Operation Georg

Carl Adolf Maximilian Hoffmann, Chief of the Imperial Staff

The Best-Laid Plans of Mice and Men

By late 1917 Hindenburg and Ludendorff had come to the conclusion that the war would be lost or won on the Western Front. This was the very proposition of Falkenhayn's they had argued against from 1914 through 1916, but even during the preparations for the defensive battles of 1917, OHL began to realise that they had miscalculated Germany's military situation. The senior German military leadership in the west were divided on the issue. The two principle army group commanders, Crown Prince Wilhelm von Hohenzollern and Crown Prince Rupprecht von Wittelsbach, were unconvinced that Germany could win a military victory by this point. They wanted to make peace before the offensive, even if it meant giving up Belgium. Wilhelm expressed at the time to his chief of staff, General Friederich von der Schulenburg. "If the war could not be ended otherwise than by a military decision, and the statesmen could find no diplomatic method of leading the parties to the negotiating table, there was no other choice but to take the offensive." Lieutenant Colonel Georg Wetzell, the head of OHL's Operations Section, Rupprecht's chief of staff, Hermann von Kuhl; the chief of staff of the Fourth Army, Fritz von Lossberg; and Ludendorff's replacement as Chief of Staff on the Eastern Front, General Max Hoffmann - the latter three of whom were arguably the best field chiefs of staff of the war, saw no alternative either. Ludendorff continued to reject any peace through negotiation.

While OHL continued to debate whether or not to attack, and if so where, none of Germany's political leaders had a voice in the decision. Ludendorff decided the Germans had to attack, he just wasn't sure where, how, or when. His key advisors were even more divided on those questions than on the primary question of whether or not to attack. On the 11th of November 1917 Ludendorff met at Rupprecht's headquarters in Mons with Wetzell, Kuhl, and Schulenberg. They did not reach a decision. Ludendorff then ordered the development of an entire set of courses of action, and issued his basic planning guidance. The decision on where, how, and when would be made later. Once OHL made the decision to attack, they then had to decide where, when, and how. The decision against whom was a function of the decision where. The process of making the decisions on where and when played out over a period of ten weeks, involving three major conferences and a large number of estimates and memorandums circulating among OHL and the army and army group headquarters. During that period, a number of course of action analyses were also initiated to address the specifics of how the offensive would be carried out.

Despite Ludendorff's strong leanings towards an early offensive at St. Quentin, no final decision was reached at the Mons Conference on the 11th of November 1917. He ordered further staff studies and the course of action development of five principal operational options: ST. GEORG centered on Hazebrouck; MARS centered on Arras; ST. MICHAEL centred on St. Quentin; CASTOR north of Verdun; and POLLUX east of Verdun. Ludendorff held his second major planning conference with the army group chiefs of staff at Krueznach on 27th December 1917. Again, no final decision was made, but Ludendorff said that the balance of forces in the west would be in Germany's favor by the end of February, making it possible to attack in March. At the conclusion of the conference OHL issued a directive to the army groups to plan and start preparing a complete array of operations spanning almost the entire German front.

The completed plans would be due on 10th of March 1918. Rupprecht's Army Group was directed to plan GEORG II in the Ypres sector; GEORG I in the Armentieres sector; MARS in the Arras sector; MICHAEL I in the direction of Bullecourt-Bapaume; MICHAEL II north of St. Quentin toward Peronne; and MICHAEL III south of St. Quentin toward Le Fere. Both Rupprecht and Kuhl had serious misgivings about launching GEORG II from Mt. Kemmel toward Bailleul, because of the heavily cratered ground in the Ypres sector. Both also considered MARS virtually impossible. Crown Prince's Wilhelm's Army Group was directed to plan ACHILLES, an attack by the First Army west of Reims; and HECTOR, an attack by the Third Army in the Argonne. Wilhelm's and Gallwitz's Army Groups were directed to jointly plan CASTOR, west of Verdun; and POLLOX, south of Verdun. Albrecht's Army Group was directed to plan STRASSBURG in the direction of the Breusch Valley; and BELFORT, a defensive operation in the south.

Ludendorff announced his final decision at the Aresens Conference on 21st January 1918 - barely two weeks before his dismissal. Setting the tone for the entire meeting, Ludendorff made his famous remark: "We talk too much about operations and too little about tactics," which has often being linked to his fall from power - overlooking the grand picture in favour of the immediate objective. Summarising the various options, Ludendorff ruled out GEORG as too dependent on the weather. A late spring in the area might delay the start of the attack until May, which was far too late for Ludendorff - however there were some, most vocally Lossberg, who argued that the offensive could be delayed as far back as mid-late May with minimal movement on the Western front in a bid to keep American troop transports to their current trickle. He also said he thought it necessary to take Mount Kemmel and the southern Bethune hills, which added to the difficulty of the operation. MARS was too difficult all the way around. MICHAEL, then, on both sides of St. Quentin was the decision. "Here the attack would strike the enemy's weakest point, the ground offered no difficulties, and it was feasible for all seasons. Ludendorff, however, decided to extend MICHAEL's northern wing to the Scarpe. Supporting attacks by the Seventh Army were ruled out for the time being, because while such attacks might tie down the local reserves, they would also pull in the Allied strategic reserves that much faster (1).

When Max Hoffmann became Chief of Staff for OHL, he thus inherited a series of military plans and considerations stretching from one end of the Western Front to the other. However, the key events of late January and early February which had culminated in Ludendorff and Hindenburg's reassignment threw Ludendorff's decision of the 21st January completely into the air and prompted a complete reassessment of the situation, as the struggle in the Baltic drew away key forces meant for the Western Front. In a series of meetings with all the men who had participated in the Aresens Conference, Hoffmann conducted a reevaluation of the decisions made by Ludendorff. Hoffman also began appointing a series of talented men to various prominent positions across the front, foremost among them being the promotion of Georg Bruchmüller to General of the Artillery. This was coupled with Hoffman's decision to give Bruchmüller front-wide command of German artillery with a mandate to implement his own techniques and the Pulkowski Method in all attacking armies alongside the authority to override all opposition to this (2). At the same time Hoffmann decided to shift the timing of the offensive to early-May in a bid to buy time for the war to end on the Eastern Front and to ensure that the German Army was as ready as it could be when they launched the offensive. This delayed timeline for the German Offensive fundamentally reshaped the decision-making behind the Spring Offensives and allowed the OHL to make significant changes to the plans laid out by Ludendorff (3).

First and foremost, was the decision made by Hoffmann to place the main focus of the offensives in Flanders, basing the initial planning on the work done for the GEORG I and II war plans. During the preceding months of deliberations, Wetzell had at first recommended an attack in the vicinity of St. Quentin, followed as soon as possible by an attack in Flanders. Wetzell had envisioned the St. Quentin offensive as only being conducted up to a fixed line, and for the sole purpose of pulling the British reserves down from Flanders. Kuhl had also recognised the necessity for such a diversion in his original proposal. As Kuhl and Wetzell saw it, the main attack would be directed toward the critical rail hub and supply dump of Hazebrouck, with the objective of rolling up the British front from the north. It was the bare bones of this original proposal that Hoffmann had returned to by the end of his survey of the front, during which he had gained an understanding of the views held by the various commanders and chiefs of staff (4).

As a result, the original plans for Operation MICHAEL would be significantly scaled back, renamed as MICHAEL I, with the aforementioned fixed line that the Germans would advance to being set along the Croazat Canal and the Somme River between the Oise River and Péronne. This would then be followed by two significantly expanded offensives in Flanders named GEORG I and II. GEORG I's objective would be to capture the largest British supply point near the front at Hazebrouck before racing to capture the Channel Ports, in effect seeking to cut off the British army in the Ypres Salient and the Belgian Army from the remainder of the BEF. At the same time, large subdivisions of this central thrust would sweep through the Béthune region and support the German assault on the Ypres Salient in GEORG II. In the zone of the group of armies these objective would best be attained by an attack near Armentieres--Estaires against the flank and rear of the mass of the British Army in the Ypres salient and west thereof. Rupprecht's planners had previously identified the Portuguese sector of Armentiére-Estaires as the weakest and therefore the best break-in point.

This would be coordinated with GEORG II, which had the aim of holding the British and Belgian armies in place while trying to cut off the central railway point at Poperinghe behind Ypres through an assault down the Staden-Proven Railway on the northern flank of the Ypres Salient between the British and Belgian armies, the end goal of GEORG II being to cut off the Ypres Salient and Belgian Armies before moving on to the Channel Ports. If all of these Offensives were successful and the Americans had not yet come onto the line in large numbers, then the German Armies would follow this up with GEORG III, consisting of a general push to the Somme from Flanders, and Michael II, which would be a main thrust up the Somme aimed at capturing Amiens. If successful, the Spring Offensives planned by Hoffmann would ensure the capture of all France north of the Somme, open the English Channel to U-Boat harassment and would place the German front line on the easily defensible Somme River - forcing any assault on German positions in the north to first have to ford one of the greatest rivers in France and allowing the redistribution of forces elsewhere along the front (5).

Footnotes:

(1) Just a note that everything prior to this point is completely based on OTL. I would point you to David Zabecki's PhD Thesis on the German Spring Offensives if you want a lot more detail on all this. It is absolutely magnificent. It also has several really good maps in it that should help illuminate what is going on.

(2) IOTL the Pulkowski Method of firing without registering shots was only rarely used outside of the areas Bruchmüller was personally responsible for, and there was a great deal of hesitancy about using it on the Western Front. ITTL Hoffmann, who was personal witness to the effectiveness of Bruchmüller at Riga, is far more determined to force it on the German Army's artillery commanders on the Western Front. With the added time from the delay in the offensives he is able to force a far wider adoption of these methods, meaning the German artillery is more effective on a broader level than IOTL. The problems of using the Pulkowski method outside of trench warfare will of course play a role, but the initial artillery usage in offensives will be more successful on a broader scale.

(3) IOTL OHL experienced significant disagreements regarding when to time the offensive. Some argued for the offensives to be timed as early as possible, with Ludendorff himself being the largest proponent of this position. However, there was a pretty large minority in the OHL who rallied behind Lossberg - who believed that delaying the offensives to as late as the end of May would not have too large of an impact in regards to the American troop numbers, arguing also that while the transport of American forces remained low for the time being, in the case of an offensive they would be able to rapidly escalate the number of troops available to them. Lossberg's predictions were surprisingly prescient, given that is exactly what happened IOTL. Thus, I personally think that a delay of the offensive to as late as mid-May would not have too much of an effect as regards American troop numbers on the continent - I actually think that without the sudden increase prompted by the Spring Offensives the numbers transferred would have held steady which means that there might actually be around 80,000 fewer Americans in France by the 1st of May 1918 than IOTL.

(4) The really interesting thing about Wetzell's proposed series of offensives is how much they resemble the series of consecutive offensives launched by the Allies during the Hundred Days' Offensive IOTL. Where the OTL Spring Offensive was a single massive thrust at St. Quentin, Schlieffen-esque in style, the offensives ITTL are more a series of coordinated operations meant to constantly push the enemy back and forth between disparate fronts in a bid to disorient and tire them out while weakening the point under assault.

(5) This alternate Spring Offensive is based extensively on the various different war plans being discussed at the time, as laid out in Zabecki's thesis. All of the plans laid here are based on discussions and considerations held by the German OHL at the time without Ludendorff there to intervene. Ludendorff's primary reason for rejecting the Flanders campaign IOTL was that it would have to start too late for what he wanted to accomplish, ITTL with the delays forced by the campaign in Russia and Hoffmann's changed timeline, the Wetzell plan becomes far more workable. Key factors in it are the initial focus on the weakened British Fifth Army which crumbled IOTL, while removing the elements dedicated further north, before launching the assault in Flanders with the full weight of the offensive behind it rather than as a desperate gamble - as happened IOTL with Operation Georgette.

Map of the Final Plans for the German Spring Offensive

The German Spring Offensives

Even before the final decision on the location of the offensive had been made, Rupprecht's Army Group on 25th December issued general preparation guidelines establishing two main preparation phases; a general phase lasting approximately six to eight weeks, and a close phase lasting four weeks. The plan established the requirements for the extension of road-networks and narrow-gage field rail networks; extension of communications nets for the various headquarters, the artillery, and aviation; establishment of routes of approach, march tables, assembly areas, and divisional zones of action; establishment of command posts and observation posts; establishment forward airfields and the pre-positioning of required tentage; and establishment of artillery and trench mortar firing positions and the pre-positioning the ammunition. During the final phase, units would be moved up and emplaced in the following order of priority: First, corps headquarters; artillery headquarters; and communications units; Second, divisional staff advanced parties; artillery staffs; engineer staffs; ammunition trains; and motorised trains; Third, artillery units; air defence units; labor and road construction companies; aviation companies; and balloon detachments; and Fourth, divisional combat units; horse depots; bridge trains; subsistence trains; medical units and field hospitals.

Once all of this was in place, the preparations at St. Quentin finishing a week prior to those in Flanders, the Second and Eighteenth Armies, who had been assigned to MICHAEL I, opened fire on the 30th of April 1918 following a meeting of the OHL the previous day. Thus began the German Spring Offensives of 1918. Following a complicated seven-phase bombardment pre-planned by Bruchmüller using the Polkowski Method and Bruchmüller techniques, a creeping barrage was begun behind which the Assault Divisions dedicated to the effort launched their frontal assault on the Fifth Army positions. The Germans advanced rapidly, closely followed by the accompanying artillery units who began exchanging direct fire with the British artillery by the afternoon of the 30th. By early afternoon the Germans were up to the Fifth Army's battle zone and were preparing to attack it. By the end of day, the British Fifth Army's III Corps and 36th Division of XVIII Corps were fighting in the rear of their battle areas and most of the British artillery positions had been overrun. By the end of the first day, the southern edge of the German assault had reached the Croazat Canal, where the assault divisions with their stormtroopers turned northward and began sweeping up the Somme, while the slower trench divisions were tasked with building up their defences to their rear along the Oise and Croazat Canal in preparation for an Allied counterattack.

The following two days would see the embattled General Gough, commander of the Fifth Army, order a retreat across the Somme on the 1st of May, which was completed by the 2nd. At the same time, alarms sounded at British GHQ and in the French Military headquarters as reinforcements were rushed to contain the breach. It was unclear to the Allies that the MICHAEL I Offensive had been limited in nature, and as such the British committed significant forces from both their reserves and from along the Flanders and Arras frontlines to strengthen the positions of the Fifth Army. The MICHAEL I Offensive came to a halt on the 3rd of May with the capture of the Péronne bridgehead, as British reinforcements thrown into the line forced their advance to a halt (6). However, while the offensive around St. Quentin had come to a halt, the situation was about to turn from bad to worse for the British further to the north.

As operations on the Somme came to a close by the 4th of May, the German Fourth, Sixth and Seventeenth Armies came to the end of their own preparations. The combined GEORG war plans called for a frontal attack to break the British First Army around Béthune in order to allow for the capture of Hazebrouck, followed by converging attacks against the British Second Army at Ypres, with the objective of surrounding it while it was cut off from the rear. If the Germans could secure the line of the Flanders Hills from Kemmel to Godewearsvedle, the British would be forced to evacuate the Ypres Salient. Most of Rupprecht's planners saw this line of high ground in an otherwise flat plane as the key to the entire area. That line of high ground partially encircled Ypres, starting with the very low Passchendaele ridge just to the east-northeast of the town, continuing to the south-southwest through the Messines Ridge, and then hooking almost straight west through a line of relatively high peaks. Mount Kemmel (156 meters), some 8 kilometers south of Ypres, was at the eastern end of that line. Mount des Cats (158 meters) near Godewearsvedle, south-southwest of Ypres, was at the western end. Farther to the west and separated from the Cats-Kemmel ridge by a stretch of flat ground, Mount Cassel (158 meters) was the last piece of high ground before the coast, wherefrom Dunkirk could be observed directly. That piece of high ground was a key objective of the GEORG II plan.

The Seventeenth Army would attack between the La Bassée Canal and Estaires. Once it broke through, it would attack the British forces to their north on the flank and rear. The right wing of the Seventeenth Army would cross the Lys and march for Hazebrouck from the south. The center would march through the central area between the La Bassée Canal and the Lys River until it reached their joining point and cut the railroad between Béthune and Flanders - greatly lengthening the distance reinforcements from the south would need to cross to reinforce the British forces in Flanders. The left wing would screen the flank, but also be prepared to advance against British forces in the south around Béthune. In the second phase of the attack, the Seventeenth Army would form into three groups. The right-most and strongest group would split and move against Calais and Dunkirk; the left-ward and second largest group would screen the left flank and launch an assault aimed at capturing Béthune with its surrounding coalfields; all while the centre group remained in reserve.

The artillery requirement for GEORG I was estimated at 620 field batteries and 588 heavy batteries. The Sixth Army would attack between Estaires and Comines as part of Operation GEORG, with the aim of capturing the aforementioned high ground and supporting the Seventeenth Army's assault on Hazebrouck with its left wing. The central thrust of the Sixth Army's assault would be at Armentiéres before crossing the Lys and launching an assault on Mount Kemmel, sweeping down the ridge from there while clearing the low ground to its south all the way to Hazebrouck. Its right wing would attack the Ypres Salient directly, seeking to hold the British forces there in place while the Fourth Army sought to cut it off. This was the main task of the Fourth Army, attacking between Comines and Dixmuide - in the area between the Yser and Lys Rivers, would be to cut around the Ypres Salient and to capture its main supply depot at Poperinghe. While the southern thrust would come out of the Houthulst and onto the northern flank of the Ypres Salient, the central assault would rush down the Staden-Proven Railway, across the Ieperlee Canal, and the right wing would engage the Belgian Army from Dixmuide towards Renigenhelst breaking through the Belgian positions and driving for the left flank of the British Second Army (7).

On the 6th of May 1918 the three German armies in Flanders launched their long-awaited assault. The German artillery opened fire at 02.15 in the morning. At six hours and with eight phases, the preparation were even more detailed than the bombardment used at St. Quentin. Relying completely on the Pulkowski Method, the German guns fired onto positions based on a careful calculations and a grid bombardment with adjustments to the fire accomplished by balloon observers wherever ground observers could not see their targets. The rate of advance of the creeping barrage was slightly faster than at St. Quentin, with the Seventeenth firing a total of 1.6 million artillery rounds that first day - while over 4 million fell across the Flanders front lines and were heard as far away as London. Approximately one third of that total were gas; with the Yellow Cross inflicting almost 15,000 Allied casualties, and the Buntkreuz accounting for 5,000 more (8). At 08.15 the creeping barrage started to move forward followed closely by the German infantry. The heavy fog until late that morning, common in the region, favored the attackers and tended to prolong the effects of the German gas. The Portuguese divisions were completely shattered and largely surrendered in the initial assault, opening a massive gap in the Allied lines around Estaires, allowing the Germans to rush through and overrun the Allied rear, as the British on either side of the gap struggled to react under the massive pressure of the bombardment and assault. By 15.00 the Germans had reached the Lys at Bac St. Maur and soon reached it at Estaires as well. By that night their lead units reached the River Lawe at Petit Marais and Vielle Chapelle, a penetration depth of six miles (9).

Timed simultaneously with the Seventeenth Army's push to the Lys, the Sixth Army drove the British out of Armentiéres and crossed the Lys River by mid-day on the 6th. Fierce fighting around Neuve Eglise and Steenwerk would last late into the evening before the British were forced back. The Fourth Army would launch its attacks the following day, assaulting the northern flank of the Ypres Salient from the Houthulst Forest while other forces attacked down the Staden-Proven Railway and across the Ieperlee Canal. The fighting here would be among the fiercest of the Offensive, as desperate British and Belgian defenders threw themselves into the line following the initial breakthrough - contesting the crossing of the Ieperlee Canal while fighting tooth and nail on the outskirts of Ypres itself.

The second day of fighting had seen the Seventeenth Army cross the Lawe River and press further down the gap between the La Bassée Canal and the Lys River, while the right wing crossed the Lys near Merville and pressed into the Nieppe Forest. The left wing of the Seventeenth, meanwhile, turned south towards Béthune and advanced on the coalfields of the region, where they made good progress despite the intense resistance of British forces in the area, reaching the outskirts of Béthune by the end of the second day. The Sixth Army captured Messines early on the second day of operations and launched an assault on the Flanders Hills, specifically Mount Kemmel, with the division-sized Alpine Corps. The sheer weight of numbers, and the greatly strained British reserves in Ypres, meant that this initial attack succeeded in overrunning the defenders on Mount Kemmel despite heavy casualties, thereafter the surrounding ridgelines came under heavy assault from above. With the Kemmelberg under German control on the second day, the Germans were able to build a crossfire across the northern ridgeline which left the British in the Ypres Salient dangerously outmaneuvered (10).

It was the early capture of Mount Kemmel and events further to the west, that prompted the British commander, General Herbert Plumer, to order an evacuation of the Salient on the fourth day of battle. Under Plumer's scheme the Forward Zone was to be held while the Battle Zone and the rear areas pulled back, in hopes of convincing the Germans that the British were still in the salient. However, when Plumer and his staff had originally planned this maneuver, they had not counted on the German control of Mount Kemmel, wherefrom a warning was issued to German forward headquarters which prompted a renewed assault on the northern flank of the Ypres Salient as the British retreat came under way. Slamming through the Forward Zone with little difficulty, the Germans tore into the retreating British, who began to panic. As panic spread through the Ypres Salient, it began to collapse in on itself and men began surrendering in droves. The collapse of the Ypres Salient would net the Germans in excess of 50,000 prisoners, the single largest British surrender in its history, far surpassing the 10,000 who had surrendered at the Siege of Kut in 1916 (11).

By the end of the fifth day of GEORG II, the Germans had captured Ypres and were on the outskirts of Poperinghe - threatening a run on Dunkirk. It was at this point that Haig's infamous "Backs to the Wall" order arrived, demanding that every position be held to the last man, the order having been dispatched late on the third day of the GEORG I offensive in response to the critical situation in the Nieppe Forest. The German Seventeenth Army's assault into the Nieppe Forest, beginning late on the 7th, lasting through all of the 8th and the early hours of the 9th of May, was the most critical action of the offensive. Over the course of the 58-hour long battle, the Germans had found themselves fighting in open order through the forest, their artillery of little to no aid in the due to the heavy foliage and a lack of detailed maps making both registration fire and the Pulkowski method impractical at best. The result was that the fighting was dominated by close-quarters firefights between British and German squads tossed into the fray, one after the other. The bitter fighting eventually turned in German favor, as the outnumbered and outgunned British fell to the German storm troops who led this fighting.

It was the German victory at the Nieppe Forest, and their emergence less than a mile from Hazebrouck, that prompted Haig's order - aiming to arrest the collapsing situation. However, there was little the British at Hazebrouck could do in open country, with the German Sixth Army closing from the east and the Seventeenth advancing to the south, to hold back the Germans who were now able to bring their artillery to bear in open country, having moved it across the Lys river during the heavy fighting in the Nieppe Forest. By midday on the 9th of May, four days into the GEORG I Offensive, Hazebrouck fell to German arms. The fall of Hazebrouck prompted the complete unraveling of British positions in Flanders and was instrumental in Plumer's decision to order the retreat from the Ypres Salient (12).

Footnotes:

(6) Given the weakness of the Fifth Army's positions, which in the three months between early January and early March saw little improvement (which is why I don't think that a further two months would have much impact in this regard), combined with their problematic positioning on the battlefield and the like, mean that the Fifth experiences a similar collapse to what occurred IOTL in March. The limited nature of the offensive, and its focus on the southern end of the OTL Operation MICHAEL, mean that most of the OTL gains in the region are accomplished within a slightly slower timeline than IOTL (the Germans reach Péronne one day slower than IOTL) but that it halts much earlier and as such far fewer casualties are taken. While the initial few days of operation see the British and Germans take significant casualties, the fact that they only barely break out of the trench positions before they reach the Somme means that you don't have the same sort of open warfare that led to the absolute butchery of the last several weeks of the MICHAEL offensive IOTL.

(7) This is an adapted war plan based on the original plans laid out for Operation GEORG before it was cut down to KLEIN-GEORG and eventually GEORGETTE. The main difference from the original plans are the decision to reduce the German armies' frontage by shifting the German Seventeenth Army under Otto von Below further north to take on what was originally the most of the Sixth Army's responsibilities, shifting the Sixth and Fourth up the line in turn and allowing them to better concentrate their forces. At the same time, with more German armies in the area, OHL is better able to give them clear tasks - thus the 17th is focused primarily on Hazebrouck, the 6th on the Flanders Hills and the 4th on Poperinghe.

(8) The artillery bombardment for GEORG I and II are far more comprehensive than IOTL's GEORGETTE and are widely successful - even more so than IOTL. The bombardment here is actually even more comprehensive than that used at MICHAEL IOTL. The casualty numbers to the gas are based on the OTL numbers of Michael but adjusted to the changed location and the reduced frontage we are dealing with - meaning there are more men in closer quarters to each other.

(9) This is based almost entirely on how far the forces were able to get during GEORGETTE IOTL, but this is probably an underestimate of how far they could actually have gone ITTL. The thing to keep in mind is that GEORGETTE had a very heavy preponderance of trench divisions and relatively few assault divisions, meaning that when they attacked they moved at a significantly slower speed than they might otherwise have been able to. I have tried to stick with the GEORGETTE speeds where it makes at least some sense to do so, but keep in mind that this is probably an underestimate of the actual speed at which they are advancing.

(10) Already here, the GEORGE I offensive has been more successful than the OTL GEORGETTE offensive, which never succeeded in reaching Béthune due to the skilful defences of the two corps set aside in the region. However, the positioning of those specific corps in those specific locations is highly unlikely to be the case ITTL given how much shifting and movement there has been by this point in time - they are most likely somewhere on the Somme shielding against MICHAEL I. The Seventeenth Army also reaches the Nieppe Forest a couple days faster than the Sixth did IOTL, caused largely by the fact that there are fewer forces opposing them and the larger preponderance of assault divisions in these formations. The capture of Mount Kemmel is also a success the first time around ITTL, where it took two tries IOTL, which is again caused by the larger troop numbers available to the assault resulting from the GEORG Offensives being the focus of the Spring Offensives rather than a poorly allocated and rapidly prepared assault after the main thrust had failed - using exhausted men and rapidly transferred materiel. The capture of Mount Kemmel puts the entire Ypres Salient under the guns of the Germans, who can now use spotters there to grid-fire their artillery onto the exposed rear of the salient.

(11) The British retreat from the Ypres Salient happened IOTL under much better circumstances, but during its execution it was in grave danger from German assault and relied heavily on them remaining complacent before the Front Zone. Here, the gamble fails completely and turns an already critical situation into an utter catastrophe. The collapse of the Ypres Salient and the panic it produces allows for the relatively easy capture of Ypres, British being captured by the thousands as they try to flee for Dunkirk or Calais.

(12) Hazebrouck has been pointed out as a point of critical importance to the British war effort in Flanders, and arguably north of the Somme. Its fall is literally the worst (or second worst depending on how you evaluate the potential loss of Amiens) thing that could happen for the British at this juncture. Hazebrouck lies at the centre of the British rail network in the region and was not only the largest supply hub in the region but also the central transport juncture for the entire front in Flanders. IOTL the Germans came within five miles of capturing it and were unable to do so by a combination of Ludendorff suddenly deciding that he would rather have the Flanders Hills, redirecting the forces attacking Hazebrouck eastward, and significant Allied reinforcements. However, the French and British haven't yet granted power to a Supreme Commander of the Allied War Effort, though that is under way following MICHAEL I, and are only just beginning to realise that the main thrust is in Flanders, not at St. Quentin or in the French sector. The sheer vulnerability of the British positions in Flanders are honestly a bit mind boggling when you start reading up on them.

German Supply Column Crossing the Lys

It is the Follow-through that Counts

When MICHAEL I was launched in late April of 1918, it came as an utter shock to the Allied command, who had grown convinced that the danger had passed and that they were in the clear to the new year. They had even gone so far as to begin working on the actual war plans for 1919 in the weeks ahead of the offensive. The lack of an offensive by mid-April had been instrumental in convincing the British Admiralty that they could draw on the Channel squadrons to strengthen the convoy routes from Norway and had allowed the acrimonious relationship between Haig and Lloyd George to turn downright venomous over the issue of a Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces. Lloyd George had become increasingly instrumental in the push for a coordinated military command over the joint Allied armies over the course of April, greatly undermining Haig's influence in the process. The Allies experienced several days of crisis as Haig called on the bilateral agreement with Pétain for reinforcements to help shore up the British Fifth Army's positions across the Somme.

The French began moving the six agreed divisions from their deep reserves onto the line and followed them up with a total of five more over the following days. However, given the suddenness of the German assault and French fears that a second German stroke would come soon after in the Champagne, Pétain proved leery of committing too large a portion of his reserves at this point. The French troops first began arriving on the line where it was quietest, along the Croazat Canal and the southern Somme sector, where their initial attempts at a counter-attack were forced back by the entrenched German defenders, who used the Canal and River to the greatest extent possible to augment their defences. However, by the time the French troops arrived, beginning on the 3rd and 4th of May, MICHAEL I was on its last legs and the fighting was focused firmly in the north around Péronne, where the entire eight division reserve of the BEF had been dispatched alongside a dozen divisions from the Flanders and Arras regions. As the MICHAEL I offensive ground to a halt north of Péronne, the French grew ever more wary of committing any more of their reserves, with Pétain refusing Haig's final demand for reinforcements on the 5th of May, meant to replace the mauled Fifth Army (13).

Nonetheless, all the chaos and confusion that had accompanied MICHAEL I paled in comparison to the sheer panic that the first day of Operation GEORG prompted at British GHQ. Coming under the single largest bombardment of the war so far, the British lines had fractured and been driven into retreat, most critically in the Armentiéres sector. Haig dispatched orders southward to recall as many of the men sent south as he could while drawing even more heavily on the Arras divisions of the British Third Army. This, in effect, left the French to take back the entire British sector south of the Somme, while the reduced British Fifth Army was shifted northward across the river to help cover the Third Army's flank - causing even further tensions in the relationship between Haig and Pétain.

It was under these circumstances that Haig once more turned back to Pétain, begging for reinforcements in Flanders. Pétain rejected these please, answering that the expanded responsibilities following the British removal from most of the Fifth Army's former sector. He feared that the Flanders assault was simply another limited offensive similar to MICHEAL I, designed to drain away reserves so that when the "real blow" came, it could fall on a defenceless French line further south, possibly in Champagne or even around Verdun. This worry was given credence by the fact that all the necessary preparations for an offensive in the area had been undertaken by the Germans earlier in the year under the worried eyes of the French GQG - French General Headquarters (14). The British were on their own.

Since MICHAEL I had been launched, Haig had been pressing for the transfer of the men held in reserve in Britain and calling for the return of forces from the Middle East to help shore up the line, both actions which Lloyd George remained initially critical of before he realised the sheer desperation of the situation on the second day of Operation GEORG. As the scope of the catastrophe began to emerge, he gave permission for the beginnings of what would turn into a truly massive troop transfer from England - though it would take time for these men to be kitted out properly, formed into divisions and moved across the Channel. It was at this same point, in an effort to make an end run around Pétain, that Haig decided to call for a mission from Britain and to accept subordination to a French Generalissimo in order to secure French divisions for Flanders. Henry Wilson and Lord Milner, a member of the war cabinet, came over to confer with the commanders and Clemenceau. At Compiègne on the 9th of May and at Doullens on the 10th of May, Pétain’s pessimism made a bad impression on the politicians, in contrast with the insistence by Foch, who did not hold executive responsibility, that he would move in all available troops to support the British. At Doullens, Milner, Haig, and Wilson agreed with the French leaders to charge Foch with responsibility, acting in consultation with the national commanders, for "the coordination of the action of the Allied armies on the Western Front". Doullens was a moment of high symbolism, but not much more.

Although Haig felt relieved, the war cabinet was infuriated over Doullens, Lloyd George telling Milner that a French commander-in-chief was impossible. Foch had no staff and as a coordinator his function was ill defined. The Americans were not particularly pleased with the appointment of Foch without their own input, an antipathy towards the Generalissimo which was only worsened when he immediately demanded the transfer of American divisions to reinforce the collapsing British Armies. While the Americans were not opposed to helping the British, they strongly resented Foch's plans to simply subordinate American divisions to British and French army commanders. While General Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, would eventually be persuaded by Foch and Haig's entreaties, the American reinforcements would have little direct impact on the fighting of Operations GEORG. In sharp contrast, with Foch's ascension as Generalissimo, came the authority to force Pétain to transfer what forces he could to reinforce the British in Flanders. This would result in the transfer of first the French 133rd Division, which would be followed in the coming days by a total of 10 French divisions (15).

However, the Allied efforts at reinforcing the British forces in Flanders ran into hit a major snag at Béthune, which had fallen to German forces on the 9th. Here the Germans had turned the hills and coalfields surrounding the city into a bloody nightmare for the attacking Allies. Having captured the city itself and most of the surrounding coalfields, though not before the French miners flooded several of the mines, the Germans had dug into the hills and succeeded in bringing up heavy artillery to support their defensive positions. With the Germans using the summits of Haisnes, Grenay, Bouvigny and Beuvry as artillery spotting posts, the Allies found themselves charging directly into a meatgrinder. This in turn forced the redirection of Allied reinforcements all the way to the coast at Étaples before they could be transported by small railways to the front line.

While the British reinforcements from the Home Isles were initially directed to cross to Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk, British GHQ soon came to the realization that of the three, only Boulogne was relatively safe for the time being. This meant that British reinforcements were increasingly routed through ports further to the west, often as far away as Le Havre. All of this contributed to slowing down the Allied efforts at saving the British positions in Flanders, which eventually resulted in General Douglas Haig's fateful decision on the 13th of May 1918, one week into the offensive, to order an evacuation of Allied forces from Flanders north of a line running from Étaples to Arras, Boulogne being considered too close to the front lines, while preparations were made for a complete evacuation of France north of the Somme (16).

The capture of Hazebrouck on the 9th of May caused immeasurable chaos in the British lines as they were forced off their own rail network and onto the small and ill-prepared backroads of Flanders. However, the German Seventeenth Army also experienced significant disruptions caused by the massive supply depot at Hazebrouck which consumed much of the 9th and 10th of May, the soldiers struggling against military police dispatched to take control of the supply depots. Soldiers by their hundreds, and by their thousands, gorged themselves in an utter frenzy on what scraps they could secure from the lavish British stores before being chivied onto the line again in a foul mood and horribly indisciplined. This resulted in the infamous March to the Sea, as angry soldiers in the Seventeenth raided, plundered and destroyed everything in their path - shooting prisoners out of hand and burning multiple villages and minor towns to the ground. While the German Seventeenth Army Command sought to bring order and discipline back into the ranks, the horror spread by the now infamous Seventeenth Army consumed the Flanders countryside and prompted a massive flood of refugees fleeing the German depredations (17). Tens of thousands streamed south towards Allied lines while as many sought safety in the Channel Ports of Calais and Boulogne.

The British First Army under General Horne fought a bitter and bloody rearguard action at St. Omer which bought the British an additional two days, but by the 15th the Germans were on the outskirts of Calais and closing fast. In the meanwhile, the German Sixth Army had swept over the Flanders Hills and worked to clear the lands between the two advancing armies on either flank of the Ypres Salient. Mount Cassel was captured by the 11th of May and allowed the Germans to begin a bombardment of Dunkirk and its environs, where the British Second Army and the Belgian Army sought to conduct a fighting retreat to the port. The capture of Mount Cassel fundamentally undermined the British and Belgian ability to resist the continued pressure from the German Fourth Army. Despite their best efforts, neither King Albert of Belgium nor General Herbert Plumer, who was arguably one of the most talented Generals in British service at the time, could do anything to prevent their forces from falling to pieces. The Fourth Army, scenting blood, renewed its pursuit. Despite their best efforts, the British were able to muster little more than instances of local resistance for between half an hour and an hour at best before the heavy guns on Mount Cassel zeroed in on their exposed positions and tore the defenders to pieces. Tens of thousands of men were captured, culminating in Herbert Plumer and King Albert's surrenders to the Germans - King Albert, refusing to leave Belgian land, surrendered at the Franco-Belgian border at the village of Hagedoorn (18).

Dunkirk fell with barely a shot fired by the advancing Germans on the 14th of May while British efforts at destroying the town's port facilities proved for naught in the chaos of the British collapse. At Calais, the situation was quite different. With rumors running rampant, the remaining British forces in Calais decided to mount a last stand in a bid to buy time for the evacuation to continue. The resultant two-day long Battle of Calais left large parts of the town in ruins and more than ten thousand dead or wounded, while several of the docks in Calais were left damaged or destroyed - significantly reducing the port's capacity. Boulogne fell on the 18th of May, having been abandoned in the retreat south to the new line at Étaples, but had most of its port facilities blocked - which would require weeks of repairs by the Germans before it could be used on a large scale again. In the aftermath of Operation GEORG I, the German Army Command took a harsh stance against the conduct of several of the divisions of the Seventeenth Army, with numerous death sentences passed down, though these were often commuted to service at the hardest and most dangerous details along the front in an effort to prevent wastage of manpower (17).

Footnotes:

(13) I am basing a lot of this on the OTL response to Operation MICHAEL, though with some adjustments given the smaller scale of the offensive. The French were honestly amazing during MICHAEL, going far beyond what they had agreed to and throwing division after division onto the line to help keep the British and French armies in contact with each other. Haig doesn't make quite as many unreasonable demands, see his demand for 20 divisions to help protect Amiens IOTL, given the smaller and more contained nature of the offensive. However, the British exploit this chance to shorten their lines by turning over most of the front south of the Somme to the French. This in turn causes quite significant dissatisfaction and ruffled feathers in French GHQ.

(14) Pétain's actions here are similar to OTL though under somewhat different circumstances. The fact that MICHAEL I proved to be a limited offensive aimed at drawing away reserves, as the French High Command concludes, leaves them convinced that GEORG is simply another operation of that kind, designed to further distract the French before the main blow lands on them. They have good reason for this fear and, as can be seen from the Third Battle of the Aisne and the Second Battle of the Marne, their OTL transfer of most of their reserves to support the British positions severely weakened their own lines and left them vulnerable to assault. Additionally, the German OHL actually had considered placing the main thrust of the Spring Offensives against the French during their long period of deliberation IOTL, so all in all, Pétain is just being imminently reasonable.

(15) The appointment of Foch happens almost 1½ months later than IOTL but under similar circumstances. It bears mentioning that the Americans don't play a role in selecting Foch as Generalissimo and that the British government is extremely opposed to transferring such a large amount of influence and power to the French. Foch is a fascinating figure with undoubted talents who played an important role IOTL in securing victory, however, there are several problematic factors to his military thinking. Where Pétain was extremely aware of how fragile the unity of his army was, and wanted to limit offensive operations to minor actions until 1919 at the earliest, Foch was insistent on offensive action in large offensives - he was a large proponent of the Hundred Days' Offensive and actually shares a lot of the outlook that led to Nivelle's fall from grace in 1917. He believed in great, war-winning, offensives of the exact sort proposed and attempted by Nivelle the previous year. He was a main proponent of going on the offensive in the last half of 1918, rather than waiting for the Americans and attacking in 1919, and was able to string together a series of war-winning coordinated offensives over the course of the Hundred Days' Offensive. However, in doing so he also inaugurated one of the bloodiest period of the entire war, resulting in casualties numbering in excess of two million. Foch's appointment IOTL also resulted in Pétain having to bite his lip and accept transfer orders to much of his reserve, though it is more limited than IOTL due to the fact that the fighting is focused in the British and Belgian sectors of the front, rather than the junction between the French and British sectors as was the case IOTL.

(16) Haig IOTL laid plans for a complete withdrawal across the Somme during the Spring Offensives but was lucky enough that it never became necessary. Understanding the Allied rail lines in Flanders is vital to understanding how the British situation could collapse this drastically. Within Flanders there is a large coastal railroad that runs from Amiens north along the Somme before following the coast through all the port towns in the region, Étaples, Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk being among the most important. The only other rail network that wasn't in German control to get into Flanders at the start of the offensives ran through the Béthune environs and was largely used to ship coal south to Paris. The loss of the Béthune rail lines means that it is only this coastal railroad that the Allies can use to transport troops and supplies to the front by land - and while it is a major railroad, there is only so much traffic it can take. Losing both Béthune and Hazebrouck really completely cripples Allied transport capabilities north of the Somme.

(17) This is a mix of some of the things that happened IOTL when supply dumps were taken during the Spring Offensives, but with a much worse reaction than IOTL. This results from a combination of factors, and it should be mentioned that most of these actions are confined to a relatively small part of the Seventeenth Army, including the fact that these forces have fought primarily on the Eastern Front where this sort of behavior was tacitly accepted, and that they have just come out of some of the bloodiest and fiercest fighting of their lives during the Battle of Nieppe Forest. It is a matter of an all-around horrible situation being compounded by a series of horrible variables. This is something not really seen on the Western Front since the Invasion of Belgium and reinforces many of the stereotypes built in its aftermath, particularly in Britain and America. The relatively light punishment also really isn't too different from how the Germans ordinarily treated these sorts of things at this point in time.

(18) The surrender of King Albert is really the death knell of the Belgian Army and does little more than add to Albert's already towering stature in Allied propaganda. However, in practical terms this means that the British Second Army and the Belgian Army have both basically been destroyed in their entirety while the British First Army has few effectives left. The loss of Plumer is also a major blow to the British, who had previously considered him as a potential replacement for Haig. Unmentioned here, is the fact that most of the Canadian and South African Corps were lost in this rout - with the Canadian commander Arthur Currie captured in the fighting (more on this in the next narrative section). This entire series of events is an absolute disaster for the British, but the loss of most of the Canadian Corps and their extremely talented leader are among the bitterest. The 13th of May becomes a national day of mourning in Canada, the day that Arthur Currie was captured following a desperate rearguard action that was broken up by the guns on Mount Cassel, which also marks the effective end of the Canadian Corps as an operational unit.

British Prisoners of War Transported Towards The Rear

Bringing it Home

As the Germans continued southward, nearing the second week of the offensive, they ran into well entrenched and prepared British positions outside Étaples and were forced to a halt by the 20th of May, having long since outrun their supply lines. Max Hoffmann would declare the formal conclusion of Operation GEORG I and II on the 21st of May. Operation GEORG was the single most successful military operation on the Western Front in years, capturing vast swathes of vital lands and securing control of several key positions in the process. Several hundred heavy guns, amounting to a large part of the British heavy artillery, which had been concentrated in the region, as well as tens of thousands of tons of supplies, hundreds of tanks, only recently shipped over the Channel from Britain, large numbers of rolling stock and much, much more fell into the hands of the German Army. The loss of Hazebrouck, Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk meant that an immense section of the British logistical network fell under German control while the loss of the Béthune minefields would soon present the French government with critical coal shortages. By the end of the offensive the Germans had taken some 150,000 casualties, counting both MICHAEL I and both GEORG operations, but this was more than outweighed by what amounted to the complete annihilation of two Allied armies and the crippling of two more - the British taking around 200,000 casualties while an additional almost 175,000 ended up as prisoners of war (19).

Not since the great eastern offensives of 1915 had the Germans reaped such a bounty, and against a far more fearsome foe. However, the most impactful result of the offensive was to be the capture of the Channel Ports, which were soon put to use by the Germans. Using captured maps of the Dover Barrage from Dunkirk, the Germans were quickly able to open a path through the mines that had shielded the English Channel since the start of the war. With German engineers rushing into the towns to properly prepare the captured ports, the Germans dispatched most of the two Flanders Flotillas into the English Channel on the 15th of May. Here they began a rampage amongst the poorly guarded, overstretched and greatly pressed British Marine, as it sought to ferry almost 200,000 men across the Channel. The bloodbath that ensued saw several dozen transports sunk with casualties in the tens thousands, while numerous supply ships were sent to the bottom of the Channel and mine fields were laid in the most trafficked parts of the Channel.

Over the course of a week, basing themselves primarily out of Dunkirk and later Boulogne, the Flanders Flotilla racked up success after success, the German Admiralty rushing light ships and submarines by the dozen into the Channel to support the effort. While the British Admiralty were swift to respond to this crisis, it would take them almost four days to return sufficient ships from the North Sea to slow the losses. However, there was little the British could do to prevent the Germans from contesting the crossings of the Channel or shutting them down with mines. The result was that the British shipping lanes across the Channel were pressed ever further westward. The Germans would, in effect, shut down the Channel to Allied shipping and force the British to reroute their shipping lanes to Brittany and into the Atlantic. This would have chain reactions all the way down the British logistical network resulting in a significant reduction in British logistical capabilities within the span of weeks (20).

The Allied Supreme Command was under immense pressure to solve the crisis they now faced, but they faced several immense challenges. The most immediate issue centred on the total loss of the Béthune coal mines which produced 70% of all the coal used in the Paris munitions industry. The loss of the mines thus triggered a crisis of armaments in both the French and the American armies, the second relying almost exclusively on the French for their arms. While the fighting around Béthune had died down by the end of Operation GEORG, there were a significant number of French military officers, foremost among them Generalissimo Foch, who wanted to launch as swift a counter offensive as possible to retake the minefields. However, the of placing a force capable of capturing Béthune from the rapidly entrenching Germans across the Somme would place them in an extremely exposed position, with the possibility of being cut off and surrounded a significant threat. For the time being the Paris munitions factories would be fed with whatever coal could be found. The result was the large-scale confiscation of coal set aside for heating during the winter as well as from various other industrial needs, while coal imports from Britain were expanded as much possible under the circumstances.

However, the British merchant marine was itself greatly occupied, as the British turned over as much of their merchant fleet as they could spare to transporting American troops as rapidly across the Atlantic as possible, on the condition that those transferred be frontline troops. Over the coming months, the American troop numbers transferred across the Atlantic would grow at a rapid rate from 45,000 in April to 135,000 in June before slumping to around 100,000 men in response to the great logistical demands in the aftermath of the German Spring Offensive. This, coupled with the losses taken in the English Channel, placed an incredible burden on the British logistical capabilities and forced the American government to make several unpopular shifts to the economy to bring it closer to a war footing. The most significant of these being ordering the temporary transfer of control to the government of large parts of the American merchant marine in order to supplement the war effort, though even this would have limited efforts given that most of the American marine was already engaged in supporting the war effort (21).

The discussions about whether to carry out an offensive in the Béthune sector brought the greatest challenge facing the Allies to the fore - namely that Allied control of France north of the Somme was now in a near unprecedentedly tenuous position. Given the great successes experienced by the Germans during Operation GEORG and the belief at British GHQ that another offensive out of either Flanders or out of Péronne could completely overrun Allied positions and leave the men in the Arras Salient surrounded, General Haig suggested a complete withdrawal of Allied forces south of the Somme. This would lessen the threat to the BEF, secure them a defensible front and greatly shorten the long supply lines currently keeping the BEF supplied. However, the prospect of losing such a large part of France seemed inconceivable in the French camp and the already testy relationship between the French and British military leadership very nearly collapsed completely when the proposal was presented. It would require the direct intervention of General Pershing in favor of the British position to break the deadlock, resulting in the decision on the 23rd of May 1918 to order a withdrawal of all Allied forces south of the Somme (22).

While the Allied forces began preparing for a retreat across the Somme, the German OHL had been hard at work directing their forces in preparation for the third phase of their Spring Offensive. The Seventeenth and Sixth Armies were tasked with taking up position along the Étaples-Arras line opposite the Allied positions in the region while the Fourth Army was rushed south to the Péronne Salient in preparation for the planned MICHAEL II offensive aimed at Amiens and planned for the 28th of May. The British began their measured retreat from around Arras on the 25th, escalating rapidly over the following days as supply depots were emptied and shipped westward and as much of the infrastructure in the area was ruined while troops were removed in stages - the Front Zone emptying last. Up and down the front this occurred in a staggered manner, beginning at the furthest forward positions around Arras and spreading down the line. The result was that when the Germans launched themselves forward on the 28th they attacked positions greatly weakened, but still partially manned.

The Germans broke through with astonished ease but soon realised what was going on, rushing to capture and preserve what they could. Realizing the jig was up, Haig ordered all forces remaining north of the Somme to abandon their positions and to make their way across the river as quickly as possible, destroying what they could in their wake. This disruption to the Allied plans of retreat meant that while significant damage was done to the supply depots and the like, the rail network escaped most of the destruction due to its vital role in evacuating the British. In all, the Germans would capture some 15,000 men and inflict around 5,000 casualties during this period. By the 2nd of June, the Germans were in position along the Somme and were digging in - the British doing the same across the river from the Germans. The German Spring Offensives had come to an end after a month of intense combat, and the German OHL now began preparations for what was to come. With the military offensive having come to an end, Chief of Staff Max Hoffmann now turned to his political ally the Graf von Kühlmann, Germany's Foreign Minister and Chief Diplomat.

Footnotes:

(19) The casualty numbers are based on a cross between Operation MICHAEL and GEORGETTE IOTL, while taking into account the fact that there has been limited Allied resistance to the German assault compared to OTL, for reasons explained above. Perhaps the most important loss here is the large segment of the British heavy artillery force, with its advanced institutional knowledge. Many thousands of highly experienced British artillery soldiers are lost during this assault as the armies defending them collapse around them and their supply lines largely fall into German hands at the same time. Heavy artillery is difficult to transport, and following the loss of Hazebrouck it becomes almost impossible to evacuate. This marks a major setback for the British artillery wing which will take a good while to recover from. The vast majority of the prisoners taken stem primarily from the failure of the Ypres Salient evacuation and the subsequent collapse of the British and Belgian armies.

(20) This is why the British were so obsessed with securing the Channel Ports IOTL and why they were so opposed to allowing the Germans to retain control of the ports during the negotiations during the Great War. The fact that they were able to limit the Germans to Zeebrugges and Ostend, meaning that they were kept east of the Dover-Calais line, meant that the English Channel was largely uncontested during the war IOTL. However, the moment that the Germans have a relatively secure port behind the Dover Barrage this all changes. The short trip and near-constant stream of ships moving back and forth make these shipping lanes absolutely ideal targets for the German U-Boats and make a convoy system next to impossible in the region. The most important aspect of a convoy system is that it gathers all the ships together in one part of the ocean, which makes finding the ships a much greater challenge, but in the Channel it is almost impossible for the British to hide away.

(21) The Béthune coal mines are absolutely vital to the French war effort and losing them could well mark the beginning of the end for the French war effort. They are far from throwing in the towel, but losing Béthune is probably among the worst things that could happen to the French. For now the French will have to make do with what they can scrounge up, but they are having to really dig deep into the sorts of coal sources that you really don't want to mess with. Winter heating, other manufacturing requiring coal and other such sources are all experiencing a precipitous drain on their supplies. At the same time, the Allies are experiencing a general stretching of their supply systems as the requirement for American troops in France, British supplies and troops and coal supplies for the French all clamour for the same shipping. This is untenable in the long run, but for the time being the Allies are making it work.

(22) This was seriously considered IOTL under significantly less dire circumstances by British GHQ. I had actually originally planned to have GEORG III and MICHAEL II play out in the next update, but I just can't see how I could argue for the British remaining in position when their positions are this compromised. The British have just taken the beating of a lifetime, lost one army and seen the crippling of two more, and their two remaining fully functional armies in the area are in a massive salient. In addition, while the southern side of the Salient, going through the former battleground of the Somme battlefield and marked by quite rough terrain further north, would probably be hard terrain to take from the British, the northern flank is in dangerously flat land, ideal for offensive action. The Allied positions just aren't feasible any longer.

Summary:

The Germans prepare for the Spring Offensives, but change leadership mid-stream and are forced to reevaluate their plans.

The German Spring Offensives begin with MICHAEL I and is followed rapidly by GEORG I and II. Within the first week, both GEORG offensives seem on the verge of success.

The Allies react to the Spring Offensives but the Germans succeed in crushing Allied resistance in Flanders.

The consequences of the German victory in Flanders play out, as France experiences coal shortages and the British come under assault in the English Channel. Following heated deliberations, the Allies retreat across the Somme River.

End Note:

I am really sorry about the absolute monster the footnotes turned into for this update, but I feel that I really need to justify every single change and shift from OTL in this update and to clearly show my thinking behind it. I strive for plausibility as much as possible with my timelines and I do think that my alterations to the OTL war plans make a good deal of sense, but I would like to hear what everyone's thoughts on its plausibility are.

This is really a critical update for the TL that sets out a key development of the TL as a whole. I will admit that I have a lot of things breaking the way of the Germans in this update, possibly to the point of implausibility, but I hope that I have presented my arguments for the course of events in this update in a clear fashion and made clear how close something like this is to what might have been.

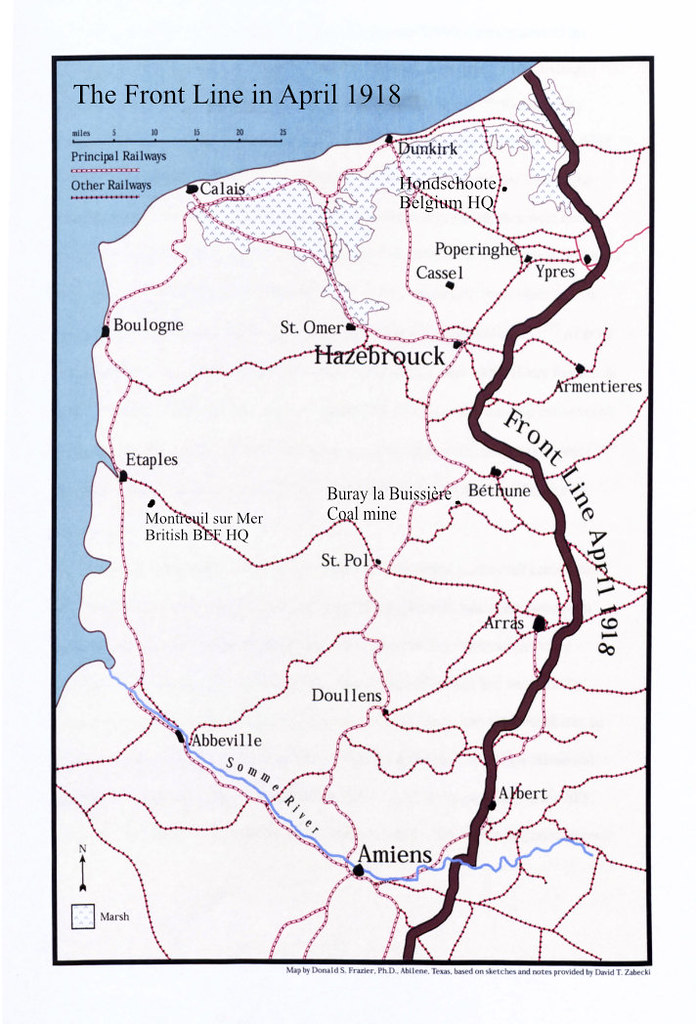

A last note, the map of the German War Plans has a mistake, with GEORG I labelled as GEORG II and GEORG II labelled as GEORG I. This is a mistake on the map, and shouldn't be present in the actual text. I have also included a map below that outlines the rail network in the region and contains many of the key locations mentioned above - disregard the frontlines, it is an OTL map and they don't match.