You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wrapped in Flames: The Great American War and Beyond

- Thread starter EnglishCanuck

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 158 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation Chapter 133: Alarms IgnoredEnglishCanuck, don't you mean 1861 in the first chapter?

Which paragraph? I've got 148 pages of story with over 70,000 words of text

Whichever part though I can edit it at least!

Which paragraph? I've got 148 pages of story with over 70,000 words of text

Whichever part though I can edit it at least!

It's in the first chapter when you're discussing the Trent incident...

It's in the first chapter when you're discussing the Trent incident...

Ah caught what you mean.

I mean 1861 indeed! Thanks for catching that and edited!

She was indeed. She made the recommendations regarding winter clothing and hot food, which was what necessary to keep men warm as they were in barrack.

she was also an inspiration for this American organization modeled very closely on the British one

which was started in May 1861 so would be already in existence before the POD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Sanitary_Commission

she was also an inspiration for this American organization modeled very closely on the British one

which was started in May 1861 so would be already in existence before the POD

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Sanitary_Commission

They did good work. Using her methods they probably saved tens of thousands of lives which would have otherwise been lost.

Still a shame no one had figured out disinfection yet. If you don't want to eat for a few days looking at the injuries left behind by the rifles of the era is a good way to lose your appetite...

They did good work. Using her methods they probably saved tens of thousands of lives which would have otherwise been lost.

Still a shame no one had figured out disinfection yet. If you don't want to eat for a few days looking at the injuries left behind by the rifles of the era is a good way to lose your appetite...

or germ theory for that matter

at least,when its available, there is chloroform which is a marked improvement for those undergoing surgery

or germ theory for that matter

at least,when its available, there is chloroform which is a marked improvement for those undergoing surgery

Quite.

Chloroform saved just as many lives I would think since it helped prevent many from going into shock. That show Mercy Street made it look rather advanced for its day, but I can say I have not extensively studied the history of medicine in this era so my understanding might be a bit flawed.

Saphroneth

Banned

Quick Wiki suggests it was discovered to work for that purpose in 1847 in Scotland. It wasn't taken up in the US until the beginning of the 20th century, though - they preferred Ether (first British perscriptions 1840 in conjunction with Opium, first US usages 1842 or so).Chloroform saved just as many lives I would think since it helped prevent many from going into shock. That show Mercy Street made it look rather advanced for its day, but I can say I have not extensively studied the history of medicine in this era so my understanding might be a bit flawed.

RodentRevolution

Banned

It seems that at least some physicians were dead against chloroform in the US

http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Articles/Ether_sulphuric_inhalation_1861.htm

http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Articles/Ether_sulphuric_inhalation_1861.htm

The link should detail a presentation made to the Boston Society for Medical Improvement, October 14th 1861 (let me know if there is an issue)

"This may happen and unfortunately has happened but such an event cannot be laid to the anaesthetic since in such a case it is the method of administration and in no sense the ether which causes the fatal result. It is the purpose of this report to solve the doubt just implied with regard to the absolute safety of sulphuric ether and to investigate the dangers of its use as compared with chloroform."

For those lazy of reading I shall skip ahead

The general conclusions which have been arrived at by your Committee may be summed up as follows:

1st The ultimate effects of all anaesthetics show that they are depressing agents. This is indicated both by their symptoms and by the results of experiments. No anœsthetic should therefore be used carelessly nor can it be administered without risk by an incompetent person.

2d It is now widely conceded both in this country and in Europe that sulphuric ether is safer than any other anaesthetic and this conviction is gradually gaining ground.

3d Proper precautions being taken sulphuric ether will produce entire insensibility in all cases and no anaesthetic requires so few precautions in its use.

4th There is no recorded case of death known to the Committee attributed to sulphuric ether which cannot be explained on some other ground equally plausible or in which if it were possible to repeat the experiment insensibility could not have been produced and death avoided. This cannot bo said of chloroform.

5th In view of all these facts the use of ether in armies to the extent which its bulk will permit ought to be obligatory at least in a moral point of view.

6th The advantages of chloroform are exclusively those of convenience. Its dangers are not averted by its admixture with sulphuric ether in any proportions. The combination of these two agents cannot be too strongly denounced as a treacherous and dangerous compound Chloric ether being a solution of chloroform in alcohol merits the same condemnation.

Btw the rest of the site looks worth a gander, it can be navigated at the bottom of the linked page.

http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Articles/Ether_sulphuric_inhalation_1861.htm

http://www.medicalantiques.com/civilwar/Articles/Ether_sulphuric_inhalation_1861.htm

The link should detail a presentation made to the Boston Society for Medical Improvement, October 14th 1861 (let me know if there is an issue)

"This may happen and unfortunately has happened but such an event cannot be laid to the anaesthetic since in such a case it is the method of administration and in no sense the ether which causes the fatal result. It is the purpose of this report to solve the doubt just implied with regard to the absolute safety of sulphuric ether and to investigate the dangers of its use as compared with chloroform."

For those lazy of reading I shall skip ahead

The general conclusions which have been arrived at by your Committee may be summed up as follows:

1st The ultimate effects of all anaesthetics show that they are depressing agents. This is indicated both by their symptoms and by the results of experiments. No anœsthetic should therefore be used carelessly nor can it be administered without risk by an incompetent person.

2d It is now widely conceded both in this country and in Europe that sulphuric ether is safer than any other anaesthetic and this conviction is gradually gaining ground.

3d Proper precautions being taken sulphuric ether will produce entire insensibility in all cases and no anaesthetic requires so few precautions in its use.

4th There is no recorded case of death known to the Committee attributed to sulphuric ether which cannot be explained on some other ground equally plausible or in which if it were possible to repeat the experiment insensibility could not have been produced and death avoided. This cannot bo said of chloroform.

5th In view of all these facts the use of ether in armies to the extent which its bulk will permit ought to be obligatory at least in a moral point of view.

6th The advantages of chloroform are exclusively those of convenience. Its dangers are not averted by its admixture with sulphuric ether in any proportions. The combination of these two agents cannot be too strongly denounced as a treacherous and dangerous compound Chloric ether being a solution of chloroform in alcohol merits the same condemnation.

Btw the rest of the site looks worth a gander, it can be navigated at the bottom of the linked page.

Chapter 23: To Change Her Masters

Chapter 23: To Change Her Masters

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry-arch

Of the North-Church-tower, as a signal-light,--

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country-folk to be up and to arm.”

Then he said “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war:

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon, like a prison-bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers

Marching down to their boats on the shore.” – The Ride of Paul Revere, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1861

“The chief strategy for the spring campaign of 1862 agreed upon by Whitehall and the Horse Guards centered on both the desire to secure the overland communications with the Province of Canada and that to draw off as many American troops as possible from an inevitable invasion of the Province. To that end, plans for a campaign against the Atlantic terminus of the Grand Trunk Railway at Portland were drawn up as early as December. De Grey’s early draft involved as few as 8,000 men, while another plan suggested by MacDougall, called for 50,000 men to ensure its speedy success.

In the end, a compromise was agreed upon. A force of two divisions would be assembled in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and shipped to Maine in order to seize Portland, and if necessary, operate further in the state. This being done swiftly, and the overland route to Canada reasonably secure, the British expected that the American government would quickly come to terms and sit down at the negotiating table, regardless of the events in Canada.

The Admiralty was far from enthusiastic about the planned campaign against Portland, Milne because it detracted ships from his preferred strategy of blockade, and the Admiralty because of the great frustration they had felt over the Eastern campaign in the Russian War. Captain Washington (serving as an ad hoc staff officer with the Admiralty), in his preliminary plan drawn up in December wrote: “If it were desirable to take possession of the place (which seems doubtful), it should be done before the inner fort could be finished or other works thrown up. But it would require a strong force, say, several line of battle ships or two armor plated ships and some heavy frigates.”

However, the Army would get its way, as in the belief of MacDougall: “The interests of Maine & Canada are identical. A strong party is believed to exist in Maine in favor of annexation to Canada; and no sympathy is there felt for the war which now desolates the U. States. It is more than probable that a conciliatory policy adopted towards Maine would, if it failed to secure its absolute co-operation, indispose it to use any vigorous efforts against us. The patriotism of the Americans dwells peculiarly in their pockets; & the pockets of the good citizens of Maine would benefit largely by the expenditure and trade we should create in making Portland our base & their territory our line of communication with Canada,”

This of course brought to mind long ago reflections on New England’s dissatisfaction with the previous war half a century earlier. Such overly optimistic projections drove the plan forward. Milne wrote in a final objection, hoping to strengthen his argument with that position, that he “would rather feel my way at Portland, rather than at once adopting active operations against that Town and State. An active blockade would offer evidence that we might wait and see whether the State was inclined to change its masters.”

There were some reservations, Burgoyne writing: “…it will require great caution to attempt to make an impression ourselves from the sea on the Federal territory itself; for though, with a good force, we might gain momentary possession, there would be nearly the certainty of being overwhelmed at last by the masses that would be brought against us.” But regardless of such dissenting opinions, the plan pressed forward from its planning stages in December and January, to the implementation stage in February as troops were dispatched.

Much to the disappointment of both Williams and Dundas in Canada, troops and supplies were concentrated at Halifax and St. Johns for the expedition against Portland, and such material received top priority on shipping come the spring.

By May the force collected throughout the Maritimes, The Army of the Maritimes, was under the command of Lieutenant General Sir John Lysaught Pennefather[1]. At 63 Pennefather had been serving in the Army for over 40 years. He had entered the forces in 1818 as a cornet with the 7th Dragoon Guards, and earned his way up the ranks to Lt. General. None of these ranks were purchased by commission, each had been earned by merit. He had commanded a brigade in India at Meanee, and most famously in the Crimea where through chance he ended up in command of the 2nd Division at Inkerman as the Russians launched their ill-fated attack on the siege lines. He commanded the garrison at Malta from 1855-1860 when he was placed in charge of the camp at Aldershot, from which he drew much of the strength of the Army of the Maritimes. With his varied command experience, and unquestionable skill in the field, he was noted as a natural to command this force.

Lt. General Sir John Pennefather

The army was composed of two divisions of infantry come the spring, one division of cavalry, and a full complement of field and siege artillery, numbering 26,000 men and 66 guns. The men had been assembled largely from the garrison in Ireland and the troops at Aldershot, all soldiers who had been drilling strenuously in the previous year, with the numbers bolstered by the original garrison troops from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. It was organized accordingly:

Army of the Maritimes: Lt. Gen. John Pennefather

Staff:

Chief of the Staff: Col. Charles Tyrwhitt (From Headquarters)

ADC:

Capt. Ellison (47th Foot)

Maj. Paget Bayly (Unattached)

Assistant Adjutant General: Lt. Col. Sir Henry M. Havelock

Assistant Quarter Master General: Lt. Col. H. H. Clifford

Commanding Royal Artillery: BG Henry S. Rowan

Commanding Royal Engineers: Col. J. A. Simmons

1st Division (MG Brooke Taylor)

1st Brigade (BG W. G. Brown) 1/2nd, 29th and 61st

2nd Brigade (BG John Alexander Ewart) 1/8th, 53rd and 78th

3rd Brigade (Col. Charles North) 2/20th, 1/60th Rifles and 84th

Divisional Artillery (Lt. Col. Thomas Knox)

2nd Division (MG Charles Trollope)

1st Brigade (BG John A. Cole) 1/15th, 2/16th and 2/17th

2nd Brigade (Col. Charles Hood) 2/19th, 58th and 2/60th Rifles,

3rd Brigade (BG Alexander Gordon) 1/11th, 2/21st and 45th

Divisional Artillery (Lt. Col. Henry A. Turner)

Cavalry Division: (MG George Paget)

1st Brigade (BG. John Foster) 9th Lancers, 12th Lancers, 16th Lancers, Royal Horse Artillery

2nd Brigade (BG G.W. Key) 5th Dragoons, 5th Hussars, 11th Hussars, Royal Horse Artillery

All told it was a force as large as that which had landed in the Crimean in 1854 some eight years previous. It remained to be seen whether it would be capable of accomplish its task of storming Portland…”– Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV

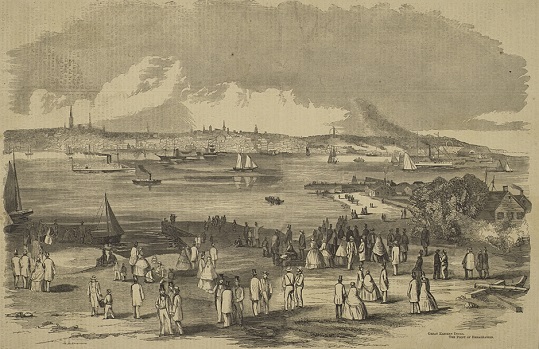

Portland Maine 1860

“The city of Portland was seen as an obvious target by American strategists. Maine had of course been a warzone in the 1775-83 and the 1812-1815 conflicts against Britain. Whether it was the disaster on the Penobscot, or the sacking of Bangor and Hampden, the fact that Maine itself had been a battleground was long remembered in that state. It was thought though, that when the British withdrew in 1815, this would be the end of two centuries of conflict for control over the waters in the Gulf of Maine.

That idea proved to be in error.

In 1862 Maine was well involved in the War for the Union, having mustered some 16,000 men for the war effort by winter 1862, and the call for further volunteers leading to the muster of the state militia to garrison the vital points along the coasts.

Portland, the city which the British strategy aimed at thanks to its connection to Canada via the Grand Trunk Railway, was already defended by a brigade of Maine militiamen under Maj. Gen. William W. Virgin of the Maine State Militia who garrisoned Forts Preble and Scammel, and the earthworks on Hog Island which would compromise the later Fort Gorges. Here he was supported by a division from Benjamin Butler’s Army of New England under Brig. Gen. Thomas R. Williams, which brought the strength of the garrison to 15,000 men come May 1862.

However, the American strategy, could not assume Portland as the only target. There were still the cities of Boston and Portsmouth, and the naval yard there to consider. And so the Army of New England, 40,000 strong, was spread out across the whole of the department in order to cover the defenses of the coast.

William’s division was stationed in Portland, while Erasmus D. Keye’s division was headquartered at Boston, William F. Smith’s division was stationed at Portsmouth. The 4th Division under Silas Casey was in reserve, waiting to spring into action to support against any landing of the British troops. They were supported by mixed divisions of state militia and volunteers who padded out the fortifications and field works to free up each division to take the field against the expected British landings.

The defences of Portland itself though were weak when war had broken out. As the new year had dawned Fort Preble had all of 12 24 pounders and a single 8 inch gun in the battery, while Forts Scammel and Gorges were completely unarmed[2]. Taking advantage of the delay in the British offensive the cities fortifications had taken shape under Major Thomas Casey of the engineers. He had, with the support of the Board of National Defense and Chief Engineer Joseph Totten, rallied to have each fortification armed as far as possible by spring when it could be expected that the British would be able to mount a landing. With his tireless efforts Fort Preble mounted 34 guns, Fort Scammel mounted 50 pieces and Fort Gorges had two batteries of 8inch guns for a total of 12 guns facing out to sea and covering Diamond Island Roads and the passage between Catfish Point and Maiden Cove. The landward defences, occupied by William’s men, consisted of redoubts placed along a series of entrenchment stretching along the Stroudwater and Fore rivers which protected the landward side of the harbor to the south, and entrenchments along the Presumpscot River to the north, centered on the Village of Westbrook where the two rivers drew close to one another.

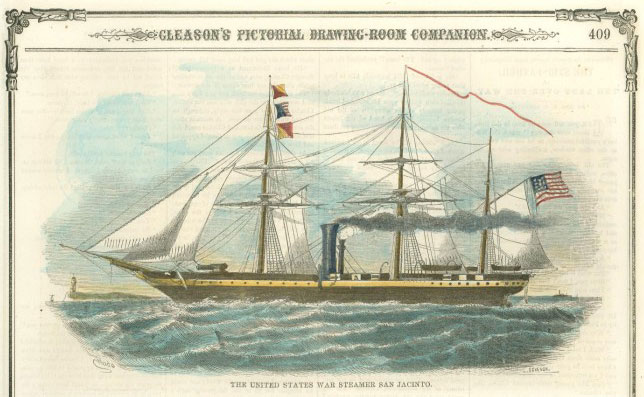

There was little naval support to be had for the city. Flag Officer Charles Wilkes[3], the man many would blame for the widening of the war, had been assigned to the new “North Atlantic Squadron” was assigned to Boston to assemble this new force. His duty was to keep Boston and Portsmouth secure, and to contest the waters from Massachusetts Bay to the Gulf of Maine. As the new year dawned he found he had little enough strength to protect his own base of operations. The steam sloops San Jacinto(12) and Wachusett(10) with six of the new five gun screw gunboats, Sagamore, Aroostook, Chocura, Huron, Marblehead, and Penobscot were based out of Boston. In addition, after the success of the Monitor, two new “90 Day ironclads” were under construction at Charlestown and Kittery, the Nantucket and Nahant which would be tasked with defending the harbors. These all would soon be joined by the steam sloops Ossipee and Housatonic. Finally, the old unfinished screw frigate, USS Franklin, was being converted as an experimental ironclad alongside her sister USS Roanoke.[4]

This was all the naval force which could be mustered in the early months of 1862 though, many of the ironclads would not be in service for months, and in Portland itself only the old sailing frigate Macedonian stood anchored in Portland harbour as a blockship. Effectively, the sea lanes had been conceded to the British early on in the war, a fact which they would take full advantage of…”– To Arms!: The Great American War, Sheldon Foote, University of Boston 1999.

The ship that started it all, the USS San Jacinto

“The invasion fleet, gathered with speed and efficiency at the end of April, departed for Portland on May 2nd 1862. It was an immense fleet carrying out the expedition. It contained 5 ships of the line, 3 frigates, 4 sloops and corvettes, 5 gunboats and 2 mortar frigates. Alongside this came the “Inshore Squadron” consisting of the one ironclad frigate, one ironclad sloop, and 4 floating batteries for inshore work to disable the fortifications in Portland Harbor. Aside from the assemblage of warships there were 87 vessels chartered to transport Pennefather’s soldiers, supplies, guns, and draft animals to the front. These ranged from the enormous Admiralty steam transport Himalaya, to the small Nova Scotian built barque McDuff.

Overall command was given to Vice Admiral Sir William Hope-Johnstone, second son of Admiral Sir William Johnstone. At 63, Johnstone had been in service with the Royal Navy since 1811. Serving in various capacities across the world in South America, the Mediterranean and the East Indies his duties had seen him primarily in command of sail vessels. In his years of service though, he had seen numerous assaults on fortified ports, most notably an expedition up the Brune River in 1846 against the Sultan of Borneo. He had been reassigned from the Nore command aboard the recently worked up Goliath(78) as his flag. His former flag, the steam frigate Formidable, had been assigned to convoy duties in the North Atlantic.

Serving under him was Rear Admiral Sydney C. Dacres in Edgar(89). Son of Vice-admiral Sir Richard Dacres, and brother of General Sir Richard James Dacres, he entered the navy in 1817. He had earned significant experience with steam vessels and operations against ports while in the Black Sea and operating against Sevastopol. In 1859 he had been transferred to the Mediterranean, where he would become second in command there. Initially slated to be Milne’s second in command he had been moved to the Portland expedition, merely one more move the Admiralty was unhappy with in the allocation of resources for the initial war effort.

Finally, commanding the inshore forces was acting Commodore Arthur Cochrane. At 37 he was the youngest of the bevy of officers assigned to the expedition, and was commanding the most modern ironclad yet in commission in the Royal Navy, the Warrior. He had joined the navy in 1839, and so had significantly less experience under his belt than his superiors, but most of it gained from hard fighting. He had been at Acre during the Oriental Crisis in 1840, where he was wounded, and then in the Baltic during the Russian War where he had blockaded the Russian ports, and finally in the Second Opium War where he had helped destroy the Chinese fleet in 1857, and participated in the bombardment of Canton.

The Naval Force was organized thusly:

First Division (Johnstone): Goliath(74)[F], Trafalgar(86), Meeanee(80), Queen(86), Emerald(51), Tribune(31),

Second Division (Darcres): Edgar(89)[F], Arethusa(51), Raccoon(21), Malacca(17), Rapid(11), Swallow(9), Speedwell(5), Pandora(5), Dart(5), Surprise(4), Wanderer(4),

Inshore Squadron(Cochrane): Warrior(40)[F], Defence(22), Terror(16), Aetna(14), Glatton(16), Erebus(14), Horatio(12), Eurotas(12)

In addition to these vessels, the blockading squadron which had been in place since early March consisted of the vessels: Algiers(86), Rattlesnake(21), Rattler(17), Rifleman(5), Sparrow(5).

The First Division lead the charge, while the Inshore Squadron came up behind. The Second Division was engaged in escorting the vessels which carried the troops and supplies. The fleet first stopped at Eastport, where after a short bombardment they occupied Fort Sullivan with a mixed battalion of Royal Marines and sailors. From there they proceeded to Castine where after another bombardment, it too would be occupied by the Royal Marines, and they would sweep up considerable traffic which was attempting to run to Augusta, including the steamer Chesapeake. The gunboats Surprise and Wanderer were deposited to patrol the mouth of the Penobscot River and support the Marine garrison detached there.

After these short diversions, the fleet moved with haste towards Cape Elizabeth. Dacres squadron continued onwards towards the landing site, while the First Division and the Inshore Squadron continued towards Casco Bay, taking up positions at Maiden Cove where it was expected they would meet the infantry on the advance inland. The plan was that Pennefather’s forces would land on the soft sands of Cape Elizabeth at Seal Cove and from there they would march inland and take Fort Preble from the landward side in conjunction with the navy and unhinge the entire defensive position at Portland, compelling the cities surrender. On the morning of May 11th Pennefather’s 1st Division worked their way ashore in cutters, launches, and sweeps from the fleet of transports, under the safety of Darcres guns.

The landings proceeded smoothly, and other than some initial skirmishing with local Home Guards, they were unopposed, and sat within 7 miles of Fort Preble, the target of the overland assault. However, the invasion message flashed out and by the evening the Army of New England was in motion.

The first to move was Casey’s division, working its way north, but even with the best marching speed, they were still six days from Portland. Smith’s division was closer, but they were five days march at the best time from Portsmouth. Units were embarked by train to speed them north to the cities defence, but for crucial days the city would be on its own.

Despite this, Williams Division, 10,000 strong, was determined to do its best to stymy the British advance. Thomas Williams, aged 47, had been a career soldier since 1832 when he served as a bugler in the Black Hawk War, then earning a commission by graduating from West Point in 1837. He then fought against the Seminole in Florida, and served in Mexico, brevetted for “meritorious service” in the fighting. On the outbreak of the Civil War he had been a major, but was soon promoted to Brigadier General in February 1862, for a projected campaign against New Orleans. As tensions with the British grew however, he had been reassigned to Portland with his division in order to stiffen the ranks of local militia. Four months of drill and preparation had prepared him for this however, and when the British did land, he reacted with admirable swiftness.

Thomas Williams

Leaving the defence of the forts and outlying defences to Virgin’s militia, he brought his First Brigade to stall the British advance at Alewife Brook. Emptying from Great Pond to the west, Alewife Brook lay directly across the British line of advance, and so Williams set out to hold it. He dug in his brigade across the road, supported by his divisional artillery, while his second brigade moved west to cover the crossings up Bowery Road…

…By the afternoon of the 12th, Pennefather’s 1st Division was ready to advance inland. Supported by the 1st Brigade of cavalry from Paget’s division, they moved up Kettle Cove Road, advancing until the cavalry came into contact with Williams men. In the resulting firefight the cavalry was pushed back, and Brooke Taylor’s Division advanced to deal with the entrenched Americans.

A sharp firefight erupted between the two sides as Knox’s artillery arrived, but when it did, the range and strength of the British guns, like it would on many other fields, decided the battle. William’s men were practically blasted from their trenches. William’s himself led a futile defence of their positions until felled by a bullet from a British marksman. Though mortally wounded, he lived long enough to order his men’s retreat to the trenches below Portland. He would be captured by the men of Brown’s brigade, but would die of his wounds two days later.

Taylor, though unperturbed by the delay caused by the battle, was worried that his timetable would be thrown off by the stalling thanks to William’s defence. He arrived at Maiden Cove and signaled the ships of Cochrane’s squadron, but as he feared, night was closing fast and his men would need to assault the forts in conjunction with the ships. So he marched his division to the edge of the American entrenchments, just beyond the range of the American guns, and began digging his own men in. Cochrane’s ships made a few ranging shots at the American fortifications in preparation for the assault come the dawn, and the British slept on their arms. The Union men hunkered down in their trenches, dreading the storm to come in the morning.

Then everything went wrong.

On the dawn of May 13th Cochrane’s ships lead the way. Cochrane commanding from the deck of Warrior, with the mortar frigates anchoring off Cushing’s Island and began bombarding the American forts and the ironclads leading the way up through Danforth Cove to Forts Scammel and Preble. As they came ahead of Scammel Point, they ran in to the first layer of torpedoes laid by the American defenders.

Torpedoes were not a new innovation. Indeed the use of underwater explosives dated all the way back to the Revolutionary War where simple kegs filled with gunpowder were used to attempt to deter British ships. The Russians had used them in conjunction with landward defences in the Black Sea and the Baltic to stymy the efforts of the Royal Navy. Those all had been inefficient and not particularly threatening to warships. Even though the British were aware of their existence, it was assumed that the ironclads could simply sail over them. In this they were both right and wrong.

At 10:23am, Warrior’s unarmoured bow struck a torpedo with a violent explosion tearing through her front compartments. Though she was compartmentalized to protect against such damage, the ship was shoved violently off course, nearly sending her into a collision with Defence. The smaller ironclads all veered to avoid their big sisters, and the firing line was disrupted. Cochrane, unsure of the damage, ordered a withdrawal. He signaled to the infantry on shore, but from here accounts are hazy and contradictory. Though the naval captains all agree that the signal was sent to Taylor, the soldiers on shore do not seem to have seen the signal, or, as Taylor would later state, he heard the gunfire and assumed that the seaborne assault was ongoing.

Whatever the case, Taylor would continue with his assault. His 1st Brigade under Brown, freshly rested after the fighting at Alewife Brook the previous day, led the way from their camp. They marched towards the outer entrenchments of Fort Preble, and with the thunder of guns they began their attack on the earthworks. However, as they advanced, skirmishers in the lead and the engineering parties pushing onwards, it was discovered that in the haste of the advance the scaling ladders meant to overcome American redoubts had been left on the beach[5]. Predictably, the assault stalled, and a crucial half an hour was spent milling about in confusion as Brown’s brigade halted before the earthworks. During that time the American defenders rained musket fire and grapeshot down upon them, inflicting great casualties. The arrival of the 3rd Brigade merely added to the troubles and soon Taylor was forced to order a retreat.

Pennefather would spend the remainder of the day attempting to sort out what had gone wrong between the navy and the army, while moving his second division under Trollope forward to contain any moves by the American garrison. Even once the whole fiasco had been established; there were two crucial days of arguments between Pennefather’s staff, and the naval officers. Warrior needed repair and so would be required to retire, and Johnstone was determined not to send his ships in to an unknown situation, and requested that the American defences be scouted thoroughly lest his ships discover any further unpleasant surprises.

In the end it seemed William’s sacrifice at Alewife Brook paid off. Even by the end of the day on the 13th reinforcements were arriving by train, and by the dawn of the 16th Smith’s division had marched to the American defences on the Stroudwater River, and a day later Casey’s division arrived and began harassing Pennefather’s flank.

Pennefather moved swiftly though, turning Trollope’s division to engage the Americans…

…the end result though proved that Pennefather, despite his speed and audacity, had been unable to remove the defenders from Fort Preble. Johnstone remained adamant that the torpedoes would need to be cleared, and overall the British effort bogged down and would become a siege. The short, sharp, maneuver warfare in May had seen the British unable to completely cut the rail lines, but the Union unable to dislodge the British positions around Portland.

The British gamble had failed…” – Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV

-----

1] You might remember him from last time.

2] The Union’s coastal defences were pretty awful in this period. Though the war was ongoing and historically they had no need to man the defences since the Confederate navy was incapable of threatening Union ports. Here though they obviously do, and with access to the records of the time we can see that both the state of Maine, and the Engineers considered Portland a strategic necessity to defend. I have no doubt the need to defend the terminus of the Grand Trunk would be readily apparent and so receive lots in the way of guns as quickly as they could. That doesn’t mean they will get all the guns however, there’s still many other places of strategic import to consider.

3] Thought you’d heard the last of him did you?

4] With the exception of Franklin, these are all ships under construction in the period in question OTL. The smaller ironclads though are more of a stopgap measure and have less in common with OTL's Passiac Class and more with the original Monitor for the sake of expedience, so their construction and design is almost stroke for stroke that of the Monitor, including being armed with the 11inch Dahlgren's rather then the 15inch.

5] Now this is set in historic precedent. The lack of ladders became a problem both at New Orleans in 1815, and the Great Redoubt in 1856, and the assaults on the Great Redoubt failed multiple times. If this all went perfectly things would be going rather too well for the British at this juncture.

Last edited:

Saphroneth

Banned

I'm not so sure they would...Here though they obviously do, and with access to the records of the time we can see that both the state of Maine, and the Engineers considered Portland a strategic necessity to defend. I have no doubt the need to defend the terminus of the Grand Trunk would be readily apparent and so receive lots in the way of guns as quickly as they could.

http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/c...o=waro0122;didno=waro0122;view=image;seq=0967

Totten here writes the state off as seeing that improvements are not necessary or desirable.

In any case, the geography makes it impossible to successfully defend without entirely new forts being thrown up - Forts Preble and Scammell cover the channel between the mainland and Horse Island, but there's several other channels. (In fact, since the tide rises up to 10 feet during spring tide as per Capt. Washington, any route not entirely dry at low tide is a channel for all gunboats and gunvessels.)

Sloops and gunboats could pick their way through the Cousins-Chebeague strait, or the Chebeague-Long strait, without coming within 7km of an enemy fort - then they can get a direct sightline on it with heavy rifles or land them on the islands (e.g. Mackworth, Great Diamond) for a steady base. Once there's heavy rifles able to fire on a Second System Fort that's all she wrote.

RodentRevolution

Banned

Well I think the mine, which was probably a very lucky mine was the crucial piece of bad luck but these things have happened in war. That said I would assume that both sides will commit to the Siege of Portland. An interesting, in the hair raising sense, episode.

Last edited:

Saphroneth

Banned

Oh, dear... I think this predates any CS success with such mines, and they were far more interested. Most US officers saw mines as tedious and useless:At 10:23am, Warrior’s unarmoured bow struck a torpedo with a violent explosion tearing through her front compartments.

-Damn the TorpedoesWelles left most ordnance matters

to his ship captains and allowed mine countermeasures to be developed and

applied ad hoc throughout the fleet.” Each captain designed his own

protection devices, if any, and most officers found the presence of mines more

tedious than hazardous, at least at first. As one officer rashly remarked early

in the war, “All contact torpedoes are liable to be removed and overcome by

ordinary in enuity, if it is allowed full exercise by uninterrupted

operations.”” Naval ordnance expert Captain John A. Dahlgren noted that

“so much has been said in ridicule of torpedoes that very little precautions

are deemed necessary.”13 Such Union attitudes changed only with recurring

demonstrations of the effectiveness of such primitive devices, particularly in

increasingly frequent Confederate guerrilla operations. Some Union

commanders became unwilling to risk their ships in mined waters without

direct orders and often found rumors of Confederate mining in the eastern

rivers sufficient reason for inactivity.

The Confederacy, on the other hand, actively funded mine warfare as an

inexpensive alternative to traditional naval defense for a nation without much

of a navy. Confederate inventors Matthew Fontaine Maury, Beverly Kennon,

Hunter Davidson, and Gabriel J. Rains experimented with torpedoes and

earned renown for their firing mechanisms. Maury’s particular interest in

electrically-fired mines led to the creation of the Confederate Submarine

Battery Service, which developed and detonated most of the controlled mines

planted during the Civil War.

Davidson relieved Maury in command of that service, and Maury spent

most of the war perfecting his electrical mines in English laboratories. As his

work progressed, Maury‘s mines became more lethal. In October 1862 the

Confederate Congress funded a separate Torpedo Bureau. This army unit was

headed by Rains, who had been experimenting with land mines since the

Seminole Wars in Florida in 1840 and had already mined the tributaries of

the James River with experimental contact mines.

In any case, the British wouldn't just ignore them - they had a very successful system used in China of "bow watches" (same source), used launches to look for them, and they had cleared plenty of Russian contact mines without a single casualty in the Baltic.

This isn't to say you're being biased, just that (as with my own TL) a mine actually damaging a British vessel in this time period is very much a matter of both luck and considerable ahistorical tweaking!

RodentRevolution

Banned

This isn't to say you're being biased, just that (as with my own TL) a mine actually damaging a British vessel in this time period is very much a matter of both luck and considerable ahistorical tweaking!

Well to be fair he is shooting Union General Officers left, right and centre

A definite setback, but it still favours the Anglo-Canadians. Every Union soldier not sent to Kingston/Montreal increases Canadian survivability. Plus, those soldiers in the Maritimes were fairly safe from invasion anyways, they may as well go on the offensive. Portland would be worth the gamble!

Last edited:

Saphroneth

Banned

That's not a matter of luck or considerable ahistorical tweaking, it's a matter of having Enfields.Well to be fair he is shooting Union General Officers left, right and centre

Besides, shoot enough Union generals and someone competent might turn up - it was a pretty sorry lot in early 1862.

I'm not so sure they would...

http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moawar;cc=moawar;q1=portland;rgn=full text;idno=waro0122;didno=waro0122;view=image;seq=0967

Totten here writes the state off as seeing that improvements are not necessary or desirable.

Actually this letter is writing off the development of roadways to improve the defences of landward frontier, which Totten dismissed as indefensible (for obvious reasons as shown in Chapter 12 of TTL). The letter then refers back to the comments he made on the defences necessary and his comments about them in his letters from earlier in January and February (the first of which is here) and therein he lays out his concerns for defence and why they are important to do so.

In any case, the geography makes it impossible to successfully defend without entirely new forts being thrown up - Forts Preble and Scammell cover the channel between the mainland and Horse Island, but there's several other channels. (In fact, since the tide rises up to 10 feet during spring tide as per Capt. Washington, any route not entirely dry at low tide is a channel for all gunboats and gunvessels.)

Sloops and gunboats could pick their way through the Cousins-Chebeague strait, or the Chebeague-Long strait, without coming within 7km of an enemy fort - then they can get a direct sightline on it with heavy rifles or land them on the islands (e.g. Mackworth, Great Diamond) for a steady base. Once there's heavy rifles able to fire on a Second System Fort that's all she wrote.

You don't need entirely new forts. Batteries on Hog Island, with obstructions and torpedoes would be a ready deterrent for gunboats. If they're caught under the guns of the forts and can't maneuver it'll end badly for the gunboats, even a direct hit from an 8inch shell would be a bad day. The Chinese managed to hit the weaknesses of these gunboats once (with rather less than modern guns) and in the Crimean War the gunboats were always operating in conjunction with larger vessels when they went up against the Russian fortifications.

On their own, the gunboats can't demolish the forts.

RodentRevolution

Banned

That's not a matter of luck or considerable ahistorical tweaking, it's a matter of having Enfields.

Besides, shoot enough Union generals and someone competent might turn up - it was a pretty sorry lot in early 1862.

The Enfields or rather having men who know how to use them certainly help but it still takes a certain amount of luck to pick out the general from among his staff. Besides as Gunslinger noted this setback still obtains most of the important of objectives and now the British know to expect mines...lucky experimental fluke or not...they will focus considerable force by land and sea on the operation.

Well I think the mine, which was probably a very lucky mine was the crucial piece of bad luck but these things have happened in way. That said I would assume that both sides will commit to the Siege of Portland. An interesting, in the hair raising sense, episode.

Well the coin has to fall the other way sometimes. And a combined land and naval attack is a tricky operation at the best of times. I don't see it as incredibly unlikely that something would go wrong. The blockships in Sevastopol made the Royal Navy balk at assaulting the harbor, necessitating a lengthy siege, and here I would see this twist of fate as enough for the Royal Navy to insist on mine sweeping operations until they went in again.

Johnstone also did not serve in the Russian War, so his familiarity with torpedoes would be nil really, making him much more wary. If they could put a hold in Warrior what could happen to an unarmored ship?

Well to be fair he is shooting Union General Officers left, right and centre

Well to be fair to this one, he did die only a few months earlier than he did historically

Threadmarks

View all 158 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation Chapter 133: Alarms Ignored

Share: