The Soviet Union industrialized poorly. Sure, the amount of finished products rose by a vast degree, as did the number of factories and such, but quality was abysmal.I don't see a victorious russian republic being stable enough to pull off a soviet-esque industrialization. They'll industrialize, but nowhere near as well.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Place In the Sun: What If Italy Joined the Central Powers? (1.0)

- Thread starter Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

- Start date

And they destroyed the agricultural sector via forced collectivization, which ultimately caused the deaths of millions.The Soviet Union industrialized poorly. Sure, the amount of finished products rose by a vast degree, as did the number of factories and such, but quality was abysmal.

Do I hear Holdomor?And they destroyed the agricultural sector via forced collectivization, which ultimately caused the deaths of millions.

I originally had a long post typed up outlining the key events and policy ethoses of the Romanov rulers ITTL from 1801 - 1920, but a computer crash wiped it. So I will summarize:The reason I'm rooting for the Tsarists is because of how rotten the foundations the Republic is. Rather than drinking from the poisoned chalice, its better to survive and nourish yourself from the bitter but reliable drink that is the Russian Monarchy.

With the way things are going, I don't see the Russian "Republic" if it wins, actually evolving into a functional republic. If anything its set to devolve into a dysfunctional mess likely starting another civil war or an era of general stagnation with the total failure of its barely functional government.

- Of the six tsars OTL reigning from 1800 - 1917, not one had a stable transfer of power from one to the next. Paul I was assassinated, with his son seemingly complicit if not intending for death to occur. Alexander I caught sudden illness and died, which coupled with succession uncertainties between Nicholas I and his brother Constantine (plus Alexander's repeated waffling on whether he supported or wanted to quash liberalism) led to an attempted coup by the Decembrist Society amid Nicholas' coronation in 1825. Nicholas himself caught pneumonia amid the end of the Crimean War and seems to have committed suicide by refusing treatment as penance, in spite of this leaving Alexander II to negotiate peace on terrible terms. Alexander II was obviously bombed to death literal hours after approving an extremely primitive constitutional reform for discussion and implementation. Alexander III declined rapidly due to a sudden case of nephritis, leaving the throne to woefully-unprepared Nicholas II. And Nicky stepped down from power only when the situation was so dire for Imperial authority that Mikhail was essentially incapable of stepping in as his successor were he to try.

- Likewise, governing ethos and attitudes towards role in government varied rapidly from sovereign to sovereign in the last century of the empire. Alexander I started out as a reformist and guarantor of human rights, then bounced between suspicion and amicability towards Napoleon's ideals before Metternich finally convinced him to abandon liberalism entirely; the dissonance in his ideals seems to have contributed substantially to his decline in wellbeing near the end of his life, plus the rollback of most government reformation he accomplished by reactionary court figures as he withdrew from political activity. Nicholas I founded the ideals of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, and placed Poland under martial law that lasted over thirty years. Alexander II introduced elected local government amid broad liberalization of the economy and educational structures, which then abruptly segued into the muzzling of all these institutions under the rule of his son and the institution of a nation-wide state of emergency which lasted from 1882 until the dissolution of the empire. Nicholas II is the only one who can really be construed as having continued the policies and relative outlook of his predecessor (a strong belief in divinely-ordained absolute rule), but his inclinations were as variable as the figures surrounding and influencing him.

- A significant factor as to why the empire was able to retain the surface-level veneer of stability that it did through the later decades was through unbelievably harsh suppression of its own population. Alexander III's police state was de jure a temporary set of legal changes, but ended up lasting nearly forty years while granting significant power to the Okhrana and state in suppressing dissidents. Almost every tsar from Nicholas I onward utilized extreme anti-Semitism (the conscription of children into cantonal brigades, banning of settlement outside of cities, the May Laws - another feature of Alexander III which were legally temporary and factually permanent - setting population quotas for inhabitation outside the Pale of Settlement) to shore up appeal from religious figures and unite the population against a bogeyman. Non-Russian language was varyingly suppressed in education and banned from public use entirely, again in every ruling period from Nicholas I's onward.

The current emperor, Andrei I, seems to regard the Constitution with some respect, but currently he is not only a very young figure in a sea of reactionary aristocrats, but de facto subservient to his father - who has expressed interest in removing both the 1906 and 1918 constitutions. Andrei may be the de jure Tsar and fairly charismatic among the soldiery, but his father is a ruthless figure and very much a "my way or the highway" sort of man, going off his conduct with Kirill and the initial agreement to hand the crown to his son. In the event of a Tsarist victory, I don't really know who is better poised to come out on top.None of current Romanovs want to actually go back to serfdom or the pre-Nicholas era. Most of them have made their peace with the Constitution.

Last edited:

Well, yes, but I don't think a Kerensky & Co Republic would pull off even that much.The Soviet Union industrialized poorly. Sure, the amount of finished products rose by a vast degree, as did the number of factories and such, but quality was abysmal.

Kerensky and co. would manage a more balanced industrialization than the Soviets at least, which already makes them better than the Soviets. The Soviets set such a low bar that it's not hard to cross.Well, yes, but I don't think a Kerensky & Co Republic would pull off even that much.

The Soviets managed to industrialize enough to defeat the Nazis. General Winter only does so much. General Zhukov had to have the materials to do the rest.Kerensky and co. would manage a more balanced industrialization than the Soviets at least, which already makes them better than the Soviets. The Soviets set such a low bar that it's not hard to cross.

the original plans for the ussr's industrialization were modified from the Kerensky regime's plans (though the republican plans were far more sane and realistic and more capitalistic in nature) so I don't get why the idea that the republicans couldn't industrialize properly is coming from.

The Soviets were too focused on heavy industry and most of its industrial sector can't compete with the West commercially. I don't think Kerensky and co. can actually do everything they want to do, but at least they would build the seed for an industrial sector that could compete effectively with the rest of the world, ie. not have the economy be less than California.The Soviets managed to industrialize enough to defeat the Nazis. General Winter only does so much. General Zhukov had to have the materials to do the rest.

PS: will we get a Comintern pact vs Germany and allies for the second weltkreig, and will the US tag in?

Plans don't mean you can put them into effect. I'm not sure how this is hard to follow. The question isn't 'do Kerensky and Co Plan to industrialize' the question is 'will their grip on Russia be strong enough for them to even do as much as Stalin did'. I think the answer is no. we'll find out one way or another when @Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth gets that far, if Kerensky and Co even do win.the original plans for the ussr's industrialization were modified from the Kerensky regime's plans (though the republican plans were far more sane and realistic and more capitalistic in nature) so I don't get why the idea that the republicans couldn't industrialize properly is coming from.

ahmedali

Banned

I hope that the Bolsheviks or the republicans or the palace coup kills the Grand Duke or uses his mind and preserves the constitution because if the constitution is abolished the situation will be worse than before.I originally had a long post typed up outlining the key events and policy ethoses of the Romanov rulers ITTL from 1801 - 1920, but a computer crash wiped it. So I will summarize:

Between the research I did then and my previous studies of Imperial Russian civic and geopolitical history, the image I have obtained was not of a stable if hardline government, but an autocratic system continually embattled against internal dissent and crippled in reform due to an existential need to appease the higher nobility, the centralization of power behind a single autocrat giving court actors undue influence (ex. Archimandrite Photius, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Grigory Rasputin), and an almost hilariously long streak of bad luck targeting reformist tsars. The Russian republican movement has a large number of factors standing between it and stability, but pointing to Tsarist history as an alternative does not produce much contrast. For every proto-fascist or Bolshevik strongman who could creep to power within the Republic's government, there is a court mystic or charismatic Black Hundredist within earshot of the Tsar. In the context of Russian history, the latter has seen even more examples than the first.

- Of the six tsars OTL reigning from 1800 - 1917, not one had a stable transfer of power from one to the next. Paul I was assassinated, with his son seemingly complicit if not intending for death to occur. Alexander I caught sudden illness and died, which coupled with succession uncertainties between Nicholas I and his brother Constantine (plus Alexander's repeated waffling on whether he supported or wanted to quash liberalism) led to an attempted coup by the Decembrist Society amid Nicholas' coronation in 1825. Nicholas himself caught pneumonia amid the end of the Crimean War and seems to have committed suicide by refusing treatment as penance, in spite of this leaving Alexander II to negotiate peace on terrible terms. Alexander II was obviously bombed to death literal hours after approving an extremely primitive constitutional reform for discussion and implementation. Alexander III declined rapidly due to a sudden case of nephritis, leaving the throne to woefully-unprepared Nicholas II. And Nicky stepped down from power only when the situation was so dire for Imperial authority that Mikhail was essentially incapable of stepping in as his successor were he to try.

- Likewise, governing ethos and attitudes towards role in government varied rapidly from sovereign to sovereign in the last century of the empire. Alexander I started out as a reformist and guarantor of human rights, then bounced between suspicion and amicability towards Napoleon's ideals before Metternich finally convinced him to abandon liberalism entirely; the dissonance in his ideals seems to have contributed substantially to his decline in wellbeing near the end of his life, plus the rollback of most government reformation he accomplished by reactionary court figures as he withdrew from political activity. Nicholas II founded the ideals of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, and placed Poland under martial law that lasted over thirty years. Alexander II introduced elected local government amid broad liberalization of the economy and educational structures, which then abruptly segued into the muzzling of all these institutions under the rule of his son and the institution of a nation-wide state of emergency which lasted from 1882 until the dissolution of the empire. Nicholas II is the only one who can really be construed as having continued the policies and relative outlook of his predecessor (a strong belief in divinely-ordained absolute rule), but his inclinations were as variable as the figures surrounding and influencing him.

- A significant factor as to why the empire was able to retain the surface-level veneer of stability that it did through the later decades was through unbelievably harsh suppression of its own population. Alexander III's police state was de jure a temporary set of legal changes, but ended up lasting nearly forty years while granting significant power to the Okhrana and state in suppressing dissidents. Almost every tsar from Nicholas I onward utilized extreme anti-Semitism (the conscription of children into cantonal brigades, banning of settlement outside of cities, the May Laws - another feature of Alexander III which were legally temporary and factually permanent - setting population quotas for inhabitation outside the Pale of Settlement) to shore up appeal from religious figures and unite the population against a bogeyman. Non-Russian language was varyingly suppressed in education and banned from public use entirely, again in every ruling period from Nicholas I's onward.

The current emperor, Andrei I, seems to regard the Constitution with some respect, but currently he is not only a very young figure in a sea of reactionary aristocrats, but de facto subservient to his father - who has expressed interest in removing both the 1906 and 1918 constitutions. Andrei may be the de jure Tsar and fairly charismatic among the soldiery, but his father is a ruthless figure and very much a "my way or the highway" sort of man, going off his conduct with Kirill and the initial agreement to hand the crown to his son. In the event of a Tsarist victory, I don't really know who is better poised to come out on top.

And I think that Tsar Andrei is old enough to make the right decisions

If the Constitution is abolished, the Romanovs will become like the Bourbons, and Lenin will cry angrily, "They have learned nothing and forgotten nothing."

The bizarre thing for me is that by starting at 1800, you made me curious as to what the transfer of power was *prior* to 1800 which might have been deliberately excluded to start a list of unstable transitions. Given that that changeover was from Catherine the Great to Paul I and that Paul deliberately looked for her testament which might have excluded Paul in favor of her grandson, that doesn't particularly scream stable. The British may have found the transitions under the early George's chaotic, but not when compared to the Russians...I originally had a long post typed up outlining the key events and policy ethoses of the Romanov rulers ITTL from 1801 - 1920, but a computer crash wiped it. So I will summarize:

Between the research I did then and my previous studies of Imperial Russian civic and geopolitical history, the image I have obtained was not of a stable if hardline government, but an autocratic system continually embattled against internal dissent and crippled in reform due to an existential need to appease the higher nobility, the centralization of power behind a single autocrat giving court actors undue influence (ex. Archimandrite Photius, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Grigory Rasputin), and an almost hilariously long streak of bad luck targeting reformist tsars. The Russian republican movement has a large number of factors standing between it and stability, but pointing to Tsarist history as an alternative does not produce much contrast. For every proto-fascist or Bolshevik strongman who could creep to power within the Republic's government, there is a court mystic or charismatic Black Hundredist within earshot of the Tsar. In the context of Russian history, the latter has seen even more examples than the first.

- Of the six tsars OTL reigning from 1800 - 1917, not one had a stable transfer of power from one to the next. Paul I was assassinated, with his son seemingly complicit if not intending for death to occur. Alexander I caught sudden illness and died, which coupled with succession uncertainties between Nicholas I and his brother Constantine (plus Alexander's repeated waffling on whether he supported or wanted to quash liberalism) led to an attempted coup by the Decembrist Society amid Nicholas' coronation in 1825. Nicholas himself caught pneumonia amid the end of the Crimean War and seems to have committed suicide by refusing treatment as penance, in spite of this leaving Alexander II to negotiate peace on terrible terms. Alexander II was obviously bombed to death literal hours after approving an extremely primitive constitutional reform for discussion and implementation. Alexander III declined rapidly due to a sudden case of nephritis, leaving the throne to woefully-unprepared Nicholas II. And Nicky stepped down from power only when the situation was so dire for Imperial authority that Mikhail was essentially incapable of stepping in as his successor were he to try.

- Likewise, governing ethos and attitudes towards role in government varied rapidly from sovereign to sovereign in the last century of the empire. Alexander I started out as a reformist and guarantor of human rights, then bounced between suspicion and amicability towards Napoleon's ideals before Metternich finally convinced him to abandon liberalism entirely; the dissonance in his ideals seems to have contributed substantially to his decline in wellbeing near the end of his life, plus the rollback of most government reformation he accomplished by reactionary court figures as he withdrew from political activity. Nicholas II founded the ideals of Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, and placed Poland under martial law that lasted over thirty years. Alexander II introduced elected local government amid broad liberalization of the economy and educational structures, which then abruptly segued into the muzzling of all these institutions under the rule of his son and the institution of a nation-wide state of emergency which lasted from 1882 until the dissolution of the empire. Nicholas II is the only one who can really be construed as having continued the policies and relative outlook of his predecessor (a strong belief in divinely-ordained absolute rule), but his inclinations were as variable as the figures surrounding and influencing him.

- A significant factor as to why the empire was able to retain the surface-level veneer of stability that it did through the later decades was through unbelievably harsh suppression of its own population. Alexander III's police state was de jure a temporary set of legal changes, but ended up lasting nearly forty years while granting significant power to the Okhrana and state in suppressing dissidents. Almost every tsar from Nicholas I onward utilized extreme anti-Semitism (the conscription of children into cantonal brigades, banning of settlement outside of cities, the May Laws - another feature of Alexander III which were legally temporary and factually permanent - setting population quotas for inhabitation outside the Pale of Settlement) to shore up appeal from religious figures and unite the population against a bogeyman. Non-Russian language was varyingly suppressed in education and banned from public use entirely, again in every ruling period from Nicholas I's onward.

The current emperor, Andrei I, seems to regard the Constitution with some respect, but currently he is not only a very young figure in a sea of reactionary aristocrats, but de facto subservient to his father - who has expressed interest in removing both the 1906 and 1918 constitutions. Andrei may be the de jure Tsar and fairly charismatic among the soldiery, but his father is a ruthless figure and very much a "my way or the highway" sort of man, going off his conduct with Kirill and the initial agreement to hand the crown to his son. In the event of a Tsarist victory, I don't really know who is better poised to come out on top.

The problem with the Russian government at this point is that both options are awful. The Tsarists have become an echo chamber for the Grand Duke's revenge fantasies and incompetent sycophants, all while would-be Tsar Andrei is surrounded by people who likely are not fond of any government aside from "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality," even if they aren't Black Hundreds-level of extreme. After all, most of the liberals have at this point decamped for the Republicans. Meanwhile, the Republicans are divided between authoritarian far-left types like the Bolsheviks, authoritarian left-leaning types like Kerensky, and a smattering of liberals. The peasants are rebelling and will likely demand serious concessions in exchange for their aid, all the while.

As for industrialization, I can't imagine anything worse in policy than the OTL Bolshevik efforts, but Russia is likely to remain poorer than the rest of the Congress of Europe for some time. Unless the Bolsheviks completely take over (a direction I don't think this TL will be taking), either Kerensky or the Tsarists will make larger efforts at industrialization, but in a way similar to that of Francoist Spain's economic progression - fueled by foreign investment near the capital and St. Petersburg, with the rural areas being hollowed out and with poor conditions for workers. Hopefully, whatever government takes power recognizes that they can't completely exclude the needs of labor, but considering the options, I rather doubt they will.

As for industrialization, I can't imagine anything worse in policy than the OTL Bolshevik efforts, but Russia is likely to remain poorer than the rest of the Congress of Europe for some time. Unless the Bolsheviks completely take over (a direction I don't think this TL will be taking), either Kerensky or the Tsarists will make larger efforts at industrialization, but in a way similar to that of Francoist Spain's economic progression - fueled by foreign investment near the capital and St. Petersburg, with the rural areas being hollowed out and with poor conditions for workers. Hopefully, whatever government takes power recognizes that they can't completely exclude the needs of labor, but considering the options, I rather doubt they will.

It struck me that it might give off the impression, and admittedly I went with 1800 specifically out of compromise between depicting keeping relevance (the political circumstances of Russia, while unique, weren't nearly as unusual in the early modern period as compared to the 19th century and onward) and depicting the full picture of Russia's sovereigns. I debated going as far back as Peter the Great, but decided that more focus should be put on the dialectic between the autocracy and popular sovereignty, which really only came to the fore in Europe with the Napoleonic period.The bizarre thing for me is that by starting at 1800, you made me curious as to what the transfer of power was *prior* to 1800 which might have been deliberately excluded to start a list of unstable transitions. Given that that changeover was from Catherine the Great to Paul I and that Paul deliberately looked for her testament which might have excluded Paul in favor of her grandson, that doesn't particularly scream stable. The British may have found the transitions under the early George's chaotic, but not when compared to the Russians...

That said, earlier periods of history are just as tumultuous and interesting to learn about. Peter's antics in particular are fascinating - the man reminds me a lot of Theodore von Neuhoff if he were in established charge of a massive state rather than a pretender king. But the innate instability of Russia was as visible then as in the 1880s, between Peter's rather insane economic and modernization policies, Pugachev's rebellion during Catherine's reign, and Paul's various idiosyncrasies.

Chapter 56: War Drags On

Chapter Fifty-Six: War Drags On

"God damn it, Tukhachevsky's armies cannot run on patriotism, on exuberance! Trains and armoured cars are needed, because the horse and the marching man are no longer everything. If I cannot retrieve the oil of the South Caucasus and the industry of the Donets, I must end this war."

-Alexander Kerensky

"I remain spectacularly convinced of the value of tradition, my friends. Here, in the open steppe, has anyone called for more tanks, more artillery, more machine-guns? Nyet! Here, war is returned to the noble form of art it always was- bearing a greater resemblance to that used by our ancestors to eject Genghis Khan, than that used by the Germans in France. The noble cavalry sweep, friends, has won the day!"

-Semyon Budyonny

One year after the workers of Petrograd had walked out, Russia still had not found its destiny. Tens of thousands had fallen on the field; yet more had succumbed to hunger and disease. Tsarist blows had come fast. They'd repulsed the Republicans outside Tver and Rzhev before crushing Petrograd. For a moment the revolt seemed doomed. Provisional President Alexander Kerensky was deathly ill in Finland; his legitimacy had died in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks had allies in Helsinki, but were a world away from the worker's councils which had led the country into revolution. No one recognised the "Russian Republic", while Germany was doing everything short of war to aid the Tsarists.

All had seemed lost.

Six months into the New Year, things had changed. Matti Passivuori was to Finland what Kerensky was to Russia, and had planned to intervene after the fall of Petrograd. The Tsarists had saved him the trouble by attacking pre-prepared defences; the counterattack had liberated Petrograd. Though Ukraine still eluded them, the Republicans controlled the North Caucasian breadbasket and industry of the Central Volga. Horror stories and promises of reform had won them support domestic and foreign. The situation in summer 1920 resembled that of a year ago- except the Finns were on-side, the Tsarists were starving, and the Republicans had beaten impossible odds.

It was time to counter-attack, but few knew where. Kerensky wanted to connect freshly liberated Petrograd with Moscow. Isolation from Brusilov's armies had proved fatal once; there was no guarantee another Tsarist attack wouldn't seize the capital again. Finnish reinforcements would facilitate this, while the enemy remained weak in the sector. Local Republican commander Lavr Kornilov concurred. Attack was the best form of defence. Besides, linking up the two greatest cities in Russia would restore some lost legitimacy. Others were less certain. Alexei Brusilov, commander of the forces in Moscow and the Central Volga, bravely flew over enemy territory to confer in Petrograd. He pointed out that his namesake offensive had failed to cross the three hundred miles between Moscow and Petrograd. Having grown used to operating independently while Kerensky hid in Finland gave the Republican general courage. Brusilov refused to launch an attack he believed doomed. Predictability helped only the enemy. Rather than further fighting in the north, Brusilov wanted to turn south. Securing Ukraine or the southern Caucasus would do more than conquering a few northern cities. Kornilov challenged him, arguing that Ukraine and the Caucasus were "peripheries". This was not a war for resources, Kornilov charged, but one for legitimacy. Eliminating the Tsarist strongholds in the north would be far more convincing on the world stage than, as he put it, "sailing past Potemkin's village!" Kerensky proposed a compromise. Brusilov could invade eastern Ukraine provided he launched a subsidiary attack to the north, while the Finns would pursue their own objectives.

Political drama with the Finns (1)- Matti Paasivuori resented being treated as a subordinate- delayed things far longer than they should've, and the Republican plans for attacking in the north were heavily modified. However, Brusilov's plan for seizing the industry of the Donets basin was approved. Besides threatening the Caucasus, Ukraine, and Crimea, this would provide the Republican war machine with valuable industry and metal deposits. (2)

Just as the Republicans prepared to attack, God threw a spanner in the works. Tsarist anti-air guns opened fire on a two-seater above Veliky Novgorod on 12 June, 1920. Two German Albatroses in Russian colours pursued the plane, leaving the pilot- who should have known better than to fly over an enemy city in daylight- without options. Bullets shredded canvas and wood before striking the gas tank. The pilot was dead long before the plane's shattered skeleton slammed into the ground. So too was his passenger: General Alexei Brusilov.

Realising what had happened took time. The lack of secure communications between Petrograd and Moscow meant Brusilov hadn't wired his deputies before taking off. Air travel in 1920 was a chaotic business- weather routinely caused long delays. Or perhaps the conference had simply run longer than expected? After four days, though, it was clear something was wrong. Confirmation only came on the seventeenth, with a gloating article in the Tsarist press. Brusilov's charred remains had been retrieved from the crash and, in fairness to the Tsarists, given a full burial with military honours. His coffin crossed the lines under flag of truce some months later. The loss of Brusilov was a catastrophe. He'd been a miracle worker during the Great War, keeping the Russian Army intact as it withdrew in autumn 1916. Though his namesake offensive had failed, it had shown Republican fighting power and dissuaded the Tsarists from moving on Moscow. Alexei Brusilov was sixty-seven years old, and had given forty-eight of them to Russia.

His successor would have large shoes to fill- and the fate of a nation resting on his shoulders.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky had been born near Smolensk in 1893 and obtained a cavalry commission on the outbreak of the Great War. Despite distinguishing himself against the Germans and Austro-Hungarians, he was captured in late 1915 and spent the rest of the war in a Bavarian fortress. Repatriated as per the Treaty of Konigsberg, he became an adherent of socialism after reading Lenin’s Imperialism As the Self-Destructive Outgrowth of Capitalism. Tukhachevsky joined the Central Volga People’s Army the very day it was founded, and was surprised when his previous rank as a cavalry officer was restored. His valour (he personally led not one but two charges against a Tsarist machine-gun as though it was the summer of 1914) came to Brusilov’s notice, and after being wounded when his horse was shot out from under him he received a promotion. Discharged from hospital the day after Second Borodino, Brigadier General received command of the Moscow garrison. Declaring his “total devotion to the people’s government”, he ordered a “state of heightened emergency” in the city. Banners called for the people to “mobilise in the name of Comrades Lenin and Zinoviev, and of Provisional President Kerensky lest the Tsarists crush you underfoot”. Tukhachevsky put Muscovites to work digging trenches and carrying supplies, and reopened the city’s arms factories. The people grumbled, but the alternative was frightening enough they obeyed willingly. He installed newfound military discipline in the Moscow garrison, building an esprit de corps while quietly reinforcing the power of officers at the expense of the soldier’s councils. After inspecting the garrison on 15 August 1919, Brusilov was so impressed he made Tukhachevsky a full general, second-in-command of the entire Central Volga People’s Army. His methods spread to all the major cities under Republican control. Provisional President Kerensky was too far away to fully understand what was happening in Moscow. He didn’t fully realise that, blinded by his dazzling skill, Brusilov was grooming a protege whose first loyalty was to Marxism, not to the Republic. Tukhachevsky had wanted to launch a relief expedition during the siege of Petrograd, but Brusilov- believing the capital lost- demurred. Tukhachevsky spent several months integrating the North Caucasus, overseeing the transit of supplies and trying to bring Alexander Antonov's peasant bands up to scratch. The experience had opened the general's eyes. Watching men labour all day to keep others from starving had taught him about logistics; hearing the proletarian Antonov's grievances had taught him a thing or two about politics. Restored to Moscow when Brusilov flew to Petrograd, Tukhachevsky was the natural choice to succeed him.

The Republican heroes of the day, Mikhail

Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky and Kliment Yefrevomich Voroshilov, photographed shortly after the end of the civil war.

Aware of what the Central Volga armies were capable of, Tukhachevsky declared Brusilov's plan to attack south a "singularly unambitious idea". The further attacks in the Caucasus were good, but he intended to advance northwards, where alongside the Finns, he would drive the Tsarists from their centres of power before the onset of winter. Tukhachevsky valued surprise, and went to great lengths to make the enemy think he was aiming south. He kept his communication with Petrograd brief, and had agents posing as defectors feed the Tsarists misinformation. Surviving telegrams from Tsarist commanders demonstrate his success: all speak of the need for vigilance in the Caucasus while ignoring the North.

Tukhachevsky's plan was ambitious, but he knew he was capable.

Before his untimely death, Alexei Brusilov had designed the Republican battle-plan for the southern theatre around resources. Eastern Ukraine housed a significant amount of industry that could augment the Republican war machine. It was compressed in a small geographic area and was close to the frontline. The second thrust was more ambitious. Tukhachevsky wanted to drive down the western shore of the Caspian Sea and capture the oilfields of Chechnya and Azerbaijan. The grain of the North Caucasus, the oil of the southern reaches, and industry of the national heartland, would make the Republican machine invincible. Though Tukhachevsky yearned for combat, his job was in Moscow. As a skilled strategist and staff officer, he needed to look at things with detachment, and from a distance. Besides, the revolution needed him. Losing Brusilov had been bad enough; losing him would be worse.

Tukhachevsky had absolute confidence in his subordinates. Kliment Voroshilov was assigned to conquer his birthplace, eastern Ukraine. Ideally, his attachment to the land would help Voroshilov present himself as a liberator, not a conqueror. He'd been too absorbed in radical politics for a command in the Great War, but had distinguished himself during the Brusilov Offensive. Voroshilov was a consummate professional, whose knowledge of his job was matched only by his personal courage and political reliability. The other man was rather different. Semyon Budyonny had joined the cavalry to escape the family farm, and achieved glory (if not substantial success) as an officer in both Manchuria, Poland, and the South Caucasus. His experience with the region and aggressive nature recommended him to Tukhachevsky.

Both had their work cut out for them.

Tukhachevsky's offensive began on the first of August 1920. Over a million men, many of them peasant conscripts, stood behind a frontline half the length of the old German front. Conditions in the west largely resembled the old front. Four days after the attack began, Grand Duke Mikhailovich named Baron Pyotr Wrangel "Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Armies". It fell to the eccentric nobleman to halt the tide. His task was easiest in the west, where Voronezh, Luhansk, and Rostov formed "anchors" for the front. Having predicted they'd face attack, Wrangel had fortified the cities as best he could, even though fighting elsewhere had eaten into his supplies. Voroshilov was no fool, and rather than attacking the cities head-on he bypassed them. Defeating the local Tsarist armies first would let him conquer the cities at leisure; becoming bogged down in sieges would serve only the enemy. Voroshilov struck hard and fast, and with intelligence. Rather than force a crossing of the River Don, Voroshilov moved his main force to the one major Republican-controlled crossing. Pavlovsk was a medium-sized town which Alexander Antonov had delivered to the Republicans in the summer. Its bridge over the great river made it valuable, and the Tsarist garrison had fought hard for it. Now, an infantry brigade and fighter squadron protected the town- and more importantly, the bridge. Best of all, it was equidistant between Voronezh and Luhansk.

Pavlovsk thus became the lynchpin of Voroshilov's attack. Infantry and cavalry burst through into open countryside, heading due west. Bright summer sun baked the Russian steppe. Voroshilov drove due west, creating a Republican 'bulge' in the line. Every day gave the Tsarists a few more miles of flank to cover and a little more confusion as to his objective. Kharkov was the ultimate goal, but he could just as easily wheel north to envelop Voronezh, or south to Luhansk. Caution was Wrangel's watchword- committing to a fixed battle with Voroshilov would deplete his reserves. Intelligence and common sense told Wrangel his foe was looking after his flanks; cutting him off wouldn't be easy. Thus, Wrangel pulled back, harassing the advancing Republicans and holding local strongpoints, but not committing to a pitched battle. By the middle of the month, this strategy was paying off. Though Voroshilov had advanced eighty miles, he hadn't taken anything of strategic value. Kharkov wasn't in immediate danger, and the Republican forces in front of Voronezh and Luhansk were there to defend, not attack.

It was time for a counterattack.

Wrangel spent the last two weeks of August in his headquarters, planning. He was confident- though not certain- that Kharkov would hold. The city was well-fortified, and he had no plans to redeploy its garrison. Besides, if worst came to worst, there was plenty of steppe east of the city to trade for time. Since his position wasn't seriously threatened, Wrangel saw no reason to remain passively defending. Since the enemy had punched a salient in his front, he would return the favour. A swift, sharp strike south of Voroshilov's army would reclaim the initiative, threaten to outflank the Republicans, and secure Luhansk. Grand Duke Mikhailovich gave his blessing after Wrangel promised to complete the task without extra reinforcements.

The counteroffensive began on the twenty-eighth. Having achieved tactical surprise, Wrangel quickly blew past the enemy screening force. His men were in Millerovo, four miles behind the lines, by dusk. While the need to guard against Voroshilov's southern flank (Wrangel's north) left his attack less powerful than his foe's, Wrangel still stunned the enemy. Voroshilov was forced to march units across sixty miles of countryside, severely weakening his own offensive. Cavalry formed the base of the units sent south; they were faster than infantry, especially in the open steppe. They couldn't stem the tide, though. Wrangel widened his salient to further strain Voroshilov's flanks- the more open steppe the enemy had to cover, the harder it'd be to amass a proper reserve. After two weeks, his men had penetrated fifty miles. Behind his success, though, lurked uncertainty. Where was he to go? Voroshilov's main force was still northwest of him. Stripping forces from Ukraine meant the army would face light opposition if it marched westwards, making it a very real threat. Turning north to cut Voroshilov off seemed the obvious choice. Yet at the same time, Wrangel had penetrated deep into the Republican North Caucasus. Decisive success might not only deprive the enemy of his breadbasket, but isolate the Republican armies advancing on the oilfields. Tsaritsyn- hastily renamed Volgograd by the Republicans (3)- was only two hundred kilometres away. Alternatively, Wrangel told himself, he could turn south and chase the Republican armies in the South Caucasus. The euphoria of victory blinded him to his own comparative weakness, and the sheer size of the Russian steppe.

Time was running out; his opponent's next move was already in the works.

Voroshilov had, he freely admitted after the war, been caught off-guard. Wrangel's light opposition had misled him into overestimating his own strength. He'd guarded the base of his salient, but not the surrounding territory, and should have known better. Voroshilov had no intention of giving up, though, and as the days wore on got a handle on the situation. Wrangel, he believed, had struck too far south. Though the Tsarist faced lighter opposition there and didn't have to cross the Donets, he also wasn't striking Voroshilov's supply lines. Three main road and rail junctions connected the Republican army to Moscow: Boguchar to the south, Kalach to the northeast, and Pavlovsk- his jump-off point. Pavlovsk and Kalach were on the opposite end of the Donets from Wrangel; only Boguchar was threatened. Yet, Wrangel's northern flank was seventy miles south of the town. Voroshilov didn't know what his opponent was aiming for, only that he'd erred.

He didn't intend to give Wrangel time to fix his mistake.

Voroshilov explained all this to Tukhachevsky on 14 September, beginning with a request. His plan required the total commitment of his forces, including those guarding his rear. If Tukhachevsky could release a handful of infantry divisions from the strategic reserve to protect the three crucial villages, he'd be most grateful. Tukhachevsky consented, and Voroshilov explained his plan. The senior Republican commander followed along with a map and pencil in his Moscow bunker. "Kliment Yefremovich", he breathed, face glowing, "I knew I could trust you!" Reserves moved to cover the Republican rear, Voroshilov reorganised his own men, and the counterattack began forty-eight hours later.

Voroshilov and Tukhachevsky shared a belief in what would later be called 'deep penetration theory'. It resembled Germany's Hutierkrieg tactics which had shown their worth in the Great War and Danubia: cut through the enemy lines to wreck havoc in the rear. Tukhachevsky's ideas were better suited to a nation of peasant armies, cavalrymen, and endless steppe. Whereas the Germans concentrated fire on one small break-through point, the Russian commander believed in attacking on as wide a front as possible to prevent a proper reserve from forming. These principles had certainly been used before in the Russian Civil War, but military historians cite this counteroffensive as the seed from which deep penetration theory would later grow.

Pyotr Wrangel and his men were about to become the lab rats for a new experiment in military history.

Voroshilov attacked south at dawn on 17 September. On Tukachevsky's advice, he'd divided his force in two. The first group- based at the hamlet of Milove, at the very southern tip of his conquests- was to smash south towards Luhansk, but not to get bogged down in urban fighting. It was the action of moving south that mattered, Voroshilov had told his subordinates, the town was just a useful landmark. The second group had the more ambitious objective. Based a few miles northwest of Milove, it was to march due south, wrap around west of Luhansk, and keep going as far as possible. This would trap Wrangel behind two armies, leaving the Tsarists near-defenceless in eastern Ukraine.

For once, it worked. Wrangel had committed the same errors as Voroshilov- forging ahead without securing his flanks. However, he lacked Voroshilov's rear support and Tukhachevsky's strategic reserves. "The explosion to which we awoke on that day", recalled a Tsarist prisoner's memoirs, "told us what was coming. Something entirely outside our experience, something too large for our efforts, individual or collective, to push back." The Republican armies were imperfectly equipped, and tactical-level leadership varied, but it was nothing the Tsarists didn't face. Elan might not be a substitute for more tangible factors, but it gave the Republicans an edge over their foes on that day. Just as he'd forced Voroshilov to do, Wrangel halted his attack to patch up his flank. And just like Voroshilov's dismounted cavalrymen, they'd been given an impossible task. It wasn't courage that was lacking, but supplies and defensible positions. Focusing on the eastern Republican column gave the western one free rein and vice versa. Deciding it was hopeless, the Tsarist commander withdrew to Luhansk. With Wrangel pulling his men out west, ideally the city could hold out long enough for the main army to flee. Instead, just as Voroshilov and Tukhachevsky had planned, the western column blazed past and wrapped around his south, while the eastern one put the city under siege.

Wrangel was trapped.

The fearsome-looking Tsarist supremo, Baron Pyotr Wrangel

Though the Tsarist commander declared his resolve to fight on, he was pragmatic. Every day his isolated forces resisted would throw lives away to no end. The spectre of his men mutinying before the Republicans crushed his pocket kept him awake. Halfway through October, with the dreaded Russian winter winds blowing in from Siberia, Wrangel opened negotiations with Voroshilov. If the Republicans would spare his life, and those of his men, he'd lay down his arms. Voroshilov eagerly accepted, disarming the Tsarist soldiers before offering them a choice: spending the rest of the war in captivity, or joining the Republican army. Most chose the latter. Wrangel himself was taken to Samara, where he spent the rest of the war in a comfortable house arrest. His surrender was catastrophic for the Tsarists. Aside from the hefty Kharkov garrison, only politically-oriented scratch militias protected Ukraine.

Had Wrangel remained on the defensive, the Tsarist breadbasket would be much more secure.

***

The campaign in the Caucasus went less smoothly. Whereas Voroshilov was operating in a relatively small area, Semyon Budyonny's forces were spread out all across the Caucasus. Grozny was closer to Budyonny's start line than Kharkov to Voroshilov's, but Baku and Batumi might've been on the far end of the moon. Differences between the two commanders compounded this. Whereas Voroshilov knew how to translate a strategic goal into specific tactical and operational steps, all Budyonny saw was a name on a map, to be conquered... somehow. Budyonny's planning was less focussed than Voroshilov's, contained fewer specific instructions for field commanders, and most ominously, ignored the possibility of a major enemy counterattack. Brusilov had been planning to attack in the North Caucasus before his untimely death, and there were large (by Russian Civil War standards) reserves and supply dumps waiting for him. Though this was helpful, it also told the enemy where the blow would fall and cost him surprise.Blissfully ignorant, Semyon Budyonny sent his men ahead on 28 July 1920, and got off to a promising start. Tsarist commander Mikhail Drozdovsky was ready for him and made the same calculation as Wrangel. Road and rail links mattered; miles of empty steppe didn't. Rostov, Svyatoy (4), and Stavropol kept their garrisons, but the rest of the western Caucasus was stripped bare. Drozdovsky knew if he was wrong, the whole region would collapse, but believed the gamble was worth it. These reinforcements gave the Republicans hell on the road to Grozny.

Before the war, people had avoided Kochubey where possible. The destitute North Caucasian village, which seemed not to have changed since Napoleon, personified boredom and bleakness. Its one redeeming feature was that it lay en route to Baku. Now, that made it some of the most coveted land in Russia. Budyonny's men who hurled themselves across the Dagestani highlands met stiff defences. Drozdovsky wasn't about to cede the most important road junction for forty miles without a fight, and committed reserves only days into the fight. Unable to hack their way in, Budenny's infantry took great losses before the general had a plan.

Low-lying steppe turns to marsh as it nears the Caspian Sea. Believing it impenetrable, the Tsarists hadn't bothered fortifying it. Humans couldn't traverse it on foot and be ready to fight, but Budyonny had always believed in the power of the horse. On 14 August, a cavalry regiment saddled up and waded through the muck. It was miserable going, and many animals died of exhaustion. Yet, the Republicans emerged on terra firma the next day, with Kochubey's supply lines lying miles away like low-hanging fruit. Cavalry charged across the steppe, sabres swinging. The threat of encirclement forced Drozdovsky to pull troops from the fighting front. These men pieced the lines on the map room back together, but nothing could recapture the initiative. Two weeks after the cavalry maneouvre began, Budyonny's weary men entered Kochubey. Against the advice of his field commanders, Budenny continued the attack. Fighting had left the all-important road- the whole reason for going after Kochubey- useless. Supplying an advance south would be difficult until it was repaired. However, the general pushed his men on. Sacrificing initiative for something as petty as logistics was no way to win a war!

Hungry Republican troops had a few ideas as to what their commander should've done with his beloved "initiative". They needed to supplant their scant rations with requisitioning, but this not only wasted time which should've been spent fighting or marching, it alienated people from the Republican cause. When Tarumovka and Areshevka, both twenty-five miles south of Kochubey, fell at the end of September, Republican troops turned the place upside down looking not for political prisoners or wealth, but food.

"They appeared as starving men", wrote one Dagestani girl, "whose sole concern was to keep themselves alive so as to slaughter more men- this, evidently, being their main goal on this earth. Did they know that whatever they ate came at our expense, that we would go hungry to satisfy their needs? I do not know. But I am certain that those who realised this did not care. We were simply objects in the way, people to be marginalised or enslaved, so that the homeland could be made profitable... These Kerenskyite skeletons saw only the Romanov emblem on the patches of the other side. They were blind to the fact that the other men were just skeletons too... If this is what the homeland has come to, I envy the old. Better still, I envy the dead. Not to worry: I am sure I shall soon see them face to face."

Tukhachevsky summoned Budyonny to Volgograd on 20 September for a talking-to. He pulled no punches, contrasting Budenny's perfomance with Voroshilov's. While the latter had just trapped Wrangel's army with beautiful flexibility, Budyonny had captured only a few worthless villages while destroying his supply lines and hemorrhaging men. The Republican supremo was in a foul mood: he needed to monitor the fighting in eastern Ukraine and didn't have time to waste cleaning up after Budyonny. If he'd chosen the wrong subordinate, there were other men itching for the job. Tukachevsky pointed out similarities between the deep-penetration tactics Voroshilov had used against Wrangel and Budyonny's cavalry maneouvre through the swamps. He still had faith, but couldn't run on promises. If Budyonny could get the plan for his next attack on Tukhachevsky's desk in twenty-four hours, all would be well. True to form, Budenny presented his plan the next day. Massed cavalry, reinforced with armoured cars, would attack the west of the Tsarists, hoping to turn their flank. Republican forces could then advance down the road towards the Terek River; a natural stop line. "You had best not disappoint", the commander growled, but his tone softened. "This is reasonable, my man. Your men are brave and in good hands. Thus, I know you will not disappoint.

Tukhachevsky's real views are shown by a letter he wrote to Kerensky: it might be time for some infiltration behind the scenes in case things went awry.

Events moved too fast for Budyonny, though. Drozdovsky was about to seize the initiative and force him on the defensive. His coming offensive would go ahead, but it would end up as the disappointment Tukhachevsky had warned against. Part of this is attributable to Budyonny's own shortcomings. The general's very real valour and pursuit of the initative weren't matched by the lessons of the Great War. Budenny saw the glory of cavalry charges, blaring of trumpets, and proud uniforms as the essence of victory, not logistics, artillery, and training. Though he was hardly alone in this, his love of tradition and single-minded aggressiveness eventually became vices costing lives under his command and battlefield success. That dynamic certainly played out over the coming autumn's fighting. Another piece is more simple: the general's intelligence was poor. Agents behind the lines were valuable but couldn't work miracles, and simply hadn't realised Drozdovsky's true plans. Budenny had thus far battled a foe who, while resilient, was passive and defensive. We can only blame him for basing his offensive on this pattern with modern hindsight.

At first glance, Drozdovsky's actions thus far are hard to explain. Namely: he took no action. Tsarist troops fought valiantly but never attacked. Drozdovsky's intelligence must've had an idea how poor Budyonny's supply situation was, and the commander must've guessed that a counterattack would meet light resistance. Angry correspondence from Grand Duke Mikhailovich shows the Tsarist leaderhip's opinion. Why was Drozdovsky standing on the defensive? Taking punches wouldn't win the war, after all. Why had he watched passively as Wrangel's army collapsed? In fact, Drozdovsky had a simple plan: to let geography work for him. He saw the same map as his enemy. The Terek River was only a few miles south of the fighting front; the northermost peaks of the Caucasus Mountains weren't far behind. Grozny and Baku lay south of these prime obstacles. All he needed to do was not lose; Budenny had to hack through the mountains. Lavishing surplus manpower on such a simple defence would be wasteful. Far better to put those men to work.

For all his success against Pyotr Wrangel, Voroshilov had made a cardinal error: he'd left Rostov in Tsarist hands. The Black Sea port housed tens of thousands and controlled the mouth of the River Don. Prioritising the eastern oilfields above the port was reasonable, but letting the enemy build it into a redoubt was an error. In the days before Budenny's summons to Volgograd, Drozdovsky had begun reinforcing the port. If he played his cards right, he could smash the Republican position in the northwest Caucasus while Budenny's men bled on the Terek.

Drozdovsky quite reasonably waited till Budyonny struck south before moving. This enabled him to see just what his opponent had committed to the fight. Strange as it sounds, the force of his enemy's blow pleased him. Terek-Mekteb and Korneyvo, nearly fifty miles west of the main road south, were in enemy hands by the start of October. Meanwhile, Tsarist troops to the east faced renewed pressure. Drozdovsky feared enemy cavalry might slip across the Terek in the west or trap his men north of the river, but kept a cool head. His men followed orders and retreated across the river, demolishing the bridges behind them. As per their commander's plan, Budenny's cavalry in the west focussed on flanking the Tsarists in the east, not crossing the Terek independently. Ten days of fighting convinced Drozdovsky the enemy had failed (even if they didn't know it yet). The strategic reserve wouldn't be needed for emergencies in the east, and could go ahead with its attack.

Tsarist forces erupted from Rostov on 9 October. Though his armies were closer to Ukraine than the Caucasus, Drozdovsky was more interested in the latter. Ukraine was, at least temporarily, a lost cause- the North Caucasus wasn't. Drozdovsky put geography to work for him here, too. Rostov was ideal to attack from because it was where the Don met the sea. Control of it provided control of both banks of the great river. Highlands north of the city provided a natural line for the offensive to follow.

Twenty miles northeast of Rostov, Novocherkassk was the obvious first target. Tsarist forces advanced out of the suburb of Aksay up a minor tributary of the same name. Had they had to cross the Don, the Tsarists would've taken far longer to reach the city. As it was, they crossed the fifteen miles of gentle hills in two days while bombarding the town. The garrison resisted Drozdovsky's advance scouts, but once the main force arrived suddenly developed a newfound reverence for the House of Romanov. Most of the men followed their commander into the Tsarist ranks. Meanwhile, second-rate infantry advanced eastwards across the north bank of the Don, clearing out pockets of Republican resistance. Having opened the offensive well, Drozdovsky faced a key decision. Would he keep going north into the North Caucasian breadbasket, and hopefully driving a wedge between Ukraine and the Caucasus? Or would he turn his army southeast and march deep into the rear of the Republican armies lunging at the oilfields? Logistics dictated the former. Marching through endless miles of steppe, creating a wide-open flank, was a recipe for disaster. Besides, the forces to the east could fend for themselves well enough. Drozdovsky thus turned his force north, towards Shakty. The advance on that town was fundamentally the same as that on Novocherkassk: a few days of marching under constant light opposition, followed by a general surrender and mopping-up operations. Artillery blew away fears that the Republicans would fight a long delaying battle halfway between the towns at Persianovsky while bringing up reinforcements. One week of fighting had carried Tsarist arms forward over forty miles- and Drozdovsky had no intention of giving up yet.

The Tsarist commander had struck too far west to directly affect the men dying on the River Tivek. Losing Novocherkassk and Shakty didn't threaten to outflank units over four hundred miles away. Yet, Drozdovsky was thinking on a much larger scale. His move was not tactical, but operational. In a certain sense, his striking deep far from the active front resembled Tukhachevsky's burgeoning deep-penetration theories. Rapid movement to create a fresh crisis diverted Republican units and sucked up Tukhachevsky's reserves. More than that, Budyonny's focus on his offensive blinded him to the threat of enemy action elsewhere. Drozdovsky's move may have been tactically irrelevant to a far-flung theatre, but it achieved strategic surprise- and caught the foe off-guard. Budenny did exactly what Drozdovsky had hoped: he cancelled the offensive against the River Tivek line to throw every man he could at the new danger. The general order to halt went out at dusk on 18 October; reserves and rear-area units began marching to railway stations that night. When every hour seemed key to stemming the crisis in the west, having torn up every road and rail line in sight seemed foolish. Budyonny could cancel his offensive at the stroke of a pen, but he couldn't get the men where they needed to go. While officers muttered obscenities about the rail system in the North Caucasus, the enemy kept moving. Cancelling the offensive against the River Tivek line was reasonable, but it also ceded the initiative to the enemy. Tsarist troops counter-attacked at dawn on the 19th, having spent the night bringing up supplies unmolested. Despite Republican weakness, things didn't go as hoped. Tsarist numerical inferiority wasn't an issue on defence, but it limited their offensive capabilities. The local commander wisely called the attack off after eighteen hours lest he waste men needed to defend. Subsequently, the eastern Caucasus became a quiet sector: the Tsarists were happy to defend while the Republicans lacked the strength to push forward. With the frontline well north of the oilfields, Budyonny had failed.

Catastrophe in the west cast disappointment in the east into the shade. Drozdovsky's forces entered Ust-Donetskii on the last day of October, quickly fording a north-running tributary of the Don which might've held them up. Valiant Republican reserves did their best to stem the tide, mounting local counteroffensives from nearby villages. Much as he wanted to, Tukhachevsky decided against a full-scale counterattack. Voroshilov's forces in Eastern Ukraine needed to strike a difficult balance between pursuing their own offensive goals and preventing a Tsarist thrust northwest. Voroshilov was building up a tactical reserve to eventually move on Rostov, while Tukhachevsky was building his own reserve in the bend of the Don. Russia's endemic supply problems hampered the training and organising of these forces. Continued fighting in the north, the threats to the Central Volga from the west and east, and the political situation with Finland limited the ability of the Republicans to shift forces south. Tukhachevsky couldn't know when the next emergency would develop, and always needed some uncommitted strategic reserve. Trading space for time was demoralising, and looked bad on a map, but it was the best option. Drozdovsky, meanwhile, was fast becoming a victim of his own success. His men had advanced rapidly over well-defended terrain over the past month. Yet, the Russian Civil War was a hard time to be a logistician. Autumn raspitua turned roads into seas of mud which neither wheel nor hoof could penetrate. When their rations wore out, Drozdovsky's men turned to the land for sustenance. Worse was yet to come- the second winter of war. Though the North Caucasus is milder than Moscow or Petrograd, Drozdovsky knew he couldn't fight in the depths of December. He had to find a suitable stop line in the next month or face defeat.

There was an obvious target. Drozdovsky knew he could reach it, and Tukhachevsky was certain he could hold it. One thing was certain: thousands of lives rested on success or failure.

Comments?

(1) To be explained later on... doing so here would destroy the narrative.

(2) The region is rich in coal- no?

(3) Not OTL, but it seems entirely reasonable.

(4) Known, ironically enough, as Budyonnovsk on my map. I'm assuming it was named after the commander (which obviously wouldn't be the case in 1920), and Wikipedia says it was once known as Svyatoy, so... I'm going with that.

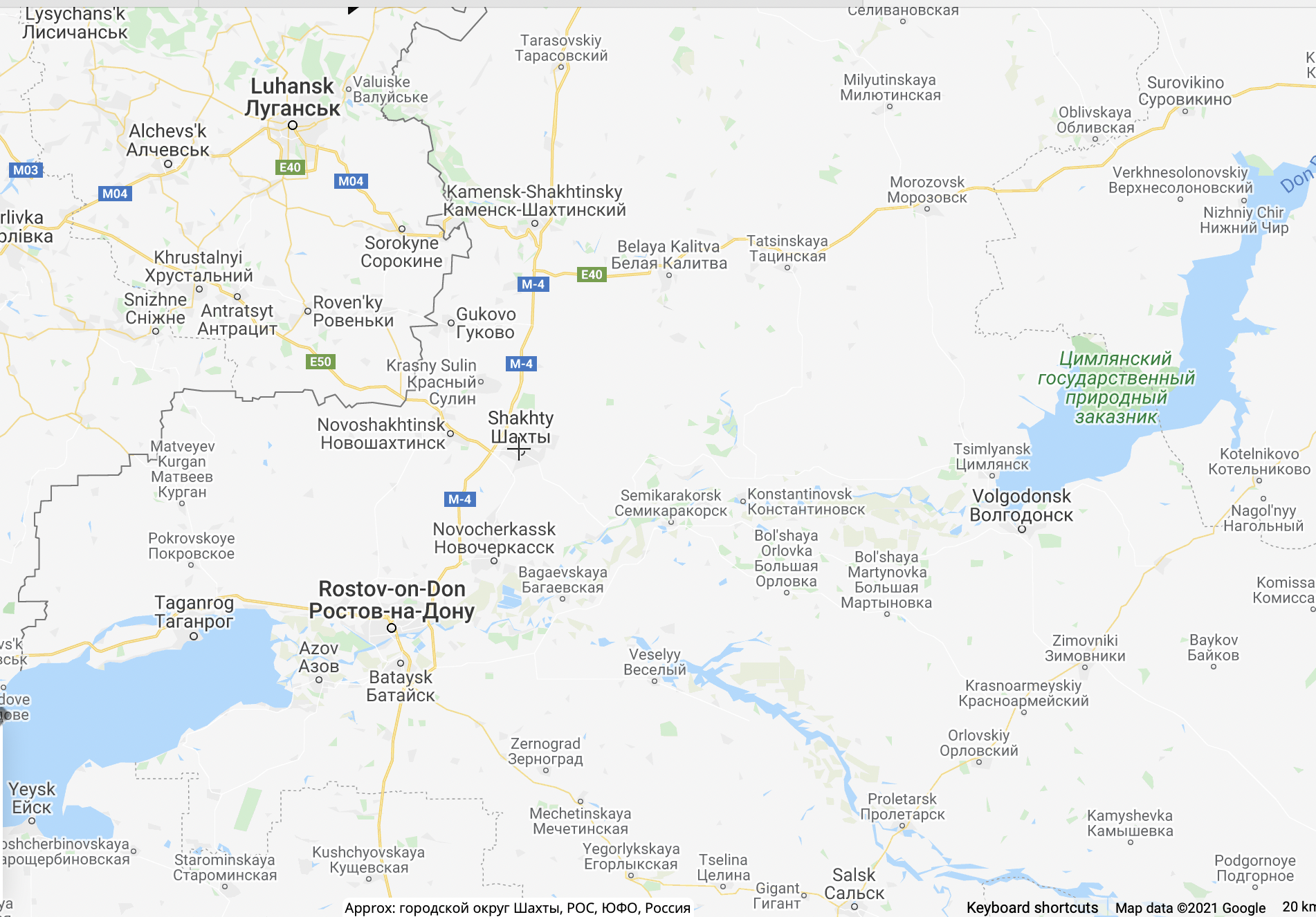

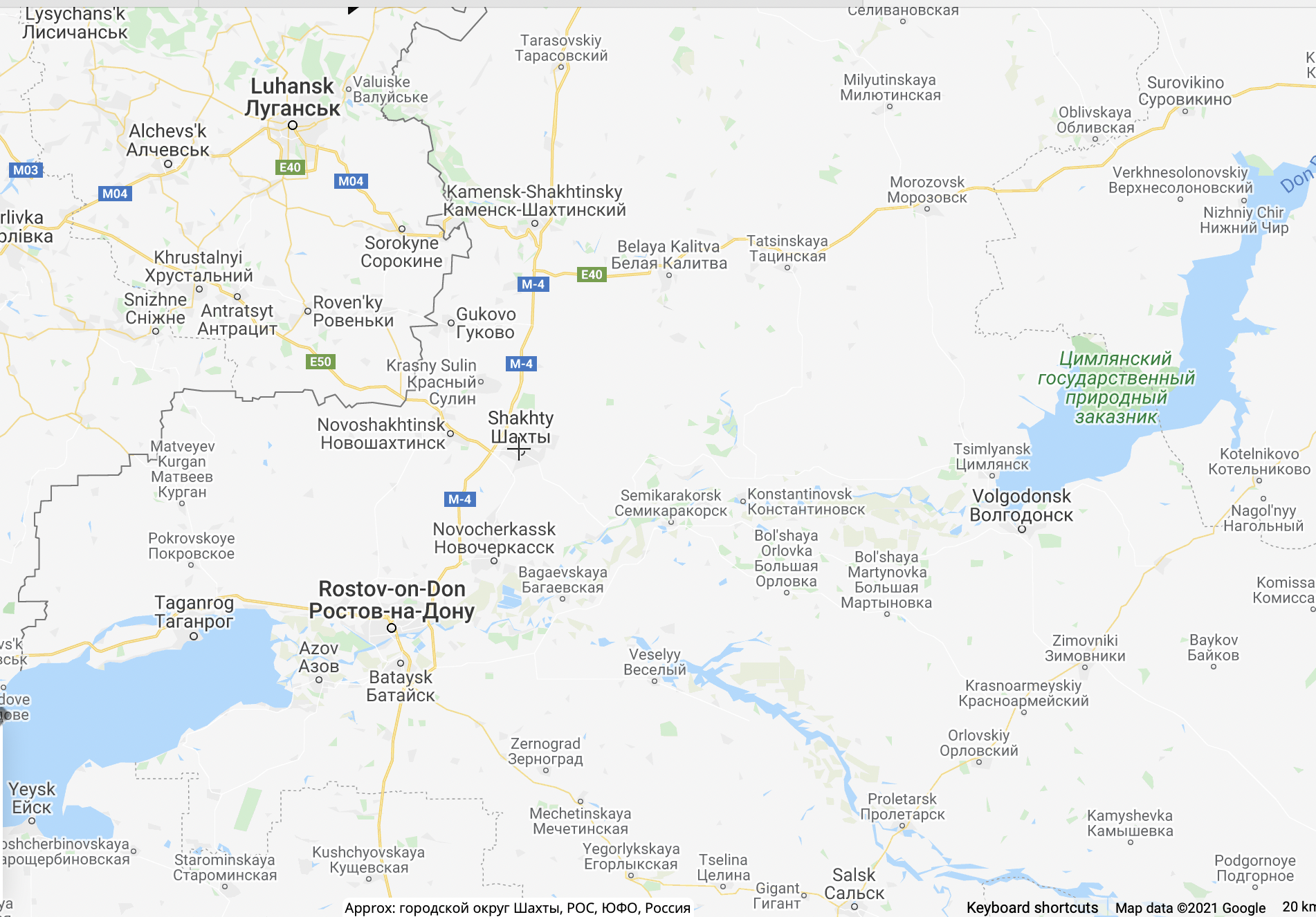

Maps for Chapter 56

Apologies for the low quality-- this was the best I could do. I used these maps to help write the above so hopefully they'll make everything a bit clearer.

#1: Frontlines in Eastern Ukraine

#2: Map of the area in the Caucasus where Budyonny attacks

#3: Map of the area in where Drozdovsky's attack goes in

#1: Frontlines in Eastern Ukraine

#2: Map of the area in the Caucasus where Budyonny attacks

#3: Map of the area in where Drozdovsky's attack goes in

ahmedali

Banned

Kaiser Wilhelm the Tenth

The chapter was very nice and I thank you very much for it

Finally, the fearsome Baron Wrangel appeared

It seems that the tsarist and republican parties received equal damage, especially the loss of Borislov weakened the republicans by losing a competent general like him.

I hope Wrangel gets out of his way

I find it still strange that the Ottomans and the Germans still did not attempt to intervene in the Russian Civil War.

The chapter was very nice and I thank you very much for it

Finally, the fearsome Baron Wrangel appeared

It seems that the tsarist and republican parties received equal damage, especially the loss of Borislov weakened the republicans by losing a competent general like him.

I hope Wrangel gets out of his way

I find it still strange that the Ottomans and the Germans still did not attempt to intervene in the Russian Civil War.

Getting some real strong "I love the smell of Napalm in the morning!" vibes off this fella."I remain spectacularly convinced of the value of tradition, my friends. Here, in the open steppe, has anyone called for more tanks, more artillery, more machine-guns? Nyet! Here, war is returned to the noble form of art it always was- bearing a greater resemblance to that used by our ancestors to eject Genghis Khan, than that used by the Germans in France. The noble cavalry sweep, friends, has won the day!"

-Semyon Budyonny

Oooh, colour me intrigued to see what's got the Fins in such a twist.

You know, at this point, Russia is more spanner now than works. But Brusilov's death did make me go "Ah shit!" which is a unique experience. For all his flaws, the man was certainly competent at executing orders. And it's yet another failure of propaganda in this blighted war. His replacement is...ah, interesting. 'The Red Napoleon' what a bloody nickname! And oh boy....red really is the case, isn't it? This is going to be fun, especially if you consider the 'unambitious' comment about the plan.Just as the Republicans prepared to attack, God threw a spanner in the works.

I'll say this for the Tsarists, this Wrangel seems to be a relatively sane general. I mean right up until the point where he wasn't, but hey, compared to some...It's interesting actually, my history class covered the Russian Civil War of OTL but in a very brief window between the rise and fall of the Tsar and the chaos of Stalin's regime. This is giving me a chance to learn all sorts of new figures, it's quite fascinating.

And this is an interesting story of both sides of the war having decent generals and generals who vastly overstep their boundaries. Certainly it is an interesting lesson in the art of war, presented skilfully and easy to follow. And once again, a desperate struggle to find a stopping point might prove the tipping point for this act in the theatre of war. Bring it on, I say!

Another grand chapter.

Belaya armiya, chorny baron...Tukhachevsky's offensive began on the first of August 1920. Over a million men, many of them peasant conscripts, stood behind a frontline half the length of the old German front. Conditions in the west largely resembled the old front. Four days after the attack began, Grand Duke Mikhailovich named Baron Pyotr Wrangel "Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Armies".

A shame to see Brusilov go; it stands to reason he will find commemoration for his competence ITTL as well as OTL. Yet his replacement being Tukhachevsky of all people makes for a fascinating twist in the story, both in terms of what it could mean for future Republican politics and in terms of the military action to come. If nothing else, the Red Napoleon squaring up against the Black Baron certainly a personality battle for the ages. It seems he came out on top here, but time will tell whether his prescient strategic mindset or his famous overaggression will define his part in the war more.

Budyonny did as can be expected to do, in so doing giving the Tsarists a fine new chance to act in the Caucasus and Pontic Steppe. This is roughly within Antonov's sphere of activity; given the renewed Republican presence on this front, one wonders whether he will take the opportunity to distinguish himself. I would reckon the outside world sees how much is at stake here, given that Baku was in this timeframe one of the world's most important centers of oil production. Given the resource importance and demographic characteristics of the area, it certainly smells like a good time for the Ottomans to intervene if they wish to do so.

Last edited:

The grandfather of deep battle is now the Republican supreme commander. If the smart money wasn't on them before, it is now.

Share: