tainted his presidency from the start. His only option (or so he claimed in his memoirs) was to put his faith in the people who had elected him.

So, on August 25, 1994, Muñoz Ledo gave his first public speech as President-elect. Dutifully broadcast by both Televisa and TV Azteca, he addressed himself directly to the Mexican people, urging them to finish up their celebrations, return to their families and get on with their lives as best they could. He went out of his way to stress that this was a request and not a order, and that his listeners were not bound to follow it by anything more than their sense of civic duty: “The Constitution guarantees every Mexican the right of peaceful assembly,” he noted, “and I will not ask the Army to physically prevent anyone from exercising that right, nor will I seek to punish or prosecute those who do.” But even though Bartlett’s misdeeds had turned Mexico into a pariah state, Muñoz Ledo informed his listeners that right now, the eyes of the world were upon them. “For the past five years,” he orated, reading words written for him by the leftist writer Carlos Monsiváis, “oppressed peoples everywhere have been rising up to break the chains of tyranny. Humanity is seeing an unprecedented wave of revolutions and democratization. All over the world, dictatorial regimes are being swept away as their populations rise up to demand their liberty. In some places—in South Africa, in Poland, in the Philippines, in Mongolia—the people have already triumphed over tyranny. But in other places, they struggle still to make their voices heard. At this moment, they are watching you with great anticipation. The decisions you make over the coming days will have a crucial effect on the future of democracy, not just in our country but everywhere on Earth. If the next week sees peace and tranquility followed by an orderly transition of government, our comrades in foreign nations will strengthen their resolve to fight for freedom. But if lawlessness is permitted to prevail on our streets, as it has on several occasions over the previous several years, then they will hesitate before testing out their civil powers, and their oppressors will have yet another excuse to keep them in bondage.”

"I emphasize once again that this is not an order," he demurred. “I ask this of you not as a ruler commanding his subjects, but as a citizen imploring his compatriots. Your liberty in this matter is enshrined in the Constitution, and it is not mine to grant or revoke. But even if I possessed such a power, I would never use it. I would never need to use it. The bedrock of democracy is the wisdom of the people,” he concluded, “and I have a deep, abiding faith that the people will make the right choice.”

Some said it was the strength of Monsiváis’s words, some said it was a general feeling of goodwill (still untainted by theories about Bartlett’s death), others said they were just tired out after months and months of riots and protests and rallies and celebrations. Whatever the reason, the end of August was the most peaceful week Mexico had seen in a very long time. By August 27, the Zócalo was almost serene, and the calles of Guadalajara, Villahermosa and Veracruz were empty except for the trash and beer bottles left behind by the departed revelers. General Gutiérrez still insisted on stationing token garrisons in a few of the large cities, but the soldiers complained more about the threat posed by boredom than by rioters.

Porfirio Muñoz Ledo’s oratorical skills were among the strongest of any politician, and he would use them to his advantage in shoring up his credibility with the public.

Perhaps the least tranquil man in Mexico during this time was Porfirio Muñoz Ledo himself. Although he had secured civil order at home, he knew that he still had mountains of work to do if he wanted to restore Mexico’s place in the world and win back the trust of the international community. So, while the Mexican people went home for a well-deserved break from politics, the President-in-all-but-name had already moved into Los Pinos, where he and his not-quite-yet-official Government Secretary, Jorge Carpizo MacGregor (the ex-rector of the UNAM who had defected to the PAN way back in 1988, after De la Madrid ordered the Army to storm his campus) worked twenty-hour shifts with a small army of aides and advisors, scanning endless documents and reports, meeting with financial analysts, constitutional lawyers, senior bureaucrats and ambassadors, and making phone call after phone call to governors, mayors, and newly-elected members of Congress, working frantically to fill the power vacuum left behind by the late autocrat Bartlett.

Meanwhile, Muñoz Ledo’s other advisors were hard at work shoring up his image abroad. On August 24, Jorge Castañeda, Muñoz Ledo’s campaign manager and not-quite-yet-official Ambassador to the United States, was sent to Washington to establish a strong rapport with the White House (and to put paid to any false notions regarding the exact circumstances of Bartlett’s demise), before jet-setting off to do the same in the capitals of Mexico’s next-largest trading partners. Adolfo Aguilar Zínser, Muñoz Ledo’s closest confidant on international affairs and not-yet-official Foreign Secretary, spent days on the phone with Mexico’s embassies in Asia, Europe, and South America, informing the diplomatic staff that if they wanted to keep their jobs, they would inform their host governments that the PRI was well and truly out of power, and that Muñoz Ledo had the country firmly under control.

Finally, on September 1, the first opposition-controlled Congress in more than a century convened at the National Medical Center (the Legislative Palace was still a charred, decaying husk because, in the six years since it burned down, Manuel Bartlett had never quite managed to find the money to rebuild it). Although the opposition caucus was an ideological smorgasbord, its members were unanimous as to their first three priorities: bring both houses of Congress into session, elect presiding officers, and appoint Porfirio Muñoz Ledo as President of the Republic, while adhering as closely as possible to the Congress’s established procedures. But when they examined the Congress’s rulebook, they found, quite simply, that there were no established procedures. The rules of both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies had been written under the assumption that the PRI would hold onto power until the end of time, and that all important decisions would be made in backrooms by PRI power brokers. In fact, the deputies soon realized, without a PRI majority, it was technically impossible to bring either chamber into session. So before they could do anything, the opposition parties would have to come together and write entirely new rules from scratch.

Eventually, after seven hours of rule-writing, at 5:25 PM, the LVI Legislature of the Congress of the Union was called into session. Sergio Aguayo—newly elected as a PAN deputy from Guadalajara—was named President of the Chamber of Deputies by a margin of 451 to 12, while the Senate chose Mexico City senator Pablo Gómez (a former Trotskyist who had participated in the student protests of 1968) as its President by a similar margin. Then, cramming themselves into a college auditorium built for geriatrics students, the assembled Congressmen fulfilled their duties under Article 84 of the Constitution and officially appointed Porfirio Muñoz Ledo President of Mexico. The new President raised his arm and dutifully recited the oath of office. Then he shuffled off the podium, got into his motorcade and jetted right back to Los Pinos without so much as a gracias. When questioned afterwards about the brevity of the ceremony, journalist and PAN deputy Julio Scherer stated simply that “there is too much to do”.

And indeed there was. First, there was a significant Constitutional hurdle to overcome: since Muñoz Ledo had been appointed to fill the vacancy left by Bartlett’s death, he was technically serving as an “interim President”, which meant he would be constitutionally barred from being sworn in for a full term in December. So by the time Muñoz Ledo stepped off the stage, Gómez and Aguayo had already begun drawing up procedures for a new constitutional amendment. And as the new President sat down in his limousine, he was already busy appointing his cabinet. In order to secure PAN support for his candidacy, Muñoz Ledo had promised the party leadership that he would incorporate several panistas into his administration, and he kept his promise. Most of these appointments went to the party's northern, conservative old guard: Santiago Creel—accomplished lawyer, scion of the PAN’s prominent Creel-Terrazas dynasty, and longtime friend of Castañeda and Zínser—was tapped as Muñoz Ledo’s Attorney General, his cousin Francisco Barrio Terrazas—businessman and two-time candidate for Governor of Chihuahua—was named the Secretary of Communication, while Manuel Clouthier, the vegetable rancher and former presidential nominee, became Secretary of Agriculture. But the President also made sure to include members of the PAN’s progressive, pro-labor nouveau riche, which was rooted in the FAT and other independent labor federations and which shared Muñoz Ledo’s own social-democratic instincts. So in addition to naming PAN newcomer Jorge Carpizo MacGregor as Secretary of Government, Muñoz Ledo found his Labor Secretary in Arturo Alcalde Justiniani. A seasoned labor lawyer and a longtime associate of the FAT, Alcalde had spent more than twenty years doing battle with PRI-controlled labor tribunals and knew Mexico’s corrupt, broken labor system inside and out, making him the perfect man to carry out Muñoz Ledo’s ambitious plans for labor reform.

In 1974, then-Labor Secretary Porfirio Muñoz Ledo had granted a charter to one of Mexico’s only independent unions thanks to the untiring efforts of labor lawyer Arturo Alcalde. Twenty years later, Muñoz Ledo recruited Alcalde to help him clean up and democratize the labor sector.

For two of the positions, Muñoz Ledo took the highly controversial step of reappointing former PRI cabinet members to their old jobs. For all that the PRI of the 1990s was a gerontocratic cesspool of corruption and sleaze, some of Mexico’s most competent financial analysts and civil servants were PRI members, and Muñoz Ledo desperately needed their expertise to untangle the financial spiderweb which had ensnared his administration. First was Pedro Aspe Armella, an urbane and charismatic economist with a wide network of contacts within the world’s most powerful financial institutions. As Finance Secretary, Aspe had successfully persuaded Mexico’s foreign creditors to forgive over $15 billion of debt following Carlos Salinas’s assassination. Faced now with a national debt of over $37 billion, Muñoz Ledo knew he’d need Aspe’s negotiating prowess on his side if he had any hope of bringing Mexico back from the brink of insolvency. The same logic led him to appoint Ernesto Zedillo as his Budget Secretary—although Zedillo’s straight-arrow conservatism clashed with Muñoz Ledo’s tax-and-spend agenda, he was perhaps the only man with the necessary fiscal skill to produce something approaching a sound budget. As the only competent man to serve as Budget Secretary in the previous decade, Zedillo also had the unquestioned respect of the Budget Secretariat’s senior civil servants, and any question over his loyalty was mooted when it was revealed that he had been the whistleblower who had first leaked the evidence of Carrillogate to the press.

Muñoz Ledo’s last two major appointments were more for popularity than anything else: Jesus Gutiérrez Rebollo (still Mexico’s most popular soldier) as Secretary of Defense, and none other than Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas himself as Mayor of Mexico City. Having suffered not only his wife’s murder, but also a close brush with death himself at the Palenque Summit in 1991, it took some serious persuasion to get him to accept a job where he might once again be exposed to violence. But it was worth it in the end. No other politician was held in such high esteem by the people of Mexico City than Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas—his speech in the Zócalo in 1988 had sparked Mexico’s long, painful transition to democracy, and his leadership would help stabilize the capital city while Muñoz Ledo worked to extend his credibility and authority over the rest of the country.

Having appointed his dream team, the new President didn’t waste a single second. George Bush, talking through ambassador Castañeda, had already relayed to Muñoz Ledo his two preconditions for the lifting of the ROGUE STATES Act sanctions: public prosecution of at least some of the PRI officials who had been involved in the drug trade, and an effective dismantling of the DFS as an armed force. No sooner had Acting President Hank been relieved of his position than he was charged by Attorney General Creel with murder, conspiracy, drug trafficking, corruption, racketeering, jaywalking, and just about every other no-no in the criminal code. Hank’s trial was broadcast live on both Televisa and TV Azteca, to cathartic effect. As a constant carousel of witnesses—political dissidents, bureaucratic schmucks, PRI moderates, low-level cartel errand-boys—took the stand to reveal the pain they’d endured at the hands of Hank’s Government Secretariat, as well as the so-called Office of Political Integrity, the Mexican people were glad to see a PRI tyrant finally get held accountable for his crimes. And while the soon-to-be established Commission on Truth and Reconciliation would dig up dirt on hundreds more PRI officials, many analysts see Hank’s trial as a stroke of particular genius: by aggressively prosecuting Hank not just for corruption and authoritarianism, but also for his ideological purity crusades against PRI members, Muñoz Ledo sent a message to moderate priístas in Congress and the bureaucracy that the days of rigid party orthodoxy were over, and that they would have nothing to fear from defying the party line to support his administration.

After two months of testimonies and recriminations, Chief Justice Olga Sanchez Cordero decided she’d heard enough. On November 15, former Acting President Hank was indicted on twelve counts of murder, twenty-six counts of torture, and dozens of other charges, and was sentenced to life in prison without parole. By the end of the year, he had moved into a private cell at Islas Marías Federal Prison in the state of Nayarit (where he would spend just under six years before dying of an arterial embolism), and many other high-ranking officials would follow him over the next few months.

That satisfied President Bush’s first condition. But the second condition—dismantling the DFS—was going to be trickier. It wasn’t as simple as just disbanding the agency with the stroke of a pen. Manuel Bartlett himself had done that under U.S. pressure back in 1986, and all it had done was free up 1,500 corrupt agents to devote their talents full-time to the drug trade. Luckily, this time, Muñoz Ledo had a secret weapon on his side: the Army. Defense Secretary Gutiérrez Rebollo’s war on the remnants of the DFS was dazzlingly quick and efficient. Even considering the fact that over 35% of the agency’s manpower had already been killed fighting opposite sides of the Caro-Carrillo drug war, the fact that Gutiérrez managed to round up over 1,200 rogue agents in three months is a testament to the sheer power of his organizing abilities. Most contemporary observers agree that he was just getting rid of the competition, but at the time, the crusade won him worldwide admiration as an incorruptible, ruthlessly effective man in uniform. By the time Porfirio Muñoz Ledo was sworn in for his full sexenio on December 1, the DFS’s entire presence had dwindled down to a few roving bands of mercenaries with a couple dozen men each, scattered across the border region without any organization. In a public ceremony two weeks later, Government Secretary Carpizo signed the documents which abolished the DFS and officially cut the corrupt, authoritarian tumor out of the Government Secretariat.

By the end of the year, Mexico had largely won back the trust of the world. Although a few contemporary leaders would later admit to having some doubts regarding the precise circumstances of Bartlett’s death, the international community could tell that the new administration represented a significant break with Bartlett’s leadership style, and much of the world was just happy enough to have sane leadership in Mexico City that they were willing to overlook such trivial matters for the time being. Mexico’s U.N. membership was restored in January of 1995, and during a state visit on January 16, President Bush announced to the world that all U.S. sanctions on Mexico would be lifted with immediate effect. The rest of the world followed suit, and by mid-April, the embargo had effectively been brought to an end. After enduring five different Presidents in as many years, followed by months of pariah status, the world was finally welcoming Mexico back with open arms.

But all was not well. While the embargo had been lifted, Muñoz Ledo had little hope of instituting any substantial fiscal reforms until the foreign debt was paid off—which, after five years of insolvency and financial mismanagement, had ballooned up to $35 billion. Aspe, Aguilar and Zedillo were hard at work trying to bring that number down, but Muñoz Ledo knew he wouldn’t be able to pay off much of anything without tapping into Mexico’s vast oil reserves, and for that, there was one huge obstacle in his way: the oil workers’ union. Way back in 1988, Miguel de la Madrid had tried to use oil money to pay off Mexico’s foreign debt. In response, the Petroleum Workers’ Syndicate, led by labor boss Joaquín “La Quina” Hernández Galicia, had gone on strike and annihilated the national economy. After that, de la Madrid, the Salinas brothers, and Manuel Bartlett had spent the following few years tripping over themselves granting favors and concessions to keep the oil workers happy. If the union had been corrupt before the strike, by 1995, it was a septic tank of graft and bribery with practically no state oversight and no safeguards against fraud and outright thievery. With La Quina’s parasitic web of patronage sucking up most of Pemex’s profits, scraping together enough oil money to pay off the debt would be about as easy as emptying the Gulf of Mexico with a cheesecloth. And if Muñoz Ledo attempted to reassert any form of government oversight over the use of the oil funds, La Quina might lead his workers back on strike and destroy any chance of a stable economic recovery. As negotiations with La Quina bore little fruit and IMF officials bristled at the thought of forgiving any more of Mexico’s debt without something solid as collateral, President Muñoz Ledo started to worry he might never find a way to pay off the debt without straight-up selling Chihuahua to Texas.

By his own account, on March 3, he was sitting in his office, idly considering trying to get Governor Richards on the phone, when a tragedy struck which, though it killed hundreds of Mexicans, would be the key to improving the lives of millions more.

[1] This sale happened in 1997 in OTL, but Mexico's increased militarization, coupled with the intensified drug war and a larger role for the Air Force in the Zapatista uprising, has prompted the Secretariat of National Defense to buy the base a few years earlier.

By then, residents of this mid-sized municipality in southwest Puebla had already heard that President Bartlett had mysteriously disappeared from Los Pinos. But no one could quite agree on where exactly he had gone. Many residents of Tehuacán had traveled to Mexico City to take part in the post-election celebrations, and when they returned, they brought back rumors ranging from the plausible to the preposterous: Bartlett had either fled the country, or he’d been executed by the Army, or he’d retreated into a secret, underground lair where he was currently scheming to take back power in a military coup, or he’d been ritually sacrificed by his reptilian overlords as punishment for his loss.

It had been a slow night at Tlaxcala Air Force Base. Really, every night was a slow night at Tlaxcala Air Force Base—it had started out as a civilian airport, but it had seen so little air traffic that in 1993 the state government had sold it to the Secretariat of National Defense. [1] During the cartels’ heyday, quite a few reconnaissance flights had taken off from Tlaxcala, but shipments along the Tabasco-Morelos route had slowed to a molasses grind since the eruption of the drug war up north, and these days, the base was seeing about as much action on a typical day as a fur coat shop in Cancun. Anything appearing on the radar screens after midnight would have been a notable occurrence, but when the Defense Secretariat ordered on August 22 that all flights be grounded until Manuel Bartlett had been apprehended, it would have been national news. The control staff at Tlaxcala’s tower were, therefore, quite surprised to see a tiny blip streaking through the middle of their radar screens around 4:41 AM, having just passed the great peak of Popocatépetl and now speeding east-by-south across the valley of central Puebla. The controllers promptly alerted their superiors, and within twenty minutes, a pair of Northrop F-5 fighter jets from Santa Lucía Air Force Base found themselves two miles above the city of Tehuacán, tailing a twin-engine Cessna 402, through the dim morning sky.

What exactly happened next is a matter of contention. According to half a dozen separate government reports, the Cessna ignored multiple clear orders from the Northrops to land at Tehuacán’s Airport, leaving the fighter pilots no other choice but to use their weapons. In his Congressional testimony, one pilot claimed to have warned the Cessna via radio as many as nine separate times before firing, a number which was eventually substantiated by Tlaxcala air traffic control staff (reportedly after a small bit of “confusion” with some higher-ranked officers). Some eyewitnesses disputed this claim, contending that the Northrops had trailed the Cessna for at most thirty or forty seconds, nowhere near long enough for the pilots to have issued so many warnings; Air Force spokesmen countered by claiming that the early morning sky was too dark for anyone on the ground to clearly make out which plane was where and for how long, and that the scene in the air likely wouldn’t have attracted much attention until just seconds before the shooting started.

What exactly happened next is a matter of contention. According to half a dozen separate government reports, the Cessna ignored multiple clear orders from the Northrops to land at Tehuacán’s Airport, leaving the fighter pilots no other choice but to use their weapons. In his Congressional testimony, one pilot claimed to have warned the Cessna via radio as many as nine separate times before firing, a number which was eventually substantiated by Tlaxcala air traffic control staff (reportedly after a small bit of “confusion” with some higher-ups in the Secretariat). Some eyewitnesses disputed this claim, contending that the Northrops had trailed the Cessna for at most thirty or forty seconds, nowhere near long enough for the pilots to have issued so many warnings; Air Force spokesmen countered by claiming that the early morning sky was too dark for anyone on the ground to clearly make out which plane was where and for how long, and that the scene in the air likely wouldn’t have attracted much attention until just seconds before the shooting started.

What no one disputes is that at approximately 5:03 AM, one of the Northrops let loose a volley from one of its M39 cannons. The shells missed, and the pilot of the Cessna started maneuvering around wildly, apparently to evade more gunfire. By 5:06, several hundred tehuacanenses awoken by the sound of explosions in the sky had rushed out onto the streets, just in time to watch the other Northrop fire upon the Cessna. This one found its target, and the bullets ripped apart the Cessna’s tail, tore through the left side of the fuselage, and destroyed the left engine. The pilot banked rightward in a desperate attempt to reach the Tehuacán airstrip, but his efforts were in vain: the small aircraft crashed on a dusty hillside almost three miles short of its goal. Paramedics arrived within half an hour, but found only the corpses of the pilot and the passenger—the latter of whom, despite considerable damage from the crash, was still clearly, unmistakably identifiable as Manuel Bartlett Díaz, the late President of Mexico.

Although President Bartlett’s plane was shot down, several other planes in the sky that night were intercepted by the Air Force and escorted to safe landings. For those who believe that Bartlett’s plane was not given adequate warning before being destroyed, this also means that the Air Force somehow knew that Bartlett would be on this particular plane, which is arguably an even scarier thought.

The crash was national news by midmorning. After enduring six years of iron-fisted authoritarianism, most Mexicans were so happy to hear Bartlett was dead that they didn’t care how exactly it had happened—in Mexico City, people took to the streets once again to chant “¡arriba, abajo, Bartlett se va al carajo!”, and actress Sherlyn González would later recall seeing her seventy-seven-year-old great-grandfather, who couldn’t walk without the help of a cane, do a celebratory handstand when Bartlett’s death was announced on the radio. But some Mexicans weren’t satisfied with the government’s version of things. The official line was that, fearing punishment for his many crimes against the Mexican people, Bartlett had called in one last favor with his trafficker buddies and tried to flee the country on one of Amado Carrillo’s old cocaine planes. When this scheme was foiled, the Army said, Bartlett had chosen to die on his own terms (and take some poor cartel schmuck with him) rather than surrender to the forces of opposition. But a vocal minority suspected that the Army establishment had killed Bartlett in order to prevent him from going on trial and implicating them in his conspiracies. Some even went so far as to claim that Porfirio Muñoz Ledo himself had approved of the scheme, either to hasten his accession to the presidency or to cover-up his own supposed involvement in Carrillogate.

Time seems to have shown that there is indeed something more to the story than was said at the time. In 2005, one of the fighter pilots claimed to the newspaper El Nuevo Siglo that he had issued only three verbal warnings to the Cessna, not nine. Five years after that, El Universal published an anonymous interview with a man claiming to be a retired Air Force officer, who stated that he had personally escorted then-President-elect Porfirio Muñoz Ledo into an interrogation room at Zumpango Air Force Base to speak with Bartlett the night before his death. Several conspiracy theories have also cropped up regarding the identity of the pilot—while the Army claims never to have identified the body, in 1999, the family of Luca Hernández Barragán, an Air Force lieutenant whom the Army claimed had been killed in an ambush by the Carrillo cartel in Sinaloa, publicly announced their belief that he, in fact, had been flying the plane, and that the Air Force top brass had killed him and covered up his involvement. To this day, the Army denies all such claims and theories, but its sordid record of conduct since 1994 has done little to shore up its credibility.

The popularity of such theories has grown in recent years with the rise of the internet and social media. In 2015, an anonymous, hour-long “documentary” alleging that General Gutiérrez, Muñoz Ledo and other figures had plotted Bartlett’s death amassed over 24 million views on CoffeeShop before being taken down on defamation claims. This documentary helped give rise to Yggdrasil, a conspiracy theory which accuses Muñoz Ledo, the Mercer, Slim, and Salinas families, former President Huntsman, and various other rich and powerful entities of colluding to kill Bartlett as part of an ongoing plot to assume monopolistic control of the world’s oil supplies. A 2018 poll by the market research firm GEA-ISA suggested that almost a third of adult Mexicans doubt or disbelieve the official account of Manuel Bartlett’s death, and a few state and federal politicians have been so bold as to express their doubts in their election campaigns. These controversies remain one of the few black spots on Porfirio Muñoz Ledo’s historical reputation—although no concrete evidence has emerged to implicate the former President in any kind of cover-up or subterfuge, many suspect him of at least a certain level of involvement. Even today, more than twenty years after his retirement, it seems the distinguished elder statesman, revered for all his other deeds and accomplishments, still can’t make a public appearance without being dogged by quiet whispers of “Bartlett didn’t kill himself”.

Still, for all the questions and controversies, one thing above all was certain: Manuel Bartlett—Mexico’s longest-serving Government Secretary, its most tyrannical President since Porfirio Díaz, the man who had destroyed his party in a quixotic crusade to save it—was dead.

Under the old Constitution, when the President died, the Secretary of Government would assume his powers until such time as the Congress of the Union could convene to name a permanent replacement. So when Bartlett’s corpse was identified amid the crumpled metal of his wrecked airplane, the acting presidency officially fell to the only priísta in Mexico who was more hardline and authoritarian than Bartlett himself: Carlos Hank González. After decades spend advising, influencing, brown-nosing and blackmailing president after president, el profesor finally (if briefly) had the title for himself. This news terrified the international community—just two days earlier, the world had been celebrating the PRI’s landslide defeat, and now they were panicking at the news that Bartlett was dead and Carlos Hank González, the Himmler to Bartlett’s Hitler, had somehow acquired the presidency for himself.

There was really no reason to worry—Hank would spend his week-and-a-half-long “presidency” under house arrest, and the Army kept such a tight watch on him that he later complained that he couldn’t even take a piss in his own bathroom without a soldier following him inside. Yet Porfirio Muñoz Ledo would later reveal that he was more anxious during this brief period than he had ever been in his life. He knew that he needed to legitimize his authority as soon as possible, but for that, he would have to wait until the new, opposition-controlled Congress convened on September 1 to formally appoint him President. This left Mexico in constitutional limbo, a ten-day window in which the legitimate president had no power and the powerful president had no legitimacy. It was the perfect moment for everything to go terribly, horribly wrong—a counter-revolution by shadowy elements of the PRI old guard, an armed rebellion by a resurrected ELM, popular demonstrations leading to full-scale riots in the streets as in 1988, or perhaps just a general descent into anarchy and madness. Muñoz Ledo was very aware of this danger, and yet he also understood that he couldn’t rely too heavily on the Army to maintain control in case things got bad, because any hint of authoritarianism would have tainted his presidency from the start. His only option (or so he claimed in his memoirs) was to put his faith in the people who had elected him.

So, on August 25, 1994, Muñoz Ledo gave his first public speech as President-elect. Dutifully broadcast by both Televisa and TV Azteca, he addressed himself directly to the Mexican people, urging them to finish up their celebrations, return to their families and get on with their lives as best they could. He went out of his way to stress that this was a request and not a order, and that his listeners were not bound to follow it by anything more than their sense of civic duty: “The Constitution guarantees every Mexican the right of peaceful assembly,” he noted, “and I will not ask the Army to physically prevent anyone from exercising that right, nor will I seek to punish or prosecute those who do.” But even though Bartlett’s misdeeds had turned Mexico into a pariah state, Muñoz Ledo informed his listeners that right now, the eyes of the world were upon them. “For the past five years,” he orated, reading words written for him by the leftist writer Carlos Monsiváis, “oppressed peoples everywhere have been rising up to break the chains of tyranny. Humanity is seeing an unprecedented wave of revolutions and democratization. All over the world, dictatorial regimes are being swept away as their populations rise up to demand their liberty. In some places—in South Africa, in Poland, in the Philippines, in Mongolia—the people have already triumphed over tyranny. But in other places, they struggle still to make their voices heard. At this moment, they are watching you with great anticipation. The decisions you make over the coming days will have a crucial effect on the future of democracy, not just in our country but everywhere on Earth. If the next week sees peace and tranquility followed by an orderly transition of government, our comrades in foreign nations will strengthen their resolve to fight for freedom. But if lawlessness is permitted to prevail on our streets, as it has on several occasions over the previous several years, then they will hesitate before testing out their civil powers, and their oppressors will have yet another excuse to keep them in bondage.”

"I emphasize once again that this is not an order," he demurred. “I ask this of you not as a ruler commanding his subjects, but as a citizen imploring his compatriots. Your liberty in this matter is enshrined in the Constitution, and it is not mine to grant or revoke. But even if I possessed such a power, I would never use it. I would never need to use it. The bedrock of democracy is the wisdom of the people,” he concluded, “and I have a deep, abiding faith that the people will make the right choice.”

Some said it was the strength of Monsiváis’s words, some said it was a general feeling of goodwill (still untainted by theories about Bartlett’s death), others said they were just tired out after months and months of riots and protests and rallies and celebrations. Whatever the reason, the end of August was the most peaceful week Mexico had seen in a very long time. By August 27, the Zócalo was almost serene, and the calles of Guadalajara, Villahermosa and Veracruz were empty except for the trash and beer bottles left behind by the departed revelers. General Gutiérrez still insisted on stationing token garrisons in a few of the large cities, but the soldiers complained more about the threat posed by boredom than by rioters.

Porfirio Muñoz Ledo’s oratorical skills were among the strongest of any politician, and he would use them to his advantage in shoring up his credibility with the public.

Perhaps the least tranquil man in Mexico during this time was Porfirio Muñoz Ledo himself. Although he had secured civil order at home, he knew that he still had mountains of work to do if he wanted to restore Mexico’s place in the world and win back the trust of the international community. So, while the Mexican people went home for a well-deserved break from politics, the President-in-all-but-name had already moved into Los Pinos, where he and his not-quite-yet-official Government Secretary, Jorge Carpizo MacGregor (the ex-rector of the UNAM who had defected to the PAN way back in 1988, after De la Madrid ordered the Army to storm his campus) worked twenty-hour shifts with a small army of aides and advisors, scanning endless documents and reports, meeting with financial analysts, constitutional lawyers, senior bureaucrats and ambassadors, and making phone call after phone call to governors, mayors, and newly-elected members of Congress, working frantically to fill the power vacuum left behind by the late autocrat Bartlett.

Meanwhile, Muñoz Ledo’s other advisors were hard at work shoring up his image abroad. On August 24, Jorge Castañeda, Muñoz Ledo’s campaign manager and not-quite-yet-official Ambassador to the United States, was sent to Washington to establish a strong rapport with the White House (and to put paid to any false notions regarding the exact circumstances of Bartlett’s demise), before jet-setting off to do the same in the capitals of Mexico’s next-largest trading partners. Adolfo Aguilar Zínser, Muñoz Ledo’s closest confidant on international affairs and not-yet-official Foreign Secretary, spent days on the phone with Mexico’s embassies in Asia, Europe, and South America, informing the diplomatic staff that if they wanted to keep their jobs, they would inform their host governments that the PRI was well and truly out of power, and that Muñoz Ledo had the country firmly under control.

Finally, on September 1, the first opposition-controlled Congress in more than a century convened at the National Medical Center (the Legislative Palace was still a charred, decaying husk because, in the six years since it burned down, Manuel Bartlett had never quite managed to find the money to rebuild it). Although the opposition caucus was an ideological smorgasbord, its members were unanimous as to their first three priorities: bring both houses of Congress into session, elect presiding officers, and appoint Porfirio Muñoz Ledo as President of the Republic, while adhering as closely as possible to the Congress’s established procedures. But when they examined the Congress’s rulebook, they found, quite simply, that there were no established procedures. The rules of both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies had been written under the assumption that the PRI would hold onto power until the end of time, and that all important decisions would be made in backrooms by PRI power brokers. In fact, the deputies soon realized, without a PRI majority, it was technically impossible to bring either chamber into session. So before they could do anything, the opposition parties would have to come together and write entirely new rules from scratch.

Eventually, after seven hours of rule-writing, at 5:25 PM, the LVI Legislature of the Congress of the Union was called into session. Sergio Aguayo—newly elected as a PAN deputy from Guadalajara—was named President of the Chamber of Deputies by a margin of 451 to 12, while the Senate chose Mexico City senator Pablo Gómez (a former Trotskyist who had participated in the student protests of 1968) as its President by a similar margin. Then, cramming themselves into a college auditorium built for geriatrics students, the assembled Congressmen fulfilled their duties under Article 84 of the Constitution and officially appointed Porfirio Muñoz Ledo President of Mexico. The new President raised his arm and dutifully recited the oath of office. Then he shuffled off the podium, got into his motorcade and jetted right back to Los Pinos without so much as a gracias. When questioned afterwards about the brevity of the ceremony, journalist and PAN deputy Julio Scherer stated simply that “there is too much to do”.

And indeed there was. First, there was a significant Constitutional hurdle to overcome: since Muñoz Ledo had been appointed to fill the vacancy left by Bartlett’s death, he was technically serving as an “interim President”, which meant he would be constitutionally barred from being sworn in for a full term in December. So by the time Muñoz Ledo stepped off the stage, Gómez and Aguayo had already begun drawing up procedures for a new constitutional amendment. And as the new President sat down in his limousine, he was already busy appointing his cabinet. In order to secure PAN support for his candidacy, Muñoz Ledo had promised the party leadership that he would incorporate several panistas into his administration, and he kept his promise. Most of these appointments went to the party's northern, conservative old guard: Santiago Creel—accomplished lawyer, scion of the PAN’s prominent Creel-Terrazas dynasty, and longtime friend of Castañeda and Zínser—was tapped as Muñoz Ledo’s Attorney General, his cousin Francisco Barrio Terrazas—businessman and two-time candidate for Governor of Chihuahua—was named the Secretary of Communication, while Manuel Clouthier, the vegetable rancher and former presidential nominee, became Secretary of Agriculture. But the President also made sure to include members of the PAN’s progressive, pro-labor nouveau riche, which was rooted in the FAT and other independent labor federations and which shared Muñoz Ledo’s own social-democratic instincts. So in addition to naming PAN newcomer Jorge Carpizo MacGregor as Secretary of Government, Muñoz Ledo found his Labor Secretary in Arturo Alcalde Justiniani. A seasoned labor lawyer and a longtime associate of the FAT, Alcalde had spent more than twenty years doing battle with PRI-controlled labor tribunals and knew Mexico’s corrupt, broken labor system inside and out, making him the perfect man to carry out Muñoz Ledo’s ambitious plans for labor reform.

In 1974, then-Labor Secretary Porfirio Muñoz Ledo had granted a charter to one of Mexico’s only independent unions thanks to the untiring efforts of labor lawyer Arturo Alcalde. Twenty years later, Muñoz Ledo recruited Alcalde to help him clean up and democratize the labor sector.

For two of the positions, Muñoz Ledo took the highly controversial step of reappointing former PRI cabinet members to their old jobs. For all that the PRI of the 1990s was a gerontocratic cesspool of corruption and sleaze, some of Mexico’s most competent financial analysts and civil servants were PRI members, and Muñoz Ledo desperately needed their expertise to untangle the financial spiderweb which had ensnared his administration. First was Pedro Aspe Armella, an urbane and charismatic economist with a wide network of contacts within the world’s most powerful financial institutions. As Finance Secretary, Aspe had successfully persuaded Mexico’s foreign creditors to forgive over $15 billion of debt following Carlos Salinas’s assassination. Faced now with a national debt of over $37 billion, Muñoz Ledo knew he’d need Aspe’s negotiating prowess on his side if he had any hope of bringing Mexico back from the brink of insolvency. The same logic led him to appoint Ernesto Zedillo as his Budget Secretary—although Zedillo’s straight-arrow conservatism clashed with Muñoz Ledo’s tax-and-spend agenda, he was perhaps the only man with the necessary fiscal skill to produce something approaching a sound budget. As the only competent man to serve as Budget Secretary in the previous decade, Zedillo also had the unquestioned respect of the Budget Secretariat’s senior civil servants, and any question over his loyalty was mooted when it was revealed that he had been the whistleblower who had first leaked the evidence of Carrillogate to the press.

Muñoz Ledo’s last two major appointments were more for popularity than anything else: Jesus Gutiérrez Rebollo (still Mexico’s most popular soldier) as Secretary of Defense, and none other than Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas himself as Mayor of Mexico City. Having suffered not only his wife’s murder, but also a close brush with death himself at the Palenque Summit in 1991, it took some serious persuasion to get him to accept a job where he might once again be exposed to violence. But it was worth it in the end. No other politician was held in such high esteem by the people of Mexico City than Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas—his speech in the Zócalo in 1988 had sparked Mexico’s long, painful transition to democracy, and his leadership would help stabilize the capital city while Muñoz Ledo worked to extend his credibility and authority over the rest of the country.

Having appointed his dream team, the new President didn’t waste a single second. George Bush, talking through ambassador Castañeda, had already relayed to Muñoz Ledo his two preconditions for the lifting of the ROGUE STATES Act sanctions: public prosecution of at least some of the PRI officials who had been involved in the drug trade, and an effective dismantling of the DFS as an armed force. No sooner had Acting President Hank been relieved of his position than he was charged by Attorney General Creel with murder, conspiracy, drug trafficking, corruption, racketeering, jaywalking, and just about every other no-no in the criminal code. Hank’s trial was broadcast live on both Televisa and TV Azteca, to cathartic effect. As a constant carousel of witnesses—political dissidents, bureaucratic schmucks, PRI moderates, low-level cartel errand-boys—took the stand to reveal the pain they’d endured at the hands of Hank’s Government Secretariat, as well as the so-called Office of Political Integrity, the Mexican people were glad to see a PRI tyrant finally get held accountable for his crimes. And while the soon-to-be established Commission on Truth and Reconciliation would dig up dirt on hundreds more PRI officials, many analysts see Hank’s trial as a stroke of particular genius: by aggressively prosecuting Hank not just for corruption and authoritarianism, but also for his ideological purity crusades against PRI members, Muñoz Ledo sent a message to moderate priístas in Congress and the bureaucracy that the days of rigid party orthodoxy were over, and that they would have nothing to fear from defying the party line to support his administration.

After two months of testimonies and recriminations, Chief Justice Olga Sanchez Cordero decided she’d heard enough. On November 15, former Acting President Hank was indicted on twelve counts of murder, twenty-six counts of torture, and dozens of other charges, and was sentenced to life in prison without parole. By the end of the year, he had moved into a private cell at Islas Marías Federal Prison in the state of Nayarit (where he would spend just under six years before dying of an arterial embolism), and many other high-ranking officials would follow him over the next few months.

That satisfied President Bush’s first condition. But the second condition—dismantling the DFS—was going to be trickier. It wasn’t as simple as just disbanding the agency with the stroke of a pen. Manuel Bartlett himself had done that under U.S. pressure back in 1986, and all it had done was free up 1,500 corrupt agents to devote their talents full-time to the drug trade. Luckily, this time, Muñoz Ledo had a secret weapon on his side: the Army. Defense Secretary Gutiérrez Rebollo’s war on the remnants of the DFS was dazzlingly quick and efficient. Even considering the fact that over 35% of the agency’s manpower had already been killed fighting opposite sides of the Caro-Carrillo drug war, the fact that Gutiérrez managed to round up over 1,200 rogue agents in three months is a testament to the sheer power of his organizing abilities. Most contemporary observers agree that he was just getting rid of the competition, but at the time, the crusade won him worldwide admiration as an incorruptible, ruthlessly effective man in uniform. By the time Porfirio Muñoz Ledo was sworn in for his full sexenio on December 1, the DFS’s entire presence had dwindled down to a few roving bands of mercenaries with a couple dozen men each, scattered across the border region without any organization. In a public ceremony two weeks later, Government Secretary Carpizo signed the documents which abolished the DFS and officially cut the corrupt, authoritarian tumor out of the Government Secretariat.

By the end of the year, Mexico had largely won back the trust of the world. Although a few contemporary leaders would later admit to having some doubts regarding the precise circumstances of Bartlett’s death, the international community could tell that the new administration represented a significant break with Bartlett’s leadership style, and much of the world was just happy enough to have sane leadership in Mexico City that they were willing to overlook such trivial matters for the time being. Mexico’s U.N. membership was restored in January of 1995, and during a state visit on January 16, President Bush announced to the world that all U.S. sanctions on Mexico would be lifted with immediate effect. The rest of the world followed suit, and by mid-April, the embargo had effectively been brought to an end. After enduring five different Presidents in as many years, followed by months of pariah status, the world was finally welcoming Mexico back with open arms.

But all was not well. While the embargo had been lifted, Muñoz Ledo had little hope of instituting any substantial fiscal reforms until the foreign debt was paid off—which, after five years of insolvency and financial mismanagement, had ballooned up to $35 billion. Aspe, Aguilar and Zedillo were hard at work trying to bring that number down, but Muñoz Ledo knew he wouldn’t be able to pay off much of anything without tapping into Mexico’s vast oil reserves, and for that, there was one huge obstacle in his way: the oil workers’ union. Way back in 1988, Miguel de la Madrid had tried to use oil money to pay off Mexico’s foreign debt. In response, the Petroleum Workers’ Syndicate, led by labor boss Joaquín “La Quina” Hernández Galicia, had gone on strike and annihilated the national economy. After that, de la Madrid, the Salinas brothers, and Manuel Bartlett had spent the following few years tripping over themselves granting favors and concessions to keep the oil workers happy. If the union had been corrupt before the strike, by 1995, it was a septic tank of graft and bribery with practically no state oversight and no safeguards against fraud and outright thievery. With La Quina’s parasitic web of patronage sucking up most of Pemex’s profits, scraping together enough oil money to pay off the debt would be about as easy as emptying the Gulf of Mexico with a cheesecloth. And if Muñoz Ledo attempted to reassert any form of government oversight over the use of the oil funds, La Quina might lead his workers back on strike and destroy any chance of a stable economic recovery. As negotiations with La Quina bore little fruit and IMF officials bristled at the thought of forgiving any more of Mexico’s debt without something solid as collateral, President Muñoz Ledo started to worry he might never find a way to pay off the debt without straight-up selling Chihuahua to Texas.

By his own account, on March 3, he was sitting in his office, idly considering trying to get Governor Richards on the phone, when a tragedy struck which, though it killed hundreds of Mexicans, would be the key to improving the lives of millions more.

__________

[1] This sale happened in 1997 in OTL, but Mexico's increased militarization, coupled with the intensified drug war and a larger role for the Air Force in the Zapatista uprising, has prompted the Secretariat of National Defense to buy the base a few years earlier.

Last edited:

Sounds like an explosion at a oil refinery, terminal or pipeline that had an illegal tap. Since Pemex is corrupt there probably has not been any upkeep or security done for a long time.Ho boy, what’s gonna happen now?

RamscoopRaider

Donor

This is a technical critique, but I think you have an issue with the aerial interception sequence. Most Air Traffic Control relies on Secondary Radar, which simply reads the transponder of an aircraft, something that would not be turned on for illicit flights. Primary Radar, which is what most people actually think of as Radar actually sees the Radar signature of the aircraft, but coverage for that is sketchy at lower altitudes even in the US and EU today. Mexico City International Airport only really got good Primary Radar Coverage of the Valley of Mexico in 2014, I don't think Puebla has a Primary Radar worth talking about even now for more than close in control, as in within 5 miles/8km (Mexico's Civil Aviation Authority uses miles). I think it would probably be most realistic for a military radar to find it, or for the aircraft to have been found by other means (knew the flight plan ahead of time, slipped a tracker onboard, guy with binoculars), as experienced traffickers should know where civil primary radar coverage is and avoid it

Tehuacan could probably track the last few moments of the aircraft as they should have a short range primary radar for within 5 miles

Tehuacan could probably track the last few moments of the aircraft as they should have a short range primary radar for within 5 miles

If I was to risk a guess, after looking at OTL industrial related disasters in Mexico, I'd say something based on the 1992 Guadalaraja explosions. Apparently, some Pemex officials were prosecuted in that affair, so I can imagine it twisted some way that allows Muñoz Ledo to take on the oil workers union.

Was genuinely not expecting PML to just... get away with it. Not that it seems unrealistic, but I think Bartlett conditioned all of us to believe in Murphy's Law as the only Mexican law worth the paper it's written on.

In fact, the deputies soon realized, without a PRI majority, it was technically impossible to bring either chamber into session.

Perhaps another argument for conspiracy theorists in this TL.This is a technical critique, but I think you have an issue with the aerial interception sequence. Most Air Traffic Control relies on Secondary Radar, which simply reads the transponder of an aircraft, something that would not be turned on for illicit flights. Primary Radar, which is what most people actually think of as Radar actually sees the Radar signature of the aircraft, but coverage for that is sketchy at lower altitudes even in the US and EU today. Mexico City International Airport only really got good Primary Radar Coverage of the Valley of Mexico in 2014, I don't think Puebla has a Primary Radar worth talking about even now for more than close in control, as in within 5 miles/8km (Mexico's Civil Aviation Authority uses miles). I think it would probably be most realistic for a military radar to find it, or for the aircraft to have been found by other means (knew the flight plan ahead of time, slipped a tracker onboard, guy with binoculars), as experienced traffickers should know where civil primary radar coverage is and avoid it

Tehuacan could probably track the last few moments of the aircraft as they should have a short range primary radar for within 5 miles

Uundoubtedly, conspiracy theorists don't usually leave something on the table.Perhaps another argument for conspiracy theorists in this TL.

Man, that was a great update. Good that Mexico escaped total collapse, but now I'm worried for the future...

This isn’t an update, but I just would like to express my amazement that between January 3-7, 2019, I wrote two chapters of this TL in which an unsuccessful presidential candidate gives a public speech two months after the election to his supporters (who believe the election was stolen from him by the establishment) in which he goes off his rocker, tells his supporters to storm the seat of the legislature, and they do it. Two years later to the day, it has actually happened, but in my country of all places.

Yes, we know Roberto, America is a beautiful majestic beast.This isn’t an update, but I just would like to express my amazement that between January 3-7, 2019, I wrote two chapters of this TL in which an unsuccessful presidential candidate gives a public speech two months after the election to his supporters (who believe the election was stolen from him by the establishment) in which he goes off his rocker, tells his supporters to storm the seat of the legislature, and they do it. Two years later to the day, it has actually happened, but in my country of all places.

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special Announcement

Share: