this is going to have a lot of trouble if he repeats some of the things he did otl with african ameircans like leaving every single one of them behind in Georgia and cutting them off exc he could mean the out cry could mean the union lose one of there best commandersSherman had spent years in military postings in the Deep South; in 1859 (IIRC) Sherman was very much pro slavery, believing that African-Americans “in the great numbers that exist here must of necessity be slaves.” The main reason he sided with the Union was his hatred of traitors and fear of anarchy (secession).

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"this is going to have a lot of trouble if he repeats some of the things he did otl with african ameircans like leaving every single one of them behind in Georgia and cutting them off exc he could mean the out cry could mean the union lose one of there best commanders

Maybe he could be convinced to bring the African-Americans with him out of a fear of anarchy or maybe seeing them fight will make realize that they are better men than the treasonous South which in turn could have him re-evaluate his looks.

People aren’t set in stone after all. “The Reds!” for example had old “Blood and Guts” Patton be broken by the brutality of war

Chapter 9: Hurrah for the choice of the Nation

Chapter 9: Hurrah for the choice of the Nation

The ambient at Charleston during the Democratic National Convention of 1860 can only de described as feverish. The city was indeed under a grave fever, a fever of secession provoked by fear and paranoia. The tired and heartsick Yankees that arrived there to try and mend the divide met hostility, feeling themselves strangers in a strange land. The target of most hate was Stephen A. Douglas, a traitor who had cleaved the Democratic Party in two according to many of the Southern Democrats who met that fateful day.

The decision to come to Charleston hadn’t been easy for Douglas. The Southern Democrats hated him as much as they hated Seward or Sumner, and more than they hated moderates such as Lincoln. Their main goal had been destroying Douglas. They were joined by some pro-administration Northern Democrats who had cast their lot with President Buchanan and the South. Douglas’ attempt at creating another party had failed: his National Union lost dozens of seats to the Republicans. Douglas himself had been vanquished by Lincoln, losing his Senate seat and with it a major part of his influence in the government and his clout within the Party. It was painfully clear that the Southern Democrats had succeeded in their avowed objective to make him perish and hang his “rotten political corpse”. Douglas’ presidential ambitions were all but dead.

But Douglas refused to yield. He knew that no candidate put forth by the Southern Democrats would be able to gather any kind of support from the North. If the choice was between a Republican and a Southern Democrat, even the most moderate and conservative Northerners would cast their vote for the Republican. The prospects of other candidates were similarly bleak. Some Southern Whigs who still didn’t feel comfortable allying with either faction grouped together in the Constitutional Union Party, a sort of reincarnation of the old Whig Party. But the Constitutional Unionists, who nominated wealthy slaveholder John Bell from Tennessee, felt compelled to stump as enthusiastically for Southern rights as the Democrats, which further pushed Conservative Northern Whigs into the Republican fold. Consequently, the odds of Bell winning anything but Border States were low; if Douglas and his National Union made a run their odds of taking any Southern state were unfavorable. Either way, the Republican candidate didn’t need the Border South or the South itself. A solid North was enough to carry them to victory.

In Douglas’ eyes the best Democratic option was mending their differences and running a fusion ticket which could sweep the South, the Border states and perhaps take a couple of Lower North states. If they managed to keep the Republicans from a majority in the electoral college the election would go to the House, where every state had a vote. There a conservative coalition could take the Presidency.

But Douglas’ prospects were hopeless. The Party refused to even let Douglas attend. The crafty former Senator had organized rival delegations formed of Southern moderates and the surviving Northern Democrats, but the South instead admitted Southern delegations made of Fire Eaters and Northern ones made of pro-administration men. The National Convention quickly passed a plank pledging to grant federal protection to slavery in all territories, while spurning any and all attempts by Douglas and his supporters to create a fusion ticket.

Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi presented the substance of the South’s demands, which were for Douglas to support their chosen candidate, John Breckinridge, and the slave code. This was to much for Douglas and his men to swallow, for it would constitute an unconditional surrender to Southern domination of the party, and the country. His attempts to reason with the Southerners and to find common ground or compromise failed. And finally, after six weeks of being ignored and vilified, Douglas decided to give up trying to reunite the party. William L. Yancey, the overzealous Fire Eater, led a group of people into giving cheers “For an independent Southern Republic!” while Douglas and his men left Charleston. Yancey’s parting words surely resonated in Douglas’ ears as he left the harbor: "Perhaps even now, the pen of the historian is nibbled to write the story of a new revolution.”

John Breckinridge

Douglas had lost, but he hadn’t been defeated. Decided to do all he could to prevent the election of a Black Republican and the start of a Civil War, Douglas organized a National Union Convention which quickly nominated him. But unlike him, many had been defeated. The National Union Convention and its efforts were feeble and half-hearted, many tired delegated having resigned themselves to their fate. In this they contrasted with the energy and enthusiasm that dominated the Republican National Convention.

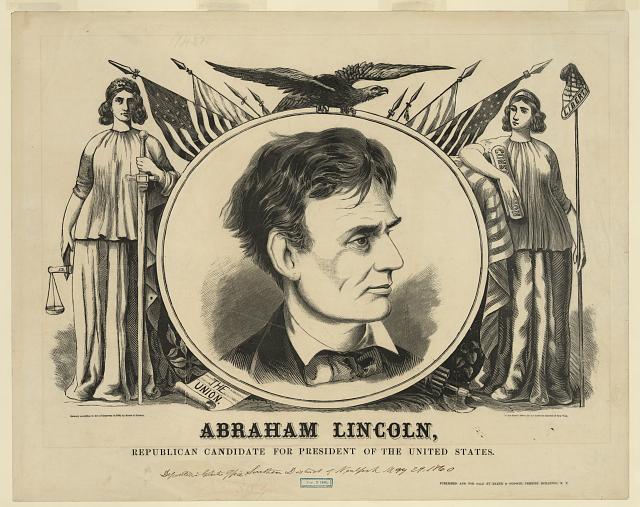

Meeting in Chicago, the Republican National Convention was characterized by adroit action and theretofore unseen popular enthusiasm. The favorite for the nomination was William H. Seward. A prominent Republican, leader in the east and an important player in the Senate for many years, Seward seemed like the natural choice for the Party. But many powerful men and interests weren’t convinced that he was the best choice. The Party needed to carry a Solid North to win, and contrary to the opinions of the South, the North was not entirely united in its opposition to slavery. Large segments of the north did not care, or, led by racism and prejudice, even supported it to an extent.

The Republicans just needed to add Pennsylvania to the states they won in 1856 in order to win. But Seward was seen as a radical, and he alienated nativists. Furthermore, he had made numerous enemies such as Horace Greeley, and his political machine in New York was seen as a shady and corrupt organization. Though Seward remained strong in the Upper North, any Republican would be able to easily sweep the region. Pragmatists and his enemies united and denied him his coveted first-ballot nomination. They then turned to find another candidate among a trio of favorite sons from different states: Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and Abraham Lincoln of Illinois.

Some other Republicans had tried to get the nomination, the most prominent of them being Edward Bates of Missouri, who commanded the support of the Blairs, a political family active in Maryland and Missouri. But Bates and the Blairs had been pushed towards the fringe corners of the party, being some of the most conservative Republicans out there. They championed a strategy of building up the party in the Border South by taking in people who had lukewarm commitment to slavery. But this strategy lost ground as the Slavocrats became brasher and bolder. Instead, most Republicans favored a strategy of action from the top, crystalized in the Freedom National doctrine that turned the Federal Government into a weapon to assail slavery wherever it existed.

Chase had many of Seward’s weaknesses and didn’t carry the same level of support; Cameron had a bad reputation as a flip-flopper who had been a Democrat, a Know-Nothing and a Whig. Lincoln, on the other hand, was a successful and respected moderate. Honest Abe had a reputation for moderation, compromise and respect, but he was also a shrewd politician who had built up a political machine in Illinois, a state the Republicans needed to win in 1860. He embodied ideals of integrity and hard-work, with Republicans being able to tout his raise from a humble rail-splitter to a prairie lawyer to one of the nation’s most prominent Senators as a living proof of the superiority of free labor and the promise of the American dream. His debates with Stephen A. Douglas in both 1856 and 1858 were legendary by then. And he had vanquished the feared Democratic leader.

Salmon P. Chase

Lincoln had always considered himself a party man. When he was just a Whig state legislator in Illinois, he dreamed of creating a party machine that would elect Whigs to all offices, from the Senate and the Governorship to local officials. After being elected to the Senate, he worked tirelessly to make that dream a political reality, and he had succeeded. His state was also his most fervent supporter. Many clamored for him to run for president, and although Lincoln did position himself for a run by touring the West and building bridges with constituencies the Republicans needed such as nativists and moderates, he also wrote this to a newspaper: “I must, in candor, say I do not think myself fit for the Presidency.” Similarly, he stated that he would prefer to have another term in the Senate rather than one in the White House. But his opinions started to change after his stunning victory in 1858 against Douglas.

Despite the fact that Douglas was an Illinois Yankee born in Vermont, he was seen as a living symbol of the Slave Power’s grip in National Politics and the North more specifically. As leader of the Northern Democrats, he was a prime target for Republicans. And at the end Lincoln was the David who slew the Little Giant, thus building a national reputation as a powerful and able statesman. Douglas’ attacks and his appeals to racism had failed. Lincoln still recommended focusing in slavery as an institution that had to be contained instead of focusing on its immediate abolition. But after 1858 he took a decidedly more radical turn, also talking of social issues and the future of black people. His speeches still exhibited customary moderation, with Lincoln reiterating that he opposed miscegenation and black suffrage, but like in his debates against Douglas he talked of unalienable rights that black should and must also enjoy. Lincoln also focused on uniting the Republican Party behind a single objective: putting slavery on the road to extinction. And he was remarkably good at reconciling different factions of the Party.

His speech at the Cooper Institute, in New York, was a mark of this. There he assured his audience of his command of the slavery question, his viability as a candidate, and his credentials as a Republican. The Senator attacked the South for trying to “destroy the government unless it prevailed in all points of dispute”, and also singled Buchanan and Chief Justice Taney for attacks. He repeated that he wouldn’t interfere with slavery where it already existed, but also called for Republicans to stand firm and continue steady in the face of threats of secession. He concluded with the following statement: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.” This speech and others gained him favor with Easterners who rejected Seward, and he already had the support of Midwesterners, who believed their turn had come.

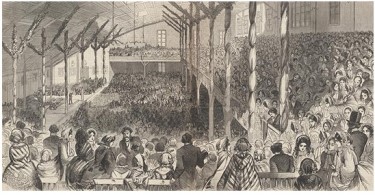

The 1860 Republican National Convention

Enthusiastic supporters lined the “Wigwarn” while the votes of the first ballot were tallied. Seward achieved 153 votes; Lincoln had 136. Neither had the required 233. Lincoln’s team of capable politicos worked tirelessly to gain second ballot support for their candidate. Because many believed that Lincoln could be elected while Seward could not, Lincoln was able to get the support of many delegations who chose him as their second option after their preferred candidates failed or after symbolic gestures to one politician or another. As the votes of the second ballot were counted, the Wigwarn lit with great energy that gave "the appearance of irresistible momentum". Finally, the results came: Lincoln had 239 ½ votes. The convention exploded with enthusiastic furor, the yells, cheering and music overwhelming. No one would ever forget that day, where they had chosen not only the best candidate for the election, but also "the best man for the grim task" ahead of them. “Let the new Revolution begin”, wrote Charles Francis Adams in the wake of Lincoln’s nomination. And indeed, the campaign season of 1860 would mark a new era in American politics and history. With Lincoln’s nomination, the Revolution of 1860 began.

Last edited:

Admiral Halsey

Banned

You know given how Buchanan is gonna let the South just take almost the entire Federal Arsenal might be tried for treason post-war?

I feel sorry for the union generals who came from the south, they were hated by them after the war (didn't one of the generals families refuse to speak or take money from him?) Know a even more radical war will see them hated more.

There is one positive however the good southerners have all the reason and support to fix and create a better south now.

There is one positive however the good southerners have all the reason and support to fix and create a better south now.

The South could secede even earlier now. Maybe some upper South States before the inauguration.

If Douglas doesn't die, and it's possible he won't since he got sick after that summer of 1861 trying to feverishly work to preserve the Union, I wonder if he can rehabilitate himself a little by taking a military position fighting for the Union.

If Douglas doesn't die, and it's possible he won't since he got sick after that summer of 1861 trying to feverishly work to preserve the Union, I wonder if he can rehabilitate himself a little by taking a military position fighting for the Union.

I feel sorry for the union generals who came from the south, they were hated by them after the war (didn't one of the generals families refuse to speak or take money from him?) Know a even more radical war will see them hated more.

George H Thomas, a Virginian who stuck with the union, was pretty conclusively disowned IIRC.

Cryostorm

Monthly Donor

The South could secede even earlier now. Maybe some upper South States before the inauguration.

If Douglas doesn't die, and it's possible he won't since he got sick after that summer of 1861 trying to feverishly work to preserve the Union, I wonder if he can rehabilitate himself a little by taking a military position fighting for the Union.

George H Thomas, a Virginian who stuck with the union, was pretty conclusively disowned IIRC.

As was Admiral David Farragut, not bad company for a man like Douglas who did everything in his power to save the Union and I can see him deciding to serve, though probably in the Western Theater.

I always felt bad for him but I feel even more bad for him nowI am starting to feel bad for Douglas.

Lincoln vs Breckenridge. I can't wait.

What do you mean that Douglas is in this as well?

What do you mean that Douglas is in this as well?

Who did Lincoln select for VP

The fact that the Dems selected the Southerner rather than the breakaway Dems did so means the party will go extinct after the Civil War... most likely

The fact that the Dems selected the Southerner rather than the breakaway Dems did so means the party will go extinct after the Civil War... most likely

I actually wonder if Breckinridge would get the nomination in this timeline.

In truth, he was more moderate than people might credit - more of an heir of Henry Clay (he inherited much of his machine and support) than a fire-eater. (William C. Davis's work on Breckinridge is worth reading in this regard.)

Southern Democrats OTL actually chose Breckinridge to grow their appeal in the border states precisely because of that background. And of course he was the sitting vice president, which gave him additional cachet.

Here, he's not the Veep, and the fire eaters are eating a lot more fire. Jefferson Davis and Robert Hunter might get a harder look here.

In truth, he was more moderate than people might credit - more of an heir of Henry Clay (he inherited much of his machine and support) than a fire-eater. (William C. Davis's work on Breckinridge is worth reading in this regard.)

Southern Democrats OTL actually chose Breckinridge to grow their appeal in the border states precisely because of that background. And of course he was the sitting vice president, which gave him additional cachet.

Here, he's not the Veep, and the fire eaters are eating a lot more fire. Jefferson Davis and Robert Hunter might get a harder look here.

Last edited:

has Buchanan become a southern radical too? Because if so he will defiantly try to swing the election to south/ poor Douglas his story is even more tragic in this timeline

Buchanan is definitely pro-Southern, and he's still corrupt, but if we can say anything good about him is that he followed the Constitution as he interpreted it. He probably wouldn't try to swing the election by means of fraud.

Douglas' story is tragic indeed. I'm contemplating letting him live for some years more, or at least until he sees the Union win with his own eyes.

You know given how Buchanan is gonna let the South just take almost the entire Federal Arsenal might be tried for treason post-war?

A more radical Lincoln may well try Jeff Davis et al for treason, but to try the former president for treason would be a tad too far.

I feel sorry for the union generals who came from the south, they were hated by them after the war (didn't one of the generals families refuse to speak or take money from him?) Know a even more radical war will see them hated more.

There is one positive however the good southerners have all the reason and support to fix and create a better south now.

It's really tragic that so many families and friendships were broken by the war. One of my favorite passages of The Battle Cry of Freedom describes this:

"Four grandsons of Henry Clay fought for the Confederacy and three others for the Union. One of Senator John J . Crittenden's sons became a general in the Union army and the other a general in the Confederate army. The Kentucky-born wife of the president of the United States had four brothers and three brothers in-law fighting for the South—one of them a captain killed at Baton Rouge and another a general killed at Chickamauga. Kentucky regiments fought each other on several battlefields; in the battle of Atlanta, a Kentucky Breckinridge fighting for the Yankees captured his rebel brother."

The South could secede even earlier now. Maybe some upper South States before the inauguration.

If Douglas doesn't die, and it's possible he won't since he got sick after that summer of 1861 trying to feverishly work to preserve the Union, I wonder if he can rehabilitate himself a little by taking a military position fighting for the Union.

Or perhaps a political one? He was a pretty ardent War Democrat after Sumter.

Lincoln vs Breckenridge. I can't wait.

What do you mean that Douglas is in this as well?

Oh, that's Douglas desperate last-ditch effort to save the Union. At this point he's anathema in both the South and the North, so him being elected is basically impossible.

Who did Lincoln select for VP

The fact that the Dems selected the Southerner rather than the breakaway Dems did so means the party will go extinct after the Civil War... most likely

To quote another poster, which is Lincoln's VP? Is he going to stick with Hamlin or go with someone else?

Hamlin was, according to Eric Foner, selected without Lincoln's input. He was chosen because as a former Democrat and an easterner he balanced the ticket. Since Lincoln is much more influential ITTL, he may be able to select his own VP this time. But before deciding, I wanted to ask for your input.

The revolution of 1860? What does Lincoln have planned...

That's the title of one of the Battle Cry of Freedom's chapters. The election of a Republican will indeed mark a Revolution in the sentiments of the people and the history of the nation. But at the same time, some folks down at Charleston are planning their own revolution.

I actually wonder if Breckinridge would get the nomination in this timeline.

In truth, he was more moderate than people might credit - more of an heir of Henry Clay (he inherited much of his machine and support) than a fire-eater. (William C. Davis's work on Breckinridge is worth reading in this regard.)

Southern Democrats OTL actually chose Breckinridge to grow their appeal in the border states precisely because of that background. And of course he was the sitting vice president, which gave him additional cachet.

Here, he's not the Veep, and the fire eaters are eating a lot more fire. Jefferson Davis and Robert Hunter might get a harder look here.

Breckinridge was selected as a result of a strange coalition of moderates and fire-eaters. With Douglas mostly out of the picture, and the Constitutional Union even weaker, the contest is basically him vs. Lincoln. Some moderates still believe they could outright win, and for that they chose a fellow moderate. But fire-eaters also supported Breckinridge because they believe he can't win at all, and that secures secession. After all, if the North rejects even the most moderate man the South can offer, the necessity of seceding is clear. Davis refused to run because he's also anticipating a revolution (as much as he doesn't really want it) and he'd rather be a general than a president. This allowed Breckinridge to win, though of course many contested it.

By the way, I never said that he wasn't Buchanan's VP...

By the way, I never said that he wasn't Buchanan's VP...

You didn't? Maybe I misread something.

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: