Chapter 18: From Canada’s Fair Domain

Spencerwood, Quebec City, Canada East, April 1862

The palatial grounds of the Spencerwood estate were ideal as a retreat and home for the Governor General of the United Province of Canada. Originally built as a grand estate for the third governor of New France in the time of the French Regime in 1633 it was eventually property of the sisters of the Augustine order the Hôtel-Dieu in 1676, after the Conquest it became the home of Henry Powell in 1780 who expanded the grounds and built a grand villa with fresh English gardens for the grounds. These were expanded on again in 1833 with elms, oaks and trails; and finally again in 1854 when purchased by the government and made the official residence of the Governor General.

The Viscount Monck had taken up residence in the castle like manor home early in November of the previous year. He had taken a liking to the home, but his ever adventurous wife, the Lady Elizabeth Monck, had taken to properly decorating the residence to be more suitable to her tastes. Not that Monck himself minded, he was more than happy for her to have something to do in order to distract herself from the distressing events taking place only so far away. She seemed to be in good spirits however, entertaining guests as though there were no unpleasantness to the south, even sparing time to make the socially awkward Lord Lyons laugh as he had passed through.

Monck, large, comfortably built with square shoulders, strode casually amongst the gardens with his guests. The April rains had subsided for the afternoon, and he had spent so long trapped in the Citadelle at Quebec that he felt it was only fair that he stretch his legs in the beautiful gardens. None of his visitors seemed to mind the informal setting of the rather official meeting. In a combination of suits and uniforms they trailed him in the gardens. Col. Taché in his own red tunic stood next to Col. Lysons, and behind them came Cartier and Galt, all prepared to inform him on the state of the Province’s readiness for war.

“It is a shame Premier Macdonald could not join us today. His illness is most inconvenient.” Monck said. Behind him the three Canadian ministers exchanged uneasy glances, all were aware of the exact nature of Macdonald’s “illness” this spring.

“John has worked himself too hard since November sir, months without a proper rest. It is only natural he should have some malady befall him with his manic energy enveloping him in the last four months.” Cartier said.

“I hope he returns to health soon. Send him my best, but you’re sure my doctor would not be able to help?”

“John’s a tough old Scot my lord, a few drinks and he’ll be back on his feet.” Cartier replied mildly. In truth the drink had put him off his feet, and he would no doubt be off them for another week until he had recovered. The pattern of bursts of manic, brilliant energy, followed by weeks of heavy drinking were common to Cartier and Taché, but it would be better served that all the members of the Coalition not be made totally aware it this yet.

“I am glad to hear it, but for now we must attend to business. How are the Province’s finances?”

“So long as our loan from London is secure the Province stands to be able to lean on 18 million dollars to finance this year’s works for both warlike and civil expenditure.” Galt replied, but grimaced. “We have already borrowed a great deal, so we are currently running at a deficit. Though Macdonald’s efforts and those of other private parties have gathered 234,000 dollars for other expenditures as well throughout the winter and spring.”

“The Province is of course not fighting this war alone.” Taché added quickly nodding to Lysons.

“The Province has done a creditable job answering the call for men from Her Majesties government.” Lysons said looking immensely pleased without smiling.

“I’m sure that the people of the Province have done all in their power to aid in the defence of Her Majesties domains here in North America. Though I would be greatly pleased to learn the entirety of the fruits of their labors.” Monck replied. Lysons nodded in a professional fashion retrieving a note from the pouch he carried.

“As of this Sunday last, the Province of Canada has mustered fifty-six battalions of Volunteer infantry for service. There are four organized cavalry regiments, eleven organized batteries of artillery and three brigades of garrison artillery. There are also five companies of engineers available for service. Currently there are also drilling eight unorganized cavalry troops, and a dozen unorganized infantry companies, two further organized battalions alongside one organized negro corps. In total we have 54,000 men ready for duty as mustered by the Province of Canada.” Taché if possible the beamed broader behind his moustache as the tally was rattled off. He had played a creditable role in organizing this force after all and was responsible for overseeing all of it.

“I am most pleased with the news gentlemen. I’m sure London will be pleased as well. Sir William will surely be happy to have such a force at his back.”

“And beside him truth be told sir.” Lysons said. “Taché has led the charge on integrating the militia with the regulars, and Sir William has been most amicable to those plans. We already have one brigade of Canadian volunteers drilling at Montreal, and there are five other battalions attached to brigades within the Army of Canada. They’re splendid men; as good as the Volunteers back home in England.” The Canadians all seemed to stand straighter under such praise.

Monck allowed some of his anxieties to relax. He had expected perhaps less considering Head’s warnings about the parochial concerns of the Canadians, but he was pleasantly surprised by their diligence. Perhaps he had a better chance of keeping things together than he thought.

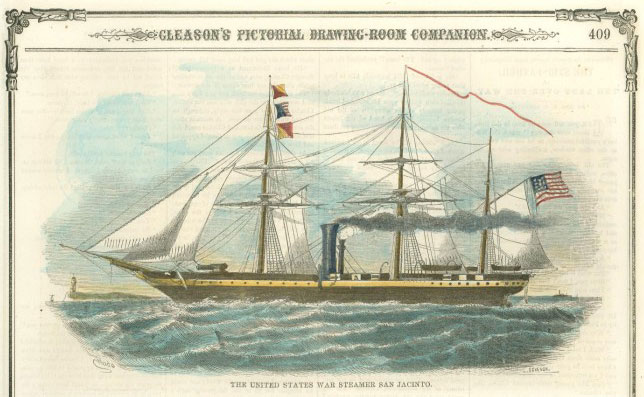

“And how do Captain- beg pardon, Commodore Collinson’s efforts go on the rivers?” Monck asked.

“The ice is breaking up.” Taché said matter of factly “Soon boats will be flowing up the river and our worries about supplies will be partially alleviated. I have authorized the commission of funds for the purchase of gunboats, which we have been doing anyways since February. Many river captains and former sailors in Her Majesties Navy have come forward, and Collinson is putting together a good group of men down at Montreal.”

“That’s a relief to hear Colonel.” Monck nodded and continued on his walk. In truth all this information was going in and out of Williams headquarters at St. Jean where he had moved to a week earlier almost daily. This information came to Monck in his weekly meetings with the chief ministers of the Province, while Lysons acted as the go between for the army, the Provincial government, and the Imperial government in Quebec. The man was doing the work of three men! Monck supposed he should be grateful for learning this much at least, his brief lectures on the last two conflicts in 1775 and 1812 from Taché had taught him that when the going got tough he could expect the military to take over. He hoped to avoid that, he needed the income.

Instead of dwelling on unpleasant thoughts he turned to enjoy the cool air as the first signs of spring crept northwards. The flowers were not yet in bloom, and some snow clung to the shaded areas of the garden, but it was a far cry from the frigid air of March. He fancied riding later in the day.

“I do look forward to the return of spring.” Monck said idly.

“I do not.” All eyes, except Lysons who looked understanding, turned in surprise towards Taché. Galt laughed.

“I understand you might find this climate more to your liking my dear Taché.” Galt said good naturedly “But surely you cannot deny that the warm weather will be far more pleasant for man and beast?”

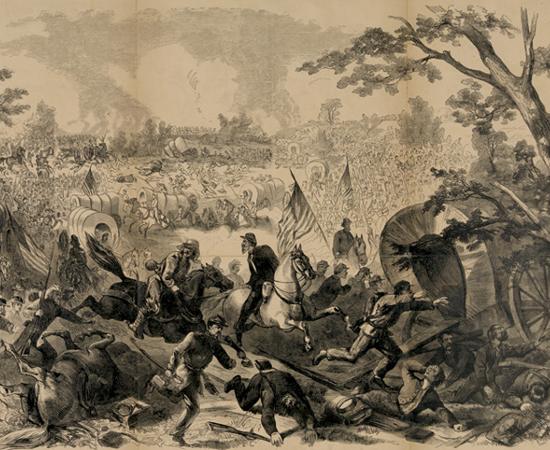

“Oh that I do not deny.” The old colonel replied “The skies clear, the roads dry out, the rivers cease to flood, and it becomes easier to move men and material. It is then though,” he added “that the real killing begins.”

Rivière-du-Loup, Canada East, April 1862

Despite the onset of spring, the winter chill had not yet subsided. Snow clung stubbornly to the ground beneath stands of trees, and where it had retreated, the land was transformed into a quagmire of sucking mud and flooded land. The quiet village of Rivière-du-Loup bustled more than usual, with a company of redcoats in attendance preparing to embark up the Grand Trunk Railway bound for Montreal. The reason for their overland journey was clear as great chunks of ice drifted up the river towards the sea.

In a small cottage near the railroad the men responsible for overseeing this overland movement sat in quiet contentment seeking to keep the chill out. One of them, Lt. Colonel Garnet Wolseley, sat locked in desperate battle against an implacable foe. With a resigned sigh he watched as Major Anthony Home took his queen with a well placed knight.

“Check mate.” Home said with a smile of amusement.

“At what time did you become so good at the game?” Wolseley said scowling “I cannot recall you playing near so well in India.”

“I have had much time to practice.” Home said smiling gesturing to their surroundings. Wolseley snorted.

“I suppose we haven’t had much else to occupy our time when the men aren’t running about. The next batch will be in tomorrow I suppose and then on till the ice melts and the ships start running up to Montreal.”

“Then we can finally go where we will do some good eh Garnet?” Home said resetting the board. Wolseley shuffled to his feet and stretched. The sudden appearance of his manservant, the old file Lough who never seemed to laugh or smile, waylaid him from looking for his Fenimore Cooper novel.

“A message for you sir.” He said.

“Where is it then Lough?” Wolseley said looking curiously at Lough’s obviously empty hands. The man’s face didn’t even change as he replied.

“The messenger is holding on to it sir. He says you will want to see him.” Somewhat irritated Wolseley motioned for the man to be brought in. Lough returned leading a tall man in the fine red coat of an officer of the Queen’s cavalry, the gold braid proclaiming him a lt. colonel. A handsome face grinned at Wolseley from beneath a bearskin cap, the dark brown moustache and mutton chops stretching with his smile as he flourished a letter in soft gloved hands.

“A special delivery from headquarters at Montreal.” Lt. Colonel Soame Jenyns said stepping into the confines of the cottage. Wolseley rushed forward and grasped the other man’s hand firmly in greeting.

“Soame!” Wolseley said incredulously “What the devil brings you out to this lonely quarter of the empire?”

“Precisely what I said.” He replied proffering the letter in his hand. “You’ve got orders for transfer out west.”

“Warmer than here I hope.” Home said from behind.

“Oh where have my manners gone!” Wolseley lamented “Major Anthony Home this is my friend Lt. Col. Soame Jenyns of Her Majesty’s 11th Hussars.”

“A pleasure sir.” The Major said shaking his hand.

“We met in Montreal shortly after I arrived. He’s helping to push the colonials into shape for the cavalry. Which I hope is going better than when we last conferred.”

“Oh they’re all willing and full of pluck, but God knows they have some queer ideas about what a cavalry trooper should do. They’re shaping up though, but there’s damned few enough of them.” Soame said sadly.

Wolseley pushed everyone towards the fire and had Lough bring out some warmed cider as refreshment which Soame took willingly to hand. Wolseley looked over his orders and heaved a sigh.

“Kingston. The last truly important post in all of Canada.” Wolseley lamented.

“You’re on the front lines though,” Home commented “that must be satisfying.”

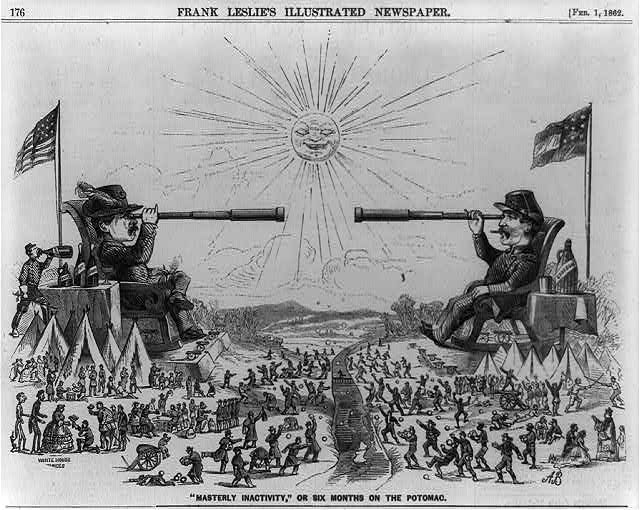

“Oh if everyone there isn’t a prisoner of war by fall that will be satisfying, otherwise I dare say it will be less so. These bloody colonials here in Canada have pluck aplenty, but pluck won’t do enough against numbers, and most of the regulars are in Montreal.” Wolseley sighed.

“And how go the Maritime colonists?” Soame asked.

“Oh Doyle’s chivying them into shape, there’s the rough process of weeding out the old grey beards and getting new blood in, but overall the Bluenoses seem to be taking to it with admirable energy. I hear we’ll have a brigade of them ready come summer if all goes well.” Wolseley said.

“Good for Doyle. He’s the man for the job in those colonies, if it hadn’t been for him we would have been waist deep in snows with nowhere to sleep when I arrived back in November.”

“Doyle’s a good man. Missed any of the fighting after Varna, but he knows his work moving men and material, he’s not battle tested though, makes me glad he’ll be holding the line on the border. With the winter road secure and no Yankees within a hundred miles of our fortifications at Houlton and Fort Fairfield we’ve got secure communications in our rear for the winter unless we manage to make a real mess of things this summer.”

“With Williams in charge…well who knows?” Soame said shrugging. Wolseley grinned and took a drink which Soame shared in.

“He’s no Wellington, but we can hope he’s a Prevost at least.” Wolseley said. Soame raised an inquiring eyebrow causing Wolseley to laugh. “A fellow from the 1812 war. Not inspiring but not wholly incompetent either, though how he managed to waste the advantage of three to one at Plattsburgh…” he trailed off as Soame grinned at him. “Well if this war has no other result, it will at least afford American historians something to write about, and save them from the puerility of detailing skirmishes in the backwoods or on the highlands of Mexico, as if they were so many battles of Waterloo or Solferino.” Wolseley said waving a hand. Soames nodded, and then grinned wolfishly.

“They shan’t make it easy for us eh Wolseley?” That got a roguish grin in return.

“Oh it will be a toughish work, but we are sure to stymy the best they have before they reach Quebec, they couldn’t manage it in 1775 or 1812 after all. If I don’t end up languishing in some Yankee prisoner of war camp this time next year I’ll wager you on it.”

“What’s the wager?” Soame said, favoring him with a grin.

“That horse of yours.” Wolseley said. Soame burst out laughing.

“Perhaps another wager! You wouldn’t want to separate a cavalryman from his mount would you?”

“I’ve always thought the cavalry could use some humility on occasion, perhaps riding into Montreal on a mule much as our Lord Christ did so long ago at Jerusalem would serve that purpose.”

“Sir those are fighting words!” Soame said with mock severity and Wolseley grinned.

“Then thank God I’m a fighting man, for its fighting men we need! Come then, I’ll have Lough bring us some dinner before I set to packing my things, then maybe we can see about finding something nicer about this part of the Empire before I’m shipped off to the edge of the earth.”

----

Well here's one last one before Christmas! Hopefully I can crank out another before the New Year but I'm not so sure! Hopefully it's enjoyed and we will get back to the meat of things in a dew weeks time