71. Oh, East is East, and West is West…

The concept of "Khalkha" appeared in Mongolia in the 15th-16th centuries and meant lands located north of the Gobi Desert. Khalkha was a territory divided into the possessions of many small Eastern Mongolian khanates that feuded with each other.

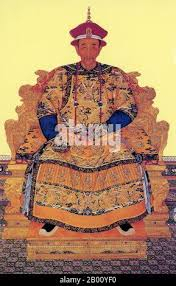

In the 1660s, a bloody internecine war broke out in Khalkh, as a result of which two warring groups were formed in the country. One of them was supported by the Dzungarian Khanate, the other was supported by the Manchu Qing Empire. As a result, in 1688, a war broke out between Dzungaria, led by Khan Galdan Boshogtu, and Khalha led by Tushetu Khan Chihundorj and the first Mongolian Bogdo-gegen Zanabazzar. At the same time, the ruler of Dzungaria aimed to unite the whole of Mongolia under his rule to confront the Qing armies. However, most of the Khalkha khans opposed Galdan Boschogt's unification plans, and when they were defeated in the armed struggle, they, not wanting to obey the Oirat khans, they turned to the Qing Emperor Kangxi to accept Khalhu into Manchu citizenship. In 1691, a ceremony was held near Lake Dolonnor to mark Khalhi's entry into the Qing Empire.

As a result, by the early 1700s Qing’s territorial interests grew comparing to those of the time of Nerchinsk. Of course, there were “theoretical” and practical interests.

“Theoretical” ones had been based upon the premise that everybody is a vassal of the Emperor of China and that all territories which at some point in the past really or allegedly had been populated by the Chinese are a direct part of the empire. By some (questionable) assessments, the Chinese delegation at the talks “demanded the entire south-east of Siberia, i.e. Tobolsk, all of Irtysh, Isset, Ilimsk, lakes and everything between them, on the grounds that they once lived there about 3-4 thousand years ago”.

Practical ones had been more modest, to get a clearly defined border between Russia and Khalkha territories, stop Mongolian emigration to the Russian territory and to prevent Russian help to the Dzungars.

Trade was not too high on Qing’s scale of interests and they tended to use it in OTL as a leverage against the Russian side, which was interested in it. IITL the Russian trade interest still exists but it is much more limited (basically, almost down to a single item, the tea, and even it is obtainable from other sources). The same goes for the military presence in the region: unlike OTL, Razuzinski does not have to take military measures (arming the local tribes, building a fort) to counter the Manchu military presence at the place where the talks had been conducted, just to balance it with some of the troops which are already there.

Strictly speaking, the 1st Chinese diplomatic mission to Russia had been sent by Kangxi Emperor in 1712 but it was sent not to Peter but to Ayuka Khan with an offer to join Qing in a fight against the Dzungars. The underlying logic was not quite clear because both Kalmyks and Dzungars were Oirat Mongols and did not have mutually-contradicting interests. On the top of this, Ayuka, with all his independent behavior, never was forgetting that he is Russian vassal and keeps getting quite tangible benefits from this status both for the Kalmyks in general and for himself personally (the Kalmyk troops participating in the BFW, which ended just 3 years prior, returned with a sizable loot and he himself got quite expensive gifts from Kremlin’s armory and presently the Russian government had been securing the line between the Kalmyks and the Kazakhs of the Little Juz). OTOH, the Chinese had been quite vague regarding the possible awards and, anyway, war against the Dzungars would be a difficult exercise with a need to ride across the hostile Kazakh territory. So Ayuka stuck to a safe “talk to my boss” position: Russia is neutral in that confrontation and he can’t act on his own in contradiction to this position.

Sending messengers directly to Ayuka was rather typical move of the Qing policy: they tried to ignore the existing political affiliations and implied that the Kalmyks of Volga are the direct vassals of China.

So in 1718 Kangxi Emperor sent a new missions to Moscow with the assurances of friendship and a request to allow the new talks Ayuka. After receiving the Russian escort, mission started from the border in January 1719 and arrived to Moscow in April.

The officials along the route received instructions to show the Russian military might so there were plenty of troops in a plain view and even few military parades “to honor” the distinguished guests. More of those and on a greater scale followed in Moscow before the audience and during the talks with Prince Dolgoruki and Shafirov. After the ambassadors acknowledged in writing that Qing government recognizes the Kalmyks of Volga as the Russian subjects, permission to send a new mission to the Kalmyks had been granted (and Ayuka warned about not listening) but this was seemingly it unless the ambassadors mentioned the Emperor’s wish to discuss the issue of the Russian-Chinese border. Arrangements for the meeting at the border in 1720 had been made.

Upon return of the embassy, a new direct embassy to the Kalmyks had been sent but it was not allowed to cross the border with the explanation that “the Kalmyks are the old subjects of His Imperial Majesty and without his direct order not only can’t receive the foreign ambassador but even made their own decisions.” [1] If earlier, the Chinese ambassadors had been allowed to talk to them, this was done exclusively out of respect and friendship to the Emperor of China. The Qing had to swallow this.

The border discussion had been trusted to the Sava Raguzinski-Vladislavich, a Serb from Raguza who was on the Russian diplomatic service since the early 1700s.

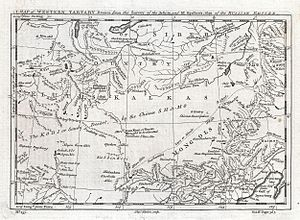

He composed a preliminary text of the treaty which had been approved by Kangxi Emperor except for the border part, which should be discussed at the border region. The place of the congress of commissioners was chosen by the river. Bura (Boro) south of Selenginsk, which was considered the border of Khalkha-Mongolia. Here the Qing side was represented by dignitaries Longotu, Ceren-wan, Tulishen.

Arriving in the border area, Ragizonski, wanting to obtain accurate information about the Kerulen and Tola rivers, along which he proposed to lead the border, sent there a reconnaissance party led by S. A. Kolychev. As a result of this trip, it turned out that the mentioned rivers are 15 days away from the last Russian guard on the Selengin road (Barsukovsky). During the move from Beijing to the area of demarcation S. L. Raguzinsky saw that the Qing authorities were strengthening in Mongolia, and a Manchu military detachment was located near the place of the congress of commissioners. That's why he forced the construction of the fort on the Chikoi River river and alerted a governor of Siberia who immediately sent a strong Russian detachment to the site. Manchu attempt to repeat the Nerchinsk scenario failed.

Qing representatives away from the capital did not become more compliant, although they slightly reduced the size of their claims. They now proposed to draw the border along the tributary of the Selenga River. Jide (Jide), and finish her Ujungar possessions, near the Subuktuy tract. At the same time, Manchu diplomatics were against the joint description and demarcation of the border, as insisted on by the Russian side. Once again, the conferences followed one after another, without bringing practical results.

The negotiations were especially hampered by dignitary Longotu, who categorically rejected all attempts to reach an agreement and influenced other Manchu representatives. In this regard, S. L. Raguzinsky decided to get Longota removed from the conference. Having held separate talks with the chief Qing representative of Tseren-wang on this occasion, the Russian envoy achieved success: Longotu was recalled to Beijing and demoted. The Manchus eventually realized that they did not have an overwhelming advantage of forces, and the decisive course of action of the Russian representative caused them concerns about Raguzinsky's demands to draw a border line along Kerulen and Tola. This prompted Tseren-van to offer Raguzinsky to establish a border on the existing line between the Russian and Khalkha borders at the time of negotiations - through the Mongolian guard posts. A complete demarcation of the border and setting the border marks on a ground took two more years and the work had been finalized in 1723 [2] in Kyakhta Treaty.

While ceding a small territory claiming by the Khalkha khans, Russia got a much greater territory and official Chinese recognition of the Russian possession of the lands to the South from Krasnoyarsk and Kuznetsk, previously controlled by the Khalkha. When it came to the final demarcation of the border the Manchu representatives “cheated themselves” due to the ignorance of a local geography : all research had been made by the Russian expedition while the Manchu simply relied upon the imprecise old maps composed by the Jesuits. The Russian-Chinese border was determined west of the Argun River to the Shabin-Dabat Pass (Western Sayan Mountains).

The final treaty established the duty free border trade in Kyakhta, diplomatic protocol, arrangements for the Russian caravans and the rules for dealing with the minor border violations.

Well, of course, except for the border definition, neither side was fully sincere. The Chinese kept considering Russia a Chinese vassal, kept making the petty offenses in the letters addressing and played the old games with the caravan while the Russian did not stick to the item of a treaty requiring return of the escapees [3].

Border by the lower Amur and a territory directly to the North of it, remained undefined, which allowed the Russians to start (later) establishing their de facto presence ignoring the Chinese assumption that this is their land [4].

______________

[1] In OTL “Her ….” because it happened during the reign of Anne.

[2] 1727

[3] Except that later they invited the Chinese officials to confirm that one of the rebel leaders who fled to Russia and died from the pox is really dead. 😪

[4] Which they did not bother to explore, let alone populate, until it was too late.

“Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet..” unless they have something of value to discuss… 😜

"As for the issue of borders, it caused very heated controversy. The Chinese commissioners, by the remarkable power of their imagination, believed that the whole country to and including the city of Tobolsk belonged to China, and insisted that the Count [Sava Vladislavić Raguzinski] sign a treatise defining the border of Angara.”

F. Martens

“Russia is a small vassal state”

Emperor Yin Zhen, 1727

«Geography is not a noble science»

An old Russian play

Background"As for the issue of borders, it caused very heated controversy. The Chinese commissioners, by the remarkable power of their imagination, believed that the whole country to and including the city of Tobolsk belonged to China, and insisted that the Count [Sava Vladislavić Raguzinski] sign a treatise defining the border of Angara.”

F. Martens

“Russia is a small vassal state”

Emperor Yin Zhen, 1727

«Geography is not a noble science»

An old Russian play

The concept of "Khalkha" appeared in Mongolia in the 15th-16th centuries and meant lands located north of the Gobi Desert. Khalkha was a territory divided into the possessions of many small Eastern Mongolian khanates that feuded with each other.

In the 1660s, a bloody internecine war broke out in Khalkh, as a result of which two warring groups were formed in the country. One of them was supported by the Dzungarian Khanate, the other was supported by the Manchu Qing Empire. As a result, in 1688, a war broke out between Dzungaria, led by Khan Galdan Boshogtu, and Khalha led by Tushetu Khan Chihundorj and the first Mongolian Bogdo-gegen Zanabazzar. At the same time, the ruler of Dzungaria aimed to unite the whole of Mongolia under his rule to confront the Qing armies. However, most of the Khalkha khans opposed Galdan Boschogt's unification plans, and when they were defeated in the armed struggle, they, not wanting to obey the Oirat khans, they turned to the Qing Emperor Kangxi to accept Khalhu into Manchu citizenship. In 1691, a ceremony was held near Lake Dolonnor to mark Khalhi's entry into the Qing Empire.

As a result, by the early 1700s Qing’s territorial interests grew comparing to those of the time of Nerchinsk. Of course, there were “theoretical” and practical interests.

“Theoretical” ones had been based upon the premise that everybody is a vassal of the Emperor of China and that all territories which at some point in the past really or allegedly had been populated by the Chinese are a direct part of the empire. By some (questionable) assessments, the Chinese delegation at the talks “demanded the entire south-east of Siberia, i.e. Tobolsk, all of Irtysh, Isset, Ilimsk, lakes and everything between them, on the grounds that they once lived there about 3-4 thousand years ago”.

Practical ones had been more modest, to get a clearly defined border between Russia and Khalkha territories, stop Mongolian emigration to the Russian territory and to prevent Russian help to the Dzungars.

Trade was not too high on Qing’s scale of interests and they tended to use it in OTL as a leverage against the Russian side, which was interested in it. IITL the Russian trade interest still exists but it is much more limited (basically, almost down to a single item, the tea, and even it is obtainable from other sources). The same goes for the military presence in the region: unlike OTL, Razuzinski does not have to take military measures (arming the local tribes, building a fort) to counter the Manchu military presence at the place where the talks had been conducted, just to balance it with some of the troops which are already there.

Strictly speaking, the 1st Chinese diplomatic mission to Russia had been sent by Kangxi Emperor in 1712 but it was sent not to Peter but to Ayuka Khan with an offer to join Qing in a fight against the Dzungars. The underlying logic was not quite clear because both Kalmyks and Dzungars were Oirat Mongols and did not have mutually-contradicting interests. On the top of this, Ayuka, with all his independent behavior, never was forgetting that he is Russian vassal and keeps getting quite tangible benefits from this status both for the Kalmyks in general and for himself personally (the Kalmyk troops participating in the BFW, which ended just 3 years prior, returned with a sizable loot and he himself got quite expensive gifts from Kremlin’s armory and presently the Russian government had been securing the line between the Kalmyks and the Kazakhs of the Little Juz). OTOH, the Chinese had been quite vague regarding the possible awards and, anyway, war against the Dzungars would be a difficult exercise with a need to ride across the hostile Kazakh territory. So Ayuka stuck to a safe “talk to my boss” position: Russia is neutral in that confrontation and he can’t act on his own in contradiction to this position.

Sending messengers directly to Ayuka was rather typical move of the Qing policy: they tried to ignore the existing political affiliations and implied that the Kalmyks of Volga are the direct vassals of China.

So in 1718 Kangxi Emperor sent a new missions to Moscow with the assurances of friendship and a request to allow the new talks Ayuka. After receiving the Russian escort, mission started from the border in January 1719 and arrived to Moscow in April.

The officials along the route received instructions to show the Russian military might so there were plenty of troops in a plain view and even few military parades “to honor” the distinguished guests. More of those and on a greater scale followed in Moscow before the audience and during the talks with Prince Dolgoruki and Shafirov. After the ambassadors acknowledged in writing that Qing government recognizes the Kalmyks of Volga as the Russian subjects, permission to send a new mission to the Kalmyks had been granted (and Ayuka warned about not listening) but this was seemingly it unless the ambassadors mentioned the Emperor’s wish to discuss the issue of the Russian-Chinese border. Arrangements for the meeting at the border in 1720 had been made.

Upon return of the embassy, a new direct embassy to the Kalmyks had been sent but it was not allowed to cross the border with the explanation that “the Kalmyks are the old subjects of His Imperial Majesty and without his direct order not only can’t receive the foreign ambassador but even made their own decisions.” [1] If earlier, the Chinese ambassadors had been allowed to talk to them, this was done exclusively out of respect and friendship to the Emperor of China. The Qing had to swallow this.

The border discussion had been trusted to the Sava Raguzinski-Vladislavich, a Serb from Raguza who was on the Russian diplomatic service since the early 1700s.

He composed a preliminary text of the treaty which had been approved by Kangxi Emperor except for the border part, which should be discussed at the border region. The place of the congress of commissioners was chosen by the river. Bura (Boro) south of Selenginsk, which was considered the border of Khalkha-Mongolia. Here the Qing side was represented by dignitaries Longotu, Ceren-wan, Tulishen.

Arriving in the border area, Ragizonski, wanting to obtain accurate information about the Kerulen and Tola rivers, along which he proposed to lead the border, sent there a reconnaissance party led by S. A. Kolychev. As a result of this trip, it turned out that the mentioned rivers are 15 days away from the last Russian guard on the Selengin road (Barsukovsky). During the move from Beijing to the area of demarcation S. L. Raguzinsky saw that the Qing authorities were strengthening in Mongolia, and a Manchu military detachment was located near the place of the congress of commissioners. That's why he forced the construction of the fort on the Chikoi River river and alerted a governor of Siberia who immediately sent a strong Russian detachment to the site. Manchu attempt to repeat the Nerchinsk scenario failed.

Qing representatives away from the capital did not become more compliant, although they slightly reduced the size of their claims. They now proposed to draw the border along the tributary of the Selenga River. Jide (Jide), and finish her Ujungar possessions, near the Subuktuy tract. At the same time, Manchu diplomatics were against the joint description and demarcation of the border, as insisted on by the Russian side. Once again, the conferences followed one after another, without bringing practical results.

The negotiations were especially hampered by dignitary Longotu, who categorically rejected all attempts to reach an agreement and influenced other Manchu representatives. In this regard, S. L. Raguzinsky decided to get Longota removed from the conference. Having held separate talks with the chief Qing representative of Tseren-wang on this occasion, the Russian envoy achieved success: Longotu was recalled to Beijing and demoted. The Manchus eventually realized that they did not have an overwhelming advantage of forces, and the decisive course of action of the Russian representative caused them concerns about Raguzinsky's demands to draw a border line along Kerulen and Tola. This prompted Tseren-van to offer Raguzinsky to establish a border on the existing line between the Russian and Khalkha borders at the time of negotiations - through the Mongolian guard posts. A complete demarcation of the border and setting the border marks on a ground took two more years and the work had been finalized in 1723 [2] in Kyakhta Treaty.

While ceding a small territory claiming by the Khalkha khans, Russia got a much greater territory and official Chinese recognition of the Russian possession of the lands to the South from Krasnoyarsk and Kuznetsk, previously controlled by the Khalkha. When it came to the final demarcation of the border the Manchu representatives “cheated themselves” due to the ignorance of a local geography : all research had been made by the Russian expedition while the Manchu simply relied upon the imprecise old maps composed by the Jesuits. The Russian-Chinese border was determined west of the Argun River to the Shabin-Dabat Pass (Western Sayan Mountains).

The final treaty established the duty free border trade in Kyakhta, diplomatic protocol, arrangements for the Russian caravans and the rules for dealing with the minor border violations.

Well, of course, except for the border definition, neither side was fully sincere. The Chinese kept considering Russia a Chinese vassal, kept making the petty offenses in the letters addressing and played the old games with the caravan while the Russian did not stick to the item of a treaty requiring return of the escapees [3].

Border by the lower Amur and a territory directly to the North of it, remained undefined, which allowed the Russians to start (later) establishing their de facto presence ignoring the Chinese assumption that this is their land [4].

______________

[1] In OTL “Her ….” because it happened during the reign of Anne.

[2] 1727

[3] Except that later they invited the Chinese officials to confirm that one of the rebel leaders who fled to Russia and died from the pox is really dead. 😪

[4] Which they did not bother to explore, let alone populate, until it was too late.

Last edited: