Chapter Fifty-Four: The Peasant's War

"An army marches on its stomach."

-Napoleon Bonaparte

"Comrade-Peasantry; unite hands! By the fruit of your labours and the sweat on your brow you have fed the overlords for so long. Now the chance is at hand to take what is yours once more..."

-Alexander Antonov to his men

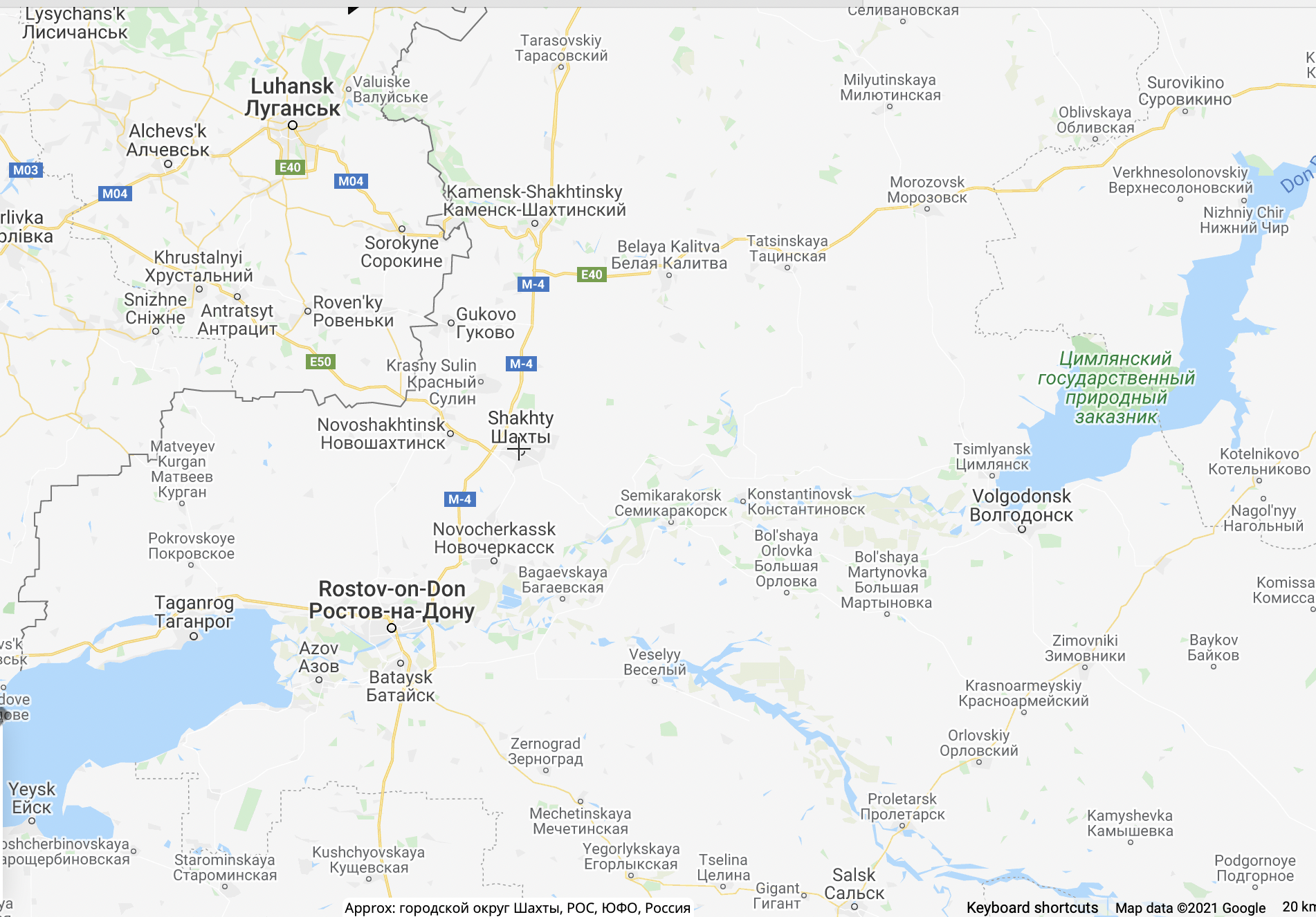

Russia had always been an agricultural nation; despite the growth of industry and cities over the past decades, the majority of Russians still lived on the land. Though serfdom was half a century gone, the average Russian peasant’s life was miserable. Many lived on communal farms, dependent on a few assigned strips of land and a couple of animals to make ends meet. Conscription took their sons away for years; the wages he sent home were seldom enough to atone for the loss of his labour. Many fathers, sons, and brothers had never come home from the Great War, which had made collecting the harvest difficult. Every year since 1914 had been lean, but now the civil war worsened matters. Russia’s harvest season stretches from July through August, so it was just as the Brusilov Offensive was winding down that peasants began to reap what they’d sowed. Facing the loss of many of their ports- and thus their opportunities to trade with the wider world- the Tsarists were hellbent on requisitioning as much as possible. Those peasants who lived on estates as serfs in all but name saw officers speak with their ‘landlords’ (‘owners’ would’ve been a more apt description), after which armed men entered the common fields and forced them to work at bayonet point while their landlords cradled a bag of rubles- few of which made it into the peasant’s pockets. Independent farmers who lived in agricultural villages (dubbed ‘mir’) found themselves facing military occupation. Armed soldiers requisitioned whatever they wanted and then marched off, leaving the villagers destitute. Republican troops were just as guilty of this as Tsarists but were better propagandists.

Contrary to contemporary propaganda, Alexander Kerensky was no friend of the peasantry. The May Day General Strike had begun partially because city-dwellers blamed the Tsarina for the high cost of living. For the moment, the people accepted their privations because there was a war on, but Kerensky knew how quickly that could change. Once Hungary's rebel regime had failed to deliver the goods, the people had returned to the ancien regime with the cry "peace, bread, and land!" If it could happen in Budapest, it could happen in Moscow. Disrupting the harvest would harm his own side as much as the Tsarists, and Kerensky didn't want to cause famine. For the poor Russian peasant, it made no odds whether the men trampling his field were Tsarist or Republican; they were armed men nabbing his produce without paying. Cynicism sprouted as conservatives realised the Tsar was not their benevolent father, and liberals realised Kerensky's dreams of equality didn't extend to them.

Caught between a rock and a hard place, Russia's peasantry found a third option.

Peasant champion Alexander Antonov

Alexander Antonov had been born in Moscow in 1889, but grown up in the poor North Caucasian town of Tambov. Supporting his family by the sweat of his brow, combined with losing his mother at sixteen, had left Antonov bitter, and he found an outlet in radical politics. Like many angry peasants, he supported the Socialist Revolutionary Party, (SRs) and was an unusually active member. He spent the Great War in prison for robbery and, rumour has it, only found out about the September Revolution after his release. Tsar Michael II pardoned Antonov as part of a mass amnesty in January 1918, leaving him free but destitute. Returning to Tambov, Antonov found his family dead and conditions far worse than they'd been ten years ago. Desperate, he became a hired hand for three hot meals a day and a hay bale to sleep on. "That", he recounted shortly before his death, "was the key moment of my life: the moment I realised what the system had done to the Russian peasantry. Anyone who, having seen those conditions with his own eyes as I did, showed apathy, must have a broken conscience." Though his kulak employer was well-off, he and his fellow hired hands "were equal in stature to the pigs and cows." Peasants in common fields or noble estates had it even worse. After bringing in the autumn harvest, Antonov was let go. His wages just sufficed for a train ticket to the 'big city'- in this case, Voronezh. The North Caucasian city wasn't New York, but it overwhelmed a man accustomed to prison cells and potato fields. Poverty drove Antonov to charity kitchens, not all of which were run by conservative Orthodox priests. Antonov met an SR in early 1919 over a bowl of barley broth who'd conducted a robbery with him eleven years ago and invited him to a covert meeting. Banning the Socialist-Revolutionaries only increased their allure, and Tsarina Xenia was failing to clamp down on proscribed groups. Many of Voronezh's intelligentsia turned up and were surprised by "the force with which this illiterate scamp spoke", as one put it. The illiterate scamp detailed the Russian peasant's plight "in such a manner that one could not fail to be moved." Antonov received wild applause, as well as something more important: an audience with Boris Kamkov. Antonov was thrilled. Kamkov was a mythic figure who lived on the edge of the law. He co-led the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, a Marxist group in vogue amongst the peasantry. At the Duck Bay Conference (1), he'd aligned with Vladimir Lenin while his colleague Viktor Chernov had joined Julius Martov.

Lenin's triumph propelled Kamkov to power. When the May Day General Strike erupted, Kamkov (acting with Lenin's approval), called on Russia's peasants to join the struggle. Enlisting many former members of the defunct All-Russian Peasant Union, Kamkov and his retinue roamed the North Caucasian countryside, urging peasants to "aid your bretheren in the cities". With the spring harvest approaching, people had enough food in their back gardens to sustain themselves, and many severed their trade links with the cities. Kamkov was a politican, not a commander of men. His position as leader of the SRs precluded his leading a war in the North Caucasus; he had to oversee the organisation in Moscow. Before departing, Kamkov entrusted Antonov with leading the North Caucasian peasants.

So began the Peasant's War.

Antonov was an outsider. Whereas Kamkov spent time negotiating with Lenin and feuding with Chernov, managing the SRs from afar, Antonov knew only action, and threw himself into the revolution. Like a latter-day Robin Hood, he roamed the countryside with a loyal entourage, exhorting peasants to join the revolution. To men whose livelihoods and faith in the system had been shattered, Antonov offered a way out. Many took up arms and followed him. Wealthy farmers and landowners pleaded with the local governors for protection, but the war against the Republicans took precedence, and they were helpless against the marauding bands. Years of anger at poverty, requisitions, and abuse flooded out under the guise of revolution. Smoke columns on the horizon became a regular sight as some estate turned to ashes. All the conservative caricatures of revolution- the unruly masses burning homes, murdering women and children, and destroying objets d'art- became reality in summer 1919. Not only did Antonov recognise these atrocities, he encouraged them. "Since the landowners have denied the people what is theirs by rights for so long", he wrote to Lenin in July, "it is only fitting that there should be a reckoning now." There were limits to Antonov's power, though. His glorified bandits lacked the military structure of the main combatants. Hunting guns, knives, and pitchforks, not Nagants and grenades, were the order of the day. Lacking supply columns, they lived off the land. This afforded mobility, but prevented them from conquering cities or fighting in anything larger than a skirmish. As the summer dragged on, a balance of power emerged. The Tsarists couldn't pacify the countryside, but were safe inside large cities, and could raid the countryside in force for supplies.

It should come as no surprise that Russia slid into famine in summer 1919. Conscription took labour away from the fields, while both sides lived off the land. Even outside the North Caucasus, where Antonov held no sway, there was chaos. Many fled their fields to avoid the wrath of approaching troops, only to find on their return that the fields were bare and the barn was empty. Such peasants then became refugees, wandering aimlessly in search of food. Poor logistics encouraged men to carry as much food with them as possible- after all, they didn't always know when their next meal would be- and to burn what they couldn't take lest the enemy use it. Supplying millions of men with twice the calories a normal man needs strained the system, leaving little for civilians. And all this was in quiet areas where the peasantry wasn't actively revolting.

The cities soon felt the impact. Food shortages had been common since the General Strike, but everyone had known the food existed. Rationing, breadlines, and distribution under gunpoint were harsh but reasonable. Now, things changed. You got to the breadline, stomach growling, cards in hand, only to find chaos. There was no bread, the soldiers explained. Go home, we cannot help you. Arguing with an armed man is seldom a good idea, so what choice did you have? You went home and explained to the wife and kids what had gone wrong, told your little girl why she'd go to bed hungry tonight. The wolf growled at the door as you dozed off, and woke up weak. You could practically taste the bread as you walked back to the distribution centre- but again, nothing. Soon, your pace at work slowed. Every stroke of the saw or crank of the factory handle required just a little bit more effort. Visions of rich, crisp-crusted brown loaves and silky, rich margarine danced before your eyes. They were tantalising enough to make you forget your pain, deafen you to the cries of your wife and daughter. All you did was lie back in bed, numb to your hunger, not even wanting to use the toilet. Your body used sleep to pay itself back for the food it couldn't have... and then one day, you didn't wake up.

A starving girl before a fenced-off factory in Kirov, summer 1920. Note the starving goat roaming behind her.

Russia's social cohesion was falling apart. Something had to change, lest the winner inherit a nation of skeletons.

The Brusilov Offensive petered out in July 1919. The Republicans had exerted themselves but failed to throw the Tsarists back. Alexander Kerensky was content with stalemate outside Moscow, however, as it allowed him to turn his attention south. Enough North Caucasian grain to feed the country lay within reach, and he intended to take it. As he remained in Petrograd, the Provisional President ordered Alexei Brusilov to negotiate with Antonov. Speaking as one reformer to another, perhaps the two could find common ground? A deputy of Brusilov's travelled to Vyazovska- a few hills and huts which Antonov had made his own- bearing Kerensky's requests. The Provisional President, he reminded Antonov, was a former Socialist Revolutionary, just like him. The Russian Republic would respect the peasants, and "adhere to the policies of Comrades Kamkov and Lenin." Besides, the deputy pointed out, Antonov was barely surviving. If he kept playing cat-and-mouse with Tsarist patrols, they would eventually win. Better to enjoy the protection of the Republic.

"If you care about the agricultural classes so much", Antonov retorted, "why are your military commanders wealthy landowners?" He sent the deputy packing.

Alexander Kerensky was livid. "The cooperation of the Russian Republic with the Socialist Revolutionary Party", he wrote to Boris Kamkov, "is predicated upon that organisation's ability to mobilise the rural people of Russia in support of that cause. Failure to do so would reduce the incentive for our factions to align." Kamkov was no scholar, but he saw the threat. If you can't get your man under control, you will be purged. Kamkov thus travelled down the Volga to meet his subordinate. It's not known how he did it, but Kamkov got his protege on board. Antonov must've realised that if he didn't cooperate, the Republicans might turn on him.

On 14 August, Antonov declared that "the interests of the Russian peasant movement and the interests of the Provisional Government align." The first grain shipments up the Volga River came two weeks later. Kamkov's diplomacy allowed bread to return to the shop windows of Moscow, and it wasn't long before those starving under Tsarist rule began fleeing to the Central Volga. Republican troops arrived in force to defend their new breadbasket, eliminating Tsarist holdouts. Many of Antonov's peasant brigands joined the Republican ranks, as did hungry Tsarists. Come the autumn, as Yudenich inched closer to Petrograd (2), the Republicans tightened their hold on the grain supply.

The decision of the Tsarists to win prestige by destroying Petrograd, while letting their enemy have the economic resources of the North Caucasus, was surely the greatest blunder of the Russian Civil War.

Alexander Antonov was none too happy at the results. Had anyone but Kamkov ordered him to stand down, he would've refused. Antonov had gone from the strongest man in the North Caucasus to a minor cog in the Republican machine. The fall of Petrograd told him what a mistake he'd made. The end of the war was near, Kerensky and Lenin were missing, presumed dead, and it was only a matter of time before Moscow fell. (3) Antonov was a peasant at heart. The endless wheatfields and rolling hills were his home, not cramped wartime Moscow. He identified with simple country folk, not politicians like Kamkov or generals like Brusilov. The trains of wheat which rolled into the capital meant salvation for the urbanites, but Antonov knew how they'd gotten there. His people had reaped and sowed at gunpoint to feed this beast of a war effort, all because of him. All because he'd capitulated.

Alexander Antonov hadn't given up hope for his people, and he vowed that whatever happened to Russia, he would carry on the fight till his last breath.

(1) New readers: see chapter 47

(2) See the previous chapter-- this should contextualise the line about the 'greatest blunder of the war'

(3) Emphasis on the "presumed"

Comments?