I've been a little stricken with writer's block lately, and need more time to figure out material concerning the Ottomans. As such, we're getting a shorter update today that's just about Russia. The Turks and the Greeks will show up next time.

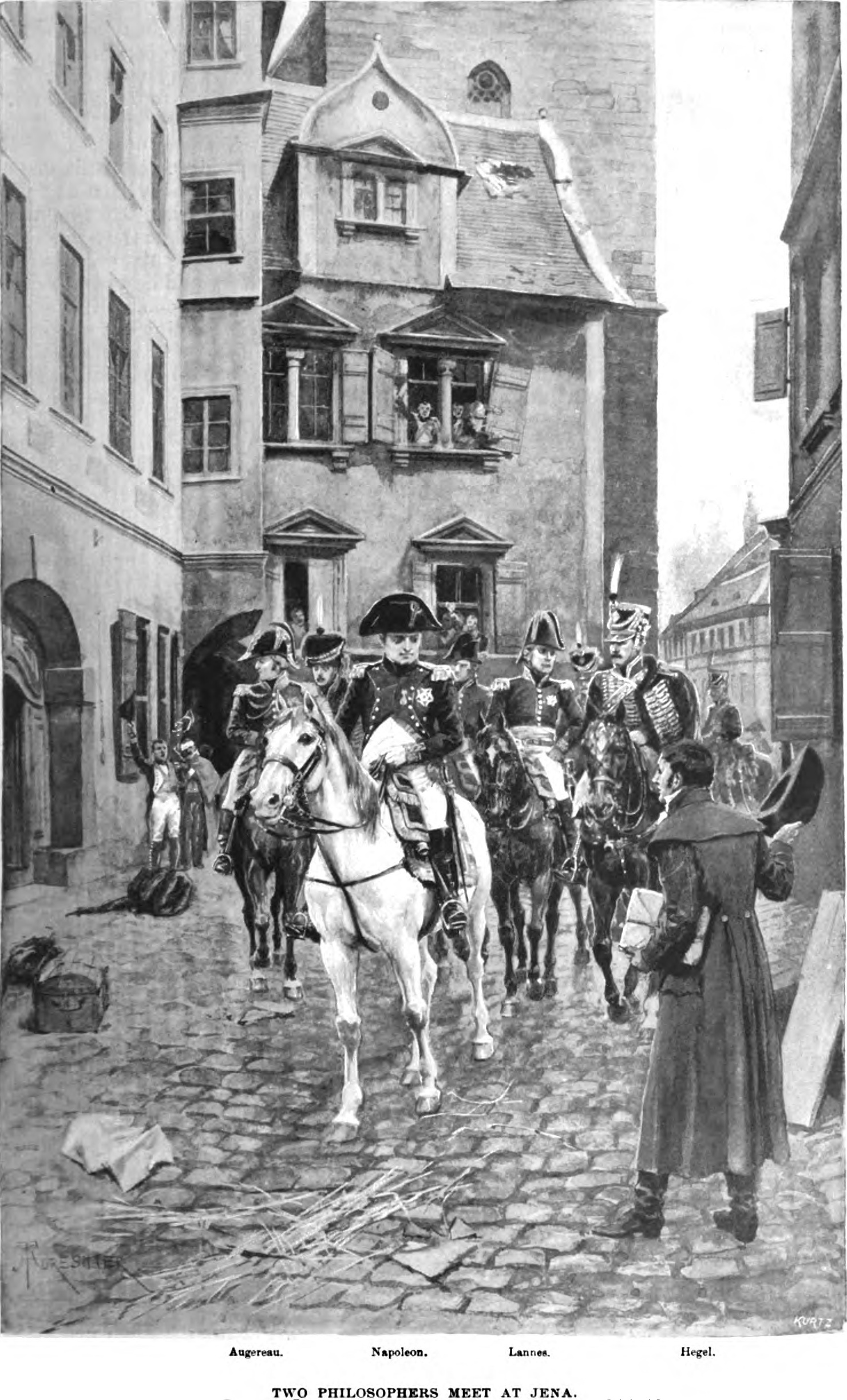

The course of the Napoleonic Wars turned on the Emperor’s ability to frustrate the repeated efforts of France’s rivals to organize coalitions against it. And the lynchpin for this strategy was the Franco-Russian relationship: the rapprochement between Napoleon and Tsar Alexander removed one potential threat to the French Empire, weakened another rival in Prussia, and diverted British attention to Scandinavia and the Balkans, exacerbating the strategic indecisiveness of post-Pitt Britain. For his part, Alexander benefited from a freer hand strategically. Freed of obligations to participate in the main theaters of the war with France, the Tsar was able to expand his rule in both Europe and Asia and to consolidate power through internal reforms.

Alexander is remembered as a cipher among more transparent kin. The impetuous fighter so easily lured into disaster at Austerlitz developed into a far cannier statesman in the wake of Tilsit. The romantic who bound Poland and Finland together with Russia through personal unions grew colder and more rigidly authoritarian in his later years. Despite these changes to his demeanor, the Tsar retained some degree of idealism, which manifested in fits and spurts for the rest of his reign.

This ideological inconsistency was on full display in Alexander’s stabs at governmental reform. Russia has always struggled to keep pace with the industry and institutions of Western Europe, and the decade following Madrid was no exception. The Reformist minister Mikhail Speransky led the charge for a Constitutional order, balancing the monarch’s power against a series of local Dumas, with the State Council acting as an intermediary body. These suggestions were calculated to shift Russia away from absolute monarchy towards a more pluralistic and federalist society. [1]

This vision was unlikely to have ever seen fruition under Alexander; even during the time when Speransky enjoyed the Tsar’s favor, his ideals drew ire from more conservative elements in the Russian aristocracy. As it was, however, Alexander opted for a scaled-back variation on his minster’s proposal, modified to suit his own needs. The Dumas were eschewed, and the Council, while initially dominated by Speransky and his allies, came to include more members from the nobility, diluting the influence of reformist voices.

These new additions expanded the Council’s total membership, which reached 60 seats in 1825. This would remain the general size of the State Council for the remainder of the 19th Century, with slight fluctuations. The Tsar retained the right to appoint or dismiss members, but as the years went by, the body managed to erode this ostensible check on their power. Alexander’s successors gave progressively greater deference to the Council’s word on many topics, and eventually, this came to include the selection of replacement members or the early dismissal of those who had alienated enough of their colleagues. Political parties remained officially verboten under the Tsarist regime, but an informal smattering of factions nevertheless emerged in the Council, with reformers, conservatives and moderates competing for the monarch’s ear. As a result, the political development of Russia from the time of Peter the Great began changing course in the 19th Century. [2]

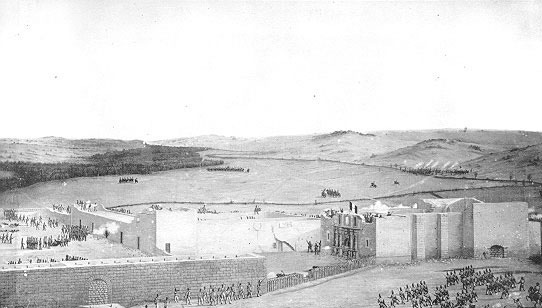

The State Council's Iconic Meeting Place in St. Isaac's Square.

This was the backdrop against which the Empire faced its first true test since the Treaty of Tilsit. On December 16th, 1824, the Tsar succumbed to typhus at the age of 46. The crown passed to his younger brother Konstantin, a more personable figure than the increasingly mercurial Alexander, but also one without his brother’s decisiveness and resolve. [3]

As critical as this difference in personality was, one other difference stood out between the new Tsar and his brother. Unlike Alexander, Konstantin never lost his youthful admiration of Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he had fought at Austerlitz and treated with at Tilsit. As a result, when Speransky approached the new emperor to discuss secret negotiations with the French concerning Christian uprisings against the Ottomans in the Balkans, Konstantin was quick to accede to the French proposal.

[1] IOTL Speransky took the blame for the Franco-Russian alliance falling through. ITTL, Alexander has taken to relying on modified versions of his ideas to help govern. For him, the State Council is a tool to institutionalize that process with the help of competing voices.

[2] I thought liberalism and republicanism might have had too much success so far, so to keep things interesting, we have Russia’s first stab at a Constitutional system devolve into a self-dealing parody of an actual Parliament.

[3] Because of butterflies, Konstantin didn’t go to Poland, and remains amenable, albeit less than enthused, about succeeding his brother.

Chapter Twenty: December Days

Excerpted from The Age of Revolutions by A.F. Stoddard, 2006.

The course of the Napoleonic Wars turned on the Emperor’s ability to frustrate the repeated efforts of France’s rivals to organize coalitions against it. And the lynchpin for this strategy was the Franco-Russian relationship: the rapprochement between Napoleon and Tsar Alexander removed one potential threat to the French Empire, weakened another rival in Prussia, and diverted British attention to Scandinavia and the Balkans, exacerbating the strategic indecisiveness of post-Pitt Britain. For his part, Alexander benefited from a freer hand strategically. Freed of obligations to participate in the main theaters of the war with France, the Tsar was able to expand his rule in both Europe and Asia and to consolidate power through internal reforms.

Alexander is remembered as a cipher among more transparent kin. The impetuous fighter so easily lured into disaster at Austerlitz developed into a far cannier statesman in the wake of Tilsit. The romantic who bound Poland and Finland together with Russia through personal unions grew colder and more rigidly authoritarian in his later years. Despite these changes to his demeanor, the Tsar retained some degree of idealism, which manifested in fits and spurts for the rest of his reign.

This ideological inconsistency was on full display in Alexander’s stabs at governmental reform. Russia has always struggled to keep pace with the industry and institutions of Western Europe, and the decade following Madrid was no exception. The Reformist minister Mikhail Speransky led the charge for a Constitutional order, balancing the monarch’s power against a series of local Dumas, with the State Council acting as an intermediary body. These suggestions were calculated to shift Russia away from absolute monarchy towards a more pluralistic and federalist society. [1]

This vision was unlikely to have ever seen fruition under Alexander; even during the time when Speransky enjoyed the Tsar’s favor, his ideals drew ire from more conservative elements in the Russian aristocracy. As it was, however, Alexander opted for a scaled-back variation on his minster’s proposal, modified to suit his own needs. The Dumas were eschewed, and the Council, while initially dominated by Speransky and his allies, came to include more members from the nobility, diluting the influence of reformist voices.

These new additions expanded the Council’s total membership, which reached 60 seats in 1825. This would remain the general size of the State Council for the remainder of the 19th Century, with slight fluctuations. The Tsar retained the right to appoint or dismiss members, but as the years went by, the body managed to erode this ostensible check on their power. Alexander’s successors gave progressively greater deference to the Council’s word on many topics, and eventually, this came to include the selection of replacement members or the early dismissal of those who had alienated enough of their colleagues. Political parties remained officially verboten under the Tsarist regime, but an informal smattering of factions nevertheless emerged in the Council, with reformers, conservatives and moderates competing for the monarch’s ear. As a result, the political development of Russia from the time of Peter the Great began changing course in the 19th Century. [2]

The State Council's Iconic Meeting Place in St. Isaac's Square.

This was the backdrop against which the Empire faced its first true test since the Treaty of Tilsit. On December 16th, 1824, the Tsar succumbed to typhus at the age of 46. The crown passed to his younger brother Konstantin, a more personable figure than the increasingly mercurial Alexander, but also one without his brother’s decisiveness and resolve. [3]

As critical as this difference in personality was, one other difference stood out between the new Tsar and his brother. Unlike Alexander, Konstantin never lost his youthful admiration of Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he had fought at Austerlitz and treated with at Tilsit. As a result, when Speransky approached the new emperor to discuss secret negotiations with the French concerning Christian uprisings against the Ottomans in the Balkans, Konstantin was quick to accede to the French proposal.

[1] IOTL Speransky took the blame for the Franco-Russian alliance falling through. ITTL, Alexander has taken to relying on modified versions of his ideas to help govern. For him, the State Council is a tool to institutionalize that process with the help of competing voices.

[2] I thought liberalism and republicanism might have had too much success so far, so to keep things interesting, we have Russia’s first stab at a Constitutional system devolve into a self-dealing parody of an actual Parliament.

[3] Because of butterflies, Konstantin didn’t go to Poland, and remains amenable, albeit less than enthused, about succeeding his brother.

Last edited: