Yes, I think the second option is vastly more likely.Well, the former of those in particular seems likely to induce the Swedes to keep on fighting rather than accept the settlement. Given the difficulty of resupplying Davout and the potential for the British to try sending help again, I think Napoleon would have to settle for something less extravagant. Granted, he had his share of political/diplomatic blunders IOTL, but he develops into a somewhat more cautious grand strategist in this course of events.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Marche Consulaire: A Napoleonic Timeline

Threadmarks

View all 59 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Fifty: Le Plus Ça Change... Chapter Fifty-One: The Martyr's Rule Begins Chapter Fifty-Two: Seeds of Eulogy Chapter Fifty-Three: Halfway Along Our Life’s Path Chapter Fifty-Four: Cherchez La Femme…Or May The Bridges That She Burns Light The Way Chapter Fifty-Five: Macartney's Revenge Chapter Fifty-Six: Misty Tales and Poems Lost Chapter Fifty-Seven: One Step at a TimeYes, I think the second option is vastly more likely.

Well, it might have been something to think about at the time, but I'm inclined against huge shifts to events from the beginning of the story. Also, I've been toying with the possibility of Carl August living longer instead of the Bernadottes in Stockholm.

Hope you enjoy the TL regardless, though. Story of a Party is still a favorite of mine around here.

Well, the Algiers operation was largely driven by Marshal Savary wanting to make a name for himself, and the Barbary Pirates being an unsympathetic target.

Fair enough!

I think one area that might be interesting is South America- it largely fell into the British sphere OTL, but France has a chance to act as a genuine competitor here. Paris has a real chance to be a rival financial centre to London, and with Spain being much closer to France ITTL, I can picture her colonies and 'dominions' gradually falling under the sway of French capital.

So, no French West Australia?Well, the Algiers operation was largely driven by Marshal Savary wanting to make a name for himself, and the Barbary Pirates being an unsympathetic target. I agree on the indefensibility of Western Australia, though. Commerce raiders from there could be a nuisance in the Strait of Malacca, but a nuisance is all they'd be in the end, so it doesn't seem worth it.

Fair enough!

I think one area that might be interesting is South America- it largely fell into the British sphere OTL, but France has a chance to act as a genuine competitor here. Paris has a real chance to be a rival financial centre to London, and with Spain being much closer to France ITTL, I can picture her colonies and 'dominions' gradually falling under the sway of French capital.

On the other hand, a lot of British commercial dominance was a result of the fact that during the period of alliance between Revolutionary/Napoleonic France and Spain, Britain effectively cut off Spanish America from Spain proper, and to fill the void in trade this created, illegal smuggling and trade increased dramatically between Britain (and to a lesser extent the US) and Spanish America. This gave Britain a vast commercial advantage, and would still be the case ITTL.

Fair enough!

I think one area that might be interesting is South America- it largely fell into the British sphere OTL, but France has a chance to act as a genuine competitor here. Paris has a real chance to be a rival financial centre to London, and with Spain being much closer to France ITTL, I can picture her colonies and 'dominions' gradually falling under the sway of French capital.

I have plans for the development of South America, but they're more political than economic. Other than agricultural products and a market for French goods, what else could the French expect to gain from greater involvement there?

So, no French West Australia?

Probably not. Too contentious.

On the other hand, a lot of British commercial dominance was a result of the fact that during the period of alliance between Revolutionary/Napoleonic France and Spain, Britain effectively cut off Spanish America from Spain proper, and to fill the void in trade this created, illegal smuggling and trade increased dramatically between Britain (and to a lesser extent the US) and Spanish America. This gave Britain a vast commercial advantage, and would still be the case ITTL.

Oh, absolutely. I mean, to set out my thinking- even a Napoleonic France is going to be at severe disadvantages competing with Britain overseas. A France that dominates Europe is likely to have more luck in key theatres like Egypt, but all things being equal by 1900 I expect the British to have a larger formal and informal empire.

But the Spanish also did things to lock themselves out of Latin America- the pigheaded refusal to recognise the independence of their former colonies for so long, the failure to reform in Cuba and what have you. Here, with Spain being much more in France's orbit I think that will be mitigated- and that if Spain has access to Latin America, her patron- sorry, ally- will have access as well.

I'm picturing a situation where (Gran) Colombia, for example, becomes an unofficial dominion along the lines of Argentina- which would set up interesting zones of competition with Britain and her clients in Panama and Guyana.

Or Mexico, which could be a wonderful nexus of Mexican, American, British, French and Spanish influences, all competing with each other via espionage, capital and on occasion, brute force.

Chapter Thirty-Three: Growing Pains

Update time again. Here's a short-ish primer on Mexico and its post-1819 development. Enjoy!

For both the Spanish-speaking world and otherwise, the Ordinance of 1819 remains one of the great experiments in political history. Because of the Palafox Regency’s desperation to disentangle itself from colonial wars, prime minister Calo’s plan afforded the newly appointed viceroys great leeway in determining the governmental structures of the new American kingdoms. As a result, the world saw a wide variety of governments emerge in Central and South America in the 1820’s and 30’s.

In New Spain, Viceroy José María Morelos faced a seemingly impossible task: not only to construct a new government to replace the colonial regime, but also one capable of advancing his ideals. A staunch liberal, Morelos dreamed of a Mexico where slavery was abolished, there was equality between races, and the poor and dispossessed would no longer be exploited by landowners and the Church. Unfortunately for him, these aspirations were at odds with his immediate responsibilities as a Viceroy – the only way he could create functional institutions in the post-independence vacuum required the cooperation of the very elites most opposed to his reformist agenda.

The Constitution for New Spain took shape over the course of 1820 and 1821, coming into force at the end of 1821. This document established the Kingdom as a federal system with significant autonomy for its initial 26 states. [1] The sheer diversity of the different states necessitated high degrees of local autonomy, but it also frustrated some of Morelos’ ambitions.

Slavery, for example, was a rarity in the majority of states. Unlike their northern neighbour, New Spain had never relied on slave labor as the basis for its economy, and the number of slaves had declined precipitously by the time of the Ordinance. As a result, abolition of slavery was a negligible demand for most of the Kingdom. The exception to this trend was Cuba, where labour-intensive sugarcane production still made slaves a valuable commodity. Cuban authorities obstinately refused to consider limiting the practice, and even states that abolished slavery themselves were loathe to force abolition on Cuba, troubled by the implications of overbearing federal power. By the time of Morelos’ death in 1828, slavery remained commonplace on the island.

Vicente Guerrero succeeded Morelos as Viceroy after his death.

In the meantime, the Viceroy had other challenges to address in helping New Spain stand as a sovereign kingdom. The 1821 Constitution laid out general principles for governance, but it was no substitute for a comprehensive code of laws. Certain edicts from the Spanish crown remained in force, but others had been invalidated by the new status of the Kingdom. These inconsistencies, combined with a shortage of judges, lawyers, and other professionals resulted in no small degree of confusion. One Mexican businessman, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, was able to exploit loopholes in existing bankruptcy law to repeatedly liquidate the debts he incurred through risky investing practices, while still accumulating assets. Over a 22-year period from 1820 to 1842, Santa Anna declared bankruptcy eleven times, while paradoxically growing richer all the while. [2]

Political parties were also something that took time to develop in New Spain. The first political factions to emerge in the kingdom had their roots in rival Masonic lodges, of all things. The Scottish Rite Lodge was well-established, having existed since before the struggle for independence. As a result, it became the rallying point for conservative politicians in New Spain. The Scottish Lodge opposed the federalist system imposed by Morelos, advocating for a stronger central government to protect the interests of landowning elites.

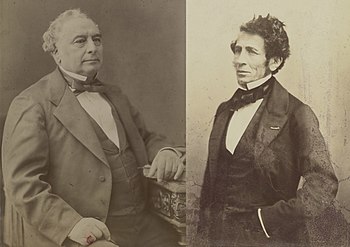

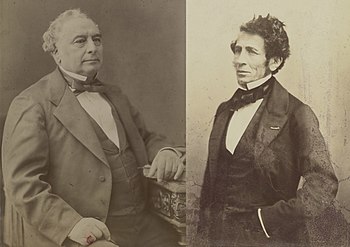

Anastasio Bustamante, leader of the Scottish Rite Lodge.

Their opposition rallied around another Lodge, the newly established York Rite Masons. Led by Vicente Guerrero, an Afro-Mestizo general, the Yorkinos supported Viceroy Morelos in his hopes of reforming Mexican society. Their close association with Morelos worked to their advantage; after Morelos’ death, King Francisco thought it only logical to appoint Guerrero as the new Viceroy, giving the Yorkinos an opening to continue their federalist agenda. [3]

Their ideals would soon be put to the test, however. By the end of the 1820’s, Tejas had become increasingly restive, with an influx of Anglo-American settlers agitating for an end to federally-mandated Catholicism, one of the few major impositions from the federal government. More radical voices, led by men like Samuel Houston and Davy Crockett, went so far as to encourage the United States government to annex the border territory. By the end of the 1820’s, these American settlers outnumbered the Spanish and French-speaking communities in the state.

Matters came to a head in 1830, when the Scottish Rite Lodge staged a coup against Viceroy Guerrero. The Lodge, led by Anastasio Bustamante, reversed course on the matter of state autonomy. For Tejas, this meant higher taxes, a ban on further American settlement, and a ban on slavery. [4] Americans decried these new restrictions, especially the slave ban, pointing out the hypocrisy in imposing such a condition when Cuba remained unfettered by it. Stephen F. Austin took the first step towards independence. On September 8th 1832, he decried Bustamante as an illegitimate Viceroy, and called upon his fellow Tejans to take up arms against the new regime. Secretly, he and his fellow settlers also sent a missive to President Pike, requesting assistance. The Tejan Revolution had begun.

[1] In addition to the 19 OTL Mexican states, the Kingdom also includes six additional ones in Central America, plus Cuba. These were all part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and because the Spanish government didn’t see the Ordinance as granting full independence, they didn’t see a problem in lumping these territories all in together. Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo were separated by another of the Ordinance’s provisions, however. They’re governed by Spain directly.

[2] Funny Easter egg I’ve wanted to throw in for a while. Santa Anna's parents wanted him to go into business IOTL. Here, he knuckles under and does just that.

[3] The political role of Masonic Lodges in Mexico is another of those OTL oddities. Beats a civil war over chariot racers, at least.

[4] Guerrero got couped IOTL as well. Poor guy can't catch a break.

Chapter Thirty-Three: Growing Pains

Excerpted from The Road to War: 1830-1852 by Alexander Peterson, 1971.

For both the Spanish-speaking world and otherwise, the Ordinance of 1819 remains one of the great experiments in political history. Because of the Palafox Regency’s desperation to disentangle itself from colonial wars, prime minister Calo’s plan afforded the newly appointed viceroys great leeway in determining the governmental structures of the new American kingdoms. As a result, the world saw a wide variety of governments emerge in Central and South America in the 1820’s and 30’s.

In New Spain, Viceroy José María Morelos faced a seemingly impossible task: not only to construct a new government to replace the colonial regime, but also one capable of advancing his ideals. A staunch liberal, Morelos dreamed of a Mexico where slavery was abolished, there was equality between races, and the poor and dispossessed would no longer be exploited by landowners and the Church. Unfortunately for him, these aspirations were at odds with his immediate responsibilities as a Viceroy – the only way he could create functional institutions in the post-independence vacuum required the cooperation of the very elites most opposed to his reformist agenda.

The Constitution for New Spain took shape over the course of 1820 and 1821, coming into force at the end of 1821. This document established the Kingdom as a federal system with significant autonomy for its initial 26 states. [1] The sheer diversity of the different states necessitated high degrees of local autonomy, but it also frustrated some of Morelos’ ambitions.

Slavery, for example, was a rarity in the majority of states. Unlike their northern neighbour, New Spain had never relied on slave labor as the basis for its economy, and the number of slaves had declined precipitously by the time of the Ordinance. As a result, abolition of slavery was a negligible demand for most of the Kingdom. The exception to this trend was Cuba, where labour-intensive sugarcane production still made slaves a valuable commodity. Cuban authorities obstinately refused to consider limiting the practice, and even states that abolished slavery themselves were loathe to force abolition on Cuba, troubled by the implications of overbearing federal power. By the time of Morelos’ death in 1828, slavery remained commonplace on the island.

Vicente Guerrero succeeded Morelos as Viceroy after his death.

In the meantime, the Viceroy had other challenges to address in helping New Spain stand as a sovereign kingdom. The 1821 Constitution laid out general principles for governance, but it was no substitute for a comprehensive code of laws. Certain edicts from the Spanish crown remained in force, but others had been invalidated by the new status of the Kingdom. These inconsistencies, combined with a shortage of judges, lawyers, and other professionals resulted in no small degree of confusion. One Mexican businessman, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, was able to exploit loopholes in existing bankruptcy law to repeatedly liquidate the debts he incurred through risky investing practices, while still accumulating assets. Over a 22-year period from 1820 to 1842, Santa Anna declared bankruptcy eleven times, while paradoxically growing richer all the while. [2]

Political parties were also something that took time to develop in New Spain. The first political factions to emerge in the kingdom had their roots in rival Masonic lodges, of all things. The Scottish Rite Lodge was well-established, having existed since before the struggle for independence. As a result, it became the rallying point for conservative politicians in New Spain. The Scottish Lodge opposed the federalist system imposed by Morelos, advocating for a stronger central government to protect the interests of landowning elites.

Anastasio Bustamante, leader of the Scottish Rite Lodge.

Their opposition rallied around another Lodge, the newly established York Rite Masons. Led by Vicente Guerrero, an Afro-Mestizo general, the Yorkinos supported Viceroy Morelos in his hopes of reforming Mexican society. Their close association with Morelos worked to their advantage; after Morelos’ death, King Francisco thought it only logical to appoint Guerrero as the new Viceroy, giving the Yorkinos an opening to continue their federalist agenda. [3]

Their ideals would soon be put to the test, however. By the end of the 1820’s, Tejas had become increasingly restive, with an influx of Anglo-American settlers agitating for an end to federally-mandated Catholicism, one of the few major impositions from the federal government. More radical voices, led by men like Samuel Houston and Davy Crockett, went so far as to encourage the United States government to annex the border territory. By the end of the 1820’s, these American settlers outnumbered the Spanish and French-speaking communities in the state.

Matters came to a head in 1830, when the Scottish Rite Lodge staged a coup against Viceroy Guerrero. The Lodge, led by Anastasio Bustamante, reversed course on the matter of state autonomy. For Tejas, this meant higher taxes, a ban on further American settlement, and a ban on slavery. [4] Americans decried these new restrictions, especially the slave ban, pointing out the hypocrisy in imposing such a condition when Cuba remained unfettered by it. Stephen F. Austin took the first step towards independence. On September 8th 1832, he decried Bustamante as an illegitimate Viceroy, and called upon his fellow Tejans to take up arms against the new regime. Secretly, he and his fellow settlers also sent a missive to President Pike, requesting assistance. The Tejan Revolution had begun.

[1] In addition to the 19 OTL Mexican states, the Kingdom also includes six additional ones in Central America, plus Cuba. These were all part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and because the Spanish government didn’t see the Ordinance as granting full independence, they didn’t see a problem in lumping these territories all in together. Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo were separated by another of the Ordinance’s provisions, however. They’re governed by Spain directly.

[2] Funny Easter egg I’ve wanted to throw in for a while. Santa Anna's parents wanted him to go into business IOTL. Here, he knuckles under and does just that.

[3] The political role of Masonic Lodges in Mexico is another of those OTL oddities. Beats a civil war over chariot racers, at least.

[4] Guerrero got couped IOTL as well. Poor guy can't catch a break.

Last edited:

Shame about Guerrero, he sounded like an interesting option. Is he still alive or did the coup kill him?

Guerrero's quite dead, unfortunately. He was the King's choice to be Viceroy, so as long as he lived, the coup plotters would have had to justify why he wasn't in charge anymore.

Guerrero's quite dead, unfortunately. He was the King's choice to be Viceroy, so as long as he lived, the coup plotters would have had to justify why he wasn't in charge anymore.

Will someone else take up the progressive cause? I imagine the lower classes and natives aren't too happy about the new management?

Will someone else take up the progressive cause? I imagine the lower classes and natives aren't too happy about the new management?

Certainly the liberals will have other champions. And Tejas won't be the only restive state. All of that will be explored more in the next couple chapters.

I have a bit of a soft spot for the story of Texas, so I can't help but hope that things end up not being a catastrophe for them. At the same time, New Spain really needs to avoid too damaging a conflict to maximize their potential for growing into a stable power (though Santa Anna not being a factor yet by itself will help with that).

Perhaps a quick peace may actually be for the best for everyone here? Nonwithstanding the Texans, the Scottish Lodge regime facing a rapid loss would immensely tank their prestige and public support, plus in theory make the general public more supportive of better minority policy to avoid this sort of thing in the future (and hopefully help New Spain deal with future unrestive states without rebellion and force of arms). Both of those seem apt to help the Yorkinos gain the electoral and public support base they need to liberalize the nation in a stable manner.

Perhaps a quick peace may actually be for the best for everyone here? Nonwithstanding the Texans, the Scottish Lodge regime facing a rapid loss would immensely tank their prestige and public support, plus in theory make the general public more supportive of better minority policy to avoid this sort of thing in the future (and hopefully help New Spain deal with future unrestive states without rebellion and force of arms). Both of those seem apt to help the Yorkinos gain the electoral and public support base they need to liberalize the nation in a stable manner.

I have a bit of a soft spot for the story of Texas, so I can't help but hope that things end up not being a catastrophe for them. At the same time, New Spain really needs to avoid too damaging a conflict to maximize their potential for growing into a stable power (though Santa Anna not being a factor yet by itself will help with that).

Perhaps a quick peace may actually be for the best for everyone here? Nonwithstanding the Texans, the Scottish Lodge regime facing a rapid loss would immensely tank their prestige and public support, plus in theory make the general public more supportive of better minority policy to avoid this sort of thing in the future (and hopefully help New Spain deal with future unrestive states without rebellion and force of arms). Both of those seem apt to help the Yorkinos gain the electoral and public support base they need to liberalize the nation in a stable manner.

In retrospect, I could have structured the latest chapter and the one I'm currently working on a little better. The problem here is that Texas isn't the only rebellious state right now. It's part of a pattern, and as far as the centralists are concerned, the common denominator affecting all involved is foreign meddling of some kind. And they blame the weak central government of the 1820's for that. Also, Bustamante went full police state pretty quickly when he became President IOTL. So a quick resolution isn't really in the cards here. Things are going to get worse before they can get better, as they say.

Chapter Thirty-Four: Backlash

I've got a little time away from classes, so to make up for lost time, I'm basically writing as fast as I can right now. This has led to some compromises, and I feel like parts of this new chapter should have been included in the last one, or vice versa. Still, it is what it is. This gives more background on the goings-on in Mexico before and during the Bustamante coup, explaining why the Scottish Lodge felt the need for extreme measures. Enjoy!

The conservative forces behind the Mexican coup d’état of 1830 are commonly misunderstood as mindless reaction. This interpretation is a product of hindsight, however, as the turmoil of the Bustamante government are better-known than the difficulties that came before him. The first decade of Mexican history was defined by federalist government under Viceroys Morelos and Guerrero. Although their decentralized approach was crucial in keeping a disparate new nation together, it also provided weaknesses. More than anything, Bustamante sought power in order to correct these vulnerabilities.

The lack of a strong central government in Mexico City resulted in greater state power relative to the United States. But it also created a vacuum that was filled by other actors. These included businessmen, who took advantage of lax regulations to turn immense profits on the country’s economic development. Both foreign investors such as Émile and Issac Pérriere, as well as domestic ones like the aforementioned Santa Anna were prominent economic forces in this time, using their wealth and influence to suborn or simply flout state authority in the process. [1]

In 1825, the Pérriere brothers arranged a commercial pact with the state of Costa Rica. The region’s mountainous and heavily forested terrain made it nearly impossible for farmers to transport their coffee crop to Europe. Because of this, the French investors offered the state government a deal: they would finance the construction of a trade route to France via the Pacific port of Puntarenas. [2] In exchange, they would be entitled to half of the profits from the exported coffee. Costa Rican Governor José Rafael Gallegos knew full well how exploitative this proposal was, but felt trapped by the poverty and neglect of his citizens. As a result, he acceded to the proposal, and work on port construction began the following year. This gave foreign investors a foot in the door, beginning the slow decline in fiscal autonomy for the region.

Emile and Isaac Pérriere saw great potential for financial benefit in New Spain.

Even more worrying from the perspective of Mexican nationalists were the regional separatist movements that existed in several states. The Anglo settlers in Tejas were the loudest and most prominent of these, but others tasked the central government as well. In San Salvador, property taxes levied by the nearly bankrupt state government resulted in uprisings among the Native population. These rebels burned down local haciendas, with the intent to redistribute the farmland among its workers. Revolts in 1826 and 1828 were, however, suppressed by the Mexican army. What was more worrying for Mexico City was the discovery of an 1824 petition on the part of Salvadorians, requesting admission into the United States. Nothing came of this missive, but its exposure stoked fears of American interference in Mexican affairs.

This context is critical to understand the situation Anastasio Bustamante inherited in 1830 after his overthrow of Guerrero. Federalism led, or so it seemed, to fragmentation, and that, in turn, to separatism and domination by foreign capital. Bustamante spoke with some regularity of “French-American conspirations aimed at encirclement.” Advocates of centralization also had the history of their northern neighbour to point to: the Americans had, after all, replaced their founding document with a Constitution that concentrated far more authority within the federal government. Why should New Spain not follow suit?

But while the historical context explains why Bustamante and the Scottish Rite Lodge took the course they did, it does not follow that they played their hand well. Bustamante quickly resorted to drastic measures to secure his power. A secret police was established, and the press censored. Opponents of the regime were imprisoned or exiled, and membership in the York Rite Lodge became a crime. [3] These measures were effective in the short term; a heavily disputed snap election in 1831 returned a Congress far more supportive of the conservative agenda than its predecessor. With two branches of government secured and the judiciary intimidated into silence, Bustamante could govern as he wished.

His first order of business was to rein in the depredations of foreign investors. The Costa Rican commercial pact was renegotiated by fiat: the Mexican government would acquire the shares of the revenue from Puntarenas owned by the Pérriere brothers in exchange for a modest lump sum payment as compensation. A new statute required any similar commercial deals to be arranged by the federal government rather than states themselves. These future deals invariably saw the government pocket a percentage of the proceeds. The revenue from this economic intervention was distributed to Bustamante’s allies to buy their loyalty.

With his expropriation of foreign largesse, Bustamante had secured his political position as best he could. It was only now that he moved to suppress the country’s secessionist movements. Unfortunately, the fatal flaw in his political strategy became apparent at this point: by taking what he believed were necessary actions to confront New Spain’s enemies, Bustamante unwittingly multiplied the number of opponents he himself faced.

These enemies included foreign ones as well as domestic malcontents. France was a concern, in light of the arbitrary seizure of Puntarenas. But the more pressing danger for the centralists was Spain. By deposing and executing the chosen Viceroy of King Francisco, Bustamante had irreparably alienated the Crown. The Spanish King had no interest in another costly war in the Americas, but he made clear that Bustamante was an illegitimate Viceroy, appointing York Lodge founder Lorenzo de Zavala as his replacement. This move was an intentional slight against Bustamante as much as anything, because Zavala could not feasibly take up his new appointment. In 1830, the physician-diplomat was living in exile in New Orleans, where he mingled freely with several of the same Tejas provocateurs the Bustamante government so feared.

Lorenzo de Zavala would never become more than Viceroy in name only.

And so an unfortunate web of coincidence brought Tejas to the center of Bustamante’s attention. His conspiracy-focused mind quickly deemed this rebellious province, with its concentration of Yorkinos, French, and Americans, to be the key to the Kingdom’s decade of unraveling. And Austin and his allies, for their part, had chosen their moment well: by November 1832, they had expelled Mexican troops from eastern Tejas. The approaching winter would buy time to consolidate their position.

With these realities in mind, Bustamante decided overwhelming force was the best recourse to quell the Tejas rebellion. In February 1833, a Mexican army of 9,000 men entered Tejas under General Vicente Filisola. Outnumbered fourfold, the Tejano rebels could do little but pray for a miracle. What they would receive was something else altogether.

[1] OTL bankers and rivals of the Rothschilds.

[2] A similar arrangement was made with Costa Rica in 1841 IOTL. By a French captain, oddly enough. The reason the Pérrieres approached them with this a decade and a half earlier will become clear later on.

[3] Except for targeting the York Lodge specifically, all of this is stuff Bustamante did as president IOTL. Like I said, he went full police state pretty quickly.

Chapter Thirty-Four: Backlash

Excerpted from The Road to War: 1830-1852 by Alexander Peterson, 1971.

The conservative forces behind the Mexican coup d’état of 1830 are commonly misunderstood as mindless reaction. This interpretation is a product of hindsight, however, as the turmoil of the Bustamante government are better-known than the difficulties that came before him. The first decade of Mexican history was defined by federalist government under Viceroys Morelos and Guerrero. Although their decentralized approach was crucial in keeping a disparate new nation together, it also provided weaknesses. More than anything, Bustamante sought power in order to correct these vulnerabilities.

The lack of a strong central government in Mexico City resulted in greater state power relative to the United States. But it also created a vacuum that was filled by other actors. These included businessmen, who took advantage of lax regulations to turn immense profits on the country’s economic development. Both foreign investors such as Émile and Issac Pérriere, as well as domestic ones like the aforementioned Santa Anna were prominent economic forces in this time, using their wealth and influence to suborn or simply flout state authority in the process. [1]

In 1825, the Pérriere brothers arranged a commercial pact with the state of Costa Rica. The region’s mountainous and heavily forested terrain made it nearly impossible for farmers to transport their coffee crop to Europe. Because of this, the French investors offered the state government a deal: they would finance the construction of a trade route to France via the Pacific port of Puntarenas. [2] In exchange, they would be entitled to half of the profits from the exported coffee. Costa Rican Governor José Rafael Gallegos knew full well how exploitative this proposal was, but felt trapped by the poverty and neglect of his citizens. As a result, he acceded to the proposal, and work on port construction began the following year. This gave foreign investors a foot in the door, beginning the slow decline in fiscal autonomy for the region.

Emile and Isaac Pérriere saw great potential for financial benefit in New Spain.

Even more worrying from the perspective of Mexican nationalists were the regional separatist movements that existed in several states. The Anglo settlers in Tejas were the loudest and most prominent of these, but others tasked the central government as well. In San Salvador, property taxes levied by the nearly bankrupt state government resulted in uprisings among the Native population. These rebels burned down local haciendas, with the intent to redistribute the farmland among its workers. Revolts in 1826 and 1828 were, however, suppressed by the Mexican army. What was more worrying for Mexico City was the discovery of an 1824 petition on the part of Salvadorians, requesting admission into the United States. Nothing came of this missive, but its exposure stoked fears of American interference in Mexican affairs.

This context is critical to understand the situation Anastasio Bustamante inherited in 1830 after his overthrow of Guerrero. Federalism led, or so it seemed, to fragmentation, and that, in turn, to separatism and domination by foreign capital. Bustamante spoke with some regularity of “French-American conspirations aimed at encirclement.” Advocates of centralization also had the history of their northern neighbour to point to: the Americans had, after all, replaced their founding document with a Constitution that concentrated far more authority within the federal government. Why should New Spain not follow suit?

But while the historical context explains why Bustamante and the Scottish Rite Lodge took the course they did, it does not follow that they played their hand well. Bustamante quickly resorted to drastic measures to secure his power. A secret police was established, and the press censored. Opponents of the regime were imprisoned or exiled, and membership in the York Rite Lodge became a crime. [3] These measures were effective in the short term; a heavily disputed snap election in 1831 returned a Congress far more supportive of the conservative agenda than its predecessor. With two branches of government secured and the judiciary intimidated into silence, Bustamante could govern as he wished.

His first order of business was to rein in the depredations of foreign investors. The Costa Rican commercial pact was renegotiated by fiat: the Mexican government would acquire the shares of the revenue from Puntarenas owned by the Pérriere brothers in exchange for a modest lump sum payment as compensation. A new statute required any similar commercial deals to be arranged by the federal government rather than states themselves. These future deals invariably saw the government pocket a percentage of the proceeds. The revenue from this economic intervention was distributed to Bustamante’s allies to buy their loyalty.

With his expropriation of foreign largesse, Bustamante had secured his political position as best he could. It was only now that he moved to suppress the country’s secessionist movements. Unfortunately, the fatal flaw in his political strategy became apparent at this point: by taking what he believed were necessary actions to confront New Spain’s enemies, Bustamante unwittingly multiplied the number of opponents he himself faced.

These enemies included foreign ones as well as domestic malcontents. France was a concern, in light of the arbitrary seizure of Puntarenas. But the more pressing danger for the centralists was Spain. By deposing and executing the chosen Viceroy of King Francisco, Bustamante had irreparably alienated the Crown. The Spanish King had no interest in another costly war in the Americas, but he made clear that Bustamante was an illegitimate Viceroy, appointing York Lodge founder Lorenzo de Zavala as his replacement. This move was an intentional slight against Bustamante as much as anything, because Zavala could not feasibly take up his new appointment. In 1830, the physician-diplomat was living in exile in New Orleans, where he mingled freely with several of the same Tejas provocateurs the Bustamante government so feared.

Lorenzo de Zavala would never become more than Viceroy in name only.

And so an unfortunate web of coincidence brought Tejas to the center of Bustamante’s attention. His conspiracy-focused mind quickly deemed this rebellious province, with its concentration of Yorkinos, French, and Americans, to be the key to the Kingdom’s decade of unraveling. And Austin and his allies, for their part, had chosen their moment well: by November 1832, they had expelled Mexican troops from eastern Tejas. The approaching winter would buy time to consolidate their position.

With these realities in mind, Bustamante decided overwhelming force was the best recourse to quell the Tejas rebellion. In February 1833, a Mexican army of 9,000 men entered Tejas under General Vicente Filisola. Outnumbered fourfold, the Tejano rebels could do little but pray for a miracle. What they would receive was something else altogether.

[1] OTL bankers and rivals of the Rothschilds.

[2] A similar arrangement was made with Costa Rica in 1841 IOTL. By a French captain, oddly enough. The reason the Pérrieres approached them with this a decade and a half earlier will become clear later on.

[3] Except for targeting the York Lodge specifically, all of this is stuff Bustamante did as president IOTL. Like I said, he went full police state pretty quickly.

I'm only on chapter 21, but I just want to thank you for an interesting timeline. I hope you are able to keep it going and meet your end goal of 2006. Best of luck!

I'm only on chapter 21, but I just want to thank you for an interesting timeline. I hope you are able to keep it going and meet your end goal of 2006. Best of luck!

You're quite welcome! I'm pretty determined to see this through, and I'll take as many years as I need to make sure it gets done. I should clarify that although the last entry will take place in 2006, that will be a distant epilogue sort of chapter. The main action of the story will wrap itself up a ways earlier. Around 1950 or so, at which point the social and political forces shaping the world of the epilogue should be apparent. But even that's a long ways off, of course, and I'm happy to have you along for the ride.

Chapter Thirty-Five: Politics by Other Means

I've been more productive lately than I've been since this story began, so here's Chapter 35 already. The Tejas Revolution continues, and escalates into something far bigger. Enjoy!

Like many revolutions, the rebellion in Tejas began militarily, leaving political actors struggling to keep pace with developments. The appointment of Lorenzo de Zavala as the next Viceroy for New Spain provided an immediate pretext for resistance against the Bustamante regime. Tejas Governor José María Viesca endorsed Zavala and called on other state governments to follow suit, but he himself had been pre-empted in his declaration by Stephen Austin, the unofficial leader of the Anglo settlers in the region. Viesca wouldn’t forget this slight, but the Governor understood that his goals still coincided with Austin’s. Both men were more interested in restoring Constitutional rule to the Kingdom than in seceding to join the United States. This differentiated the two from Haden Edwards, the hot-headed empresario in charge of the lands along the Navasota. [1]

By Summer of 1832, it had become clear that Bustamante would not step down from his position as Viceroy, regardless of Madrid’s opinion of him. Austin and other empresarios began mobilising their local militias to expel Mexican army units from the state. Viesca turned a blind eye to their activities, having reached a tacit understanding with Austin that secession was not in the offing. It is important for the present-day reader to remember that the sedition in Tejas was not unusual for Mexican provinces at this point. State Governors elsewhere were just as assertive in their denunciations of the centralists in Mexico City. El Salvador, Oaxaca, Zacatecas, and Yucatan also resisted the federal government, with varying degrees of effectiveness, stretching the Mexican army considerably. [2]

Three things set the unrest in Tejas apart from that in other states. The first was the empresario system. The empresarios were men authorised by the Mexican government to recruit settlers for the lands in Tejas. Once settlement was underway, the empresarios would also be expected to keep order in the lands under their supervision with private militias. This programme had the effect of raising military formations with no loyalty to the Mexican government, which certainly had its implications when the revolt against Bustamante began. But by allowing French and American empresarios to set up shop in Tejas, the government unwittingly diluted the cultural identity of the state. Immigrants were required to learn Spanish to gain admittance, but the establishment of tight-knit immigrant communities like Bettencour and San Felipe ensured that French and English were still used in day-to-day life, driving a wedge between the settlers and native Mexicans. The introduction of slavery presented yet another bone of contention, especially once Bustamante took power and began to undermine state autonomy.

The second difference between Tejas and other rebellious states is that the former could afford to trade space for time. The Mexican army under Filisola was too large to resist in open battle, but it was also too large to support itself in the field for long. The Tejano militias under Samuel Houston exploited this weakness by fighting delaying actions while drawing Filisola ever farther into enemy territory. The first major battle took place on the 3rd of March 1833, at the Nueces river northwest of Bettencour. The Tejans gave way quickly under the weight of numbers, but the army managed to retreat in good order. Filisola left men behind to occupy Bettencour while the bulk of his force advanced further northwest and captured the fort of Béxar. [3]

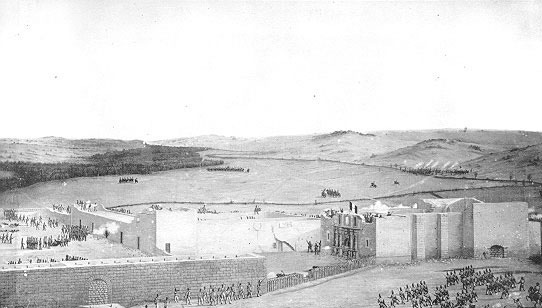

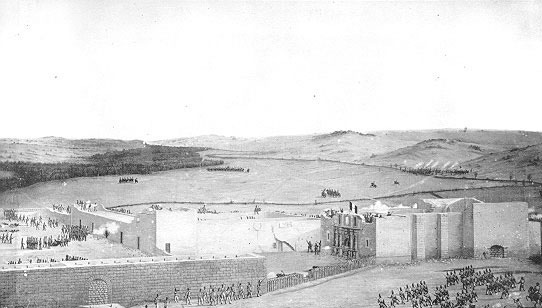

The fall of Béxar left Tejas dangerously exposed to the Mexican army.

It was at this point that political considerations began to reassert themselves. The complexion of the rebellion had changed over its first six months. A sizable influx of American volunteers bolstered the ranks of Houston’s army. This caused its own problems, however, as the army’s growing size also increased the importance of requisitioning supplies from local communities.

The political character of the rebels also changed dramatically during this time. The provisional government guiding the rebels was designed to coordinate the efforts of the empresarios with that of the original state government, but the sheer demographic weight of the English-speaking community and army resulted in the slow-motion marginalisation of Governor Viesca and other Mexican federalists. A proposal from Viesca for the Tejan army to mount a counteroffensive into New Spain in support of federalist forces was promptly voted down by the provisional government – with a large Mexican army encroaching on their territory, the idea of diverting forces elsewhere was deemed too risky. [4]

The situation for Tejas deteriorated even further over the Summer of 1833. Filisola split his army again, with separate forces laying siege to Goliad on the Gulf Coast, forcing the provisional government to abandon San Felipe, and still harrying Houston’s army as it retreated towards the Neches River. Houston readied his dispirited army for a last stand on the far bank, dispatched James Bowie to deliver a message, and waited for Filisola.

The Mexican army reached the Neches on July 16th. Filisola now commanded 5,500 men after having dispersed men to occupy Tejas, as well as sending several hundred men back into New Spain proper at Bustamante’s request to help put down Yorkino activity. Houston, for his part, commanded around 2,600 men, of which 1,500 had only come to Tejas after the start of the uprising the previous year. Filisola, sensing that the end of the rebellion was at hand, pushed his fatigued army into action on the 17th, having built a pair of pontoon bridges across the river the day before. The Mexican general reasoned that the Tejans were just as winded as his own troops, and that stopping for breakfast would cost him the initiative. This proved to be the second-greatest error Filisola made that day.

The advance began at 11:30, and made poor initial progress. The Mexican army was too exhausted from its long march, and the pontoons became deadly bottlenecks for the numerically superior attackers. Still, the Tejan army was a hodgepodge of local militias and raw recruits, so a slight slackening in their fire provided a window for the Mexicans to push forward and establish a beachhead on the opposite side of the Neches. Once this was done, the weight of numbers could make itself felt. By 1:30, the Tejan center was giving way.

At 1:34, the third difference between Tejas and other states made itself known. The Neches was disputed territory between New Spain and the United States. The American government thought it a tributary of the Sabine river, which was claimed as part of the Louisiana Purchase. Houston knew this, and had baited Filisola’s army into violating the disputed soil in his eagerness to crush the rebellion. Once his scouts had spotted the Mexicans approaching his position, Houston sent Bowie to inform General Edmund Gaines, whose army detachment was stationed nearby. [5]

Tejan forces battle the Mexican army at the Neches River.

Secretary of War Lewis Cass had instructed Gaines to respond with force should Mexican forces cross the Sabine River. That Filisola approached the Neches intending to engage Houston on the west bank was pretext enough for Gaines to act pre-emptively and assist the Tejans. His army crossed the Neches north of the ongoing engagement, and fell upon the Mexican rear. Filisola’s fixation on the immediate threat left him blindsided by the arrival of a second army, and his forces splintered on opposite sides of the river. Around 2,500 Mexicans eventually managed to escape southwards, but 2,700 men, Filisola included, were hemmed in between the Tejan and American armies and forced to surrender. Upon hearing of the battle, the Pike Administration promptly accused New Spain of violating its territory, with Bustamante levelling the same charges back at Pike. On July 31st, Bustamante declared war on the United States, while the US Congress would reciprocate two days later. The Tejanos had received their miracle, or so it seemed.

[1] Edwards led an anti-Mexican revolt in the 1820s IOTL, that Austin and others helped suppress. He didn’t do that here in part because Morelos did a better job of briefing his empresarios on the specifics of their responsibilities, but also for other reasons.

[2] Oaxaca and Zacatecas were the first states to rebel against Santa Anna IOTL.

[3] The Alamo isn’t as well-remembered ITTL, in part because it falls much quicker, but also because it’s overshadowed by the battle on the Neches and its Helm’s Deep-like conclusion.

[4] There was a (very small) expedition mounted into Mexico IOTL, but the far larger invading Mexican army ITTL just can’t be ignored.

[5] Gaines was positioned in Louisiana like this IOTL, and I read speculation that he had secret orders to engage a Mexican army if they violated what was seen as US territory. I don’t know how true that is, but the Pike Administration’s Latin American ambitions make it true ITTL. Gaines was led to understand by Cass and Pike that he should creatively interpret his official instructions if the situation demanded it.

Chapter Thirty-Five: Politics by Other Means

Excerpted from The Road to War: 1830-1852 by Alexander Peterson, 1971.

Like many revolutions, the rebellion in Tejas began militarily, leaving political actors struggling to keep pace with developments. The appointment of Lorenzo de Zavala as the next Viceroy for New Spain provided an immediate pretext for resistance against the Bustamante regime. Tejas Governor José María Viesca endorsed Zavala and called on other state governments to follow suit, but he himself had been pre-empted in his declaration by Stephen Austin, the unofficial leader of the Anglo settlers in the region. Viesca wouldn’t forget this slight, but the Governor understood that his goals still coincided with Austin’s. Both men were more interested in restoring Constitutional rule to the Kingdom than in seceding to join the United States. This differentiated the two from Haden Edwards, the hot-headed empresario in charge of the lands along the Navasota. [1]

By Summer of 1832, it had become clear that Bustamante would not step down from his position as Viceroy, regardless of Madrid’s opinion of him. Austin and other empresarios began mobilising their local militias to expel Mexican army units from the state. Viesca turned a blind eye to their activities, having reached a tacit understanding with Austin that secession was not in the offing. It is important for the present-day reader to remember that the sedition in Tejas was not unusual for Mexican provinces at this point. State Governors elsewhere were just as assertive in their denunciations of the centralists in Mexico City. El Salvador, Oaxaca, Zacatecas, and Yucatan also resisted the federal government, with varying degrees of effectiveness, stretching the Mexican army considerably. [2]

Three things set the unrest in Tejas apart from that in other states. The first was the empresario system. The empresarios were men authorised by the Mexican government to recruit settlers for the lands in Tejas. Once settlement was underway, the empresarios would also be expected to keep order in the lands under their supervision with private militias. This programme had the effect of raising military formations with no loyalty to the Mexican government, which certainly had its implications when the revolt against Bustamante began. But by allowing French and American empresarios to set up shop in Tejas, the government unwittingly diluted the cultural identity of the state. Immigrants were required to learn Spanish to gain admittance, but the establishment of tight-knit immigrant communities like Bettencour and San Felipe ensured that French and English were still used in day-to-day life, driving a wedge between the settlers and native Mexicans. The introduction of slavery presented yet another bone of contention, especially once Bustamante took power and began to undermine state autonomy.

The second difference between Tejas and other rebellious states is that the former could afford to trade space for time. The Mexican army under Filisola was too large to resist in open battle, but it was also too large to support itself in the field for long. The Tejano militias under Samuel Houston exploited this weakness by fighting delaying actions while drawing Filisola ever farther into enemy territory. The first major battle took place on the 3rd of March 1833, at the Nueces river northwest of Bettencour. The Tejans gave way quickly under the weight of numbers, but the army managed to retreat in good order. Filisola left men behind to occupy Bettencour while the bulk of his force advanced further northwest and captured the fort of Béxar. [3]

The fall of Béxar left Tejas dangerously exposed to the Mexican army.

It was at this point that political considerations began to reassert themselves. The complexion of the rebellion had changed over its first six months. A sizable influx of American volunteers bolstered the ranks of Houston’s army. This caused its own problems, however, as the army’s growing size also increased the importance of requisitioning supplies from local communities.

The political character of the rebels also changed dramatically during this time. The provisional government guiding the rebels was designed to coordinate the efforts of the empresarios with that of the original state government, but the sheer demographic weight of the English-speaking community and army resulted in the slow-motion marginalisation of Governor Viesca and other Mexican federalists. A proposal from Viesca for the Tejan army to mount a counteroffensive into New Spain in support of federalist forces was promptly voted down by the provisional government – with a large Mexican army encroaching on their territory, the idea of diverting forces elsewhere was deemed too risky. [4]

The situation for Tejas deteriorated even further over the Summer of 1833. Filisola split his army again, with separate forces laying siege to Goliad on the Gulf Coast, forcing the provisional government to abandon San Felipe, and still harrying Houston’s army as it retreated towards the Neches River. Houston readied his dispirited army for a last stand on the far bank, dispatched James Bowie to deliver a message, and waited for Filisola.

The Mexican army reached the Neches on July 16th. Filisola now commanded 5,500 men after having dispersed men to occupy Tejas, as well as sending several hundred men back into New Spain proper at Bustamante’s request to help put down Yorkino activity. Houston, for his part, commanded around 2,600 men, of which 1,500 had only come to Tejas after the start of the uprising the previous year. Filisola, sensing that the end of the rebellion was at hand, pushed his fatigued army into action on the 17th, having built a pair of pontoon bridges across the river the day before. The Mexican general reasoned that the Tejans were just as winded as his own troops, and that stopping for breakfast would cost him the initiative. This proved to be the second-greatest error Filisola made that day.

The advance began at 11:30, and made poor initial progress. The Mexican army was too exhausted from its long march, and the pontoons became deadly bottlenecks for the numerically superior attackers. Still, the Tejan army was a hodgepodge of local militias and raw recruits, so a slight slackening in their fire provided a window for the Mexicans to push forward and establish a beachhead on the opposite side of the Neches. Once this was done, the weight of numbers could make itself felt. By 1:30, the Tejan center was giving way.

At 1:34, the third difference between Tejas and other states made itself known. The Neches was disputed territory between New Spain and the United States. The American government thought it a tributary of the Sabine river, which was claimed as part of the Louisiana Purchase. Houston knew this, and had baited Filisola’s army into violating the disputed soil in his eagerness to crush the rebellion. Once his scouts had spotted the Mexicans approaching his position, Houston sent Bowie to inform General Edmund Gaines, whose army detachment was stationed nearby. [5]

Tejan forces battle the Mexican army at the Neches River.

Secretary of War Lewis Cass had instructed Gaines to respond with force should Mexican forces cross the Sabine River. That Filisola approached the Neches intending to engage Houston on the west bank was pretext enough for Gaines to act pre-emptively and assist the Tejans. His army crossed the Neches north of the ongoing engagement, and fell upon the Mexican rear. Filisola’s fixation on the immediate threat left him blindsided by the arrival of a second army, and his forces splintered on opposite sides of the river. Around 2,500 Mexicans eventually managed to escape southwards, but 2,700 men, Filisola included, were hemmed in between the Tejan and American armies and forced to surrender. Upon hearing of the battle, the Pike Administration promptly accused New Spain of violating its territory, with Bustamante levelling the same charges back at Pike. On July 31st, Bustamante declared war on the United States, while the US Congress would reciprocate two days later. The Tejanos had received their miracle, or so it seemed.

[1] Edwards led an anti-Mexican revolt in the 1820s IOTL, that Austin and others helped suppress. He didn’t do that here in part because Morelos did a better job of briefing his empresarios on the specifics of their responsibilities, but also for other reasons.

[2] Oaxaca and Zacatecas were the first states to rebel against Santa Anna IOTL.

[3] The Alamo isn’t as well-remembered ITTL, in part because it falls much quicker, but also because it’s overshadowed by the battle on the Neches and its Helm’s Deep-like conclusion.

[4] There was a (very small) expedition mounted into Mexico IOTL, but the far larger invading Mexican army ITTL just can’t be ignored.

[5] Gaines was positioned in Louisiana like this IOTL, and I read speculation that he had secret orders to engage a Mexican army if they violated what was seen as US territory. I don’t know how true that is, but the Pike Administration’s Latin American ambitions make it true ITTL. Gaines was led to understand by Cass and Pike that he should creatively interpret his official instructions if the situation demanded it.

Chapter Thirty-Six: All According to Plan

I think I've got a decent rhythm for these Texas Revolution chapters now. Most of this one details American moves during the Tejas crisis, and Zebulon Pike's motivations, with the main war narrative moving forward at the end. I'm trying to strike the right balance of introducing a new player into this situation while also making progress in the actual narrative. Getting this down right will be crucial once I get to the 1850's, and have to write about three big wars at once, so be sure and let me know how you feel about my handling of the pacing now. Also, enjoy!

In America, the Zebulon Pike Administration has accumulated a vast literature of hagiography, mythmaking, and several rounds of historical revisionism, especially following the publication of Pike’s memoirs after his death in 1851. Chief among the myths surrounding this most consequential of men is that Pike’s presidency was the culmination of nearly three decades of carefully calculated strategy. From the time he first set foot into New Spain in 1806 Pike, or so the story goes, was pursuing his long-term ambitions of American expansionism at Spanish expense. This is almost certainly an exaggeration; Pike’s journals from his explorer days make no mention of ambitions towards political office, and indeed it wasn’t until members of Congress began meeting with him in the years after his invasion of Florida that he became interested in national politics. [1]

That said, there is strong evidence that from the 1820’s onwards, Zebulon Pike was indeed pursuing anti-Mexican foreign policy, which naturally reached its zenith during the Tejan Revolution. Under the Ordinance of 1819, the Kingdom retained strong ties to Spain, and this gave the European power a foothold on America’s doorstep. This was a threat Pike sought to neutralize as best he could. In particular, Pike seemed interested in undermining the federalist government of Viceroy Morelos.

“There is no doubt in my mind that New Spain is on a similar path to the one our own nation took following the Revolution,” he wrote. “Like us, they will discover the limitations of federal government. The upheaval that follows could prove quite advantageous to those who make use of it.”

To this end, Pike sought to foment regional separatism in New Spain. This instability could provoke a centralist backlash, thereby increasing the likelihood of Mexican-American conflict. And if the centralists failed to take power, then regional governments would be free to go their own way, and fall under Washington’s influence regardless. One key contact was the empresario Haden Edwards, who started corresponding regularly with Pike during the 1824 campaign. Pike advised Edwards to cooperate with Viceroy Morelos for the time being, knowing that Austin and other Anglo settlers were unready for a break with Mexico City. Should the Viceroy be replaced by a centralist, then Edwards should gather allies, but only for the purpose of restoring federalist government, a platform that would attract the broadest support in Tejas. Only once rebellion was underway would it be safe to begin proposing more radical measures like secession. [2]

Another of Pike’s moves involved Émile and Isaac Pérriere. In 1824, Émile Pérriere met with John Forsyth, the US Minister to France and a staunch ally of Zebulon Pike. [3] Forsyth brought the troubles of Costa Rica to the attention of the young French investor, and suggested the potential for the state to host a lucrative coffee industry. Forsyth’s contacts in the US State Department helped arrange the subsequent meeting between the Pérriere brothers and Governor Gallegos, something that was carefully concealed from then-President Clay. For all of Bustamante’s paranoia about a vast anti-Mexican conspiracy, Pike went to great lengths to make just such an encirclement a reality.

An early convert to the Pikean cause, John Forsyth would help advance Pike's ambitions as Minister to France, and then as Secretary of State after 1832.

Of course, Pike’s machinations in 1824 all took place under the assumption that the general would win the presidency in November, so as to take immediate advantage of the instability he was cultivating. Pike’s loss to Henry Clay frustrated him, but the defeated candidate bided his time, taking solace in the realization that his efforts in New Spain would take time to bear fruit. His subsequent defeat in 1828 was even more galling, but Pike made the most of his situation by joining forces with Martin Van Buren. If he could not be President, then he could still influence the country’s foreign policy by joining the new Administration. With the Bustamante coup in 1830 and Van Buren’s assassination the following year, the pieces finally fell into place for Pike.

As Acting President, Pike made the final preparations he thought necessary for a confrontation with Mexico. He offered refuge to nominal Viceroy Lorenzo de Zavala, knowing that the Yorkino would make a strong propaganda tool to use against Bustamante, but also that the Viceroy’s practical influence would wane outside of New Spain. [4] And during his tour of Europe in 1832, Pike discussed the situation in Mexico City with Europe’s leading statesmen.

King Francisco had washed his hands of Bustamante after he refused to step down in favour of Zavala, privately revoking Spanish protection over New Spain. Napoleon II took a dim view of the Bustamante regime’s infringement on free trade, and promised to send agents into Francophone Tejas to aid the secessionist cause in exchange for a restoration of French assets in New Spain, as well as an assurance from Pike that French Catholics would be tolerated in the event of the United States annexing Tejas. To meet this promise, Pike’s 1832 campaign platform proposed a Constitutional amendment, guaranteeing equal protection under the law regardless of one’s religious denomination. This measure ran afoul of nativist sentiments in much of the country, but would eventually be ratified in 1840 as the 13th Amendment. Lastly, the British government professed disinterest in the matter so long as its interests in Belize were not infringed upon.

With an adequate casus belli in hand, and the great powers of Europe mollified, Pike finally had his opportunity to break Mexican power. What he didn’t have was the military readiness to exploit his opening. The traditional American wariness towards standing armies left Pike with little to work with; in fact, the 2,000 man force under Gaines’ command in Tejas represented over a quarter of American strength, once garrisons and deployments against the Indians out west were accounted for. Pike sent out a call for volunteers to bolster the Army, while the United States Navy set sail for Cuba.

The Marine assault on Santiago de Cuba, September 10th-12th, 1833.

On September 8th, 1833, the American fleet defeated a Mexican squadron at Santiago de Cuba, but the subsequent landing by US Marines was repulsed over three days of heavy fighting. Meanwhile, the remnants of Filisola’s army in Tejas, led by Colonel Martín Perfecto de Cos, managed a successful fighting withdrawal back from the Neches, frustrating the combined US-Tejan force under Gaines. Pike had little doubt that the United States would ultimately triumph, but early setbacks showed victory would not come quickly. A long and potentially costly struggle lay ahead.

[1] IOTL, Pike’s journals from the 1806 expedition got confiscated, and weren’t made available in the US until the 20th Century. The decades where Pike’s presidential memoirs were available but his early stuff wasn’t helped feed this in-universe misconception.

[2] As far as strategy goes, Pike is taking inspiration from the American Revolution, which also started before there was a consensus behind independence from Britain. He recognizes that for Texas to repeat that, they’ll need to start with less ambitious goals.

[3] Forsyth was the US Minister to Spain during OTL’s Monroe Administration, and an ally of Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s diminished stature ITTL results in him drifting into Pike’s orbit instead.

[4] Pike’s offer of asylum was kind of a trap. It saves Zavala from getting purged like the rest of the York Lodge, but it also makes him look like a coward, running to the Gringos for help when he’s supposed to have the backing of the King of Spain, who’s also made to look weak. Pike’s playing the propaganda game for all it’s worth.

Chapter Thirty-Six: All According to Plan

Excerpted from The Road to War: 1830-1852 by Alexander Peterson, 1971.

In America, the Zebulon Pike Administration has accumulated a vast literature of hagiography, mythmaking, and several rounds of historical revisionism, especially following the publication of Pike’s memoirs after his death in 1851. Chief among the myths surrounding this most consequential of men is that Pike’s presidency was the culmination of nearly three decades of carefully calculated strategy. From the time he first set foot into New Spain in 1806 Pike, or so the story goes, was pursuing his long-term ambitions of American expansionism at Spanish expense. This is almost certainly an exaggeration; Pike’s journals from his explorer days make no mention of ambitions towards political office, and indeed it wasn’t until members of Congress began meeting with him in the years after his invasion of Florida that he became interested in national politics. [1]

That said, there is strong evidence that from the 1820’s onwards, Zebulon Pike was indeed pursuing anti-Mexican foreign policy, which naturally reached its zenith during the Tejan Revolution. Under the Ordinance of 1819, the Kingdom retained strong ties to Spain, and this gave the European power a foothold on America’s doorstep. This was a threat Pike sought to neutralize as best he could. In particular, Pike seemed interested in undermining the federalist government of Viceroy Morelos.

“There is no doubt in my mind that New Spain is on a similar path to the one our own nation took following the Revolution,” he wrote. “Like us, they will discover the limitations of federal government. The upheaval that follows could prove quite advantageous to those who make use of it.”

To this end, Pike sought to foment regional separatism in New Spain. This instability could provoke a centralist backlash, thereby increasing the likelihood of Mexican-American conflict. And if the centralists failed to take power, then regional governments would be free to go their own way, and fall under Washington’s influence regardless. One key contact was the empresario Haden Edwards, who started corresponding regularly with Pike during the 1824 campaign. Pike advised Edwards to cooperate with Viceroy Morelos for the time being, knowing that Austin and other Anglo settlers were unready for a break with Mexico City. Should the Viceroy be replaced by a centralist, then Edwards should gather allies, but only for the purpose of restoring federalist government, a platform that would attract the broadest support in Tejas. Only once rebellion was underway would it be safe to begin proposing more radical measures like secession. [2]

Another of Pike’s moves involved Émile and Isaac Pérriere. In 1824, Émile Pérriere met with John Forsyth, the US Minister to France and a staunch ally of Zebulon Pike. [3] Forsyth brought the troubles of Costa Rica to the attention of the young French investor, and suggested the potential for the state to host a lucrative coffee industry. Forsyth’s contacts in the US State Department helped arrange the subsequent meeting between the Pérriere brothers and Governor Gallegos, something that was carefully concealed from then-President Clay. For all of Bustamante’s paranoia about a vast anti-Mexican conspiracy, Pike went to great lengths to make just such an encirclement a reality.

An early convert to the Pikean cause, John Forsyth would help advance Pike's ambitions as Minister to France, and then as Secretary of State after 1832.

Of course, Pike’s machinations in 1824 all took place under the assumption that the general would win the presidency in November, so as to take immediate advantage of the instability he was cultivating. Pike’s loss to Henry Clay frustrated him, but the defeated candidate bided his time, taking solace in the realization that his efforts in New Spain would take time to bear fruit. His subsequent defeat in 1828 was even more galling, but Pike made the most of his situation by joining forces with Martin Van Buren. If he could not be President, then he could still influence the country’s foreign policy by joining the new Administration. With the Bustamante coup in 1830 and Van Buren’s assassination the following year, the pieces finally fell into place for Pike.

As Acting President, Pike made the final preparations he thought necessary for a confrontation with Mexico. He offered refuge to nominal Viceroy Lorenzo de Zavala, knowing that the Yorkino would make a strong propaganda tool to use against Bustamante, but also that the Viceroy’s practical influence would wane outside of New Spain. [4] And during his tour of Europe in 1832, Pike discussed the situation in Mexico City with Europe’s leading statesmen.

King Francisco had washed his hands of Bustamante after he refused to step down in favour of Zavala, privately revoking Spanish protection over New Spain. Napoleon II took a dim view of the Bustamante regime’s infringement on free trade, and promised to send agents into Francophone Tejas to aid the secessionist cause in exchange for a restoration of French assets in New Spain, as well as an assurance from Pike that French Catholics would be tolerated in the event of the United States annexing Tejas. To meet this promise, Pike’s 1832 campaign platform proposed a Constitutional amendment, guaranteeing equal protection under the law regardless of one’s religious denomination. This measure ran afoul of nativist sentiments in much of the country, but would eventually be ratified in 1840 as the 13th Amendment. Lastly, the British government professed disinterest in the matter so long as its interests in Belize were not infringed upon.

With an adequate casus belli in hand, and the great powers of Europe mollified, Pike finally had his opportunity to break Mexican power. What he didn’t have was the military readiness to exploit his opening. The traditional American wariness towards standing armies left Pike with little to work with; in fact, the 2,000 man force under Gaines’ command in Tejas represented over a quarter of American strength, once garrisons and deployments against the Indians out west were accounted for. Pike sent out a call for volunteers to bolster the Army, while the United States Navy set sail for Cuba.

The Marine assault on Santiago de Cuba, September 10th-12th, 1833.

On September 8th, 1833, the American fleet defeated a Mexican squadron at Santiago de Cuba, but the subsequent landing by US Marines was repulsed over three days of heavy fighting. Meanwhile, the remnants of Filisola’s army in Tejas, led by Colonel Martín Perfecto de Cos, managed a successful fighting withdrawal back from the Neches, frustrating the combined US-Tejan force under Gaines. Pike had little doubt that the United States would ultimately triumph, but early setbacks showed victory would not come quickly. A long and potentially costly struggle lay ahead.

[1] IOTL, Pike’s journals from the 1806 expedition got confiscated, and weren’t made available in the US until the 20th Century. The decades where Pike’s presidential memoirs were available but his early stuff wasn’t helped feed this in-universe misconception.

[2] As far as strategy goes, Pike is taking inspiration from the American Revolution, which also started before there was a consensus behind independence from Britain. He recognizes that for Texas to repeat that, they’ll need to start with less ambitious goals.

[3] Forsyth was the US Minister to Spain during OTL’s Monroe Administration, and an ally of Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s diminished stature ITTL results in him drifting into Pike’s orbit instead.

[4] Pike’s offer of asylum was kind of a trap. It saves Zavala from getting purged like the rest of the York Lodge, but it also makes him look like a coward, running to the Gringos for help when he’s supposed to have the backing of the King of Spain, who’s also made to look weak. Pike’s playing the propaganda game for all it’s worth.

The next chapter is going to continue the conflict in Mexico, but after that, I don't have any immediate plans for what to do next. Pike's America will get covered, but after all the North America focus of the last five updates, I think I'll wait a bit before returning to that well. So is there anything in particular you guys want to see expanded on? Keeping in mind that the time frame will still be roughly 1830-1835 here.

I've largely kept my own counsel as to the direction of this story, but this arc is pretty open as far as possibilities, so I'm interested to know what you guys want more of at the moment.

I've largely kept my own counsel as to the direction of this story, but this arc is pretty open as far as possibilities, so I'm interested to know what you guys want more of at the moment.

Threadmarks

View all 59 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Fifty: Le Plus Ça Change... Chapter Fifty-One: The Martyr's Rule Begins Chapter Fifty-Two: Seeds of Eulogy Chapter Fifty-Three: Halfway Along Our Life’s Path Chapter Fifty-Four: Cherchez La Femme…Or May The Bridges That She Burns Light The Way Chapter Fifty-Five: Macartney's Revenge Chapter Fifty-Six: Misty Tales and Poems Lost Chapter Fifty-Seven: One Step at a Time

Share: