Freeing the Mouse: How Disney Flipped the Script on Copyright

Bloomberg, July 2008 Edition

In 1998 the 105th Congress, spurred in large part by the recent passage of the EU’s

Copyright Duration Directive and intense industry lobbying, passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, a.k.a. “The Sonny Bono Act” after its sponsor, a.k.a. “The Porky Protection Act”. It might have been called “The Mickey Mouse Protection Act” save for one major factor: Walt Disney Entertainment was not advocating for the bill.

For those who see Disney as a “friendly family company” overseen by the smiling faces of Walt Disney and Jim Henson, it might seem the anathema of the “House of the Mouse” to support such “greed-driven corporate welfare”. But the fact remains that the Walt Disney Entertainment Company, Federal Stock Listing “DIS”, is a major international Fortune 100 corporation and one of the Dow Jones 40 that benefitted greatly from the Act’s passage. And in the past, they openly supported and even actively lobbied for similar legislation, being a prime driver in the similar 1976 Copyright Act.

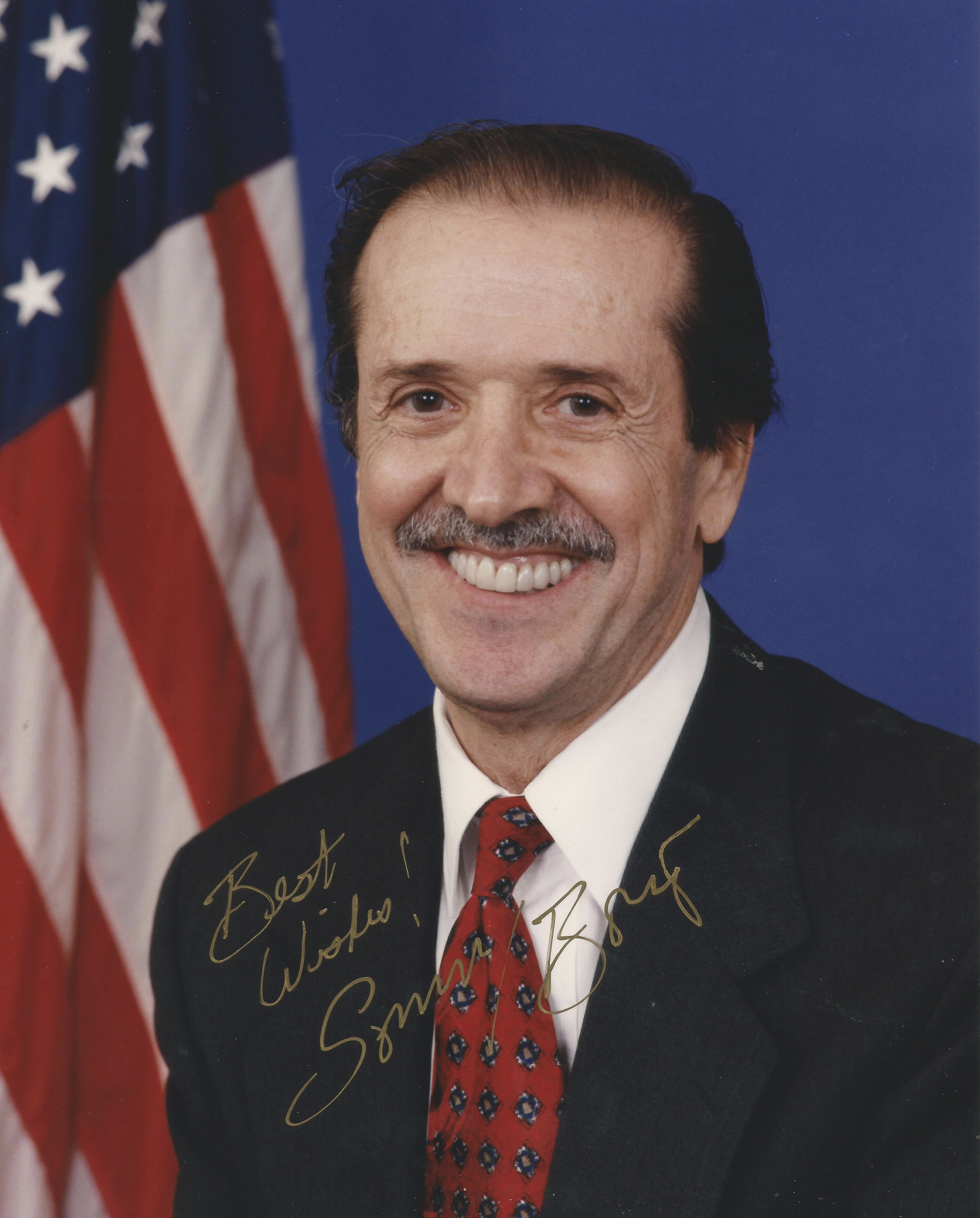

The Bill’s Sponsor, Representative Sonny Bono, 1998[1]

And unlike Porky, who had until 2010 before Copyright expired on his first appearance, 1935’s “I Haven’t Got a Hat”, Disney’s most iconic character, indeed their central Trademark image, Mickey Mouse, was set to enter the Public Domain in 2003 when “Steamboat Willie” reached the 75-year mark.

And make no bones about it, many at Disney were pushing for full support of the bill, Vice Chairman Roy Disney chief among them.

But, interestingly enough, Disney had already slightly

loosened its copyright protections on certain derivative works under certain terms and conditions. And it all started with

Dungeons & Dragons.

We’ll get to that later.

By staying out of the fight, Disney avoided a torrent of bad publicity. Bono, of course, whose own musical IP gave him what was seen by many as a conflict of interest, became the butt of several jokes, with David Letterman suggesting that “Sonny never was one much to share/Cher”. And while numerous studios and the families of dead artists were supporting the bill, including Columbia, Universal, and United Artists, Warner Brothers became the poster corporation and their President and COO John Peters the “face of corporate greed”. Porky Pig, their most endangered asset, became irrevocably associated with the bill when Peters specifically called out the stuttering porker in a news conference supporting the legislation. The clear connection between “Porky” and “Pork”, or legislation that serves special rather than national interests, was unavoidable.

By staying out of the fray, Disney Chairman Jim Henson could, without deception, hypocrisy, or irony, declare his utter befuddlement about the whole deal, and even speak about how Disney was fully supportive of its fans and followers. Henson could, without irony, note how much Disney had benefited from Public Domain works, with a majority of Disney Princesses being derivative of classic Public Domain IP, like Cinderella and Snow White. Henson also saw little to fear with Mickey Mouse entering Public Domain. After all, almost anyone could use Mickey or other Disney Copyrighted material or even Trademarks within certain limited terms and conditions, and even make a small profit from them. Only the Steamboat Willie versions of Mickey and Minnie were to be “up for grabs” in 2003. And Disney still retained full Trademark protections in perpetuity under existing law.

The whole arrangement actually began very small, initiated by Tactical Systems Rules, or TSR, a division of Marvel Entertainment, itself a division of Disney. TSR, the company behind the iconic

Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game and similar products, had long had a very open and permissive relationship with its fans, going back to its early days in the late 1970s. “Homebrew” adventures, rules, characters, and monsters were de rigueur, and even occasionally got adopted by TSR as Canon. In fact, the Thief Character Class, one of the four cornerstone classes alongside Fighter, Mage, and Cleric, began as a Homebrew creation that Gary Gygax found fascinating and even helped shape when its fan-creators cold-called him.

When Marvel ultimately acquired TSR after being itself acquired by Disney, they acted in much the same way. And being such a relatively small cog in the giant machine of Disney, their laisses faire approach to copyright and trademark largely flew under the radar.

But this all changed when

Mickeyquest was born in the late 1980s. A simplified game based on the classic Disney and Muppets characters and meant to “help children expand their imagination while learning valuable social and math skills”,

Mickeyquest soon spawned its own Homebrew, this time using Trademarked Disney characters like Mickey and Donald! Disney’s legal team, the so-called “Legal Weasels”, cried fowl…err…foul, but TSR Chairman Gary Gygax pushed back, citing Homebrew as not just an indelible part of the gaming culture, but a rather lucrative source of great ideas and fan loyalty.

“I just made three million in profit selling a fan-written adventure module,” he told the board.

The issue of Disney Copyright and Trademark protections was a source of great consternation at the time. As

Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Waterston discovered to his chagrin, failure to enforce or take advantage of one’s Trademarks and Copyrights could, perversely, endanger them. One overenthusiastic Legal Weasel had, following this line of thought, sent a Strongly Worded Letter to the owners of a small private daycare who’d painted Snow White on one of their internal walls. Chairman Henson, mortified when the story reached him, openly apologized to the center and even sent them a donation and granted them a limited one-time allowance for use of the Trademarked image.

The possible price of not protecting your Copyright (Image source Etsy)

These two moments soon collided in the Weasel’s Den, and after long and reportedly “lively” discussions, a new ruleset was worked out: a Limited Open License Agreement (LOLA) that allowed for private individuals and certain child-associated small businesses and charities under a certain size and value threshold (such as day care centers) to “limited use” of certain Disney Trademarked images and Copywrite within a specified (and renewable) time frame, subject to certain restrictions, such as open acknowledgement of Disney Trademark and Copyright, where applicable. Also, certain “inappropriate representations” of the Disney trademarks would be absolutely forbidden (the “Disney-Pricesses.net” adult website stuck in their memory here), as would “anything used in the advocacy of hate, violence, or other things deemed at odds with Disney’s Company Values, as defined wholly by Disney”. Partisan political causes were wholly banned, though certain apolitical charitable and non-profit uses were allowable. Few restrictions were put upon derivative “Fan Works” done for no profit (though such works are generally considered allowable under “Fair Use” statutes anyway).

And most interestingly, in something that evolved directly out of TSR, some limited Derivative Works that met the Terms, Conditions, and Restrictions, could actually be used in a limited commercial fashion if used by narrowly defined “Independent Individuals” and “charitable organizations” who a) got advanced permission from Disney, b) gave Disney full rights to claim full ownership after reasonable compensation to the “Freelance Content Creator”, and c) if the Creator agreed to give Disney a percentage of all profits made once a certain minimum revenue threshold (originally $10,000, currently up to $55,000)[2] was reached. Disney profit share began at 5% and scaled up to 75% as revenues increased beyond the minimum threshold. To keep LOLA licensees small and thus limit their potential for becoming serious competition to official merch, a maximum revenue threshold was also established, originally $100,000, now $500,000, beyond which the LOLA licensee was given the choice of scaling back, ceasing sales of derivative works and ending the LOLA, or forging a formal licensing agreement with Disney.

This last aspect, it was hoped, would help limit the damage potential from “bad actors” trying to game the system by simply, for example, reinvesting all revenues into employee salaries or facilities, and thus having no real “profit”. A small measure of loss to such “profit hiding” was expected, with Disney figuring a little bit of “scam loss” was worth the good PR, comparing it to advertising expenses, but they clearly wanted to avoid massive abuses ran into six figures or more. An alternative option involving claiming a share of gross revenues was rejected since this led to the real possibility that the LOLA licensee might actually

lose money while Disney made money, creating bad press.

Also, as an “emergency stop”, Disney retained the right to unilaterally revoke any and all LOLA permissions as they saw fit. Though as we shall see, this didn’t always work as planned.

It’s worth noting that there may be a less-than-charitable reason behind the minimum threshold as well, as the legal and overhead costs of claiming their share would have likely exceeded any revenues Disney made below the lowest total revenue threshold. It’s also notable that Disney individual and family vacation packages for their parks and cruises are typically in the $5,000-25,000 range, with some Premium Packages going for $50,000 or more, meaning that successful LOLA Creators are primed with just the right amount of cash for a Disney vacation, leading to speculation that Disney is effectively giving its fans a tool to fund their Disney Vacation in a self-serving circle. Special deals for LOLA Participants would seem to confirm this hypothesis.

Even with these protections in place, Disney, with the potential of losing billions of dollars in IP should the plan backfire and nullify their copyright and trademark protections, started small. They began with the old black & white versions of Mickey and Minnie and Oswald and Ortensia, which were already endangered, as well as Snow White, which would be the first Disney Princess at risk of going into the Public Domain should the Bono Act fail. When Universal tried to reclaim the rights to Oswald claiming that the LOLA showed that Disney was no longer enforcing Copyright, the Legal Weasels managed to point to rock solid language in the LOLA and cite pertinent precedent on other Copyright claims to fend off the challenge. With precedent thus established that the LOLA’s very limited and revokable nature did not indicate a lack of intent for Copyright enforcement by Disney (as demonstrated by a quick quashing of an offensive use of Snow White), Disney began to periodically increase the list of LOLA-permitted characters, which were released in a phased approach that built anticipation, and thus interest.

This deal, which caused an uproar, with many predicting a disastrous spiral of lost IP rights and revenues, shocked everyone by actually

making a small revenue stream for Disney and not cutting appreciably into official merchandise sales. While revenues from the sharing arrangement and any “claimed with compensation” spec works are rarely more than a drop in the bucket for a company with a Market Capitalization of over $65 billion, it’s usually been more than enough to cover any litigation needed when people break the rules or abuse the LOLA. And the Disney fandom has been, on the whole, more than happy to report any abuses they see to Disney due to a combination of loyalty and fear that Disney, if they suffer enough loss from LOLA abuses, will restrict or revoke the LOLA entirely.

Still, abuses do happen and the Legal Weasels have to occasionally take legal action to quash LOLA rules breakers or those who “hide revenues”. To date, the largest LOLA-related case came down to battling an online “consortium” of merch creators working in collaboration, each individually making below the then-$35,000 threshold, but making over $2 million in aggregate revenues. The Legal Weasels managed to demonstrate that the consortium was working “in open collaboration” via public posts and subpoenaed emails and online money exchanges and was thus in open violation of the LOLA. Disney ultimately claimed their 75% plus interest and damages and revoked the LOLA rights for all involved.

A similar issue affected a single producer who would sell right up to the threshold, then close his business, and then restart sales under a different name. Eventually, his use of the same IP Address for his server left a clear indication that it was one person. The Legal Weasels managed to demonstrate that he’d been knowingly violating the spirit of the LOLA, and claimed considerable back-earnings, interest, and damages before revoking LOLA for him. They caught him trying it again under a different name, and drove him into bankruptcy.

But other times the Legal Weasels have had less luck. In one case a pair of collaborators set up a scheme where the first person set up a LOLA agreement for some Mickey figurines, then sold them in bulk to his friend at a loss, who in turn then resold them “second hand” for a profit, that they then did not share with Disney. Disney had a hard time proving collusion and profit-hiding since they left no clear paper trail, and local law enforcement was uninterested in investigating a possible scam netting only a few thousand dollars in total profit when much bigger issues were plaguing the district. It was also a considerable amount of work for the two alleged conspirators, who likely didn’t make much more than they would have by playing fair. Disney simply did not renew the LOLA at the end of the specified term. And Henson, upon noting the similarities of their scheme to many of the “Hollywood accounting” practices that Disney-MGM still used despite his best efforts to clamp down on them, reportedly joked to Tom Wilhite “maybe we should hire these guys to do accounting for MGM.”

Also, in one case Disney’s own legal precedent came back to bite them. Much discussion had occurred back when first drafting the LOLA about how strictly to enforce the letter of the LOLA, as a strict interpretation could lead to open loophole abuse while a “spirit of the agreement” strategy could make it hard to enforce certain clauses. Jim Henson pushed for a more “spirit of the rules” interpretation in order to “best stimulate creative opportunity”. This approach helped Disney in their case against the above loophole abusers, but bit them in the behind later in the case of the Imagine a Green Future Society, a small trade society of various scientists, engineers, and technicians working in the renewable energy industry. Disney was at first more than happy to approve a LOLA agreement for them, given Chairman Jim’s values. And indeed, their first LOLA product, a fundraising T-shirt involving Pluto the Dog and a “Pluto Reactor”, was found to be a “good fit”. The second year’s shirt, Don Quixote and a Wind Turbine, likewise raised no issues.

However, Year Three’s shirt featured Mickey and Walt Disney’s jovial, smiling frozen head and celebrated the “WALTS HEAD” cryogenic energy storage technology, which caused outrage with the Disney family. Despite Henson trying to talk them out of it (he reportedly snorted with amusement upon seeing the shirt; “Walt just looked so happy to be there!”) the Legal Weasels tried to revoke the LOLA, citing the “poor taste” shirt to be “at odds with Disney’s Company Values”. However, the Society pushed back, claiming that the attempted invocation of the emergency stop was contrary to the spirit of the contract. They’d paid their fees to Disney, followed the rules, worked in good faith, and argued that the T-shirt, which had been their most popular to date, was doing no harm to the value of the characters or IP, and that Disney was not suffering a loss or any harm (it might mock Walt a bit, but his likeness as a public figure was not covered by LOLA and ultimately protected satirical free speech). And ultimately, a judge agreed. This resulted in Disney revising the LOLA to include limitations on the use of Walt and other Disney employees, and ultimately buying up the rights to (and all remaining items featuring) the WALTS HEAD design.

Unfortunately for Disney, and as Henson may have predicted, the story went viral on the Net, and the ensuing publicity resulted in the shirts and image, which previously had only seen a very small distribution among tech sector employees, becoming world famous, the offensive image plastered across the Net, and the few remaining shirts in circulation becoming valuable collectors’ items. Furthermore, this type of effect, where attempts to cover something up only speeds its mass discovery, has since been dubbed “The Walt’s Head Effect”[3] by the press.

The Legal Weasels have also had harder times battling Chinese and other foreign-located entities selling unlicensed and counterfeit merch irrespective of the LOLA, but Warner and others are having the same issues, LOLA or no LOLA. That’s just increasingly the price of doing business in the modern economy when a growing economic power fails to respect international IP law!

And yet despite these setbacks, the LOLA has in general had the effect of greatly improving public perceptions of Disney, gained them an almost obnoxiously loyal and vocal fanbase (who gladly rat out abusers), and even led to the occasional “big deal”, such as Jeff Marx and Robert Lopez’s 2001 minor hit

Kermit, The Prince of Denmark, which made noteworthy profits on Broadway, the Big Screen, and home media alike, and led directly to follow-up deals with the two up-and-coming playwrights.

Coming soon… (Image source Goodreads)

Similarly, a recent animated short featuring Marvel’s

Blade, done “spec” under LOLA by a CalArts student as his final project (and who subsequently went to work for Whoopass Studios), caught the attention of Marvel Chairman Stan Lee and CEO Jim Shooter, which led to an upcoming animated feature length movie from Whoopass Studios, set to enter production in 2010.

While it remains to be seen what the long-term effects of the LOLA will be, in the past decade it has been a public relations coup and a small new revenue stream and freelance content creation pipeline. No one has tried to challenge the legality of LOLA in court as of yet (though Warner reportedly threatened to), and had the Bono Act failed, Disney would have gotten out ahead of the deal, and positioned themselves to retain some limited control over post-2003 content.

Either way, the growing Internet is already becoming a haven for Fan Works and Homebrew, with LOLA-derived Disney/Muppets/Marvel IP leading the pack. And numerous smaller companies, such as Whoopass and Bird Brain, have set up similar LOLA-type systems. Paramount has begun experimenting with a LOLA exclusive to

Star Trek, given the already rabid fandom. And Lucasfilm is reportedly “in serious debate” about following suit.

“If properly enforced, monitored, and managed, a LOLA-type arrangement can make a notable profit,” said one Harvard Law School professor. “In Disney’s case, it has actually reduced counterfeit merch since it’s generally cheaper to give Disney their due percentage than it is to fight them in court, and a single letter in the mail usually leads to a fast out of court settlement. A few people have gotten away with flying under the radar for a while or abusing loopholes, but Disney’s engagement and enforcement of the LOLA rules has made clear to patent lawyers that they have no intention to relinquish their IP copyright or trademark in any fundamental way.”

And while Disney openly engages with the LOLA content creators and only occasionally has to stamp down on “Trolls” creating inappropriate work that violates the LOLA, WB has had the opposite reaction, increasingly gaining a reputation as a “bully” that quashes Fan Works featuring Batman or Bugs Bunny. And visit any internet message board or social media site, and you’ll see plenty of love for Disney, and plenty of hate for WB, leading the latter to start rethinking their policy on outside content creators.

“Should I be worried that some kid in Canada is making a few thousand dollars selling Kermit shirts on the net?” asked Jim Henson when asked about the LOLA in 2001, speaking hypothetically at the time. “Absolutely not! Particularly if he uses some of that money to go see

Kermit, The Prince of Denmark or fund a trip to Muppetland. Magic, like love, only becomes more magical the more you share it.”[4]

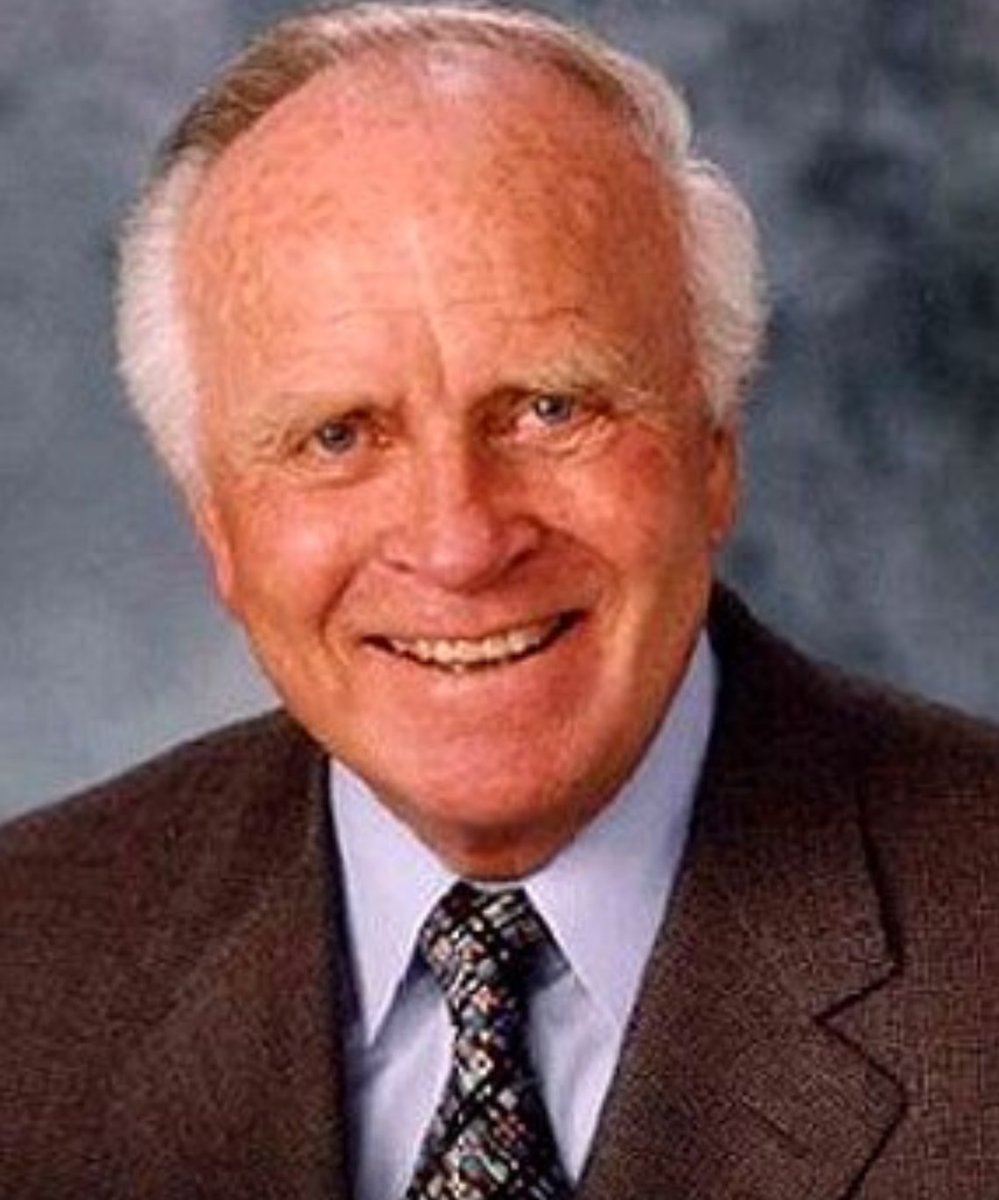

President Dick Nunis Retires, Replaced by Tom Wilhite

Disney Magazine, April 1999 Edition

(Image source I Know What Happened Today)

Anaheim – Being Disney’s President is a hard but important job! Richard “Dick” Nunis sure knows! And soon, current Disney-MGM Studios Chairman Thomas “Tom” Wilhite will be finding out for himself! Tom will soon take over from Dick as both Disney President and Chief Operations Officer, another important job keeping the company running! Tom and Dick have worked together well, without things getting too “hairy” as Chairman Jim Henson likes to say. Tom, on the other hand, will be replaced as Disney-MGM Studios Chairman by Michael Lynton, a former Disney Publishing VP who for the last few years has worked for Penguin Pictures as their Studio President. Welcome back, Michael!

Dick retired after over forty-four years working at the Happiest Place on Earth, having been originally hired by Walt Disney himself in 1955 to work at Disneyland. Dick thought at the time that it would just be a “summer job”. Little did he know! But before we “wave” goodbye to him (we’ll explain that reference soon!), just who is Dick Nunis? And who is Tom Wilhite? And for that matter, who is Michael Lynton? Let’s find out!

Dick Nunis’ Window on Main Street (Image source Flickr)

[Continues]

Jane Henson’s Nativity Coming to Immaculate Conception

Advertisement in the San Diego Union-Tribune, December 12, 1999

(Image source IndieGoGo)

Jane Nebel Henson, wife of Disney Chairman Jim Henson and co-founder of The Muppets, will be bringing a live performance of her

Nativity, a Bunraku-inspired puppetry recreation of the Christmas Story, to Immaculate Conception Church in San Diego on Sunday the 19th of December. Executive produced by MLB Commissioner George W. Bush and funded by the Walt Disney Company, Nativity is a stylistic and elegant retelling of what Christians consider Chapter 1 of the “Greatest Story Ever Told”. With brilliant and intimate puppetry choreographed by Jane Henson and Bruce Schwartz, the events recounted in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke come alive like never before. Beautiful and modern, the grace and magic of the performance is so real and so true that even the physical presence of the puppetry performers themselves cannot break the magic spell.

Perfect for all ages and open to all faiths, Nativity is a performance that celebrates beauty, divinity, and grace. Performances happen every hour on the hour from 10 AM to 7 PM on the 19th. Performances are free. Donations of food, toys, or money are encouraged with all proceeds to support the San Diego Food Bank and Toys for Tots.

Watch the beautiful puppetry of Jane Henson's Nativity Story Live Stage Tour. Remember that Christ is the #ReasonForTheSeason. 🎵 Listen:...

www.facebook.com

[1] The sheer randomness of Bono’s 1998 death in our timeline, asymptomatic intercranial hematoma following a skiing accident, is butterfly fodder to say the least.

[2] And if all of this sounds incredibly generous for a major corporation, it’s ironically based on the controversial, utterly despised Open Gaming License (OGL) 2.0 recently proposed by current D&D owner Wizards of the Coast. This proposed change to the OGL, which WotC abandoned after the ensuing outrage, claiming that they “rolled a 1” on that deal, would have been a drastic

reduction in rights for the fans compared to the OGL 1.0, which is pretty much a free license to do what you want with WotC Trademarks and Copyrighted material with a few restrictions. The Disney LOLA is far less generous than even the hated OGL 2.0, but ironically, this same idea, when proposed from the opposite direction (i.e. a company giving fans

more rights rather than less) would be seen as exceptionally generous rather than a greedy stab in the back.

And as to how this would affect Disney’s sales, just doing the basic math, if 1,000 people succeed in selling just under the $55,000 threshold, that’s hypothetically $5.5 million in revenue not made by Disney (assuming that every person who bought these LOLA products would have bought an equivalent official Disney product instead, which you can’t since some of it will be charitable or unique). However, it’s unlikely for that many people to make that much money given they’d be in competition with each other (much like how

very few people make a living on Etsy, but plenty of people make some “side cash”), and producing in sufficient bulk to reduce costs and increase profit margins would quickly push you above the $55,000 mark and result in you owing a percentage to Disney. And since Disney can sell in super-bulk and manage premium contracts with suppliers and official licensees, even with a noteworthy markup for “Official” Disney merch, they remain highly competitive since the small-fry would have higher per-item costs or have to reduced quality to stay competitive.

And even if Disney loses a few million in merch revenues on the deal on a given year, it’s still orders of magnitude less than they will have spent that year on advertising, and end up doing far more to boost Disney’s brand awareness and perception than a thousand commercial campaigns. Or so its continued proponents maintain.

[3] We’d call it

The Streisand Effect, based on Barbara Streisand’s 2003 legal attempts to quash a shoreline erosion scientist’s website that inadvertently featured an image of her California mansion. The lawsuit caught the attention of the web, causing the issue to go viral, resulting in tens of millions seeing an image that, prior to her legal attempts to quash it, had only been seen by a few hundred, mostly scientists with no knowledge or care about whose mansion that was. And a huge Hat Tip to

@El Pip for helping me “game” the LOLA system and coming up with the WALTS HEAD shirt saga!

[4] So, the obvious question becomes, “would this actually work? Or would Disney be opening up the floodgates to massive copyright infringement?” The short answer is “the significantly more generous OGL 1.0 worked for WotC”, though, while a very large publisher with over a billion dollars in revenue, they are far, far smaller than Disney even 20 years ago. And their recent attempt to change and restrict the OGL makes clear to me that they believed that they were losing revenue, while their willingness to quickly backtrack on that conversely indicates that their Public Image is more important to them than the “lost revenue”, suggesting that “boycott losses” from pissing off the fans would have significantly exceeded any revenues gained by implementing OGL 2.0 (I seriously doubt that Hasbro, WotC’s owners, really place their fans’ happiness over raw profits). The controversy of even

proposing the tightening of restrictions has apparently already

caused a major hit in revenue. Business Lesson #1: don’t piss off your main customers (Elon take note).

The longer answer would be “a lot will depend on how well Disney writes and enforces the terms of the LOLA, how clever the violators are, and what precedent is set by the initial judgements in the early enforcement cases and any subsequent appeals.” Though I’m no IP lawyer, I do deal with technical IP and Data Rights as part of my job and provide technical advice to the Patent Attorney on specific IP and rights issues, so I’m not

wholly ignorant here. And I have tried, along with

@El Pip (as you can fully see in the writeup), to “game” the system and figure out a) how to abuse the LOLA and b) how the Legal Weasels could fight back. My numbers and conclusions speak to my assumptions, though much is speculative here, so before you go trying such a thing with your own IP, remember to “CYA”: “Consult Your Attorney”. #NotLegalAdvice

So, in short, the answer to whether this would work is “maybe”. I believe it could work and work well if done right, but I may be missing something that will be obvious to someone else, so let me know if I left in any “wide open back doors” that would prove disastrous and I will retcon.

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com