You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Chapter 41: The Trumpet that Shall Never Call Retreat

The Battle of Lexington, fought in February 1863, was one of the greatest Union successes and one of the few rays of hope between the Peninsula and Union Mills. Through this victory, General George Henry Thomas, immortalized from then on as the “Sledgehammer of Lexington”, was able to expulse Braxton Bragg from Tennessee and proceed to the capture of Chattanooga in April. More importantly, he restored confidence in the Union cause at a time when battlefield reserves, rebel guerrillas and seditious Copperheads almost defeated it. But during the following months, Thomas’ army made no headway into Georgia and did not face Joe E. Johnston’s rebels. This has led many to conceive of the Tennessee theater as an unproductive dead end that pitied two incompetent and timid commanders.

This perception is, needless to say, false. Thomas, despite his nickname of “Old Slow Trot”, was unable, not unwilling, to advance into Georgia due to a host of factors. Chief among them was the extremely difficult terrain of East Tennessee, a factor that had already frustrated many campaigns in the past and that enormously complicated Thomas’ task now. Devoid of infrastructure and roads, and further devastated by continuous guerrilla warfare, the terrain threatened Thomas’ army with nothing less than starvation. There were no supplies to be seized or river or rails that could bring food to hungry soldiers and civilians. Consequently, Thomas had to slow down and gather supplies for several months, this despite irritated demands from the War Department to move before he was forced into winter quarters.

The difficult terrain was joined by an even more difficult political situation. East Tennessee, as one of the mountainous centers of Unionism in the South, was one of the few places where the Union Army was received as liberators not only by Black people, but also by Whites. This did not necessarily imply an end to violence or racial strife, however. Guerrilla bands, led in the West by the ruthless Forrest and in the east by Morgan, continued to terrorize the state. The strategic dimension of this bush war was maintained, as the guerrillas did everything they could to slow down Union movements and logistics, but as the process of Reconstruction started in Tennessee the actions of the guerrillas took in a political dimension as well. Usually seen as the precursors of the Ku Klux Klan and the White League, groups of terrorists (many of them from Georgia or Western Tennessee) engaged in counterrevolutionary terror against Thomas’ army and the state’s Unionists.

Such violence was a direct response to the fears that the military administration led by Parson Brownlow would institute “Negro supremacy and White slavery”. These fears seemed somewhat justified by Brownlow’s radical inclinations, and when the Third Confiscation Act was signed into law, he indeed started to enforce it aggressively and radically. Sharing Stevens and Summer’s idea of Reconstruction as not a mere military pacification but a social revolution, Brownlow started to confiscate land from several prominent rebels and distributing it among the poor White Unionists and the freed slaves. Through confiscation and land distribution, Brownlow said, he would be able to erect “a nation of freedmen” within Tennessee and forever guard the state against “the approach of treason”.

Chattanooga was taken in April, severing one of the East-West communications and logistics paths for the Confederacy

But the Brownlow regime quickly ran into conflict with the local chapter of the Land Bureau, headed by Lincoln appointees who wanted to moderate Brownlow’s policies. To be sure, both Brownlow and the Bureau agreed on confiscating the lands of the leading rebels – no one complained when Forrest’s extensive land holdings were confiscated and redistributed. The Moderates and the Radicals were divided by two main issues: what was to be done with the defeated rebels? And how was the Reconstruction of the state to proceed? Brownlow and the Radicals wanted to limit political participation to “true Union men” and follow an exhaustive Reconstruction that would disenfranchise most rebels and confiscate their lands for the benefit of Unionists both Black and White. The possibility of treason trials was open, with Brownlow famously threatening to have Forrest trialed before “a colored judge and a colored jury” and then hung “by a colored executioner before a colored crowd”.

But the Bureau agents, acting according to Lincoln’s wishes, wanted to allow for the possibility of some “reconstructed rebels” taking part in the new regime and even receiving land in exchange of loyalty. Unlike African Americans and White Unionists, who received land with a secure title, they would be liable to treason trials and confiscation should they engage in further disloyal practices, such as supporting guerrillas. That way, a “perpetual sword of Damocles” would hang over them, forcing them to be loyal in acts if not in mind. Reconstruction, when seen through this prism, was less a social revolution and more a “carrot and stick” political approach. A particularly dogmatic Radical even called it a “dirty bribe”, and some seemed to argue for outright extermination.

Brownlow and his supporters weren’t so extreme, but they refused to compromise on the issue of who was to lead Tennessee’s Reconstruction. Land confiscation, under the auspices of a Federal Bureau and a Federal Army, followed for the most part Lincoln’s guidelines, but the lack of a unified national policy for Southern Reconstruction meant that Brownlow and the Radicals had the advantage within the state. The result was a bitter partisan conflict between Moderate and Radical factions, that constituted a sad prelude to the chronic partisanship that would affect Republican regimes in the post-war South. The result was that, contrary to Lincoln’s aims, the state remained under the rule of a small cradle of Eastern Unionists that seemed unable to agree on the form the laws and constitution of the New Tennessee should take.

Tennessee’s moderate faction had a questionable asset in Andrew Johnson. Though still widely respected as a Union man, Johnson was undoubtedly a virulent racist that exhibited a weird mix of resentment and envy towards the planter class. He had seemingly undergone an incredible change of heart, telling Black Americans that he would be “your Moses . . . and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace.” Such egalitarian messages, alongside fiery declarations that “Treason must be made odious and traitors punished”, gave Johnson a radical reputation within some circles. But, “Time would reveal that Johnson’s Radicalism was cut from a different cloth than that of Northerners who wore the same label”. This was already evident to some, as he chastised Bureau agents for giving lands to “undeserving Negroes” and opposed limited and timid plans to extend the suffrage to African Americans as discrimination against Whites, somehow.

War-time Reconstruction in Tennessee

Johnson’s aptitude is emblematic of many Southern Unionists, who were more concerned with punishing traitors than with elevating the freedmen. Some Unionists demanded that “not a single acre of land” be given to the freedmen, and that political and economic power should be wielded only by “Union men – white Union men”. As such, and even though they supported measures of confiscation and disenfranchisement, most only did so as a way to punish the rebels and showed little concern for freedmen. A short-lived push for an independent East Tennessee had at its center an effort to “build a state for the benefit of the loyal white men”.

Although there were some radicals on the Northern mold, including Brownlow, that supported Black civil rights and even Black suffrage, most Tennesseans seemed to agree that the new, Reconstructed state should be built on the shaky foundation of political disenfranchisement rather than a more stable but certainly revolutionary foundation that included Blacks as part of the body politic. Still, national factors such as the Battle of Union Mills and regional ones like the continuous activities of the guerrillas helped to change the opinions and soften the prejudices of many. Of note is the fact that Black militias would often go into battle alongside White militias, and in the midst of combat they often ended up working as integrated regiments de facto, even if racial segregation in militia units was still required. Some Unionists were even willing to admit the bravery and value of Black troops, and by the end of the year as a policy for Reconstruction started to crystallize at both the state and national level, some had started to push for extending the suffrage to Black veterans.

Thomas remained mostly aloof from these political debates. It seems that, like most Union generals, Thomas was largely apolitical, and considered that the only duties of his military regime were to guarantee the conditions under which the people could trace a new path for the South. Thomas, however, supported the confiscation and land distribution program, saying that the Confederates had “justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations” their land. He was not afraid to use harsh method to deal with the terrorists that swarmed the state, and it was through his decisive military intervention that the worst of the resistance was stamped out. Thomas was, furthermore, impressed enough by Black men’s martial capacity that he included an all-Black corps in the Army of the Cumberland. Nonetheless, guerrilla raids continued as it was simply impossible for the Union to patrol every inch of that enormous expanse.

Despite these achievements, the fact remained that the Army of the Cumberland had done practically nothing since it took Chattanooga in April. Perhaps it’s the fault of Philadelphia bureaucrats that did not understand the intricacies of supply and the necessity for careful planning, but the Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of the Tennessee would not face each other until 1864. Luckily for Thomas, Lincoln was more lenient towards him than he had been towards Sherman and Buell, mainly because unlike them Thomas had accomplished his cherished goal of liberating East Tennessee and starting the Reconstruction of the state. Lincoln also liked Thomas’ unassuming nature, which reminded him of Grant. A less tactful General may have demanded more recognition and lost goodwill in Philadelphia. Lincoln thus declared that “we gave Grant a year and he gave Vicksburg to us . . . we can grant the same privilege to General Thomas, and I’m sure he’ll deliver Atlanta”.

One event that helped Thomas in this regard was a successful and daring cavalry raid led by Col. Abel Streight, an Indiana lumber merchant who had taken part in a brief and unsuccessful experiment to form a mule-mounted cavalry during the Lexington campaign. As advertised the mules did require less forage and were apparently hardier, but they proved slow and unwieldly compared with horses. Streight put this experience to good use, and when he proposed the idea of a raid against Atlanta both Thomas and Lincoln endorsed it. Streight’s raid started a few weeks before Grierson’s more famous raid, leading many to think that this was planned. Others have argued that it was a stroke of luck. In a tactical sense, the raid was a failure, for it didn’t manage to cause much destruction and was quickly chased out of Georgia, but it was an enormous strategic accomplishment. Streight’s raid not only managed to cause panic in Atlanta but also distract Forrest’s cavalry, preventing them from stopping Grierson.

Abel Streight

Despite this success, Lincoln still pushed Thomas to move forward, and he admitted to being “greatly dissatisfied” with Thomas’ lack of activity after Grant had taken Vicksburg and thus seized the spot as his favorite General. “You and your noble army now have the chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion”, he informed the stern Virginian through Secretary Stanton. “Will you neglect the chance?" Finally, after slightly over six months of gathering supplies and fighting guerrillas, Thomas went forward in the last days of November, hoping to seize a position within Georgia before the weather forced into winter quarters. Guerrillas, the weather and the terrain had proven formidable adversaries to Thomas, but many Confederates feared that Joe Johnston would not prove as worthy a foe.

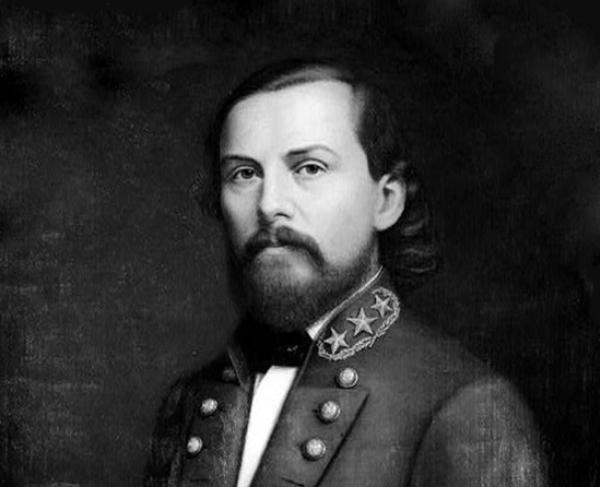

Chief among the doubters was Breckinridge. Johnston had actually never wanted the command of the Army of Tennessee, despite the fact that Generals Leonidas Polk and B. Franklin Cheatham had recommended him for the position after the Lexington disaster. Cheatham had even vowed to never again serve under Bragg. Bragg, for his part, lashed out, threatening to have Cheatham court-martialed and even intimating that the President had been drunk during the campaign and that’s why he had failed to support him adequately. The story goes that Breckinridge was so infuriated by Bragg’s failure and declarations that he almost challenged him to a duel. Ultimately, he simply replaced him with Johnston, who tried to turn down this dubious honor with the feeble excuse that “to remove Bragg while his wife was critically ill would be inhumane.”

This shuffle in command also responded to political realities, for Breckinridge wanted to get rid of Johnston, an unsubtle critic of the administration. Militarily, it seems that Breckinridge and Davis judged that a defensive campaign on defensive terrain would suit the timid Johnston better than the pivotal Virginia front or the highly mobile Mississippi front. These two fronts were trusted to Lee and A.S. Johnston (and after Vicksburg to Cleburne), generals that were esteemed by the President and his circle, something that only increased Joe Johnston’s bitterness. Johnston’s appointment was at first an apparently brilliant choice, and reports that “the army had recovered both its morale and its physical readiness” reached the President’s desk. This news lifted Breckinridge’s sagging spirits, and he soon started to entertain notions of Johnston “restoring the prestige of the Army” and “reoccupying the country”.

Johnston shattered these expectations. He claimed those reports were exaggerated and offered a lengthy list of problems, including the confidence of the army, its artillery, horses and logistics. Breckinridge was dismayed, while Davis darkly said that it was simply impossible to make Johnston fight. Seeking to remedy this, Breckinridge and Davis tried to convince Longstreet to go and serve in the Georgia front, but both he and Lee opposed the idea. The start of a new Virginia campaign finally killed the proposal entirely. Consequently, with Thomas slowed down by factors out of his control and Johnston being unwilling to fight, the Tennessee/Georgia front so no action whatsoever. That’s it, until November 1863 when Thomas finally started moving.

The Union plan was rather uninspiring, involving only a direct southward advance to Dalton. It seems he was hoping to draw Johnston into open battle around the rocky ridges around the town. Informed by partisans, Johnston quickly moved to seize the high terrain, a rather uncharacteristic display of initiative. With Union soldiers looking forward to seeing the “Sledgehammer” slam into Johnston and rebels talking gleefully of how the “Undaunted Johnston” would push Thomas back to the Ohio, the whole affair suddenly seemed like the first stages of a decisive battle. In the night of November 17th, when the temperature started to drop, both armies got into position. Southern bands started to play “Dixie” and “The Bonnie Blue Flag”, making the Union drummers respond by blasting “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “Yankee Doodle”.

The inhospitable Dalton terrain wasn't adequate for a large scale campaign

It turned out that this battle of the bands was the fiercest action that Dalton would see for the moment. Slowed down by guerrillas and unable to maintain the element of surprise, Thomas had been unable to seize the Dalton heights. Prodding assaults resulted in an enormous disparity in casualties, making Thomas reluctant to throw his full force into the fray. His original plan to outflank Johnston through the Snake Creek Gap had failed as a result of the muddy roads, and now that he was faced by the imperfect Dalton plan, Thomas decided that he'd rather execute a perfect plan in Spring 1864 than a flawed one right then. For his part, Johnston newfound nerve evaporated and he prepared to evacuate the position. The result was anti-climax, as both commanders refused to engage and broke off before a true battle had started. “The Battle of Danton” thus has gained a reputation as one of the greatest battles never fought, and a favorite of uchronia enthusiasts. Thomas was then forced to go into winter quarters, producing dismay in Philadelphia and elation in Richmond.

If the Georgia front was disappointingly anti-climactic, the Union saw plenty of action in other fronts that ended up in disappointing climaxes. Both then and now, many have wondered why the Union was not able to give the final blow to the rebellion, when it seemed at its lowest point after of Union Mills and Vicksburg. Lincoln himself wondered what happened, exclaiming that “Our Army held the war in the hollow of their hand & they would not close it.” “There is bad faith somewhere…”, the President concluded, but the Army begged to differ. Many of the high-ranking Eastern general would instead place the blame on Lincoln and his armchair general tendencies. Whatever the true reason, disagreements over strategy and perhaps overambitious plans prevented the Union from ending the rebellion in the later half of 1863.

For the few days that immediately followed Union Mills, it had seemed like the end of the war was at hand. The Army of the Susquehanna had been unable to completely destroy the Army of Northern Virginia, but the rebels had suffered grievous losses of both men and material they could ill afford. The need to put down the Copperhead riots had prevented a prompt pursue, but Lincoln believed that the rebellion could be ended if “General Reynolds completes his work . . . by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee's army”. But despite its appearance as a victorious army, the Army of the Susquehanna had also suffered disastrous losses, and many of its effectives keenly felt the physical and mental strain of several weeks of bloody campaigning. For example, in a letter to his wife, General Meade admitted that “over ten days, I have not changed my clothes, have not had a regular night’s rest . . . and all the time in a great state of mental anxiety.” Many, officers and enlisted men, shared Meade’s exhaustion.

Furthermore, it was then that Lincoln’s first instance of “meddling” took part, as he ordered the troops that had restored order in New York and Baltimore to remain there for the time being. Reynolds objected, wanting to concentrate all his effectives for the next campaign, but Lincoln wanted the military presence to continue until the next draft was completed, in order to assert the supremacy of the government and dissuade similar resistance elsewhere. Privately, Reynolds agreed with those who pleaded with Lincoln to simply suspend the draft, which he argued would be unnecessary if Lee was defeated. Reynolds also balked at what he saw as a sordid use of his soldiers’ sacrifice for the advancement of the Administration’s political aims.

As a consequence of all these delays, the Army of the Susquehanna spent the several next months licking its wounds. Though Lincoln recognized that it wasn’t Reynolds’ fault, he could not help but express bitterly that a “golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasureably because of it”. Nonetheless, “victory was a wondrous tonic for Lincoln”, who regained the optimism and good humor that previous disasters had robbed him. He even found time to play with his children, Tadd and Willie, who had given him a scare the previous winter when they came down with a minor illness. John Nicolay happily wrote some weeks after Union Mills that “the Tycoon is in fine whack. I have rarely seen him more serene & busy. He is managing this war, the draft, foreign relations, and planning a reconstruction of the Union, all at once.”

Lincoln and one of his sons, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln

The war was, naturally, the top priority. Believing that he had finally found generals who would fight and that the time had come to attack the Confederacy from all sides, Lincoln gave his support to several military projects that tried to take advantage of Southern weakness. Charleston thus became one of the premier objectives of the Union alongside Richmond and Atlanta. Capturing “the Citadel of Treason” would not only be enormously significant, but also presumably easy, for the Federals knew that the coastal defenses had been stripped of men in favor of Lee’s army. In fact, efforts to capture this attractive plum had started before Union Mills, but the commander in charge, Samuel Du Pont, was reluctant to attack, and when he finally did so, he failed disastrously and ended with six disabled ironclads.

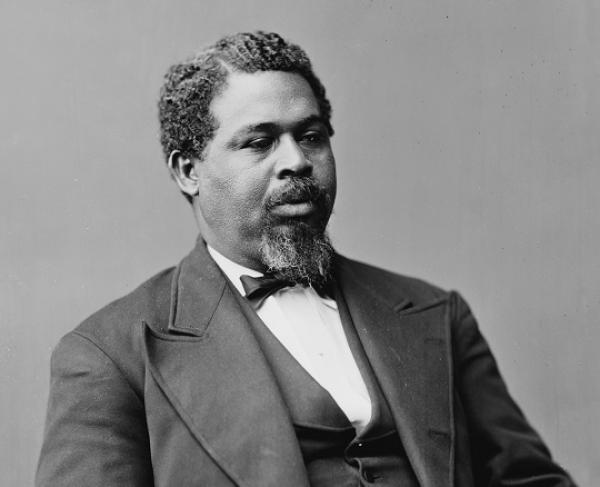

Out of patience, Lincoln replaced Du Pont with John A. Dahlgren, a man of little experience whose only qualification seemed to be his friendship with Lincoln. Dahlgren was decided to subdue the cradle of secession by a combined army-navy operation. Much to Reynolds’ chagrin, the necessary troops were taken from the Army of the Susquehanna. Underscoring the political aims of the campaign was the fact that one of the ships would be piloted by Robert Smalls, a Black man famous for taking over the Confederate ship CSS Planter and escaping Charleston harbor, freeing himself and dozens of slaves. The second attempt to seize Charleston failed as well. Though the Union managed to reduce Fort Sumter to rubble, the landing was mishandled and the flotilla was forced to retreat at the end, having lost several ironclads again.

The failures in Georgia and South Carolina exasperated Lincoln, but the President could at least take some solace in the successes found in Arkansas. That state had been basically left undefended after most of its troops had been transferred towards the east to resist Grant's campaigns against Corinth and then Vicksburg. Arkansas was, the governor declared, "lost, abandoned, subjugated . . . not Arkansas as she entered the confederate government." If help wasn't forecoming, Arkansas wouldn't remain in the Confederacy waiting until it was "desolated as a wilderness". The governor was not exaggerating, for the route to Little Rock was practically open, Samuel R. Curtis' small force advancing to the capital. Only guerrilla combat, that saw the use of Native American troops by both sides, slowed the Union in its march.

To prevent the fall of another Confederate state capital, Breckenridge appointed the diminutive Thomas C. Hindman, a "dynamo only five feet tall". To aid Hindman, Breckinridge suspended the writ of habeas corpus and allowed him to declare martial law, in order to enforce the draft and thus scrape together an Army. Although the morale and readiness of the resulting force was suspect, and the methods employed aroused "howls of protest", Hindman did succeed in getting together more than 20,000 men. Hindman managed to stop Curtis' campaign for the time being in December 1862, though his force was then turned away by the abolitionist Kansan James G. Blunt at the Missouri border. That Hindman had not accomplished more concrete results led to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis recommending his replacement, pointing to his old friend Theophilus Holmes. Since the General did not impress Breckinridge with his performance at the Nine Days, Hindman remained in command.

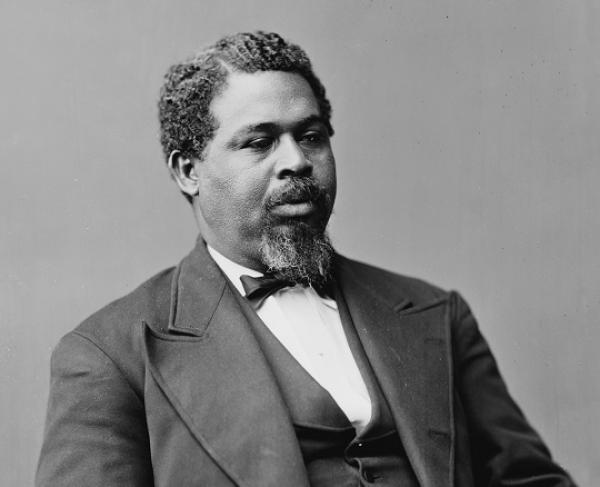

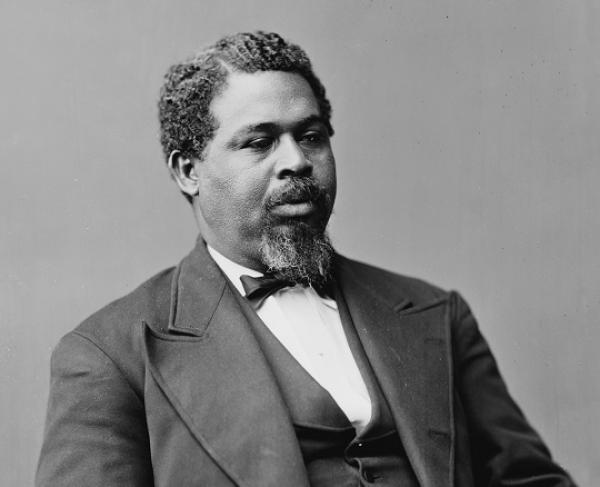

Robert Smalls

The situation in Arkansas seemed to stabilize for the time being, until things started to unravel in the spring of 1863. The critical situation in Vicksburg made Breckinridge order Hindman to send reinforcements to A.S. Johnston, in the hopes of saving the citadel. If Vicksburg fell, Secretary Davis wired Hindman, the enemy "will be then free to concentrate his forces against your Dept.", and even if Hindman did "all that human power can effect, it is not to be expected that you could make either long or successful resistance." To fulfill Breckinridge's orders, Hindman once again acted ruthlessly, executing draft dodgers and forcibly pressing men into service, which created a motley crew of guerrillas, conscripts and militiamen. But when the force found that they would be marched out of Arkansas, they revolted, many declaring openly that they would never leave their state and many others deserting. The governor encouraged this resistance, defiantly telling Breckinridge that Arkansas' soldiers "do not enter the service to maintain the Southern Confederacy alone, but also to protect their property and defend their homes and families".

A brief attempt at enforcement through a declaration of martial law bore no results, and when Hindman finally forced a contingent out of the state the force just melted. The attempt to strongarm Arkansas had backfired enormously, with the soldiers fatally demoralized and all influential Confederates in both Arkansas and Missouri clamoring for Hindman's removal. One bitterly said that Breckinridge was someone "who stubbornly refuses to hear or regard the universal voice of the people.” With Arkansas at the brink of secession, Breckinridge had no choice but to remove Hindman and, at the end, only a few regiments ever joined Johnston's command - just in time, tragically enough, to end up trapped in Vicksburg, where they would surrender to Grant. When the new commander, Sterling Price, reached Little Rock, he found a demoralized and undisciplined Army.

Such an Army was of little use to its commanders, but Price, obsessed with the idea of liberating Missouri from Yankee rule and badly overestimating the strength of the department, decided to take a gamble. The failed attempt to retake Maryland with the help of rebel rioters in Baltimore inspired him to attempt to retake Missouri with the help of St. Louis Copperheads. Marching north with over 10,000 men and hoping that thousands more would flock to his banner, Price seemed to be under the belief that he was leading an occupation force instead of a brief raid. As his force slowly advanced, many guerrillas did indeed join his ranks. But the leisure pace allowed the local Union commander, John M. Schofield, to gather the dispersed militia and troops, and take measures against the seditious rumors that circulated in St. Louis. By the time Price's army reached St. Louis, the city was in a firm Union grip, and the awaited for insurrection didn't happen. It's dubious that it would have materialized anyway, since the ill-conceived expedition had probably misjudged the pro-Confederate sentiment. An attack against the forts only resulted in horrific losses, the fact that Black militia took part only adding insult to injury, and resulting in the battle being known as the "Fort Saratoga of the West". Price finally retreated, his army melting away as guerrillas vanished into the countryside and deserters left by the thousands. But this would not be the last Missouri had seen of him.

This defeat led the road to Little Rock open. Leading "a multiracial force of white, black, and Indian regiments", General Blunt encroached the capital and then captured it in September, 1863. With three quarters of the state now under Union control, a joyful Lincoln ordered his agents to start the Reconstruction of the state, appointing a military governor to rule over the occupied territories. Union control was often tenuous due to guerrilla activity, but the Confederates would never retake the state. A forlorn Breckinridge, for his part, appointed Kirby-Smith as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, informing him through Secretary Davis that he had "full authority . . . to administer to the wants of Your Dept., civil as well as military". The General now was "the head of a semi-independent fiefdom with quasi-dictatorial powers". In the estimation of James McPherson, "Kirby Smith rather than Breckinridge became commander in chief of the Trans-Mississippi theater. For the next two years “Kirby Smith’s Confederacy” fought its own war pretty much independently of what was happening elsewhere."

These successes pleased the Union President, but important as they were, Lincoln's main concern remained the defeat of the Confederacy through the destruction of its main army, the Army of Northern Virginia. If Reynolds accomplished a decisive victory over Lee, the Northern public and Lincoln all believed that the war would be over. Consequently, anxious eyes turned to Virginia, waiting for the next campaign to commence. Though he shared this restlessness, Lincoln didn’t interfere as directly with the Army of the Susquehanna because he knew of Reynolds’ distaste for politics. Still, he impressed upon the General the need to act before winter turned all roads into mud. In response, Reynolds assured the President that he would fight Lee again before the end of the year, declaring the defeat of Lee's Army to be his highest priority. Lincoln agreed completely, and was reportedly overjoyed to have found a general that actually wanted to face Lee instead of angling for Richmond, like McClellan had done, or being reluctant to fight, like Hooker.

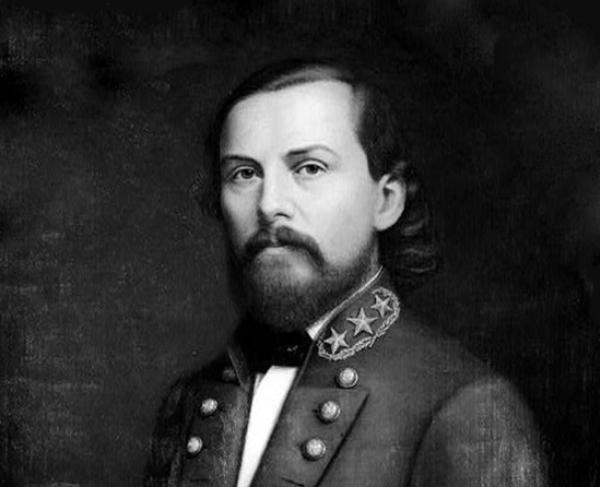

Thomas Carmichael Hindman

Strategically, Reynolds’ top concerns were two: keep the rebel army from seizing the initiative and invading the North again, and drawing Lee into an open battle where his superior numbers would give him the victory. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad was thus chosen because it was the route that covered most of these objectives. Its main advantage was, of course, that it would keep the Army of the Susquehanna between Lee and the North, forcing Lee to face Reynolds and preventing him from attacking the North. It would also allow the Federals to Virginia Central Railroad, depriving Richmond and the Confederate Army of vital supplies from the Shenandoah – a deadly blow at a time when Lee’s army was forced to look for wild onions to ward off scurvy. Unfortunately for the Union, the route was a dead end and a logistical nightmare, making the prospect of an extended campaign against Richmond difficult if not impossible. No matter, said Reynolds, his objective was not Richmond, but Lee’s Army. If Lee’s Army was mauled or destroyed, then Reynolds could change to a more logistically appropriate route at his leisure.

After several months of preparation and healing, the Army of the Susquehanna was ready for battle once again. It had been forced to detach some regiments for other campaigns and return the regiments it had borrowed from Thomas, something that also helps to explain the Virginian’s passivity. But it still retained close to a two to one advantage over the rebels – 110,000 bluecoats would go against 55,000 rebels at most. Doubleday’s USCT corps was of course included, and many now seemed to consider it something of a shock force that “could scare the bejeezus out of the rebels”, as a soldier wrote. “Yes sir, nothing don’t scare a rebel quite like Doubleday’s darkies!” In high spirits and with great trust and loyalty towards their leaders, the Federals advanced with a confidence that had never truly exhibited before.

If the Northerners believed the rebels defeated, they were in for a distressing surprise. Despite their natural plunge in morale following Union Mills, most graybacks were convinced, or rather convinced themselves, that Marse Lee could once again seize victory from the jaws of defeat and carry them to glory and victory. This strong spirit de corps was motivated by a belief that defeat would mean perdition, which made the men "now more fully determined than ever before to sacrifice their lives, if need be, for the invaded soil of their bleeding Country”, as a soldier claimed. Reynolds also had to detach several units to guard his supply lines and pursue the murderous marauders swarmed his rear. The result was that before he had even seen the Army of Northern Virginia, Reynolds’ army had been reduced to some 80,000 effectives. Finally, now that they were on the defensive again, the rebels benefited from their usual advantages: difficult terrain they knew well and a net of couriers and spies that informed them of all Union movements.

Putting these advantages to good use, Lee hid his troops behind the Blue Ridge Mountains as he advanced towards Reynolds’ flanks. True to his nature, Lee had hoped to use surprise and defeat Reynolds, but practical realities soon made him realize that an open battle might result in a complete defeat. So, Lee settled for wrecking the railroad behind Reynolds, something that embarrassed the Union General who had not been able to detect Lee’s movements. Still, and though Lee’s actions delayed him, Reynolds was glad to learn of his position and eager to face him. Continuing his advance to the Rappahannock river, Reynolds was forced to endure continuous guerrilla activity plus harassing at every little stream he had to cross. Nevertheless, he crossed the river on October 15th, reaching Lee’s formidable lines along the Rapidan.

Some of the Union commanders were cowed by these imposing defenses, but Reynolds was undaunted. Refusing to turn back, he vowed to defeat Lee whatever it took. Looking to outflank Lee, he decided to ford the Rapidan to Lee’s right. However, to reach the Mine Run Reynolds would have to march through a dense forest of oaks and pines known as the Wilderness. Even if he managed to cross that “gloomy expanse”, he would then have to face a line along the Mine Run. Again, some commanders, including Reynolds’ friend Meade, were skeptical of their chances and suggested turning back, but Reynolds refused. If they moved quickly enough, the General pointed out, they may be able to overwhelm the rebel corps in the Mine Run and then proceed to bag the rest of Lee’s army. Trusting their commander, the Army of the Susquehanna forded the Rapidan and advanced to the Wilderness.

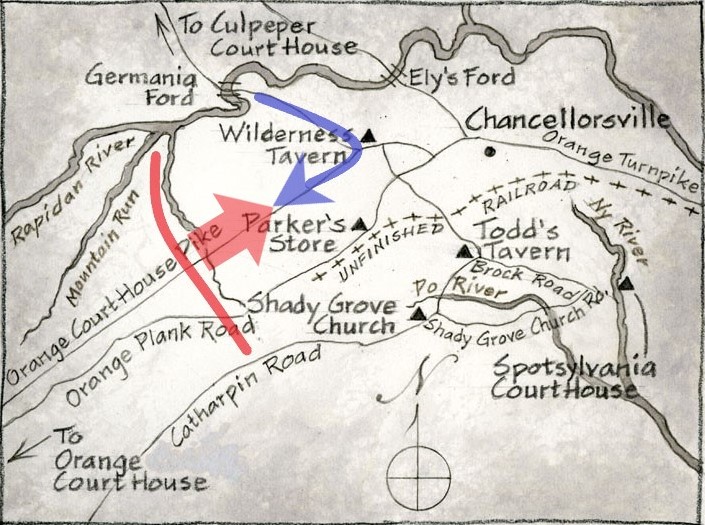

Lee too welcomed the chance of facing Reynolds, though the Pennsylvanian’s decisiveness threw a wrench into his plans. Indeed, Lee had hoped the Federals would vacillate a little longer and that they would not dare assault the Mine Run, which would give him a chance to hit Reynolds’ other flank. When it became apparent that Reynolds was moving to the Wilderness, Lee was forced to change his tactics and quickly ordered troops to the Mine Run, hoping to completely man it, thus making it practically invincible. And so, the first stage of the battle was a race to the Mine Run, one in which the rebels counted with a powerful ally: the Wilderness itself.

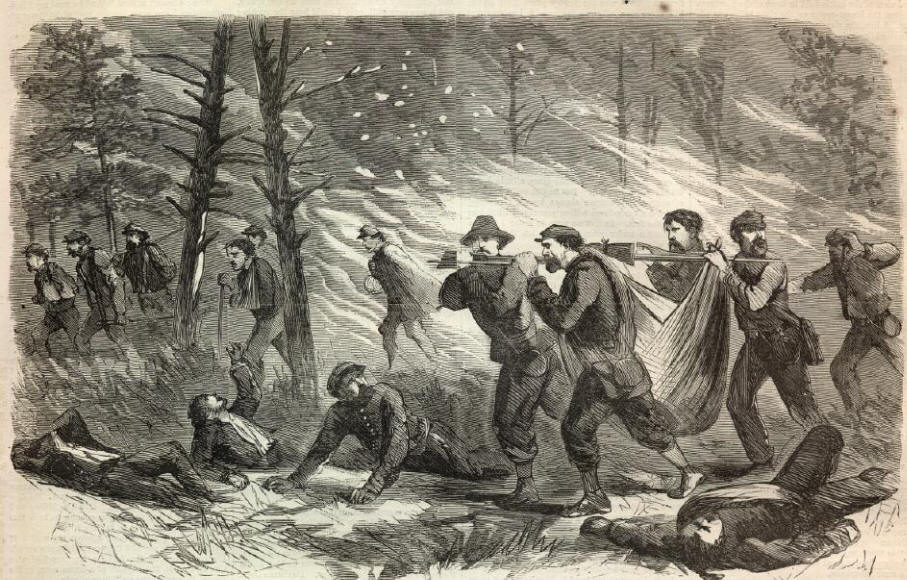

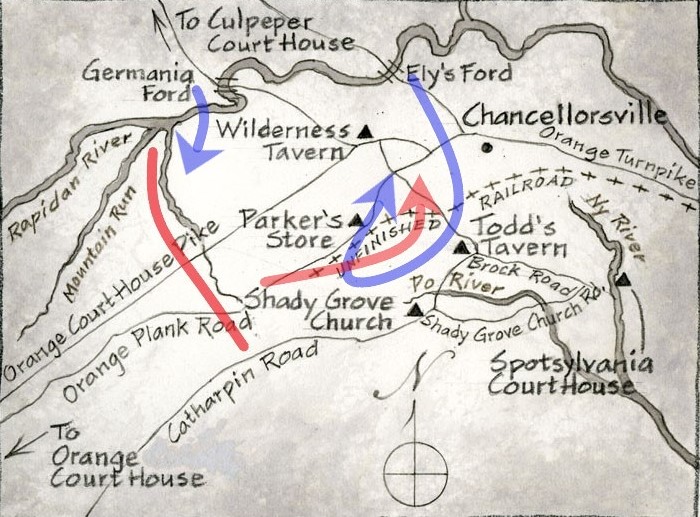

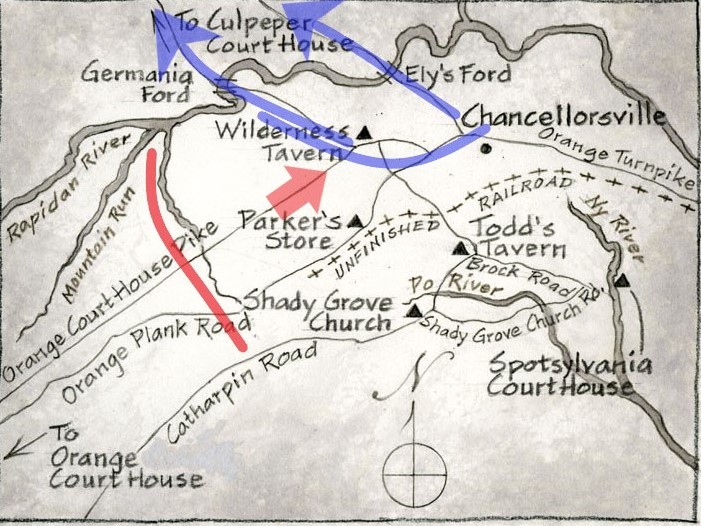

The Wilderness

A “trackless maze” of second-growth trees, the Wilderness slowed down the Union advance, for the Yankees were barely able to navigate it without getting lost. By confusing the Federals and preventing them from using their superior artillery effectively, the Wilderness more than evened the odds. Mindful of these factors, Lee decided to advance into the Wilderness and give battle to “those people”. Of course, the safe option would have been to wait for the Federals at the Mine Run, but Lee wasn’t known for taking the safe option. Maybe he wanted to recoup some of the glory he had lost at Union Mills. In any case, Lee advanced forward with Longstreet and Jackson, silently and unobserved, through secret paths the local residents had shown them. Meanwhile, and after crossing at Germania’s Ford, the Federals had managed to reach the Wilderness Tavern and were now ready to advance along the Orange Turnpike.

That’s when Reynolds’ scouts reported that Lee had been seen near the Orange Turnpike, so immediately decided to seize the chance to hammer Lee. But his bluecoats couldn’t move as fast as the graybacks, who surprised them. The troops quickly unleashed a furious flurry of bullets that produced an ear-shattering noise and covered the forest with thick, acidic smoke. “The steady firing rolled and crackled from end to end of the contending lines as if it would never cease”, commented a Yankee. Reynolds and Lee then poured troops into the engagement, each hoping to gain the upper hand over their adversary. Winfield Scott Hancock’s men were the first to reach the battlefield, and they hit the rebels with such fury that they staggered back and seemingly retreated. “We are driving them, sir!”, happily exclaimed Hancock. “Tell General Reynolds we are driving them most beautifully.”

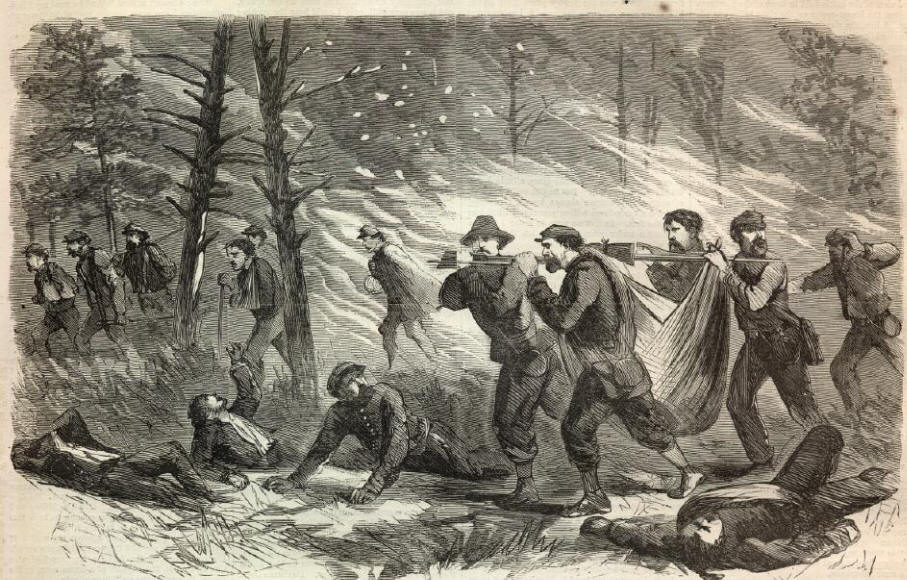

But in their excitement the Yankees pushed too far, apparently forgetting that the rebels had reinforcements too. Indeed, when they broke into a clearing, they found Longstreet’s troops waiting for them, ready to counterattack. And counterattack they did, with furious rebel yells and an unrelenting charge that pushed Hancock back to his starting position. Neither army was able to retake the offensive after that, because exploding shells and roaring artillery had lit the Wilderness in fire. The flames soon consumed the earthworks of both sides, creating a “roaring inferno” that terribly increased the suffering of the soldiers. Sickening, traumatic scenes took place as “Wounded men . . . roasted alive on the forest floor, their agonized cries audible everywhere; many committed suicide rather than burn to death”.

Recognizing that section of the Wilderness as a deadly trap, Reynolds pulled back and started to look for another venue for attack. Almost giving into his instincts, Reynolds at first insisted on leading the next charge himself, but he fortunately then rejected the idea and instead asked Doubleday’s fresh troops to spearhead the advance towards the Orange Plank Road. Unfortunately, the rebels were able to detect the movement. Identifying his old foe and eager for a rematch, Jackson asked to lead a night attack against Doubleday. Guided by a soldier who knew of an old track that had been used to move charcoal, Jackson’s soldiers advanced. Then, as they walked through the path they ran into Doubleday’s men, who apparently were just as surprised to find them there. A battle then started once the troops got over their confusion.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/battle-of-the-wilderness-large-56a61bd05f9b58b7d0dff4a2.png)

The Battle of Mine Run

What had happened? Turns out that one of Doubleday’s soldiers was a former Virginia slave who had once helped haul coal through that path, and he had suggested to use it to surprise the rebels and seize the Orange Plank. The USCT and the Stonewall Brigade now faced each other for the second time. But this time, the advantage was on the rebel side, though the Black soldiers made sure to make the rebels pay for every meter they took. Reynolds and Lee promptly became aware of the extent of the battle, but Longstreet was faster and the USCT was finally pushed out. An attempt to follow this by an assault failed when the Southern troops were massacred by Union artillery fired from Hazel Groove – the only place within the Wilderness where artillery was effective.

Thus ended the second day of the Battle of Mine Run. At the same time as the Wilderness drama, a second column led by Generals Sedgwick and French was unable to overtake the rebel position at Tom Morris House, though they got closer to the Mine Run than the main column had managed. The third day was marked by smaller scale battles as Reynolds debated whether he should retreat. He had half a mind to turn south toward Spotsylvania, thus escaping the Wilderness and arriving to another route through which he could reach the Mine Run. But even if he succeeded in this endeavor, it was doubtful that his exhausted and bloodied troops would be able to carry the rebel line. Moreover, he had spent almost all his supplies – and the logistical inadequacy of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad meant that he couldn’t bring any more.

Several of his generals recommended retreating and trying again through another route that would allow them to face Lee in more favorable terrain. Swayed by their advice, and preoccupied by the health of his weary troops, Reynolds started to retreat. Lee did try a final attack at the Wilderness Tavern, but it was repulsed, and afterwards the Yankees crossed the Rapidan, reunited, and then retreated to winter quarters at Brandy Station. Recognizing the sorry state of his troops, Lee refused to pursue, and campaigning in Virginia came to an end for 1863. This decision to break off combat, seemingly out of mutual consent, was uncharacteristic for these two aggressive generals, but maybe it can be explained by the simply unspeakable nature of the carnage. Reviewing the battle, Secretary Stanton declared it “the bloodiest swath ever made on this globe”, while Reynolds declared that “more desperate fighting has not been witnessed on this continent.”

If Union Mills was war at its most glorious, Mine Run was war at its bloodiest and ugliest form. The Union suffered around 23,000 casualties, while the rebels suffered 17,000. Many of these men had died incinerated or in brutal, terrifying fighting, leading many to suspect that the simple shock of this kind of warfare was what forced the commanders to end the battle. Despite this bloodshed, the Battle of Mine Run was inconclusive and had seemingly accomplished nothing except deaths and wounds both psychological and physical. Being a failure for both sides, it caused neither elation nor despair, only bitterness and disappointment. At the end of the day, and despite its reputation as one of the bloodiest and most terrible battles of the war, Mine Run had no great strategic or political consequences.

Burning woods at the Wilderness

And thus ended the military campaigns of 1863, which seemed downright anti-climatic taking into account the dramatic and emblematic campaigns of the first half of the year. Small victories and the repulsion of Reynolds had managed to restore a little of the rebels’ confidence, and many within the Union could not help feeling bitter as they realized that the war would still rage on. But in spite of this, the prevailing mood was still confidence and optimism in the North, and quiet despair in the South, something that the fall elections of 1863 in both sections would prove. These elections, maybe more important than the 1862 midterms, would be the most astounding sign of the deep divisions that affected the Confederacy. They would also represent the start of a true policy of Reconstruction for the North.

This perception is, needless to say, false. Thomas, despite his nickname of “Old Slow Trot”, was unable, not unwilling, to advance into Georgia due to a host of factors. Chief among them was the extremely difficult terrain of East Tennessee, a factor that had already frustrated many campaigns in the past and that enormously complicated Thomas’ task now. Devoid of infrastructure and roads, and further devastated by continuous guerrilla warfare, the terrain threatened Thomas’ army with nothing less than starvation. There were no supplies to be seized or river or rails that could bring food to hungry soldiers and civilians. Consequently, Thomas had to slow down and gather supplies for several months, this despite irritated demands from the War Department to move before he was forced into winter quarters.

The difficult terrain was joined by an even more difficult political situation. East Tennessee, as one of the mountainous centers of Unionism in the South, was one of the few places where the Union Army was received as liberators not only by Black people, but also by Whites. This did not necessarily imply an end to violence or racial strife, however. Guerrilla bands, led in the West by the ruthless Forrest and in the east by Morgan, continued to terrorize the state. The strategic dimension of this bush war was maintained, as the guerrillas did everything they could to slow down Union movements and logistics, but as the process of Reconstruction started in Tennessee the actions of the guerrillas took in a political dimension as well. Usually seen as the precursors of the Ku Klux Klan and the White League, groups of terrorists (many of them from Georgia or Western Tennessee) engaged in counterrevolutionary terror against Thomas’ army and the state’s Unionists.

Such violence was a direct response to the fears that the military administration led by Parson Brownlow would institute “Negro supremacy and White slavery”. These fears seemed somewhat justified by Brownlow’s radical inclinations, and when the Third Confiscation Act was signed into law, he indeed started to enforce it aggressively and radically. Sharing Stevens and Summer’s idea of Reconstruction as not a mere military pacification but a social revolution, Brownlow started to confiscate land from several prominent rebels and distributing it among the poor White Unionists and the freed slaves. Through confiscation and land distribution, Brownlow said, he would be able to erect “a nation of freedmen” within Tennessee and forever guard the state against “the approach of treason”.

Chattanooga was taken in April, severing one of the East-West communications and logistics paths for the Confederacy

But the Brownlow regime quickly ran into conflict with the local chapter of the Land Bureau, headed by Lincoln appointees who wanted to moderate Brownlow’s policies. To be sure, both Brownlow and the Bureau agreed on confiscating the lands of the leading rebels – no one complained when Forrest’s extensive land holdings were confiscated and redistributed. The Moderates and the Radicals were divided by two main issues: what was to be done with the defeated rebels? And how was the Reconstruction of the state to proceed? Brownlow and the Radicals wanted to limit political participation to “true Union men” and follow an exhaustive Reconstruction that would disenfranchise most rebels and confiscate their lands for the benefit of Unionists both Black and White. The possibility of treason trials was open, with Brownlow famously threatening to have Forrest trialed before “a colored judge and a colored jury” and then hung “by a colored executioner before a colored crowd”.

But the Bureau agents, acting according to Lincoln’s wishes, wanted to allow for the possibility of some “reconstructed rebels” taking part in the new regime and even receiving land in exchange of loyalty. Unlike African Americans and White Unionists, who received land with a secure title, they would be liable to treason trials and confiscation should they engage in further disloyal practices, such as supporting guerrillas. That way, a “perpetual sword of Damocles” would hang over them, forcing them to be loyal in acts if not in mind. Reconstruction, when seen through this prism, was less a social revolution and more a “carrot and stick” political approach. A particularly dogmatic Radical even called it a “dirty bribe”, and some seemed to argue for outright extermination.

Brownlow and his supporters weren’t so extreme, but they refused to compromise on the issue of who was to lead Tennessee’s Reconstruction. Land confiscation, under the auspices of a Federal Bureau and a Federal Army, followed for the most part Lincoln’s guidelines, but the lack of a unified national policy for Southern Reconstruction meant that Brownlow and the Radicals had the advantage within the state. The result was a bitter partisan conflict between Moderate and Radical factions, that constituted a sad prelude to the chronic partisanship that would affect Republican regimes in the post-war South. The result was that, contrary to Lincoln’s aims, the state remained under the rule of a small cradle of Eastern Unionists that seemed unable to agree on the form the laws and constitution of the New Tennessee should take.

Tennessee’s moderate faction had a questionable asset in Andrew Johnson. Though still widely respected as a Union man, Johnson was undoubtedly a virulent racist that exhibited a weird mix of resentment and envy towards the planter class. He had seemingly undergone an incredible change of heart, telling Black Americans that he would be “your Moses . . . and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace.” Such egalitarian messages, alongside fiery declarations that “Treason must be made odious and traitors punished”, gave Johnson a radical reputation within some circles. But, “Time would reveal that Johnson’s Radicalism was cut from a different cloth than that of Northerners who wore the same label”. This was already evident to some, as he chastised Bureau agents for giving lands to “undeserving Negroes” and opposed limited and timid plans to extend the suffrage to African Americans as discrimination against Whites, somehow.

War-time Reconstruction in Tennessee

Johnson’s aptitude is emblematic of many Southern Unionists, who were more concerned with punishing traitors than with elevating the freedmen. Some Unionists demanded that “not a single acre of land” be given to the freedmen, and that political and economic power should be wielded only by “Union men – white Union men”. As such, and even though they supported measures of confiscation and disenfranchisement, most only did so as a way to punish the rebels and showed little concern for freedmen. A short-lived push for an independent East Tennessee had at its center an effort to “build a state for the benefit of the loyal white men”.

Although there were some radicals on the Northern mold, including Brownlow, that supported Black civil rights and even Black suffrage, most Tennesseans seemed to agree that the new, Reconstructed state should be built on the shaky foundation of political disenfranchisement rather than a more stable but certainly revolutionary foundation that included Blacks as part of the body politic. Still, national factors such as the Battle of Union Mills and regional ones like the continuous activities of the guerrillas helped to change the opinions and soften the prejudices of many. Of note is the fact that Black militias would often go into battle alongside White militias, and in the midst of combat they often ended up working as integrated regiments de facto, even if racial segregation in militia units was still required. Some Unionists were even willing to admit the bravery and value of Black troops, and by the end of the year as a policy for Reconstruction started to crystallize at both the state and national level, some had started to push for extending the suffrage to Black veterans.

Thomas remained mostly aloof from these political debates. It seems that, like most Union generals, Thomas was largely apolitical, and considered that the only duties of his military regime were to guarantee the conditions under which the people could trace a new path for the South. Thomas, however, supported the confiscation and land distribution program, saying that the Confederates had “justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations” their land. He was not afraid to use harsh method to deal with the terrorists that swarmed the state, and it was through his decisive military intervention that the worst of the resistance was stamped out. Thomas was, furthermore, impressed enough by Black men’s martial capacity that he included an all-Black corps in the Army of the Cumberland. Nonetheless, guerrilla raids continued as it was simply impossible for the Union to patrol every inch of that enormous expanse.

Despite these achievements, the fact remained that the Army of the Cumberland had done practically nothing since it took Chattanooga in April. Perhaps it’s the fault of Philadelphia bureaucrats that did not understand the intricacies of supply and the necessity for careful planning, but the Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of the Tennessee would not face each other until 1864. Luckily for Thomas, Lincoln was more lenient towards him than he had been towards Sherman and Buell, mainly because unlike them Thomas had accomplished his cherished goal of liberating East Tennessee and starting the Reconstruction of the state. Lincoln also liked Thomas’ unassuming nature, which reminded him of Grant. A less tactful General may have demanded more recognition and lost goodwill in Philadelphia. Lincoln thus declared that “we gave Grant a year and he gave Vicksburg to us . . . we can grant the same privilege to General Thomas, and I’m sure he’ll deliver Atlanta”.

One event that helped Thomas in this regard was a successful and daring cavalry raid led by Col. Abel Streight, an Indiana lumber merchant who had taken part in a brief and unsuccessful experiment to form a mule-mounted cavalry during the Lexington campaign. As advertised the mules did require less forage and were apparently hardier, but they proved slow and unwieldly compared with horses. Streight put this experience to good use, and when he proposed the idea of a raid against Atlanta both Thomas and Lincoln endorsed it. Streight’s raid started a few weeks before Grierson’s more famous raid, leading many to think that this was planned. Others have argued that it was a stroke of luck. In a tactical sense, the raid was a failure, for it didn’t manage to cause much destruction and was quickly chased out of Georgia, but it was an enormous strategic accomplishment. Streight’s raid not only managed to cause panic in Atlanta but also distract Forrest’s cavalry, preventing them from stopping Grierson.

Abel Streight

Despite this success, Lincoln still pushed Thomas to move forward, and he admitted to being “greatly dissatisfied” with Thomas’ lack of activity after Grant had taken Vicksburg and thus seized the spot as his favorite General. “You and your noble army now have the chance to give the finishing blow to the rebellion”, he informed the stern Virginian through Secretary Stanton. “Will you neglect the chance?" Finally, after slightly over six months of gathering supplies and fighting guerrillas, Thomas went forward in the last days of November, hoping to seize a position within Georgia before the weather forced into winter quarters. Guerrillas, the weather and the terrain had proven formidable adversaries to Thomas, but many Confederates feared that Joe Johnston would not prove as worthy a foe.

Chief among the doubters was Breckinridge. Johnston had actually never wanted the command of the Army of Tennessee, despite the fact that Generals Leonidas Polk and B. Franklin Cheatham had recommended him for the position after the Lexington disaster. Cheatham had even vowed to never again serve under Bragg. Bragg, for his part, lashed out, threatening to have Cheatham court-martialed and even intimating that the President had been drunk during the campaign and that’s why he had failed to support him adequately. The story goes that Breckinridge was so infuriated by Bragg’s failure and declarations that he almost challenged him to a duel. Ultimately, he simply replaced him with Johnston, who tried to turn down this dubious honor with the feeble excuse that “to remove Bragg while his wife was critically ill would be inhumane.”

This shuffle in command also responded to political realities, for Breckinridge wanted to get rid of Johnston, an unsubtle critic of the administration. Militarily, it seems that Breckinridge and Davis judged that a defensive campaign on defensive terrain would suit the timid Johnston better than the pivotal Virginia front or the highly mobile Mississippi front. These two fronts were trusted to Lee and A.S. Johnston (and after Vicksburg to Cleburne), generals that were esteemed by the President and his circle, something that only increased Joe Johnston’s bitterness. Johnston’s appointment was at first an apparently brilliant choice, and reports that “the army had recovered both its morale and its physical readiness” reached the President’s desk. This news lifted Breckinridge’s sagging spirits, and he soon started to entertain notions of Johnston “restoring the prestige of the Army” and “reoccupying the country”.

Johnston shattered these expectations. He claimed those reports were exaggerated and offered a lengthy list of problems, including the confidence of the army, its artillery, horses and logistics. Breckinridge was dismayed, while Davis darkly said that it was simply impossible to make Johnston fight. Seeking to remedy this, Breckinridge and Davis tried to convince Longstreet to go and serve in the Georgia front, but both he and Lee opposed the idea. The start of a new Virginia campaign finally killed the proposal entirely. Consequently, with Thomas slowed down by factors out of his control and Johnston being unwilling to fight, the Tennessee/Georgia front so no action whatsoever. That’s it, until November 1863 when Thomas finally started moving.

The Union plan was rather uninspiring, involving only a direct southward advance to Dalton. It seems he was hoping to draw Johnston into open battle around the rocky ridges around the town. Informed by partisans, Johnston quickly moved to seize the high terrain, a rather uncharacteristic display of initiative. With Union soldiers looking forward to seeing the “Sledgehammer” slam into Johnston and rebels talking gleefully of how the “Undaunted Johnston” would push Thomas back to the Ohio, the whole affair suddenly seemed like the first stages of a decisive battle. In the night of November 17th, when the temperature started to drop, both armies got into position. Southern bands started to play “Dixie” and “The Bonnie Blue Flag”, making the Union drummers respond by blasting “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “Yankee Doodle”.

The inhospitable Dalton terrain wasn't adequate for a large scale campaign

It turned out that this battle of the bands was the fiercest action that Dalton would see for the moment. Slowed down by guerrillas and unable to maintain the element of surprise, Thomas had been unable to seize the Dalton heights. Prodding assaults resulted in an enormous disparity in casualties, making Thomas reluctant to throw his full force into the fray. His original plan to outflank Johnston through the Snake Creek Gap had failed as a result of the muddy roads, and now that he was faced by the imperfect Dalton plan, Thomas decided that he'd rather execute a perfect plan in Spring 1864 than a flawed one right then. For his part, Johnston newfound nerve evaporated and he prepared to evacuate the position. The result was anti-climax, as both commanders refused to engage and broke off before a true battle had started. “The Battle of Danton” thus has gained a reputation as one of the greatest battles never fought, and a favorite of uchronia enthusiasts. Thomas was then forced to go into winter quarters, producing dismay in Philadelphia and elation in Richmond.

If the Georgia front was disappointingly anti-climactic, the Union saw plenty of action in other fronts that ended up in disappointing climaxes. Both then and now, many have wondered why the Union was not able to give the final blow to the rebellion, when it seemed at its lowest point after of Union Mills and Vicksburg. Lincoln himself wondered what happened, exclaiming that “Our Army held the war in the hollow of their hand & they would not close it.” “There is bad faith somewhere…”, the President concluded, but the Army begged to differ. Many of the high-ranking Eastern general would instead place the blame on Lincoln and his armchair general tendencies. Whatever the true reason, disagreements over strategy and perhaps overambitious plans prevented the Union from ending the rebellion in the later half of 1863.

For the few days that immediately followed Union Mills, it had seemed like the end of the war was at hand. The Army of the Susquehanna had been unable to completely destroy the Army of Northern Virginia, but the rebels had suffered grievous losses of both men and material they could ill afford. The need to put down the Copperhead riots had prevented a prompt pursue, but Lincoln believed that the rebellion could be ended if “General Reynolds completes his work . . . by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee's army”. But despite its appearance as a victorious army, the Army of the Susquehanna had also suffered disastrous losses, and many of its effectives keenly felt the physical and mental strain of several weeks of bloody campaigning. For example, in a letter to his wife, General Meade admitted that “over ten days, I have not changed my clothes, have not had a regular night’s rest . . . and all the time in a great state of mental anxiety.” Many, officers and enlisted men, shared Meade’s exhaustion.

Furthermore, it was then that Lincoln’s first instance of “meddling” took part, as he ordered the troops that had restored order in New York and Baltimore to remain there for the time being. Reynolds objected, wanting to concentrate all his effectives for the next campaign, but Lincoln wanted the military presence to continue until the next draft was completed, in order to assert the supremacy of the government and dissuade similar resistance elsewhere. Privately, Reynolds agreed with those who pleaded with Lincoln to simply suspend the draft, which he argued would be unnecessary if Lee was defeated. Reynolds also balked at what he saw as a sordid use of his soldiers’ sacrifice for the advancement of the Administration’s political aims.

As a consequence of all these delays, the Army of the Susquehanna spent the several next months licking its wounds. Though Lincoln recognized that it wasn’t Reynolds’ fault, he could not help but express bitterly that a “golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasureably because of it”. Nonetheless, “victory was a wondrous tonic for Lincoln”, who regained the optimism and good humor that previous disasters had robbed him. He even found time to play with his children, Tadd and Willie, who had given him a scare the previous winter when they came down with a minor illness. John Nicolay happily wrote some weeks after Union Mills that “the Tycoon is in fine whack. I have rarely seen him more serene & busy. He is managing this war, the draft, foreign relations, and planning a reconstruction of the Union, all at once.”

Lincoln and one of his sons, Thomas "Tad" Lincoln

The war was, naturally, the top priority. Believing that he had finally found generals who would fight and that the time had come to attack the Confederacy from all sides, Lincoln gave his support to several military projects that tried to take advantage of Southern weakness. Charleston thus became one of the premier objectives of the Union alongside Richmond and Atlanta. Capturing “the Citadel of Treason” would not only be enormously significant, but also presumably easy, for the Federals knew that the coastal defenses had been stripped of men in favor of Lee’s army. In fact, efforts to capture this attractive plum had started before Union Mills, but the commander in charge, Samuel Du Pont, was reluctant to attack, and when he finally did so, he failed disastrously and ended with six disabled ironclads.

Out of patience, Lincoln replaced Du Pont with John A. Dahlgren, a man of little experience whose only qualification seemed to be his friendship with Lincoln. Dahlgren was decided to subdue the cradle of secession by a combined army-navy operation. Much to Reynolds’ chagrin, the necessary troops were taken from the Army of the Susquehanna. Underscoring the political aims of the campaign was the fact that one of the ships would be piloted by Robert Smalls, a Black man famous for taking over the Confederate ship CSS Planter and escaping Charleston harbor, freeing himself and dozens of slaves. The second attempt to seize Charleston failed as well. Though the Union managed to reduce Fort Sumter to rubble, the landing was mishandled and the flotilla was forced to retreat at the end, having lost several ironclads again.

The failures in Georgia and South Carolina exasperated Lincoln, but the President could at least take some solace in the successes found in Arkansas. That state had been basically left undefended after most of its troops had been transferred towards the east to resist Grant's campaigns against Corinth and then Vicksburg. Arkansas was, the governor declared, "lost, abandoned, subjugated . . . not Arkansas as she entered the confederate government." If help wasn't forecoming, Arkansas wouldn't remain in the Confederacy waiting until it was "desolated as a wilderness". The governor was not exaggerating, for the route to Little Rock was practically open, Samuel R. Curtis' small force advancing to the capital. Only guerrilla combat, that saw the use of Native American troops by both sides, slowed the Union in its march.

To prevent the fall of another Confederate state capital, Breckenridge appointed the diminutive Thomas C. Hindman, a "dynamo only five feet tall". To aid Hindman, Breckinridge suspended the writ of habeas corpus and allowed him to declare martial law, in order to enforce the draft and thus scrape together an Army. Although the morale and readiness of the resulting force was suspect, and the methods employed aroused "howls of protest", Hindman did succeed in getting together more than 20,000 men. Hindman managed to stop Curtis' campaign for the time being in December 1862, though his force was then turned away by the abolitionist Kansan James G. Blunt at the Missouri border. That Hindman had not accomplished more concrete results led to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis recommending his replacement, pointing to his old friend Theophilus Holmes. Since the General did not impress Breckinridge with his performance at the Nine Days, Hindman remained in command.

Robert Smalls

The situation in Arkansas seemed to stabilize for the time being, until things started to unravel in the spring of 1863. The critical situation in Vicksburg made Breckinridge order Hindman to send reinforcements to A.S. Johnston, in the hopes of saving the citadel. If Vicksburg fell, Secretary Davis wired Hindman, the enemy "will be then free to concentrate his forces against your Dept.", and even if Hindman did "all that human power can effect, it is not to be expected that you could make either long or successful resistance." To fulfill Breckinridge's orders, Hindman once again acted ruthlessly, executing draft dodgers and forcibly pressing men into service, which created a motley crew of guerrillas, conscripts and militiamen. But when the force found that they would be marched out of Arkansas, they revolted, many declaring openly that they would never leave their state and many others deserting. The governor encouraged this resistance, defiantly telling Breckinridge that Arkansas' soldiers "do not enter the service to maintain the Southern Confederacy alone, but also to protect their property and defend their homes and families".

A brief attempt at enforcement through a declaration of martial law bore no results, and when Hindman finally forced a contingent out of the state the force just melted. The attempt to strongarm Arkansas had backfired enormously, with the soldiers fatally demoralized and all influential Confederates in both Arkansas and Missouri clamoring for Hindman's removal. One bitterly said that Breckinridge was someone "who stubbornly refuses to hear or regard the universal voice of the people.” With Arkansas at the brink of secession, Breckinridge had no choice but to remove Hindman and, at the end, only a few regiments ever joined Johnston's command - just in time, tragically enough, to end up trapped in Vicksburg, where they would surrender to Grant. When the new commander, Sterling Price, reached Little Rock, he found a demoralized and undisciplined Army.

Such an Army was of little use to its commanders, but Price, obsessed with the idea of liberating Missouri from Yankee rule and badly overestimating the strength of the department, decided to take a gamble. The failed attempt to retake Maryland with the help of rebel rioters in Baltimore inspired him to attempt to retake Missouri with the help of St. Louis Copperheads. Marching north with over 10,000 men and hoping that thousands more would flock to his banner, Price seemed to be under the belief that he was leading an occupation force instead of a brief raid. As his force slowly advanced, many guerrillas did indeed join his ranks. But the leisure pace allowed the local Union commander, John M. Schofield, to gather the dispersed militia and troops, and take measures against the seditious rumors that circulated in St. Louis. By the time Price's army reached St. Louis, the city was in a firm Union grip, and the awaited for insurrection didn't happen. It's dubious that it would have materialized anyway, since the ill-conceived expedition had probably misjudged the pro-Confederate sentiment. An attack against the forts only resulted in horrific losses, the fact that Black militia took part only adding insult to injury, and resulting in the battle being known as the "Fort Saratoga of the West". Price finally retreated, his army melting away as guerrillas vanished into the countryside and deserters left by the thousands. But this would not be the last Missouri had seen of him.

This defeat led the road to Little Rock open. Leading "a multiracial force of white, black, and Indian regiments", General Blunt encroached the capital and then captured it in September, 1863. With three quarters of the state now under Union control, a joyful Lincoln ordered his agents to start the Reconstruction of the state, appointing a military governor to rule over the occupied territories. Union control was often tenuous due to guerrilla activity, but the Confederates would never retake the state. A forlorn Breckinridge, for his part, appointed Kirby-Smith as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, informing him through Secretary Davis that he had "full authority . . . to administer to the wants of Your Dept., civil as well as military". The General now was "the head of a semi-independent fiefdom with quasi-dictatorial powers". In the estimation of James McPherson, "Kirby Smith rather than Breckinridge became commander in chief of the Trans-Mississippi theater. For the next two years “Kirby Smith’s Confederacy” fought its own war pretty much independently of what was happening elsewhere."

These successes pleased the Union President, but important as they were, Lincoln's main concern remained the defeat of the Confederacy through the destruction of its main army, the Army of Northern Virginia. If Reynolds accomplished a decisive victory over Lee, the Northern public and Lincoln all believed that the war would be over. Consequently, anxious eyes turned to Virginia, waiting for the next campaign to commence. Though he shared this restlessness, Lincoln didn’t interfere as directly with the Army of the Susquehanna because he knew of Reynolds’ distaste for politics. Still, he impressed upon the General the need to act before winter turned all roads into mud. In response, Reynolds assured the President that he would fight Lee again before the end of the year, declaring the defeat of Lee's Army to be his highest priority. Lincoln agreed completely, and was reportedly overjoyed to have found a general that actually wanted to face Lee instead of angling for Richmond, like McClellan had done, or being reluctant to fight, like Hooker.

Thomas Carmichael Hindman

Strategically, Reynolds’ top concerns were two: keep the rebel army from seizing the initiative and invading the North again, and drawing Lee into an open battle where his superior numbers would give him the victory. The Orange and Alexandria Railroad was thus chosen because it was the route that covered most of these objectives. Its main advantage was, of course, that it would keep the Army of the Susquehanna between Lee and the North, forcing Lee to face Reynolds and preventing him from attacking the North. It would also allow the Federals to Virginia Central Railroad, depriving Richmond and the Confederate Army of vital supplies from the Shenandoah – a deadly blow at a time when Lee’s army was forced to look for wild onions to ward off scurvy. Unfortunately for the Union, the route was a dead end and a logistical nightmare, making the prospect of an extended campaign against Richmond difficult if not impossible. No matter, said Reynolds, his objective was not Richmond, but Lee’s Army. If Lee’s Army was mauled or destroyed, then Reynolds could change to a more logistically appropriate route at his leisure.

After several months of preparation and healing, the Army of the Susquehanna was ready for battle once again. It had been forced to detach some regiments for other campaigns and return the regiments it had borrowed from Thomas, something that also helps to explain the Virginian’s passivity. But it still retained close to a two to one advantage over the rebels – 110,000 bluecoats would go against 55,000 rebels at most. Doubleday’s USCT corps was of course included, and many now seemed to consider it something of a shock force that “could scare the bejeezus out of the rebels”, as a soldier wrote. “Yes sir, nothing don’t scare a rebel quite like Doubleday’s darkies!” In high spirits and with great trust and loyalty towards their leaders, the Federals advanced with a confidence that had never truly exhibited before.

If the Northerners believed the rebels defeated, they were in for a distressing surprise. Despite their natural plunge in morale following Union Mills, most graybacks were convinced, or rather convinced themselves, that Marse Lee could once again seize victory from the jaws of defeat and carry them to glory and victory. This strong spirit de corps was motivated by a belief that defeat would mean perdition, which made the men "now more fully determined than ever before to sacrifice their lives, if need be, for the invaded soil of their bleeding Country”, as a soldier claimed. Reynolds also had to detach several units to guard his supply lines and pursue the murderous marauders swarmed his rear. The result was that before he had even seen the Army of Northern Virginia, Reynolds’ army had been reduced to some 80,000 effectives. Finally, now that they were on the defensive again, the rebels benefited from their usual advantages: difficult terrain they knew well and a net of couriers and spies that informed them of all Union movements.

Putting these advantages to good use, Lee hid his troops behind the Blue Ridge Mountains as he advanced towards Reynolds’ flanks. True to his nature, Lee had hoped to use surprise and defeat Reynolds, but practical realities soon made him realize that an open battle might result in a complete defeat. So, Lee settled for wrecking the railroad behind Reynolds, something that embarrassed the Union General who had not been able to detect Lee’s movements. Still, and though Lee’s actions delayed him, Reynolds was glad to learn of his position and eager to face him. Continuing his advance to the Rappahannock river, Reynolds was forced to endure continuous guerrilla activity plus harassing at every little stream he had to cross. Nevertheless, he crossed the river on October 15th, reaching Lee’s formidable lines along the Rapidan.

Some of the Union commanders were cowed by these imposing defenses, but Reynolds was undaunted. Refusing to turn back, he vowed to defeat Lee whatever it took. Looking to outflank Lee, he decided to ford the Rapidan to Lee’s right. However, to reach the Mine Run Reynolds would have to march through a dense forest of oaks and pines known as the Wilderness. Even if he managed to cross that “gloomy expanse”, he would then have to face a line along the Mine Run. Again, some commanders, including Reynolds’ friend Meade, were skeptical of their chances and suggested turning back, but Reynolds refused. If they moved quickly enough, the General pointed out, they may be able to overwhelm the rebel corps in the Mine Run and then proceed to bag the rest of Lee’s army. Trusting their commander, the Army of the Susquehanna forded the Rapidan and advanced to the Wilderness.

Lee too welcomed the chance of facing Reynolds, though the Pennsylvanian’s decisiveness threw a wrench into his plans. Indeed, Lee had hoped the Federals would vacillate a little longer and that they would not dare assault the Mine Run, which would give him a chance to hit Reynolds’ other flank. When it became apparent that Reynolds was moving to the Wilderness, Lee was forced to change his tactics and quickly ordered troops to the Mine Run, hoping to completely man it, thus making it practically invincible. And so, the first stage of the battle was a race to the Mine Run, one in which the rebels counted with a powerful ally: the Wilderness itself.

The Wilderness

A “trackless maze” of second-growth trees, the Wilderness slowed down the Union advance, for the Yankees were barely able to navigate it without getting lost. By confusing the Federals and preventing them from using their superior artillery effectively, the Wilderness more than evened the odds. Mindful of these factors, Lee decided to advance into the Wilderness and give battle to “those people”. Of course, the safe option would have been to wait for the Federals at the Mine Run, but Lee wasn’t known for taking the safe option. Maybe he wanted to recoup some of the glory he had lost at Union Mills. In any case, Lee advanced forward with Longstreet and Jackson, silently and unobserved, through secret paths the local residents had shown them. Meanwhile, and after crossing at Germania’s Ford, the Federals had managed to reach the Wilderness Tavern and were now ready to advance along the Orange Turnpike.