In that case then they should be pretty weak ships, but they'd be possible to build by that point.

Well it's working with the understanding they had historically, and absent the understanding of

Monitor's problems in March 1862, I don't think they would leap immediately on to the ideas for the

Passiac Class. This would be within the Union's capabilities to build quickly.

I'd be surprised if shell could pierce 3" armour before the days of the Palliser. I'm sure Galena was penetrated by shot - in fact, it's expected - but you should note that Galena was able to fire off all her ammunition at Drewry's Bluff and retire in good order. This is because the shot pierced, but that still makes it less effective than a cannonball fired into an unarmoured sloop - and a dozen such cannonballs couldn't really render a sloop into a sinking condition, it's only a few 8" diameter holes and her crew is materially intact.

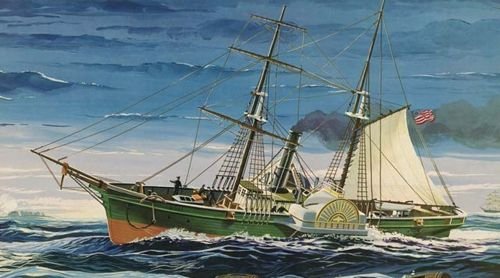

Galena anchored 550 meters away from Fort Darling, and suffered 44 hits in 3 hours and suffered 13 penetrations of her armor, alongside 13 dead and 11 wounded. If that kind of damage can be accomplished from long range, at close range with a gun just as heavy (and more of them) I would say that damage dealt should be debilitating to such a bad armor scheme.

Actually, Monitor is not absurdly low in the water. Her freeboard is low, but her turret is actually quite high - as high as the sides of a typical ship - and the pilot house is similar. And only a couple of dozen hits on her turret is more than she can endure and retain any kind of fighting capability (out of about 3-400 shots fired at her).

Neither the turret or the pilot house is backed. The resistance is between 10 and 20 foot-tons per inch, and the 68-lber simply has too much energy density to be adequately stopped. Even allowing for the inevitable underperformance of guns in battle as opposed to in tests, the 68-lber shot hitting anything of Monitor which is above the deck will be producing heavy spall and shattering multiple plates per hit.

Note that I don't argue that either ship would be put in a sinking condition - Monitor's waterline is very well protected - but that the exposed turret and pilot house of Monitor would actually be more vulnerable to damage than the exposed body of Galena shot-for-shot because the Galena has backed armour.

The damage might be enough, but that's assuming all good hits, and

Monitor's very design does a good job of protecting her from a broadside. Lot's of wasted shot by

Thunder, but eventually it will batter the ship into withdrawal.

Now I'm not good with mathematical equations, but with

Monitor being a small target, and only a few of

Thunder's guns able to hit anything of consequence on her, I would argue that statistically over an hour or so of fighting

Monitor would suffer fewer hits than you imagine, even in ideal conditions. Over time though these hits will add up and force the ship out of action. I don't think though, that it is possible to predict such a thing with any degree of certainty.

Galena, being a larger and more vulnerable target, is in a much worse position. She's got a better profile for a broadside to hit, and her armor is too thin to prevent penetration on most of those shots. A few hits at or below the waterline and that's all she wrote.

In short, Galena's weaker armour doesn't mean she should be rendered into a sinking condition so quickly, and Monitor's stronger armour doesn't mean she'd be able to last so long before deciding to retreat.

The problem Monitor has is simply that her armour is not thick enough to prevent "terminal effects" (i.e. damage to the armour scheme) and that she has so little redundancy in her fighting capabilities above the freeboard (i.e. everything that sticks out of the deck is vital) so she'd be quickly disabled and sunk.

Sinking her would be harder, since the turret can't really sink, and if its bashed out of joint the ship will just withdraw, and

Thunder can't really pursue in this instance. I don't quite think that with her design a broadside boat is going to be able to cause as much damage, and the scenario in this battle precludes any pursuit if she withdraws.