Chapter 44: The Great Dive

***

“The German Economic Recession of 1921 – 1923 after the Great War was exceedingly fantastic in its proportion that had ever been seen in history. And that was saying something. During the American Revolutionary War, the American government issued continental moneys to finance their war of independence against Great Britain and these moneys only had 1/1000 of their nominal strength and value in practice. The French franc in 1798 was worthy 533 paper cash as well. But in Germany, at the end of the inflation, the value of the German Mark fell to such levels that 1 British Pound was worth 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 German Gold marks, when in 1915, 1 British Pound was worth 2.27 German Marks. This amazing depreciation of the currency robbed the German economy of any practical value. And it was catastrophic in its social, economic and political effects, and would lay the foundation for the German Revanchismus.

Inflation in Germany

The government of Chancellor Rosa Luxembourg had become increasingly politically disputed as the SDP and the USPD began to butt heads with one another over policy. The SPD was more moderate and was advocating a social democratic and social capitalism in their economic outlook, and the USPD was more pro-nationalization and pro-social economics. This state of affairs would soon boil over into the Reichstagg, as the government became frozen over the bitter debate about the reparations Germany owed the Entente and the USPD-SPD coalition was slowly starting to fragment before everyone’s eyes.

The foundation for the inflationary crisis began during the starting of the Great War, with the German government suspending the obligation of the Reichsbank from redeeming its notes in gold, and creating loan offices which could issue paper money as an advance on paper securities and goods, most importantly, the Imperial German government also empowered the German Central Banks to accept treasury bonds and bills as security for new issues of paper money. War loans were issued with supervision and then discounted at banks and loan offices and this made the basis of the future new paper currency of the German government. The increase of treasury bonds in the german government created a renewed amount of large debt in the German markets, and this led to the addition of a publically funded debt of 98 billion dollars in the German economy.

The British Blockade of Germany

From between 1915 – 1918, the German economy started to depreciate as an aftereffect of the British blockade, and as because of the less than good economic policies of the German government, however this had taken place only at a slow pace, which did not raise much eyebrows in the German government. The food situation was much more concerning for the Imperial government and subsequent republican government. However in 1919, the inflation situation became much more dangerous when the government began to keep prices at a lower level by various price control regulations to create a stable economy. This created the illusion of a powerful economy in Germany, however in reality the economy was being funded by unsourced debt, which was simply a disaster waiting to happen.

The German government also printed a lot of money to circulate more money in the market as a measure of price control, however the extra money printed in Germany was unsourced, and unloaded and backed up by nothing, and the circulation of these new cash’s was much less efficient than the German government was willing to admit. By early 1921, however the German stocks of raw material, which was financing the German economy, was starting to become exhausted. Large scale reparation payments could only be made by exporting the country’s manufactured goods, however the country had to purchase raw materials to produce such goods, which only added to the economic strain of the government. The raw materials had to pay in foreign currencies, and this turned the foreign exchange market against the Germans, as the German government lacked effective amounts of foreign currencies. This loss in confidence in the German Mark as a result, led to the depreciation of the Mark in relation to the Pounds, Franc and Dollars. Moreover, leftover stigma from the Great War meant that the British, French and Russian peoples were not eager to have produce that had the label ‘Made in Germany’ on them, and this situation only exacerbated the events that were to follow. Under this already depressing situation of the German Economy, the German government was forced to accept the Versailles Treaty and its terms of economic reparations to the Entente. The French and Russians in particular, having taken the brunt of the German attacks, and having bled white to defend their homelands, were eager to get the reparations and few among them showed any hesitation at the large reparations levied from a country already in depreciation. Luxemburg met with the French Foreign Minister in Luxembourg City in January 7, 1921, and stated bluntly that Germany did not have the means to pay the reparations, as Germany was basically broke at all levels of the economy.

The French were unrepentant and demanded that the second payment of the reparations in 1921 be conducted in a ‘coordinated and fruitful’ manner, which meant that France would not allow the Germans wiggle their way out of the reparations. Luxemburg reluctantly tried her hand at different economic policies, and began to buy considerable foreign currencies to pay off the reparations, and this only made the depreciation of the Mark even faster. 1 British Pound was already equal to 67 Marks by the starting of Luxemburg’s policy of borrowing foreign currencies.

On February 1, 1921, the German government paid their second due of the reparations, however now the German government was truly broke, and the economy had nothing to show for the massive amount of Pounds, Francs, Rubles and Dollars that the German government had loaned from banks throughout Europe. When worker riots broke out in the Rhineland after the issue of lowering standards of living in Germany as a result of the economic crisis, the market confidence in the German Mark finally collapsed, and the Mark’s value decreased by 40 fold on the 27th of February, 1921 (1 Pound = 2680 Marks) starting what would become known as the ‘Great Dive’ in the German Economy.

Chancellor Rosa Luxemburg

The political debate and power struggle between USPD and SPD only made things worse. Phillip Sheidemann, the Vice-Chancellor had the good of idea trying to partially nationalize the important industries of the country to stave off an economic crisis, however the USPD would not accept anything less than a complete nationalization of the economy at this time of economic depreciation and recession. The leader of the German conservative and right party, Rudolf Heinz also launched several protests against the German government itself, demanding a return to the Monarchy and the Imperial government, which led to the government starting to freeze again. The German government was proving to become increasingly unable to meet the demands of the country. Luxemburg did have good ideas to pursue re-localization and recovery in the German economy, but her own government and President Noske hampered her efforts to work together with the SPD to make the German economy run properly again. Luxemburg was disgusted at the partisan problem that the recession had become and she blamed the USPD for it largely, and she defected from the USPD on the 23rd of March, 1921 and to the SPD, which disrupted the balance of power in the USPD-SPD coalition government. This made several cabinet members of the German government from the USPD party resign from said cabinet in protest and out of the 15 ministries the German government had, only 7 was now functional with ministers at their head. The German government had effectively fallen, and this would only be the starting of the German Great Dive and the German Crisis.” Causes of the Second Great War – The Economy? © 2008 [1]

***

“At the starting of the Great War and the Balkan War, the Ottomans had been taking a very keen interest in their navy, by and large, and had in the past few years managed to gain a larger collection of warships which were used in the Balkan wars to some effect. However by 1921, the Ottoman Navy had become small again, and was now falling behind other middle powered Great Powers in the Great Game that was Great Power politics and geopolitics. At the starting of the year 1921, the Ottoman navy consisted of the following ships:-

The situation of the navy was considerably better than in 1911, in both equipment, training and size, as the navy was still quite modern, however, it was small. In comparison to the heavy hitter warships, the Ottomans had around ~70 gunboats and 10 minesweepers and minelayers as well. However, the Ottomans knew that they were lagging behind on other powers. The Russians were growing wary of the growing economic resurgence of the Ottoman Empire, and had started a rather large naval buildup in the Black Sea, and the Italians had ordered the creation of the first 6-6 Fleet program in the Red Fleet, which was now threatening the Ottomans from two sides. If the Ottomans ever found themselves at war with the Russians and Italians, the Ottomans were quite aware of the fact that they would be caught off-guard from a two-pronged naval attack in the Black Sea by the Russians and in the Mediterranean by the Italian Red Fleet. The Ottomans had managed to increase their economic influence and economic power, and the naval budget could be increased, though to a limit.

The two battlecruisers of the Suleiman Class were nearly finished and would replace the Barbaros Heyreddin and Turgut Reis by 1923, however other than that the Ottoman Navy had made no other expansionary or replacement moves, which was quite worrying for the Minister of Naval Affairs, Ciballi Mehmed Bey. Now old, and down for retirement by the end of the year, the Bey wanted to make sure that a last proper expansion of the navy happened under his reign as Minister of Naval Affairs. The Ottoman Grand Vizier, Ahmet Riza was much more busy with other matters of the state, and the Ottoman naval minister knew that he would have to gain the aid of another to gain the attention of the Grand Vizier. Admiral Sir Arthur Limpus, was the head of the British Naval Mission in the Ottoman Empire in 1921, and he was just the man that the Bey was looking for.

The Bey approached the British Admiral, and asked the man about the prices of the British ships that were being constructed in British seaports and dockyards. The Admiral, always eager to have British ships exported as a part of the British scheme to improve their economy after the Great War was intrigued by the questioning that was coming his way from the Ottoman Naval Minister. He broached the topic, and answered by telling the Bey that the British made Danae Class Light Cruisers were currently being listed as open to export. The naval minister hurried back to the government and tried to convince Riza that this was the opening that they needed. Riza was not so convinced, and pointed out that the current expansion and reformation of the military under the military education scheme was much more important than the navy. However, at this point, Mahmud Shevket Pasha, who was also listed for retirement by the end of the war, was also alarmed by the Ottoman lag in the navy, and agreed with his counterpart, and endorsed an expansion of the navy and increase in the naval budget. He also showed a lot of interest in the British built ‘Aircraft Carriers’ however that was a long way out of Ottoman naval capability for a good amount of time.

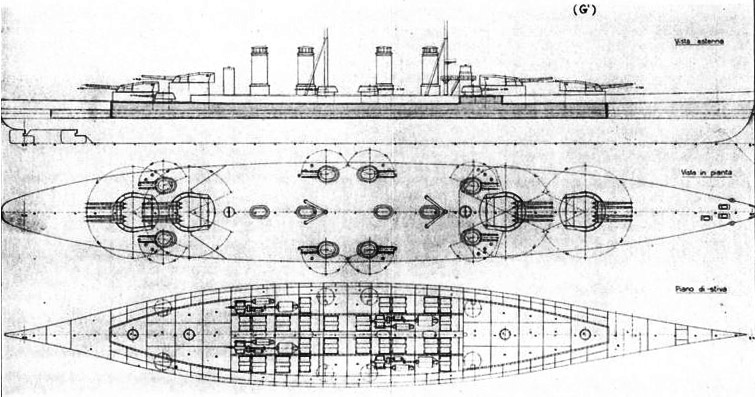

Blueprints of the Kaysar Class Battleships.

Ottoman naval engineers had been trying to come up with a new design for the vast majority of the past years, and on the 16th of February, 1921, gave the Ottoman Ministry of Naval Affairs with their blue print on, what they called as the Kaysar (Caesar) class Battleships. This battleship plan was on paper a 37,000 tonnes battleship. This was a postwar project that had radical hull improvement over previous battleships, with only a 50 mm deck armor and a less amount of anti-aircraft guns. The belt armored was 270 mm and around 300 mm on the turret faces. This battleship was also to carry sixteen 380 mm guns in four quad turrets and superfiring, which was a radical upgrade to the Barbaros Heyreddin. The guns of the Kaysar class were also equipped with an improved reloading system of 2 rounds per minute and a muzzle velocity of 820 meters per second with armor piercing shells. The secondary artillery was not in the typical barbettes, but in turrets, and in all sixteen, and of the 170 mm guns (7 inch) secondary armaments. Configuration of the eight twin turrets plus the 24 dual purpose rapid fire 102 mm guns, completed by many 40 mm Anti-Aircraft guns were to be the armament complement of the battleship. The ship, also had a noticeable lack of armor, to create more mobility and more firepower. This was a calculated move, as the naval battles of the Great War between the Royal Navy and the Imperial German Navy showed that speed was going to be a battle winner. Unknown to Ottoman naval engineers at the time, however shell dispersion would a consistent problem for the Kaysar Class. Nonetheless, this plan received the greenlight of the Ottoman government and 2 were ordered by the Ministry of Naval Affairs. Their shapes were laid down in Imperial Dockyards in Smyrna on the 29th of March, 1921. [2]

With the issue of the heavy battleships done, the lighter warships were to be spread through a period of 5 years to minimize cost. In doing so the Ottoman government knew that they would be able to reduce warship costs. For their destroyers, the Ottomans looked at the country of Greece, which was sporting American destroyers, and using them rather easily, and turned the American government as well. The Americans had since 1890 been constructing small gunboats and minelayers for the Ottoman Navy, but the Ottomans had never gone to the American government with an order of a real warship. The Americans were more favorable to loans to buy warships and armament and on the basis of periodical payment, the Ottomans negotiated the purchase of 8 Clemson Class destroyers from the American government. The Americans started to lay down the foundations for the destroyers, and payment for all of them was due to be paid by 1926, though the Ottomans began to pay in installment as early as March, 1921.

Similar to the Kaysar Class, the Ottomans were eager for their own indigenous submarines, as they had seen the havoc that the Germans had conducted against British shipping in the Great War with their powerful indigenous submarine industry. Ottoman Naval engineer, and prominent Ottoman engineer in general Georgios Stefanos unveiled his plan for the Derinokyanus Class Submarines (literally Deep Sea in Turkish). This submarine class was largely based on the French O’Byrne Class Submarines, and shared many characteristics with it. The submarine was to have a displacement of 342 surface tonnes, 52.4 meters long, with a beam and draught that was 4.7 meters and 2.7 meters long respectively. With an engine containing two shafts, the submarine would have a theoretical speed of 14 knots, and a range of 1,850 nautical range. Its armament consisted of four 450 mm torpedo tubes and one 47 mm deck gun. [3] More importantly for the Ottomans, this submarine was going to be cheap, and many other powers began to look into it with interest. On the 31st of March, 1921, when the Ottoman government agreed to construct 6 Derinokyanus Class submarines, the Spanish government approached the Ottomans with the possibility of building 4 submarines of the same class for the Spanish navy. Negotiations would start the next day.

The French O'Bryne Submarines, which inspired the aforementioned Ottoman Submarines.

Finally, the Ottomans contacted the British Embassy and started to negotiate with it for 3 Danae Class Light Cruisers. Unlike the Americans, the British were more uptight about installment payment, however they agreed to a time period of 2 years for the total payment of the three ships.

This naval expansion program which was named the 1921 Naval Plan was a plan that was expensive, and rather costly, and overshot the naval budget by a good amount, however thankfully the Ottomans managed to cover money for it through small loans from dispersed banks. It would lay the foundation for the Ottoman Navy during the Second Great War.” The Ottoman Navy: A Prestigious and Bumpy History © 2016

***

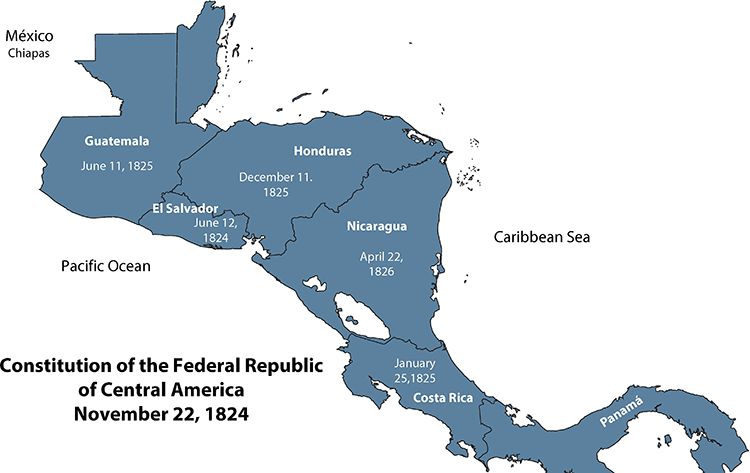

“On the 21st of January 1921, the head of states of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Costa Rica signed on the Treaty of San Jose, with one another, recognizing the project of the ‘Federal Republic of Central America’. The previous two attempts to create a unified Central America had failed, horribly, with the first attempt ending in civil war and the separation of the countries, and the second attempt falling apart in 2 years. However this time, the governments of the respective countries were eager to make things work the third time around. Third Times the Charm was something that many subscribed to it seems.

President Emiliano Chamorro Vargas of Nicaragua

President Emiliano Chamorro Vargas of Nicaragua did join the presidents to sign the treaty in San Jose, however he had no support from the Nicaraguan National Assembly, which was dominated by the radical traditionalist faction of the Conservative Party of Nicaragua. The Liberal Party, which controlled a third of the National Assembly supported the federal project, however due to the vagueness of the Treaty, even they were suspicious of the third Central American project. Nonetheless, the Liberals, led by Jose Esteban Gonzalez informed Vargas, that if the federal project kept the autonomy of Nicaragua as a sovereign right, then they would support of the project. Vargas himself was in support of such a project, partially due to his oligarchic origins, which would benefit from expanding their family business into the other Central American countries. Vargas was at the least able to convince the National Assembly to allow him to go to the Convention of San Salvador, where the countries involved were going to iron out of the federal project.

President Jorge Melendez of El Salvador officially extended the invitations to all of the head of states involved to come to the capital of El Salvador on the 25th of March, 1921 to iron out what would become the federal process of the Central American Republic. President Emilio Vargas of Nicaragua accepted extremely fast, and the President of Costa Rica, Julio Acosta Garcia accepted pretty quickly as well. Carlos Herrera, President of Guatemala was slightly suspicious of the quick succession to the Treaty of San Jose, however he too agreed to come in good order. Rafael Lopez Gutierrez, the fiercest proponent of the Central American Dream among the five countries accepted the offer easily as well. As five presidents were involved in the decision making process, the security of the capital of El Salvador on the days of the convention was fierce, and the country’s military was deployed to make sure none of the usual banana republic shenanigans happened during the convention.

The Central American Republic of 1821-46 was what the Convention hoped to restore minus Panama.

The San Salvador Convention which took place from the 25th of March to the 29th of March, 1921, was a heated affair, as the five presidents argued for differing degrees of autonomy from a centralized unitary state all the way to a loose union of nations. The convention almost ended on the 27th when President Herrerra of Guatemala threatened to withdraw from the project in anger about his proposals being shot down, however cooler heads, plus the French, British, American and Mexican delegations present in the convention intervening to make the head of states look at the state of matters with more cooler heads allowed the convention to go on ahead. By the end of the convention, a good amount of things were agreed upon. The basic of these agreements were:-

***

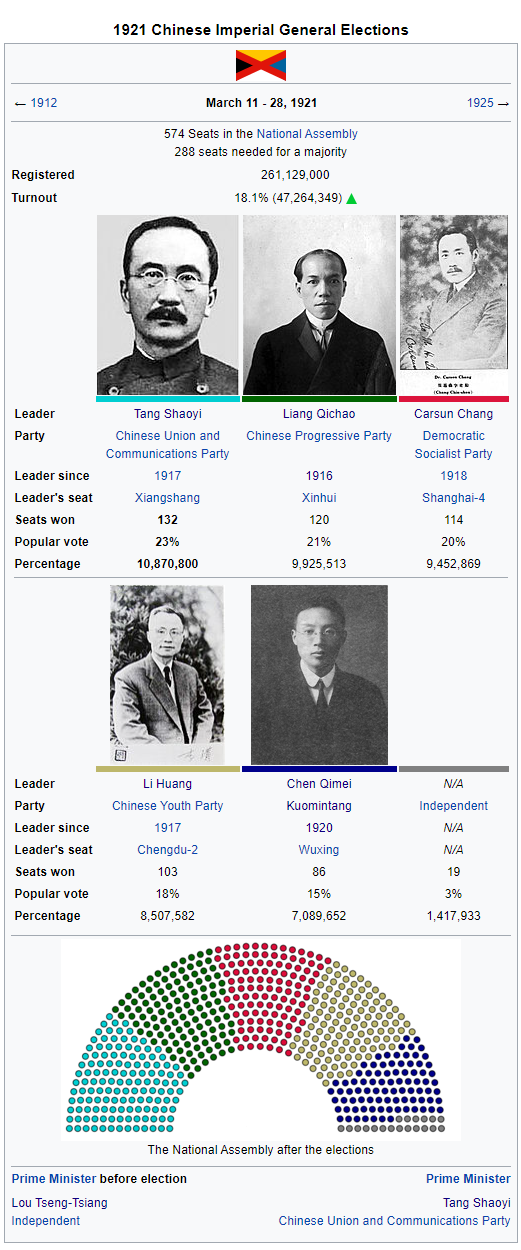

“The Constitutional Acts of China 1920 revived the National Assembly of China which was suspended by Yuan Shikhai in 1916, and the Hongxian Emperor, Yuan Keding, was more willing than his father to ascertain his rule under at least a semi-democratic government. The Constitutional Acts divided power between the Prime Minister, Emperor and the National Assembly which each player receiving 1/3 of the total executive power. As a result, the Hongxian Emperor opened the first National Assembly (largely consisting of independents) on the 17th of October, 1920 declaring that a general election for the 168 seat Senate and 406 Seat House of Representatives would take place the next year. The electoral system of the elections had their seats broken down into electoral districts designed for each county and equivalent of China. Women had received partial voting rights in the election as well, with Women with high incomes allowed to vote according to the new constitution of China.

The Hongxian Emperor

There was also the matter that Lou Tseng-Tsiang, the Prime Minister of the Hongxian Emperor was becoming increasingly unpopular among the Chinese populace due to his Roman Catholicism faith. Under the Chinese Empire, China was undergoing a renaissance of Chinese culture, and that included traditional Chinese folk religions, Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. Christians in China were generally looked down upon, with the memory of the Taiping Rebellion still fresh in the minds of many.

As the date of the election was announced, the major political groups of the Empire began to coalesces with one another to establish proper political parties. The strongest of these political ‘pressure groups’ which had been legal before the 1920 Constitution was the Communications Clique. The Clique was a powerful interest group consisting of politicians, bureaucrats, technocrats, businessmen, engineers and labour unionists. It was a centrist political group that was succeeded by the Chinese Union and Communications Party (CUCP). CUCP elected Tang Shaoyi, the former Minister of Mail and Communications of the Imperial Cabinet under the Qing as their leader. He was a moderate and charismatic leader, and was a very vocal pro-democracy and pro-constitutional monarchism politician in China. The CUCP based its foundations on basic technocratic ideals based in centrism.

Liang Qichao

In 1916, the Chinese Progressive Party was dissolved by imperial decree of Yuan Shikhai. As highlighted before this, only political pressure groups, and not parties were allowed before the 1920 Constitution. The party was succeeded by the Research Clique, led by Liang Qichao as its leader. The Research Clique was instrumental in pushing the Chinese into the Great War against the Germans, and the clique had the ear of the Hongxian Emperor. Many constitutional monarchists from Su Yat-Sen’s Constitutional Protection Movement also defected over to the clique after the successive end of the Great War, which allowed the clique to gain some modicum of power. After the constitution of 1920, the Clique was dissolved and the Progressive Party was reinstated once again. Liang Qichao continued to lead the party, and based the party’s foundation in solid liberal conservatism.

Considering outright republican parties and outright communist/socialist parties in China were banned during this time, the leftwing coalition of politicians in China grouped together into one loose union called the China Democratic Socialist Party, which was led by Carsun Chang. Chang, a Shanghai native by birth, was also a labour unionist, and he retained ambivalent tones to the monarchy in his political outlook to not gain the ire of the Imperial government. Its inspiration was the Social Democratic Parties of Scandinavia and advocated for market capitalism and greater social reforms in China, though it remained supportive of the Imperial government to avoid arrests.

The Chinese Youth Party founded by Li Huang, a philosopher and lawyer by trade, was the typical right wing party of the country that was focused on Chinese nationalism. It consisted of several former veterans as well, and made the remaining concessions in China a focal part of their policy whilst remaining fiscally conservative in their economic outlook. Majority of the Kuomintang refused to take part in the election due to their republican outlook, but many pro-constitutional monarchical members of the party, led by Chen Qimei took part in the elections under the name of Kuomintang (Pro-Government). Sun Yat-Sen would denounce the members of his party taking part in the election, casting them out of the party from his headquarters in the British Concession in Shanghai, however the Imperial Government would continue to recognize the Chen faction of the Kuomintang as the legitimate faction of the party.

During the elections, the CUCP managed to gain the largest share of the vote and seats, however remained far away from an actual majority. However Laing Qichao agreed to give the CUCP Confidence and Supply with his own Progressive Party, which allowed the CUCP to form a minority government in the National Assembly. In the resulting contingent elections, Tang Shaoyi, became the first partisan Prime Minister of the Restored Imperial Chinese state.” Chinese Electoral History © ImpChinaGov.net

***

---

[1] – Economic information from The German Hyperinflation and the Demand for Money Revisited by P. Michael

[2] – Kaysar ship based on the Progetto G Class Battleship of Italy otl that was not made.

[3] – based on characteristics of the French O’Byrne Class Submarines otl.

***

“The German Economic Recession of 1921 – 1923 after the Great War was exceedingly fantastic in its proportion that had ever been seen in history. And that was saying something. During the American Revolutionary War, the American government issued continental moneys to finance their war of independence against Great Britain and these moneys only had 1/1000 of their nominal strength and value in practice. The French franc in 1798 was worthy 533 paper cash as well. But in Germany, at the end of the inflation, the value of the German Mark fell to such levels that 1 British Pound was worth 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 German Gold marks, when in 1915, 1 British Pound was worth 2.27 German Marks. This amazing depreciation of the currency robbed the German economy of any practical value. And it was catastrophic in its social, economic and political effects, and would lay the foundation for the German Revanchismus.

Inflation in Germany

The government of Chancellor Rosa Luxembourg had become increasingly politically disputed as the SDP and the USPD began to butt heads with one another over policy. The SPD was more moderate and was advocating a social democratic and social capitalism in their economic outlook, and the USPD was more pro-nationalization and pro-social economics. This state of affairs would soon boil over into the Reichstagg, as the government became frozen over the bitter debate about the reparations Germany owed the Entente and the USPD-SPD coalition was slowly starting to fragment before everyone’s eyes.

The foundation for the inflationary crisis began during the starting of the Great War, with the German government suspending the obligation of the Reichsbank from redeeming its notes in gold, and creating loan offices which could issue paper money as an advance on paper securities and goods, most importantly, the Imperial German government also empowered the German Central Banks to accept treasury bonds and bills as security for new issues of paper money. War loans were issued with supervision and then discounted at banks and loan offices and this made the basis of the future new paper currency of the German government. The increase of treasury bonds in the german government created a renewed amount of large debt in the German markets, and this led to the addition of a publically funded debt of 98 billion dollars in the German economy.

The British Blockade of Germany

From between 1915 – 1918, the German economy started to depreciate as an aftereffect of the British blockade, and as because of the less than good economic policies of the German government, however this had taken place only at a slow pace, which did not raise much eyebrows in the German government. The food situation was much more concerning for the Imperial government and subsequent republican government. However in 1919, the inflation situation became much more dangerous when the government began to keep prices at a lower level by various price control regulations to create a stable economy. This created the illusion of a powerful economy in Germany, however in reality the economy was being funded by unsourced debt, which was simply a disaster waiting to happen.

The German government also printed a lot of money to circulate more money in the market as a measure of price control, however the extra money printed in Germany was unsourced, and unloaded and backed up by nothing, and the circulation of these new cash’s was much less efficient than the German government was willing to admit. By early 1921, however the German stocks of raw material, which was financing the German economy, was starting to become exhausted. Large scale reparation payments could only be made by exporting the country’s manufactured goods, however the country had to purchase raw materials to produce such goods, which only added to the economic strain of the government. The raw materials had to pay in foreign currencies, and this turned the foreign exchange market against the Germans, as the German government lacked effective amounts of foreign currencies. This loss in confidence in the German Mark as a result, led to the depreciation of the Mark in relation to the Pounds, Franc and Dollars. Moreover, leftover stigma from the Great War meant that the British, French and Russian peoples were not eager to have produce that had the label ‘Made in Germany’ on them, and this situation only exacerbated the events that were to follow. Under this already depressing situation of the German Economy, the German government was forced to accept the Versailles Treaty and its terms of economic reparations to the Entente. The French and Russians in particular, having taken the brunt of the German attacks, and having bled white to defend their homelands, were eager to get the reparations and few among them showed any hesitation at the large reparations levied from a country already in depreciation. Luxemburg met with the French Foreign Minister in Luxembourg City in January 7, 1921, and stated bluntly that Germany did not have the means to pay the reparations, as Germany was basically broke at all levels of the economy.

The French were unrepentant and demanded that the second payment of the reparations in 1921 be conducted in a ‘coordinated and fruitful’ manner, which meant that France would not allow the Germans wiggle their way out of the reparations. Luxemburg reluctantly tried her hand at different economic policies, and began to buy considerable foreign currencies to pay off the reparations, and this only made the depreciation of the Mark even faster. 1 British Pound was already equal to 67 Marks by the starting of Luxemburg’s policy of borrowing foreign currencies.

On February 1, 1921, the German government paid their second due of the reparations, however now the German government was truly broke, and the economy had nothing to show for the massive amount of Pounds, Francs, Rubles and Dollars that the German government had loaned from banks throughout Europe. When worker riots broke out in the Rhineland after the issue of lowering standards of living in Germany as a result of the economic crisis, the market confidence in the German Mark finally collapsed, and the Mark’s value decreased by 40 fold on the 27th of February, 1921 (1 Pound = 2680 Marks) starting what would become known as the ‘Great Dive’ in the German Economy.

Chancellor Rosa Luxemburg

The political debate and power struggle between USPD and SPD only made things worse. Phillip Sheidemann, the Vice-Chancellor had the good of idea trying to partially nationalize the important industries of the country to stave off an economic crisis, however the USPD would not accept anything less than a complete nationalization of the economy at this time of economic depreciation and recession. The leader of the German conservative and right party, Rudolf Heinz also launched several protests against the German government itself, demanding a return to the Monarchy and the Imperial government, which led to the government starting to freeze again. The German government was proving to become increasingly unable to meet the demands of the country. Luxemburg did have good ideas to pursue re-localization and recovery in the German economy, but her own government and President Noske hampered her efforts to work together with the SPD to make the German economy run properly again. Luxemburg was disgusted at the partisan problem that the recession had become and she blamed the USPD for it largely, and she defected from the USPD on the 23rd of March, 1921 and to the SPD, which disrupted the balance of power in the USPD-SPD coalition government. This made several cabinet members of the German government from the USPD party resign from said cabinet in protest and out of the 15 ministries the German government had, only 7 was now functional with ministers at their head. The German government had effectively fallen, and this would only be the starting of the German Great Dive and the German Crisis.” Causes of the Second Great War – The Economy? © 2008 [1]

***

“At the starting of the Great War and the Balkan War, the Ottomans had been taking a very keen interest in their navy, by and large, and had in the past few years managed to gain a larger collection of warships which were used in the Balkan wars to some effect. However by 1921, the Ottoman Navy had become small again, and was now falling behind other middle powered Great Powers in the Great Game that was Great Power politics and geopolitics. At the starting of the year 1921, the Ottoman navy consisted of the following ships:-

Dreadnoughts (2):

Yavuz Selim, Sultan Osmaniye (All Orion Class Dreadnoughts)

Battleships (2):

Barbaros Heyreddin, Turgut Reis (All German Made)

Light Cruisers (7):

Zafer, Kosova, Fethiye, Sadiye, Hamidiye, Mediciye, Bert-i-Satvet (4 Town Class Cruisers, 3 Miscellaneous)

Submarines (6)

U-1, U-2, U-3, U-5, U-7, U-10 (U-43 Austrohungarian Class Submarines)

Destroyers (16):

Samsun, Yarhisar, Tasoz, Basra, Sinop, Izmir, Bursa, Erdine, Peyk-I-Sevket, Mehmed II, Umar II, Mansure, Lubnan, Zuhai, Fettah, Mahmud II

The situation of the navy was considerably better than in 1911, in both equipment, training and size, as the navy was still quite modern, however, it was small. In comparison to the heavy hitter warships, the Ottomans had around ~70 gunboats and 10 minesweepers and minelayers as well. However, the Ottomans knew that they were lagging behind on other powers. The Russians were growing wary of the growing economic resurgence of the Ottoman Empire, and had started a rather large naval buildup in the Black Sea, and the Italians had ordered the creation of the first 6-6 Fleet program in the Red Fleet, which was now threatening the Ottomans from two sides. If the Ottomans ever found themselves at war with the Russians and Italians, the Ottomans were quite aware of the fact that they would be caught off-guard from a two-pronged naval attack in the Black Sea by the Russians and in the Mediterranean by the Italian Red Fleet. The Ottomans had managed to increase their economic influence and economic power, and the naval budget could be increased, though to a limit.

The two battlecruisers of the Suleiman Class were nearly finished and would replace the Barbaros Heyreddin and Turgut Reis by 1923, however other than that the Ottoman Navy had made no other expansionary or replacement moves, which was quite worrying for the Minister of Naval Affairs, Ciballi Mehmed Bey. Now old, and down for retirement by the end of the year, the Bey wanted to make sure that a last proper expansion of the navy happened under his reign as Minister of Naval Affairs. The Ottoman Grand Vizier, Ahmet Riza was much more busy with other matters of the state, and the Ottoman naval minister knew that he would have to gain the aid of another to gain the attention of the Grand Vizier. Admiral Sir Arthur Limpus, was the head of the British Naval Mission in the Ottoman Empire in 1921, and he was just the man that the Bey was looking for.

The Bey approached the British Admiral, and asked the man about the prices of the British ships that were being constructed in British seaports and dockyards. The Admiral, always eager to have British ships exported as a part of the British scheme to improve their economy after the Great War was intrigued by the questioning that was coming his way from the Ottoman Naval Minister. He broached the topic, and answered by telling the Bey that the British made Danae Class Light Cruisers were currently being listed as open to export. The naval minister hurried back to the government and tried to convince Riza that this was the opening that they needed. Riza was not so convinced, and pointed out that the current expansion and reformation of the military under the military education scheme was much more important than the navy. However, at this point, Mahmud Shevket Pasha, who was also listed for retirement by the end of the war, was also alarmed by the Ottoman lag in the navy, and agreed with his counterpart, and endorsed an expansion of the navy and increase in the naval budget. He also showed a lot of interest in the British built ‘Aircraft Carriers’ however that was a long way out of Ottoman naval capability for a good amount of time.

Blueprints of the Kaysar Class Battleships.

Ottoman naval engineers had been trying to come up with a new design for the vast majority of the past years, and on the 16th of February, 1921, gave the Ottoman Ministry of Naval Affairs with their blue print on, what they called as the Kaysar (Caesar) class Battleships. This battleship plan was on paper a 37,000 tonnes battleship. This was a postwar project that had radical hull improvement over previous battleships, with only a 50 mm deck armor and a less amount of anti-aircraft guns. The belt armored was 270 mm and around 300 mm on the turret faces. This battleship was also to carry sixteen 380 mm guns in four quad turrets and superfiring, which was a radical upgrade to the Barbaros Heyreddin. The guns of the Kaysar class were also equipped with an improved reloading system of 2 rounds per minute and a muzzle velocity of 820 meters per second with armor piercing shells. The secondary artillery was not in the typical barbettes, but in turrets, and in all sixteen, and of the 170 mm guns (7 inch) secondary armaments. Configuration of the eight twin turrets plus the 24 dual purpose rapid fire 102 mm guns, completed by many 40 mm Anti-Aircraft guns were to be the armament complement of the battleship. The ship, also had a noticeable lack of armor, to create more mobility and more firepower. This was a calculated move, as the naval battles of the Great War between the Royal Navy and the Imperial German Navy showed that speed was going to be a battle winner. Unknown to Ottoman naval engineers at the time, however shell dispersion would a consistent problem for the Kaysar Class. Nonetheless, this plan received the greenlight of the Ottoman government and 2 were ordered by the Ministry of Naval Affairs. Their shapes were laid down in Imperial Dockyards in Smyrna on the 29th of March, 1921. [2]

With the issue of the heavy battleships done, the lighter warships were to be spread through a period of 5 years to minimize cost. In doing so the Ottoman government knew that they would be able to reduce warship costs. For their destroyers, the Ottomans looked at the country of Greece, which was sporting American destroyers, and using them rather easily, and turned the American government as well. The Americans had since 1890 been constructing small gunboats and minelayers for the Ottoman Navy, but the Ottomans had never gone to the American government with an order of a real warship. The Americans were more favorable to loans to buy warships and armament and on the basis of periodical payment, the Ottomans negotiated the purchase of 8 Clemson Class destroyers from the American government. The Americans started to lay down the foundations for the destroyers, and payment for all of them was due to be paid by 1926, though the Ottomans began to pay in installment as early as March, 1921.

Similar to the Kaysar Class, the Ottomans were eager for their own indigenous submarines, as they had seen the havoc that the Germans had conducted against British shipping in the Great War with their powerful indigenous submarine industry. Ottoman Naval engineer, and prominent Ottoman engineer in general Georgios Stefanos unveiled his plan for the Derinokyanus Class Submarines (literally Deep Sea in Turkish). This submarine class was largely based on the French O’Byrne Class Submarines, and shared many characteristics with it. The submarine was to have a displacement of 342 surface tonnes, 52.4 meters long, with a beam and draught that was 4.7 meters and 2.7 meters long respectively. With an engine containing two shafts, the submarine would have a theoretical speed of 14 knots, and a range of 1,850 nautical range. Its armament consisted of four 450 mm torpedo tubes and one 47 mm deck gun. [3] More importantly for the Ottomans, this submarine was going to be cheap, and many other powers began to look into it with interest. On the 31st of March, 1921, when the Ottoman government agreed to construct 6 Derinokyanus Class submarines, the Spanish government approached the Ottomans with the possibility of building 4 submarines of the same class for the Spanish navy. Negotiations would start the next day.

The French O'Bryne Submarines, which inspired the aforementioned Ottoman Submarines.

Finally, the Ottomans contacted the British Embassy and started to negotiate with it for 3 Danae Class Light Cruisers. Unlike the Americans, the British were more uptight about installment payment, however they agreed to a time period of 2 years for the total payment of the three ships.

This naval expansion program which was named the 1921 Naval Plan was a plan that was expensive, and rather costly, and overshot the naval budget by a good amount, however thankfully the Ottomans managed to cover money for it through small loans from dispersed banks. It would lay the foundation for the Ottoman Navy during the Second Great War.” The Ottoman Navy: A Prestigious and Bumpy History © 2016

***

“On the 21st of January 1921, the head of states of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Costa Rica signed on the Treaty of San Jose, with one another, recognizing the project of the ‘Federal Republic of Central America’. The previous two attempts to create a unified Central America had failed, horribly, with the first attempt ending in civil war and the separation of the countries, and the second attempt falling apart in 2 years. However this time, the governments of the respective countries were eager to make things work the third time around. Third Times the Charm was something that many subscribed to it seems.

President Emiliano Chamorro Vargas of Nicaragua

President Emiliano Chamorro Vargas of Nicaragua did join the presidents to sign the treaty in San Jose, however he had no support from the Nicaraguan National Assembly, which was dominated by the radical traditionalist faction of the Conservative Party of Nicaragua. The Liberal Party, which controlled a third of the National Assembly supported the federal project, however due to the vagueness of the Treaty, even they were suspicious of the third Central American project. Nonetheless, the Liberals, led by Jose Esteban Gonzalez informed Vargas, that if the federal project kept the autonomy of Nicaragua as a sovereign right, then they would support of the project. Vargas himself was in support of such a project, partially due to his oligarchic origins, which would benefit from expanding their family business into the other Central American countries. Vargas was at the least able to convince the National Assembly to allow him to go to the Convention of San Salvador, where the countries involved were going to iron out of the federal project.

President Jorge Melendez of El Salvador officially extended the invitations to all of the head of states involved to come to the capital of El Salvador on the 25th of March, 1921 to iron out what would become the federal process of the Central American Republic. President Emilio Vargas of Nicaragua accepted extremely fast, and the President of Costa Rica, Julio Acosta Garcia accepted pretty quickly as well. Carlos Herrera, President of Guatemala was slightly suspicious of the quick succession to the Treaty of San Jose, however he too agreed to come in good order. Rafael Lopez Gutierrez, the fiercest proponent of the Central American Dream among the five countries accepted the offer easily as well. As five presidents were involved in the decision making process, the security of the capital of El Salvador on the days of the convention was fierce, and the country’s military was deployed to make sure none of the usual banana republic shenanigans happened during the convention.

The Central American Republic of 1821-46 was what the Convention hoped to restore minus Panama.

The San Salvador Convention which took place from the 25th of March to the 29th of March, 1921, was a heated affair, as the five presidents argued for differing degrees of autonomy from a centralized unitary state all the way to a loose union of nations. The convention almost ended on the 27th when President Herrerra of Guatemala threatened to withdraw from the project in anger about his proposals being shot down, however cooler heads, plus the French, British, American and Mexican delegations present in the convention intervening to make the head of states look at the state of matters with more cooler heads allowed the convention to go on ahead. By the end of the convention, a good amount of things were agreed upon. The basic of these agreements were:-

- The creation of a ‘Federal Republic of Central America’.

- The Federal Union to consist of the Republic of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica and Nicaragua

- The Federal System of the Union would be based on the recognition of the sovereign autonomy of all the nations involved in the project.

- The union to have a unicameral legislature called the Federal Diet, which would be elected by the people.

- The country to be a semi-presidential parliamentary federal republic.

- The federal diet to have powers based on the concepts of public debt and property, trade/commercial regulation, unemployment insurance, direct/indirect taxation, postal service, census/statistics, defense, navigation and shipping, quarantine in times of pandemic, sea coast and inland fisheries, ferries, currency/coinage, banking and paper money, weights and measures, bankruptcy, patents, copyrights, citizenship, marriage and divorce, criminal law and procedure, penitentiaries, and federal projects connecting boundaries of every Nation State within the Federal Union with one another.

- The legislatures of the Nation States within the Federal Union to have powers over direct taxation in the state, management of the public lands, prisons, hospitals, municipalities, formalization of marriage, property and civil rights, administration of civil justice, education, company rights, natural resources, matters of local nature, and the right to secede from the union if 4/5 of the legislature vote in favor of it after a subnational referendum in favor of it.

- Issues such immigration/emigration, and national food produce and agriculture to be issues that will be under the concurrent authority of the Federal Diet and the Subnational Legislatures.

- The position of President of Central America to be created, whilst being separate from the positions of Presidents of the subnational nations, which would be retained.

***

“The Constitutional Acts of China 1920 revived the National Assembly of China which was suspended by Yuan Shikhai in 1916, and the Hongxian Emperor, Yuan Keding, was more willing than his father to ascertain his rule under at least a semi-democratic government. The Constitutional Acts divided power between the Prime Minister, Emperor and the National Assembly which each player receiving 1/3 of the total executive power. As a result, the Hongxian Emperor opened the first National Assembly (largely consisting of independents) on the 17th of October, 1920 declaring that a general election for the 168 seat Senate and 406 Seat House of Representatives would take place the next year. The electoral system of the elections had their seats broken down into electoral districts designed for each county and equivalent of China. Women had received partial voting rights in the election as well, with Women with high incomes allowed to vote according to the new constitution of China.

The Hongxian Emperor

There was also the matter that Lou Tseng-Tsiang, the Prime Minister of the Hongxian Emperor was becoming increasingly unpopular among the Chinese populace due to his Roman Catholicism faith. Under the Chinese Empire, China was undergoing a renaissance of Chinese culture, and that included traditional Chinese folk religions, Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. Christians in China were generally looked down upon, with the memory of the Taiping Rebellion still fresh in the minds of many.

As the date of the election was announced, the major political groups of the Empire began to coalesces with one another to establish proper political parties. The strongest of these political ‘pressure groups’ which had been legal before the 1920 Constitution was the Communications Clique. The Clique was a powerful interest group consisting of politicians, bureaucrats, technocrats, businessmen, engineers and labour unionists. It was a centrist political group that was succeeded by the Chinese Union and Communications Party (CUCP). CUCP elected Tang Shaoyi, the former Minister of Mail and Communications of the Imperial Cabinet under the Qing as their leader. He was a moderate and charismatic leader, and was a very vocal pro-democracy and pro-constitutional monarchism politician in China. The CUCP based its foundations on basic technocratic ideals based in centrism.

Liang Qichao

In 1916, the Chinese Progressive Party was dissolved by imperial decree of Yuan Shikhai. As highlighted before this, only political pressure groups, and not parties were allowed before the 1920 Constitution. The party was succeeded by the Research Clique, led by Liang Qichao as its leader. The Research Clique was instrumental in pushing the Chinese into the Great War against the Germans, and the clique had the ear of the Hongxian Emperor. Many constitutional monarchists from Su Yat-Sen’s Constitutional Protection Movement also defected over to the clique after the successive end of the Great War, which allowed the clique to gain some modicum of power. After the constitution of 1920, the Clique was dissolved and the Progressive Party was reinstated once again. Liang Qichao continued to lead the party, and based the party’s foundation in solid liberal conservatism.

Considering outright republican parties and outright communist/socialist parties in China were banned during this time, the leftwing coalition of politicians in China grouped together into one loose union called the China Democratic Socialist Party, which was led by Carsun Chang. Chang, a Shanghai native by birth, was also a labour unionist, and he retained ambivalent tones to the monarchy in his political outlook to not gain the ire of the Imperial government. Its inspiration was the Social Democratic Parties of Scandinavia and advocated for market capitalism and greater social reforms in China, though it remained supportive of the Imperial government to avoid arrests.

The Chinese Youth Party founded by Li Huang, a philosopher and lawyer by trade, was the typical right wing party of the country that was focused on Chinese nationalism. It consisted of several former veterans as well, and made the remaining concessions in China a focal part of their policy whilst remaining fiscally conservative in their economic outlook. Majority of the Kuomintang refused to take part in the election due to their republican outlook, but many pro-constitutional monarchical members of the party, led by Chen Qimei took part in the elections under the name of Kuomintang (Pro-Government). Sun Yat-Sen would denounce the members of his party taking part in the election, casting them out of the party from his headquarters in the British Concession in Shanghai, however the Imperial Government would continue to recognize the Chen faction of the Kuomintang as the legitimate faction of the party.

During the elections, the CUCP managed to gain the largest share of the vote and seats, however remained far away from an actual majority. However Laing Qichao agreed to give the CUCP Confidence and Supply with his own Progressive Party, which allowed the CUCP to form a minority government in the National Assembly. In the resulting contingent elections, Tang Shaoyi, became the first partisan Prime Minister of the Restored Imperial Chinese state.” Chinese Electoral History © ImpChinaGov.net

***

---

[1] – Economic information from The German Hyperinflation and the Demand for Money Revisited by P. Michael

[2] – Kaysar ship based on the Progetto G Class Battleship of Italy otl that was not made.

[3] – based on characteristics of the French O’Byrne Class Submarines otl.

Last edited: