Chapter 30: Williams Goes South

"Because I will cut off from you the righteous and the wicked, therefore My sword will go forth from its sheath against all flesh from south to north.” - Ezekiel 21:4

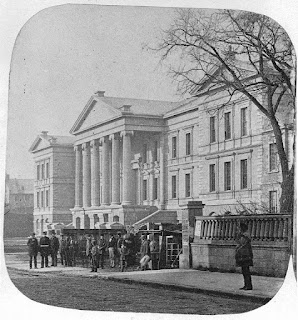

“The successes in Maine, and the perceived shabby state of the Union Army brought matters to a head in Canada. In London there had been a sense of complacency regarding Canada, so long as Kingston remained secure and William’s army was south of Montreal there seemed little chance of the British facing a serious reversal. With the campaign season of 1862 drawing to a close, it was seen as necessary for the British to preclude the chance of a fresh invasion come spring 1863. To avoid that, there was one post in American hands which had to be taken, Fort Montgomery in northern New York.

From here it was obvious an American army could shelter, build up supplies, and even collect gunboats for a march north. Though there had been discussions about seizing it at the outset of the war, the objections of Williams and the resources diverted to the campaign against Portland had seen such an idea shelved. The victories on the Lacolle River and the reverses of the American thrusts north at Napierville had merely added to the complacency of British planners.

Now though, London sought another victory, and intended to make their Canadian position utterly secure…” - Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV.

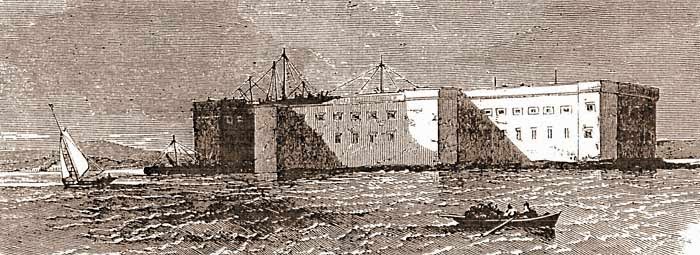

Fort Montgomery, 1869

“One of William’s objections early in the war had been a lack of gunboats to support his troops when marching south to the shores of Lake Champlain. In early 1862 only a few converted gunboats had been available to support him, but by August over a dozen Russian War and new build gunboats were in the waters of the St. Lawrence. However, Collinson, commanding the St. Lawrence Squadron, was concerned about the lack of ironclads to support his squadron.

Some basic intelligence had filtered to the Admiralty regarding the our ironclad program, but details were slim until information from a pro-British ship builder filtered across the Atlantic in the fall. Palmerston, in his characteristic nature, demanded ironclads for the St. Lawrence while berating Somerset about the need for their speedy construction.

Palmerston’s anger was somewhat misplaced. Designs had been discussed in the halls of the Admiralty since January. While at first as purely theoretical matters, but as February wore on into March and war broke out, the discussion changed to practical construction rather than theory. Captain Coles, at that point the foremost ironclad designer in the Royal Navy, championed a riverine design similar to the first Monitor, which he claimed would be superior to any broadside ship. This was hotly contested by Somerset and Watts[1]. Somerset, predictably opposed it on matters of cost, while Watts opposed it on matters of time.

Watts’s argued that experimentation and construction would take much longer than the time frame imposed by the government. Coles argued that previous tests done would allow him to create a prototype which could be quickly emulated and shipped to North America by the fall. When the War Cabinet inquired how many weapons such a vessel could mount, Coles estimated three heavy Armstrong guns would be the maximum. Palmerston balked at this “armored peashooter” and demanded some swifter design.

Watts, who had helped design the Warrior, pointed to the ironclad batteries designed for the Crimea as his example. He declared that a smaller vessel, perhaps one third the tonnage, would be most suited to riverine warfare in North America. When asked how he could expedite the process he suggested building them in Britain, but knocking them down and shipping them by sea to North America. He proposed an ambitious building schedule for these vessels, constructing them in only 90 days. Palmerston and Somerset approved, and so the River Class ironclad was born.

Based on the Aetna Class built for the Russian War, they weighed in at 700 tons with an armament of seven guns. Six in a broadside and a single bow gun, which Watt argued was useful in the confines of the St. Lawrence or on the Lakes themselves. The Navy contracted for six vessels at first and the Lawrence, Yamaska, Richelieu, Ottawa, Rideau, and Ontario were built. Beginning construction in April, they underwent trials in July before being knocked down and convoyed across the Atlantic in August.

They were relayed to the yards in Montreal where they were rebuilt and launched officially with a mix of British and Canadian crews…

Lawrence, Yamaska, and Richelieu were dispatched to Fort Lennox, while Ontario, Ottawa, and Rideau ran the St. Lawrence to Kingston…

Welles and the Board of National Defense had realized since the outbreak of the war that some naval force would be needed on Lake Champlain, if not for offensive operations at least to prevent it from being used as a highway of invasion by the British. Joseph Smith had experience from Lake Champlain, and understood the necessity of an armed force of ships on the lake.

Fortunately, they had the example of the Western Gunboat Flotilla to draw upon, and numerous displaced naval officers and river boatmen to act as crews and gunners for the emerging squadron.

Command of the squadron itself would be gifted to Captain John A. Winslow. He had joined the navy in 1827 and was commended for gallantry during the Mexican War. Serving aboard vessels in the Pacific and Atlantic he had also served in the Boston Navy Yard. With the outbreak of the war in the South he had gone west and been present on the Mississippi. He had labored alongside Eads and Pook to outfit gunboats for service on the Mississippi River, eventually being given command of the gunboat Benton after serving with Foote’s squadron at Fort Henry. This service, and his friendship with Foote, earned him a recommendation to the Board, and when names were cast around for a commander for Lake Champlain, he was soon on his way north with Eads in April…

In the endeavor to equip and build new vessels would be supported by the engines of industry in New York. Two individuals in particular would throw all their industrial and political clout into the project. Those would be John Gregory Smith, and John Flack Winslow[2].

Winslow was the titan of the iron industry in New England, owning Rensselaer Iron Works and the Albany Iron Works with his partner Erastus Corning, having a corner on the iron market in the United States. With ties to railroads and rolling mills this considerable duo put their weight behind the war effort, and Winslow in particular put his influence into the ironclad program. He partnered with John Ericsson for the original Monitor, and would sponsor and supply those being built in New York. With this experience he turned towards supplying the new “Lake Champlain Squadron” with whatever they needed to construct vessels. Providing for facilities at Troy, Albany, and Shelburne he worked closely with the arriving officers to lay down vessels for the navy. He had a personal stake in the project as Vermont was his home state.

Smith, another Vermonter, was a railroad owner whose home town was St. Albans. His support was also based on a personal connection to the events of 1861. When the raiders had struck he had been away from home, but the raiders had attempted to burn his home with his wife Ann inside. She had confronted them with a pistol and they had fled, but this event left him with a burning desire to “give the British and South their due” and had thrown his not inconsiderable political weight behind the war effort[3]. He was the trustee of the Vermont and Canada Railroad, and using that position would effectively give ownership of the railroad to the military for the duration of the war. Lobbying local and national interests he ensured that all the resources of his state could be thrown behind both the Army of the Hudson, and Winslow as he attempted to build a naval squadron from scratch.

Already in March and April local steamers had been commandeered to serve as an ad hoc squadron, five ships had been assembled and armed. United States(4), Boston(2), Burlington(2), General Greene(2), and Shelburne(2) had all been strengthened with timber, and armed with guns shipped from across New England to make up for the lack of existing naval stores. Eads had set up slips at Troy and Albany to provide for the construction of three new “City Class” ironclads. However, they were slightly smaller than their Mississippi sisters, carrying only 10 guns, and with their hulls protected, but their sterns remained unprotected as with Eads original design.

Four vessels, all with eight guns, were launched between July and August, two named for their places of construction, Albany and Troy, and two, at Smith and Winslow’s insistence, after the places attacked by the rebels. The USS St. Albans was launched in July, but her sister was held up from commissioning until August as her proposed names, Franklin and Vermont, were both already in use by the navy. Finally a compromise was reached and the USS Plattsburgh joined her sisters on Lake Champlain…” The Naval War of 1862, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., New York University Press, 1890

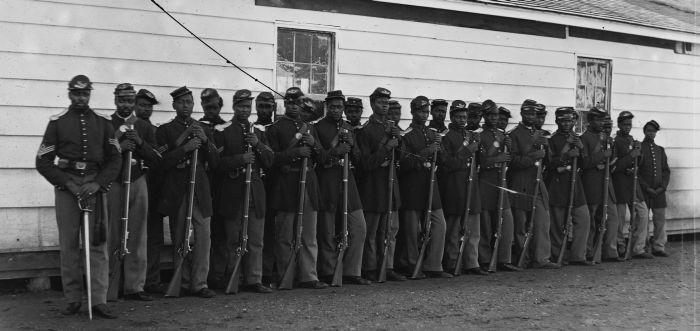

“The Army of the Hudson had taken a series of hard knocks since May, and had lost over 10,000 men in the process, alongside numerous brigade and division commanders. As such, despite Sumner’s aggressive exhortations, the morale of the army was at an all time low. Men were despondent, and desertions were a common occurrence, with Sumner having to take extreme measures to counter the flight of nervous troops. From June on he repeatedly wrote Washington requesting more supplies and more men to hold his position. He firmly believed that it was only British inaction which kept Fort Montgomery secure.

With the fall of Portland, Stanton and Lincoln determined that something must be done to shore up their armies in Canada and New York. The Army of New England was deemed too weak to take the offensive into Maine (and with the Royal Navy supreme on the coast it was hazardous to make the attempt) and so they ordered two divisions from that army to the border.

Keye, the remnants of the militia and William’s division, would remain around Portland to pin the British in place with some 20,000 men. The 16,000 men of William F. Smith’s 3rd Division and Silas Casey’s 4th Division would be transported by rail from Maine to New York. The divisions movement would take near a month by rail, but come September 15th they had arrived at Albany and were being shipped up the Hudson.

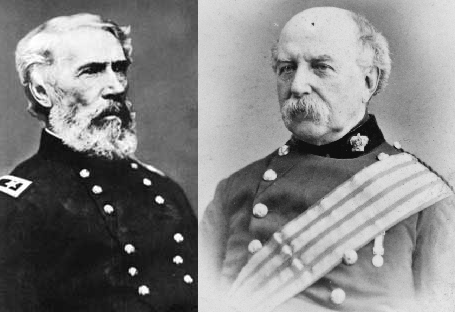

Sumner now took the opportunity to reorganize his command. With Washington’s approval he divided his army into two Corps formations. Keeping the original designation for his army, II Corps, he placed the divisions of Howard, Burns, and Smith under the command of Israel B. Richardson. The newly created XVII Corps, with the Divisions of Foster, Casey, and Burns, under Ambrose Burnside.

With the 16,000 men from Maine, Sumner now had some 60,000 men under his command…” - The Union’s Shield: The Army of the Hudson, Donald Cameron, University of New York 1930

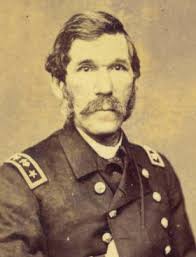

Burnside and Richardson

“The Army of Canada, now four divisions strong, was deemed by Williams to be strong enough to take on a foe who he believed was demoralized, and at the very least numerically equal to his. Though his cavalry had been unable to completely penetrate the thin screen that Sumner had put forward, reconnaissance from the lake showed that Fort Montgomery remained incomplete, and the Americans seemed to have not thrown up few fieldworks of their own.

William’s determined that his men should cross the border marching toward Main Street along the rail line, with one column aiming for the village itself and another aiming for Fort Montgomery. From there they would seek to engage the Americans directly, with the support of Collinson’s squadron on the Lake. Scouting determined that a series of blockhouses had been thrown up along the roads, one set covering Main Street, while another sat at Waldon’s Farm covering the extreme left of the America position. In theory, these were covered by the forts guns and so the British determined to begin their attack with a bombardment of the fort using the army’s heavy guns. From there the infantry would advance and drive the Americans from the field.” - Empire and Blood: British Military Operations in the 19th Century Volume IV.

-----

1] Isaac Watts, Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy until 1863

2] Yes there are too many John’s in this picture, but try to remember their last names most prominently!

3] You can’t make this up! Though this is not what actually happened, his hometown was St. Albans and apparently his wife was threatened by the raiders. A fitting inclusion I think.

Last edited:

.jpg/220px-George_Wright_(Army_General).jpg)