I mean OTL they didn't need to try and rush things since Atlanta fell and basically secured Lincoln's reelection. If Atlanta takes till after the election with Lincoln having lost it things could be moved up. IIRC Grant was planning on a full out assault on Petersburg if Lincoln lost for example.But wouldn't the South just try to play for time? There's not much they could meet in the middle on, unless Lincoln acceded to either their succession or slavery. And there's not much chance Sherman or Grant could have forced the issue in those months since they didn't OTL.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"Exactly. David and Beauregard can give orders all day, but all it takes is one fire eater deciding to force the hands of his superiors, or even getting a mistaken order, and well....Yes, I'm not sure I'd disagree with that. I think Davis and Beauregard had the self-restraint, but they couldn't stand behind every Southron with a gun or a battalion under his command. And there's evidence that Lincoln appreciated this reality. And maybe, deep down, Davis did, too.

Exactly. David and Beauregard can give orders all day, but all it takes is one fire eater deciding to force the hands of his superiors, or even getting a mistaken order, and well....

To be sure, the North was not without fire eaters of its own. Consider Fremont's behavior when he was put in charge in St. Louis in '61. Or the Red Legs.

But on the whole, they tended to be a more manageable lot than the South's.

So I had one of those dreams last night where you are watching or reading and then you are sort of part of the action at the same time period. And it involved this time line.

Discussion of who should follow Lincoln. sort of turned into? A. Republican national convention with all of us as delicates. And like the voice from the rafters in 1940 that sealed it for FDR, discussion turned into. Excitement as lots of people got on board with the suggestion that Red could have someone become a military hero and very well known, yet decide to serve only one term because he found the office to be ludicrous and he wanted to prove a point. So he would just follow everything the radical republicans wanted with a spirit of humor and a bit of satire about how crazy the South had been to rely on cotton so much. All while telling his Vice President, Grant, stories of the King and the Duke to help him to see that he shouldn't just trust anyone without looking into whether they would be honest, including his friends.

Oh yes, the president who followed Lincoln in my dream in this timeline would be none other than Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain.

Far too gimmicky for this well crafted timeline. But I thought Red would get a big kick out of it. (Plus I just checked and he would be too young.)

Discussion of who should follow Lincoln. sort of turned into? A. Republican national convention with all of us as delicates. And like the voice from the rafters in 1940 that sealed it for FDR, discussion turned into. Excitement as lots of people got on board with the suggestion that Red could have someone become a military hero and very well known, yet decide to serve only one term because he found the office to be ludicrous and he wanted to prove a point. So he would just follow everything the radical republicans wanted with a spirit of humor and a bit of satire about how crazy the South had been to rely on cotton so much. All while telling his Vice President, Grant, stories of the King and the Duke to help him to see that he shouldn't just trust anyone without looking into whether they would be honest, including his friends.

Oh yes, the president who followed Lincoln in my dream in this timeline would be none other than Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain.

Far too gimmicky for this well crafted timeline. But I thought Red would get a big kick out of it. (Plus I just checked and he would be too young.)

Last edited:

Your timelines getting Into people's subconscious red congratulations!So I had one of those dreams last night where you are watching or reading and then you are sort of part of the action at the same time period. And it involved this time line.

Discussion of who should follow Lincoln. sort of turned into? A. Republican national convention with all of us as delicates. And like the voice from the rafters in 1940 that sealed it for FDR, discussion turned into. Excitement as lots of people got on board with the suggestion that Red could have someone become a military hero and very well known, yet decide to serve only one term because he found the office to be ludicrous and he wanted to prove a point. So he would just follow everything the radical republicans wanted with a spirit of humor and a bit of satire about how crazy the South had been to rely on cotton so much. All while telling his Vice President, Grant, stories of the King and the Duke to help him to see that he shouldn't just trust anyone without looking into whether they would be honest, including his friends.

Oh yes, the president who followed Lincoln in my dream in this timeline would be none other than Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain.

Far too gimmicky for this well crafted timeline. But I thought Red would get a big kick out of it. (Plus I just checked and he would be too young.)

I also had a civil war dream but it was actually basically a stonewall Jackson wank documentary.I woke up[well changed dreams] when the narrator said something like "Best Miltary campaign of all time"

Really depends on the final events of the Civil War and the aftermath and Reconstruction.

Gullah - Wikipedia

en.m.wikipedia.org

I wonder how the Gullah people will be affected in this TL.

On the one hand, the somewhat sad truth is that a more successful and overall comprehensive Reconstruction essentially removes a lot of the isolation that the Gullah would have from neighboring populations, and as a result they're likely to assimilate even faster than they did IOTL if their states don't deliberately isolate them. Though that could also impact the local dialect of English much more and be interesting in its own way, I suppose, creating a bit of a divide within the South as to their linguistic and cultural heritage that Northerners might not be entirely opposed to.

On the other, depending on other developments, if like in Male Rising the Reconstruction is still not complete depending on the state or the Gullah successfully argue for a cultural autonomy similar to Native American Reservations, they may have the opportunity to entrench and otherwise protect their language/dialect better as a measure of black identity. That's asking quite a lot though and I'm not sure how realistic it is in this scenario unless Reconstruction isn't as totally successful and comprehensive as Red has been hinting at.

I can see one way, though it may not be possible for the entire Gullah community. However, with the Federal government focused on protecting all these areas, and the needs of communities to fend for themselves at times, you could get some organizer who decides they are going to split some of the Gullah off into a sort of experimental community, one of the numerous utopians that pop up from time to time. Since they are already distinct, it could be something that some dreamer is given a chance to do that they might not with the general population.Really depends on the final events of the Civil War and the aftermath and Reconstruction.

On the one hand, the somewhat sad truth is that a more successful and overall comprehensive Reconstruction essentially removes a lot of the isolation that the Gullah would have from neighboring populations, and as a result they're likely to assimilate even faster than they did IOTL if their states don't deliberately isolate them. Though that could also impact the local dialect of English much more and be interesting in its own way, I suppose, creating a bit of a divide within the South as to their linguistic and cultural heritage that Northerners might not be entirely opposed to.

On the other, depending on other developments, if like in Male Rising the Reconstruction is still not complete depending on the state or the Gullah successfully argue for a cultural autonomy similar to Native American Reservations, they may have the opportunity to entrench and otherwise protect their language/dialect better as a measure of black identity. That's asking quite a lot though and I'm not sure how realistic it is in this scenario unless Reconstruction isn't as totally successful and comprehensive as Red has been hinting at.

Once the very extensive Reconstruction finally does set in by the early 1880s or whenever, this community might be forced to integrate somewhat, but it would be more like the Amish do in some areas today, where at least in my area they live rather independently, but they consistently interact with society b y being well known for excellent hand-crafted furniture, some very good restaurants with food that is all local (and, one presumes, organic), excellent builders, and so on

In other words, they need to be given a niche that will allow them to plausibly continue because "why mess with a good thing?" while the Feds are still busy doing Recontsruction.

It's hard to believe that's something that still happens nowadays.Its completely rational for that to anger you. I've met a fair number of students on campus who have denied that slavery was even a factor in the Civil War because the northern states were also racist. While we should be willing and able to critique historical figures, I feel that people often go too far because, like you said, they don't share the same morals of a 21st century person.

Hm, a very interesting group whose existence I wasn't aware of.

Gullah - Wikipedia

en.m.wikipedia.org

I wonder how the Gullah people will be affected in this TL.

I know that, at the very least, historians like James McPherson and Bruce Levine have made similar arguments that the Confederate leadership and public both believed and understood that they could not win a war of attrition without foreign support because they recognized the material superiority of the Union. Their belief that Southern gallantry evened the outs, and their at least initial denial of the fragility of slavery as a system, made them believe that the odds were better than it seemed at first, but ultimately most Southerners were aware that they could only truly win if they obtained foreign support, broke the Northern will, and kept up their own morale. Only flashy victories would achieve such a thing. Frankly, I believe they were right. Big victories over the Federals, costly as they were, managed to bring the Yankees close to a morale crisis at several points, and almost obtained the recognition of Britain and France. It's hard to imagine the Confederates maintaining the contest for 4 years as they did OTL if the contest was just retreat after retreat, yielding territory without a fight, without a single big victory over the Union Army. Such a strategy may preserve the manpower and resources of the Confederacy, but it could hardly protect slavery (the mere presence of Federal troops disrupted it enormously even before the adoption of explicitly anti-slavery policies), would definitely not earn the respect of foreign powers, and would protect the morale of the Yankees while driving Southerners into despair and pessimism.OR: Who the hell, on either side of the conflict, would've, even for a moment, thought that the CSA stood a snowball's chance in hell in a drawn-out, attritional conflict with the Union?

An excellent book that has supplied me with a wealth of knowledge that I have put to good use in the TL. I wish I had read it much sooner. Earlier chapters would definitely have benefited from that.If anyone is interested, look up Fall of the House of Dixie, it's a good scathing look at the South's culture then.

Yes, a lot of people who wonder why the Confederacy didn't yield large parts of its territory in the expectative that Northerners would then be driven back, akin to Washington and other Continental leaders during the Revolution, forget that the Confederacy was meant to preserve slavery and the Southern "way of life", something which required the continuous, violent pressure of the State. Even if the Union never adopted emancipation as a policy, it was clear from the start of the war that the Union Army would never provide the necessary pressure to maintain slavery in the territories it occupied. The great majority of soldiers and officers rejected the idea of being "slave catchers", and there was important pressure in favor of emancipation since the start of the war. If the Confederate Army retreated, the areas put under Federal occupation would be fundamentally transformed and slavery irretrievably weakened even if the Southerners then retook them.As I read GG, it's a question of two societal expectations:

1) Understanding that southern society and economy could not survive large parts of it being overrun by hostile Union armies;

2) An expectation, built on a chivalric self-understanding that had developed in the antebellum period, that southern arms should mainly conduct themselves on the offensive.

Lee delivered the kind of war that southerners desired, and which they felt was necessary.

I think there was more understanding of the enormous northern advantages in industrial power; but Southerners banked on the North lacking the willpower to employ it. Even Lee, who was surely more sober in his expectations than the typical fire-eaters, had banked his two offensives into the North on this expectation.

The final point is also important, for most Southerners believed that the Northerners simply didn't have enough motivation to keep up the contest in the face of Southern resistance. In their minds, Northerners had no reason to fight and would most likely decide the war wasn't worth it if the Confederacy resisted with enough vigor. That's why the results of the 1864 elections were such a bitter, demoralizing blow - Northerners showed unequivocally that they still supported a government committed to the destruction and unconditional defeat of the Confederacy, despite the grievous losses and sacrifices of the past years.

The second would be an interesting scenario but most likely a grim one, because even if Lincoln manages to win the war before the next president is sworn in, you can be sure that Reconstruction under Little Mac would be even worse than under Johnson. That, however, opens up interesting butterflies. The OTL 1866 elections showed that a majority of the North felt that a just settlement of the war involved at least a measure of reconstruction instead of a mere restoration of the Union as it was as the Democrats wanted. Would they stand by as McClellan and his Democrats allies give the former Confederates all they wanted and more, practically restoring the Slave Power? Slavery would most likely survive in this scenario, at least legally, and with a Democratic Congress we would most likely see former Confederates being elected and sat in Congress in less than a year. Could this be enough to spark a second civil war, with most Northerners unwilling to swallow a peace that seems rather like a defeat? It would be a rather bleak TL, but yes, an interesting one.Realistically the CSA only really had two chances to win the war and even with the second they'd still likely fall. The first is Lees orders for Antietam aren't lost and he whips Little Mac during the battle. The subsequent European recognition and Republican losses in the upcoming midterms force Lincoln to the table.

The second is Sherman fails to take Atlanta until after the 1864 election which results in Little Mac winning. However Lincoln still has until March and you can be damned sure He along with Grant and Sherman are going to do everything they can to win it before Mac takes the oath of office.

Honestly that second one is a TL I'd love to see.

Their mindset was simply illogical to a degree that boggles the mind sometimes. They directly and candidly said they would rather see every slave freed by Lincoln than taken for a minute by Davis, all because the second option was less honorable. Their refusal to give an inch led them to their own destruction time and time again.Their mindset was against it from the start. They felt not being allowed to do whatever they wanted was being oppressed.

Like, even if you look at their attempts at "compromise" before the War, it was more or less telling Lincoln to lose his entire platform, even though he won.

Being a Master in essence, give them a quickness to harsh responses to any form of challenge, casual attitudes on violence, and being pissed at anyone who wanted to fuck with their perogatives, including their "property".

As a result, they never could stand to lose anything, or give up anything.

Your arguments are basically the same ones Republicans and abolitionists wielded in the 1850's.Ya, basically. I have had a very strong conviction for several years at this point that [early-modern-industrial trans-Atlantic chattel slavery] slavery is a slow, insidious poison for a society, which inevitably, inextricably, leads to a society that is violent, hard-hearted, deeply unequal (even among the enslavers), and other wise an antithesis to the sort of society imagined by Enlightenment thinkers and what Enlightenment thought and ideals strives to achieve.

That's more or less what their grand strategy was reduced to by 1864. Because they no longer had the capability to even have the pretense of doing anything else (Jubal Early's surprising heroics notwithstanding).

It is, however, interesting to think about scenarios where Jefferson Davis decides not to fire on Fort Sumter or Pickens. How long could that standoff play out? Could Lincoln ever reach a point where he was willing to squash secession by firing the first shot? The longer the crisis dragged on, the more difficult it could become for the Lincoln Administration.

I agree with @Knightmare. I believe circumstances forced Davis' hand, to a degree that if he hadn't fired the shot, some hotheaded soldier or officer would have done so starting the war in worse conditions for the South. The Confederate position was that Fort Sumter was a territory of theirs illegally occupied by a foreign power. Allowing the Union to resupply it (because I believe Lincoln wouldn't have ever approved for it to be given up) would implicitly recognize that the Confederacy did not have complete control over all the lands it claimed, a basic attribute of nationhood. It was, then, an unthinkable choice. If Davis did nothing as Lincoln resupplied the forts, he would be weakening his government and demoralizing his people, at the same time gutting the hopes of foreign recognition and probably blunting the pro-Confederate movement in the Upper South. If we accept the interpretation that Lincoln knew all this and planned the resupply mission with the explicit expectative that Davis would fire on the ships, that's a proof of Lincoln's political genius because it started a war that was most likely unevitable in the best possible conditions for the North. More direct aggression would most likely have resulted in greater divisions within the Northern people and stronger pro-Confederate sentiments in the Upper South, and maybe even the Border States.Honestly, it wouldn't. Remember, the South got called Fire Eaters for a reason. All Lincoln would've had to do is wait for some hothead on the South's side to pull the lanyard, and he wins.

Yes, I find this rather funnySo I had one of those dreams last night where you are watching or reading and then you are sort of part of the action at the same time period. And it involved this time line.

Discussion of who should follow Lincoln. sort of turned into? A. Republican national convention with all of us as delicates. And like the voice from the rafters in 1940 that sealed it for FDR, discussion turned into. Excitement as lots of people got on board with the suggestion that Red could have someone become a military hero and very well known, yet decide to serve only one term because he found the office to be ludicrous and he wanted to prove a point. So he would just follow everything the radical republicans wanted with a spirit of humor and a bit of satire about how crazy the South had been to rely on cotton so much. All while telling his Vice President, Grant, stories of the King and the Duke to help him to see that he shouldn't just trust anyone without looking into whether they would be honest, including his friends.

Oh yes, the president who followed Lincoln in my dream in this timeline would be none other than Samuel Clemens, also known as Mark Twain.

Far too gimmicky for this well crafted timeline. But I thought Red would get a big kick out of it. (Plus I just checked and he would be too young.)

Of course, when we get there we'll probably need a more serious debate. We'll see what happens.

That's a great honor!Your timelines getting Into people's subconscious red congratulations!

I also had a civil war dream but it was actually basically a stonewall Jackson wank documentary.I woke up[well changed dreams] when the narrator said something like "Best Miltary campaign of all time"

I am imagining Johnny Reb from Checkmate Lincolnites narrating your dream.

I must emphasize that on the name of realism there are limits to what I believe can be achieved. The standards for a successful and comprehensive Reconstruction are different for everyone, but I believe we all understand that the TL resulting in perfect equality and peace in 1865 would be completely unrealistic, borderline ASB. There's still a lot of TL to go through first, and while I do have a blueprint it's always subjected to change depending on my research and the feedback I receive, so I say that it's too early to talk of how Reconstructions ends right now.That's asking quite a lot though and I'm not sure how realistic it is in this scenario unless Reconstruction isn't as totally successful and comprehensive as Red has been hinting at.

I'm not sure that the South could sustain another Civil War in this scenario, since slavery would have been pretty gutted (as you yourself note) by Northern military actions and so many of their young men had fallen. Could the South have rallied men to the flag again in order to fight another war when they only barely, and by a stroke of political fortune, won the last one? This time they have to know there will be much more of a Reconstruction--in fact, I suspect that this has a reasonable chance of leading roundabouts back to a very radical Reconstruction, as the North looks around and says "We fought all of this and got peace for this? Damn the South, Lincoln was right!" or something to that effect.The second would be an interesting scenario but most likely a grim one, because even if Lincoln manages to win the war before the next president is sworn in, you can be sure that Reconstruction under Little Mac would be even worse than under Johnson. That, however, opens up interesting butterflies. The OTL 1866 elections showed that a majority of the North felt that a just settlement of the war involved at least a measure of reconstruction instead of a mere restoration of the Union as it was as the Democrats wanted. Would they stand by as McClellan and his Democrats allies give the former Confederates all they wanted and more, practically restoring the Slave Power? Slavery would most likely survive in this scenario, at least legally, and with a Democratic Congress we would most likely see former Confederates being elected and sat in Congress in less than a year. Could this be enough to spark a second civil war, with most Northerners unwilling to swallow a peace that seems rather like a defeat? It would be a rather bleak TL, but yes, an interesting one.

(That, or they blame everything on blacks and become even more racist than the South)

It's interesting how much this resonates with Imperial Japans strategy during WWII. The enemy does not have the willpower or fortitude we have to endure and we are better warriors anyways so all we have to do is inflict bloody defeats on them and they will eventually tire of the blood and give up the fight.The final point is also important, for most Southerners believed that the Northerners simply didn't have enough motivation to keep up the contest in the face of Southern resistance. In their minds, Northerners had no reason to fight and would most likely decide the war wasn't worth it if the Confederacy resisted with enough vigor.

This is a big reason why the Japanese fumbledIt's interesting how much this resonates with Imperial Japans strategy during WWII. The enemy does not have the willpower or fortitude we have to endure and we are better warriors anyways so all we have to do is inflict bloody defeats on them and they will eventually tire of the blood and give up the fight.

Expecting willpower and fortitude of the people you attack to be low is always a nonsensical proposition

what racism does to a mfer

Well with Japan if just giving up isn't tenable for political reasons and you have the odds stack HEAVILY against you your only real option is to throw a Hail Mary. It probably won't work but sometimes that's your least bad option.This is a big reason why the Japanese fumbled

Expecting willpower and fortitude of the people you attack to be low is always a nonsensical proposition

what racism does to a mfer

It's interesting how much this resonates with Imperial Japans strategy during WWII. The enemy does not have the willpower or fortitude we have to endure and we are better warriors anyways so all we have to do is inflict bloody defeats on them and they will eventually tire of the blood and give up the fight.

I think the reasoning worked like this: 1) That expectation had worked against Russia in 1904-05; and 2) the Japanese leadership thought the Yankees were softer than their forebears had been in the 1860's.

Whoops.

But then, it strikes me that so many of the losses in modern wars have been the result of catastrophic miscalculation of enemy willpower. The Confederacy is certainly a case in point!

Hell not even modern wars even, just look at Hannibal and Carthage in the 2nd Punic war.But then, it strikes me that so many of the losses in modern wars have been the result of catastrophic miscalculation of enemy willpower. The Confederacy is certainly a case in point!

Yup. There's some good antecedents in Fall that mention that exact same thing.Their mindset was simply illogical to a degree that boggles the mind sometimes. They directly and candidly said they would rather see every slave freed by Lincoln than taken for a minute by Davis, all because the second option was less honorable. Their refusal to give an inch led them to their own destruction time and time again.

"Have you noticed the strange conduct of our people during this war? They give you their sons, husbands, brothers & friends, and often without murmuring, to the army but let one of their negroes be taken and what a houl [sic] you will hear."

-Georgia Congressman, Warren Akin

It's especially hilarious when you read the Confederacy would request the planters send their slaves to help dig fortifications, and they'd be refused, sometimes saying to offer to some of his men more pay to do the work instead.

And then we have the army wishing to relocate slaves so they aren't providing intelligence to the Union, and the planters start whining about how theat would tread on the Mater's right to use and move their human property whereever they wished.

I won't even talk about, and this is in '64 BTW, a Confederate officer goes to a plantation in South Carolina to impress a share of the owner's corn crop.

Planter refuses, tearing up the order and binning it out the window. Two reasons why. First is he gets far more cash on the open market vs impressment. Second is, submitting to impressment means "branding on my forehead 'Slave'".

To say nothing about the insanity that say, the Memphis Appeal put out, namely oh no, the planters didn't lose their selfless spirit, instead, it's because the government treated them unfairly and put burdens on them. Remove all those unwarranted and harmful edicts and planters would do their full duty by the country.

Honestly, it's a miracle they lasted half as long as they did.

That is the thing. It almost did not work. By 1905 the Japanese economy and military was also seeing the strain of just one and half year of high intensity warfare. If Russia had held out six more months a compromise peace was a big likelihood. Taking on a stronger opponent, who borders you is always a bad gamble.I think the reasoning worked like this: 1) That expectation had worked against Russia in 1904-05

That is the thing. It almost did not work. By 1905 the Japanese economy and military was also seeing the strain of just one and half year of high intensity warfare. If Russia had held out six more months a compromise peace was a big likelihood. Taking on a stronger opponent, who borders you is always a bad gamble.

Absolutely, and this of course is not only one of the lesser known aspects of the War (not even appreciated at the time by Japanese votaries at the time, who failed to appreciate why Japan's delegates at Portsmouth settled for such a "disadvantageous" peace) . . . I think you can argue that Japanese military leadership had already internalized a bit of "retconning" of it by the time 1940-41 had rolled around. Too high on their own supply!

Last edited:

Just to be clear, what I personally meant by "all-encompassing" and "comprehensive" is more just Reconstruction across the whole region that goes deeper than OTL. My read, erroneous as it possibly may be, is that Reconstruction and the barriers it has are going to be a South-wide regional phenomena, as opposed to the Male Rising style situation where it was very, very different between states, though that could be wrong in terms of what you're intending. Avoiding full-on Jim Crow by no means indicates true political and cultural equality, and I didn't mean to imply as such.I must emphasize that on the name of realism there are limits to what I believe can be achieved. The standards for a successful and comprehensive Reconstruction are different for everyone, but I believe we all understand that the TL resulting in perfect equality and peace in 1865 would be completely unrealistic, borderline ASB. There's still a lot of TL to go through first, and while I do have a blueprint it's always subjected to change depending on my research and the feedback I receive, so I say that it's too early to talk of how Reconstructions ends right now.

I'm not expecting perfect equality, I'm just going by what I've interpreted from the posts that social changes will be on a wider regional level, though if there are differences to that where different states end up being better than others, I think that's entirely realistic.

There are a lot of interesting parallels between Japan and the CSA. I found an article last year that specifically compared Lee at Gettysburg with Yamamoto at Midway:It's interesting how much this resonates with Imperial Japans strategy during WWII. The enemy does not have the willpower or fortitude we have to endure and we are better warriors anyways so all we have to do is inflict bloody defeats on them and they will eventually tire of the blood and give up the fight.

Gettysburg and Midway: Historical Parallelsin Operational Command

The purpose of this study is to show the profound effect a commander in chief’s approach to operational command can have on the course of events in war. It does so by analyzing the performance of two operational l lev el commanders in chief, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of...

digital-commons.usnwc.edu

Chapter 52: They Will Think It's Gabriel's Horn

A debate that has echoed throughout the years has been that of whether the Confederacy could have won the Civil War. Many people are convinced that this was an impossibility due to the Union’s material superiority; and yet, history exhibits many examples of outmatched groups triumphing against the odds. The clearest one is, of course, the victory of the American rebels over mighty Britain during the First American Revolution. Inspired by that memory, Confederate rebels had reasons to hope they would manage to overcome the might of the Union and avert the Second Revolution. In August 1864, it seemed that they had all but managed it, with Richmond, Atlanta, and Mobile all standing defiant before the Yankee juggernaut. Reinvigorating Northern morale, shattering Southern spirits, and assuring that the Union would indeed stand triumphant at the end was only accomplished through important victories in Atlanta and Mobile. These were not a given, but the result of Yankee bravery and determination. The Confederacy did not lose the war because it was pre-destined to do so, but because the Union proved superior to it in strategy, use of resources, and leadership. Mere material superiority wouldn’t have produced the victories that turned the tide in September 1864.

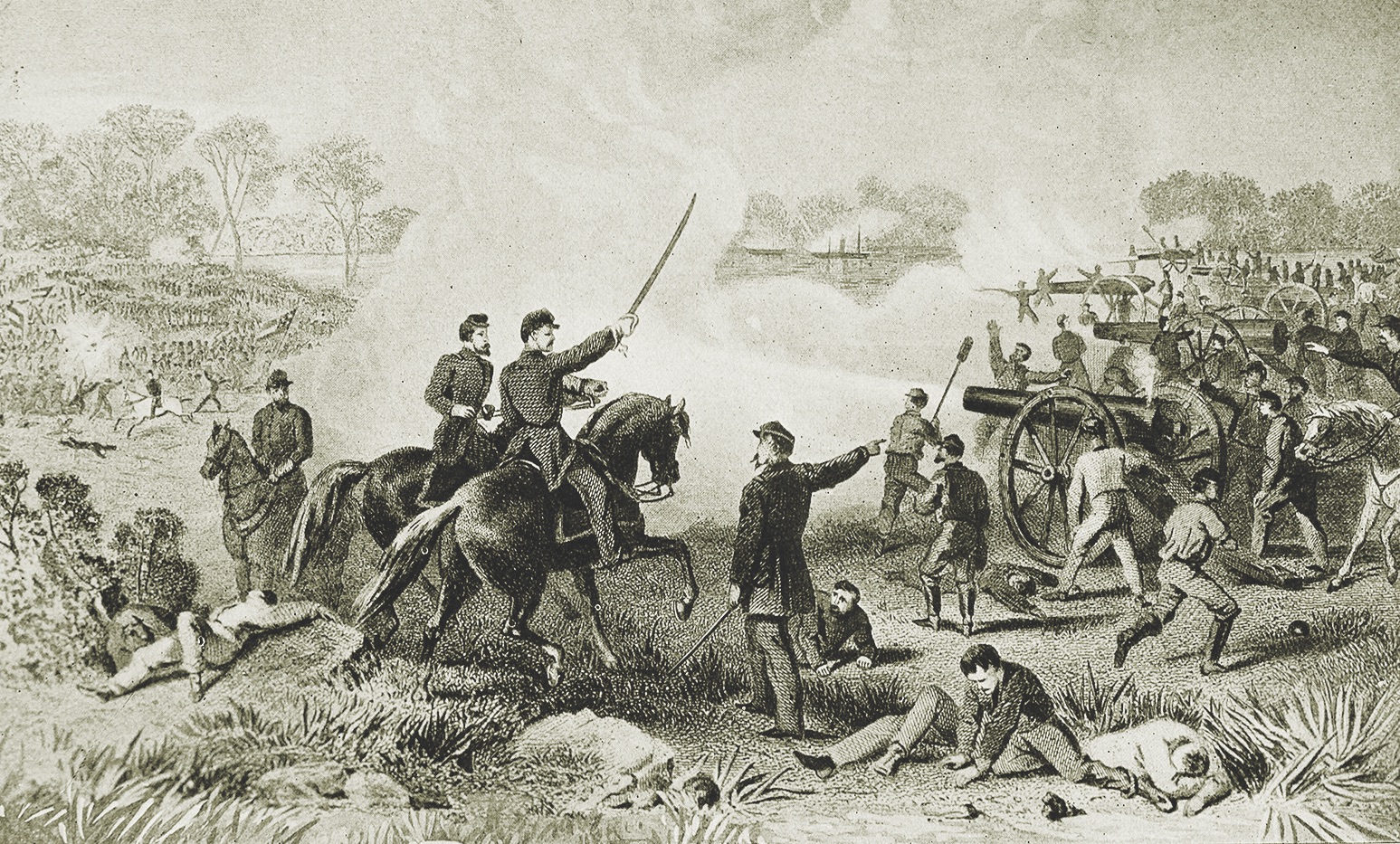

Showing the importance of coordinated strategy to the Union war effort, the movements that resulted in the fall of Atlanta and Mobile started towards late August, benefiting from a renewed drive towards Richmond by the Army of the Susquehanna. The main Union Army in the East was now under Grant’s complete tactical and strategic direction following the removal of General Hancock, who had been replaced by General John Sedgwick. Nicknamed “Uncle” by his men due to his smart and affable nature, Sedgwick was a capable and beloved commander. A West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican War, Sedgwick had served with bravery and distinction since the start of the war. Despite his personal charm and military competence, Sedgwick however seemed to lack ambition and dread responsibility. In appointing him, Grant merely intended to have a subordinate that would always faithfully execute his orders, instead of resisting them like Hancock had done. Theodore Bowers, a member of Grant’s staff, bluntly stated that Sedgwick was “a mere staff officer . . . He has no control over troops except as Grant delegates it. He can give no orders and exercises no discretion. Grant now runs the whole machine.” Moreover, due to his genial personality and seniority Sedgwick was also acceptable to all other commanders, side-stepping another possible struggle for the position.

For long months, many had waited for a final climatic showdown between the best Union general, and the best Confederate general. With Grant now on the field, sanguine expectations started to bloom again. Some Yankees had already had their hopes ground to dust due to the previous bloody failures. “What a difference between now and last year!” wrote a State Department clerk. “No signs of any enthusiasm, no flags; most of the best men gloomy and despairing.” Grant moving his headquarters to the field was nothing but a “cry of distress,” the New York World denounced. As General in-chief, the paper continued, he had already been “responsible for the terrible and unavailing loss of life” that resulted from a “campaign that promised to be triumphant” but had turned into “a national humiliation . . . a failure without hope of other issue than the success of the rebellion.” For their part, many rebels sneered that Grant “was no strategist and that he relied almost entirely upon the brute force of numbers for success.” His arrival would change nothing, one of Lee’s officers remarked, and Grant would “shortly come to grief if he attempts to repeat the tactics in Virginia which proved so successful in Mississippi.”

Lee too discounted Grant’s value. “His talent and strategy consists in accumulating overwhelming numbers,” he wrote to his son, and when asked who he thought was the best Union general he replied “Reynolds, by all odds”. Rebels and Copperheads agreed that Grant was nothing but a bumbling butcher, while Lee was the unquestionably superior general, refined both in military thinking and personal manners. But in truth, however they matched up tactically, Grant was superior as a strategist. “Lee had no real plan to end the war other than to prolong it and make the cost bloody enough that the North would weary of the effort,” explains Ron Chernow. “Grant, by contrast, had a comprehensive strategy for how to capture and defeat the southern army, putting a conclusive end to the contest.” Completely focused on Virginia and impressive battles, Lee couldn’t overcome Grant’s broader vision and farsighted campaigns. Sherman saw it clearly at the time, saying that “Grant’s strategy embraced a continent; Lee’s a small State.” In the last analysis, Lee was not overcome by superior numbers alone, but outgeneraled by superior strategy.

General Grant and his staff

Grant’s arrival injected new energy into the Army of the Susquehanna, where many soldiers had come to believe that if there was someone who could face Lee, it was Grant. “If it be true that Grant has never fought Lee,” the New York Times reminded its readers, “it is equally true that Lee has never met Grant.” Unlike many Eastern commanders, Grant was never cowed by Lee’s reputation, and his confidence in turn inspired his men. “Never since its organization had the Army of the Susquehanna been in better spirits, or more eager to meet the enemy,” commented a journalist; Rawlins agreed, and as he watched the men march with a “proud and elastic step” he asserted that the soldiers believed “they can whip Lee.” The Yankees’ morale was also raised by a visit from Abraham Lincoln, who despite the worries of Stanton and Mary Todd had decided to again travel to the headquarters of the Army. The fact that the President walked among them, with his head held high and completely unafraid, despite having suffered an assassination attempt just a couple months earlier, inspired admiration and resulted in enthusiastic shouts and cheers. Some of the loudest came from African American troops, who “cheered, laughed, cried, sang hymns of praise, and shouted . . . ‘God bless Master Lincoln!’ ‘The Lord save Father Abraham!’ ‘The day of jubilee is come, sure.’”

Grant had around 88,000 men to face Lee’s 41,000 rebels, plus the 10,000 troops garrisoning Richmond in four extensive lines of fortifications. Attacking Richmond’s defenses head-on would probably be unable to take the city, without a long siege after surely sustaining enormous casualties. Grant instead shifted towards Petersburg, hoping to take the logistical node that fed Richmond and Lee’s Army. Grant divided his force into two columns – one, under Sedgwick, would cross the James towards Petersburg, while the other under Grant himself would advance up the Peninsula and engage Lee in battle. Grant hoped that this way Lee would be too busy dealing with his half of the Army to check the other in its advance. This was a risky maneuver, for Lee would have equal numbers to Grant’s wing of the Army of the Susquehanna, but the alternative would have been more fruitless offensives. “The move had to be made,” Grant claimed later. On August 27th, the Army of the Susquehanna left Cold Harbor, the soldiers celebrating their “withdrawal from this awful place,” as a New Jersey soldier remembered. “No words can adequately describe the horrors of the days we had spent there, and the sufferings we had endured.”

The first skirmish took place on August 28th, when Union infantry under General Buford, supported by Bayard’s cavalry, arrived at Malvern Hill. Buford had told his men that “you will have to fight like the devil until supports arrive,” and indeed they had to, for the quick arrival of Confederate troops with the presence of Lee himself resulted in a sharp fight around Riddell’s Shop. Grant then arrived with reinforcements, but Lee contested the position for a little while longer before pulling back at night. Over the next hours Lee moved his Army to New Market Road, to block Grant’s route to Richmond. However, Lee did not mean to merely wait for Grant’s next attack, assaulting Grant’s position at Malvern Hill. Almost two years ago, an attack at the same position had broken McClellan’s lines even though the rebels were charging uphill against superior artillery. Lee was unable to repeat that feat, his attack on August 29th being repealed by “a raging storm of lead and iron,” unleashed by Yankee soldiers shouting “Remember Malvern Hill!” At least, Grant’s own swing towards Glendale also came to grief, the blue soldiers unable to overtake Lee’s trenches.

At the same time as this fight, Sedgwick managed to cross the James, arriving at it on August 29th. The city, unbeknownst to Sedgwick, was guarded only by hastily assembled militias of old men and young teens, one Confederate sardonically commenting that “the Petersburg trenches are a merry activity for grandfather and grandson.” From the outside, however, the defenses seemed way more formidable, making Sedgwick hesitate. This gave Richmond enough time to notice the threat, and Breckinridge in response “directed all organized Infantry and Cavalry to come forward” to Petersburg’s defenses. Lee was just as alarmed. The Confederate general surmised that Grant’s assault was the main effort, but Petersburg could not be given up. To reinforce that city, Lee sent Jackson there while he pulled closer to Richmond’s defenses. As soon as Lee pulled out, Grant pursued, showing all Confederates that he was unlike all the other Federals they had ever faced. “We must destroy this army of Grant's before he gets to the James River,” Lee told his commanders, his usual composure barely hiding his frustration. “If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere matter of time.”

The Second Battle of Malvern Hill

At Petersburg, after hours of reconnaissance, Sedgwick finally advanced. In truth, such preparations were not necessary, for the defenders were outnumbered five-to-one and the line collapsed, despite their desperate resistance, only three hours after the Yankees “swept like a tornado over the works.” When Jackson finally arrived, the situation seemed hopeless, but the fanatical rebel refused to give up even an inch to the “Yankee devils.” Jackson’s men went forward, in spite of their bleeding feet after the forced march, and managed to throw Sedgwick back, but the assault stalled. Although Jackson had stopped Sedgwick’s advance, now there was no line of defense between the Union and Petersburg, while Richmond’s trenches were unprepared and undermanned, certainly insufficient to resist an all-out assault by Grant. Breckinridge was scrambling frantically for enough men to defend all points under attack, but the manpower reserves were almost exhausted. “To-day I saw two conscripts from Western Virginia conducted to the cars (going to Lee’s army) in chains. It made a chill shoot through my breast,” wrote John Jones, reporting on the increasing pressure for manpower. “Old men, disabled soldiers, and ladies are to be relied on for clerical duty, nearly all others to take the field.”

Even if somehow more regiments could have been produced, Lee did not have the time to wait. The gray commander started to work on improving Richmond’s defenses, so that they could be held by a very small force, which would allow him then to move the bulk of his Army to Petersburg and defeat Sedgwick. However, Grant had his own plans. Meade may have been “corked” in his earlier campaign, but thanks to him the Union was in control of the Bermuda Hundred, separated from Grant’s position at Deep Bottom by the James. If Grant moved his Army there, he would be closer to Petersburg than Lee was, affording him an opportunity to overwhelm Jackson before Lee could react. On September 2nd, Grant started the move, ordering Sedgwick to attack Jackson’s hastily built trenches. The Federals marshalled for the assault, even as many grimly remembered that such frontal assaults had resulted in terrible losses in the past. A Yankee officer had to remind his men: “if any of you have anything to say to your folks, wives or sweethearts make your story . . . God only knows how many of us will ever come out of this damned fight.”

At the appointed hour, a rebel reported that “Yelling like mad men, came the Federal infantry, fast as they could run, straight onto our lines. The whole field was blue with them!” The most successful corps was Charles Griffin’s, his furious assault pushing Jackson’s center back. But this came at a cost, the fighting degenerating into a bloody, terrifying contest just as it had happened at North Anna and Cold Harbor. “Nothing can describe the confusion, the savage blood-curdling yells, the murderous faces, the awful curses, and the grisly horror of the melee,” wrote a veteran. “Impelled by a sort of frenzy,” the men jumped into the trenches, emptying their rifles and hurling them like spears, then being handed another fully loaded rifle by comrades to do it again until they were shot down. The firing was so intense that soldiers were reduced to “piles of jelly,” and an oak tree nearly two feet thick was cut down by the impact of thousands of minié balls. Those who survived the battle would always remember it as “Hell’s Half Acre.”

Grant had been unable to break Jackson’s lines, but he still had Doubleday’s USCT corps in reserve, which he pressed into battle in the face of Jackson’s resistance. Doubleday’s men were eager to face Jackson again, to show “the traitor Stonewall the valor of the colored troops” a second time. In this they were aided by an unexpected stroke of luck – Doubleday had ended further south than Grant intended because of several swamps and ravines that were not marked in his maps. Thanks to this, when Doubleday attacked, he found the weaker trenches right at the end of Jackson’s line, bend at an angle to try and shield the Army. This was, in fact, Jackson’s old division, the veterans of many fights who had been with him since his first days in Confederate service. That day, these final remnants were annihilated, Doubleday’s assault killing or capturing the great majority of the men, “thus finishing the work of Union Mills.” The offensive had, of course, extracted a heavy toll, to the point that the site would also acquire a nickname that spoke of the horrors seen there: the Bloody Angle. Jackson was forced to bend his army to try to form a new line to stop Doubleday’s advance, the Black soldiers chanting “revenge for Fort Pillow!” and “remember Union Mills!”

Hell's Half Acre

The pressure, however, was simply too much. Jackson’s center broke under Griffin’s assault while his right was unable to stop Doubleday. Yet, a large part of Jackson’s corps kept fighting “like a tiger at bay” for several hours, many afraid that Doubleday’s USCT would enact revenge for previous massacres by murdering them if they surrendered. “The darkies fought ferociously,” wrote Charles Francis Adams Jr. “If they murder prisoners, as I hear they did . . . they can hardly be blamed.” At the time, reports abounded that the Black soldiers had indeed executed several surrendering rebels. But most of these reports were produced in the South as propaganda meant to demonstrate the “savagery” of “Lincoln’s negro murderers.” In truth, there was no wholesale slaughter at the Bloody Angle – the Southern soldiers that surrendered were taken in as prisoners, and the high casualties were not a result of massacre but simply of the ferocity of the fight. Despite having “every reason to pay back the rebels,” as Northern editors acknowledged, the “colored troops behaved with mercy, and discipline.” “What a glorious, immortal example of humanity!” celebrated Henry McNeal Turner. “It was presumed that we would carry out a brutal warfare, but we have disappointed our malicious anticipators, by showing the world that higher sentiments not only prevail, but actually predominate.”

The situation was chaotic when General Lee finally arrived. Several rebels, in their haste to flee the bloody fight, went right pass Lee, ignoring his cries to “Hold on! Your comrades need your services. Shame on you!” “My God, has the army dissolved?” Lee finally asked. Grant had at last managed to do something no other Union commander had done: he had made Lee panic. However, Longstreet kept his cool head, driving into the fight. Longstreet’s men “fought like demons, pouring their rapid volleys into our confused ranks, and swelling the deafening din of battle with their demoniac shouts.” Yet more dreadful fighting ensued, with a horrified Horace Porter concluding that the “savage hand-to-hand fight was probably the most desperate engagement in the history of modern warfare.” Watching over a field “so covered with dead that it would have been possible to walk across the creek . . . stepping on dead bodies, without a foot touching the ground,” Grant retired to his tent at night and wept. There was mourning as well in the Confederate headquarters, with both Lee and Jackson struggling to remain stoic in the face of such great losses, including almost all of Jackson’s old division, the “men who had done so much fighting and who had made those wonderful marches.” The Stonewall Brigade had started the war with 6,000 men, of whom now only 200 remained.

The men rested, or tried to, during the next day, while Grant pondered his next move. He did not intend to “give Lee time to repair damages,” believing that he had pushed his enemy to the brink such that “to lose this battle they lose their cause.” With Lee determined to hold Petersburg, Grant planned to move to Richmond. The plan was bold, but if successful it would draw the Army of Northern Virginia into the open. Still, and despite its dreadful losses, Lee and his Army maintained their mystique over many Federals. Perhaps overwhelmed by exhaustion and anxiety, several officers fretted that they should retreat. But Grant would not accept any such talk. “I am heartily tired of hearing what Lee is going to do,” Grant snapped. “Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land on our rear and on both our flanks at the same time. Try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.” Grant thus managed to finally break the spell Lee had cast over the Army of the Susquehanna, showing the men that their commander was decidedly not afraid of Lee and imbuing them with confidence in victory. “Grant is moving to Richmond!” cheered many soldiers when they found that they would not retreat but continue the fight. “Men swung their hats and tossed up their arms in the flush of exhilaration,” wrote Porter.

When Lee’s scouts caught signs of movement, making an officer exclaim in relief that Grant was retreating, Lee replied “You are mistaken, quite mistaken. Grant is not retreating; he is not a retreating man.” Indeed, Grant was marching back to Deep Bottom, but on the way, he changed plans and decided that this would be merely a feint against Richmond, sending Gibbon’s corps back to Petersburg for the main attack. But surprisingly, Grant found little resistance in the road to Richmond’s first line of defense, getting close enough to shell the Confederate capital. At 4 am on September 5th, the citizens of Richmond were awoken by the Yankee artillery, resulting in mass panic. The surprise was such that Jefferson Davis took his pistols and horse and rode to the frontlines, apparently intending to repeal the invaders himself, while Breckinridge ordered all able-bodied males in the city rounded up and sent to the trenches. “The city is now being pressed by the enemy in a manner I have never before witnessed or expected,” General Samuel Copper wrote Lee.

The thrust to Richmond, which was meant to be merely a feint, had resulted in an unexpected success. The city’s defenses had been stripped bare, with Lee requesting the reinforcements in reaction to Grant’s apparently imminent second attack against Petersburg. “The result of any delay will be disaster,” Lee had stated forebodingly. Due to this, there were only young boys, old men, and invalid soldiers when the Yankees reached the exterior line, and they quickly surrendered. Both Lee and Grant rushed to the scene, realizing that Richmond was in imminent danger of falling. Only bombarding by the James River Squadron slowed the Yankees down. A ferocious attack against the intermediate line of defense almost broke them until Lee arrived, accompanied only by a small part of his Army, for the rest had fallen behind. But these veterans were still enough to reinvigorate the defenders and turn back the Yankee advance through a brave counterattack. Lee, “overcome with emotion,” asked which brigade this was. “The Texas brigade, sir,” someone responded. “Hurrah for Texas,” Lee cheered, waving his hat and so gripped by joy that he almost joined the attack himself until the soldiers shouted “Lee to the rear!” and made him come to his senses.

The Bloody Angle

Lee’s arrival was able to prevent a rout and stabilize the Confederate front. “His presence was an inspiration,” declared a rebel. “The retreating columns turned their faces bravely to the front once more, and the fresh divisions went forward under his eye with splendid spirit.” The Yankees were now paying dearly in blood for every attack, which was compounded by the sheer bone-deep fatigue they felt after days of brutal campaigning and marching. “It seemed to me as if I should drop down dead I was so tired,” wrote home a Connecticut Black soldier. Still, Grant was not about to throw away this golden opportunity to finally take Richmond, while Lee rallied his men desperately to try and throw the Federals out. The trenches became “a pool of blood, a sight which can never be shut from memory,” while a Union nurse said in anguish that “the lines [of] ambulances & the moans of the poor suffering men were too much for my nerves.” They were too much for the nerves of Gibbon’s corps as well, now composed mostly of conscripts after losing so many men in the past. Hearing the terrifying sounds of battle and seeing the ghastly consequences in the form of countless wounded and dead men, they panicked and refused to join the fight for hours.

By the time the corps was forcibly brought to the battlefield, the opportunity had passed. The Federals had withdrawn, conceding that they could not take the intermediate line just yet. But Lee also had to concede that he could not dislodge the Federals from the external lines, which meant they were just outside Richmond. More critically, the rest of the Union Army remained in Petersburg, which was only defended by Longstreet’s tired veterans after the movement of Jackson and Early to Richmond. Hoping that at least Petersburg could be taken, Grant ordered Sedgwick to attack it. “General, they are massing very heavily and will break this line, I am afraid,” Lee had warned Longstreet. But Longstreet calmly replied that “If you put every man now . . . to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line. Look to your left; you are in some danger there but not on my line.” Just as Longstreet promised, after days of building them up the defenses of Petersburg had been rendered so powerful that the charging bluecoats were “literally torn into atoms . . . with arms and legs knocked off, and some with their heads crushed in by the fatal fragments of exploding shells.” After this, Grant settled in for a siege.

Grant’s Overland Campaign, also known as the Grant’s Eight Days to Richmond, carried the heavy toll of 29,600 Union casualties. But unlike previous engagements, where the rebels sustained merely half the Federal losses, Lee this time lost 23,900 Confederates – a number not that inferior to Grant’s that becomes catastrophic once one remembers that Lee’s initial numbers were half of Grant’s. Though Grant had ultimately been unable to overcome the extremely strong rebel lines to take both Richmond and Petersburg, he had succeeded in his broader strategic plan. Now Lee was stretched thin, pinned in defending both cities, the famed mobility that had been integral to the past triumphs of his Army completely neutralized. While the high casualties Grant had incurred caused understandable grief, unlike previous campaigns it seemed he had accomplished something, being now at Richmond’s doorstep, his soldiers able to hear the city’s church bells. When Lee’s Army “at last was forced into Richmond it was a far different army from that which invaded Maryland and Pennsylvania,” explained Grant. “It was no longer an invading army.”

Grant had thus accomplished the position Lee most feared – a siege Lee could not break from, rendering it “a mere question of time.” Lincoln recognized this, celebrating that “Grant is this evening . . . in a position from whence he will never be dislodged until Richmond is taken.” “The great thing about Grant,” the President continued, “is his perfect coolness and persistency of purpose . . . he is not easily excited . . . and he has the grit of a bull-dog! Once let him get his ‘teeth’ in, and nothing can shake him off.” The men too had concluded that the end was in sight, like Elisha Hunt Rhodes who wrote that “General Grant means to hold on, and I know he will win in the end.” Newspapers that had once been gloomy, suddenly adopted a sanguine tone, publishing headlines like “Glorious news, Immense rebel loses!” and “LIBERTY – UNION – PEACE – Lee’s Army as an effective force has practically ceased to exist.” The Black published Christian Recorder for its part exulted how Black troops had been “instrumental in liberating some of our brethren and sisters from the accursed yoke of human bondage. . . . What a glorious prospect it is, to behold this grand army of black men, as they march with martial step at the head of their column, over the sacred soil of Virginia.”

A restless and grim Grant during the Overland Campaign

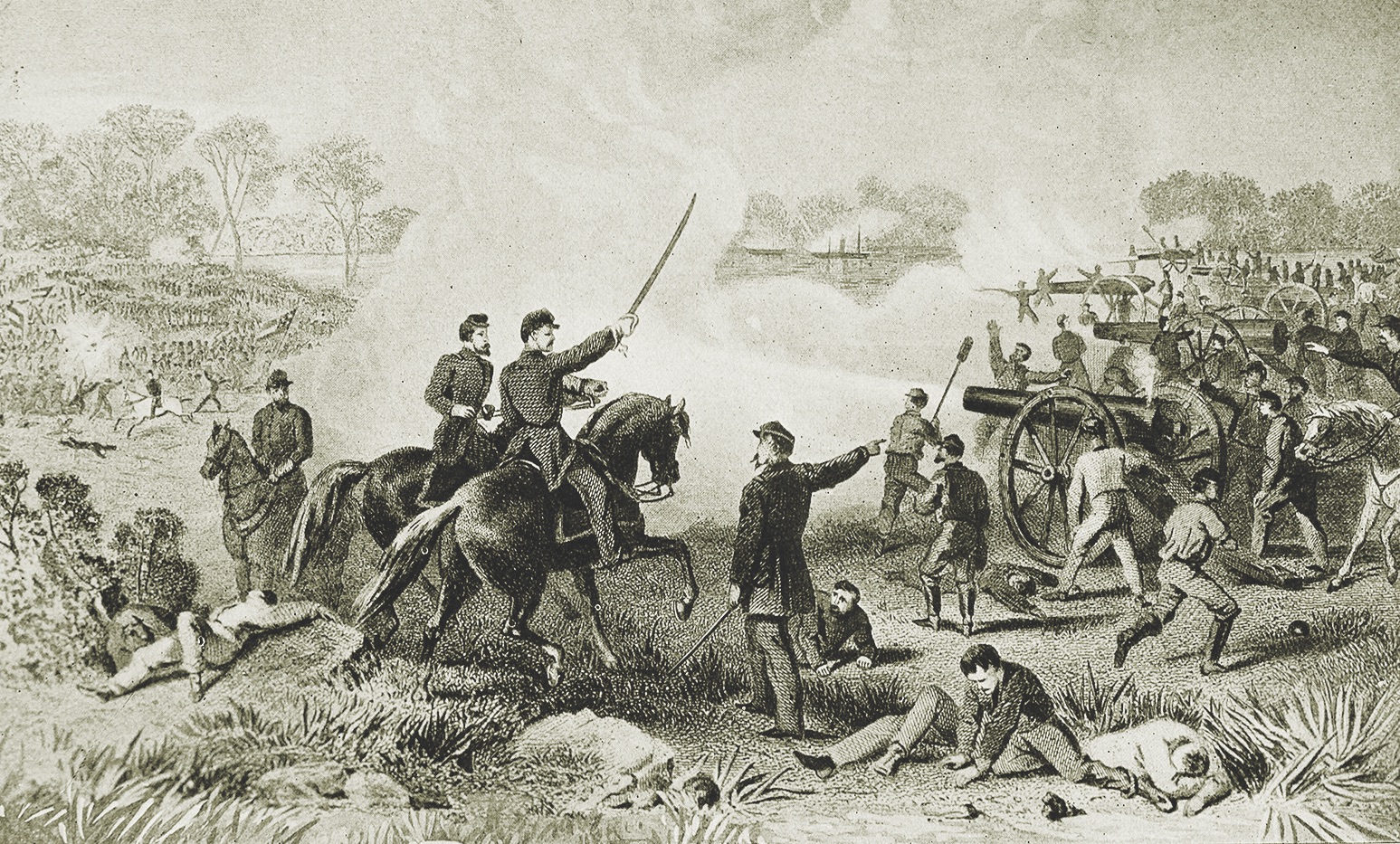

These celebrations were rather a result of the revived optimism due to the latest victories, the first of them at Atlanta. There, Thomas’ siege had pushed Confederate resources to the breaking point, forcing Breckinridge to expedite several decrees that, in desperation, allowed for widespread impressment of goods and enslaved laborers. The grave political consequences of these decrees must be examined later; suffice it to say that despite them, Atlanta remained in a critical position, unable to resist much longer. Thomas, consequently, would have to be defeated by Southern boldness. Cheatham’s decision to go on the attack was controversial, but then and now many have insisted that Thomas’ and Sherman’s successful maneuvering left the rebels with no other option. It was either to save Atlanta right there and then, and open the possibility of saving Mobile from Sherman, or wait impotently as both were subjugated. Moreover, if Mobile fell first Sherman would be free to plunder Georgia or attack Cheatham from the rear. Thus, attacking, although risky, came to be seen as the only possibility, especially after the arrival of Cleburne brought the Confederates to near parity with the Yankees. Despite their misgivings, Cheatham and Breckinridge approved the offensive and began its execution on August 18th.

Naturally, Hood would spearhead the attack at the head of 15,000 rebels. Tall and bearded, John Bell Hood was born in Kentucky, before being shipped off to West Point. His performance was rather mediocre, graduating 44th in a class of 52, where George H. Thomas was his artillery instructor. Foreshadowing Hood’s reckless personality was the fact that he accumulated 196 demerits, just 4 below the 200 that would have resulted in an expulsion. Young and aggressive, Hood proved himself as one of Lee’s hardest fighters, losing a leg during the Battle of Union Mills. He then spent the following months learning to ride his horse with a prosthetic leg, joining both Breckinridge and Davis often during the rides the two enjoyed as their only form of relaxation. This may have earned their esteem, and after Longstreet left the Army of Tennessee, Hood remained there and was ascended to corps commander following Polk’s death.

Some saw this aggressiveness as a virtue, but others weren’t so sure. When Breckinridge was looking for generals to replace Johnston, he had asked Lee for his opinion, to which he replied that “Hood is a bold fighter. I am doubtful as to the other qualities necessary.” But he also believed that Hood was too reckless, sentencing him as “all lion, none of the fox,” and urged for Cheatham to be appointed instead of him. This swayed Breckinridge, but the apparent failure of Cheatham’s strategy, with Thomas now at the gates of Atlanta, made the President consider Hood once more. With the benefit of hindsight, Sherman would later comment that Breckinridge “rendered us a most valuable service” by approving Hood’s plan. “This was just what Thomas needed,” Sherman elaborated, “to fight on open ground . . . instead of being forced to run up against prepared intrenchments.” Even at the time some questioned the wisdom of Hood’s plan. Cheatham, who considered Hood a boastful schemer, apparently only agreed because he feared he would be removed if he refused, and Cleburne remarked that “We are going to carry the war into Africa, but I fear we will not be as successful as Scipio was.”

The Southern soldiers began their march with high spirits, buoyed by the idea of finally striking back against the Yankees after months of retreats and siege. “Strap in. Things are going to change!” proclaimed Hood, as he and his soldiers crossed the Chattahoochee at Palmetto. Small Union garrisons at Big Shanty and Acworth were quickly overwhelmed. Hood did little to cover his advance, the skirmishes resulting in “dense columns of smoke” that Thomas was able to see from his headquarters. The garrison at Marietta then fell too when rebel shells exploded the large ammunition magazine. This meant that Hood would not be able to seize it for his own use, but he apparently was more concerned with mounting up a spectacle, his men applauding the large explosion. Jubilant shouts also resounded in Atlanta, where the rest of the Army of Tennessee let out the “pent-up cheers of men who were wearied with long waiting and patient watching.” Besides being a welcome release of tensions, a sign that the Confederate Army was finally going to fight, these celebrations seemed justified by the fact that Thomas pulled back from his siege lines to chase Hood – just as the rebel commanders had planned.

Hood leading his troops forward

Thomas’ decision was due to the simple fact that he couldn’t allow Hood to run amok on his rear. If Hood succeeded in cutting off his supply lines, then the whole campaign could be extended for yet more weeks – time the Union could not afford. Moreover, Thomas was more interested in destroying the enemy Army. Hood’s maneuver was enormously risky, and if caught the lost could be insurmountable. Bad enough, indeed, to force Cheatham to give up Atlanta. In Philadelphia, Grant concurred, wiring that this was an opportunity to “annihilate [Hood] in the open field.” Nonetheless, to preserve the position for which he had fought hard for the last months, Thomas left Negley’s corps in a fortified bridgehead south of the Chattahoochee. Cheatham and Cleburne, who had rushed forward to try and trap Thomas while he crossed the river, found Negley’s defenses to be too formidable. For the moment, the rebel forces would remain separate and thus unable to close the trap.

In the meantime, Hood had reached the Union supply depot at Allatoona, filled with a million pounds of rations, and demanded its surrender. Although they were outnumbered five-to-one, the Union troops defiantly declared they would die first rather than surrender. Thomas also signaled that he would soon arrive. After constating the steely courage of his men, the Federal commander challenged Hood with a short message: “I believe I can hold my post . . . If you want it come and take it.” Hungry for victory and beef, the rebels came “like a wintry blast from the north,” but were met with strong resistance. The Southerners had to acknowledge that the garrison “fought like men,” but the Yankees’ numerical inferiority and lack of ammunition was making the prospects of victory increasingly bleak. Some soldiers had to resort to throwing rocks. Only the hope that Thomas would soon arrive kept them going. “The same unuttered prayer hung on every parched, powder blackened lip,” wrote an officer. “‘Oh! That Thomas or night would come!’”

Thomas arrived first. Conscious that being trapped between Thomas and the fortresses would spell a disastrous end for the campaign, Hood reluctantly pulled back. Even though Hood had lost 3,500 men to a paltry 1,100 Union casualties, a more than three-to-one ratio that the Confederacy could ill afford, his gamble seemed to have paid off. Cheatham and Cleburne had moved around Negley, with Cheatham retaking Marietta while Cleburne trapped Negley “deep in rebeldom.” The situation seemed nothing short of catastrophic for the Union, with a quarter of the Army of the Cumberland under siege and Thomas was back in his June position. This news, arriving just a few days after Copperheads had declared the war a failure, caused widespread panic in the North. “We’re lost, humiliated, defeated, doomed, dishonored…” went a typical editorial. “The list of adjectives that describe our present disgraces is unending.” Rebels celebrated joyously. The elated John B. Jones predicted that “the effects of this great victory will be electrical. The whole South will be filled again with patriotic fervor, and in the North there will be a corresponding depression. . . . Surely the Government of the United States must now see the impossibility of subjugating the Southern people.” An alarmed Grant went as far as considering sacking Thomas, because although “There is no better man to repel an attack than Thomas,” Grant feared that “he is too cautious to ever take the initiative.”

However, in that moment of truth, Thomas proved Grant and all other naysayers wrong. He and Sheridan would pursue Hood, while Palmer and Burnside would defend Allatoona against Cheatham. As Hood advanced, he destroyed miles of track, but was unable to force the small Union garrisons to surrender, all of them putting up stout resistance that Hood did not have the time to overcome, unless he wanted the pursuing bluejackets to catch up. Hood resorted to living off the land – a dangerous prospect given that he was operating on Confederate territory, meaning that the supplies he seized came from the civilians his Army was meant to protect. Hood justified it under Breckinridge’s emergency decrees, but this did little to contain the fury of farmers who saw almost the entirety of their produce and cattle impressed by unruly soldiers who “steal and plunder indiscriminately regardless of sex,” as one Confederate private admitted in shame. Wheeler’s cavalry was especially undisciplined, acting with such “destructive lawlessness” that they became known as “Wheeler’s robbers,” and were denounced by Robert Toombs as being nothing but “a plundering, marauding band of cowardly robbers.”

Joseph Wheeler

Deciding that fighting Thomas head-on under such conditions was unrealistic, Hood changed plans, and somehow arrived at an even more ludicrous strategy. He would capture Chattanooga, march on Nashville, and then move on to Kentucky. The Bluegrass State, “groaning under the bloody oppression of a fanatical host,” surely would have come to its senses following the latest events and would give Hood at least 15,000 men. This even though Bragg got hardly half that amount during his previous invasion. Only then would Hood turn around to destroy Thomas, and afterwards, Hood fantasized, he would march through West Virginia towards Richmond to “defeat Grant in conjunction and allow Lee in command of our combined armies to march upon Philadelphia.” Implausible as the plan might have been, Hood’s march still was seen as enormously threatening, especially because it coincided with another raid into Tennessee by Forrest. For once the rebel forces had been capable of coordinating their efforts, and with Forrest drawing most of the troops away, Hood found merely 7,000 “inexperienced negroes, new conscripts, convalescents and bounty jumpers,” defending the ridges of Ringgold Gap.

As Hood’s soldiers advanced, suddenly, blue troops appeared and fired at them from close range. “By Jove, boys, it killed them all!” cried one Arkansan. But Hood would not give up. He had made his Texans fight in Virginia; he was determined to make his troops fight in Georgia. And so, he rallied the men and ordered them to assault the heavily fortified, Federals, who resisted charge after charge at the high price of 2,000 casualties, out of the initial 7,000 soldiers. But Thomas would not give, “standing like a rock,” while he waited for Sheridan to arrive. Normally a perfect example of near emotionless stoicism, Thomas kept watching the horizon with his field glass and fussed with his beard. Then, “the sun burst through the heavy clouds and shone full in the faces of 10,000 cavalry . . . banners flying, bands playing and the command marching in as perfect lines as if on a parade.” Cheers resounded in Thomas’ headquarters, several officers forgetting themselves and throwing hats into the air. Observing the “magnificently grand and imposing” parade, an officer declared poetically that “heart of the patriot might easily draw from it the happy presage of the coming glorious victory.” Uncharacteristically, Thomas’ response was less eloquent but fuller with emotion: “Dang it to hell, didn't I tell you we could lick 'em, didn't I tell you we could lick 'em?”

The Yankees indeed licked Hood that day. Sheridan’s arrival surprised the impetuous rebel, whose single-minded focus on attacking the enemy on his front allowed Sheridan to hit him on the flank and rear. Half of Hood’s force was outright destroyed, while the other half virtually melted away as Hood tried desperately to retreat while pursued by the dogged Sheridan. A Confederate was not exaggerating when he called it an “irretrievable disaster” – and more of them would come soon. Without losing time, Thomas has reunited with Palmer and Burnside, who had held the rebel armies back. The news of Hood’s failure had inspired the Yankees, while “a gloomy terrible feeling” took over many Southrons. But Cheatham still had a last card up his sleeve – if Negley could be forced to surrender, he could inflict a similar loss on the Army of the Cumberland, with Thomas still being driven to a position farther away from Atlanta. It would still be a victory; one bought at a very steep cost, to be sure, but a victory nonetheless.

Prepared to rescue Negley’s corps, which had been reduced to half-rations, all of Thomas force gathered for a mighty push against the rebels, who had retreated to the more formidable position at Kennesaw Mountain. Thomas sent in skirmishers to try and find a weak spot on Cheatham’s line, but General Burnside had other ideas. Never one for subtle maneuvering, Burnside decided instead to assault the Confederate position head-on. Under orthodox military theory, Burnside’s assault ought to have been suicidal. Upon seeing it through his spyglass, the bluecoats ascending the slopes while on the background the “Kennesaw smoked and blazed with fire, a volcano as grand as Etna,” Thomas immediately rode to Burnside’s position, fearing that this was but the beginning of a disaster. His fears were seemingly confirmed when he saw a great mass of men descending, but upon closer inspection these turned out to be wearing the gray. “General, those are rebel prisoners, you see,” confirmed Burnside with a smile.

Against all military logic, Burnside’s direct assault had produced a complete collapse of the Confederate position, sending the defenders fleeing in panic and allowing the Union to take the Kennesaw Mountain. The sudden collapse of the rebel line was owed to the fact that, in their haste to fortify the position, the Confederate engineers had misplaced their artillery, which overshot the charging Yankees. Unable to stop the assault, the thinly manned rebel lines broke easily. Both Federals and Confederates could scarcely believe the scene. “Completely and frantically drunk with excitement,” the Union army, a Yankee soldier reported, “was changed into a mob, and the whole structure of the rebellion . . . was utterly overthrown.” A Tennessee soldier for his part wrote that “the whole army had caught the infection, had broken, and were running in every direction. Such a scene I never saw,” while a Southern officer said in mortification that “no satisfactory excuse can possibly be given for the shameful conduct of our troops. . . . The position was one which ought to have been held by a line of skirmishers.”

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

The rebels ran all the way back to Atlanta, forcing Cleburne to retreat as well. The “sullen, sad, and downcast” mood of Cheatham’s men caused a dark foreboding within Cleburne’s troops, who observed how these veterans seemed convinced “that there was not a ray of hope for the success of their cause and they were willing to quit and go home.” Indeed, several soldiers threw their muskets aside as soon as they reached Atlanta and deserted, with a man glumly declaring that “if we canot hold as good a place as the Kinesaw, we had as well quit.” While Cleburne was willing to fight for Atlanta, believing that at the very least retreating without resistance would be even worse than losing the city, Cheatham vacillated and seemed unable to muster up the necessary leadership. Rumors said Cheatham ended up appealing to the bottle, with a private finding “Old Frank as limp and helpless as a bag of meal.” As a result, there was no preparation, only chaos and confusion within the rebel ranks as Thomas approached.

Finally, Cheatham decided to retreat, ordering everything of value that could not be evacuated set ablaze, including 81 cars of ammunition, which resulted in a series of explosions that “shook the ground and shattered the windows,” while settling much of Atlanta in fire. Terrifying scenes of anarchy followed, as citizens tried desperately to flee the city at the same time as motley crews of soldiers and “citizen guards” tried to hold off the Yankees by means of bloody urban fighting. Others simply seized their chance to loot, many people being murdered to seize their horses and carriages. “This was a day of terror and a night of dread,” wrote the merchant Sam Richards. Not until September 3rd were the Federals able to put off most of the fires and force the last defenders of Atlanta to flee. As the bluecoats marched in, being received by joyous freedmen who hailed their liberators, the fact that they had at last taken Atlanta set in and produced a cathartic outpour of relief. James A. Connolly, for example, wrote home that he could have “laid down on that blood stained grass, amid the dying and the dead and wept with excess of joy.” Amongst the still smoking buildings and homes, Thomas telegraphed the War Department that “the enemy has yielded Atlanta to our arms. The city is ours.”

The news of Atlanta’s fall had great consequences, but the most immediate were in Mobile, where the troops under General Maury were tenaciously trying to resist Sherman’s siege. Despite the hasty conscription of civilians to swell his forces, Maury still had merely 10,000 men, a number that was dwarfed by Sherman’s troops. History seemed to repeat, as the besieged soldiers, some of them veterans of the siege of Port Hudson, resisted only because they trusted that Cleburne would rescue them soon – that, unlike Albert Sydney Johnston, he would actually come through and return to save them. An impatient Sherman, wishing to cut loose in order to march through Georgia, had ordered to “destroy Mobile and make it a desolation,” but the bombardment failed to dislodge Maury. However, on September 5th Maury and his men received a blow more powerful still than the Yankee artillery: the news that Atlanta had fallen, with Cleburne retreating to the Georgia interior. Alongside the news came Sherman’s ultimatum, to either surrender or he would deal Mobile the “harshest measure, and shall make little effort to restrain my Army, burning to avenge a National wrong they attach to Mobile.”

At first Maury and his officers believed that Sherman was lying, and then that Cleburne, now not pinned in defending Atlanta, would at least come to prevent Mobile’s fall. But on the night of September 9th a scout, “with a face that barely restrained his grim tears,” managed to cross the lines and inform Maury that no help would be coming – they were alone. On September 10th, Maury surrendered the city to Sherman, who immediately sent a telegraph to Philadelphia informing his government that “Mobile is ours and fairly won.” By that time, Sherman had decided that the next phase of the war would be a march through Georgia, to devastate that state in the same way he had devastated Alabama. But before he started, he cleaned up the last Confederate holdouts in his rear. On September 20th, Sherman seized Montgomery with almost no opposition, and organized a great parade, celebrating the fall of both Atlanta and Mobile. Union soldiers, accompanied by Unionists Black and White, marched before the first Confederate Capitol with raised flags and triumphal shouts. “Three years ago, I saw the birth of the Confederacy here,” wrote a man in quiet desperation. “Now I am seeing its death.”

The Fall of Atlanta