Dear

souvikkundu25140017 , I hope this update anwers your question.

------------------

Part 22: The Lands of Vikramaditya

Despite being one of the richest corners of the Earth, the vast Indian subcontinent has spent most of its history divided into multiple small kingdoms that often fought each other, unlike China or even Iran, which were often united even if not completely centralized like the former. However, under fortunate circumstances, a great conqueror could arise and bring most of the lands between the Indus and the Ganges under his rule, and from there control most of the subcontinent. Two such conquerors were Chandragupta Maurya and his more famous grandson Ashoka Maurya, who, from their capital of Pataliputra, controlled a territory that stretched from Qandahar to the Gulf of Bengal and from the Himalayas to the Krishna river, a mighty empire that was populated by as many as sixty million people. Unfortunately, this realm quickly collapsed in the decades that followed Ashoka's death, and was replaced by the usual mess of petty kingdoms.

By the late third century, as Iran fought for surviival against its new Syrian foe, Rome rebuilt itself and China reunited, the foundations of another great Indian empire were laid in the important kingdom of Magadha. Magadha was quite wealthy and powerful on its, but it had the potential be much, much,

much more than that, as proven by the already mentioned Maurya dynasty, which turned said kingdom into the center of its power. The new family that would lead it back to greatness was started by a king named Gupta, who is known from only a few sources, but apparently left for his descendants a promising and stable realm from which they could build on. His grandson, Chandragupta I, who ruled from 319 to 350 A.D., was the first member of the dynasty to be given the title of "Great King of Kings", which showed just how Magadha's power had grown under the rule of the early Guptas, and how it could grow even further. In 350 A.D., Chandragupta was succeeded by his son, Samudragupta, who would become one of the dynasty's greatest members and was already planning to lead his kingdom to new heights of grandeur by subjugating the southern kingdoms of the subcontinent.

These dreams were brutally smothered in the cradle.

A well preserved coin that was made during Samudragupta's reign.

In the 340s, a massive invasion took place in northwestern India. The Kidarites, who had been expelled from Transoxiana, their homeland, by the Celestial Empire, crossed the Khyber Pass in large numbers and settled in the fertile valleys of the Punjab, the land of five rivers, home to large cities such as Taxila, famous for its university, which attracted scholars and students from regions such as Greece, Mesopotamia, Iran and even China, and fielded professors that were among the very best in their respective subjects, such as medicine, philosophy and even politics (one of its most famous students was Chandragupta Maurya himself). The arrival of the Kidarites, surprisingly enough, did not devastate the region, with Taxila becoming the capital of a powerful new state, with its king, a formidable warrior named Kidara. converting to Buddhism and becoming an important sponsor of said religion, refurbishing many monasteries and similar centers of learning everywhere, especially in Gandhara, the area where Taxila was located (1). After spending the rest of the decade consolidating his power and getting used to it, Kidara was ready to expand it once again, and his new target was none other than Magadha.

While this was all happening, Samudragupta had just been crowned Maharaja, and was planning to subjugate or perhaps even conquer the kingdoms of the south in a single grand campaign. This campaign would never materialize, for the Kidarites surged from the west with a massive army that captured every city that stood before it with no opposition (since most of the Gupta soldiers were massed in the south in preparation for the war that would erupt there), marching along the course of the Yamuna and later the Ganges. By the time the king of Magadha finally realized what was happening, Kidara's troops had already captured the critical city of Kausambi, and his next stop was Pataliputra. After calling off his plans and gathering all the soldiers that were left (which numbered tens of thousands, actually) for a desperate defense of the capital, whose gates would otherwise be wide open for the invaders (2).

While many events in this period of history are often known only from a few broken sources, making it very difficult to pinpoint when and where they happened, the monumental confrontation between Kidara and Samudragupta is a glaring exception, with it being documented by poets, historians, musicians and multiple other intellectuals, including many who studied in Taxila. The battle between the two kings and their anonymous soldiers, one of the largest and bloodiest ever to happen in the subcontinent, took place near the town of Sasaram, located right on the immediate vicinity of Pataliputra, in the autumn of 353 A.D..

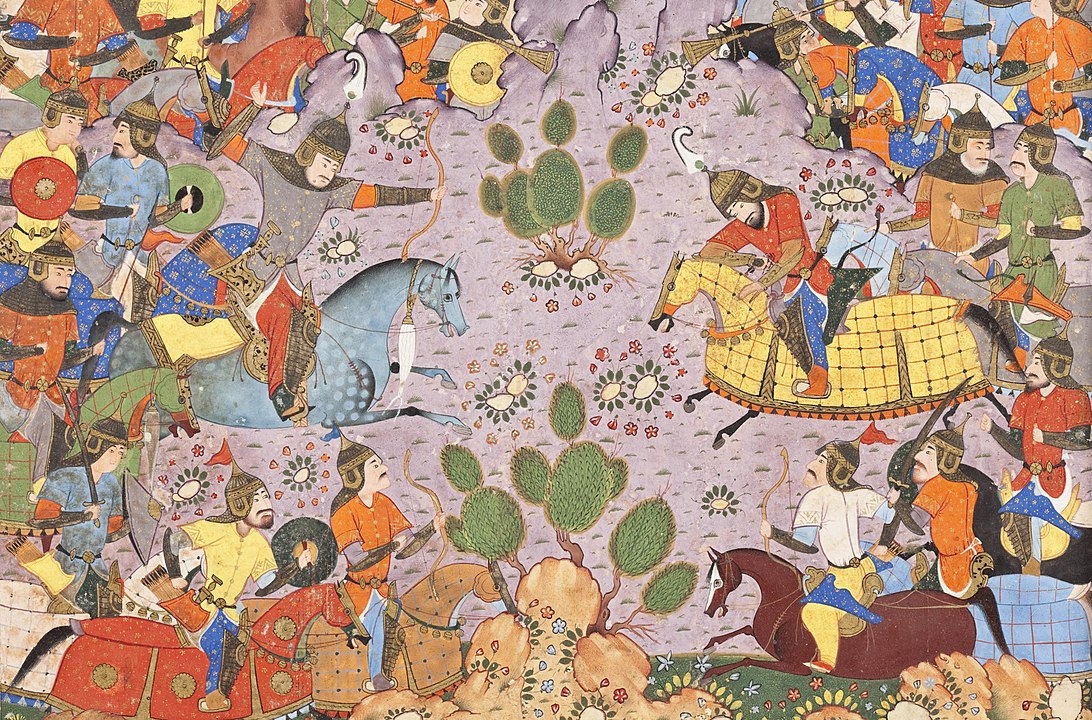

A mural depicting the Battle of Sasaram.

Contemporaries say that both armies had one million men each, and half of both perished on the battlefield, with the waters of the Ganges ran red with blood for a month due to the scale of the carnage. Though these accounts are obviously exaggerated, it does give an idea just how massive and brutal the Battle of Sasaram was (3). However, at the end of the day, the Magadhis controlled the battlefield, and although his army was tired and bloodied, Samudragupta could finally breathe a sigh of relief, for his capital was safe from enemy hands for the moment. The was was not over just yet, and the Maharaja spent the rest of the year reoccupying the lands that had been overrun by the Kidarites along the Ganges and the Yamuna, starting with the reconquest of Kausambi. By the time 353 reached its end, the status quo ante bellum had been restored, with Kidara deciding that abandoning all of his new conquests and limping back to Taxila was a better idea than fighting an emboldened enemy right in the middle of their homeland.

Although he was safe for the moment, Samudragupta knew that it would be only a matter of time before the Kidarites invaded Magadha again, and, if historians are to be believed, he believed that he had no choice but to pre-empt their attack and invade the Punjab before they could recover. Gathering a mighty force that may have had as many as 100.000 infantrymen and 40.000 horsemen, as well as hundreds of elephants, Samudragupta crossed the Yamuna in the spring of 355 A.D. and marched northwest, bent on capturing Taxila and after that seal off the Khyber Pass from any additional invaders that could lay beyond it. In a curious role reversal, Kidara had no choice but gather the soldiers that he had left, a formidable 100.000 men, and sally forth to meet his foe in the wide plains of Tarain, right on the border of the two kingdoms (4).

Though it ended up becoming the most celebrated of all of Samudragupta's victories, the Battle of Tarain was actually a very even, hard fight right until its last moments, despite Kidara's obvious numerical inferiority. The reason for that was due to the fact that the Kidarites were excellent warriors in their own right, and the horse archers that they had were especially deadly, often spreading panic into the Magadhi ranks by creating a seemingly endless rain of suffering and death. This martial prowess was magnified by Kidara's talent as a military leader, which showed when he, according to some sources, organized his army in a way that allowed his soldiers to outnumber the Magadhis in a few crucial points, a strategy that, if successful, would allow him to break up Samudragupta's massive army and defeat it in detail. However, it seems that he didn't realize just how many elephants the Maharaja had, and they caused just as much terror among his own soldiers as his horse archers did to the enemy. In the end, as his army began to buckle, under the numerical weight of its foe, who was no slouch either, Kidara was hit in his right eye by a stray arrow, dying shortly after. This was the straw that broke the camel's back, and the Kidarites force quickly devolved into a panicked mess that was easily wiped out.

Samudragupta's army marches in triumph after the Battle of Tarain.

Without any forces left to oppose him, and the Kidarite kingdom now leaderless due to the death of its king, Samudragupta had no difficulties in conquering it within a few years. By the time he died in 375 A.D., after ruling Magadha for twenty five years, all of the punjab was under his authority, and the critical Khyber Pass had been heavily fortified, with a fortress being built just outside of the town of Purushapura (5). The Maharaja went down in history as one of the greatest monarchs of Indian history, a ruler who not only saved his land from the brink of destruction, but also vanquished his greatest enemy and conquered

his kingdom instead, sealing off the subcontinent from northern nomads such as the one that he defeated for many years to come. But even his legacy would eventually be overshadowed by that of his son, the legendary Chandragupta II.

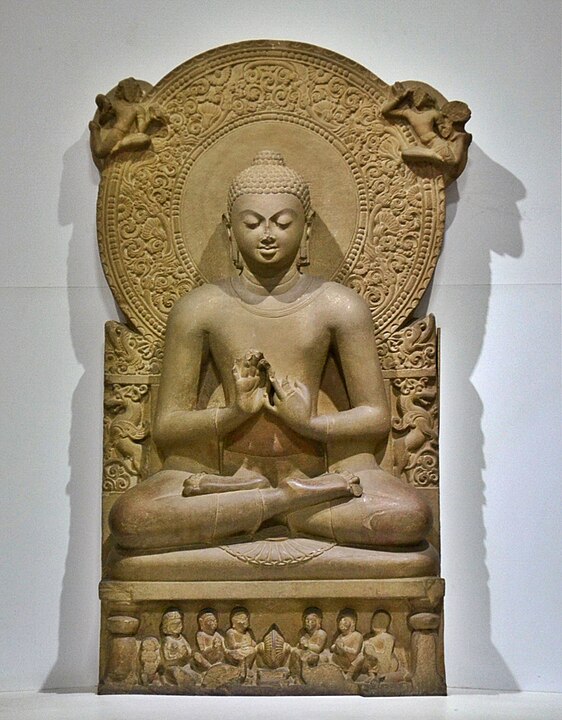

Little is known about Chandragupta's early life, other than the fact that he accompanied his father in a few of his campaigns in the Punjab, and received a first-class education, evcen being sent to the University of Taxila, where he spent a few years learning the arts and sciences, especially political ones (6). Because of this upbringing, he became a great patron of Buddhism, with some sources even saying that he converted to said religion, while others disagree on that regard. However, all agree that he sponsored the construction of new monasteries and schools all over the Indo-Gangetic Plain, from Purushapura to Pataliputra, becoming the single most powerful sponsor of Buddhism since the days of emperor Ashoka. His greatest material and intellectual legacy by far was the construction of the University of Varanasi, a world famous institution that exists to this day, just like its counterpart in Taxila. Working in unison, these universities would create an immense number of bureaucrats, philosophers, artists and inventors for the next centuries, being directly responsible for the creation of things such as the first known hot air balloon and eventually the first modern steam engine

(7).

The ruins of Varanasi's first university. As the years passed, the institution was moved to different buildings.

But far from being just an intellectual, and unlike the pacifist Ashoka, Chandragupta II was an eager, ambitious and very successful conqueror, even surpassing his father. The first major offensive was made against the kingdom of the Western Satraps, a state that controlled the fertile region of Sindh (the area where the Indus met the ocean) and Gujarat, a place whose cities had become quite wealthy thanks to maritime trade. This conquest brought Magadha's wealth and power to new heights, since it allowed the cities of the Indus and the Ganges to trade directly with regions such as Iran, Axum and Egypt, with the port of Patala, located right on the mouth of the Indus, becoming especially rich thanks to that, with many spices and silks and other valuable materials flowing through it every day. However, Chandragupta's most celebrated military achievement, the one that gave him the title of "Vikramaditya" (Vikramaditya being a legendary, ideal emperor) was the crossing of the Hindu Kush, a massive expedition that happened in 390 A.D. and led to the conquest of Kabul, Ghazni and eventually Qandahar, and also assisted in the destruction of the massive Hephthalite Empire that had been created by Mihirakula and Khushanavaz, both of whom were too busy trying to conquer Iran to notice the mighty new foe that was rising in the east until it was too late (8).

Summary:

Late 3rd century A.D. -- The Gupta dynasty begins to rise in Magadha.

319-350 A.D. -- Reign of Chandragupta I, first emperor of the Gupta dynasty.

340s -- The Kidarite kingdom rises in the Punjab.

350 A.D. -- Accession of Samudragupta.

353 A.D. -- The battle of Sasaram takes place, and although it is a tactical draw, it is a decisive strategic victory for the Magadhis, who manage to stop the Kidarite invasion of their country.

355 A.D. -- Samudragupta decisively defeats and kills Kidara in the battle of Tarain. The Punjab is captured shortly after, with Taxila capitulating after a brief siege.

367 A.D. -- The fortress of Purushapura, located right outside the city with the same name, is completed, sealing the Khyber Pass from foreign invasions for the time being.

375 A.D. -- Samudragupta dies from old age, and is succeeded by his son Chandragupta II.

386 A.D. -- Chandragupta conquers the Western Satraps, adding the regions of Gujarat and Sindh to Magadha. From now on, all of India north of the Narmada river is united under Gupta rule (8).

390 A.D. -- Chandragupta conquers Kabul, Ghazni and Qandahar after crossing the Hindu Kush mountains. This, combined with Khushnavaz's defeat at the Battle of Valashabad, causes the destruction of the Hephthalite Empire.

403 A.D. -- The University of Varanasi is opened, and begins to function shortly after.

415 A.D. -- Chandragupta II dies and is succeeded by Kumaragupta I.

------------------

Notes:

(1) The Kidarite conquest of the Punjab didn't cause much devastation IOTL, so I don't see why that would be different here.

(2) IOTL, Samudragupta's southern campaign became a reality, and the kingdoms of that region became tributaries. Here, that doesn't happen, leading to a Gupta Empire that is more focused on the north.

(3) IOTL, Sasaram was the capital of the Sur Empire, an entity that, for a brief time, expelled the Mughals from India.

(4) The Battle of Tarain that happened IOTL led to the eventual establishment of the Delhi Sultanate and Muslim rule in northern India.

(5) Peshawar.

(6) That is a butterfly spawned from the fact that Samudragupta was more focused on the north than OTL.

(7) That's right, India will be the first region in the world to industrialize.

(8) The northern focus of the Guptas butterflies the invasions of Toramana and Mihirakula, which IOTL devastated northern India and greatly contributed to the decline of Buddhism, away.