On May 8th, 1863, a man in a gray overcoat approached a New York hotel. In his bag there were several cannisters of Greek Fire, a chemical substance that was said to ignite fires hotter and harder to extinguish than any other fuel, plus explosives. He attracted no attention in the city, where chaos simmered underneath a façade of peace. Just a few hours later, New York was submerged in a full-on insurrection, several city blocks burning and desperate militia trying to put down brutal urban fighting between Copperheads and Unionists. What had happened?

The New York powder-keg was especially volatile due to a large immigrant population that resented the domination of Yankee protestants, were Democratic in allegiance and feared competition with Black laborers. The government’s policies were bitterly resisted, especially the draft. But the administration of General Wadsworth would not stand for nullification. Using the militia and Federal troops, Wadsworth enforced the draft ruthlessly, and executed two Irish youths that had murdered an enrollment officer via a military tribunal. Discontent spilled into a riot that was quickly put down by military arms, costing around 25 lives. A tense peace returned to New York. However, on May 1st, 1863, most of the militia and Federal troops were withdrawn and rushed to fight Lee’s rebels. For a week or so, the city remained tranquil, when a rumor started that “those radicals in Congress” had passed a law to draft all males in the city as to better resist the invasion.

These rumors started when news came of the Baltimore uprising and the defeat at Frederick. Scared New Yorkers believed that the entire army had been annihilated and that the bloodbath at Baltimore was because the men there were resisting a universal draft. Vowing that they would never be drafted, and taking advantage of how the city was barre of military presence, a mob largely composed of Irish laborers approached the draft offices. That’s when Confederate agent John W. Headley, with uncanny timing that’s led many to suspect foul play, set off his explosive. The authorities believed the mob endeavored to burn the city to the ground; the mob thought the police had used artillery against them. The truth would not be revealed until later, when the insurrection had already started.

New York city was plunged into a violent insurrection that left hundreds dead and destroyed great part of the city. Police headquarters, draft offices, federal installations, the offices of the New York

Tribune and other Republican newspapers, all went up in flames. Armories and stores were sacked, and scores of people lynched by the enraged rioters. “No black person was safe”, as the rioters singled them out for particularly brutal punishment, hanging them from light posts and even burning several African American alive. The Colored Orphans Asylum was sacked and torched; miraculously, the children escaped unharmed, but their caretakers and a man who tried to protect them were murdered. Prominent Republicans and the wealthy were also attacked. The lucky ones escaped, leaving their houses to be sacked. The unlucky ones were lynched.

Elements of class warfare were evident, as the business and property of anti-labor employers was destroyed, along with machinery that had automated menial jobs, leaving many of the rioters unemployed. Protestant churches were burned, while well-dressed men were accosted by rioters that bitterly cried “Down with the rich!”, “Will you be my substitute?”, and “Can your daddy buy me out of the army?” Alongside this chaotic terror, a more insidious and organized plot was underway as at least a dozen Confederate agents were setting off fires and handing out arms and ammunition. The fires ran wild as many of the volunteer firefighters were part of the mob, sometimes lighting buildings in fire themselves. The few that remained were unable to do much.

The police were similarly helpless. Lacking the necessary manpower and strategy to put down the mob, the police nonetheless did their best to contain the riots. Seemingly abandoned by the authorities, employers and editors took matters into their own hands, organizing militias that lacked the organization and discipline of the police but shared the bloodthirsty brutality of the mob. Desperate calls for reinforcement to Albany and Philadelphia had only yielded a few hundred soldiers. It is said that many of them were invalid and sick. Unable to put down the mob, the presence of these Lincolnite troops only angered the rioters even more, especially after a showdown at Chatham Square had resulted in dozens of casualties when the soldiers opened fire.

Until then, the insurrection had seemingly only been an outpouring of popular discontentment and ethnic tensions. Then in City Hall a group of people proclaimed that New York City, unable to live under Lincoln’s despotism anymore, would secede from the Union and conclude a separate peace with the Confederacy. Was this truly the goal of the mob? Most likely not. Quasi-comic scenes took place as some men who had only wanted to loot suddenly realized they were part of a rebellion. But by then, a week into the bloody riots, it was too late to turn back. The Chatham Square massacre and Wadsworth’s uncompromising stance in previous incidents had convinced many rioters that the Army would exterminate them if they surrendered, and soon the impetus for an independent New York Free State grew.

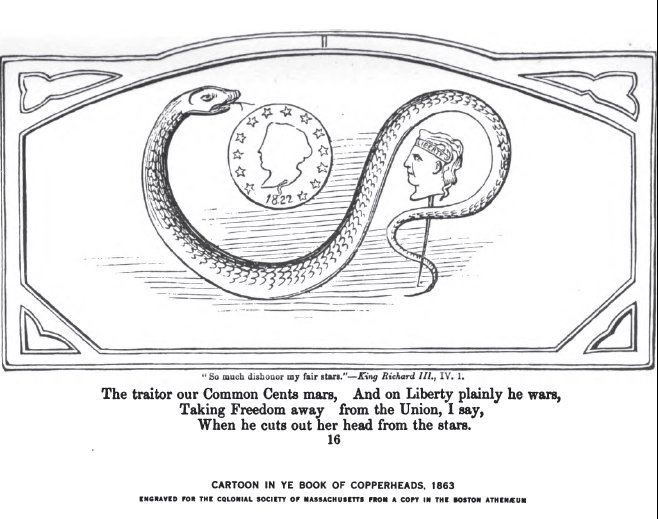

This only increased the tensions, as Unionists within the city identified the rioters with the rebels. The rebels who had just burned and looted several towns and were headed to Harrisburg and Philadelphia. In the feverish months of crisis previous and during the Campaign, wild stories of Copperhead conspiracies to overthrown the government and assure Southern victory had been shared. The existence of shady organizations such as the Order of American Knights and the Sons of Liberty had been discovered, and scared Republicans quickly magnified them into a “disciplined, powerful organization armed to the teeth and in the pay of John Breckinridge to help him destroy the Union”. With both Baltimore and New York burning at the same time that Lee was invading, it seemed that these conspiracies had finally borne fruit.

Consequently, militias that had been purely defensive now went on the attack, and men who had stayed in the sidelines now turned out to help against this new rebellion. New York descended into bloody and anarchic urban warfare, as militias of Unionists and Copperheads clashed. The government had lost all control, and soon enough extrajudicial executions and atrocities that resembled the worst of Missouri took place in the middle of Manhattan. In scenes starkly similar to those in Paris during the September massacres, a Unionist mob held mock treason trials that were followed with executions with pikes and knives, while Copperhead rioters bashed the “Black Republican puppies” against stone walls.

Though gory, these were individual incidents; most violence was contained to less flashy but just as deadly street brawls, fires and shootings. Armed with pikes, knives, maces, pistols and rifles, rioters attacked each other with murderous intent. Henry Raymond’s employees even borrowed experimental Gatling guns and tested them against the mob. Barricades were erected, and whenever one faction managed to carry one, they would usually massacre those left behind. Several people were burned to death, and of many residential areas only ashes remained. Prominent Republicans had to flee for their lives; Horace Greeley only escaped being lynched by hiding behind a wall. Meanwhile, the Confederate agents slipped out of the city, their job done.

Black men and Republicans were "pursued like wild beasts" by enraged rioters

The scenes of violence were similar down in Baltimore. In that city, the riots were explicitly political by contrast, as the rioters sought to expulse the Union authorities and join the Confederacy. At the start of the war, Baltimore had been the scene of bloody riots that prevented Federal troops from passing through and thus secured the fall of Washington. The city had then been briefly occupied by Confederate authorities, who ruled by military fiat, expulsing Unionists, terrorizing Free Blacks and taking everything they could to aid their war effort. A few months later, a Union assault on Federal Hill had unleashed a second wave of riots against the Confederate rulers this time. Black men took part this time, and it was thanks to them and other Union men that the Confederates were unable to put up a good defense and the Union retook the city.

These events left behind a bloody and bitter legacy, and the actions of “Beast” Butler only increased the discontent of the pro-Confederate population. Similarly to Wadsworth, Butler ruled with an iron fist, and was ready to execute or jail those who resisted Union rule. This reign of terror fanned the flames, and in April 28, after news arrived of the Confederate victory at Frederick, the insurrection started. While the New York riots were more or less spontaneous, the Confederate agents only contributing to the violence rather than starting it, in Baltimore they were the direct result of a Confederate ploy. Indeed, Lee and Breckinridge were well advised of this plot and its “purpose of revolution and the expulsion or death of the abolitionists and free negroes.” Ironically, it was ultimately the political need to take Baltimore that would doom the campaign, but at the time the start of the uprising helped Lee immensely by distracting Reynolds.

As in New York, the uprising started with an explosion. Soon enough more fires were started and armories sacked, and the “Maryland State Guard” went into attack. These irregular regiments had been organized and armed months previous to the uprising, using gold rebel agents had smuggled into the city. Though of course they lacked training, they had the element of surprise and numerical superiority, for most of Butler’s soldiers were off pursuing Lee. While in New York the situation took a while to degenerate, in Baltimore both soldiers and rioters almost immediately gave in into their most terrible instincts. Black men and Unionists were lynched, while the soldiers and militia treated captured rioters as guerrillas – meaning that they were executed immediately.

Old scores were settled as Confederates attacked people who were seen as Union collaborators. Others were lynched merely for being “friendly” to Blacks, which could mean as little as simply employing African Americans as laborers. Those who had truly attempted to uplift the freedmen suffered the worst, as the Confederates showed them no mercy. An attack on a school that taught contrabands resulted in a large massacre, and five women, two of them white, were raped by out of control rioters. A prostitute that catered to Black men was hung, while an interracial couple had their hearts pierced. Government buildings and the docks of the city were burned to the ground as crowds waved Confederate flags and cried “Hurrah for Breckinridge! Hurrah for Lee!”

On the flipside, Unionists proved they could be just as brutal as the rebels. Feeble attempts by the Federal authorities to impose some sort of order or moderation did not bear results, and Unionist rioters were all too willing to maim or execute rebels. Treason was broadly defined here, and people could be lynched simply for not calling for executing the Confederates, or because they weren’t loud enough. Since the Black population of Baltimore was larger, they took part in the riots not as merely victims, but also fighters. This enraged the insurrectionists who showed even more brutality when dealing with them.

Reynolds and the War Department managed to scrape off a few hundred soldiers that rushed into the city. Volleys of bullets were poured out indiscriminately and the barricades erected by the rebels were assaulted with bayonets. At one point, an ironclad started to fire into the city. But the Confederates held firm, confident in their belief that Lee was coming to save them. In truth, Lee had been routed by Reynolds and was fleeing the scene. But the Baltimore rioters could not know this, and cruelty and massacre continued. By May 22th, both Baltimore and New York were burning, both cities ankle-deep in gore and blood.

Many African Americans were forced to flee for their lives

They were not the only areas were rebel conspiracies had resulted in violence. A minor riot broke up in Annapolis when several of the delegates to the Maryland Assembly attempted to cast their lot with the Confederacy only to be promptly arrested. In Chicago, a group of Copperheads and rebels led by Captain Hines, a Confederate officer that had burned several Ohio towns, attacked a prison and liberated hundreds of Southern prisoners. Hines captured a gunboat, slaughtered the Yankee crew and used the ship to bomb the city, while his agents started several fires in order to distract from their main objective. The city was submerged in chaos as the rebels were expected to attack, but the famished and tired prisoners instead escaped to Canada just before a Federal regiment arrived.

But by far the greatest bloodshed was in the East. Reynolds, having won at Union Mills, had dispatched several regiments to restore order, thus helping explain why the rebels were not destroyed but merely mauled at Gettysburg. After Lee managed to escape, Reynolds broke off pursuit and headed to Baltimore and New York to put down these insurrections. The fighting men were furious at what they saw as an attempt to secure their defeat, and as they marched towards the burning cities many talked of “exterminating the Northern traitors” and “making secesh traitors roar”. They arrived towards the end of May and “poured volleys into the ranks of rioters with the same deadly effect they had produced against rebels at Union Mills two weeks earlier”.

Only sheer force was able to restore peace. More than 25,000 soldiers were posted in each city, where they massacred rioters and arrested the ringleaders to be trialed for treason and conspiracy. The fact that the Baltimore uprising had been a result of a conspiracy with Richmond was quickly discovered as men carrying papers and letters were captured. Likewise, a meeting of the Sons of Liberty was broken in Illinois and papers confiscated showing that Vallandigham had conferred with the Confederates and that he held the rank of Grand Commander of the organization. These revelations were followed by even more scandals, as newspapers were found to be financed by Richmond, arms cachets were uncovered, and plans of revolts and insurrections were unearthed.

“REBELLION IN THE NORTH!! Extraordinary Disclosure! Val's Plan to Overthrow the Government! Peace Party Plot!", cried newspapers that linked these conspiracies, Lee’s campaign and the riots in Baltimore and New York. Richmond, alarmed Unionists cried, had conspired with the Copperheads to sink the Union – and they had almost succeeded. Though the Sons of Liberty and similar associations never enjoyed the support and strength that Republicans attributed to them, it was absolutely true that many prominent Chesnuts had aided them. So admitted the main Confederate agent in Canada, Jacob Thompson, who said he had “so many papers in my possession, which would utterly ruin and destroy very many of the prominent men in the North”.

While in peace time or early in the war these complots could have been dismissed as the result of paranoia, in the midst of this bloody war when fear seemed to rule the day they resulted in an extreme crackdown. Scores of conspirators in Baltimore, Chicago and several Illinois towns, along with the ringleaders of the New York riots, were tried by military tribunals and put before firing squads. Disloyal newspapers were closed, and several state legislatures and municipal governments purged “the rebel element” from within their ranks: Maryland expulsed a third of its legislators, and a new law in Kentucky prevented close to half of the legislators from running for re-election due to suspected disloyalty. Many of the most prominent Copperheads fled the country, such as Vallandigham, Pendleton, Horatio Seymour and Fernando Wood, the last two linked directly to the New York riots due to their rhetoric and influence.

The Federal Army restored order through sheer brute force

The entire month would come to be known as the “Month of Blood”, not only for the appalling human toll the Pennsylvania Campaign claimed, but also due to the cost of putting down the uprising and the gory aftermath. Altogether, some 5,000 people were murdered during the Baltimore and New York riots, half due to the depravity of rioters, the other half when the Army restored order by means of the bayonet and the Minnie ball. Large sections of Baltimore and New York were burned to the ground, and the political crackdown in the aftermath of the battle devastated the National Union and increased the Radicalism of the Republicans, as even the most moderate now clamored for punitive measures against the traitors that had unleashed such barbaric and terrible bloodshed. The Month of Blood still stands as perhaps the darkest episode in American history, and the most lamentable and appalling part of an already bloody and traumatic war.

The events of the Month of Blood are contrasted in a way that gives one whiplash with the Congressional session that followed in July, 1863. This was the first meeting of the 38th US Congress, which had been elected in the midst of war. The Republican majority was slightly smaller, though still over 2/3rds, but the real development was that many conservative Republicans had left the party and been replaced by Radicals. As a whole, the Party had moved sharply to the left, and it was ready to take far more drastic and punitive measures than their antecessors. Radical influence was also strengthened because many Congressmen were newcomers, while most radical leaders such as Stevens, Sumner, Wade, Lovejoy and Julian retained their seats. This longevity, together with the unity of purpose and feeling the Radicals shared, augured “the most radical legislature that has ever assembled in the United States”.

Despite the lamentable events of the Month of Blood and the step price of the Pennsylvania Campaign, when Congress assembled the occasion seemed almost festive. Republicans quickly voted to honor the victors of Union Mills, elevating Reynolds to the rank of Lieutenant General and awarding several Medals of Honor. This included the first Black recipients of this highest award, and their gallant leader, Colonel Shaw. The Battle of Union Mills, already significant as perhaps the hardest fought victory of the Union, was even more important due to its socio-political implications. Indeed, at the same time that White rebels were burning, murdering and looting all with the intent of sinking the Union, the brave Black soldier was fighting to save it. The contrast could not be greater, and soon many revolutionary changes started to take place as Northerners concluded that Black men who fought for the Union deserved better than White rebels who fought against it.

"The manhood of the colored race shines before many eyes that would not see”, declared the Atlantic Monthly, while other newspapers said that “the names Fort Saratoga and Union Mills will be as important to the colored race as Fort Bunker and Yorktown have been to the White man” (it should be noted that Black men took part in both Revolutionary War battles). Lincoln himself took the opportunity to issue a striking rebuke to the Copperheads. Though his most important objective remained the restoration of the Union, the President said that the “emancipation lever” and the employment of Black troops had allowed the Union to achieve some of its most important victories, including Union Mills, “the heaviest blow yet given to the rebellion”.

To those who would not fight for the Negro, the President said “Fight you, then, exclusively to save the Union”. But Lincoln warned that after the war was over, “there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it”. As for those who said to give up emancipation and return “the warriors of Canton, Fort Saratoga and Unions Mills to slavery” in order to conciliate the South, the President said that such a thing was not only inexpedient, but immoral. “I should be damned in time and in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends and enemies, come what will.”

View attachment 583301

William Cargnee, awarded the medal of honor for taking the flag Shaw had dropped and carrying it to the rebel position

“The government,” wrote Orestes Brownson early in 1864, “by arming the negroes, has made them our countrymen.” The logical result of Union Mills, said Missouri’s Charles Drake, was that “the black man is henceforth to assume a new status among us.” Another man talked of changes, “which no human foresight could anticipate” largely thanks to “the display of manhood in negro soldiers.” Signs of revolution even abounded. Congress for the first time opened its galleries to Black people, and in a ceremony attended by Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass five Black soldiers were awarded Medals of Honor. Lincoln went out of his way to greet Douglass, whom he characterized as “one of the most meritorious men in America”. Colonel Shaw too received the medal posthumously. Originally, Shaw was going to receive his own tomb, but his parents insisted he be buried at Union Mills alongside his Black soldiers. "We hold that a soldier's most appropriate burial-place is on the field where he has fallen”, said his proud father.

These gestures were important, for they presaged a great change in Northern aptitudes towards African Americans. Far more meaningful was the legislation that was passed quickly by the Congress. Black soldiers, who had received half the pay of their White comrades, now would henceforth receive equal pay and bounties, and be treated equally by Army authorities. This was made retroactive to the start of their enlistment, and passed with only a few Republican stragglers opposing it. Momentous steps were taken to finally bring equality to African Americans: admission of Black witnesses to Federal courts, prohibition of segregation in transport or education in Washington, repeal of Black laws that had condemned Blacks to second citizen status in several Northern states, and voting to submit referendums on Black suffrage to the voters.

The most startling sign of change came from the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Taney’s old heart was apparently not able to withstand the rigors of war, for he passed away in March, 1863. William Strong, a respected jurist said to be “sufficiently Radical for even the most radical Senators”, was confirmed in the July session. Now composed of five Lincoln-appointed Justices, the Court had been completely reconstructed. George Templeton Strong saw just how striking the change from Taney to Strong was, commenting that Taney’s death and the victory at Union Mills meant that “Two ancient abuses and evils were perishing together.” This was “the most sweeping judicial metamorphosis in American history.”

Though these developments gave hope to the friends of Emancipation and the freedmen, underneath a darker desire for punitive measures lurked. The Month of Blood had shocked the nation, and reports of continued guerrilla warfare and terror against Unionist and prisoners of war stiffed the resolve of the lawmakers. Senator Wilkinson introduced a bill to limit the clothing and rations of Confederate prisoners to the amount given to Union prisoners, which was in fact “a directive to starve and freeze Confederate prisoners of war to death”. Senator Henry Lane of Indiana, usually a moderate, introduced a motion to retaliate against “those felons, and traitors, and demons in human shape.” Lincoln himself denounced Confederate actions as “a relapse into barbarism and a crime against the civilization of the age”, and turned a blind eye to retaliation in the field and the military execution of the conspirators behind the Month of Blood.

The war had taken a gory turn towards extermination, and, Lane signaled, “if this is to be a war of extermination, let not the extermination be all upon one side.” Even Senator Sumner, usually characterized by idealism, declared that the war was now a struggle “between Barbarism and Civilization,—not merely between two different forms of Civilization, but between Barbarism on the one side and Civilization on the other side.” In line with this new policy of vengeful war to the end, Congress passed a law defining “crimes against the laws of war” and “crimes against the laws of nations”. Under these laws, Breckinridge, Davis, Forrest, Johnston, indeed, the majority of the Confederate leadership including their Congress and state authorities, would be liable for execution for ordering or allowing massacres to occur under their watch.

The Month of Blood forever linked opposition to the war with treason

Nonetheless, and despite this cathartic outpouring of vengeful sentiments, as Eric Foner points out, the driving force behind radicalism was a utopic vision of what the nation could be. Simply hanging Johnny Breck and Bobby Lee would never accomplish the far-reaching changes the Radicals envisioned. Seizing the Civil War as the perfect opportunity to enact changes that would build a “perfect republic” of equality, Radicals pushed forward a program of confiscation so as to remake the South. “The demon of caste”, said Charles Sumner, would thus be eradicated, and a new United States would be born from the ashes of war and slavery. A new nation, where the new birth of freedom Lincoln spoke of would be an actual reality. But how was this to be done?

The answer, many Radicals said, was confiscation. Radical confiscation schemes were designed to change the social fabric of the South. So declared Stevens, saying that without confiscation “this Government can never be, as it has never been, a true republic. . . . How can republican institutions, free schools, free churches, free social intercourse exist in a mingled community of nabobs and serfs?” Since the Union had decided to liberate the Negro and allow him to remain the United States, provisions had to be made for his future. And the Radicals broadly agreed that his future was as an independent yeoman, tilling the lands confiscated from traitors.

Yet confiscation was a difficult, touchy subject. The greatest obstacle was that it was fundamentally opposed to traditional American ethos, that included the sanctity of individual rights. This principle had been codified into the constitution, which prohibited confiscation without due process of law and did not allow forfeiture of property for life as a punishment for treason. Stevens’ arguments that “constitutions that contradicted the laws of war should be ignored” and that the rebels could not be protected by the constitution they had defied were too radical for most Republicans. They also went against the President’s position that the Southern states remained in the Union.

The First and Second Confiscation Acts had allowed the courts to take the property of people convicted from treason, but these acts adhered to constitutional restrictions and required courts to be enforced. Both acts, as a result, had been largely inoperative, as there were no courts in the areas in rebellion and Lincoln still hoped that conciliation would be a better way to cobble the Union back together. This had had such ridiculous consequences as Breckinridge himself being protected from confiscation, since it could not be proven that the lands he held in Illinois and Indiana had been used to aid the rebellion as the First Act required. Breckinridge’s properties were finally confiscated under the Second Act in

in rem trials, but this did not solve the issue that most traitors held property not in the North but in the South.

By mid-1863 Lincoln and most Republicans had surpassed their early timidity. They no longer wanted to conciliate the South, but to reconstruct it and bring new classes of people to power. Thus a movement for a Third Confiscation Act was created. But the extent and scope of the punitive measures to be taken remained in contention. Some extreme Republicans wanted to extend the punishment to all traitors, but moderates opposed such measures. If widespread confiscation was approved, Senator Browning said, Southerners would be reduced to “absolute poverty and nakedness”; Representative Thomas warned that “the bed on which the wife sleeps, the cradel [sic] of the child, the pork or flour barrel” would be confiscated too, engendering a terrible hate that would prevent the South from ever accepting Union rule again.

Outside of confiscation, the Union came to control large tracks of abandoned land

However, such arguments were starting to lose potency. During the debates over the Second Confiscation Act lawmakers had predicted that if the North signaled it would confiscate property, the Confederates would resist to the bitter end and begin to massacre loyal men. The North had not enacted conscription; the South had done all that anyway. Why should the North still try to conciliate them? Or, in other words, should the man who massacred loyal men be allowed to return unmolested to his farm, while the children and widow of the slain Unionist was to be left in the cold? The Union, lawmakers said, had a responsibility to reward loyalty and punish treason, and the easiest way to achieve this was through confiscation.

But even if the objectives of the Republicans had changed, the Constitution remained the same. Lincoln had insisted that the Second Act be amended to specify that forfeiture of property was limited to the life of the owner to maintain it within the Constitution’s boundaries. This was necessary, for the main position the Lincoln administration followed was that since secession was void and null, the states had never left the Union. This implied that Confederates remained under the Constitution and that, once the war was over and war powers were no longer operative, they would enjoy the same rights and privileges as Northerners. To say otherwise would be to say that the Confederates had in fact left the Union, thus admitting that secession was a legal fact.

Another factor that influenced the debates over confiscation was the question of how freedmen labor was to be organized after the war ended. The solution of putting them in camps where they did menial jobs for the Army was unsatisfactory. The camps were rifle with disease, one man calling them “disgraceful to barbarism”, and were furthermore easy prey for rebel raiders. Many Black men joined the Union Army, being sent to the front or used to protect their own camps, but aside from them “the rest are in confusion and destitution”, admitted Lincoln. To solve this problem, many officers, chief among them John Eaton, started to put the freedmen at work in “home farms” made with lands confiscated from or abandoned by rebels. This seemed an ideal solution. It would not only calm racists who resented how “idle negroes” were maintained on the taxpayer’s dime, but also allow the freedmen to earn their own living and produce goods the Union desperately needed, such as cotton.

But for that to be a permanent solution much more land would be needed, giving strength to arguments in favor of confiscation. Yet the organization of freedmen labor under military auspices suffered from the fact that the military was not completely sympathetic to African Americans, and also how their rights took second place to the Army’s needs. As a result, in several areas generals managed a “free labor” system that seemed to be slavery under another name. Consequently, freedmen were forced to sign yearly labor contracts by the Army, and although the government mandated that freedmen were to be treated with respect and dignity, they were often subjected to poor treatment and abuse.

The situation, for abolitionists and Radical Republicans, was unacceptable. Decided to take the process of emancipation out of the military’s hands, provide a guideline for how freedmen were to be emancipated and made to work, and start the process of confiscation, Republicans crafted the Third Confiscation Act. This act is sometimes known as the First Reconstruction Act, though that is something of a misnomer since the act did not dispose terms for how the reconstruction of the rebel states was to happen. But the act did provide for measures that had far reaching effects beyond mere confiscation, and served as a prelude for the policies the Union would follow once victorious.

Contrabands lived in squalor and disease

The act, in the first place, defined new Federal crimes under the umbrella of rebellion, not treason. This was done so as to evade the constitutional prohibitions when it came to punishing treason; since the Congress was not punishing treason but rebellion, confiscation was permitted. This was a distinction without a difference to opponents of the bill, but Republicans had little reason to listen to the Chesnuts. Confiscation proceedings could be carried in rem, without the need for the accused to appear before the court. If the person was found guilty of “serving in, aiding or providing comfort to insurgent combinations” formed with “the purpose or overthrowing or resisting the government of the United States”, then all his property, including real property, would be forfeited and would enter the national domain.

The bill further declared that all the land that the states in rebellion held as part of their domain would be forfeited and now belong to the nation. The same would happen to abandoned lands, unless the owner appeared before the court and proved his loyalty. The bill also reaffirmed the responsibility of the Treasury to collect taxes on property behind Union lines. Previously, when the owner failed to pay, the land would be sold in auction; now, it would enter the national domain. The bill ended with the bold affirmation that what was being punished was not treason. Treason itself would be punished only in

in personam trials, and included the possibility of execution if the defendant was found guilty of crimes against the laws of nations or war.

The real innovation of the Third Confiscation Act was that now Congress would provide the courts through which confiscation was to happen. They took the form of the Bureau of Confiscated and Abandoned Lands. This was one of the three bureaus created by the bill, the other two being the Bureaus of Freedmen and Refugees, and of Justice and Labor. The three bureaus would be under the authority of the new Justice Department, whose head would be the Attorney General. Under the argument that there was no legitimate government in the seceded states, and that to leave the administration of justice to the military would be unconstitutional and unrepublican, Congress empowered all three bureaus to establish courts to enforce Congressional directives in their field. Thus, the Land Bureau was capable of holding in rem trials and confiscate lands.

The creation of the Bureaus is owed to the Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, which Northern philanthropists had convinced the government to create in order to investigate and address the situation of the freedmen. Though at first there was an attempt to give the power to Chase’s Treasury, after his failed bid to oust Seward the Secretary’s allies gave up. Yet, since the Bureaus were meant not only for war administration but also for aiding the South’s reconstruction once the war was over, it was decided to place them under the brand-new Justice Department, though they would of course collaborate closely with the War Department. The Freedmen’s Bureau would oversee the transition to freedom and help the indigent, wounded and sick, while the Labor Bureau would see that the administration of justice was equal and fair, especially when it came to labor.

These two bureaus were planned for reconstruction then. The Land Bureau, by contrast, would operate in war time. Soon enough, thousands of bureau agents toured the South, surveying the lands behind Union lines. They would then call for someone accused of rebellion to prove his loyalty; if the person did not appear, the Bureau would declare his or her land confiscated. Land confiscated by the bureau would then be distributed among the freedmen and Unionist whites, who could receive up to forty acres. Alternatively, it could be leased to loyal Southerners or Northern businessmen, who would employ freedmen under the oversight of the Labor Bureau.

By assuming the responsibility of taking care of the freedmen, the government was starting nothing less than a social revolution

However, before the bill received the President’s approval, there were several kinks to be ironed over. The principal one was the division between Lincoln and the Radicals. Lincoln had come to accept confiscation, but he still envisioned it as something of a political “carrot and stick” that would aid him in the task of Reconstruction. By only targeting the rebel leaders and opening the land redistributed by the Bureau to recanting Confederates, Lincoln hoped to drive a wedge between the landed aristocracy and the poor whites of the South. Lincoln, too, accepted that land could be taken permanently from the South’s leaders, but wanted to retain the power to give it back if the person was willing to accept the government’s conditions. That, he hoped, would push rich planters to desert the Confederacy and pledge allegiance to the Union.

This was part of Lincoln’s new vision for reconstruction. Separating treason from rebellion and giving it harsher penalties while at the same time only allowing

in personam trails would force the leading rebels to escape the country, thus preventing a series of executions from following the war. It was, in effect, a form of exile. Excepting poor Southerners from confiscation and opening the possibility of receiving confiscated land would conciliate them to Union government. And by creating a Black yeomanry Lincoln would be able to reassure Northerners that feared that African Americans would migrate en masse to the North. Most importantly, the threat of being trialed for treason or having their properties confiscated would serve as a stick to maintain the loyalty of rebels in areas under occupation; the offer to restore property if they accepted the Union would serve as a carrot to stimulate desertion from the Confederacy.

Lincoln, then, conceived of confiscation as a purely political maneuver meant to weaken the Confederacy, rather than the sweeping social transformation the Radicals envisioned. As a result, the original, much harsher bill had to be amended several times. In the first place, trials would be individual. This was a somewhat farcical move, for the Land Bureau could hold hundreds of “trials” a day, but it allowed Lincoln and his subordinates to make exceptions when it was politically expedient. The reformed bill also allowed those Confederates that took loyalty oaths to receive land, when the Radicals wanted to limit it originally to only “true Union men”. Originally, the bill also ended the practice of leasing land, which was retained, and finally provisions that would favor African Americans when it came to redistribution were stricken out. The resulting Third Confiscation Act was much less radical than it could have been. Though radicals seethed at these concessions, they accepted defeat. Lincoln signed the act on August 25th.

A disgusted Chesnut described the scenes of jubilee that followed the passage of the act: “Thad Stevens grinning like never before, Sumner dancing a la anglaise, Ben Wade almost jumping with joy”. Yet if the Third Confiscation Act was certainly a great victory for it inaugurated the process of Southern reconstruction, it was not a complete radical triumph. The act’s provisions were dubious in legality and somewhat limited in scope, and all Republicans realized that a firmer basis for reconstruction had to be given. As the July session ended, most Republicans parted with the understanding that they would provide that basis when they met again in December, in the form of a Thirteen Amendment. In the meantime, the war had still to be won, but Union prospects seemed brighter than never before. As the North set plans for victory and Reconstruction, down south the rebels were experiencing hard times in Dixie.