I think I like the OTL better myself...Hurray for Vicente Fox! Then again, I wonder if ultimately this would be good for Mexico into the new century? If the new government is able to purge the high level corruption and there is enough grassroots support to use this as a sort of rebirth like the "first" revolution, Mexico in the 21st century would actually have a much brighter future. Maybe even manage the cartels a little better, maintain economic growth and not lose so much of the GDP to corruption. But I get the feeling that El Rey has more nefarious plans.What a good story you murdered Mexico

but he saved Venezuela and on his way to the Latin American left

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Al Grito de Guerra: the Second Mexican Revolution

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special Announcement

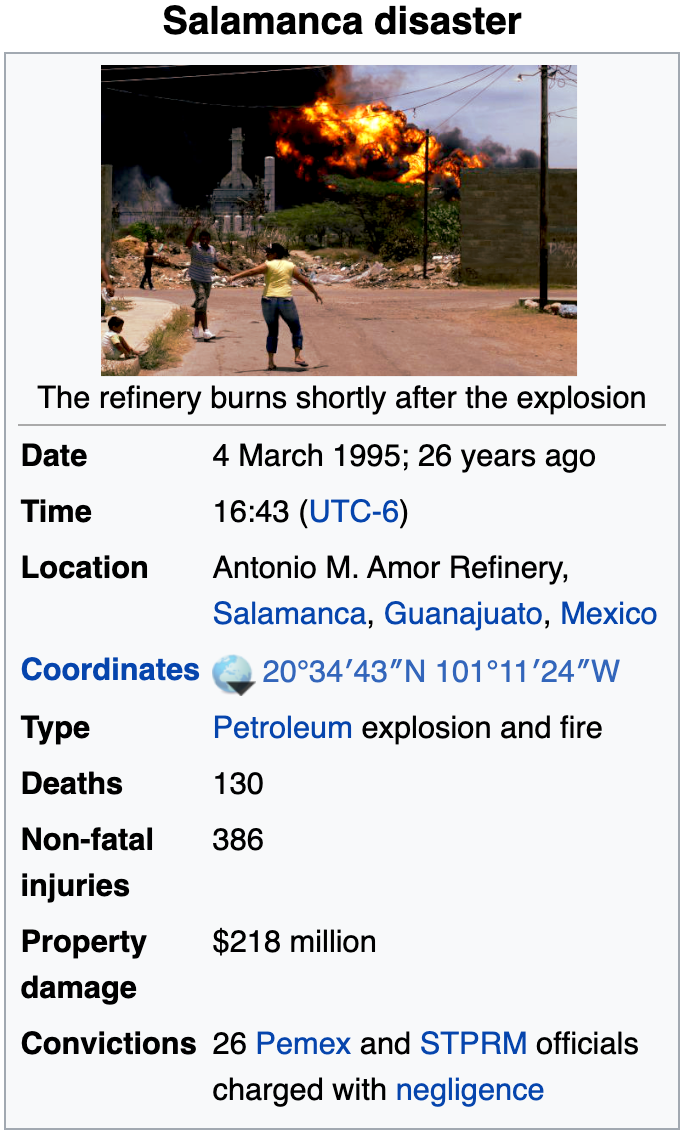

Part 24: Salamanca disaster

The fireball which engulfed the town of Salamanca, Guanajuato, on March 4, 1995, killing 130 people and wounding hundreds more, was utterly and entirely preventable.

SPTRM, the union which represented Mexico’s 300,000 public-sector oil workers, had always had a lax attitude towards safety standards. But the incendiary brew of greed, negligence, and outright cowardice which caused the tragedy in Salamanca was shocking even by Pemex standards. On the morning of March 4, a pipeline ruptured at the Antonio M. Amor Refinery in Salamanca, causing 530 cubic meters of propane gas to spill out into one of the refinery’s maintenance rooms. The faulty gas detectors failed to register the leak, and when it was finally detected, the shift supervisor decided to crack open the maintenance room door to allow the gas to dissipate, rather than risk bad publicity by telling the authorities and forcing an evacuation of the surrounding neighborhoods (this solution was technologically unsound, but the supervisor couldn’t have known that—after all, he’d gotten the job not on merit but by bribing the local STPRM boss).

Of course, the casualty toll would not have been anywhere near as high had it not been for the greed of the refinery director, Manuel Limón Hernández. To supplement his income, Limón ran what amounted to a black market for black gold. Every other Sunday since 1992, residents of Salamanca and the surrounding communities would grab their jerry cans and line up in front of a large storage tank in the refinery's parking lot, where a surly-faced Pemex technician would dispense gasoline at racket prices under Director Limón’s watchful eye. [1] The venture drew lucrative profits to supplement Limón’s already-considerable salary, with plenty left over to keep underlings and local law enforcement quiet. By the time Limón found out about the gas leak on the afternoon of March 4th, locals were already queuing up for their share of cut-rate gasoline, and he wasn’t about to send them home and lose out on two weeks’ worth of profits. So, rather than ordering an evacuation, Limón simply called in sick, retreated to his home on Salamanca’s affluent north end, called his assistant director and instructed him to carry on like any normal Sunday.

And then, cruel, horrible, predictable tragedy struck. At 4:53 PM, while eighty-six Salmanticenses waited their turn at the pump, the plume of propane gas from the maintenance room wafted its way up to the flare pit and ignited. The refinery was shrouded in flame. The storage tank turned into an enormous fireball, sending 93 men, women and children to an instant, scorching death. The explosion also set off another, neighboring storage tank, which killed thirteen more people and set fire to several nearby houses. By the time the blaze was put out eleven hours later, it had already raged through most of the adjacent neighborhoods, killing twenty-four residents and leaving a thousand more homeless. In the end, Salamanca lost 130 of its people and one of its main sources of employment to negligence and greed.

News of the disaster hit the Sunday papers the following morning. The public reacted with seething fury at Pemex, the STPRM, and their entire leadership cadre. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo had already been searching for a way to break the STPRM's stranglehold on Mexico's oil revenues, and he was determined not to let this opportunity slip by. On the morning of March 6, the President gave his first televised address since his official inauguration. In it, he drew somber comparisons to the San Juanico disaster of 1984, an explosion which had caused even more deaths and injuries but had resulted in no consequences for anyone, including its powerful leader, Joaquín “La Quina” Hernández Galicia. Muñoz Ledo went on to announce that his administration would be launching an aggressive investigation into the STPRM and its leadership, promising that history would not repeat itself and that justice would be “swift, clean and decisive”. He wasn’t exaggerating: just as he was finishing up his speech, a team of soldiers in full combat dress was busy rolling up to La Quina’s home on the outskirts of Ciudad Madero, blowing out his front door with a bazooka and dragging the king of Mexican oil outside in his bathrobe. [2]

Enraged, the STPRM immediately declared a wildcat strike. But popular opinion was so dead-set against the oil workers that when they stormed out into the streets, they were pelted with garbage and rotten eggs. The union had already been one of the most hated institutions in Mexico for its corruption and its role in causing the recession of 1988, and the explosions in Salamanca had elevated this resentment to a white-hot, burning hatred. Within two days of La Quina’s arrest, the union backed down in the face of overwhelming public opposition. The same day, Procurator General Santiago Creel began preparing a wide array of charges against La Quina, Manuel Limón, and two dozen other Pemex and SPTRM officials, ranging from endless counts of embezzlement to grand larceny and racketeering.

While the oil men awaited their day in court, the Congress of the Union was working to advance key democratic priorities. The first opposition-controlled Congress in Mexican history had been disappointingly sluggish in its first few months, as a majority caucus composed entirely of outsiders struggled to come to terms with the levers of power. By early 1995, though, congressional leadership had finally gotten a handle on legislative proceedings, and Muñoz Ledo was soon working in tandem with Senate President Pablo Gómez and Chamber of Deputies President Sergio Aguayo to strengthen civil liberties and government accountability. First on the list of priorities was the Freedom of Information Law, a pet project of Aguayo’s from his days as a grassroots activist, which opened up federal records to citizens and journalists. This was followed by a series of measures to officially liberalize and deregulate the print media sector, which had spent the Bartlett years suffocating under the weight of draconian security restrictions.

The Legislative Palace of San Lázaro had burned to the ground in 1988, and the cash-strapped Bartlett administration could never seem to find the money to rebuild it. One of the opposition-controlled legislature's first acts in 1994 was to appropriate funds to rebuild the Palace as a symbol of the rebirth of Mexican democracy. By mid-1995, progress was well underway, and a grand opening was planned at the inauguration of the next Congress in 1997.

Next up on the list were the many civil liberties which had been trampled under Bartlett. In late March, the right to free expression, the right to protest and to organize political movements (already guaranteed by the Constitution but limited in practice by various lesser laws) were all re-codified in law. The many newspapers and magazines which emerged in 1995 celebrated these achievements; the zeitgeist of this new age was captured most clearly on April 2 in the inaugural issue of El Nuevo Siglo, a new, daily broadsheet based out of Guadalajara. The front page carried a joint editorial in which a pair of young, female journalists, Lydia Cacho and Xanic von Bertrab, revealed that they had been behind the investigation which had revealed Carrillogate and, indirectly, brought down the Bartlett regime. In the editorial, Cacho and von Bertrab (who soon would be awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for their efforts) praised Muñoz Ledo for liberalizing the media, while pledging to hold him and his administration to account if they ever strayed into old-style authoritarianism.

Although these measures were passed with near-unanimous support, one proposal was far more contentious. Opposition activists in Mexico had long been advocating for the formation of a Truth Commission to investigate human rights abuses by past PRI administrations, particularly during the “Dirty War” of the 1970s and the unhappy Bartlett years. Many in the Congress and the administration, led by Sergio Aguayo and Foreign Secretary Adolfo Aguilar Zínser, supported such a commission. However, others, led by Santiago Creel and other conservative panistas, argued that it was move on and leave the past behind. Muñoz Ledo was conspicuously silent on the issue, and the new political dailies were soon accusing him of a conflict of interest, seeing as he had served in several high offices throughout the 1970s, and therefore had likely been complicit in, or at least aware of, some of the abuses of the Dirty War. When Aguayo and Gómez managed to muscle a watered-down version of the Truth Commission through the Congress, Muñoz Ledo signed it, but human rights activists such as Rosario Ibarra de Piedra interpreted his lack of enthusiasm as a black mark in and of itself.

This controversy, however, was largely overshadowed by the Pemex trials. By the end of April, La Quina and twenty-five of his cronies had each pled guilty to multiple felony charges and been handed lengthy prison sentences. Shortly after the sentencing, El Universal published the results of a brilliant investigation which had discovered appallingly dangerous conditions at Pemex facilities all over the country (perhaps the most alarming revelation of all was that one facility in Guadalajara was a single mishap away from leaking rivers of gasoline into the sewers and causing an explosion that would have made the Salamanca disaster look like a damp firecracker [3]). In light of these revelations, President Muñoz Ledo announced in late May a complete and total shakeup of the Pemex and its leadership. The company's incumbent Director-General was sacked and an outsider, PAN-affiliated lawyer Antonio Lozano García, brought in. To wrest back financial control of the company, Lozano brought in 4,000 outside management appointees (referred to by grumbling Pemex loyalists as “smurfs” [4]) who swiftly began hacking away at the thick rot of corruption and patronage. Under pressure from Labor Secretary Arturo Alcalde, the STPRM chose an ally of the administration—Ramiro Berrón, a petroleum engineer, union dissident and newly-elected PAN deputy from Villahermosa—as its new leader. And when Director-General Lozano announced in July that all of the union’s most lucrative perks and privileges would be revoked, the once-mighty union was as docile as a lamb. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, perhaps the most pro-labor president since Lázaro Cárdenas, had broken the back of Mexico’s most powerful and most corrupt union.

While STPRM leader Joaquín “La Quina” Galicia Hernández (center) was not deemed personally responsible for the explosion in Salamanca, the prosecution successfully argued that he had created the “atmosphere of corruption and impunity” which led to the disaster, a charge which would earn La Quina twenty-eight years in federal prison.

Yet as the threat from the STPRM subsided, Muñoz Ledo soon found that the kum-ba-ya, let’s-all-get-along attitude which had characterized the first year of his presidency did not extend to all issues. Now that a handful of corrupt grease monkeys no longer controlled 33% of his government’s revenue, Muñoz Ledo set out with renewed vigor to pay off the foreign debt, and in August of 1995, he unveiled a plan to settle Mexico’s $35 billion obligations over an eleven-year period. However, the plan was not as popular as Muñoz Ledo had hoped. It required him to delay many of the welfare reinvestments he’d promised on the campaign trail, drawing the ire many voters and political allies and prompting several of the more nationalistically-inclined politicians to accuse Muñoz Ledo of selling out Mexico’s sovereignty to the Pentagon. The plan eventually passed, after a majority of legislators faced up to the hard truth that there was little hope for a robust economic recovery as long as Mexico owed 40% of its GDP to foreign creditors. But the unity of the anti-PRI coalition had been challenged, in preparation for an issue that would truly test its resilience: labor reform.

Despite the immense power held by organized labor under the PRI regime, Mexican labor laws in the 1990s were among the most authoritarian of any country in North America. Almost everyone, from garbage collectors to mariachi band members, was represented by a union of some kind. But the identities of union officials, as well as the details of the contracts they signed, were kept secret by law, thus preventing workers from holding their “representatives” accountable. The sole authority to recognize unions and authorize strikes lay with a nationwide system of labor boards, which heavily favored PRI-affiliated syndicates and routinely suppressed the activities of independent unions. Perhaps worst of all, businesses were required to fire any employee who lost his or her union membership, allowing bureaucrats in the Labor Secretariat to deprive uppity dissidents of their livelihoods with the stroke of a pen. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo was well-acquainted with theses issues from his time as Labor Secretary in the 1970s, and now that he was President, he was determined to fix them. On September 1, 1995, after months of negotiations between Labor Secretary Arturo Alcalde and various prominent labor leaders (including Julia Quiñónez, the young, fiery leader of the Border Worker’s Committee and freshman PAN deputy from Coahuila), a Labor Rights Law was formally introduced in the Congress.

It was the first real fight of Muñoz Ledo’s presidency. As introduced, the Law was extremely ambitious: among many other things, it amended the Constitution to abolish the labor board system, codified the right to strike, raised the minimum wage, imposed hundreds of pages’ worth of detailed safety standards, and empowered the Labor Secretariat to impose hefty fines on employers that violated these rights. Unsurprisingly, it met with strident opposition from entrepreneurs; the big businesses, which had previously supported Muñoz Ledo and his policies, suddenly mobilized against him, busing in white-collar office workers from the Mexico City suburbs to protest against it. Naturally, the unions staged counter-demonstrations. But they struggled to respond in early October when TV Azteca joined the fray by introducing a new addition to its daily programming: roundtable discussions on the political and civic issues of the day, hosted by a panel of credentialed experts who all, by sheer coincidence, happened to be virulently opposed to the Labor Rights Law.

Outside the northern border states, most of Mexico’s independent unions were only one or two years old by 1995. The fight over the Labor Rights Law gave them their first taste of partisan, political organizing, which would prove useful as the 1997 electoral season approached.

The Labor Rights Law also exposed fault lines in Mexico’s developing party system. Although the PAN held a commanding majority in both houses of Congress, it was split between a conservative, pro-business wing anchored in the entrepreneurial middle class, and a social-democratic, pro-labor wing rooted in the unions. Panista legislators were soon locked in increasingly heated debates with each other on the Congress floor, and finding the requisite two-thirds majority for a Constitutional amendment forced Muñoz Ledo to expend much of his political capital with the PAN’s right wing. In the end, though, pressure from the administration, from the unions, and from an aggressive public relations campaign which characterized the new Law as the only way to take back power from La Quina and his ilk, paid off. The Labor Rights Law was narrowly approved by both chambers of the Congress on November 12, 1995, just as President Muñoz Ledo was hosting a state dinner at Los Pinos in honor of Lydia Cacho and Xanic von Bertrab. For the second time in a century, labor rights in Mexico had been revolutionized.

While the Labor Rights Law was percolating its way through the legislature, Muñoz Ledo’s administration had been taking its first baby steps toward peace with the Zapatistas. Since mid-1994, the renegade State of Zapata had been on the rebound from its Bartlett-era nadir. In July, pre-election unrest in the major cities had given Bartlett no choice but to transfer troops out of Chiapas for peacekeeping, and after Muñoz Ledo was sworn in as President in August, he made a point of prioritizing the fight against the cartels over the fight against the Zapatistas. This greatly eased the pressure on the fledgling rebel state, and by early 1995, communities which had spent over a year under siege by the Army had finally been liberated by the ELM. The state’s nominal governor, Bishop Samuel Ruiz, had succeeded in bringing together several of Zapata’s infamously-antagonistic factions, and his army of missionaries and catechists had established a network of communication and exchange which had united once-hostile villages. So when the federal government reached out to Governor Ruiz with an olive branch, he agreed from a position of strength. On September 4, 1995, at the invitation of President Muñoz Ledo, 130,000 Zapatistas and indigenous rights activists arrived in Mexico City for a mass rally at the Zócalo. And when Subcomandante Marcos, the ELM’s masked, spiritual leader, took to the stage to address the assembled throngs (just as Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas had done seven years prior to call his followers to revolution), he gave a passionate speech demanding that the Congress pass an “Indigenous Bill of Rights” to embed the longstanding, communal traditions of the Mayan and other indigenous peoples into the Mexican Constitution.

Subcomandante Marcos and thousands of other Zapatistas marched all the way from Chiapas to Mexico City for the rally in September, a three-week journey which was later dubbed “La Marcha del Color de la Tierra” after a phrase in Marcos's speech.

Legislation was soon introduced to codify these rights. But it quickly became clear that many of the Zapatistas’ most stringent demands, such as the right to communal ownership over land and the right to form autonomous regions and states within Mexico, had no chance of passing the Congress. Many deputies and senators considered the State of Zapata to be an illegitimate, treasonous entity, and were loath to formally recognize it as a negotiating partner. Conservatives, led by PAN deputy and power broker Diego Fernández de Cevallos, were dead-set against communal land ownership. And unlike with the Labor Rights Law, there was little chance of getting the left wing of the PAN to pull out all the stops in favor of the legislation, because there was very little overlap between the Zapatistas’ interests and those of the labor movement. In November of 1995, the Chamber of Deputies passed a version of the Indigenous Bill of Rights with many key provisions amended into oblivion, which Subcomandante Marcos promptly tarred as an “insult” and a “betrayal” of the Zapatista movement. Senate President Pablo Gómez, at Muñoz Ledo’s urging, declined to table the bill in his chamber. Muñoz Ledo’s policy of benign neglect would keep outright hostilities between the Zapatistas and the federal government down to a minimum, but a stable, lasting peace would have to come another day.

Indeed, as the months ticked past and ambitious projects for reform—such as extending the social safety net, privatizing the ejido system of state-owned farmland, and decentralizing power from the capital to the states and municipalities—fizzled away in the Congress, a narrative started to form in the press. The sentiment, echoed by talking heads on Televisa and in the blossoming print media, was that the mass coalition of voters which had swept Muñoz Ledo into power had been formed to destroy the old system, not to build a new one in its place. The vast, pan-Mexican alliance of young and old, rich and poor, workers and farmers, CEOs and street cleaners which had joined forces at the ballot box in 1994 had agreed on plenty of important things, including the need to dismantle the PRI regime, construct a pluralist electoral system, and entrench in law the fundamental rights, freedoms and transparencies which had been denied to them under the PRI. But beyond those aims, visions of what a free and democratic Mexico should look like diverged wildly, both within and between parties, classes, sectors, and movements. These divergences were the reason why the 61st Congress was an incoherent mess of groups and factions which struggled to find consensus on most issues. And, to many politicians and intellectuals, the stage on which this impasse was to be settled would be the congressional elections of 1997. Whichever party or faction came out on top in those elections, the political commentators predicted, would have a mandate to rebuild Mexico from the ground up and define how the country would look as it entered the new millennium. As writer and PAN deputy Julio Scherer put it in his weekly column in La Jornada, “The Mexico of yesterday died in 1994. The Mexico of tomorrow will be born in 1997”.

Not everyone was quite so dramatic about the Congressional elections of 1997, but it was widely agreed that, as the first-ever federal elections held under an administration ostensibly interested in making them free and fair, they would be a key moment in Mexico’s democratic transition. And so in early 1996, more than a year and a half out, various parties and factions were already preparing for what was shaping up to be the first true electoral campaign of their lifetimes. For the moment, however, many “regular” Mexicans were finding themselves more captivated by their neighbor to the north, whose own approaching election was shaping up to be historic in a way of its own.

[2] In OTL, La Quina was arrested in pretty much the exact same way on January 10, 1989.

[3] In OTL, such an explosion did happen. On April 22, 1992, a large amount of gasoline leaked into the Guadalajara sewers and ignited, destroying five miles’ worth of streets, killing over 200 people and gravely wounding a thousand more (Xanic von Bertrab, who was working for a local rag at the time, found out about the leak the day before the explosion, but the authorities didn’t listen to her in time to stop the tragedy). In TTL, the explosion itself has been butterflied away, but the abhorrent safety standards which let it happen have metastasized to Pemex installations in other parts of the country due to the lack of federal oversight.

[4] Actual name used by Pemex employees to refer to outside managers, so called because they are of unknown origin and have a habit of multiplying very quickly.

SPTRM, the union which represented Mexico’s 300,000 public-sector oil workers, had always had a lax attitude towards safety standards. But the incendiary brew of greed, negligence, and outright cowardice which caused the tragedy in Salamanca was shocking even by Pemex standards. On the morning of March 4, a pipeline ruptured at the Antonio M. Amor Refinery in Salamanca, causing 530 cubic meters of propane gas to spill out into one of the refinery’s maintenance rooms. The faulty gas detectors failed to register the leak, and when it was finally detected, the shift supervisor decided to crack open the maintenance room door to allow the gas to dissipate, rather than risk bad publicity by telling the authorities and forcing an evacuation of the surrounding neighborhoods (this solution was technologically unsound, but the supervisor couldn’t have known that—after all, he’d gotten the job not on merit but by bribing the local STPRM boss).

Of course, the casualty toll would not have been anywhere near as high had it not been for the greed of the refinery director, Manuel Limón Hernández. To supplement his income, Limón ran what amounted to a black market for black gold. Every other Sunday since 1992, residents of Salamanca and the surrounding communities would grab their jerry cans and line up in front of a large storage tank in the refinery's parking lot, where a surly-faced Pemex technician would dispense gasoline at racket prices under Director Limón’s watchful eye. [1] The venture drew lucrative profits to supplement Limón’s already-considerable salary, with plenty left over to keep underlings and local law enforcement quiet. By the time Limón found out about the gas leak on the afternoon of March 4th, locals were already queuing up for their share of cut-rate gasoline, and he wasn’t about to send them home and lose out on two weeks’ worth of profits. So, rather than ordering an evacuation, Limón simply called in sick, retreated to his home on Salamanca’s affluent north end, called his assistant director and instructed him to carry on like any normal Sunday.

And then, cruel, horrible, predictable tragedy struck. At 4:53 PM, while eighty-six Salmanticenses waited their turn at the pump, the plume of propane gas from the maintenance room wafted its way up to the flare pit and ignited. The refinery was shrouded in flame. The storage tank turned into an enormous fireball, sending 93 men, women and children to an instant, scorching death. The explosion also set off another, neighboring storage tank, which killed thirteen more people and set fire to several nearby houses. By the time the blaze was put out eleven hours later, it had already raged through most of the adjacent neighborhoods, killing twenty-four residents and leaving a thousand more homeless. In the end, Salamanca lost 130 of its people and one of its main sources of employment to negligence and greed.

News of the disaster hit the Sunday papers the following morning. The public reacted with seething fury at Pemex, the STPRM, and their entire leadership cadre. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo had already been searching for a way to break the STPRM's stranglehold on Mexico's oil revenues, and he was determined not to let this opportunity slip by. On the morning of March 6, the President gave his first televised address since his official inauguration. In it, he drew somber comparisons to the San Juanico disaster of 1984, an explosion which had caused even more deaths and injuries but had resulted in no consequences for anyone, including its powerful leader, Joaquín “La Quina” Hernández Galicia. Muñoz Ledo went on to announce that his administration would be launching an aggressive investigation into the STPRM and its leadership, promising that history would not repeat itself and that justice would be “swift, clean and decisive”. He wasn’t exaggerating: just as he was finishing up his speech, a team of soldiers in full combat dress was busy rolling up to La Quina’s home on the outskirts of Ciudad Madero, blowing out his front door with a bazooka and dragging the king of Mexican oil outside in his bathrobe. [2]

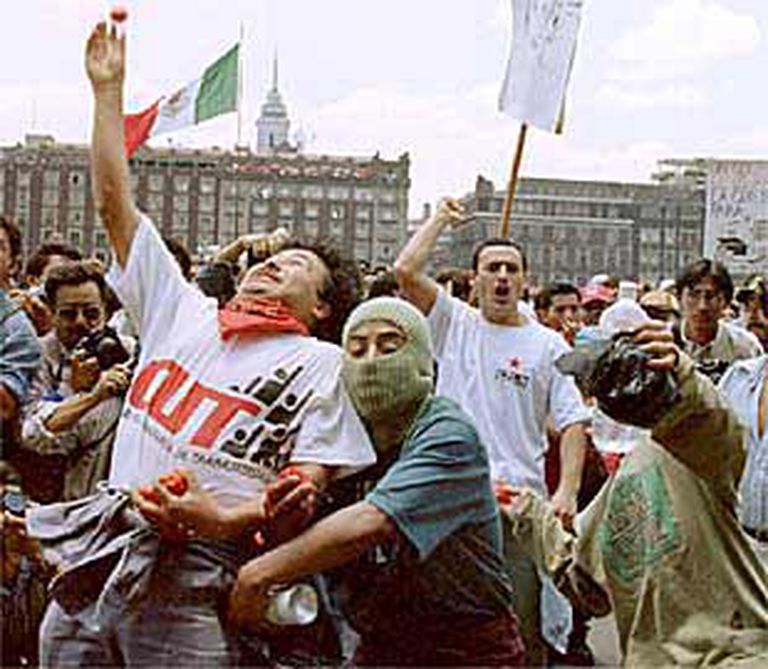

Enraged, the STPRM immediately declared a wildcat strike. But popular opinion was so dead-set against the oil workers that when they stormed out into the streets, they were pelted with garbage and rotten eggs. The union had already been one of the most hated institutions in Mexico for its corruption and its role in causing the recession of 1988, and the explosions in Salamanca had elevated this resentment to a white-hot, burning hatred. Within two days of La Quina’s arrest, the union backed down in the face of overwhelming public opposition. The same day, Procurator General Santiago Creel began preparing a wide array of charges against La Quina, Manuel Limón, and two dozen other Pemex and SPTRM officials, ranging from endless counts of embezzlement to grand larceny and racketeering.

While the oil men awaited their day in court, the Congress of the Union was working to advance key democratic priorities. The first opposition-controlled Congress in Mexican history had been disappointingly sluggish in its first few months, as a majority caucus composed entirely of outsiders struggled to come to terms with the levers of power. By early 1995, though, congressional leadership had finally gotten a handle on legislative proceedings, and Muñoz Ledo was soon working in tandem with Senate President Pablo Gómez and Chamber of Deputies President Sergio Aguayo to strengthen civil liberties and government accountability. First on the list of priorities was the Freedom of Information Law, a pet project of Aguayo’s from his days as a grassroots activist, which opened up federal records to citizens and journalists. This was followed by a series of measures to officially liberalize and deregulate the print media sector, which had spent the Bartlett years suffocating under the weight of draconian security restrictions.

The Legislative Palace of San Lázaro had burned to the ground in 1988, and the cash-strapped Bartlett administration could never seem to find the money to rebuild it. One of the opposition-controlled legislature's first acts in 1994 was to appropriate funds to rebuild the Palace as a symbol of the rebirth of Mexican democracy. By mid-1995, progress was well underway, and a grand opening was planned at the inauguration of the next Congress in 1997.

Next up on the list were the many civil liberties which had been trampled under Bartlett. In late March, the right to free expression, the right to protest and to organize political movements (already guaranteed by the Constitution but limited in practice by various lesser laws) were all re-codified in law. The many newspapers and magazines which emerged in 1995 celebrated these achievements; the zeitgeist of this new age was captured most clearly on April 2 in the inaugural issue of El Nuevo Siglo, a new, daily broadsheet based out of Guadalajara. The front page carried a joint editorial in which a pair of young, female journalists, Lydia Cacho and Xanic von Bertrab, revealed that they had been behind the investigation which had revealed Carrillogate and, indirectly, brought down the Bartlett regime. In the editorial, Cacho and von Bertrab (who soon would be awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for their efforts) praised Muñoz Ledo for liberalizing the media, while pledging to hold him and his administration to account if they ever strayed into old-style authoritarianism.

Although these measures were passed with near-unanimous support, one proposal was far more contentious. Opposition activists in Mexico had long been advocating for the formation of a Truth Commission to investigate human rights abuses by past PRI administrations, particularly during the “Dirty War” of the 1970s and the unhappy Bartlett years. Many in the Congress and the administration, led by Sergio Aguayo and Foreign Secretary Adolfo Aguilar Zínser, supported such a commission. However, others, led by Santiago Creel and other conservative panistas, argued that it was move on and leave the past behind. Muñoz Ledo was conspicuously silent on the issue, and the new political dailies were soon accusing him of a conflict of interest, seeing as he had served in several high offices throughout the 1970s, and therefore had likely been complicit in, or at least aware of, some of the abuses of the Dirty War. When Aguayo and Gómez managed to muscle a watered-down version of the Truth Commission through the Congress, Muñoz Ledo signed it, but human rights activists such as Rosario Ibarra de Piedra interpreted his lack of enthusiasm as a black mark in and of itself.

This controversy, however, was largely overshadowed by the Pemex trials. By the end of April, La Quina and twenty-five of his cronies had each pled guilty to multiple felony charges and been handed lengthy prison sentences. Shortly after the sentencing, El Universal published the results of a brilliant investigation which had discovered appallingly dangerous conditions at Pemex facilities all over the country (perhaps the most alarming revelation of all was that one facility in Guadalajara was a single mishap away from leaking rivers of gasoline into the sewers and causing an explosion that would have made the Salamanca disaster look like a damp firecracker [3]). In light of these revelations, President Muñoz Ledo announced in late May a complete and total shakeup of the Pemex and its leadership. The company's incumbent Director-General was sacked and an outsider, PAN-affiliated lawyer Antonio Lozano García, brought in. To wrest back financial control of the company, Lozano brought in 4,000 outside management appointees (referred to by grumbling Pemex loyalists as “smurfs” [4]) who swiftly began hacking away at the thick rot of corruption and patronage. Under pressure from Labor Secretary Arturo Alcalde, the STPRM chose an ally of the administration—Ramiro Berrón, a petroleum engineer, union dissident and newly-elected PAN deputy from Villahermosa—as its new leader. And when Director-General Lozano announced in July that all of the union’s most lucrative perks and privileges would be revoked, the once-mighty union was as docile as a lamb. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, perhaps the most pro-labor president since Lázaro Cárdenas, had broken the back of Mexico’s most powerful and most corrupt union.

While STPRM leader Joaquín “La Quina” Galicia Hernández (center) was not deemed personally responsible for the explosion in Salamanca, the prosecution successfully argued that he had created the “atmosphere of corruption and impunity” which led to the disaster, a charge which would earn La Quina twenty-eight years in federal prison.

Yet as the threat from the STPRM subsided, Muñoz Ledo soon found that the kum-ba-ya, let’s-all-get-along attitude which had characterized the first year of his presidency did not extend to all issues. Now that a handful of corrupt grease monkeys no longer controlled 33% of his government’s revenue, Muñoz Ledo set out with renewed vigor to pay off the foreign debt, and in August of 1995, he unveiled a plan to settle Mexico’s $35 billion obligations over an eleven-year period. However, the plan was not as popular as Muñoz Ledo had hoped. It required him to delay many of the welfare reinvestments he’d promised on the campaign trail, drawing the ire many voters and political allies and prompting several of the more nationalistically-inclined politicians to accuse Muñoz Ledo of selling out Mexico’s sovereignty to the Pentagon. The plan eventually passed, after a majority of legislators faced up to the hard truth that there was little hope for a robust economic recovery as long as Mexico owed 40% of its GDP to foreign creditors. But the unity of the anti-PRI coalition had been challenged, in preparation for an issue that would truly test its resilience: labor reform.

Despite the immense power held by organized labor under the PRI regime, Mexican labor laws in the 1990s were among the most authoritarian of any country in North America. Almost everyone, from garbage collectors to mariachi band members, was represented by a union of some kind. But the identities of union officials, as well as the details of the contracts they signed, were kept secret by law, thus preventing workers from holding their “representatives” accountable. The sole authority to recognize unions and authorize strikes lay with a nationwide system of labor boards, which heavily favored PRI-affiliated syndicates and routinely suppressed the activities of independent unions. Perhaps worst of all, businesses were required to fire any employee who lost his or her union membership, allowing bureaucrats in the Labor Secretariat to deprive uppity dissidents of their livelihoods with the stroke of a pen. Porfirio Muñoz Ledo was well-acquainted with theses issues from his time as Labor Secretary in the 1970s, and now that he was President, he was determined to fix them. On September 1, 1995, after months of negotiations between Labor Secretary Arturo Alcalde and various prominent labor leaders (including Julia Quiñónez, the young, fiery leader of the Border Worker’s Committee and freshman PAN deputy from Coahuila), a Labor Rights Law was formally introduced in the Congress.

It was the first real fight of Muñoz Ledo’s presidency. As introduced, the Law was extremely ambitious: among many other things, it amended the Constitution to abolish the labor board system, codified the right to strike, raised the minimum wage, imposed hundreds of pages’ worth of detailed safety standards, and empowered the Labor Secretariat to impose hefty fines on employers that violated these rights. Unsurprisingly, it met with strident opposition from entrepreneurs; the big businesses, which had previously supported Muñoz Ledo and his policies, suddenly mobilized against him, busing in white-collar office workers from the Mexico City suburbs to protest against it. Naturally, the unions staged counter-demonstrations. But they struggled to respond in early October when TV Azteca joined the fray by introducing a new addition to its daily programming: roundtable discussions on the political and civic issues of the day, hosted by a panel of credentialed experts who all, by sheer coincidence, happened to be virulently opposed to the Labor Rights Law.

Outside the northern border states, most of Mexico’s independent unions were only one or two years old by 1995. The fight over the Labor Rights Law gave them their first taste of partisan, political organizing, which would prove useful as the 1997 electoral season approached.

The Labor Rights Law also exposed fault lines in Mexico’s developing party system. Although the PAN held a commanding majority in both houses of Congress, it was split between a conservative, pro-business wing anchored in the entrepreneurial middle class, and a social-democratic, pro-labor wing rooted in the unions. Panista legislators were soon locked in increasingly heated debates with each other on the Congress floor, and finding the requisite two-thirds majority for a Constitutional amendment forced Muñoz Ledo to expend much of his political capital with the PAN’s right wing. In the end, though, pressure from the administration, from the unions, and from an aggressive public relations campaign which characterized the new Law as the only way to take back power from La Quina and his ilk, paid off. The Labor Rights Law was narrowly approved by both chambers of the Congress on November 12, 1995, just as President Muñoz Ledo was hosting a state dinner at Los Pinos in honor of Lydia Cacho and Xanic von Bertrab. For the second time in a century, labor rights in Mexico had been revolutionized.

While the Labor Rights Law was percolating its way through the legislature, Muñoz Ledo’s administration had been taking its first baby steps toward peace with the Zapatistas. Since mid-1994, the renegade State of Zapata had been on the rebound from its Bartlett-era nadir. In July, pre-election unrest in the major cities had given Bartlett no choice but to transfer troops out of Chiapas for peacekeeping, and after Muñoz Ledo was sworn in as President in August, he made a point of prioritizing the fight against the cartels over the fight against the Zapatistas. This greatly eased the pressure on the fledgling rebel state, and by early 1995, communities which had spent over a year under siege by the Army had finally been liberated by the ELM. The state’s nominal governor, Bishop Samuel Ruiz, had succeeded in bringing together several of Zapata’s infamously-antagonistic factions, and his army of missionaries and catechists had established a network of communication and exchange which had united once-hostile villages. So when the federal government reached out to Governor Ruiz with an olive branch, he agreed from a position of strength. On September 4, 1995, at the invitation of President Muñoz Ledo, 130,000 Zapatistas and indigenous rights activists arrived in Mexico City for a mass rally at the Zócalo. And when Subcomandante Marcos, the ELM’s masked, spiritual leader, took to the stage to address the assembled throngs (just as Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas had done seven years prior to call his followers to revolution), he gave a passionate speech demanding that the Congress pass an “Indigenous Bill of Rights” to embed the longstanding, communal traditions of the Mayan and other indigenous peoples into the Mexican Constitution.

Subcomandante Marcos and thousands of other Zapatistas marched all the way from Chiapas to Mexico City for the rally in September, a three-week journey which was later dubbed “La Marcha del Color de la Tierra” after a phrase in Marcos's speech.

Legislation was soon introduced to codify these rights. But it quickly became clear that many of the Zapatistas’ most stringent demands, such as the right to communal ownership over land and the right to form autonomous regions and states within Mexico, had no chance of passing the Congress. Many deputies and senators considered the State of Zapata to be an illegitimate, treasonous entity, and were loath to formally recognize it as a negotiating partner. Conservatives, led by PAN deputy and power broker Diego Fernández de Cevallos, were dead-set against communal land ownership. And unlike with the Labor Rights Law, there was little chance of getting the left wing of the PAN to pull out all the stops in favor of the legislation, because there was very little overlap between the Zapatistas’ interests and those of the labor movement. In November of 1995, the Chamber of Deputies passed a version of the Indigenous Bill of Rights with many key provisions amended into oblivion, which Subcomandante Marcos promptly tarred as an “insult” and a “betrayal” of the Zapatista movement. Senate President Pablo Gómez, at Muñoz Ledo’s urging, declined to table the bill in his chamber. Muñoz Ledo’s policy of benign neglect would keep outright hostilities between the Zapatistas and the federal government down to a minimum, but a stable, lasting peace would have to come another day.

Indeed, as the months ticked past and ambitious projects for reform—such as extending the social safety net, privatizing the ejido system of state-owned farmland, and decentralizing power from the capital to the states and municipalities—fizzled away in the Congress, a narrative started to form in the press. The sentiment, echoed by talking heads on Televisa and in the blossoming print media, was that the mass coalition of voters which had swept Muñoz Ledo into power had been formed to destroy the old system, not to build a new one in its place. The vast, pan-Mexican alliance of young and old, rich and poor, workers and farmers, CEOs and street cleaners which had joined forces at the ballot box in 1994 had agreed on plenty of important things, including the need to dismantle the PRI regime, construct a pluralist electoral system, and entrench in law the fundamental rights, freedoms and transparencies which had been denied to them under the PRI. But beyond those aims, visions of what a free and democratic Mexico should look like diverged wildly, both within and between parties, classes, sectors, and movements. These divergences were the reason why the 61st Congress was an incoherent mess of groups and factions which struggled to find consensus on most issues. And, to many politicians and intellectuals, the stage on which this impasse was to be settled would be the congressional elections of 1997. Whichever party or faction came out on top in those elections, the political commentators predicted, would have a mandate to rebuild Mexico from the ground up and define how the country would look as it entered the new millennium. As writer and PAN deputy Julio Scherer put it in his weekly column in La Jornada, “The Mexico of yesterday died in 1994. The Mexico of tomorrow will be born in 1997”.

Not everyone was quite so dramatic about the Congressional elections of 1997, but it was widely agreed that, as the first-ever federal elections held under an administration ostensibly interested in making them free and fair, they would be a key moment in Mexico’s democratic transition. And so in early 1996, more than a year and a half out, various parties and factions were already preparing for what was shaping up to be the first true electoral campaign of their lifetimes. For the moment, however, many “regular” Mexicans were finding themselves more captivated by their neighbor to the north, whose own approaching election was shaping up to be historic in a way of its own.

__________

[1] As far as I know, in OTL, it is not a widespread practice among Pemex employees to illegally sell gasoline straight out the back door of the refinery (though illegal pipeline tapping by criminal gangs remains a significant problem). However, in TTL, the federal government removed almost all forms of oversight over the STPRM after the strike of 1988, and after six-and-a-half years, many Pemex officials have found that they can get away with just about anything as long as they don’t put up billboards advertising it.

[2] In OTL, La Quina was arrested in pretty much the exact same way on January 10, 1989.

[3] In OTL, such an explosion did happen. On April 22, 1992, a large amount of gasoline leaked into the Guadalajara sewers and ignited, destroying five miles’ worth of streets, killing over 200 people and gravely wounding a thousand more (Xanic von Bertrab, who was working for a local rag at the time, found out about the leak the day before the explosion, but the authorities didn’t listen to her in time to stop the tragedy). In TTL, the explosion itself has been butterflied away, but the abhorrent safety standards which let it happen have metastasized to Pemex installations in other parts of the country due to the lack of federal oversight.

[4] Actual name used by Pemex employees to refer to outside managers, so called because they are of unknown origin and have a habit of multiplying very quickly.

Last edited:

Now that is some cartoon-villain levels of greed and sociopathy.By the time Limón found out about the gas leak on the afternoon of March 4th, locals were already queuing up for their share of cut-rate gasoline, and he wasn’t about to send them home and lose out on two weeks’ worth of profits. So, rather than ordering an evacuation, Limón simply called in sick, retreated to his home on Salamanca’s affluent north end, called his assistant director and instructed him to carry on like any normal Sunday.

Gee, I wonder why!?But they struggled to respond in early October when TV Azteca joined the fray by introducing a new addition to its daily programming: roundtable discussions on the political and civic issues of the day, hosted by a panel of credentialed experts who all, by sheer coincidence, happened to be virulently opposed to the Labor Rights Law.

Great writing as usual, keep up the great work!

RamscoopRaider

Donor

You know if not for that note I would have probably complained about #2 but stranger than fiction. I will say whoever did that was not too concerned about taking La Quina alive, beyond armor effects can get nasty

Or when some Lois Lane type reporter finds out about Bartlett's fate. I'm assuming the narration isn't omniscient so the cat is bound to come out of the bag, but this whole "Historic Election" in the US has peaked my interest.Every update just ramps up tension and foreshadows ominously. When the top finally blows off and the civil war goes hot, it’s going to be bad.

Given George H. W. Bush is serving a second term, may I suggest as his Scotus appointments: Edith Jones for Byron White and Stephen Posner for Harry Blackmun.

I detected a minor inconsistency in the story:

So, in real-life, the Secretary of Tourism in Mexico in 1988 was Carlos Hank González until he became Secretary of Agriculture & Hydraulic Resources in 1990. (Four years later, the position would be abolished). Raul Salinas de Gortari, the elder brother of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, was never directly involved in Mexico's political landscape, but was involved in heavy corruption. He was eventually arrested and imprisoned for ordering the assassination of the PRI's Secretary General, but his conviction was later overturned.

In this timeline, Raul Salinas became Secretary of Tourism in 1988, instead of Carlos Hank, so that his brother could control him enough so that he won't do anything that's too corrupt. Raul's short time as Secretary of Tourism eventually allows him to become President (albeit as a puppet president by Manuel Bartlett Díaz, who is still Sec. of Interior). Later, Carlos Hank González becomes interim-president after Manuel Bartlett Díaz dies, but his term is cut short due to constitutional loopholes by President-elect Porfirio Muñoz Ledo.

My concern here is if Carlos Salinas never gave his brother a political role in real-life, what could have convinced Carlos Salinas to do so in the alternate timeline?

I know that having Raul Salinas as President of Mexico would have been shocking and frightening (especially if you know a lot about Mexican history), but perhaps it could have been more interesting to read about who could have been president after Carlos Salinas was assassinated without using his brother as a replacement. The fight (or alliance) between Carlos Hank and Manuel Bartlett would be very fun to read about.

Anyone have any thoughts on this?

So, in real-life, the Secretary of Tourism in Mexico in 1988 was Carlos Hank González until he became Secretary of Agriculture & Hydraulic Resources in 1990. (Four years later, the position would be abolished). Raul Salinas de Gortari, the elder brother of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, was never directly involved in Mexico's political landscape, but was involved in heavy corruption. He was eventually arrested and imprisoned for ordering the assassination of the PRI's Secretary General, but his conviction was later overturned.

In this timeline, Raul Salinas became Secretary of Tourism in 1988, instead of Carlos Hank, so that his brother could control him enough so that he won't do anything that's too corrupt. Raul's short time as Secretary of Tourism eventually allows him to become President (albeit as a puppet president by Manuel Bartlett Díaz, who is still Sec. of Interior). Later, Carlos Hank González becomes interim-president after Manuel Bartlett Díaz dies, but his term is cut short due to constitutional loopholes by President-elect Porfirio Muñoz Ledo.

My concern here is if Carlos Salinas never gave his brother a political role in real-life, what could have convinced Carlos Salinas to do so in the alternate timeline?

I know that having Raul Salinas as President of Mexico would have been shocking and frightening (especially if you know a lot about Mexican history), but perhaps it could have been more interesting to read about who could have been president after Carlos Salinas was assassinated without using his brother as a replacement. The fight (or alliance) between Carlos Hank and Manuel Bartlett would be very fun to read about.

Anyone have any thoughts on this?

Last edited:

Bookmark1995

Banned

Reading about Mexico, it is staggering to learn how even Mexican unions can be so corrupt, Jimmy Hoffa can come across as down to Earth guy.

I chalk it up to the different context created by the TL.My concern here is if Carlos Salinas never gave his brother a political role in real-life, what could have convinced Carlos Salinas to do so in the alternate timeline?

ITTL, Salinas' legitimacy is even weaker than it was IOTL because Cardenas has not gone along with the fraud, which has resulted in an agitated and restless populace that has lead protests and strikes against the regime (which have turned violent), as well as garnered international notice and condemnation. Placed in a situation much more precarious than OTL, I don't think it's a stretch to imagine Salinas acting differently.

The reasoning that Roberto gives in the TL makes sense to me: an attempt to keep Raul out of trouble by bringing him into a place where he can't act without impunity. Better to have him inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in, as they say. That it is, perhaps, "too clever by half" I think can be justified either as a desperate effort that Carlos didn't fully think through (it is a stressful time), or an attempt by Carlos to give himself a staunch ally in order to reinforce his legitimacy within the PRI itself, or possibly a combination of the two.

Last edited:

Plus I doubt Salinas thought he'd get assassinated. Raul's biggest perfidies ITTL were only doable because Manuel Bartlett used him as a pawn to control the government before he could be President himself. Carlos basically gave him a position where he couldn't really screw up in, while Bartlett threw him into a position where he could do everything wrong.I chalk it up to the different context created by the TL.

ITTL, Salinas' legitimacy is even weaker than it was IOTL because Cardenas has not gone along with it, which has lead to an agitated and restless populace that has lead protests and strikes against the regime (which have turned violent), as well as garnered international notice and condemnation. Placed in a situation much more precarious than OTL, I don't think it's a stretch to imagine Salinas acting differently.

The reasoning that Roberto gives in the TL makes sense to me: an attempt to keep Raul out of trouble by bringing him into a place where he can't act without impunity. Better to have him inside the tent pissing out than outside the tent pissing in, as they say. That it is, perhaps, "too clever by half" I think can be justified either as a desperate effort that Carlos didn't fully think through (it is a stressful time), or an attempt by Carlos to give himself a staunch ally in order to reinforce his legitimacy within the PRI itself, or possibly a combination of the two.

Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections

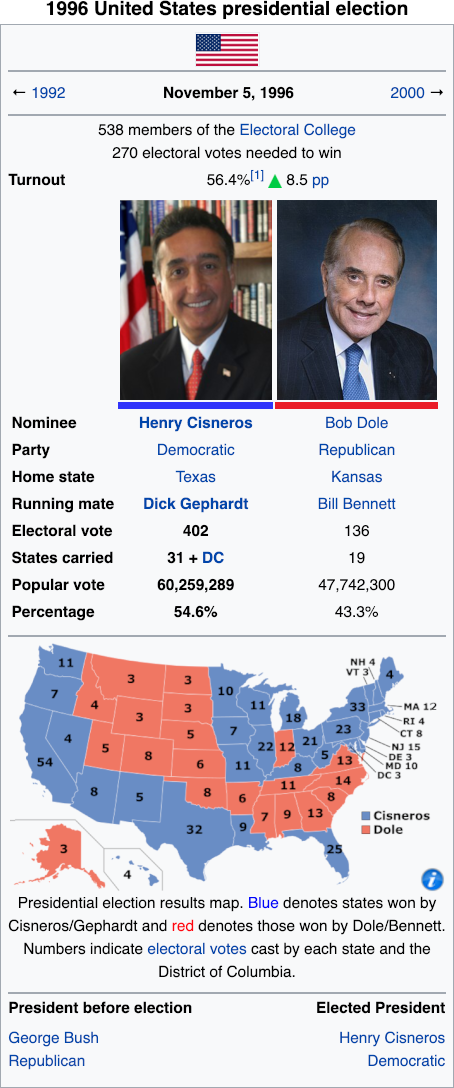

The United States presidential election of 1996 was a foregone conclusion. After sixteen straight years in power, the Republican Party had long overstayed its welcome. The previous eight years had undermined all of the party’s traditional selling points: prudent economic stewardship? Not likely after three years of middling growth rates. Law and order? Not while the drug epidemic raged and inner cities from Harlem to Crenshaw convulsed with crime. Strong international leadership? Not from the party that had fumbled the Gulf War and stood idly by as Mexico slid into dictatorship. President Bush, for his part, did little to help things—the statesmanlike stoicism which had helped him win in 1988 now made him appear out of touch and indifferent, and his whiny insistence that the economy was already recovering rang especially hollow to the many people who were scrounging for jobs or struggling to revive their businesses. The American public showed their antipathy toward the GOP in the 1994 midterms, which saw the Democrats expand their majorities in the House and Senate.

As election year drew closer, Republican voters and politicians alike were tired and demoralized. Just finding a nominee would be a challenge in and of itself, as potential heavy-hitters like Dan Quayle, Dick Lugar, John McCain, and Colin Powell all announced within months of the midterms that they would be sitting out the race. By New Year’s Eve 1995, the Republican field consisted almost entirely of oddballs and misfits: Pat Buchanan, the arch-conservative culture warrior who had harried President Bush in the primaries in 1992; Steve Forbes, businessman and editor of the magazine that bore his name; Bob Dornan, the California congressman best known for loudly accusing his adversaries of homosexuality; and Alan Keyes, a former U.N. official whose two previous attempts at elected office had both ended in landslide defeat. For much of the race, the only halfway “normal” candidate was former Congressman Jack Kemp, who, as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, had taken much of the blame for the dismal situation plaguing American cities. The Republican voter base was thoroughly relieved in early 1996 when the party leadership finally managed to recruit Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, who reluctantly entered the race in January, swept the primaries, and was formally nominated at the convention in Phoenix, choosing Education Secretary-turned-Drug Czar Bill Bennett as his running mate.

The Democratic field grew predictably crowded as various high-profile figures launched their campaigns. Former vice presidential nominee Bob Kerrey threw his hat into the ring, as did senators Al Gore and Tom Harkin and governors Jim Blanchard and Bill Clinton. But deep down, most of the party rank-and-file knew who the nominee would be before he even declared his candidacy. Ever since his election to the Senate in 1990, Henry Cisneros had seemed to speak for America’s voiceless: Hispanic immigrants, inner-city kids, drug addicts, and those who had been left behind by the rising tide of globalization. His legislative work showed that his interest in these groups went beyond empty rhetoric—the Weldon-Cisneros Act, passed in mid-1995, had created a raft of new incentives to dissuade U.S. firms from outsourcing production, saving tens of thousands of industrial jobs and turning the freshman Texas senator into a darling of organized labor. Cisneros had also profited immensely from his opposition to the PRI regime in Mexico. From the very beginning, he had been Manuel Bartlett’s fiercest enemy in Washington, suffering the condescending scorn of those who insisted on supporting the despot as a lesser evil to anarchy or communism. So when the true extent of Bartlett’s corruption was revealed, Cisneros gained a reputation not only as a paragon of moral courage, but also an astute judge of character with a sharp mind for diplomacy. On May 14, 1995, when Cisneros officially launched his presidential campaign before a throng of 40,000 cheering supporters in HemisFair Park in his hometown of San Antonio, one devout listener claimed to the Texas Tribune that the former mayor’s candidacy was divinely ordained.

Though Texas state law permitted him to run simultaneously for the Senate and the presidency, Senator Cisneros chose not to run for re-election, instead passing his seat on to another public atoner: Lena Guerrero, whose career had seemingly ended in 1991 when it was revealed she had lied on her resumé, but who made a stunning comeback by riding Cisneros’s coattails to victory over businessman Robert Mosbacher, Jr.

Cisneros’s path to the nomination was not without its obstacles. His opponents criticized him for his relative inexperience, political missteps (such as voting for the ROGUE STATES Act just days after lambasting it), and his personal failings, particularly the extramarital affair to which he had publicly confessed in 1989. But none of the critiques seemed to weigh him down. Years later, David McCullough would write that the youthful senator’s open, unqualified remorse proved an asset, rather than a liability, on the campaign trail—after four years of collective anxiety and insecurities, and with a national ego bruised and battered, the American people hungered not for the picture-perfect candidate with a model family and squeaky-clean past, but for the man who had forsaken his honor, won it back, and carried on through adversity. Henry Cisneros—a reformed adulterer, a father to a son with a horrible heart condition, and a Hispanic who had overcome the stigma of his race to reach high political office—fit the bill just perfectly.

Beyond the candidate’s past, the Cisneros campaign embodied a distinct theme of hope, renewal and change. In contrast to his opponents, most of whom were spouting off the same dry, fiscally-conservative talking points which had kneecapped Paul Tsongas in 1992, Cisneros touted a unique blend of public-sector development and private-sector empowerment dubbed by columnists both friendly and hostile as “business populism”. Pledging to solve America’s many problems by partnering the broad powers of government with the rugged efficiency of business, Cisneros’s platform seemed to resonate with the fickle, suburban moderates who had blocked Democrats’ path to the White House time after time. And unlike Tsongas, whose aggressive appeals to those voters had turned off urban minorities and working-class whites, Cisneros could point to his work in San Antonio, which he’d transformed from a sleepy, decaying city to a vibrant center of growth and culture, as well as his efforts in the Senate to protect industrial jobs, to prove that he was an ally of the blue as well as the white-collar voter. Cisneros clinched a majority of delegates within the first month of the primaries and was crowned to plentiful fanfare at the convention in Louisville. His choice of running mate, House Speaker Dick Gephardt, drew concerns about his lack of charisma, but Gephardt’s solid support from organized labor, as well as Cisneros’s own vast personal charms, put paid to those fears.

As the conventions gave way to full-on campaign season, some Democratic analysts worried Cisneros would look inexperienced next to the accomplished statesman Dole. But these fears were unfounded. In the debates, the septuagenarian Republican seemed tired and supercilious while the scion of San Antonio was enthusiastic and passionate. Nor were Cisneros’s strengths solely cosmetic: When Senator Dole attacked Cisneros’s plan to forgive most of Mexico’s debt, Senator Cisneros made a persuasive case that debt amnesty was necessary to restore stability and prosperity to Mexico and cut down on illegal immigration. While a lethargic Dole invoked high urban crime rates to frighten rural and suburban whites (a Nixonesque strategy which may indeed have helped him win a state or two), Cisneros placed himself above petty racial rivalries and promised to fundamentally reconstruct the American city while delivering solutions for all Americans. While Dole defended the tough-on-crime laws which had put hundreds of thousands of nonviolent offenders behind bars while utterly failing to solve the drug crisis, Cisneros expressed compassion for drug addicts and pledged to treat them not as criminals, but as victims. Vice presidential nominee Bill Bennett, whom Dole had chosen to add credibility on the drug issue, instead drew strident criticism for his part in allowing the crisis to spiral out of control.

On election day, the question was not whether or not Cisneros would win but how big of a margin he would win by. The answer, as it turned out, was pretty big: 402 votes in the electoral college and an eleven-point margin of the popular vote. Cisneros’s campaign not only won back all of the traditional Democratic strongholds, but also narrowly flipped several states which hadn’t voted blue in decades: Louisiana, Kentucky, as well as (thanks to high turnout among Latino voters, over 80% of whom cast their ballots for Cisneros) Arizona, Florida, and the senator’s own home state of Texas. History had been made—for the first time since its founding, the United States of America had elected a non-white President.

South of the border, reactions to the victory were ecstatic—not just because of the new President’s heritage, but also because of his promise to significantly reduce Mexican debt. For the moment, though, most Mexicans were far more preoccupied with political developments in their own country, particularly as the post-PRI party system began to take shape ahead of the hotly-anticipated Congressional elections of 1997.

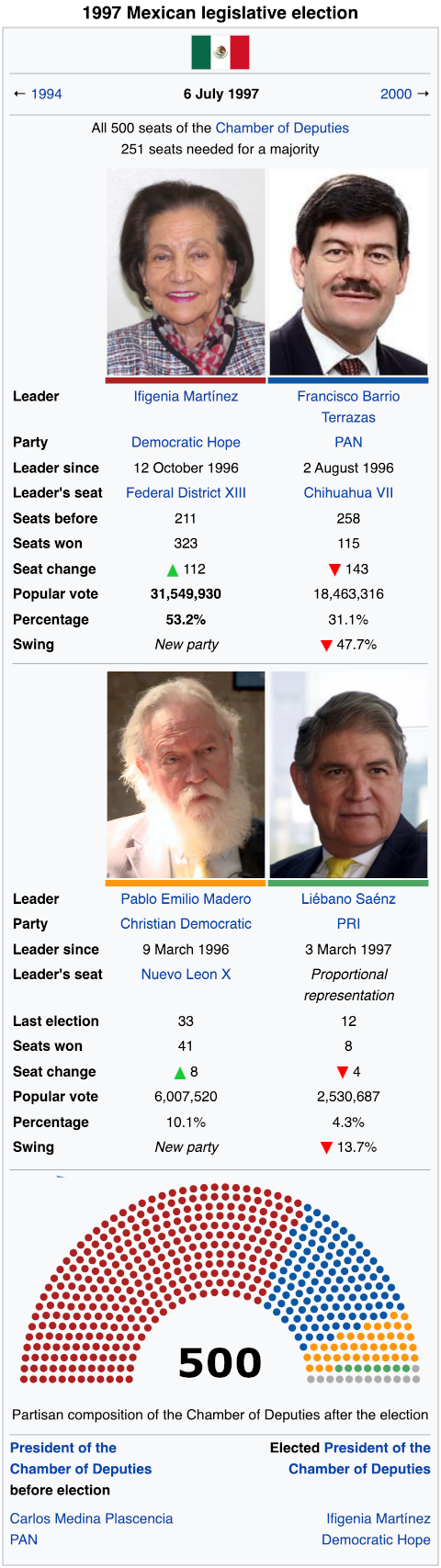

For three years, the PAN had held a commanding presence in Mexican politics. As the only opposition party in the election of 1994, the PAN had reaped almost all of the benefits from the PRI’s landslide defeat, capturing 413 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 112 in the Senate. But the following years would show just how disorganized and incoherent the party had become. Over the course of the 61st Congress, as the PAN’s social democratic left wing clashed with the conservative old guard over everything from labor reform, foreign policy, the Zapatistas and the welfare state, the burgeoning community of political columnists began to predict that a split of some kind was inevitable. It came sooner than expected. On April 13, 1996, more than a year out from the elections of 1997, several prominent panista progressives, including Mexico City Mayor Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, Senate President Pablo Gómez and Chamber of Deputies President Sergio Aguayo, announced the formation of a new political party: Esperanza Democrática, or Democratic Hope. Pledging to stand for the “rights of all workers and farmers” and the “principles of Cárdenas and Madero,” ED, as it soon became known, was instantly endorsed by all the major labor unions, and President Muñoz Ledo lent the new party his tacit support (though he stopped short of joining, determined as he was to rule as an independent).

Within two weeks, 136 panista deputies—one-third of the entire PAN caucus—had joined the new, left-wing party, as had 57 of the 72 remaining priístas. In the Senate, the picture was even worse, as 43 of the PAN’s 112 senators announced their defection. Aguayo and Gómez instantly lost their leadership positions in the Chamber and the Senate and were replaced, respectively, by conservative panistas Carlos Medina Plascencia and Ernesto Ruffo Appel. But the new party had left its mark: though it had kept its majorities in both chambers, the PAN presence was greatly reduced, and its credibility as a governing party had taken a serious hit.

Perhaps more damaging, however, was the response of the party leaders. Within weeks of the split, PAN godfather Diego Fernández de Cevallos called a conclave of the most prominent panistas at his home in the Bosque de Chapultepec, where it became clear that, even without the breakaway left, the PAN’s remaining faithfuls did not agree on how the party should face the future. Fernández de Cevallos, Luis Álvarez, and other old-liners demanded that the PAN become the “conscience of Mexico” by returning to its traditional, Catholic roots. But younger, more technocratic members insisted that the party should work to capture the liberal-minded, white-collar middle class by modernizing and moving to the center. Press correspondents noted the suspicion with which senators, deputies and activists needled each other over their partisan loyalties, with deputy Carlos María Abascal declaring that there were “traitors still in our midst”. In a column in the left-leaning newspaper Nuevo Siglo, PAN-turned-ED deputy Julio Scherer sneered that the PAN’s attitude toward dissent was little more tolerant than that of the PRI under Bartlett.

For several months, the PAN’s two remaining factions battled over policy, messaging, and control over the Congressional legislative calendar. The repeated recriminations cost the party a further eighteen seats in the Chamber of Deputies and six in the Senate. Through most of the fall 1996 session, ortodoxo and modernista legislators squabbled over votes and committee assignments, culminating in a dramatic attempt in October to unseat Carlos Medina Plascencia and Ernesto Ruffo Appel from their leadership positions. The bid failed, and some overly optimistic technocrats declared that their camp had triumphed. Three days later, Fernández de Cevallos, Carlos María Abascal and several other prominent ortodoxos declared the birth of yet another breakaway group: the Christian Democratic Party. Twenty-four of the PAN’s 277 remaining deputies jumped ship, as did nine of its 63 remaining senators—not quite the massacre some had expected, but enough to cut down the PAN majority in the Chamber to a measly eight seats and remove it entirely in the Senate (where Ruffo Appel survived as president only by making a deal with the ED caucus to advance legislation creating a permanent envoy from Los Pinos to the State of Zapata). The resulting ideological chaos would consume the PAN for most of 1997.

Meanwhile, as the PAN convulsed, Democratic Hope was busy rediscovering the time-aged art of electioneering. Elections to the Chamber of Deputies were scheduled for July 6, 1997, and the fledgling party’s leadership set to work rebuilding and refining the well-oiled electoral machine which had delivered Muñoz Ledo’s staggering landslide three years earlier. ED was well-equipped for election season: the activist labor unions, whose strident campaigning efforts on Muñoz Ledo’s behalf had delivered millions of votes back in 1994, had all announced their support. Many of the party’s new deputies hailed from rural districts where they had extensive contacts with local power brokers, allowing them to access isolated communities which would otherwise have been politically inaccessible. In addition, many of post-PRI Mexico’s most popular political figures, including President Muñoz Ledo, Sergio Aguayo and Mexico City Mayor Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, had either joined the party or lent it their unspoken support. And the momentum was showing. By March of 1997, ED legislators had taken control of the state legislatures of Coahuila and Morelos and had nominated a full slate of candidates for the federal elections.

While ED prepared itself, President Muñoz Ledo worked to make the elections of 1997 the most free and fair in Mexican history. In 1995, Muñoz Ledo’s administration had formed the Institute of Electoral Security under the leadership of political scientist José Woldenberg. Armed with a $1.2 billion budget, the Institute had trained nearly half a million people, chosen at random from the voter registration rolls, to man the polls, backed up by opposition poll-watchers in almost every voting place from Tijuana to Cancun. The Institute had also designed a special, narrow voting booth wide enough to fit only one person, allowing every voter to cast their ballot without fear of being watched. When election day came on July 6, the polling went very smoothly. TV Azteca reported a few “irregularities”—a sudden power outage at one polling place in Tonatico, ballot boxes pre-stuffed for the PAN at a few stations in suburban Monterrey, and one quixotic, pistol-brandishing PRI holdover in rural Campeche who made off with a few boxes—but overall, the vote was cleaner and more orderly than it had ever been in Mexican history. President Muñoz Ledo would later write about how proud he had been to turn down Defense Secretary Gutiérrez Rebollo’s offer to have the Army watch over the polls as it had done in 1994, a decision which drew praise from international observers (although some have since pointed out that the Army only felt comfortable with Muñoz Ledo’s refusal because it feared no threat to its drug-trafficking activities from any of the competing parties).

To this day, the election results remain a matter of debate. Many panistas still grumble that they might have done better if the PDC hadn’t split the right-wing vote, but subsequent analyses have shown that the Christian Democrats did not run candidates in enough seats to cause a large-scale defeat. Edecos have found other explanations: that ED had a more solid lock over its key constituencies than the PAN did over its own, or that voters had grown tired with the PAN’s dysfunctionality and factionalism. But among supporters, the most popular narrative is that ED’s message simply resonated better with the electorate. Since mid-1996, when key elements of his agenda stalled in the increasingly fractious Congress, President Muñoz Ledo had been advocating for an entirely new constitution, claiming that the Constitution of 1917 was too limited and too easily-abused to allow for the kind of sweeping changes Mexico demanded. Democratic Hope had made this the central plank of their platform, calling for a constitutional convention which they hoped would allow for deep, fundamental reforms to the welfare state, the ejido system, and the balance of power between the states and the federal government. In contrast to the PAN, which (during the short interludes between its intraparty squabbles) offered a more restrained, liberal platform involving a lowering of barriers to international trade, deregulation of business and privatization of some state-owned enterprises, ED promised to strive boldly ahead to forge the institutional structure of post-PRI Mexico and continue the work of what Octavio Paz had already dubbed “the Second Mexican Revolution”. Democratic Hope won, supporters say, because it embodied just that: hope.

Whatever the reason, ED’s victory was decisive. With 53% of the popular vote, the party captured 323 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, just shy of the two-thirds needed to amend the Constitution but still more than enough to pass crucial legislation. The Senate, which was not due for re-election until 2000, remained under split control, but a partnership with the Christian Democrats soon gave ED the leadership of the upper chamber. In the concurrent state elections, things were less bleak for the PAN, which captured the governorships of Querérato, Nuevo León and San Luis Potosí and retaining control of the state legislatures in Guanajuato and Baja California. But ED held its own both outside the capital city (where edecos were elected governor in Colima and Campeche) and inside it (where Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas won the first-ever election for Mayor of Mexico City).

But while the winners and losers were clear, the elections of 1997 were a triumph for everyone in Mexico. By far the freest and the most pluralistic in Mexican history, they proved that the country could function and thrive without PRI leadership, and the PAN’s and PDC’s genuine, if begrudging, concessions showed that the leaders of opposing parties could be trusted to win and lose with grace. Perhaps the only true losers were the PRI: having lost most of its remaining legislators to the opposition over the course of the 61st Congress, the former party of power was left dazed and rudderless without a clear national leader, message, organization, or fundraising strategy. Utterly annihilated on the grassroots level, not one of the PRI’s candidates won his district, and “the party of crooks, thieves and narcotraficantes” (as dubbed by newly-elected ED deputy Carlos Monsiváis) was reduced to a pitiful eight seats, all awarded by proportional representation. The old regime was well and truly dead.

To mark the occasion, on July 15, 1997, U.S. President Henry Cisneros signed a piece of legislation which reduced Mexico’s foreign debt from $31 billion to $10 billion. The following week, President Cisneros made his first state visit south of the Rio Grande, where he stood side-by-side with President Muñoz Ledo on the front steps of Los Pinos and declared in fluent Spanish that a new beginning had been reached in Mexican-American relations. Another beginning dawned soon after: on September 1, 1997, the 62nd Congress of the Union was sworn in at the newly-rebuilt Palace of San Lázaro, and the new President of the Chamber of Deputies, Ifigenia Martínez, declared that “the new Mexico has just been born”.

The following three years would lay the foundation for how exactly the new Mexico would look.

As election year drew closer, Republican voters and politicians alike were tired and demoralized. Just finding a nominee would be a challenge in and of itself, as potential heavy-hitters like Dan Quayle, Dick Lugar, John McCain, and Colin Powell all announced within months of the midterms that they would be sitting out the race. By New Year’s Eve 1995, the Republican field consisted almost entirely of oddballs and misfits: Pat Buchanan, the arch-conservative culture warrior who had harried President Bush in the primaries in 1992; Steve Forbes, businessman and editor of the magazine that bore his name; Bob Dornan, the California congressman best known for loudly accusing his adversaries of homosexuality; and Alan Keyes, a former U.N. official whose two previous attempts at elected office had both ended in landslide defeat. For much of the race, the only halfway “normal” candidate was former Congressman Jack Kemp, who, as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, had taken much of the blame for the dismal situation plaguing American cities. The Republican voter base was thoroughly relieved in early 1996 when the party leadership finally managed to recruit Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, who reluctantly entered the race in January, swept the primaries, and was formally nominated at the convention in Phoenix, choosing Education Secretary-turned-Drug Czar Bill Bennett as his running mate.