Ok Sherman, you can march north now to Richmond. The place is gonna be lit once you and Grant meet up there.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"Marching through Virginia does have a nice ring to it....Ok Sherman, you can march north now to Richmond. The place is gonna be lit once you and Grant meet up there.

Imo He probably won't be under arrest long enough for him to catch something

Oh, you'd be shocked, SHOCKED I tell you, how quickly a prisoner can catch pneumonia in a situation like this

Or typhus from unsanitary bedding. Other terminal ailments available too.Oh, you'd be shocked, SHOCKED I tell you, how quickly a prisoner can catch pneumonia in a situation like this

I think the main outcome of all of this, aside from a much bloodier end to the confederacy, is that there won't be a single Lost Causer movement, there will be several.

If you're a poor white southerner or sympathetic northerner you might look fondly at the "honourable" Breckenridge and Lee who cared about the common man and did the best they could but were frustrated at every turn by the selfishness of the planters who lost the war for the south then stabbed Breckenridge in the back and prevented an honourable peace.

On the other hand, if you sympathise more with the planters and their version of history, the south would have been triumphant were it not for the cowardice and sabotage of Breckenridge and his incompetent, tyrannical government that destroyed the confederacy from within and doomed them to defeat.

And I think that is going to be vital for the post-bellum south. There won't be a united narrative to rewrite history around. There won't be a single set of southern heroes to lionise and hagiographise. Instead there will be competing narratives and competing casts of heroes and villains. And, crucially, every variation of the Lost Cause will have its own stab in the back myth which pits them against other southerners. All that is going to stand in the way of the coordinated rewriting of history and mythologising that we saw OTL. There definitely won't be monuments to Breckenridge and Lee in the same places as monuments to Jackson and Davis. And all of that should make it much harder for reconstruction to be overturned within a generation as it was OTL - the southern political elites will be fighting each other over who's to blame rather than working together, and that will make a huge difference.

If you're a poor white southerner or sympathetic northerner you might look fondly at the "honourable" Breckenridge and Lee who cared about the common man and did the best they could but were frustrated at every turn by the selfishness of the planters who lost the war for the south then stabbed Breckenridge in the back and prevented an honourable peace.

On the other hand, if you sympathise more with the planters and their version of history, the south would have been triumphant were it not for the cowardice and sabotage of Breckenridge and his incompetent, tyrannical government that destroyed the confederacy from within and doomed them to defeat.

And I think that is going to be vital for the post-bellum south. There won't be a united narrative to rewrite history around. There won't be a single set of southern heroes to lionise and hagiographise. Instead there will be competing narratives and competing casts of heroes and villains. And, crucially, every variation of the Lost Cause will have its own stab in the back myth which pits them against other southerners. All that is going to stand in the way of the coordinated rewriting of history and mythologising that we saw OTL. There definitely won't be monuments to Breckenridge and Lee in the same places as monuments to Jackson and Davis. And all of that should make it much harder for reconstruction to be overturned within a generation as it was OTL - the southern political elites will be fighting each other over who's to blame rather than working together, and that will make a huge difference.

Northern reaction to the coup is going to be interesting. They will say that it is good that there is chaos in the government because that way it's easier to be toppled. On the other hand, they may have to wonder just what kind of awful things will happen, what will be the plans of these new elites? Maybe your rumors will come about an attack on New York or something like actually was considered in our timeline.

Wall street, meanwhile, will either jump ship right away or wait till near the end. I suspected will be whenever some really awful order comes, if he just is defeated and then goes home that won't be the same as if he actually jumps to the other side. I mean come after all, if he is just defeated one suspects he would just leave in disgrace.

Would he see some order to destroy all the surrounding area as totally without honor? Possibly. I'm sure we will see that in the next update. It will probably come with military to feed also, it seems as though, while the siege of etersburg started later in this time line, it is actually going better. Partly because of the chaos, partly because there is just a lot less as far as rations and munitions and things.

Wall street, meanwhile, will either jump ship right away or wait till near the end. I suspected will be whenever some really awful order comes, if he just is defeated and then goes home that won't be the same as if he actually jumps to the other side. I mean come after all, if he is just defeated one suspects he would just leave in disgrace.

Would he see some order to destroy all the surrounding area as totally without honor? Possibly. I'm sure we will see that in the next update. It will probably come with military to feed also, it seems as though, while the siege of etersburg started later in this time line, it is actually going better. Partly because of the chaos, partly because there is just a lot less as far as rations and munitions and things.

To start?

Absolutely not. The only two emotions I can imagine being felt in the North are schadenfreude with perhaps a bit of anxiety due to the unknowns of how this might affect the war.

But in the future? I'd never call it sympathy, but he does seem like an interesting enough figure here that he'd be a good target for eventual reevaluation. Still a (former?) slaveholder, still an anti-revolutionary, still the Confederacy's first President, and yet only an ally of the planter class rather than a member, and ultimately betrayed by them when he realized the war was irreversibly lost. And, as someone else has said, that contrast between him and those who arrested him could be useful in the future.

There's not going to be any 'graceful' handshake at appomattox to end the war here. The planters and hardliners are so unwilling to part with their status and wealth that they'd rather burn the entire South down than concede defeat, and apparently they won't let the opinions of other southerners get in the way.

Yeah there will be no Grant/Lee courthouse handshake surrender here. The south ITTL will most likely be fighting to the absolute bitter end.

I imagine every tactic conceivable is being implemented by the military junta to make the war as painful as possible for the union

That will in turn make the Northern reprisal brutal and Reconstruction Radical. Brilliant.Yeah there will be no Grant/Lee courthouse handshake surrender here. The south ITTL will most likely be fighting to the absolute bitter end.

I imagine every tactic conceivable is being implemented by the military junta to make the war as painful as possible for the union

This idea of 'these are our brothers, don't rejoice at their fall' will be thrown out to the trash where it belongs. Let the rebel scum burn.

Honestly with the coup and the current divisions in the South, I don’t think it’s outside the realm of possibility that we might see some outright battles between a few Confederate army/forces erupt, between those in the Confederacy like Longstreet that support Breckinridge and consider the coup illegal and the junta illegitimate and those that support the coup and junta, which certainly will further division in the South post-war.

Plus I’d certainly love to see a actual Longstreet vs Jackson battle happen.

Plus I’d certainly love to see a actual Longstreet vs Jackson battle happen.

Last edited:

The CSA having their own civil war and secessions would be likely, along with bringing further humiliation to them.Honestly with the coup and the current divisions in the South, I don’t think it’s outside the realm of possibility that we might see some outright battles between a few Confederate army/forces erupt, between those in the Confederacy like Longstreet that support Breckinridge and consider the coup illegal and the junta illegitimate and those that support the coup and junta, which certainly will further division in the South post-war.

Plus I’d certainly love to see a actual Longstreet vs Jackson battle happen.

Such a satisfying chapter. God I can’t wait to see the south burn to the ground like it should have and to see the north finish the job like it should have. Sometimes enemies must be crushed, utterly.

Amusingly enough the only hesitation I have in seeing Jackson and Davis get the noose is that it would butterfly my boyfriend who is a direct descendant of both (and the amount of gravespinning they would do at seeing him and his views and his life would power the entire eastern seaboard).

Amusingly enough the only hesitation I have in seeing Jackson and Davis get the noose is that it would butterfly my boyfriend who is a direct descendant of both (and the amount of gravespinning they would do at seeing him and his views and his life would power the entire eastern seaboard).

A *true* Civil War. My AP US History Teacher *refused* to call it the Civil War unless he actually had to. He wasn't at all a confederate sympathizer, he just had a classical view of what a Civil War was. To him, the English, the Spanish and to some extent the Russians had a Civil War, to him, the only Civil War in North America in the 1860s was in Mexico. What we called the US Civil War was a Failed Southern War for Independence, he saw *far* more similarities to the US War for Independence (which wasn't a Revolution, the French had one of those in 1789) than to the English "War of the Roses".The CSA having their own civil war and secessions would be likely, along with bringing further humiliation to them.

(BTW, got a 4 on the AP US History exam, and give him a lot of the credit)

Sweet. I remember taking AP US History too. Though I suppose calling it the Southern War of Douchebaggery might be more accurate. Very interesting thought there though seeing the Confederares dissolve into biting one another's heads off makes for dark humor.A *true* Civil War. My AP US History Teacher *refused* to call it the Civil War unless he actually had to. He wasn't at all a confederate sympathizer, he just had a classical view of what a Civil War was. To him, the English, the Spanish and to some extent the Russians had a Civil War, to him, the only Civil War in North America in the 1860s was in Mexico. What we called the US Civil War was a Failed Southern War for Independence, he saw *far* more similarities to the US War for Independence (which wasn't a Revolution, the French had one of those in 1789) than to the English "War of the Roses".

(BTW, got a 4 on the AP US History exam, and give him a lot of the credit)

To be fair, I’m pretty sure none of us would exist in this alternate timeline, simply due to the butterfly effect. Pretty much anyone born after the POD probably doesn’t exist, if we’re being realistic.Such a satisfying chapter. God I can’t wait to see the south burn to the ground like it should have and to see the north finish the job like it should have. Sometimes enemies must be crushed, utterly.

Amusingly enough the only hesitation I have in seeing Jackson and Davis get the noose is that it would butterfly my boyfriend who is a direct descendant of both (and the amount of gravespinning they would do at seeing him and his views and his life would power the entire eastern seaboard).

I don't believe its in character for Jackson of johnston to join an effort to overthrow the Government.they were probably evil men but not THAT type of evil if it makes sense

.I also don't like Lee dying before the defeat as now people ittl would say "if only Lee lived" and the imagery of the Virginian gentlemen surrendering to the shopkeeper is an important part of the imagery around the end of the war.Althorugh I also like him as a "Character " I would say .

I beg of you to understand that the chapter was still excellent brillant and overall great and I only am afraid that to point out everything great with it would take a couple of hours but the fundamental theme that a society based off evil is fundamentally flawed and leads to failure of morals and sense in every part of its "nation" is striking.

.I also don't like Lee dying before the defeat as now people ittl would say "if only Lee lived" and the imagery of the Virginian gentlemen surrendering to the shopkeeper is an important part of the imagery around the end of the war.Althorugh I also like him as a "Character " I would say .

I beg of you to understand that the chapter was still excellent brillant and overall great and I only am afraid that to point out everything great with it would take a couple of hours but the fundamental theme that a society based off evil is fundamentally flawed and leads to failure of morals and sense in every part of its "nation" is striking.

Well, I don't know about Davis, but by this point in OTL Stonewall Jackson was already dead. So I think your BF will be fineAmusingly enough the only hesitation I have in seeing Jackson and Davis get the noose is that it would butterfly my boyfriend who is a direct descendant of both (and the amount of gravespinning they would do at seeing him and his views and his life would power the entire eastern seaboard).

Perhaps more accurate, but I think the more fascinating discussion was a fairly serious AH discussion as to how many years prior to 1860 would the South have had to jump before the north wouldn't have been able to pull them back.Sweet. I remember taking AP US History too. Though I suppose calling it the Southern War of Douchebaggery might be more accurate. Very interesting thought there though seeing the Confederares dissolve into biting one another's heads off makes for dark humor.

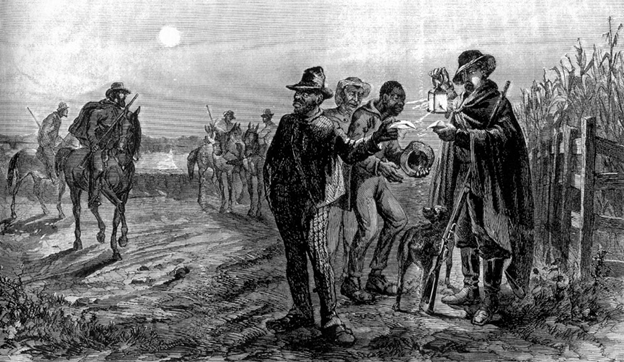

I'm imagining a northern political cartoon of a snake with Breckenridge's head whispering in the ear of an enslaved man and woman.The news that Atlanta and Mobile had fallen, so closely one after the other, brought about a wave of despair throughout the Confederacy. The defiance of both cities had become a symbol of Southern resistance and irrefutable proof that the Yankees could not overcome them – that despite the Union’s overwhelming material superiority the rebels were simply unconquerable. But this confidence made the fall so much harder, for virtually all Confederates had pinned their entire hopes in successfully defending the cities. Thus, their fall seemed like a portent of ruin, a sure sign that their defeat and consequently their destruction at the hands of the Northern radicals was nigh. The deep cracks in Southern society revealed by the war, such as the growing gulf between the planter class and poor Whites, were compounded by economic disaster, widespread hunger, and military catastrophe, bringing the Confederacy to its greatest crisis. Sacrifices and privations that had seemed tolerable for the cause were now seen as meaningless, and whereas the possibility of ultimate victory had sustained many through previous hard times, now defeat seemed inevitable. The leaders of the South, staring their undoing in the face, now had to grapple with the question of whether it was worth keeping up the struggle, or if the time to surrender had come at last.

In truth, even before those shattering defeats, the Confederates had been experiencing hard times on account of a continuously deteriorating economic and logistical situation. Prospects of victory could not produce more food or goods, and the defense of points such as Atlanta or Mobile was not enough when large tracks of the Confederacy remained under Federal occupation. As a result, throughout the last months of 1863 and the first half of 1864, the economic situation remained bad in the South. “The FAMINE is still advancing, and his gaunt proportions loom up daily, as he approaches with gigantic strides,” wrote John Jones. Often, there was not enough food for civilians and soldiers. “We gi no beef now,” a Virginia soldier admitted to his siblings, “and not quite half rashons of bacon and sometimes it is spoilt so we cant eat it.” Lee attempted to set an example to his men by limiting the serving of meat and mostly eating boiled cabbage himself. But keeping up morale proved enormously hard, especially as letters kept arriving that depicted harsh conditions at home and bitterly denounced the government’s policies.

Taxation was a notable source of contention, for taxes disproportionately impacted the poor, while conversely the rich could mostly afford them and saw their principal assets, land and slaves, go mostly untouched. A private believed the situation unjust, denouncing how “the tax collector and produce gathere[r] are pushing for the little mights of garden and trash patches . . . that the poor women have labored hard and made.” The policy of impressment created even more discontent. Naturally, the main point of contention was the belief that, just like with the taxes, the rich didn’t pay their share. “There is a great wrong somewhere,” believed the Alabaman Sarah Espy, “and if our confederacy should fall, it will be no wonder to me for the brunt is thrown upon the working classes while the rich live at home in ease and pleasure.” Even when the Army forcibly impressed enslaved laborers, the government pledged to pay the owners, to the point that Alabama paid slaveowners 30 dollars a month for each impressed slave working on Mobile’s defenses, while White soldiers received merely 11 dollars per month. “Patriotic planters would willingly put their own flesh and blood into the army,” observed Senator Wigfall acidly, but if “you asked them for a negro,” it was like “drawing an eyetooth.”

These experiences reinforced the view that the Confederacy was created for the explicit benefit of the planter aristocracy, and that there was no reason for a poor man to fight a rich man’s war. After the liberation of East Tennessee, Union General Joseph Reynolds observed that many former rebels now resented how “their more wealthy and better informed neighbors insisted upon the poor people taking up arms to oppose the [federal] Government that they had been taught to love,” all “for the defense . . . of a species of property with the possession of which they had never been burdened, and were not likely to be.” A North Carolinian echoed these thoughts, writing despondently that “thousands believe in their hearts that there was no use breaking up the old Government,” and that only those “in high office” or “the large negro-owners” benefited from continuing the war. The Fayetteville Observer, from the same State, had to acknowledge that the people fully understood “that peace and reconstruction would only result in the abolition of slavery,” but since “many . . . owned no slaves, they need not care.”

Cartoon mocking hunger in the Confederacy

Southern masters showed scarce sympathy to those who wavered in their loyalty to the Confederacy. Unionists, an Arkansas editor wrote scornfully, were “the baser sort, drunkards, swindlers and ignoramuses,” the “foolish imbeciles” who advocated for Southerners to return to the Union “like a dog to his vomit.” The plantation mistress Catherine Edmondston for her part believed that all dissenters were “mobs for plunder,” formed by “low foreigners” and incited by Yankee promises of rapine. Still, most rebel leaders recognized that they needed to maintain the support of the poor Whites, and thus attempted to keep up the support for the war by appealing to the base prejudices and racist fears held by the great majority of Southern Whites. They painted near apocalyptical pictures of the future if Southerners accepted abolition and returned to a Union helmed by Lincoln and his radicals. Alongside this rhetorical stroke, the Confederate Army stepped up its repression of Unionism, using bloody and despotic methods to root out the disloyal. Finally, the rebels also engaged in a campaign to shore-up slavery and protect it from a Northern government increasingly committed to emancipation and equal rights. All these events, taken together, have been labelled the “Confederate Counterrevolution,” which sought to stop and reverse the tide of the radical Yankee Revolution.

To prevent the Southern masses from being seduced by the siren song of Reconstruction, rebel leaders lambasted Lincoln’s plans as vengeful tyranny which meant to force Southerners into acquiescing to their own destruction. “Have we not just been apprised by that despot that we can only expect his gracious pardon by emancipating all our slaves, swearing allegiance and obedience to him and his proclamations, and becoming, in point of fact, the slaves of our own negroes?” asked Jefferson Davis. In an address to the Southern people, the rebel Congress similarly denounced Reconstruction as a disaster that had reduced Missouri to “a smoking ruin and the theater of the most revolting cruelties and barbarities,” had put Maryland and Kentucky “under the oppressions of a merciless tyranny,” and had made Louisiana and Mississippi “a new Africa where the Negroes are masters and inflict horrors unseen since those of Saint Domingue.” Lincoln’s amnesty was a worthless, empty promise, and as soon as Southerners accepted, they’d see “the ignominy and poverty of Yankee domination” enforced by a “negro soldier billeted in every house, and negro Provost Marshals in every village.” If Southerners accepted such a peace, concluded the Richmond Examiner, they would soon find that the “horrors of peace” were worse than the horrors of war.

Many Confederate civilians and soldiers echoed the rhetoric of their leaders, and spoke bitterly of the “depraved, unscrupulous, and Godless” Yankees. The diarist Emma Holmes, invoking the “baseness and treachery of the Yankee character,” dismissed Lincoln’s offer of amnesty, and fierily declared that it would be preferrable to see “every man, woman and child perish . . . and our blessed country become a widespread desert than become the slaves of such demons.” The experiences of Reconstruction, especially land redistribution and support for equal rights, only reinforced the fears of elite Southerners and led them to increasingly harsh denunciations. The young Sarah Morgan, who at first vacillated in her commitment to the cause, now called for “War to the death!” after finding that the estate of her family had been confiscated by the Land Bureau, declaring in horror that “I would rather have all I own burned, than in the possession of negroes.”

Such beliefs encouraged envisioning the war as a struggle for existence, strengthening hatred against the Yankees and the advocates of peace. A Texan declared boldly that he would “Massacre” every Yankee “that ever has or may hereafter place his unhallowed feet upon the soil of our sunny South.” A Georgian, furious at the destruction suffered by the South at the hands of the Union Army, believed the Confederates ought to “take horses; burn houses; and commit every depredation possible upon the men of the North . . . I certainly love to live to kill the base usurping vandals.” Whenever they did get the chance to express these sentiments, the results could be appalling. During Early’s raid on Pennsylvania, Southern soldiers “became drunk and mad for plunder,” reported one of them, burning several towns and doing “every thing in their power to gratify their revenge,” while “Early and Lee seemed to disregard entirely the soldiers’ open acts of destruction.” After uncovering “an organized opposition to the war” in an Alabama regiment, the Confederacy staged a large mass-execution which saw the soldiers hurl epithets, trash, and rocks at the “traitors” as they were led to the gallows. And in response to the presence of the pro-Union guerrilla “Heroes of America” in North Carolina, militia and Army units hanged Unionists in sight, held family members hostage, and even tortured wives and daughters to draw out insurgents.

“The Confederate military authorities aggressively fostered a culture of fear to stamp out dissent,” historian Elizabeth R. Varon states. “Confederate soldiers and home guardsmen recounted wholesale roundups or massacres of deserters, conscript evaders, and Unionists.” This repression was justified by Confederates who pointed at guerrillas that committed “deeds of violence, bloodshed, and outlawry” to resist rebel rule, sapping Confederate resources and exposing deep cracks in Southern society. Singularly worrying and successful was the campaign led by Newton Knight in Jones County, which was especially distressing because Knight’s bands, and many others as well, promoted elements of class warfare. Knight, for example, targeted the agents that collected the hated tax in kind and distributed the captured food among the hungry. Edmondston sneered that all these traitors were “poor ignorant wretches who cannot resist the liberty to help themselves without check to their neighbors belongings.” These condescending feelings, widely shared by most elite Confederates, only demonstrate the lack of understanding that prevented the Confederacy from ever fully suppressing Unionist dissent.

Newton Knight

Another element that terribly disquieted Confederates was the growing solidarity of White Southern Unionists with the freedmen and fugitive slaves. Knight’s band was helped by “slaves [who] brought them food and information,” while other guerrillas sheltered fugitive slaves, often freed the enslaved during their raids, and then cooperated with them while ruling their fiefdoms, with at least one leader declaring slavery “an evil thing,” and proclaiming that his objective was “freedom to all man kind.” During McPherson’s march through northern Alabama, the Federal commander found that Unionist bands had joined with the Black laborers to drive out many landowners, and then they had divided the land equally, “the Negroes receiving as much as the white Union men.” To be sure, many Unionist guerrillas remained dreadfully racist, and opposition to the Confederacy by no means assured a conversion to abolitionism, much less support for racial equality. But the simple fact that there were White men cooperating with the enslaved threatened the racial hierarchy of the South and seemed to prove, for committed rebels, that a Union victory would mean not merely the overthrow of slavery, but the overthrow of White supremacy as well.

The fact that the enslaved were ready to support anti-Confederate insurgents and the Union Army proved to the planter aristocracy that their belief that the enslaved were happy and loyal was deeply mistaken. By 1864, Confederates identified Black people as their “open enemies,” and showed they were ready to resort to violence to maintain their control. “Most slave owners greeted their sudden loss of accustomed mastery with outrage and vituperation,” explains Bruce Levine. “This was . . . a challenge to and rejection of their most basic views, values, and identities. Their ‘people’ had betrayed them—had repaid their masters’ many kindnesses with treason.” As a result, enslavers adopted appalling methods to punish the defiant. Edmund Ruffin punished the slaves who had fled by selling their families, while a Mississippi provost marshal executed around forty fugitives. In Arkansas another master warned his slaves that “if them Yankees . . . get this far . . . you all ain't going to get free by them because I going to line you on the bank of Bois d'Arc creek and free you with my shotgun!”

Enslavers justified their brutality by signaling how Black people were ready to welcome the Federal armies and help them in their conquest of the South. Harsh repression was necessary, said the Reverend Charles Colcock Jones, because those slaves who “absconded” would then go on to aid the Yankees. “They know every road and swamp and creek and plantation in the county, and are the worst of spies,” exclaimed Jones. “They are traitors who may pilot an enemy into your bedchamber!” Catherine Edmondston’s sister was “so disgusted” by such reports that she sometimes believed that they would be more successful if “there was not a negro left in the country.” Yet she said with startling honesty that they had to maintain slavery because “I do hate to work.” Consequently, even as they complained of slave resistance and denounced them as disloyal enemies, Southern masters still wished to preserve slavery and appealed to terror in order to reaffirm and maintain their accustomed control. “Southern civilians looked to the Confederate army to enforce racial control,” explains Elizabeth R. Varon, “and it worked aggressively to catch and punish runaways, and to seize and reenslave blacks through raids of Union-controlled plantations and contraband camps.”

Several States passed draconian laws that prescribed the death penalty for acts of sabotage or allowed “private citizens to shoot-to-kill any slave attempting to escape to Union lines,” but the brunt of enforcement fell on the shoulders of locally organized militias, Home Guards, and slave patrols. These routinely inflicted terror on the enslaved, often resorting to murder or torture to make an example out of the “unfaithful.” “When you take Negroes with arms evidently coming out from the enemie’s camp,” an adjutant instructed Confederate officers, “proceed at once to hang them on the spot.” The freedman Harry Smith after the war remembered how Confederate troops massacred around fifty slaves who had been “on their way to join the Union Army,” while another group had “their ears cut off.” On occasion, rebel soldiers disguised themselves in blue uniforms and called on the enslaved to flee or aid them. If they fell for the ruse, the rebels would reveal themselves and whip, or execute, the gullible slaves. And even as she called this repression a “dreadful doctrine,” the plantation mistress Louisa Alexander called for Confederate soldiers to “scour the whole woods about the neighborhood with the understanding that every negro out will be shot down . . . It is we or they must suffer.”

All these events, says historian James Oakes, show that “just as Union authorities were coming to the conclusion that the slaves were the only reliably loyal southerners, the slaveholders were coming to the conclusion that the slaves had to be treated like the enemy.” The resistance of the enslaved and the subsequent efforts to stamp out this resistance by violence and terror, constituted themselves in a “second front” that drained Confederate resources that could have been better employed fighting the Yankees. For instance, men were exempted from the draft because they proved diligent “in Police duty among the slaves,” and States and localities retained militias and arms to “maintain order,” even as the demands for manpower for the main Armies grew. But independence without slavery would be worthless in Southern eyes, and thus, costly as it was, this second front was maintained throughout the war.

Confederate Slave Patrols

However, by 1864 the situation had so greatly degenerated, with Southern resources and manpower so exhausted, that some started to consider extreme measures. The acute material crisis the Confederacy was going through convinced President Breckinridge that there was no other option. Consequently, throughout the first half of 1864 Breckinridge expedited several decrees that went against the usual prerogatives of the planters, expanding the power of the Central government, and seemingly settling aside the protection of slavery in favor of a desperate prosecution of the war. Promptly labelled the “Five Monstrous Decrees” by opponents of the administration, the decrees allowed for five distinct measures: 1) the impressment of slave property near the frontlines by the Army, without the consent of owners, with payment to be delivered in Confederate bonds; 2) the placement of heavy taxes on slave property, to be collected at once; 3) restrictions on the cultivation of cotton and other cash crops, requiring every plantation to instead cultivate food for the soldiers and the poor; 4) the impressment of goods such as foodstuffs, again to be paid in bonds; and 5) the abridgement of State militias, with all organized forces being now put under the control of the Central government.

The decrees almost immediately brought about a severe political backlash and the stiff resistance of the planter class. The already contentious impressment of slaves was especially challenged. “For a nation established to give greater security and permanence to slaveholders’ enjoyment of their peculiar property,” explains historian Stephanie McCurry, “impressment came as a terrible blow. It cut against the power masters had always claimed to govern slaves as their personal property,” and “called into question the masters’ sovereignty.” The planter class had always insisted that the only ones who could direct their human chattel were themselves, placing the enslaved beyond the authority of any government. This “alienation from the state” had been a key feature of the system of slavery. Having seceded to prevent the intromission of the United States government with their power, enslavers could not abide by impressment. Indeed, the fact that the government they created to protect slavery was now trying to tamper with it only increased the resistance of the slavocracy.

One worry was that being impressed would foster in the slaves a “spirit of insubordination,” by placing them near the Yankees and thus opening the possibility of them fleeing or aiding the enemy. Certain generals had to recognize the validity of this complain, such as General Joe Johnston who admitted that “We have never been able to keep the impressed negroes with an army near the enemy . . . They desert.” Rather than preserving slavery by helping to keep the foe away, masters argued, impressment would “hasten the very evil” of emancipation, for it would cause “a stampede” to the Yankee lines. “We believe that for every man the government would obtain . . . the enemy would add ten or twenty to his ranks.” However, aside from these practical arguments, slaveowners plainly denied that the government had any right to impress their slaves in the first place.

Heretofore, the government at Richmond sustained planters when they entered in conflict with commanders. When General Magruder tried to forcibly take slaves to work on his defenses during the Peninsula campaign, the War Department rebuked him, telling the general that impressment “should be exercised only in subordination to the ultimate rights of the owners.” Even as the Union started to emancipate slaves and use them as labor and later as soldiers, and despite the Confederacy’s own impressment law, masters refused to entertain widespread impressment, holding this as a kind of emancipation that went against the fundamental principles of slavery. Nonetheless the need for impressment kept growing. Assistant Adjutant General Samuel Melton reported bleakly that “the conscription laws now in force will be utterly inadequate to restore to our armies the numbers they contained last January,” and the only way to make up this disparity was by impressing slaves. And yet, Richmond was still reluctant, for it believed, as Assistant Secretary of War Seddon said, that the slave “owes no service on his own account to the Government [which] knows him only as the property of his master.” As a result, if the master refused to have his enslaved laborers impressed, there was little or nothing the government could do.

Planter resistance negatively impacted the Confederate war effort in several occasions. Even as Wilmington was sieged by Union forces, slaveholders kept demanding the return of their slaves; when Thomas started to siege Atlanta, slaveholders turned a deaf ear to Cheatham’s increasingly desperate pleadings for more slave laborers, instead “refugeeing” them. Such recalcitrance made many, especially those among Breckinridge’s Nationalist Party, believe that masters would have to be forced to comply if there was any hope of winning the war. To “prevent more of our slaves from being appropriated by the enemy,” one suggested to the War Department, “we should ourselves bring their services into requisition.” General Lee, too, declared that impressment was the only way “to use our negroes in this war, if we would maintain ourselves, and prevent them from being used against us.” Joseph A. Campbell declared that “the sacrosanctity of slave property in this war has operated most injuriously to the Confederacy.” As the material disparity between the Union and the Confederacy increased, Breckinridge decided that he had no choice but to approve by decree a far more widespread impressment of slave laborers.

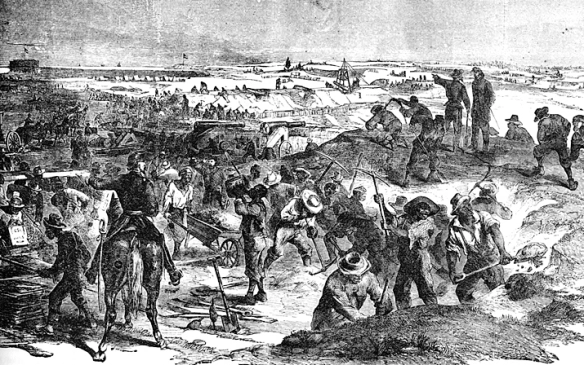

View attachment 844339

Colonel impressing enslaved laborers in South Carolina

Under the auspices of Breckinridge’s decree, the Confederates armies defending Richmond, Atlanta, and Mobile all impressed thousands of slaves over the injured cries of slaveholders. All these laborers were put to work building up trenches and fortifications and were vital in allowing Lee and Cheatham to resist the Federal offensives in the summer of 1864. But despite this, planters denounced Breckinridge’s “tyranny” in extremely bitter terms. Alexander Stephens declared the decrees a “blow at the very ‘vitals of liberty,’” and exclaimed that it would be “Far better that our country should be overrun by the enemy, our cities sacked and burned, and our land laid desolate, than that the people should thus suffer the citadel of their liberties to be entered and taken by professed friends.” As almost always, State governments led and encouraged this resistance, lending “legitimacy and vital support to constituent resistance, casting themselves as the protectors of planter interests against federal tyranny,” analyzes McCurry. While they portrayed themselves as the defenders of states’ rights, McCurry continues, this “was actually an issue of slaveholders’ rights. What looked like a struggle between state and federal power was really a struggle over the right of the central state to abrogate the sovereign rights of slaveholders.”

Immediately, a movement sprang up in Congress trying to declare Breckinridge’s actions unconstitutional. The President, disgusted at this lack of commitment to the cause, chastised legislators for this. Despite all the their protests, Breckinridge enforced the Five Monstrous Decrees widely, justifying them in the public necessity and pointing to the latest successes in repealing the foe. But this meant that when the Union nonetheless succeeded in taking Atlanta and Mobile, the already terrible resistance to Breckinridge’s decrees increased tenfold. “We have lost Constitutional Liberty at home for no gain except the expansion of tyranny and an assurance of destruction!” proclaimed Governor Joseph Brown. “Is it not cruelly hard, that the struggle of eight millions . . . should come to naught—should end in the ruin of us all—in order that the delusions of absolute power, the destructive antipathies, of a single man may be indulged?” questioned the Richmond Examiner. Georgians like Robert Toombs especially criticized how Breckinridge had “unleashed a vandal horde” in the form of Wheeler’s cavalry and other unruly units, “abetting and promoting acts of lawless inhumanity, all without constitutional justification, and without tangible results.” From all over the Confederacy planters echoed the cry that Breckinridge had “emancipated our negroes and given them to the United States forces,” for no reason at all, “dealing a fatal blow to the cause of the country and the interests of the planters.”

Breckinridge did not need a thousand voices calling the defeats a catastrophe, for no one was more aware of the magnitude of the disaster than him. In his heart of hearts, it seemed like Breckinridge never truly believed that the Confederacy could outright defeat the Union, and while he felt he had to try with all his might out of both a sense of honor and love of principle, this doubt had never left him. Breckinridge envisioned his emergency decrees as a last resort measure, such that if even they failed, there was no way the Confederacy could win. Breckinridge thus was convinced that continuing the war was futile, and that further resistance could only result in more suffering and bloodshed with no result but complete submission. The summer of 1863, with the defeats at Liberty, Lexington, and Union Mills, had already so badly shaken his faith that he produced a blind memorandum expressing these points. If “the ability for carrying on this war shall have been destroyed,” and “the government shall become convinced that our condition is full of peril and our cause hopeless,” wrote Breckinridge, “it shall be our responsibility to take whatever further measures shall seem necessary to rescue the people of the Confederacy from the danger of devastation and bloodshed.”

After his Cabinet signed the memorandum, Breckinridge filed it away, hiding this promise to surrender. It is said he always carried it on his breast pocket as a reminder of his responsibility to the Southern people. Breckinridge produced the memorandum when all his Cabinet secretaries arrived for an emergency meeting following the fall of Mobile. Without losing time, Breckinridge read it, all the men falling into grim, anxious silence. “I made a promise to myself, to not carry on this war if it means leading our people to destruction,” Breckinridge stated as soon as he finished the message, a sepulchral silence still reigning in the room. “I will not hold any of you to this promise,” Breckinridge continued after a moment, explaining that he made them sign the memorandum “to satisfy you gentlemen that this is a resolution I made in a moment of sober thought,” and not one “borne out of the present panic and despair.” “Our first duty is to our people,” Breckinridge finished, “we, gentlemen, hold the responsibility of action. How shall we act?”

Anti-Breckinridge propaganda showing the consequences of impressment

Several people have believed that Breckinridge’s decision was a sudden turn, and that despite what he claimed it was indeed “borne out of the present panic and despair.” Finding it hard to believe that the same President who had been taking such extreme measures to continue the war would now act so decisively to end it, many have found it impossible to understand Breckinridge’s actions and motives. In truth, this reveals a misunderstanding of the Confederate peace movement, conflating the unconditional Unionists who advocated for a complete Union victory with a growing segment of the population that was approaching the conclusion that surrendering now would accomplish less suffering and destruction, and could maybe result in a negotiated peace that might save slavery and White supremacy, whereas fighting to the bitter end would only result in complete perdition. As long as there seemed to a possibility of victory, Breckinridge had been willing to fight. But now that he was convinced that defeat was inevitable, Breckinridge, just like many other peace advocates, supported surrender not as a way to give up the Confederate cause and principles – but as a way to salvage what remained and prevent their destruction.

During that fateful meeting, no one said anything for several tense minutes, before Jefferson Davis stood up and started to argue, with increasing anxiety, that it was not yet the time to surrender. “We are fighting for existence; and by fighting alone can independence be gained,” Davis asserted, for the “tyrant Lincoln” would never accept any real proposition of peace, only “unconditional submission.” They must not accept the “disgrace of surrender,” Davis pleaded, but should continue the fight. After Davis finished his impassioned plea, no one else spoke, and then Breckinridge dismissed the Cabinet, ordering every secretary to write their thoughts for a second meeting to take place in three days. The exception was Davis, who was asked to remain in the room, and with whom the President talked for a long while. The substance of their conversation has been lost, but after it Breckinridge prohibited all secretaries from talking of that Cabinet reunion, and dismissed Seddon as Assistant Secretary of War, naming John A. Campbell to the post. The next day Breckinridge held the first reunion of his “Petit Cabinet,” as the meetings he held with Davis, Campbell, Secretary of the Navy Mallory, and General Lee, came to be known.

We only know of the events that took place in the “Petit Cabinet” thanks to Mallory’s and Campbell’s detailed diaries. Breckinridge had to tell Campbell and Lee of his resolution, both men reacting with similar shock. Maybe Lee ought to have suspected something, for after the fall of Atlanta, Breckinridge had asked him to produce a report of his opinions on the war effort. “The military condition of the country,” Lee admitted, “is full of peril. . . . Without some increase of our strength, I cannot see how we are to escape the natural military consequences of the enemy's numerical superiority.” However, even though Lee too was having doubts of whether his Army could win at the end, he argued that “While the military situation is not favorable, it is not worse than the superior numbers and resources of the enemy justified us in expecting.” Everything “depended and still depends upon the disposition and feelings of the people.” If Breckinridge could convince them to continue the fight, there was still hope for victory. The combined weight of both Lee and Davis swayed Breckinridge, and after long moments of reflection, the President instead offered a secondary plan. This one was, in its own way, just as shocking as his earlier proposal.

Breckinridge’s plan contemplated not only the widespread impressment of Black slaves as laborers, but their drafting into the Confederate Army as soldiers. This was a possibility Breckinridge had long contemplated, ever since General Cleburne proposed it following the defeat at Liberty, but because he acknowledged it as “odious” to the Southern people, Breckinridge hadn’t proposed it openly. But now he was convinced that unless they recruited the enslaved, there was no way to triumph. Both Davis and Lee mulled over the proposal for a long time. Finally, Davis spoke, saying that while he opposed Black enlistment, if “the alternative ever be presented of subjugation or the employment of the slave as a soldier, there seems no reason to doubt what should then be our decision.” Davis had offered his reluctant support, but Lee remained silent. “I am afraid, General, that if we do not recruit the Negro, we shall have to give up Richmond,” prodded Breckinridge This shook Lee out of his stupor, and with tears in his eyes the General exclaimed that “Richmond must not be given up; it shall not be given up!” After regaining his composure, Lee conceded that “We must decide whether the negroes shall fight for us, or against us.”

Impressed slave laborers working on Confederate defenses

Breckinridge had placed the possibility of surrender before the other Confederate leaders, but they managed to convince him that the time had not come yet, and they all agreed that Black enlistment, distasteful as it might be to their sensibilities, was still an available choice. It’s likely that Davis and Lee would have come to consider that choice eventually, but without Breckinridge they probably would have accepted it only when it was too late. This reluctance was informed by the recognition that those Black men who had been drafted into the Confederate Army would necessarily have to be freed. As Davis admitted, the Confederacy could only inspire the “loyalty and zeal” necessary in a soldier if it promised to “liberate the negro on his discharge after service faithfully rendered.” Lee as well would later declare that Black slaves who were recruited “should be freed. It would be neither just nor wise . . . to require them to serve as slaves.” Due to this, many criticized the very idea of drafting the enslaved as a kind of “Confederate emancipation” that would destroy slavery before the Yankees could do it.

However, and similarly to Breckinridge’s argument in favor of peace, the argument in favor of Black enlistment was based on the idea that it was actually the only way to save slavery – with Black soldiers, the Confederacy may yet win and preserve some of the institution, while the alternative was to see every single slave freed. Cleburne had made that same point in his proposal, claiming that a Federal victory would result in “equality and amalgamation” with every single slave, whereas the Confederacy, if victorious with the use of Black soldiers, could still “mould the relations, for all time to come, between the white and colored races” through “wise legislation,” maintaining the majority of Black people in slavery and heavily curtaining the liberty of the freed, for “writing a man ‘free’ does not make him so.” After the proposal was officially announced, those who supported it quickly came to its defense using the same arguments, such as the Richmond Sentinel, which stated that even if Black recruitment left Southerners “stripped of property,” they would remain the “master of the government” a position “infinitely better” than being defeated by the Union, which would strip them of property anyway and leave Lincoln in charge of race relations in the post-slavery South.

Despite these arguments, the majority of Southerners could not bear the idea of freeing and arming the people they enslaved. R.M.T. Hunter called the proposal the “most pernicious idea that had been suggested since the war began;” General Johnston denounced it as a “monstrous proposition;” and Howell Cobb declared that “the moment you resort to negro soldiers your white soldiers will be lost to you. . . . The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” Indeed, in American society and especially Southern society, the ideas of citizenship and masculinity were intimately linked with honor and military service. The fact that the enslaved could not be soldiers was proof of their inferior status. If now the rebels themselves drafted them as soldiers, it would be tantamount to recognizing them as equals to the White soldiers. The Confederate Army would be “degraded, ruined, and disgraced,” if it allowed such a thing, thundered Robert Toombs, while a Mississippi congressman said that “victory itself would be robbed of its glory if shared with slaves,” while “the poor soldier” would be “reduced to the level of a nigger.”

These “slaveholders on principle,” admitted candidly that they “preferred defeat and destruction to any infringement on their prerogatives.” “We want no Confederate Government without our institutions,” the Charleston Mercury shouted, while a North Carolina newspaper called the proposal “abolition doctrine . . . the very doctrine which the war was commenced to put down.” A Lynchburg newspaper admitted that “the South went to war to defeat the designs of abolitionists,” and thus they could not “turn abolitionists ourselves . . . we infinitely prefer that Lincoln shall be the instrument of our disaster and degradation, than that we ourselves should strike the cowardly and suicidal blow.” Even Holden’s North Carolina Standard believed that if Southerners armed slaves it would be following “the example of heathen Sparta or insane France in 1792 . . . What would such independence as Hayti be worth to us?” Breckinridge’s plan, in truth, did not contemplate in any way widespread emancipation. Secretary of State Benjamin was quick to clarify that Black soldiers would only be freed after “an intermediate state of serfage or peonage.” But the administration insisted that freedom had to be granted to a Black recruit because it was already “offered to him in the neighboring hostile camp,” and, further, that if the rebels did not make soldiers out of their slaves now, they would soon be freed and made into soldiers by the enemy.

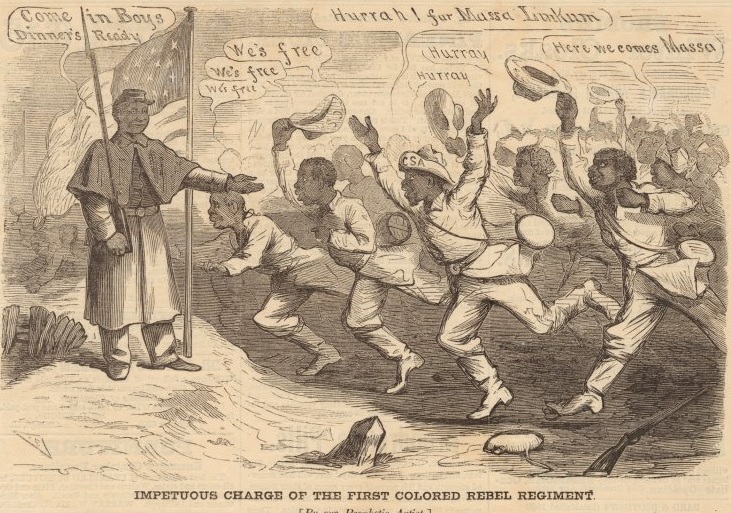

Union cartoon mocking the idea of the enslaved fighting for the rebels

Lee’s influence proved decisive, for his support of Black recruitment managed to carry along most of the officers of the Army of Northern Virginia and even extracted resolutions in favor from several regiments, such as the 56th Virginia, which claimed that while “slavery is the normal condition of the negro . . . as indispensable to [his] prosperity and happiness . . . as is liberty to the whites . . . if the public exigencies require that any number of our male slaves be enlisted in the military service,” they would accept. The Richmond Examiner observed how “the country will not deny to General Lee anything he may ask for.” This allowed Breckinridge’s allies in Congress to obtain enough support to work on legislation to actually execute the plan. But the result was not what Breckinridge had hoped for. Even though the lawmakers, Senator Allen Caperton said, recognized that it was “better to part with a portion of our property than the whole of it and our liberty besides,” they refused to heed Breckinridge’s and Lee’s stipulation that the Black soldiers should be freed. Worse, the final bill by Mississippi’s Ethelbert Barksdale did not empower the government to draft any slaves; instead, the President would only be able to ask masters to willingly lend slaves. Barksdale outright celebrated how the bill would not allow Breckinridge the “exercise of unauthorized power to interfere with the relation of the slave to his owner as property, but by leaving this question, where it properly belongs—to the owners of slaves.”

Despite the weakness of the law, the organization of Black soldiers went forward. In the meantime, the military situation had further deteriorated, with movements in the Shenandoah Valley and Sherman starting a campaign in Georgia, which further seemed to prove the necessity of these actions. Even as newspapers claimed that the enslaved had been gripped by a “military fever,” in truth the government was unable to raise more than a few dozen recruits. This was partly because of the resistance of the planters, who fought back against this draft with even more vigor than they had fought against impressment. Catherine Edmonston claimed confidently that planters would not “allow a degraded race to be placed at one stroke on a level with them,” while Senator William A. Graham openly called on planters to refuse "at all hazards" the recruitment of their slaves. Their opposition was such that, according to the Richmond Enquirer, “certain members of Congress . . . openly declared their preferences for reconstruction, with Federal guaranty of slavery, to the emancipation of slaves as a means of securing the independence of the Confederate States.”

But the failure was also owed to the resistance of the enslaved themselves. When Sherman later marched through Georgia, he found Black people claiming that they preferred to flee to Federal lines than accept the Confederate offer, for they understood that “They’d never put muskets in the slaves’ hands if they were not afeared that their cause was gone up.” Mary Boykin Chesnut, who had written that her slaves were “keen to go in the army” for freedom at the start of the war, now reported that “they say coolly they don’t want freedom if they have to fight for it,” because “they are pretty sure of having it anyway” once the Union won. Moreover, the Union, quite simply, offered a better bargain, because it also freed the families of Black soldiers and seemed to promise greater changes through the Bureaus and Reconstruction. The experience of the few Black recruits who had pressed into service must have also been disheartening, for they were kept in military prisons, drilled without arms, and had to endure the scorn of White civilians. General Ewell, assigning by Lee to raise the new regiments, wrote that “some of the blk soldiers were whipped they were hooted at and treated generally in a way to nullify the law.”

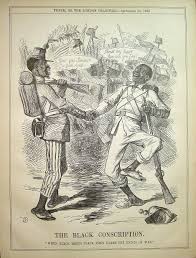

Punch Magazine commented on the enlistment of Black soldiers as "Rouge et Noir: Johnny Breck's last card."

The dismal results convinced Breckinridge that Congress’ law would not do. In early October, Breckinridge expedited a decree claiming that he did not, in fact, need the authorization of Congress to raise and arm Black regiments. Under the impressment law, the President argued, he was empowered to take the enslaved permanently, just as he could take foodstuffs or a wagon. The enslaved person would then become the property of the government, which could employ him as a soldier and then emancipate him if it wished. That this was basically the same reasoning as that of General Butler when he inaugurated the “contraband” policy was not lost on the rebels. Immediate wounded cries of unconstitutional tyranny arose, but Breckinridge would not budge, quickly ordering for slaves to be impressed and organized into Army regiments. When Congress passed a resolution declaring Breckinridge’s actions illegal, the President refused to comply, saying that only a Supreme Court, which had never been organized, could declare his acts unconstitutional. The Congress promptly tried to organize the Court, but Breckinridge vetoed the bill, and when it passed over his veto, he refused to put forward any nomination.

While Breckinridge locked horns with Congress, disaster struck the Confederacy. On October 7th, units of the Army of the Susquehanna prodded Lee’s lines at Petersburg. In reality, this was but a meaningless skirmish, but Lee still went to oversee it, afraid that this was in fact a new offensive. There, a sharpshooter was able to shoot Lee, hitting him on the chest. Though he was rushed to medical care, the foremost general of the Confederacy still died mere hours later. The outpour of despair and hopelessness that ensued can hardly be described. As historian Gary W. Gallagher has said, Confederate citizens “increasingly relied on their armies rather than on their central government to boost morale,” such that there was “a belief that independence was possible as long as the Army of Northern Virginia and its celebrated chief remained in the field.” Now, without Lee, many Confederates felt that victory was truly impossible. “God has taken him from us that we may lean more upon Him,” Edmondston consoled herself, but “I fear He has abandoned us too!” Breckinridge took Lee’s death very hard, for not only had he come to enjoy a genuinely warm friendship with the general, but the President also relied on Lee to keep the foe at bay and provide essential support to his policies. Without Lee, Breckinridge predicted, morale would completely shatter, and his policies would fall apart – and in this, Breckinridge was completely right.

The day after Lee’s death, Breckinridge called for another meeting of the Petit Cabinet, now with Generals Jackson and Longstreet replacing Lee. Both generals learned just then of Breckinridge’s earlier proposal for peace, which the President repeated now. The attempt to recruit Black soldiers had been a pathetic failure; the resources of the Confederacy were exhausted; and without Lee, there was scarce hope of holding back Grant. Even if they could, Sherman was already moving through Georgia, and would soon be on their rear. Their last hope, Breckinridge said, was abandoning Richmond, and trying to link up with Cleburne. If this failed, they would have no option but surrender. Jackson, who was usually surprisingly timid, found his voice to protest that the soldiers “would not disappoint the memory of General Lee,” and that, moreover, “God has not abandoned us.” But a tired Breckinridge just snapped back “General Jackson, do you mean to hold all fifty thousand Federals in Petersburg by yourself? If you did, and General Longstreet held another fifty thousand on his own, we may yet achieve our independence.” Jackson then fell into grim silence, saying nothing as Breckinridge appointed Longstreet to lead the Army of Northern Virginia, ordering him to prepare to evacuate Richmond.

The last moments of Robert E. Lee

It seemed that at last the end of the Confederacy was at hand. Without Lee, most Confederates believed they could not defeat the Federals and their overwhelming numbers, and most had further become convinced that their own President wished to betray them. Breckinridge, many Southerners said, was doing “everything in his power to destroy us before the Yankees do it.” His moves against slavery had only weakened the institution; his decrees had merely increased the privations the people suffered; his military decisions had led them to disaster; and now, he seemed ready to yield Richmond to the enemy and then completely surrender to him. It little mattered that Breckinridge was, in truth, envisioning a conditional surrender as the only way to preserve some of the South’s rights and spare the people of needless suffering. For the rebel aristocracy, Breckinridge “had gone over to the enemy.” Consequently, no one came to the rescue when on October 10th, Confederate soldiers stormed the Executive Mansion and arrested Breckinridge on charges of treason, under the orders of the “Provisional Government of the Confederate States,” a Junta integrated by Toombs, Vice-president Stephens, and Generals Jackson, Beauregard, and Johnston. The Breckinridge government was thus overthrown, assuring in a last self-destructive irony that the war would go on to the bitter end, and that the Confederacy would be completely destroyed.

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: