Bring the good old bugle, boys

We’ll sing another song

Sing it with a spirit that will

Start the world along

Sing it as we used to sing it

Fifty thousand strong

While we were marching through Georgia

Chorus:

“Hurrah! Hurrah! we bring the jubilee!

Hurrah! Hurrah! the flag that makes you free!”

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea

While we were marching through Georgia

“Sherman’s dashing Yankee boys

Will never reach the coast!”

So the saucy rebels said

And ’twas a handsome boast

Had they not forgot, alas

To reckon with the host

While we were marching through Georgia

So we made a thoroughfare

For Freedom and her train

Sixty miles in latitude

Three hundred to the main

Treason fled before us

For resistance was in vain

While we were marching through Georgia

-Marching Through Georgia

The falls of Atlanta and Mobile are remembered as the great turning point of the American Civil War mostly because of their political consequences. They not only revived Lincoln’s re-election campaign, but also started the chain of events that would lead to the coup against Breckinridge. But their military repercussions were also significant, for these victories exposed the soft underbelly of the Confederacy. “Pierce the shell of the C.S.A. and it’s all hollow inside,” declared Sherman triumphantly as his troops marched unopposed and snuffed the last remnants of resistance in Alabama. While there remained thousands of die-hard rebels in the Southern Armies, the Junta was completely unable to furnish them with reinforcements or supplies. The iron was hot, and it was the time to strike and bring the House of Dixie down once and for all. To achieve “honorable peace, won in the full light of day, at the cannon’s mouth and the bayonet’s point, with our grand old flag flying over us we negotiate it, instead of cowardly peace purchased at the price of national dishonor,” like a Yankee soldier declared as offensives into the Valley, Georgia, and Charleston started in October of 1864.

The Valley, despite its sorry record of Union defeats, now seemed like a very attainable objective. Grant’s continuous pressure on Lee had forced the rebel commander to strip most of the forces there to defend Richmond, and after the coup the Confederate forces in the Valley were even further weakened. This was partly due to the unfortunate fact that several Kentucky regiments had been there, and virtually all deserted following Breckinridge’s overthrow. Consequently, Jubal Early only had some 10,000 soldiers to face the 35,000 men-strong Army of the Shenandoah that had been gathered around General David Hunter. Though he had met success in Kansas and Missouri, where he was a pioneer of Black recruitment, Hunter had performed poorly at the Battle of Bull Run when transferred to the east. The sacking of the incompetent Siegel afforded him a renewed opportunity to obtain military glory by finally achieving a decisive victory in the Valley.

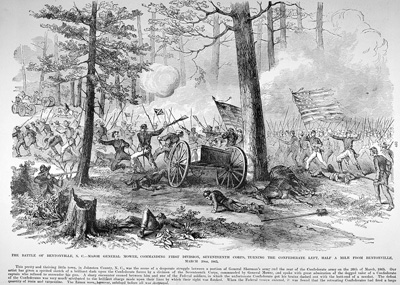

The start of the campaign augured well for Hunter’s ambitions. In early September, Union troops overwhelmed a smaller rebel force, and then marched from Staunton to Lexington. In the way, they were harassed by Confederate partisans, which swarmed Hunter’s supply wagons. According to one Federal, these men were “’honest farmers’ who have taken the oath of allegiance a few times,” only to turn and then “proceed to lay in wait for some poor devil of a blue jacket . . . they take ‘em and kill them on the spot . . . Now and then an ambulance or two, full of sick men, is taken without loss.” These partisans had been weakened both by the desertion of their former leader, Mosby, who surrendered himself to Grant after the coup, and by the harsh war methods the Union had adopted in response. Neither forgetting nor forgiving Early’s raid, Grant had instructed Hunter to “follow Early to the death” and “eat out Virginia clear and clean . . . so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them.”

The angry Union soldiers were only too glad to comply. “Looting escalated to terrorizing of citizens; destruction of military property escalated to the burning of towns that sheltered guerrillas; military raids escalated to punitive expeditions that hanged each man found under arms,” writes historian James McPherson. The experience was almost apocalyptic to the terrified civilians. “Fires of barns, stockyards, etc. soon burst forth and by eleven, from high elevation, fifty could be seen blazing forth,” wrote a Berryville woman. “One might have imagined the shades of Hades had suddenly descended. The shouts, ribald jokes, awful oaths, demoniacal laughter of the fiends added to the horrors of the day.” “Many of the women look sad and do much weeping over the destruction that is going,” wrote a Yankee. However, “we feel that the South brought on the war and the State of Virginia shoulder pay

dear for her part.”

Because the food situation was already so critical, the Junta could not allow the Breadbasket of Virginia to be so thoroughly reduced to ashes. Men were quickly rushed into the Valley, including V.M.I. cadets and other children, perhaps in the hopes of repeating the deeds of heroism of the previous campaign. But even these desperate impressments only bolstered Early’s forces to 17,000 soldiers. No matter, Early was decided to follow his mentor Jackson’s strategy by launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek. Even though a Quaker woman named Rebecca Wright had alerted Hunter of Early’s presence, Hunter still was careless in positioning his Army, which meant that two divisions were easily rolled back by Early’s attack. Early then failed to capitalize in his victory, most soldiers instead deciding to eat the abandoned provisions, but this was apparently fine at first for the befuddled Hunter had no plans for a counterattack. Unfortunately for Early, another Federal did – Philip Kearny.

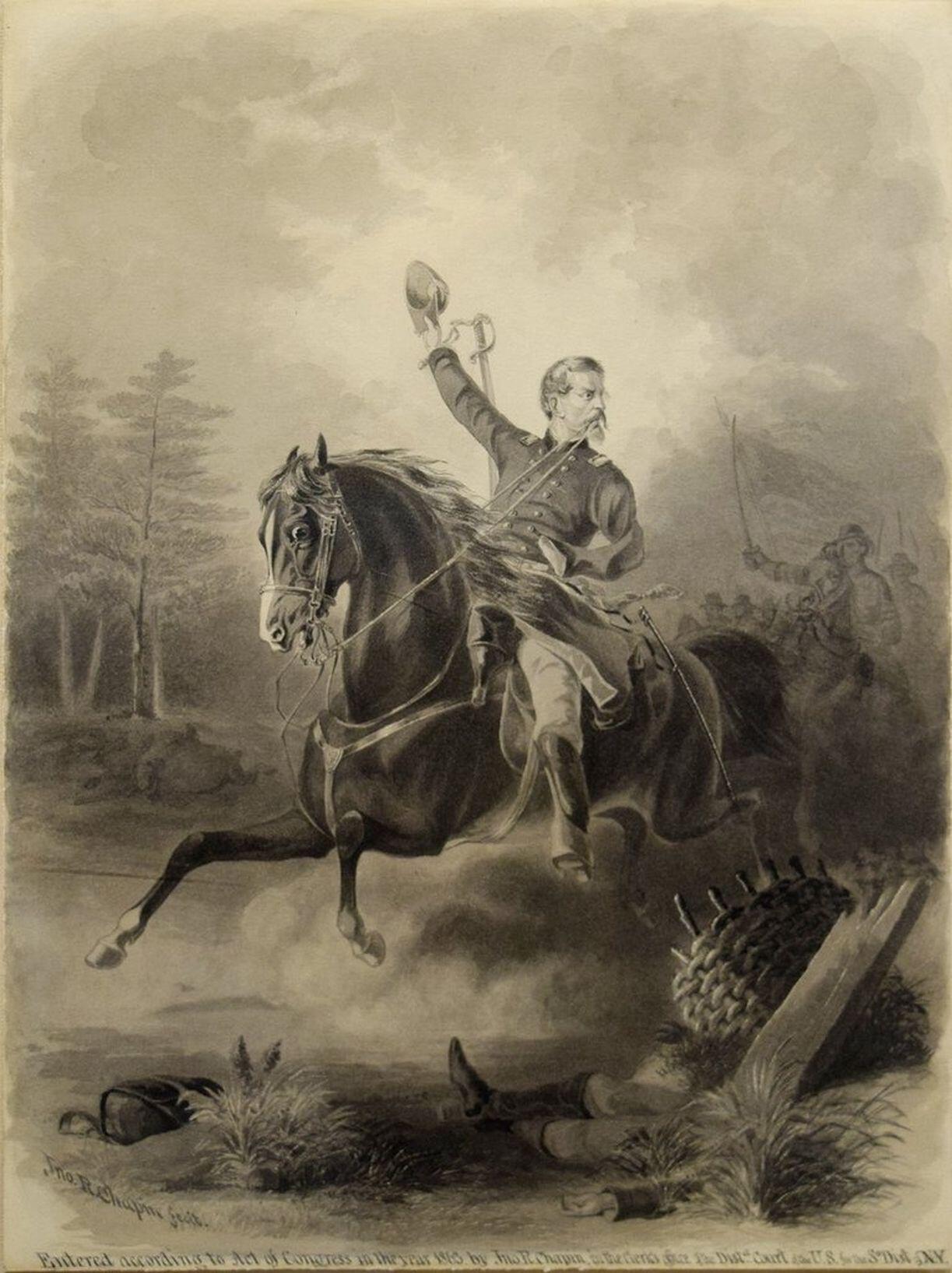

Born within a wealthy family of Irish ascendancy, Kearny had always wished to become a military man, serving in a Dragoons regiment which had Jefferson Davis as its accountant. Afterwards, he was sent to France and Algeria, where he learned to ride into battle in the style of the

Chasseurs d’Afrique: with a sword in his right hand and the reigns between his teeth. This served him well, for Kearny would then lose an arm in the Mexican War. Undeterred, Kearny continued to pursue military glory, winning the French Legion of Honor for bravery at the Battle of Solferino. Yet, after the start of the Civil War Kearny struggled to regain his commission due to his disability. This delayed Kearny at first, but after he secured command of a division, he quickly showed his worth, being wounded while boldly riding at the head of his men at the Battle of North Anna. As soon as he healed enough, Kearny jumped back into action, being assigned to the Shenandoah Valley. That day, while Hunter dithered, Kearny burst forth shouting “I’m a one-armed Jersey son of a gun, follow me!” This started a daring counterattack that sent the complacent rebels whirling back.

Early then attempted to take a stand at Fisher’s Hill, a narrow position dubbed the “Gibraltar of the Valley.” But his weakened force was unable to resist when Hunter, who had by then gathered his bearings, went on the attack. Leading the assault was a jubilant Kearny, who declared to his cheering troops “Don’t worry, men, they’ll all be firing at me!” At the end, Early’s force suffered a decisive defeat, losing thousands of men at the price of minimal Federal casualties. Rebels tried to explain the defeat by blaming unruly soldiers who broke ranks to pillage the Yankee camps instead of pressing their advantage after the initial surprise attack. “Our army is little better than a band of thieves and marauders!” exclaimed a Virginia infantryman. Whatever the cause, the consequences were that large extensions of the Valley were finally under a firm Union grasp, while most of Early’s force was moved to Petersburg, in effect an acknowledgement of defeat.

Hunter and the newly ascended Kearny continued “the Burning” of the Shenandoah during the next few weeks. By late October, a colonel wrote that the Valley “has been left in such a condition as to barely leave subsistence for the inhabitants. The property destroyed, viz, grain, forage, flouring mills, tanneries, blast furnaces, &c., and stock driven off, has inflicted a severe blow on the enemy.” “Our forces are burning everything they pass in the Valley,” wrote a bluejacket. “I suppose most of the houses occupied by southern sympathizers will be burned up.” The destruction, however, was not indiscriminate. Instead, it was of “targeted severity: Union soldiers targeted public and quasi-public property more than private property, plantations more than farms, and the disloyal rather than loyal Unionists.” Except for those found actively helping rebel guerrillas, most citizens went unmolested despite the harsh proclamations that the Valley was to become a “barren waste” and “uninhabitable desert.”

The harshest measures were reserved for the guerrillas and the populations that extended their “assistance and sympathy” to them, allowing the partisans to murder scores of Yankees. To punish them, Hunter ordered to “consume and destroy all forage and subsistence, burn all barns and mills and their contents, and drive off all stock in the region.” The Union also unflinchingly retaliated against guerrilla activities. General Powell, for example, executed two rebel “bushwhackers” in retaliation for the murder of a Union soldier. Powell hanged the corpses publicly and ordered the complete destruction of their homes, finally threatening that “if two to one is not sufficient I will increase it to twenty-two to one.” Through such tactics the Union Army “burned out the hornets,” that is, captured and hanged hundreds of guerrillas and thus “purified” the Valley, both complicating the logistics of the Army of Northern Virginia and shattering the confidence of many Confederates in the Junta.

Indeed, maybe the material losses of the Valley Campaign were surpassed by the devastating effect it had on the morale of Southerners. Long a scene of painful Union defeats, and especially the place where Stonewall Jackson had achieved some of his greatest triumphs, the Valley now laid “desolated and subjugated” at the feet of the Union, the people “forsaken by those who promised victory.” For the Federals, their success was long-awaited redemption after suffering so many and so embarrassing losses at first. “The retreats and defeats in the Shenandoah valley . . . have at last been redeemed by a decisive victory,” the

Christian Recorder celebrated. The achievement further solidified confidence in Lincoln, demonstrated the feebleness of the new Southern regime, and weakened the opponents of the Administration even more. Republican elation was best summarized by Thomas B. Read’s poem, which declared that soon the Union Army would advance to the rest of the South, like “the trail of a comet, sweeping faster and faster, foreboding to traitors the doom of disaster.”

Phillip Kearny riding into battle

Indeed, disaster was nigh, at least in the West where two ambitious Confederate counteroffensives ended up in catastrophe. The first was the final attempt of General Forrest to invade Tennessee and Kentucky. Following Sherman’s Alabama campaign, the forces under Forrest had been greatly weakened, but General McPherson had been unable to catch and destroy him. Pushed into Tennessee, Forrest was now operating in an irregular basis, spurning Richmond’s orders to head to Georgia. When he received news of the coup, Forrest demanded operational independence in exchange for loyalty, plus reinforcements of men and material. But General Johnston, now the official commander of the Confederate West, ordered Forrest to come to Georgia and withheld some scant supplies in order to force Forrest’s hand. He only managed to anger him. Forrest decided to continue to operate on his own, sending a defiant telegram to Johnston where he asserted that “you may as well not issue any more orders to me, for I will not obey them, and I will hold you personally responsible for any indignities you may try to inflict upon me . . . if you try to interfere with me it will be at the peril of your life.”

Forrest, nonetheless, still avowed himself a Confederate and thought that surrender would mean hanging from a sour apple tree. Consequently, he resolved to continue to operate on his own, settling his sights in Tennessee. There, he believed he could seize resources he desperately needed, particularly horses. To try and distract McPherson, Forrest had divided his force, raising false alarms of imminent raids. But many of the raiders were easy prey to anti-guerrilla Union sentinels. Moreover, Forrest’s own attempts to live off the land were unsuccessful, the fortified home farms he found in middle Tennessee were not easy pickings anymore. Consequently, Forrest decided to head to the supply base at Johnsonville, a recently constructed fort named after Andrew Johnson, ironically for most of its soldiers were inexperienced Black recruits while the real Johnson was showing his bitter prejudices more and more.

Forrest’s racist beliefs led him to underestimate the Black Union soldiers once again. Though they were outnumbered, they resisted the rebel charges. Both sides chanted “Fort Pillow!” as the battle developed, one side as a taunt, the other as a call for revenge. Amidst burning liquor and supplies, the soldiers struggled mightily for several hours, until Union river ironclads arrived and opened fire on the Confederates. Forrest saw no other option but to escape, having lost just 300 men but failing in his main objective of seizing the fort’s supplies. The cheers of the Black troops, who shouted “Fort Pillow, avenged!” as he retreated added insult to injury. The escape proved trying for the grey soldiers, many falling by the wayside, victims of exhaustion, hunger, and disease. Moreover, for the first time Forrest learned what it was like to be harassed, for especially daring Home Farm regiments and Unionists tried to slow down his march and nip at the stragglers. But Forrest was not ready to give up yet. He headed for Fort Thomas in Murfreesboro, an even bigger supply base than Johnsonville.

In what’s been called “Forrest’s Last Hurrah,” the rebel cavalryman managed to lure the Fort Thomas garrison out, by sabotaging the railroad just outside of the range of the fort’s guns, and then hit it in the rear with the hidden other half of his force. But the timely arrival of Union reinforcements plus McPherson’s Corps forced Forrest to flee again, having once more failed to seize any supplies. As he chaotically retreated, Forrest called in desperation to “Rally, men, for God’s sake, rally!” But few did, and a color bearer even broke ranks and tried to desert. Forrest shot him in the spot, and then seized the colors himself. But it was for naught, as many men still deserted and surrendered to the pursuing Yankees. The Battle of Murfreesboro thus effectively ended Forrest’s Corps as a fighting force. Never again would the once so feared raider pose a credible threat to either Union supplies or garrisons, and for the following months Forrest’s force worked as merely an irregular guerrilla, probably harming rebel civilians significantly more than the Union forces.

A similar fate befell General Sterling Price in Missouri. Beaten back by the forces under General Schofield in 1863, Price had nevertheless refused to give up his dream of “liberating” Missouri from Yankee oppression. The fact that Radical Republicanism was gathering strength to try and give the State a new constitution only strengthened Price’s resolve. Surely, “the people must realize that such a usurpation” would leave them “bereft of all the rights and liberty proper to free men.” Price, it can be seen, clung to the idea that thousands of guerrillas were ready to join his banner. A closer analysis of the situation would prove that these expectations were overly sanguine. Most guerrillas were unwilling to directly face the Union and fought not out of patriotic allegiance, but a simple desire to indulge their worst instincts. Moreover, Price himself, though still widely celebrated by Confederates, counted with significantly less resources and suffered from very poor health. He now weighed over 300 pounds and had to ride in an ambulance all the time, a young girl writing in disappointment that instead of the warrior she expected he was “a fine fleshy looking old gentleman of about 65 years of age.”

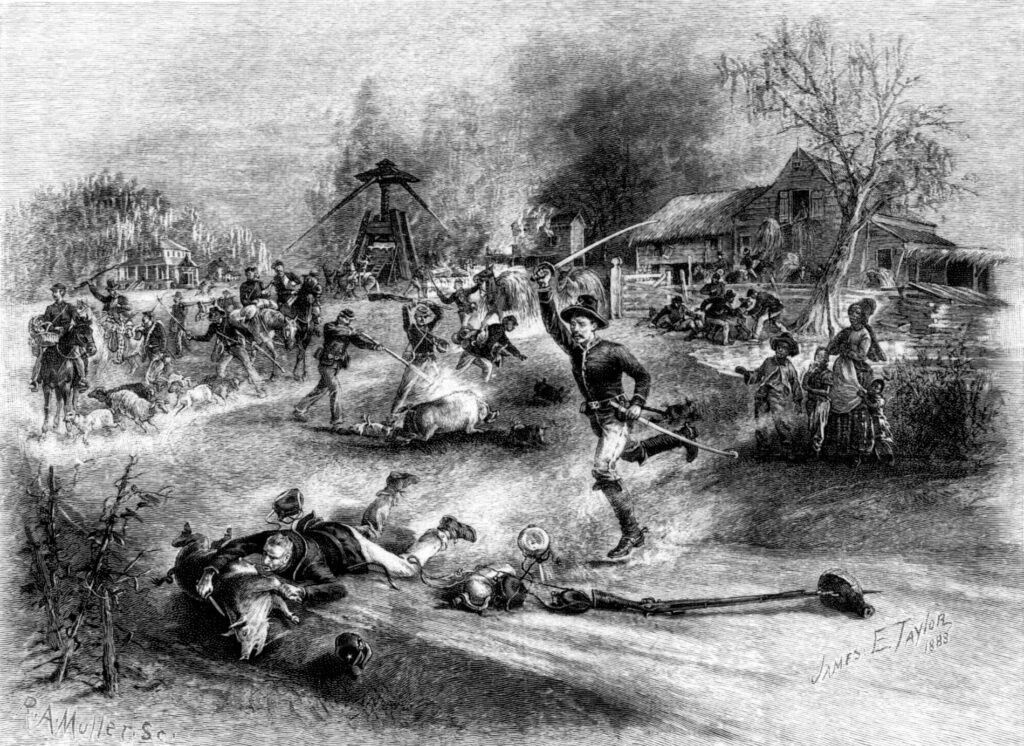

Price's Missouri Expedition

“Price’s Raid into Missouri was a desperate military campaign if ever there was one,” Mark E. Neely writes frankly, an “eloquent testimony to the dire straits of the Confederacy in 1864 even previous to the coup.” The raid was so ill-prepared that of the 12,000 men Price had gathered, Neely writes, “over 20 percent of them—perhaps as many as 40 percent—were unarmed!” Soon enough this “Liberating” Army instead turned to “scouting” the countryside for food – which, predictably, quickly degenerated into marauding. The Confederate claimant to the Governorship, Thomas C. Reynolds, described in outrage how “the clothes of the poor man’s infant were as attractive spoil as the merchant’s silk . . . and jeweled rings were forced from the fingers of delicate maidens whose brothers were fighting in Georgia.” As ordered by Price, the guerrillas under Quantrill and Anderson also stepped up their campaigns of terror, victimizing and forcibly impressing civilians, some of them mere boys, to bolster their ranks.

Price’s enemy would be General Rosecrans, now the commander over Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas. Something of a folk hero due to his exploits at the Battle of Liberty and the Texas campaign, he was prepared to meet the foe. According to Rosecrans, “traitors of every hue and stripe, had warmed into life at the approach of the great invasion. Women’s fingers were busy making clothes for rebel soldiers out of goods plundered by the guerrillas; women’s tongues were busy telling union neighbors ‘their time was now coming.’” Rosecrans accused these “gangs of rebels” of committing “the most cold-blooded and diabolical murders,” such as the atrocious massacre of Union soldiers guarding a railroad station. There, “Bloody Bill” killed over fifty soldiers, and some were “scalped, and [they] put others across the track and ran the engine over them.” At first Rosecrans tried to maintain the moral high ground by refusing to repay the rebels with the same coin. However, following the coup against the Breckinridge government, Rosecrans issued a declaration telling the raiders that, unless they surrendered, they would be treated as guerrillas, for there no longer existed “any chain of command or civilian authority over them.”

Rosecrans was right, for Price had, similarly to Forrest, refused to head the Junta. In fact, Price received news of the coup weeks after it happened, together with orders to leave Missouri and somehow go to Georgia instead. Price simply ignored them. But his invasion was already going awry. Union anti-guerrilla tactics, devastating as they were, had significantly weakened the guerrillas, and they found little support among many populations that were now relying in redistributed land and Bureau provisions. Large manhunts resulted in the death of Anderson in battle, and then the capture and execution of Quantrill. Scores more were hanged at sight, a Major Rainsford justifying the summary treatment of these “bands without principle or feeling of nationality, whose record is stained with crimes at which humanity shudders.” The only large action Price engaged in was an abortive attack at Pilot Knob, which was followed by a crushing defeat at Westport in November. Now fearing for his life, Price managed to barely escape, now with fewer than 4,000 men. Price’s raid had only resulted in the end of organized Confederate resistance in Missouri, for the guerrillas had been thoroughly wrecked, the campaign of terror that had covered Missouri and Kansas with blood for years ending at last.

The Federal response in Missouri demonstrated that for many Union men the Junta was no longer to be regarded as a legitimate government. The Lincoln administration had been somewhat equivocal in its official position to the Confederacy, the US government always insisting it was a mere insurrection but at the same time affording a measure of recognition to the Confederate government as a belligerent. Consequently, its soldiers were treated as POWs, and official communication and arrangements between generals or politicians were not only common but expected. However, following the coup the Northern military and public grew to see the Junta as an inherently illegitimate, lawless body. Certainly, how far they were willing to carry this interpretation varied, and those units that were still capable of fighting such as the Army of Northern Virginia were for the most part still afforded respect. But overall, the impression formed among Northerners that there was no true Southern government anymore, and that they were just facing a collection of unorganized terrorists.

Foreign governments seemed to share this impression. Before the coup, and together with his policy of Black recruitment, Breckinridge had adopted an astounding about-face in Europe by offering to start a plan of gradual emancipation in exchange for recognition. The official policy had been to frankly admit that the Confederacy fought for slavery and to assert that it had no constitutional authority to interfere with the institution. But then Breckinridge dispatched Duncan F. Kenner to Britain and France “to offer them exactly what the Confederate government had previously claimed it would not and could not do.” Kenner’s letter to James Mason and John Slidell claimed that the “sole object” of the South was “the vindication of our rights to self-government and independence,” and as such “no sacrifice is too great, save that of honor.” Breckinridge played coy, just saying that if recognition had not been offered due to some “objections not made known to us,” now the Confederacy was ready to consent to any terms. But by the time Kenner reached Europe, the Breckinridge government was no more.

Lord Palmerston, though still “conciliatory and kind,” now directly told Mason that he was merely an ordinary citizen, not representing any “organized government,” and intimated that he might even revoke the Confederacy’s status as a belligerent. This shows the shifting British opinions. News of Confederate atrocities had sapped much of the earlier support for the South, and the Junta had eviscerated the enthusiasm many Britons had had for the Confederacy as a plucky underdog. “The common opinion among the

reasonable is that Mr. Lincoln ought to subjugate the insurgents as a necessary precondition for peace, order, and law,” wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr. in quiet exultation. “Only the bitterest enemies of all that is American and

free dare to show any support for the rebel camp.” Nonetheless, neither Napoleon III nor Lord Palmerston accepted to hand the Confederate agents over to the American authorities, as Seward demanded, starting a saga that would have profound implications for international law regarding the nature of “legitimate” refuge.

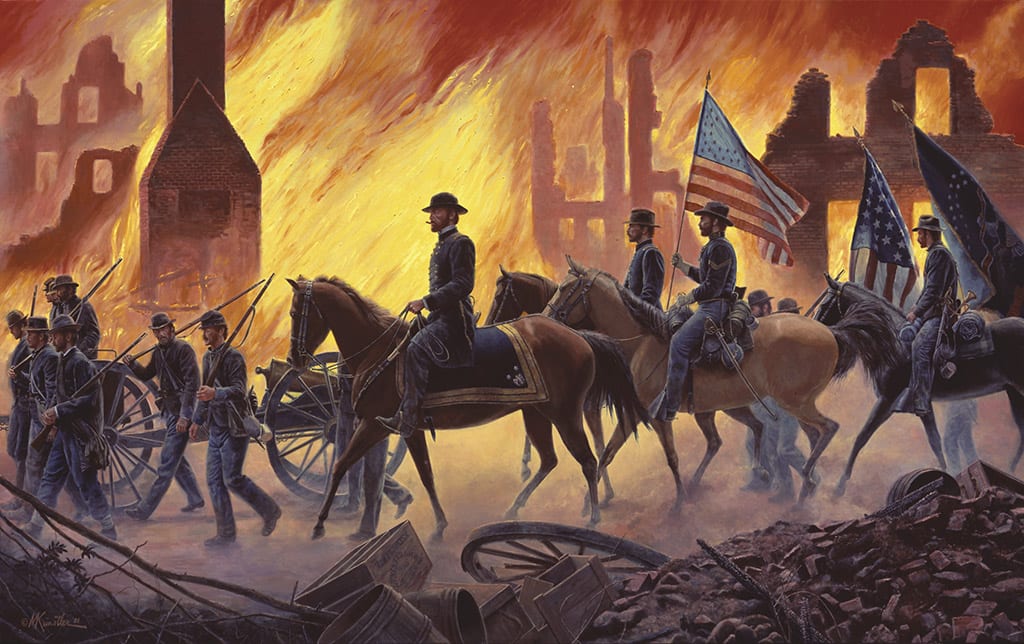

The Yankees celebrated their international triumphs. Rosecrans for instance reveled in how “the agents abroad of their bloody and hypocritical despotism,” who had had “the effrontery to tell the nations of Christendom” that the Union was the one carrying on a lawless warfare, were now “exposed and degraded, never again at freedom to spread their deceit.” Northerners, however, took greater heart in the start of Sherman’s March to the Sea, perhaps the most famous campaign of the Civil War. In early October, Sherman ordered all civilians expelled from Montgomery, after thoroughly wrecking the city’s infrastructure. This at the same time as Thomas likewise destroyed Atlanta and expelled its citizens. Orders from Philadelphia, however, were clear in how this was to proceed: the wealthy were to be go on their own, while the poor civilians were to be provided with supplies and boxcars. This was actually an inversion of Sherman’s original draft order, which contemplated giving the boxcars to Confederates of means. Despite this attempt to palliate the harshness of the order, accusations of barbarism were still hurled against the Union.

Sherman quickly sent back a pitiless reply. The people of the South could easily return to living “in peace & quiet at home” by stopping the war, which was “began in Error and is perpetuated in pride. We don’t want your negros or your horses, or your houses or your Lands, or any thing you have, but we do want and will have a just obedience to the Laws of the United States.” A curious statement given that those laws contemplated emancipation and confiscation too. Sherman thought that “some of the Rich and slave holding are prejudiced to an extent that nothing but death and ruin will ever extinguish,” but the “poorer & industrial classes of the South” would soon realize their “weakness and their dependence” upon the North if the Federal government could demonstrate its overwhelming might. “War is cruelty and you cannot refine it,” Sherman declared to the pleading Montgomery mayor. Sherman would “share with you the last cracker” as soon as peace came, but to bring that peace they had to first “make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war . . . make war so terrible . . . make them so sick of war that generations would pass away before they would again appeal to it.”

Sherman in this way envisioned a hard war followed by a magnanimous peace – but only for Whites. He would utterly ruin them at present, but were he in charge of Reconstruction he would then enact no emancipation, confiscation, or punishment as soon as they surrendered. Due to this, Sherman was little affected by the coup. In his opinion, the rebels remained enemies to be conquered, whether they were under Breckinridge or Toombs. Consequently, and despite some misgivings from Lincoln but with Grant’s full support, Sherman left Alabama with the purpose to “sally forth to ruin Georgia and bring up on the sea-shore.” Completely unmolested by Johnston’s troops and the scattered militia, Sherman’s four advancing columns carved a path of destruction that saw bridges and provisions burned, plantations sacked, and the infrastructure of the State utterly demolished. These “bummers,” in the words of one of them, “destroyed all we could not eat, stole their niggers, burned their cotton & gins, spilled their sorghum, burned & twisted their R. Roads and raised Hell generally.”

In Civil War lore, the March to the Sea has become a symbol of Northern vengeance and ruthless retribution. For decades unreconstructed rebels told tales of devastation and accused Sherman of being a war criminal, whose acts dwarfed the atrocities of the rebels. But like with other Yankee campaigns, the destruction was highly targeted. As soon as the march started Sherman had, in fact, ordered his men to “discriminate between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor and industrious, usually neutral or friendly.” Some of the most well remembered events were in fact retaliation for Confederate actions. For example, after the Southerners filled the roads with mines to try and slow down Sherman, he ordered Confederate prisoners to walk before his Army, stopping the practice. Likewise, although guerrillas were dealt with harshly, most common people had little to fear from Sherman’s troops. “If Georgians did not bushwhack or impede the march or attempt to conceal cotton inside,” historian Joseph Glatthaar states, “Sherman’s troops did not set fire to their homes, except in the case of prominent Confederates, whose homes universally received the torch.”

More than to simply wreak havoc, Sherman’s march also had the intended effect to break Southerners psychologically. Even as a major declared it a “terrible thing to consume and destroy the sustenance of thousands,” he perceptively wrote that “nothing can end this war but some demonstration of their helplessness . . . to produce among the

people of Georgia a thorough conviction of the personal misery which attends war, and the utter helplessness and inability of their ‘rulers’ to protect them.” Indeed, seeing tens of thousands of bluejackets marching freely through their territory, their soldiers utterly incapable to even slow them down, left in the Southern people a profound impression of the Union’s might. A woman wrote in despair of planters seeing “their crops destroyed; their businesses suspended; their servants gone . . . without even the present means of support, and nothing in prospect.” “The whole country here is a perfect waste, not a ear of corn scarcely to be found in this naked and famine stricken Southern Confederacy,” grieved another planter. A farmer reported to Richmond that “if the question were put to the people of this state, whether to continue the war or return to the union, a large majority would vote for a return,” even “if emancipation was the condition.”

The Junta seemed utterly incapable to respond to Sherman’s threat. Johnston had been restored to answer to the “urgent – overwhelming public feeling” in his favor, according to Howell Cobb. But now Cobb suddenly remembered that Johnston was “deficient in the qualities of a General.” Though Johnston had, if all militia and regulars were counted, some 38,000 men, he was unable to concentrate them effectively. This was due to Sherman’s superior strategy, for he moved his men so as “to induce the collection of troops at points at which he seemed to be aiming & then he has passed them by, leaving the troops useless and unavailable,” as a Confederate officer admitted. Through this strategy, Columbus, the second largest industrial center of the South, plus Macon and the state capital at Milledgeville, were all taken and destroyed, leaving all of them smoldering wreckages. It was “humiliating, to see the apprehension of the people of a country abandoned to the enemy,” Johnston admitted grimly, but “I can do nothing but annoy Sherman . . . In Georgia, at present, we are at Sherman’s mercy. It is in his power to

ruin us.”

The Junta believed the fault laid in the people, who had proven unwilling to make the necessary sacrifices. From Richmond came calls to engage in a strategy of scorched earth, to destroy all food and sustenance before Sherman could seize it, and to raise in insurrection. If the people “rise up behind him everywhere more defiant and unsubdued than ever,” the

Richmond Sentinel assured, “His track will be that of a bird through the air or a ship over the waters . . . Break in upon his array, and there will soon be a grand hunt, free for everybody, in which we hope everybody will join.” The

Augusta Constitutionalist in a similar fit of delusion promised that “our own citizens, without guns, can conquer the enemy.” Yet, this resistance failed to materialize, and attempts to enact these destructive plans just floundered. Confederate cavalry did engage in as much destruction as Sherman in some cases, burning “all the corn & fodder, driving off all the stock of farmers for ten miles,” which not only failed to slow down Sherman, but ensured the people would “not care one cent which army are victorious,” a civilian said.

To be sure, some people did maintain their defiance. Emma Holmes proclaimed that Southerners “would never be subdued, for if every man, woman, & child were murdered, our blood would rise up and drive them away.” Another woman, when taunted by a Federal who asked her what she would live upon now, replied “upon patriotism . . . you and your blood-handed countrymen may make the whole of this beautiful land one vast graveyard, but its people will never be subjugated.” They even spurned the aid of the Yankee Bureaus. “The enemy will dole out rations if we will take the oath, but who is so base as to do that?” declared a die-hard patriot. Even some who proved base enough to accept the rations expressed their bitter resentment. “They think they are so liberal, giving us food,” wrote a woman, when “they stole more from one planation.” As the

Richmond Daily Dispatch insisted, Sherman was only trying to “blind the people,” but his “savage instincts” remained, and patriotic Southerner civilians would not fall for “his game.” Such declarations seemed to prove true the

Sentinel’s assertion that “the vast majority of the people are unconquered & unconquerable.”

But the Southern soldiers

were conquerable, it seemed. Beauregard in Richmond told a frantic Toombs that to try and concentrate the Confederate forces to take a stand against Sherman would be “in violation of all maxims of the military Art,” for it would mean abandoning many cities that they needed to hold. A subordinate was skeptical, expressing that “the necessity of concentration and the abandonment of all secondary points was patent . . . but the paralysis of approaching death seemed to be upon the direction of our affairs.” When Sherman approached Savannah in late November, the 10,000 rebels defending it “decided that discretion was the better part of valor” and fled to South Carolina. At the same time as this happened, General Thomas had solidified his hold upon Northern Georgia, by means of both anti-guerrilla sweeps and liberal distribution of food and land. Northern newspapers reported enthusiastically that a “strong Union sentiment” was “winning its way among the citizens,” who were “availing themselves of the National Government’s protection and aid.” This was a “deliverance from the irresponsible power of the Rebel tyrants.”

Violence and destruction was especially targeted against plantations and the wealthy

Though as seen previously many rebels remained defiant, Sherman’s march was indeed received as deliverance by groups of Unionists and enslaved people. As in Alabama, thousands of slaves joined Sherman’s columns, and many took advantage of the path of destruction carved by the Yankee juggernaut to enact revenge on their rebel foes. Houses were sacked and plantations forcibly taken, and the arrival of Union forces usually resulted in either flight or imprisonment for masters and overseers. In yet another irony, Sherman, the unabashed racist and opponent of post-war punishment, furthered land redistribution by allowing Unionists, Black and White, to seize and work plantations – although merely to prevent the large throngs of freedmen from burdening his Army. Unfortunately, Sherman’s disdain, as in Alabama, inspired acts of brutality against the formerly enslaved, with the “bummers” sometimes plundering the slave quarters; and scant help was extended to the old and infirm, many of whom “died in the bayous and lagoons of Georgia.” According to Elizabeth R. Varon, Sherman’s Army even engaged in sexual violence against Black women.

Despite this abuse, the enslaved still jubilantly received their Liberators and aided them in their march. They advised them of rebel movements, revealed places where civilians had hidden food or supplies, and served in a variety of roles, including as soldiers despite Sherman’s enduring distaste. Now that the “Kingdom had Come” they also celebrated by asserting their freedom in a cathartic outpouring of “the pent-up resentment and fury of people forced to wait hand and foot, day after day, year after year, on those who owned them, beat them, and held over them the power of life and death,” in the words of Bruce Levine. In several cities they plundered houses and destroyed the property of the fleeing rebels. A young woman named Luisa justified this, stating that the houses of their enslavers “

ought to be burned” because “there has been so much devilment here, whipping niggers most to death to make ‘em work.” Property was not the only victim of their righteous wrath: Emma Holmes had a friend “chopped to pieces in his barn,” while a Union regiment arrived at a plantation and saw celebrating freedmen parading “beside a wagon that bore the remains of their murderer overseer swaddled in a flag.”

In Savannah, Sherman met with Secretary Stanton and leaders of the Black community. This interview was remarkable, for it punctuated both the social transformation wrought by the war and the emerging role of the Black community as an actor in the Reconstruction process. Here was one of the premier Union generals and a Cabinet Secretary meeting with Black people, and asking for their advice regarding how to deal with their liberated brethren. The group who met with Stanton and Sherman also were examples of the foundations upon which freed communities would be built after the war, including Black Ministers, Bureau workers, and Union Army soldiers. They also showed a complete comprehension of the war issues, with their leader, the Baptist Minister Garrison Frazier, acknowledging that “the object of the war was not at first to give the slaves their freedom, but . . . to bring the rebellious States back into the Union.” But the rebels refusing to be “reduced to obedience” had “now made the freedom of the slaves a part of the war.” As to what was to be done now, Frazier said “the way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land . . . we want to be placed on land, to till it by our own labor, and make it our own.”

In response, Sherman produced yet another General Order confirming the informal land redistribution and “pre-emption” of land throughout Georgia, while Stanton forwarded orders to Thomas to bring Northern Georgia under a firmer Union grip by expanding the occupation and setting up Bureau and Army offices. James Lynch, one of the delegates, wrote that “we all went away from Gen. Sherman’s headquarters that night, blessing the Government, Mr. Secretary Stanton, and General Sherman. Our hearts were buoyant with

hope and thankfulness.” For the rebels, Sherman’s march instead filled their hearts with despair. A former Senator now said that the people recognized at last the “hopelessness of success . . . and the wisdom of the late Mr. Breckinridge.” Sherman’s march had left slavery “torn up root and branch” throughout Georgia, the

Macon Telegraph and Confederate declared, the situation now a “picture of national military disaster.” A Black Union soldier also recognized this, writing that “the rebels see that their cause is hopeless; but their wicked hearts will not let them acknowledge their defeat . . . they will have to succumb shortly, or, like Pharaoh, be overthrown.”

Union Army troops advancing through the South Carolina swamps

The disaster, unfortunately for the rebels, was far from over. In South Carolina, though Johnston had been able to muster some 40,000 men by a combination of impressment and emergency levies, his men remained tired and undersupplied. Johnston also grumbled that he was bleeding soldiers by the thousands, as many Georgians refused to abandon their State. While the start of a harsh winter had paused military operations in Virginia, Grant was decided to keep up the pressure in South Carolina, sending Sheridan as reinforcements for Sherman. Sherman marched across the tidewater swamps, which rebel engineers thought “absolutely impossible” to cross in winter. At the same time, Sheridan managed to cross the Savannah River at Augusta, only facing nominal opposition. Crossing cold, neck-deep water, the bluejackets used new Spencer carbines with waterproof cartridges, loading them underwater. “Look at them Yankee sons of bitches, loading their guns under water! What sort of critters be they, anyhow?” asked the dumbfounded rebels. However, the weather now proved the greatest foe, as both Sheridan and Sherman struggled to cross the chilly waters of swamps covered by felled trunks and mines.

The campaign in South Carolina already proved to be much more destructive than the one in Georgia. Sherman admitted to Philadelphia that “the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina. I almost tremble at her fate, but feel she deserves all that seems to be in store for her.” A soldier so declared, saying the “Cradle of Secession” ought to “suffer worse than she did at the time of the Revolution . . . Here is where treason began, and by God, here is where it shall end!” Another plainly, ruthlessly told a woman that “they were sorry for the women and children, but South Carolina must be

destroyed.” Sheridan’s troops laid waste to the State as well, the ebullient Federal declaring that the “people must be left nothing, but their eyes to weep with over the war.” The rebel soldiers helped in this destruction, for in desperation the Junta had approved a strategy of scorched earth, burning barns, despoiling civilians, and destroying railroads before Sherman could. The effect of these twin campaigns was devastating, spreading hunger, forcing thousands to flee, and contributing to the start of the 1864-1865 Southern Famine.

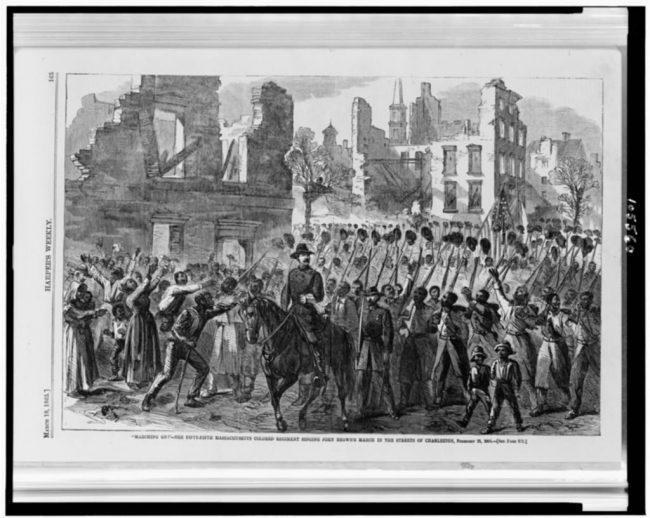

Yet, this also failed to slow down Sherman. Through “pioneer battalions” mostly formed out of freedmen, Sherman managed to corduroy roads, build bridges, and open his way through the swamps Johnston’s engineers had declared impassable. “When I learned that Sherman's army was marching through the Salk swamps, making its own corduroy roads at the rate of a dozen miles a day,” admitted Johnston, “I made up my mind that there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar.” By late December, Sherman had reached Branchville, but the start of torrential rains plus the worse terrain were finally proving an obstacle. “The march to the sea seems to have captured everybody,” Sherman observed after the war, “whereas it was child's play compared with the other.” However, the focus on land kept the rebels from appreciating the threat on the water. Because almost the entire garrison in Charleston and the surrounding areas had been withdrawn to at last concentrate against Sherman, the city was particularly vulnerable. In early December the forts on James Island were captured, and then Fort Sumter was bombarded into rubble. Finally, on December 20th Charleston was assaulted by Union troops of the Department of the South, including Black regiments, quickly surrendering.

The surrender of the “Citadel of Treason” after several failed attempts since 1863 was a powerful symbol of the Revolution. Leading a company of Black troops was Robert Smalls, the former slave who had escaped by commandeering a Confederate ship. Smalls had been included in earlier expeditions against Charleston, being quietly given more and more duties over the Sea Island regiments he raised. By the time of this final attack, he was a

de facto captain, though he was yet to receive an official commission. Though the gutted Southern garrison surrendered meekly, the meaning of a capitulation to Black soldiers, many of them former slaves like Smalls, escaped no one. Four years ago, the city had still been wildly celebrating secession, White citizens going wild at every new state that seceded during the winter. Now they watched, grim and depressed, from the shade, while the Black population came onto the streets and cheered jubilantly the arrival of the troops, letting out a specially loud shout when Smalls himself raised the Stars and Stripes over the city. This seemed like the “triumphal return of some favorite hero, rather than the entry of the conqueror,” commented a White Yankee. But Smalls was both conqueror and liberator that day.

The Fall of Charleston had such an electric effect that Sherman, who despite his racism could still appreciate a soldier’s bravery, sent a message to Lincoln where he praised the “courageous actions of the colored troops,” and jauntily declared that “Charleston makes for a fine Christmas gift.” A fine gift it was, indeed. The elated Lincoln sent “many, many thanks” to Sherman, and then formally appointed Smalls the first Black commissioned officer in the US Army. The newly appointed Colonel Smalls was present when Charleston’s Black and White Unionists met to celebrate the New Year. The former slave and current US Army Chaplain William H. Hunter led the congregation in prayer. To profound shouts he presented “the brave Liberator, Colonel Robert Smalls;” talked of how “as black a man as you ever saw, preached in the city of Philadelphia to the Congress of the United States” shortly before that; and then proudly announced that the Boston lawyer John S. Rock, a Black man, had been “admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States.” These were all potent signs that showed that “now you are all free.” Hunter concluded: “Thank God the armies of the Lord and of Gideon has triumphed and the armies of Pharaoh have been driven back and scattered like chaff before the wind.”

Black soldiers entering Charleston

Sherman’s campaign had succeeded in his intended goal to “whip the rebels, to humble their pride, to follow them to their inmost recesses, and make them fear and dread us.” Though there remained a few who insisted that the war could still be won, most Southerners now were in a despairing mood, and could recognize the folly of secession and then of the coup. Even the heretofore indefatigable Josiah Gorgas now wondered “Where is this to end? No money in the Treasury—no food to feed the army—no troops to oppose Gen. Sherman . . . Is the cause really hopeless? Is it to be lost and abandoned in this way?” Even though the

Richmond Dispatch fantasized that this should “rather inspire cheerfulness than gloom” because it freed Johnston from defending “fixed points,” most had resigned themselves instead to catastrophic defeat. “All is gloom, despondency, and inactivity,” wrote a South Carolinian. “Our army is demoralized and the people panic stricken . . . The power to do has left us . . . to fight longer seems to be madness.” Part of this hopelessness came from the military victories of the Union, but it also resulted from the political triumph of Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 Northern elections, which committed the Union not only to victory but to an increasingly Radical and Revolutionary program that Southerners seemed incapable of resisting anymore.