And for all the horrors and sacrifices, the boys on high will try and scapegoat them for their own failure"A mincing machine", Pierre repeated. "A mincing machine." He stared at the carnage once more and saw the Germans creeping forward as the thunder of guns drew close. My God, my God, why have you abandoned me? Pierre Soilon grabbed his sidearm and ran downstairs, though he couldn't have said why. Here lie the men of Platoon A, 202nd Line Regiment, he thought as he took aim. Here they fought and died for their country.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

REDUX: Place In The Sun: What If Italy Joined The Central Powers?

- Thread starter Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 40 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXVI- Setting Up For Failure Chapter XXVII- Frustration in Flanders Chapter XXVIII- The Road to Nice Chapter XXIX- The Nivelle Offensive Part IV: The Spectre Of Revolution Chapter XXX- The First Mutiny Chapter XXXI- Another Change In Command Chapter XXXII- The Nanterre Massacrepls don't ban me

Monthly Donor

ahem * proceeds to tune Guitar*Depression, the country being born here. BTW, how's the air war going? Verdun had a lot of combat.

HIGHER, THE KING OF THE SKY

HE'S FLYING TOO FAST AND HE'S FLYING TOO HIGH

HIGHER, AN EYE FOR AN EYE

THE LEGEND WILL NEVER DIE

As Bismarck rightly noted, that ship sailed when the USA succeeded. Or maybe when Napoleon failed. Either way, I don't see it as a real possibility in the early 20th century. You need a different early 19th century (or, of course, even earlier).Yes, now that you mention, I would certainly love a TL where France, Germany, Russia, and well, basically all European powers shake hands and go Britannia Delenda Est!

French troops parading down Trafalgar Square? Russians flying the Imperial tricolor from Westminster Palace? German ships anchored in the Thames? Yes please.

Chapter XXIV- A Change in Command

Chapter XXIV

A Change in Command

By the end of May 1916, both sides at Verdun were exhausted after three months of continuous combat. Almost a million German soldiers had attacked on February 21st, of which one hundred thousand were now dead or wounded. France's Second Army, which had peaked at 320,000 men in early March, had taken over sixty percent casualties- not the 3:1 ratio which Erich von Falkenhayn had promised the Kaiser, but close enough. The French positions at Verdun had been reduced to a few pockets of stone, seldom more than three hundred square metres, on the west bank of the Meuse. German troops had conquered the eastern half and were fighting their way through the west. As the battle inside the city had dragged on, Petain had moved the remnants of XX Corps in a last-ditch effort to, at minimum, contain the Germans on the west bank. This left la Voie Sacree- rendered near useless anyway by overuse and a shortage of vehicles- exposed, and the Germans struck southeast. Seizing the aptly named town of Regret on the 17th, the 12th Reserve Division reached the Meuse south of Verdun a day later, linking up with the German forces on the opposite bank.

Verdun was now encircled.

Inside the city, Major-Generals Guillaumat and Balfourier requested permission to evacuate. Their force kept dwindling- rough estimates suggested three hundred killed every day with twice that number wounded- and in a few more weeks they would have nothing left with which to hold the city. Everything was collapsing around them, there were no more reserves, and the German ring around the city would harden daily. If they did not break out immediately, tens of thousands of Frenchmen would be killed or wounded. Worse, all the German forces focused on grinding them down would be free to turn south and break through into the expanse of Eastern France. For all his commitment to holding the city, Philippe Petain understood that he was beaten and approved a withdrawal.

Before the evacuation from Verdun could go any further, domestic politics intervened. The German push of May 17th had cost Joseph Joffre his last bit of political capital, and through no fault of his own, Petain would come tumbling down with him. War Minister Joseph Gallieni had had a complicated relationship with Joffre. The hero of the Marne had endorsed his push for the position when Aristide Briand formed a government in autumn 1915, but the two then fell out over whose authority superseded the other's. Not long after this, Gallieni was diagnosed with prostate cancer and given only months to live. Constant pain clouded his judgement and made him intolerant of even the slightest criticism. Briand ought to have sacked him with as much grace as possible, and let him spend the rest of his days at home. Gallieni would hear none of it, though, and Briand- whose government was still very new and who lacked a viable alternative to fill the position- left the dying War Minister in place. When the Germans unleashed Operation Gericht, Gallieni went before the Council of Ministers and accused Joffre of wanting to abandon the city. This charge was not without substance, but Joffre had been clever enough to not write anything down, and he was able to deflect Gallieni's accusation. The furious War Minister resigned on March 16th and died two months later at his home in Versailles.

The emergency at Verdun left no room for squabbling at the top. Briand understood what Joffre brought to the war effort and that alienating him would do nothing for the country. Besides, having held office for only six months, the last thing he needed was another hot-headed War Minister to cause tension with the military, which the press would pick up on and which would, in turn, sap public confidence in his Government. Pierre Roques had everything Briand wanted to see. Roques had three decades of solid service behind him, but no great victories which might build him into a cult figure as the Marne had done for Joffre. Above all, he was a friend of the great general, who voiced no objections to his appointment.

For the first two months of his term, War Minister Roques balanced between Joffre and Briand. The former was focused on finding a way to stem the tide at Verdun: he had no time for political drama back in Paris. Gallieni had wasted his time and tried to undermine him; all Joffre wanted was someone who would get off his back and let him do his job. Briand needed a man who would keep relations smooth with both the generals in the field and the civilians in his Government. Above all, the Prime Minister needed Roques not to say the truth: that there were not enough Frenchmen to go around and that victory was no longer possible. A lesser man could not have played the two contradictory roles, but Roques found a way.

Germany's small offensive on May 17th threw the balancing act off a cliff. Nothing could mask the truth that with Verdun surrounded, victory was impossible. Briand asked Roques how feasible it would be to break through to the city; the War Minister replied that it would take ten fresh divisions and a year's worth of luck. "Then how", roared the Prime Minister, "can my Government expect to retain public confidence?" When Roques only shrugged, Briand threatened to fire him unless he gave him something which the media could present as a victory. Roques retreated to his office, and after an afternoon of deliberation, came up emptyhanded. In a stunning display of moral cowardice, he decided there was only one thing to do: kick the problem down the chain of command.

A telephone call interrupted Joffre's morning work on May 20th. He greeted his old friend, but the ice in Roques' voice took him aback. The War Minister began by saying that this was Briand's decision, not his- it was just that his position compelled him to be the messenger. The political effects of the situation at Verdun were "disadvantageous"- no more elegant a euphemism for "disaster beyond repair" existed. Roques explained to Joffre that if the city fell, Briand's government and both of their careers would go with it. Both of their jobs, Roques emphasised, were in equal danger, but Joffre had an advantage over him. Whereas Roques was stuck in Paris and could only influence events from a distance, Joffre commanded the whole French Army. If there was a solution, he was the man to bring it about.

"Suppose, my dear sir", Joffre began, shooting venom through the phone line, "that there was a means by which the hundred divisions of France could be committed to the struggle at Verdun. Suppose there was no front in the Alps consuming a quarter of our Army, suppose our British allies were not already exerted to their limit, holding the line as far as they can bear to free as many of our divisions, suppose the need for a strategic reserve did not exist. Please convey my message to the Prime Minister that if one imagines these things to be true, a solution presents itself easily: we could send sixty or seventy divisions to match the enemy one for one. These things not being so, then, I invite the Prime Minister to investigate my performance- and if, having done so, he attempts to levy criticism against my performance, he will come up wanting!"

"My friend." Joffre could hear the War Minister's deep breaths on the other side of the phone line. "I do not say you have done a single thing wrong- au contraire. But this is a political matter, and if the Prime Minister cannot show results..."

Joffre nodded. "Je comprends." Understanding did not mean acceptance. He was the hero of the Marne, commander of the whole French Army- the strongest French soldier since Bonaparte!- and some upstart politician was about to fell him to save face. Unless... "I do not command the Second Army. I do not manage the battle day-to-day, nor am I consulted about every single thing." This was dirty, but if it worked, it would save both of their careers. "You would be better served talking to General Petain."

"Ce n'assez pas." Joffre's heart sank. "From a military perspective, of course I agree with you. Whatever problems exist at the front are Petain's, not yours. But to sack only one general in the aftermath of such a calamity will not appease the public." Joffre clenched his fist around the receiver, his knuckles pale. "I will be damned, Pierre Auguste, if I become the Prime Minister's sacrificial goat!" Silence dragged on, broken only by the telephone line popping and cracking. Unless... "Are you still there, Monsieur?" A murmur from Roques, and Joffre continued. "Petain is a good man, but he has been doing too much. As I am sure you and the Prime Minister know, I promoted him to command Army Group Centre at the start of the month, the better to organise our forces across the line, yet I left him in command of the Second Army at Verdun, my logic being that his expertise there might make all the difference between victory and defeat. Suppose I leave Petain in charge of Army Group Centre and bring a new man in to command the Second Army?"

"That would not appease the Prime Minister", Roques said, "but if this new man turned the battle's tide, all would be well. I do not know Petain as you do, but it seems..." As though he's a damned fool. Joffre would have been all too ready to agree, except he knew how little his subordinate had to work with. "...as though he has too much for any one man. Whom did you have in mind to lead at Verdun?"

One of the corps commanders? Denis Duchene had done his career no favours by letting the enemy break through on the Right Bank early on. Georges de Bazelaire had thrown too many good men away at Fort Sartelles and lost la Voie Sacree, while Guillaumat and Balfourier, for all their competence, were trapped in the middle of the city, pinned up against the left bank of the Meuse. Even if they could be extracted, neither would be in any shape to command a whole new army. Besides, the Second Army was a shadow of its former self. For an offensive to succeed, it would need a minimum of three extra corps: these would have to come from Italy or the strategic reserve, and it was only right that they come under a new man. "Let me think on it", Joffre told Roques, "and I shall call you back in a few hours."

"De rien." The War Minister hung up, and Joffre telephoned the Chief of the General Staff of the French Armies. Their titles suggested the same position (his was Chief of the Army Staff), but for all intents and purposes, Noel de Castelnau was his right-hand man. Between them, what they did not know about the French Army and the war was not worth knowing. After a few hours of deliberation, they settled on a new commander for Second Army, and to pull twelve divisions from the Italian Front. Roberto Brusati had finally stopped banging his head against the gates of Menton, while the political and military situation meant that Verdun was worth more than Nice. An Italian breakthrough would be a major problem, but for the necessary counteroffensive to fail would be a catastrophe.

As with so much else, a bitter irony clouds this decision. Had Joffre accepted the loss of Nice and given Petain reinforcements from Italy three months ago, the situation at Verdun would have looked very different. As it was, these twelve divisions would prove too little, too late, and be placed in the hands of a man unsuited to command them. Just like the politicians of summer 1914, little did these two Frenchmen realise they were leading their country off a cliff.

Later in the afternoon, Joffre had an unpleasant telephone exchange with Philippe Petain, then a much longer conversation with one of Petain's subordinates before telephoning Roques once more. "The Second Army's new commander en route as we speak", he said. "Robert Nivelle." Joffre went on to outline the proposed counteroffensive to break into Verdun and reopen communication with the surrounded French forces there, to at least drive the Germans out of the city proper.

"If this does not work", Joffre declared, "you can cut off my head, and de Castelnau's, and Petain's, and Nivelle's. But you had best be quick, because if this does not work, Kaiser Wilhelm will cut the head off all of France."

...The reason that Brusati has stopped banging his head against a wall is that Cadorna is replacing him with a more competent commander, or at the very least someone who has learned the hard lessons from the earlier fighting, who will then be throwing HIS head against the wall (and Falkenhayn will likely accept the deployment of the Alpenkorps now in order to increase the pressure against France in this critical moment). Nice is going to fall soon and Nivelles counteroffensive against Verdun is going to bleed the French on a level only imagined in Falkenhayns wildest dreams.After a few hours of deliberation, they settled on a new commander for Second Army, and to pull twelve divisions from the Italian Front. Roberto Brusati had finally stopped banging his head against the gates of Menton, while the political and military situation meant that Verdun was worth more than Nice.

Lovely that the French political system and focus upon a single point shall undo all of the sacrifice and quibbeling that has been done so far. Had reality set in earlier, had the French reacted more coherently.. Now they need however long it takes to maneuver twelve divisions halfway across the country, through the rail network, all the supplies for said corps, if need be upgrade the infrastructure around the region to handle said new troops... That will take time. They might at least realistically be able to stabilize the front against further attacks and dig in to counterattack at a more opportune time.. But the politics won't permit it.

Also having no idea geographically but does Nice have a port or not? And if so is it a decent one? That might force the French to sally out their fleet once more to try and give artillery support to the city and draw out another fleet battle. The Italians likely wouldn't have any heavy units available beyond pre-DN's or even lesser ones given their surviving BB's are likely gonna be in repair yards. So if they push they could have local superiority to bombard.

That will definitely get the RN out in force at least! There any plans for further fleet engagements at this point?

Also having no idea geographically but does Nice have a port or not? And if so is it a decent one? That might force the French to sally out their fleet once more to try and give artillery support to the city and draw out another fleet battle. The Italians likely wouldn't have any heavy units available beyond pre-DN's or even lesser ones given their surviving BB's are likely gonna be in repair yards. So if they push they could have local superiority to bombard.

That will definitely get the RN out in force at least! There any plans for further fleet engagements at this point?

Choppity choppity

Your heads will now adorn

The wall of my property

-Kaiser Wilhelm II (probably)

Your heads will now adorn

The wall of my property

-Kaiser Wilhelm II (probably)

Oh no oh fucking no. The poor French they are putting their head in the crocs mouth here. Stripping the italian front just before they pull off their next hammer swing. I feel bad for them

Chapter XXIV

A Change in Command.

The Italians would have a single dreadnought not in the shop (making the reasonable assumption they need it) the French would have 2 Bretagne fresh. The fact the med fleet only would have 10 battleships including these new Bretagne and a good portion also are in the repair docks means the margins are probably too close for the French to riskAlso having no idea geographically but does Nice have a port or not? And if so is it a decent one? That might force the French to sally out their fleet once more to try and give artillery support to the city and draw out another fleet battle. The Italians likely wouldn't have any heavy units available beyond pre-DN's or even lesser ones given their surviving BB's are likely gonna be in repair yards. So if they push they could have local superiority to bombard.

That will definitely get the RN out in force at least! There any plans for further fleet engagements at this point?

Last edited:

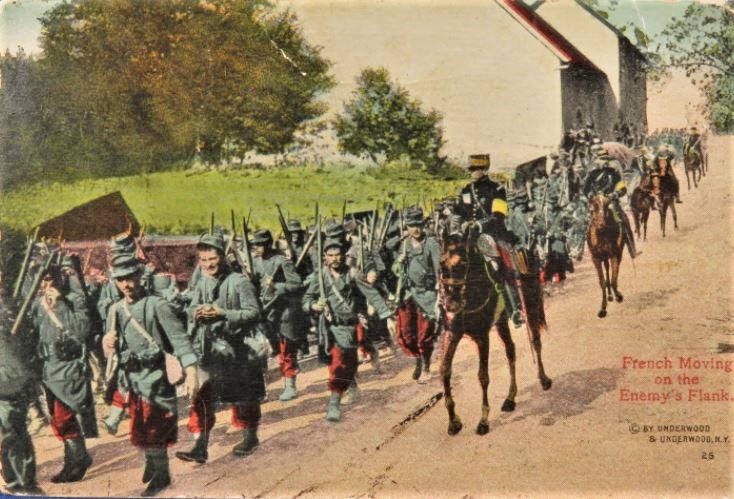

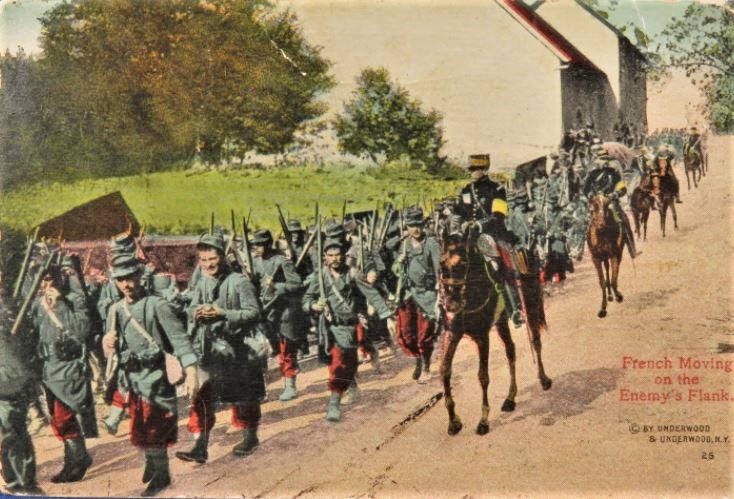

They need to reissue red pants. That change was when things started to go wrong. It hurt moral*. Le pantalon rouge c’est la France!” (Former French Minister for war, M. Etienne)Oh no oh fucking no. The poor French they are putting their head in the crocs mouth here. Stripping the italian front just before they pull off their next hammer swing. I feel bad for them

*Napoléon Bonaparte — 'In war, the moral is to the physical as ten to one.'

Yes it was truly the French will with their red pants that wins them their wall.They need to reissue red pants. That change was when things started to go wrong. It hurt moral*. Le pantalon rouge c’est la France!” (Former French Minister for war, M. Etienne)

*Napoléon Bonaparte — 'In war, the moral is to the physical as ten to one.'

The Germans around Verdun in 1915/6 were attacking on limited fronts with infiltration type tactics and lots of artillery, pioneered by General Karl Bruno Julius von Mudra, in the Argonne. Infantry had automatic weapons, mortars, flamethrowers and satchels of grenades and advanced in small groups after hurricane bombardments. They did not use human wave tactics after 1870. Units on occasion got ambushed or new commanders messed up (the new reserve corps around ypers). These tactics were not properly used during the "Verdun"offensive, so German losses were 2 for every 3 French losses, vs the 1 for 4 or 5 French losses typical of von Mudra attacks. His early attacks used 76 77mm, 26 105mm, later he was given 16 150mm guns, 10 210mm and another 10 of larger sizes along with 40 heavy and medium Minenwerfer. Each attack was brigade sized and only targeted a few thousand meters of front. The next attack had 20 more 210mm howitzers and 36,000 hand grenades on a 2 kilometer front. French Deputy Abel Ferry estimated the French lost 80,000 men in the Argonne in 1915, the German losses were about 1/4 of that. 1915 Allies had 390,000 killed in Flanders and France. German losses were 114,000.

Human waves were a Anglo/French thing until after the Nevelle offensive. The French from 1915 used more guns and less bodies. The Germans had lots of Howitzers at the division (36 105mm per active division 1,872+ 105mm)/Active Corps level (368 150mm) and higher (96 210mm, 2 420mm, 5 305mm) and added more, the allies had a severe shortage of them until 1917 on. France started the war with 308 120mm and 155mm guns and howitzers.

At the day to day level the Germans had a big advantage in indirect fire weapons.

German Active Corps

72 105mm howitzers

16 150mm howitzers

French Active Corps

0 howitzers.

Human waves were a Anglo/French thing until after the Nevelle offensive. The French from 1915 used more guns and less bodies. The Germans had lots of Howitzers at the division (36 105mm per active division 1,872+ 105mm)/Active Corps level (368 150mm) and higher (96 210mm, 2 420mm, 5 305mm) and added more, the allies had a severe shortage of them until 1917 on. France started the war with 308 120mm and 155mm guns and howitzers.

At the day to day level the Germans had a big advantage in indirect fire weapons.

German Active Corps

72 105mm howitzers

16 150mm howitzers

French Active Corps

0 howitzers.

Last edited:

These last chapters, the narration has talked about Petain's successor with almost dread. Who could possibly be that bad-

...Well, fuck."The Second Army's new commander en route as we speak", he said. "Robert Nivelle."

He speaks very good English, the British love him.These last chapters, the narration has talked about Petain's successor with almost dread. Who could possibly be that bad-

...Well, fuck.

I'd count that a malus in the French army, honestly.He speaks very good English, the British love him.

These last chapters, the narration has talked about Petain's successor with almost dread. Who could possibly be that bad-

...Well, fuck.

He speaks very good English, the British love him.

I thought about casting General Melchett, but Nivelle’s English is just a touch better.

Joking set aside, his perceived ability to coordinate with the British was a factor leading to his promotion; here, there’s going to be a lot less cooperation and a lot more shouting matches at Allied Command.I'd count that a malus in the French army, honestly.

Next update tonight or tomorrow, a closer look at Nivelle plus the first glimmer of mutiny in the French Army.

The British already have Haig.I thought about casting General Melchett, but Nivelle’s English is just a touch better.

"You see Blackadder, in a attempt to boost the frog's fighting spirit, I'm sending you to Verdun. Don't worry, Captain Darling will accompany you, as will George."I thought about casting General Melchett, but Nivelle’s English is just a touch better.

Sorry, had to make a Blackadder joke with that opening.

But yeah, gonna be bad, because I don't think this is a easy win for France.

Only thing worse would have Petain sent to Vietnam as a scapegoat after the failure of Nivelle's cunning plan."You see Blackadder, in a attempt to boost the frog's fighting spirit, I'm sending you to Verdun. Don't worry, Captain Darling will accompany you, as will George."

Sorry, had to make a Blackadder joke with that opening.

But yeah, gonna be bad, because I don't think this is a easy win for France.

Threadmarks

View all 40 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXVI- Setting Up For Failure Chapter XXVII- Frustration in Flanders Chapter XXVIII- The Road to Nice Chapter XXIX- The Nivelle Offensive Part IV: The Spectre Of Revolution Chapter XXX- The First Mutiny Chapter XXXI- Another Change In Command Chapter XXXII- The Nanterre Massacre

Share: