As an aside I've just been making some minor adjustments to the chapter headers, but War Means Killing Pt. 2 premiers tomorrow...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wrapped in Flames: The Great American War and Beyond

- Thread starter EnglishCanuck

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 169 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 136: We’re All Americans Chapter 137: Baltimore Blues Chapter 138: Wars Averted Chapter 139: The Man Who Would Not Be Washington Chapter 140: Muerte de un Presidente Chapter 141: A Gentleman Abroad Chapter 142: The Election of 1867 Chapter 143: An Imperial Democracy

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 2

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 2

“I have taken sides with the King my father, and I will suffer my bones to bleach upon this shore before I will recross that stream to join in any council of neutrality.” – Tecumseh in response to an emissary from General Hull, 1812

“The invasions of May under Charles F. Smith’s Army of the Niagara had driven the Anglo-Canadian forces under Dundas from their prepared positions on the frontier, delivered sharp blows to the Canadians on the frontiers at London and Fort Erie. Despite this the advance across the St. Lawrence had been checked at Doran Creek, and the advance had been briefly checked at Lime Ridge before Smith had boldly maneuvered them out of their positions. This had led to the gradual fall of London, Hamilton and Toronto, depriving the Canadians of major centers of industry and bountiful resources which could have been used in the war effort.

For all these successes though, the Union army had largely been eating the dust of the Anglo-Canadians as the British retreated northwards towards more defendable positions. Dundas had, to the great dismay of his Canadian officers, abandoned the positions at Toronto, and headed east across the shores of the Lake Ontario in search of a more secure position further north. The first act was a long march from Toronto to Port Hope, keeping pace with Bythesea’s squadron which helped escort the supplies needed to sustain the forces under his command, while scooping up the militia garrisons to pad out his own forces…” For No Want of Courage: The Upper Canada Campaign, Col. John Stacey (ret.), Royal Military College, 1966

Kingston Harbor, 1860

Since the 1812-1815 war neither side had maintained a serious presence on the northern lakes. However there had been great changes in the nature of shipbuilding and industry. The Rideau, Welland, Genesee, and Erie canals made the problems of transporting ships and materials across the landward and riverine barriers far less difficult than they had half a century ago, and even helped connect the lakes with the Atlantic…

…American industry along the shores of Ontario was not what it had been in 1812. In the forty years since our settlement along those shores had grown from small isolated trade villages, to bustling and industrious towns and cities with canals and railroads that connected them to the industrial heartlands of New England. The rail head at Syracuse was well placed to provide for the upkeep of the existing yards on Lake Ontario, and the surrounding cities such as Buffalo, Rochester, and Oswego where supplies could be readily furnished for the construction of a fleet.

On the Canadian shores the population had grown, but nowhere near as exponentially as that of the neighboring states. There were still bustling cities of industry and trade where new facilities could be expanded upon. The city of Kingston, much larger than her 1812 population with 13,000 inhabitants remained the center of Canadian shipbuilding on Lake Ontario, but the town of Hamilton with its 23,000 inhabitants, good harbor, and excellent industrial output was fast catching up to the old citadel of the west. Able to draw on the burgeoning industry of cities like Toronto, London, and Guelph it was well supplied to lay down new hulls and produce new ships and even engines at need.

Unlike in 1812 the where the Canadian shores had been longer settled and its inhabitants more accustomed to riverine and lakeside navigation, in 1862 our shores were teeming with men and industry. While the population of Canada West was 1,300,000 souls all told; the population of neighboring New York State by itself was some 3,800,000 souls. This outnumbered the combined population of the Province of Canada (2,500,000) by a considerable margin. The sum total of the frontline states in the northern theatre on Lake Ontario and the Canadian Border (New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine) numbered 5,100,000 versus 3,100,000 in all of the British North American possessions on their borders. This total increases to several million souls if one counts Michigan and Wisconsin1, this ought to put in perspective the imbalance of forces which existed in the early days of the conflict, between the Anglo-Canadian efforts and those of our own on those waters in 1862.

This imbalance seems even more in evidence when one considers the tonnage of shipping on the Lakes when compared side by side as it existed in 1861:

Summary Tonnage of United States Shipping on the Lakes: 223,953

Summary Tonnage of Canadian Shipping on the Lakes: 75,658

Now one must keep in mind that even so the vast majority of shipping on the Lakes was tied up in sail vessels such as barques, brigs, and schooners which plied the majority of the trade, especially that between the lakes along the Erie or Welland Canals, and these vessels were wholly unsuited for warlike purposes. A contrast of the summary tonnage of steam vessels on the Lakes paints just as stark a picture however:

United States Steamship Summary Tonnage:

Screw: 50,018

Paddle: 42,683

Canadian Steamship Summary Tonnage:

Screw: 4,562

Paddle: 21,017

As awesome an image this does paint, it is also slightly misleading.

The preponderance of Canadian shipping existed on Lake Ontario in 1861[1], and the previously listed tonnage was found largely plying its waters. These lists also bafflingly exclude Canadian ships which plied their trade from Montreal to Kingston along the St. Lawrence which though not granting any superiority in tonnage to the Canadians, make the numbers far less unenviable than they would first appear. The truth was that while we had the greater number of steamers the Canadians possessed a larger number of steamers which numbered over 400 tons. The other reality that pure numbers are unable to tell is that of the predicament of our Navy on Lake Ontario in the months between the outbreak of war with Britain.

At the start of the rebellion in the South the Navy had been well aware of the need to rapidly expand its resources in order to enforce a close blockade of the rebel coastline to interdict his trade and coastal commerce. The Navy in April of 1861 simply did not possess enough ships to carry out this task and as such began to draw upon all the resources available to it and more. Chartering or purchasing steamers on both Lake Erie and Lake Ontario for riverine and coastal warfare five of the six United States Revenue Cutters on the lakes were sailed to New York where they were discovered to be too small for their intended purpose. They then turned to lake steamers as a source of hulls in the coming conflict. A number of American steamers were chartered from Oswego, Rochester, and Ogdensburgh, as well as some from Kingston, Toronto, and Hamilton.

The problems with purchasing British vessels can be explained well with the story of the steamer Peerless. About the beginning of May, 1861, she was purchased by J. T. Wright, of New York, from the Bank of Upper Canada, for $36,000. On May 10 she left Toronto, under command of Capt. Robert Kerr. On May 27 she reached Quebec, where it was ascertained that under British laws she could not sail for a foreign port without an Imperial charter, which the officer at Quebec could not give, as she was owned by an American. Mr. Wright thereupon made application to the American consul at Quebec for a sailing letter; but this was declined on the ground that the vessel might be destined for service in the navy of the Confederate States. Mr. Wright was finally enabled to get this vessel out of port by giving heavy bonds that the Peerless should not be used for war-like purposes, and she was allowed onwards on condition that Captain McCarthy, a native of Nova Scotia, but a naturalized citizen of the United States, should command her. It was in her service to our Navy that she would be recaptured by the British in July of 1862 and returned to Canadian waters as a prize.

Such a story helps explain why it was readily preferred to charter or purchase American hulls rather than those belonging to a foreign power. This however, had the effect of diluting the potential strength of any emergency squadron which could be thrown together on Lake Ontario by the Navy in 1862. In this respect it is fair to maintain that the United States did not carry a substantial advantage in terms of ships immediately available to them when war struck in February of that year.

This was made worse by the stipulations placed upon them by the Rush-Bagot Treaty. The Treaty had been signed as a show of good will between the two nations in order to ease post war tensions, and as a much needed cost saving measure for both sides. Proposed by Acting Secretary of State, Richard Rush and British Minister to Washington, Sir Charles Bagot it stipulated that the two nations would not furnish more than a single vessel not to exceed 100 tons burden, and armed with only a single gun not exceeding eighteen pounds on either Lake Ontario or Lake Champlain. It was, with some naivety, hoped that this could lead to the demilitarization of the frontier between the two nations, and prevent an arms race on the lakes.

In keeping with the spirit of the Rush-Bagot agreement of 1818 there was no official presence by either the Royal Navy or the United States Navy on Lake Ontario in 1862. However, much like on Lake Eerie, the treaty would not bind the two sides as greatly as they might have wished. The British had been the first to push the limits of the treaty in 1837 in response to the patriotic uprisings in Canada West (then Upper Canada). Civilian ships were hurriedly purchased and armed and used against the Patriot raiders and rebel crossings on the lake and lower Saint Lawrence. The British swiftly converted a number of steam merchantmen to gunboats, but afterwards began the construction and arming vessels of war such as Minos and Cherokee which the United States saw as a violation of the treaty prompting the construction of the Michigan. These vessels though were scrapped in 1853 when the British decided to decommission them in order to cut costs associated with the garrison in Canada. The British however had decided not to leave events to chance on the lakes and had begun in the late 1840s with the construction of three 400 ton iron steamers; Kingston, Passport, and Magnet which could in an emergency be armed and manned by the Provincial Government. These formed an important nucleus around which an emergency squadron could be furnished in times of need.

On our own shores no such measures existed. No plans had been made for a sudden outbreak of hostilities with Britain upon the Lakes despite tensions in 1838, 1842, and 1844. The Navy Department had not seriously considered any measures in their defence, nor had it consistently kept up adequate supplies for any sort of emergency which might break out. Nor had any effort been expended in an effort to provide for a secure yard in which to shelter a squadron which might be created. Unlike the works at Kingston which had been expanded upon and modified throughout the half century leading up to the renewed conflict, the defences in Sacketts Harbor had been allowed to decay into a state of ruin, while the fort which would protect Oswego was incomplete and unarmed at the outbreak of war. Rochester and the Genesee River had nothing to protect them from a sudden descent out of the harbor at Kingston or Hamilton. It is fair to declare then that we suffered from a disadvantage at the start of the conflict on the Lake.

However, in the immediate outbreak of war neither side could do the other any great damage. The lake was resolutely frozen until the arrival of the thaw, and even then navigation would be hazardous until the full thaw of summer drove the lingering ice away. In that time each side prepared itself as best it could…

1[ Considering the distance and sparse material value provided by these states to the conflict on Lake Ontario I do not.]

” The Naval War of 1862, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., New York University Press, 1890

“…the time between the declaration of war was spent in a state of frantic activity from Montreal to Hamilton by both the Imperial Government and the Provincial authorities inside Canada. They were faced with a situation much like that which existed in 1812 and 1837 with the threat of looming invasion hanging over all.

The Provincial government had been the first to act in December with the chartering of the tug St. Andrew and the steamer Huron (armed with 2 and 4 guns respectively from Quebec) to patrol the St. Lawrence between Montreal and Lake St. Francis. The Admiralty in London had been next with the dispatch some junior officers, a number of shipwrights and clerks, and a company of Royal Marines at the end of the month who took the arduous overland journey to Kingston tasked with reopening the dockyard there.

The reaction of the local population on the lake shore was supportive of the effort to rearm with volunteer naval companies forming at Garden Island, Kingston, Toronto, Hamilton, Dunville, and Port Stanley in January of 1862. Men offered up their ships, and in return the government offered commissions and charters to those who would serve. An ad-hoc naval school was established at Kingston in February where men of the merchant marine went to learn something of naval warfare from the men of the Royal Navy. There were however, precious few men of that pedigree to go around, but a number of officers would present themselves at Kingston and Montreal to form the nucleus of the riverine squadrons that would endeavor to protect Canada from invasion.

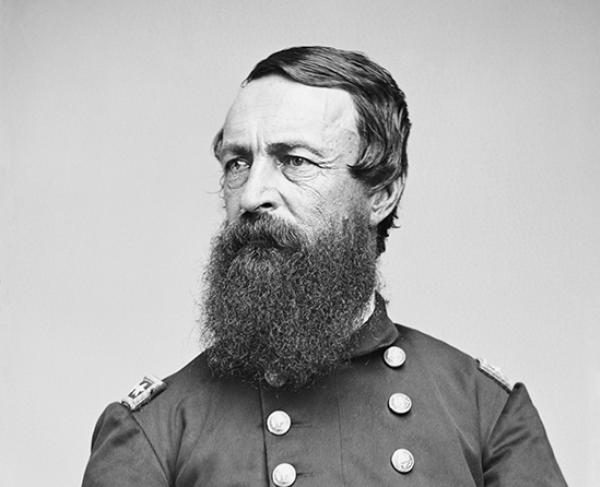

In February the officer the Royal Navy had appointed to take command of the emerging squadron on Lake Ontario arrived, Captain John Bythesea.

Bythesea had entered the navy in 1841 serving as a lieutenant aboard HMS Arrogant in 1850 and aboard her in the Russian War. It was there he earned the Victoria Cross for his actions on Vårdö capturing Russian couriers carrying important despatches to the fortress of Bomarsund. He was then given independent command of the paddle gunvessel HMS Locust in the Baltic where he would pursue Russian merchantmen and help strangle their coastal trade. In the aftermath of the war he was promoted to commander and took command of the 11 gun sloop HMS Cruizer in March of 1858 in station off China where he participated in the Second Anglo-Chinese War in action off the Taku Forts in May and surveying the Gulf of Pechili to pave the way for the allied landings on the road to Peking. Returning to Britain in 1861 he had been scooped up for particular service as the crisis deepened. Dispatched in late March he had been expected to make something of the men and material available to him, in this he would not disappoint…” Defending the Seaways, Canadians on the Lakes and Rivers in the War of 1862, Donald Glover, Royal Military College, 1972

Captain Bythesea

“…despite a severe degree of pessimism prevalent in the Navy Department regarding the ability to seize control of the lake on the outbreak of war Welles acting quickly began to make preparations for the formation of a squadron[Footnote: This more due to the suddenness of the blows inflicted by the Royal Navy and the perception of lacking preparation versus any inability on the part of the Navy itself]. This formation’s duty would be to contest any squadron assembled by the British at Kingston and to support the Army as it moved into Canada West. However, the realities of our own unprepared state prevented any coordinated plans between Army and Navy from being attempted on Lake Ontario unlike those on Lake Erie. The War Department, not placing any great faith in the naval establishment on Lake Ontario come spring, decided to place its trust in the superior numbers of our army to win the day and avoid any interference which might be forthcoming from the British squadron on the lake. It was however known, and expected, that the two forces would be required to work together come the fall of Toronto, as the army then could no longer avoid marching along the shore, and the navy would need to secure the west end of the lake.

Selecting a commander for this new force was found to be of some difficulty. Many men with previous experience were already enrolled in the navy on the Atlantic at the outbreak of war, and thousands of seamen had been killed or captured by the British in the opening stages of the war. Then the results of the Battle of Key West gave birth to an officer who was fired with a desire to bring the fire of war to the British on land and sea, and in Commodore David D. Porter was a suitable commander found.

Porter was the son of Commodore David Porter, who had also fought against the British in the 1812 war, gaining acclaim for his actions in the Pacific. Porter had followed in his father’s footsteps, serving briefly in the Mexican Navy before fighting against in the Mexican War with distinction at Vera Cruz and Tabasco. In his service he had earned a reputation for arrogance and insubordination, but his conduct was buoyed by his fertility in resources and great energy. However, he was impressed with and boastful of his own powers and given to exaggeration in relation to himself, a infirmity of the Porter family. However, it had served him well in his command of Powhatan. He had been selected to take part in that expedition to relieve Fort Sumter, and his own zealous nature had impressed Lincoln. His relation to the daring Farragut, who had recommended him, earned him the position.

Porter’s headquarters were established, not in Sackett’s Harbor as Secretary Welles would have preferred, but at Oswego at the mouth of the Oswego River. With its population of 16,000 and good rail and river connections with the rest of the state it was a superb choice for the nucleus of a new naval yard. He would work with Halleck to build up Fort Ontario to protect his yard and the city from any sudden descent by the British. He was made secure by the men of the 24th New York Militia Brigade under Brigadier General Elson T. Wright.

However men and material would be needed to supply this squadron. Men could furnished in abundance to man the emergency auxiliary gunboats the Navy could prepare, but material was another matter. Just as the search for hulls had stripped the lakes of many larger vessels so too had the need for guns to arm them with and the shell and shot to sustain them deprived the already meagre arsenals on the lake shore of substantial armament come the outbreak of war. That which remained was either in poor shape or of inferior quality, and new weapons were in demand all along the coasts and inland rivers. What could be spared was diverted though, and new guns were cast in the arsenals of New England as winter gave way to spring.

The nature of this new squadron though, was contentious. It has been generally accepted that only heavier steamers were suitable for handing larger guns and that the equipping of steamers less than 300 tons would result in serious damage if provided with a heavier modern armament.

The greatest concentration of American owned steamers lay at anchor in Ogdensburgh where there were several steamers suitable for the purpose of conversion into gunboats, but come February they were completely trapped in the ice on the St. Lawrence, and potentially at the mercy of the British and Canadian soldiery on the other shore at Prescott safely ensconced behind the works at Fort Wellington. However, in the lead up to war, the owners of these vessels had feared for their safety, and in a great risk broke them through the encroaching ice to sail them to Oswego where they could be more safely stored. It was these vessels that porter worked to refit into vessels which could take the fight to the British alongside those at Rochester under the command of his chief lieutenant, Lieutenant William “Bull” Nelson.

Fully assembled at Oswego Porter now had ten ships totalling 4,855 tons available to him with 30 guns, he broke his flag on the hastily reassembled 832 ton Ontario carrying 6 guns. The remainder of the squadron was organized thusly:

Bay State(4), Buckeye(2), Cataract(4), Cleveland(2), Empire(2), Genesee(2)2, Northerner(2), Prairie State(2)

On the slips at Oswego were building two tinclad vessels, the Oswego, and Scourge. At Rochester was building the Sylph. These three ships had been laid down at the end of March as facilities became available, and unlike the current squadron these would be purpose designed warships which would enhance our squadron and give it an edge over the British vessels which were assembling at Kingston.

At Kingston the British under Captain Bythesea were also arming. The sheltered port in Navy Bay and the superb harbor at Kingston itself, as well as good anchorages all along the north shore and at Garden Island gave them ample ground to retrofit their merchant ships, and the arsenal at the Stone Frigate contained many good weapons, and further were shipped inland from Quebec and Halifax as the spring wore on and navigation along the St. Lawrence opened up. They however faced the same difficulty in creating a scratch fleet as did we. They also had the majority of their vessels scattered across the breadth of the lake, but with a majority at Kingston and some at Toronto and Halifax.

Bythesea had the full cooperation of the garrison at Fort Henry in this undertaking, the town major and brevet Colonel Hugh P. Bourchier was fully committed to the fight on the lake. Bourchier had originally come to Canada with the 93rd Regiment of Foot in 1837 and had seen firsthand the necessity of organizing even a scratch naval force on the lakes thanks to the events of 1838. Coal, guns, and ammunition were Bythesea’s if he needed it, and the cooperation between the two was superb, greatly aided by Bythesea’s service in China and his ability to cooperate with the Army. That the Stone Frigate was under the authority of the Provincial Marine (and by extension the Royal Navy) and not the Army or the militia made a competition for its resources unlikely, and the relationship between the two men would be pivotal in the opening months of the conflict…

With his squadron in place at Kingston, Bythesea broke his flag on the 432 ton Kingston(6) and had at his command a squadron of eleven ships totalling some 5,214 tons with 43 guns organized thusly:

Algoma(3), Banshee(3), Champion(3), Empress(4), Europa(4), Hercules(2), Kingston(6), Magnet(6), Passport(6), St. Andrew(2), Zimmerman(4)

As such in the opening stages of the war one can see that the British held quite the advantage over us in tonnage, guns, and ships. This was made even worse by the arrival of the Russian War era gunboats HMS Raven(4), Leveret(4), Thrasher(4), and Decoy(2), on May 21st bringing the total tonnage on the British side up to 6,121 tons and 57 guns…

…Bythesea’s audacious assault on Porter’s flotilla at Hamilton had caught the navy by surprise, but it did not significantly hamper the fall of Toronto. While the action had been bloody, for the loss of Empire and Genesee on our own side and Europa and St. Andrew on the side of the British, it had done little to change the equation on the waters of Lake Ontario. The fall of Toronto had disheartened the Canadians, but Dundas would allow no shirking in his army and punished deserters accordingly. He was concerned though that Smith could once again turn his flank by an amphibious landing. Moving in concert with Bythesea’s squadron he sought to prevent that by finding a piece of terrain which would allow him to anchor his flank as well as protect the fleet…

2[Formerly the SS Ontario, but rechristened to avoid confusion with Porter’s flag]

” The Naval War of 1862, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., New York University Press, 1890

David Dixon Porter

“The journey northward had seen little beyond minor skirmishing and isolated rearguard actions. Smith had been perennially delayed by the need to garrison the territory behind him, which proved more difficult than anticipated. His own forces had been depleted by battle and the exertion of campaign, and the promised militia brigades had failed to appear to garrison his rear, the expectation that the populace would be quiet had proved in error, and the lack of naval supremacy dictated a cautious overland approach by X Corps towards their ultimate goal at Kingston. The Army of the Niagara found itself stretched thin as it pursued Dundas’s men, and while at the outset of the campaign it had numbered 34,000 men it now numbered only 28,000, minus Ammen’s division which still sat astride the St. Lawrence tying down the Canadian militia there.

Dundas, had actually strengthened his forces, but suffered desertions as the retreat saw men return to their homes to care for their families in the face of an invading army. Dundas dealt harshly with this, branding or lashing any who were caught trying to escape. As his discipline grew harsher his forces scooped up the men protecting the rear areas, growing in size to over 18,000 men. This had created a very top heavy force, as he had absorbed the militia officers and staff into his own organization, and he was required to find some use for them. Many staff members were attached to the cavalry units, while others were assigned to supplies, others simply expanded Dundas’s staff, but as one British officer would complain “we have an influx of useless mouths which never tire of opinion.”

Even upon arriving at Cobourg he was fearful of some assault upon his rear and withdrew to behind the Trent River, emplacing himself at Port Trent. Here he had withdrawn behind the Prince Edward Peninsula, placing his flank squarely on the Bay of Quinte, and preventing a landing from taking him in the rear. The Bay of Quinte could easily be controlled by the gunboats, which would either have to be bypassed or engaged to prevent them from falling on any American naval convoy going towards Kingston, and offered safe harbor. Dundas began to dig in here, establishing a fortified position on the grandiosely named Mount Pelion which rose 191 feet above the surrounding area allowing for artillery support, and protected the bridge crossings into Port Trent itself. Behind this position his engineers established a tete-du-pont supported by a pontoon bridge which could evacuate his men if necessary, and hold off any attempt at an American crossing.

His supply lines were secure thanks to the Grand Trunk Railroad and the Rideau Canal stretching back to Kingston and Ottawa. However, other than supplies of food and water which could be drawn from the local population, everything else had to be shipped to the depots at Montreal, and from there up the Ottawa River, and down the Rideau Canal to Kingston and from there across the railroad to Port Trent. Ammen’s brigade, which raided up and down the length of the St. Lawrence with near impunity, had effectively cut the rail link directly to Montreal.

Smith faced a logistical challenge just as severe. He was now deep in unfriendly territory, and though the populace was largely quiet in the summer months with the needs of the farms, bands of guerrillas preyed on his supply trains, and he was responsible for garrisoning the region now as well. His supplies all had to come from factories and depots in the United States, and travel either by rail or by barge (which was safer) to reach his army over 200 miles from Buffalo, or travel nearly 100 miles across Lake Ontario to Port Cobourg, which he occupied August 9th. Here he rested his men, made his supply lines secure as he could, and took stock of his situation.

As he feared he could expect no naval support from Porter in this attack, and the position on Mount Pelion was formidable. With the memory of the assaults at Lime Ridge in mind he balked at a frontal assault on Dundas’s position, realizing he could not risk the casualties. Instead, he sent his cavalry under Col. Bridgeland scouting the river banks. Though at first anticipating being able to feint around Dundas’s position as he had at Lime Ridge, he soon discovered the river (which grew wider as it led north) led only north to the fastness of the Madawaska Highlands, and even a flanking march there would leave him open to attack with little hope of successfully re-establishing his supply lines. However, Bridgeland informed him that only 7 miles distant the bridge at the town of Frankford stood, and seemed guarded only by a small number of militiamen. Smith sensed an opportunity…” For No Want of Courage: The Upper Canada Campaign, Col. John Stacey (ret.), Royal Military College, 1966

----

1] This comes from reading the British recommendations for the defence of Canada, which includes a summary tonnage of all the vessels under Canadian and American registry on Lake Ontario. Similarly my conclusion that on Lake Ontario most of the Canadian steamers are in a greater tonnage from their American counterparts comes from reading the insurance registry of shipping from 1864. That one surprised me as it showed a rough parity in vessels with suitable tonnage for warlike purposes, with a slight Canadian advantage.

This one is a bit of a longer one, so I split it in two. I really wanted to get as much of the preliminaries for the naval stuff on Lake Ontario in as I could so it's not all smashed together at a later date. The big fight takes place tomorrow so I would recommend people refresh themselves a bit by reading the Appendix to the campaigns from May - June in Canada. I'll fill you in on any changes that take place, but until then, stay tuned!

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 2.2

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 2.2

“The Six Nations had contributed some 300 warriors to the British cause on the outbreak of war. Most of those who volunteered had fathers and grandfathers who had fought for the British in 1812, and a few had even fought Mackenzie’s rebels in 1837-38, however most were young men excited for their first fight, or because they had heard rumours that the invaders intended to confiscate their land.

They were led by their chief William Simcoe Kerr who spoke for their interests and had inherited a political savvy and amateur military spirit from his father. William was the son of William Johnson Kerr, the Indian Agent and officer who had led the Six Nations warriors at Queenston Heights and Beaver Dams against invaders in 1812 alongside such notables as John Brant and John Norton in that war. He had also been an ardent anti-reformer, leading a company of volunteer warriors against the rebels in 1837-38, infamously he had been prosecuted for assault against Mackenzie himself in 1833. This anti-reform (and by extension anti-American) attitude had been inherited by his son, who had used his influence to lobby for arms and equipment for the men sent to serve alongside the Crown forces…

…Kerr’s warriors had largely served as scouts and piquets alongside the British during the opening stages of the invasion. Kerr had seem some action at Lime Ridge, skirmishing with the American scouts, but largely they had served as Auxiliaries, and Dundas had been glad to use them. By the time of Mount Pelion they had earned their reputation as warriors…” The Six Nations in the War of 1862, Aaron Brant, University of Toronto, 1963

Six Nations veterans from the War of 1812

“Dundas had reorganized his command upon digging in at Port Trent. Napier’s 3rd Brigade had been reorganized on the march, Col. Brown had been killed at London, and the militia troops who had formed that brigade had largely disintegrated. The new brigade was formed from the former London garrison (56th Volunteer Rifles), with a new battalion (59th Volunteer Rifles) formed from the remaining militia companies from Toronto, while the 40th from Port Coborg was attached, and the 33rd Battalion, the only militia battalion which had remained in a semblance of readiness, was attached to these battalions. Col. Denison of Toronto was placed in command on the recommendation of the Imperial and Canadian officers, as he was judged fit to command the battalion. Though Dundas would have liked to replace Napier, political and seniority reasons prevented him from doing so, and so he would remain commanding the 2nd Division. He did choose to fix Dundas’s men in a “safe” position holding the bridge at Frankford.

He held the former Hamilton garrison brigade under Col. Booker as his overall reserve, alongside Macleod’s 3rd Dragoons for a quick reaction force. Booker’s men were relatively fresh, having seen little heavy action save for some skirmishing at Lime Ridge, and in the various rear guard actions on the retreat from Toronto, and so could be expected to act in support of any American breakthrough.

The 1st Division under Rumley was strengthened by the addition of new battalions into the brigades including the 46th from Port Hope under the “Boy Colonel” the 25 year old Arthur T. H. Williams, which were already strong. The 1st Brigade (now known as the York Brigade) under Maulverer, would act as the division reserve, while the 2nd and 3rd Brigades under Ross and De Courcy would hold the line.

De Courcy was placed on the fortified position on Mount Pelion itself. Gun positions were erected, and rough breastworks were thrown up near the summit. Ross’s brigade held the flanks which stretched back to the Trent River. In total 3 miles of crude field fortifications held the line Dundas had established resting their flank on Dead Creek…

Mount Pelion after the turn of the century, with the modern battlefield marker.

…Smith intended not to allow Dundas to become too comfortable. Bridgeland’s scouts informed him of the relatively lightly defended crossings northwards at Frankford, and so, on the night of August 14th, Smith began to move Prentiss’s 3rd Division northwards, using the Quinte Hills to screen the advance. However, in unfriendly country, it was impossible to hide the movement. Locals, and Kerr’s Indian scouts, spotted it and reported it to Dundas. Dundas, fearing that this was a prelude to a crossing near Frankford, moved Booker’s brigade north, pulling Maulverer’s York Brigade behind the river in case they needed to march north in a hurry.

Skirmishing began on the afternoon of August 15th and it was reported to Dundas, who held back, as he also received skirmishing to his front. Remembering how he had been outmaneuvered at Lime Ridge he decided to wait. His choice was fortuitous.

Though Smith had moved most of Prentiss’s division north, he had kept Turchin’s men back, adding them as a 3rd Brigade to Palmer’s division. He had realized that even if he forced a crossing to the north, Dundas could counter him by moving the bulk of his men to assault a lodgement on the far side. He needed to punch through where Dundas might not be prepared. The construction of the British pontoon bridge had sealed his choice. Risking his slim numeric superiority he had concentrated 16,000 men against Rumley’s 8,000 in the hopes of forcing the British across the banks. He gambled on being able to seize the bridges and drive back the British lodgement, while pulling Dundas’s reserves north to deal with the non-existent threat from Prentiss.

The heavy guns of X Corps opened up at 11:37 in the morning on August 15th. A half hour artillery duel erupted, which caused disarray in the British lines as the heavy guns hit the forward positions, save the batteries emplaced on Mount Pelion. Then, Palmer’s Division advanced, his 1st Brigade towards the center, and his 2nd towards the left flank while McArthur’s men moved on to the right flank.

The key to the field was Mount Pelion as Smith said “That hill is the key position and must be taken. From there we control the field and the crossings and I must have it.”, and the British had spent many days clearing trees and creating good fields of fire at the summit for the artillery. The base of the hill was still well forested, which meant that when Palmer’s 1st Brigade under Slack arrived at the base at 12:44, they were well protected from artillery. Too late did the Canadian gunners discover that in their efforts to dig in the guns that they had emplaced them so they could not be depressed far enough to fire downhill, so when Slack’s Indianans, who had helped break the militia at London, charged upwards, they were unmolested by cannon fire. Only a single battalion held the summit, the 30th Volunteer Rifles, and they panicked at the sight of three regiments charging for the summit. They were soon running, their courage failing them.

However, they ran past the Upper Canada Colored Corps under Major Charles C. Grange. Grange had entered the military in 1843, originally serving as a militia officer from Canada West, he had commanded men in 1837-38 and had been present at the Siege of Navy Island. He had enrolled in the British forces in 1843 as an ensign, serving in in the Gambia, and commanding detachments from the West Indies Regiments in 1849. Like most Canadians he was an abolitionist, and his service with the colored men of the West Indies Regiments had made him a natural choice to lead the 400 men of the Colored Corps. Formed by men who had settled in Canada, the grandsons and sons of former slaves from the United States, and even former slaves themselves, they were eager to serve the Crown which had offered them safety. They had largely been detailed to pioneer work, and had been working to clear trees and construct roads on the march, and even here had largely been carrying ammunition to the summit, but when the call came men threw down crates of ammunition and grabbed their rifles.

As the 30th ran down, the colored troops ran up to aid the few brave gunners who had stood with their guns. When the Indianans reached the summit they were met by a cheering mob of red coated black men who met them head on as they attempted to scale the breastworks. After a few ragged volleys a furious melee erupted as men fought with bayonets, knives, swords, and clubbed rifles. It seemed that numbers would tell, until De Courcy arrived with the remnants of the 30th and men pulled from the line on the flank. Slack’s brigade was soon retreating down the slope to cheers from the Canadians, black and white.

The brief respite was used to rearrange guns, and reform the breastworks as best they could. Slack’s brigade was soon reinforced by his new 3rd Brigade under Turchin at 1:40. Turchin’s men were ready to repay the Canadians for the repulse at Stone Church, and they joined Slack’s men as they headed back up the hill. Trees and rocks impeded the Canadian fire, and like before the Americans made it to the breastworks at a run. The fresh men gave an extra weight to the charge, and they cleared the breastworks, intending to capture the guns. Despite the bravery of Granger’s men, and the rallied men of De Courcy’s brigade, the Canadians were driven back, and the Canadian guns were captured. However, De Courcy rallied his troops for a counter attack, and they managed to push Turchin’s men away from the guns in a running fight. The unexpected ferocity of the counter charge again pushed the Americans to the base of the hill.

Both sides would regroup and reorganize for a precious hour as the exhausted men sat and waited.

On Ross’s flank, McArthur’s men under the one armed Irish Col. William Sweeney in engaged the Canadians of Col. Ross’s brigade. Though the defenders were entrenched, they were stretched thin, and Sweeney’s men made significant headway against the defenders, reaching the earthworks on their first rush. Hand to hand combat ensued, but near point blank fire from the guns drove the first assault back, with significant losses on both sides. However, a second attack, with the uncommitted men of Pugh’s brigade gains traction. Ross’s men were steadily pushed back as the numbers begin to tell.

Dundas was forced to commit the reserve his line beginning to buckle under the strain, and he ordered the York Brigade forward. The York militiamen, who had fought so hard at Lime Ridge and supported by the only battalion of regulars on the field, take the line. They quick march to the flank where Ross’s men are being driven to the river, and here the professionalism of the British once again shows its colors. With a series of quick orders the 30th Foot leads the way, flanked by the 2nd Battalion of Volunteer Infantry who maneuvered so well one officer would say “You could not tell where the 30th ended and the Volunteers began”. Hard fighting erupted as Sweeney’s men attempted to drive the regulars back with musket fire, but Maulverer directed his men skillfully. Rapid volley fire from the 30th clears the way to the field works, and soon the Americans are again driven over the line.

By 5pm the two sides had been fighting for hours, and Mount Pelion has switched hands three times. The Americans still snipe at the Canadians from the base, and a firefight raged on each flank; however closest to the water the attack is not pressed as support from Bythesea’s gunboats prevent a general assault. The only force remaining to Smith was McArthur’s uncommitted reserve, Brigadier General Jacob Lauman’s 3rd Brigade. Lauman had been fighting since early 1861, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Belmont, and his men being some of the first over the entrenchments at Fort Donelson in February. Riding to Lauman’s brigade he indicated the summit of Mount Pelion where the colors of the Canadian Volunteers fly.

“General, I want you to plant your flags on that summit and send the message that we control the field.” Smith ordered.“By God sir I’ll have the Stars and Stripes flying from the heights before sundown and we’ll show those Canucks what we did to the secesh at Fort Donelson!” Lauman replied.

Smith welded the three disparate groups together under Palmer, in effect he organized Slack’s Turchin’s and Lauman’s regiments into an ad hoc division for a final assault on the mountain. At 6pm the attack began. Preceded by another artillery bombardment that “threw such fire one can scarce believe a tree survived” before Palmer, at the head of his men, led the way as 5,000 men advanced up the slope. Fire erupted along the summit as the Canadians threw a volley at the advancing column, before the staccato of picked fire erupted all along the line. De Courcy in command, with the 30th, the Upper Canada Colored, odd companies from the 28th, and the 46th all holding the line, barely 2,000 men, and all knew they must hold the hill to the last.

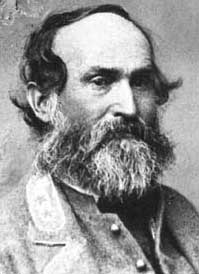

However, the 46th was relatively fresh, and Arthur, the Boy Colonel, eager for action. While the exact sequence of events varies, he is attributed to have been standing with revolver and sword speaking excitedly to his men seeing the enemy advance. His hat is shot off, at which point he crests the breastworks (perhaps in nervous excitement) and shouts “Come on men! You volunteered to die for Queen and country! Here’s your chance!” and without a backwards glance he charges down the slope. On reflex the 46th follows, soon the 30th is joining in and the Colored Corps is right behind them.

Arthur T. H. Williams before the war.

The unexpected bayonet charge smashed into Palmer’s lines with “all the ferocity of hell hounds” as one private from the 23rd Missouri would say. The momentum of the downhill charge breaks the coordinated attack, and the exhaustion of the American Volunteers shows. They break, and only the freshness of Lauman’s brigade prevents the charge from becoming a route.

A messenger from Maulverer’s men incredulously reported to Dundas “De Courcy is attacking!”

“Then in the name of God and Saint George go and help him!” Dundas snapped.

The stalemate ends as Maulverer’s men counter attack in support of De Courcy’s unexpected charge. Smith rode up and down the line with his staff attempting repeatedly to stem the rout, threatening to shoot men who don’t stop running. He manages to gather enough men to form a rearguard, just as the 1st Dragoons under Boulton enter the fray, with help from Kerr’s scouts turned warriors and they harass the American flanks. With the sun setting, Smith had no choice but to fall back to Port Colborne with his forces intact. Dundas has little choice but to let them withdraw as his own men are too exhausted to even consider pursuit, and the American cavalry form a screen which Dundas could not hope to pierce causing Boulton’s cavalry to reluctantly break off, but they would shadow the withdrawal to Port Coborg. By sundown Booker’s men have arrived, having countermarched from Frankford and take the line, bolstering Dundas’s numbers. The Battle of Mount Pelion was over.

The battle is not without cost however. Palmer is killed at the head of his ad-hoc division as the Canadians charged down slope while Turchin receives a wound for which will see him convalescent in Toronto. De Courcy and Grange were both wounded in the counter attack, and the Boy Colonel of the 46th fell mortally wounded as he led the charge. Apocryphally his last words are said to be “At least I have died for my country” Which of course should be regarded as nothing but a modern invention, but Canada gains its next war hero on the slopes of that hill.

Of the 16,000 men Smith brought to battle, 4,600 are dead, wounded or captured. The Canadians suffer heavily as well with 3,100 dead and wounded. However, the sacrifice of the Canadian Volunteers ensures that the American campaign in Canada is over for now. Hundreds of miles away the resources needed to continue it are being eaten up from fronts as diverse as Michigan, Kentucky, and Virginia…” For No Want of Courage: The Upper Canada Campaign, Col. John Stacey (ret.), Royal Military College, 1966

I'm fairly new to this timeline but I gotta say, I really like it. I'm interested in how you're going to have the war progress, and what you're going to do with Lee. I like how you've had A.S. Johnston not die and continue to lead forces in the West, that should be cool to see. I get the feeling, through subtle cues in your story, that you're gonna have the union win the war in the end. I kinda hope I'm wrong cause I feel like that is pretty unlikely to occur with Britain now at war with the north. I hope you talk about the French soon because I imagine they would definitely get involved. Anyways, pretty cool timeline and I'm definitely keeping a lookout for any updates. Good luck!

I'm fairly new to this timeline but I gotta say, I really like it. I'm interested in how you're going to have the war progress, and what you're going to do with Lee. I like how you've had A.S. Johnston not die and continue to lead forces in the West, that should be cool to see. I get the feeling, through subtle cues in your story, that you're gonna have the union win the war in the end. I kinda hope I'm wrong cause I feel like that is pretty unlikely to occur with Britain now at war with the north. I hope you talk about the French soon because I imagine they would definitely get involved. Anyways, pretty cool timeline and I'm definitely keeping a lookout for any updates. Good luck!

Thank you! I'm glad you're enjoying it! A. S. Johnston living to me is my attempt to explore a "what if" in the West, like having C. F. Smith survive as well, but he's off in Canada

Well I won't give any details for how the war ends, but I will be mentioning the French to some extent later on. They'll be larger players once 1863-64 rolls around I can give away...

If you've got any questions, queries, or suggestions throw them my way

I find it understandable that many regard A. S. Johnston as disappointing, or incompetent on the level of Polk. I respectfully disagree. Many cite the mistakes Johnston made in 1861-62, yet it must be considered that he was expected to perform a herculean task (protect the CS heartland) with a pitifully small force (for the job required of them). Few commanders could have done a good job with this, and many would have done worse than he did.Thank you! I'm glad you're enjoying it! A. S. Johnston living to me is my attempt to explore a "what if" in the West, like having C. F. Smith survive as well, but he's off in Canada

Well I won't give any details for how the war ends, but I will be mentioning the French to some extent later on. They'll be larger players once 1863-64 rolls around I can give away...

If you've got any questions, queries, or suggestions throw them my way

The only thing I will fault him is for is Fort Donelson. Due to not committing to defending the fort early enough, he wound up throwing away the equivalent of a corps.

A question: what might our assessment of certain commanders have been had they died earlier? For example:

Grant killed at Belmont: similar to Nathaniel Lyon, bold, aggressive, and willing to take risks. Like Lyon, it's possible he could have become a great commander, but it's hard to say.

Lee in West Virginia: while he might have been renowned in the Old Army, Lee showed very little indication of being able to control his subordinates, and failed miserably in the attacks at Rich Mountain.

Sherman at Shiloh: an average commander, but his dismissal of his pickets before the main Confederate attacks shows a dangerous level of negligence. It would seem an adequate epitaph would be: "Serves you right."

I find it understandable that many regard A. S. Johnston as disappointing, or incompetent on the level of Polk. I respectfully disagree. Many cite the mistakes Johnston made in 1861-62, yet it must be considered that he was expected to perform a herculean task (protect the CS heartland) with a pitifully small force (for the job required of them). Few commanders could have done a good job with this, and many would have done worse than he did.

The only thing I will fault him is for is Fort Donelson. Due to not committing to defending the fort early enough, he wound up throwing away the equivalent of a corps.

Johnston is an interesting character, his war record prior to the ACW is pretty good, and his friendship and trust with President Davis would have given him something of an advantage over Joseph Johnston, who had feuded with Davis since before the war. He mismanaged Fort Donelson (and had trouble with his subordinates who were unable to carry out his orders) but on the plus side he did as much as he could with the little he had. His diversions and distractions sent Sherman into a nervous breakdown, and made the Federals concerned that he was planning an offensive with superior numbers. The planning leading up to Shiloh was a success, but in the battle he basically fell from army commander to directing individual brigades, which cost him his life.

While there's a great many mistakes (but look at Lee and Sherman early in the war) I think his record of deception shows a lot of potential (which is how I had him so successful early on in the Kentucky invasion here) and if he can learn from his mistakes, he might prove to be an effective commander.

A question: what might our assessment of certain commanders have been had they died earlier? For example:

Grant killed at Belmont: similar to Nathaniel Lyon, bold, aggressive, and willing to take risks. Like Lyon, it's possible he could have become a great commander, but it's hard to say.

Lee in West Virginia: while he might have been renowned in the Old Army, Lee showed very little indication of being able to control his subordinates, and failed miserably in the attacks at Rich Mountain.

Sherman at Shiloh: an average commander, but his dismissal of his pickets before the main Confederate attacks shows a dangerous level of negligence. It would seem an adequate epitaph would be: "Serves you right."

Well it's true. There are many commanders who proved effective but were killed (like Lyons and C. F. Smith) who might have been amazing had they survived, or even Phillip Kearny as TheKnightIrish's excellent TL postulates. But there's many who grew into effective command (like Grant and Lee) who began rather ignobly in the war, hence Lee getting the nickname "King of Spades" or Grant getting an unfortunate reputation as a drunk. If they had died, they'd be barely a footnote in history!

For the next chapter this map should prove very helpful in visualizing the battle, though it doesn't provide all the details.

Though since it isn't all encompassing, this link will take you to another map of the area which is reasonably accurate for the purposes of charting the upcoming battle.

Though since it isn't all encompassing, this link will take you to another map of the area which is reasonably accurate for the purposes of charting the upcoming battle.

When can we expect the next update of this timeline? Also, how often do you update? I'm pretty excited for this battle, looks like Lee will be making an appearance. Taking over the army perhaps?

When can we expect the next update of this timeline? Also, how often do you update? I'm pretty excited for this battle, looks like Lee will be making an appearance. Taking over the army perhaps?

The next update should be out in a few days time, probably on the weekend or Monday. After that another chapter will shortly follow, and hopefully another. As to whether Lee is involved well you shall see, but I can promise we will see more of him.

My intent is to update (in so far as is practical) at the very least two chapters a month depending on my work schedule and how much free time I have.

EDIT: This isn't what the battle itself will look like, but merely a good map of where the battle in this chapter will be fought, Brandy Station took place on almost the exact ground I have this fight taking place on!

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 3

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 3

"Always mystify, mislead, and surprise the enemy, if possible; and when you strike and overcome him, never let up the pursuit so long as your men have strength to follow; for an army routed, if hotly pursued, becomes panic-stricken, and can then be destroyed by half their number. The other rule is, never fight against heavy odds, if by any possible maneuvering you can hurl your own force on only a part, and that the weakest part of your enemy and crush it. Such tactics will win every time, and a small army may thus destroy a large one in detail, and repeated victory will make it invincible." - Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

“McClellan had spent much of July moving his forces forward towards the Rappahannock, and establishing his headquarters and main supply dump at Warrenton. He had cautiously pursued Johnston’s retreating army southwards, as though expecting Johnston to turn on him at any moment. However, Johnston proved to be just as cautious as his opponent, which caused consternation in Richmond, and ominous mutterings about his ability to command.

McClellan, despite his slow maneuvering, was on the other hand, praised by the papers across the nation. The Battle of Centreville had been one of the few unqualified victories that year, and there was every expectation he could drive Johnston’s army further south, and resources that might have been better used elsewhere were being lavished upon him. McClellan himself spent a great deal of time overseeing the movements, gathering his forces at Warrenton, and then maneuvering along the Rappahannock to stretch out the Army of Northern Virginia under Johnston.

However, in this period he found himself feuding with a number of his subordinates. He earned the ire of Mansfield, when despite Mansfield’s requests he awarded the division of Syke’s regulars to the newly appointed XIV Corps under his favorite Major General Fitz John Porter. Mansfield, too much of an old soldier to complain, kept his opinions to himself, but there were mutterings from his subordinates. William Rosecrans, commander of V Corps, felt snubbed by McClellan’s refusal to commit him during the actions at Centreville, and McClellan himself was ambivalent towards his former subordinate in West Virginia, and some would say fearful that the other hoped to replace him at the head of the army. Rosecrans would write “I spent much of that summer unhappy as second fiddle to a military peacock…” - I Can Do It All: The Trials of George B. McClellan, Alfred White, 1992, Aurora Publishing

Rosecrans, the developing rival.

“This skirmishing and maneuvering would pay off, Johnston was forced to spread Smith’s Reserves across the Rappahannock from Barnett’s Ford(Holmes) to Fredericksburg(Ransom), using Whiting’s division as a mobile reserve to block any attempted crossing south of his headquarters at Culpeper. Stuart’s cavalry was also stretched thin as a screen for the army, with only Fitizhugh Lee’s brigade concentrated at headquarters. He remembered well his outflanking at Centreville and so was prepared to react whichever way McClellan moved.

To his north he had placed Longstreet’s men on the crossings on the banks of the Rappahannock, and Longstreet had done his best to cover the approaches to Culpeper. Anderson’s Division was placed on a hillock overlooking Beverly Ford(Battery Glassell) covering the Beverly Ford Road, with his brigades (Armistead, Wilcox, Featherston) prepared to fall back to Yew Ridge if overwhelmed. Across from them stood Pickett’s division, with his brigades (Kemper, Hunton, Pryor) covering Kelly’s Ford and Norman’s Ford. Kemper’s brigade overlooked Norman’s Ford from Payne’s Hill, while Pryor’s brigade covered Kelly’s Ford, dug in at Kelly’s Mill. Early’s division stood in reserve.

Magruder’s Corps was holding the northern flank near Muddy Run covering the way down Rixeyville Road. Johnston remained at headquarters in Culpeper, overseeing the supply of his forces…

…McClellan had, in the subsequent weeks, brought his heavy guns forward from Centreville. This had given him much needed time to establish batteries and observe the growing Confederate defences on the south bank of the river. However his “timidity” (Hooker) had allowed the Confederate positions to grow strong. McClellan was unperturbed by this however, believing that should he manage to turn Johnston’s flank again he would be compelled to withdraw further south as he had in July.

Jackson meanwhile, despite serious skirmishing in the Valley, did not seem ready to come to the aid of Johnston, leaving the flank of the army secure. The fighting at Charles Town and Summit point seemed to indicate he had no intention of moving to the south.

In order to fix Johnston’s attention he drove Smith’s Corps to distraction, making movements in the direction of Fredericksburg and Barnett’s Ford, while maneuvering in front of the Rappahannock. However, from his headquarters at Warrenton he was looking for a more direct approach. McClellan believed that Jackson was pinned in place by Sigzel in the Valley, while with Smith’s Corps was now too far spread out to maneuver in any meaningful way against the numeric superiority he could bring to bear.

To that end he dispatched I Corps to keep Smith looking the wrong way by demonstrating against Barnett’s Ford. V Corps under Rosecrans would demonstrate against the fords on the Rappahannock, supported by Heintzelman’s III Corps, while his hammer blow would come from the north.

On August 12th he dispatched the newly created XIV Corps under Porter (the divisions of Skyes, Morrell, and Cox) south from Warrenton, supported by McDowell’s IV Corps. They were to be the hammer blow which would fall on Magruders Corps, pinning him in place, so Rosecrans and Heintzelman could roll up the Confederate army and seize Culpeper forcing Johnston to retreat ever further south. The hopes were high that he would succeed, and give the Lincoln administration a much needed victory.

Unbeknownst to McClellan, Jackson had already been recalled from the Valley. Leaving Garnett’s division to vex Sigzel, who only covered McClellan’s flank as far south as Mannassas Gap, with lookout posts on Sugarloaf Mountain and Buck Mountain overlooking Chester’s Gap which would allow warning to reach McClellan of any flanking attempt, Jackson withdrew south. He took Ewell’s and D.H. Hills divisions south, transiting through Thorton’s Gap. It was here, on August 13th, that his scouts would observe a Federal column moving along Rixeyville Road. Jackson would communicate this to Johnston, who then ordered Jackson to stand in place and await further developments.

On the 14th the assaults on the Rappahannock started…” - The Rappahannock Campaign, Simon Lewis, Aurora Publishing, 2010

“McCllelan had aimed for the assaults on the Rappahannock to only be diversionary in order to pin down any other reserves Johnston might commit, and hopefully force Magruder’s Corps out of position. McClellan himself was headquartered at Bealton Station, with a steady stream of messengers reporting on the events occurring…

Though the fighting on the Rappahannock was meant to be diversionary it soon escalated into an unexpectedly decisive action…”- I Can Do It All: The Trials of George B. McClellan, Alfred White, 1992, Aurora Publishing

The men of III Corps cross the Rappahannock

“The assaults began at 1pm, with a half hour artillery barrage opening up along the line. Though McClellan had merely intended for these to be a nuisance, and perhaps soften the Confederate positions enough to prevent needless casualties in the diversionary attacks, they proved overwhelmingly effective. The heavy guns bombarded the earthworks held by Pickett’s division, and in the opening salvos overwhelmed Pryor’s brigade and it fell back in disorder towards the ridge adjacent to Mt. Dumpling. Into the sudden gap left by Pryor’s brigade the Union V Corps, streamed across the ford in good order. Leading the way was the 1st Division under Edward Ord, which crossed the stream, and made for Brandy Station, hoping to drive a wedge between Longstreet’s divisions. Pickett tried to rally his men, but their flank was well turned and they withdrew in wild disorder.

The only force which stood between them was that of Brigadier General Jubal Early. Early, a Virginian who had served against the Seminole in Florida and in Mexico, was a former Whig who had roused to the cause of Secession after the events at Fort Sumter. He had distinguished himself at Bull Run, and been promoted to brigadier general, and his brigade had been attached to Longstreet’s Corps where it had performed with distinction earning him a divisional command

As Pryor’s brigade broke Early was ordered up by Longstreet to plug the emerging gap. Outnumbered, Early’s men fell back slowly in the face of superior numbers towards Flat Run, stymieing Ord’s advance until Reno’s 3rd Division was committed. Early however, held fast, planting himself on Flat Run and declaring “The Federals will move me when my banners lay trampled in the mud.” Despite repeated attacks, both Reno and Ord failed to dislodge him, and soon Pickett’s reorganized division was stepping into the line…

Jubal Early

Heintzelman’s III Corps did not begin their attack so well. Anderson’s men had established excellent earthworks, and despite the pounding gave good account of themselves. Armistead’s brigade, dug in at Battery Glassel, stood off three assaults by Daniel Butterfield’s 1st Division in Heintzelman’s III Corps, until his 2nd Division under Hooker was thrown forward. Hooker’s 1st Division under Naglee would carry Beverly’s Ford under the cover of artillery. Anderson’s men soon fell back to prepared positions on Yew Ridge, holding off a determined assault by Hooker’s 2nd Brigade under the notorious Daniel Sickles, if only barely.

The position though, was tenuous. The line was disorganized in the center, and Early’s flank was snarled between Flat Run, and the Old Carolina Road, with only a thin screen provided by his outermost brigade. Hooker, realizing this, saw the chance to turn Anderson’s flank by cracking the line at St. James Church. Butterfield’s division was rotated out, and Hooker’s men moved forward, skirmishing with the Confederates on Yew Ridge. Winfield Featherston’s Mississippians were the only force tentatively holding the flank at the church, and Hooker determined they were ripe for the picking.

Samuel Starr’s “New Jersey Brigade” was fed into the fray at 5pm, the New Jerseyans and Mississippians clashed for over an hour with the church itself being severely damaged before Anderson pulled his line back towards Fleetwood Hill, but the success of the attack was short lived as the Pickett’s Division was stepping into the line, and the Confederates held firm despite the best efforts of Heintzelman, and Rosecrans.

As the sun set the Confederates held a rough line stretching from Fleetwood Hill to Paoli’s Mill. Longstreet seemed firmly dug in, and the Union had suffered numerous casualties (especially amongst the men of III Corps) in forcing the fords. However, it seemed McClellan’s plan would succeed, and come the morning the hammer of Porter and McDowell would crash home on the unsuspecting northern flank of the Confederate army…” - The Rappahannock Campaign, Simon Lewis, Aurora Publishing, 2010

Things are going too well for the Union, I think something will go awry for them in the coming day...

RodentRevolution

Banned

Things are going too well for the Union, I think something will go awry for them in the coming day...

Well there are more than a few issues awaiting in the wings for the Union. The biggest problem for them is while they are doing about as well as can be expected and it most certainly not going their way the matter is still in contention and they know the fuse is burning (in fact the supply of fuse cord may well be one of those upcoming issues).

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 3.2

Chapter 28 War Means Killing Pt. 3.2

“The fighting had largely petered out by nightfall as the Federal forces consolidated their hold on the west bank of the Rappahannock, Rosecrans and Heintzelman were bringing up their artillery in the expectation of a dawn assault in conjunction with Porter’s Corps which would strike the out of position Corps of Magruder, and in doing so drive the Confederates back to Culpeper Court House, and further south, making Jackson’s position in the Valley untenable.

The proceeding day’s attacks had gone better than McClellan had expected, and so he anticipated little trouble with the follow up assault on the 15th. Messengers come in the night had informed him that Porter and McDowell were in position, and despite some skirmishing with Confederate cavalry, it seemed that Johnston was focused on his flank on the Rappahannock. McClellan, understanding that now a swift assault would be necessary for success, ordered that Porter begin his attack at sunrise, and retired for the night.

The news was passed back along the line to McDowell’s command, which forwarded it up the road to Porter’s headquarters at Springfield. Porter, had the men sleep on their arms so all would be in readiness for the assault in the morning.

Johnston, apprehensive of an assault on his front, was now convinced that he would face a dawn attack. Filled with a restless energy, he remained awake all night awaiting messages along the line. Was Jackson in position? He was. Was Magruder prepared? He was. Johnston’s nervous energy would see him described as “pacing like a caged lion and stamping like a ready horse” as he waited for the events at dawn. His orders to Jackson were clear, he was to await the sound of guns, and attack.

Magruder, who had been ordered not to alert the Federals with his preparations, had his three divisions (McLaw’s, Jones, and Griffith’s) dug in along the Hazel River, stretching to Ruffin’s Run, where it had tenuous contact with Longstreet’s division at Fleet Hill. His main concern was protecting Hill’s Mill, Burnt Bridge Ford, and Stark’s Ford. Jones division, badly battered at Centreville, was held in reserve, while McLaw’s held the fords in conjunction with Griffith’s men. Hills Old Mill had been fortified by Kershaw’s brigade and acted as the hinge which held the line along the Hazel River, while entrenchments had been dug to cover Burnt Bridge Ford…

Porter’s men had used Big Indian Run to mask their advance, and hauled their artillery up during the night. The 3rd Division, under Jacob D. Cox, was to open the attack in conjunction with George Morell’s 1st Division, while Syke’s regulars were to exploit the breakthrough of the Confederate lines. McDowell was the reserve, who would cross to where there was trouble.

The plan was for Cox’s men to assault Hill’s Mill and unhinge the line, allowing Morell’s men to bring their guns to bear on Burnt Bridge Ford, and move down to Rixeyville. Stark Ford was to be ignored, and hopefully drive the forces their into the arms of the waiting Hooker and Rosecrans. With his superiority in artillery McClellan rationalized that he could drive the Confederates from their entrenchments, and move on Culpeper. So long as surprise was maintained, he anticipated little difficulty in the assault.

At 6:35am the guns sounded.

In order to maintain surprise the guns had been moved in the dead of night, and unfortunately Cox’s division had the furthest to go, and did not actually begin their attack until 6:50, but with the guns in place they bombarded the fortified position at the mill. Morrell’s men, who had both the shorter movement and an advantage in ground, began on time. With their advantage, they swept Semme’s brigade away, and rushed the ford in under half an hour. Semme’s men withdrew in the direction of Rixeyville, leaving Kershaw’s brigade at Hill’s Mill dangerously exposed. Kershaw, completely unaware of Semme’s withdrawal, clung doggedly to his position as Cox’s men attacked repeatedly. At 7:40, Skye’s regulars were ordered forward to support Morell…

Jackson had slept soundly that night. He knew where the Union was, and had a rough intuition of when they would begin their attacks. In the morning he had mounted up, and brought Ewell’s Division forward down Stone Run Road.

Ewell’s men (Trimble, Taylor, and Elzey’s brigades) caught Cox’s Division as it began its second major assault on Hill’s Mill. Cox’s men, tired from over an hours fighting, were caught off guard, and Cox ordered their withdrawal towards Big Indian Run, sending urgent messages of a force on his flank. Ewell’s men pursued Cox closely, moving to position themselves between the fords and Porter’s men. However, Skye’s regulars had not completed crossing the river, and upon hearing the whooping rebel yell, turned to position themselves in the face of the oncoming onslaught. The regulars, with a steely determination, faced off with Ewell’s men at Doyle’s Farm, and across Stone Run. In a series of hard fought stands in woodlots and orchards they sought to prevent Ewell from cutting them off. In this the regulars did admirably, at one point closing to hand to hand combat with the men of Trimble’s brigade as they attempted to force their way through the orchard.

Hill’s division was attempting to move around their flank and position themselves between Little Indian Run, and any hope of McDowell’s reinforcement…” The Rappahannock Campaign, Simon Lewis, Aurora Publishing, 2010

Jackson feeds his men into the battle.

“McDowell’s headquarters at Jeffersonton were a scene of confusion. The wild reports from the front line told him that Magruder’s Corps had flanked Cox, and was even now positioning itself at Big Indian Run, others said Jackson’s Corps had flown in from the Valley and was preparing to encircle their position and cut off retreat. McDowell was at first unsure of what to believe, and a crucial hour passed before he was reasonably sure of Porter’s predicament to send a message to McClellan. In the meantime he had ordered McCall’s Pennsylvanians forward to Big Indian Run…

…McClellan did not receive the news of Jackson’s attack until 10am. So far along the Rappahannock there had been little more than heavy skirmishing as the McClellan waited for the response from Porter’s attack. However, despite three hours of fighting he had seen no change in the Confederate dispositions along their line. This concerned him, as the news he had received from Porter had confirmed a successful crossing of the Hazel River, while his position on the Rappahannock was stronger than it had been yesterday. Surely there would be some response from Porter?

The hour delay in the dispatch of McDowell’s message meant that events were already coming to a head at Big Indian Run when McClellan received the news of Jackson’s attack. McDowell made clear he believed it to be Jackson, and that he was moving in support of porter. The news sent McClellan into a sudden silence. “He looked for a moment like how Napoleon must have looked upon news of the Prussian arrival at Waterloo” chief of staff Randall Marcy would write. Seeing in his mind the situation that his two Corps must be in, either cut off by the Hazel River and flanked by a fresh enemy force or withdrawing, he ordered a diversionary attack on the Confederate line, and sent orders for McDowell to protect Porter and begin withdrawing to Warrenton.” - I Can Do It All: The Trials of George B. McClellan, Alfred White, 1992, Aurora Publishing

“McDowell seems to have misunderstood his orders from McClellan, believing he needed to withdraw immediately to Warrenton he ordered Franklin’s division to begin moving their supplies at 12:09pm. Meanwhile King’s Division would be held as the reserve to support McDowell. This misunderstanding meant he would not have the strength to counterattack and drive Jackson off should the need arise.

Porter meanwhile was fighting for his life and attempting to extract himself from the trap Johnston had created. Magruder had counterattacked, sending Jone’s Division forward to Rixeyville. Morell’s men were caught fast between Ewell’s approaching division, and Hill attempting to cut off their retreat. Cox division had scrambled as far as Big Indian Ford, just in time to join McCall’s men as Hill’s division attacked. The presence of McCall’s fresh troops prevented disaster as Cox men fell into line. The fighting would stretch all along the riverfront, until Hill attempted to turn the flank by sending Rodes brigade around Parr’s farm.

Morell’s men were now moving across the Hazel River, John Martidale’s brigade forming a desperate rearguard, under the cover from the divisional artillery on the high ground, while Syke’s regulars held the flank against Ewell’s men. Morell now received the incorrect information that the roads back north were blocked, and so requested permission to order a withdrawal towards White Sulfer Springs.

Porter, listening to the sounds of battle to the north, and assuming it was the unfortunate destruction of Cox’s division, reluctantly gave his assent. He assumed McDowell had not advanced to save him and was heard to curse “God damn McDowell, he’s never where he’s supposed to be!” as the Corps withdrew…

The rear guard holds the line.

Porter’s withdrawal, opened the way for Magruder and Jackson to both attempt to cut off McDowell. Jone’s and McLaw’s pursued Porter, hoping to drive him into Jeffersonton and cut him off as Jackson had done to Banks at Winchester. However, Rodes attempt to cut the flank had been halted at Parr’s farm by Seymour’s 3rd Brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves. Slowly but surely they were able to withdraw towards Jeffersonton, where King’s division waited to act as rearguard…

The rearguard action at Jeffersonton saved Porter and McDowell, allowing them to withdraw back in safety across the Rappahannock. McClellan’s assaults to pin Longstreet in place, though costly, had ensured he too could withdraw across the river towards Warrenton…” The Rappahannock Campaign, Simon Lewis, Aurora Publishing, 2010

“The end result of the Rappahannock campaign saw McClellan return to the fortifications at Centreville and dig in across the Bull Run. McClellan informed Washington he was now outnumbered on his front, saying that 150,000 Confederates would converge on Centreville, at any moment. “I have lost this campaign because my force is too small. Had I but 10,000 more men I could be secure in the knowledge that we could defend the capital. This campaign has seen too many dead, wounded, and broken men for me to do anything but hold my position here.” In effect McClellan was requesting more men to mount a defensive campaign. Not only that, but a significant portion of his artillery had been lost in the retreat, especially by Porter’s Corps who had suffered the brunt of the fighting at Hazel River. He now demanded more resources to simply keep his army in place.

Matters had been made worse when Johnston had unleashed Stuart’s cavalry on his great ride on the 20th of August. In eight days Stuart had ridden rings around his opposite numbers, wrecking the supply depots that Manfield’s I Corps had worked to establish, and discomforting McClellan’s retreat towards Centreville by burning wagons and harassing the withdrawing columns. They had returned to Confederate lines to great acclaim in the Richmond papers, and Stuart’s reputation would climb ever higher.

This came at a time when commanders on all fronts were calling for more resources. McClellan’s campaign to push the Confederate army south had failed, but he was no further north than he had been last year which soothed some fears in Washington. That they had no more resources to spare him at the moment, would be a source of considerable anxiety…” To Arms!: The Great American War, Sheldon Foote, University of Boston 1999.

Things are going too well for the Union, I think something will go awry for them in the coming day...

Just because things are going well doesn't mean they'll be worse later! However, when Stonewall Jackson is involved things usually get a little dicey...