Between Dreams and Nightmares

Haile Selassie Gugsa with German Advisors

The Four Horsemen of Africa

The will produced by Ras Gugsa Welle on the death of his wife, Empress Zewditu, which named him as her successor, was disputed from the start by the various factions in Ethiopia. By 1930 the ruling Solomonic Dynasty had turned into a complex welter of interconnected and internecine relations with multiple feuding branches and numerous contenders to the throne. While Gugsa Welle made his claim to the throne by way of his wife, he was also a decent candidate for the throne in his own right as a descendent of one of the other branches of the Solomonic dynasty. Beyond that, Gugsa Welle was notable for not only his administrative and military talents, but was also renowned as a poet and dedicated bibliophile with a noted piety which drew support from the church to him. However, Gugsa Welle had good reason to hold a grudge against many of the more conservative Ethiopian nobles, who had worked constantly to undermine his beloved aunt Dowager Empress Taytu Betul, had allowed Gugsa Welle to be imprisoned and tortured cruelly under Lej Iyasu's rule, had forced him from his beloved wife for nearly a decade and had consistently sought to undermine his position as Regent in the years following the death of Tafari Makonnen.

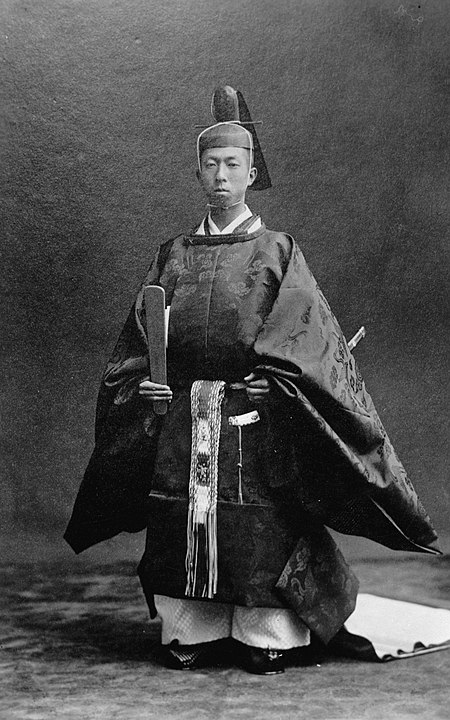

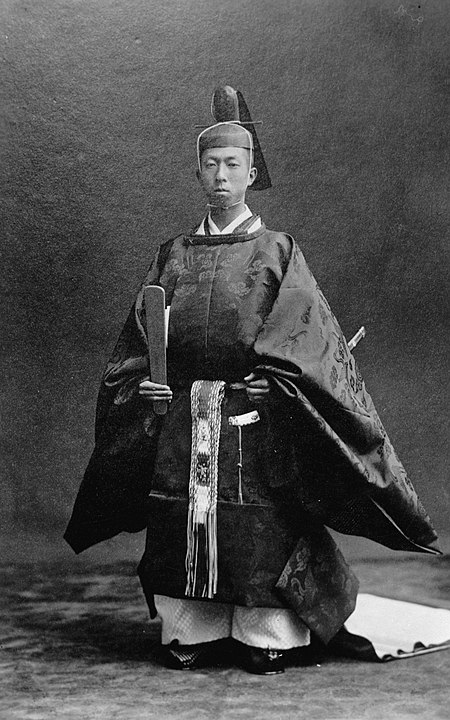

Thus, fearing Gugsa Welle's revenge should he be allowed to ascend the throne, the majority of the conservative nobility looked for alternate candidates to the throne. While a small minority threw their support behind the imprisoned, and potentially still Muslim, Lej Iyasu - a member of the Shewan branch of the dynasty to which Empress Zewditu had belonged as well, it would be in the Tigrayan branch which was to see the greatest degree of support. While Gugsa Araya Selassie and his son Haile Selassie Gugsa had grown into the inheritors of Ras Tafari Makonnen's role as leaders of the modernist faction in Ethiopia, the Tigrayans of the Solomonic Dynasty had two, bitterly hostile lines of descent from the former Emperor Yohannes IV who contended for leadership. While Gugsa Araya Selassie's father, Araya Selassie Yohannes, was the elder "legitimate" son of Yohannes IV, he was not his only son. A younger "natural born" son by the name of Ras Mengesha Yohannes and his successors had grown to be the bane of Gugsa Araya Selassie's existence for much of his life as clashes over the inheritance of their Tigrayan kingdom consumed the two branches. Thus, while Gugsa Araya Selassie had emerged as a leading moderniser, his cousin Ras Seyoum Mengesha, the son of Ras Mengesha Yohannes, had come to be known as one of the staunchest conservatives in the country and soon emerged as the favourite successor for the majority of the conservative nobility.

While each of these candidates had their supporters, Gugsa Welle amongst the Gondorans of the north-west and the Church, Iyasu amongst a minority of the Shewan nobility and in the more Muslim south, Araya Selassie in eastern Tigray, Harar and Shewa and Seyoum Mengesha in western Tigray and Shewa, there were major power differences between them. Gugsa Welle held the capital of Addis Ababa, and with it the keys to the treasury, imperial authority and the support of the military high command in the form of Commander-in-Chief Balcha Safo, while Iyasu remained under house arrest in Harar and at the mercy of Araya Selassie's followers, who were to prove merciless. The moment word reached Harar that some were proclaiming Iyasu as the rightful Emperor, Haile Selassie Gugsa, who was serving as governor in the region after coopting Tafari Makonnen's ties to the locals through his marriage to Tafari's daughter, had Iyasu brought before him and put to death, the particular method remaining the subject of considerable rumour, with everything from a firing squad or forced suicide to him being fed to lions being circulating amongst the populace.

Thus, the first of the four contenders was extinguished before he even had a chance to make his bid for power. While this move had the effect of securing the south for the Modernists, it was to considerably weaken the faction's standing amongst the nobility, who felt that the brutal murder of a high noble and former Emperor set a worrying precedent for the conflict to come, whereas prior succession strife had usually seen the nobility large spared mass death, with exiles, imprisonment or ritual humiliation in the wake of defeat far more common than execution or outright murder. The result was the steady erosion of support for Gugsa Araya Selassie in the north, to the benefit of Seyoum Mengesha, turning the latter into Gugsa Welle's most prominent rival. This weakening of the modernist cause was to result in Gugsa Welle turning his full attentions to Seyoum Mengesha and his launching of the Imperial Army in Addis Ababa northward towards Gondar, with plans for the reclamation of Tigray. The two major conservative candidates rushed to muster their forces over the course of the middle of 1930 while the Modernists retreated into the less populous south.

When Araya Selassie arrived in Harar, he was rumored to have launched into a loud, expletive-laden condemnation of his son for the bitter blow Iyasu's death had dealt Selassie's cause. Ultimately a far more conservative figure personally than his leadership of the Modernists might suggest, Araya Selassie greatly disliked his son's total disregard for tradition and custom, semi-irreligiosity and seeming willingness to do anything to achieve his goals. This became particularly clear when Haile Selassie Gugsa proposed reaching out to the local Muslim population with promises of lessened religious discrimination to win their support, a proposal which his father shut down without discussion, disgusted at the mere thought. This tension within the modernist faction, who by and large were made up mostly of younger men disenchanted with tradition and custom, resulted in a great deal of tension, as Haile Selassie Gugsa enjoyed considerably greater support amongst his father's putative supporters than the claimant himself. Thus, with the modernisers divided amongst their leadership, the conservatives were to take centre stage during the first phases of the emergent Ethiopian Civil War (1).

The first major clashes of the civil war would occur in the north between the Welleian and Mengheshan faction of conservatives across the two sprawling provinces of Wello and Gondar. While Mengesha's initial support had largely been limited to Tigray itself, he found a rapidly growing surge of support across much of the less populous western provinces, and as such his faction soon grew into a true threat to Gugsa Welle. Gugsa Welle thus set out to isolate and defeat Mengesha in Tigray before he could reach out and begin to organize his western supporters. The result was to turn the two major passes from the central Plateau into Tigray into a bitterly contested battlefield. While Balcha Safo led the Imperial Army of the Center north-east from Addis Ababa, Gugsa Welle himself rushed to his native Gondar and began mustering the regional levies while passing over much of the administrative work to a variety of family members and church officials. However, the Welleians were not to prove the only actors in this drama, as Mengesha dispatched a holding force to the south to slow down Balcha Safo's forces while going on the offensive further north against the more disorganised Gondarans. Advancing with his well-trained personal army, Mengesha caught Gugsa Welle by surprise with his aggression and had already secured the two towns of Debark and Dabat north of the City of Gondar before the Gondarans could form into an army.

While Mengesha's force was outnumbered by almost a third, he proved undaunted, rushing to catch his rival by surprise. The result was the Battle of Gondar fought on the 18th of August 1930, in which the recently formed Gondaran Army found itself forced to battle barely a week after forming by the far more cohesive Tigrayans. Notably, this battle was largely devoid of any of the modern accruements of war and was determined more by the bravery of Mengesha's retinue than anything else. After the levies clashed, Mengesha exploited a hole between the center and left wing of the Gondaran army to break the enemy formation, charging into the gap in a classic cavalry charge and splintering the Gondaran defenders. While Gugsa Welle struggled to withdraw, using the much more cohesive right-wing to shield the retreating center, there was nothing he could do for the collapsing left. By the end of the day, the Welleians had been forced to abandon Gondar and retreat southward in hopes of linking up with Balcha Safo while Mengesha led a victory parade through the streets of the ancient ancestral city of his rival.

However, Mengesha could not rest long on his laurels, for Balcha Safo had only been slowed, not stopped, by the blocking force dispatched to stop the Imperial Central Army. The fall of Gondar opened up communications to the west and allowed Mengesha to reinforce his bloodied but victorious army, swelling the force to some 50,000, a match for the equally reinforced Imperial Central Army which had been advancing into Tigray before Gugsa Welle's arrival forced Balcha Safo to reorient his force towards Gondar. What followed was a three-month period of positional warfare across much of the Province of Gondar as the weather grew increasingly horrendous, eventually forcing the two rival armies to retreat into winter quarters, the Mengeshans in Gondar and the Welleians to the central town of Weldiya wherefrom they could advance north into Tigray, westward into Gondar or southward to Addis Ababa should the need arise, thus bringing the first year of the conflict to a relatively quiet end. The winter of 1930-31 was to see a further entrenchment of all three candidates to the throne, with Gugsa Araya Selassie finally giving way to his son's entreaties to begin recruiting amongst the southerners, with Haile Selassie Gugsa soon forming a nondenominational force, of which the elite proved surprisingly well armed as Haile Selassie opened up contact to the Germans in Somaliland without his father's knowledge. The new year would see the two conservative forces clash once more, even as the modernists mustered their forces to sweep to victory.

The resumption of hostilities in early spring of 1931 was marked by a determination on the side of both conservative candidates to determine a winner. The result was a series of escalating skirmishes fought on the rugged, largely rural landscape between Weldiya and Gondar, finally coming into direct contact along two ridgelines between the villages of Gayint and Debre Zebit a short distance from the Weldiya-Gondar road. This time Mengesha was to find his position less favorable than at Gondar, for although his army had grown to outnumber his opponent by nearly 15,000 men the Welleians had stronger cohesion and contained the modernized troops of the Central Army. Reluctant to open himself up to a counter-attack, Mengesha held his army back, daring his enemy to make the first assault. With either army located atop a ridge, it was easy to shift forces back and forth in relative secrecy and to anchor a defensive position, making the aggressor likely to overextend. Nonetheless, Gugsa Welle was a wily opponent who was well aware of such fact, leading him to rely on the one point of advantage held by his forces, modern arms. The, by global standards horrifically outdated, artillery thus opened fire on the Mengeshans. Over the course of half a day this bombardment continued as Gugsa Welle sought to push his opponent into attacking first, with Mengesha finding himself under ever greater pressure from his noblemen to do just that.

However, it would be Balcha Safo, commanding the Welleian levies. who blinked first, ordering an attack when he became convinced that the enemy force was on the brink of collapse. While Gugsa Welle scrambled to figure out why his levies were suddenly advancing, Mengesha saw his opportunity and ordered an all-out assault by his levies. As the two levies slammed home between the ridges, the Mengeshan cavalry launched themselves into the chaos without orders, seeking to cut through the enemy levies as they had at Gondar, only to stall out, becoming bogged down in the melee. This allowed Gugsa Welle to send his much more professional modern infantry to the rear of the levies, allowing them to begin firing into the bloody melee over the heads of their levies. This sudden added pressure turned the battle against the Mengeshans and saw dozens of prominent noblemen killed, their colorful dress making them obvious targets for the rifle-armed infantry. Thrown into disarray, the Mengeshans began to collapse under the pressure while Mengesha ordered his army to retreat, soon seeing his army fall apart entirely when Gugsa Welle sent in his own cavalry to mop up the enemy. While hundreds of rebel noblemen were captured and nearly fifteen thousand Mengeshan levies were killed, the commander himself was able to make his escape with his bodyguard, retreating to Gondar before continuing on to Tigray. However, before Gugsa Welle could follow up on the victorious Battle of Debre Zebit and finally crush his rival, word from the south arrived, Gugsa Araya Selassie and the modernists were marching for Addis Ababa (2).

When word reached Harar of the skirmishes in the leadup to the Battle of Debre Zebit, the modernists decided to act. While Haile Selassie Gugsa was left behind to maintain order in the rear, his father having grown to greatly dislike Haile, Gugsa Araya Selassie mustered an army numbering nearly 60,000 and set out for Addis Ababa. As word of this reached Gugsa Welle, he suddenly came to the sudden realization that he had massively underestimated the modernists. Using the rise of the modernists, and particularly their widespread recruitment of Muslim levies, to drum up anti-Muslim sentiment amongst both Welleian and Mengeshan conservatives, Gugsa Welle was able to recruit massively from amongst the recently captured nobility, in the process recruiting nearly half of their levies and boosting his battle-hardened army to a full 80,000 men. While leaving Balcha Safo to mop up the remnants of the Mengeshan resistance, Gugsa Welle set out southward with the bulk of his army in a race against the modernists. Ultimately, it would be Gugsa Welle who arrived in the capital first, arriving barely two days before the modernists.

The resultant two-month Siege of Addis Ababa saw the two sides dug in around the south-eastern edge of the city. Daily skirmishes occurred, but the majority of the fighting was left to the rifle-armed professional troops on the side of Gugsa Welle and Araya Selassie's German-armed elites trained by Haile Selassie Gugsa. As the fighting ground on, and the northern levies, many of whom had been in the field for nearly half a year, leaving their families to manage their subsistence farms by themselves, grew increasingly riotous in the face of a seemingly never-ending campaign. As the pressure grew to act for a conclusive action to end the conflict grew, Gugsa Welle began to consider his options. Ultimately it would be the ultra-conservative Ras Kassa Haile Darge, one of the most prominent of Gugsa Welle's original backers, who came with a solution to his leader's troubles. Leading a powerful force of cavalry on a long and dangerous march through the mountains south of Addis Ababa, Kassa Haile emerged on the plateau behind the modernists during the night of the 18th of July, sending a signal flair into the air to let Gugsa Welle know of their success.

What followed was the Battle of Addis Ababa, fought on the 19th of July, which first saw Gugsa Welle's levies thrown forward against the modernist positions with the rifle-armed infantry in support to pin them in place before Kassa Haile launched a charge into the modernist rear. Caught by surprise, the modernists struggled to pull out while Araya Selassie was caught up in a pocket of resistance by the cavalry and killed. Taking over leadership of the army was Haille Selassie Gugsa's brother-in-law Desta Damtew, who sought to save what he could in the retreat, allowing most of the rifle-armed infantry, modern artillery and cavalry to make a retreat while sacrificing the predominately Muslim levies to slow the pursuit which followed. Hunted, the retreating army continued to shed men to rear-guard actions, desertions and exhaustion, finally straggling into Harar where Haile Selassie Gugsa had prepared defences to repel the pursuers. The death of his father paved a path for Haile Selassie Gugsa to take up leadership of the crisis-struck modernists, who were reeling from the defeat. However, Haile Selassie was able to whip up support for his leadership, silencing what little dissent existed to his authority, and turned to foreign powers for assistance, arranging a meeting with the Germans in Somaliland in hopes of negotiating aid against the surging conservatives.

In the meanwhile a triumphant Gugsa Welle, believing his enemies totally defeated and having dispatched Kassa Haile to deal with the modernists as he had Balcha Safo to Tigray, retired to Addis Ababa after sending home the discontented levies and western noblemen as the work of rebuilding his crisis struck realm came under way. The first Gugsa Welle knew of the German entry into the civil war was the arrival of a panicked messenger on the 29th of August 1931 informing the putative Emperor that his pursuit force had been crushed by the sudden appearance of a foreign army. Armed with copious light tanks, airplanes, machine guns and portable artillery, the German Expeditionary Force had swept Kassa Haile's army before it like so much dust, with the modernists once again marching for Addis Ababa with renewed vigor, having secured a major shipment of arms from the Germans and recruited further forces from the increasingly depleted south.

Gugsa Welle sought to muster his recently dispersed army at Addis Ababa, but by the time the modernists and their German allies had arrived before the city on the 13th of September he had only been able to scrounge up some 20,000 men in addition to the 10,000 men of the Central Imperial Army. This army proved insufficient to deal with the oncoming attackers, who used strafing airplanes, effectively impenetrable light tanks and machineguns to crush all opposition, with Gugsa Welle captured and executed by modernist forces under Haile Selassie Gugsa's command. The capture of Addis Ababa allowed Haile Selassie to declare himself Emperor, being crowned by a clergy at gunpoint as Negusa Nagast Haile Selassie I, even as the dispersed conservative nobility sought to form a scattered resistance to the suddenly victorious modernists, only to find their forces scattered by the wing of fighters purchased by Haile Selassie on credit and armed by German advisors and Ethiopian cadets.

While German advisors were soon swarming to attend Haile Selassie's court, Seyoum Mengesha was trying to drum up support for another go at the crown, securing the backing of Balcha Safo, only to see his home base of Tigray overrun by modernist troops armed with German weapons. On the run and with his army shedding ever more support by the day, Mengesha would disappear into the countryside, making his way gradually westward over the following winter. When the German expeditionary force departed Ethiopia that following spring Mengesha and Balcha Safo would raise the banner of rebellion once more, this time in the province of Illubabor. However, this uprising would be put down within two weeks through the use of the aforementioned fighters and a rapid-action force of modernist cavalry, Mengesha finding himself forced to flee into the Saharan Desert, where after he disappeared from the historical record while Balcha Safo was captured, put on trial and executed. The Modernists had emerged victorious in the Ethiopian Civil War, but in the process had sold out their country entirely to the Germans, who soon took control of the country's foreign and trade policy, even as German industrial, political and military advisors found themselves welcomed into the Ethiopian court with open arms by Haile Selassie (3).

Footnotes:

(1) I am sorry about all the complicated names and the various royal branches, it gets quite complicated but hopefully people understood. There are four candidates to begin with - Gugsa Welle from Gondar in the north-west, the cousins Araya Selassie and Seyoum Mengesha from Tigray in the north-east split with the east under the former and the west under the latter (although Araya Selassie has a lot more support elsewhere due to his leadership of the modernists which he inherited from Tafari Makonnen) and Lij Iyasu who was from Shewa but whose support for Islam might have gained him support in the south had Haile Selassie Gugsa not killed him. From my read of prior succession struggles, they seem to be surprisingly easy-going as to the fate of the high nobility on the side of the loser - rather they preferred blinding, placing people into the church or sending them into exile over killing them when they didn't just pardon them or place them under house arrest (although there are a good number of claimants who ended up dying in battle). The death of Iyasu, while securing the south for the Modernists and with it connection to the outside world, severely damages the faction's standing amongst the nobility and results in their loss of support in more conservative regions in the north. This allows Seyoum Mengesha to really profit from this development, setting him up as the second largest contender to the throne and Gugsa Welle's greatest rival.

(2) Ultimately, what decides who wins the clash between the conservatives is that Gugsa Welle has access to the modernized forces established by Ras Tafari Makonnen. The clashes are bloody, and particularly the levies pay heavily, but it is notable that the Battle of Debre Zebit sees the death of a large number of noblemen and an even larger number of nobles captured. While Mengesha is able to make his escape, his defeat is absolutely devastating and sees him reduced to his home province for support - and even here, there remain a good portion of the population more inclined towards Gugsa Araya Selassie than Seyoum Mengesha.

(3) And so ends the effective independence of the last independent state in Africa. Gugsa Welle really seemed to have won it all, but the immense technological advantage which the Germans wield, as well as the support of a significant portion of the local population (although support for this foreign intervention was lukewarm at best even in modernist circles) really mean that he has little chance of success. Mengesha finds himself falling precipitously from major claimant to the throne, to little better than a back-country bandit. It is worth noting that the Germans don't actually have any military forces in Ethiopia outside of a concession in Addis Ababa and their various advisors. The relationship here is more like some of the early 1800s colonial relationships in India or Iran during the Great Game than anything like the total control exercised in much of the rest of Africa. Ethiopia is more like a client state of Germany than an out-and-out colony in other words.

Colonial Residents in British East Africa seek refuge in British enclaves

The British African Famines of 1931-35 were to strike the various parts of the British Empire in Africa with greatly varied degrees of impact, but nevertheless would play absolute havoc with British power and authority in Africa. At the heart of the crisis lay the aftermath of the 1925 US-UK Trade Agreement which had opened up the British colonies in Africa to American agricultural imports, serving as a safety valve for the grossly over-capacity American agricultural sector. However, in the process, local agricultural produce had seen a dramatic collapse in prices, putting most farmers above the level of subsistence out of business if they had not had the foresight to shift their production towards various cash crops. At the same time, the rural population of British Africa began to seek better opportunities on those emerging large cash-crop plantations, in the numerous mines or in the growing cities of British Africa, resulting in a sudden swelling of the urban populace, only sustainable in the short run due to the availability of cheap American produce.

However, with the emergence of the drought known as the Dust Bowl in America beginning in the late 1920s and rapidly escalating over the first half of the 1930s, this ready supply of food stuffs began to shrink with uncommon rapidity, with the result that by the end of 1930 many major African towns and cities were experiencing intermittent food shortages, with some of the shortfall made up by purchasing from the large population of subsistence farmers dotted across British Africa and various other emergency measures. By 1931, the situation had grown particularly dire in British West Africa, with many Nigerian cities seeing major food shortages and the first inklings of famine.

This was met with a relatively prompt and capable response by the colonial administration in the region, with the recently appointed Governor Sir Bernard Henry Bourdillon negotiating with local chiefs for a share of their produce and working to shift food from the relatively untouched northern provinces to the greatly impacted south. In the process Bourdillon demonstrated a surprising capacity for managing cross-communal relations, securing help from the Muslim North for the Christian South while working with the French colonial government in the neighboring colonial states to secure further famine relief. By the end of the year, the troubles in West Africa had largely been resolved with the death-count kept below 10,000 and a renewed colonial emphasis on local food production would largely make up the shortfall from America by late 1932.

While West Africa had been the first afflicted it was also to prove the least impacted region of the British Empire in Africa after the Sudan. The region least reliant on American produce, the Sudan would instead be marked by the disruptions on its borders in both north and south which caused food shortages - the Ethiopian Civil War cutting Nilotic trade connections for several years while Egyptian warmongering saw relations between the Sudanese colonial administration and that in Egypt grow particularly frosty with a resultant drying up of cross-border trade. The fact that the vast majority of the populace lived as subsistence farmers or nomadic pastoralists meant that the impact of these shortages was largely limited to the few cities and towns in the region, with Khartoum experiencing intermittent food shortages between mid-1931 and mid-1933, although never to the point of causing a collapse in order or mass deaths. Western and Northern Africa thus escaped the crisis by and large. Instead, it would prove to be East and South Africa which were to be laid low by the crises which erupted during the first half of the 1930s (4).

In order to understand the crisis in East Africa, it is necessary to understand how the leadership of the colony had governed the colony in the prior decade. The first colonial administrator of the post-war period had been Sir Horace Archer Byatt, whose approach had emphasised the revival of African institutions and the encouragement of limited local rule, a stance which was bitterly opposed by the Conservatives who were swift to appoint Sir Donald Cameron, Byatt's opposite in all regards including in colonial policy, to replace him. For the following eight years Cameron had overseen East African affairs, developing a system of more direct rule in place of local autonomy involving white settlers and, often Indian, administrators in an informal advisory council which helped him rule the colony. It was on the basis of recommendations from these figures that Cameron essentially tossed aside East Africa's own nascent food production industry in favor of massive cash-crop plantations run by white settlers. East Africa was marked by the savannah more than any of the other areas of British Africa, which left less of a subsistence farming population and more of a semi-nomadic pastoralist populace, who increasingly turned to cheap American animal feedstock and grew their precious herds to previously unimagined sizes, in the process putting a greater strain on the region's natural resources.

Thus, when access to the American feedstock suddenly dipped, before collapsing in 1933, these massive herds were now forced to feed off the land, which soon saw entire swathes of land denuded in the rush to secure food for the herds. Before long, the herds began to run out of food and soon after began to die off in shocking numbers. This double blow, in which the countryside was denuded of animal feed and the subsequent mass die-out of the massive herds, sent shockwaves through the native populace, which suddenly found itself in deep crisis by the tail end of 1932. Tens of thousands migrated into the cities of the coast and the Nairobi region in the months that followed, bringing with them their mouths and stomachs, and little else. The result was a sudden and massive increase in the urban population just as American food exports reached their nadir, resulting in massive food shortages across the colony.

While Cameron tried to resolve the crisis as best he could, he lacked the resources and friendly partners which had allowed West Africa to weather the storm, and as such even as the South Mesopotamia Famine was reaching its apex, the situation in East Africa was spinning increasingly out of control. Wave after wave of calamity struck, as a cruel cycle developed, reduced animal feed would result in deaths amongst the great cattle herds, which helped feed much of the population, which in turn led to a reduction in food availability. As food scarcity exploded and the animals on which countless tribes had built their wealth were culled to keep themselves from dying of starvation, unrest began to emerge. With pastoralist tribes suddenly losing their livelihood, they were forced to turn to urban migration or banditry.

Kenya would be the focus of much of this strife, while the towns and cities of the coast, Nairobi region and Great Lakes region saw a massive influx of migrants. Nairobi could not handle this sudden influx, and soon saw massive food shortages and enormous population swings as mass die-offs were offset by new arrivals, while in the Great Lakes, the locals greeted the pastoralist newcomers with intense hostility, soon escalating to open violence. The coastal region, where food was more easily obtained, remained relatively peaceful but the interior was collapsing rapidly into chaos. As matters surrounding the Two Rivers Crisis and the South Mesopotamian Famine came under control over the first five months of 1933, the British were swift to rush the troops previously mobilised against the Ottomans south to East Africa to aid in pacification and famine relief efforts.

During this time, the situation along the Great Lakes was turning from bad to worse, with what amounted to open war breaking out between the incoming pastoralists and their sedentary neighbours for control of local food resources, the region having been amongst those least reliant upon American produce due to the fertility of the region. The denuding of the western Kenya soon reached the point of desperation, with tens of thousands dying of sickness, starvation or violence as social structures began to collapse in on themselves. White Settler colonies, mines and plantations soon became targets of roving bandits, with the settlers fortifying their settlements with rifles and on rare occasions machineguns. Looted mass graves and instances of cannibalism were discovered in the slums of Nairobi by horrified British officials, who had to fight their way back out of the slums to safety in the British Quarters, which had itself been rapidly fortified and protected by British soldiery.

When the British forces from Mesopotamia arrived, they found themselves inducted into the British Pacification Army in Kenya, commanded by Major General Sir Edward Northey, who was also named as Military Governor-General of Kenya, a man of noted racist tendencies and open brutality, Northey had nevertheless made a name for himself during the Great War and its aftermath before spending the last decade as administrator of Zanzibar, where he had been unable to make too much trouble. His appointment, occurring during the tumultuous political circumstances following the Two Rivers Crisis in Britain, was decided by the colonial office without much input from the distracted government and was to shape the response on a fundamental level. Northey came in with the sole goal of restoring order, cost what it may, and in doing so utterly obliterated any strictures, cultural, legal or social, which stood in his way. After settling the coastal region over the course of the remainder of 1933, Northey advanced into the hellish central and western parts of Kenya, putting down any opposition to his advance with force and placing the pastoralist population into massive camps where they could be fed more easily with imported produce from India. This would lead to the dissolution of many tribal bonds, as little attention was given to ethnic, cultural or religious divides amongst the interned, and a great deal of suffering as the starved internees were put to forced labor to help rebuild the colony.

By the middle of 1934 the worst of the unrest had largely been quelled outside of the Great Lakes Region, which took another half a year to pacify, with tens of thousands killed in the brutal process. Northey relied heavily on White Settler outposts to help administer the reconstruction of the colony, doling out internees to various settlements for aid in their work. This mass usage of forced labor for everything from plantation and mine work to the building of railways and the establishment of villages for the pastoralists - who were now forced into sedentary life by the colonial administration, eventually drew protest in London, with Northey and his horrific regime finally brought to an end in 1935. However, by then the damage had been done. Tribes, ethnic groups, religious groups and linguistic groupings had been torn apart and hammered together with little regard for such differences, with even families torn from each other and settled at seeming random, often across the country from each other. Pastoralist life was greatly weakened, with the majority eventually making their way north or south to the neighboring German colonies while an implacable hatred had been sown between the original sedentary population of the Great Lakes and the former pastoralists who had fled to the region in search of safety from the cataclysm only to be met by fire and blood (5).

South Africa had always been amongst the most troubled of the dominion relations within the British Empire, from powerful and influential native peoples such as the Zulu and Xhosa, to the ever rebellious Dutch-descended Afrikaner population and complicated racial structures, but these troubles would pale in comparison to the horrors of the South African Famine. There were three major factors which played into the defeat of Jan Smuts' liberal South African Party in the 1924 elections, his harsh suppression of the Rand Rebellion by White miners, his failure to secure the incorporation of South Rhodesia to South Africa and his lukewarm support for a more independent path for South Africa. This allowed for the ascendancy of the conservative National Party in coalition with the Labour Party, which had turned on Smut's South African Party over the handling of the Rand Rebellion. Together these two parties set about creating the foundations of an Afrikaner welfare state through a wide range of social and economic measures aimed at unifying Afrikaner support behind the government.

In 1928 the Labour Party entered into a period of considerable crisis as Walter Madeley, a prominent left-wing Labour MP and Minister of Posts, Telegraphs and Public Works, called for the recognition of the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union, which had non-white members. This greatly angered the National Party leadership, the recent Fall of Siberia greatly increasing anti-Communist sentiment on the right, and led them to demand that Madeley resign. This led to a major internal conflict in the Labour Party, which culminated in Madeley being removed from his post at the direction of the party leader, Frederic Creswell, in the process firmly aligning the Labour Party behind a policy of White nationalism while drawing the party closer to the National Party in the process. However, this effort was to meet with considerable opposition from within the Labour Party, even as Walter Madeley continued to protest this course of events. Greatly angered by these developments, Madeley would reach out to the Communist Party of South Africa to declare his membership, becoming their first Member of Parliament in the process. Many of Madeley's supporters would follow suit, joining the CPSA as well. The sudden emergence of the CPSA as a political force came as a great shock to the rest of the political parties, who were further scandalised when the CPSA recognised the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union, as well as a range of other multi-race trade unions, and opened up the party to non-White South Africans as part of a general policy of "Africanising" the party.

The 1929 elections were to see the return of the South African Party to government under Jan Smuts, as the National Party's coalition partners, the Labour Party, saw a precipitous collapse in support. During these middle years, the National Party government had opened up the economy to American imports, particularly of produce, as not only a cheap solution to feeding their rapidly expanding population, but also as a way of opening up a path for South African participation in the world economy outside of British influence. In general, South Africa experienced a period of incredible growth during the 1920s, which was further spurred on by the weakening of tariff barriers which allowed trade between South Africa and the United States to expand massively during the latter half of the 1920s, with the incredible wealth dug out of the ground helping to fuel the luxurious lifestyles of the New York and Washington elite. The newly elected South African Party would seek to further encourage these developments by removing much of what they viewed as excess governmental assistance, particularly for the agricultural sector where policies like high import taxes on all butter sales, preferential railway tariffs for famers and low-interest loans from the Land Bank all served to protect farmers against international competition while greatly increasing the cost of living for the average Afrikaner. The result was a further strengthening of industry and resource extraction companies at the cost of the farming population and an associated drastic lowering of the cost of living, which proved quite popular in urban areas. While the rise of the CPSA did cause considerable tensions, peace was maintained for the first few years of the new decade (6).

Ultimately, the horrors of the South African Crisis would have less to do with the actual food supply which, while significantly impacted, never quite reached the devastating levels experienced in East Africa. Instead, it would be social, cultural and racial divisions which caused the greatest strife in the region. The heart of the crisis would lay in the Transvaal, where racial tensions between Whites and Blacks were worst and the mining industry was at its most expansive. South Africa was amongst the last of the regions in Africa to begin relying on large amongst of American produce, with the majority going to the coastal cities and to the great mining settlements of the Transvaal while the remainder of the dominion was largely unimpacted. Thus, the first place struck by food shortages were the Transvaal's mining settlements, which were able to alleviate much of the immediate stress in 1931 and 1932 by switching to purchasing local agricultural produce. However, this resulted in the spiking of food prices, which disproportionately impacted the black miners of the Transvaal who were payed significantly worse than their white counterparts.

As the food supply worsened, while the quality worsened and the price rose dramatically, discontent began to make itself known. This was further amplified by the presence of recently trained CPSA agitators, crying out for the miners to lay down their picks and shovels in strike until proper food could be supplied - the number of miners collapsing from a lack of energy, with some even dying, having increased with worrying rapidity since 1930. By early 1933, as the height of summer struck and the mines turned into little better than furnaces, the number of dying miners rose to the dozens in individual mines with considerable worries that more would follow before the end of summer. Finally, on the 16th of January, the black miners had had enough, beginning work stoppages which soon spread to engulf the entire mining sector and threatened to draw sympathy strikes in many other, equally troubled sectors. The Second Rand Rebellion was now under way.

While negotiations were initially considered, the fact that the vast majority of the strikers were black led the government to press for the squashing of the rebellion without much more thought given to the matter. However, the Rand was not only manned by black miners, there was a considerable population of white miners in the region who felt that their black fellow miners had stolen their work and had displaced their white colleagues from numerous lucrative mines. Largely members of the Labour Party, these white miners saw in the Second Rand Rebellion a chance to reclaim their dominance of the Rand mines. Thus, when government forces began to move on the demonstrators, they found their efforts assisted by angry white miners with little interest in allowing the black miners back to work. The result was a bloodbath, as the predominantly white soldiers mostly sat back and allowed armed white miners to do their work for them. Protesters were shot out of hand, quickly spilling over onto anyone black in proximity of a mine before spreading to the nearby townships, with bloodshed escalating rapidly. However, the black miners were not to take this lying down, and before long the black and white miners were butchering each other with astonishing brutality with the army largely sitting on the sidelines perplexed and uncertain about how to resolve the situation.

This escalation in violence soon drew in local tribes from whom many of the black miners had originally come. It was at this point that the army began to act, attacking tribes as they began to cause trouble, driving them back into the Veldt. It was at this point that the crisis truly began to spin out of control, with the claimant King of the Zulu Kingdom, Solomon kaDinuzulu, speaking out against the violence, urging black South Africans to resist oppression. While officially only one chieftain amongst many in Zulu country, Solomon was widely acknowledged amongst the Zulu themselves, and his call to arms was answered by them in their tens of thousands. Attacks on white settlers and settlements exploded over the first couple months of 1933 while Afrikaners in the Transvaal turned back to their roots as commandoes, forming local defence forces and commando units with which to suppress the riotous black populace.

Bloodshed escalated rapidly, leaving the administration in Cape Town scrambling to find a solution to the crisis. Jan Smuts replaced the commanders of the military forces in the Transvaal, in hopes of securing more effective action, but the fact that both the Afrikaner and Black population was proving increasingly hostile to government forces caused major headaches in government circles. The conflict even threatened to tear the National Party apart, as the majority of the party rallied around the former Prime Minister J.B.M. Hertzog to support the government effort and call for an end to the violence amongst the Afrikaners, while the much more radical church minister and MP Daniel F. Malan called on the government to aid the Afrikaner populace in protecting themselves from rapacious black attackers and threatened to break with the National Party if they should fail to support their brethren in the Transvaal, in effect paralyzing the party.

The violence and anarchy spread throughout 1933 and soon began to reverberate across South Africa, with the Cape Colony in particular struck by sudden resource shortages as a result of the Transvaal mines shuddering to a halt. This led to mass layoffs and rapid increases in unemployment, which in turn drew great condemnation and anger, threatening to turn into open protests. However, beginning in 1934 with the arrival of considerable British aid, the situation was stabilised in the Cape Colony, which in turn allowed the government to finally begin restoring order in the Free State and Transvaal over the course of the following two years.

In the aftermath of the crisis, renewed elections would see the return of the National Party, this time as sole ruling party and on a significantly more rabidly segregationist platform. The most troublesome tribes in the east, most prominently several of the larger Zulu and Xhosa-speaking tribes, were to be split up and moved to South-West Africa, where they were mixed together and settled into small villages in an effort to gradually break up the tribal and ethnic identities of these troublesome tribes. At the same time a comprehensive new series of racial segregation laws were passed and strict controls on the remaining tribes were put into place while a series of anti-labour laws were passed by the horrified parliament which saw the right to strike, the formation of independent unions and much else largely restricted. The fact that the South African Party had been forced to turn to the British for aid was to leave a major stain on the party which ultimately led to its dissolution in 1937, while Jan Smuts retreated from politics, spending most of his time writing about his experiences, researching and writing a comprehensive history of South Africa and serving as advisor to various political protégés (7).

Footnotes:

(4) We start out with a bit of a repeat of some of the stuff previously mentioned in regards to British Africa before examining the regions where the African Famine had the least impact, namely West Africa and Sudan. It is important to make a note of the fact that West Africa has the largest portion of subsistence farmers, and is the most fertile of all these areas, and as such is able to find alternate food sources relatively easily. The weight of the crisis also very much impacts the relatively small urban populace, primarily in the Niger River Delta, and as such is much more contained than elsewhere. Even then, we still see nearly 10,000 deaths before the situation is brought under control.

(5) I do apologize for how grim all of this ended up getting, but I felt that it would be fascinating to see the sorts of unintended consequences something like a careless trade agreement can have. Famines were relatively rare in Africa for much of the 20th century, but I feel that the circumstances line up enough for it to remain a plausible direction for events to go. Cameron probably comes off worse than he deserves, considering he IOTL as Governor of Tanganyika largely championed a more inclusive approach, even if he is noted as having been a major critic of Byatt's openness towards the local population IOTL. Here he remains a staunch opponent to Byatt's policies, but given that Kenya/East Africa has a greater British settler population than Tanganyika I could see him relying more heavily on the settlers for support. Northey is an OTL racist asshole who IOTL tried to coerce African labor to work on European-owned farms and estates even after the Colonial Office had rejected such a plan, with him eventually getting dismissed for going through with it. Here he is basically given free rein to restore order to East Africa - with horrific consequences.

(6) I ended up needing to do quite a bit of background to prepare for the crisis that follows, but I hope that people find these divergences interesting. The major change here is that instead of the Labour Party cracking in two between Madeley and Creswell, with Labour on Madeley's side, here Creswell is able to secure stronger backing from the party to remove Madeley from his position. This is a result of the changes to the Communist movement, which, as elsewhere, is a lot more inclusive than IOTL and as such is an easier destination for Madeley to depart for than it was IOTL. The CPSA entering onto an "Africanising" path is also OTL and was adopted as policy in the late 1920s. This loss of support on the part of Labour, beyond strengthening the Communists, also has the important role of boosting the South African Party back into leadership - preventing the OTL total dominance exhibited by the National Party until World War Two. This also means a change in policy with the new government, which decides to pursue a decidedly less interventionist policy and most importantly greatly deprioritizes that farming sector in favor of business and industry. It is worth noting here that the South African Party draws most of its support from the urban populace, particularly the business elites, and of the various major parties in South Africa is the most willing to work with the British. The National Party by contrast is right-wing and strongly tied to both Afrikaner Nationalism - although lacking the inherent distrust of the left-wing exhibited by most right-wing parties of the time. The National Party-Labour alliance is actually all OTL.

(7) And we are done with the nightmare. This was not particularly pleasant to write about, but I do think that it is fascinating to consider what an even more antagonistic set of race relations in South Africa would have looked like, particularly in the first half of the century. This is before Apartheid was instituted as government policy and in a time when South Africa was coming into its own, developing its national identity. The South African Crisis of the 1930s shakes all of that up and allows me to explore this part of the world. IOTL, this period is something of a golden period from what I have been able to read up on it where things seemed relatively under control, economic prosperity grew and firm social structures began to develop even as South African national culture was emerging after the Boer Wars. By contrast, ITTL the period will be known as a defining national crisis which reshaped the political, social and economic spectrum on a fundamental level. I will finish off by mentioning that King Solomon of the Zulu ends up being amongst those dispatched to South-West Africa in exile.

Jean Price-Mars, President of Haiti

A Cruise Through The Caribbean

The two troubled nations of Hispaniola, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, had both come under American occupation soon after the start of the Great War, Haiti in 1914 and the Dominican Republic in 1915. While the Dominican occupation had primarily been triggered by American exasperation with the tumultuous political situation in the country, in Haiti the presence of a small but powerful German minority and their potential role in creating a German-aligned base in the Caribbean had played into decision-making as much as the ongoing political turmoil. The occupations were wildly unpopular with broad swathes of the populace in not only the two occupied nations, but within the United States itself, where many questioned the need for the intervention and the considerable costs it brought with it.

From the start, the occupations were fiercely resisted with the gavilleros in the Dominican Republic and cacos of Haiti each causing considerable trouble. While in the Dominican Republic this resistance would continue to trouble the occupiers, with constant attacks and anger from the population, in Haiti resistance was crushed with shocking violence in two "Caco Wars" which combined saw several thousand dead. The American treatment of the two states also differed considerably, with the Americans far more open to cooperating with the local Dominicans, whose racial mixture was far more varied than the almost exclusively African-descended population of Haiti, with the result that even President Wood, otherwise a pretty stalwart supporter of American efforts abroad, was convinced of ending the occupation of the Dominican Republic with speed. This process, which saw the effective occupation ended in 1921, would culminate in the 1924 election of the pro-American Horacio Vásquez Lajara.

Matters in Haiti, by contrast, were to prove considerably more troubled. In 1915 the US Senate had ratified the Haitian-American Convention which granted the United States security and economic oversight of Haiti for the next decade while giving American Representatives veto-power over all governmental decisions and appointing Marine Corps commanders to serve as administrators of Haitian government departments, although local institutions remained under Haitian rule. This allowed the American occupiers to re-institute a system of corvée labor, forced civil conscription in which Haitian civilians were captured and forced to work on the numerous public infrastructure projects begun by the American occupation.

The end of the Great War was to introduce a much welcomed international dimension to the occupation, as the German Empire began to lodge protests with the American government for their actions taken against the German minority population of Haiti, specifically the confiscation of their businesses, which at the time of the occupation had been responsible for 80% of Haiti's international trade.

Thus, with international lines of communications opening up once more and the protests of the German Haitians streaming in to the Foreign Ministry, German diplomats began to exert pressure on the Marshall, and later Wood and McAdoo presidencies for the ending of their occupation, a restoration of the plundered wealth of the German Haitians and various other matters. While President Wood remained forceful in his opposition to any such suggestions about ending the occupation of Haiti, the same could not be said of the incumbent President McAdoo, who had come into office on a promise of ending foreign entanglements such as Haiti. The result was that when the 1915 Haitian-American Convention came up for renewal in 1925, President McAdoo campaigned against its re-ratification, ultimately allowing it to lapse, returning authority to the American-selected President Louis Borno. At the same time the Americans payed out a cash settlement to the German Haitians which, while far less than the worth of their confiscated businesses, allowed them to reestablish themselves as part of the Port-au-Prince elite, a status further solidified by the arrival of more German businessmen eager to make inroads into the recently independent state.

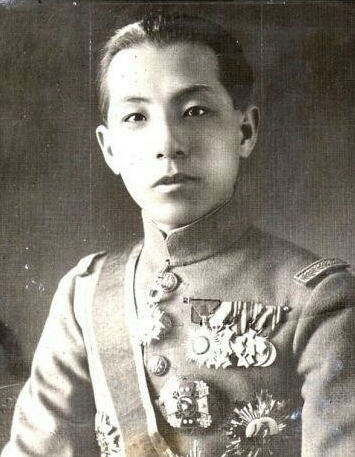

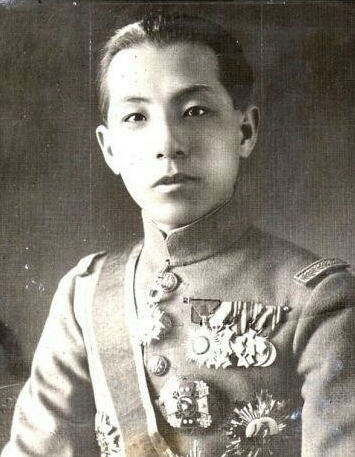

Independence brought with it an end to the hated Corvée labor and a reopening of Haiti to the world market, with the various European countries soon streaming in to make their presence known. However, the American occupation had allowed them to take control of the largest share of the pie, dominating more than 90% of all international trade out of the island nation and granting them important supporters in all major government departments. Fears of another American invasion played havoc with the Haitian populace which in 1928 saw the election of a fiercely anti-foreigner candidate in the form of the immensely popular Jean Price-Mars (8).

A doctor, teacher, diplomat, writer and ethnographer, Jean Price-Mars was deeply impacted by the occupation and was inspired by the constant active resistance of Haiti's peasants. Over time he had come to embrace the African roots of Haitian society as a part of the wider Négritude movement by championing the practice of Vodou as a full religion. He argued against the prevailing prejudices and ideologies of the Haitian elites, which favored European cultures from the colonial period while rejecting all non-white, non-western elements of their culture. In the process Price-Mars had begun to formulate a form of African-Haitian Nationalism which identified the Haitian cultural identity with the African struggle against slavery, harkening back to the island's proud stand against the French in their bloody revolution, while denigrating the mostly mixed-race elites for their inability to promote the welfare of the wider Haitian populace.

Price-Mars' rise to power came on the backs of the firmly black peasantry and a segment of the mixed-elite who had come to embrace Price-Mars' and other Negritude writers' belief in the African nature of Haiti. Price-Mars aimed to reorient Haitian society away from the long-dominant mixed-race elites of Port-au-Prince and towards the more firmly black working and peasant class. As a result he began passing a series of major legislative proposals which would work towards redistributing wealth within Haiti while exploiting the intense infrastructure construction conducted under the occupation to help tie the country closer together. He had Vodou recognized as a religion on equal footing with the Catholic Church, to the utter horror of the Port-au-Prince elite, and sought to favour the German Haitian minority as the government's window to the outside world, in the process hoping to create a second pole of foreign influence to play off against the Americans. By 1930, Price-Mars found himself so intensely unpopular with the mixed-race elite and his fears of assassination so great that he chose to move government operations to the town of Ganthier some thirty kilometres east of Port-au-Prince, where his supporters greatly outnumbered his detractors.

During this period the Dominican Republic had remained relatively peaceful under the leadership of Lajara, however in 1930 he set out to secure a second term of office and was soon betrayed by his own Chief of Police Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina who, in coordination with a rebel leader by the name of Rafael Estrella Urena launched a coup which saw Urena appointed acting president and Trujillo as head of police and the army. As per the agreement between Urena and Trujillo, the latter became the presidential nominee of their newly formed party with Urena as his running mate. However, in order to secure victory, Trujillo unleashed the army on his opponents, forcing them to withdraw from the race, and in May of 1930 was elected as President of the Dominican Republic virtually unopposed. The ascension of Trujillo and Price-Mars laid the seeds for a growing confrontation between the two states of Hispaniola.

During the initial period of government under Trujillo, he was able to significantly strengthen his grip on power, rebuilding the Dominican capital after it was devastated by the Hurricane San Zenon bare weeks after his ascension, while renaming the capital after himself. In 1931 Trujillo made the Dominican Party, of which he was head, the nation's sole legal party and forced government employees to "donate" ten percent of their salaries to the national treasury. He murdered opponents of his government and allowed for the arrest of people caught without a party membership card. Finally, in 1934 Trujillo had himself promoted to Generalissimo of the army and secured re-election as the sole candidate on the ballot while seeking to build up a cult of personality. It was during this time that Trujillo truly began his campaign of Antihaitianismo which was effectively a brand of anti-Black discrimination targeting the Haitian minority in the Dominican Republic and the Afro-Dominican citizenry, while the government heavily favored white migrants and refugees, soon becoming a favoured destination amongst White Russians, Serbians and Ukrainian Jews, who proved eager to help build up the republic.

In Haiti, the mixed-race elites of Port-au-Prince finally made their move in late 1931 when a contingent of soldiers trained by the Americans and headed by mixed-race officers launched an attack on Ganthier, gunning down any who stood in their way as they sought to capture the Haitian president. However, Price-Mars had been expecting something like this for a while and had plenty of caco fighters at the ready, who soon swarmed the relatively small attacking force and butchered them to the last man. Price-Mars now turned to Port-au-Prince, mustering a massive if rag-tag force of cacos who descended on Port-au-Prince with the aim of purging the city of traitors. Ultimately, a significant portion of the mixed-race elites would find themselves forced to flee into the reluctantly welcoming embrace of the Americans. Debate over whether to take actions to reinstitute the occupation were brought up in the US Senate, but floundered in the face of bitter partisanship and disinterest in the issue.

Thus, the nation fell fully into Price-Mars' hands with his government now further enriched by the confiscation of the considerable fortunes of the exiled elites. Over the following years, Price-Mars would continue in his efforts to develop an authentic Black Haitian nation state, railing against the Americans and Dominicans for the most part, while quietly developing ever strengthening ties to the Germans, who he viewed as sufficiently distant and disinterested in Haitian affairs to merit cooperation with. During this time, Price-Mars drew close with Jacques Roumain, one of the many mixed-race elite who had turned his back on his wealthy background, although in Roumain's case he had turned to communism. Price-Mars, while distrustful of foreign, European, ideas found much of interest in communist writings and soon began to adopt elements thereof - particularly building on the village-based communal structures developed by the Muscovite Communists. While never particularly clear about his particular political affiliations, Price-Mars would gradually come to adopt more and more of the ideas espoused by Roumain, who rose to become Price-Mars' vice-president following his victory in the 1933 elections. Notably, Price-Mars would spend much of his time in the city of Cap-Haitien, preferring it over the mixed-race dominated Port-au-Prince. Finally, in 1937 the tensions between Haiti and the Dominican Republic began to boil over when Trujillo dispatched orders to the Dominican military to clear out the Haitians in Dominican lands with violence (9).

Cuba had been a nation inextricably tied to the United States since its War of Independence at the dawn of the century. Since then the country had gone through two separate periods of occupation by the Americans, considerable political turmoil and, in 1917, and a brief civil war between Liberal and Conservative Parties triggered when the Conservatives were faced with defeat in the 1916 elections to the Liberals. This conflict, which initially seemed to be playing out entirely in Liberal favour after the initial Conservative coup attempt failed, was forced to a close by the Americans under threat of armed intervention, with the Americans restoring the Conservative Garcia Menocal to government despite his electoral losses due to suspected pro-German sympathies in Liberal ranks.

Despite this turmoil, Cuba came out of the Great War Period in relatively good standing, as artificially boosted sugar prices brought about by sugar scarcity allowed for considerable economic growth in Cuba. However, the moment that the war came to an end and international trade rebounded, the price of sugar cratered. Cuba's economy was build almost entirely on the sugar industry, and as such this sudden collapse in prices was to send the country into bankruptcy by the time of the 1920 elections. This time it was a major Liberal figure of the 1917 civil war, Alfredo Zayas, who took power. Zayas spent his four years in power on advancing women's rights, including securing them the right to vote, and conducting reforms in the fields of education and social security, allowed freedom of the press without censorship, secured the return of the Islas de Pinos, which had been occupied by the United States since 1898, and obtained a loan of fifty million US Dollars from J.P. Morgan with the aim of relaunching the devastated economy he had inherited.

However, Zayas and his government would find themselves dogged by charges of corruption, up to and including the President himself. Since 1913, when Zayas had ceased to be Vice President of the Republic, he had designated himself as an official historian of Cuba with the decadent salary of 500 pesos a month, while during his tenure, he won first prize in the National Lottery twice. He gave free play to other vices, engaging himself in the smuggling of alcohol to Prohibition-Era America while maintaining a web of influence in all government offices. By the end of his term, Zayas' personal fortune had grown to several million pesos, making him amongst the richest men on the island. By 1923, many of the island's intellectuals had seen enough and published a public letter of protest, which came to be known as the Protest of the Thirteen - which ultimately sank Zayas' chances at a second term. Instead, Zayas turned to his comrade-in-arms from the 1917 crisis and ally in government, Gerardo Machado, to succeed him.

In the following 1924 elections Machado was able to emerge victorious, defeating Zayas' old rival Menocal in the process. It is worth noting at this point that beginning in 1923 the price of sugar began to rally, allowing the Cuban economy to slowly gather steam once more, fueled both by the increasing sugar prices and the loan Zayas had secured from J.P. Morgan. Machado would prove himself a considerably more popular figure than Zayas or Menocal, coming to power on the notion of turning Cuba into the "Switzerland of the Americas". The new government tried to reconcile the interests of the different sectors of the national bourgeoisie and the American capital in its economic program, offering guarantees of stability to the middle classes and new jobs to the lower classes. Its economic program focused on the reduction of investments, a policy of reducing the sugar harvest to stimulate depressed sugar prices in the world market, and a tariff reform which raised the price on foreign products that could be produced in Cuba.

The increase in sugar prices brought with it an increase in foreign, particularly American, investments which allowed the Machado government to embark on an ambitious pubic works program which saw the construction of the Central Highway of Cuba, which was to run across practically the entire island from east to west, saw the construction of El Capitolio, the new home of the Cuban Congress, and the expansion of the University of Havana to mention but a few of the numerous building projects undertaken under Machado.

However, while Machado had pledged to not seek a second term, which was prohibited by the 1901 Constitution, this state of affairs did not last for long, and by 1927 Machado was pushing through a series of constitutional amendments which would allow him to seek re-election, allowing him to secure a second term in the 1928 elections. However, Machado's growing shift towards authoritarianism was met with bitter resistance, most prominently by the University Student Directory of the University of Havana, which had formed in 1927 in response to his constitutional changes. The following years saw numerous protests led by the Student Directory and the assassination of several student leader by Machadista gun-men while others were driven into exile, with the University of Havana itself being shut down temporarily in 1930 to quell the resistance. While the student leaders sought to whip up outrage at the government's treatment, they were largely met with shocking indifference if not hostility, as many of their elders came to believe that the riotous students posed a threat to the continued prosperity of the island.

By 1931 it had become clear that Machado had succeeded in his goals of securing power while pacifying the country through economic prosperity. In 1932 Machado negotiated an end to the bitterly hated Platt Amendment which had allowed constant American interference in Cuban affairs while continuing to strengthen his hold on power. He would secure re-election once again in 1933, at which point he began a more extensive adoption of Portuguese Integralist principles, with the aim of securing his position at the head of the Cuban nation for years to come (10).

The Post-Great War period was to prove a time of considerable development and change for the African-descended population of the Americas, connecting together a web of black ideologues from Harlem and New Orleans to Le Cap, Kingston and Paris itself. At the heart of these developments lay Harlem, on the isle of Manhattan in New York. The Harlem Renaissance and subsequent movements grew out of the changes that had taken place in the African-American community since the abolition of slavery, most notably the mass migration of African Americans out of the south, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan as a major force in American society and the need for African Americans to shape an understanding of their role in society, as Americans, as Africans and as African Americans.

Playwriters, authors, preachers, musicians and artists of all sorts contributed to a feverish cultural ferment in which the racist stereotypes which pervaded much of society were challenged by works of art, music and literature emphasising Pan-African pride and capability. The migration of southern Blacks to the north had changed the image of the African American from rural, undereducated peasant to one of urban, cosmopolitan sophistication. This new identity led to a greater social consciousness, as African Americans became players on the world stage, expanding intellectual and social contacts internationally. The progress, both symbolic and real, during this period became a point of reference from which the African-American community gained a spirit of self-determination that provided a growing sense of both Black urbanity and Black militancy. The urban setting of rapidly developing Harlem provided a venue for African Americans of all backgrounds to appreciate the variety of Black life and culture. Through this expression, the Harlem Renaissance encouraged the new appreciation of folk roots and culture. For instance, folk materials and spirituals provided a rich source for the artistic and intellectual imagination, which freed Blacks from the establishment of past conditions. Through sharing in these cultural experiences, a consciousness sprung forth in the form of a united racial identity (11).

While originating in Harlem, it was not long before black students and scholars from across the world began to flock to Harlem in search of help in developing their own intellectual traditions. One such tradition would prove to be the Négritude movement, which was initially assembled in Paris but soon developed a second heart in the Haitian city of Le Cap, which gradually took on increasingly Communist and militantly African nationalist elements and fell under the sway of Jean Price-Mars. Another intellectual tradition came in the form of the New Orléans Renaissance, a development spurred on by Huey Long's willingness to defend the black and mixed population of Louisiana against discrimination. Here, in the swamps of the Mississippi Delta, a distinct cultural movement came under way, far less willing to adopt the dress and manners of northern whites, as they accused the Harlem Renaissance of doing, and rather more closely connected to the Caribbean movements out of Jamaica and Haiti. While willing to cooperate and participate in American society and culture, the New Orléanisan movement drew a sharp line between themselves and their white neighbours, holding that while segregation was harmful to the development of the African spirit due to the inherent inequalities it fostered, it was necessary that Black America be allowed to develop on an independent path from that of White America.

These concurrent cultural and social movements would take on a variety of different tacks and adopt an often confusing profusion of positions on various issues, with each movement split amongst itself in turn as well. The Harlem movement borrowed much from the White Progressive movement of the time, most advocating for integration and the breaking down of segregationist barriers, viewing themselves as American citizens who wished to remain part of the United States. At the opposite end of the spectrum lay the Le Cap Négritude movement, which was fiercely black nationalist in outlook, rejecting any idea of living alongside Whites, and ever searching for ways in which to grow closer to the African Spirit, be it through Vodou, Jazz or pilgrimages to Africa.

Between these two poles lay the other movements : The Garveyites of Jamaica, the New Orléanians and Parisian Négritudes most prominently, of which the first would prove itself most significant. The Garveyites were adherents of the Jamaican thinker Marcus Garvey, who had initially risen to fame and prominence as part of the Harlem movement, where he established the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, the UNIA. Garvey emphasized the unity between Africans and the African diaspora, campaigning widely against European colonial rule in Africa and promoting the political unification of the continent. However, he soon found himself in trouble with the mainstream Harlem movement as his plans for Africa after liberation fell increasingly into Integralist lines of thought, envisioning a united Africa under a one-party state rule in which he would govern as President of Africa.

In sharp contrast to mainstream Harlemites he doubled down on segregation, believing that a liberated Africa would need to enact laws to ensure Black racial purity, and committing firmly to the Back-to-Africa movement, arguing that African-Americans should migrate either to Africa or to Black-dominated states like Jamaica or Haiti rather than remain in a White-dominated America. However, Garvey soon fell from grace in Harlem, when he was convicted of fraud under dubious circumstances and imprisoned in Atlanta from 1923-25, before being deported to Jamaica in 1927. In Jamaica Garvey worked to rebuild his following, developing a chapter of the UNIA and founding the first Jamaican political party in the form of the People's Political Party in 1929. Garvey would meet on several occasions with President Jean Price-Mars of Haiti, cooperating with him and the Le Cap Négritudes to support the development of black-led nations and championing independence for Jamaica, although by the early 1930s the two men would fall out over their diverging political alignments.

During the first half of the 1930s, the Back-to-Africa movement experienced considerable ideological turmoil as the collapse of the greatly admired state of Ethiopia into civil war and eventual client status to Germany shook belief in Ethiopianism to its core. Many thinkers were to interpret this development as evidence of the loss of God's favor and the need for a spiritual and moral rebirth before Africa could be reclaimed from the imperialist powers. It was during this time that Gugsa Welle, the Last African Lion as he would be known, became the subject of deification and cult worship - portrayed as a martyr for the cause of a Free Africa. This was set side by side with the development of a functioning black-ruled state in Haiti, and saw Jean Price-Mars elevated to a status similar to that of Gugsa Welle in some circles. Despite the hardships and differences experienced within and between the various Black movements of the time, the 1920s and 30s were a time of great cultural and social development for the African-descended population of the Caribbean and America (12).

Footnotes:

(8) For the most part this is all OTL up until the 1920s where the Post-War divergences begin to play into events. Events in the Dominican Republic largely proceed as per OTL, although there are some minor divergences in the timing of events. It is in Haiti where we see the larger divergence. IOTL it would take until 1934 for Haiti to restore its independence, during which time the country continued to utilise corvée labor. Here, the continued presence of Germany as an international power really comes into play, with the small German merchant population in Port-au-Prince playing a key role in drumming up the German Foreign Ministry to press the Americans on Haitian affairs. This pressure, combined with the fact that the occupation was never particularly popular in the United States to begin with, ultimately result in the occupation coming to an end significantly earlier. At the same time we see the growth of anti-foreign, particularly anti-American, sentiment in the aftermath of the occupation and eventually an earlier rise of the black working class of Haiti significantly earlier than IOTL.

(9) To be honest, basically everything mentioned in the Dominican sections of this update are OTL, except for the fact that without the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany Trujillo is forced to rely on other groups of white settlers to help build up the white population of his side of the island. I cut off just before the OTL Parsley Massacre because that is when things are really going to begin going off the rails of OTL, something I will be saving for a different update.

The developments in Haiti by contrast are of a significantly different tune than OTL. Price-Mars has elements of the OTL Duvalier dynasty's emphasis on black Haitian culture, but lacks their bloody-fisted tyrannical personality or approach. He is more of a scholarly ideologue than anything, who has succeeded in hitting on a particularly powerful brand of black nationalism, which he uses as a cudgel against the mixed-race elites, and finds the whole idea of dictatorial rule rather sordid. He maintains what proves to be a semi-functioning democracy, even if his governing party retains a super-dominant position after kicking out the former ruling elite and implementing a series of democratic reforms which grant universal suffrage, and in the process make the Black peasant and working classes the single most powerful force in politics. Notably, he does not fall into the pitfalls of totalitarianism. In fact, Haiti, particularly the city of Le Cap (Cap-Haitien), becomes a centre point for the Négritude movement and various other Afro-American movements, as we will get into later in this section.